Abstract

Chemotaxis of tumour cells and stromal cells in the surrounding microenvironment is an essential component of tumour dissemination during progression and metastasis. This Review summarizes how chemotaxis directs the different behaviours of tumour cells and stromal cells in vivo, how molecular pathways regulate chemotaxis in tumour cells and how chemotaxis choreographs cell behaviour to shape the tumour microenvironment and to determine metastatic spread. The central importance of chemotaxis in cancer progression is highlighted by discussion of the use of chemotaxis as a prognostic marker, a treatment end point and a target of therapeutic intervention.

Chemotaxis is the phenomenon by which the movement of cells is directed in response to an extracellular chemical gradient. Over 100 years of research have illustrated the importance of chemotaxis in physiological processes, such as the recruitment of inflammatory cells to sites of infection, and in organ development during embryogenesis. In cancer, chemotaxis pathways can be reprogrammed in favour of tumour cell dissemination1. To successfully metastasize, a carcinoma cell must invade, intravasate, extravasate and grow at a distant site. Chemotaxis is thought to be involved in each of these crucial steps of tumour cell dissemination. Chemotaxis of carcinoma cells and tumour-associated inflammatory and stromal cells is mediated by chemokines, chemokine receptors, growth factors and growth factor receptors (TABLE 1 and Supplementary information S1 (table)). Mutation and/or changes in the regulation of many of these factors are frequently involved in the development and progression of various types of cancer. Although most of these factors have roles in the growth and survival of tumour and stromal cells, their downstream signalling cascades can also lead to changes in cytoskeletal dynamics that result in chemotaxis. This suggests a potentially important and sometimes overlooked role of chemotaxis in cancer cell dissemination and metastatic progression. The development of new technologies and a burst of interdisciplinary collaboration in the study of chemotaxis in cancer have recently provided valuable insights into novel and specific mechanisms of invasion and dissemination and have ignited much hope for new prognostic tools and therapeutic interventions. In this Review, we discuss the role of chemotaxis in cancer cell dissemination and discuss whether chemotaxis is a viable marker for treatment decisions and a target for cancer therapy.

Table 1.

Chemokines and growth factors involved in chemotaxis in cancer

| Chemokine or growth factor | Chemokine receptor or growth factor receptor | Experimental evidence for chemotaxis in cancer | Types of cancer affected |

|---|---|---|---|

| CXCL12 (also known as SDF1) | CXCR4 |

|

Breast, prostate, ovarian, pancreatic, colorectal, renal and gastric cancers, melanoma, NSCLC, rhabdomyosarcoma and Ewing’s sarcoma |

| CCL19 and CCL21 | CCR7 | Transwell assay (Boyden chamber) | Breast, cervical and lung cancers, leukaemia and squamous cell carcinoma |

| CCL22 | CCR4 |

|

Breast, ovarian and gastric cancers and leukaemia |

| CX3CL1 (also known as fractalkine) | CX3CR1 |

|

Pancreatic, prostate and lung cancers and neuroblastoma |

| CCL5 (also known as RANTES), CCL2 (also known as MCP1), CCL3 (also known as MIP1α) and CCL7 (also known as MCP3) | CCR1 |

|

Colorectal cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma and melanoma |

| CCL25 | CCR9 | Transwell assay (Boyden chamber) | Melanoma and leukaemia |

| CXCL1, CXCL5, CXCL6 and CXCL8 | CXCR1 and CXCR2 |

|

Colorectal, head and neck and prostate cancers, melanoma and leukaemia |

| EGF, TGFα, betacellulin, HBEGF, amphiregulin and heregulin (also known as NRG1) | EGFR (also known as ERBB1), ERBB2 (also known as HER2), ERBB3 and ERBB4 |

|

Breast, lung, colorectal and gastric cancers, glioblastoma, mesothelioma and neurofibromatosis |

| FGF | FGFR1–4 |

|

Breast, ovarian, pancreatic and renal cancers, glioblastoma and Ewing’s sarcoma |

| PDGF | PDGFR |

|

Breast cancer, glioblastoma, mesolthelioma and melanoma |

| TGFβ | TGFβR1 and TGFβR2 |

|

Breast, lung, squamous cell and oesophageal cancers |

| IGF1 | IGF1R |

|

Breast cancer, sarcoma, multiple myeloma, lymphoma, choriocarcinoma, mesothelioma and melanoma |

| CSF1 (also known as MCSF) | CSF1R |

|

Breast, ovarian, endometrial, prostate and gastric cancers and leukaemia |

| VEGFA and VEGFC | VEGFR1–3 |

|

Melanoma, prostate cancer, sarcoma, meningioma and leukaemia |

For a more comprehensive version of this table, with information on therapeutic compounds in development for the above factors, as well as references, see Supplementary information S1 (table). 3D, three-dimensional; CSF1, colony-stimulating factor 1; CSF1R, CSF1 receptor; EGF, epidermal growth factor; EGFR, EGF receptor; FGF, fibroblast growth factor; FGFR, FGF receptor; HBEGF, heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor; IGF1, insulin-like growth factor 1; IGF1R, IGF1 receptor; MCP, monocyte chemoattractant protein; MIP1, macrophage inflammatory protein 1; NK, natural killer; NSCLC, non-small-cell lung cancer; PDGF, platelet-derived growth factor; PDGFR, PDGF receptor; TGF, transforming growth factor; TGFβR, TGFβ receptor; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; VEGFR, VEGF receptor.

Chemotaxis and cell migration

Cell migration is an essential component of metastatic dissemination of tumour cells from the primary tumour to local and distant sites2–4. Although tumour cells can move both randomly and directionally, invasion, migration and dissemination are most efficient when the cell is involved in directed migration5. Different types of directed cell migration have been observed in tumour cells: chemotaxis, haptotaxis, electrotaxis and durotaxis6. The location and type of cue theoretically determines which of these types of directed cell migration is engaged. For example, directed migration towards a soluble chemotactic agent is traditionally called chemotaxis, migration towards a substrate-bound agent is called haptotaxis and migration that is influenced by an extracellular matrix (ECM) rigidity gradient is called durotaxis7.

Although the shape and amplitude of a soluble chemotactic gradient delivered experimentally in vitro can be defined with precision8–11, current technology does not allow the distinction of chemotaxis in vivo towards soluble factors from chemotaxis towards factors partially or fully bound to the ECM and/or cell surfaces. For example, in vitro binding studies indicate that cytokines can become immobilized to form solid state gradients, which suggests that both soluble and solid state gradients might contribute to chemotaxis in vivo12. However, because it is not possible to know whether a gradient is soluble or solid state when observing cell behaviour in vivo, for the purposes of this Review, we define chemotaxis in vivo as directional migration to either soluble or solid state gradients.

Chemotaxis is the result of three separate steps: chemosensing, polarization and locomotion13. Depending on the cell type and the microenvironment, migration can involve single unattached cells or multicellular groups (TABLE 2). Directed migration of single tumour cells can be subdivided into either amoeboid migration or mesenchymal migration. Directed multicellular migration can be subdivided into either collective migration, in which the cells are in tight contact with each other (also known as cohort migration) or cell streaming, in which the coordinated cell migration involves cells that are not always in direct physical contact. The occurrence and frequency of these different modes of migration in cancer is dependent on the tumour type and the types of cells and surrounding factors in the tumour microenvironment14,15 (TABLE 2). Various methods have been used to study in detail the different modes of migration in cancer, including cultured cells in vitro16, three-dimensional cultures with cells embedded in reconstituted ECM gels17–19 and intravital multiphoton microscopy of live animals4,20–22 (TABLE 3).

Table 2.

Types of directed cell migration

| Single cell migration | Multicellular migration | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amoeboid | Mesenchymal | Collective or chain migration | Streaming | |

| Movement type |

|

|

|

|

| Cell types |

|

|

|

|

| Microenvironmental factors influencing migration | Chemokine and growth factor gradients | Chemokine and growth factor gradients, proteolysis | Chemokine and growth factor gradients, reorganization of extracellular matrix | Chemokine and growth factor gradients, reorganization of extracellular matrix, paracrine signalling |

| Extracellular matrix degradation required? | Sometimes | Yes | Yes | Probably |

| Can cells switch between types of migration? | Amoeboid to mesenchymal | Mesenchymal to amoeboid, mesenchymal to collective | Collective to single cell migration (amoeboid or mesenchymal) | Not determined |

| Cell shape during migration | Pseudopodia dominate the shape | Elongated or spindle-shaped | The leader cell is elongated, the cells in the attached sheet are cuboidal | Mixed: cells transition between pseudopod and elongated |

| Cell–cell junctions maintained? | No | No | Yes | No |

| Processes where type of migration is observed |

|

|

|

|

| Types of cancer | Breast and prostate cancers and melanoma | Breast and prostate cancers, melanoma, lung and squamous cell carcinomas | Breast, prostate, lung and colorectal cancers, melanoma and squamous cell carcinoma | Breast cancer |

| Refs | 14,23,24,46–48,127,174 | 14,27,28 | 14,17,22,29,35,36,39,40 | 5,42–44,123 |

Table 3.

Methodologies for studying cell migration in cancer

| Advantages | Disadvantages | |

|---|---|---|

| In vitro methods | Users can add desired growth factors and evaluate chemotaxis through a chemoattractant gradient | No tumour microenvironment: these systems lack a vasculature, the normal transport of small molecules, host immune responses and other cell–cell interactions |

| 2D chemotaxis assays* |

|

Requires a high skill level and can be tedious |

| Transwell assay (Boyden chamber) |

|

|

| 3D invasion19 |

|

No control of growth factor gradients |

| Wound healing |

|

|

| 3D culture16 |

|

|

| In vivo methods | An accurate representation of the tumour microenvironment |

|

| In vivo invasion assay | Migration in response to chemoattractants in vivo can be determined | |

| Intravital imaging |

|

Expensive |

2D, two-dimensional; 3D, three-dimensional.

2D chemotaxis assays include the pipette-following assay, the Dunn chamber, the Zigmond chamber and the Soon chamber.

Amoeboid migration of single tumour cells has been observed in tumours in vivo by intravital multiphoton imaging. Such studies have shown that some carcinoma cells with an amoeboid morphology can move at high speeds inside the tumours (~4 μm min−1)4. Amoeboid cell motility does not always require the activity of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) because cells can squeeze through gaps in the ECM by generating large amounts of contractile force23,24. At the other end of the range of modes of motility, mesenchymal migration of single cells, which sometimes involves collective migration, is characterized by an elongated cell morphology with established cell polarity and relatively low speeds of cell migration (0.1–1 μm min−1)15. Tumour cells undergoing epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), which is apparent in 10–40% of carcinomas25, can use mesenchymal migration25. Mesenchymal cell migration relies on proteolysis of ECM proteins to enable cells to move through the matrix-filled space of the tumour26. However, even though amoeboid and mesenchymal modes of migration can be readily separated when studied in vitro, evidence suggests that they are not mutually exclusive in vivo and can interconvert. In tumour cells, responses to changes in the microenvironment can induce rapid transitions between these modes of migration27,28. For example, inhibition of proteolysis can promote the transition from mesenchymal to amoeboid migration in tumour cells23, whereas enhanced paracrine chemotaxis between tumour cells and stromal cells can cause amoeboid movement in cell streams5, suggesting that a combination of treatments that target both proteases and chemotaxis may be needed in the future in order to inhibit tumour cell migration and invasion27.

Collective migration has been defined as the movement of whole clusters or sheets of tumour cells that occurs when two or more cells retain cell–cell junctions as they move together through the ECM22. In this mode of migration, leader cells positioned at the front of the migrating group actively participate in chemotaxis and matrix degradation to create tracks29–35. Cells positioned further away from the leader cells follow and this may be facilitated by physical coupling to the leader cells by drag forces and by movement along remodelled matrix tracks29–34. The leader cell in the case of collective migration can be either a tumour cell with proteolytic activity or a stromal cell from the tumour microenvironment17,36– 40. For example, in in vitro organotypic models of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), activated fibroblasts can create tracks in the ECM that enable carcinoma cells to move collectively behind them17. Additionally, it has been shown using Madin–Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells that multiple rows of cells behind an epithelial wound edge extend lamellipodia to collectively drive cell sheet movement41. In this type of collective migration the cells positioned away from the edge seem to be participating in active migration and chemokine sensing. However, this type of migration has not been documented in tumours. In this regard, it should be noted that multicellular collective migration is a separate phenomenon from multicellular streaming. During streaming, individual cells move and follow each other in the same tracks without the requirement for cell–cell contact or intact junctions5,42–44. In a similar way to collective migration, however, cell streaming often involves stromal cells that comigrate with the tumour cells, which may pathfind and/or create tracks by matrix degradation5.

Even though tumour cells can display various and sometimes interchangeable patterns of directed migration during tumour cell dissemination, the intracellular processes that direct the cell motility cycle towards a chemoattractant are probably similar. The motility cycle begins with polarized intracellular signals that lead to asymmetric actin polymerization. This results in extension of the cell membrane in the direction of movement, thus creating the leading-edge protrusion. This is followed by integrin-mediated adhesion to the substrate on which the cell is moving, and it ends with detachment from the substrate and contraction of the trailing edge of the cell45,46. The following section discusses the mechanisms and the signalling pathways that govern these processes and that regulate chemotaxis in tumour cells in particular.

Mechanisms of chemotaxis in tumour cells

The regulation of chemotaxis has been studied extensively in Dictyostelium discoideum13,46–52, mammalian leukocytes53–55 and tumour cells8,13,56–66. Chemotactic amoeboid migration involves a signal transduction system whereby a dynamic but unpolarized distribution of receptors enables cells to detect chemical gradients48,49,67. On receptor activation a series of signalling events leads to an asymmetric cytoskeletal response followed by directed cell migration towards chemotactic cues48,49,58. Owing to its genetic tractability, D. discoideum has been used to identify about 18 chemokine receptors (members of the G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) family) for about 50 different chemokines that control chemotaxis48. These prototypical studies in D. discoideum have influenced the investigation of GPCR signalling pathways controlling chemotaxis in other cell types, such as leukocytes53 and tumour cells47,51,68. In addition, studies using D. discoideum as a model system led to the development of the local excitation–global inhibition (LEGI) model to describe chemotactic amoeboid migration: receptor occupancy by the chemoattractant triggers a fast, local excitatory signal and a slower, global inhibitory signal46. The LEGI model, sometimes called the compass model55, has made an important contribution to the study of chemotaxis in tumour cells as it can be applied to various signalling pathways in tumour cells. In addition to the characterization of the LEGI model, there are other advantages of studying chemotaxis in D. discoideum (BOX 1). However, careful comparison of D. discoideum to vertebrate cells reveals important differences in chemotactic signalling pathways. For example, unlike D. discoideum, amoeboid migration of breast tumour cells relies on phosphorylated cofilin signalling pathways, which are not present in D. discoideum58,59. Thus, signalling regulation that may be important for chemotaxis of tumour cells or other cell types involved in tumour progression and metastasis cannot be fully studied using D. discoideum alone48,69,70. It is therefore important to study chemotaxis of tumour cells in physiologically relevant cell types and within the tumour microenvironment.

Box 1. Dictyostelium discoideum: a model organism for the study of chemotaxis.

Dictyostelium discoideum depends on efficient motility during its developmental cycle and its vegetative amoeboid stage52 and provides a model for the study of chemotaxis in the absence of the complexity imposed by the in vivo microenvironment of animals152–154. One of its main benefits is that when grown in culture these cells exist as homogenous chemotactic phagocytes48,49, which can be grown in high-density suspension cultures to generate kilogram quantities of proteins for biochemical analysis155. In a population, physiological responses to chemotactic stimulation are synchronous and can be correlated with biochemical measurements156,157. Also, D. discoideum is induced by physiological stimuli to undergo normal morphogenesis in vitro, which enables the role of chemotaxis in morphogenesis to be studied directly158. Recent studies have identified target of rapamycin complex 2 (TORC2) as a common regulator of cell motility in D. discoideum and neutrophils159–161. Whereas the function of TORC2 differs in D. discoideum versus neutrophils in the regulation of actin polymerization, TORC2 has key regulatory functions for controlling cell motility in both cell types160,161.

However, differences between D. discoideum and mammalian tumour cells have complicated the correlation of findings concerning chemotactic signalling and the understanding of chemotactic behaviour48,53,162. For example, there are several redundant signalling pathways controlling chemotaxis in D. discoideum47: one is dependent on PI3K and the other is dependent on phospholipase A2 (PLA2)69,163,164. Therefore, knockdown of the PI3K pathway in D. discoideum results in the incomplete inhibition of chemotaxis93,165–169, whereas knockdown of the PI3K pathway in mammalian tumour cells substantially impairs locomotion, an essential step in chemotaxis170. Additionally, in tumour cells, the early signal that determines the direction of the leading edge is not PI3K, but involves the epidermal growth factor (EGF)–phospholipase Cγ1–cofilin signalling axis59,171. D. discoideum also does not express LIM domain kinase 1 (LIMK1), a protein that is required as part of the local excitation–global inhibition (LEGI) system that controls this early signalling cascade to initiate directional sensing during the chemotaxis of tumour cells56. In addition, D. discoideum exhibits single cell amoeboid chemotaxis and multicellular coordinated cell streaming43,44, as well as multicellular collective migration at the slug stage48,172, but has not yet been shown to exhibit single cell mesenchymal migration. Finally, D. discoideum exhibits a default constitutive oscillatory movement pattern in the absence of external signalling molecules172,173, whereas tumour cells require repeated stimuli by specific signalling molecules in order to undergo directed cell migration56.

A complex network of chemokines has been described as one of the main classes of cues that initiate chemotaxis in tumour cells71. In addition to chemotaxis, the chemokine network can regulate processes such as tumour cell growth, angiogenesis, immune evasion, senescence, survival, invasion and metastatic progression72– 74. Over 50 different chemokines and chemokine receptors are now known to be involved in cancer and approximately 30% of these are also important for chemotaxis (TABLE 1). One of the most widely studied examples is the chemokine receptor CXCR4 and its ligand CXCL12 (also known as SDF1), which have been found to initiate both single cell and multicellular directed migration during metastatic progression in 11 different types of cancer75–77. Another major category of cues that has been shown to have an important role in chemotaxis is growth factors. One of the most studied growth factors involved in tumour cell chemotaxis, particularly in breast cancer, is epidermal growth factor (EGF). Signalling through either a chemokine receptor (a GPCR) or a growth factor receptor (a receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK)) will result in the initial protrusion required to set the directional compass and to define the direction of cell migration during chemotaxis56,78 and invasion57.

Two types of protrusions have been implicated in chemotaxis of tumour cells: leading-edge protrusion37,56 and invasive protrusions such as invadopodia and podosomes54,57. Invadopodia and podosomes form in response to chemotactic cytokines such as EGF and colony-stimulating factor 1 (CSF1; also known as MCSF)54,79. In two-dimensional cell culture, invadopodia and podosomes are found on the ventral surface of migrating tumour cells and macrophages, respectively, and are required for chemotaxis54,57. However, when these cells migrate in three-dimensional cultures, invadopodia and podosomes are found at the front of the cell, where they are associated with matrix degradation during locomotion37,80. Therefore, the dissection of mechanisms controlling cell protrusion, both at the leading edge and within invadopodia, is essential to understand chemotaxis and the subsequent invasion of tumour cells. The integration of the motility machinery in both of these protrusions with environmental cues that result in chemotaxis is currently under intense investigation.

Molecular pathways of chemotaxis

It is well established that the regulation of actin polymerization during tumour cell migration and invasion is controlled by RHO GTPases81. Initiation of chemotaxis occurs on binding of growth factors to GPCRs or RTKs, or adhesion of integrins to the ECM, which leads to changes in the localization or activation of guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) that in turn activate RHO GTPases81. During cell protrusion, actin polymerization within the leading-edge protrusion is under the control of the specific RHO GTPases RAC1, RAC2 and RHOA (and possibly RHOC), whereas actin polymerization within the invadopodium is under the control of RHOC82. Various steering mechanisms have been proposed and studies in tumour cells suggest that cofilin severs filamentous actin (F-actin) to initiate the molecular compass for directing actin polymerization within leading-edge protrusions and invadopodia. Directing actin polymerization to these specific locations promotes tumour cell motility and invasion during single cell migration56,78,79,83, and aids pathfinding cells during collective migration84.

During tumour cell chemotaxis, all pathways that control actin polymerization are spatially and temporally coordinated85. These include activation of cofilin and activation of the neural Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome protein (NWASP)–WASP family verprolin homologous protein (WAVE)–actin-related protein 2 (ARP2)–ARP3 pathway. In tumour cells, the cofilin-dependent actin polymerization that is required for leading-edge protrusion and invadopodium assembly is regulated by phospholipase Cγ1 (PLCγ1)86 and RHOC82 (FIG. 1a). Following initial cofilin-dependent protrusion, RAC1 leads to the formation of a WAVE2–insulin receptor substrate p53 (IRSP53; also known as BAIAP2)–ABL-interactor 1 (ABI1) complex, which activates the ARP2–ARP3 complex87. As a result, the ARP2–ARP3 complex nucleates actin filaments from the sides of cofilin-generated filaments in both lamellipodia and invadopodia83,88,89 (FIG. 1a). In addition, coordinated regulation between the WASP family and the formin mammalian diaphanous homologue 1 (MDIA1; also known as DIAPH1) shifts the balance of actin polymerization from the body to the tip of the leading-edge protrusion in tumour cells83. In the absence of RAC1- and RAC2-mediated lamellipodial protrusion, MDIA1 is activated by RHOA and promotes lamellar protrusions83. Cortactin (CTTN) regulation of cofilin and NWASP is important in the control of the stages of invadopodium assembly and maturation79,90,91. The intricate regulation of these mechanisms is essential for the proper control of the direction of protrusion and thus chemotaxis in tumour cells.

Figure 1. Regulation of chemotaxis in tumour cells.

a | The common cofilin activity cycle in lamellipodia and invadopodia. Different pathways regulating cofilin activity in the leading-edge protrusion (left side of the figure) and invadopodium (right side of the figure) are shown. The plasma membrane at the leading-edge protrusion is enriched with phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PI(4,5)P2), and the loss of binding of cofilin to PI(4,5)P2 is the primary mechanism that is used to initiate cofilin activity at the leading edge. In invadopodia, the loss of binding of cofilin to cortactin (CTTN) is the primary mechanism used to initiate cofilin activity. New actin filaments resulting from cofilin activity support dendritic nucleation (the formation of actin branches) from the actin-related protein 2 (ARP2)–ARP3 complex, which is a common feature of both lamellipodia and invadopodia. b | The local excitation–global inhibition (LEGI) model of chemotaxis as applied to the cofilin activity cycle. Asymmetric actin polymerization (green shading) results when the asymmetric activation of cofilin (green line, which follows the concentration gradient of epidermal growth factor (EGF)) is further focused by global activation of LIM domain kinase 1 (LIMK1) (red line). LIMK1 inhibits cofilin activity globally but not fully on the side of the cell facing the chemotactic signal. The cell shown above the graph represents an example of the LEGI model, whereby a tumour cell protrudes towards a gradient of EGF that is secreted by a macrophage. As a result of this stimulation there is local asymmetric excitation of cofilin, which leads to asymmetric actin polymerization in the leading-edge protrusion (green shading), and global activation of LIMK1 within the whole cell, which results in locomotion in the direction of the arrow. ABI1, ABL-interactor 1; ARG, Abelson-related gene; DAG, diacylglycerol; GEF, guanine nucleotide exchange factor; IRSP53, insulin receptor substrate p53; MDIA1, mammalian diaphanous homologue 1; MENA, mammalian enabled homologue (also known as ENAH); NCK1, NCK adaptor protein 1; NWASP, neural Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome protein; PLCγ1, phospholipase Cγ1; ROCK, RHO-associated coiled-coil-containing protein kinase; RTK, receptor tyrosine kinase; SSH, slingshot homologue; TKS5, tyrosine kinase substrate with five SH3 domains; WAVE2, WASP family verprolin homologous protein 2.

The LEGI model46 has been used successfully to describe the spatial regulation of cofilin as part of the cofilin activity cycle in different subcellular compartments within tumour cells79. This localized activity is responsible for the asymmetric actin polymerization observed within leading-edge protrusions and invadopodia. In the tumour cell LEGI model, local activation of cofilin and global inhibition of cofilin activity by LIM domain kinase 1 (LIMK1) focuses the cofilin-dependent actin polymerization activity in leading-edge protrusions and in invadopodia58,79,82 (FIG. 1b). Different starting points in a single common activity cycle control the mechanisms required for initiation of local excitation and global inhibition59. For example, in an unstimulated tumour cell, cofilin is bound to either phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PI(4,5)P2) at the plasma membrane, or CTTN at the future site of the invadopodium. The cofilin activity cycle in tumour cells begins in lamellipodia with the local activation of cofilin by PLCγ1-dependent hydrolysis of PI(4,5)P2 and in invadopodia with the SRC-initiated Abelson-related gene (ARG; also known as ABL2) kinase-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation of CTTN79,86,89 (FIG. 1a). In an EGF-stimulated tumour cell, dephosphorylation of cofilin by RAC2 is necessary to sustain but not to initiate the cofilin activity cycle79,86. However, the initiation of neutrophil motility by N-formylmethionyl-leucylphenylalanine (fMLP) involves the dephosphorylation of cofilin, thereby initiating the cofilin activity cycle at a different starting point from that seen in tumour cells (reviewed in REF. 59) (FIG. 1a).

Steps of chemotaxis

The LEGI model, in which a cell can reorient itself accurately in a chemotactic gradient, is one version of a ‘chemotactic compass model’. In addition to tumour cells, compass models have been described for other cell types such as neutrophils55 and D. discoideum49. A compass model for chemotactic sensing is consistent with photo-activation experiments, in which activation of either cofilin78 or RAC92 at the cell edge is sufficient to induce local actin polymerization and new pseudopod extension, which defines a new cell front. Because both the cofilin and RAC pathways converge on ARP2–ARP3 complex-dependent actin polymerization (FIG. 1a), their activation seems to be sufficient to generate the local break in symmetry of actin polymerization that is required for a change in cell direction as defined by the protrusion.

Another model of chemosensing is the random protrusion model93, which proposes that pseudopods arise only from pre-existing pseudopods, thus defining a narrow range of physical locations where pseudopods can form. This model states that cells do not reorient themselves by generating protrusions up the gradient, and that actin polymerization in pseudopods is regulated intrinsically, independent from external chemotactic gradients. The applicability of this model to tumour cells is unclear for several reasons. First, if the position of the source of a gradient is moved from the cell front to the cell rear, tumour cells can convert the rear (with no pre-existing pseudopods) into a cell front with pseudopods94. According to the random protrusion model, the cell would have to make a U-turn while maintaining the same cell front, which is not observed. Second, migratory tumour cells from mammary tumours have elevated sensitivity to EGF such that pseudopods are directed precisely up an EGF gradient5,8. Finally, the location of actin polymerization in mammalian cells is defined by external signals that, by breaking symmetry in the actin cytoskeleton, can cause pseudopod extension up a gradient56 or towards photo-activated cofilin or RAC78,92. Further work will be required to investigate the relevance of the random protrusion model to the chemotaxis of tumour cells in particular.

The second step of chemotaxis, cell polarization, involves the development of stable cell polarity, with a front and back, where the cell front is positioned towards the source of chemoattractant. Myosin I has been implicated in the suppression of lateral pseudopod extension in D. discoideum to maintain cell polarity during locomotion in a chemotactic gradient95. In addition, in neutrophils and D. discoideum, evidence indicates that PI3K regulates the acquisition of stable cell polarity by defining actin filament stability and myosin II contractility49,55,92.

The third step in chemotaxis involves retraction of the rear of the cell (the ‘tail’) leading to cell locomotion. This step involves myosin II-mediated contraction at the tail50 and the polarized release of cell adhesions at the tail96. The synchronization of these three steps, chemosensing, polarization and tail retraction/locomotion, results in chemotaxis. Further work is required to determine how these steps are choreographed in tumour cells.

Many studies in tumour cells have identified specific adaptor proteins that associate with chemokine and growth factor receptors in order to tune the scale of the biological response to environmental cues. For example, the enabled (ENA)–vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein (VASP) family of proteins has been implicated in the control of cell motility during cancer progression97,98. In particular, an alternatively spliced isoform of mammalian ENA homologue (MENA; also known as ENAH), termed MENAINV, was found to antagonize capping proteins (FIG. 1a) and to potentiate EGF-induced carcinoma cell invasion, chemotaxis and metastasis. This was shown to occur through sensitization of the EGF receptor (EGFR), allowing the tumour cell to respond to very low concentrations of EGF5,97 and to detect very shallow gradients8. Moreover, MENAINV was overexpressed specifically in the invasive tumour cells of rat, mouse and human primary breast tumours that were isolated in vivo by chemotaxis from tumours99. It is important to continue to identify modulators of regulatory processes involved in the chemotaxis of cancer cells to determine whether there are additional molecules that, like MENAINV, serve as master regulators of this process, and thus can influence chemotaxis by sensitizing cells to detecting shallow gradients.

Chemotaxis and the tumour microenvironment

Chemotaxis not only affects tumour cells but also helps to shape the tumour microenvironment. Directional migration to a chemokine source is evident both in vitro and in vivo for most of the cells of the tumour microenvironment. Epithelial cells produce multiple factors that recruit various tumour-infiltrating cells, including tumour-associated macrophages (TAMs), tumour-associated neutrophils (TANs), lymphocytes, cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and endothelial cells (FIG. 2). These tumour-infiltrating cells also produce a series of chemokines and growth factors that lead to a complex network of communication within the tumour microenvironment (FIG. 2; TABLE 1). Several major events are affected by chemotaxis in the context of the tumour microenvironment: immune evasion, angiogenesis, invasion and dissemination.

Figure 2. Chemotaxis shapes the tumour microenvironment.

A simplified schematic of the tumour microenvironment and the roles of chemotaxis in the processes of: immune evasion (a), angiogenesis (b) and invasion and intravasation (c) in cancer. Grey arrows indicate the gradient direction of chemotactic factors: from the cell that secretes to the cell that responds to the factor. Black arrows indicate the direction of cell migration. The dashed grey line indicates matrix fibres along which cells migrate. CSF1, colony-stimulating factor 1; CSF1R, CSF1 receptor; EGF, epidermal growth factor; EGFR, EGF receptor; PDGF, platelet-derived growth factor; TGFβ, transforming growth factor-β; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; VEGFR, VEGF receptor.

Immune evasion

Immune evasion is one of the major effects of chemotaxis in the tumour microenvironment. A complex network of chemokines and other factors that are secreted by tumour cells, but also by other stromal cells, can lead to tolerogenic responses. Regulatory T (TReg) cells mediate immune tolerance by suppressing autoreactive T cells. TReg cells express the chemokine receptor CCR4 and can be attracted to ovarian cancer cells by the tumour cell- and macrophage-derived chemokine ligand CCL22 (REF. 100) (FIG. 2a). Additionally, CCL2 and CCL5 are major attractants of monocyte precursor cells in tumours and, when accumulated, these cells play an important part in tumour non-responsiveness by suppressing antigen-specific T cell responses101. Inside the tumour and under the influence of tumour-derived chemokines, both macrophages and neutrophils can polarize away from a tumour-suppressing phenotype (M1 and N1, respectively) towards a more tumour-promoting phenotype (M2 or N2, respectively)102,103. Tumour-promoting macrophages and neutrophils then release immunosuppressive cytokines, such as interleukin-10 (IL-10), transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ) and various other chemokines such as CCL2, CCL4, CCL17, CCL22 and CXCL12. These chemokines, as well as producing large amounts of arginase, serve to inactivate T cell effector functions and contribute further towards a T helper 2 (TH2)-polarized immunity71,102,104. In patients, the presence of both TAMs and TANs has been correlated with poor prognosis in many cancer types102,105,106. In addition, myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), a heterogeneous collection of immature myeloid cells that may share common progenitors with macrophages, also migrate into tumours in response to the pro-inflammatory S100 calcium binding proteins and prostaglandin E2 (REFS 107–109). MDSCs suppress the adaptive immune response by further blocking the functions of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Finally, dendritic cells are recruited by CCL5, CXCL12 and CCL19 to the tumour, where they suppress tumour-specific immune responses110. In conclusion, a complex network of deregulated chemokines and other factors that are produced by tumour cells drive chemotaxis of immune cells into the tumour and subsequently manipulate the immune microenvironment from its normal tumour-suppressing functions to an abnormal dissemination-promoting function.

Angiogenesis

Angiogenesis not only facilitates tumour growth by supplying nutrients and oxygen to the tumour but is also a prerequisite for tumour cell dissemination and metastasis. Blood vessel density is correlated with a higher incidence of metastasis and a more rapid recurrence of disease111. Angiogenesis is the process whereby microvascular endothelial cells proliferate and sprout from pre-existing microvasculature towards the tumour. Directional migration of endothelial cells is a key process for their mobilization towards tumour cells, for which many chemoattractants have been characterized.

First, tumour cells produce chemokines that act directly on endothelial cells. Endothelial cells express the chemokine receptors CXCR2, CXCR3, CXCR4 and CXCR7 and multiple ligands to these receptors are produced by tumour cells and can induce endothelial cell chemotaxis74 (FIG. 2b). For example, the angiogenic potential of CCL11, a ligand for CXCR3, has been shown by various assays, including by standard chemotaxis assays in which migration of human microvascular endothelial cells was induced in vitro and in which vascularization was induced in vivo112. Additionally, CXCL1, CXCL2 and CXCL8 (also known as IL-8) have also been shown to have important roles in angiogenesis113, acting mainly by promoting chemotaxis of the CXCR2-expressing endothelial cells. In addition, CXCL12 is important in triggering endothelial cell migration and proliferation by binding to CXCR4 on the endothelial cell surface and can act synergistically with vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) to enhance the number of newly formed vessels114. CXCL12 can further act as a pro-angiogenic factor by recruiting CXCR4-expressing bone marrow-derived endothelial precursor cells (EPCs) to the tumour site, where they can differentiate into tumour-associated vascular endothelial cells and can actively incorporate into the newly formed vessels115. In addition, bone marrow-derived EPCs express CCR2 and CCR5 and therefore can also be attracted to the tumour site by the CCL2-, CCL3- and CCL5-producing tumour-associated endothelial cells74.

Furthermore, tumour cells can secrete chemoattractants that can indirectly affect tumour angiogenesis by regulating the immune infiltrate of the tumour (FIG. 2b). Myeloid monocytic cells such as TAMs, MDSCs and dendritic cells are recruited to the tumour site mainly by CCL2, and can produce many angiogenic factors such as VEGF, platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), TGFβ and CXCL8 (REFS 108,110). MDSCs and monocytes might also directly promote angiogenesis by acquiring characteristics of endothelial cells and participating in the formation of new vessel architecture116. Finally, CXCL8 plays a part in angiogenesis through the recruitment of neutrophils105, which drive VEGF activation through MMP9 secretion117. Overall, chemotaxis is a crucial process for angiogenesis in tumours, either directly by attracting endothelial cells to sprout and form new vessels towards tumour cells or indirectly by manipulating the immune infiltrate to assume this angiogenesis-promoting role.

Invasion and dissemination

Both invasion within the primary tumour and dissemination to distant sites require chemotaxis. The most common chemokine receptor detected on cancer cells is CXCR4, with 23 different types of cancers showing expression of this receptor on the tumour cells74. CCR7 is another chemokine receptor frequently expressed in tumour cells. In standard chemotaxis assays in vitro, CXCR4-positive cancer cells can migrate in a directional manner towards CXCL12, whereas CCR7-expressing cancer cells can migrate towards CCL21 (FIG. 2c). Activating these receptors in breast cancer cells mediates actin polymerization and leading-edge protrusion, which contributes to a chemotactic and invasive response73. In the tumour microenvironment, CAFs that have either a fibroblastic or MSC origin118 can be a source of CXCL12 and can thus promote the directional migration of tumour cells towards blood vessels or the invasive edge of the tumour115. CAFs can also produce substantial levels of CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCL3 and CXCL8, which can act as chemoattractants for various tumour cells74.

Early work suggested that chemokine gradients could explain the tissue tropism observed in the metastasis of certain types of cancer. This model suggests that organs with high expression levels of specific chemokines can guide tumour cells expressing the corresponding receptor to that site as a result of locally induced chemotaxis and invasion73,74. This has been shown for the binding pairs CXCR4–CXCL12 in bone metastasis of breast and prostate tumours, CCL21–CCR7 and CCL19–CCR7 in lymph node metastasis of various solid and haematopoietic tumours and CCL27–CCR10 in skin metastasis of melanoma74,119,120. Another potential explanation could be that the arrival of tumour cells in a specific organ is passive, at least for haematogenous metastases, and that the site of dissemination simply reflects the first pass of the cells in the circulation and their entrapment in local capillaries121. In this model, chemokine receptor expression can give tissue specificity not in terms of active recruitment to a specific metastatic site but in terms of the receptor-expressing cells having an advantage to survive and grow in the new ligand-rich metastatic microenvironment, because many of these chemotactic factors serve dual roles as cell growth and survival signals (discussed further in REF. 108).

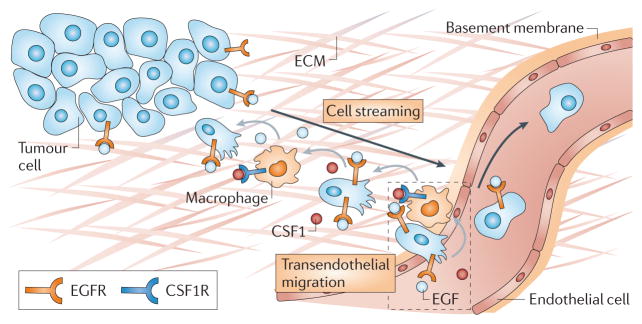

In addition to CAFs, interactions with other cells within the tumour stroma can have a major influence on the migration behaviour of tumour cells in vivo. TAMs have been implicated in tumour cell invasion and metastasis in experimental models of breast cancer122. In polyoma middle T antigen (PyMT) transgenic mouse mammary tumours, TAMs comigrate with tumour cells in a paracrine loop-dependent manner in which EGF that is produced by TAMs increases the migration of EGFR-expressing breast cancer cells. In response, cancer cells secrete CSF1, which attracts CSF1 receptor (CSF1R)-expressing TAMs123 (FIG. 2c). In patients with breast cancer, >50% of breast tumours have concomitant expression of CSF1 and CSF1R by tumour cells124, raising the potential for autocrine signalling. Indeed, in mammary tumours derived from MDA-MB-231 cells, TGFβ-dependent expression of CSF1R in the tumour cells in vivo supports both paracrine interactions with TAMs and autocrine CSF1–CSF1R signalling. Both pathways are essential for in vivo relay chemotaxis, migration and invasion of these tumour cells125. In addition to EGF and CSF1, other chemoattractants in the tumour microenvironment, such as CXCL12 and heregulin (also known as NRG1), trigger chemotaxis of tumour cells in transgenic and xenograft models of breast cancer126. Interestingly, migration to both CXCL12 and heregulin requires macrophages and the EGF–CSF1 paracrine interaction with tumour cells, suggesting that this tumour cell–macrophage interaction is a ‘central engine’ that drives the invasion and migration of breast cancer cells126. CXCL12 can also be produced by pericytes and tumour cells, suggesting that a very complex network of chemotactic gradients from multiple cell types governs directional migration and invasion of tumour cells (FIG. 2c).

Intravasation is a major route of tumour cell dissemination from solid tumours. Intravasation has been directly observed using multiphoton imaging and fate mapping of breast tumours5,20,127,128 (FIG. 3). In breast tumours, high-resolution multiphoton imaging in vivo has shown that migration and intravasation are both dependent on the EGF–CSF1 macrophage–tumour cell paracrine loop123,127, which leads to relay chemotaxis and in turn leads to multicellular streaming migration towards blood vessels and subsequent intravasation5,19,20,123,127 (FIG. 3). Another model has been proposed for the CCR7-dependent chemotaxis of tumour cells towards lymphatics60. The autologous model for chemotaxis assumes a continuous fluid flow from blood vessels to lymphatics to establish a gradient of chemoattractant towards lymphatics. This would cause tumour cell chemotaxis towards lymphatics and away from blood vessels. The extent to which this phenomenon occurs in different tumour types in live tissues has not been studied. Although this model could help to explain lymphatic dissemination, it cannot explain the commonly observed active migration of breast tumour cells towards blood vessels.

Figure 3. Observations of streaming, intravasation and dissemination of tumour cells in mammary tumours.

a | In vivo multiphoton microscopy of mammary primary tumours in mice (from REF. 5). MTLn3 rat breast adenocarcinoma cells, engineered to express a fusion protein comprised of enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP)–mammalian enabled homologue invasive splice variant (MENAINV; green), move in a multicellular stream towards a blood vessel (red) over 30 minutes. Scale bar = 25 μm. The white arrow indicates the direction of cell movement. The asterisk indicates the location of the blood vessel. See also Supplementary information S2 (movie). b | Immunohistochemistry of a fixed and paraffin-embedded MTLn3 primary tumour with tumour cells overexpressing MENAINV (T; pink) and F4/80-expressing macrophages (M; grey), imaged at x63 magnification (from REF. 5). Nuclear counterstain is shown in green. Scale bar = 20 μm. c | A tumour cell expressing EGFP (green) crossing the endothelium (red) of a blood vessel in a mammary tumour. Scale bar = 5 μm. Image courtesy of J. van Rheenen, J. Wyckoff and J.S.C., Albert Einstein College of Medicine. d | Photoconversion of dendra-expressing tumour cells from green to red allows the red tumour cells to be followed as they actively exit the primary tumour via blood vessels, with knowledge of their origin. e | Red photoconverted tumour cells arrive at the lung and remain there as either a disseminated non-dividing population (red) or as a dividing population (yellow). Scale bar = 25 μm. Parts d and e are reproduced, with permission, from REF. 128 © (2011) Macmillan Publishers Ltd. All rights reserved.

In vivo studies of chemotaxis have shown that tumour cells can respond to shallow gradients generated from various devices designed to deliver known amounts of EGF and other chemoattractants5,8,123,125,126. In these experiments, tumour cells respond to a <2% EGF gradient across the cell diameter, demonstrating their ability to chemotax in extremely shallow concentration gradients. This is particularly interesting in the context of tumour cell invasion and dissemination in vivo, because migratory breast tumour cells express a unique MENA isoform profile: MENAINV upregulated and MENA11A downregulated99, which dramatically increases the sensitivity of EGFR to EGF by 25–50-fold5,97. Furthermore, MENAINV is essential for transendothelial migration during intravasation5,129. All of these effects seem to result from the ability of MENAINV to sensitize tumour cells to EGF, which amplifies the paracrine interaction with macrophages and results in increased multicellular streaming migration and intravasation in vivo5 (FIG. 3). Importantly, Robinson et al.130 have recently reported that microanatomical structures, which resemble the sites of intravasation observed in mouse mammary tumours by intravital multiphoton imaging, are found in paraffin-embedded tumour tissue from breast cancer patients. These structures, called tumour microenvironment of metastasis (TMEM), contain invasive tumour cells marked by MENA overexpression and perivascular macrophages that are in direct contact with endothelial cells, as observed at sites of intravasation in mouse mammary tumours127 (FIG. 4). The presence of TMEM is significantly correlated with the development of distant organ metastasis in patients with breast cancer130. Recently, it was shown that the presence of TMEM is strongly correlated with MENAINV expression in non-cohesive human breast tumour cells obtained by fine needle aspiration from breast tumours131, supporting the hypothesis that tumour cell–macrophage streams that form in response to MENAINV are involved in TMEM assembly. These findings highlight the clinical relevance of paracrine chemotaxis in tumour cell dissemination.

Figure 4. Multicellular streaming of tumour cells and macrophages leading to intravasation in mammary tumours.

Both streaming migration and intravasation require macrophages. In the metastatic tumour microenvironment shown, initiation of chemotaxis to epidermal growth factor (EGF) that is supplied by macrophages promotes colony-stimulating factor 1 (CSF1) production by tumour cells. Macrophages chemotax towards CSF1, resulting in relay chemotaxis between the two cell types. Relay chemotaxis results in paracrine-dependent carcinoma cell streaming and transendothelial migration. The close proximity of invasive tumour cells, macrophages and endothelial cells leads to the formation of the tumour microenvironment of metastasis (TMEM; dashed box), which has also been found as an anatomical landmark in tumour tissues from patients with breast cancer 130. Black arrows indicate the direction of cell migration, grey arrows indicate the gradient direction of chemotactic factors: from the cell that secretes to the cell that responds to the factor. CSF1R, CSF1 receptor; ECM, extracellular matrix; EGFR, EGF receptor.

Conclusions and perspectives

Given the importance of chemotaxis in cancer, the development of therapeutics targeting chemotaxis is an obvious goal for the cancer research community. The recent development of autonomous chemotaxis devices that can be implanted in tumours to evaluate chemotactic events in vivo will help to define more precisely the importance of specific chemotactic signals in tumour cell migration8. In addition, various compounds are being developed to target many of the factors discussed above and some of them are already in use, whereas others are in clinical trials (Supplementary information S1 (table)). For example, multiple compounds have been developed for the ERBB family of receptors, either as monoclonal antibodies against extracellular domains or as specific tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) targeting intracellular signalling. As far as chemokines and their receptors are concerned, several therapeutics are currently under investigation in multiple clinical trials. Most of these compounds target CXCR4 as it was one of the first chemokine receptors found to be overexpressed in many types of cancer74,132. In addition to receptors and their ligands, compounds targeting downstream effectors of these chemotactic pathways, such as mTOR, PI3K, SRC, MET and MEK, are currently undergoing preclinical and clinical Phase I/II evaluation133. Expression profiling of invasive and metastatic cells from mouse models has identified additional factors that regulate chemotaxis in tumour cells and thus could serve as potential novel therapeutic targets134–137.

The first effort to develop therapeutics specifically targeting the tumour microenvironment resulted in anti-angiogenesis therapy. Several VEGF antagonists are now approved by the US Food and Drug Administration138 and have been shown to increase the survival of patients with metastatic breast and colorectal cancers when combined with standard chemotherapy139,140 (Supplementary information S1 (table)). In addition to targeting VEGF, several compounds targeting chemokines are expected to not only inhibit the migration of tumour cells but also to abolish angiogenesis. For example, CXCR4 is expressed on tumour cells and endothelial cells, and compounds that target this receptor could both inhibit tumour cell migration and angiogenesis. In addition, humanized anti-CXCL8 antibodies inhibited angiogenesis, tumour growth and metastasis in melanoma and bladder cancer xenografts141,142. Neutralization of CCL2 also resulted in reduced metastasis, mainly due to decreased angiogenesis, in breast cancer xenografts112.

Despite the strong experimental evidence for the involvement of the signalling pathways discussed above in chemotaxis and tumour cell dissemination, the therapeutics actively being developed are engineered primarily with growth and proliferation in mind, and thus they are being tested for their ability to reduce the size and growth of primary and/or secondary tumours. This seems problematic because dissemination and growth are not always linked, and therefore useful information regarding any potential benefit of these drugs in preventing dissemination is missed. One reason that chemotaxis and dissemination are not being directly tested is the lack of relevant therapeutic end points in current clinical practice. We speculate that the new insights coming from research on chemotaxis and dissemination will lead to novel end point markers for the evaluation of therapeutics designed to inhibit the pathways of chemotaxis and dissemination. For example, measuring chemotaxis by novel diagnostic devices in patients, counting circulating tumour cells (CTCs) and counting TMEM occurrences are potential end point markers for chemotaxis- and dissemination-directed therapy. In addition, anti-invasion and anti-dissemination therapy may require chronic prophylactic treatment of patients after the initial treatment of the primary tumour. In this scenario, the potential drug will have to be well tolerated for use over many years in order to prevent further dissemination from secondary tumour sites. Even in this setting, treatment will probably have to be combined with therapies that target the growth potential of already disseminated minimal residual disease.

It has been argued that because dissemination from the primary tumour can occur early in cancer progression, potentially before clinical presentation143, anti-invasion and anti-dissemination therapy may not be a plausible target for cancer therapy, but instead that future therapeutics should target the growth of dormant, already disseminated cells144. However, invasion and dissemination can still be clinically relevant targets after resection of the primary tumour, because tumour cells can disseminate from metastatic sites and seed back to the primary tumour site or other metastatic sites145. CTCs can be found in the blood of patients years or decades after the removal of their primary tumour146, suggesting that secondary deposits of tumour cells in the body of the patient can still regularly invade and disseminate into the blood circulation. Additionally, the number of CTCs in the peripheral blood of patients is prognostic for cancer recurrence and poor survival (for example, REFS 147–149), suggesting that these cells are causative for further metastasis. In our opinion, and that of others (for example, REFS 150,151), anti-invasion and anti-dissemination therapy can be combined with other therapies to more effectively manage cancer dissemination and subsequent growth. Such treatments will hopefully lead to efficient long-term management of minimal residual disease without relapse or complicating metastases.

Supplementary Material

At a glance.

Chemotaxis is the phenomenon by which cell movement is directed in response to an extracellular chemical gradient. Factors that mediate chemotaxis are frequently mutated in cancer. Although most of the factors have dual roles in cell growth and survival, they also mediate cytoskeletal dynamics that results in chemotaxis, thus suggesting a potentially important role of chemotaxis in cancer.

Tumour cells in vivo can move both randomly and directionally. However, invasion, migration and dissemination are most efficient when the cell is involved in directed migration. Different modes of directed migration have been described for tumour cells (amoeboid migration or mesenchymal migration for single cells and collective or streaming migration for groups of cells). The occurrence and frequency of these modes of migration in cancer is dependent on the type of cancer and the surrounding factors within the tumour microenvironment.

Despite the various patterns of directed migration during tumour cell dissemination, the intracellular processes that direct the cell motility cycle in response to the chemoattractant are probably similar and are comprised of three steps: chemosensing, polarization and locomotion. First, polarized intracellular signals lead to asymmetric actin polymerization resulting in extension of the cell membrane in the direction of movement, thus creating the leading-edge protrusion. This is followed by integrin-mediated adhesion to the substrate on which the cell is moving, and then by detachment from the substrate and contraction of the trailing edge of the cell.

In addition to cancer cells, directional migration to a chemokine source is observed in stromal cells, which frequently shape the tumour microenvironment to a more pro-metastatic state. A complex network of chemokines and growth factors is involved in the communication of tumour cells with stromal cells. This leads to several major events of cancer progression, such as immune evasion, angiogenesis, invasion and dissemination.

Despite the strong experimental evidence for the involvement of chemotaxis signalling pathways in tumour cell dissemination, therapeutics under development are tested only for their ability to reduce the tumour size in patients with late-stage disease. A lack of relevant therapeutic end points in clinical practice, together with the current belief that dissemination occurs early in tumour progression, before clinical presentation, have brought scepticism to the development of anti-invasion and anti-dissemination drugs.

We speculate that dissemination is not only a feasible but also a necessary therapeutic target if efficient long-term management of minimal residual disease is a goal in cancer treatment. The identification of therapeutic end points relevant to tumour cell dissemination will facilitate the development and appropriate use of therapeutics.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank members of the Condeelis laboratory for helpful discussions. We thank especially J. Wyckoff and D. Entenberg, associates at the Gruss Lipper Biophotonics Center (GLBC) of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, for their critical comments and suggestions for this manuscript and their help in figure preparation. The authors apologize to those whose work is not cited owing to space limitations. The authors’ research is funded by grants CA150344 (to E.T.R), CA100324 (to J.S.C.) and CA113395 (to A.P.) from the US National Institutes of Health.

Glossary

- Chemotaxis

Polarized migration in response to soluble extracellular cues

- Intravasation

The process by which a cell invades through the basement membrane and the endothelium to enter blood vessels

- Extravasation

The process by which a cell exits a blood vessel or capillary to enter a tissue

- Chemokines

A family of inducible chemoattractant cytokines that regulate the chemotaxis of tumour cells and other cell types. Chemokines also affect processes such as proliferation, migration and invasion

- Growth factors

Can be considered chemokines that specifically but not exclusively affect cell proliferation

- Haptotaxis

Migration in response to a solid state, extracellular cue. These cues include graded adhesion within the substrate or anchored chemotactic factors within the extracellular matrix

- Electrotaxis

Migration in response to changes in electric fields

- Durotaxis

Migration in response to mechanical signals within the microenvironment

- Cytokines

Small, secreted proteins produced by immune cells that are used in cellular communication

- Chemosensing

The process by which a cell senses the direction of a gradient source

- Polarization

The process by which a cell becomes polarized towards a sensed gradient source

- Locomotion

Migration towards a gradient source, which involves retraction of the back of the cell

- Amoeboid migration

Leading-edge protrusion of a rounded or ellipsoid cell, usually characterized by many protrusions, which result in a high turning frequency. The formation of a dominant protrusion is followed by the retraction of the trailing edge and the inhibition of randomly directed lateral pseudopod extensions

- Mesenchymal migration

The formation of a single or few actin-rich leading-edge protrusions, usually characterized by a low turning frequency, giving rise to a more polarized cell. Leading-edge protrusion is followed by adhesive interactions of the leading edge with the extracellular matrix, which triggers the contraction of the rear of the cell and finally cell displacement

- Collective migration

The movement of groups of cells with functionally intact cell–cell adhesions that coordinate multicellular leading-edge protrusions and trailing-edge retraction. This type of cell movement usually occurs at very low velocities (~0.1 μm min−1)

- Cell streaming

The movement of a group of individual carcinoma cells, the vector paths of which point in the same direction. Cell movement is usually coordinated by chemotaxis, whereby the cells align and move in single file but do not require intact junctions or even contact between carcinoma cells. Streaming cells have velocities of migration 10–100 times more rapid than cells undergoing collective migration

- Leading-edge protrusion

A protrusion at the leading edge of a cell. The term includes all locomotory protrusions, such as lamellipodia and pseudopodia, that are used by chemotaxing cells

- Invadopodia

Actin-based membrane protrusions with matrix metalloproteinase activity that degrades the extracellular matrix. Shapes of invadopodia vary and can involve either a large area of the leading-edge protrusion when cells are in three-dimensional culture conditions, or small dots on the ventral surface of the cell when cultured in two-dimensional conditions

- Tolerogenic response

An acquired specific failure of the immune system to respond to a given antigen. In the case of cancer, the tumour cells secrete factors that manipulate the immune system into inhibiting cytotoxic activities

- T helper 2

(TH2). T cells that help B cells to make antibodies and suppress the action of cytotoxic T cells. By contrast, T helper 1 (TH1) cells are at the other end of the functional spectrum and activate macrophages and cytotoxic T cells

- Tissue tropism

An affinity of cells or microorganisms for specific host tissues. In cancer it refers to the selectivity of metastasis formation in specific organs

- Relay chemotaxis

The asymmetric propagation of a chemotactic signal, resulting in collective and streaming migration

Footnotes

Competing interests statement

The authors declare competing financial interests: see Web version for details.

References

- 1.Condeelis J, Singer RH, Segall JE. The great escape: when cancer cells hijack the genes for chemotaxis and motility. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2005;21:695–718. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.122303.120306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McSherry EA, Donatello S, Hopkins AM, McDonnell S. Molecular basis of invasion in breast cancer. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64:3201–3218. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7388-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farrow B, Albo D, Berger DH. The role of the tumor microenvironment in the progression of pancreatic cancer. J Surg Res. 2008;149:319–328. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2007.12.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Condeelis J, Segall JE. Intravital imaging of cell movement in tumours. Nature Rev Cancer. 2003;3:921–930. doi: 10.1038/nrc1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roussos ET, et al. Mena invasive (MenaINV) promotes multicellular streaming motility and transendothelial migration in a mouse model of breast cancer. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:2120–2131. doi: 10.1242/jcs.086231. This study demonstrates how a MENA invasion-specific isoform promotes multicellular streaming in vivo in mouse models of breast cancer. This was the first study to define multicellular streaming migration of breast tumour cells in vivo by intravital imaging. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petrie RJ, Doyle AD, Yamada KM. Random versus directionally persistent cell migration. Nature Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:538–549. doi: 10.1038/nrm2729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Provenzano PP, Eliceiri KW, Inman DR, Keely PJ. Engineering three-dimensional collagen matrices to provide contact guidance during 3D cell migration. Curr Protoc Cell Biol. 2010;47:10.17.1–10.17.11. doi: 10.1002/0471143030.cb1017s47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raja WK, Gligorijevic B, Wyckoff J, Condeelis JS, Castracane J. A new chemotaxis device for cell migration studies. Integr Biol. 2010;2:696–706. doi: 10.1039/c0ib00044b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berthier E, Surfus J, Verbsky J, Huttenlocher A, Beebe D. An arrayed high-content chemotaxis assay for patient diagnosis. Integr Biol. 2010;2:630–638. doi: 10.1039/c0ib00030b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Skoge M, et al. Gradient sensing in defined chemotactic fields. Integr Biol. 2010;2:659–668. doi: 10.1039/c0ib00033g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bosgraaf L, Keizer-Gunnink I, Van Haastert PJ. PI3-kinase signaling contributes to orientation in shallow gradients and enhances speed in steep chemoattractant gradients. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:3589–3597. doi: 10.1242/jcs.031781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patel DD, et al. Chemokines have diverse abilities to form solid phase gradients. Clin Immunol. 2001;99:43–52. doi: 10.1006/clim.2000.4997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iglesias PA, Devreotes PN. Navigating through models of chemotaxis. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008;20:35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedl P, Wolf K. Plasticity of cell migration: a multiscale tuning model. J Cell Biol. 2010;188:11–19. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200909003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sahai E. Mechanisms of cancer cell invasion. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2005;15:87–96. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smalley KS, Lioni M, Herlyn M. Life isn’t flat: taking cancer biology to the next dimension. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 2006;42:242–247. doi: 10.1290/0604027.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gaggioli C, et al. Fibroblast-led collective invasion of carcinoma cells with differing roles for RhoGTPases in leading and following cells. Nature Cell Biol. 2007;9:1392–1400. doi: 10.1038/ncb1658. This study demonstrates that fibroblasts lead the collective migration of SCC cells through the generation of tracks in the ECM by degradation or matrix remodelling. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rhee S. Fibroblasts in three dimensional matrices: cell migration and matrix remodeling. Exp Mol Med. 2009;41:858–865. doi: 10.3858/emm.2009.41.12.096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goswami S, et al. Macrophages promote the invasion of breast carcinoma cells via a colony-stimulating factor-1/epidermal growth factor paracrine loop. Cancer Res. 2005;65:5278–5283. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kedrin D, et al. Intravital imaging of metastatic behavior through a mammary imaging window. Nature Methods. 2008;5:1019–1021. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pinner S, Sahai E. Imaging amoeboid cancer cell motility in vivo. J Microsc. 2008;231:441–445. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.2008.02056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Friedl P, Gilmour D. Collective cell migration in morphogenesis, regeneration and cancer. Nature Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:445–457. doi: 10.1038/nrm2720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wolf K, et al. Compensation mechanism in tumor cell migration: mesenchymal–amoeboid transition after blocking of pericellular proteolysis. J Cell Biol. 2003;160:267–277. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200209006. A key paper demonstrating that tumour cells can transition between the two types of single cell migration, amoeboid and mesenchymal, through inhibition of pericellular proteolysis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wyckoff JB, Pinner SE, Gschmeissner S, Condeelis JS, Sahai E. ROCK- and myosin-dependent matrix deformation enables protease-independent tumor-cell invasion in vivo. Curr Biol. 2006;16:1515–1523. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.05.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thiery JP, Acloque H, Huang RY, Nieto MA. Epithelial–mesenchymal transitions in development and disease. Cell. 2009;139:871–890. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nabeshima K, Inoue T, Shimao Y, Sameshima T. Matrix metalloproteinases in tumor invasion: role for cell migration. Pathol Int. 2002;52:255–264. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1827.2002.01343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sahai E, Marshall CJ. Differing modes of tumour cell invasion have distinct requirements for Rho/ROCK signalling and extracellular proteolysis. Nature Cell Biol. 2003;5:711–719. doi: 10.1038/ncb1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pankova K, Rosel D, Novotny M, Brabek J. The molecular mechanisms of transition between mesenchymal and amoeboid invasiveness in tumor cells. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;67:63–71. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0132-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Valentin G, Haas P, Gilmour D. The chemokine SDF1a coordinates tissue migration through the spatially restricted activation of Cxcr7 and Cxcr4b. Curr Biol. 2007;17:1026–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmidt M, et al. EGFL7 regulates the collective migration of endothelial cells by restricting their spatial distribution. Development. 2007;134:2913–2923. doi: 10.1242/dev.002576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lecaudey V, Cakan-Akdogan G, Norton WH, Gilmour D. Dynamic Fgf signaling couples morphogenesis and migration in the zebrafish lateral line primordium. Development. 2008;135:2695–2705. doi: 10.1242/dev.025981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haas P, Gilmour D. Chemokine signaling mediates self-organizing tissue migration in the zebrafish lateral line. Dev Cell. 2006;10:673–680. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aman A, Piotrowski T. Wnt/β-catenin and Fgf signaling control collective cell migration by restricting chemokine receptor expression. Dev Cell. 2008;15:749–761. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rorth P. Collective guidance of collective cell migration. Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17:575–579. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2007.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ilina O, Friedl P. Mechanisms of collective cell migration at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:3203–3208. doi: 10.1242/jcs.036525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wolf K, et al. Multi-step pericellular proteolysis controls the transition from individual to collective cancer cell invasion. Nature Cell Biol. 2007;9:893–904. doi: 10.1038/ncb1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Packard BZ, Artym VV, Komoriya A, Yamada KM. Direct visualization of protease activity on cells migrating in three-dimensions. Matrix Biol. 2009;28:3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clark ES, Whigham AS, Yarbrough WG, Weaver AM. Cortactin is an essential regulator of matrix metalloproteinase secretion and extracellular matrix degradation in invadopodia. Cancer Res. 2007;67:4227–4235. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nabeshima K, et al. Front-cell-specific expression of membrane-type 1 matrix metalloproteinase and gelatinase A during cohort migration of colon carcinoma cells induced by hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor. Cancer Res. 2000;60:3364–3369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Friedl P, Wolf K. Tube travel: the role of proteases in individual and collective cancer cell invasion. Cancer Res. 2008;68:7247–7249. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Farooqui R, Fenteany G. Multiple rows of cells behind an epithelial wound edge extend cryptic lamellipodia to collectively drive cell-sheet movement. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:51–63. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Giampieri S, et al. Localized and reversible TGFβ signalling switches breast cancer cells from cohesive to single cell motility. Nature Cell Biol. 2009;11:1287–1296. doi: 10.1038/ncb1973. This study is the first to show active TGFβ signalling in cells undergoing single cell migration in vivo. Importantly, in distant metastasis TGFβ signalling was found to be inactivated, suggesting that microenvironmental chemotaxis signals in primary tumours are transient. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kriebel PW, Barr VA, Parent CA. Adenylyl cyclase localization regulates streaming during chemotaxis. Cell. 2003;112:549–560. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00081-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kriebel PW, Barr VA, Rericha EC, Zhang G, Parent CA. Collective cell migration requires vesicular trafficking for chemoattractant delivery at the trailing edge. J Cell Biol. 2008;183:949–961. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200808105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li S, Guan JL, Chien S. Biochemistry and biomechanics of cell motility. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2005;7:105–150. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.7.060804.100340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Devreotes P, Janetopoulos C. Eukaryotic chemotaxis: distinctions between directional sensing and polarization. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:20445–20448. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R300010200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Veltman DM, Keizer-Gunnik I, Van Haastert PJ. Four key signaling pathways mediating chemotaxis in Dictyostelium discoideum. J Cell Biol. 2008;180:747–753. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200709180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Annesley SJ, Fisher PR. Dictyostelium discoideum—a model for many reasons. Mol Cell Biochem. 2009;329:73–91. doi: 10.1007/s11010-009-0111-8. References 47 and 48 are comprehensive reviews of how D. discoideum serves as a model for the study of chemotaxis signalling. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Swaney KF, Huang CH, Devreotes PN. Eukaryotic chemotaxis: a network of signaling pathways controls motility, directional sensing, and polarity. Annu Rev Biophys. 2010;39:265–289. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.093008.131228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chung CY, Funamoto S, Firtel RA. Signaling pathways controlling cell polarity and chemotaxis. Trends Biochem Sci. 2001;26:557–566. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)01934-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Janetopoulos C, Firtel RA. Directional sensing during chemotaxis. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:2075–2085. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.04.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.King JS, Insall RH. Chemotaxis: finding the way forward with Dictyostelium. Trends Cell Biol. 2009;19:523–530. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jin T, et al. How human leukocytes track down and destroy pathogens: lessons learned from the model organism Dictyostelium discoideum. Immunol Res. 2009;43:118–127. doi: 10.1007/s12026-008-8056-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zicha D, et al. Chemotaxis of macrophages is abolished in the Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome. Br J Haematol. 1998;101:659–665. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1998.00767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Weiner OD. Regulation of cell polarity during eukaryotic chemotaxis: the chemotactic compass. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2002;14:196–202. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00310-1. A comprehensive review of the signalling components that regulate chemosensing and polarization. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mouneimne G, et al. Spatial and temporal control of cofilin activity is required for directional sensing during chemotaxis. Curr Biol. 2006;16:2193–2205. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.09.016. This study demonstrates that local activation of cofilin by PLC and its global inactivation by LIMK1 phosphorylation combine to generate a local asymmetry of actin polymerization that is required for chemotaxis. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]