Abstract

Cellular production of flavonoid glucuronides requires the action of both UDP-glucuronosyltransferases (UGT) and efflux transporters since glucuronides are too hydrophilic to diffuse across the cellular membrane. We determined the kinetics of efflux of 13 flavonoid glucuronides using the newly developed HeLa-UGT1A9 cells and correlated them with kinetic parameters derived using expressed UGT1A9. The results indicated that among the seven monohydroxyflavones (HFs), there was moderately good correlation (r2≥0.65) between fraction metabolized (fmet) derived from HeLa-UGT1A9 cells and CLint derived from the UGT1A9-mediated metabolism. However, there was weak or no correlation between these two parameters for six dihyroxylflavones (DHFs). Furthermore, there was weak no correlation between various kinetic parameters (Km, Vmax or CLint) for the efflux and the metabolism regardless if we were using 7 HFs, 6 DHFs or a combination thereof. Instead, cellular excretion of many flavonoids glucuronides appears to be controlled by the efflux transporter, and poor affinity of glucuronide to the efflux transporter resulted in major intracellular accumulation of glucuronides to a level that is above the dosing concentration of its aglycone. Hence, the efflux transporters appear to act as the “Revolving Door” to control the cellular excretion of glucuronides. In conclusion, the determination of a flavonoid's susceptibility to glucuronidation must be based on both its susceptibility to glucuronidation by the enzyme and resulting glucuronide's affinity to the relevant efflux transporters, which act as the “Revolving Door(s)” to facilitate or control its removal from the cells.

Keywords: UGT, BCRP, Flavonoid, Glucuronide, Excretion, Structure-Activity Relationship

INTRODUCTION

Glucuronidation is a significant phase II metabolic pathway responsible for the elimination of a variety of endogenous and exogenous chemicals including drugs, hormones, and dietary phytochemicals such as polyphenols and flavonoids1. Cellular glucuronide production is a two-step process, the formation of glucuronides catalyzed by various UGT isoforms, and excretion of glucuronides enabled by various anion transporting efflux transporters such as BCRP and MRPs1. Efflux transporters were thought to act as a “Revolving Door” for facilitating and/or controlling the cellular glucuronide excretion. Therefore, a thorough understanding of the cellular glucuronide production process usually involves delineation of the glucuronidation steps that involve the relevant UDP-glucuronosyltransferases (UGTs) and subsequent glucuronide efflux steps by various efflux transporters. This understanding is important for the development of predictive algorithm useful for selecting drug candidates based on their metabolic susceptibility, because their bioavailability and drug interaction potentials are dependent on their metabolic susceptibility.

Towards this predictive goal, investigators including ourselves have spent significant effort in understanding and determining the structure-metabolic activity relationship (SAR) between chemical structures and glucuronidation rates by a specific UGT isoform2-8. In addition, a few reports have shown that glucuronidation rates in tissue microsomes (e.g., liver microsomes) is directly correlated with the expression patterns of various UGT isoforms and activity of each isoform9-11. Therefore, investigators have made significant strides in predicting glucuronidation rates of compounds by one or several major UGT isoforms.

Unlike the structural activity relationships demonstrated using various UGT isoforms such as UGT1A15 and UGT1A96, very little is known about the structural activity relationship of glucuronide efflux by an efflux transporter. Although several types of membrane vesicles overexpressing a particular type of responsible efflux transporter (e.g., BCRP or MRPs) have been used to shown that these efflux transporters are capable of mediating the efflux of various organic anions, an actual structural activity relationship has not been established for glucuronides. This is largely because of the lack of commercially available glucuronide standards needed to conduct the aforementioned studies.

Recently, we have developed a new tool: HeLa-UGT1A9 cells, which should allow us to determine the structure activity relationship without purified glucuronide standards12. In these cells, we found that intracellular concentrations of glucuronides could rapidly reach steady state (usually within 30 min), which in turn allows the determination of the steady state efflux rates12. The latter will allow us to determine the kinetic parameters associated with the dominating efflux transporters, a necessary step to delineate the structure-activity relationship (i.e., glucuronide efflux SAR). We also found that HeLa-UGT1A9 cells mainly used BCRP as its efflux transporter for flavonoid glucuronides using both molecular and kinetic characterization (using Ko143 as inhibitor). Specifically, complete inhibition of this transporter decreases flavonoid glucuronide clearance by more than 95%. We also found that MRP2 and MRP3 did not make significant contribution to the efflux of flavonoid glucuronides, using siRNAs and a chemical inhibitor of MRPs (LTC4)13. Therefore, these cells are used here to determine the SAR for BCRP mediated efflux of flavonoid glucuronides.

We have chosen flavone glucuronides as the model compounds for the present studies because flavonoids appear to possess a wide variety of biological activities in the areas of anticancer, anti-ageing, and anti-inflammation, all of which may be related to their antioxidant effects and glucuronides retain antioxidant activities. However, their development into therapeutic agents is severely challenged by the lack of oral bioavailability, mainly due to extensive phase II metabolism via glucuronidation and sulfonation. Therefore, we hypothesized that a better understanding of flavonoid glucuronidation process will reveal novel means of improving their oral bioavailability. Here, we studied BCRP-mediated efflux of 13 flavone glucuronides (Fig. 1), seven derived from mono-hydroxyl-flavones, and six di-hydroxyl-flavones in order to understand how changes in flavone glucuronide structures affect BCRP-mediated glucuronide efflux.

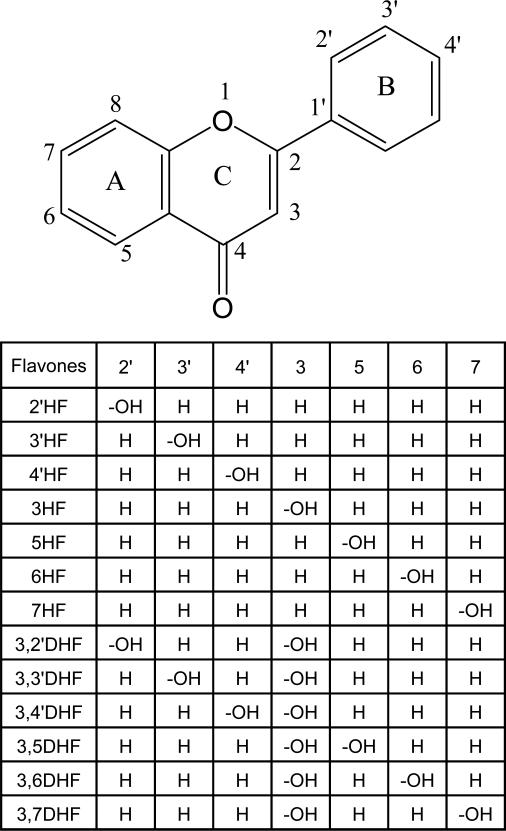

Fig. 1. Structures of seven mono-hydroxyflavones and six dihydroxyflavones.

Shown in the scheme are structures of aglycone forms of hydroxyflavone analogs.

Glucuronidated metabolites may be formed at the 5, 6, or 7 phenolic group on the A ring, or 2′-OH, 3′-OH or 4′-OH phenolic group on the B ring, or 3-OH group on the C ring.

2′-Hydroxyflavone (2′HF), 3′-Hydroxyflavone (3′HF),

4′-Hydroxyflavone (4′HF), 3-Hydroxyflavone (3HF),

5-Hydroxyflavone (5HF), 6-Hydroxyflavone (6HF),

7-Hydroxyflavone (7HF), 3,2′-Dihydroxyflavone (3,2′DHF),

3,3′-Dihydroxyflavone (3,3′DHF), 3,4′-Dihydroxyflavone (3,4′DHF),

3,5-Dihydroxyflavone (3,5DHF), 3,6-Dihydroxyflavone (3,6DHF),

3,7-Dihydroxyflavone (3,7DHF).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Human UGT1A9-overexpressing HeLa cells (hereon referred to HeLa-UGT1A9 cells in this paper) were described previously12. Human BCRP (Arg482) membrane vesicles and expressed human UGT1A9 were purchased from BD Biosciences (Woburn, MA). 2'-Hydroxyflavone (2'HF), 3'-Hydroxyflavone (3'HF), 4'-Hydroxyflavone (4'HF), 3-Hydroxyflavone (3HF), 5-Hydroxyflavone (5HF), 6-Hydroxyflavone (6HF), 7-Hydroxyflavone (7HF), 3,5-dihydroxyflavone (3,5DHF), 3,6-dihydroxyflavone (3,6DHF), 3,7-dihydroxyflavone (3,7DHF), 3,2′-dihydroxyflavone (3,2′DHF), 3,3′-dihydroxyflavone (3,3′DHF), and 3,4′-dihydroxyflavone (3,4′DHF) were purchased from Indofine Chemicals (Hillsborough, NJ). All other chemicals and solvents (analytical grade or better) were used as received.

Cell Culture

Conditions for culture and maintenance of HeLa-UGT1A9 cells were described previously and used without alteration12. Cells from 3 days post-seeding were used for the glucuronide excretion experiments described below. Detailed molecular characterization of our UGT1A9 stably expressed Hela cells was performed previously12. The numbers of cells were correlated to protein concentrations of harvested cells, which is determined using a protein assay kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) using bovine serum albumin as the standard. To determine the intracellular concentration of glucuronides based on amount of glucuronides present inside cells, HeLa cell volume was estimated to be 4μl/mg protein12.

Excretion Experiments

Before experiments, the HeLa-UGT1A9 cells were washed twice with 37°C HBSS buffer (Hank's balanced salt solution, pH=7.4). The cells were then incubated in HBSS buffer containing one of the seven mono-hydroxyflavones (2'-, 3'-, 4'-, 3-, 5-, 6- and 7HF) or one of the six dihydroxyflavones (3,2′-, 3,3′-, 3,4′-, 3,5-, 3,6- and 3,7DHF) (defined as the “loading solution”) for a predetermined time interval (shown in Table S1, Supplemental Data) at 37°C. In the loading solution, the final flavone concentration was derived by the dilution of a (100X) concentrated stock solution (DMSO/Methanol=1:4) to ensure constant organic solvent content in all transport experiments. The sampling times were selected to ensure that the amounts excreted vs. time plots stay in the linear range. At each time point, 200 μl of incubating media from each well were collected as samples and an equal volume of loading solutions was used to replenish each well. The collected samples were each mixed with a 50μl “Stop Solution,” which is consisted of 94% acetonitrile and 6% acetic acid. Supernatants were ready for UPLC analysis after centrifugation (15min at 15,000 rpm).

Determination of Concentration of Intracellular Glucuronides in HeLa-UGT1A9 Cells

At the end of an excretion experiment, HeLa –UGT1A9 cells were washed twice with an ice-cold HBSS buffer to remove the extracellular aglycone and conjugates. The cells were then removed and collected in 120 or 200 μl HBSS buffer. In an ice-cold water bath (4°C) collected cells were lyzed in an Aquasonic 150D sonicator (VWR Scientific, Bristol, CT) operating at the maximum power (135 average watts) for 30min to ensure the release of aglycone and conjugates for measurement14. In the lysate, no further metabolism is expected since UGT1A9 in cellular lysate will not function without the co-factor, UDP-glucuronic acid. After centrifugation at 15,500 rpm for 20min, supernatants (100 μl) were collected and mixed with the Stop Solution (25 μl). The treated samples are ready for UPLC analysis after centrifugation (15min at 15,000 rpm) to remove larger particles and cellular debris.

Vesicular Transport Studies for BCRP

Vesicular transport studies were performed with rapid filtration techniques as described previously15-17. In brief, membrane fractions containing inside out efflux transporters were incubated in the presence or absence of 5 mM ATP in a buffer containing 10 mM MgCl2 and 10 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.4). The transport was stopped by addition of 1ml of cold transport buffer to the membrane suspensions and then rapidly filtered through class F glass fiber filters (pore size, 0.45 μm). Filters were washed with 2× 5 ml of ice-cold wash buffer, cut and transferred to a 1.5-ml Eppendorf tube containing 400 μl of 50% methanol, followed by sonicating for 15min. After centrifugation at 15,000 rpm for 15 min, the supernatant was subjected into UPLC quantitative analysis. ATP-dependent transport was calculated by subtracting the values obtained in the presence of AMP from those in the presence of ATP.

Sample Analysis by UPLC

The conditions for UPLC analysis of HFs, DHFs and their respective glucuronides were modified based on a previously published method10. The conditions were: system, Waters Acquity™ UPLC with a binary pump and a 2996 DPA diode array detector (DAD, Waters, Milford, MA); column, BEH C18 column (50×2.1mm I.D.1.7 μm, Waters, Milford, MA); mobile phase A, 2.5mM ammonium acetate (pH 7.4); mobile phase B, 100% acetonitrile; gradient, 0-2 min (10-20%B), 2-3 min (20-40%B), 3-3.5 min (40-50%B), 3.5-4 min (50-90%B), 4-4.5 min (90%B), 4.5-5 min (90-10%B); injection volume, 10ul; detection wavelength for HFs, DHFs and their glucuronides were also shown in Table S1. The precision and accuracy were typically within acceptable range (<15%). The detection limits were at least 0.2 μM for both flavones and their glucuronides. The structures of glucuronides were further confirmed by the “UV spectrum maxima (λmax) shift method” and UPLC-MS/MS as previously shown18,12,10. Quantitation of the glucuronide was based on the standard curve of the parent compound and further calibrated using the conversion factor as described earlier12,19,7. Conversion factors of 13 flavone glucuronides were also showed in Table S1 (Supplemental Data).

Biosynthesis of Glucuronides

The flavonoid glucuronides used in this study were biosynthesized using Sprague Dawley rat liver microsomes. The rat microsomes were obtained as described earlier (Chen et al., 2005b). The prepared glucuronide solution underwent liquid-liquid extraction using methylene chloride to remove the remaining aglycone. The resultant aqueous phase was then subjected to C-18 solid phase extraction using J.T. Baker Speedisk®48 Pressure Processors (Phillipsburg, NT). The column was conditioned with 4 ml of methanol followed by 2 ml of water. After loading the sample, polar impurities were removed with 2 ml water and the final elution was performed with 4 ml methanol. The methanol was evaporated and the remaining aqueous sample dissolved in ~4 ml of water. Glucuronide was isolated by collecting effluent from a preparative column (Phenomenex, Luna C18, 5 μm particle size, 250 × 10 mm) using an HPLC system (1050 series, Hewlett Packard). The mobile phase A was 100% water, mobile phase B was 100% acetonitrile. Gradient: 0 min: 10%B; 0-1hr: 10%-30%B. Multiple injections were made until the entire sample was isolated. The glucuronide solution was then lyophilized to remove the mobile phase.

Data Analysis

Glucuronide efflux by BCRP in HeLa-UGT1A9 cells was verified to be linear with respect to incubation time (within the planned experimental period, see Table S1, Supplemental Data) and protein concentration (excretion rates were expressed as amounts of glucuronides effluxed per min per mg protein or pmol/min/mg). The intracellular concentrations (at the end of experiment) of glucuronides were determined at the end of each efflux experiment for each loading concentration. Correlation plots between efflux rates and intracellular concentrations would allow the determination of the kinetic parameters of BCRP-mediated efflux using a variety of kinetic equations. The actual equation used is based on the shape of the Eadie-Hofstee plots. The most common equation is the Michaelis-Menten equation.

| equation (1) |

where Km (substrate concentration at which half maximal velocity is achieved) represents the Michaelis constant, and Vmax is the maximum excretion rate. If Eadie-Hofstee plots showed characteristic profiles of atypical kinetics such as autoactivation or biphasic kinetics20,21, the data were fit to the corresponding equations as described previously22. Kinetics parameters for glucuronide excretion were performed with Microsoft Excel add-in program for modeling steady-state enzyme kinetics12, the goodness of fit was evaluated on the basis of coefficient of determination (R2), Akaike's information criterion (AIC)23, weighted sum of squared residual (WSS), and the rule of parsimony was applied. After the kinetic parameters were determine, the intrinsic clearance (CLint=Vmax/Km) was calculated, and used to estimate the efficiency of the efflux transporter. Previously, intrinsic clearance is often used to predict the in-vivo pharmacokinetics of a drug using in vitro data. To facilitate the comparison, we used Km, Vmax and CLint for glucuronide efflux and Km’, Vmax’ and CLint’ for UGT-1A9-mediated glucuronidation.

Calculation of fmet Value

Fraction metabolized or fmet value was defined as the fraction of dose metabolized (equation (2) at the end of the experiment. The fmet value was considered as the more appropriate parameter to reflect the extent of metabolism in intact cells in the presence of a transporter-enzyme interplay16:

| equation (2) |

Statistical Analysis

One-Way ANOVA was used to determine if the difference was statistically significant. The significance value was set at 0.05 or p<0.05.

RESULTS

Kinetics of HF Glucuronide Efflux in HeLa-UGT1A9 Cells

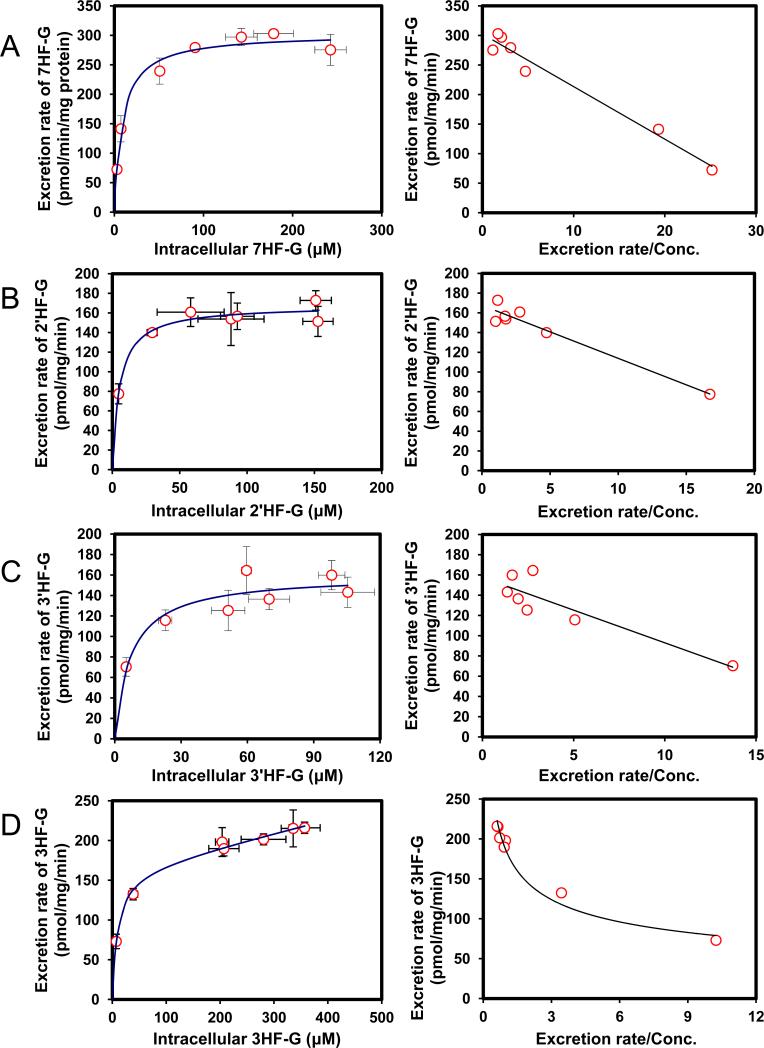

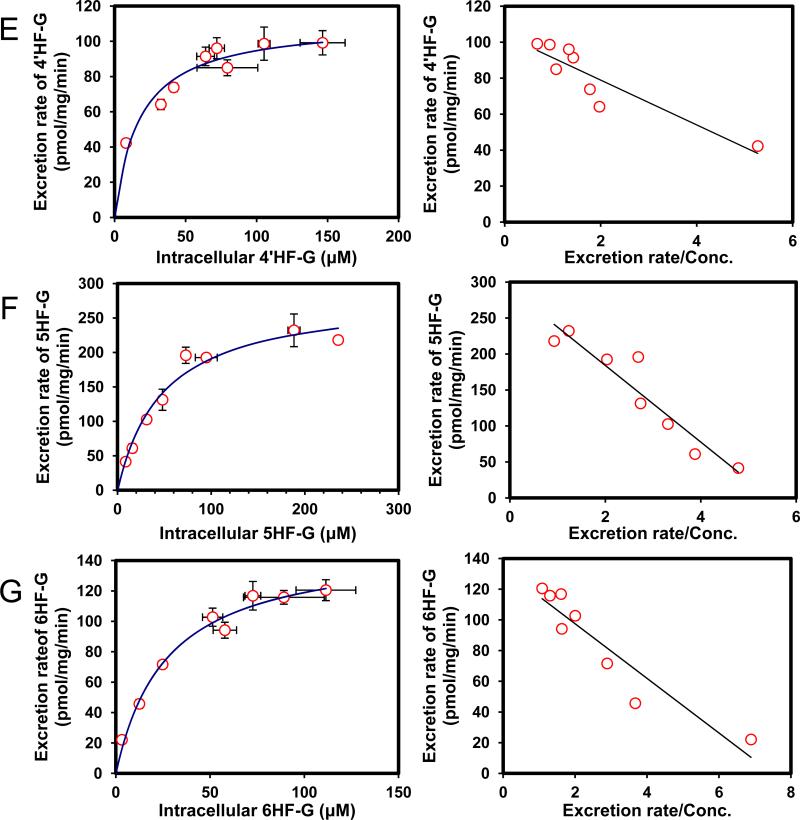

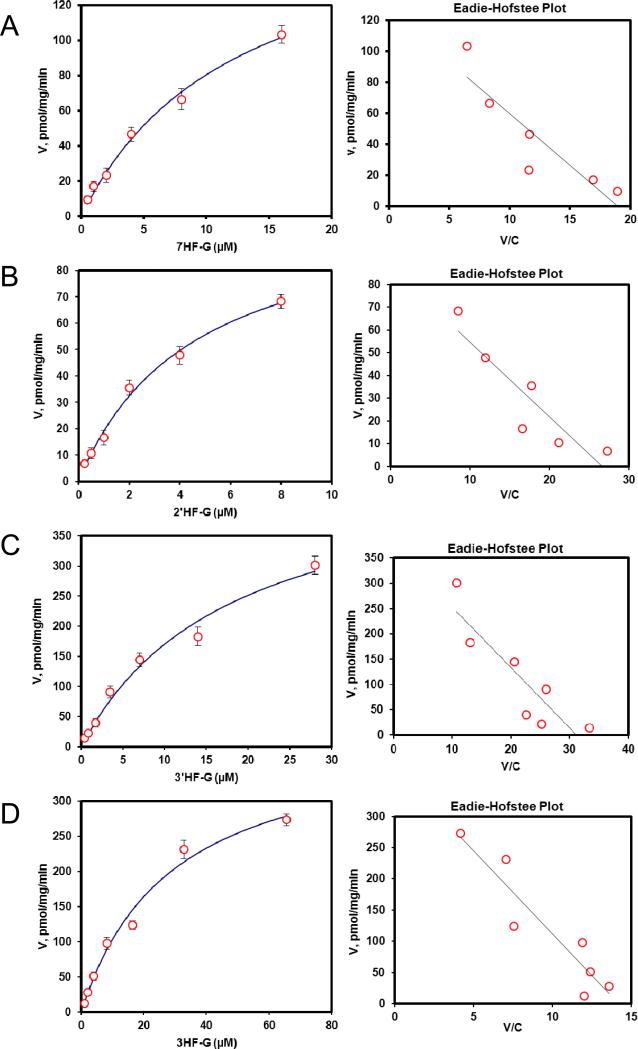

Efflux of glucuronides usually increased with intracellular concentration of glucuronides (Fig.2). Among the seven HF (mono-hydroxyflavones) glucuronides, all but one (3HF- glucuronide) displayed classical Michaelis-Menten kinetics, which is signified by a linear increase in the rate of efflux at low intracellular concentration, and plateauing rate of efflux at high intracellular concentrations (Fig.2). Interestingly, the intracellular concentration of HF glucuronides always increased with loading concentration at lower concentration (≤5 μM) but at higher concentrations, the intracellular concentrations either increased or fluctuated (Fig.3). The increase in intracellular concentration was expected since saturation of the efflux transporter leads to enhanced intracellular accumulation of glucuronides.

Fig. 2. Kinetics profiles of BCRP-mediated efflux of seven HFs glucuronides (A, 7HF-G; B, 2′HF-G; C, 3′HF-G; D, 3HF-G; E, 4′HF-G; F, 5HF-G; G, 6HF-G) (left) and corresponding Eadie-Hofstee plots for each kinetic profile (right).

For Fig.2 and 6, solid lines (left) denote excretion rate of flavone glucuronides. Each data point represents the average of three replicates, and error bars are the standard deviations of the mean (n=3). “Conc.” is the abbreviation for concentration.

Fig. 3. Intracellular HFs-G concentrations as a function of loading HFs concentration (A, 7HF; B, 2′HF; C, 3′HF; D, 3HF; E, 4′HF; F, 5HF; G, 6HF).

Each bar represents the average of three replicates, and error bars are the standard deviations of the mean (n=3). The symbol “*” means the difference between concentrations for each compound was statistically significant according to a one-way ANOVA test.

We then determined efflux of 7 HF-glucuronides in HeLa-UGT1A9 cells, and found that three HF glucuronides (i.e., glucuronides of 6HF, 5HF and 4’HF) displayed Km value greater than 17 μM whereas the other 4 displayed Km values that were less than 9.8 μM (Table 1). The smallest Km value 5.4 μM (for 2’HF-glucuronide) was 9 times smaller than the highest Km value (5HF glucuronide) (Table 1). In contrast, the Vmax values differed by only 2.7 fold, with the largest value of 303 pmol/min/mg protein (for 7HF-glucuronide) and smallest value of 111 pmol/min/mg protein (for 4’HF-glucuronide). The fastest intrinsic clearance value for efflux was 33.6 μl/min/mg protein (for 7HF-glucuronide) and the smallest was 5.6 μl/min/mg protein (for 6HF-glucuronide), a 6 fold difference (Table 1).

Table 1.

The efflux kinetic parameters for glucuronides of seven mono-hydroxyflavones by BCRP, and the comparison between BCRP-mediated efflux of HFs-G and UGT1A9-mediated glucuronidation of HFs.

| BCRP | Km (μM) | Vmax (pmol/mg/min) | CLint (Vmax/ Km) (μl/mg/min) | Log(CLint) | Kinetic type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6HF-G | 26.8±4.8 | 151.0±8.6 | 5.6 | 0.75 | MM |

| 5HF-G | 48.5±9.7 | 283.4±20.0 | 5.8 | 0.77 | MM |

| 4′HF-G | 17.5±4.7 | 111.2±6.9 | 6.4 | 0.80 | MM |

| 3HF-G | 9.7±1.9 | 165.6±10.1 | 17.1 | 1.23 | BL |

| 3′HF-G | 5.6±2.8 | 128.1±10.0 | 22.9 | 1.36 | MM |

| 2′HF-G | 5.4±1.1 | 167.7±4.4 | 31.2 | 1.49 | MM |

| 7HF-G | 9.0±1.5 | 302.9±8.6 | 33.6 | 1.53 | MM |

| Max/Min | 9.0 | 2.7 | 6.0 | 0.8 |

| UGT1A9 | Km′ (μM) | Vmax′ (pmol/mg/min) | CLint′(Vmax′/ Km′) (μl/mg/min) | Log(CLint)′ | Kinetic type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6HF* | 2.27 | 76.1 | 34 | 1.53 | MM |

| 5HF* | 0.96 | 118 | 123 | 2.09 | MM |

| 4′HF* | 1.46 | 98.7 | 67.6 | 1.83 | MM |

| 3HF* | 0.30 | 2100 | 7000 | 3.84 | MM |

| 3′HF* | 2.02 | 926 | 458 | 2.66 | MM |

| 2′HF* | 0.40 | 74.4 | 186 | 2.27 | MM |

| 7HF* | 3.59 | 4895 | 1364 | 3.13 | MM |

| Max/Min | 12.0 | 65.8 | 208.8 | 2.3 |

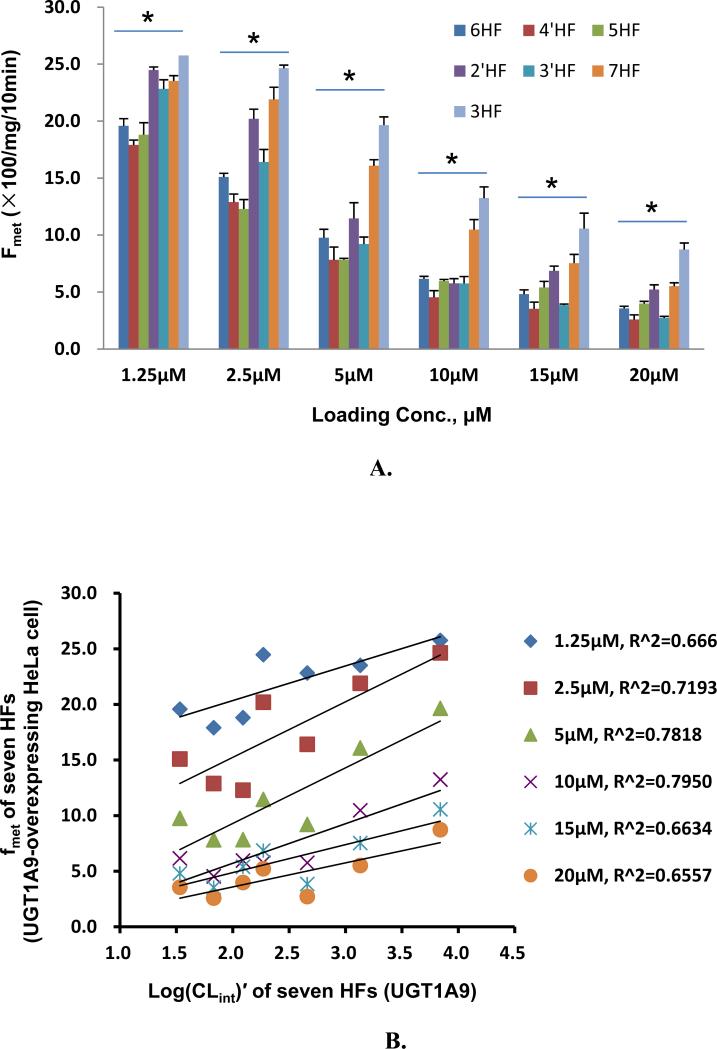

We also compared the efflux kinetic parameters with kinetic parameters for UGT1A9-mediated glucuronidation (Table 1), which were previously published6, and the results showed that kinetic profiles were very similar in that they all shared classical Michaelis-Menten kinetics with the exception of 3-HF, whose efflux obeyed biphasic kinetics (Table 1) but whose glucuronidation followed the classical Michaelis-Menten kinetics. Using fmet as an indicator of cellular glucuronidation capability, we were able to show that fmet values decreased with increasing substrate concentration (Fig.4A), consistent with saturation of UGT1A9 and/or efflux transporter BCRP. We also plotted the fmet values at various concentrations against the CLint’ values of glucuronidation of various substrates by UGT1A9 , and found that there was weak correlation (r2 values in the range of 0.66-0.80) between fmet values of HF in intact HeLa-UGT1A9 cells and CLint’ values of glucuronidation for HF using UGT1A9 isoform.

Fig. 4. Correlation between loading concentrations and metabolic efficiency or fmet of HeLa-UGT1A9 cells or CLint of UGT1A9.

Fig.4A plots fmet values for seven HFs at six loading concentrations to contrast the effects of structural changes on fmet values. For Fig. 4A, each bar represents the average of three replicates, and error bars are the standard deviations of the mean (n=3). Fig. 4B plots correlation between fmet values derived from UGT1A9-overexpressing HeLa cell and Log(CLint)′ derived from commercial UGT1A9 of seven HFs (2′HF, 3′HF, 4′HF, 3HF, 5HF, 6HF, 7HF). Correlation coefficients were calculated for each of the tested concentrations. Each data point represents the average of three replicates (n=3). The symbol “*” means the difference between compounds within each concentration was statistically significant according to a one-way ANOVA test.

Kinetics of HF Glucuronide Efflux in BCRP-overexpressing Membrane Vesicles

We determined kinetic parameters for efflux of 7 mono-hydroxyflavone glucuronides (HF-Gs) using BCRP-overexpressing membrane vesicles (Fig. 5). We found that the Km values of most of the seven HF-Gs were similar (difference<3 fold) between membrane vesicles generated and HeLa-UGT1A9 cells generated. The smallest differences (by less than 50%) were for 6HF-G, 4’HF-G, 2’HF-G and 7HF-G, and the largest difference for 5HF-G (>10 fold) (Table 2). The two compounds in the middle (3HF-G and 3’HF-G) had a difference of approximately 3 fold.

Fig.5. Kinetic profiles of BCRP-mediated efflux of seven HF glucuronides.

The concentration versus rate plots are on the left and corresponding Eadie-Hofstee plots for each kinetic profile are on the right. Each data represents the average of three replicates, and error bars are the standard deviations of the mean (n=3).

Table 2.

Comparison of the efflux kinetic parameter Km for glucuronides of seven mono-hydroxyflavones by BCRP membrane vesicles and HeLa-UGT1A9 cells.

| Model/Flavonoid | 6HF-G | 5HF-G | 4′HF-G | 3HF-G | 3′HF-G | 2′HF-G | 7HF-G |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vesicles | 23.4 | 2.9 | 15.4 | 29 | 18.2 | 4.6 | 12.6 |

| HeLa-UGT1A9 | 26.8 | 48.5 | 17.5 | 9.7 | 5.6 | 5.4 | 9.0 |

Kinetics of DHF Glucuronide Efflux in HeLa-UGT1A9 Cells

In our study of glucuronidation of DHFs, we found that likelihood of glucuronidation found using monohydroxyflavones or HFs could usually be extended to DHFs. For example, 3HF was glucuronidated at a much faster rate than 5HF (Table 1), and hence glucuronidation of 3,5-DHF usually occurred at the 3-OH position with no measurable glucuronidation at 5-OH position (Table 3). Furthermore, the addition of an OH group on the flavonoid backbone could increase or decrease a compound's susceptibility, depending on the site of substitution. In the current study, we investigated if tendencies in the efflux of O-glucuronide of HF could be extended to the efflux of O-glucuronide of DHF, as would be expected based on SAR of glucuronidation.

Table 3.

The efflux kinetic parameters for glucuronides of six dihydroxyflavones by BCRP, and the comparison between BCRP-mediated efflux of DHFs-3-O-G and UGT1A9-mediated glucuronidation of DHFs.

| BCRP | Km (μM) | Vmax (pmol/mg/min) | CLint(Vmax/ Km) (μl/mg/min) | Log(CLint) | Kinetic type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3HF-G | 9.7±1.9 | 165.6±10.1 | 17.1 | 1.23 | BL |

| 3,6DHF-3-O-G | 31.9±7.1 | 34.7±1.3 | 1.1 | 0.04 | MM |

| 3,4′DHF-3-O-G | 35.9±11.9 | 86.0±5.4 | 2.4 | 0.38 | MM |

| 3,2′DHF-3-O-G | 35.9±14.9 | 99.4±25.4 | 2.8 | 0.44 | SI |

| 3,3′DHF-3-O-G | 45.2±16.1 | 183.1±12.6 | 4.1 | 0.61 | MM |

| 3,5DHF-3-O-G | 12.8±2.9 | 67.3±6.2 | 5.3 | 0.72 | BL |

| 3,7DHF-3-O-G | 3.5±0.9 | 24.3±1.5 | 7.0 | 0.84 | MM |

| Max/Min | 13.0 | 7.5 | 6.4 | 0.8 |

| UGT1A9 | Km′ (μM) | Vmax′ (pmol/mg/min) | CLint′(Vmax′/ Km′) (μl/mg/min) | Log(CLint)′ | Kinetic type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3HF* | 0.30 | 2100 | 7000 | 3.84 | MM |

| 3,6DHF* | 0.62 | 13000 | 20968 | 4.34 | MM |

| 3,4′DHF* | 0.13 | 1800 | 13846 | 3.77 | MM |

| 3,2′DHF* | 0.67 | 52 | 78 | 1.89 | MM |

| 3,3′ DHF* | 0.11 | 3100 | 28182 | 4.44 | MM |

| 3,5 DHF* | 0.25 | 1900 | 7600 | 3.88 | MM |

| 3,7DHF(3-OH)* | 0.22 | 4600 | 20909 | 4.32 | SI |

| Max/Min | 6.1 | 250.0 | 363.1 | 2.6 |

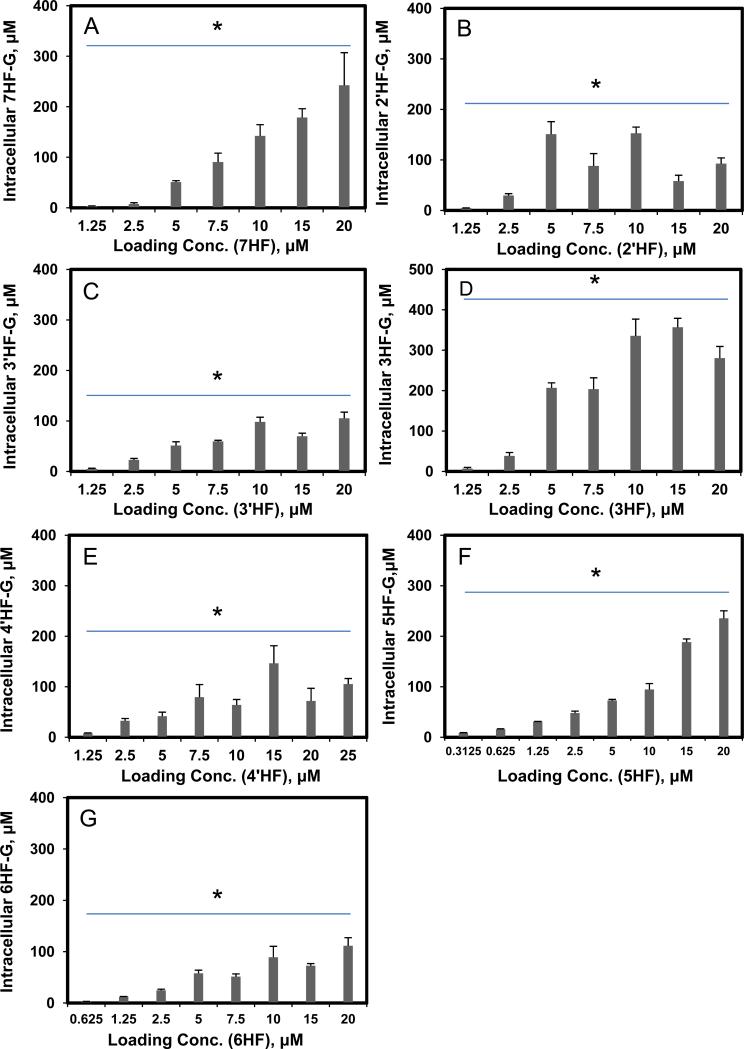

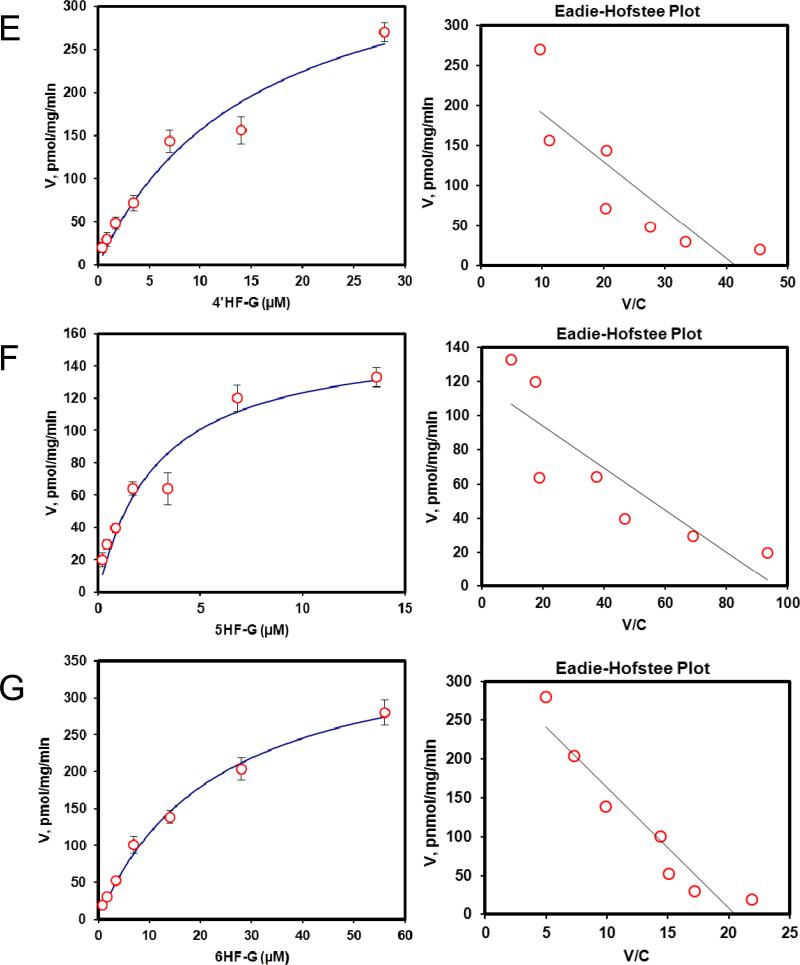

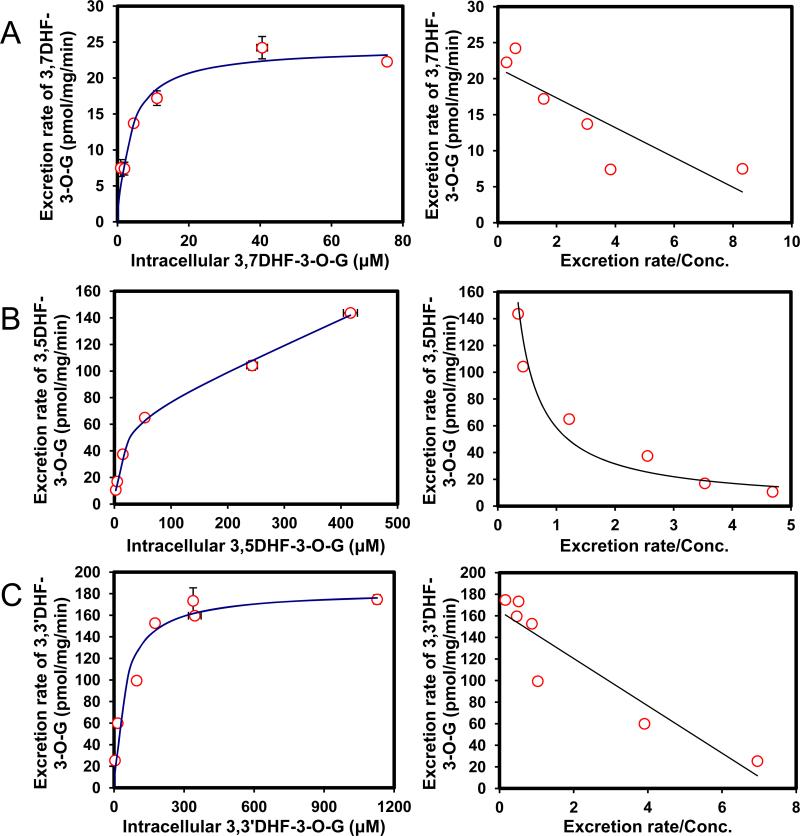

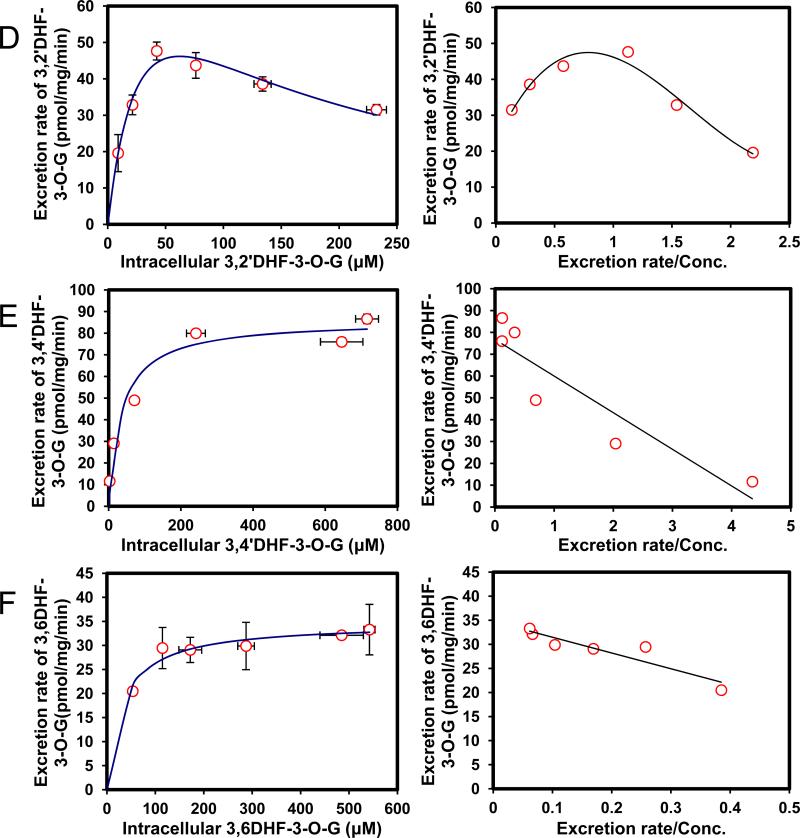

Efflux of 6 DHF glucuronides was determined using the HeLa-UGT1A9 cells (Fig. 6). All six DHF has a 3-OH group and only one DHF (i.e., 3,7-DHF) formed two metabolites. Because our interest is to determine the SAR for BCRP-mediated efflux of 3-O-glucuronide, the efflux of 7-O-glucuronide of 3,7-DHF would not be discussed here. Among the six 3-O-glucuronides of DHF, only hydroxyl group at the 7 position increased the affinity to BCRP (smaller Km value), when compared to 3HF-O-glucuronide. Substitution at 5-OH position had very little impact on Km values, whereas substitution at other four positions substantially decreased the affinity to BCRP (Km values higher by 100% or more, Table 3). On the other hand, all but one substitution (3’-OH) decreased Vmax value, and as a consequence, CLint values of glucuronide efflux were much smaller for 3–O-glucuronides of six DHF than 3-O-glucuronide of 3HF. In addition, the efflux kinetic profiles of DHF-3-O-glucuronides were mostly different from that of 3HF glucuronide, except for 3,5DHF, which shared the same profile (biphasic) as 3HF glucuronide. Hence, the efflux of DHF glucuronides was generally different from 3HF glucuronide, and cannot be predicted based on efflux of HF glucuronides.

Fig. 6. Kinetics profiles of BCRP-mediated efflux of six DHFs glucuronides (A,3,7DHF-3-O-G; B, 3,5DHF-3-O-G; C, 3,3′DHF-3-O-G; D, 3,2′DHF-3-O-G, E, 3,4′DHF-3-O-G and F, 3,6DHF-3-O-G) (left) and corresponding Eadie-Hofstee plots for each kinetic profile (right).

Each data represents the average of three replicates, and error bars are the standard deviations of the mean (n=3).

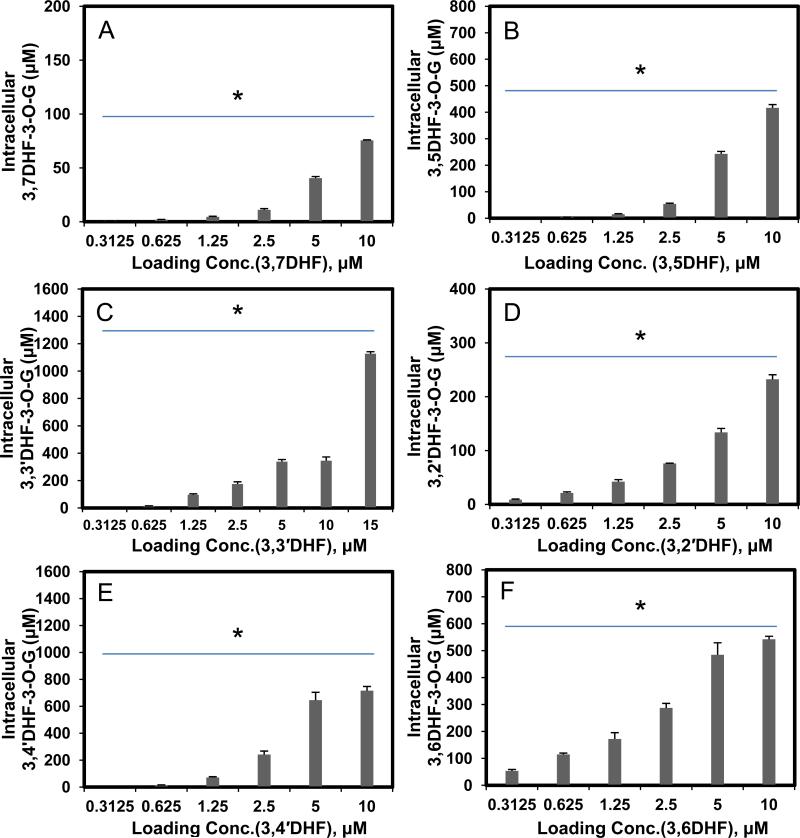

We also measured the intracellular concentrations of glucuronides as a function of loading concentration, and we were able to show that at concentration below or at 5 μM, intracellular concentrations always increased with loading concentration (Fig. 7), similar to our observations using seven HFs.

Fig. 7. Intracellular concentration of DHF glucuronides as a function of concentrations (A,3,7DHF; B, 3,5DHF; C, 3,3′DHF; D, 3,2′DHF; E, 3,4′DHF and F, 3,6DHF).

Each bar represents the average of three replicates, and error bars are the standard deviations of the mean (n=3). The symbol “*” means the difference between concentrations for each compound was statistically significant according to a one-way ANOVA test.

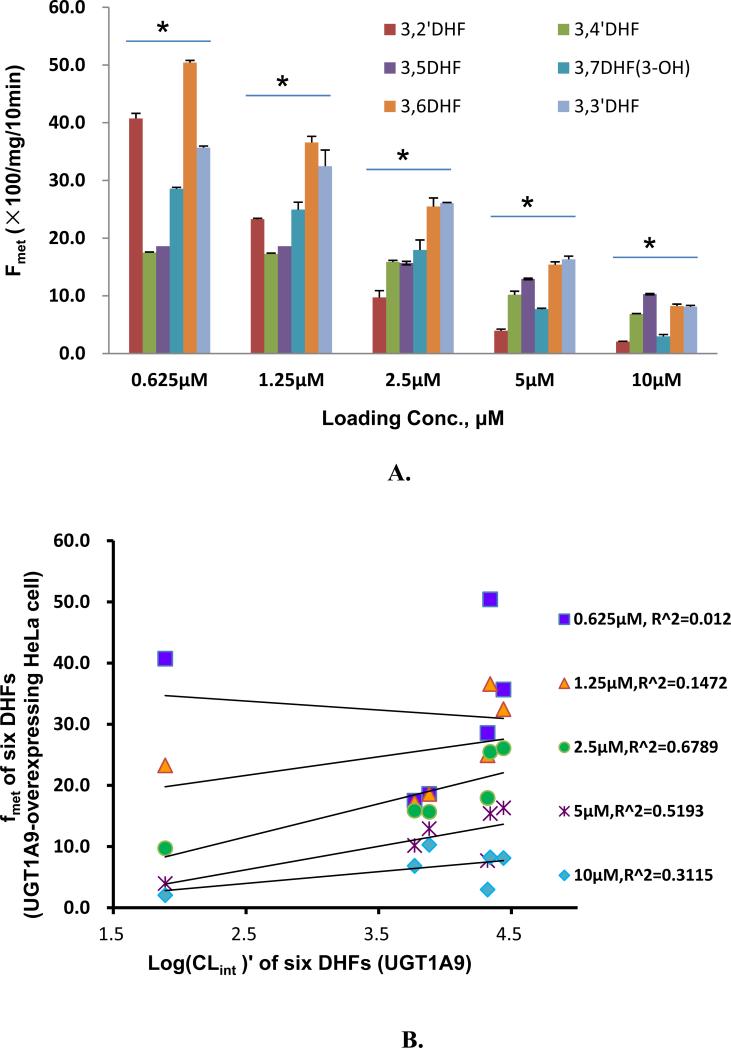

Lastly, we used fmet as a measurement of HeLa-1A9 cells’ ability to metabolize DHFs. As expected, fmet decreased with increasing concentration (Fig.8A). Substitution at 2’ and 7 position by a hydroxyl group did not increase fmet when comparing to 3HF. In fact, hydroxyl substation at these two positions led to the fastest decrease in fmet as a function of (rising) concentration. The fmet of 3,5-DHF was least sensitive to the rising concentration (Fig.8A). On the other hand, 3,6-DHF was the compound with the highest fmet value at all tested concentration, although it shared the top value with compounds such as 3,3’-DHF except at the lowest tested concentration (0.625 μM). In general, enzyme mediated CLint’ value correlated weakly or not at all with fmet of six DHFs, with the best r2 value of 0.679, suggesting that enzyme activities are usually not the rate-limiting step in the cellular production of glucuronides.

Fig. 8. Correlation between loading concentrations and metabolic efficiency or fmet derived from HeLa-UGT1A9 or CLint of UGT1A9.

Fig.8A plots fmet values for six DHFs at five loading concentrations to contrast the effects of structural changes on fmet values. Fig. 8B plots correlation between fmet values derived from UGT1A9-overexpressing HeLa cell and Log(CLint)′ derived from commercial UGT1A9 of six DHFs (3,2′-, 3,3′-, 3,4′-, 3,5-, 3,6- and 3,7DHF). Correlation coefficients were calculated for each of the tested concentrations. Each bar or point represents the average of three replicates, and error bars are the standard deviations of the mean (n=3). The symbol “*” means the difference between compounds within each concentration was statistically significant according to a one-way ANOVA test.

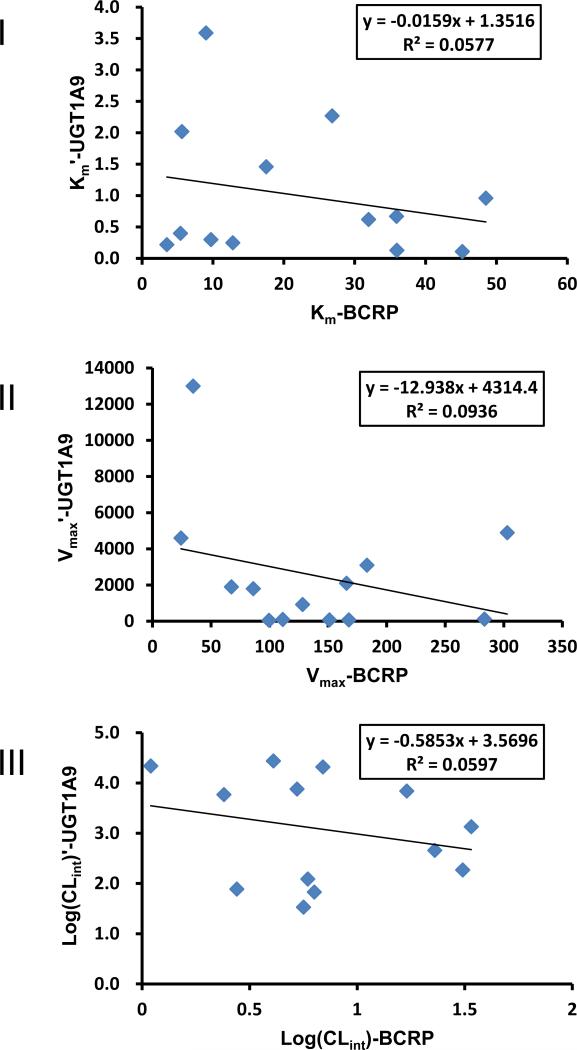

Correlation between UGT1A9-Mediated Glucuronidation and BCRP-mediated Glucuronide Efflux

It has been assumed routinely in medical literature that glucuronidation rates are primarily driven by activities of the enzyme(s) involved in the metabolism. Here, we plotted various kinetic parameters associated with flavonoid glucuronidation and glucuronide efflux. We plotted Km’ values of UGT1A9-mediated metabolism versus Km values of BCRP-mediated glucuronide efflux from HeLa-UGT1A9 cells and found no correlation (Fig.9A). We also plotted Vmax/Vmax’ values and CLint/CLint’ values, and found no correlation (Fig.9B, 9C). Therefore, UGT1A9 driven enzyme kinetic process did not dominate the cellular production of flavonoid glucuronide.

Fig. 9. Scatter plots of kinetic parameters derived from BCRP-mediated efflux (Km, Vmax and Log(CLint)) of HFs-G and DHFs-3-O-G and those derived from UGT1A9-mediated glucuronidation (Km′, Vmax′ and Log(CLint)′) of HFs and DHFs.

I, Km-BCRP vs. Km‘-UGT1A9; II, Vmax-BCRP vs. Vmax'-UGT1A9; III, Log(CLint)-BCRP vs. Log(CLint)'-UGT1A9.

Correlation between fmet and Rates of Metabolism or Efflux

An important question arising from the results above was: is there any relationship between fmet and rates of metabolism or efflux of a series of flavonoids. This is important because if there is a dominating process, then fmet is going to be more correlated with one of those rates. It is relatively straightforward to determining the relationship between fmet and UGT1A9 rates (Fig.4B), since we could compare the rates at the same concentration of flavonoids (this case the substrate). It is however much more difficult to do that for glucuronide efflux as the concentration of substrates (in this case various flavonoid glucuronides) are different inside the cells even though their extracellular concentrations were the same. For example, at 2.5 μM loading concentration, the intracellular concentrations of 7 different HF glucuronides differed by nearly 7 folds (Table 4). When intracellular concentrations of different HFs at the same loading concentration were plotted against corresponding efflux rates, there was no relationship, which was expected since different HF glucuronide had different affinity to the transporter. In other words, higher intracellular concentration did not necessarily lead to higher efflux rates.

Table 4.

The Intracellular concentration of HFs-G and DHFs-3-O-G at the end of the experiments for different compounds at different loading concentration of HFs and DHFs.

| Intracellular Con. of HFs-G or DHFs-3-O-G (μM) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loading HFs (μM) | 1.25 | 2.5 | 5 | 10 | 15 | 20 |

| 6HF-G | 12.46±0.36 | 24.80±2.19 | 57.82±6.22 | 89.13±21.41 | 72.68±4.19 | 111.43±15.84 |

| 5HF-G | 31.03±0.44 | 47.98±3.91 | 72.86±2.26 | 94.74±11.70 | 18.32±6.47 | 235.51±14.96 |

| 4′HF-G | 8.02±0.8 | 32.53±4.77 | 41.61±8.17 | 64.05±10.82 | 146.46±34.83 | 71.96±25.09 |

| 3HF-G | 7.14±3.02 | 38.56±8.36 | 206.98±12.39 | 335.57±41.55 | 356.82±94.04 | 280.60±28.78 |

| 3′HF-G | 4.17±1.05 | 1.58±2.42 | 41.68±6.14 | 79.75±7.60 | 56.74±4.90 | 85.65±9.88 |

| 2′HF-G | 4.63±0.43 | 29.58±3.75 | 150.96±24.87 | 152.62±12.47 | 58.09±11.61 | 92.74±11.26 |

| 7HF-G | 2.88±1.09 | 7.32±2.85 | 50.90±2.82 | 90.51±17.80 | 142.37±22.20 | 178.64±17.54 |

| Loading DHFs (μM) | 0.3125 | 0.625 | 1.25 | 2.5 | 5 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3,6DHF-3-O-G | 53.21±5.63 | 114.59±5.20 | 172.05±23.62 | 287.25±17.13 | 484.66±44.86 | 542.10±11.52 |

| 3,4′DHF-3-O-G | 2.67±0.09 | 14.27±2.00 | 71.15±6.11 | 241.60±26.10 | 645.32±5.81 | 715.62±31.7 |

| 3,2′DHF-3-O-G | 8.95±1.09 | 21.35±2.07 | 42.35±3.71 | 76.11±0.52 | 133.0±7.41 | 232.28±8.60 |

| 3,3′DHF-3-O-G | 3.65±0.09 | 15.36±0.42 | 96.59±7.30 | 175.30±16.06 | 338.58±15.67 | 345.71±27.23 |

| 3,5DHF-3-O-G | 2.28±0.68 | 4.82±0.02 | 14.70±2.60 | 53.48±3.45 | 242.98±9.46 | 416.65±12.34 |

| 3,7DHF-3-O-G | 0.9±0.04 | 1.93±0.24 | 4.51±0.62 | 11.04±1.19 | 40.53±1.51 | 7.55±0.49 |

To derive the efflux rates at the same intracellular concentration (50 μM), which was somewhat higher than the Km values of all the flavonoid glucuronides we studied, we used the kinetic parameters listed in Table 1 and Table 3. We then identified the extracellular concentration that was used to achieve the intracellular concentration of 50 μM (Table 4), and used the corresponding fmet value for plots. The calculated rates were then plotted against fmet. The results showed that there were very good correlation between calculated efflux rates (at an intracellular concentration of 50 μM) for 6 out of 7 HFs and 5 out of 6 DHFs (Fig.10AB). We did not do the same calculation for a lower concentration of glucuronides, because fmet estimated at the end of experiments were approximate values at best, as many substrates (especially HFs) were exhausted at the end of the experiments (2 hr time period). Lack of substrate would impact the amount of substrate available for metabolism, and therefore would decrease the fmet value.

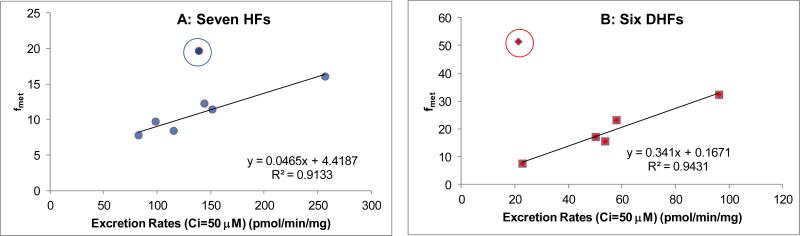

Fig. 10. Correlation between Rates of Glucuronide Efflux and fmet at Similar Intracellular Concentration of Glucuronides.

The rates of efflux at 50 μM were calculated for the plot because each glucuronide tested had an intracellular concentration (measured experimentally) that was close to an intracellular concentration of 50 μM. Once the concentration was selected, we were then able to find the fmet value for that compound for use in the plot. At this condition, none of the compound was exhausted. Different loading concentrations were used for different compounds and a table that details the actual concentrations of each flavonoid used is provided in the Supplemental Materials. The outlier compound (in circle) was 3HF in Fig.10A, or 3,6DHF in Fig.10B.

DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated clearly that cellular production of flavonoid glucuronides is not governed by the SAR derived using the predominating UGT isoform UGT1A9, which is highly expressed in HeLa-UGT1A9 cells. In other words, cellular production of many but not all flavonoid glucuronides is mainly governed by the function of the efflux transporter BCRP in HeLa-UGT1A9 cells. We demonstrated clearly that BCRP, acting as the gate-keeper (or “Revolving Door”) for glucuronides formed within the cell membrane, could both facilitate the efflux and control the intracellular concentration of glucuronides. In other words, glucuronides with lower efflux rates via BCRP than UGT1A9-mediated metabolism rates tend to accumulate inside the cells. Using fmet as the indicator of cellular glucuronide production, there was a weak correlation between cellular fmet and CLint’ of UGT1A9-mediated metabolism for seven HFs (mono-hydroxyflavones) (Fig. 4B) but very weak or no correlation for six DHFs (Fig. 8B). On the other hand, there were decent correlation between cellular fmet and rate of efflux values when intracellular concentration of were similar (Fig.10), although there were two notable outliers.

We first proposed that efflux transporter can act as a gate-keeper for the cellular glucuronide in 200524. We coined the term “Revolving Door” to explain the role of efflux transporter as the gate-keeper. We proposed that for many compounds, the lack of efficient or the presence of intrinsically inefficient “Revolving Door” would ultimately hinder the cellular production of glucuronides, especially flavonoid glucuronides, whose formation is rather rapid. Here, we provided convincing evidence to prove this hypothesis, albeit with a model system that is relatively simplistic compared to the majority of the metabolically active cells such as enterocytes, or hepatocytes. We showed that when a glucuronide is poor substrate of BCRP, faster metabolism of its aglycone (as measured by enzyme CLint’ values) by the rate-determining enzyme (i.e., UGT1A9) will not determine how efficient the cells are able to produce the glucuronides (fmet) (Fig.8B), a phenomenon that has been observed but not well explained. Rather, the cells began to accumulate high concentration of the glucuronides (Fig.3 and Fig.7), which did not appear to cause any harms to the cells. We also showed that SAR governing the glucuronidation could be completely different from SAR governing the glucuronide efflux (Fig.9). In addition, we showed that kinetic of glucuronidation often did not follow kinetics of glucuronide efflux (Fig.2, Fig.5 and Fig.6). Taken together, these results demonstrated that the two processes (i.e., glucuronidation vs. glucuronide efflux) are independent of each other. Because they were reasonably good correlation between efflux rates and fmet values, we believe that the efflux transporter BCRP acts as a “Revolving Door” to facilitate and/or control the cellular production of glucuronides. Although it is commonly assumed that faster metabolite formation should be correlated with faster glucuronide efflux, the “Revolving Door” nature of the cellular glucuronide production process meant that it was not true for many of the thirteen model flavonoids (Fig. 9).

BCRP is a very important apically located efflux transporter for removing intracellular glucuronides of flavonoid25, and recently we have shown that BCRP could control the distribution of genistein glucuronides in vivo26. Results shown here support this assertion because slower efflux via the BCRP meant significant accumulation (i.e., higher intracellular concentration than extracellular concentration) of glucuronides within the cells (Fig.3 and Fig.7), and in a polarized cell such as enterocyte or hepatocyte, the glucuronide would have been excreted by an alternative efflux transporter, most likely located on a different membrane (e.g., MRP3 on the basolateral membrane). This could then result in increased plasma exposure to these metabolites as we have shown previously using genistein26. Since glucuronides could be hydrolyzed back to aglycone via the action of glucuronidases26, the ability to change the systemic exposure of glucuronides meant that it is possible to change the systemic exposure to aglycone, which are usually pharmacologically more active.

BCRP is, however, not the only efflux transporter that has a major impact on the cellular excretion of glucuronides from enterocytes and hepatocytes. On the apical side, another important transporter is MRP2, whereas on the basolateral side the important transporter appears to be MRP3. In Caco-2 cells, inhibitors of MRPs significantly reduced the efflux of flavonoid glucuronides from apical and basolateral sides27,28. In MRP2-deficient rats, biliary excretion of phase II conjugates were severely impaired29-32, whereas intestinal excretion of glucuronides was only moderately decreased31. In contrast, in MRP3 deficient mice, plasma exposure to phase II conjugates could be drastically reduced33,34,31,35,36, whereas efflux via the apical efflux transporters could cause an increase in biliary excretion33,31. Taken together, these results suggest that efflux transporters may determine the organ/tissue distribution of hydrophilic glucuronides.

In the current paper, we used fmet as an indicator of cell's ability to metabolize a flavonoid. By definition, fmet is the fraction of compound metabolized at the end of an experiment. We have expressed the fmet value as “% /mg/10min” to account for differences in incubation time and amount of cells used, because fmet will change with the length of incubation, and amount of cells used in each experiment. This is necessary since we were unable to conduct all experiments for the same length of time (e.g., shorter time for flavonoids that are rapidly metabolized and longer time for slowly metabolized flavonoids). Some variability in cell culture was unavoidable, although the difference was usually within 25%. Finally, some fmet values may be underestimated due to substrate exhaustion. This occurred rather frequently when we used a low concentration of flavonoids (<1.25 μM) and long sampling time (2 hr). Therefore, we cannot compare the fmet values between 7 HFs and six DHFs as the experiments were conducted for different length of time. This difference explains why higher rates of efflux for glucuronides of DHF did not translate into higher fmet for DHFs when compared to HFs in Fig.10, although an additional variable of different extracellular concentrations (see Supplemental Materials) may have also played a significant role.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated clearly that efflux transporters may act as gate-keeper for the cellular production of glucuronides, and the functions of these efflux transporters are similar to the “Revolving Door” with a limited capacity. Because of the presence of these efflux transporters as the “Revolving Door,” compounds that are rapidly metabolized by an UGT isoform are not necessarily rapidly glucuronidated in an intact cell system, where the action of an efflux transporter may determine the rate and extent of a substrate's metabolism. Therefore, determination of a compound's susceptibility to glucuronidation must come from both its susceptibility to glucuronidation by one or a few UGT isoforms and resulting glucuronide's affinity to the relevant efflux transporters. In other words, separate SARs for glucuronide formation and efflux are needed for accurate prediction of cellular glucuronide production.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (GM070737) to M.H., and also supported in part by Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 30973978) and Jiangsu Government Scholarship for Overseas Studies (2010).

ABBREVIATIONS

- 2’HF

2'-hydroxyflavone

- 3’HF

3'-hydroxyflavone

- 4’HF

4'-hydroxyflavone

- 3HF

3-hydroxyflavone

- 5HF

5-hydroxyflavone

- 6HF

6-hydroxyflavone

- 7HF

7-hydroxyflavone

- 3,2’DHF

3,2'-dihydroxyflavone

- 3,3’DHF

3,3'-dihydroxyflavone

- 3,4’DHF

3,4'-dihydroxyflavone

- 3,5DHF

3,5-dihydroxyflavone

- 3,6DHF

3,6-dihydroxyflavone

- 3,7DHF

3,7-dihydroxyflavone

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- BCRP

breast cancer resistance protein

- CLint

Intrinsic Clearance

- O-G

O-glucuronide

- UPLC

ultra performance liquid chromatography

- UGT

UDP-glucuronosyltransferases

- UGPDA

uridine diphosphoglucuronic acid

- AIC

Akaike's information criterion

- WSS

Weighted Sum of Squared Residual

- SAR

structure activity relationship

- HBSS

Hank's balanced salt solution

- DMEM

Dulbecco's modified Eagles medium

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- MM

Michaelis-Menten equation

- BL

Biphasic linear portion model

- SI

Substrate inhibition equation

References

- 1.Fedejko B, Mazerska Z. [UDP-glucuronyltransferases in detoxification and activation metabolism of endogenous compounds and xenobiotics]. Postepy Biochem. 2011;57:49–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bock KW, Bock-Hennig BS. UDP-glucuronosyltransferases (UGTs): from purification of Ah-receptor-inducible UGT1A6 to coordinate regulation of subsets of CYPs, UGTs, and ABC transporters by nuclear receptors. Drug Metab. Rev. 2010;42:6–13. doi: 10.3109/03602530903205492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gregory PA, Lewinsky RH, Gardner-Stephen DA, Mackenzie PI. Regulation of UDP glucuronosyltransferases in the gastrointestinal tract. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2004;199:354–63. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guillemette C, Levesque E, Harvey M, Bellemare J, Menard V. UGT genomic diversity: beyond gene duplication. Drug Metab. Rev. 2010;42:24–44. doi: 10.3109/03602530903210682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laakkonen L, Finel M. A molecular model of the human UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1A1, its membrane orientation, and the interactions between different parts of the enzyme. Mol. Pharmacol. 2010;77:931–9. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.063289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Radominska-Pandya A, Bratton S, Little JM. A historical overview of the heterologous expression of mammalian UDP-glucuronosyltransferase isoforms over the past twenty years. Curr. Drug Metab. 2005;6:141–60. doi: 10.2174/1389200053586127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu B, Kulkarni K, Basu S, Zhang S, Hu M. First-pass metabolism via UDP-glucuronosyltransferase: a barrier to oral bioavailability of phenolics. J. Pharm. Sci. 2011;100:3655–81. doi: 10.1002/jps.22568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu B, Morrow JK, Singh R, Zhang S, Hu M. Three-dimensional quantitative structure-activity relationship studies on UGT1A9-mediated 3-O-glucuronidation of natural flavonols using a pharmacophore-based comparative molecular field analysis model. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2011;336:403–13. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.175356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tang L, Singh R, Liu Z, Hu M. Structure and concentration changes affect characterization of UGT isoform-specific metabolism of isoflavones. Mol. Pharm. 2009;6:1466–82. doi: 10.1021/mp8002557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tang L, Ye L, Singh R, Wu B, Lv C, Zhao J, Liu Z, Hu M. Use of glucuronidation fingerprinting to describe and predict mono- and dihydroxyflavone metabolism by recombinant UGT isoforms and human intestinal and liver microsomes. Mol. Pharm. 2010;7:664–79. doi: 10.1021/mp900223c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou Q, Zheng Z, Xia B, Tang L, Lv C, Liu W, Liu Z, Hu M. Use of isoform-specific UGT metabolism to determine and describe rates and profiles of glucuronidation of wogonin and oroxylin A by human liver and intestinal microsomes. Pharm. Res. 2010;27:1568–83. doi: 10.1007/s11095-010-0148-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ishii Y, Takeda S, Yamada H, Oguri K. Functional protein-protein interaction of drug metabolizing enzymes. Front. Biosci. 2005;10:887–95. doi: 10.2741/1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiang W, Xu B, Wu B, Yu R, Hu M. UDP-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) 1A9-overexpressing HeLa cells is an appropriate tool to delineate the kinetic interplay between breast cancer resistance protein (BRCP) and UGT and to rapidly identify the glucuronide substrates of BCRP. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2012;40:336–45. doi: 10.1124/dmd.111.041467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu X, Tam VH, Hu M. Disposition of flavonoids via enteric recycling: determination of the UDP-glucuronosyltransferase isoforms responsible for the metabolism of flavonoids in intact Caco-2 TC7 cells using siRNA. Mol. Pharm. 2007;4:873–82. doi: 10.1021/mp0601190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singh V, Parmar D, Singh MP. Do single nucleotide polymorphisms in xenobiotic metabolizing genes determine breast cancer susceptibility and treatment outcomes? Cancer Invest. 2008;26:769–83. doi: 10.1080/07357900801953196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu JW, Lin LC, Tsai TH. Drug-drug interactions of silymarin on the perspective of pharmacokinetics. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2009;121:185–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang J, Liao M, Shou M, Jamei M, Yeo KR, Tucker GT, Rostami-Hodjegan A. Cytochrome p450 turnover: regulation of synthesis and degradation, methods for determining rates, and implications for the prediction of drug interactions. Curr. Drug Metab. 2008;9:384–94. doi: 10.2174/138920008784746382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ginsberg G, Guyton K, Johns D, Schimek J, Angle K, Sonawane B. Genetic polymorphism in metabolism and host defense enzymes: implications for human health risk assessment. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2010;40:575–619. doi: 10.3109/10408441003742895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu W, Tang L, Ye L, Cai Z, Xia B, Zhang J, Hu M, Liu Z. Species and gender differences affect the metabolism of emodin via glucuronidation. AAPS J. 2010;12:424–36. doi: 10.1208/s12248-010-9200-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen J, Wang S, Jia X, Bajimaya S, Tam V, Hu M. Disposition of Flavonoids via Recycling: Comparison of Intestinal versus Hepatic Disposition. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2005;33:1777–84. doi: 10.1124/dmd.105.003673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hutzler JM, Tracy TS. Atypical kinetic profiles in drug metabolism reactions. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2002;30:355–62. doi: 10.1124/dmd.30.4.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang SW, Chen J, Jia X, Tam VH, Hu M. Disposition of flavonoids via enteric recycling: structural effects and lack of correlations between in vitro and in situ metabolic properties. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2006;34:1837–48. doi: 10.1124/dmd.106.009910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamaoka K, Nakagawa T, Uno T. Application of Akaike's information criterion (AIC) in the evaluation of linear pharmacokinetic equations. J. Pharmacokinet. Biopharm. 1978;6:165–75. doi: 10.1007/BF01117450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jeong EJ, Liu X, Jia X, Chen J, Hu M. Coupling of conjugating enzymes and efflux transporters: impact on bioavailability and drug interactions. Curr. Drug Metab. 2005;6:455–68. doi: 10.2174/138920005774330657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen H, Khemtong C, Yang X, Chang X, Gao J. Nanonization strategies for poorly water-soluble drugs. Drug Discov. Today. 2011;16:354–60. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2010.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang Z, Zhu W, Gao S, Yin T, Jiang W, Hu M. Breast Cancer Resistance Protein (ABCG2) Determines Distribution of Genistein Phase II Metabolites: Reevaluation of the Roles of ABCG2 in the Disposition of Genistein. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2012 doi: 10.1124/dmd.111.043901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen J, Lin H, Hu M. Absorption and metabolism of genistein and its five isoflavone analogs in the human intestinal Caco-2 model. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2005;55:159–69. doi: 10.1007/s00280-004-0842-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu M, Chen J, Lin H. Metabolism of flavonoids via enteric recycling: mechanistic studies of disposition of apigenin in the Caco-2 cell culture model. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2003;307:314–21. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.053496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dietrich CG, de Waart DR, Ottenhoff R, Bootsma AH, van Gennip AH, Elferink RP. Mrp2-deficiency in the rat impairs biliary and intestinal excretion and influences metabolism and disposition of the food-derived carcinogen 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo. Carcinogenesis. 2001;22:805–11. doi: 10.1093/carcin/22.5.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sakamoto S, Kusuhara H, Horie K, Takahashi K, Baba T, Ishizaki J, Sugiyama Y. Identification of the transporters involved in the hepatobiliary transport and intestinal efflux of methyl 1-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)-3-(3-ethylvaleryl)-4-hydroxy-6,7,8-trimethoxy-2-na phthoate (S-8921) glucuronide, a pharmacologically active metabolite of S-8921. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2008;36:1553–61. doi: 10.1124/dmd.108.020511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zamek-Gliszczynski MJ, Day JS, Hillgren KM, Phillips DL. Efflux transport is an important determinant of ethinylestradiol glucuronide and ethinylestradiol sulfate pharmacokinetics. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2011;39:1794–800. doi: 10.1124/dmd.111.040162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zamek-Gliszczynski MJ, Hoffmaster KA, Humphreys JE, Tian X, Nezasa KI, Brouwer KL. Differential involvement of Mrp2 (Abcc2) and Bcrp (Abcg2) in biliary excretion of 4-methylumbelliferyl glucuronide and sulfate in the rat. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2006;319:459–67. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.101840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kitamura Y, Kusuhara H, Sugiyama Y. Functional characterization of multidrug resistance-associated protein 3 (mrp3/abcc3) in the basolateral efflux of glucuronide conjugates in the mouse small intestine. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2010;332:659–66. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.156943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Manautou JE, de Waart DR, Kunne C, Zelcer N, Goedken M, Borst P, Elferink RO. Altered disposition of acetaminophen in mice with a disruption of the Mrp3 gene. Hepatology. 2005;42:1091–8. doi: 10.1002/hep.20898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zamek-Gliszczynski MJ, Nezasa K, Tian X, Bridges AS, Lee K, Belinsky MG, Kruh GD, Brouwer KL. Evaluation of the role of multidrug resistance-associated protein (Mrp) 3 and Mrp4 in hepatic basolateral excretion of sulfate and glucuronide metabolites of acetaminophen, 4-methylumbelliferone, and harmol in Abcc3−/− and Abcc4−/− mice. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2006;319:1485–91. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.110106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zelcer N, van de Wetering K, Hillebrand M, Sarton E, Kuil A, Wielinga PR, Tephly T, Dahan A, Beijnen JH, Borst P. Mice lacking multidrug resistance protein 3 show altered morphine pharmacokinetics and morphine-6-glucuronide antinociception. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:7274–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502530102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu B, Wang X, Zhang S, Hu M. Accurate Prediction of Glucuronidation of Structurally Diverse Phenolics by Human UGT1A9 Using Combined Experimental and In Silico Approaches. Pharm. Res. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s11095-012-0666-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.