Abstract

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is an aggressive type of breast cancer that does not express estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and human epidermal growth factor receptor (Her2/neu). TNBC has worse clinical outcomes than other breast cancer subtypes. However, the key molecules and mechanisms of TNBC migration remain unclear. In this study, we compared two normalized microarray datasets from GEO database between Asian (GSE33926) and non-Asian populations (GSE46581) to determine the molecules and common pathways in TNBC migration. We demonstrated that 16 genes in non-Asian samples and 9 genes in Asian samples are related to TNBC migration. In addition, our analytic results showed that 4 genes, PIK3R3, ITGB1, ITGAL, and ITGA6, were involved in the regulation of actin cytoskeleton. Our results indicated potential genes that link to TNBC migration. This study may help identify novel therapeutic targets for drug development in cancer therapy.

1. Introduction

Breast cancer is the second most common cancer worldwide with an estimated 1.38 million incident cases in 2008 [1]. Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is a highly aggressive type of breast cancer and refers to tumors that lack expressions of estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) genes [2]. In 2012, approximate 15%~20% of all breast cancer cases were diagnosed as TNBC [3], which had limited or ineffective treatment options. High risks of visceral metastasis [4], worse prognosis [5], and frequent relapses [6] make TNBC a major issue for global public health.

Dent et al. [7] showed that women with TNBC had an increased likelihood of distant recurrence within 5 years of diagnosis (hazard ratio: 2.6) compared to non-TNBC cases. Another study found that women with TNBC were more likely to experience a visceral metastasis within 5 years of diagnosis than other types of cancer (hazard ratio: 4.0) [8]. Moreover, several reports showed that TNBC has a shorter distant metastasis-free survival [9, 10] compared to hormone-sensitive or HER2-positive breast cancer. According to the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database the incidence rate, mortality rate, and five-year survival rate of TNBC are varied between different populations [11]. Previous study also showed that TNBC subtype was more frequent in African-Americans compared with Caucasians (adjusted odd ratio: 1.98) [12]. In addition, TNBC has the worst clinical pattern among all subtypes of breast cancer [13, 14]. Cell migration is a key factor in many events of cancer metastasis [15, 16]. In this study, we aimed to identify crucial molecules or common pathways which are involved in the metastasis of TNBC. Thus, the combination of two normalized microarray datasets from GEO database was used, with one dataset including microarray data from 41 non-Asian TNBC samples [17] and another dataset containing microarray data from 26 Taiwanese TNBC samples [18]. Differences in gene expressions between the early and late stages were calculated by Significance Analysis of Microarrays (SAM), and the pathway analysis was carried out using the Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA).

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Data Resources

The Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) is a public repository in which large numbers of high-throughput sequencing data and microarray datasets are stored. We used the keyword “triple negative breast cancer” to search for the material for our study from the GEO repository and found 683 qualified datasets. We then further filtered out datasets which were uploaded before 2012 and excluded in vitro studies and then obtained 353 datasets after the filtering process. Among the 353 datasets, both studies of Lindner et al. [17] and Kuo et al. [18] provided comprehensive information of patients' pathological stage of TNBC as well as sufficient sample sizes for our classification rule and matched our goal to search for common pathways on different races. These two datasets were deposited in the GEO database under the respective codes GSE46581 and GSE33926. Data of GSE46581 were generated by Illumina HumanRef-8 WG-DASL v3.0 (GPL8432), a Whole-Genome DASL Assay which simultaneously analyzes over 24,000 genes with high sensitivity [19]. Data of GSE33926 were generated from an Agilent-012097 Human 1A Microarray (V2) (GPL7264), a platform that contains over 20,000 oligonucleotide probes to detect gene expressions; this platform was reported to generate data with high confidence [20].

2.2. Data Processing

Lindner et al. (GSE46581) recruited 90 TNBC patients, profiled gene expressions and immunohistochemistry, and further investigated differences between European-American and African-American patients at a molecular level. Among the 90 samples, we selected 25 pathological stage I breast cancer patients as well as 16 patients at pathological stages III and IV and compared the total gene expression between these two groups. The project by Kuo et al. (GSE33926) recruited 51 TNBC Taiwanese patients and determined 45 signature genes for predicting TNBC metastasis. In the GSE33926 dataset, there were 12 pathological stage I patients and 14 patients at pathological stages III and IV. For both datasets, patients at pathological stage I without sign of cancer migration or metastasis found in regional lymph nodes and pathological stages III and IV patients with signs of migration or development of cancer cells in regional lymph nodes were classified as early-stage and late-stage groups, respectively, according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM system [21]. In addition, pathological stage II patients were excluded due to unclear lymph node involvement. For both datasets, we downloaded normalized data. Gene expressions of GSE33926 were normalized using quantile normalization as described in their article [18]. Both SAM and IPA were applied to identify the common pathways for TNBC.

2.3. Gene Expression Calculations

Gene expression profile calculations were conducted using SAM method [22] and R (vers. 2.15.1). For each dataset, we applied SAM to calculate and compare expression differences between early- and late-stage cohorts. Differentially expressed genes between early- and late-stage groups were identified using a 2-sided Student's t-test (P < 0.05) and comparisons of multiples of change (>2-fold). The percentage of these significant genes identified by chance was referred to the false discovery rate (FDR). SAM provided the q value as the score of FDR for each significant gene.

2.4. Pathway Analysis

The IPA (Ingenuity Systems, Mountain View, CA, USA; available at www.ingenuity.com) is a literature-based program for pathway analysis and gene function annotation. The gene network analysis is to cluster the genes based on their molecular functions and present their correlations. We applied the IPA to explore gene networks and mine the pathways which might be involved in cell migration and tumor metastasis of TNBC. We used the keyword “migration” to search the IPA database and selected networks related to cancer cell migration. For each dataset, the up- and down-regulated genes were mapped to the selected networks. We further compared the IPA mapping results between the two GEO datasets (GSE46581 and GSE33926) and determined the common molecules or pathways which had significant effects on TNBC cell migration.

2.5. DAVID Network Analysis

DAVID online database [23] provides a comprehensive set of functional annotation tools to visualize the pathways of our interested genes. After IPA analysis process, we selected 5 genes from GSE46581 and 2 genes from GSE33926 to further search for a common pathway of TNBC in DAVID database.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Characteristics and Gene Expressions

The criteria to determine pathological cancer stages include the tumor size, lymph nodes status, and metastasis status. Stages I and III/IV have clear definitions of cancer of whether it has reached nearby lymph nodes or not. However, the lymph node status is heterogenic in stage II. To avoid any ambiguity, we excluded patients who were classified as pathological cancer stage II. As shown in Tables 1 and 2, there was no significant difference in age between the two groups of the two datasets. The SAM program calculated gene expressions changes between pathological stage I and stages III/IV patients. In the American dataset (GSE46581), 18,345 out of 24,000 target genes were analyzed, and 433 upregulated genes and 241 downregulated genes were found to reach statistical significance. In the Taiwanese dataset (GSE33926), 20,140 genes were analyzed, and 48 upregulated genes and 77 downregulated genes were observed to have statistically significant difference between early- and late-stage groups.

Table 1.

Demographic data of patients in the GSE46581 dataset (non-Asian).

|

Patients in the early stage (N = 25) |

Patients in the late stage (N = 16) |

P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Age (years) | |||||

| ≤39 | 3 | 12.00 | 4 | 25.00 | |

| 40~49 | 6 | 24.00 | 6 | 37.50 | |

| ≥50 | 16 | 64.00 | 5 | 31.25 | 0.1451 |

| Missing value |

0 | 1 | 6.25 | ||

| Lymph nodes | |||||

| Negative | 16 | 64.00 | 4 | 25.00 | |

| Positive | 2 | 8.00 | 7 | 43.75 | <0.05* |

| Not applicable |

7 | 28.00 | 5 | 31.25 | |

*The statistical significance (*P < 0.05) of the difference between early-stage and late-stage patients was determined by Chi-square test.

Table 2.

Demographic data of patients in the GSE33926 dataset (Asian).

|

Patients in the early stage (N = 12) |

Patients in the late stage (N = 14) |

P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Age (years) | |||||

| ≤39 | 1 | 8.33 | 1 | 7.14 | |

| 40~49 | 2 | 16.67 | 4 | 28.57 | |

| ≥50 | 9 | 75.00 | 9 | 64.29 | 0.8555 |

| Lymph nodes | |||||

| Negative | 12 | 100 | 1 | 7.14 | |

| Positive | 0 | 0 | 13 | 92.85 | <0.05* |

*The statistical significance (*P < 0.05) of the difference between early-stage and late-stage patients was determined by Chi-square test.

3.2. Common Genes between Asians and Non-Asians

After the gene expression calculation process, we found 5 genes with significant expression changes that commonly existed in both Asian and non-Asian samples. Among the 5 genes, ACTA1, C4orf7, CYP26B1, and PRAME were downregulated in both Asian and non-Asian TNBC populations, while ASPN was the only gene that was upregulated in both populations (Table 3).

Table 3.

Common genes between Asian and non-Asian populations.

| Gene symbol | Gene description |

|---|---|

| Up-regulated gene | |

| ASPN | Asporin |

|

| |

| Down-regulated genes | |

| ACTA1 | Actin, alpha 1, skeletal muscle |

| C4orf7 | Follicular dendritic cell secreted protein |

| CYP26B1 | CytochromeP450, family26, subfamilyB, polypeptide1 |

| PRAME | Preferentially expressed antigen in melanoma |

3.3. Pathway Analysis of TNBC from Non-Asian and Asian Patients

IPA was applied to annotate the cell migration-related genes and the networks. Patients' ethnic origins in the GSE46581 dataset were European and African-American. In the non-Asian samples (GSE46581), there were 16 genes with significant expression changes related to cell migration, whereas 9 cell migration-related genes were found in the Asian samples (GSE33926) (Table 4). However, no common cell migration-related gene was identified in both these two populations.

Table 4.

25 migration related genes in Asian and non-Asian populations.

| Gene symbol | Multiples of change | Gene description | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Up-regulated genes | |||

| GSE46581 | ITGB1 | 2.101 | Integrin, beta 1 |

| RGS1 | 2.231 | Regulator of G-protein signaling 1 | |

| AKT3 | 2.371 | v-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog 3 | |

| ETV4 | 2.103 | Ets variant 4 | |

| HTATIP2 | 2.059 | HIV-1 Tat interactive protein 2, 30 kDa | |

| IGF1 | 2.231 | Insulin-like growth factor 1 | |

| ITGA6 | 2.295 | Integrin, alpha 6 | |

| LEP | 2.064 | Leptin | |

| SEMA4D | 2.056 | Sema domain, immunoglobulin (Ig domain), transmembrane domain and short cytoplasmic domain, (1emaphoring) 4D | |

|

| |||

| GSE33926 | PIK3R3 | 2.006 | Phosphoinositide-3-kinase, regulatory subunit 3 (gamma) |

| AR | 2.106 | Androgen receptor | |

| CLGN | 2.004 | Calmegin | |

| TFPI | 2.101 | Tissue factor pathway inhibitor | |

|

| |||

| Down-regulated genes | |||

| GSE46581 | CCL21 | 0.433 | Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 21 |

| CCL3 | 0.389 | Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 3 | |

| CAMP | 0.464 | Cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide | |

| CD226 | 0.477 | CD226 molecule | |

| ITGAL | 0.478 | Integrin, alpha L (antigen CD11A (p180), lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1; alpha polypeptide) | |

| ITGAX | 0.448 | Integrin, alpha X | |

| TNFRSF | 0.368 | Receptor- (TNFRSF-) interacting serine-threonine kinase 1 | |

|

| |||

| GSE33926 | MIA | 0.248 | Melanoma inhibitory activity |

| CDKN2A | 0.386 | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A | |

| EN1 | 0.460 | Engrailed homeobox 1 | |

| PITX2 | 0.476 | Paired-like homeodomain 2 | |

| CCR7 | 0.419 | Chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 7 | |

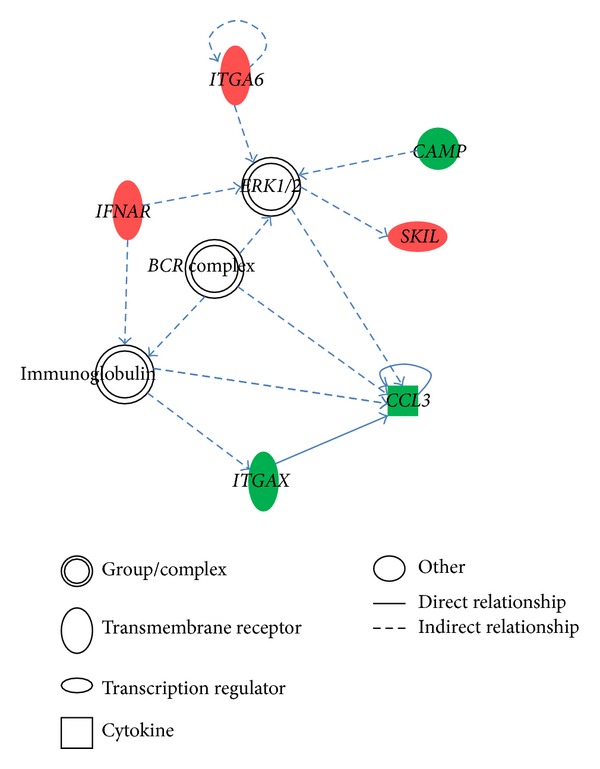

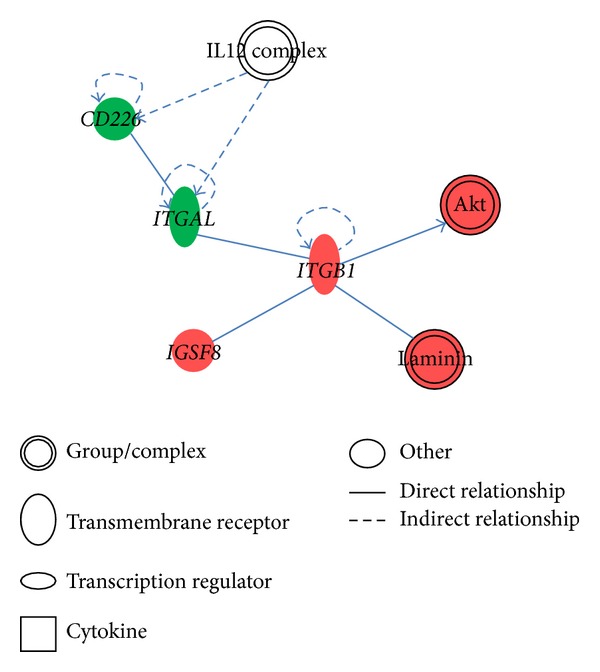

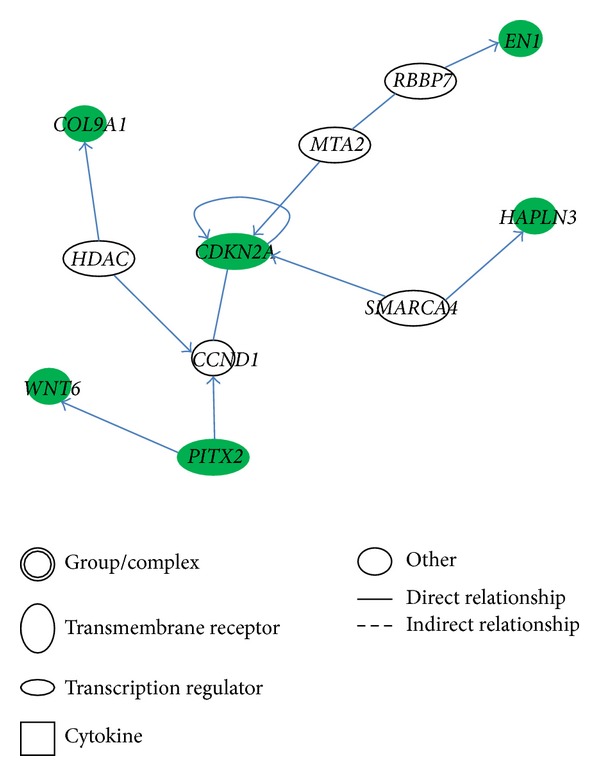

We further explored molecular networks of these cell migration-related genes to cluster gene functions. Among the 16 genes found in non-Asian samples, 7 genes were mapped to three different molecular networks (Table 5). ITGA6, CCL3, and ITGAX were found to be associated with cell death and survival (Figure 1), while ITGB1, ITGAL, and CD226 were mapped to the cellular movement, cancer, and tissue development modules (Figure 2). In the Asian samples, 8 out of 9 genes were mapped to 4 different gene networks. Among the 8 genes, CDKN2A, EN1, and PITX2 were associated with the cell cycle (Figure 3), and the remaining genes were related to organ morphology and cellular development.

Table 5.

Migration related gene network in Asian and non-Asian populations.

| Network | Genes | |

|---|---|---|

| GSE46581 | Inflammatory response, cell signaling, cellular movement | CCL21 |

| Cell death and survival, developmental disorders, skeletal and muscular disorders | ITGA6, CCL3, ITGAX | |

| Cellular movement, cancer, tissue development | ITGB1, ITGAL, CD226 | |

|

| ||

| GSE33926 | Dermatological diseases and conditions, cellular development, cellular growth and proliferation | MIA, PIK3R3 |

| Organ morphology, reproductive system development and function, developmental disorders | AR, CCR7 | |

| Cell cycle, DNA replication, recombination, and repair, cellular assembly and organization | CDKN2A, EN1, PITX2 | |

| Cellular development, cellular growth and proliferation, tumor morphology | TFPI | |

Figure 1.

Cell death and survival, developmental disorders, skeletal and muscular disorders network.

Figure 2.

Cellular movement, cancer, tissue development network.

Figure 3.

Cell cycle, DNA replication, recombination, and repair, cellular assembly and organization network.

In non-Asian samples, CCL3, ITGAX, ITGA6, ITGB1, ITGAL, CCL21, and CD226 were used to mine the pathway. The top three pathways we observed were paxillin signaling, granulocyte adhesion and diapedesis, and integrin signaling. Among the 7 genes we used, ITGB1, ITGA6, and ITGAL all belonged to the above three pathways. For Asian samples, MIA, PIK3R3, AR, CCR7, CDKN2A, EN1, PITX2, and TFPI were applied to the pathway analysis process. The top three pathways we observed were chronic myeloid leukemia signaling, p53 signaling, and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) signaling, and CDKN2A and PIK3R3 were common molecules involved in these three pathways (Table 6).

Table 6.

Migration related canonical pathway in Asian and non-Asian populations.

3.4. DAVID Database for Mining Common Pathways

During the IPA pathway analysis process, we found that the top three pathways of non-Asian populations differed from those of Asian populations. However, in non-Asian dataset, CCL3, ITGA6, ITGAL, ITGAX, and ITGB1 were commonly involved in the pathways, paxillin signaling, granulocyte adhesion and diapedesis, and integrin signaling, while CDKN2A and PIK3R3 were common molecules involved in the top three pathways which were observed in Asian dataset. Hence, we applied the DAVID online pathway analysis tool to discover if there were common pathways in which these genes were involved. We found that PIK3R3, ITGB1, ITGA6, and ITGAL were all involved in actin cytoskeleton pathway. Although they were located in different routes of the same pathway, PIK3R3, ITGB1, ITGA6, and ITGAL indirectly interacted with the common downstream gene, Rac (see Supplement S1 in Supplementary Material available online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/536591).

4. Discussion

The primary goal of this study was to discover common molecules or pathways that affected TNBC cell migration in different ethnic groups. We observed that regulation of the actin cytoskeleton could be one of the most important pathways to affect TNBC cell migration.

Through the SAM calculation process, ACTA1, ASPN, C4orf7, CYP26B1, and PRAME showed statistically significant differences in expressions between early and late stages of cancer in both Asian and non-Asian samples. Our results showed that ASPN was upregulated and annotated in cancer function. This result was consistent with a previous study by Castellana et al. [24]. Their study reported that ASPN is highly upregulated in invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC), possibly associated with invasion, and related to the epithelial-mesenchymal transition. In addition, PRAME and CYP26B1 were found to be related to the retinoic acid signaling pathway [25, 26]. PRAME was reported to be involved in tumor progression rather than tumor initiation by suppressing retinoic acid signaling which regulates gene expression in melanomas [25]. However, these genes were not related to cell migration in our IPA analysis.

We found 16 migration-related genes in the non-Asian populations and 9 migration-related genes in the Taiwanese dataset. ITGB1 and ITGA6 were strongly correlated with cell migration and cell growth. Indeed, Ivanova et al. proposed that the upregulated ITGA6 promotes breast cancer metastasis [27]. Barkan and Chambers also showed that ITGB1 is a key regulator in the switch from dormancy to active proliferation of tumor cells [28]. ITGB1 and ITGA6 are genes belonging to ITG family which is a receptor on cell membrane. Previous study has indicated that tellurium compound binds with thiols of cysteine residues within the integrin, resulting in antimetastatic activities in melanoma [29]. Thus, this compound may have potential effects on the inhibition of TNBC cell migration.

We found three pathways in non-Asian samples which might play important roles in TNBC cell migration: paxillin signaling, granulocyte adhesion and diapedesis, and integrin signaling. Paxillin is a focal adhesion-associated protein which has been found to be involved in cell migration [30], while integrin was identified to be involved in cell migration, invasion, intravasation, and extravasation, and platelet interactions [31]. Thus, we speculated that TNBC cell migration requires cell-cell and cell-extracellular adhesive forces. In addition, the gene network analysis showed that the immunoglobulin and cytokine IL12 participated in the top three gene networks (Figures 1 and 2). Therefore, immune system may also participate in TNBC migration. In the Asian dataset, the CDKN2A gene with the highest degree of connectivity showed the importance of this molecular in the cell cycle, DNA replication, and recombination network. In addition, a previous study showed that a germline mutation of CDKN2A increases the risk of breast cancer [32]. Chronic myeloid leukemia signaling, p53 signaling, and HGF signaling were ranked as the top three pathways. Previous studies demonstrated that higher HGF levels were found in patients with invasive breast cancer compared to controls [33, 34].

By applying the DAVID online analysis tool, we found that PIK3R3, ITGB1, ITGAL, and ITGA6 participated in regulating the actin cytoskeleton (Supplement S1) which supports our hypothesis that a common pathway is involved in TNBC cell migration. Also, these genes had a common downstream gene, Rac, which might be a potential target molecule for developing novel treatments for TNBC. However, there are racial differences existing in the cell migration mechanisms. The cell migration mechanism of non-Asian samples was through transmembrane receptor integrin or cell adhesion molecule such as paxillin, while in Asian samples the mechanism of cell migration majorly involved chemotactic and growth factor. These two points may be useful for further study and optimal treatment in the future.

In this study, we used PubMed database and IPA upstream regulator analysis to identify target gene's upstream regulators and observed some miRNAs being potential to regulate the gene expression. For the upstream regulator analysis, Fisher's exact test was applied to calculate the P value and z-score of expected causal effects between upstream regulators and target genes; the expected causal effects are derived from the literature compiled in the Ingenuity Knowledge Base [35]. We observed that miR-7 is a regulator of PIK3R3 (Supplement S2), and Xu et al. [36] also indicated that miR-7 seed region matches to the sequence of PIK3R3 3′ UTR;thus PIK3R3 is believed to be a novel target of miR-7. Kong et al. [37] also proposed that miR-7 can inhibit metastasis of breast cancer cells. Additionally, ITGB1 was predicted to be inhibited by miR-8 (Supplement 2), which has homology to Human-miR-200 family miRNAs [38]. Up to date, there is no record showing that miR-8 expresses in human body. Thus, we suspect that IPA has some defects existing in the database. Nevertheless, because miR-200b and miR-200c are homologous with miR-8, it could be speculated that miR-200b and miR-200c might be the regulators of ITGB1. To sum up, miRNA is an important regulator that inhibits target genes and therefore controls the cell migration ability. The computational analysis provides an efficient way to screen through huge amounts of molecular for selection of candidate regulators. However, the results of computational analysis still require further biological studies for validations.

The poor tumor prognosis is the consequence of cancer cell proliferation and migration [39]. However, Kuo et al. (GSE33926) focused on discussing cell proliferation, while we emphasized on studying the tumor cell migration. The combination of these two results may promote the accuracy of TNBC prognosis.

There are limitations in our study. First, data collection was from small sample size. Second, two datasets were generated from different microarray platforms; thus, the number of genes and the sensitivity of platforms might be varied. Further study in a large scale sample size is needed.

In summary, ITGA6, ITGAL, ITGB1, and PIK3R3 were found as important regulators in actin cytoskeleton pathway. Thus, actin cytoskeleton pathways should play important roles in TNBC cell migration. Moreover, ITGA6, ITGAL, ITGB1, ITGAX, CCL3, PIK3R3, and CDKN2A were found to be important for TNBC cell migration. The associations between these 7 genes and TNBC patients' clinical outcomes require further investigation.

Supplementary Material

Supplement 1. KEGG pathway analysis indicated that PIK3R3, ITGB1, ITGA6, and ITGAL were involved in actin cytoskeleton pathway.

Supplement 2. miR upstream regulators were identified by IPA analysis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grants from the Department of Health (Grant no. DOH102-TD-C-111-002) and National Science Council (Grant nos. NSC101-2628-B-038-001-MY2, NSC101-2320-B-038-029-MY3).

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Shin H-R, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. International Journal of Cancer. 2010;127(12):2893–2917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carey L, Winer E, Viale G, Cameron D, Gianni L. Triple-negative breast cancer: disease entity or title of convenience? Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology. 2010;7(12):683–692. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2010.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brouckaert O, Wildiers H, Floris G, Neven P. Update on triple-negative breast cancer: prognosis and management strategies. International Journal of Women's Health. 2012;4:511–520. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S18541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heitz F, Harter P, Traut A, Lueck HJ, Beutel B, du Bois A. Cerebral metastases (CM) in breast cancer (BC) with focus on triple-negative tumors. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26(15, supplement) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nielsen TO, Hsu FD, Jensen K, et al. Immunohistochemical and clinical characterization of the basal-like subtype of invasive breast carcinoma. Clinical Cancer Research. 2004;10(16):5367–5374. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tseng LM, Hsu NC, Chen SC, et al. Distant metastasis in triple-negative breast cancer. Neoplasma. 2013;60(3):290–294. doi: 10.4149/neo_2013_038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dent R, Trudeau M, Pritchard KI, et al. Triple-negative breast cancer: clinical features and patterns of recurrence. Clinical Cancer Research. 2007;13(15, part 1):4429–4434. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-3045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dent R, Hanna WM, Trudeau M, Rawlinson E, Sun P, Narod SA. Pattern of metastatic spread in triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2009;115(2):423–428. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0086-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haffty BG, Yang Q, Reiss M, et al. Locoregional relapse and distant metastasis in conservatively managed triple negative early-stage breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24(36):5652–5657. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.5664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kennecke H, Yerushalmi R, Woods R, et al. Metastatic behavior of breast cancer subtypes. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28(20):3271–3277. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.9820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morris GJ, Naidu S, Topham AK, et al. Differences in breast carcinoma characteristics in newly diagnosed African-American and Caucasian patients: a single-institution compilation compared with the national cancer institute’s surveillance, epidemiology, and end results database. Cancer. 2007;110(4):876–884. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin NU, Vanderplas A, Hughes ME, et al. Clinicopathologic features, patterns of recurrence, and survival among women with triple-negative breast cancer in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Cancer. 2012;118(22):5463–5472. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yao-Lung K, Dar-Ren C, Tsai-Wang C. Clinicopathological features of triple-negative breast cancer in Taiwanese women. International Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2011;16(5):500–505. doi: 10.1007/s10147-011-0211-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li CY, Zhang S, Zhang XB, Wang P, Hou GF, Zhang J. Clinicopathological and prognostic characteristics of triple- negative breast cancer (TNBC) in Chinese patients: a retrospective study. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention. 2013;14(6):3779–3784. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2013.14.6.3779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zygourakis K. Quantification and regulation of cell migration. Tissue Engineering. 1996;2(1):1–16. doi: 10.1089/ten.1996.2.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jouanneau J, Bellusci S, Moens G, Thiery JP. Molecular aspects of invasiveness and metastasis. Pathologie Biologie. 1995;43(3):181–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lindner R, Sullivan C, Offor O, et al. Molecular phenotypes in triple negative breast cancer from African American patients suggest targets for therapy. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071915.e71915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuo WH, Chang YY, Lai LC, et al. Molecular characteristics and metastasis predictor genes of triple-negative breast cancer: a clinical study of triple-negative breast carcinomas. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045831.e45831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whole-genome DASL HT assay for expression profiling in ffpe samples. http://res.illumina.com/documents/products/datasheets/datasheet_whole_genome_dasl.pdf.

- 20.Agilent whole human genome oligo microarray kit. http://www.chem.agilent.com/library/brochures/5989_0654en_wghuman_7_04_web.pdf.

- 21.American Joint Commitee on Cancer. https://cancerstaging.org.

- 22.Tusher VG, Tibshirani R, Chu G. Significance analysis of microarrays applied to the ionizing radiation response. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98(9):5116–5121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091062498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang DW, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nature Protocols. 2009;4(1):44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Castellana B, Escuin D, Peiro G, et al. ASPN and GJB2 are implicated in the mechanisms of invasion of ductal breast carcinomas. Journal of Cancer. 2012;3:175–183. doi: 10.7150/jca.4120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Epping MT, Wang L, Edel MJ, Carlée L, Hernandez M, Bernards R. The human tumor antigen PRAME is a dominant repressor of retinoic acid receptor signaling. Cell. 2005;122(6):835–847. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodriguez-Mari A, Canestro C, BreMiller RA, Catchen JM, Yan YL, Postlethwait JH. Retinoic acid metabolic genes, meiosis, and gonadal sex differentiation in zebrafish. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073951.e73951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ivanova IA, Vermeulen JF, Ercan C, et al. FER kinase promotes breast cancer metastasis by regulating alpha6- and beta1-integrin-dependent cell adhesion and anoikis resistance. Oncogene. 2013;32(50):5582–5592. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barkan D, Chambers AF. β1-integrin: a potential therapeutic target in the battle against cancer recurrence. Clinical Cancer Research. 2011;17(23):7219–7223. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sredni B. Immunomodulating tellurium compounds as anti-cancer agents. Seminars in Cancer Biology. 2012;22(1):60–69. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2011.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Velasco-Velázquez MA, Salinas-Jazmín N, Mendoza-Patiño N, Mandoki JJ. Reduced paxillin expression contributes to the antimetastatic effect of 4-hydroxycoumarin on B16-F10 melanoma cells. Cancer Cell International. 2008;8, article 8 doi: 10.1186/1475-2867-8-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mizejewski GJ. Role of integrins in cancer: survey of expression patterns. Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine. 1999;222(2):124–138. doi: 10.1177/153537029922200203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nagore E, Montoro A, García-Casado Z, et al. Germline mutations in CDKN2A are infrequent in female patients with melanoma and breast cancer. Melanoma Research. 2009;19(4):211–214. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0b013e3283281057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.El-Attar HA, Sheta MI. Hepatocyte growth factor profile with breast cancer. Indian Journal of Pathology and Microbiology. 2011;54(3):509–513. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.85083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sheen-Chen S-M, Liu Y-W, Eng H-L, Chou F-F. Serum levels of hepatocyte growth factor in patients with breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers and Prevention. 2005;14(3):715–717. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kramer A, Green J, Pollard J, Jr., Tugendreich S. Causal analysis approaches in ingenuity pathway analysis. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:523–530. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu L, Wen Z, Zhou Y, et al. MicroRNA-7-regulated TLR9 signaling-enhanced growth and metastatic potential of human lung cancer cells by altering the phosphoinositide-3-kinase, regulatory subunit 3/Akt pathway. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2013;24(1):42–55. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E12-07-0519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kong X, Li G, Yuan Y, et al. MicroRNA-7 inhibits epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and metastasis of breast cancer cells via targeting FAK expression. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041523.e41523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hyun S, Lee JH, Jin H, et al. Conserved MicroRNA miR-8/miR-200 and its target USH/FOG2 control growth by regulating PI3K. Cell. 2009;139(6):1096–1108. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ausprunk DH, Folkman J. Migration and proliferation of endothelial cells in preformed and newly formed blood vessels during tumor angiogenesis. Microvascular Research. 1977;14(1):53–65. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(77)90141-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplement 1. KEGG pathway analysis indicated that PIK3R3, ITGB1, ITGA6, and ITGAL were involved in actin cytoskeleton pathway.

Supplement 2. miR upstream regulators were identified by IPA analysis.