Abstract

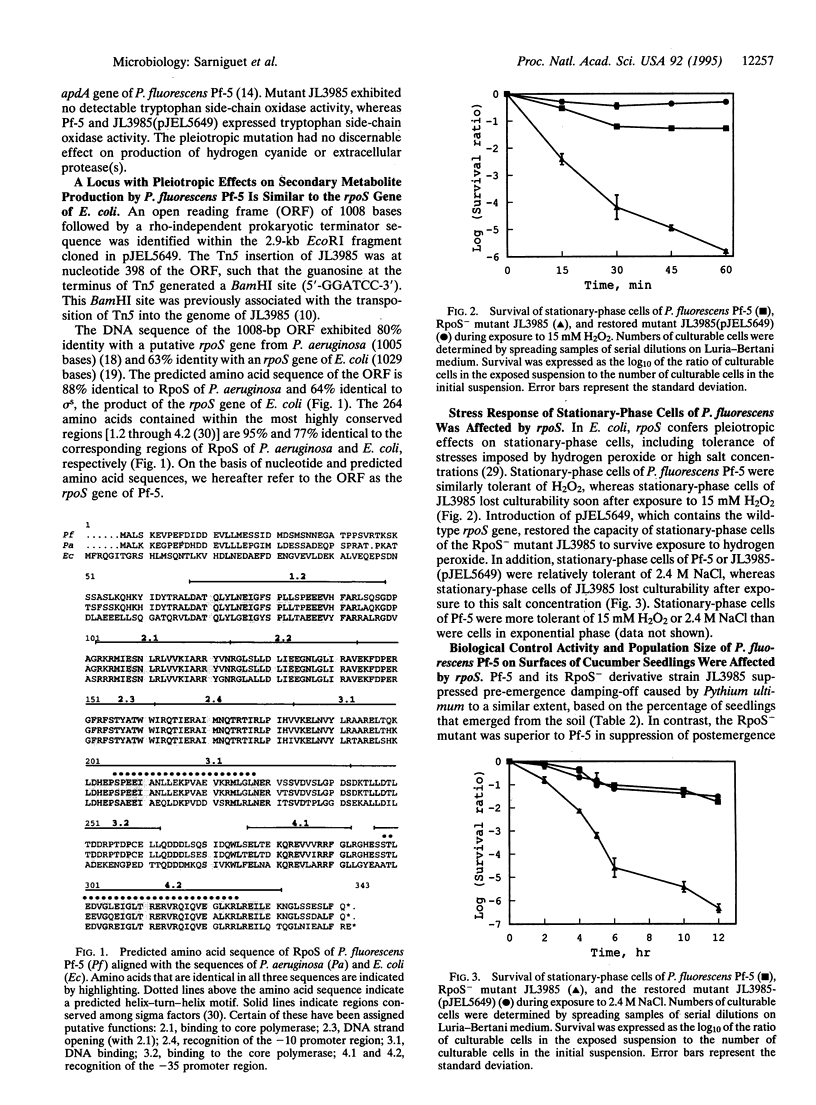

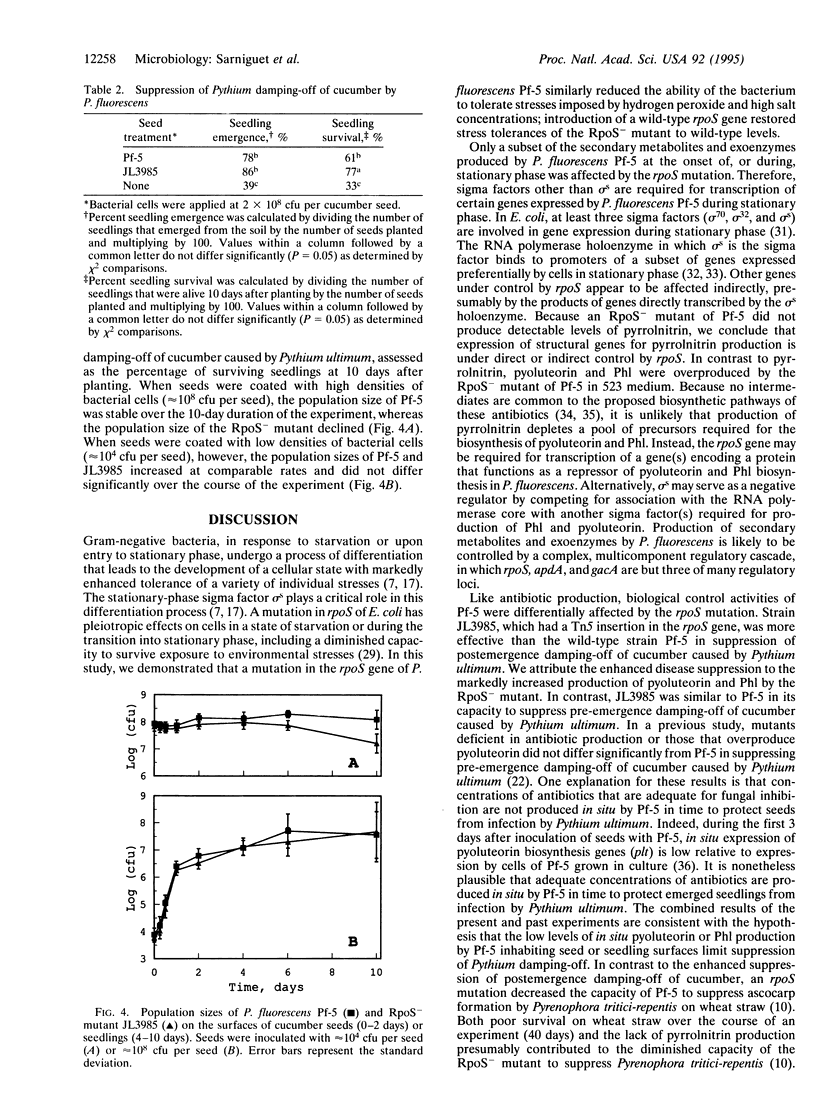

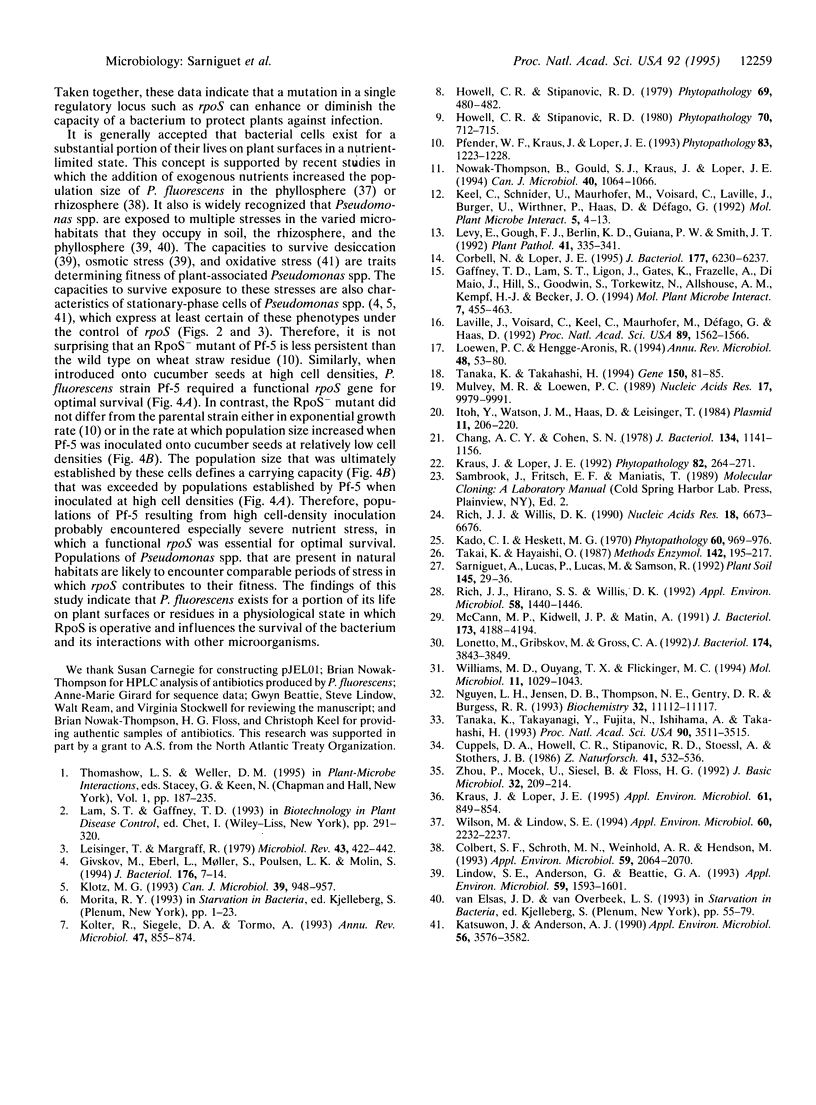

Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5, a rhizosphere-inhabiting bacterium that suppresses several soilborne pathogens of plants, produces the antibiotics pyrrolnitrin, pyoluteorin, and 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol. A gene necessary for pyrrolnitrin production by Pf-5 was identified as rpoS, which encodes the stationary-phase sigma factor sigma s. Several pleiotropic effects of an rpoS mutation in Escherichia coli also were observed in an RpoS- mutant of Pf-5. These included sensitivities of stationary-phase cells to stresses imposed by hydrogen peroxide or high salt concentration. A plasmid containing the cloned wild-type rpoS gene restored pyrrolnitrin production and stress tolerance to the RpoS- mutant of Pf-5. The RpoS- mutant overproduced pyoluteorin and 2,4-diacetyl-phloroglucinol, two antibiotics that inhibit growth of the phytopathogenic fungus Pythium ultimum, and was superior to the wild type in suppression of seedling damping-off of cucumber caused by Pythium ultimum. When inoculated onto cucumber seed at high cell densities, the RpoS- mutant did not survive as well as the wild-type strain on surfaces of developing seedlings. Other stationary-phase-specific phenotypes of Pf-5, such as the production of cyanide and extracellular protease(s) were expressed by the RpoS- mutant, suggesting that sigma s is only one of the sigma factors required for the transcription of genes in stationary-phase cells of P. fluorescens. These results indicate that a sigma factor encoded by rpoS influences antibiotic production, biological control activity, and survival of P. fluorescens on plant surfaces.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Chang A. C., Cohen S. N. Construction and characterization of amplifiable multicopy DNA cloning vehicles derived from the P15A cryptic miniplasmid. J Bacteriol. 1978 Jun;134(3):1141–1156. doi: 10.1128/jb.134.3.1141-1156.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colbert S. F., Schroth M. N., Weinhold A. R., Hendson M. Enhancement of Population Densities of Pseudomonas putida PpG7 in Agricultural Ecosystems by Selective Feeding with the Carbon Source Salicylate. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993 Jul;59(7):2064–2070. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.7.2064-2070.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbell N., Loper J. E. A global regulator of secondary metabolite production in Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5. J Bacteriol. 1995 Nov;177(21):6230–6236. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.21.6230-6236.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaffney T. D., Lam S. T., Ligon J., Gates K., Frazelle A., Di Maio J., Hill S., Goodwin S., Torkewitz N., Allshouse A. M. Global regulation of expression of antifungal factors by a Pseudomonas fluorescens biological control strain. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 1994 Jul-Aug;7(4):455–463. doi: 10.1094/mpmi-7-0455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Givskov M., Eberl L., Møller S., Poulsen L. K., Molin S. Responses to nutrient starvation in Pseudomonas putida KT2442: analysis of general cross-protection, cell shape, and macromolecular content. J Bacteriol. 1994 Jan;176(1):7–14. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.1.7-14.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh Y., Watson J. M., Haas D., Leisinger T. Genetic and molecular characterization of the Pseudomonas plasmid pVS1. Plasmid. 1984 May;11(3):206–220. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(84)90027-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kado C. I., Heskett M. G. Selective media for isolation of Agrobacterium, Corynebacterium, Erwinia, Pseudomonas, and Xanthomonas. Phytopathology. 1970 Jun;60(6):969–976. doi: 10.1094/phyto-60-969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsuwon J., Anderson A. J. Catalase and superoxide dismutase of root-colonizing saprophytic fluorescent pseudomonads. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990 Nov;56(11):3576–3582. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.11.3576-3582.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolter R., Siegele D. A., Tormo A. The stationary phase of the bacterial life cycle. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1993;47:855–874. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.47.100193.004231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus J., Loper J. E. Characterization of a Genomic Region Required for Production of the Antibiotic Pyoluteorin by the Biological Control Agent Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995 Mar;61(3):849–854. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.3.849-854.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laville J., Voisard C., Keel C., Maurhofer M., Défago G., Haas D. Global control in Pseudomonas fluorescens mediating antibiotic synthesis and suppression of black root rot of tobacco. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992 Mar 1;89(5):1562–1566. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.5.1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leisinger T., Margraff R. Secondary metabolites of the fluorescent pseudomonads. Microbiol Rev. 1979 Sep;43(3):422–442. doi: 10.1128/mr.43.3.422-442.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy D. M., Rowley D. A., Abraham R. R. Portable infrared pupillometry using Pupilscan: relation to somatic and autonomic nerve function in diabetes mellitus. Clin Auton Res. 1992 Oct;2(5):335–341. doi: 10.1007/BF01824304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindow S. E., Andersen G., Beattie G. A. Characteristics of Insertional Mutants of Pseudomonas syringae with Reduced Epiphytic Fitness. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993 May;59(5):1593–1601. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.5.1593-1601.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewen P. C., Hengge-Aronis R. The role of the sigma factor sigma S (KatF) in bacterial global regulation. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1994;48:53–80. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.48.100194.000413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonetto M., Gribskov M., Gross C. A. The sigma 70 family: sequence conservation and evolutionary relationships. J Bacteriol. 1992 Jun;174(12):3843–3849. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.12.3843-3849.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCann M. P., Kidwell J. P., Matin A. The putative sigma factor KatF has a central role in development of starvation-mediated general resistance in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1991 Jul;173(13):4188–4194. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.13.4188-4194.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulvey M. R., Loewen P. C. Nucleotide sequence of katF of Escherichia coli suggests KatF protein is a novel sigma transcription factor. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989 Dec 11;17(23):9979–9991. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.23.9979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen L. H., Jensen D. B., Thompson N. E., Gentry D. R., Burgess R. R. In vitro functional characterization of overproduced Escherichia coli katF/rpoS gene product. Biochemistry. 1993 Oct 19;32(41):11112–11117. doi: 10.1021/bi00092a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich J. J., Hirano S. S., Willis D. K. Pathovar-specific requirement for the Pseudomonas syringae lemA gene in disease lesion formation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992 May;58(5):1440–1446. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.5.1440-1446.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich J. J., Willis D. K. A single oligonucleotide can be used to rapidly isolate DNA sequences flanking a transposon Tn5 insertion by the polymerase chain reaction. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990 Nov 25;18(22):6673–6676. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.22.6673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takai K., Hayaishi O. Purification and properties of tryptophan side chain oxidase types I and II from Pseudomonas. Methods Enzymol. 1987;142:195–217. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(87)42029-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K., Takahashi H. Cloning, analysis and expression of an rpoS homologue gene from Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. Gene. 1994 Dec 2;150(1):81–85. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90862-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K., Takayanagi Y., Fujita N., Ishihama A., Takahashi H. Heterogeneity of the principal sigma factor in Escherichia coli: the rpoS gene product, sigma 38, is a second principal sigma factor of RNA polymerase in stationary-phase Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993 Apr 15;90(8):3511–3515. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams M. D., Ouyang T. X., Flickinger M. C. Starvation-induced expression of SspA and SspB: the effects of a null mutation in sspA on Escherichia coli protein synthesis and survival during growth and prolonged starvation. Mol Microbiol. 1994 Mar;11(6):1029–1043. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00381.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson M., Lindow S. E. Inoculum Density-Dependent Mortality and Colonization of the Phyllosphere by Pseudomonas syringae. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994 Jul;60(7):2232–2237. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.7.2232-2237.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou P., Mocek U., Siesel B., Floss H. G. Biosynthesis of pyrrolnitrin. Incorporation of 13C, 15N double-labelled D- and L-tryptophan. J Basic Microbiol. 1992;32(3):209–214. doi: 10.1002/jobm.3620320312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]