Abstract

The mammalian immune system is tasked with protecting the host against a broad range of threats. Understanding how immune populations leverage cellular diversity to achieve this breadth and flexibility, particularly during dynamic processes such as differentiation and antigenic response, is a core challenge that is well suited for single cell analysis. Recent years have witnessed transformative and intersecting advances in nanofabrication and genomics that enable deep profiling of individual cells, affording exciting opportunities to study heterogeneity in the immune response at an unprecedented scope. In light of these advances, here we review recent work exploring how immune populations generate and leverage cellular heterogeneity at multiple molecular and phenotypic levels. Additionally, we highlight opportunities for single cell technologies to shed light on the causes and consequences of heterogeneity in the immune system.

Population heterogeneity – from the ‘top down’ to the ‘bottom up’

The bulk output of an immune response represents the combined behaviors of a highly diverse ensemble. Many unique subsets of cells work together to fight a range of potential threats, maintain long-term memory, and establish tolerance [1,2]. Moreover, the interplay between these groups of cells establishes checks and balances, which are essential for protecting against autoimmunity or immunodeficiency [3-6]. Measuring these phenomenon in bulk populations, however, blends and potentially masks the unique contributions of individual cells, particularly when behaviors are highly heterogeneous, or driven by rare cell types.

A powerful approach to characterize and study this diversity has been to divide a system into distinct subpopulations from the ‘top down’, typically based on the expression of cellular markers, and to subsequently characterize each bin independently. This strategy has not only been essential in first cataloguing the major cell types of the mammalian immune system, but also in iteratively establishing more nuanced functional divisions (Figure 1). For example, pro-inflammatory and regulatory T helper cells inform the delicate balance between immunity and tolerance, and multiple subsets of dendritic cells (DCs) exhibit pathogen specificity, unique cytokine expression profiles, and antigen-specific cell pairing (reviewed in {Merad:2013hf, Lewis:2012gk}). The same holds for all major immune cell lineages, where the system output is dependent on the combined actions of highly heterogeneous ensembles [7-9].

Figure 1.

Schematic of scientific approaches to profile cellular heterogeneity. Conventionally, samples have been subdivided from the ‘top down’ (blue arrows) based marker expression, and cellular subpopulations are iteratively refined. The emerging single cell profiling techniques reviewed here enable a ‘bottom up’ (red arrows) approach to placing cells into functionally distinct groups and to identify novel molecular and phenotypic markers that define them.

Marker-based subdivision also enables direct measurement of the subpopulation structure, and has revealed that balanced composition is essential for proper immune function. Illustratively, overproduction of pro-inflammatory Th17 cells [3], or an imbalance in the relative proportions of dendritic cell subtypes [10,11], can lead to autoimmune disease. This importance of population composition is further highlighted by studies of tumor-lymphocyte interactions. Here, the density and diversity of tumor infiltrating immune cells has been shown to be predictive of tumor recurrence and clinical outcome [12-14], and immunotherapy methods aim to re-balance the population of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes to maximize their anti-cancer properties [15].

These ‘top down’ approaches, however, are dependent on pre-selection of known markers, creating a bias in experimental design and focusing studies on cell surface protein classification schemes. Additionally, since cells in different bins are averaged together in downstream experiments, it is challenging to study cellular heterogeneity within discrete groups. An alternative and complementary approach is to examine a system by profiling its most basic components individually. Newly emerging approaches that enable high-dimensional profiling of the molecular components in individual cells (see Box 1: Single cell technologies) have the potential to complement existing work and enable a more fundamental understanding of immune response. These technologies enable a complementary ‘bottom up’ experimental design in which high-dimensional molecular profiles measured for each single cell can be used to classify distinct states and types, and allow for detailed analyses of cellular heterogeneity.

Here, we review recent work characterizing heterogeneity in the immune response, placing particular emphasis on the role of emerging single cell profiling strategies in deciphering the causes and consequences of immune cell variation. We highlight what has been learned by studying cellular heterogeneity at multiple levels - from the quantification of nucleic acids and protein levels to downstream differences in cellular phenotype - and discuss exciting opportunities for single cell analysis to learn about cellular diversity and behavior in immune responses from the ‘bottom up’.

Cellular heterogeneity nces in cellular phenotype sources and implications

Both targeted and genome-wide approaches have repeatedly observed enormous variation in the molecular components of genetically ‘identical’ cells from prokaryotes [16], model organisms [17], and mammalian systems [18]. Before further exploring this, it is important to draw a distinction between two distinct sources of cellular variability. Biochemical reactions, governing gene regulation, are discrete and probabilistic events, given the limiting amounts of regulators and nucleic acids within a cell. Thus, gene expression has been widely described as a ‘stochastic process’, and the inherent downstream fluctuations in RNA and protein levels driven by this stochasticity are referred to as ‘intrinsic’ noise [19]. Studies utilizing fluorescent imaging and microfluidic approaches have uncovered strong evidence that both protein [20] and mRNA molecules [21] are produced at high frequency in short ‘bursts’, which are followed by quiescent periods, highlighting the potential for ‘intrinsic’ noise to drive significant cellular variation [22]. Alternately, cellular heterogeneity can reflect differences in molecular drivers that lie upstream of probabilistic protein and mRNA synthesis, for example, differences in cellular state, cycle, or microenvironment, referred to as ‘extrinsic’ noise [19]. Changes in the levels of upstream regulators can thus generate extensive heterogeneity in target genes that can be harnessed to infer biological relationships.

A similar paradigm can be used to describe the potential consequences of heterogeneity. It is not unreasonable to expect that most cell-to-cell differences will have little impact on phenotype, and may represent noisy and ultimately inconsequential fluctuations (i.e., that cellular functions will be ‘robust’ to small deviations). For those that do impact cellular behavior, an important and exciting avenue of research is to connect observed differences in molecular composition to changes in cellular capabilities and behavior. Notably, ‘intrinsic’ noise cannot be assumed to be inconsequential. Indeed, stochastic fluctuations may serve to increase the phenotypic diversity of a population [23,24], and stochastic events can lead to vast downstream consequences, particularly if they lie upstream of regulatory cascades [25,26]. Below, we explore the sources and ramifications of immune variability at both molecular and phenotypic levels.

Variability in DNA: Looking at sequence and structure

In many cellular systems, cell-to-cell differences in genomic sequence and structure can have negative phenotypic consequences, (e.g. driving oncogenic or resistive behaviors) [27,28]. However, the immune system leverages variability in DNA sequence in order to respond to a broad range of antigens (Figure 2a). B and T cells utilize extensive genetic diversity encoded though V(D)J recombination, a site-specific DNA recombination process (reviewed in [29,30]) to generate myriad T cell receptor (TCRs, ~1018 combinations) and B cell receptor (BCRs, ~1014 combinations [31]. While this diversity is essential for recognition of and defense against a multitude of different pathogens [30], it must also be carefully controlled. Since many combinations can recognize self-antigens and thereby drive the acquisition of autoimmunity (e.g., systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)), effective pruning of autoreactive TCRs and BCRs by negative selection is essential [32,33]. Additionally, aberrant recombination, like translocations, can result in or drive malignancy through the generation of dysregulated signaling pathways [34,35]. Thus, tight control over the development of diverse BCR and TCR repertoires is essential for proper immune function.

Figure 2.

Variation in DNA sequence and structure. (a) B and T lymphocytes leverage variability in DNA sequence in order to express myriad antigen receptors from a small set of genetic loci, enabling responses against a wide range of antigens (Figure 2a). (b) Heterogeneity in nucleosome organization and epigenetic state has been shown to drive phenotypic differences in response and survival. While a nascent field, understanding the mechanisms that establish epigenetic heterogeneity and their ramifications for immune cells is an exciting area for future research.

Emerging single cell profiling strategies (see Box 1: Single cell technologies) enable direct assessment of the sequences of individual clones that have conventionally been obscured during bulk sequencing of the antibody repertoire [36-38]. This promises exciting new avenues for therapeutic intervention by characterizing the distinct clones that impart desirable behaviors (e.g., targeting of HIV infect cells) [39,40], as well as identifying DNA alterations (mutations, translocations, etc) that might underlie hematopoietic malignancies [41-43]. In addition to examining DNA sequence, new profiling strategies (see Box 1: Single cell technologies) allow assessment of DNA methylation and chromatin modifications at the single cell level, suggesting the possibility of linking epigenetic differences with variation in cellular phenotype, as has been seen in other cellular systems (Figure 2b) [28,44]. Finally, single cell variants of Hi-C have recently demonstrated substantial structural variation in the interdomain and transchromosomal contact structures of different individual mouse T cells [45]. Though these technologies are nascent and boutique in their utilization, we envision that future studies will enable us to assess the extent to which these differences, rather than being random temporal fluctuations, reflect and drive biological heterogeneity.

Variability in RNA: Gene expression and splicing

Immune responses are induced, highly dynamic, and driven by complex and interconnected transcriptional networks. The intended actions of individual cells, to a first order, can thus be read out in their RNA profiles. Quantifying RNA levels in responding cells can help to characterize expression heterogeneity, infer its molecular sources and drivers, and better understand its potential impact on cellular decision-making (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Heterogeneity in gene expression. (a) Traditionally, differences in single cell RNA levels have been probed by RNA-FISH which enables measurement of both RNA expression and its spatial organization. This enables direct assessment of how heterogeneity in one may be couple to that of its neighbors. (b) Higher multiplexing of single cell RNA measurements, for example with single cell qPCR, enables the classification of cells along defined molecular signature. (c) Transcriptome-wide approaches, i.e., single cell RNA-Seq, enable an unbiased approach to find structure in cellular heterogeneity and represent a new systems-biology approach for identifying cell types and reconstructing transcriptional networks.

Pioneering studies have revealed that cellular heterogeneity in mRNA expression has multiple sources, and is a hallmark of both inflammatory and antiviral responses. As discussed above, variability in RNA expression can by generated by both stochastic (‘intrinsic’) and tightly regulated (‘extrinsic’) mechanisms. As a canonical example, transcription from the interleukin 4 (Il4) locus has been extensively characterized as a source of ‘intrinsic’ noise in the Th2 response by multiple groups. By fluorescently marking one allele [46], or leveraging genetic polymorphisms [47], these studies showed that Il4 transcription represented a stochastic process in which the activation of each allele is independent and probabilistically regulated. Follow-up studies revealed that these activation probabilities reflected the acetylation and methylation patterns at Il-4 enhancer regions [48,49], and could be augmented by increasing antigen exposure [48]. Supporting a role for epigenetic mechanisms, Mariani et al demonstrated that a computational model of stochastic chromatin opening was capable of accurately reproducing measured Il4 expression patterns [50]. Similar results have been shown for the Il2 locus, where monoallelic expression patterns followed by allelic silencing were proposed to exert tight limits on the overall expression levels of this cytokine [51].

More recently, there has been a focused interest in the causes and consequences of stochastic expression of type I interferons (IFN), which are key determinants of the response to viral infection. Multiple groups have discovered that, particularly at early time points following infection, Ifnb1 expression is stochastically limited to a subset of cells [25,52,53], due to limiting molecular components in multiple upstream pathways ranging from viral sensing to interferon activation [25,52,54]. While the initial cellular decision to express Ifnb1 may represent a probabilistic event, IFN-β secretion affords a powerful paracrine signal that deterministically activates and propagates an antiviral response to neighboring cells [25,55]. A study of naïve CD4 T helper differentiation found a similar phenomenon [26]. In this system, IFN-γ activity is required for ubiquitous expression of the master regulator Tbx21, but the authors surprisingly found that the vast majority of IFN-γ secretion emanated from a rare subpopulation of ‘pioneer’ cells. Taken together, these studies demonstrate the potential for rare or stochastic events to drive population level behaviors, and suggest that cells must place tight controls on these powerful ‘switches’ to avoid both negative and hyperactive responses.

Heterogeneous RNA expression can also be driven by pre-existing variability in the activity of molecular regulators. Detailed studies of 3T3 mouse fibroblasts stimulated with tumor necrosis factor (TNF), revealed an ‘all-or-nothing’ response across single cells that was incompatible with a stochastic process [56]. This digital response is particularly rare at low doses, and is partially linked to upstream variability in cellular sensitivity to stimulation. Here, variations in the downstream dynamics of NF-kB nuclear localization drove heterogeneity in panel of 23 TNF-response genes, depending on their temporal kinetics in the response [56]. By connecting downstream mRNA expression with the activity of a upstream regulatory in single cells, this study raises the intriguing possibility of using downstream expression heterogeneity to infer putative regulatory relationships, potential molecular drivers, and transcriptional network structures. Illustratively, Guo et al [57] used a utilized highly multiplexed single cell qPCR (Box 1) to profile 280 genes in more than 1,500 cells throughout mouse hematopoietic stem cell differentiation. The authors leveraged gene-level correlations across single cells to reconstruct a putative transcriptional network responsible for priming the differentiation of megakaryocytic and erythroid lineage cells, and to identify the polycomb component Ezh2 as a potential cell-cycle regulator in a mouse model of acute myeloid leukemia [57]. A study of CD8+ T cells activation used a similar approach to define distinct cell subsets based on their induced expression profiles after exposure to three different vaccine regimens [58].

Most recently, significant improvements in low-input RNA amplification strategies have enabled unbiased profiling of polyadenylated mRNA from a single cell (i.e. single cell RNA-Seq). Such techniques hold immense promise for globally characterizing cellular heterogeneity in immune responses. We recently used single cell RNA-Seq to profile the response of 18 bone marrow (BM) DCs to lipopolysaccharide [54], and observed extensive cell-to-cell variation, exemplified by bimodal expression patterns, in the activation of core and highly expressed immune response genes. By examining correlations between immune response genes across single cells, we identified distinct maturation states representing variability in the developmental progression of the BMDCs. Additionally, we demonstrated that variation in the expression of the antiviral regulators STAT2 and IRF7 propagates downstream and leads to differential activation of a core antiviral response across BMDCs. However, these two phenomena explained only a small portion (~20%) of the total variability in our dataset, and the initial upstream events that triggered these differences remain unknown. We anticipate that higher-throughput techniques, utilizing both microfluidic [59] and microplate approaches [60,61], will demonstrate the full potential of single cell RNA-Seq to dissect the causes and consequences of cellular heterogeneity.

Our RNA-seq data also revealed striking variability in splicing patterns and isoform usage between single cells: genes that were alternatively spliced in population samples exhibited a strong skew towards the expression of a single isoform in individual cells. Either stochastic or deterministic variation in RNA processing or isoform usage could represent an additional layer for encoding single cell differences, a mechanism that has been well described for generating single cell diversity in both Drosophila [62] and vertebrate neural development [63]. Similar mechanisms likely drive cellular diversity in the immune system, and we anticipate that this will be an exciting area for future single cell studies.

Variability in Protein: Abundance and posttranslational modifications

How cellular variability in mRNA expression translates to heterogeneity in protein levels and phenotype remains an important but poorly understood question. Multiple studies have found only weak global correlations between population measurements of mRNA and protein [64], potentially due to the relative instability and short half life of mRNA species [64]. Although we anticipate that induced immune responses will show greater correlation between RNA and protein at the single cell level (a crucial area for future study) [65], this discrepancy highlights the necessity of studying cellular heterogeneity at the protein level since it is those proteins that drive cellular actions (Figure 4). Moreover, single cell proteomic measurements are needed to understand how cellular signaling and decision-making is influenced by post-translational modifications that can only be observed by directly profiling protein.

Figure 4.

Cell-to-cell differences in protein levels and activity. (a) Directly assessing the levels and activity of important proteins, e.g., transcription factors, can give insights into timing and magnitude of cellular response. Importantly, fluorescence-based techniques allow for time-lapse measurements of the dynamics of single cell expression and localization (e.g., nuclear translocation). (b) High-throughput, multivariate protein profiling strategies, like FACS, enable exploration and precise quantification of population structure by profiling tens of thousands of cells. (c) The recent development of heavy-metal protein detection strategies (CyTOF, see Box 1) has significantly augmented the number of single cell proteins that can be simultaneously measured. This exciting technology will enable an even more detailed under of the immune cell spectrum, the cellular continuum representing hematopoetic differentiation, and its evolution and in health and disease.

Indeed, immune populations exhibit broad distributions of protein abundances for key transcriptional regulators, signaling molecules, and surface receptors. This continuous level of variation can serve to increase the phenotypic diversity of a clonal population, and likely plays an essential role in generating diverse and plastic responses. For example, in a pioneering study of T cell response, Feinerman et al leveraged a computational model of murine T lymphocyte activation to test how the natural expression variability of core signaling components could affect antigen responsiveness. Combining this approach with multiparameter flow cytometry, the authors elucidated how activation thresholds were set using feedback loops involving both membrane and soluble proteins [66]. Further work by the same group demonstrated that broad heterogeneity in IL-2 receptor levels could explain the extensive plasticity observed in Treg suppression [67], and enumerated a general methodology to define the quantitative regulation of T cell cytokine signaling pathways by leveraging cellular heterogeneity [68]. These latter studies also represent an important extension of the ‘top down’ approach - traditionally used to identify and profile distinct subpopulations of cells (Figure 1, Figure 4b) – but applied here to subdivide clonal populations of cells based upon more continuous expression of a cell surface marker.

Similar approaches have also demonstrated that variability in the expression of key signaling receptor molecules encodes future diversity in the terminally differentiated population. The Ahmed group found that a small subpopulation of mouse CD8+ T cells maintains high levels of CD25 expression shortly after acute viral infection, and is highly predisposed against differentiating into long-lived memory cells [69]. These findings were strongly supported by additional studies [70], demonstrating that the bifurcation responsible for producing distinct subsets of memory cells likely occurs at the peak of the vaccine response when there is significant heterogeneity in CD25 levels [71]. Collectively, these studies suggest that cellular populations use continuous levels of variability in the expression of key signaling molecules and receptors in order to mount diverse, effective, and plastic responses.

While fluorescence-based methods allow for multiplexed detection of up to 18 probes, recent developments in mass cytometry (i.e. CyTOF) have substantially increased the number of proteins that can be independently and simultaneously quantified inside a single cell (Figure 4c, see Box 1: Single cell technologies). Bendall et. al [72] applied this approach to measure 52 unique parameters from single cells sampled from human bone marrow. Coupled with a novel minimum spanning-tree algorithm to distill and visualize interconnected cellular subpopulations [73], their analysis split 28 previously identified cell types into 282 novel subclassifications [72]. However, both this seminal work and follow-up studies revealed that cellular heterogeneity often manifests itself on a continuous scale, rather than through multiple discrete subpopulations. Specifically, B-cell and monocyte maturation programs exhibit a spectrum of transitional states [72]. Extending this recurrent theme, further work from the same group found that single cell analysis of acute myeloid leukemia samples revealed “a continuum of heterogeneous phenotype states” [60,61,74], rather than discrete subpopulations, highlighting the limits of traditional biaxial gating strategies.

Variability in phenotype: Robustness on average

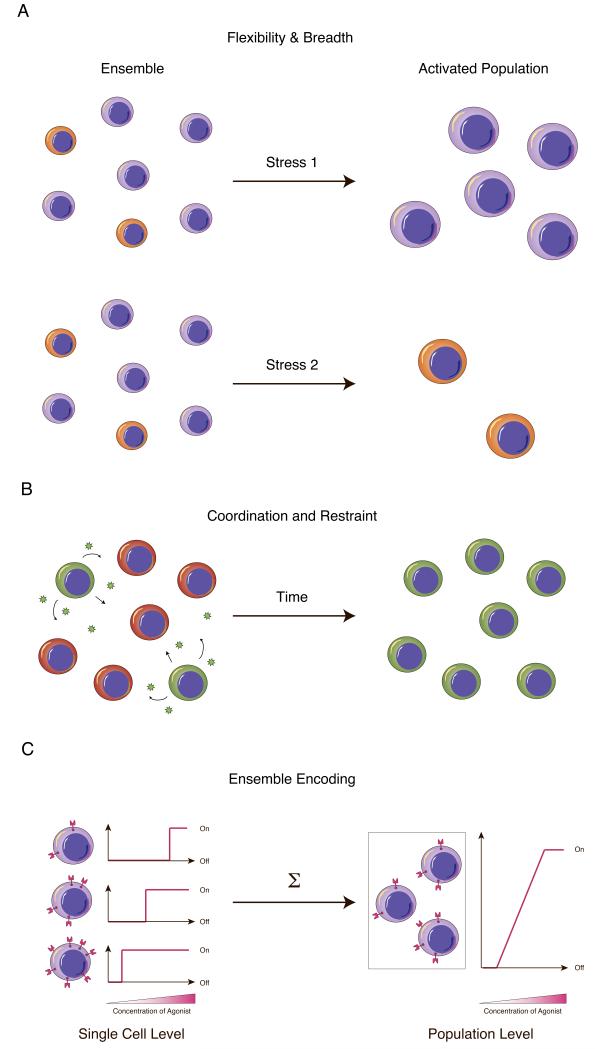

There are many reasons why differences in DNA, RNA, and protein can prove phenotypically advantageous for populations of immune cells. Breadth in response can be achieved through division of labor, where population structure is optimally balanced to achieve flexibility (Figure 5a). Furthermore, differences in phenotypic output (e.g., cytokine expression) can be used as a form of cellular dialog for coordinating and mounting effect immune behaviors (Figure 5b). Heterogeneity can also enable complex population-level responses by blending many simple single cell behaviors (Figure 5c). Even in the absence of molecular mechanism, understand the role of population heterogeneity in maintaining a healthy immune system requires measuring phenotypic variation at the single cell level.

Figure 5.

Advantages achieved through immune cell heterogeneity. (a) Cell-to-cell differences engender flexibility and breadth to the immune system, enabling, for example, response to myriad antigens. (b) In spite of tasking different cells with difference portions of the response, the immune system needs to maintain robustness. One way of coordinating the activity of individual cells is through intercellular communication (e.g., with cytokines). This allows individual cellular responses to be communicated and then propagated or restrained. (c) Heterogeneity in cellular expression can also enable complex population level behaviors from simple single cellular decisions. For example, placing different thresholds on cellular activation can translate a digital decision at the single cell level to a graded analog response at the population level.

Numerous recent studies have highlighted that while phenotypic responses can vary substantially, often, on average, the behavior of the overall population will be consistent. By combining distributions of division and death rates with computational modeling, Hawkins et al [75] showed that stochastic variability in B cell proliferation and apoptosis can give rise to robust immune responses that can be quantitatively regulated at the population level. Subsequent work by the same group [76] explicitly measured the times to isotype switch, to develop into a plasmablast, and to divide or die in single B cells. This data provided experimental evidence that competing stochastic intracellular events can drive heterogeneous B cell fate decisions at the single cell level, while yielding, on average, robust population behaviors that could be shaped by altering the microenvironment in which this stochastic cellular-decision making is performed.

Similar observations of phenotypic variation have been made for T lymphocytes. For example, different naïve CD4+ T cells have been shown to produce highly heterogeneous ratios of macrophage and B cell T helpers upon activation [77]. Nevertheless, those ratios, which are driven in part by differences in the strength of TCR signaling at the single cell level, proved consistent when averaged over all clones [77]. Likewise, in CD8+ T cells, while clonal expansion, differentiation, and recall capacity were shown to be highly heterogeneous – even among cells bearing the same TCR [78,79] – using cellular barcoding strategies, population level-responses were consistent when averaged [66,80]. Interestingly, although the distribution of activated CD8+ clones was different between the first and second stimulations, distributions between the second and third stimulations were not [80]; this suggests that each clone has a distinct ability to reexpand, although the molecular underpinnings of this behavior require further exploration. More generally, these studies reveal a common strategy of encoding multiple cellular responses using different competing stochastic intracellular events whose relative frequencies can be biased through modulating the extracellular milieu. This may represent a preferred ‘bet-hedging’ strategy since it can yield consistency in spite of ‘intrinsic’ noise; still the underlying molecular processes that infer this capability and modulate its sensitivity (e.g., cell-to-cell communication [81]) have yet to be uncovered and are ripe areas for single cell exploration.

In parallel, cellular barcoding has also been used to demonstrate that individual multipotent progenitors can give rise to a diverse range of distinct hematopoietic cell types [82]. Intriguingly, while hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) were able to populate a broad range of different terminal cell types, those same cells seemed to undergo a “graded commitment” process as they developed into lymphoid-primed multipotent progenitors (LMPPs) which biased the progeny to which they gave rise [82]. In these experiments, sibling cells gave rise to similar distributions of terminally differentiated cells, suggesting that lineage imprinting had occurred; still, emerging single cell profiling strategies will be uncover the biomolecular events that underscore this observation [82].

Finally, many of these terminal cell types can, in turn, differentiate into distinct effector subpopulations. For example, naïve CD4+ T cells, once activated by antigen presenting cells and under the bias of the cytokine microenvironment, will give rise to a highly heterogeneous mix of T helper cell subtypes (Th1, Th2, Th17, Treg cells, etc), the balance of which is essential for proper immune function [83], under the biased cytokine microenvironment. Nevertheless, recent work has challenged the orthogonality of these coarse cellular classifications ([84]; for B cells, see [85]). For example, Newell et al [86] showed that individual CD8+ T cells could exhibit complex, combinatorial cytokine expression phenotypes that both populate and link together canonical, distinct cell states (e.g., central memory or terminal effector). Similar functional heterogeneity was observed by Ma et al when examining the secretion profiles from individual tumor antigen-specific CD8+ T cells [87]. Ultimately, we believe that emerging single cell profiling approaches (Box 1) will not only help us to understand the links between cellular heterogeneity’s causes and effects, but also to uncover general design principles that engender specificity and yet flexibility and robustness across the immune system [76].

Concluding Remarks

While heterogeneity has long been recognized as a hallmark of the immune system, experimental constraints have limited our ability to systematic dissect their underlying causes. Recent advances in microfluidics, molecular biology, and mass spectrometry now enable the tracking and profiling of individual cells at unprecedented resolution. These new single cell approaches will undoubtedly refine our cellular classification schemes, revealing new and functionally distinct subsets of cells.

However, what are we to make of the extensive and widespread variation we see between canonically equivalent cells? Cells are fundamentally noisy molecular computers, and systematic measurements will likely reveal that heterogeneity is, in fact, the norm. A challenge for future single cell studies then is to identify what of this variation represents real and biologically meaningful differences and what represents thermal and transient fluctuations.

To understand this, we will need to decipher how molecular variability at different levels is interconnected and drives phenotypic variation. For example, does a broad distribution of surface receptor protein levels simply echo preexisting stochasticity in mRNA transcription? If so, has the immune system evolved to leverage the noisiness of transcription - for example, using this heterogeneity to encode analog responses via a digital event [56,67] (Figure 5c) – or do separate posttranslational mechanisms explicitly control protein variability? Moreover, how does the plasticity of different responses change across environmental conditions and time to enable the immune system to renormalize itself? Finally, what is the interplay between cellular heterogeneity and immunological dysfuction? We envision that, in particular, technological advances enabling joint profiling of multiple different molecular entities (e.g., joint measurements of RNA and protein) will accelerate this discovery process.

Lastly, multiple studies have hinted at the idea that heterogeneity in the immune system is best described using continuous models and is only poorly approximated using binning strategies that discretize cellular phenotypes (for example, [74,84,85]). These traditional gating strategies that bifurcate populations along any specific axis obfuscate the transitional cellular events that link together these complex molecular states. Moving towards more unbiased approaches for profiling individual cells, both in vitro and in vivo, should enable a more nuanced definition of what drives cellular state, diversity, and function and the developmental transitions that tie them together.

Box 1. Technological approaches for deciphering the causes and consequences of heterogeneity.

Experimental strategies for examining single cells

Most conventional profiling strategies lack the sensitivity necessary to quantify the picoscale inputs afforded by individual cells. As a result, single cell profiling approaches typically rely upon preamplification schemes that can be universal or targeted in nature, with the former better suit for discovery efforts and the latter for testing specific hypotheses. Fundamentally, the goal of each of these protocols is to transform a single cell input into a million or so faithful clones, with as little technical bias as is possible, so that they can then be probed like conventional ensembles and biologically meaningful differences can be inferred. Here, we briefly present commonly used and emerging strategies for profiling such single cell inputs. While each technique, itself, is powerful, we envision that coupling many of these strategies together at scale will revolutionize bottom-up discovery processes.

DNA sequence

Since single cells contain one or two copies of most DNA inputs, preamplification is essential. Such preamplification can be genome-wide or targeted in nature, with the selection of method depending the question being asked (e.g., unbiased SNP discovery would require the former while TCR profiling could be performed using the latter). At present, there are three main whole genome amplification (WGA) protocols: 1. Exponential amplification using random primers [88]; 2. Multiple Displacement Amplification (MDA), an isothermal amplification scheme that couples random priming with the strand displacement activity of the Φ29 polymerase [89];and, 3. Multiple Annealing and Looping-Based Amplification Cycles (MALBAC), a quasilinear preamplification approach [90]. Once WGA has been performed, these products can then be examined using conventional quantification methodologies, such as qPCR [89] or DNA sequencing [90]. Targeted approaches, meanwhile, use similar preamplification strategies but replace the universal primers used in WGA with ones specific to certain target loci (see, for example,[31]). Finally, while the aforementioned strategies are implemented in lysates, specific loci can be detected and/or visualized in-situ (e.g., [91]).

DNA structure

Globally, the 3-dimensional structure of a single cell’s DNA can be profiled using Hi-C [45]; locally, DNA-DNA proximity can be assessed using DNA Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (DNA FISH, [92]). DNA modifications can also be profiled in single cells: for example, methylation can be assessed by leveraging the fact that BstUI can only cut unmethylated CGCG sequences [44]; similarly, histone modifications can be detected by combining FISH with proximity ligation strategies [93,94]

RNA profiling

Like DNA, RNA can be profiled either in situ or starting from lysates. Currently used in situ strategies include: molecular beacons and MS2 labeling to profile mRNA dynamics in live cells [95] and conventional RNA-FISH [1] and a novel super resolution variant that relies on combinatorial RNA barcoding [20] to estimate RNA abundance in fixed cells. Additionally, Ke et al recently demonstrated that RNA could also be sequenced directly in situ, enabling assessment of RNA abundance and identification of mutations [96]. While these approaches enable RNA expression to be analyzed across many cells, they can only be used to assess the levels of up to a hundred or so RNAs due to spectral overlap and/or spatial constraints. When starting with lysates, targeted or whole transcriptome amplification can be performed using gene specific [97] or universal priming [59,61,98-100]. Notably, whole transcriptome amplification coupled with sequencing enables the assessment of both RNA abundance and structure [54].

Protein Expression

Unlike the genome and transcriptome, at present, whole proteome profiling is not possible due to a lack of universal affinity reagents. Nevertheless, targeted protein strategies are among the most commonly utilized single cell profiling approaches. The most notable of these are staining with fluorescent (for example, [6]) or heavy-metal labeled (“CyTOF,” [72]) antibodies, as well as the use of fluorescently-tagged proteins (e.g.,[101]). Additional strategies that have been applied include: reverse ELISAs of secreted [102,103] or intracellular proteins [104] and proximity ligation/extension based [105,106]. Notably, proximity ligation/extension methods also enable assessment of protein-dna and protein-protein interactions [91].

Highlights.

Diversity in immune system is encoded by extensive cellular variation

Heterogeneity exists at multiple molecular levels

New single-cell methods enable systematic studies of heterogeneity

Fundamental challenge is to connect molecular variability with phenotypic diversity

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank members of the Regev and Hacohen groups for insightful discussion. RS is supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Postdoctoral Fellowship (1F32HD075541-01).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Raj A, et al. Imaging individual mRNA molecules using multiple singly labeled probes. Nat. Methods. 2008;5:877–879. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Germain RN. Maintaining system homeostasis: the third law of Newtonian immunology. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:902–906. doi: 10.1038/ni.2404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Littman DR, Rudensky AY. Th17 and regulatory T cells in mediating and restraining inflammation. Cell. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wing K, Sakaguchi S. Regulatory T cells exert checks and balances on self tolerance and autoimmunity. Nat Immunol. 2009 doi: 10.1038/ni.1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sakaguchi S, et al. regulatory T cells in the human immune system. Nature Publishing Group. 2010;10:490–500. doi: 10.1038/nri2785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yosef N, et al. Dynamic regulatory network controlling TH17 cell differentiation. Nature. 2013 doi: 10.1038/nature11981. DOI: 10.1038/nature11981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gordon S, Taylor PR. Monocyte and macrophage heterogeneity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2005 doi: 10.1038/nri1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alugupalli KR, Gerstein RM. Divide and conquer: division of labor by B-1 B cells. Immunity. 2005;23:1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shay T, Kang J. Immunological Genome Project and systems immunology. Trends in Immunology. 2013;34:602–609. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakahara T, et al. Cyclophosphamide enhances immunity by modulating the balance of dendritic cell subsets in lymphoid organs. Blood. 2010;115:4384–4392. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-251231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neyt K, Lambrecht BN. The role of lung dendritic cell subsets in immunity to respiratory viruses. Immunol. Rev. 2013;255:57–67. doi: 10.1111/imr.12100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galon J. Type, Density, and Location of Immune Cells Within Human Colorectal Tumors Predict Clinical Outcome. Science. 2006;313:1960–1964. doi: 10.1126/science.1129139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gajewski TF, et al. Innate and adaptive immune cells in the tumor microenvironment. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:1014–1022. doi: 10.1038/ni.2703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bindea G, et al. Spatiotemporal dynamics of intratumoral immune cells reveal the immune landscape in human cancer. Immunity. 2013;39:782–795. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Restifo NP, et al. Adoptive immunotherapy for cancer: harnessing the T cell response. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2012;12:269–281. doi: 10.1038/nri3191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elowitz MB. Stochastic Gene Expression in a Single Cell. Science. 2002;297:1183–1186. doi: 10.1126/science.1070919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bar-Even A, et al. Noise in protein expression scales with natural protein abundance. Nat. Genet. 2006;38:636–643. doi: 10.1038/ng1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raj A, van Oudenaarden A. Nature, nurture, or chance: stochastic gene expression and its consequences. Cell. 2008;135:216–226. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Swain PS, et al. Intrinsic and extrinsic contributions to stochasticity in gene expression. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2002;99:12795–12800. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162041399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lubeck E, Cai L. Single-cell systems biology by super-resolution imaging and combinatorial labeling. Nat. Methods. 2012 doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raj A, et al. Stochastic mRNA Synthesis in Mammalian Cells. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e309. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blake WJ, et al. Noise in eukaryotic gene expression. Nature. 2003 doi: 10.1038/nature01546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eldar A, Elowitz MB. Functional roles for noise in genetic circuits. Nature. 2010;467:167–173. doi: 10.1038/nature09326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blake WJ, et al. Phenotypic Consequences of Promoter-Mediated Transcriptional Noise. Molecular Cell. 2006;24:853–865. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rand U, et al. Multi-layered stochasticity and paracrine signal propagation shape the type-I interferon response. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2012;8:584. doi: 10.1038/msb.2012.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fang M, et al. Stochastic cytokine expression induces mixed T helper cell States. PLoS Biol. 2013;11:e1001618. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Solit DB, et al. BRAF mutation predicts sensitivity to MEK inhibition. Nature. 2006;439:358–362. doi: 10.1038/nature04304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sharma SV, et al. A Chromatin-Mediated Reversible Drug-Tolerant State in Cancer Cell Subpopulations. Cell. 2010;141:69–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schatz DG, et al. V(D)J recombination: molecular biology and regulation. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1992;10:359–383. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.10.040192.002043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jung D, Alt FW. Unraveling V (D) J recombination: insights into gene regulation. Cell. 2004;116:299–311. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00039-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li HH, et al. Amplification and analysis of DNA sequences in single human sperm and diploid cells. Nature. 1988;335:414–417. doi: 10.1038/335414a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jameson SC, et al. Positive selection of thymocytes. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1995;13:93–126. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.13.040195.000521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grimaldi CM, et al. B cell selection and susceptibility to autoimmunity. J. Immunol. 2005;174:1775–1781. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.4.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Davis RE, et al. Chronic active B-cell-receptor signalling in diffuselarge B-cell lymphoma. Nature. 2010;463:88–92. doi: 10.1038/nature08638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Niemann CU, Wiestner A. Seminars in Cancer Biology. Seminars in Cancer Biology. 2013;23:410–421. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maryanski JL, et al. Single-cell PCR analysis of TCR repertoires selected by antigen in vivo: a high magnitude CD8 response is comprised of very few clones. Immunity. 1996;4:47–55. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80297-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dash P, et al. Paired analysis of TCRβ and TCRβ chains at the single-cell level in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2011;121:288–295. doi: 10.1172/JCI44752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cebula A, et al. Thymus-derived regulatory T cells contribute to tolerance to commensal microbiota. Nature. 2013;497:258–262. doi: 10.1038/nature12079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schumacher TNM. T-cell-receptor gene therapy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2002;2:512–519. doi: 10.1038/nri841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rossi JJ, et al. Genetic therapies against HIV. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:1444–1454. doi: 10.1038/nbt1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Navin N, et al. Tumour evolution inferred by single-cell sequencing. Nature. 2012;472:90–94. doi: 10.1038/nature09807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jan M, et al. Clonal Evolution of Preleukemic Hematopoietic Stem Cells Precedes Human Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Science Translational Medicine. 2012;4:149ra118–149ra118. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Landau DA, et al. Evolution and Impactof Subclonal Mutationsin Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Cell. 2013;152:714–726. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lorthongpanich C, et al. Single-Cell DNA-Methylation Analysis Reveals Epigenetic Chimerism in Preimplantation Embryos. Science. 2013;341:1110–1112. doi: 10.1126/science.1240617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nagano T, et al. Single-cell Hi-C reveals cell-to-cell variability in chromosome structure. Nature. 2013 doi: 10.1038/nature12593. DOI: 10.1038/nature12593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Riviere I, et al. Regulation of IL-4 expression by activation of individual alleles. Immunity. 1998 doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80604-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bix M, Locksley RM. Independent and epigenetic regulation of the interleukin-4 alleles in CD4+ T cells. Science. 1998 doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guo L, et al. Probabilistic regulation of IL-4 production in Th2 cells: accessibility at the Il4 locus. Immunity. 2004 doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(04)00025-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guo L, et al. Probabilistic Regulation in TH2 Cells Accounts for Monoallelic Expression of IL-4 and IL-13. Immunity. 2005;23:89–99. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mariani L, et al. Short-term memory in gene induction reveals the regulatory principle behind stochastic IL-4 expression. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2010;6:359–359. doi: 10.1038/msb.2010.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Holl auml nder GA. Monoallelic Expression of the Interleukin-2 Locus. Science. 1998;279:2118–2121. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5359.2118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhao M, et al. Stochastic expression of the interferon-β gene. PLoS Biol. 2012;10:e1001249. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hu J, et al. Role of cell-to-cell variability in activating a positive feedback antiviral response in human dendritic cells. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e16614. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shalek AK, et al. Single-cell transcriptomics reveals bimodality in expression and splicing in immune cells. Nature. 2013;498:236–240. doi: 10.1038/nature12172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shimoni Y, et al. Multi-scale stochastic simulation of diffusion-coupled agents and its application to cell culture simulation. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e29298. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tay S, et al. Single-cell NF-kappaB dynamics reveal digital activation and analogue information processing. Nature. 2010;466:267–271. doi: 10.1038/nature09145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Guo G, et al. Mapping cellular hierarchy by single-cell analysis of the cell surface repertoire. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;13:492–505. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Flatz L, et al. Single-cell gene-expression profiling reveals qualitatively distinct CD8 T cells elicited by different gene-based vaccines. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2011;108:5724–5729. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013084108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mantalas GL, et al. Quantitative assessment of single-cell RNA-sequencing methods. Nature. 2014 doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Picelli S, et al. Smart-seq2 for sensitive full-length transcriptome profiling in single cells. Nat. Methods. 2013;10:1096–1098. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hashimshony T, et al. CEL-Seq: single-cell RNA-Seq by multiplexed linear amplification. Cell reports. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Miura SK, et al. Probabilistic splicing of Dscam1 establishes identity at the level of single neurons. Cell. 2013;155:1166–1177. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lefebvre JL, et al. Protocadherins mediate dendritic self-avoidance in the mammalian nervous system. Nature. 2012;488:517–521. doi: 10.1038/nature11305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schwanhäusser B, et al. Global quantification of mammalian gene expression control. Nature. 2011;473:337–342. doi: 10.1038/nature10098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Munsky B, et al. Using gene expression noise to understand gene regulation. Science. 2012;336:183–187. doi: 10.1126/science.1216379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Feinerman O, et al. Variability and robustness in T cell activation from regulated heterogeneity in protein levels. Science. 2008 doi: 10.1126/science.1158013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Feinerman O, et al. Single-cell quantification of IL-2 response by effector and regulatory T cells reveals critical plasticity in immune response. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2010;6:437. doi: 10.1038/msb.2010.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cotari JW, et al. Cell-to-Cell Variability Analysis Dissects the Plasticity of Signaling of Common {gamma} Chain Cytokines in T Cells. Science. 2013 doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2003240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kalia V, et al. Prolonged Interleukin-2Rβ Expression on Virus-Specific CD8+ T Cells Favors Terminal-Effector Differentiation In Vivo. Immunity. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pipkin ME, et al. Interleukin-2 and inflammation induce distinct transcriptional programs that promote the differentiation of effector cytolytic T cells. Immunity. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Choi YS, et al. Bcl6 expressing follicular helper CD4 T cells are fate committed early and have the capacity to form memory. J. Immunol. 2013;190:4014–4026. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bendall SC, et al. Single-cell mass cytometry of differential immune and drug responses across a human hematopoietic continuum. Science. 2011;332:687–696. doi: 10.1126/science.1198704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Qiu P, et al. Extracting a cellular hierarchy from high-dimensional cytometry data with SPADE. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:886–891. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Amir ED, et al. viSNE enables visualization of high dimensional single-cell data and reveals phenotypic heterogeneity of leukemia. Nature. 2013 doi: 10.1038/nbt.2594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hawkins ED, et al. A model of immune regulation as a consequence of randomized lymphocyte division and death times. 2007 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700026104. presented at the Proceedings of the …. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Duffy KR, et al. Activation-induced B cell fates are selected by intracellular stochastic competition. Science. 2012;335:338–341. doi: 10.1126/science.1213230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tubo NJ, et al. Single Naive CD4. Cell. 2013;153:785–796. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Stemberger C, et al. A Single Naive CD8+ T Cell Precursor Can Develop into Diverse Effector and Memory Subsets. Immunity. 2007;27:985–997. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gerlach C, et al. One naive T cell, multiple fates in CD8+ T cell differentiation. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2010;207:1235–1246. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gerlach C, et al. Heterogeneous Differentiation Patterns of Individual CD8+ T Cells. Science. 2013;340:635–639. doi: 10.1126/science.1235487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Koseska A, et al. Timing Cellular Decision Making Under Noise via Cell-Cell Communication. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e4872. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Naik SH, et al. Diverse and heritable lineage imprinting of early haematopoietic progenitors. Nature. 2013;496:229–232. doi: 10.1038/nature12013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhu J, et al. Differentiation of Effector CD4 T Cell Populations *. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2010;28:445–489. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.O’Shea JJ, Paul WE. Mechanisms underlying lineage commitment and plasticity of helper CD4+ T cells. Science. 2010;327:1098–1102. doi: 10.1126/science.1178334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tarlinton D, Good-Jacobson K. Diversity among memory B cells: origin, consequences, and utility. Science. 2013 doi: 10.1126/science.1241146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Newell EW, et al. Cytometry by Time-of-Flight Shows Combinatorial Cytokine Expression and Virus-Specific Cell Niches within a Continuum of CD8. Immunity. 2012;36:142–152. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ma C, et al. A clinical microchip for evaluation of single immune cells reveals high functional heterogeneity in phenotypically similar T cells. Nat. Med. 2011;17:738–743. doi: 10.1038/nm.2375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zhang L, et al. Whole genome amplification from a single cell: implications for genetic analysis. 1992 doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.13.5847. Proceedings of the …. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wang J, et al. Genome-wide single-cell analysis of recombination activity and de novo mutation rates in human sperm. Cell. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zong C, et al. Genome-Wide Detection of Single-Nucleotide and Copy-Number Variations of a Single Human Cell. Science. 2012;338:1622–1626. doi: 10.1126/science.1229164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Conze T, et al. Analysis of Genes, Transcripts, and Proteins via DNA Ligation. Annual Review of Analytical Chemistry. 2009;2:215–239. doi: 10.1146/annurev-anchem-060908-155239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Pinkel D, et al. Fluorescence in situ hybridization with human chromosome-specific libraries: detection of trisomy 21 and translocations of chromosome 4. 1988 doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.23.9138. presented at the Proceedings of the …. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gomez D, et al. Detection of histone modifications at specific gene loci in single cells in histological sections. Nat. Methods. 2013 doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hattori N, et al. Visualization of multivalent histone modification in a single cell reveals highly concerted epigenetic changes on differentiation of embryonic stem cells. Nucleic Acids Research. 2013;41:7231–7239. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Raj A, van Oudenaarden A. Single-molecule approaches to stochastic gene expression. Annual review of biophysics. 2009 doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.125928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ke R, et al. In situ sequencing for RNA analysis in preserved tissue and cells. Nat. Methods. 2013;10:857–860. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Dalerba P, et al. Single-cell dissection of transcriptional heterogeneity in human colon tumors. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:1120–1127. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Tang F, et al. RNA-Seq analysis to capture the transcriptome landscape of a single cell. Nat Protoc. 2010;5:516–535. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ramsköld D, et al. Full-length mRNA-Seq from single-cell levels of RNA and individual circulating tumor cells. Nature. 2012 doi: 10.1038/nbt.2282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Cohen AA, et al. Dynamic Proteomics of Individual Cancer Cells in Response to a Drug. Science. 2008;322:1511–1516. doi: 10.1126/science.1160165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Love JC, et al. A microengraving method for rapid selection of single cells producing antigen-specific antibodies. Nature. 2006 doi: 10.1038/nbt1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Fan R, et al. Integrated barcode chips for rapid, multiplexed analysis of proteins in microliter quantities of blood. Nature. 2008 doi: 10.1038/nbt.1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Shi Q, et al. Single-cell proteomic chip for profiling intracellular signaling pathways in single tumor cells. 2012 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110865109. presented at the Proceedings of the …. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Fredriksson S, et al. Protein detection using proximity-dependent DNA ligation assays. Nature. 2002 doi: 10.1038/nbt0502-473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Hammond M, et al. Profiling cellular protein complexes by proximity ligation with dual tag microarray readout. PLoS ONE. 2012 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]