Abstract

Objective

Cross-sectional studies have found that low-income and racial/ethnic minority women are more likely to use female sterilization and less likely to rely on a partner’s vasectomy than women with higher incomes and whites. However, studies of pregnant and postpartum women report that racial/ethnic minorities, particularly low-income minority women, face greater barriers in obtaining a sterilization than do whites and those with higher incomes. In this paper, we address this apparent contradiction by examining the likelihood a woman gets a sterilization following each delivery, which removes from the comparison any difference in the number of births she has experienced.

Study Design

Using the 2006–2010 National Survey of Family Growth, we fit multivariable-adjusted logistic and Cox regression models to estimate odds ratios and hazard ratios for getting a postpartum or interval sterilization, respectively, according to race/ethnicity and insurance status.

Results

Women’s chances of obtaining a sterilization varied by both race/ethnicity and insurance. Among women with Medicaid, whites were more likely to use female sterilization than African Americans and Latinas. Privately insured whites were more likely to rely on vasectomy than African Americans and Latinas, but among women with Medicaid-paid deliveries reliance on vasectomy was low for all racial/ethnic groups.

Conclusions

Low-income racial/ethnic minority women are less likely to undergo sterilization following delivery compared to low-income whites and privately insured women of similar parities. This could result from unique barriers to obtaining permanent contraception and could expose women to the risk of future unintended pregnancies.

Keywords: female sterilization, postpartum sterilization, interval sterilization, race/ethnicity, National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG)

1. Introduction

In the United States (US), 37% of reproductive aged women using contraception rely on a permanent method [1], but the percentage using female sterilization or relying on a partner’s vasectomy varies across groups. African Americans, Latinas and low-income women are more likely to use female sterilization than whites and women with higher incomes after controlling for other characteristics [2,3]. In contrast, vasectomy is more common among whites and those with higher incomes [4,5]. These differences have prompted concern that providers may be promoting female sterilization among low-income and minority women, or, alternatively that partner attitudes, may constrain women’s contraceptive choices [2,3].

However, evidence is accumulating that racial/ethnic minority and low-income women experience barriers accessing female sterilization, and that there is frustrated demand for the procedure. African American and Latina women report their providers dissuaded them from getting a sterilization because they were seen as too young or having too few children [6,7]. Low-income women also cite Medicaid-eligibility requirements, such as signing a consent form 30 days in advance of the procedure, as barriers to obtaining a desired postpartum sterilization [7–10]. Moreover, the inability to obtain a sterilization postpartum may result in subsequent unintended pregnancies [11].

In this paper, we address the apparent contradiction between the higher prevalence of sterilization among minority women and findings indicating that minority women, particularly low-income minority women, face barriers in obtaining a sterilization. Our approach examines the likelihood a woman will get a sterilization following delivery. In contrast with a cross-sectional analysis, this metric focuses on comparable exposures, and effectively removes from the comparison across racial/ethnic groups any difference in the number of births a woman has experienced.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data and study sample

We used the 2006–2010 National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG), a nationally representative survey of women and men aged 15–44 years that is conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics. Participants complete an in-person interview and are selected using a multistage probability sample; African American and Latino respondents are oversampled [12].

The data primarily come from the female pregnancy file, which contains detailed information on each of the 20,497 pregnancies from female respondents; this information included the payment source for delivery for live births that occurred within five years of survey date. We also used the female respondent file that included the dates of women’s tubal ligation or partner’s vasectomy, which enabled us to determine timing of the sterilization procedure relative to delivery.

We classified sterilizations as postpartum or interval procedures. Since only the month and year of births and sterilization procedures are available in the NSFG, we considered postpartum female sterilizations as those which occurred in the same month and year as delivery; if a woman reported her partner’s vasectomy occurred in the months between conception and delivery, we classified this as a postpartum vasectomy. Sterilizations that occurred one month postpartum or later were considered interval procedures.

We restricted our sample to second and higher order births that occurred within five years of the interview date (n=3,112), since sterilization among primiparous women is uncommon [1] and payment source for delivery was not available for earlier pregnancies. Women whose delivery was not paid by Medicaid or private insurance were excluded due to small sample size (n=124). We also omitted observations with illogical dates (n=9). The final sample consisted of 2,979 births to 2,393 women.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

We computed the frequency of births, postpartum and interval female sterilizations and vasectomies and, for the interval period, the number of person-months of exposure to the likelihood of obtaining a sterilization. We computed these frequencies by women’s age, parity, educational attainment, race/ethnicity, and whether their delivery was paid by private insurance or Medicaid. All of these variables have been significantly associated with sterilization in previous studies using the NSFG [2,4,5,13].

Next, we estimated multivariable-adjusted logistic regression models to assess the association between these covariates and obtaining any postpartum sterilization procedure (male or female) and postpartum female sterilization only. Since previous studies found differences by insurance in the proportion of minority women using sterilization compared with whites [2], we also tested for interactions between race/ethnicity and payment source for delivery using likelihood ratio tests. We present the models including the interaction term, since the p-value for the likelihood ratio test was <0.10, indicating the association between race/ethnicity and obtaining a sterilization differed by payment source for delivery. To facilitate the interpretation of the interaction, we estimated predicted probabilities for women age 30–34 years with two children and a high school diploma/some college, for each combination of race/ethnicity and insurance. We used these characteristics as our reference because women age 30 or older are more likely to be considered appropriate candidates for sterilization, [14] and those with high school/some college were as likely to have their birth paid by Medicaid as by private insurance.

For women who did not obtain a postpartum sterilization, we fit multivariable-adjusted Cox models to compute hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals for obtaining an interval procedure, using the same covariates as in the logistic model and interactions between race/ethnicity and insurance. Women’s chances of obtaining an interval sterilization began the month after she delivered a live born infant. Women who became pregnant again were censored at the time of conception and re-entered the sample following delivery of their next live birth. We tested the proportional hazards assumption by creating interactions between analysis time and the covariates. The association between most covariates and both any interval procedure and interval female sterilization was similar across time. The p-value for likelihood ratio tests comparing models with and without the interaction between race/ethnicity and insurance was <0.10; therefore, we only present the models which include the interaction.

We estimated the cumulative incidence of obtaining any interval sterilization and female sterilization only in the 24 months following delivery for women age 30–34 years with two children and a high school diploma/some college, for each combination of race/ethnicity and insurance. As a final step, we computed cumulative probabilities of obtaining any sterilization procedure and female sterilization only for each race/ethnicity and insurance combination from the time of delivery through 24 months postpartum.

All analyses were conducted using Stata 11.0 (College Station, TX) and weighted to account for the complex sampling design of the NSFG. Institutional Review Board approval was not required for the analysis of this public use data set.

3. Results

Among the 2,979 births that occurred in the five years prior to the survey, there were 727 sterilizations (Table 1). Of these, 589 (81%) were female sterilizations and 138 (19%) were vasectomies. The majority of female sterilizations were postpartum procedures (71%). Just under half (42%) of interval sterilizations were vasectomies. The distribution of vasectomies is extremely uneven across deliveries classified by the mother’s level of education, race/ethnicity, and insurance status, with the majority of these procedures being reported by women with a college degree, who are white and have private insurance.

Table 1.

Distribution of births, postpartum and interval female sterilizations and vasectomies, and person-months of exposure among women delivering live born infants within five years of the survey date

| Births | Postpartum sterilizations (n=439) |

Interval sterilizations (n=288) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female sterilization |

Vasectomy | Female sterilization |

Vasectomy | Person-months of exposure |

||

| Age at delivery, years | ||||||

| 15 – 24 | 901 | 65 | 2 | 43 | 9 | 18,977 |

| 25 – 29 | 979 | 132 | 5 | 63 | 27 | 19,182 |

| 30 – 34 | 722 | 136 | 8 | 39 | 48 | 14,412 |

| ≥ 35 | 377 | 88 | 3 | 23 | 36 | 7,070 |

| Parity at delivery | ||||||

| 2 children | 1,494 | 120 | 3 | 56 | 64 | 33,658 |

| 3 children or more | 1,485 | 301 | 15 | 112 | 56 | 25,983 |

| Educational attainment at delivery | ||||||

| Less than high school | 915 | 127 | 3 | 54 | 2 | 17,300 |

| High school diploma/some college | 1,364 | 255 | 5 | 89 | 45 | 26,569 |

| College degree | 700 | 69 | 10 | 25 | 73 | 15,772 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| White | 1,170 | 161 | 12 | 76 | 96 | 22,856 |

| African American | 710 | 101 | 1 | 40 | 6 | 13,798 |

| Latina | 889 | 131 | 4 | 41 | 11 | 18,828 |

| Other | 210 | 28 | 1 | 11 | 7 | 4,159 |

| Payment for delivery | ||||||

| Private insurance | 1,234 | 158 | 13 | 69 | 109 | 26,458 |

| Medicaid | 1,745 | 263 | 5 | 99 | 11 | 33,183 |

| TOTAL | 2,979 | 421 | 18 | 168 | 120 | 59,641 |

Source: NSFG 2006–2010

Given that the vast majority of postpartum procedures were female sterilizations, we present the logistic model results for this outcome only (Table 2, left column). Women ≤24 years (versus women 30–34) and those with a college degree (versus high school/some college education) had significantly lower odds of obtaining a female sterilization. Compared with women delivering their second child, women delivering a third or higher order birth were more likely to obtain a female sterilization.

Table 2.

Multivariable adjusted Odds Ratios for postpartum sterilizations and Hazard Ratios for interval sterilizations

| Postpartum sterilizationsa |

Interval sterilizationsb | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Female sterilization |

Any sterilization procedure |

Female sterilization |

|

| OR(95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | |

| Age at delivery, years | |||

| 15 – 24 | 0.33 (0.20 – 0.56) | 0.86 (0.53 – 1.39) | 0.84 (0.42 – 1.69) |

| 25 – 29 | 0.64 (0.39 – 1.04) | 1.01 (0.68 – 1.49) | 1.09 (0.61 – 1.94) |

| 30 – 34 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| ≥ 35 | 1.44 (0.91 – 2.28) | 0.90 (0.57 – 1.41) | 0.63 (0.28 – 1.44) |

| Parity at delivery | |||

| 2 children | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| 3 children or more | 2.31 (1.61 – 3.31) | 1.85 (1.32 – 2.61) | 2.57 (1.56 – 4.23) |

| Educational attainment at delivery | |||

| Less than high school | 1.02 (0.61 – 1.71) | 0.91 (0.53 – 1.57) | 0.97 (0.58 – 1.63) |

| High school diploma/some college | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| College degree | 0.51 (0.31 – 0.85) | 0.97 (0.65 – 1.45) | 0.52 (0.26 – 1.04) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| African American | 1.18 (0.57 – 2.48) | 0.66 (0.34 – 1.31) | 1.55 (0.64 – 3.78) |

| Latina | 2.14 (1.08 – 4.26) | 0.48 (0.26 – 0.90) | 0.84 (0.36 – 1.94) |

| Other | 0.79 (0.31 – 2.04) | 0.81 (0.37 – 1.78) | 2.20 (0.81 – 6.01) |

| Payment for delivery | |||

| Private insurance | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Medicaid | 2.34 (1.45 – 3.76) | 0.86 (0.45 – 1.65) | 1.89 (0.80 – 4.45) |

| Race/ethnicity * Payment for delivery | |||

| African American * Medicaid | 0.56 (0.22 – 1.42) | 0.48 (0.16 – 1.37) | 0.21 (0.06 – 0.76) |

| Latina * Medicaid | 0.20 (0.08 – 0.47) | 0.60 (0.21 – 1.73) | 0.36 (0.11 – 1.21) |

| Other * Medicaid | 0.50 (0.13 – 1.83) | 0.84 (0.25 – 2.81) | 0.29 (0.07 – 1.12) |

Source: NSFG 2006–2010

OR = Odds ratio; HR = Hazard ratio; CI = Confidence interval

Odds ratios obtained from logistic regression models.

Hazard ratios obtained from Cox models.

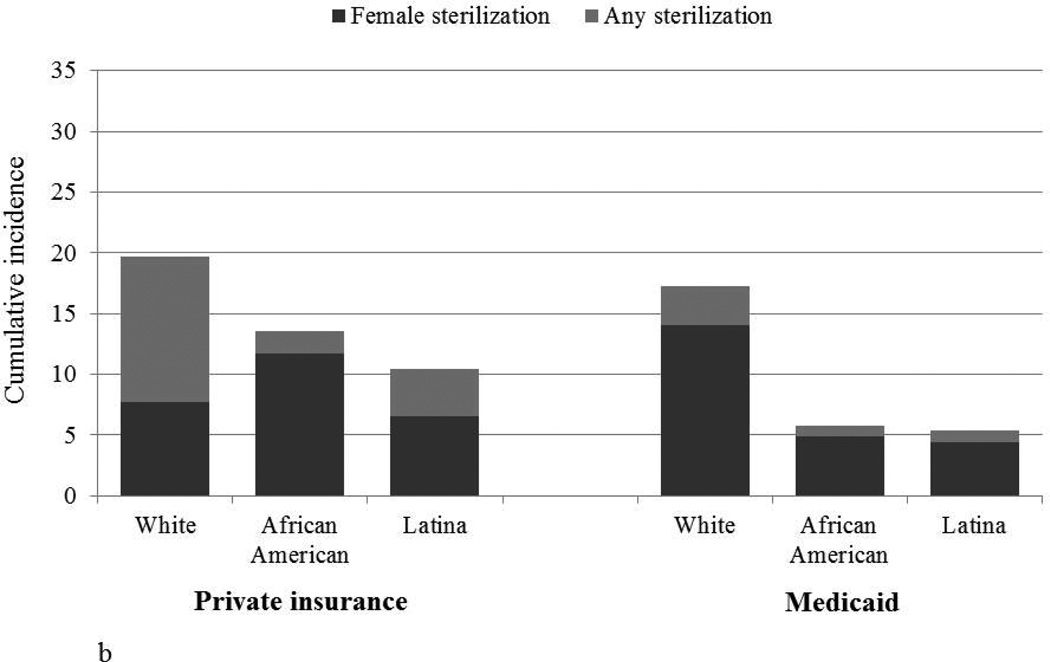

Among women whose delivery was paid by private insurance, Latinas were more likely to obtain a postpartum female sterilization than whites (Figure 1a). In contrast, Latinas with Medicaid-paid deliveries were less likely to obtain a postpartum sterilization than whites, who had the highest probability of postpartum sterilization. There were no significant differences between African Americans and whites within each insurance status.

Figure 1.

a. Predicted probability of postpartum female sterilization, by race/ethnicity and insurancea

b. Cumulative incidence of interval sterilization within 24 months postpartum by race/ethnicity and insuranceb

Source: NSFG 2006–2010

a. Predicted probabilities for women age 30–34 with 2 children and high school/some college education, estimated from multivariable-adjusted logistic regression models (Table 2).

b. Cumulative incidence for women age 30–34 with 2 children and high school/some college education, estimated from multivariable-adjusted Cox regression models (Table 2).

There was not a significant association between age and the likelihood of obtaining any interval sterilization procedure or interval female sterilization (Table 2, right columns). Women with three or more children were more likely to obtain any sterilization and female sterilization compared with women who have 2 children. Although there was no significant difference in obtaining any interval sterilization for women with a college degree compared with women who have high school/some college education, college educated women were less likely to undergo an interval female sterilization, indicating their partners are more likely to get vasectomies.

Among women with private insurance, African Americans and Latinas were less likely to obtain any interval sterilization compared with whites (Figure 1b), but the difference was only significant for Latinas. There were no significant racial/ethnic differences for interval female sterilization for privately insured women. However, both African Americans and Latinas with Medicaid-paid deliveries were less likely than whites with Medicaid to have any interval sterilization procedure or obtain an interval female sterilization.

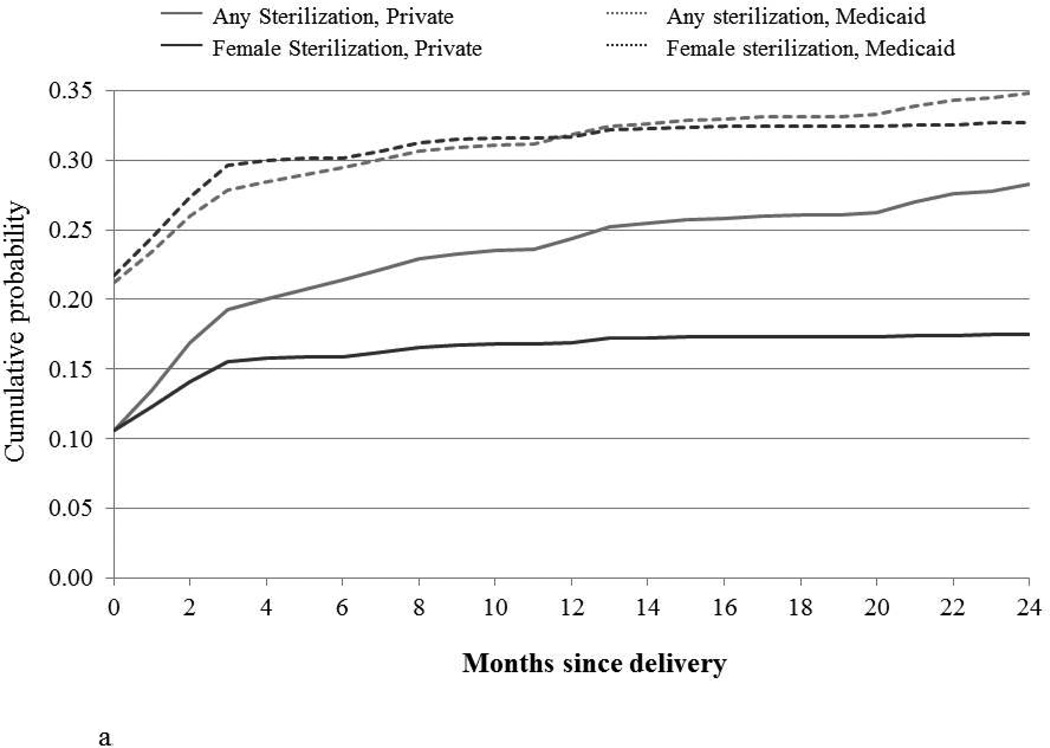

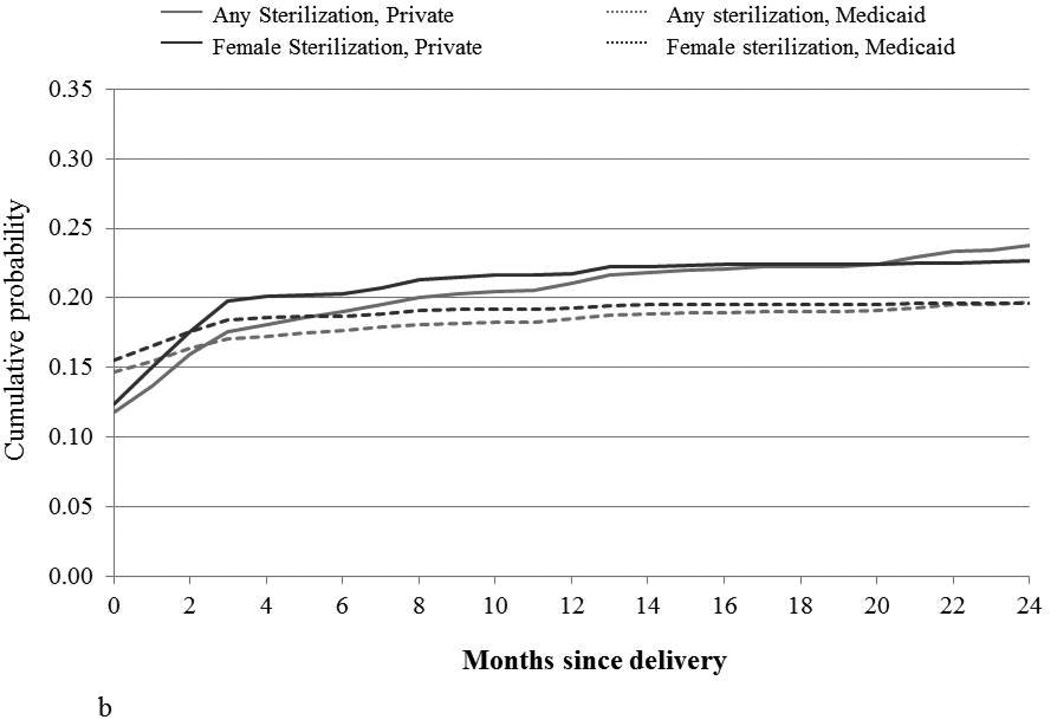

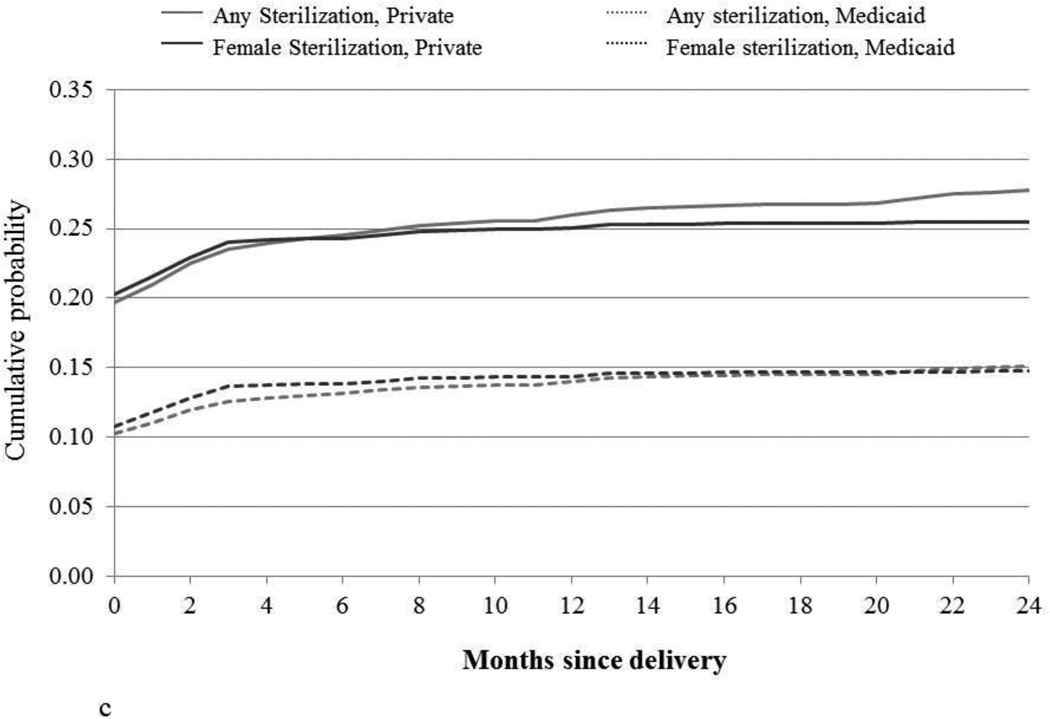

For most groups, the cumulative probability of obtaining a sterilization increases in the first three months following delivery, and then remains relatively stable over the next 21 months (Figure 2). White women with private insurance, for whom the total proportion obtaining any sterilization procedure gradually increases over this period, is the exception (Figure 2a). A higher proportion of African Americans (Figure 2b) and Latinas (Figure 2c) with private insurance rely on sterilization by 24 months postpartum than those who have Medicaid. Regardless of race/ethnicity, the difference in the proportion of women obtaining any sterilization compared to female sterilization is small for women with Medicaid, indicating the low probability of their male partners getting a vasectomy.

Figure 2.

a. Whites

b. African Americans

c. Latinas

Cumulative probability of sterilization within 24 months postpartum, by race/ethnicity and insurancea

Source: NSFG 2006–2010

a. Cumulative probabilities were obtained by summing the estimated postpartum probability and the product of the proportion who did not obtain a postpartum procedure and the interval cumulative incidence at each time point.

4. Discussion

Similar to other studies [2], we found that women’s use of sterilization varies by both race/ethnicity and insurance. However, by conducting an analysis that assessed a woman’s chances of getting sterilized at the time of each birth (rather than based on her total births), and modeling postpartum sterilizations separately from interval procedures, we reach different conclusions about the association between race/ethnicity, insurance and sterilization.

For postpartum procedures, we found a dramatically different racial/ethnic gradient for women whose birth was paid by private insurance as compared to Medicaid, after controlling for age, education and parity. Privately insured African Americans and particularly Latinas had higher probabilities than whites of undergoing postpartum sterilization. The reverse was observed for women with Medicaid-paid deliveries. The latter finding is consistent with smaller local studies that have found low-income minority women are especially likely to encounter bureaucratic barriers to obtaining a postpartum sterilization, such as problems with the Medicaid consent form [7,10,15]. This may be due, in part, to the poor readability of the consent form and disproportionately low levels of health literacy among low-income and racial/ethnic minority groups [16,17]. Low-income, undocumented Latina women may be even more disadvantaged because programs covering the cost of their pregnancy-related care and delivery, such as CHIP perinate and emergency Medicaid, often do not cover postpartum contraception [10].

In the months following delivery, privately insured whites, who had the lowest probability of postpartum female sterilization, had the highest incidence of interval sterilization, whereas Latinas with private insurance had the lowest incidence but the highest probability of a postpartum procedure. However, this inverse relationship was not observed for women with Medicaid-paid deliveries. This may be due to the fact that some low-income women are less able to access interval sterilizations because they lose Medicaid coverage shortly following delivery. Additionally, less than 25% of publicly funded clinics offered tubal sterilization in 2010 [18], making it difficult for low-income women to get an interval procedure at the health centers where they receive reproductive health care.

In addition to systems-level barriers, low-income minority women may be less likely to get a female sterilization due to provider bias. For example, providers may discourage low-income minority women from obtaining a sterilization because they associate these characteristics with a higher likelihood of sterilization regret [6,14,19]. In fact, a qualitative study of women’s decision-making surrounding female sterilization found that low-income African American women more commonly reported their providers as barriers to getting a sterilization than whites [6]. We also found that low-income Latinas were unable to obtain a sterilization because their providers considered them too young or to have too few children [7]. Regardless of the reason, these unfulfilled sterilization requests may result in future unintended pregnancies [11].

Our results also complement findings reported elsewhere that vasectomy varies by race/ethnicity and insurance [4,5]. African Americans and Latinos have a lower prevalence of vasectomy compared with whites, which may be due to attitudes toward contraceptive responsibility, perceptions that vasectomy reduces sexual desire and performance, and lack of social support for the procedure [3,4,20,21]. However, there has been very little research comparing attitudes toward vasectomy across racial/ethnic groups, making it difficult to determine whether this accounts for the observed differences. Moreover, the significantly lower rates of vasectomy among whites with Medicaid compared to privately insured whites, after controlling for education, suggests there may be considerable barriers to accessing vasectomy for low-income men. They are not eligible for Medicaid family planning coverage in many states [22], and less than 10% of US publicly funded family planning clinics offer vasectomy [18]. Finally, while whites with private insurance are more likely to use vasectomy than other groups, it is noteworthy that the cumulative probability of vasectomy rises quite slowly over the 24 months following delivery. This may be the result of deliberation and procrastination about undergoing the procedure [23].

Our study has several limitations. Since we assessed the likelihood of obtaining a sterilization over time following delivery, we had few covariates that we could use to assess differences between groups. In particular, we do not have a measure of a woman and her partner’s future childbearing intentions at the time of birth, which would provide important information about desires to limit childbearing. Additionally, the NSFG does not include information about method preferences, unfulfilled sterilization requests, and insurance status following delivery which would help identify the barriers women face. A second limitation is the size of the NSFG sample. Since the events we are studying are rare, especially for certain sub-groups, the standard errors for our model parameters are quite large. The likelihood ratio tests indicate the effects are important, but we only have a crude sense of how large the differences in rates are across groups. Finally, in a survey like the NSFG, insurance is likely a marker for both economic and marital status; therefore caution is needed in drawing inferences from our results on the impact that increasing coverage would have on narrowing gaps in sterilization method use.

Despite these limitations, our study presents a new and more comprehensive picture of racial/ethnic differences in sterilization in the US that identifies a striking contrast between women whose deliveries were paid by Medicaid versus private insurance. Whereas most previous analyses of the NSFG have pointed to the higher proportions relying on female sterilization among African Americans and Latinas, our analysis shows this association is completely reversed for publicly insured women, even after adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics. The prior studies may be biased by differences in exposure to repeated unintended pregnancies. Lastly, although we can only speculate about the causal mechanisms underlying these differentials, it seems that barriers unique to low-income minority women are an important source of the variation we observe.

Acknowledgments

Funding acknowledgement: Infrastructural support for the study was provided by a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R24 042849) to the Population Research Center, University of Texas at Austin.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Implications

Low-income minorities are less likely to undergo sterilization than low-income whites and privately insured minorities, which may result from barriers to obtaining permanent contraception, and exposes women to unintended pregnancies.

References

- 1.Mosher WD, Jones J. Use of contraception in the United States, 1982–2008. Vital Health Stat. 2010;23 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borrero S, Schwarz EB, Reeves MF, et al. Race, insurance status, and tubal sterilization. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:94–100. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000249604.78234.d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borrero S, Schwarz EB, Reeves MF, et al. Does vasectomy explain the difference in tubal sterilization rates between black and white women? Fertil Steril. 2009;91:1642–1645. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.01.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eisenberg ML, Henderson JT, Amory JK, et al. Racial differences in vasectomy utilization in the United States: Data from the National Survey of Family Growth. Urology. 2009;74:1020–1024. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.06.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson JE, Jamieson DJ, Warner L, et al. Contraceptive sterilization among married adults: National data on who chooses vasectomy and tubal sterilization. Contraception. 2012;85:552–557. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2011.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borrero S, Nikolajski C, Rodriguez KL, et al. "Everything I know I learned from my mother …Or not": Perspectives of African-American and white women on decisions about tubal sterilization. J Gen Int Med. 2009;24:312–319. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0887-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Potter JE, White K, Hopkins K, et al. Frustrated demand for sterilization among low-income Latinas in El Paso, Texas. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2012;44:228–235. doi: 10.1363/4422812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gilliam M, Davis SD, Berlin A, Zite NB. A qualitative study of barriers to postpartum sterilization and women's attitudes toward unfulfilled sterilization requests. Contraception. 2008;77:44–49. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2007.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zite N, Wuellner S, Gilliam M. Barriers to obtaining a desired postpartum tubal sterilization. Contraception. 2006;73:404–407. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2005.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thurman AR, Harvey D, Shain RN. Unfulfilled postpartum sterilization requests. J Reprod Med. 2009;54:467–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thurman AR, Janecek T. One-year follow-up of women with unfulfilled postpartum sterlization requests. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:1071–1077. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181f73eaa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lepkowski JM, Mosher WD, Groves RM, et al. Responsive design, weighting and variance estimation in the 2006–2010 National Survey of Family Growth. Vital Health Stat. 2013;2:1–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bass LE, Warehime MN. Do health insurance and residence pattern the likelihood of tubal sterilization among American women? Pop Res Pol Rev. 2009;28:237–249. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lawrence RE, Rasinski KA, Yoon JD, Curlin FA. Factors influencing physicians' advice about female sterilization in USA: A national survey. Human Reprod. 2011;26:106–111. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deq289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zite N, Wuellner S, Gilliam M. Failure to obtain desired postpartum sterilization: Risk and predictors. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:794–799. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000157208.37923.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zite N, Philipson SJ, Wallace LS. Consent to sterilization section of the Medicaid-Title XIX form: Is it understandable? Contraception. 2007;75:256–260. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2006.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vernon JA, Trujillo A, Rosenbaum S, DeBouno B. Low health literacy: Implications for national health policy. Washington, DC: George Washington School of Public Health and Health Services; 2007. http://sphhs.gwu.edu/departments/healthpolicy/CHPR/downloads/LowHealthLiteracyReport10_4_07.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frost JJ, Gold RB, Frohwirth L, Blades N. Variation in service delivery practices among clinics providing publicly funded family planning services in 2010. New York: Guttmacher Institute; 2012. www.guttmacher.org/pubs/clinic-survey-2010.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hillis SD, Marchbanks PA, Tylor LR, et al. Poststerilization regret: Findings from the United States Collaborative Review of Sterilization. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93:889–895. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00539-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shih G, Turok DK, Parker WJ. Vasectomy: The other (better) form of sterilization. Contraception. 2011;83:310–315. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2010.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shih G, Dube K, Sheinbein M, et al. He's a real man: A qualitative study of the social context of couples' vasectomy decisions among a racially diverse population. American Journal of Men's Health. 2012;7:206–213. doi: 10.1177/1557988312465888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guttmacher Institute. Medicaid family planning eligibility expansions. New York: Guttmacher Institute; 2013. Apr 1, [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mumford SD. The vasectomy decision-making process. Studies Fam Plan. 1983;14:83–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]