INTRODUCTION

The surgical pathology report on cancer resection specimens is fundamental for providing clinicians with the information needed for adequate patient oncology treatment. Since the multi-institutional quality study on pathology reporting of colorectal cancer published by Zarbo in 1992,1 many other studies have shown that the use of checklists or synoptic reporting is superior to traditional narrative (free text) reporting.2–4 Using electronic health records, synoptic histopathology reporting tools can be designed to be very sophisticated with discrete data fields, drop down menus, and automated SNOMED encoding.5 The use of discrete data fields (’atomic data’) means that it is possible to automatically search, extract, and transmit data electronically.4 Despite the apparent benefits of electronic synoptic histopathology reporting, and the successful regional implementation of such a reporting system in Ontario, Canada,5 others have reported that the implementation and use of electronic histopathology reporting is no easy organisational task.6,7 Similar challenges have also been reported regarding the implementation and use of a web-based synoptic reporting tool for cancer surgery.8,9 From a management and organisational perspective, the list of possible causes for project failure with respect to information technology development, implementation and use is long.10 In our opinion, a pro-active understanding and management of key organisational issues is a requirement for successful long-term synoptic histopathology cancer reporting.

INFORMATION SYSTEM CHANGE

Organisational issues

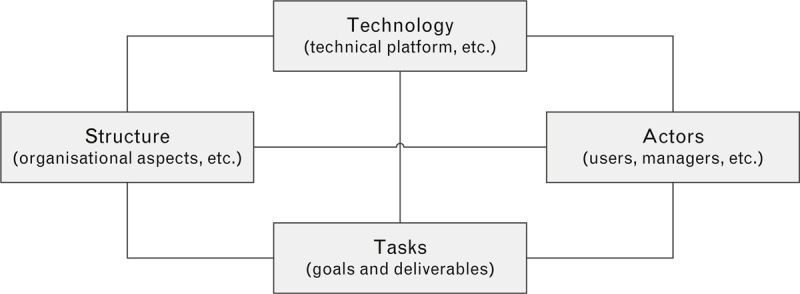

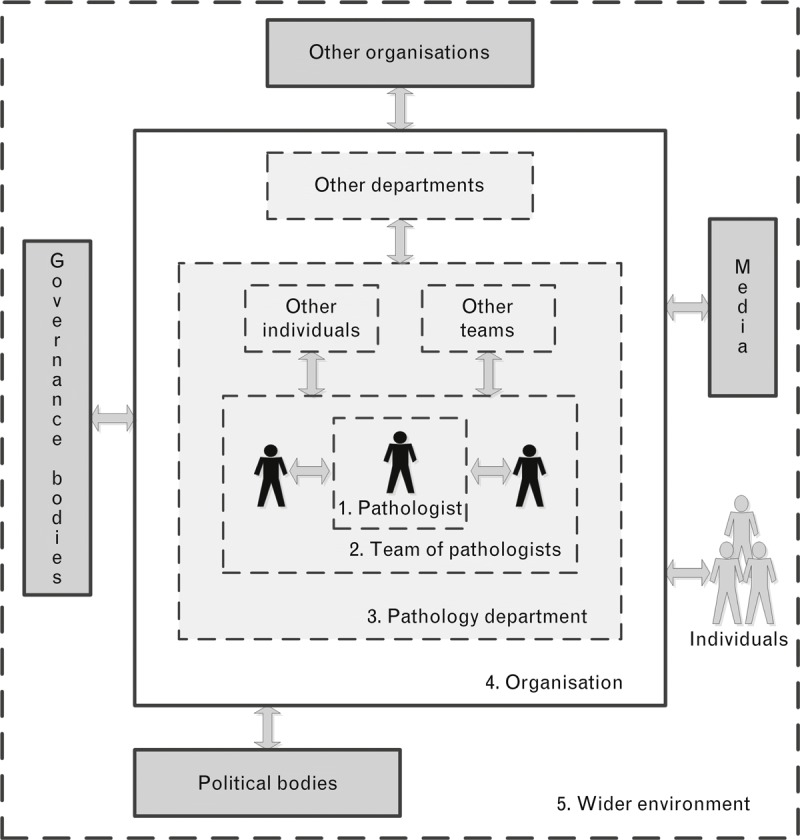

An organisation's information system can be viewed as an interaction between actors, tasks, organisational structure, and technology (Fig. 1). Information system change is the deliberate change to an organisation's technical and organisational subsystems that deal with information.11 The introduction of synoptic reporting within a pathology department can be viewed as such a change. The change process covers initiation, development, implementation, and operation/maintenance of the new elements introduced.11,12 Changes within a department's information technology systems (IT systems) and working routines may be considered a task to be decided by the department itself. However, independent of the formal decision procedure, a number of other organisational units and individuals will be affected by or can influence such a change. The complex relationship between stakeholders potentially affecting, or being affected by changes within a single department is illustrated in Fig. 2. Clinicians will clearly be affected by a move from narrative to synoptic histopathology reporting. The hospital harbouring the pathology department may have a general policy on IT development, and there may even be regional and/or national policies on IT systems that one must adhere to. Similarly, external organisations such as regional or national cancer registries will be affected by, and can affect, a transition from narrative to electronic synoptic reporting. Vendors are also required to develop the IT tools needed. Understanding and managing the needs and interests of all such stakeholders is essential for achieving the organisational changes intended.13 In their study on the implementation and use of a web-based synoptic reporting tool for cancer surgery at two hospitals in Nova Scotia, Canada, Urquhart and co-workers found that implementation and early use of the synoptic tool was affected by many factors external to the individual user. A good understanding of the multilevel organisational environment in both the planning and implementation process was deemed important for project success.8 In a similar study on the implementation of synoptic pathology reporting in four pathology departments in three states in the USA, Hassell and co-workers found that adaption depended both on individual user factors and organisational issues. With respect to the latter, an asymmetric organisational balance between benefits and costs was considered a possible hindrance for implementation. If the pathology laboratories were to carry the financial burden for implementing electronic synoptic reporting but considered the cancer registries the beneficiaries of the new reporting tool, why should the laboratories change their information systems?6 However, even in an environment where the development of an electronic synoptic pathology tool was free of costs for pathology laboratories, local adaption varied greatly. Some laboratories had a user rate above 90%, while other laboratories had not implemented the synoptic tool at all.7

Fig. 1.

Socio-technical model of an organisation's information system(s) (modified from Lyytinen and Newman11).

Fig. 2.

Illustration of the complex relationship between the individual health care worker, health care team, department, organisation, and other stakeholders potentially being influenced by or influencing upon an intended change (modified from Grol and Grimshaw14).

Issues related to individual behaviour

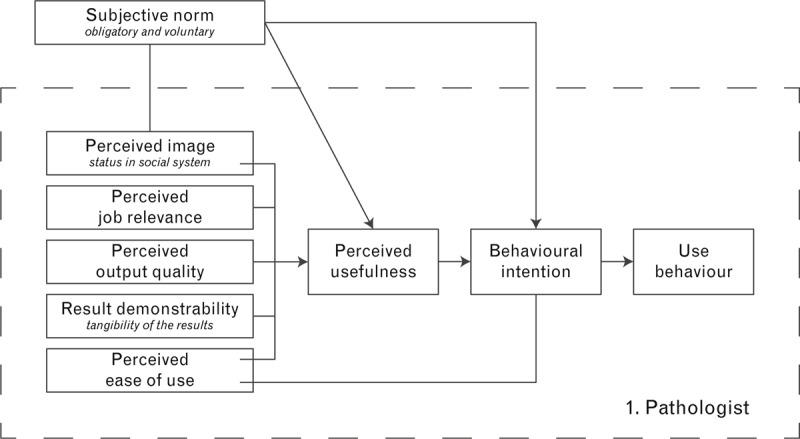

Even after the successful development and implementation of a new IT tool, successful long-term usage is not guaranteed. Health care professionals may not adhere to new guidelines and practices,14 and each individual's adoption and use of new IT solutions is affected by a number of interacting factors (Fig. 3).15 In 1975 Fishbein and Ajzen proposed a model for trying to explain individual behaviour in specific contexts. A central factor in the theory is the individual's intention to perform a given task.16 The original model was later modified to a ‘Technology Acceptance Model’ to try to explain user acceptance (or rejection) of technology.17 This model has again been further developed to try to explain individual behaviour related to adaption and use of information technologies in the workplace.15 Although the model has its limitations and weaknesses,17,18 we find it useful when trying to untangle some of the factors affecting individual behaviour with respect to IT systems and electronic synoptic reporting in a pathology department.

Fig. 3.

Factors affecting each individual health care worker's adoption and use of new information technology solutions (’Technology Acceptance Model’) (modified from Venkatesh and Bala15). All terms are explained with a pathologist's use of electronic synoptic reporting in mind (modified from Venkatesh and Bala15 and Davis19). Subjective Norm: A pathologist's perception of how most people who are important to her think she should or should not use electronic synoptic reporting. The norm can either be perceived as voluntary or compulsory. Perceived Image: The degree to which a pathologist believes that using electronic synoptic reporting would enhance her status in her job related social system. Perceived Job Relevance: The degree to which a pathologist believes that using electronic synoptic reporting would be relevant to her job tasks. Perceived Output Quality: The degree to which a pathologist believes that using electronic synoptic reporting would improve the overall quality of her pathology report. Result Demonstrability: How apparent the benefits of using electronic synoptic reporting are to the reporting pathologist. Perceived Ease of Use: The degree to which a pathologist believes that using electronic synoptic reporting would be free from effort. Perceived Usefulness: The degree to which a pathologist believes that using electronic synoptic reporting would enhance her job performance. Behavioural Intention: The degree to which a pathologist has formulated conscious plans to use (or not use) electronic synoptic reporting.

In settings with individual voluntary use of synoptic reporting, engagement with pathologists is of course essential in all stages of the development and implementation phases of the synoptic tools to be used. However, even in cases where this has been ensured, individual behaviour is difficult to predict. In our experience, perceived (and experienced) output quality and ease of use in combination with a positive subjective norm (as expressed by colleagues in the department) are important factors for a stable, high long-term use of synoptic reporting.2

In settings with compulsory use, the subjective norm will of course favour synoptic use, particularly if combined with a monitoring system. However, evidence from other settings of medical care indicates that such individual performance feedback alone is not sufficient to attain high adherence to a new procedure. Multifaceted strategies for interventions at different levels (individual health care professional, health care team, organisation, etc.) seem to be the way to go.14

LESSONS LEARNED AND THE WAY FORWARD

There is good evidence for stating that electronic synoptic reporting is qualitatively better and more efficient than traditional narrative histopathology reporting. However, there is also good evidence for stating that there are many organisational hurdles to overcome when trying to implement and sustain electronic reporting in pathology laboratories. In our opinion, the quite unique successful implementation of synoptic cancer reporting in the entire province of Ontario, Canada, is due to a combination of a thorough, long-term political and organisational process involving all relevant stakeholders5,20 and a compulsory organisational implementation with active monitoring of actual use.21 One cannot expect such a framework to be present in all settings. However, the models describing organisational and individual change of behaviour presented in this article are relevant for most settings, whether it be one single pathology department or one whole country. Absence of ‘big’ plans should not stop individual pathology departments from trying to achieve the quality improvements attained by electronic synoptic reporting. Sound local organisational planning can be undertaken also with limited resources. A good business plan attuned to the local environment, combined with a long-term strategic vision, can reward even small pathology departments with success.

Conflicts of interest and sources of funding: The authors state that there are no conflicts of interest to disclose. The work was funded by the authors’ own organisations.

References

- 1.Zarbo RJ. Interinstitutional assessment of colorectal carcinoma surgical pathology report adequacy. A College of American Pathologists Q-Probes study of practice patterns from 532 laboratories and 15,940 reports. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1992; 116:1113–1119 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Casati B, Bjugn R. Structured electronic template for histopathology reporting on colorectal carcinoma resections: five-year follow-up shows sustainable long-term quality improvement. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2012; 136:652–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cross SS, Feeley KM, Angel CA. The effect of four interventions on the informational content of histopathology reports of resected colorectal carcinomas. J Clin Pathol 1998; 51:481–482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ellis DW. Surgical pathology reporting at the crossroads: beyond synoptic reporting. Pathology 2011; 43:404–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Srigley JR, McGowan T, Maclean A, et al. Standardized synoptic cancer pathology reporting: a population-based approach. J Surg Oncol 2009; 99:517–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hassell LA, Parwani AV, Weiss L, et al. Challenges and opportunities in the adoption of College of American Pathologists checklists in electronic format: perspectives and experience of Reporting Pathology Protocols Project (RPP2) participant laboratories. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2010; 134:1152–1159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haugland HK, Casati B, Dorum LM, et al. Template reporting matters—a nationwide study on histopathology reporting on colorectal carcinoma resections. Hum Pathol 2011; 42:36–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Urquhart R, Sargeant J, Porterm GA. Factors related to the implementation and use of an innovation in cancer surgery. Curr Oncol 2011; 18:271–279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Urquhart R, Porter GA, Grunfeld E, et al. Exploring the interpersonal-, organization-, and system-level factors that influence the implementation and use of an innovation-synoptic reporting-in cancer care. Implement Sci 2012; 7:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lientz BP, Larssen L. Risk Management for IT Projects: How to Deal With Over 150 Issues and Risks. Burlington, MA:Butterworth-Heinemann; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lyytinen K, Newman M. Explaining information systems change: a punctuated socio-technical change model. Eur J Inform Syst 2008; 17:589–613 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alter S. The work system method for understanding information systems and information systems research. Comm Assoc Inform Syst 2002; 9: Article 6. http://aisel.aisnet.org/cais/vol9/iss1/6 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bryson JM. Strategic planning for public and nonprofit organizations. 4th ed2011; San Francisco:Jossey-Bass, Chapter 4, Clarifying organizational mandates and mission [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grol R, Grimshaw J. From best evidence to best practice: effective implementation of change in patients’ care. Lancet 2003; 362:1225–1230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Venkatesh V, Bala H. Technology Acceptance Model 3 and a research agenda on interventions. Decision Sci 2008; 39:273–315 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Dec 1991; 50:179–211 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chuttur M. Overview of the Technology Acceptance Model: origins, developments and future directions. Sprouts: Working Papers on Information Systems 2009; 9: Article 37. http://sprouts.aisnet.org/9-37/ [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bagozzi RP. The legacy of the Technology Acceptance Model and a proposal for a paradigm shift. J Assoc Inf Syst 2007; 8 (4): Article 12. http://aisel.aisnet.org/jais/vol8/iss4/12 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davis FD. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quart 1989; 13:319–340 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duvalko KM, Sherar M, Sawka C. Creating a system for performance improvement in cancer care: Cancer Care Ontario's clinical governance framework. Cancer Control 2009; 16:293–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cancer Care Ontario. Synoptic Pathology Reporting. 17 May 2012; cited 11 Dec 2013 https://www.cancercare.on.ca/cms/one.aspx?portalId=1377&pageId=48158 [Google Scholar]