Background: Variants of photoreceptor CNG channels are produced by alternative splicing of precursor mRNA.

Results: Inclusion of an optional exon in human CNGA3 transcripts produces channel isoforms with enhanced sensitivity to phosphoinositides via an allosteric mechanism.

Conclusion: Alternative splicing of CNGA3 transcripts controls phosphoinositide regulation of cone CNG channels.

Significance: These findings reveal the functional importance of CNGA3 alternative splicing.

Keywords: Allosteric Regulation, Alternative Splicing, Ion Channels, Phosphoinositides, Photoreceptors

Abstract

Precursor mRNA encoding CNGA3 subunits of cone photoreceptor cyclic nucleotide-gated (CNG) channels undergoes alternative splicing, generating isoforms differing in the N-terminal cytoplasmic region of the protein. In humans, four variants arise from alternative splicing, but the functional significance of these changes has been a persistent mystery. Heterologous expression of the four possible CNGA3 isoforms alone or with CNGB3 subunits did not reveal significant differences in basic channel properties. However, inclusion of optional exon 3, with or without optional exon 5, produced heteromeric CNGA3 + CNGB3 channels exhibiting an ∼2-fold greater shift in K1/2,cGMP after phosphatidylinositol 4,5-biphosphate or phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate application compared with channels lacking the sequence encoded by exon 3. We have previously identified two structural features within CNGA3 that support phosphoinositides (PIPn) regulation of cone CNG channels: N- and C-terminal regulatory modules. Specific mutations within these regions eliminated PIPn sensitivity of CNGA3 + CNGB3 channels. The exon 3 variant enhanced the component of PIPn regulation that depends on the C-terminal region rather than the nearby N-terminal region, consistent with an allosteric effect on PIPn sensitivity because of altered N-C coupling. Alternative splicing of CNGA3 occurs in multiple species, although the exact variants are not conserved across CNGA3 orthologs. Optional exon 3 appears to be unique to humans, even compared with other primates. In parallel, we found that a specific splice variant of canine CNGA3 removes a region of the protein that is necessary for high sensitivity to PIPn. CNGA3 alternative splicing may have evolved, in part, to tune the interactions between cone CNG channels and membrane-bound phosphoinositides.

Introduction

Vertebrate visual transduction requires the activity of cyclic nucleotide-gated (CNG)2 channels. Photoreceptor light responses generate a decrease in cGMP concentration that is converted into an electrical signal (membrane hyperpolarization) by the closure of CNG channels, leading to decreased neurotransmitter release onto second-order cells (1). Photoreceptor CNG channels are members of the large superfamily of cation-selective, “pore-loop” channels (2, 3). They are tetrameric proteins, with each subunit possessing six transmembrane segments, amino-terminal (N) and carboxyl-terminal (C) cytoplasmic domains, a central pore element contributing to the ion conduction pathway, and a cyclic nucleotide-binding domain located in the C-terminal region (4). Channel sensitivity to cGMP is tuned by several pathways, including the action of calcium sensor proteins such as calmodulin (5–9), serine/threonine and tyrosine phosphorylation (10, 11), extracellular matrix metalloproteinases (12, 13), and changes in the concentration of plasma membrane phosphoinositides such as PIP2 and PIP3 (14–16). Adjustments of CNG channel ligand affinity can contribute to photoreceptor adaptation and to paracrine and/or circadian changes in photoreceptor sensitivity (17–19).

The functional diversity of CNG channels is generated via several fundamental mechanisms. First, multiple genes encode CNG channel subunits, and cell type-specific expression of combinations of CNG channel subunits produce heteromeric channel assemblies having properties optimized for the role they play in those cells (4). For example, in cone and rod photoreceptors, the channels are composed CNGA3 and CNGB3 subunits or CNGA1 and CNGB1 subunits, respectively. Second, protein variants of CNGB1 (20, 21) and CNGA3 (22–24) are known to arise from alternative splicing of precursor mRNAs. Alternative splicing of primary transcripts is a prevalent mechanism for generating proteome complexity from a limited number of genes and is thought to have particular importance in the central nervous system (25). For CNGB1, a short variant (CNGB1b) is expressed in olfactory receptor neurons where it forms part of the olfactory CNG channel, whereas a long variant (CNGB1a) is expressed in rod photoreceptor cells. In addition, the CNGB1 transcriptional unit generates splice variants encoding soluble GARP1 and GARP2 proteins, short isoforms lacking the channel-forming domain but serving structural and regulatory functions. Soluble GARP proteins and the GARP region of CNGB1a are thought to interact with proteins in the rim of outer segment disc membranes, including phosphodiesterase (26) and peripherin (27). Furthermore, soluble GARP2 and the GARP region intrinsic to CNGB1a can act as gating inhibitors of the rod CNG channel (28). For human CNGA3, four protein isoforms can arise from alternative splicing because of different exon combinations within the 5′ region of the mRNA encoding the N-terminal cytoplasmic domain of the subunit (24, 29). Alternative splicing of CNGA3 occurs in multiple species with many species-specific variants, including, in some cases, unique alternative cassette exons (22–24). Unlike CNGB1, the functional importance of CNGA3 alternative splicing has remained an unresolved issue.

For many CNG channel subunits, the cytoplasmic N-terminal region can critically influence channel regulation by second messengers such as Ca2+/CaM and phosphoinositides (9, 15, 16, 30–32). Previous studies in our laboratory have revealed two PIPn regulation modules within CNGA3 subunits. One is located within the N-terminal region, overlapping with a functionally silent Ca2+-CaM binding site, and the other is located within the C-terminal leucine zipper domain distal to the cyclic nucleotide-binding domain (16). Both of these PIPn regulation modules are characterized by clusters of positively charged amino acids. Because alternative splicing produces changes in the N-terminal region of CNGA3, we hypothesized that these CNGA3 variants would exhibit altered channel sensitivity to regulation by PIPn. Here we show that heteromeric channels formed with CNGA3 subunits having an optional e3 exon-encoded sequence exhibit enhanced sensitivity to regulation by phosphoinositides. Surprisingly, this enhancement of regulation depended on the PIPn regulation module located in the C-terminal region of CNGA3, suggesting that changes in interdomain N-C coupling may influence channel gating and regulation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Channel Subunit cDNA and Mutagenesis

Human CNGA3 was a gift from Dr. K.-W. Yau (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD). Subunit cDNAs were subcloned into pGEMHE, where they are flanked by the Xenopus β-globin gene 5′- and 3′ UTRs for heterologous expression in Xenopus oocytes. Point mutations were generated by overlapping PCR (cassette) mutagenesis. All mutations were confirmed by fluorescence-based DNA sequencing.

Quantitative PCR

Human eyes were obtained from donors through SightLife with the approval of the Institutional Review Board at Washington State University. The eyes were immersed in RNAlater immediately after extraction. The retinas were subsequently isolated for RNA extraction. Retinal tissues, including the macula, were homogenized, and RNA extraction was performed (RNeasy mini kit, Qiagen, Valencia, CA), followed by on-column DNase treatment. The quantity of RNA was determined spectrophotometrically by the A260/A280 ratio (Nanodrop 1000, Thermo-Scientific, Wilmington, DE).

Standard PCR was performed on all four variants of CNGA3 plasmid cDNA and on human retinal cDNA using JumpStart REDTaq ReadyMix (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). The primers used to detect the presence or absence of specific exons were as follows. For inclusion of exon 3, ATC GCC AGG TTT GGA AGA AT (forward) and CAT CCT CAG CAC ACC ACT GT (reverse); for skipping of exon 3, GAG ACC AGA GGA CTG GCT (forward) and GGC GCG ACA GCC TGG CGA (reverse); for inclusion of exon 5, AGG GAC CGG ACT CTT TTC CT (forward) and GGG CCA GGC GCT TCT CCC TC (reverse); for skipping of exon 5, GCA GAC AGA GGG AGA AGG AA (forward) and AAG ACA GGC AGG GCG ATG (reverse); and for constitutive exon 8, GTC CTG TAT GTC TTG GAT GTG C (forward) and CGT CTT GTA ATG CTG CCA CA (reverse). All primers were designed using Primer Express 3.0 (Applied Biosystems). The following conditions were used: initial denaturation, 94 °C (2 min); denaturation, 94 °C (30 s); annealing, 66 °C (30 s); extension, 72° (2 min); and final extension, 72 °C (5 min). 21 cycles for plasmid cDNAs and 39 cycles for human retinal cDNA were used.

Expression levels for inclusion of alternative exons in human retinal tissue were quantified by RT quantitative PCR. For each human retinal sample, first-strand cDNA was synthesized with 500 ng of total RNA, 100 ng of random primers (Invitrogen), and 50 units of reverse transcriptase (Superscript II, Invitrogen) according to the protocol of the manufacturer. RT quantitative PCR was performed using an iCycler version 2.039 thermocycler (Bio-Rad) according to the protocol of the manufacturer. The specificity of the reactions was verified via melt curve analysis. Three biological replicates and three technical replicates were performed for each sample. cDNA corresponding to constitutive exon 8 was used as an endogenous control. Before statistical analysis, Ct values were averaged across technical replicates.

Immunohistochemistry

Human retinal sections were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). Polyclonal goat anti-CNGA3 (1:500) was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (catalog no. sc-21927, Dallas, TX). Rabbit polyclonal antibody specific to the exon 3-encoded sequence (1:300) was generated using the following peptide antigen: RFGRIQKKSQPEKV-[C] (GenScript, Piscataway, NJ). Fluorescein isothiocyanate-coupled peanut agglutinin (1:1000), which labels cone outer segments (33), was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Four slides, each containing two human retinal sections, were stained. The images were captured using a Leica TCS SP8 X point-scanning confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL).

PIP2- and PIP3-binding Assays

Purified GST fusion proteins were used for in vitro PIP2- and PIP3-binding assays in buffer containing 10 mm HEPES (pH 7.4), 50 mm NaCl, 2 mm EDTA, 0.25% v/v Triton X-100, and 0.25% v/v Nonidet P-40. PIP2- and PIP3-agarose beads were from Echelon Biosciences (Salt Lake City, UT). Briefly, 40 μl of a 50% slurry of PIPn or control agarose beads and purified protein (2 μg/ml) was incubated in 0.5 ml of binding buffer for 2 h at 4 °C with rocking. Beads were pelleted gently and washed five times with excess binding buffer. PIPn-interacting proteins were eluted with 1× NuPAGE sample buffer (Invitrogen). Protein samples were then separated under reducing conditions in 4–12% BisTris gels and blotted onto nitrocellulose by using the NuPAGE transfer buffer system (Invitrogen). Blotted proteins were detected overnight using B-14 anti-GST monoclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at a dilution of 1:2000 in 1% milk, 500 mm NaCl, 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), and 0.05% Tween 20. Horseradish peroxide-conjugated anti-mouse IgG secondary antibodies were used subsequently for 1 h. Chemiluminescent detection was performed using the Super-Signal West Dura extended duration detection kit (Pierce).

Electrophysiology

For expression in Xenopus laevis oocytes, channel subunit cDNAs were linearized by digestion with NheI or SphI, and cRNA was synthesized in vitro using an upstream T-7 promoter (mMessage mMachine, Ambion). Stage IV oocytes were isolated as described previously (34). The animal use protocols were consistent with the recommendations of the American Veterinary Medical Association and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Washington State University. Approximately 20 ng of channel RNA was microinjected per oocyte. To efficiently generate heteromeric channels, an excess of CNGB3 relative to the CNGA3 subunit RNA was injected (35). 2–7 days after microinjection of in vitro-transcribed cRNA into oocytes, patch clamp experiments were performed using an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA) and pulse acquisition software (HEKA, Bellmore, NY) in the inside-out configuration. Initial pipette resistances were 0.30–0.80 MΩ. Intracellular (bath) and extracellular (pipette) solutions contained 130 mm NaCl, 0.2 mm EDTA, and 3 mm HEPES (pH 7.2). Cyclic nucleotides were added to the intracellular solution as needed. Intracellular solutions were changed using an RSC-160 rapid solution changer (Molecular Kinetics, Indianapolis, IN). Currents in the absence of cyclic nucleotide were subtracted. For channel activation by cGMP, dose-response data were fitted using the Hill equation, I / Imax = [cGMP]h / (K1/2h + [cGMP]h), where I is the current amplitude at +80 mV, Imax is the maximum current elicited by a saturating concentration of ligand, [cGMP] is the cGMP concentration, K1/2 is the concentration of cGMP producing half-maximal current, and h is the Hill coefficient. To confirm the formation of heteromeric CNG channels, we tested the expressed channels for block by 25 μm l-cis-diltiazem (Sigma-Aldrich) in the intracellular solution in the presence of 1 mm cGMP at +80 mV. For Ca2+-CaM experiments, 250 nm CaM was used in intracellular solution containing 130 mm NaCl, 3 mm HEPES (pH 7.2), 2 mm nitrilotriacetic acid, and 704 mm CaCl2 for a final buffered free [Ca2+] of 50 μm. Niflumic acid (500 μm) was added to the pipette solution for Ca2+-CaM experiments. Recordings were made at 20–22 °C. PIPn solutions were prepared with FVPP (a phosphatase inhibitor mixture) (36) containing 5 mm sodium fluoride, 0.1 mm sodium orthovanadate, and 10 mm sodium pyrophosphate, as described previously (37). PIP3 and PIP2 analogues were phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-triphosphate, dipalmitoyl, sodium salt and phosphatidylinositol 4,5-biphosphate, dipalmitoyl, and sodium salt (Matreya LLC, Pleasant Gap, PA). PIPn solutions were applied to the cytoplasmic face of membrane patches approximately 5–10 min or more after patch excision. Data parameters were expressed as mean ± S.E. of n experiments unless indicated otherwise. Statistical significance was determined by using Student's t test or Mann-Whitney U test. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

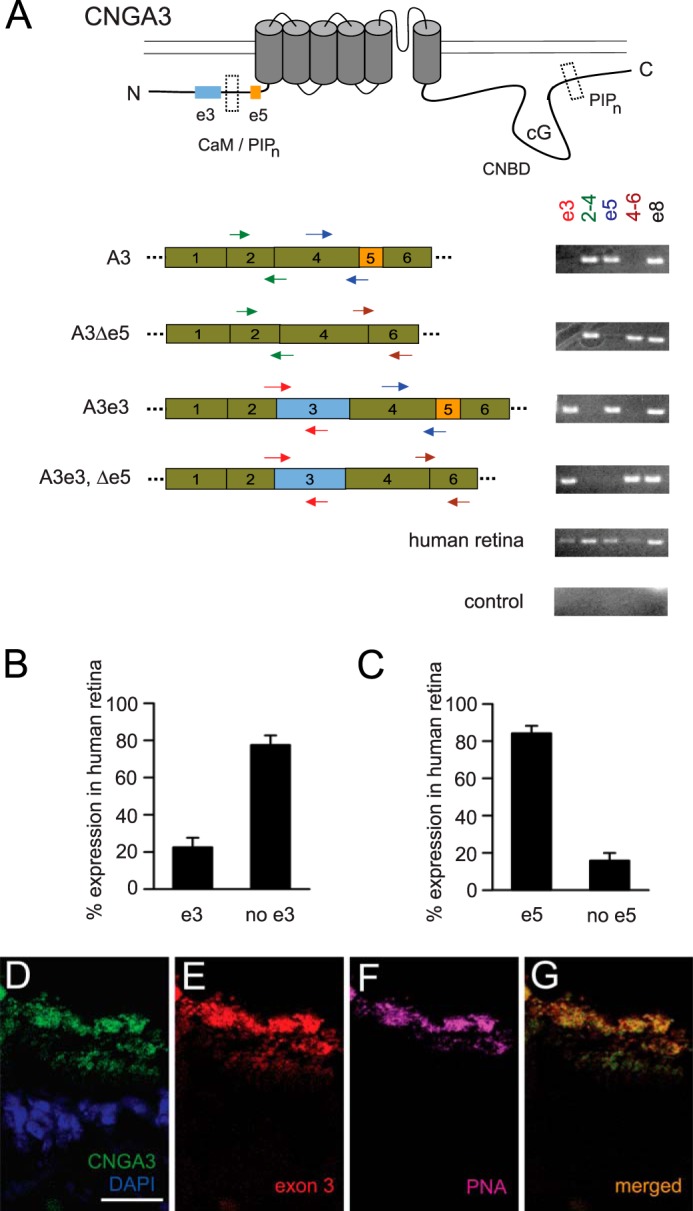

Alternative Splicing of CNGA3 Generates Channel Isoforms with Similar Fundamental Properties

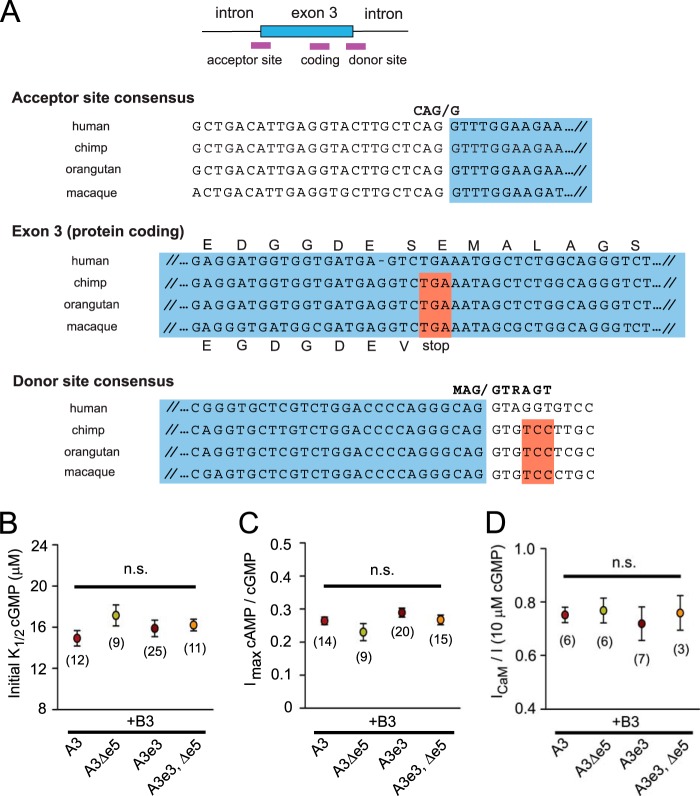

Four variants of human CNGA3 transcripts are generated by alternative splicing involving binary exclusion or inclusion of optional cassette exons 3 and 5 (24, 29). To determine the expression levels for these variants in the human retina, we designed variant-specific primers to detect the presence or absence of the optional exons (Fig. 1A). To confirm their specificity, we first tested these primers on plasmid cDNA representing the CNGA3 splice variants. RT quantitative PCR was used to assess the expression level of the variant CNGA3 transcripts in human retina. We found that ∼25% of retinal CNGA3 transcripts contained exon 3, whereas more than 80% contained exon 5 (Fig. 1, B and C). Furthermore, we performed immunohistochemical studies using human retinal sections and a specific antibody targeting the exon 3-encoded sequence (Fig. 1, D--G). Fluorescein-coupled peanut agglutinin was used to label cone photoreceptor outer segments, the predominant location for mature cone CNG channels. We found that exon 3-containing isoforms were present in the retina and located within the outer segment of cone photoreceptors, similar to the distribution of total CNGA3 subunits detected using an antibody directed against an epitope within the C-terminal region (encoded by a constitutive exon). The observed overlap between the general CNGA3 signal and the e3-specific signal was consistent with the presence of e3 variant CNGA3 subunits in most cone photoreceptor subtypes. It is noteworthy that exon 3 appears to be unique to humans, even compared with other primates, where the related genomic sequence is not an open reading frame and the 5′ (donor) splice site does not match the consensus sequence (Fig. 2A).

FIGURE 1.

CNGA3 splice variant-specific primers detect the relative abundance of optional exon-containing retinal transcripts. A, schematic of a CNGA3 subunit (top panel), with regions encoded by optional exon 3 and exon 5 as well as PIPn and calmodulin regulation modules (dashed box) highlighted. Locations of PCR primer pairs for detecting inclusion or exclusion of optional exon 3 or exon 5 (note primers crossing exon boundaries) are shown below. Representative PCR products generated using primers sets are shown on the left for plasmid cDNA representing the four CNGA3 splice variants (NM_001298, NM_001079878, AK_131300, and XM_006712243) (24, 29) and for cDNA generated from human retinal mRNA. Control, no template negative control; CNBD, cyclic nucleotide binding domain. B and C, percentage expression levels in human retinal tissue for alternative exons 3 and 5, respectively, were determined by quantitative real-time RT-PCR (n = 3 biological replicates with 2–3 technical replicates each). The primers used are shown in A. D–G, representative images of stained human retinal sections demonstrating the presence of CNGA3-e3 isoforms in cone outer segments. D, expression of total CNGA3 protein (green), detected using a general anti-CNGA3 antibody, with DAPI counterstaining for nuclei (blue). E, expression of the CNGA3 e3 isoform, detected using an antibody specific to the e3-encoded protein sequence (red). F, staining using the cone-specific marker peanut agglutinin (PNA), which labels cone outer segments (purple). G, merged image (green and red). Scale bar = 25 μm (D–G).

FIGURE 2.

Basic gating properties and Ca2+-calmodulin sensitivity of heteromeric CNGA3+CNGB3 channels were not altered by alternative splicing of CNGA3. A, alignment of genomic sequences for parts of human optional exon 3 and adjacent intronic sequence compared with corresponding genomic sequences of three other primates. Only human exon 3 presents an open reading frame and an intact consensus 5′ (donor) splice site. Only scant homology was apparent between human exon 3 and genomic sequences from mouse, rat, dog, cow, pig, opossum, platypus, chicken, zebrafish, Xenopus, and fly. Some homology was present with horse, dog, and giant panda sequences, but splice junctions were not intact (data not shown). B, initial apparent affinity for cGMP (K1/2,cGMP) was not significantly different for the four human CNGA3 variants coexpressed with CNGB3 in Xenopus oocytes. n.s., not significantly different. C, relative cAMP efficacy compared with cGMP was not affected by alternative splicing of CNGA3 transcripts. Imax was measured in 10 mm cAMP and 1 mm cGMP. D, Ca2+-CaM inhibition of CNGA3+CNGB3 channels was unaffected by alternative splicing of CNGA3 transcripts. The value below each symbol indicates the number of experiments. Data are mean ± S.E.

Next, we expressed the four CNGA3 isoforms individually with CNGB3 subunits in Xenopus oocytes for functional analysis of the splice variants. We designated the CNGA3 isoform that lacked exon 3 but contained exon 5 as the reference CNGA3 isoform because this isoform was the first cloned and characterized (38). It is reported to be the most abundant isoform in the human retina and largely absent from other tissues (29). We found that cGMP- or cAMP-dependent activation of heteromeric CNGA3 + CNGB3 channels was not altered significantly by alternative splicing (Fig. 2, B and C). We evaluated channel activation by cGMP by measuring the concentration of cGMP that produced the half-maximal current (K1/2,cGMP), whereas we used the ratio of maximal currents elicited by saturating concentrations of cAMP and cGMP (Imax cAMP/cGMP) to assess the efficacy of the partial agonist cAMP. For cone CNG channels, cGMP is nearly a full agonist, whereas cAMP is a partial agonist. For heteromeric channels containing the reference CNGA3, the K1/2,cGMP was 14.9 ± 0.8 μm (n = 12), and the Imax cAMP/cGMP was 0.26 ± 0.01 (n = 14). We found that neither the apparent cGMP affinity (K1/2,cGMP) nor the relative cAMP efficacy (Imax cAMP/cGMP) of heteromeric CNG channels were altered significantly by inclusion or exclusion of the optional exons (Fig. 2, B and C, p > 0.05 compared with channels containing the reference CNGA3). Furthermore, because there is a functionally silent Ca2+-CaM binding site within the N-terminal region of CNGA3 (located within the sequence encoded by constitutive exon 4) (30), we examined the effect of alternative splicing on the Ca2+-CaM sensitivity of heteromeric and homomeric channels. No differences in the Ca2+-CaM sensitivity of heteromeric channels were observed with the CNGA3 splice variants (Fig. 2D). Application of 250 nm CaM in the presence of 50 μm free Ca2+ moderately attenuated the current induced by 10 μm cGMP to a similar extent for channels containing all four CNGA3 isoforms (∼25% suppression). In addition, similar to reference homomeric CNGA3 channels (30), CNGA3e3-only channels remained insensitive to CaM. The current induced by 10 μm cGMP was not reduced significantly by CaM (the ICaM/I ratio was 0.98 ± 0.03, n = 6). Together, these results indicate that alternative splicing of human CNGA3 does not modify the fundamental gating properties of the channel nor sensitivity to regulation by calmodulin. Furthermore, these results show that CNGA3 alternative splicing does not alter heteromeric channel assembly.

Alternative Splicing Tunes the Phosphoinositide Sensitivity of Heteromeric Cone CNG Channels

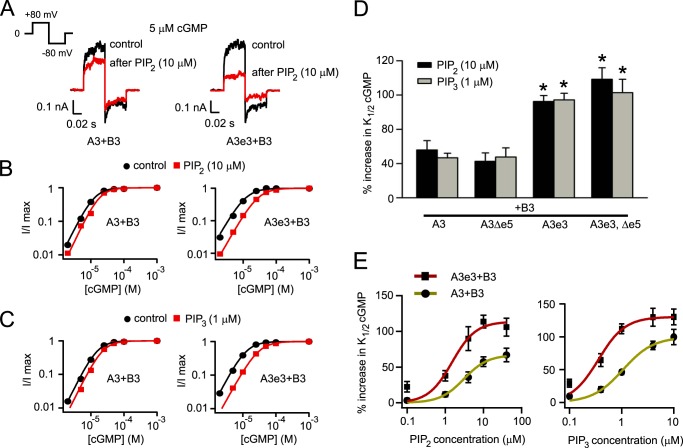

We tested the hypothesis that optional exon-encoded sequences might alter the phosphoinositide sensitivity of heteromeric CNGA3 + CNGB3 channels by applying diC8-PIP2 or diC8-PIP3 to the cytoplasmic face of the inside-out patches. Phosphoinositides were applied to patches approximately 5–10 min (or more) after patch excision. We have shown previously that application of these diC8-PIPn analogs produced similar effects on cone CNG channel gating as natural phosphoinositides (16). Also, manipulations of endogenous phosphoinositides have been shown to alter the ligand sensitivity of expressed cone CNG channels (37). We measured currents elicited by a subsaturating concentration of cGMP (5 μm), which approximates the intracellular cGMP concentration within vertebrate photoreceptors in the dark (17, 39). 10 μm PIP2 suppressed the currents to a greater extent for channels formed with the optional exon 3 variant of CNGA3 (A3e3+B3) compared with channels comprised of the reference CNGA3 with CNGB3 (A3+B3) (Fig. 3A). For reference A3+B3 channels, the cGMP dose-response curve was shifted about 1.5-fold to higher concentrations of cGMP after PIPn application (Fig. 3, B and C). K1/2,cGMP increased from 14.3 ± 0.8 μm (n = 14) to 20.6 ± 1.6 μm (n = 8) after 1 μm diC8-PIP3 (PIP3) or to 22.1 ± 1.7 μm (n = 6) after 10 μm diC8-PIP2 (PIP2). Variant A3e3+B3 channels exhibited enhanced sensitivity to PIPn (Fig. 3, B and C). There was an ∼2-fold greater shift in the cGMP dose-response relationship (p < 0.001 compared with reference channels). For A3e3+B3 channels, K1/2,cGMP was increased from 14.5 ± 0.9 μm (n = 16) to 27.1 ± 1.3 μm (n = 10) after 1 μm PIP3 or to 32.7 ± 2.3 μm (n = 6) after 10 μm PIP2. A similar enhancement of sensitivity to regulation by natural PIP2 was observed for A3e3+B3 channels. K1/2,cGMP was increased from 12.5 ± 0.9 μm to 29.2 ± 2.1 μm (n = 4) after application of 10 μm natural PIP2. Several minutes after patch excision, the contribution of endogenous PIPn to channel regulation is thought to be negligible under control conditions (37). Application of 25 μg/ml poly-lysine to control patches expressing A3+B3 channels (5–10 min after patch excision) did not increase apparent cGMP affinity. K1/2,cGMP was 12.7 ± 0.7 μm before and 15.7 ± 1.2 μm after poly-lysine (p = 0.074. n = 4). In contrast to the exon 3 variant, the presence or absence of exon 5-encoded sequence did not influence PIPn regulation of cone CNG channels (Fig. 3D). Fig. 3E shows the concentration-response relationship for the percent increase in K1/2,cGMP induced by different concentrations of PIP2 and PIP3 for heteromeric A3e3+B3 channels compared with A3+B3 channels. These results indicate that incorporation of the exon 3-encoded sequence significantly increased both the affinity and efficacy of PIP2 and PIP3 for inhibition of cGMP-dependent gating of A3+B3 channels.

FIGURE 3.

CNGA3 optional exon 3 inclusion produces heteromeric channels with enhanced PIP2 and PIP3 sensitivity. A, representative currents elicited by 5 μm cGMP (an approximately physiological ligand concentration) using the voltage protocol shown on the left, before (black) and after (red) 10 μm PIP2, for heteromeric channels composed of B3 plus reference A3 or variant A3e3 expressed in Xenopus oocytes. The formation of heteromeric channels was confirmed by sensitivity to block by 25 μm l-cis-diltiazem. B, representative cGMP dose-response relationships for currents elicited at +80 mV before (black) and after (red) 10 μm diC8-PIP2 application for activation of heteromeric A3+B3 channels, fitted using the Hill equation. Inclusion of exon e3 enhanced the rightward shift of K1/2,cGMP after PIP2. The Hill parameters were as follows. For A3+B3 channels, before PIP2, K1/2,cGMP = 12.9 μm, h = 2; after PIP2, K1/2,cGMP = 18.3 μm, h = 2.1. For A3e3+B3 channels, before PIP2, K1/2 = 11.9 μm, h = 1.8; after PIP2, K1/2 = 28.0 μm, h = 1.8. C, representative cGMP dose-response relationships for currents elicited at +80 mV before (black) and after (red) 1 μm diC8-PIP3 application for activation of heteromeric A3+B3 channels, fitted using the Hill equation. The Hill parameters were as follows. For A3+B3 channels, before PIP3, K1/2,cGMP = 15.8 μm, h = 2; after PIP3, K1/2,cGMP = 22.9 μm, h = 2. For A3e3+B3 channels, before PIP3, K1/2 = 12.5 μm, h = 1.9; after PIP3, K1/2 = 29.6 μm, h = 1.8. D, summary of the enhancement of percent increase in K1/2 cGMP after 10 μm diC8-PIP2 or 1 μm diC8-PIP3 with inclusion of exon e3 but not e5. Error bars denote the mean ± S.E. (n = 6–16). *, p < 0.05 compared with channels containing the reference CNGA3 subunit, which includes exon e5. E, DiC8-PIP2 and diC8-PIP3 concentration-response relationships for the percentage of increase in K1/2,cGMP for activation of heteromeric A3+B3 or A3e3+B3 channels. Continuous curves represent fits using the Hill equation. The Hill parameters are as follows. For PIP2, K1/2 = 3.09 μm, h = 1.4 without e3 and K1/2 = 1.51 μm, h = 1.4 with e3. For PIP3, K1/2 = 1.06 μm, h = 1.5 without e3 and K1/2 = 0.36 μm, h = 1.7 with e3. Error bars indicate the mean ± S.E. of four independent experiments.

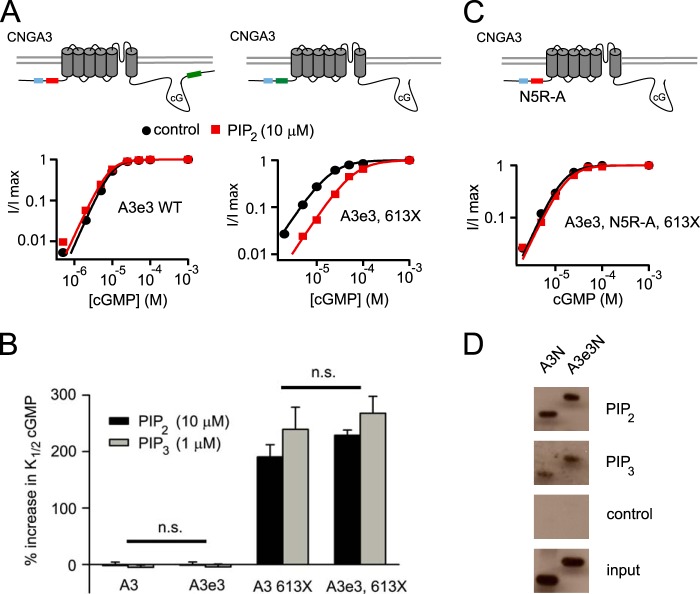

The Exon 3-encoded Sequence Does Not Enhance PIPn Regulation of Homomeric CNGA3-only Channels

Homomeric CNGA3 channels are not sensitive to PIPn-dependent changes in apparent cGMP affinity but, instead, show an ∼2.5-fold increase in relative cAMP efficacy (Imax cAMP/cGMP) (16). Truncation of the C-terminal region (613X) distal to the cyclic nucleotide-binding domain, mutations disrupting the structure of the C-terminal leucine zipper domain, or charge neutralizations within the C-terminal PIPn regulation module all eliminated the increase in Imax cAMP/cGMP produced by PIPn for CNGA3-only channels (16, 40). We expressed the CNGA3e3 subunit without CNGB3 and found that the increase in Imax cAMP/cGMP after PIPn application for the homomeric channels was similar to the reference CNGA3-only channels. The fold increase in Imax cAMP/cGMP was 2.6 ± 0.3 (n = 4) after 1 μm PIP3 or 2.2 ± 0.2 (n = 4) after 10 μm PIP2. In addition, homomeric CNGA3e3 channels remained insensitive to PIPn regarding apparent cGMP affinity (Fig. 4A). We have shown previously that truncation of CNGA3 at amino acid 613 (CNGA3 613X) unmasks the N-terminal component of PIPn regulation for homomeric channels, producing a more than 3-fold increase in K1/2,cGMP after PIPn application (16). However, incorporation of the region encoded by exon 3 did not significantly change the PIPn-induced increase in K1/2,cGMP for 613X channels (Fig. 4, A and B). K1/2,cGMP was increased from 16.3 ± 1.0 μm (n = 11) to 64.7 ± 3.6 μm (n = 6) after 1 μm PIP3 or to 53.5 ± 5.0 μm (n = 5) after 10 μm PIP2 for A3e3–613X channels. These results suggest that the potentiation of PIPn sensitivity mediated by the exon 3-encoded sequence in CNGA3 requires assembly with CNGB3 subunits and/or structural elements within the distal C-terminal domain of CNGA3.

FIGURE 4.

CNGA3 exon 3 variant does not enhance PIPn regulation of homomeric CNGA3 channels nor in vitro PIPn binding to the N-terminal fragment. A, representative cGMP dose-response relationships before and after diC8-PIP2 (red) for activation of A3e3 wild-type or A3e3–613X channels. Red and green boxes indicate silent and active PIPn interaction sites, respectively. Blue box, region encoded by alternative exon 3. cG, cGMP. B, summary illustrating the impact of inclusion of exon 3 on the percentage of increase in K1/2,cGMP after diC8-PIP2 or diC8-PIP3 for homomeric wild-type A3 and A3–613X channels. Exon 3 did not produce a statistically significant effect on PIPn sensitivity for homomeric A3 channels (n = 4–6). n.s., not significant. C, representative dose-response relationships for activation of A3e3, N5R-A, and 613X channels by cGMP. A red box indicates silencing of the N-terminal component for PIPn regulation of cone CNG channels by mutation (N5R-A: R72A, R75A, R81A, R82A, and R86A). D, in vitro pulldown assay using PIP2, PIP3, or control agarose beads combined with GST fusion proteins representing the N-terminal regions of CNGA3 either with or without the region encoded by exon 3.

Next, we sought to determine whether the exon 3-encoded sequence was sufficient to support PIPn regulation of homomeric CNGA3 channels. To test this, we neutralized the positively charged arginines within the sequence encoded by constitutive exon 4 (R72A, R75A, R81A, R82A, and R86A in reference CNGA3; N5R-A). These changes have been shown previously to abolish the PIPn sensitivity of CNGA3–613X channels (16). We found that the PIPn-induced increase in K1/2,cGMP of CNGA3e3–613X channels was similarly eliminated by N5R-A mutations (Fig. 4 C). This result indicated that the region encoded by alternative exon 3 alone was not sufficient to confer phosphoinositide sensitivity to homomeric CNGA3 channels. Furthermore, we carried out in vitro PIPn-binding assays using PIP3- and PIP2-linked agarose beads together with GST-tagged N-terminal fragments of CNGA3 with or without the region encoded by exon 3. We found that the e3 isoform did not alter in vitro binding of the N-terminal fragment to PIP2 or PIP3 (Fig. 4D).

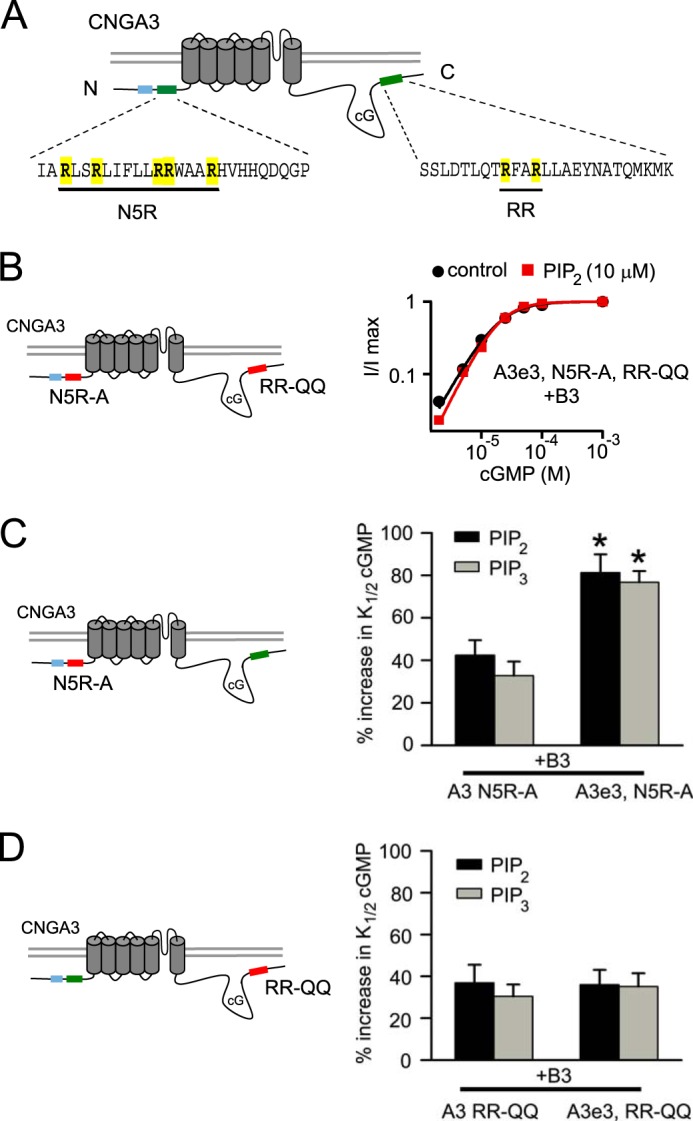

Potentiation of PIPn Sensitivity by the e3 Variant Depends on the C-terminal PIPn Regulation Module of CNGA3

PIPn regulation of heteromeric CNGA3 +CNGB3 channels is supported by two regulatory modules (N and C) (Fig. 5A) having additive effects on K1/2,cGMP (16). We silenced both N- (N5R-A) and C-terminal (R643Q and R646Q in reference CNGA3, RR-QQ) PIPn regulation modules in CNGA3e3. These mutations together have been shown previously to abolish the PIPn sensitivity of heteromeric CNGA3+CNGB3 channels (16). We found that channels made up of CNGA3e3-N5R-A, RR-QQ + CNGB3 subunits were no longer sensitive to PIPn (Fig. 5B). The percentage change in K1/2,cGMP was 6.3 ± 11% (n = 4) after 1 μm PIP3 and −2.5 ± 5.5% (n = 6) after 10 μm PIP2. This observation is consistent with the idea that the e3-encoded sequence is not sufficient to confer PIPn sensitivity to heteromeric channels. The next question we addressed was whether the enhancement of PIPn sensitivity by the e3 isoform depends on the N-, C-, or both N- and C-terminal regulatory modules. Thus, we ablated either the N-terminal or C-terminal PIPn regulation sites in CNGA3 combined with inclusion or exclusion of the region encoded by exon 3. We found that the e3 isoform still enhanced the PIPn-induced increase in K1/2,cGMP for CNGA3+CNGB3 channels when the C-terminal PIPn-regulation module was intact but the N-terminal site was silenced (N5R-A) (Fig. 5C, p < 0.05 for both PIP2 and PIP3). In contrast, the e3 variant was not able to potentiate the PIPn-induced increase in K1/2,cGMP for CNGA3+CNGB3 channels when the N-terminal PIPn regulation module was intact but the C-terminal PIPn regulation module was silenced (RR-QQ) (Fig. 5D, p = 0.941 for PIP2 and p = 0.610 for PIP3). For all mutant CNGA3 subunits described here, the formation of functional heteromeric channels was confirmed by sensitivity to block by l-cis-diltiazem and by enhanced relative cAMP efficacy compared with homomeric channels. Therefore, these data indicate that, even though the exon 3-encoded sequence is in close proximity to the N-terminal PIPn regulation module, the CNGA3e3 variant enhances phosphoinositide sensitivity by influencing the C-terminal PIPn regulation module.

FIGURE 5.

Enhancement of PIPn sensitivity by the CNGA3 e3 isoform depends on the C-terminal structural component of PIPn regulation. A, schematic illustrating the PIPn regulation modules within the N- and C-terminal regions of CNGA3, characterized by positively charged arginines (16). B, representative dose-response relationship for activation of heteromeric CNGA3 N5R-A, RR-QQ + B3 channels by cGMP. In this scenario, both the N-terminal (N5R-A) and C-terminal (RR-QQ: R643Q and R646Q) structural components underlying PIPn regulation were silenced by mutation. cG, cGMP. C, summary showing that the enhancement of PIP2 (10 μm) or PIP3 (1 μm) sensitivity by the e3 isoform was not prevented by mutation of the N-terminal PIPn regulation module (N5R-A). The green and red boxes indicate that the designated PIPn regulation module was active or silenced, respectively. Error bars denote the mean ± S.E. (n = 4 - 7). *, p < 0.05 compared with reference heteromeric channels. D, summary showing that mutation of residues critical for the C-terminal PIPn regulation module (RR-QQ) eliminated the enhancement of PIP2 or PIP3 sensitivity in K1/2,cGMP conferred by the e3 isoform. No significant differences were observed.

Control of PIPn Sensitivity by Alternative Splicing of Canine CNGA3

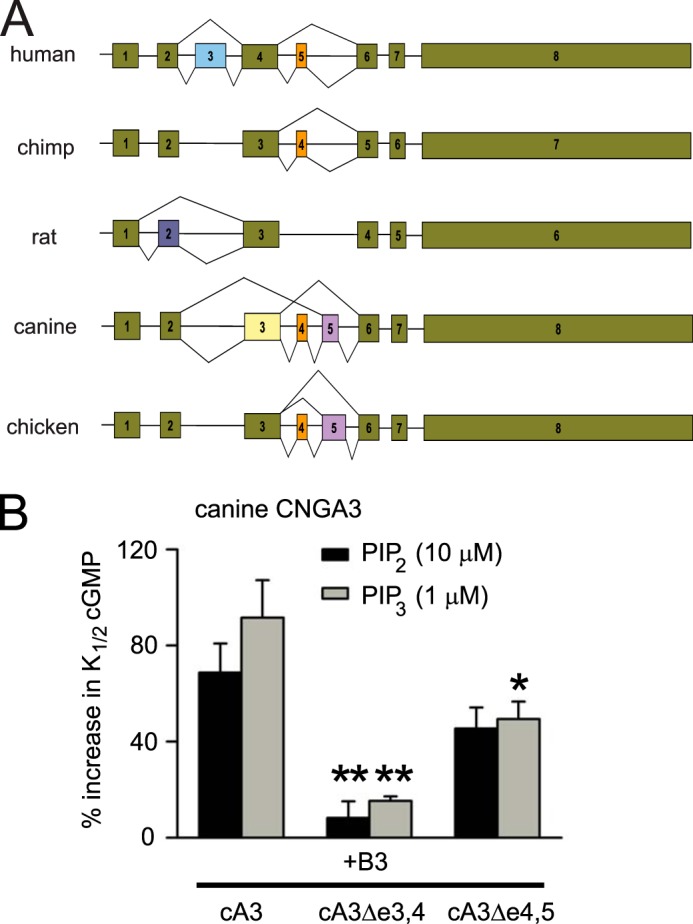

We discovered that transcripts encoding canine CNGA3 subunits also are subject to alternative splicing. There are three alternative exons encoding a region within the N-terminal cytoplasmic domain of canine CNGA3: exons 3, 4, and 5. Canine exons 3 and 4 are orthologous to human exons 4 and 5, respectively (Fig. 6A). Canine exon 5 has no equivalent exon in humans but is similar to exon 5 of chicken CNGA3 (22). RT-PCR using canine retinal mRNA revealed that three splice variants of canine CNGA3 were generated: the reference canine CNGA3 with all optional exons included (cCNGA3), a variant lacking exons 3 and 4 (cCNGA3 Δe3,4), and a variant lacking exons 4 and 5 (cCNGA3Δe4,5). We tested the PIPn sensitivity of all three canine CNGA3 isoforms after expression with human CNGB3 (Fig. 6B). We found that channels containing cCNGA3 having a sequence encoded by all the optional exons exhibited a considerable PIPn-induced increase in K1/2,cGMP. For cCNGA3+CNGB3 channels, K1/2,cGMP increased from 13.9 ± 0.7 μm (n = 8) to 27.6 ± 4.0 μm (n = 4) after 1 μm PIP3 or to 22.9 ± 1.8 μm (n = 4) after 10 μm PIP2. Interestingly, the PIPn-induced increase in K1/2,cGMP was eliminated for cCNGA3Δe3,4 + CNGB3 channels (p < 0.001 for both PIP2 and PIP3 compared with the reference channel). For cCNGA3Δe4,5 + CNGB3 channels, the PIPn-induced increase in K1/2,cGMP was attenuated (p < 0.05 for PIP3). Presumably, the region encoded by exon 3 in canine CNGA3, similar to exon 4 in human CNGA3, contains a PIPn interaction site. Skipping this exon abolished the PIPn sensitivity of the channel. Together, these results indicate that alternative splicing of both canine and human CNGA3, with divergent splice patterns, similarly tunes the PIPn sensitivity of heteromeric cone CNG channels.

FIGURE 6.

Alternative splicing of canine CNGA3 transcripts also tunes PIPn sensitivity. A, CNGA3 splicing pattern for constitutive (green) and alternative cassette exons across representative species. Exon (box) lengths, but not intron (line) lengths, are shown to scale. For simplicity, removal of introns between constitutive exons is not shown. B, summary of PIP2 and PIP3 effects on K1/2,cGMP for heteromeric CNGA3+CNGB3 channels containing canine CNGA3 isoforms generated by alternative splicing. All subunit combinations exhibited sensitivity to blocking by l-cis-diltiazem, confirming the formation of functional heteromeric channels. Data are mean ± S.E. of four independent experiments. **, p < 0.01; *, p < 0.05 compared with channels having all regions encoded by e3, e4, and e5.

DISCUSSION

For genes encoding CNG channel subunits, three are known to exhibit alternatively spliced transcripts: CNGB1, CNGA3, and CNGA1. The functional and physiological consequences of alternative splicing of CNGB1 have been elucidated previously (26–28, 41–43). In this work, we found that alternative splicing of CNGA3 tunes the phosphoinositide sensitivity of cone CNG channels. Inclusion of the human-specific alternative exon 3 generated CNGA3 isoforms that significantly potentiated the PIP2 or PIP3 sensitivity of CNGA3+CNGB3 channels. The region encoded by exon 3 alone was not sufficient to support PIPn sensitivity in the absence of the other known PIPn regulation modules. The effect of the exon 3-encoded sequence on PIPn sensitivity appears to be mediated by an allosteric mechanism whereby the modified N-terminal cytoplasmic domain enhances the change in K1/2,cGMP mediated by the C-terminal PIPn regulation module of CNGA3.

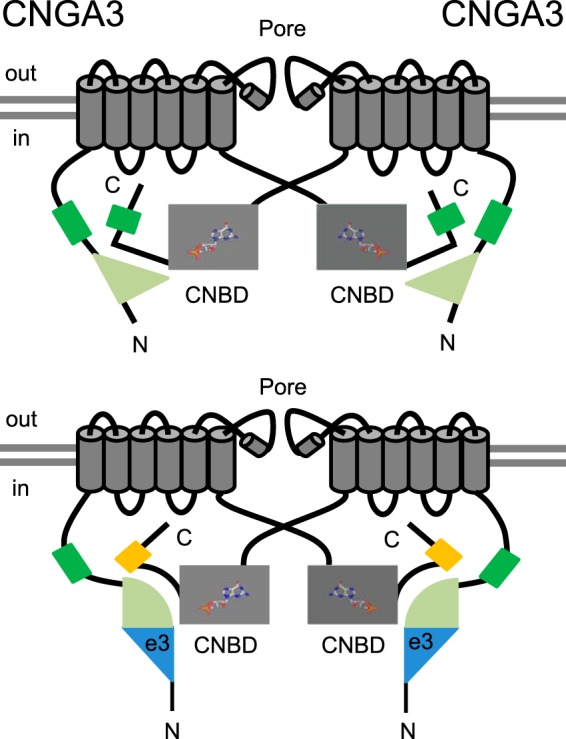

Previous studies in our lab have demonstrated the importance of intersubunit N-C interactions for control of the PIPn sensitivity of cone CNG channels (16, 40). This idea is consistent with the results described here for enhancement of PIPn sensitivity by exon 3 inclusion, which inserts 55 additional amino acids into the N-terminal domain but depends on the C-terminal PIPn regulation module rather than the adjacent N-terminal PIPn regulation site. Although the exact mechanism underlying potentiation of PIPn sensitivity in the e3 isoform is not fully understood, we hypothesize that, with the assistance of CNGB3, the conformational difference in the CNGA3 N-terminal region caused by inclusion or exclusion of the region encoded by exon 3 is coupled to the C-terminal region of the adjacent CNGA3 subunit, altering the ability of the C-terminal PIPn regulation module to respond to membrane-bound phosphoinositides (Fig. 7). In other words, incorporation of the exon 3-encoded sequence modulates the N-C interactions of CNGA3 subunits, thus potentiating the PIPn sensitivity of cone CNG channels. The exon 3-encoded sequence may also influence CNGA3-CNGB3 interactions because these are also thought to modulate PIPn sensitivity and the competency of the C-terminal PIPn regulation module in CNGA3 to confer a change in K1/2,cGMP (16). Interestingly, in addition to well characterized N-C-terminal interactions for CNG channels (32, 44–47, 28), a recent crystal structure of the EAG domain-cyclic nucleotide-binding homology domain (CNBHD) complex of homologous mEAG1 (KCNH) channels revealed that the post-CNBHD region (equivalent to the region adjacent to the C-terminal PIPn regulation module in CNGA3) is interacting directly with the N-terminal EAG domain (48). Moreover, we have shown previously that truncations and point mutations in this post-cyclic nucleotide-binding domain region can influence the N-terminal PIPn regulation module of CNGA3 (16, 40). We propose that the coupling between N- and C-terminal regions of CNGA3 (and presumably CNGB3) is an essential element of cone CNG channel regulation. However, more sophisticated structural approaches may be required to elucidate the precise interdomain contacts and detailed conformational changes associated with the e3 variant.

FIGURE 7.

Schematic for altered N-C coupling with the CNGA3-e3 isoform. The model illustrates how incorporation of the e3-encoded sequence within the N-terminal region of CNGA3 may enhance the C-terminal PIPn regulation module by altering intersubunit interactions. The green and yellow boxes indicate basal and enhanced PIPn regulation modules, respectively. We propose that the interface mediating N-C coupling for CNGA3 is altered in the e3 isoform. For clarity, the CNGB3 subunits are not shown, but CNGA3-CNGB3 interactions may also be altered for channels containing the e3 isoform. CNBD, cyclic nucleotide binding domain.

We found that alternative splicing of canine CNGA3 also regulates the phosphoinositide sensitivity of the resulting channels. Together, these findings suggest that the functional significance of CNGA3 alternative splicing might be conserved across species, despite the divergence in exon combinations for the orthologous genes. Considering that exon 3-containing transcripts were expressed in 23 human tissues, including heart, kidney, and brain (29), enhanced phosphoinositide sensitivity by CNGA3e3 may have widespread physiological significance. However, how tuning of PIPn regulation of CNG channels by alternative splicing is related to function in cone photoreceptors and other cell types is not understood. The functional importance of optional exon 5 remains elusive. On the basis of previous work showing that the human CNGA3 e5-containing transcripts were expressed primarily in the retina (29), exon 5 might contain features favoring its inclusion here, such as exonic splicing enhancers recognized by neuron- or retina-specific splicing factors expressed in a tissue-specific manner. The splicing factors and cis-regulatory features driving e3 inclusion also are unknown. The sequence upstream of exon 3 presents a weak poly-pyrimidine tract that likely necessitates splicing enhancer sequences that facilitate e3 inclusion.

The functional CNGA3e3 variant seems to represent a recent innovation along the human evolutionary pathway. Comparative analysis of alternative splicing patterns in humans and chimpanzees reveal that, for at least 4% of genes, one or more cassette alternative exons display pronounced splicing differences between the species (49). Human-specific patterns of alternative splicing have been found to be particularly widespread within the brain (50). Also, it has been estimated that humans and chimpanzees differ by at least 6% in their complement of genes (51). The trichromatic visual system is one of the dramatic specializations present in the human lineage compared with other mammals. It is not entirely surprising that unique patterns of splicing and/or gene regulation may be related to these specializations (52, 53).

Acknowledgments

We thank Elizabeth Rich for technical support; Changhong Peng, Daylene Mills, and Tealia Davis for performing pilot studies; King-Wai Yau for sharing the cDNA clone for human CNGA3; and Peter Meighan and Lane Brown for constructive input.

This work was supported by NEI, National Institutes of Health grant EY12836 (to M. D. V.).

- CNG

- cyclic nucleotide-gated

- PIP2

- phosphatidylinositol 4,5-biphosphate

- PIP3

- phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate

- CaM

- calmodulin

- PIPn

- phosphoinositide(s).

REFERENCES

- 1. Burns M. E., Arshavsky V. Y. (2005) Beyond counting photons: trials and trends in vertebrate visual transduction. Neuron 48, 387–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jan L. Y., Jan Y. N. (1990) A superfamily of ion channels. Nature 345, 672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Isacoff E. Y., Jan L. Y., Minor D. L., Jr. (2013) Conduits of life's spark: a perspective on ion channel research since the birth of neuron. Neuron 80, 658–674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Craven K. B., Zagotta W. N. (2006) CNG and HCN channels: two peas, one pod. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 68, 375–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hsu Y. T., Molday R. S. (1993) Modulation of the cGMP-gated channel of rod photoreceptor cells by calmodulin. Nature 361, 76–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gordon S. E., Downing-Park J., Zimmerman A. L. (1995) Modulation of the cGMP-gated ion channel in frog rods by calmodulin and an endogenous inhibitory factor. J. Physiol. 486, 533–546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Trudeau M. C., Zagotta W. N. (2003) Calcium/calmodulin modulation of olfactory and rod cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channels. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 18705–18708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Trudeau M. C., Zagotta W. N. (2004) Dynamics of Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent inhibition of rod cyclic nucleotide-gated channels measured by patch-clamp fluorometry. J. Gen. Physiol. 124, 211–223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bradley J., Bönigk W., Yau K.-W., Frings S. (2004) Calmodulin permanently associates with rat olfactory CNG channels under native conditions. Nat. Neurosci. 7, 705–710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Molokanova E., Maddox F., Luetje C. W., Kramer R. H. (1999) Activity-dependent modulation of rod photoreceptor cyclic nucleotide-gated channels mediated by phosphorylation of a specific tyrosine residue. J. Neurosci. 19, 4786–4795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gordon S. E., Brautigan D. L., Zimmerman A. L. (1992) Protein phosphatases modulate the apparent agonist affinity of the light-regulated ion channel in retinal rods. Neuron 9, 739–748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Meighan P. C., Meighan S. E., Rich E. D., Brown R. L., Varnum M. D. (2012) Matrix metalloproteinase-9 and -2 enhance the ligand sensitivity of photoreceptor cyclic nucleotide-gated channels. Channels Austin 6, 181–196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Meighan S. E., Meighan P. C., Rich E. D., Brown R. L., Varnum M. D. (2013) Cyclic nucleotide-gated channel subunit glycosylation regulates matrix metalloproteinase-dependent changes in channel gating. Biochemistry 52, 8352–8362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Womack K. B., Gordon S. E., He F., Wensel T. G., Lu C. C., Hilgemann D. W. (2000) Do phosphatidylinositides modulate vertebrate phototransduction? J. Neurosci. 20, 2792–2799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Brady J. D., Rich E. D., Martens J. R., Karpen J. W., Varnum M. D., Brown R. L. (2006) Interplay between PIP3 and calmodulin regulation of olfactory cyclic nucleotide-gated channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 15635–15640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dai G., Peng C., Liu C., Varnum M. D. (2013) Two structural components in CNGA3 support regulation of cone CNG channels by phosphoinositides. J. Gen. Physiol. 141, 413–430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fain G. L., Matthews H. R., Cornwall M. C., Koutalos Y. (2001) Adaptation in vertebrate photoreceptors. Physiol. Rev. 81, 117–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ko G. Y., Ko M. L., Dryer S. E. (2004) Circadian regulation of cGMP-gated channels of vertebrate cone photoreceptors: role of cAMP and Ras. J. Neurosci. 24, 1296–1304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chen S.-K., Ko G. Y., Dryer S. E. (2007) Somatostatin peptides produce multiple effects on gating properties of native cone photoreceptor cGMP-gated channels that depend on circadian phase and previous illumination. J. Neurosci. 27, 12168–12175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Körschen H. G., Illing M., Seifert R., Sesti F., Williams A., Gotzes S., Colville C., Müller F., Dosé A., Godde M. (1995) A 240 kDa protein represents the complete β subunit of the cyclic nucleotide-gated channel from rod photoreceptor. Neuron 15, 627–636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sautter A., Zong X., Hofmann F., Biel M. (1998) An isoform of the rod photoreceptor cyclic nucleotide-gated channel β subunit expressed in olfactory neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 4696–4701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bönigk W., Müller F., Middendorff R., Weyand I., Kaupp U. B. (1996) Two alternatively spliced forms of the cGMP-gated channel α-subunit from cone photoreceptor are expressed in the chick pineal organ. J. Neurosci. 16, 7458–7468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Meyer M. R., Angele A., Kremmer E., Kaupp U. B., Muller F. (2000) A cGMP-signaling pathway in a subset of olfactory sensory neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 10595–10600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wissinger B., Gamer D., Jägle H., Giorda R., Marx T., Mayer S., Tippmann S., Broghammer M., Jurklies B., Rosenberg T., Jacobson S. G., Sener E. C., Tatlipinar S., Hoyng C. B., Castellan C., Bitoun P., Andreasson S., Rudolph G., Kellner U., Lorenz B., Wolff G., Verellen-Dumoulin C., Schwartz M., Cremers F. P., Apfelstedt-Sylla E., Zrenner E., Salati R., Sharpe L. T., Kohl S. (2001) CNGA3 mutations in hereditary cone photoreceptor disorders. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 69, 722–737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Blencowe B. J. (2006) Alternative splicing: new insights from global analyses. Cell 126, 37–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Körschen H. G., Beyermann M., Müller F., Heck M., Vantler M., Koch K. W., Kellner R., Wolfrum U., Bode C., Hofmann K. P., Kaupp U. B. (1999) Interaction of glutamic-acid-rich proteins with the cGMP signalling pathway in rod photoreceptors. Nature 400, 761–766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Poetsch A., Molday L. L., Molday R. S. (2001) The cGMP-gated channel and related glutamic acid-rich proteins interact with peripherin-2 at the rim region of rod photoreceptor disc membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 48009–48016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Michalakis S., Zong X., Becirovic E., Hammelmann V., Wein T., Wanner K. T., Biel M. (2011) The glutamic acid-rich protein is a gating inhibitor of cyclic nucleotide-gated channels. J. Neurosci. 31, 133–141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cassar S. C., Chen J., Zhang D., Gopalakrishnan M. (2004) Tissue specific expression of alternative splice forms of human cyclic nucleotide gated channel subunit CNGA3. Mol. Vis. 10, 808–813 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Grunwald M. E., Zhong H., Lai J., Yau K. W. (1999) Molecular determinants of the modulation of cyclic nucleotide-activated channels by calmodulin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 13444–13449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Weitz D., Zoche M., Müller F., Beyermann M., Körschen H. G., Kaupp U. B., Koch K. W. (1998) Calmodulin controls the rod photoreceptor CNG channel through an unconventional binding site in the N-terminus of the β-subunit. EMBO J. 17, 2273–2284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Varnum M. D., Zagotta W. N. (1997) Interdomain interactions underlying activation of cyclic nucleotide-gated channels. Science 278, 110–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Michalakis S., Geiger H., Haverkamp S., Hofmann F., Gerstner A., Biel M. (2005) Impaired opsin targeting and cone photoreceptor migration in the retina of mice lacking the cyclic nucleotide-gated channel CNGA3. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 46, 1516–1524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Varnum M. D., Black K. D., Zagotta W. N. (1995) Molecular mechanism for ligand discrimination of cyclic nucleotide-gated channels. Neuron 15, 619–625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Peng C., Rich E. D., Varnum M. D. (2004) Subunit configuration of heteromeric cone cyclic nucleotide-gated channels. Neuron 42, 401–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Huang C. L., Feng S., Hilgemann D. W. (1998) Direct activation of inward rectifier potassium channels by PIP2 and its stabilization by Gβγ. Nature 391, 803–806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bright S. R., Rich E. D., Varnum M. D. (2007) Regulation of human cone cyclic nucleotide-gated channels by endogenous phospholipids and exogenously applied phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate. Mol. Pharmacol. 71, 176–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yu W. P., Grunwald M. E., Yau K. W. (1996) Molecular cloning, functional expression and chromosomal localization of a human homolog of the cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channel of retinal cone photoreceptors. FEBS Lett. 393, 211–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pugh E. N., Jr., Nikonov S., Lamb T. D. (1999) Molecular mechanisms of vertebrate photoreceptor light adaptation. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 9, 410–418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dai G., Varnum M. D. (2013) CNGA3 achromatopsia-associated mutation potentiates the phosphoinositide sensitivity of cone photoreceptor CNG channels by altering intersubunit interactions. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 305, C147–C159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Haber-Pohlmeier S., Abarca-Heidemann K., Körschen H. G., Dhiman H. K., Heberle J., Schwalbe H., Klein-Seetharaman J., Kaupp U. B., Pohlmeier A. (2007) Binding of Ca2+ to glutamic acid-rich polypeptides from the rod outer segment. Biophys. J. 92, 3207–3214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zhang Y., Molday L. L., Molday R. S., Sarfare S. S., Woodruff M. L., Fain G. L., Kraft T. W., Pittler S. J. (2009) Knockout of GARPs and the β-subunit of the rod cGMP-gated channel disrupts disk morphogenesis and rod outer segment structural integrity. J. Cell Sci. 122, 1192–1200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ritter L. M., Khattree N., Tam B., Moritz O. L., Schmitz F., Goldberg A. F. (2011) In situ visualization of protein interactions in sensory neurons: glutamic acid-rich proteins (GARPs) play differential roles for photoreceptor outer segment scaffolding. J. Neurosci. 31, 11231–11243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gordon S. E., Varnum M. D., Zagotta W. N. (1997) Direct interaction between amino- and carboxyl-terminal domains of cyclic nucleotide-gated channels. Neuron 19, 431–441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Trudeau M. C., Zagotta W. N. (2002) Mechanism of calcium/calmodulin inhibition of rod cyclic nucleotide-gated channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 8424–8429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Trudeau M. C., Zagotta W. N. (2002) An intersubunit interaction regulates trafficking of rod cyclic nucleotide-gated channels and is disrupted in an inherited form of blindness. Neuron 34, 197–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zheng J., Varnum M. D., Zagotta W. N. (2003) Disruption of an intersubunit interaction underlies Ca2+-calmodulin modulation of cyclic nucleotide-gated channels. J. Neurosci. 23, 8167–8175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Haitin Y., Carlson A. E., Zagotta W. N. (2013) The structural mechanism of KCNH-channel regulation by the EAG domain. Nature 501, 444–448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Calarco J. A., Xing Y., Cáceres M., Calarco J. P., Xiao X., Pan Q., Lee C., Preuss T. M., Blencowe B. J. (2007) Global analysis of alternative splicing differences between humans and chimpanzees. Genes Dev. 21, 2963–2975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lin L., Shen S., Jiang P., Sato S., Davidson B. L., Xing Y. (2010) Evolution of alternative splicing in primate brain transcriptomes. Hum. Mol. Genet. 19, 2958–2973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Demuth J. P., De Bie T., Stajich J. E., Cristianini N., Hahn M. W. (2006) The evolution of mammalian gene families. PloS ONE 1, e85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ward L. D., Kellis M. (2012) Evidence of abundant purifying selection in humans for recently acquired regulatory functions. Science 337, 1675–1678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Farkas M. H., Grant G. R., White J. A., Sousa M. E., Consugar M. B., Pierce E. A. (2013) Transcriptome analyses of the human retina identify unprecedented transcript diversity and 3.5 Mb of novel transcribed sequence via significant alternative splicing and novel genes. BMC Genomics 14, 486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]