Abstract

Much like humans, gene duplicates may be created equal, but they do not stay that way for long. For four completely sequenced genomes we show that 20%–30% of duplicate gene pairs show asymmetric evolution in the amino acid sequence of their protein products. That is, one of the duplicates evolves much faster than the other. The greater this asymmetry, the greater the ratio Ka/Ks of amino acid substitutions (Ka) to silent substitutions (Ks) in a gene pair. This indicates that most asymmetric divergence may be caused by relaxed selective constraints on one of the duplicates. However, we also find some candidate duplicates where positive (directional) selection of beneficial mutations (Ka/Ks > 1) may play a role in asymmetric divergence. Our analysis rests on a codon-based model of molecular evolution that allows a test for asymmetric divergence in Ka. The method is also more sensitive in detecting positive selection (Ka/Ks > 1) than models relying only on pairwise gene comparisons.

Gene duplications are an engine of biochemical innovation (Holland 1999). Much work on the evolution of gene duplication since Ohno (1970) has thus focused on how gene duplicates diverge both in sequence and function. Immediately after duplication, most substitutions in a duplicate are selectively neutral, because the other duplicate can buffer deleterious mutational effects (Nei and Roychoudhury 1973; Li 1980). However, this period of neutrality may be ended by a variety of events: Nucleotide substitutions that affect protein expression, localization, or dimerization (Gibson and Spring 1998; Force et al. 1999) can lead to increasing functional and sequence divergence of gene duplicates and thus to increased selective constraints on both genes. Functional divergence often occurs rapidly, although this is not always the case. For instance Langkjær et al. (2003) have presented evidence suggesting that gene duplicates dating from an ancient whole-genome duplication in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae may not have diversified until well after the duplication event.

Mounting evidence indicates that gene duplicates can assume unequal roles in divergence. A study by one of us suggests that gene function, as indicated by protein interactions and gene expression patterns, diverges asymmetrically for many gene duplicates in the yeast S. cerevisiae (Wagner 2002). Other pertinent evidence comes from sequence divergence. Some of this evidence is based on detailed studies of individual genes. For example, Li and Tsoi (2002) found that mammalian lactate dehydrogenase C evolved more rapidly than lactate dehydrogenase A. A large-scale study by Kondrashov et al. (2002) analyzed 39 genomes from eubacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes and found a small number of cases of asymmetric divergence among 101 analyzed duplicate gene pairs. In contrast to this study, where the incidence of asymmetric divergence was <5%, Van de Peer et al. (2001) found that fully half of 26 duplicate gene pairs in zebrafish showed evidence of asymmetric divergence. Using a more sensitive amino acid-based method to detect asymmetry, Dermitzakis and Clark (2001) found that roughly 50% of 12 mammalian transcription factor paralogs showed evidence of asymmetric evolution. The functional significance of such asymmetric divergence is still unclear, although some existing evolutionary models might contribute to an explanation. For example, it has been argued that some form of evolutionary asymmetry is required for functional diversification of duplicates (Krakauer and Nowak 1999) and that asymmetric functional divergence might reflect selection for mutational robustness (Wagner 2002). However, before one can seriously pursue evolutionary models explaining asymmetry, it is necessary to establish its incidence, because existing work has not yielded a final picture.

Previous work on asymmetric sequence divergence relies on relative rate tests between two duplicates and an outgroup gene, using either nucleotide or amino acid substitutions (Van de Peer et al. 2001; Kondrashov et al. 2002; Li and Tsoi 2002). Nucleotide-based tests cannot distinguish between silent substitutions and amino acid replacement substitutions. The presence of (often neutral) silent substitutions may obscure any signal of asymmetry, which mostly derives from replacement substitutions. Amino acid-based models, on the other hand, have problems with correctly determining outgroup genes, which is necessary to calibrate divergence estimates. Specifically, if two duplicates have diverged asymmetrically, one of the duplicates may have become more divergent than a true outgroup gene. For this reason, amino acid-based methods also tend to underestimate the number of gene pairs with asymmetric divergence. These shortcomings prompted us to use a codon-based model of evolution that distinguishes between silent substitutions and amino acid replacement substitutions when testing for asymmetric protein sequence divergence.

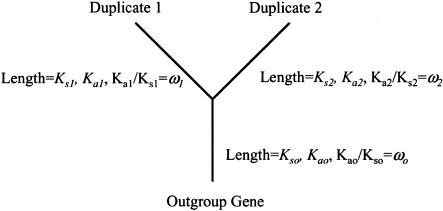

Codon-based models of sequence evolution can address questions in both phylogenetics and molecular evolution (for discussion, see Liò and Goldman 1998; and Lewis 2001). Such models estimate both synonymous divergence (Ks) and non-synonymous divergence (Ka) between genes. For the purpose of this study, we use the model of Muse and Gaut (1994; A very similar model is described by Goldman and Yang 1994.). This model allows each of the three branches in our phylogenetic tree to have its own value of Ks and Ka (See Fig. 1). To study asymmetric divergence, we apply the model to gene duplicates from the fully sequenced genomes of the yeasts S. cerevisiae (Goffeau et al. 1996) and Schizosaccharomyces pombe (Wood et al. 2002), the nematode worm Caenorhabditis elegans (The C. elegans Sequencing Consortium 1998), and the fruit fly D. melanogaster (Adams et al. 2000).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of our model tree. Two duplicates are presumed to have diverged from an outgroup gene. Each of the three branches of this tree is allowed to have its own Ks and Ka values.

RESULTS

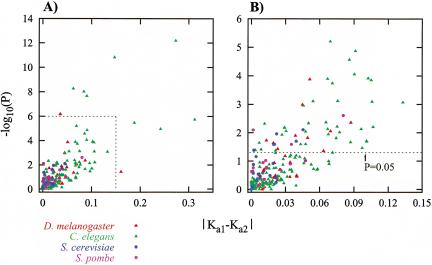

Figure 2 shows a simple measure of asymmetric divergence: the absolute difference |Ka1-Ka2| of the number of amino acid replacement substitutions per site for each gene pair analyzed, plotted against that pair's statistical significance P (as –log10 P). As described in the Methods, we tested the hypothesis that the number of pairs with asymmetric Ka values could be explained by the 5% error rate of our individual hypothesis tests. For all four genomes, we must reject this null hypothesis (baker's yeast: P = 7×10–5, fission yeast: P = 0.0042, fruit fly: P = 2×10–8, worm: P = 6×10–15). Clearly, many gene pairs diverge asymmetrically. A full list of the identified asymmetric pairs is available from our website (http://www.unm.edu/compbio/Supplemental_Data/Sequence_Asymm/). Below we discuss, species by species, the number of asymmetric pairs and highlight a few examples.

Figure 2.

Significance of observed differences in Ka. On the X-axis is plotted the absolute value of the difference in Ka value between two duplicates. The Y-axis gives the negative logarithm (to base 10) of the P value for that pair. (A) All asymmetric duplicate pairs shown. (B) Only the square region marked in panel A is shown. The dashed line in B shows the significance level of P = 0.05.

Saccharomyces cerevisiae

In baker's yeast, we identified 22 gene triplets with unsaturated Ks, six of which (27%) showed asymmetry in Ka. An example is the gene pair encoding the alcohol dehydrogenase enzymes ADH3 and ADH1. ADH3 showed an amino acid divergence Ka nearly twice that for ADH1 (Ka1 = 0.101, Ka2 = 0.056, P = 0.008). Interestingly, ADH3 is localized in the mitochondrial matrix (Pilgrim and Young 1987), whereas ADH1 is found in the cytosol (Fraenkel 1982). The alcohol dehydrogenase genes ADH5 and ADH2 also showed asymmetric divergence, but their subcellular localization is unknown. In addition to the alcohol dehydrogenases, the acid phosphatases PHO3 and PHO5, as well as the pyruvate decarboxylases PDC1 and PDC5, showed asymmetric divergence.

Schizosaccharomyces pombe

In fission yeast, we identified 14 unsaturated triplets, three (21%) of which showed asymmetry in Ka. One especially clear-cut case of asymmetry regards the putative aminotransferase genes 19076066 and 19111920. Here, the outgroup (gene 19114182) is very distant from the duplicates (unsaturated Kso of 3.338), making it especially unlikely that the observed asymmetry is a result of incorrect outgroup selection. Asymmetry in Ka is highly significant for these two gene pairs, with Ka2 nearly 80% greater than Ka1 (Ka1 = 0.101, Ka2 = 0.181, P = 0.003). The other asymmetric pairs were putative lysophospholipases and the retrotransposons Tf2-11 and Tf2-12.

Drosophila melanogaster

We identified a total of 44 unsaturated triplets in the fruit fly, of which 13 (30%) showed evidence of asymmetric divergence. Among the asymmetrically diverged gene pairs with known function are the heat-shock genes Hsp-70Aa and Hsp-70-3, the β tubulins 60D and 56D, as well as cytochrome P450 genes Cyp313a1 and Cyp313a2. The genes in the β tubulin triplet all have different tissue-specific expression. β-tubulin 56D is the predominant isoform, while β-tubulin 60D is expressed in various larval, pupal, and adult cells (Kimbel et al. 1989; Hoyle and Raff 1990). The outgroup for these two genes, β-tubulin 85D, is an isoform specific to the male germ line (Fackenthal et al. 1993, 1995).

An extreme example of asymmetric divergence in the fruit fly regards the LysB and LysE genes (outgroup LysD). The two genes show similar Ks values (Ks1 = 0.054, Ks2 = 0.057), but distinct Ka values (Ka1 = 0, Ka2 = 0.013). All three genes belong to the lysozyme D gene family. This gene family is expressed in the larval midgut (Kylsten et al. 1992; Daffre et al. 1994) and its members have chitinase activity (Regel et al. 1998), an interesting parallel to the asymmetrically diverged chitinase genes of Caenorhabditis elegans (see below).

Caenorhabditis elegans

We found 164 unsaturated triplets in the worm genome, 46 (28%) of which show asymmetric divergence. Six of the asymmetric pairs contain 7-helix transmembrane chemoreceptor domains. This nematode uses chemical signals to locate food (Delattre and Félix 2001), attract mates (Simon and Sternberg 2002), and initiate the social feeding response (de Bono et al. 2002), and the divergence of such pairs may increase the specificity of responses to these signals.

Like their fruit fly counterparts, two pairs of worm cytochrome P450 genes evolved asymmetrically. Cytochrome P450 is involved in detoxifying xenobiotics (Mathews and Van Holde 1996), and some worm family members have been shown to be xenobiotically inducible (Menzel et al. 2001). The asymmetric evolution of these genes may be related to challenges from environmental toxins.

Two further functional families with asymmetric pairs contain proteins with F-box domains and chitinases. Chitin is present in some nematodes' prey and in their own eggs (Muzzarelli and Muzzarelli 1998), suggesting the need for specialized chitinase enzymes.

Asymmetric Amino Acid Divergence and Gene Expression Profiles

We tested the hypothesis that asymmetric amino acid divergence is coupled to greater gene expression divergence in one of two duplicate genes. To do so, we used data from mRNA microarray experiments in yeast (Gasch et al. 2000) and nematodes (Kim et al. 2001). We found no significant correlation between degree of asymmetry in Ka and divergence in expression level (baker's yeast: Pearson's r: –0.28, P = 0.33, Spearman's s: –0.17, P = 0.56; n = 14; worm: Pearson's r: –0.01, P = 0.90, Spearman's s: –0.04, P = 0.69, n = 119). We also calculated the statistical association between asymmetry in expression level (see Wagner 2002) and asymmetry in Ka. Once again, we found no significant association (baker's yeast: Pearson's r: 0.03, P = 0.91, Spearman's s: 0.08, P = 0.77; n = 14; worm: Pearson's r: –0.04, P = 0.64, Spearman's s: –0.10, P = 0.30, n = 119).

Asymmetry and Strength of Selection

We examined the statistical association between asymmetry in amino acid divergence and evolutionary constraints on duplicate pairs, as indicated by Ka/Ks (see Methods). We excluded fission yeast from this analysis because of its small number of informative gene triplets. To avoid artifacts resulting from codon usage bias in baker's yeast, we excluded gene pairs where either gene had a codon bias index (Bennetzen and Hall 1982) value >0.5. In baker's yeast (Fig. 3A), we observed a weakly significant correlation between the asymmetric amino acid divergence and selective constraint (Pearson's r = 0.73, P = 0.005, Spearman's s = 0.56, P = 0.046, n = 13). The larger samples from fruit fly (Fig. 3B) and worm (Fig. 3C) both yield highly significant correlations (fruit fly: Pearson's r = 0.64, Spearman's s = 0.52, n = 43, worm: Pearson's r = 0.58, Spearman's s = 0.39, n = 161, P < 0.001 for all).

Figure 3.

Correlation of the normalized difference in Ka between two duplicates and the difference in the selective constraint for those two duplicates. The variables on the axes labels are |ΔKa| = |(Ka1 – Ka2)/(Ka1 + Ka2)| and |ΔKa/Ks| = |(Ka1/Ks1 – Ka2/Ks2)/(Ka1/Ks1 + Ka2/Ks2)|, respectively. (A) S. cerevisiae. (B) D. melanogaster. (C) C. elegans.

Positive Selection in Duplicate Genes

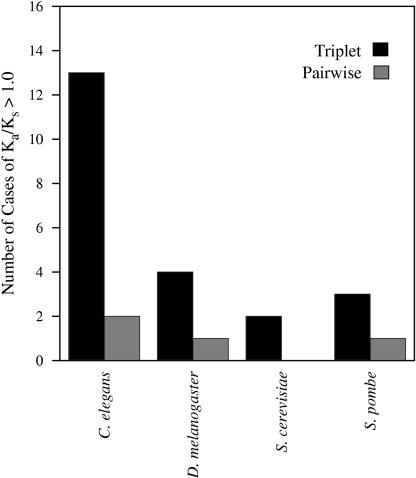

The triplet-based method of analysis permits estimation of the Ka/Ks ratio for each gene in a duplicate pair separately. As Figure 4 makes clear, such separate estimation produces many more candidate cases of Ka/Ks > 1.0 than does conventional pairwise analysis. None of the pairwise cases of Ka/Ks > 1 are statistically significant at P ≤ 0.05. In the triplet data, we found one significant case of positive selection out of 22 gene duplicates with Ka/Ks > 1.0: the worm gene Y56A3A.10 (duplicate partner: Y56A3A.14, outgroup: Y56A3A.15, P = 0.029). This gene pair also shows significant asymmetry in Ka divergence (P = 0.009), consistent with the notion that one of the genes underwent directional selection. Functional information about these genes is limited, except that all three genes contain an F-box domain which is involved in ubiquitin-mediated protein degradation and spermatogenesis (Kipreos and Pagano 2000).

Figure 4.

Triplet-based analysis is more sensitive in detecting positive selection. Number of cases where at least one duplicate in a pair has Ka/Ks > 1.0 for the four organisms shown using our triplet method (black) and using the conventional pairwise estimation (grey). The total number of duplicates pairs for which we determined Ka/Ks in this analysis was 22 for S. cerevisiae, 14 for S. pombe, 44 for D. melanogaster, and 164 for C. elegans.

DISCUSSION

Asymmetries in rates of amino acid divergence are common in our four test genomes. Sample sizes are small in some genomes (e.g., 14 gene pairs for fission yeast), but taken together, our results suggest that an average genome contains at least 20% of gene duplicates that diverge asymmetrically. The largest samples come from the worm and fruit fly genomes, where between 28% and 30% of gene pairs showed asymmetric divergence. Our estimate lies in between that of Van de Peer et al. (2001) for DNA sequence divergence in vertebrate duplicates (50%), and that of another systematic study using various completely sequenced genomes (<5%; Kondrashov et al. 2002). Differences in approach may be responsible for these discrepancies. For example, Kondrashov and collaborators (2002) required that two duplicates be closer in amino acid sequence to each other than to the outgroup. This is a sensible assumption, but it leads to an underestimate of the number of asymmetrically diverged genes, because if asymmetric divergence occurs, one of the duplicates may become more divergent than the outgroup gene. In addition, amino acid models (such as that used by Kondrashov et al. 2002) do not directly consider the structure of the genetic code in their estimates. Such models may thus underestimate divergence, as some amino acid substitutions require multiple nucleotide substitutions to achieve (Ota and Nei 1994). We circumvent these potential biases by using a codon model and requiring that the synonymous divergence of duplicates must be lower than that of the outgroup.

Caveats

The biggest caveat to our approach is that it requires gene triplets that meet several stringent criteria (see Methods). It will thus yield only a moderate number of informative gene pairs. We also note that our approach may still occasionally miss asymmetrically diverged duplicates, especially if outgroup branches are long, or if the genes in question are short. In that case, the number of asymmetrically diverging genes would be higher than observed.

Asymmetry in Sequence Divergence and Functional Divergence

Is asymmetric divergence in sequence coupled to asymmetric divergence in gene function? Do rapidly evolving duplicates acquire new functions more often than slowly evolving duplicates? These obvious questions are very difficult to answer systematically. First, many asymmetrically diverging gene pairs have completely unknown function. Second, reliable indirect indicators of gene function, such as gene expression patterns, are available for many genes only in a select few organisms. Among our four organisms, baker's yeast and the nematode contain the information necessary to address such questions.

Indirect indicators of yeast gene function include gene expression (for examples, see Spellman et al. 1998; Gasch et al. 2000), subcellular localization (Kumar et al. 2002), protein interactions (Uetz et al. 2000; Ito et al. 2001), and the effects of synthetic null (“knock-out”) mutations on the expression of other genes (Hughes et al. 2000b). Such information is available for anywhere from a few hundred genes in the case of gene knockout effects on gene expression (Hughes et al. 2000b), to almost all genes in the case of gene expression data. Asymmetric divergence of gene duplicates has previously been detected in baker's yeast for several of these indicators of gene function (Wagner 2002). In worm, less functional data is available, but both large microarray experiments (Kim et al. 2001) and whole-genome RNAi knockdown experiments (Kamath et al. 2003) have been performed. Is such functional asymmetry correlated with sequence asymmetry? For expression data, the answer appears to be no. Asymmetric gene expression divergence is driven by the differential evolution of regulatory regions, not coding sequences. Because the evolution of coding sequences is only weakly coupled with that of gene expression (Wagner 2000), it is unsurprising that gene expression divergence is uncoupled to asymmetric sequence divergence. We can currently not answer whether other indicators of functional divergence are more closely coupled to asymmetric sequence divergence in baker's yeast because of our small number of asymmetric triplets.

Why Asymmetric Sequence Divergence?

Two principal forces can drive the asymmetric divergence of genes: relaxed selective constraints and directional selection. In the first case, sequence divergence is neutral, that is, it does not involve positive selection of advantageous mutations on the more rapidly evolving gene. In the second case, divergence follows a selectionist scenario, where advantageous mutations play a prominent role. The answer to the above question would contribute important evidence to the neutralist-selectionist debate (Li 1997).

For baker's yeast, fruit fly, and worm there is clear evidence for relaxed selective constraints in asymmetrically diverged genes. That is, the more asymmetrically two genes diverge, the greater is the difference in the ratio of amino acid replacement to synonymous substitutions (Ka/Ks) between them (Fig. 3). Such differences in constraints can arise if two duplicates come to be expressed in different cell compartments or tissues, encountering different interaction partners and chemical milieus. The asymmetrically diverged baker's yeast genes ADH1 (cytosolic) and ADH3 (mitochondrial; Fraenkel 1982; Pilgrim and Young 1987) and the β-tubulins in fruit fly constitute examples of this phenomenon.

We also detected several candidate gene pairs where positive selection may have taken place. Positive selection is indicated when the rate of nonsynonymous substitutions (Ka) exceeds the rate of synonymous substitutions (Ks) (Ka/Ks > 1 [Li 1997]). Because the current model does not assume gene duplicates evolve symmetrically, it can look for cases of Ka/Ks > 1.0 in individual genes, potentially improving sensitivity in detecting positive selection over pairwise methods. This is born out by the data in Figure 4, which shows that the triplet-based method detects many more genes with Ka/Ks > 1.0. However, only one among them has Ka/Ks significantly greater than one. This is an (asymmetric) worm gene pair containing an F-box domain, which may be involved in spermatogenesis (Kipreos and Pagano 2000). We note that positive selection has been shown in the male reproductive genes of other organisms (Nurminsky et al. 1998; Wyckoff et al. 2000).

At first sight, the above analysis suggests that neutral relaxation of selective constraints may be largely responsible for asymmetric divergence. However, this conclusion would be premature. Ka/Ks as an indicator of positive selection averages across all nucleotides in a gene and through time since divergence, but positive selection often acts only on a small fraction of key nucleotides over a short period. To detect positive selection with Ka/Ks requires that selection have been both strong and recent. Thus, although positive selection is pervasive (Hughes and Hughes 1993; Hughes et al. 2000a; Fay et al. 2002; Smith and Eyre-Walker 2002), the ratio Ka/Ks can usually be used to demonstrate positive selection only in conjunction with phylogenetic and functional information, or with information on amino acid polymorphisms (Tsaur et al. 1998; Zhang et al. 1998). This means that many of our gene duplicates that show relaxed selective constraint may actually have experienced positive selection, which cannot be detected using sequence information alone. Again, functional genomic and phylogenetic data are necessary to arrive at a firm conclusion. What will this final conclusion be? If three decades worth of molecular evolution studies are any guide, asymmetric divergence will be the result of neutral divergence for some genes, and the result of positive selection for others.

METHODS

Model of Sequence Evolution

Following Muse and Gaut (1994), we applied a codon model (which allows for the possibility that duplicate genes evolve independently) to three-taxa trees containing two duplicate genes and an outgroup (see Fig. 1). We tested for statistically significant differences in the rate of evolution between duplicates with a likelihood ratio test. This test compares the likelihood (Felsenstein 1981) of observing the data when the duplicates' rate of amino acid divergence is constrained to be equal (Ka1 = Ka2, see Fig. 1) to the unconstrained likelihood. Asymptotically, twice the ratio of these likelihoods follows a χ2 distribution with one degree of freedom (Goldman 1993).

To test the validity of the χ2 distribution for our data, we applied parametric bootstrapping (Hillis et al. 1996) to one asymmetrically diverged gene pair from each genome. Briefly, we simulated the evolution of triplets assuming symmetric divergence, analyzed the simulated triplets, and examined the distribution of the likelihood differences, which was consistent with a χ2 distribution (χ2 goodness-of-fit test, results not shown).

Selection of Gene Duplicates

At first sight, it might seem most sensible to choose outgroup genes from a separate genome. However, this approach faces two serious obstacles: (1) Currently available outgroup genomes are evolutionarily distant, showing saturation in synonymous sites for many genes, and (2) it is often impossible to differentiate recent gene duplications in the test genome from the loss of ancient duplicates in the outgroup genome. In a recent paper, Kondrashov and collaborators (2002) attempted to avoid this problem by analyzing duplicates that were closer to each other in amino acid sequence than either was to the outgroup. This conservative approach can potentially lead to underestimation of the number of asymmetrically diverged gene pairs because some asymmetric pairs may violate this requirement.

For these reasons, we pursued a within-genome approach in our four genomes (the baker's yeast S. cerevisiae, the fission yeast S. pombe, the nematode worm C. elegans, and the fruit fly D. melanogaster). We identified triplets of genes closest to each other in synonymous divergence, Ks using our whole-genome analysis tool (Conant and Wagner 2002). We considered the two closet members of the triplet (in terms of Ks) the duplicates, while the third gene constituted the outgroup. When faced with multiple outgroup choices (in gene families of >3 genes), we chose the closest outgroup gene, because outgroups with shorter branch lengths yield more trustworthy divergence estimates (Muse and Weir 1992).

We excluded gene triplets where (1) the outgroup gene showed <40% amino acid identity to the other two genes, (2) any genes differed in length by >20%, (3) members of a triplet were an alternatively spliced version of the same gene, and (4) member genes showed saturation in synonymous divergence (Ks). We determined saturation in Ks with a heuristic test: Saturation was inferred if there was no decrease in the likelihood of observing the sequence data when the divergence (Ks value) for the sequence was increased beyond the maximum likelihood estimate.

The complex phylogenies of large gene families makes determining duplication orders difficult, leading us to exclude gene families of nine or more members from analysis.

Assessment of Asymmetry in Duplicates

We aligned triplets using CLUSTAL W (Thompson et al. 1994), removed gap characters, and calculated the likelihood of observing these alignments under two evolutionary models: (1) an unconstrained model (distinct Ka and Ks values), and (2) a model where the duplicates were constrained to have Ka1 = Ka2. Nucleotide frequencies were estimated from the sequence alignments. Cases where pairwise Ks estimates had incorrectly identified the outgroup were corrected manually (five triplets in fruit fly and seven triplets in worm). We also excluded from analysis triplets with highly diverged outgroups (Kso > 4 or Kao > 1), because longer outgroup branches decrease sensitivity to asymmetries. In the remaining gene triplets, a likelihood ratio statistic >3.85 (χ2 P ≤ 0.05) between the two models indicated asymmetrical amino acid divergence. Analysis of all identified asymmetric pairs (P ≤ 0.05) with a model that allowed each codon position to have its own nucleotide frequencies did not affect our conclusions (results not shown).

Significance of Observed Patterns of Asymmetry

Using a P = 0.05 significance cutoff for repeated statistical tests can lead to elevated type I errors (false positives). Although this problem can be avoided with a Bonferroni correction (Sokal and Rohlf 1995: adjusts the P-value of individual tests to give a desired “family” error rate), such corrections reduce the power of individual tests. For our purposes, it is less important to minimize false positives than to discover whether the number of apparently asymmetrically diverged genes in a genome can be explained by chance. We therefore took a different approach to assess false positives. With a significance cutoff of P = 0.05, we would expect 5% of the individual triplet tests to falsely reject the null hypothesis of symmetric divergence. We used a binomial distribution with parameter p = 0.05 to ask: “How likely would it be to observe the actual number of asymmetric triplets due solely to false positives?”

Functional Distribution of Asymmetric Pairs

We used public databases for annotations: the Saccharomyces Genome Database (baker's yeast; Cherry et al. 1998), the S. pombe genome sequence (fission yeast; Wood et al. 2002), Flybase (fruit fly; The FlyBase Consortium 2002), and WormBase (nematode; Stein et al. 2001).

Analysis of Expression Profiles

Using microarray expression data from baker's yeast (Gasch et al. 2000) and worm (Kim et al. 2001), we asked whether there was a statistical association between sequence asymmetry and (1) expression divergence and (2) asymmetry of expression divergence. In the baker's yeast data (time-series data for 11 experimental conditions), we used log2-transformed ratios of fluorescence intensities at previously described time points where (on average) maximal induction or repression was seen (Wagner 2002; use of Gasch et al.'s full data set produces qualitatively identical results, not shown). For worm, we again used log2-transformed ratios, accepting only gene pairs where at least 100 matching microarray data points were available. Data were normalized by the number of experiments per pair. For both organisms, we treated as constant all data points with less than twofold expression change. Requiring fourfold expression change excluded too many data points in yeast to permit analysis but gave similar results in the worm (not shown). To avoid microarray cross-reactivity between recent duplicates, we excluded pairs with Ks1+Ks2 < 0.1.

To answer part (1) of the above question, we calculated the absolute value of the difference in transformed ratios between our duplicate pair, summed over all conditions. We compared this net expression deviation to the normalized absolute difference in amino acid divergence Ka between the duplicates, given by

|

(1) |

For part (2), we counted the number of experimental conditions where a gene was over- or underexpressed by at least twofold, a crude indicator of the number of conditions under which each duplicate has a significant change in expression. If expression patterns have diverged asymmetrically, one gene will show expression change in a significantly greater number of conditions than the other (Wagner 2002). We compared the difference in the number of changed conditions to the normalized difference in Ka (equation 1).

Asymmetric Divergence and Selective Constraints

To determine whether asymmetry in amino acid divergence, Ka, was correlated with relaxed selective constraints, we calculated the correlation between the absolute value of the normalized difference in Ka (equation 1) and the absolute value of the normalized difference in selective constraint, measured by:

|

(2) |

Fission yeast was excluded from this analysis because of its small sample size.

Cases of Positive Selection (Ka/Ks > 1.0)

We tested whether observed values of Ka/Ks > 1.0 were significantly different from one with another likelihood ratio test. Here, the constrained model has Kai/Ksi = 1 if duplicate i has Kai/Ksi > 1 (i = 1,2). As above, we used a χ2 distribution with 1 degree of freedom to test the significance of the observed difference in likelihood. We compared the triplet-based method of identifying cases of Ka/Ks > 1.0 to conventional pairwise methods, calculating pairwise significances using a likelihood ratio test of Ka/Ks > 1.0.

Acknowledgments

GCC is supported by the Department of Energy's Computational Sciences Graduate Fellowship program, administered by the Krell Institute. AW thanks the National Institutes of Health (NIH) for its support through NIH grant GM063882–01 and the Santa Fe Institute for its continued support.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

[Supplemental material is available online at www.genome.org. A list of all identified asymmetric duplicate pairs is available at http://www.unm.edu/~compbio/Supplemental_Data/Sequence_Asymm.]

Article and publication are at http://www.genome.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gr.1252603.

References

- Adams, M.D., Celniker, S.E., Holt, R.A., Evans, C.A., Gocayne, J.D., Amanatides, P.G., Scherer, S.E., Li, P.W., Hoskins, R.A., Galle, R.F. et. al. 2000. The genome sequence of Drosophila melanogaster. Science 287: 2185–2195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennetzen, J.L. and Hall, B.D. 1982. Codon selection in yeast. Journal of Biological Chemistry 257: 3026–3031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The C. elegans Sequencing Consortium. 1998. Genome sequence of the nematode C. elegans: A platform for investigating biology. Science 282: 2012–2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherry, J.M., Adler, C., Ball, C., Chervitz, S.A., Dwight, S.S., Hester, E.T., Jia, Y., Juvik, G., Roe, T., Schroeder, M. et al. 1998. SGD: Saccharomyces Genome Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 26: 73–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conant, G.C. and Wagner, A. 2002. GenomeHistory: A software tool and its application to fully sequenced genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 30: 3378–3386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daffre, S., Kylsten, P., Samakovlis, C., and Hultmark, D. 1994. The lysozyme locus in Drosophila melanogaster: An expanded gene family adapted for expression in the digestive tract. Mol. Gen. Genet. 242: 152–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bono, M., Tobin, D.M., Davis, M.W., Avery, L., and Bargmann, C.I. 2002. Social feeding in Caenorhabditis elegans is induced by neurons that detect aversive stimuli. Nature 419: 899–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delattre, M. and Félix, M.-A. 2001. Microevolutionary studies in nematodes: A beginning. BioEssays 23: 807–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dermitzakis, E.T. and Clark, A.G. 2001. Differential selection after duplication in mammalian developmental genes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 18: 557–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fackenthal, J.D., Turner, F.R., and Raff, E.C. 1993. Tissue-specific microtubule functions in Drosophila spermatogenesis require the β2-tubulin isotype-specific carboxy terminus. Dev. Biol. 158: 213–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fackenthal, J.D., Hutchens, J.A., Turner, F.R., and Raff, E.C. 1995. Structural analysis of mutations in the Drosophila β2-tubulin isoform reveals regions in the β-tubulin molecule required for general and for tissue-specific microtubule functions. Genetics 139: 267–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fay, J.C., Wycoff, G.J., and Wu, C.-I. 2002. Testing the neutral theory of molecular evolution with genomic data from Drosophila. Nature 415: 1024–1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein, J. 1981. Evolutionary trees from DNA sequences: A maximum likelihood approach. J. Mol. Evol. 17: 368–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The FlyBase Consortium. 2002. The FlyBase database of the Drosophila genome projects and community literature. Nucleic Acids Res. 30: 106–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Force, A., Lynch, M., Pickett, F.B., Amores, A., Yan, Y., and Postlethwait, J. 1999. Preservation of duplicate genes by complementary, degenerative mutations. Genetics 151: 1531–1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraenkel, D.G. 1982. Carbohydrate metabolism. In The molecular biology of the yeast Saccharomyces: Metabolism and gene expression, (eds. J.N. Strathern, E.W. Jones, and J.R. Broach), pp. 1–37. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- Gasch, A.P., Spellman, P.T., Kao, C.M., Carmel-Harel, O., Eisen, M.B., Storz, G., Botstein, D., and Brown, P.O. 2000. Genomic expression programs in the response of yeast cells to environmental change. Mol. Biol. Cell 11: 4241–4257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, T.J. and Spring, J. 1998. Genetic redundancy in vertebrates: Polyploidy and persistence of genes encoding multidomain proteins. Trends Genet. 14: 46–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffeau, A., Barrell, B.G., Bussey, H., Davis, R.W., Dujon, B., Feldmann, H., Galibert, F., Hoheisel, J.D., Jacq, C., Johnston, M. et al. 1996. Life with 6000 genes. Science 274: 546–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman, N. 1993. Statistical tests of models of DNA substitution. J. Mol. Evol. 36: 182–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman, N. and Yang, Z. 1994. A codon-based model of nucleotide substitution for protein-coding DNA sequences. Mol. Biol. Evol. 11: 725–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillis, D.M., Moritz, C., and Mable, B.K. 1996. Molecular Systematics, 2nd ed. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA.

- Holland, P.W.H. 1999. Gene duplication: Past, present and future. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 10: 541–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle, H.D. and Raff, E.C. 1990. Two Drosophila β-tubulin isoforms are not functionally equivalent. J. Cell Biol. 111: 1009–1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, M.K. and Hughes, A.L. 1993. Evolution of duplicate genes in a tetraploid animal, Xenopus laevis. Mol. Biol. Evol. 10: 1360–1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, A.L., Green, J.A., Garbayo, J.M., and Roberts, R.M. 2000a. Adaptive diversification within a large family of recently duplicated, placentally expressed genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 97: 3319–3323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, T.R., Marton, M.J., Jones, A.R., Roberts, C.J., Stoughton, R., Armour, C.D., Bennett, H.A., Coffey, E., Dai, H.Y., He, Y.D.D. et al. 2000b. Functional discovery via a compendium of expression profiles. Cell 102: 109–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito, T., Chiba, T., Ozawa, R., Yoshida, M., Hattori, M., and Sakaki, Y. 2001. A comprehensive two-hybrid analysis to explore the yeast protein interactome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 98: 4569–4574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamath, R.S., Fraser, A.G., Dong, Y., Poulin, G., Durbin, R., Gotta, M., Kanapin, A., Le Bot, N., Moreno, S., Sohrmann, M. et al. 2003. Systematic functional analysis of the Caenorhabditis elegans genome using RNAi. Nature 421: 231–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.K., Lund, J., Kiraly, M., Duke, K., Jiang, M., Stuart, J.M., Eizinger, A., Wylie, B.N., and Davidson, G.S. 2001. A gene expression map for Caenorhabditis elegans. Science 293: 2087–2092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimbel, M., Incardona, J.P., and Raff, E.C. 1989. A variant β-tubulin isoform of Drosophila melanogaster (β3) is expressed primarily in tissues of mesodermal origin in embryos and pupae, and is utilized in populations of transient microtubules. Dev. Biol. 131: 415–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kipreos, E.T. and Pagano, M. 2000. The F-box protein family. Genome Biol. 1: reviews3002.1–3002.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondrashov, F.A., Rogozin, I.B., Wolf, Y.I., and Koonin, E.V. 2002. Selection in the evolution of gene duplicates. Genome Biol. 3: 0008.1–0008.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krakauer, D.C. and Nowak, M.A. 1999. Evolutionary preservation of redundant duplicated genes. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 10: 555–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A., Agarwal, S., Heyman, J.A., Matson, S., Heidtman, M., Piccirillo, S., Umansky, L., Drawid, A., Jansen, R., Liu, Y., et al. 2002. Subcellular localization of the yeast proteome. Genes Dev. 16: 707–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kylsten, P., Kimbrell, D.A., Daffre, S., Samakovlis, C., and Hultmark, D. 1992. The lysozyme locus in Drosophila melanogaster: Different genes are expressed in midgut and salivary glands. Mol. Gen. Genet. 232: 335–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langkjær, R.B., Cliften, P.F., Johnston, M., and Piskur, J. 2003. Yeast genome duplication was followed by asynchronous differentiation of duplicated genes. Nature 421: 848–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, P.O. 2001. Phylogenetic systematics turns over a new leaf. Trends Ecol. Evol. 16: 30–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.-H. 1997. Molecular evolution. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA.

- ____. 1980. Rate of gene silencing at duplicate loci: A theoretical study and interpretation of data from tetraploid fish. Genetics 95: 237–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.-J., and Tsoi, S.C.-M. 2002. Phylogenetic analysis of vertebrate lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) multigene families. J. Mol. Evol. 54: 614–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liò, P. and Goldman, N. 1998. Models of molecular evolution and phylogeny. Genome Res. 8: 1233–1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews, C.K. and Van Holde, K.E. 1996. Biochemistry. The Benjamin/Cummings Publishing Company Inc., Menlo Park, CA.

- Menzel, R., Bogaert, T., and Achazi, R. 2001. A systematic gene expression screen of Caenorhabditis elegans cytochrome P450 genes reveals CYP35 as strongly xenobiotic inducible. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 395: 158–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muse, S.V. and Gaut, B.S. 1994. A likelihood approach for comparing synonymous and nonsynonymous nucleotide substitution rates, with application to the chloroplast genome. Mol. Biol. Evol. 11: 715–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muse, S.V. and Weir, B.S. 1992. Testing for equality of evolutionary rates. Genetics 132: 269–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muzzarelli, R.A.A. and Muzzarelli, C. 1998. Native and modified chitins in the biosphere. In Nitrogen-containing macromolecules in the bio- and geosphere (ed. P.F. van Bergen), pp. 148–162. American Chemical Society, Washington, DC.

- Nei, M. and Roychoudhury, A.K. 1973. Probability of fixation of nonfunctional genes at duplicate loci. Am. Nat. 107: 362–372. [Google Scholar]

- Nurminsky, D.I., Nurminskaya, M.V., De Aguiar, D., and Hartl, D.L. 1998. Selective sweep of a newly evolved sperm-specific gene in Drosophila. Nature 396: 572–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno, S. 1970. Evolution by gene duplication. Springer, New York.

- Ota, T. and Nei, M. 1994. Estimation of the number of amino acid substitutions per site when the substitution rate varies among sites. J. Mol. Evol. 38: 642–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilgrim, D. and Young, E.T. 1987. Primary structure requirements for correct sorting of the yeast mitochondrial protein ADH III to the yeast mitochondrial matrix space. Mol. Cell. Biol. 7: 294–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regel, R., Matioli, S.R., and Terra, W.R. 1998. Molecular adaptation of Drosophila melanogaster lysozymes to a digestive function. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 28: 309–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon, J.M. and Sternberg, P.W. 2002. Evidence of a mate-finding cue in the hermaphrodite nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 99: 1598–1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, N.G.C. and Eyre-Walker, A. 2002. Adaptive protein evolution in Drosophila. Nature 415: 1022–1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokal, R.R. and Rohlf, F.J. 1995. Biometry, 3rd ed. W.H. Freeman and Company, New York.

- Spellman, P.T., Sherlock, G., Zhang, M.Q., Iyer, V.R., Anders, K., Eisen, M.B., Brown, P.O., Botstein, D., and Futcher, B. 1998. Comprehensive identification of cell-cycle-regulated genes of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae by microarray hybridization. Mol. Biol. Cell 9: 3273–3297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein, L., Sternberg, P., Durbin, R., Thierry-Mieg, J., and Spieth, J. 2001. WormBase: Network access to the genome and biology of Caenorhabditis elegans. Nucleic Acids Res. 29: 82–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, J.D., Higgins, D.G., and Gibson, T.J. 1994. CLUSTAL W: Improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, positions-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22: 4673–4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsaur, S.C., Ting, C.T., and Wu, C.I. 1998. Positive selection driving the evolution of a gene of male reproduction, Acp26aa, of Drosophila: II. Divergence versus polymorphism. Mol. Biol. Evol. 15: 1040–1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uetz, P., Giot, L., Cagney, G., Mansfield, T.A., Judson, R.S., Knight, J.R., Lockshon, D., Narayan, V., Srinivasan, M., Pochart, P., et al. 2000. A comprehensive analysis of protein–protein interactions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature 403: 623–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van de Peer, Y., Taylor, J.S., Braasch, I., and Meyer, A. 2001. The ghost of selection past: Rates of evolution and functional divergence of anciently duplicated genes. J. Mol. Evol. 53: 436–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, A. 2000. Decoupled evolution of coding region and mRNA expression patterns after gene duplication: Implications for the neutralist-selectionist debate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 97: 6579–6584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, A. 2002. Asymmetric functional divergence of duplicate genes in yeast. Mol. Biol. Evol. 19: 1760–1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood, V., Gwilliam, R., Rajandream, M.A., Lyne, M., Lyne, R., Stewart, A., Sgouros, J., Peat, N., Hayles, J., Baker, S., et al. 2002. The genome sequence of Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Nature 415: 871–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyckoff, G.J., Wang, W., and Wu, C.-I. 2000. Rapid evolution of male reproductive genes in the descent of man. Nature 403: 304–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.Z., Rosenberg, H.F., and Nei, M. 1998. Positive Darwinian selection after gene duplication in primate ribonuclease genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 95: 3708–3713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]