Abstract

In mammals, a subset of retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) expresses the photopigment melanopsin, which renders them intrinsically photosensitive (ipRGCs). These ipRGCs mediate various non-image-forming visual functions such as circadian photoentrainment and the pupillary light reflex (PLR). Melanopsin phototransduction begins with activation of a heterotrimeric G protein of unknown identity. Several studies of melanopsin phototransduction have implicated a G-protein of the Gq/11 family, which consists of Gna11, Gna14, Gnaq and Gna15, in melanopsin-evoked depolarization. However, the exact identity of the Gq/11 gene involved in this process has remained elusive. Additionally, whether Gq/11 G-proteins are necessary for melanopsin phototransduction in vivo has not yet been examined. We show here that the majority of ipRGCs express both Gna11 and Gna14, but neither Gnaq nor Gna15. Animals lacking the melanopsin protein have well-characterized deficits in the PLR and circadian behaviors, and we therefore examined these non-imaging forming visual functions in a variety of single and double mutants for Gq/11 family members. All Gq/11 mutant animals exhibited PLR and circadian behaviors indistinguishable from WT. In addition, we show persistence of ipRGC light-evoked responses in Gna11−/−; Gna14−/− retinas using multielectrode array recordings. These results demonstrate that Gq, G11, G14, or G15 alone or in combination are not necessary for melanopsin-based phototransduction, and suggest that ipRGCs may be able to utilize a Gq/11-independent phototransduction cascade in vivo.

Introduction

Intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells (ipRGCs) comprise a distinct subset of retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) and express the photopigment melanopsin (Opn4) [1]. ipRGCs constitute the sole conduit of light information from the retina to non-image forming visual centers in the brain and are responsible for driving a variety of behaviors [2], [3]. These behaviors include circadian photoentrainment, which is the process by which the circadian clock is aligned to the environmental light-dark cycle, and the pupillary light reflex (PLR), in which the area of the pupil changes in response to changes in light intensity.

Despite the well-established role for ipRGCs and melanopsin in the regulation of non-image forming visual functions, little is known about the molecular components of melanopsin phototransduction. Previous research has suggested that ipRGCs likely utilize a phototransduction pathway similar to that used in Drosophila microvillar photoreceptors [1], [4], in which the activated opsin stimulates a Gq/11 protein. In Drosophila, the α-subunit of the Gq/11 protein activates phospholipase C-β (PLC-β), which results in the opening of TRP and TRPL channels allowing Na+ and Ca2+ to flow into the cell resulting in depolarization of the rhabdomere in response to light [5], [6].

Homologs of the components of the Drosophila phototransduction pathway are found in mice. Specifically, there are four Gq/11 genes (Gnaq, Gna11, Gna14, and Gna15), four Plc-β genes (Plc-β1 – 4), and seven Trpc channel genes (Trpc1-7). The tandemly duplicated Gna15 and Gna11 genes are linked to mouse chromosome 10 [7], [8], and Gnaq and Gna14 colocalize to mouse chromosome 19 [9]. To date, there have been several electrophysiological studies implicating Gq/11, Plc-β, and TrpC genes in ipRGC phototransduction [4], [10], [11]. However, there have been no functional studies investigating the identity of the Gq/11 protein utilized by melanopsin in vivo or any studies of the effects of the loss of any presumptive ipRGC phototransduction genes on behavior. In this study, we sought to determine the identity(ies) of the Gq/11 protein(s) utilized for melanopsin phototransduction in vivo.

We performed single-cell RT-PCR on individual ipRGCs to determine which of the genes were expressed in ipRGCs and if there was heterogeneity in their expression among the ipRGC population. Similar to previous studies, we found that the majority of ipRGCs express both Gna11 and Gna14, but not Gnaq or Gna15. Since loss of the melanopsin protein results in well-characterized deficits in the pupillary light reflex and circadian behaviors, we examined these non-imaging forming visual functions in Gna11−/−; Gna14−/− (Gna11; Gna14 DKO) mice and Gnaqflx/flx; Gna11−/−; Opn4Cre/+ (Gnaq; Gna11 DKO) mice as well as several single Gq/11 gene knockouts [9], [12]–[14]. All genotypes examined exhibited non-image forming visual functions indistinguishable from WT. Furthermore, multielectrode array recordings revealed no deficits in ipRGC light responses in Gna11; Gna14 DKO animals. Contrary to previous work, this study indicates that ipRGCs may be able to utilize a Gq/11-independent phototransduction cascade in vivo.

Results

Gna11 and Gna14 are expressed in ipRGCs

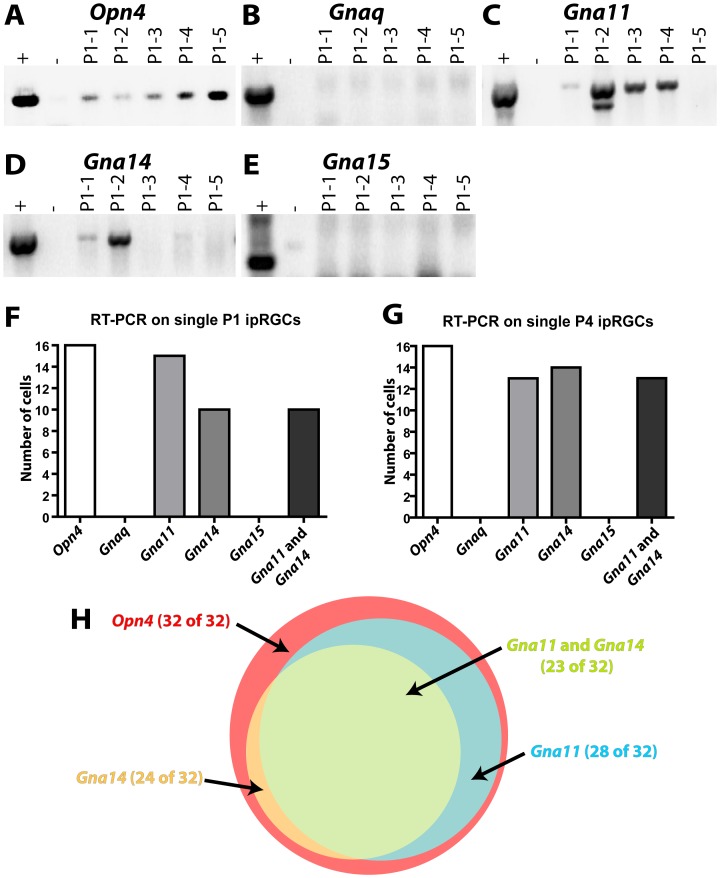

Previous reports have shown that Gq/11 genes are expressed in ipRGCs. However, there has been disagreement regarding which Gq/11 genes are actually expressed, with one study reporting heterogeneous expression of each of the four Gq/11 genes and another reporting primarily Gna14 and some Gna11 expression [4], [15]. We therefore sought to definitively identify which Gq/11 genes are expressed in ipRGCs. We isolated individual ipRGCs by dissociating retinas of Opn4Cre/+ Z/EG mice, in which ipRGCs ipRGCs are labeled with GFP, and picking individual ipRGCs with a microneedle. We specifically chose to utilize retinas from P1 and P4 mice since there is GFP labeling of some cones in adult Opn4Cre/+ Z/EG mice [16]. By RT-PCR, we confirmed that the 32 isolated cells expressed melanopsin (Figure 1A, F–H), and then screened those 32 melanopsin-expressing cells for the four Gq/11 genes (Figure 1B–H). 23 of the 32 ipRGCs expressed both Gna11 and Gna14, and an additional 6 cells expressed either Gna11 or Gna14 (Figure 1F–H). Neither Gnaq nor Gna15 were detected in any of the melanopsin-expressing cells, and 3 melanopsin-expressing cells had no detectable levels of any Gq/11 gene (Figure 1F–H).

Figure 1. Gna11 and Gna14 are expressed in ipRGCs, often in combination.

A–E. Representative images of RT-PCR analysis of single ipRGCs for Opn4, Gnaq, Gna11, Gna14, and Gna15. All representative gels show RT-PCR analysis of single ipRGCs taken from P1 Opn4Cre/+; Z/EG mice. Each lane represents one cell, the positive control is whole retinal RNA, and the negative control is water. F–G Summary of expression of Gq/11 family members in the 16 ipRGCs obtained from P1 and P4 Opn4Cre/+; Z/EG mice. All cells expressed melanopsin. 15 cells expressed Gna11, 10 of which also expressed Gna14. H. Venn diagram showing the distribution of Gq/11 family member expression in all 32 ipRGCs sampled.

Loss of Gq/11 genes does not affect non-image forming visual functions

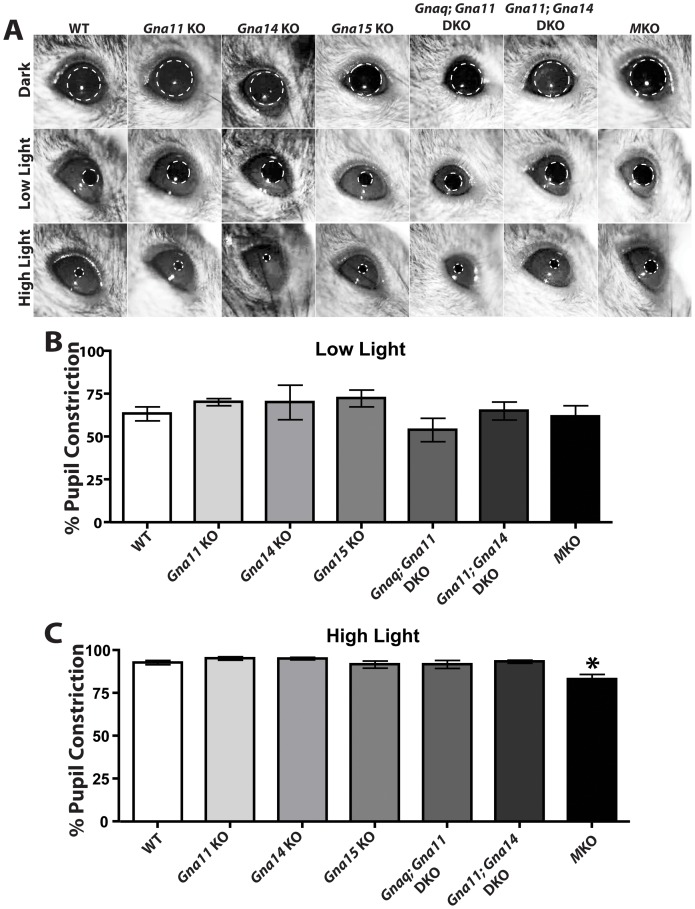

Mice that lack melanopsin phototransduction due to loss of melanopsin have several well characterized deficits in non-image forming visual behaviors including defects in the PLR at high light intensities and a deficit in circadian period lengthening in response to constant light. Since Gna11 and Gna14 were the only Gq/11 genes identified as being expressed in ipRGCs and nearly all cells tested expressed at least one, we produced Gna11−/−; Gna14−/− (Gna11; Gna14 DKO) mice from previously published single knockouts [14], [17], [18]. We recorded the pupillary light reflex of 4–6 month old WT (n = 16), Opn4LacZ/LacZ (MKO; n = , 7), Gna11−/− (Gna11 KO; n = 4), Gna14−/− (Gna14 KO; n = 5), Gna15−/− (Gna15 KO; n = 7), Gnaqflx/flx; Gna11−/−; Opn4Cre/+ (Gnaq; Gna11 DKO; n = 9), and Gna11−/−; Gna14−/− (Gna11; Gna14 DKO; n = 7) at both low and high light intensities (Figure 2). Consistent with previous studies [19], MKOs exhibited deficits at high light intensities. Surprisingly, all mice mutant for Gq/11 genes were indistinguishable from WT animals at both low and high light intensities (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Gq/11 mutant lines exhibit pupillary light reflex indistinguishable from WT.

A. Representative images of the pupil constriction in WT (16 animals), Opn4LacZ/LacZ (MKO, 7 animals), Gna11−/− (Gna11 KO, 4 animals), Gna14−/− (Gna14 KO, 5 animals), Gna15−/− (Gna15 KO, 7 animals), Gnaqflx/flx; Gna11−/−; Opn4Cre/+ (Gnaq; Gna11 DKO, 9 animals), and Gna11−/−; Gna14−/− (Gna11; Gna14 DKO, 7 animals) at both high (1.4×1016 photons/cm2/sec) and low (7.3×1013 photons/cm2/sec) light intensities. B–C. Quantification of the pupillary light reflex at low (7.3×1013 photons/cm2/sec) and high (1.4×1016 photons/cm2/sec) light intensities. All animals exhibited pupillary light reflex indistinguishable from WT. One-way ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc analysis. Error bars represent s.e.m.

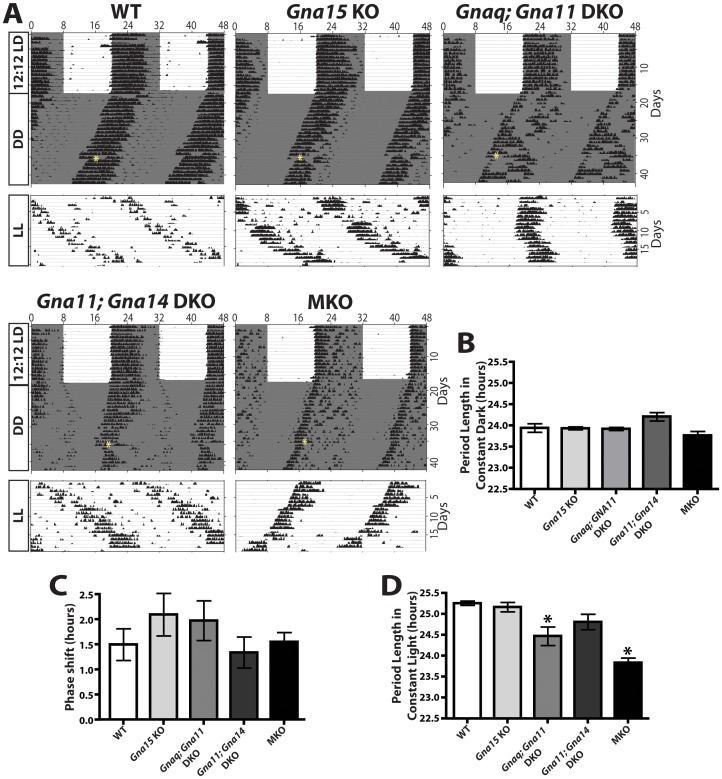

We also recorded wheel-running activity in 4–6 month old WT (n = 14), MKO (n = 9), Gna15 KO (n = 7), Gnaq; Gna11 DKO (n = 8), and Gna11; Gna14 DKO (n = 7) mice to measure the daily activity rhythms of these mice (Figure 3). We conducted these measurements under three different conditions: a 12∶12 light/dark cycle, constant darkness, and constant light. We also administered a 15-minute light pulse in constant darkness to determine the amplitude of the light-evoked circadian phase shifts in each mouse line. All genotypes were able to photoentrain to the 12∶12 light/dark cycle. All mutant lines exhibited a normal circadian period under constant darkness (WT: 23.85±0.36 hours, MKO: 23.68±0.26 hours, Gna15 KO: 23.84±0.08 hours, Gnaq; Gna11 DKO: 23.83±0.10 hours, and Gna11; Gna14 DKO: 24.01±0.24 hours) (Figure 3A, B). All mice phase shifted normally to a light pulse presented at CT15. We observed no deficits in phase delay among any genotypes tested (WT: 1.40±0.78 hours, MKO: 1.45±0.49 hours, Gna15 KO: 1.96±1.04 hours, Gnaq; Gna11 DKO: 1.85±0.74 hours, and Gna11; Gna14 DKO: 1.25±0.65 hours) (Figure 3A,C). Melanopsin knockout animals have well-characterized deficits in circadian period lengthening under constant light [20] that we confirmed here (WT period: 25.08±0.17 hours, MKO period: 23.75±0.28 hours) (Figure 3A, D). In contrast, Gna15 KOs (24.99±0.28 hours) and Gna11; Gna14 DKOs (24.66±0.42 hours) were indistinguishable from WT mice. While Gnaq; Gna11 DKO animals (24.34±0.5 hours) did show a significantly shorter period than WT animals, the period was still significantly longer than MKO animals (Figure 3A, D).

Figure 3. Gq/11 mutant lines exhibit circadian behaviors indistinguishable from WT.

A. Representative actograms of wheel running activity from WT (14 animals), MKO (9 animals), Gna15 KO (7 animals), Gnaq; Gna11 DKO (8 animals), and Gna11; Gna14 DKO (7 animals) mice under a 12∶12 LD cycle, constant darkness, and constant light. The white background indicates light, grey background indicates darkness, and the yellow asterisk indicates a 15-minute light pulse at circadian time (CT) 15. All mice photoentrained to the LD cycle. B. Quantification of free-running period under constant dark conditions. All animals exhibited circadian periods indistinguishable from WT. One-way ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc analysis. Error bars represent s.e.m. C. Quantification of phase shifting to a 15-minute light pulse given at CT 15. All animals exhibited phase shifting indistinguishable from WT. One-way ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc analysis. Error bars represent s.e.m. D. Quantification of free running period under constant light. As previously reported, MKO mice exhibited reduced lengthening of their circadian period under constant light conditions. Gnaq; Gna11 DKO exhibited a slight reduction in the lengthening of their circadian period in constant light, and their period length was significantly different from both WT and MKO. Gna15 KO and Gna11; Gna14 DKO exhibited lengthened periods that were indistinguishable from WT. One-way ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc analysis. Error bars represent s.e.m.

ipRGC light responses persist in Gna11; Gna14 double knockouts

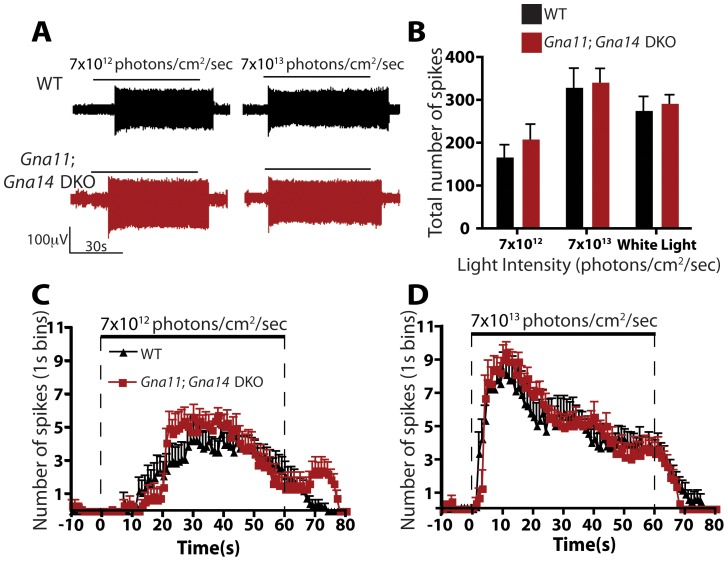

The lack of behavioral deficits in Gq/11 mutant animals led us to examine whether melanopsin phototransduction is perturbed at the cellular level in these lines. We therefore examined the light responses of ipRGCs in isolated retinas of WT and Gna11; Gna14 DKO mice using multielectrode array (MEA) recordings. We recorded from retinas of postnatal day 3 mice, since it has been shown that outer retinal signaling to ganglion cells is not present at early postnatal ages [21], and thus ipRGCs constitute the only light-responsive ganglion cells at this age [22], [23]. Nonetheless, to guarantee that all detected light responses were from ipRGCs, we included a cocktail of synaptic blockers in the Ames' medium to inhibit any glutamatergic, GABAergic, and glycinergic signaling to ipRGCs. Additionally, we included cholinergic blockers to minimize interference from retinal waves present at this developmental stage [24]. Retinas were dark adapted for at least 20 min and then stimulated with diffuse, uniform light of both low (7×1012 photons/cm2 · sec) and high light intensity (7×1013 photons/cm2 · sec) for 60 sec at 480 nm, the peak wavelength for melanopsin activation [25], [26]. We also stimulated the retinas with bright white light (267 mW/cm2). The retinas were allowed to readapt to dark for 5 min between stimulations. Figure 4A shows representative voltage traces of typical ipRGCs in WT and Gna11; Gna14 DKO mice at both low and high light intensity. We found that Gna11; Gna14 DKO ipRGCs were indistinguishable from the WT controls. ipRGCs in both WT and Gna11; Gna14 DKO mice responded to increasing light intensities with increased spiking (Figure 4B) that reached maximum levels several seconds following light onset. After light offset, ipRGCs continued to spike for as long as 20 seconds (Figure 4A, C, D). These slow dynamics are consistent with previous descriptions of melanopsin-dependent light responses [23], [27]–[29]. These data show that despite the fact that Gna11 and Gna14 were the only Gq/11 genes expressed in ipRGCs, they are not required for melanopsin phototransduction.

Figure 4. ipRGC intrinsic phototransduction persists in Gna11; Gna14 DKO mice.

A. Representative voltage traces for ipRGC intrinsic light responses in WT and Gna11; Gna14 DKO retinas at two 480 nm light intensities (7×1012 and 7×1013 photons/cm2/sec). Horizontal bar represents light stimulation (60 sec). Vertical scale bar is 100 µV. B. Total number of spikes in ipRGCs light responses to two 480 nm light intensities (7×1012 and 7×1013 photons/cm2/sec) and white light (267 mW/cm2). ipRGC light responses in Gna11; Gna14 DKO were indistinguishable from WT. Student's t-test. Error bars represent s.e.m. C–D. Quantification of the number of spikes, in 1 second bins, during a 60 second pulse of either 7×1012 photons/cm2/sec or 7×1013 photons/cm2/sec 480 nm light. Photoresponses in Gna11; Gna14 DKO mice were indistinguishable from WT. Student's t-test. Error bars represent s.e.m.

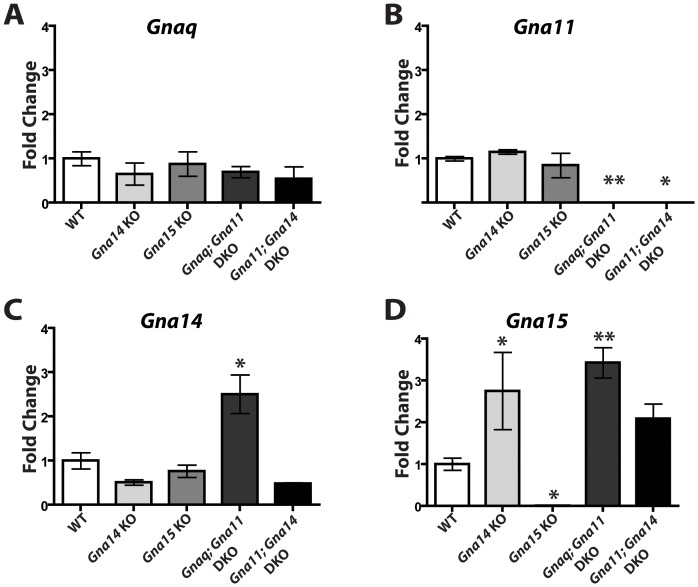

Other Gq/11 genes are up-regulated in single and double Gq/11 knockouts

Since Gna11 and Gna14 were the only Gq/11 genes detected in ipRGCs, we were surprised that Gna11; Gna14 DKO mice did not recapitulate any of the phenotypes observed in melanopsin knockout animals. To test whether removal of one or two Gq/11 genes results in upregulation of other Gq/11 family members, we performed quantitative RT-PCR on RNA extracted from the retinas of mutant mice (Figure 5). We measured the mRNA levels of Gnaq, Gna11, Gna14, and Gna15 in WT, Gna14 KO, Gna15 KO, Gnaq; Gna11 DKO, and Gna11; Gna14 DKO mice. We found that all animals had levels of Gnaq mRNA that were indistinguishable from WT (Figure 5A). It is important to note that in Gnaq; Gna11 DKOs, Gnaq is conditionally knocked-out in ipRGCs (Gnaqflx/flx; Gna11−/−; Opn4Cre/+); therefore, we did not expect a significant reduction in whole retinal Gnaq mRNA in these mutants. Gna14 KOs and Gna15 KOs exhibited normal levels of Gna11 mRNA, while, Gnaq; Gna11 DKOs, and Gna11; Gna14 DKOs had undetectable levels (Figure 5B). Levels of Gna14 mRNA were reduced in Gna14 KOs and Gna11; Gna14 DKOs, but increased in Gnaq; Gna11 DKOs (Figure 5C). Gna14 mRNA levels are not abolished in Gna14 KOs and Gna11; Gna14 DKOs because the Gna14 KO line was created by knocking a neo cassette into exon 3 of the gene. This removes part of exon 3 and results in a frameshift. Thus, while, mRNA is still produced from the Gna14 locus in Gna14 KOs, it encodes a nonsense protein. Additionally, as indicated by the reduced mRNA levels, the mutant transcript is degraded. Gna15 mRNA was undetectable in Gna15 KOs, but increased in Gna14 KOs, Gnaq; Gna11 DKOs, and Gna11; Gna14 DKOs (Figure 5D). These data indicate there is upregulation of other Gq/11 genes in some Gq/11 knockout lines; however, it remains unknown whether the upregulation occurs in ipRGCs and if such upregulation would be sufficient to drive melanopsin phototransduction.

Figure 5. Gq/11 family members are upregulated in the retinas of some Gq/11 mutant lines.

A–D. Expression levels of Gnaq, Gna11, Gna14, and Gna15 in the retina relative to WT in Gna14 KO, Gna15 KO, Gnaq; Gna11 DKO, and Gna11; Gna14 DKO mice. Normalized to levels of 18S RNA. (N = 3 mice for each; 2 retinas per RNA sample). * indicates P<0.05 by one-way ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc analysis. Error bars represent s.e.m.

Discussion

In this study, we provide the first investigation of the melanopsin phototransduction pathway in vivo. We determined that genetic inactivation of the Gq/11 proteins that are normally expressed in ipRGCs does not abolish melanopsin–dependent behaviors or electrophysiological responses. Specifically, we found that no tested Gq/11 knockout line exhibited the behavioral deficits observed in melanopsin knockout mice. All tested Gq/11 mutant lines exhibited circadian behaviors and pupillary light reflexes that were indistinguishable from WT mice. Additionally, using single-cell RT-PCR for Gq/11 genes in ipRGCs, we found only expression of Gna11 and Gna14, often expressed together. However, using multielectrode array we detected no changes in intrinsic light responses of ipRGCs in Gna11; Gna14 DKO compared to WT controls.

Previous reports have shown expression of Gq/11 genes in ipRGCs although there were inconsistencies as to which Gq/11 genes were detected [4], [15]. Specifically, in Graham et al. the authors used single cell RT-PCR and determined that expression of all four Gq/11 genes can be detected in ipRGCs, although expression was heterogeneous among the cells sampled and Gna14 was detected in the majority of cells [4]. Siegert et al. examined ipRGCs as a population and reported expression of Gna11 and Gna14 [15], which is consistent with our findings here. However, neither of these studies investigated the function of ipRGCs in the absence of any of these specific genes and in fact Siegert et al. observed the expression of other heterotrimeric G proteins [15].

Electrophysiological investigations of ipRGC phototransduction have supported the involvement of the Gq/11 pathway. Specifically, Xue et al. showed that melanopsin phototransduction is substantially reduced in the absence of Plc-β4 [10]. In agreement with work from Perez-Leighton et al., Xue and co workers additionally showed that loss of both Trpc6 and 7 virtually abolished the melanopsin-dependent photoresponse suggesting that Trpc6 and 7 function in a combinatorial fashion [10], [11]. Since Gq/11 family members are defined based on their ability to activate PLC, it is reasonable to predict that if Plc-β is a critical component of melanopsin phototransduction then there must also be a member of Gq/11 family involved. This prediction was supported with the use of pharmacological inhibitors of the Gq/11 family on dissociated ipRGCs [4]. However, here, we show that in vivo, mice mutant for Gq/11 family members do not exhibit the behavioral deficits indicative of a loss of melanopsin-dependent light responses.

Several possibilities exist to explain these discrepancies. One is that Gq/11 signaling is not required for melanopsin phototransduction. Siegert et al. observed expression of other heterotrimeric G proteins [15] and thus melanopsin could activate a Gi or Go protein, as has been observed in vitro [30], the dissociation of which could result in the beta/gamma subunit activating PLC-β4 as has been observed with PLC-β1 and 3 [31]. Another possibility is that there is compensatory upregulation from other remaining Gq/11 family members in the tested mutant lines. Our data supports this possibility since Gna14 and Gna15 were upregulated in Gnaq; Gna11 DKOs. Also, Gna15 was upregulated in Gna14 knockouts; although, the increase in Gna15 expression was not significant in Gna11; Gna14 DKOs. However, our qRT-PCR experiments were performed on whole retinal RNA, and expression of Gna15 has not consistently been reported in ipRGCs. Thus, it is unknown whether there is ectopic expression of Gna15 in ipRGCs in Gq/11 knockout lines. Whether other Gq/11 family members are upregulated in the conventional Gq knockout lines could be investigated by creating a mouse line that has all four Gq/11 genes knocked-out in ipRGCs. Due the fact that Gq/11 genes exist as two closely linked pairs on two single chromosomes, this quadruple knockout will require creation of a new mutant line in which the linked genes are knockout together. This mouse line would definitively reveal the contribution of the Gq/11 class alpha subunits to the melanopsin phototransduction cascade.

Additionally, it remains possible that Gna11 and Gna14 are required for the activation PLC-β4 and TRPC6/7, but this pathway is not required for normal ipRGC-mediated behavior. In support of this idea, a small residual light-activated current exist in Plc-β4−/− and Trpc6/7−/− ipRGCs [10]. Importantly, voltage recordings were not performed in these mutants. Therefore, it remains possible that this small residual current is sufficient to drive spiking in ipRGCs, which then drives normal non-image-forming visual behaviors. To test this, behavioral assays need to be performed on Plc-β4−/− and Trpc6/7−/− mice.

It is important to note that ipRGCs are not a homogeneous population and ipRGC subtypes (termed M1–M5) have stereotyped yet distinct electrophysiological light responses. Thus, it is possible there is variability in the components of the melanopsin phototransduction cascade among ipRGC subtypes. The study showing that ipRGCs have a severe reduction in their intrinsic light responses in mouse lines mutant for Trpc6 and -7 channel genes and Plc-β4 [10] only examined the M1 ipRGC subtype, and in Trpc6 mutant mice, both M1 and M2 ipRGCs show some deficits in melanopsin-dependent light responses [11]. While M1 ipRGCs are the predominant subtype mediating circadian behaviors, non-M1 ipRGCs may contribute to the PLR [16]. It remains unknown whether the intrinsic responses of other ipRGC subtypes are affected in Trpc6 and Trpc7 double knockouts or in Plc-β4 knockouts. Because we picked single cells for RT-PCR at a developmental time, we could not be certain whether we were picking M1 or non-M1 ipRGCs. A careful analysis of the phototransduction in M1 versus non-M1 ipRGCs has interesting functional and evolutionary implications.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Statement

All protocols, animal housing, and treatment conditions were approved by the Johns Hopkins University Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

Animal Models

All mice were of a mixed background (C57BL/6;129SvJ). Melvin Simon at University of California San Diego generously provided Gnaqflx/flx; Gna11−/− animals and Gna14−/− animals [13], [14], [17], and Thomas Wilkie at University of Texas Southwestern generously provided Gna15−/− animals [12]. Gnaqflx/flx; Gna11−/− animals were crossed into our Opn4Cre/+ line to produce Opn4Cre/+; Gnaqflx/flx; Gna11−/− mice. Gnaqflx/flx; Gna11−/− mice were also crossed with Gna14−/− mice to produce Gna11−/−; Gna14−/− animals.

Single Cell RT-PCR

Single ipRGCs were isolated from Opn4Cre/+; Z/EG mice following the protocol described in [32]. Reverse transcription of the RNA from single cells from P1 and P4 retinas, and amplification of the cDNA was performed as described in [32]. The following primers were designed to amplify from the 3′ end of the transcript and used to detect phototransduction components in the resulting amplified cDNA obtained from single ipRGCs: Melanopsin (F: CTTTGCTGGATACTCGCACA; R: CAGGCACCTTGGGAGTCTTA), Gnaq (F: GTTCGAGTCCCCACTACAGG; R: GGTTCAGGTCCACGAACATT), Gna11 (F: GTACCCGTTTGACCTGGAGA; R: AGGATGGTGTCCTTCACAGC), Gna14 (F: CCATTCGACCTGGAAAACAT; R: CAGCAAACACAAAGCGGATA), Gna15 (F: TGAGCGAGTATGACCAGTGC, R: CAGGTTGATCTCGTCCAGGT).

Pupillometry

Pupil experiments were performed on unanesthetized mice that were restrained by hand. WT (16 animals), MKO (7 animals), Gna11 KO (4 animals), Gna14 KO (5 animals), Gna15 KO (7 animals), Gnaq; Gna11 DKO (9 animals), and Gna11; Gna14 DKO (7 animals) were kept on a 12 hour∶12 hour light∶dark cycle and given at least 30 minutes to dark-adapt between stimulations. All experiments were performed during the animals' day (ZT2-10). The contralateral eye was stimulated with 474-nm LED light for 30–60 s. Neutral density filters were interposed in the light path to modulate light intensity and light intensity was measured using a photometer (Solar Light). High light indicates 1.4×1016 photons/cm2/sec, and low light indicates 7.3×1013 photons/cm2/sec.

Wheel Running Behavior

Mice were placed in cages with a 4.5-inch running wheel, and their activity was monitored with VitalView software (Mini Mitter), and cages were changed at least every 2 weeks.

WT (14 animals), MKO (9 animals), Gna15 KO (7 animals), Gnaq; Gna11 DKO (8 animals), and Gna11; Gna14 DKO (7 animals) mice were placed in 12∶12 LD for 17 days followed by constant darkness for 26 days. For phase-shifting experiments, each animal was exposed to a light pulse (500 lux; CT15) for 15 min, after being in constant dark for 18 days. Following constant darkness, all mice were also placed in constant light (500 lux) for 18 days.

Quantification of circadian behavior

All free-running periods were calculated with ClockLab (Actimetrics) using the onsets of activity on days 10–17 of constant darkness similar to [3]. Phase shifts were calculated similar to [3] and described as follows: an onset for the day after the light pulse was predicted based on the onsets of the previous 7 days. Phase shifts were then determined based on the difference between the predicted onset and the shifted onset on the day after the light pulse. For all animals, the free-running period in constant light was measured with ClockLab (Actimetrics) using the onsets of activity on days 3–10 of constant light. Some animals (2 WT, 1 Gna15 KO, 2 Gnaq; Gna11 DKOs, 1 Gna11; Gna14 DKO, and 1 MKO) reduced their activity so much that an accurate period could not be measured and they were thus excluded.

Multielectrode Array Recordings

Multielectrode array recordings, light stimulation, and data analysis were performed as described in [11]. Briefly, retinas were dissected from P3 pups from WT and Gna11; Gna14 DKO animals and mounted ganglion cell side down on the array. Retinas were superfused with Ames' Medium (Sigma) and synaptic blocker cocktail oxygenated with 95%/5% Oxygen/CO2. Synaptic blocker cocktail consisted of: 250 µM DL-2-amino-4-phosphonobutyrate; 10 µM 6,7-dinitroquinoxaline (DNQX, α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid); 0.3 µM strychnine, 50 µM picrotoxin, and 10 nM (±)-epibatidine dihydrochloride. All reagents were purchased from Tocris (Ellesville, MO, USA). Spike sorting was performed using MCRack v 4.0.0 software (Multi Channel Systems)and analyzed offline with Offline Sorter v 2.8.6 software (Plexon Inc, Dallas, TX, USA).

Q-RT-PCR

Retinas were dissected from WT, Gna14 KO, Gna15 KO, Gnaq; Gna11 DKO, and Gna11; Gna14 DKO (N = 3 mice for each; 2 retinas per RNA sample). RNA was extracted from the retinas using an RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen; cat# 74106), and reverse transcription was performed using a RETROscript kit (Life Technology; cat # AM1710) and random hexamer primers. Quantitative PCR on the resulting cDNA was performed with SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Fermentas, cat# K0221), samples were analyzed in duplicate, and the levels were normalized to 18S RNA. The following primers were used: Gnaq (F: AATCATGTATTCCCACCTAGTCG; R: GGTTCAGGTCCACGAACATT), Gna11 (F: TCCTGCACTCACACTTGGTC; R: GGGTTCAGGTCCACAAACAT), Gna14 (F: TCACCTACCCCTGGTTTCTG; R: CCGCTTTGACATCTTGCTTT), Gna15 (F: ACCTCGGTCATCCTCTTCCT, R: CGCATACATGTCCAAGATGAA), and 18S RNA (F: CGCCGCTAGAGGTGAAATTC; R: TTGGCAAATGCTTTCGCTC).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Phyllis Robinson, David C. Martinelli, Diego Fernandez, and Justin Brodie-Kommit for their helpful suggestions on the manuscript. We would also like to thank Melvin Simon for the generous use of his Gna14−/− and Gnaqflx/flx; Gna11−/− mutant lines.

Funding Statement

Funding provided by National Institutes of Health Grant: 1R01EY019053, National Institutes of Health Grant: GM076430. Publication of this article was funded in part by the Open Access Promotion Fund of the Johns Hopkins University Libraries. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Provencio I, Jiang G, De Grip WJ, Hayes WP, Rollag MD (1998) Melanopsin: An opsin in melanophores, brain, and eye. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 340–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hattar S, Lucas RJ, Mrosovsky N, Thompson S, Douglas RH, et al. (2003) Melanopsin and rod-cone photoreceptive systems account for all major accessory visual functions in mice. Nature 424: 76–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Güler AD, Ecker JL, Lall GS, Haq S, Altimus CM, et al. (2008) Melanopsin cells are the principal conduits for rod-cone input to non-image-forming vision. Nature 453: 102–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Graham DM, Wong KY, Shapiro P, Frederick C, Pattabiraman K, et al. (2008) Melanopsin ganglion cells use a membrane-associated rhabdomeric phototransduction cascade. Journal of Neurophysiology 99: 2522–2532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Huang J, Liu CH, Hughes SA, Postma M, Schwiening CJ, et al. (2010) Activation of TRP channels by protons and phosphoinositide depletion in Drosophila photoreceptors. Curr Biol 20: 189–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hardie RC (2001) Phototransduction in Drosophila melanogaster. J Exp Biol 204: 3403–3409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Davignon I, Barnard M, Gavrilova O, Sweet K, Wilkie TM (1996) Gene structure of murine Gna11 and Gna15: tandemly duplicated Gq class G protein alpha subunit genes. Genomics 31: 359–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wilkie TM, Scherle PA, Strathmann MP, Slepak VZ, Simon MI (1991) Characterization of G-protein alpha subunits in the Gq class: expression in murine tissues and in stromal and hematopoietic cell lines. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 88: 10049–10053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Offermanns S, Zhao LP, Gohla A, Sarosi I, Simon MI, et al. (1998) Embryonic cardiomyocyte hypoplasia and craniofacial defects in G alpha q/G alpha 11-mutant mice. EMBO J 17: 4304–4312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Xue T, Do MT, Riccio A, Jiang Z, Hsieh J, et al. (2011) Melanopsin signalling in mammalian iris and retina. Nature 479: 67–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Perez-Leighton CE, Schmidt TM, Abramowitz J, Birnbaumer L, Kofuji P (2011) Intrinsic phototransduction persists in melanopsin-expressing ganglion cells lacking diacylglycerol-sensitive TRPC subunits. Eur J Neurosci 33: 856–867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Davignon I, Catalina MD, Smith D, Montgomery J, Swantek J, et al. (2000) Normal hematopoiesis and inflammatory responses despite discrete signaling defects in Galpha15 knockout mice. Mol Cell Biol 20: 797–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wettschureck N, Rutten H, Zywietz A, Gehring D, Wilkie TM, et al. (2001) Absence of pressure overload induced myocardial hypertrophy after conditional inactivation of Galphaq/Galpha11 in cardiomyocytes. Nat Med 7: 1236–1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Offermanns S (2003) G-proteins as transducers in transmembrane signalling. Prog Biophys Mol Biol 83: 101–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Siegert S, Cabuy E, Scherf BG, Kohler H, Panda S, et al. (2012) Transcriptional code and disease map for adult retinal cell types. Nat Neurosci 15: 487–495, S481–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ecker JL, Dumitrescu ON, Wong KY, Alam NM, Chen S-K, et al. (2010) Melanopsin-expressing retinal ganglion-cell photoreceptors: cellular diversity and role in pattern vision. Neuron 67: 49–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Offermanns S (1999) New insights into the in vivo function of heterotrimeric G-proteins through gene deletion studies. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 360: 5–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dennis EA, Bradshaw RA (2011) Intercellular signaling in development and disease. Amsterdam; Boston: Academic Press. xvi, 532 p. p. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lucas RJ, Hattar S, Takao M, Berson DM, Foster RG, et al. (2003) Diminished pupillary light reflex at high irradiances in melanopsin-knockout mice. Science 299: 245–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ruby NF, Brennan TJ, Xie X, Cao V, Franken P, et al. (2002) Role of melanopsin in circadian responses to light. Science 298: 2211–2213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sernagor E, Eglen SJ, Wong RO (2001) Development of retinal ganglion cell structure and function. Prog Retin Eye Res 20: 139–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sekaran S, Lupi D, Jones SL, Sheely CJ, Hattar S, et al. (2005) Melanopsin-dependent photoreception provides earliest light detection in the mammalian retina. Curr Biol 15: 1099–1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tu DC, Zhang D, Demas J, Slutsky EB, Provencio I, et al. (2005) Physiologic diversity and development of intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells. Neuron 48: 987–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sun C, Speer CM, Wang GY, Chapman B, Chalupa LM (2008) Epibatidine application in vitro blocks retinal waves without silencing all retinal ganglion cell action potentials in developing retina of the mouse and ferret. J Neurophysiol 100: 3253–3263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Berson DM (2007) Phototransduction in ganglion-cell photoreceptors. Pflugers Arch 454: 849–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Do MT, Kang SH, Xue T, Zhong H, Liao HW, et al. (2009) Photon capture and signalling by melanopsin retinal ganglion cells. Nature 457: 281–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Berson DM, Dunn FA, Takao M (2002) Phototransduction by retinal ganglion cells that set the circadian clock. Science 295: 1070–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dacey DM, Liao H-W, Peterson BB, Robinson FR, Smith VC, et al. (2005) Melanopsin-expressing ganglion cells in primate retina signal colour and irradiance and project to the LGN. Nature 433: 749–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schmidt TM, Taniguchi K, Kofuji P (2008) Intrinsic and extrinsic light responses in melanopsin-expressing ganglion cells during mouse development. Journal of Neurophysiology 100: 371–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bailes HJ, Lucas RJ (2013) Human melanopsin forms a pigment maximally sensitive to blue light (lambdamax approximately 479 nm) supporting activation of G(q/11) and G(i/o) signalling cascades. Proc Biol Sci 280: 20122987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Park D, Jhon DY, Lee CW, Lee KH, Rhee SG (1993) Activation of phospholipase C isozymes by G protein beta gamma subunits. J Biol Chem 268: 4573–4576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Goetz JJ, Trimarchi JM (2012) Single-cell profiling of developing and mature retinal neurons. J Vis Exp. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]