Abstract

Recent studies have indicated that extranuclear or extracellular targets are important in mediating the bystander genotoxic effects of α-particles. In the present study, human–hamster hybrid (AL) cells were plated on either one or both sides of double-mylar dishes 2–4 days before irradiation, depending on the density requirement of experiments. One side (with or without cells) was irradiated with α-particles (from 0.1 to 100 Gy) using the track segment mode of a 4 MeV Van de Graaff accelerator. After irradiation, cells were kept in the dishes for either 1 or 48 h. The non-irradiated cells were then collected and assayed for both survival and mutation. When one side with cells was irradiated by α-particles (1, 10 and 100 Gy), the surviving fraction among the non-irradiated cells was significantly lower than that of control after 48 h co-culture. However, such a change was not detected after 1 h co-culture or when medium alone was irradiated. Furthermore, co-cultivation with irradiated cells had no significant effect on the spontaneous mutagenic yield of non-irradiated cells collected from the other half of the double-mylar dishes. These results suggested that irradiated cells released certain cytotoxic factor(s) into the culture medium that killed the non-irradiated cells. However, such factor(s) had little effect on mutation induction. Our results suggest that different bystander end points may involve different mechanisms with different cell types.

Keywords: Bystander effect, α-Particle irradiation, Double-mylar, Mutagenesis

1. Introduction

Over the past several years, considerable evidence has indicated that extranuclear and extracellular targets are also important in mediating the genotoxic effects of radiation [1–8]. When only a fraction of the cell population is irradiated by α-particles, biological effects, such as sister chromatid exchange [1,2], induction of micronuclei [3], gene mutation [4,5] and expression of certain stress-related genes [6,7] have been observed in a significantly higher proportion of cells than those that are actually traversed by an α-particle. These studies suggest that damage signals might be transmitted from irradiated to neighboring non-irradiated cells in the same population, leading to the induction of genetic changes among these bystander cells [5,7]. Alternatively, the bystander effects might be mediated by the release of cytokines or other soluble factors into the culture medium [8–10]. However, the exact mechanism(s) of the phenomenon is unclear.

Although cell–cell communication appears to play an important role in mediating the bystander effect [5,7], there is no evidence to rule out possible contributions from the transfers of soluble mediators generated in irradiated medium. It is most likely that multiple mechanisms are involved in bystander effects. Previous studies using medium transferred have shown that medium from irradiated cells can induce bystander effect in non-irradiated cells [8–10]. To clearly identify the potential contribution of medium alone and of medium plus cell irradiation to the bystander effect, the double-mylar method was utilized in this study.

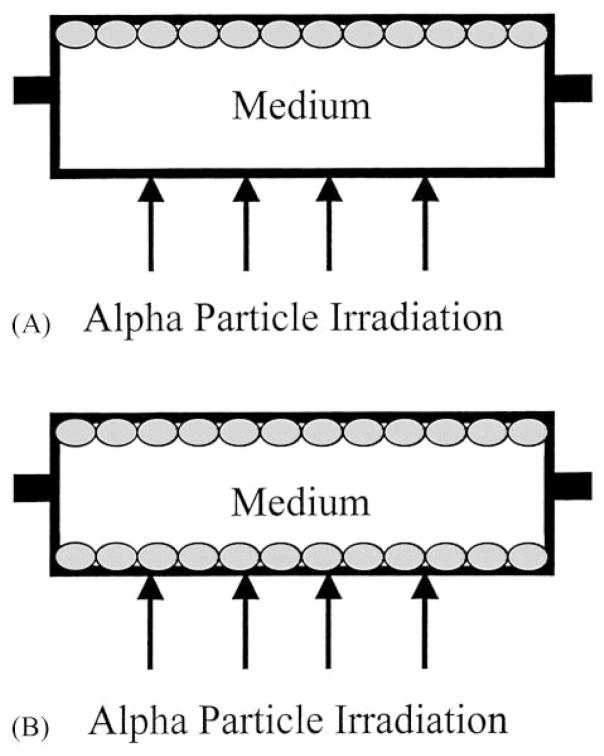

The double-mylar technique is useful for evaluating the roles of medium in bystander effects since cells can be plated on either one or both sides of the dishes (Fig. 1), the distance between the mylar surfaces in the double-mylar dishes is 9.5 mm. Since, low energy α-particles can only traverse a very limited distance, typically less than 50 μm, when one side (with or without cells) is irradiated with α-particles, cells on the other sides will not receive any hits. Because there is no cell–cell contact between cells on the two sides and the only communication available is through the medium, this is a novel approach to investigate the roles of medium in mediating the bystander effect.

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of a representative 35 mm i.d. double-mylar cell culture dish where only the upper layer contains a monolayer of attached cells (A). When α-particles traverse the bottom mylar layer, no cells are hit. In contrast, when a monolayer of cells are plated on both mylar layers which are separated by 9.5 mm (B), α-particles would traverse the bottom but not the top layer of cells. A hole on each side of the ring serves as a filling port for medium.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cell culture

The human–hamster hybrid (AL) cells that contain a standard set of Chinese hamster ovary-K1 chromosomes and a single copy of human chromosome 11 were used in this study. Chromosome 11 encodes cell surface markers that render AL cells sensitive to killing by a specific monoclonal antibody in the presence of complement. Rabbit serum complement was from HPR (Denver, PA). Antibody specific to the CD59 antigen was produced from hybridoma culture as described [11,12]. Cells were maintained in Ham’s F-12 medium supplemented with 8% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 25 μg/ml gentamycin and 2 × 10−4 M glycine at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator and passaged as described [13–15].

2.2. Irradiation procedure

Exponentially growing AL cells were plated on one side or both sides of the double-mylar dishes several days before irradiation, depending on the cell density requirement of experiments. Mylar (6 μm in thickness) is epoxied to both sides of 35 mm i.d. stainless steel rings (42 mm o.d.). The stainless steel rings have access ports with plugs on opposite sides (Fig. 1) with the two mylar cell growth surfaces being 9.5 mm apart. Briefly, 1 × 105 exponentially growing AL cells were plated on one side of double-mylar dishes. Two days later, the medium was aspirated, the double-mylar dishes were turned over and 2 × 105 cells were plated on the other side. After cells attached on the bottom (at that time, the cells on the upper layer remained hydrated), the dish was filled up with 7–8 ml completed medium and kept in an incubator for another 2 days before irradiation. One side of dishes with or without attached cells (bottom layer) were irradiated by the 90 keV/μm α-particles ranging in doses from 0.1 to 100 Gy using the track segment mode of a 4 MeV Van de Graaff accelerator at the Radiological Research Accelerator Facility of Columbia University. The linear energy transfer of the α-particles is the same as that used in bystander microbeam experiments [5,14,16]. After irradiation, cells were kept in the dishes for either 1 or 48 h, then the non-irradiated cells in the upper layer were collected for the survival and the mutation assay as described before [13–15].

2.3. Cytotoxicity of irradiated medium with or without cells on non-irradiated cells

Upper mylar sheets containing non-irradiated AL cells were collected either at 1 or 48 h after irradiation. Cultures were trypsinized, counted with a Coulter counter and aliquots of the cells were re-plated into 100 mm diameter petri-dishes for colony formation, the others were further incubated for mutation assay. Cultures for clonogenic survival assay were incubated for 7–8 days, at which time they were fixed with formaldehyde and stained with Giemsa. The number of colonies was counted to determine the surviving fraction as described [13–15].

2.4. Quantification of mutations at the CD59 locus

To determine the mutant fraction, after a 7-day expression period, 5 × 104 cells per dish were plated into six 60 mm dishes in a total of 2 ml of growth medium, the cultures were incubated for 2 h to allow for cell attachment, after which 0.3% CD59 antiserum and 1.5% (v/v) freshly thawed complement were added to each dish as described [17]. The cultures were further incubated for 7–8 days. At this time, the cells were fixed and stained and the number of CD59− mutant colonies was scored. Controls included identical sets of dishes containing antiserum alone, complement alone or neither agent. The cultures derived from each treatment dose were tested for mutant yield for two consecutive weeks to ensure full expression of the mutations. The mutant fraction at each dose was calculated as the number of surviving colonies divided by the total number of cells plated after correction for any non-specific killing due to complement alone.

2.5. Statistical analysis

All numerical data were calculated as mean and S.D., comparisons of survival fraction (SF) and mutation fraction between treatment groups and controls were made by Student’s t-test. A P-value of 0.05 or less between groups was considered to be significance of the differences.

3. Results

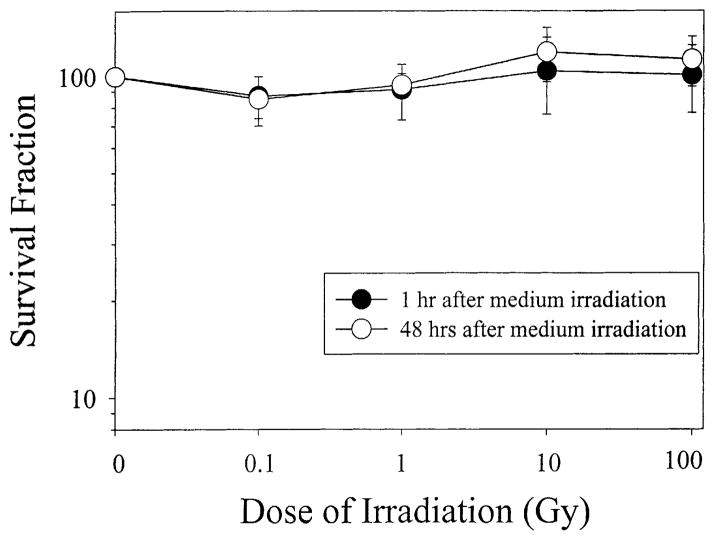

3.1. Effect of irradiated medium alone on the survival of non-irradiated bystander cells

After α-particles were targeted at the empty, bottom mylar layer without attached cells (Fig. 1A), the SFs of non-irradiated AL cells grown on the upper layer were determined. The normal plating efficiency (PE) of AL cell population used in these experiments averaged 0.75 ± 0.06, a number similar to the PE of non-irradiated AL cells cultured in the double-mylar rings. After both 1 and 48 h co-culture, non-irradiated cells in the 0.1 Gy irradiation group showed a slight decrease in SF (SF ~ 0.85, Fig. 2). As the doses increased, the SF of unirradiated cells did not show any further decrease, but a gradual increase instead. However, in no instance was there a significant difference in survival between or among these groups (Fig. 2). As shown in Fig. 2, after 10 or 100 Gy irradiation, the SFs of the non-irradiated cells in the 48 h co-culture group were 1.19 ± 0.23 and 1.13 ± 0.20, respectively, <20% higher than control levels, though the difference was not significant.

Fig. 2.

SF of non-irradiated cells in double-mylar dishes where medium only was irradiated by α-particles ranging in doses from 0.1 to 100 Gy. Data were pooled from three independent experiments. Bar represents ±S.D.

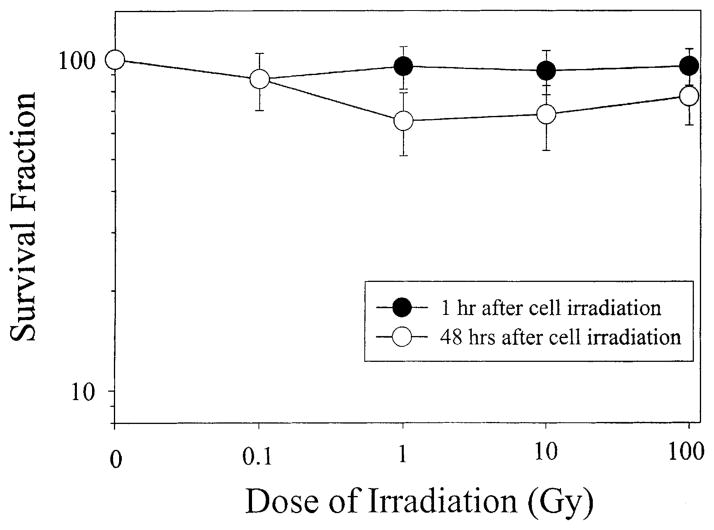

3.2. Effect of α-particle-irradiated medium with cells on the survival of non-irradiated cells

One hour after the bottom layer with AL cells were irradiated by α-particles ranging in doses from 0.1 to 100 Gy, there were no significant differences in survival between the upper non-irradiated layer of cells and control, where no α-particles were delivered (Fig. 3). However, if the cells were continuously co-cultured for a period of 48 h, the SF of the non-irradiated, upper layer of cells decreased significantly at doses between 1 and 100 Gy (P < 0.05), but there was no clear response as dose increased. It should be noted that if these values are contrasted against the values of medium alone irradiation rather than no irradiation, these significant differences are further enhanced. These data suggest that irradiated cells released certain cytotoxic factor(s) into the culture medium that were toxic to the non-irradiated cells.

Fig. 3.

SF of non-irradiated cells in double-mylar dishes where the bottom layer of cells were irradiated with graded doses of α-particles from 0.1 to 100 Gy. Data were pooled from three independent experiments. Bar represents ±S.D.

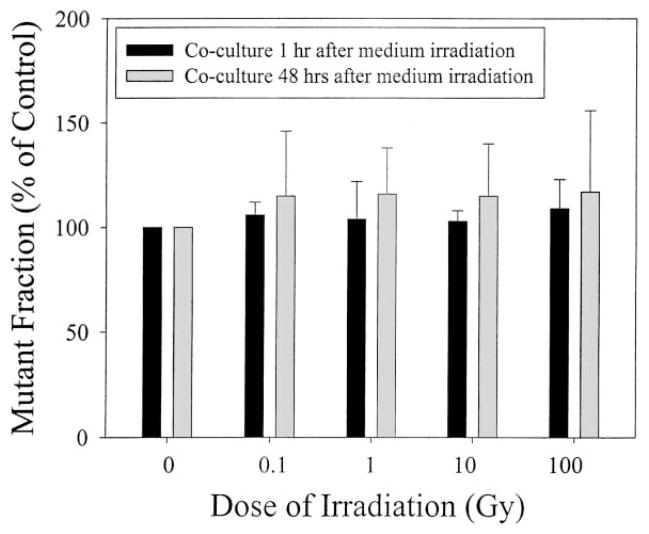

3.3. Effects of irradiated medium with or without cells on induction of bystander mutagenesis

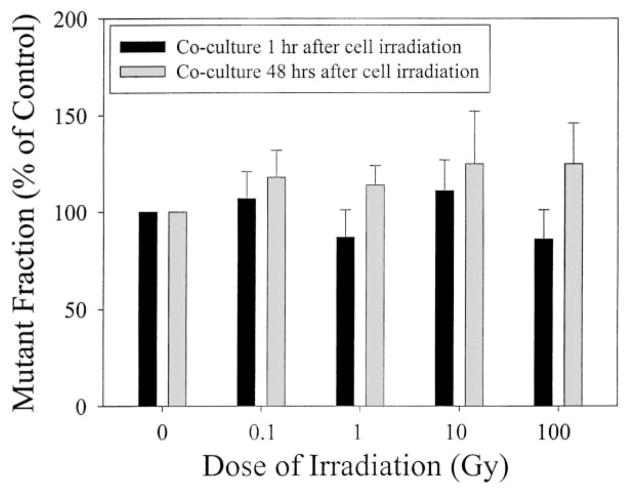

Figs. 4 and 5 show the CD59 mutant yield of the upper non-irradiated layer of AL cells induced by graded doses of the α-particles delivered at the bottom layer of mylar without and with an attached mono-layer of cells, respectively. The spontaneous mutant fraction of AL cells used in this study was 52 ± 10 per 105 survivors. Compared to non-irradiated controls, irradiated medium without cells, when co-cultured with an upper layer of non-hit cells for either 1 or 48 h, had no significant effect on the spontaneous CD59 mutation incidence of the latter over a range of α-particle doses from 0.1 to 100 Gy (Fig. 4). Similarly, when a monolayer of cells attached to the bottom layer of the mylar were irradiated and co-cultured for either 1 or 48 h with the upper layer of non-irradiated cells, the mutant fractions of the latter were not significantly different from the controls (Fig. 5). It should be noted that mutation levels for cells assayed after 48 h exposure were consistently greater than those found after 1 h exposure, though the differences were not statistically significant. A persistent, non-dose dependent increase in mutant fraction of 20–25% above the background level was seen in the bystander cells following exposure to irradiated medium for 48 h. However, this induction level was not significantly different from the background level. These results suggested that the cytotoxic factor(s) that was released from irradiated cells into the culture medium had little effect on the mutagenic response of the non-irradiated cells exposed to the same culture medium.

Fig. 4.

Mutation fraction of the upper, non-irradiated layer of AL cells in double-mylar dishes where only media were irradiated by α-particles ranging in doses from 0.1 to 100 Gy. Data were pooled from three independent experiments. Bar represents ±S.D.

Fig. 5.

Mutation fraction of the upper, non-irradiated layer of AL cells in double-mylar dishes where the bottom layer of cells were irradiated with graded doses of α-particles from 0.1 to 100 Gy. Data were pooled from three independent experiments. Bar represents ± S.D.

4. Discussion

It has long been accepted that the important genetic effects of radiation in mammalian cells, such as mutation and carcinogenesis are attributable mainly to the direct result of DNA damage. However, recent investigations have indicated that α-particles can cause DNA alterations by a mechanism(s) that is independent of nuclear or even whole-cell traversals [1–10]. Such a phenomenon has been observed with both high and low LET irradiations. For example, very low doses of α-particles can induce sister chromatid exchanges in both Chinese hamster ovary and human fibroblast cultures at levels significantly higher than expected based on microdosimetric calculation of the number of cells estimated to have been traversed by a particle [1,2]. These studies suggest that bystander effects might be induced by damage signals transmitted from irradiated to neighboring non-irradiated cells [5,7] or be mediated by soluble extracellular factors [8,18,19]. However, the mechanism(s) of the bystander effects is unclear. It was found, for example, that conditioned medium from γ-irradiated epithelial cells reduced the PE and increased the incidence of apoptosis of unirradiated epithelial cells, but that this effect was not observed in similarly treated fibroblasts. This effect was found to be dependent on cell number present at the time of irradiation, suggesting the production of soluble factor(s) by the irradiated cells [8].

Using the microbeam facility at Columbia University, our laboratory reported that cytoplasmic traversal by α-particles resulted in a mutagenic response in the nucleus of the target cells at a frequency that was three times higher than background, while inflicting minimal toxicity and that free radicals mediated the mutagenic process [16]. Furthermore, we found that cells lethally irradiated with α-particles induced a bystander mutagenic response in neighboring non-irradiated cells at a level that was two–three-fold higher than expected in the absence of bystander modulation and that cell–cell communication process played a critical role in mediating the process [5]. Herein, using double-mylar technique, we found that when the lower layer of attached cells were irradiated with α-particles, the SF among the non-irradiated upper layer of cells was significantly lower than that of control after 48 h of co-culture and that no dose–response relationship was observed. However, no change in survival was detected in the 1 h co-culture group or in groups where only medium was irradiated. These survival data suggested that irradiated cells released certain cytotoxic factor(s) into the culture medium that were toxic to the non-irradiated cells. Recently, using normal human fibroblasts, Lehnert and co-workers reported [9,10] that an increase in cell growth induced by very low doses (<0.2 Gy) of α-particles correlated with intracellular increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS) along with a decreased in TP53 and CDKN1A and that these cellular responses were mechanistically coupled. In these processes, it seemed that ROS caused a prompt increase in the availability of extracellular TGF-β that might additionally activate cell surface membrane-associated NADH oxidase and a release of H2O2 as a subsequent and perhaps sustaining event. In the present studies, irradiating medium alone at doses of 10 or 100 Gy, the surviving fraction of non-irradiated upper layer bystander cells increased, although the difference is not significant. It is then possible that irradiating complete medium may produce changes that can stimulate cell growth. However, this effect (if active) is counter-acted when cells are present, since doses from 1 to 100 Gy initiate production of factors in hit cells which are toxic to non-hit cells.

Co-cultivation with irradiated cells had little effect on the mutagenic yield of cells on the non-irradiated half of the double-mylar dishes. These results suggested that the cytotoxic factor(s) that was released from irradiated cells into the culture medium had little effect on the mutagenic response of the non-irradiated cells exposed to the same culture medium. These data are in contrast with our microbeam-based bystander studies. In non-hit bystander cells, mutant fractions were elevated (~three-fold greater than expectation). In the presence of the gap junction inhibitor (lindane), the mutation levels were significantly reduced. Hence, intercellular communication plays a highly significant role in mediating the bystander mutagenic effect [5]. However, these results are also consistent with those reported here in that a small (~1.2-fold) non-significant increase in mutant fraction was recorded from cells exposed to irradiated medium both with and without cells. That is, it appears that cell communication plays a much more dramatic role than cellular release of medium soluble factors in initiating the mutagenic bystander response. Clearly then, multiple mechanisms are involved in mediating bystander responsiveness. These results are also consistent with data obtained in dilution experiments in which cells irradiated with α-particles are mixed with a fixed proportion of control cultures to achieve 20% irradiated population. No significant enhancement in bystander mutagenic effect was detected in these mixing studies [20], again suggesting that cell–cell contact was a principal requirement and that labile mediator(s) was much less likely to be involved in the bystander mutagenesis, at least in the cell line used in this study. In contrast, there is recent evidence that irradiated cells produce an apoptosis inducing molecular(s) into the culture medium and initiate apoptosis in the non-irradiated, bystander cells [19]. More recently, Mothersill et al. founded that medium from irradiated E89 cells (glucose-6-phosphate de-hydrogenase (G6PD) null CHO-K1 cell line) and E89t cells (null CHO-K1 cell line with the G6PD gene transfected back in) both produced a bystander survival effect when irradiated conditioned-medium was transferred to unirradiated HPV 16-immortalized human keratinocytes. However, such an effect was not found when the non-irradiated E89 cells received medium from irradiated E89 cells, which clearly indicated that the response of E89 cells to the signal was compromised by the lack of G6PD although the signal production was present. These data suggested that generation of ATP or reduced NAD/NADP may be critical to the production of a bystander effect, further implicating that signal production and cellular response involves different mechanisms [18]. Combining our recent findings that cell–cell communication process played a crucial role in mediating bystander mutagenesis [5], the present studies provide clear evidence that different bystander end points may involve different mechanisms with different cell types.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr. Stephen Marino of the Radiological Research Accelerator Facility of Columbia University for his help in performing the dosimetry and irradiation. This work was supported in part by NIH Grants CA49062, CA75384, CA75061, DOE 98ER62687 and NIH Resource Center Grant RR 11623.

Footnotes

Presented at Bystander Effects Workshop, Dublin, Ireland, December 2000.

References

- 1.Nagasawa H, Little J. Induction of sister chromatid exchanges by extremely low doses of α-particles. Cancer Res. 1992;52:6394–6396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deshpande A, Goodwin EH, Bailey SM, Marrone BL, Lehnert BE. α-Particle-induced sister chromatid exchange in normal human lung fibroblasts: evidence for an extranuclear target. Radiat Res. 1996;145:260–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prise KM, Belyakov OV, Folkard M, Michael BD. Studies of bystander effects in human fibroblasts using a charged particle microbeam. Int J Radiat Biol. 1998;74:793–798. doi: 10.1080/095530098141087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nagasawa H, Little J. Unexpected sensitivity to the induction of mutations by very low doses of α-particle radiation: evidence for a bystander effect. Radiat Res. 1999;152:552–557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou H, Randers-Pehrson G, Waldren CA, Vannais D, Hall EJ, Hei TK. Induction of a bystander mutagenic effect of α-particles in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:2099–2104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.030420797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hickman AW, Jaramillo RJ, Lechner JF, Johnson NF. α-Particle-induced p53 protein expression in a rat lung epithelial cell strain. Cancer Res. 1994;54:5797–5800. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Azzam EI, de Toledo SM, Gooding T, Little JB. Intercellular communication is involved in the bystander regulation of gene expression in human cells exposed to very low fluencies of α-particles. Radiat Res. 1998;150:497–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mothersill C, Seymour CB. Cell–cell contact during gamma irradiation is not required to induce a bystander effect in normal human karatinocytes: evidence for release during irradiation of a signal controlling survival into the medium. Radiat Res. 1998;149:256–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iyer R, Lehnert BE. Factors underlying the cell growth-related bystander responses to α-particles. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1290–1298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Narayanan PK, Goodwin EH, Lehnert BE. α-Particles initiate biological production of superoxide anions and hydrogen peroxide in human cells. Cancer Res. 1997;57:3963–3971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Waldren CA, Jones C, Puck TT. Measurement of mutagenesis in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:1358–1362. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.3.1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Waldren CA, Correll L, Sognier MA, Puck TT. Measurement of low levels of X-ray mutagenesis in relation to human disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:4839–4843. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.13.4839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hei TK, Waldren CA, Hall EJ. Mutation induction and relative biological effectiveness of neutrons in mammalian cells. Radiat Res. 1988;115:281–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hei TK, Wu LJ, Liu SX, Vannais D, Waldren CA. Mutagenic effects of a single and an exact number of α-particles in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3765–3770. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hei TK, Piao CQ, He ZY, Vannais D, Waldren CA. Chrysotile fiber is a strong mutagen in mammalian cells. Cancer Res. 1992;52:6305–6309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu L, Randers-Pehrson G, Xu A, Waldren CA, Geard CR, Yu Z, Hei TK. Targeted cytoplasmic irradiation with α-particles induced mutations in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:4959–4964. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.4959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu LX, Waldren CA, Vannais D, Hei TK. Cellular and molecular analysis of mutagenesis induced by charged particles of defined linear energy transfer. Radiat Res. 1996;145:251–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mothersill C, Stamato TD, Perez ML, Cummins R, Mooney R, Seymour CB. Involvement of energy metabolism in the production of ‘bystander effects’ by radiation. Br J Cancer. 2000;82:1740–1746. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lyng FM, Seymour CB, Mothersill C. Production of signal by irradiated cells which leads to a response in unirradiated cells characteristic of initiation of apoptosis. Br J Cancer. 2000;83:1223–1230. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou H, Randers-Pehrson G, Suzuki M, Waldren CA, Hei TK. Genotoxic damage in non-irradiated cells: contribution from bystander effect. Radiat Prot Dosim. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.rpd.a006769. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]