Abstract

Objective

To test, using a randomized controlled trial design, the impact of an educational intervention delivered by specially trained community health workers among Chinese, Korean and Vietnamese participants aged 50–75 on knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and intention regarding colorectal cancer screening.

Methods

We collected baseline data on participants’ baseline demographic characteristics, knowledge, attitudes, beliefs about cancer, its risk factors and intention to keep up-to-date on cancer screening in the future. Fifteen intervention sessions were held between April and June of 2011. Follow-up surveys were administered in the post-test period to both intervention and control participants. Those randomized to the control group received educational pamphlets in their native language.

Results

The intervention had the greatest influence on the Chinese subgroup, which had improved scores relative to the control group for Perceived Behavior Control and Intentions (pre- vs. post- change in control group −0.16; change in intervention group 0.11, p=0.004), Behavioral Beliefs on Cancer Screening (pre- vs. post- change in control group −0.06; change in intervention group 0.24, p=0.0001), and for Attitudes Toward Behavior (pre- vs. post- change in control group −0.24; change in intervention group 0.35, p=<0.0001). The intervention had no effect on Behavioral Beliefs on Cancer, Control Beliefs, and Perceived Behavioral Control (Reliance on Family). Though intention to stay up-to-date for cancer screening increased in two study groups (Chinese and Vietnamese), these were not significant.

Conclusions

An educational program delivered by culturally specific community health educators using culturally appropriate language influences some knowledge, attitude and behavioral beliefs but not others.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer screening

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third leading cause of cancer death in the United States (1). Screening in average-risk asymptomatic populations has been shown to reduce both incidence and mortality of this disease (2–5). Thus, the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), the American Cancer Society, and other professional organizations recommend routine screening of average-risk individuals using a variety of screening tools, including fecal occult blood testing, flexible sigmoidoscopy, and colonoscopy. Despite these recommendations, screening rates are low with only about 30–60% of individuals over age 50 having had any form of recommended screening (6, 7).

While colorectal cancer incidence is similar in Asian Americans and non-Hispanic whites (8), research has shown that rates of both colorectal cancer screening and survival are especially low in many Asian subpopulations (9, 10). Asian Americans represent a growing, multi-cultural racial minority in the United States. In 1990, there were 6.9 million Asians in the United States representing 3% of the population. The Census Bureau estimates this population will represent 9% of Americans by 2050 (11).

Studies on factors that influence rates of screening in Asian Americans include English language proficiency, where English speakers have higher rates of screening (12) as well as cultural beliefs (13). These beliefs include that cancer cannot be cured, even if it is found early and that it is contagious (14). Several studies have shown that in Asian populations, greater knowledge about prevention is associated with employment outside the home, higher education, and younger age, but not length of stay in the United States (15, 16). Very little is known about CRC screening practices among the various Asian subgroups. In one study of Filipino and Korean women, only 25% and 38% respectively reported any colon screening, despite higher rates of screening for cervical and breast cancer in the same subjects (17). Another study of Korean Americans over age 60 (18) found 18% had ever had FOBT and 11% had ever had sigmoidoscopy.

Intervention research on cancer screening in this population is limited, especially as it relates to colorectal cancer screening. Studies that involve providing health information on breast and cervical cancer screening have shown improved screening if they use culturally and linguistically appropriate materials (19, 20). Direct contact by outreach workers, compared to direct mail and a control group, has been shown to be especially effective (21), though results vary according to Asian subgroup (20, 21). These studies demonstrate that community health workers can improve screening rates and that interventions targeting Asian subgroups may not be effective unless they are language and culturally specific.

In this pilot study on feasibility and possible effects, we used a randomized controlled trial design to test the impact of an educational intervention, designed using a needs assessment of Asian sub-populations. We specifically evaluated the impact of the intervention on knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, perceptions of cancer risk and intention to keep up-to-date on cancer screening in the future among three Asian subgroups (Chinese, Korean, and Vietnamese).

Methods

Investigators at OHSU partnered with a community-based organization, the Asian Health and Service Center (AHSC) to conduct this study. The AHSC is a nonprofit organization that provides services and/or information to more than 13,000 Asian clients each year in the Portland (Oregon) metropolitan area. AHSC’s mission is to bridge the gap between Asian and American cultures in an effort to build a healthier community. Achieving this mission is accomplished by reducing health disparities and increasing access to high-quality health care for all Asians.

Study Population, Eligibility Criteria & Enrollment

Eligible subjects were men and women of Chinese, Vietnamese or Korean heritage aged 50–75 years, with no prior history of receiving CRC screening within the past 5 years, no prior personal or family history of colon cancer, no major medical illnesses that would preclude them from receiving colorectal cancer screening, the ability to sign informed consent, and willingness to be randomly assigned to one two groups and participate in educational intervention. We excluded those with a first-degree relative with colon cancer and counseled these individuals to speak with their health care provider about appropriate screening. We also excluded other household members of an enrolled participant as the enrolled household members could influence a family member not enrolled in the same group, and assignment of household members into the same group could produce correlated data, which cannot be treated as an independent observation. When a family was approached, they decided which member would take part in the study. Lastly, we excluded those with significant medical problems, which would preclude benefit of colon screening. Staff at AHSC identified eligible participants and enrolled them into the study.

Measurement Instrument Design, Development and Pilot Testing

We developed survey instruments designed to assess: 1) the demographic characteristics of participants; 2) knowledge, attitudes and beliefs (KAB) about colorectal cancer, risk factors and colorectal cancer screening; and 3) intention to be up-to-date on cancer screening in the future. Intention was our primary outcome variable due to the low likelihood of health insurance coverage in this population (~30%). The Theory of Planned Behavior Change (22–25) guided the development of our 25-item KAB and intention to be screened questions that addressed Behavioral Beliefs (individual’s belief about consequences of particular behavior), Attitudes Toward a Behavior (individual’s positive or negative evaluation of self-performance of the particular behavior), and Control Beliefs (individual’s beliefs about the presence of factors that may facilitate or impede performance of the behavior). Briefly, the Theory of Planned Behavior describes the link between beliefs and behavior and is one of the most predictive persuasion theories (22). It has been applied to studies of the relationships among beliefs, attitudes, behavioral intentions and behaviors in many fields including healthcare and patient self care (23–25). We conducted an exploratory factor analysis using the baseline survey responses and further revised domains, the results of which are reported elsewhere (26). The demographic questions were administered once at baseline to all study participants. The KAB questions were administered to both study groups before and after the intervention period was concluded.

Intervention Design, Development and Implementation

Enrolled participants were randomized to either a control or intervention group in 1:1 ratio according to a subgroup-specific randomization list, which was generated prior to the study by a project statistician using a permuted block randomization method. All participants received American Cancer Society educational brochures about colorectal cancer screening in English and in their primary language. The intervention group additionally received a live instructor-led (by a specially trained health educator in their own culture from AHSC) intervention that was culturally and linguistically tailored to each Asian subgroup.

The intervention had two components. In the first, a community health worker provided background information, which was collaboratively designed by the community and the research team, on the importance of colorectal cancer screening, what tests are available for this, where to go to obtain the tests and where to go to get the tests for free or at a reduced cost. In addition, if patients identified themselves as being in need of a primary care provider, they were assisted in finding one by staff in the Asian Health and Service Center. In the second component, health messages that help overcome barriers people experience when thinking about getting colorectal cancer screening was provided to the participants in a way that allowed them to be active learners. Component two of the intervention was informed by responses of the first 184 enrollees of the study, which were processed and summarized according to participant gender and Asian Subgroup (Chinese, Korean, and Vietnamese). These data were shared with key informants from the study population sub groups (Chinese and Korean on Sept 22nd, 2009 and on May 7th, 2010 with Vietnamese; total cultural informants = 2 males and 4 females) and relevant health messages were developed for incorporation into the intervention using popular education techniques (27). The session was delivered using a PowerPoint presentation by health educators who were culturally and linguistically from the Asian subgroup attending that session. A member of the study team (authors PAC, FLL, or DAL) attended all sessions to respond to questions from participants, which were translated into the participant language. Fifteen identical education sessions, five for each of the three Asian subgroups, were delivered to enrolled participants between April and June of 2011.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the demographic characteristics according to Asian subgroup and study group assignment, and were compared using chi-square tests for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables. Mixed effects models were used to compare pre- vs. post-intervention changes between two study groups. The analyses were conducted separately for each Asian subgroup. The following six domain scores were used as our primary outcomes: 1) Perceived Behavioral Control (doctors) and Behavioral Intentions (participants); 2) Behavioral Beliefs (cancer screening); 3) Attitudes Toward Behavior (cancer screening); 4) Behavioral Beliefs (cancer); 5) Control Beliefs (Eastern/Asian medicine); and 6) Perceived Behavioral Control (reliance on family). A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Analysis System 9.3 (SAS). To ensure no bias due to dropouts, we performed the statistical analyses using both the intent-to-treat (ITT) analysis set (all randomized subjects) as well as the efficacy analysis set (subjects with pre- and post-intervention measures). We found that our results were consistent in both analyses and present the results using the ITT analysis set.

Results

Of 900 participants who were approached to take part in the study (243 Korean, 338 Vietnamese, and 319 Chinese), 654 (72.7%) actually enrolled, and all of these participants provided baseline data. Three hundred and twenty-nine were randomized to receive the intervention and 325 were randomized into the comparison group. Of those randomized to the intervention, 269 (82.8%) signed up to take part in it and 225 (69.2%) actually attended one of the educational sessions. Randomization of enrolled participants produced groups that were similar regarding their demographic characteristics (Table 1). The average age of participants was just over 63 years. The majority of participants was female, and had a high school education; few had undertaken college or technical school courses. Most participants were unemployed, had health insurance, typically Medicare/Medicaid, and spoke their native language at home, though many had some English language proficiency.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Study Participants According to Study Group Assignment (n=654)

| Characteristics | Instructor-led Educational Intervention (n=329) | Comparison Group (Brochures Only) (n=325) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Race | 0.99a | ||

| Chinese | 120 (36.5%) | 118 (36.3%) | |

| Korean | 109 (33.1%) | 108 (33.2%) | |

| Vietnamese | 100 (30.4%) | 99 (30.5%) | |

|

| |||

| Mean Age (SD) | 63.1 (7.8) | 63.5 (7.9) | 0.52b |

| Range | 46–91 | 49–86 | |

|

| |||

| % Male | 106 (32.2%) | 118 (36.4%) | 0.26a |

|

| |||

| Mean Years in U.S. (SD) | 19.39 (11.5%) | 19.18 (11.6%) | 0.82b |

|

| |||

| Marital Status | Missing 1 | 0.54a | |

| Currently married (%) | 223 (68.0%) | 233 (71.7%) | |

| Not married, living with partner (%) | 3 (0.9%) | 3 (0.9%) | |

| Single, never married (%) | 16 (4.9%) | 15 (4.6%) | |

| Separated (%) | 11 (3.4%) | 8 (2.5%) | |

| Divorced (%) | 33 (10.1%) | 20 (6.2%) | |

| Widowed (%) | 42 (12.8%) | 46 (14.2%) | |

|

| |||

| Highest educational level | Missing 2 | Missing 2 | 0.30a |

| Did not undertake any formal schooling (%) | 16 (4.9%) | 12 (3.7%) | |

| Some elementary school (%) | 76 (23.2%) | 80 (24.8%) | |

| Completed elementary school (%) | 126 (38.5%) | 112 (34.7%) | |

| Some high school (%) | 41 (12.5%) | 38 (11.8%) | |

| Completed high school (%) | 58 (17.7%) | 59 (18.3%) | |

| Some college or technical school (%) | 10 (3.1%) | 22 (6.8%) | |

|

| |||

| Employment | Missing 7 | Missing 12 | 0.74a |

| Employed full time (%) | 89 (27.6%) | 89 (28.4%) | |

| Employed part time (%) | 34 (10.6%) | 38 (12.1%) | |

| Not currently employed (%) | 166 (51.6%) | 161 (51.4%) | |

| Retired (%) | 33 (10.3%) | 25 (8.0%) | |

|

| |||

| Insurance Status | Missing 41 | Missing 27 | |

| Insured (%) | 113 (63.8%) | 117 (66.9%) | 0.55a |

| Uninsured (%) | 64 (36.2%) | 58 (33.1%) | |

| If Insured, Insurance type: | |||

| Private (%) | 46 (40.7%) | 41 (35.0%) | 0.04 |

| Medicare/Medicaid (%) | 51 (45.5%) | 65 (55.6%) | |

| Other (%) | 9 (8.0% | 2 (1.7%) | |

|

| |||

| Language spoken at home | 0.90b | ||

| Chinese | 100 (30.4%) | 93 (28.6%) | |

| Mandarin | 57 (17.3%) | 49 (15.1%) | |

| Cantonese | 85 (25.8%) | 88 (27.1%) | |

| Mandarin & Cantonese | 22 (6.7%) | 20 (6.2%) | |

| Korean (%) | 107 (32.5%) | 106 (32.6%) | |

| Vietnamese (%) | 90 (27.4%) | 89 (27.4%) | |

|

| |||

| English (%) | 32 (9.7%) | 37 (11.4%) | |

| English language proficiency | Missing 4 | Missing 3 | 0.50a |

| Fluent (%) | 7 (2.2%) | 10 (3.1%) | |

| Well (%) | 12 (3.7%) | 17 (5.3%) | |

| Average (%) | 88 (27.0%) | 82 (25.6%) | |

| Fair (%) | 105 (32.2%) | 95 (29.6%) | |

| Poor (%) | 62 (19.0%) | 52 (16.2%) | |

| Not at all (%) | 52 (16.0%) | 65 (20.3%) | |

Chi-square test

T-test

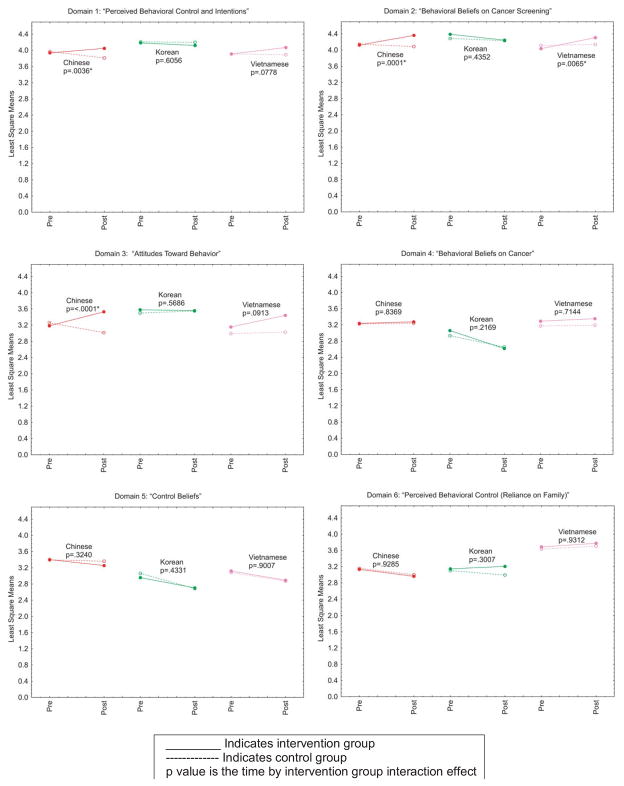

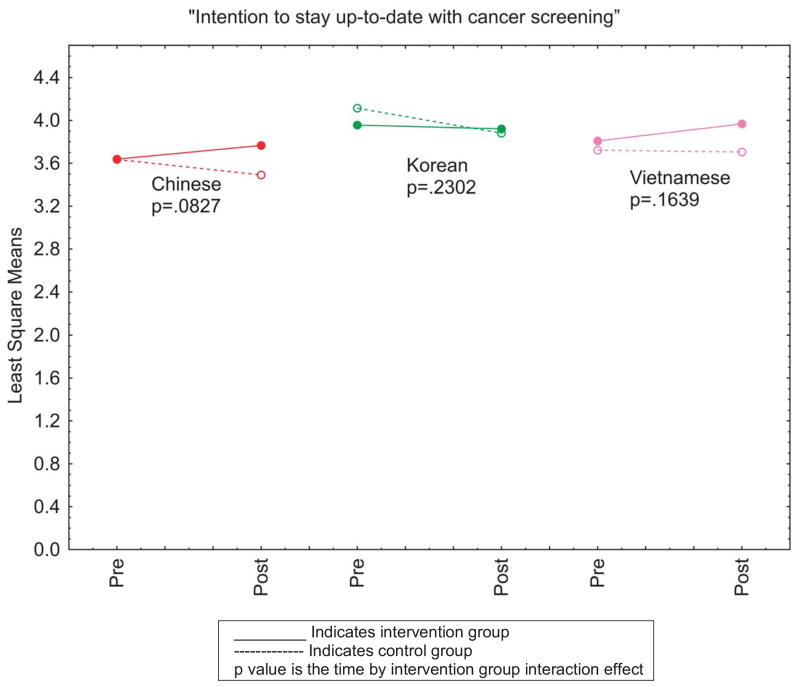

Figure 1 displays least square (LS) means of the domain scores at baseline and post-intervention according to both study group assignment and Asian subgroup. The p values reflect whether pre- vs. post-intervention change was significantly different between two study groups. This illustrates that, for the domain Perceived Behavior Control and Intentions, the impact of the intervention had the greatest effect on the Chinese subgroup. The intervention did not change the variables in this Domain for Koreans or Vietnamese, and in fact, for Koreans the post intervention variables were lower than they had been at baseline. For the Behavioral Beliefs on Cancer Screening Domain, the intervention had effects on the Chinese and Vietnamese subgroups with no statistical differences among Koreans with this group’s post intervention scores falling lower in the post intervention period than they had been at baseline. The Attitudes Toward Behavior Domain also show the intervention had the greatest impact on Chinese participants and the least impact on Korean participants. The other graphs in Figure 1 show variables in the Behavioral Beliefs on Cancer, Control Beliefs, and Perceived Behavioral Control Reliance on Family Domains respectively, none of which showed any effects of the intervention for any Asian subgroup. Figure 2 shows impact the intervention has on intention to stay up to date for cancer screening. Though intention increased in two study groups (Chinese and Vietnamese), these were not significant. In addition, among Koreans, the intervention did not change intention at all.

Figure 1. Differences in Least Square Means of each Domain According to Study Group and Asian Subgroup.

This interaction plot displays the least square means of the domain scores at baseline and post-intervention according to both study group assignment and Asian subgroup. The p values reflect whether pre- vs. post-intervention change was significantly different between two study groups.

––––– Intervention group ------ Control group

Figure 2. Intention to Stay Up to Date for Cancer Screening According to Study Group and Asian Subgroup.

This plot shows the impact the intervention has on intention to stay up to date for cancer screening. The p values reflect whether pre- vs. post-intervention change was significantly different between two study groups.

––––– Intervention group ------ Control group

Tables 2a, 2b and 2c show the LS means, standard error and p values for the pre- vs. post- intervention change for each of the Chinese, Korean, and Vietnamese subgroup, respectively.

Table 2a.

Least Square Means and Standard Error for Chinese Subgroup

| Least Square Mean (Standard Error) | Pre | Post | Change | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | Perceived behavioral control & intentions | Control | 3.97 (0.05) | 3.81 (0.06) | −0.16 | 0.004* |

| Intervention | 3.94 (0.05) | 4.05 (0.06) | 0.11 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Behavioral beliefs on cancer screening | Control | 4.14 (0.04) | 4.09 (0.04) | −0.06 | 0.0001* | |

| Intervention | 4.12 (0.04) | 4.36 (0.05) | 0.24 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Attitudes toward behavior | Control | 3.26 (0.06) | 3.01 (0.07) | −0.24 | <.0001* | |

| Intervention | 3.18 (0.06) | 3.53 (0.08) | 0.35 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Behavioral beliefs on cancer | Control | 3.23 (0.05) | 3.24 (0.05) | 0.02 | 0.837 | |

| Intervention | 3.24 (0.05) | 3.27 (0.06) | 0.04 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Control beliefs | Control | 3.40 (0.06) | 3.36 (0.06) | −0.03 | 0.324 | |

| Intervention | 3.40 (0.06) | 3.25 (0.07) | −0.15 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Perceived behavioral control | Control | 3.16 (0.08) | 3.00 (0.09) | −0.16 | 0.929 | |

| Intervention | 3.13 (0.08) | 2.96 (0.1) | −0.17 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Intention to stay up to date on screening | Control | 3.64 (0.08) | 3.49 (0.09) | −0.15 | 0.083 | |

| Intervention | 3.64 (0.08) | 3.77 (0.1) | 0.13 | |||

Table 2b.

Least Square Means and Standard Error for Korean Subgroup

| Least Square Mean (Standard Error) | Pre | Post | Change | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Korean | Perceived behavioral control & intentions | Control | 4.21 (0.05) | 4.2 (0.06) | −0.01 | 0.606 |

| Intervention | 4.18 (0.05) | 4.12 (0.07) | −0.06 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Behavioral beliefs on cancer screening | Control | 4.29 (0.05) | 4.23 (0.06) | −0.05 | 0.435 | |

| Intervention | 4.39 (0.05) | 4.24 (0.06) | −0.15 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Attitudes toward behavior | Control | 3.5 (0.07) | 3.55 (0.08) | 0.05 | 0.569 | |

| Intervention | 3.58 (0.07) | 3.56 (0.08) | −0.02 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Behavioral beliefs on cancer | Control | 2.93 (0.07) | 2.65 (0.08) | −0.28 | 0.217 | |

| Intervention | 3.06 (0.07) | 2.62 (0.08) | −0.44 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Control beliefs | Control | 3.06 (0.08) | 2.69 (0.1) | −0.38 | 0.433 | |

| Intervention | 2.96 (0.08) | 2.7 (0.1) | −0.25 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Perceived behavioral control | Control | 3.1 (0.08) | 2.99 (0.1) | −0.11 | 0.301 | |

| Intervention | 3.15 (0.08) | 3.21 (0.1) | 0.06 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Intention to stay up to date on screening | Control | 4.11 (0.09) | 3.88 (0.1) | −0.23 | 0.230 | |

| Intervention | 3.96 (0.09) | 3.92 (0.1) | −0.04 | |||

Table 2c.

Least Square Means and Standard Error for Vietnamese Subgroup

| Least Square Mean (Standard Error) | Pre | Post | Change | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vietnamese | Perceived behavioral control & intentions | Control | 3.91 (0.06) | 3.89 (0.06) | −0.02 | 0.078 |

| Intervention | 3.91 (0.06) | 4.07 (0.06) | 0.16 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Behavioral beliefs on cancer screening | Control | 4.11 (0.05) | 4.14 (0.05) | 0.02 | 0.006*

|

|

| Intervention | 4.03 (0.05) | 4.31 (0.05) | 0.27 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Attitudes toward behavior | Control | 2.99 (0.08) | 3.03 (0.08) | 0.04 | 0.091 | |

| Intervention | 3.15 (0.08) | 3.44 (0.08) | 0.29 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Behavioral beliefs on cancer | Control | 3.17 (0.06) | 3.19 (0.07) | 0.02 | 0.714 | |

| Intervention | 3.29 (0.06) | 3.35 (0.07) | 0.06 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Control beliefs | Control | 3.08 (0.07) | 2.87 (0.08) | −0.21 | 0.901 | |

| Intervention | 3.12 (0.07) | 2.89 (0.08) | −0.23 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Perceived behavioral control | Control | 3.63 (0.08) | 3.71 (0.09) | 0.07 | 0.931 | |

| Intervention | 3.69 (0.08) | 3.78 (0.09) | 0.09 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Intention to stay up to date on screening | Control | 3.72 (0.07) | 3.7 (0.08) | −0.02 | 0.164 | |

| Intervention | 3.81 (0.07) | 3.97 (0.08) | 0.16 | |||

Table 3 shows participants’ evaluation of the educational intervention immediately following its completion. The majority of participants believed the intervention helped them understand colorectal cancer, its risk factors and the options regarding screening tests. In addition, most felt the program helped them understand how to talk with their physicians about colorectal cancer screening, what was needed to prepare for the tests, and that worry about cancer should not stop them from getting tested. Lastly, participants were unified in their positive responses regarding the value of having the sessions at the Asian Health Service Center, and taught in their respective native languages.

Table 3.

Responses to Questions Regarding the Educational Intervention According to Asian Subgroup (n=224)

| Educational Intervention Session Questions | Chinese (n=80) | Korean (n=61) | Vietnamese (n=83) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| The session helped me understand colorectal cancer and how it develops. | |||

| Strongly agree/Agree | 97.50 | 98.36 | 98.80 |

| Neutral | 1.25 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Disagree/Strongly disagree | 1.25 | 1.64 | 1.20 |

|

| |||

| The session helped me understand risk factors for colorectal cancer. | |||

| Strongly agree/Agree | 95.00 | 98.36 | 98.80 |

| Neutral | 2.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Disagree/Strongly disagree | 2.50 | 1.64 | 1.20 |

|

| |||

| The session helped me understand what tests can be used to screen for colorectal cancer. | |||

| Strongly agree/Agree | 95.00 | 98.36 | 97.59 |

| Neutral | 2.50 | 0.00 | 1.20 |

| Disagree/Strongly disagree | 2.50 | 1.64 | 1.20 |

|

| |||

| The session helped me understand how to talk to my doctor about colorectal cancer screening. | |||

| Strongly agree/Agree | 95.00 | 98.36 | 98.80 |

| Neutral | 2.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Disagree/Strongly disagree | 2.50 | 1.64 | 1.20 |

|

| |||

| The session helped me understand how to prepare for having the colorectal cancer screening tests. | |||

| Strongly agree/Agree | 96.25 | 98.36 | 97.59 |

| Neutral | 1.25 | 0.00 | 1.20 |

| Disagree/Strongly disagree | 2.50 | 1.64 | 1.20 |

|

| |||

| The session helped me understand how to talk with my family and friends about colorectal cancer screening. | |||

| Strongly agree/Agree | 95.00 | 98.36 | 98.80 |

| Neutral | 2.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Disagree/Strongly disagree | 2.50 | 1.64 | 1.20 |

|

| |||

| The session helped me understand that worry should not stop me from getting screening tests. | |||

| Strongly agree/Agree | 86.25 | 100.00 | 96.39 |

| Neutral | 1.25 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Disagree/Strongly disagree | 12.50 | 0.00 | 3.61 |

|

| |||

| As a result of this session, I feel more ready to get a colorectal cancer screening test. | |||

| Strongly agree/Agree | 96.25 | 98.36 | 96.39 |

| Neutral | 2.50 | 1.64 | 1.20 |

| Disagree/Strongly disagree | 1.25 | 0.00 | 2.41 |

|

| |||

| As a result of this session, I feel better able to tell my family members and friends that they should get screened for colorectal cancer. | |||

| Strongly agree/Agree | 97.50 | 100.00 | 98.80 |

| Neutral | 2.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Disagree/Strongly disagree | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.20 |

|

| |||

| Having the session at Asian Health Service Center, a community group building that I visit, was a good idea | |||

| Strongly agree/Agree | 93.75 | 100.00 | 96.39 |

| Neutral | 5.00 | 0.00 | 2.41 |

| Disagree/Strongly disagree | 1.25 | 0.00 | 1.20 |

|

| |||

| Having the session taught in my native language was helpful | |||

| Strongly agree/Agree | 97.47 | 100.00 | 96.39 |

| Neutral | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.41 |

| Disagree/Strongly disagree | 2.53 | 0.00 | 1.20 |

|

| |||

| I felt very comfortable asking questions about topics I did not understand. | |||

| Strongly agree/Agree | 97.50 | 100.00 | 96.39 |

| Neutral | 1.25 | 0.00 | 2.41 |

| Disagree/Strongly disagree | 1.25 | 0.00 | 1.20 |

|

| |||

| I would agree to be in another study that was done with a community organization that I am familiar with | |||

| Strongly agree/Agree | 88.75 | 100.00 | 96.39 |

| Neutral | 10.00 | 0.00 | 2.41 |

| Disagree/Strongly disagree | 1.25 | 0.00 | 1.20 |

|

| |||

| I think this educational session will be well received by other people of my age and from my country. | |||

| Strongly agree/Agree | 97.50 | 98.36 | 96.39 |

| Neutral | 1.25 | 1.64 | 2.41 |

| Disagree/Strongly disagree | 1.25 | 0.00 | 1.20 |

Discussion

Our study succeeded in creating a successful partnership with a culturally relevant community organization to conduct a randomized educational intervention trial in racial/ethnic minority. We collaborated on enrolling participants, collecting baseline and post intervention data and in designing an intervention we hypothesized would be effective in influencing the intention of Asian Americans in the three subgroups to become and stay up to date for cancer screening. Our high attendance rate clearly illustrates the success of the partnership as we are certain that efforts to contact and enroll participants using study staff at Oregon Health & Science University would not have resulted in similar enrollment or participation. This is similar to findings of at least one other study (21) that showed use of culturally-specific community health educators succeeded in engaging women of those cultures in testing strategies to improve cervical and breast cancer screening.

Our randomization strategy also worked well to produce equivalent groups, and some aspects of the intervention showed effects for three of the six domains measured among the Chinese subgroup, including Perceived Behavior Control and Intentions, Behavioral Beliefs, and Attitudes Toward Behavior. Perceived behavioral controls reflect views individuals have about the impact their clinicians have on healthcare decisions and intention to get tests, in this case CRC screening tests. If participants did not have a physician or lacked access to health care, their responses could have been influenced. Over half of our participants were not employed, and this rate was higher in the Chinese group (63%) than in the Korean group (44%). Behavioral beliefs reflect views related to the relationship between behaviors and healthy living, including that cancer can be cured if it is found early. Attitudes toward a behavior reflects views groups of individuals share, such as norms related to talking with others about getting cancer screening. It may be that Chinese had higher scores in these domains because health is a higher priority among this Asian subgroup than it is among the other subgroups (28).

We found the intervention had an effect among Vietnamese for the Behavioral Beliefs only, and it had no effect among the Korean participants. Interestingly, the intervention resulted in lower scores post intervention compared to baseline for Control Beliefs for all three Asian subgroups. The Control Beliefs Domain reflects views about Eastern/Asian medicine and using this to treat health problems. It appears the intervention resulted in lower scores on views about the use of Eastern medicine for health problems.

Another important finding is that for four of the six domains, post-test scores were lower than at baseline among the Korean participants, it was flat for one domain and increased very slightly for one domain, which was not significant. This suggests that the intervention may have negatively affected knowledge, attitudes and beliefs of this subgroup. Very little research has focused on Korean populations, which has stymied our efforts to scientifically understand how to interpret our findings. We had hoped that receptiveness and satisfaction with the program, as assessed using an evaluation form designed for this purpose, would have provided insights about how our program might have negatively affected knowledge, attitudes and beliefs in the Korean subgroup. However, participants in all three subgroups rated the program very highly. The satisfaction and impact of the program on self-reported understanding of colorectal cancer, its risk factors, and the screening tests available were very similar across the Asian subgroups, so this did not explain this finding. The Korean culture places high value on work (29), and many own their own businesses, such as dry cleaning or restaurants. They place more value on their work than they do their health, which may explain our findings in that their intention to be up-to-date on cancer screening is lower than the other subgroups because they do not see the need to see a physician unless they are sick (29).

Our findings differed from those of other studies that focused on breast and cervical cancer screening (19–21), which showed that community outreach and use of community health care workers using educational strategies improved receipt of breast and cervical cancer screening. One study showed the outreach group had higher uptake of planned screening (72%) compared to mail (59%) and controls (48%) (19). In the Vietnamese community, intervention studies have compared community health care workers with a media-led model. Trained Vietnamese community health workers significantly increased the recognition, receipt and maintenance of breast and cervical cancer screening tests in the targeted community (21). In another separate randomized controlled study on breast cancer screening with Chinese women, significantly more assigned to the intervention (59.2%, 68.7%, and 71.4%) completed a mammogram compared to women in the control group (18.3%, 26.8%, and 42.5%; p<0.0001) at 3-, 6-, and 12-month time points respectively (30). We believe much more research is needed on tailoring interventions to consider participants’ culture with receipt of screening rather than just intention to be screened as the outcome. We also firmly believe that community engagement benefits greatly from the important organizations that exist to serve diverse underserved populations.

Strengths of our study include our ability to successfully enroll participants in three diverse Asian subgroups into an intervention study. Many people of various cultures are uncomfortable with the idea of randomization, so this strength is not inconsequential. Another strength includes our use of an instrument we designed and psychometrically tested (26) indicating the measures were valid. Also, we were able to capture complete data on participants in both study groups and the extent of attendance at the educational intervention. Weakness of our study include that we used intention to receive screening rather than actual receipt of colorectal cancer screening as a study endpoint. It would have strengthened the study if we had measured both, but we were concerned about capturing screening outcomes as so many participants were uninsured, as reported to us by staff at the Asian Health and Service Center indicating only between 30–40% were covered. Many studies have reported that the strongest predictor of behavior changes using the Theory of Planned Behavior Change is intention to undertake a change. For our study, this was intention to obtain cancer screening, which further justifies the use of intention as a meaningful outcome. Other weaknesses in our study include that self-selection bias likely affects our findings and that participants were all residents of the Portland, OR metropolitan area, which affects the generalizability of our findings.

In conclusion, our study found that an educational program delivered by culturally specific community health educators using culturally appropriate language can influence some knowledge, attitude and behavioral beliefs especially for Chinese participants, but may not be as effective with other subgroups. The intervention we tested did not significantly change intention to obtain and stay up-to-date with cancer screening.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute (R21CA120974, Lieberman, PI), Knight Cancer Institute (P30 CA069533C), and the Family Medicine Research Program at Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, OR).

Footnotes

The authors have no financial or other conflicts of interest to declare related to this work.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. [Accessed 4/23/13];Cancer Prevention & Early Detection Facts & Figures. 2013 http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@epidemiologysurveilance/documents/document/acspc-037535.pdf.

- 2.Mandel JS, Bond JH, Church TR, Snover DC, Bradley GM, Schuman LM, et al. Reducing mortality from colorectal cancer by screening for fecal occult blood. New England Journal of Medicine. 1993;328:1365–71. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199305133281901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hardcastle JD, Chamberlain J, Robinson MHE, Moss SM, Amar SS, Balfour TW, James PD, Mangham CM. Randomized, Controlled Trial of Fecal Occult Blood Screening for Colorectal Cancer. The Lancet. 1996;148:1472–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)03386-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kronborg O, Fenger C, Olsen J, Jorgensen OD, Sondergaard O. Randomized study of screening for colorectal cancer with fecal occult blood test. The Lancet. 1996;148:1467–71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)03430-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jorgensen OD, Krtonborg O, Fenger C. A randomised study of screening for colorectal cancer using faecal occult blood testing: results after 13 years and seven biennial screening rounds. Gut. 2002;50:29–32. doi: 10.1136/gut.50.1.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carney PA, O’Malley J, Buckley DI, Mori M, Lieberman DA, Fagnan LJ, Wallace J, Liu B, Morris C. The Influence of Health Insurance Coverage on Breast, Cervical, and Colorectal Cancer Screening in Rural Primary Care Settings. Cancer. 2012;118(24):6217–6225. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shapiro JA, Seeff LC, Thompson TD, Nadel MR, Klabunde CN, Vernon SW. Colorectal Cancer Test Use from the 2005 National Health Interview Survey. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008 Jul;17:1623–1630. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCracken M, Olsen M, Chen MS, Jr, Jemal A, Thun M, Cokkinides V, Deapen D, Ward E. Cancer Incidence, Mortality, and Associated Risk Factors Among Asian Americans of Chinese, Filipino, Vietnamese, Korean, and Japanese Ethnicities CA. A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2007;57(4):190–205. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.57.4.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin SS, Clarke CA, Prehn AW, Glaser SL, West DW, O’Malley CD. Survival differences among Asian subpopulations in the United States after prostate, colorectal, breast and cervical carcinomas. Cancer. 2002;94:1175–1182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bolen J, Rhodes L, Powell-Griner E, Bland S, et al. State-specific prevalence of selected health behaviors, by race and ethnicity- Behavioral risk factor surveillance system, 1997. MMWR. 2000;48 (SS02):1–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Passel J, Cohn D. US Population Projections: 2005–2050. Released: February 11, 2008: http://www.pewhispanic.org/2008/02/11/us-population-projections-2005-2050/

- 12.Babey SH, Ponce NA, Etzioni DA, Spencer BA, Brown ER, Chawla N. Cancer screening in California: Racial and ethnic disparities persist. Los Angeles: UCLA Center for Health Policy Research; Sep, 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wong-Kim E, Sun A, DeMattos MC. Assessing cancer beliefs in a Chinese immigrant community. Cancer Control. 2003;10:22–28. doi: 10.1177/107327480301005s04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu MY, Hong OS, Seetoo AD. Uncovering factors contributing to under-utilization of breast cancer screening by Chinese and Korean women living in the United States. Ethn Dis. 13:213–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jackson JC, Do H, Chitnarong K, Tu S, Marchand A, Hislop G, Taylor V. Development of cervical cancer control interventions for Chinese immigrants. Journal of Immigrant Health. 2002;4:147–157. doi: 10.1023/A:1015650901458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Phipps E, Cohen MH, Sorn R, Braitman LE. A pilot study of cancer knowledge and screening behaviors of Vietnamese and Cambodian women. Health care for Women International. 1999;20:195–207. doi: 10.1080/073993399245881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maxwell AE, Bastani R, Warda US. Demographic predictors of cancer screening among Filipino and Korean immigrants. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18:62–8. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(99)00110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Juon HS, Han W, Shin H, Kim KB, Kim MT. Predictors of older Korean Americans’ participation in colorectal cancer screening. J Cancer Educ. 2003;18:37–42. doi: 10.1207/s15430154jce1801_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sadler GR, Thomas AG, Yen JY, Dhanjal SK, Marie Ko C, Tran CH, Wang K. Breast cancer education program based in Asian grocery stores. Journal of Cancer Education. 2000;15:173–177. doi: 10.1080/08858190009528688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taylor VM, Jackson JC, Tu SP, Yasui Y, Schwartz SM, Kuniyuki A, Acorda E, Lin K, Hislop G. Cervical cancer screening among Chinese Americans. Cancer Detection and Prevention. 2002;26:139–145. doi: 10.1016/s0361-090x(02)00037-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bird JA, McPhee SJ, Ha NT, Le B, Davis T, Jenkins CN. Opening pathways to cancer screening for Vietnamese-American women: lay health workers hold a key. Preventive Medicine. 1998;27:821–829. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1998.0365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 1991;50:179–211. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bowie JV, Curbow B, LaVeist TA, Fitzgerald S, Zabora J. The theory of planed behavior change and intention to repeat mammography among African-American women. J Psychosoc Onc. 2003;21(4):23–42. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blanchard CM, Rhodes RE, Nehl E, Fisher J, Sparling P, Courneya KS. Ethnicity and the theory of planned behavior in the exercise domain. Am J Health Behav. 2003;27(6):579–591. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.27.6.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Godin F, Kok G. The theory of planned behavior: a review of its applications to health-related behaviors. 1996;11(2):87–98. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-11.2.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Le TD, Carney PA, Lee-Lin F, Leung H, Lau C, Mori M, Chen Z, Lieberman DA. Differences in Knowledge, Attitudes, Beliefs, and Perceived Risks Regarding Colorectal Cancer Screening Among Chinese, Korean, and Vietnamese Sub-Groups Journal of Community Health. doi: 10.1007/s10900-013-9776-8. (In Press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Torres CA. Participatory action research and popular education in Latin America. International J of Qual Studies in Education. 1992;5(1):51–62. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shive SE, Ma GX, Tan Y, Toubbeh JI, Parameswaran L, Halowichm J. Asian American Subgroup Differences in Sources of Health Information and Predictors of Screening Behavior Californian Journal of Health Promotion. 2007;5(2):112–127. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kwak S. Nationalism and Productivity: The Myth Behind the Korean Work Ethic. Harvard Asia Pacific Review. http://web.mit.edu/lipoff/www/hapr/spring02_wto/workethic.pdf.

- 30.Lee-Lin F, Nguyen T, Pedhiwala N, Dieckmann N, Menon U. A Breast Health Educational Program for Chinese American Women: Three- to Twelve-Months Post-Intervention Effect. Am J Health Promotion. 2013 doi: 10.4278/ajhp.130228-QUAN-91. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]