Abstract

Targeted nanomedicine holds promise to find clinical use in many medical areas. Endothelial cells that line the luminal surface of blood vessels represent a key target for treatment of inflammation, ischemia, thrombosis, stroke, and other neurological, cardiovascular, pulmonary, and oncological conditions. In other cases, the endothelium is a barrier for tissue penetration or a victim of adverse effects. Several endothelial surface markers including peptidases (e.g., ACE, APP, and APN) and adhesion molecules (e.g., ICAM-1 and PECAM) have been identified as key targets. Binding of nanocarriers to these molecules enables drug targeting and subsequent penetration into or across the endothelium, offering therapeutic effects that are unattainable by their nontargeted counterparts. We analyze diverse aspects of endothelial nanomedicine including (i) circulation and targeting of carriers with diverse geometries, (ii) multivalent interactions of carrier with endothelium, (iii) anchoring to multiple determinants, (iv) accessibility of binding sites and cellular response to their engagement, (v) role of cell phenotype and microenvironment in targeting, (vi) optimization of targeting by lowering carrier avidity, (vii) endocytosis of multivalent carriers via molecules not implicated in internalization of their ligands, and (viii) modulation of cellular uptake and trafficking by selection of specific epitopes on the target determinant, carrier geometry, and hydrodynamic factors. Refinement of these aspects and improving our understanding of vascular biology and pathology is likely to enable the clinical translation of vascular endothelial targeting of nanocarriers.

Keywords: drug targeting, intracellular delivery, nanoparticles, nanomedicine, nanocarriers, endothelium, cell adhesion molecules, ICAM-1, ACE, PECAM

Objectives and Challenges of Vascular Targeting of Nanocarriers

Drug Delivery Systems (DDS)

DDS promise to improve pharmacotherapy by optimizing: (i) drug solubility, (ii) its isolation from the body en route to the target site, (iii) its pharmacokinetics (PK) and biodistribution (BD), (iv) control of activity, (v) permeation through biological barriers, and (vi) targeting (Figure 1).1−5 Nanocarriers for drug delivery have diverse chemical contents,6−10 morphologies, surface features, geometries, and physical properties.1,11−20 Intricacies of their design have been reviewed elsewhere;21−24 this article instead focuses on the biological aspects of carrier interactions with target cells.

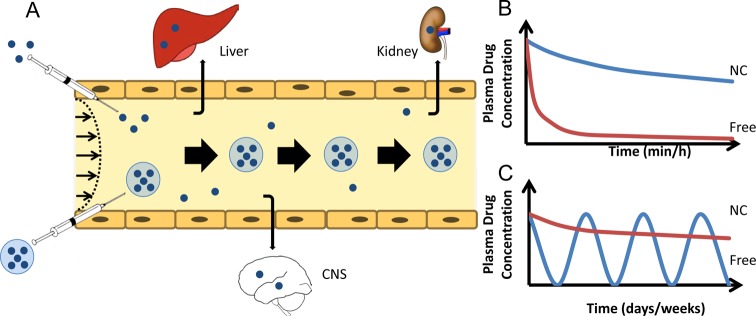

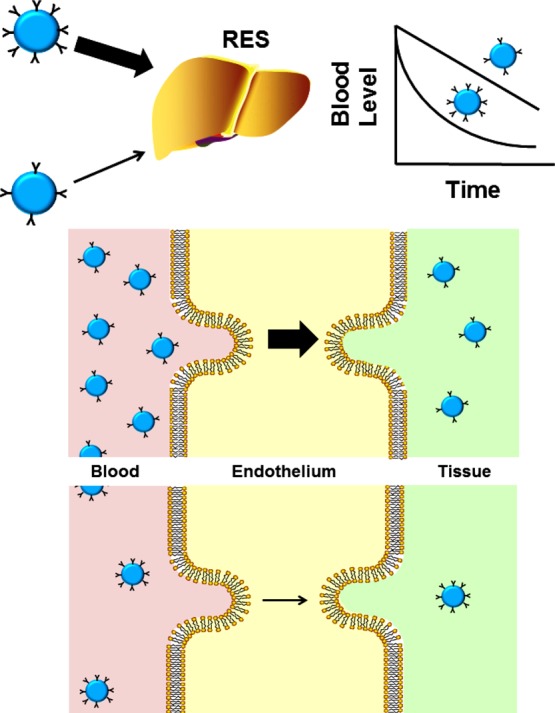

Figure 1.

Drug delivery by nanocarriers: optimization of drug pharmacokinetics and biodistribution (PK and BD). (A) PK and BD of drugs (blue dots) vs drugs encapsulated in nanocarriers. Free drugs are eliminated from blood by clearing organs, including the reticuloendothelial system (RES, including liver, spleen, and lymphatic nodes) and excretory organs such as kidneys, lungs, and the bile tract (including hepatic uptake and renal filtration), and diffusion in nontarget tissues including the brain (CNS), where drugs may cause adverse effects. Long-circulating nanocarriers avoiding clearance alter PK (large arrows depict sustained drug circulation) and reduce diffusion in nontarget tissues, thereby improving BD and inhibiting adverse effects. Relative dimensions in this and other cartoons and schemas are not to scale. (B and C) Panels represent, respectively, short-term and long-term model graphs of blood level of free vs nanocarrier-bound drugs (NC). After a single injection in acute and subacute conditions, long-circulating NCs enhance area under the curve, thus reducing the effective dose (B). Hypothetically, using NCs with extended lifetime in circulation will help to maintain a stable therapeutic dose without the need for repeated injections (C).

DDS and drugs are eliminated by the reticuloendothelial system (RES, including liver, spleen, and lymphatic nodes) and other tissues—kidneys, lungs, and the bile tract.25,26 A carrier can “passively” accumulate in a desired sites. For example, particles in the size range ∼10–200 nm tend to accumulate in tumors and inflammation foci due to enhanced permeability of pathological vasculature25,27 (Enhanced Permeation and Retention, EPR, Figure 2B). Nonspecific retention of carriers in the microvasculature is another example of “passive targeting”28 (Figure 2C). It is exemplified by perfusion imaging using mechanical entrapment of particles with diameter 20–50 μm29 and delivery of plasmid DNA using cationic liposomes that bind to negatively charged vascular cells.30 Delivery is enriched in areas downstream from the site of injection, where released drug is removed by blood. “Passive targeting” provides little, if any, guidance in cellular delivery.

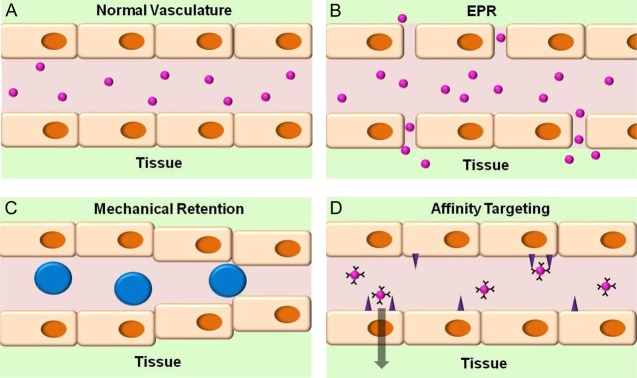

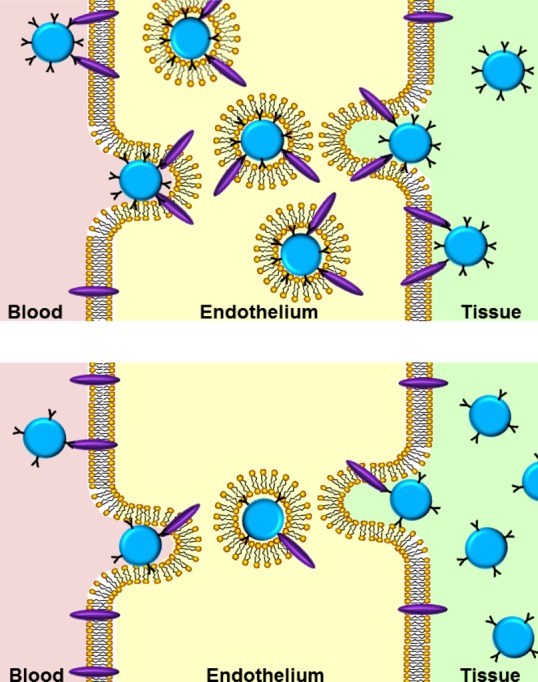

Figure 2.

Passive uptake vs active targeting: differences in mechanism and potential biomedical utility. (A) Untargeted nanocarriers with size ranging from a few to a few hundred nanometers do not normally accumulate in healthy tissue with blood vessels lined by the continuous endothelial layer lacking large fenestrae typical of the reticuloendothelial system (RES). (B) Enhanced Permeation and Retention (EPR) effect. In this scenario, carriers accumulate in tissues with abnormally permeable vessels, such as in tumors fed by leaky vasculature as well as in sites of inflammation and angiogenesis (for example, wound healing). In tumors, deficient lymphatic drainage also favors the EPR effect, while high interstitial pressure opposes it (not shown). (C) Large particles, such as rigid spheres with diameter 10–50 μm (bigger than that of capillaries and precapillary arterioles), are mechanically retained downstream of the site of arterial injection in the microvasculature of an organ or tissue fed by this conduit artery. (D) Active targeting of nanocarriers coated by affinity ligands of specific determinants favors binding to endothelial cells exposing these determinants. In contrast with passive uptake (B and C), this mode guides subcellular delivery: binding to noninternalizable molecules vs those involved in cellular uptake and trafficking, respectively, favors retention on cell surface vs intracellular or transcellular delivery.

“Active targeting” is a more precise approach (Figure 2D). It uses ligands that bind to molecules uniquely present or enriched in a cell, tissue, or pathological structure of interest (target determinants). Antibodies and their derivatives including single chain antigen binding fragments (scFv), nutrients, hormones, receptor ligands, peptides, aptamers, and nucleic acids have been explored as targeting ligands.31−35 Targeting involves DDS delivery to the target site, initial physical contact, anchoring, residence on the cell surface or internalization, and excretion or storage.36−41

Vascular Endothelium: Drug Delivery Barrier and Destination

Intravascular injection, notwithstanding its downsides, is a preferable route for drug carriers, and their encounters with endothelial cells lining the vessels are involved in practically every conceivable drug delivery paradigm31,42,43 (Figure 3). Carriers designed for prolonged circulation must avoid binding to endothelial cells to minimize carrier’s elimination, danger of impeding blood flow and adverse effects via perturbation of these cells44,45 (Figure 3A), which exert important functions.46−48

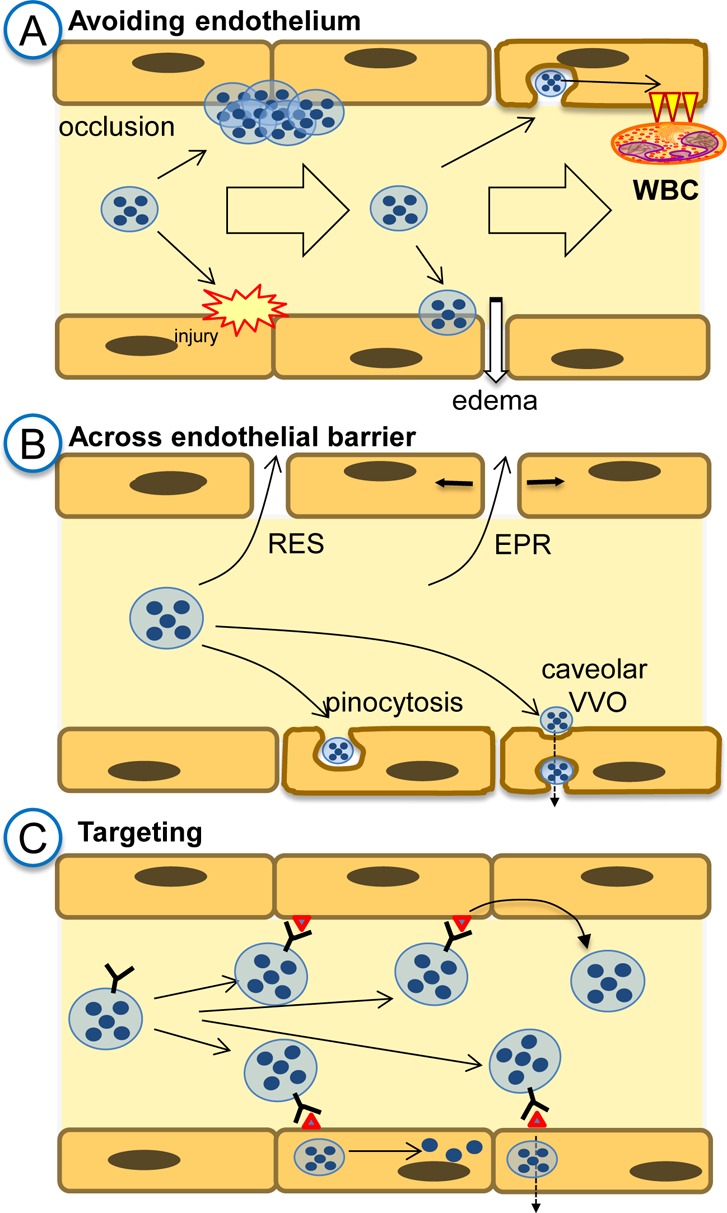

Figure 3.

The vascular endothelium: a victim, barrier, and target of drug delivery. (A) In drug delivery strategies requiring cargoes to be released or act in the bloodstream, such as long-circulating reactors or slow release systems, respectively, carrier interaction with endothelium must be avoided. Otherwise, carriers adherence to endothelium may lead to vascular occlusion, endothelial damage, or pathological activation. (B) In strategies delivering drugs to the extravascular sites, endothelium is a barrier. Carriers may cross it by concentration gradient via large opening between endothelial cells in the RES (e.g., fenestrae) and intercellular openings in abnormally leaky vessels in tumors and sites of inflammation and angiogenesis (EPR). Vesicular transendothelial pathways include fluid phase transport via pinocytosis and transendothelial vacuolar–vesicular organelle (VVO) that opens from the caveolae. (C) In strategies targeting drug carriers to the endothelial surface determinants, ligand-mediated anchoring may result in surface retention or internalization. Depending on the nature of anchoring molecule, choice of epitopes, and carrier design, internalization may lead to recycling to the vascular lumen, delivery to the intracellular compartments, or transfer across the endothelium.

The endothelium controls vascular permeability.49 In the vascular sinuses of the RES organs, interendothelial openings are patent for micrometer-size objects. In lungs, heart, skin, mesentery, muscles, and most of other vascular areas, the endothelium transports particles in the range of ∼50–500 nm via dynamic intercellular gaps and transcellular fenestrae and vacuolar pathways initiated in endocytic vesicles.50,51 These pathways are restricted in cerebral vessels (the blood–brain barrier, BBB),52 where transport occurs via specific receptors and transporters. In conditions such as inflammation, thrombosis and ischemia, vascular permeability increases, mostly due to endothelial contraction widening pericellular gaps. Veins (especially venules53) and capillaries are more permeable than arteries.39,54−57 Pathological vascular leakiness in tumors and inflammation foci favors DDS transport to these sites, while transcellular pathways support passive extravascular delivery in normal vasculature54,58,59 (Figure 3B).

The endothelium controls the following: (i) blood fluidity and hemostasis; (ii) vascular tone, signaling, and angiogenesis; and (iii) trafficking blood cells.47,48,60 Its abnormalities are implicated in the pathogenesis of ischemia, thrombosis, inflammation, tumor growth and metastases, diabetes, hypertension, stroke, atherosclerosis and other maladies. In these conditions, endothelial cells represent therapeutic targets (Figure 3C).38,43,61,62 Yet, drugs and DDS have no natural affinity to endothelial cells. Conjugation with endothelial ligands enables delivery to, into, or across these cells (e.g., “vascular immunotargeting”, Figure 3C).63−68 Since the late 1980’s, numerous groups have pursued this strategy.68−77

Endothelium is more accessible to circulating agents than many other targets such as extravascular tumor cells. Yet, endothelial targeting has its own challenges. For example, concerns about side effects are more serious in endothelial relative to tumor targeting. Diverse medical goals require distinct and precise subcellular addressing of cargoes delivered using endothelial targeting. For example, fibrinolytics need to be anchored to the luminal surface, enzyme replacement therapies for storage disorders need to be delivered into the lysosomes and antitumor agents need to go across the endothelial monolayer (Figure 3C).33,63,68,78

Many chronic conditions involving the endothelium (e.g., hypertension, atherosclerosis, diabetes, and arthritis) do have pharmacological options, tempering the enthusiasm for development of complex targeted DDS that may cause problems when used repeatedly. Acute, life-threatening conditions lacking effective therapeutic options (e.g., sepsis, acute lung injury, ischemia, infarction, thrombosis and stroke) provide a more attractive clinical context for endothelial nanomedicine. We focus on circulation, cellular binding and transport of carriers targeted to endothelial cells, envisioned for use in these acute conditions (and, perhaps, beyond). For the sake of cohesiveness, we present here a discussion of drug delivery, not imaging, applications–despite this being a tremendously important and extensively developed area.79−89

Nanocarrier Behavior in the Circulation

To deliver drugs to endothelial cells, carriers must circulate in the bloodstream for a period of time sufficient for distribution in the vasculature. This time is less than a minute in animals with a high heart rate and small blood volume, but varies from several minutes to tens of minutes in humans, depending on their health status. Characteristics of carrier design and biological factors control its pharmacokinetics and biodistribution (PK and BD) and influence targeting.

The pace of binding correlates with carrier avidity, concentration, perfusion rate, and the density of binding sites. Avidin-coated particles bind to biotinylated surfaces almost instantaneously due to their extraordinarily high avidity,90 while antibody-coated carriers perfused over endothelial cells require minutes to hours to achieve sufficient interactions with target cells that allow for firm adherence to the cell.91−94 Further, endothelial targets that appear in the pathological sites may require more time for binding due to inefficient perfusion. Conversely, a carrier’s ability to circulate for a prolonged time, find the intended vascular network and bind to newly exposed molecular signatures of vascular pathology would be of great diagnostic and therapeutic utility.

Carrier Circulation in the Vascular System

The intravenous routes bypassing the liver direct the first pass of blood to the lungs.95 The pulmonary vasculature represents ∼25% of the total endothelial surface in the body and collects the entire cardiac output of venous blood from the right ventricle, whereas all other organs share the arterial output of equal volume. A local intra-arterial infusion via a catheter advanced to the conduit vessel favors first-pass carrier interaction with vascular cells in an organ or a vascular area downstream the vessel.95,96

Microvasculature (arterioles, capillaries, and venules) is the preferable target for endothelial nanomedicine. Extended luminal surface area, micrometer-scale vessel caliber, and low flow rate favor interaction of particles with endothelium in this vascular segment. Hydrodynamic conditions in arteries (high shear stress and pulsatile flow) are less favorable for particle interactions with endothelium than in veins. A significant (if not predominant) fraction of transport from blood to arterial walls occurs from the vasa vasorum, i.e., the microvascular network in the external adventitia layer.84,97−102

The nature of the flow and perfusion govern particle behavior in the bloodstream. Laminar flow carries particles with minimal frequency of collisions with vessel walls. At sites of disturbed flow and turbulence, either physiological (vessel bifurcations, heart chambers) or pathological (atherosclerotic plaque, aneurism, coarctation), carriers are more likely to collide with the endothelium. Therefore, carrier delivery to sites involved in or predisposed to pathology is naturally favored. For example, micrometer-sized carriers composed of polymeric nanoparticles that dissociate under high shear stress accumulate in site of vascular stenosis.103 However, perfusion insufficiency downstream of an obstruction caused by vasospasm, thrombus, or surgical ligatures diminishes carrier delivery to ischemic zones. In addition, blood stasis inhibits delivery to vasculature above the occlusion site.

Carrier Longevity in Circulation: Surface Properties, Stealth Coating, and Ligand Attachment

Particles, similar to dead cells and their fragments, are marked for elimination from the circulation by opsonization, i.e., adsorption of immunoglobulin, complement, and other plasma components that stimulate uptake by phagocytes in the RES and other tissues.104 Unless protected (see below), carriers are eliminated quickly following their injection.104,105 Generally, hydrophobic and charged carriers are opsonized and eliminated more rapidly than their hydrophilic and neutral counterparts.106

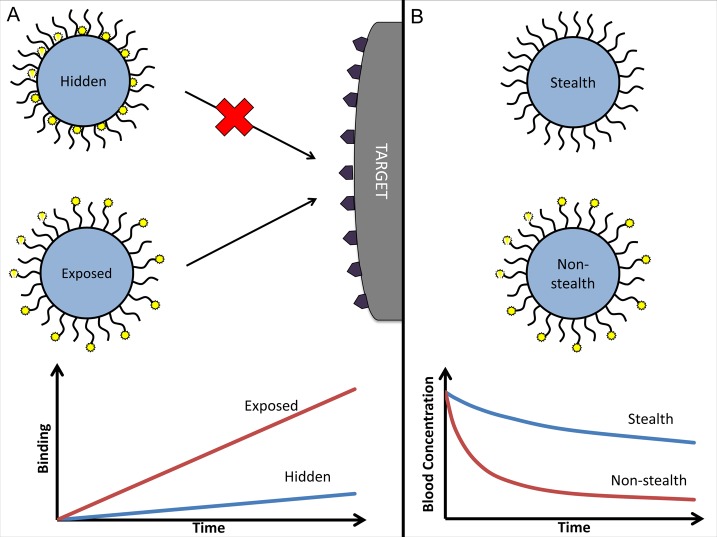

Coating with hydrophilic molecules (e.g., poly(ethylene glycol), PEG) that form a hydrated shell decelerates opsonization, inhibits a carrier’s interaction with phagocytes and other cells,107 and extends circulation lifetime.108 However, PEG chains may inhibit interactions of ligand molecules immobilized on the carrier with the target (Figure 4A). Both the masking and stealth effects are proportional to PEG chain length109 and surface density.110 Ligand conjugation via PEG alleviates the masking effect.109−111 Furthermore, ligand conjugation via PEG provides a flexible spacer that may improve the ligand steric freedom for interactions with target components (unless the spacer is so extended that it can “fold in” hiding the ligand).112 Conversely, conjugated ligand molecules diminish the stealth features of PEG coat (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Balancing the stealth and avidity features of carriers: effect on targeting and PK. (A) Surface modification by hydrophilic polymeric chains (e.g., PEG) provides a carrier with stealth features but affects targeting via masking affinity ligands. Conjugation of ligand molecules to the end groups of polymeric chains instead of the carrier surface helps to avoid this negative interference and provides additional steric freedom for ligand–target interaction, thereby boosting binding. (B) Ligand molecules conjugated to PEG diminish its stealth effect via nonspecific interactions (e.g., mediated by altered charge or hydrophilic features) and ligand-mediated interactions (e.g., via Fc-fragment of antibodies conjugated to PEG). Ensuing acceleration of blood clearance may affect drug delivery, if a carrier’s circulation time is insufficient for targeting.

A carrier’s stealth and targeting features may be optimized by conjugating corresponding moieties using linkers responsive to local stimuli of the target environment, such as temperature, pH, or proteolytic activity. For example, PEG conjugated via a cross-linker stable at physiological plasma pH 7.4 but labile at acidic pH will shed from a fully stealth carrier once it arrives at the acidic target site, therefore exposing ligands for binding.113 Practical implementation of “environmentally” sensitive nanocarriers depends on fine-tuning the dynamic range of their response. For example, unrelated proteases may impede the tissue selectivity of proteolytic transformation of carriers by enzymes preferentially active at target sites, such as a specific metalloproteinase. It is also difficult to fine-tune a carrier’s response to smaller pH changes, such as pH 6.0–6.5 vs <4.0, typical of ischemic and inflamed vasculature vs lysosomal vesicles, respectively.114

PEG is generally viewed as a biocompatible compound. Yet, the human immune response to PEG needs to be carefully assessed. PEG antibodies have been shown to form upon repeated administration of PEGylated compounds in animals.115,116 This phenomenon has been shown for a variety of carriers, ranging from proteins to liposomes.117−120 One possible mechanism for the accelerated blood clearance of PEGylated carriers upon repeated administration is the initial generation of anti-PEG antibodies (IgM) in the host,115 which persist in serum and bind to reinjected PEGylated carriers, reducing the circulation time. This initial anti-PEG IgM generation occurs in the spleen121 and likely involves B-cells,122 as B-cell deficient mice do not exert accelerated clearance of PEG-coated carriers.123

Coating carriers with molecules inhibiting activation of complement, opsonization, and phagocytosis such as sialic acid-containing glycolipids has been also pursued.124−126 More recently, specific biologically inspired means have been used to endow natural stealth properties to particulate carriers. For example, cells contain a membrane glycoprotein CD47, which interacts with receptors of macrophages eliciting signals that inhibit phagocytosis.127 Conjugation of CD47 and CD47-derived peptides to carriers helps to evade clearance via this natural “self-recognition” mechanism.127−130 Another approach to increase blood persistence of carriers is coating with fragments of cell membrane. Model PLGA carriers coated with mouse red blood cell (RBC) membranes circulated twice as long as PEGylated PLGA particles.131 In a similarly inspired study, leukocyte membrane coating inhibited carrier association with phagocytes and reduced hepatic uptake at short time points (<60 min) in vivo.132

Carrier Geometry and Plasticity

Neither too small nor too large particles circulate well. Renal filtration eliminates particles smaller than 10 nm.133 In addition, they extravasate via transendothelial fluid phase transport pathways,134,135 leading to elimination in skin, lungs, mesentery, muscles, and other tissues with extended surface of fenestrated microvasculature. On the other hand, particles larger than ∼500 nm are mechanically entrapped in capillaries.136 Agglomeration mediated by plasma components likely further enhances the latter outcome.

Carrier shape is an important factor of its behavior in the circulatory system and targeting.137 This is an area of research of astonishing complexity in every aspect: synthesis and quality control of carriers, rheological modeling and analysis, and appraisal of the biological relevance.138−141 The fundamental finding, confirmed in animal studies, is that elongated carriers of an appropriate size align with blood flow and have prolonged circulation in the bloodstream.142 For example, polystyrene elliptical disks with a maximal dimension of up to a few micrometers display a higher level in blood and lower nonspecific uptake in organs than spherical counterparts of a smaller size.143

One reason for the prolonged circulation of elongated objects is that they elude uptake by phagocytes.144 Macrophages internalize opsonized disk-shaped particles contacting the cell by the rounded end of the particle as effectively as spherical particles but cannot completely internalize disk-shaped particles contacting on their flat face (Figure 5).145 In support of the notion that nonspherical geometry may inhibit phagocytosis, filamentous particles coated with phagocytosis-promoting ligands were able to avoid phagocytosis by macrophages in cell culture.144

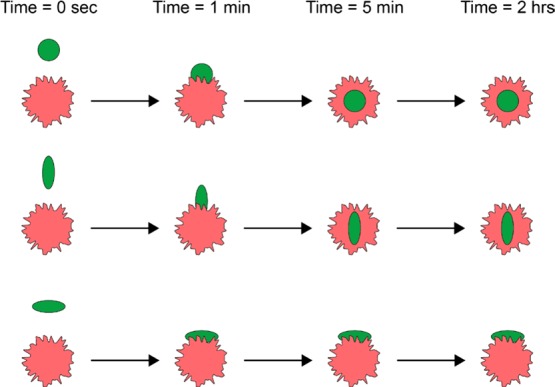

Figure 5.

Carrier geometry modulates cellular uptake. Rate of intracellular uptake of elongated particles by phagocytic and other cells is markedly modulated by the axis of the particle binding to cell surface: it is faster than uptake of spherical particles of comparative maximal dimension in cases of binding via pointed vs flat aspects, respectively.

Carrier flexibility also has an important influence on circulation and targeting. Rigid elongated particles (rods, disks, tubes) larger than a few micrometers quickly become entrapped in the microvasculature in vivo. However, carriers with sufficient plasticity to reversibly change shape in response to hydrodynamic factors and vessel narrowing, can pass through the microcirculation, thereby imitating erythrocytes: ∼7 μm discs that repeatedly squeeze through capillaries with 1–2 μm lumen and effectively avoid clearance by immune cells.146 Indeed, red blood cell mimetic particles were shown to have extended in vivo circulation times.147 Flexibility was tuned via the extent of cross-linking and resulted in plasticity similar to that of red blood cells.148 Enhancing carrier’s flexibility prolongs its circulation.147 Follow-up studies with similarly flexible particles varying in size have shown that particles closer in diameter to red blood cells have prolonged circulation half-lives.149

Elongated flexible carriers have also been developed. Filomicelles are a distinctive subset of micelles made of amphiphilic block copolymers that assemble in flexible flow-responsive filaments.150,151 Filomicelles are able to persist in blood for extended periods of time by taking advantage of both their worm-like shape and cell-like flexibility. Their ability to align with blood flow and avoid immune system clearance enables them to persist in circulation for days, which is up to 10 times longer than their spherical counterparts.151 Pristine filomicelles exhibit little to no cellular binding, an attractive feature for a long-circulating DDS.152

Challenges and Perplexing Issues

Studies of carrier behavior in vivo are challenging and prone to artifacts. Often, researchers bypass them and test in vivo effects of drugs loaded in DDS characterized only with a variable degree of scrutiny in vitro, betting that observation of a desired effect exceeding that of “untargeted drug” provides a mandate to publish “proof of concept” papers.153

However, effects in animals are of limited value if the mechanism of delivery and effect of the DDS is not known. PK and BD directly influence targeting, and vice versa. It is essential to compare the PK and BD of targeted vs untargeted carriers formulated identically and coated by scrambled or inactive ligand (control IgG of corresponding type is a reasonable control for targeting antibody). Pristine carriers are not a proper control (different size, charge, surface features, etc.). Carriers with ligands conjugated to PEG have shorter PK and different BD vs pristine PEGylated carriers (Figure 4). All these factors may alter the therapeutic/side effects of a ligand-coated vs uncoated carrier by mechanisms distinct from targeting.

Preferential uptake in the target site may originate from mechanisms irrelevant to the ligand, e.g., passive retention of aggregated particles or interactions with blood components that may serve as “endogenous targeting agents” (lipoproteins, transferrin, immunoglobulin, blood cells, etc.). Competitive inhibition of targeting by injected free ligand may be complicated by different PK/BD and avidity of free ligand vs those of ligand-coated carriers, or simply because an effective competitive concentration in blood is above a realistically achievable one.

Thus, a quantitative analysis of PK/BD is essential; however, its implementation is not always feasible. Optical methods reveal nanoparticles in tissues at the microscopic level at post-mortem and at macroscopic level in real time (in sufficiently transparent sites)154 but do not provide accurate quantitative measurements in the body. Isotope imaging including PET is not limited by tissue penetration and affords real-time longitudinal analysis,155−158 but quantitative measurement of signals in organs is convoluted by factors including overshadowing by sites with high basal uptake. The resolution of isotope imaging is insufficient to analyze cellular distribution.

Another issue that is associated with this field is that labeling of labile components of a nanoparticle can lead to artifacts of their dissociation in the body. Labeling ligand moieties is prone to artifacts of tracing detached ligand leading to overestimating targeting. Noncovalent intercalation of hydrophobic labels in carriers is marred by artifacts of their redistribution in cellular membranes and other biological sinks, such as lipoproteins. Ideally, both the cargo and carrier should be stably traced by conjugated labels. A direct stable conjugation of isotopes to polymeric matrix allows tracing of the carrier within a reasonable time frame from a few hours to a few days, usually sufficient for vascular targeting.159

A direct measurement of the isotope level in drawn blood samples is arguably the best method for PK studies.74,76,90,160−162 Admittedly, extensive experimentation is needed to characterize the kinetics of targeting. Nevertheless, this simple approach affords the most accurate quantitative analysis of preclinical PK/BD. It yields the key parameters of targeting and BD: percent of injected dose (%ID) in tissues, localization ratio (LR, or ratio of %ID per gram of tissue to that in blood), and immunospecificity index (ISI, or ratio of LR for targeted vs untargeted formulations normalized to their blood levels).76,163 Injecting in the same animal a mix of targeted and untargeted formulations labeled by different isotopes is a useful maneuver to account for individual variability and significantly reduce the necessary efforts. Carrier PK/BD must be normalized to the injected dose. DDS heterogeneity is a serious problem. A fraction of large particles in a formulation may be eliminated within seconds by mechanical retention and not accounted for by normalizing data to “initial” level detected in blood post-injection.

Further complication in studying the interactions of DDS is that the behavior of nanoparticles in vivo can be drastically different than that in vitro. Nanoparticles bind blood components, aggregate, and dissociate.164 Even dense PEG-coating of polymeric carriers does not prevent eventual absorption of plasma components.165 Generally, carrier interactions with body components166 influence desired as well as adverse effects, including accumulation in the target and uptake by off-target cells.167,168 Yet, these processes remain poorly understood: there are limited studies on carrier behavior in blood even in vitro (e.g., DLS measurements in plasma are not informative). The methodology of studying nanoparticles in vivo also continues to evolve: a recent study employed a new high-throughput approach to study deposition of plasma proteins on model polymeric particles.169 Better analytical techniques are necessary to understand these interactions. For example, the use of citrate anticoagulated plasma in such studies is questionable because many mechanisms are not active in such a specimen, as opposed to serum.170−172

Generally, advanced approaches for characterization of DDS behavior in vivo are needed to provide objective and accurate information on carrier PK/BD. Such data will provide valuable insight about targeting efficacy, kinetics, and specificity. It will also shed light on the mechanisms of cell-specific interactions.

Carrier Binding to Endothelium

Anchoring to specific cells is a key step in targeting. It is controlled by ligand affinity and configuration (surface density, interactive freedom, etc.) as well as other features of the nanoparticle (size, charge, PK/BD, geometry, plasticity, etc.). Equally important are target features: surface density, clustering and accessibility of binding sites, phenotypic characteristics, and the microenvironment of target cells (perfusion, pH, protease activity, etc.). Carrier interactions with target determinants govern the specificity, selectivity, efficacy, fate, and safety of the DDS.

Endothelial Determinants for Nanocarrier Targeting

A target determinant should ideally meet the following criteria: (i) it anchors a carrier to endothelium in the area of interest; (ii) it provides desirable subcellular addressing; and (iii) it is not adversely affected by carrier binding in the context of disease treatment.

Selective proteomics of the endothelial plasmalemma64,173 and in vivo phage display73 are advantageous for finding new targets, as they identify binding sites accessible from circulation in normal174 and pathological vasculature.175 The list of endothelial determinants theoretically useful for vascular drug targeting continues to grow.75,176−178Table 1 briefly outlines the main features of the most intensely studied and promising candidates; more details are provided in this section.

Table 1. Endothelial Determinants: Selected Candidate Targets for Drug Deliverya.

| target | vascular localization | cellular localization | functions | regulation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constitutive | ||||

| ACE (CD143) | Ubiquitous, enriched in the lung capillaries | Cell surface, single pass type I membrane protein | Plays a key role in rennin-angiotensin system, regulates blood pressure. Converts Ang I into Ang II and degrades bradykinin. | Catalytic activity is increased by chloride. |

| TM (CD141) | Ubiquitous, specific for endothelial cells | Cell surface, single pass type I membrane protein | Receptor for thrombin, participates in the generation of activated protein C. | Oxidative stress, hypoxia, oxidized LDL, C-reactive protein, phorbolesters, cAMP, and TNF tend to downregulate TM expression. Thrombin, VEGF, retinoic acid, and heat shock upregulate TM. TM level reflects a balance between those opposite forces. |

| Cell Adhesion Molecules | ||||

| PECAM-1 (CD31) | Ubiquitous | Cell junction, lateral border recycling compartment | Leukocyte transendothelial migration; antiapoptotic repulsion signaling from phagocyte | Stable expression |

| ICAM-1 (CD54) | Ubiquitous | Tetraspanin microdomains on cell surface, single pass type I membrane protein | Leukocyte firm arrest and transendothelial migration; immunological synapse formation. Ligand of LFA-1, MAC-1 | Up-regulated in inflammation |

| VCAM-1 (CD106) | Inflamed vascular endothelium | Tetraspanin microdomains on cell surface, single pass type I membrane protein | Leukocyte firm arrest and transendothelial migration. Ligand of VLA-4 | Up-regulated in inflammation |

| E-selectin (CD62E) | Inflamed vascular endothelium | Cell surface, single pass type I membrane protein | Leukocyte rolling | Up-regulated in inflammation |

| P-selectin (CD62P) | Inflamed vascular endothelium | Cytosol: Weibel-Palade bodies of endothelial cells, alpha-granules of platelets | Leukocyte rolling | Upon activation by agonists transported rapidly to cell surface |

| Caveolar | ||||

| APP | Enriched in pulmonary vascular endothelium. Expressed in heart, liver, kidney | Enriched in caveolae on the luminal surface of endothelial cells; lipid-anchored to cell membrane | Metalloprotase that plays a role in inflammatory process; cleaves and inactivates circulating polypeptides such as bradykinin | Unknown |

| PV1 (PLVAP) | Expressed in majority of tissues | Endothelial fenestrations, caveolar membrane | Formation of stomatal and fenestral diaphragms of caveolae, regulation of microvasculature permeability | Up-regulated by VEGF in vitro |

| Angiogenesis Tumor-Related | ||||

| APN (CD13) | Vasculature of tissues that undergo angiogenesis and in multiple tumor types | Cell surface, single pass type II membrane protein; cytosol | Metabolism of regulatory peptides, processing of peptide hormones (angiotensin III and IV, neuropeptides, and chemokines) | Estradiol and interleukin-8 decrease APN activity in vitro |

| Integrins αvβ3, αvβ5, α5β1 | Enriched in tumor vessels and other types of angiogenesis | Cell surface | angiogenesis, tumor neovascularization, and tumor metastasis | αvβ3 is up-regulated by bFGF, TNF |

| αvβ5 is up-regulated by VEGF, TGF-a | ||||

| TEM1 (CD248) | Tumor endothelial cells | Cell surface, single pass type I membrane protein | Tumor angiogenesis | unknown |

EC,endothelial cells; ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; TM, thrombomodulin; PECAM, platelet-endothelial cell adhesion molecule; ICAM, intercellular adhesion molecule; VCAM, vascular cell adhesion molecule; APN, aminopeptidase N; APP, membrane-bound aminopeptidase P; TEM-1, tumor endothelial marker-1; PV-1, plasmalemma vesicle-associated protein.

Target Molecule Expression, Localization, And Accessibility

Not all endothelial target determinants are “endothelial-specific markers”, such as E-selectin. The utility for vascular targeting depends on relative levels in endothelial vs other cells accessible to blood. For example, ICAM-1 is expressed by fibroblasts, epithelial, and muscle cells at levels comparable with those in endothelium. Nevertheless, these extravascular cells are not accessible to circulating macromolecules and carriers and hence do not compete with endothelial targeting. In contrast, cytokine and transporter receptors are abundantly expressed on cells in blood, RES, lymphoid tissues, hepatocytes, and other compartments accessible to circulating DDS and, therefore provide very modest (if any) endothelial delivery.

Constitutive determinants (e.g., PECAM, ACE, and APP) are suited for prophylactic drug delivery. Some, including APP and ACE,27,28 disappear from the endothelium in pathological conditions, which inhibits targeting.179,180 Constitutive molecules stably exposed in the lumen, such as PECAM, can be theoretically used for prophylactic and/or therapeutic effects.161 In contrast to constitutive molecules, inducible counterparts expressed or exposed to the lumen in pathological sites (e.g., APN, TEM-1, VCAM-1, and selectins) are less likely to find prophylactic utility but seem preferable for diagnostic imaging and therapeutic interventions.39,65,68,71,181

With respect to localization in the vascular system, endothelial surface molecules fulfill the continuum ranging from pan-endothelial to domain-specific determinants (i.e., expressed throughout the vasculature or in certain vascular areas). Pan-endothelial targets (e.g., PECAM) can be used for systemic delivery to treat generalized conditions: sepsis, disseminated intravascular coagulation, or hypertension. The level of expression and surface density of many pan-endothelial determinants vary between organs and types of vessels. For example, ACE and thrombomodulin are expressed in the pulmonary capillaries at several fold higher level than in other organs, and antibodies to these molecules (anti-ACE and anti-TM) preferentially accumulate in the lungs.179,182,183 Domain-specific molecules, preferentially expressed in certain vascular areas, are attractive for local delivery. For example, inducible molecules APN and TEM-1 are upregulated in endothelium involved in angiogenesis in tumors and inflammation,184,185 whereas adhesion molecules VCAM-1 and selectins are expressed predominantly in sites of inflammation.186

Determinants differ with respect to preferential localization in domains in the endothelial plasmalemma.187,188 For example, PECAM and VE-cadherin are localized predominantly in cell–cell borders.189,190 VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 are found in tetraspanin microdomains of the cellular apical surface,191−193 special types of membrane “rafts” of distinct protein and lipid composition with a diverse array of function, including adhesion, proliferation, and immune cell signaling.194 Glycoprotein GP85 localizes in the luminal surface of the plasmalemma that belongs to a thin organelle-free part of endothelial cell separating alveoli from blood,195,196 and APP and PV-1 are located within caveoli.135 The location in the plasmalemma dictates the target accessibility, interference in cellular functions, and the fate of cell-bound DDS.

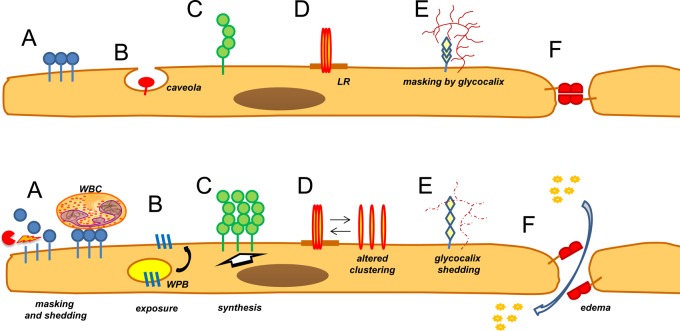

The endothelium is normally accessible to blood cells, lipoproteins, and other particles circulating in the bloodstream.43 Yet, accessibility to circulating particles varies dramatically among the endothelial surface molecules, depending on their localization in plasmalemma, location of the binding site epitope in the molecule, endothelial phenotype, and vascular conditions. Accessibility limitations are more stringent for carriers relying on multivalent binding and are proportional to the size of carriers. Epitopes located more proximally to the plasmalemma within the same target molecule are less suitable for harboring carriers than distal epitopes.197 Epitopes masked by the glycocalyx, buried in the intercellular junctions or in plasmalemma invaginations, are less accessible to affinity ligands and ligand-targeted DDS (Figure 6). Of note, shedding of endothelial glycocalyx induced by pathological mediators is implicated in enhanced accessibility of ICAM-1 to targeted carriers and activated leukocytes.198 On the other hand, adherent leukocytes may mask endothelial surface from blood.161

Figure 6.

Endothelial determinants in normal and pathological vasculature: accessibility, regulation, and localization in specific domains of the plasmalemma. (Upper panel) Normal endothelium exposes determinants that are differently accessible to circulating carriers. They include molecules clustered in apical plasmalemma, such as ACE (A); located in the caveoli, such as APP and PV1 (B); molecules, such as ICAM-1, expressed as monomers and oligomers at basal level throughout the plasmalemma (C); molecules preferentially localized in membrane domains (e.g., lipid rafts, LR) (D); molecules partially masked by glycocalyx (E); and molecules concentrated in cellular junctions, such as PECAM and VE-cadherin (F). (Lower panel) Under pathological conditions, determinants may be masked by adherent white blood cells (WBC) and/or shed from the cells (A) (both mechanisms would inhibit targeting), whereas inducible adhesion molecules may exteriorize from intracellular stores (B), such as P-selectin from Weibel-Palade bodies (WPB), or be synthesized de novo, such as E-selectin, ICAM-1, and VCAM-1 (C). Pathological mediators also induce rearrangement of natural clusters (D); shedding of glycocalyx, thereby exposing normally masked determinants (E); and cause endothelial contraction, thereby increasing pericellular permeability and accessibility of target determinants in the junctions (F), such as VE-cadherin and PECAM.

Target Function and Safety

Functions of target determinants are important in the context of drug delivery. Molecules involved in transport from the bloodstream seem attractive to deliver drugs in the corresponding addresses. On the other hand, interference with functions of target molecules must be considered in the context of pathological condition(s) to be treated. For example, ACE and APP are peptidases that cleave important peptide mediators (e.g., bradykinin);199 their unintended inhibition may cause harmful side effects, including vascular edema. Conversely, inhibition of angiotensin II production by ACE may be beneficial in management of hypertension and inflammation.

The issue of adverse inhibition of the target is illustrated by thrombomodulin, an endothelial surface glycoprotein that has been studied for targeting of diverse cargoes to the pulmonary endothelium in mice and rats.67,200,201 However, thrombomodulin controls thrombin,202 and its inhibition poses danger of thrombosis.201,203,204 This complication prohibits clinical use of this target, restricting its utility to model animal studies.180,201,205,206

Ligand-coated carriers may inflict more potent effects than ligands alone. Cross-linking of target molecules by a multivalent carrier may induce ill-understood or adverse signaling in the endothelial cells, shedding and/or internalization of target determinants, changes in their functionality, or other disturbances of the endothelium. With the exception of targeting anticancer agents to tumor endothelium, endothelial drug delivery should not damage or disturb target cells.

A more general aspect of this issue that should be considered is that biocompatibility of a single component does not guarantee safety of the nanocarrier.107 Loading a benign agent into a carrier composed of biocompatible materials decorated by innocuous ligands may yield a combination with pro-inflammatory or adjuvant features. Systemic effects, such as activation of complement, coagulation or platelets, and toxicity toward the clearing tissues (liver, kidney, lungs, etc.,), must be meticulously appraised in vivo.

Endothelial Cell Adhesion Molecules

Endothelial cell adhesion molecules (CAMs) represent arguably one of the most well-studied and versatile groups of endothelial determinants in the context of targeting nanocarriers.38,90,162,207 Inhibition of CAM-mediated leukocyte adhesion and signaling is generally viewed as safe in the context of many pathological conditions, except certain infections. Further, targeting to these molecules achieves localization of drugs to diverse endothelial compartments.

Inducible Endothelial Cell Adhesion Molecules

Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule-1 (VCAM-1), P-selectin, and E-selectin are exposed on the surface of activated endothelial cells and facilitate the rolling phase of the vascular adhesion of leukocytes.208 Pathological factors including cytokines, oxidants, and abnormal flow cause surface exposure of P-selectin from intracellular storage within 10–30 min209 and induce de novo synthesis and surface expression of E-selectin210 and VCAM-1.211 E-selectin and VCAM-1 seem to be expressed by the activated endothelium in arteries and skin microvasculature to a higher extent than in the pulmonary vasculature.212

Carriers conjugated with antibodies to these molecules bind to activated endothelium.66,71,212−215 Endothelial cells internalize selectins via clathrin-coated pits,216−218 which favors intracellular delivery into endothelial cells of E-selectin targeted liposomes,219 drugs,219,220 and genetic materials.221 Inducible adhesion molecules represent excellent determinants for visualization of activated endothelium in inflammation foci by delivery of conjugated isotopes181 or ultrasound contrast agents.222,223

Constitutive Cell Adhesion Molecules PECAM and ICAM-1

PECAM and ICAM (CAMs) are glycoproteins composed of a large extracellular region containing several Ig-like domains, a transmembrane segment, and a cytoplasmic tail mediating signaling.224,225 CAMs are present in cell types including platelets (PECAM), epithelial and smooth muscle cells (ICAM), and leukocytes (both), but among the cell types accessible to blood, surface levels of PECAM and ICAM are the highest in endothelial cells.

PECAM and ICAM are expressed on the endothelium throughout the vasculature. PECAM is stably expressed at a level of (0.2–2) × 106 copies per cell,211 predominantly in the interendothelial borders.226,227 ICAM tends to localize in lipid rafts in the luminal membrane and may exist in either a monomer or oligomer form.193 Quiescent confluent endothelial cells in static culture express ICAM at very low levels, and treatment with cytokines or thrombin leads to 50- to 100-fold up-regulation.228 In contrast to such a dramatic difference in vitro, ICAM is expressed in blood vessels constitutively by quiescent endothelium in vivo at levels of ∼(0.2–1) × 105 binding sites for anti-ICAM per cell, while cytokines and other pathological mediators induce its additional synthesis and upregulate ICAM-1 surface expression roughly twice to the level of (0.5–3) × 105 sites per cell in endothelium48 and other cell types.229

CAMs are involved in adhesion and trafficking of leukocytes and in vascular signaling.230 Their clustering by multivalent ligands initiates signal transduction via their cytosolic domains.231 Adhesion via these molecules supports leukocyte mobilization in sites of inflammation.230,232Via its extracellular domain, endothelial PECAM engages in heterophilic binding to heparin-containing proteoglycans and integrins of leukocytes, and in homophilic PECAM–PECAM interactions.231,233,234 The extracellular region of ICAM binds ligands including fibrin, certain pathogens, and integrins of activated leukocytes, mediating their firm adhesion to endothelial cells.235,236 Therefore, PECAM and ICAM are involved in cellular recognition, adhesion, and migration of leukocytes.237 Inhibition of these functions may be beneficial in treatment of inflammation.238

Affinity Ligands for CAM Targeting

PECAM and ICAM antibodies (anti-ICAM and anti-PECAM) are popular ligands for experimental vascular targeting. These antibodies and antibody-carrying carriers and drug conjugates bind to endothelial cells and accumulate in vascularized organs after intravascular injection.78,95,160,201,205,239−241 Intravenous administration favors their uptake in the pulmonary vasculature, while local arterial infusions enrich accumulation in the downstream cardiac,242 cerebral,96 and mesentery243,244 vasculature.

Many groups have devised nanocarriers targeted to CAMs by conjugated antibodies.245 “Designer” affinity ligands for CAMs have also been devised,40 including scFv fragments95,206,246 and affinity peptides selected using a phage display library.247 Advantages of using scFv include lack of Fc-fragment mediated effects and feasibility of scaled-up GMP production of recombinant constructs. A humanized monoclonal antibody binding to human ICAM with 50-times higher affinity than paternal mouse anti-ICAM has been produced248 as well as multivalent Fab fragments of a monoclonal antibody to human ICAM.249

Some of these recombinant proteins have been clinically tested as anti-inflammatory agents and showed generally acceptable safety.250,251 More recently, a short 17-mer linear peptide derived from one of ICAM’s natural ligands, fibrin, provided endothelial targeting of nanoparticles on par with ICAM antibodies in animal studies.252

This type of ligand offers the advantages of a reduced risk of immune reactions and utility in diverse animal species.

Carrier Binding to Endothelium

Targeting is controlled by carrier avidity, defined by ligand affinity, density, and freedom to interact with target.253 The carrier geometry and plasticity modulate the latter parameter and carrier ability to engage in multivalent binding.160,179 The binding is also controlled by target features (surface density, accessibility, and organization of epitopes) and hydrodynamics, which all may change under pathological conditions.

Hydrodynamics

Reviewing the extensive literature on rheological control of interactions of ligand-coated particles with the vessel wall, pertinent to both adhesion of leukocytes and carrier targeting, is beyond the scope of this paper. The majority of these studies involved particles of micrometer size and surfaces coated with immobilized molecules or endothelial cells in vitro.94,254−259 These models allow quantitative analysis under controlled conditions, but revealed trends need in vivo validation in the types of vessels260 and vascular areas261,262 of interest.

For example, several studies have indicated that binding is inversely correlated with shear stress.255,263 Computational analysis showed that the shear stress influence diminishes for nanocarriers coated with antibodies at a surface density above a threshold level.253 Modeling studies considering the contribution of buoyancy, hemodynamic forces, van der Waals, electrostatic, and steric interactions between circulating particles and the endothelium identified a critical diameter of 200 nm for which the margination time is maximal. It was proposed that carriers either larger or smaller than this size may have an advantage anchoring on the endothelium.264 Studies in a parallel plate flow chamber indicated that particles with a diameter greater than 200 nm undergo the most effective margination due to sedimentation in horizontal capillaries and lateral drift in vertical capillaries with downward flow, enhancing the likelihood of adhesion to the endothelium.265

Similar experiments in a flow chamber model evaluated binding of spherical particles ranging from 100 nm to 10 μm coated with endothelial ligand. Binding increased with an increase in diameter from 0.5 to 10 μm at a shear rate of 200 s–1 typical of arteries, whereas a further increase in shear favored binding of 2–5 μm particles.254 One explanation is that the dragging force of the highest shear stress applied to larger particles prevails over the adhesive force. Carriers experience the hydrodynamic dragging force of blood proportional to their size; hence, the larger the DDS is the more target molecules need to be engaged to anchor DDS on the cell.253 Spherical carriers (1 μm) coated with ICAM antibody displayed a typical pattern of binding to endothelium in vitro dependent on the antibody surface density: move in the flow at high speed without visible interactions with cells, roll continuously over cells, roll first and then bind firmly to cells, or roll first and then detach thereafter traveling along the cell surface.94

In some studies carriers were perfused in the presence of blood components.253 For example, RBCs are known to occupy the mainstream in high-shear vessels, expelling smaller particles to the marginal level, thereby directing their flow in the glycocalyx-protected layer and interaction with endothelial surface.266 Indeed, it was shown that addition of RBCs to the perfusion buffer stimulates binding of ligand-coated particles to the walls of target-coated model vessel.267 Recently, studies focused on the effect of circulating RBCs on carrier margination have shed light on an area known as the cell-free layer, which separates bulk RBC flow and the endothelial wall.268,269 Simulated binding, simplified as contact between carrier and endothelium, was performed in both large and small vessels in the presence and absence of RBCs. Due to the interaction of particle and cell, smaller particles are physically pushed by RBCs via volume exclusion. Likewise, an increase in particle dispersion coefficient is attributed to the increased rotation and tumbling of RBCs under increasing shear. These two contributions, increased particle dispersion and volume exclusion, act together to increase the carrier gradient along the cell-free-layer at the vessel walls. In smaller vessels, similar simulations show that carrier accumulation is enhanced further, likely due to the larger role volume exclusion plays since RBCs may be forced to physically contact the vessel wall.269

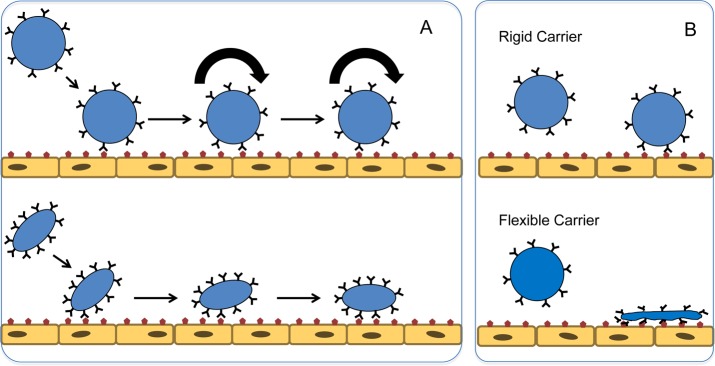

Carrier Geometry and Plasticity

As mentioned earlier, the carrier’s physical characteristics (e.g., shape) play a critical role not only in its circulation profile, but also in its binding to target cells. Studies with targeted DDS in vivo have shown that while endothelial localization may increase with size into the micrometer range, targeting specificity tends to have a maximum in the hundreds of nanometers range. A study comparing vascular targeting (through measurements of pulmonary uptake) of anti-ICAM coated polystyrene spheres with sizes of 0.1, 1, 5, or 10 μm showed that, while the overall %ID found in the lung increased with size, the targeting specificity decreased about 5 times (the ISI was ∼10 vs ∼2 for 100 nm and 1000 nm particles, respectively), due to more pronounced mechanical retention of large untargeted carriers coated with control IgG.143 Similarly, PECAM-targeted protein carriers showed increased pulmonary uptake with an increase in size from 200 to 800 nm, but nonspecific uptake of control nontargeted counterparts increased when the size was >300 nm.136

Carrier enlargement aggravates accessibility issues. For example, determinants located in caveoli, invaginations with neck diameter <50 nm, are accessible to relatively small ligands such as antibodies but not to submicrometer carriers.197,270 In a similar example, 100 nm spheres targeted by antibodies to well-mapped epitopes of endothelial PECAM failed to bind to the cells when the antibody to the most distal of the plasmalemma epitopes was used, while the antibody itself showed excellent binding.197

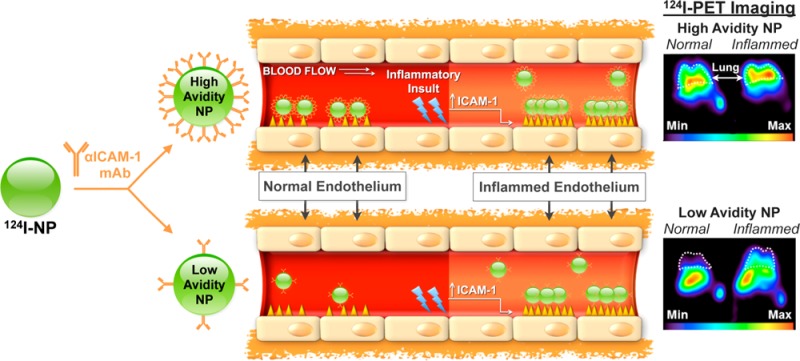

At a nanometer scale, it has been shown that elongated carriers bind to endothelium more effectively than spherical ones (Figure 7A). Specifically, polystyrene nanorods (aspect ratio ∼3) functionalized with anti-ICAM showed upward of 3-fold attachment to brain endothelial cells in static cell culture.271 Higher association of rod-shaped particles with endothelial cells was also exhibited in vivo as anti-ICAM coated rods exhibited ∼2-fold higher accumulation in target tissue (lungs) than that of spheres of identical volume. This was further investigated by coating nanorods and spheres with anti-transferrin-receptor monoclonal antibody. Rods exhibited almost an order of magnitude fold enhancement in attachment to brain endothelium.271

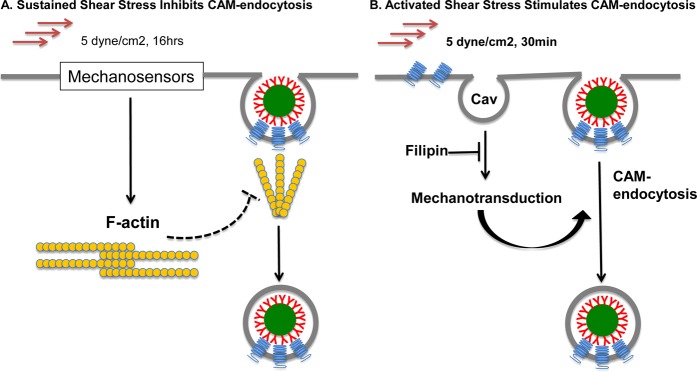

Figure 7.

Carrier shape and plasticity modulate ligand-mediated anchoring on endothelium. (A) Spherical carriers bind to the endothelium in a fashion reminiscent of the phases of leukocyte adhesion (rolling, initial tethering, and firm adhesion), whereas elongated and discoid carriers “zip up” on the target molecules. (B) Endothelial binding of flexible carriers is advantageous over that of rigid carriers, because shape change and lateral diffusion of ligands afford better congruency between molecules of a ligand/receptor pair and a higher number of productive anchoring engagements.

In a computational model comparing spheres and nanorods, the binding probability of a nanorod under a shear rate of 8 s–1 was found to be 3 times higher than that of its spherical counterpart. Anti-ICAM coated polystyrene disks showed enhanced targeting specificity over spheres (immunospecificity index, ISI, of 35.7).143 Previously discussed long-circulating filomicelles display a unique interaction with their target surfaces: biotinylated worm micelles were shown to “zip up” on avidin-coated surfaces due to their multivalent high affinity interactions.152 In comparing the in vivo targeting of ICAM-coated filomicelles and spheres, both resulted in similar specificity though the overall targeting was lower for filomicelles.90

Flow-induced interactions play an important role in binding of nanoparticles to endothelium. Several devices have been synthesized and mathematical models have been developed to investigate and explain these phenomena.264,271−276 Mathematical modeling has shown that rod-shaped particles are more likely to adhere to endothelium than their spherical counterparts under the same flow conditions due to the tumbling and rolling motions that rods will undergo near endothelial walls.277 Numerous studies supported by mathematical models by Decuzzi and Ferrari detail various advantages of nonspherical particles in cellular adhesion under flow: (i) oblate particles adhere more strongly to surfaces under flow273 and (ii) particles with radii under 100 nm, as is typically the case with elongated particles, are ideal for margination and interaction with the endothelium.264

These interesting mathematical predictions are supported by in vitro flow studies designed to mimic in vivo flow. Notably, discoid particles have been shown to marginate to the wall under flow better than their spherical counterparts.278 BSA coated rod- and disc-shaped particles have been shown to adhere up to 5 times more than BSA coated spheres to anti-BSA microchannels (bifurcation geometry),275 and anti-ICAM coated rods were shown to adhere twice as well to ICAM-expressing endothelial cells over identically coated spheres under flow.271

Carrier plasticity is likely to contribute significantly to targeting despite the lack of studies directly confirming this. While circulating in the fluid stream, rigid and flexible carriers may retain similar morphologies. However, the latter carriers may flatten on the surface of the target (Figure 7B), thereby reducing the drag force of perfusion that leads to detachment. The same phenomenon will enhance binding via spreading over and engaging a higher number of binding sites. Additionally, lateral movement of ligand molecules in the flexible carriers favors congruency of ligand molecules interaction with multiple binding sites and their clusters.279 These advantages of more flexible carriers are beginning to be reported in literature where ligand presenting carriers of the same shape and identical coating are superior in terms of binding and binding strength over their rigid counterparts.280 Perhaps these findings will be best exploited by high-avidity multivalent binding to target sites. In addition, as noted in section Nanocarrier Behavior in the Circulation, flexible particles circulate for a longer time and have a better chance of achieving target than rigid particles. Further, rigid particles have shown to be greater than 5-fold more likely to be internalized by immune cells when compared directly to their flexible counterparts in vitro.281 However, rigid particles also seem to preferentially accumulate in lung tissue much more than flexible counterparts, likely due to passive mechanical retention in lung capillaries.

The Optimal Carrier Avidity and Ligand Density

The mode of ligand conjugation modulates carrier’s avidity. For example, antimyosin Fab conjugates produced with three different cross-linkers (SMCC, SPDP, and BrAc-NHS) showed different targeting, likely due to different stability of the bond and reduction of Fab affinity, among other potential factors.282

The transformational shift of DDS binding, which usually boosts targeting, is from a monovalent or bivalent ligand to a multivalent carrier. For example, an effective avidity of binding to endothelium of anti-ICAM coated carriers is markedly higher than that of free anti-ICAM.243,283 Multivalent binding helps retain large particles that experience more powerful detaching forces than a ligand molecule. For example, computational analysis revealed that at least three ICAM antibodies coupled to a spherical carrier with diameter 100 nm should engage simultaneously in binding to an endothelial cell in order to anchor the carrier.94,253,284 The key issue, therefore, is to find an optimal ligand configuration on the carrier that provides multivalent interactions with target molecules.

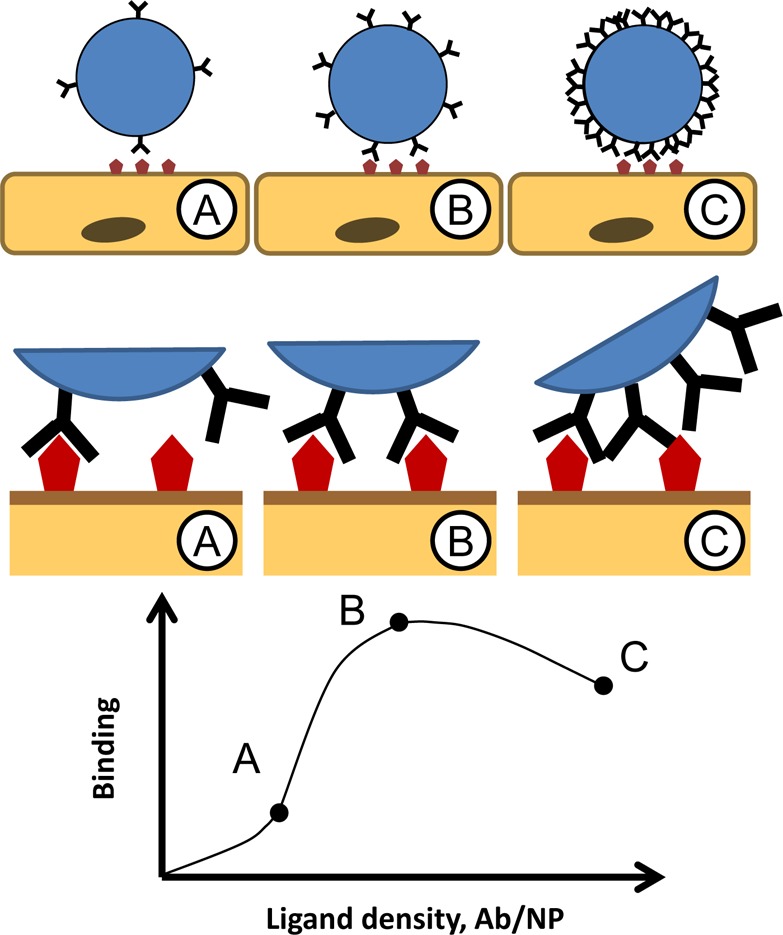

Generally, higher affinity/avidity is viewed as an advantage for targeting.285 For example, an increase in ligand density providing higher avidity results in an increase of vascular targeting.253,284 Conjugation of a number of ligand molecules per carrier less than a certain minimum leads to a failure of the carrier to bind to the target.284 Yet, an excessive ligand density beyond one that saturates binding sites may be undesirable due to costs and benefit/risk ratio.286 Additionally, studies of nanocarrier-based vaccines imply that carriers with high ligand density are likely to cause immune reactions.287−289

Furthermore, in some cases, ligands with higher affinity yield inferior targeting. One scenario where this is the case is when high-affinity nanoparticles fail to penetrate into the target due to their retention at the surface of the target mass, such as tumors290 or thrombi.291 Although such a scenario is less likely in endothelial targeting, there are additional complicating considerations. Unlike free ligands, ligand–drug or drug–carrier conjugates require congruency with target molecules for multivalent binding, which does not necessarily correspond to the maximal ligand density. In some cases, as illustrated in Figure 8, an excessive ligand density may inhibit the binding of NCs to target cells. In this phenomenon, “ligand overcrowding” on the surface of a NC could inhibit individual ligand molecules from achieving the optimal orientation or congruency with clustered target molecules favorable for binding.292,293 This phenomenon was also observed using nanocarriers targeted with aptamers intended for tumor delivery. Beyond a certain threshold, further elevation of ligand density resulted in a significant decrease in tumor localization.292,294

Figure 8.

Maximal ligand surface density does not necessarily provide optimal carrier targeting. (A) Suboptimally low ligand density negatively impacts a carrier’s ability to engage in multivalent binding, hence suboptimal targeting as depicted in the model graph. (B) Surface density of ligand copies at which they engage multiple binding sites and achieve firm binding is sufficient and optimal for targeting. (C) Excessively high surface density of ligand molecules may lead to “a ligand overcrowding” phenomenon, i.e., inhibition of multivalent engagement due to steric limitations and competition of adjacent ligand molecules for the binding sites.

Defining the optimal surface density of a ligand, which may vary depending on the features of a carrier, ligand, target, and application, is a daunting and important task. Several factors could contribute to the outcome including carrier and ligand properties (size, orientation, density, etc.) and characteristics of the target molecule’s environment (membrane localization, glycocalyx, clustering, etc.). Quantitative parameters of ligand affinity and surface density on a carrier have to be determined empirically because surface density and clustering of target determinants in vivo remain to be characterized.

Varying ligand surface density also may help enhance targeting selectivity. Often, so-called “specific” markers expressed on pathologically altered target cells are also expressed at lower levels in other areas of the body. Increasing avidity of a carrier beyond a certain threshold may result in an increase in “off-target” binding to normal cells expressing target determinants at a low basal level. Specifically, in the application of imaging and detection of disease, off-target uptake should be minimized to enhance the signal-to-noise ratio of the target tissue.

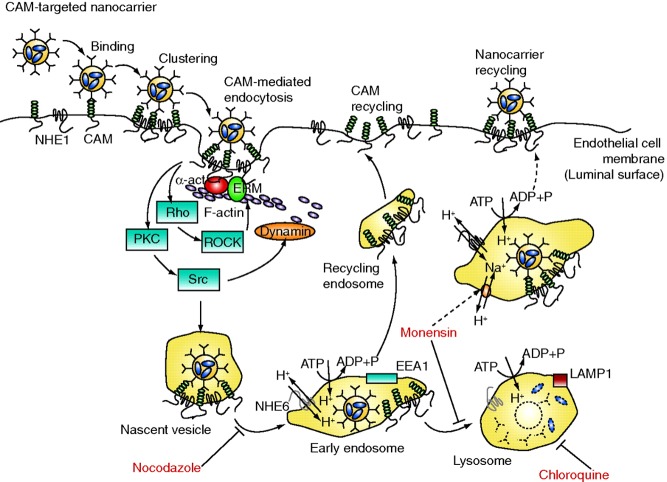

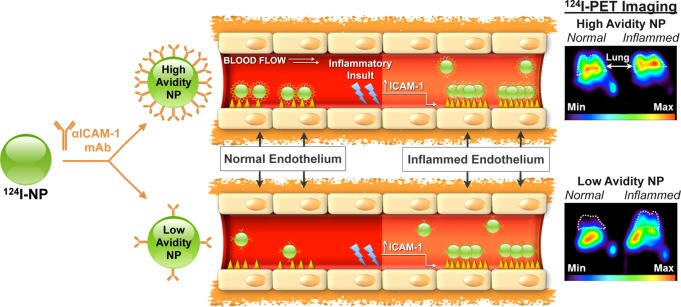

This point was validated in a study on molecular imaging of pulmonary inflammation by isotope-labeled anti-ICAM nanocarriers. Admittedly, ICAM-1 is not an ideal target for this goal, since it is expressed at a relatively high basal level among the normal endothelium, while its level roughly doubles in inflamed counterpart. In vitro studies in static and flow-exposed cell cultures, as well as computational simulation, showed that high-avidity nanoparticles anchor effectively to both naïve and activated endothelium, whereas low-avidity (i.e., low anti-ICAM density) carriers effectively engage in multivalent anchoring preferentially to inflamed endothelium.94,253Figure 9 illustrates the study that affirmed the in vivo effects of tissue selectivity. Specifically, lowering the carrier avidity using controlled reduction of anti-ICAM surface density resulted in a marked 2-fold increase in selectivity of uptake of anti-ICAM/carriers in the lungs of animals with endotoxin-induced acute pulmonary inflammation vs lungs of healthy control mice and improved detection of pathology using PET imaging.156

Figure 9.

Controlled reduction of avidity (ligand surface density) enhances selectivity of carrier targeting to pathological endothelium. ICAM-1 is exposed on quiescent and pathological endothelium at modest basal and elevated levels, respectively. Carrier avidity to ICAM-1 is controlled by antibody surface density. High-avidity particles (approximately 150 nm diameter) carrying 200 molecules of anti-ICAM effectively bind to both quiescent and inflamed endothelial cells and show high pulmonary uptake after intravascular injection in both naïve and endotoxin-challenged mice (upper cartoons). In contrast, low avidity particles carrying 50 anti-ICAM molecules show negligible binding to quiescent cells, whereas elevation of surface density of ICAM-1 typical of pathological endothelium allows their multivalent anchoring and binding to cytokine activated endothelium (lower cartoons). This phenomenon helps to explain the several-fold higher selectivity of targeting to pathological vs normal endothelium demonstrated by low-avidity vs high-avidity carriers in mouse model of lung inflammation (middle panels). As result, low-avidity anti-ICAM coated carriers provided PET images of the pulmonary inflammation in endotoxin-challenged mice that were more discernible from naïve animals than images provided by high-avidity carriers (far-right panels). PET imaging at 1 h after IV injection of ICAM-targeted [124I] carriers carrying either 200 or 50 antibody molecules per particle (upper vs lower images, respectively) in naïve vs endotoxin-treated mice (left vs right). White dashed-line corresponds to lung space. (Adapted with permission from ref (156). Copyright 2013 American Chemical Society.)

Targeting Vascular Damage

Damaged vascular wall exposes specific markers including normally hidden intracellular endothelial molecules (e.g., von Willebrand Factor) and components of subendothelial layers including collagens, tissue factor, and proteoglycans. These compounds activate coagulation and platelets to form a hemostatic plug preventing bleeding. To compensate for deficiency of natural hemostatic mechanisms in patients with bleeding disorders, development of synthetic hemostats has been investigated.295−297

These synthetic hemostats must be specific and not induce clotting at off-target endothelial sites.298 Hemostatic-promoting carriers must (i) circulate in blood without interacting with off target (i.e., nondamaged) endothelium, (ii) marginate to the endothelial wall at the wound site, and (iii) specifically interact with the damaged endothelium and circulating platelets to form a suitable hemostatic plug. Carrier design parameters become increasingly important if carriers are to perform such specific interactions in terms of circulation and endothelial interaction considering the exposure of multiple binding sites at injured vasculature and the dynamic nature of blood flow. To address the former, a number of spherical carriers have been proposed presenting either fibrinogen295 or fibrinogen-derived peptides,296,299 which bind to markers exclusively present on activated platelets at the wound site. These single-ligand carriers have been successful in providing an ∼2-fold increase in survival compared to saline control mice that were subjected to liver blunt trauma wounds.300 Recently, the complexity of multiple ligand presentation following physical vascular damage has been investigated by combining collagen and von Willebrand Factor binding ligands, in addition to fibrinogen-derived peptides, onto a single carrier.297

In case of the latter, the size, shape, and flexibility must be finely tuned in order to perform on-demand hemostasis at a vascular injury site which is undergoing dramatic changes in blood flow and loss. Extensive efforts have focused on mimicking the size, shape, and flexibility of RBCs to better navigate carriers in the vasculature. Likewise, platelet mimetics are receiving much attention. Recently, Doshi et al. have shown the utility of cell-like flexible particles in targeting surfaces coated with markers for damaged endothelium.280 Synthetic platelets, which mimic the size, shape, and flexibility of real platelets, were shown to adhere over 2-fold more strongly than spherical counterparts. This enhanced effect was attributed to a combination of features as similar spherical particles were unable to perform as well. Indeed, it has yet to be shown whether or not these synthetic cells will be able to marginate in blood flow or perform hemostasis as well as real platelets. Yet engineering of the shape and flexibility of carriers that has been demonstrated by synthetic RBCs,147 synthetic platelets,280 and filomicelles90,151 is required to perform complicated functions that spherical particles may not be able to address.

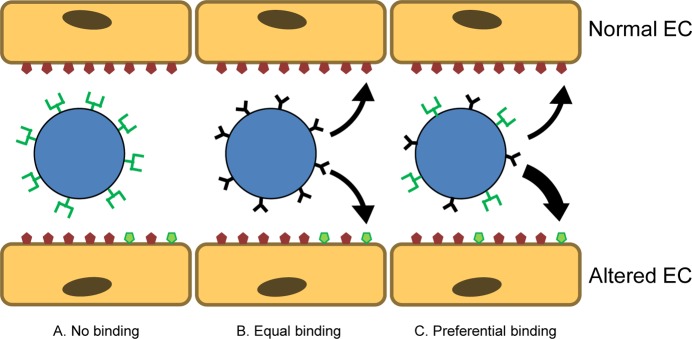

Multiligand Targeting

Selective targeting to pathological endothelium is an important task. One intriguing idea explored by several laboratories is the strategy of combining on the surface of the carrier affinity ligands that bind to different determinants. This has the potential to boost the selectivity and efficacy of drug delivery. Figure 10 illustrates this principle: one ligand binding to an inducible determinant provides the selectivity of recognition of altered cells, while the second ligand binding to a pan-endothelial determinant supports the anchoring. The idea, in essence, comes from the biology of leukocyte vascular homing and infiltration of the endothelium at sites of inflammation. Leukocytes bind to two different types of adhesion molecules, low-affinity selectins (E/P-selectin) and high affinity Ig-type cell adhesion molecules (PECAM and ICAM), in order to attach, roll, and come to firm adhesion on the endothelium.

Figure 10.

Carrier targeting using multiple ligands. (A) Carriers coated with ligands binding to endothelial determinants that are expressed in the area of interest selectively but scarcely (green) may have insufficient avidity for anchoring in this area. (B) Carriers coated with ligands binding to abundant endothelial determinants (red) anchor indiscriminately throughout the vasculature. (C) Carriers coated with a combination of two ligands may exert elevated basal avidity to endothelium, insufficient to provide a firm adhesion on its own but enabling binding in the case of simultaneous engagement of the scarce site-specific determinant.

In this vein, carriers coated by combinations of antibodies with relatively nonspecific high-density determinants (ICAM, PECAM) and antibodies to inducible adhesion molecules (selectin, VCAM-1, ELAM) have been tested in vitro in models that employ co-immobilized antigens257 or cytokine-activated cells.279 In studies with particles targeted to inflamed vasculature using ICAM-1 and P-selectin, greater binding was achieved with dually targeted particles relative to particles targeted to P-selectin or ICAM-1 alone.257,301,302 Targeting liposomes to E-selectin and either VCAM-1 or ICAM-1 on cultured endothelial cells has also been reported.279 Maximal binding was observed with equimolar ratios of both ligands.279,303,304 The biological significance of these findings to real situations in vivo remains to be defined. In addition to typical limitations associated with cell cultures and immobilized antigens, expression of binding data in relative scale further convolutes interpreting results of these studies.

However, a dual targeting strategy employing spherical 100–200 nm carriers carrying antibodies to both ICAM and transferrin receptors has recently been tested in vivo and showed promising results: each of the ligands apparently promoted targeting to the vascular area of its destination, i.e., nanocarriers could be directed to the inflamed pulmonary vasculature via ICAM and to cerebral vasculature via transferrin receptor.305

The dual targeting paradigm has also been used for molecular imaging: MRI-based NCs were targeted to P-selectin and VCAM to image atherosclerosis in mice. Dual targeted NCs demonstrated approximately a 6-fold higher binding relative to single targeted NCs.306 Another group has used dually targeted particles for imaging of inflammation via microbubble contrast agents for ultrasound. Here microbubbles were targeted to ICAM-1 and selectins and demonstrated that dually targeted bubbles had significantly better adhesion strength to activated endothelial cells relative to single target bubbles.307

Competitive and Collaborative Targeting

Monomolecular ligands interact with target determinants either in bivalent (e.g., antibodies themselves) or monovalent fashion (e.g., Fab-fragment conjugates and scFv-fragment fusion proteins). Bivalent binding of an antibody to glycoprotein(s) on the cell surface offers higher affinity yet requires more freedom and congruency of carrier-target interaction. Ligands binding to distinct epitopes on the same target molecule may influence each other, for example, inhibiting binding to adjacent epitopes. The competitive inhibition of binding to overlapping epitopes has been described for antibodies to ACE.308−310

Recently, it has been found, however, that distinct monoclonal antibodies directed to adjacent epitopes in the distal domain of the extracellular moiety of PECAM, stimulate binding of each other, both in cell culture and in vivo.311 The endothelial binding of PECAM-directed mAbs is increased by co-administration of a paired mAb directed to adjacent, yet distinct, PECAM epitopes. The “collaborative enhancement” of mAb binding was affirmed in mice, manifested by enhanced pulmonary accumulation of intravenously administered radiolabeled PECAM mAb when co-injected with an unlabeled paired mAb.

This highly unusual empirical finding can be interpreted as an increase in accessibility of an epitope to its ligand due to conformational changes in the target determinant molecule induced by binding of a paired “stimulatory” ligand to its adjacent epitope. In theory, it may find utility in targeting strategies. The premise of this strategy, “collaborative enhancement”, is that the initial binding event can lead to an increased binding event of the secondary targeting agent. With this strategy, a therapeutic effect was realized with increased activity of a scFv targeted to PECAM on endothelial cells.311 This phenomenon offers a new paradigm for optimizing the endothelial-targeted delivery of diagnostic agents and therapeutics. It will be interesting to see if this strategy of enhanced targeting can be applied to NC platforms for drug delivery and imaging of disease.

Challenges and Perplexing Issues

The assessment of carrier fate within the target tissue of live animals is such a challenging endeavor that PK-related issues pale in comparison. No method affords accurate data of binding per cell at a given location in vivo. The best data sets are provided by combining isotope tracing demonstrating uptake in an organ and microscopy imaging cellular distribution. Such a level of rigor is needed to characterize new, targeted DDS. Otherwise, studies may look enigmatic, such as vascular pulmonary targeting by an antibody to surfactant protein SP-A,312 the alveolar component inaccessible for liposomes in blood (which is difficult to comprehend except as an artifact of passive retention in the pulmonary capillaries).

Even at the current limited level of understanding of target biology and processes to intervene, many targeting paradigms are incredibly simplistic. For example, tens of thousands of publications characterize ACE, PECAM and ICAM-1: structure, functions, tissue distribution, and role in a plethora of human maladies. Yet, data on their distribution in the vascular lumen throughout blood vessels and in the endothelial cell plasmalemma are fragmentary, at best. Immunostaining, in situ hybridization, Western-blotting, and PCR do not distinguish surface and intracellular proteins. Isotope-labeled antibodies detect surface target, but offer no insight into the protein organization in oligomers or/and clusters and their distribution in the plasmalemma. Systematic information on normal and pathological distribution of any of the endothelial target molecules in the in the vasculature is still missing. An immunochemistry-based atlas of the vascular distribution of ACE, the target of a widely used inhibitor therapy, is arguably the best attempt so far, but ACE organization in the endothelial plasmalemma in the vessels is still enigmatic.179,182

In vitro experiments and computational studies complement expensive in vivo studies but must be interpreted carefully. In the context of targeting, issues of cell culture include (i) degeneration of the cell phenotype; (ii) conditions irrelevant to in vivo (high dose, incubation without washing, prolonged exposure); and (iii) lack of a proper cell environment (for example, tissue components, flow, blood). In particular, endothelial cells grown in cell culture are known to lose phenotypic features–caveolae, glycocalyx, ACE and other marker proteins, basal level of ICAM-1, etc.(64,313−315) Studies using immobilized molecules seem even less relevant. For example, studies of dual ligand targeting using densely co-immobilized target molecules hardly represent the in vivo situation accurately, especially in the case that one of the targets is scarce in the vasculature. Most likely, this strategy may only be useful for a few determinants as both must coexist in close proximity to each other in order to permit simultaneous anchoring of both ligands.