Abstract

Chile is a developing country with a rapidly expanding economy and concomitant social and cultural changes. It is expected to become a developed country within 10 years. Chile is also characterized as being in an advanced demographic transition. Unique challenges are posed by the intersection of rapid economic development and an aging population, making Chile an intriguing case study for examining the impact of these societal-level trends on the aging experience. This paper highlights essential characteristics of this country for understanding its emerging aging society. It reveals that there is a fundamental lack of adequate and depthful epidemiologic and country-specific research from which to fully understand the aging experience and guide new policies in support of health and well-being.

Keywords: Global aging, Latin America, Noncommunicable disease, Chronic illness

Chile has recently been thrust into the international spotlight following critical events including its 8.8 earthquake in 2010 ranked as the fifth or sixth largest worldwide, the 2010 dramatic mine disaster and rescue of 33 copper miners, the longest period of entrapment for miners worldwide, and President Obama’s March 2011 visit to discuss energy options. Nevertheless, few people in the United States have knowledge of this country, and Chile’s aging landscape is mostly ignored.

Chile is one of the most prosperous nations in Latin America, and it has one of the largest proportions of older adults in that region. The country serves as an important and intriguing case study of the intersection of economic development and an advanced demographic transition. How Chile addresses rapid development and aging and evolves a responsive health care model is of global interest. Our goal here is to provide a broad overview of Chile from which to understand its emerging age-related challenges and research needs. We suggest that Chile presents as an important opportunity to understand aging in the context of rapid development and that for such an understanding to fully emerge, an investment in more country-specific research is necessary.

Overview

The Republic of Chile is located in South America. It shares a border with Peru on the far north; it has Bolivia on its northeast side, Argentina on its east side, and the Pacific Ocean on its south and west side. (Figure 1) Chile is twice the size of Japan. It is unusual in its extreme length (about 2,672 miles) yet narrow width (average less than 112 miles), three major distinct geographical regions (northern, central, and southern regions) with different ecosystems, topography, and vegetation, the majestic Andes which extend the country’s length, and its extraordinary beauty. As Chile traverses such a long stretch, most of the Earth’s climates can be found in Chile.

Figure 1.

Map of the Republic of Chile. Map courtesy of www.theodora.com/maps, used with permission.

Inhabited by an estimated 17 million people (July 2012 estimates), most live in urban areas (88%) with over 5.8 million (about 35%) residing in its capital city, Santiago, located in the country’s central region. The country is mostly homogeneous racially and culturally. The 2002 census indicates that most (85.4%) Chileans are of European descent and White or Mestizo (born of mix between a native Indian and Spanish immigrant), with only 5% Indian representing eight different indigenous groups, the majority of whom (4%) are Mapuche. The latter is composed of various groups sharing a common social, religious, and linguistic history. Spanish is the dominate language, although a few native languages are practiced in remote areas including Aymara, spoken mostly in the North, Mapuche, spoken primarily in the south-central region, and Rapa Nui, spoken primarily on Easter Island (Isla de Pascua). Also, a smattering of German is spoken in south central regions reflecting mid-1800 immigration waves from Germany. The majority of Chileans are Catholic (67%), with 16% Protestant, 13% atheist, 4% other, and less than 1% Jewish (Central Intelligence Agency [CIA] World FactBook, accessed December 1, 2011; Encuesta Nacional Bicentenario, 2009; Pan American Health Organization, accessed November 10, 2011).

Chile is considered a developing country, but more specifically, it has recently been designated as an upper middle income country using the World Bank’s classifications of economies into low (≤$1,005), middle (subdivided into lower [$1,006–$3,975] and upper [$3,976–$12,275]), or high incomes (≥$12,276), which is based on gross national income (GNI) per capita (http://www.worldbank.org/). Chile continues to experience sustained economic growth making its per capita gross domestic product the second highest in Latin America (CIA WorldFactBook, accessed December 1, 2011). Thus, although still technically a developing country, it has rapidly moved from a low to upper middle income level status along the pathway to full development.

Its main industries include copper, lithium, other minerals, wine, fruit and other foods, fish processing, iron and steel, wood and wood products, transport equipment, cement, and textiles. Ecotourism, although still relatively small, is a growth industry.

In 2006, 13.7% of Chileans were considered poor compared with Latin America’s average of 40%–50% (Bitŕan, Escobar, & Gassibe, 2010). Chile enjoys almost universal literacy with 95.7% of the population 15 years or older able to read and write, which reflects the country’s long history of elevating the well-being and basic conditions of its population.

A key historical marker for the purpose of this article and understanding health care and aging related issues is the 1973 bloody military coup, which installed Augusto Pinochet as dictator. Pinochet remained in power until the Republic was returned to democratic rule in 1990.

The military coup has been one of the most impactful political developments effecting every aspect of Chilean society. In addition to the deep psychological and emotional wounds in the national soul that continue to exist, the dictatorship adhered to a neoliberal economic model based on the Chicago School, which significantly reduced the state’s role and prompted a vigorous development of the private area, including health.

Since the end of Pinochet’s rule in 1990, Chile has made steady and impressive economic progress as also discussed earlier. If it remains on its course of economic growth, it is projected to become a “developed” country within 10 years—one of the first in Latin America to obtain this designation.

Using 1990 as baseline, Chile has accomplished many of the World Health Organization (WHO)’s Millennium Development Goals for developing nations. It is on target for accomplishing most if not all goals before the deadline of 2015 (United Nations, 2005b). Table 1 provides key examples of its progress toward each Millennium goal. The accomplishment of the Millennium Development Goals in part reflects the country’s stated national goal following the end of Pinochet’s rule for a “fairer society” and a “budget structure focused primarily on equality and the development of opportunities for the more needy sectors” (Ricardo Lagos Escobar, former President of the Republic of Chile, 2005).

Table 1.

Summary of Millennium Goals and Chile’s Progress

| Goal | Domain | Progress |

| Goal 1 | Reduce extreme poverty | Chile is the only country in Latin American that has already achieved the target of halving extreme poverty. Between 1990 and 2006, Chile reduced poverty from 38.6% to 13.7% and extreme poverty from 12.9 percent to 3.2 per cent. (Nov. 2007, http://www.mdgmonitor.org/factsheets_00.cfm?c=CHL). |

| Goal 2 | Achieve universal primary education | Net primary school enrollment ratio is >90% with a net primary school enrollment ratio of about 95.5% expected in 2015. The ratio was 88% in 1990. Youth literacy rate has always been high with 99.8% of total population 18 to24 expected to be able to read and write by 2015. Additional targets for Chile include reducing proportion of individuals in 15 to 65 age group <8 years schooling to 15% by 2015 (it was 31% in 1990 and 22% in 2000. |

| Goal 3 | Promote gender equality and empower women | literacy rate for men and women is similar for 15 to 24 yr olds (about 99%). Proportion of women in wage employment in non-agricultural sector is expected to climb to 40% by 2015. Representation in parliament is expected to increase (6% in 1990 to 9.5% in 2000 to 40% by 2015). Secondary education completion rate for women is expected to be 91.3% in 2015. Wage gap was 31% in 2000 ($1,000 earned by men = $689 earned by women). Expected to be reduced to 25% by 2015. |

| Goal 4 | Reduce child mortality | Mortality incidence in children aged 1–4 has dropped 50% in the 1990s ending up close to expected rate for 2015. |

| Goal 5 | Improve maternal health | One of the lowest rates in Latin American. 1990 = 4.0 per 10,000 live births dropping to 1.7 per 10,000 live births in 2002. It is expected to drop to 1.0 in 2015. |

| Goal 6 | Combat HIV/etc | Prevalence of HIV/AIDS in pregnant women has remained low and stable (5%). There is no malaria in Chile and mortality from TB has decreased constantly. And is in the process of being eliminated. Other goals have thus been set to reduce mortality from Cardiovascular disease and diabetes, depression prevalence, tobacco consumption, and the “drinking problem” in the 12+ population. |

| Goal 7 | Ensure environmental sustainability | Good access to public sewer systems; seek to reduce average number of forest fires and increase land area reclaimed from desert encroachment; land area covered by forests is increasing due to plantings. Significant progress expected in terms of “slum dwellers” as a proportion of urban population (1990=12.47% of households expected to be 3.65% by 2015). |

| Goal 8 | Develop global partnership | No data available for this. |

Note: Information for this table is from the Millennium Development Goals: Executive Summary (2005) and the United Nations (2005b) The Millennium Development Report.

Impressive economic advancements, however, hide the complex social, cultural, and economic divisions and turmoil occurring in Chile and the growing divide between poor and rich and young and old. For example, Chile has one of the most unequal income distributions in the world (United Nations, 2005a). Although less people live in poverty than ever before, there is a very rich sector that is growing.

Demography of Aging

Chile is in what is referred to as an advanced demographic transition stage. Similar to developed countries, 22.3% of its total population is in the 0–14 age range, 68.1% of the population is in the 15–64 age range, and 9.6% are 65 years or older. The population over 60 years of age represents 13% of the total population (Note: demographers typically consider the aging population in Latin America as 60 and over). Chile experiences dual and possibly competing needs; to provide resources in the form of education, for example, to 68.1% of the population in the 15–64 age range and to address emerging health and social service needs of its growing elderly population. The median age of the country is 32.1 years, similar to the median age of the United States which is 36.9 years (CIA World FactBook, accessed December 1, 2011; Meza, 2003).

Also similar to developed countries, low birth and low mortality rates account for the most part for Chile’s rapid and advanced demographic transition (Meza, 2003). For example, in 1960, the general mortality rate was 12.3 per 1,000, infant mortality rate was 120 per 1,000, and 44% of causes of death were by infectious and newborn’s diseases. By 2001, the general mortality rate was reduced to 5.4 per 1,000, the infant mortality rate was 8.9 per 1,000, and 68% of causes of diseases were from chronic diseases (Meza, 2003).

The current total fertility rate in Chile is 1.88 children (2011 estimates). This is under the population replacement rate of two children per woman and another indicator that Chile’s population is growing older (CIA World Factbook, 2011).

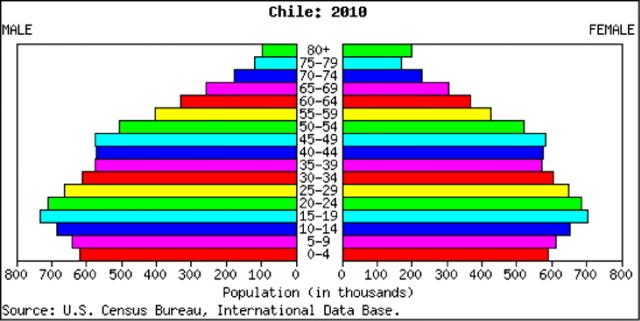

It is anticipated that the aging population will continue to increase to represent 20.8% of the population by 2044. This is comparable to a 2010 figure for Japan in which 22.5% of the population is 65 or older with the expectation that this will increase to 36.4 percent by 2044 (Muramatsu & Akiyama, 2011). Thus, in the near future and similar to other developing and developed countries, Chile will experience “super-aging.” Figure 2 shows Chile’s current age pyramid.

Figure 2.

Age Pyramid of Chile.

Nevertheless, the elderly dependency ratio is relatively low with about 13 persons aged 65 and over per 100 persons 20–64 (note, these are 2002 figures from Marín & Wallace, 2002). Chile currently ranks 57th in the world for life expectancy at 77.7 years comparing favorably to the United States 50th ranking and average of 78.4 years. However, men in Chile have lower life expectancy of 74.4 years, whereas for females, it is 81.12 years (CIA World Factbook, 2011). This life expectancy gap of close to 8 years may adversely affect women socially and economically. For example, more women will be living alone, a new phenomenon in Chile and may experience increasing isolation. Additionally, more women may face reduced economic status in their later years as most did not participate in the labor force and were dependent upon their husband’s salaries and pensions. However, little is known about the impact of the life expectancy and wage gap on women, as they age. Although women’s presence in the workforce is increasing, this is a relatively recent phenomenon and women are still underrepresented. Their workforce participation has pushed other social and cultural modifications such as creation of child day care services in cities and continued and increased reliance on older family members living with or nearby. As Table 1 shows, women’s participation in the nonagricultural labor force is expected to reach 40% by 2015, but the wage gap continues at about 31%.

Life expectancy also varies by geographic location and is up to 10 years less among certain indigenous populations (e.g., Aymara), attesting to regional differences and pockets of underdevelopment and poverty particularly among Indigenous populations and in rural areas. Lack of detailed data hamper a full understanding of the specific impact on aging persons in these remote and rural areas and the age transition and its impact on indigenous populations.

Rapid economic advancement has brought on significant changes in social organization to which the country is unaccustomed. For example, an increasing number of older adults are now living alone versus in an extended family. About 12% of adults 60 years of age or older live alone compared with 9% in 1992; and 60.2% of women who live alone are 60 years or older (Gonzalez & Torres, 2010). Yet, little is known about this group in terms of their health, social engagement, and overall wellbeing.

Brief History of Health System

The health and well-being of older adults in Chile must be understood within the context of health reform which has evolved over time in three waves (Mardones-Restat & de Azevedo, 2006). Chile has a long history of mixed public and private forms of health care provision dating back to the early 1900s. For the purposes of this article, of importance is the emergence in 1952 of the National Health Service (Servicio Nacional de Salud—SNS) similar to the British system of a public system of health care. This represented a critical development that enabled Chile to enhance the health of the public favorably and meet positive health indicators more rapidly than other Latin American countries. Nevertheless, during this time there continued to be an active private sector with many doctors in the public sector also working in private practices. Public sector and white collar employees had a separate insurance system, which in 1968 became a full benefit plan using private physicians (SERMENA—National Medical Services for Employees). Each branch of the armed forces also had its own medical care system (Marín & Wallace, 2002). To fill the gap between private and public systems, there also emerged a voluntary sector supported by religious charities. Thus, Marín and Wallace (2002) indicate that four systems (public, private, military, and voluntary) emerged to address health care needs of a young population. The first major health care reform to these co-occurring systems was imposed by the military regime in the early 1980s, which sought to privatize the health system and reduce public expenditures. This brought on major changes including financing of the public health system and creation of private insurers and inequities. More specifically, this resulted in abandonment of a public health infrastructure, and creation of an unregulated private health financing system and a private health delivery system primarily in urban areas (Araya, Rojas, Fritsch, Frank, & Lewis, 2006; Mardones-Restat & de Azevedo, 2006). Thus, a two-tier system and sharper inequities emerged; FONASA (Fondo Nacional de Salud de Chile), which is the single public insurer covering more than two thirds of the population including the very poor who need full subsidies; and ISAPREs (Las Instituciones de Salud Previsional), which are the private health insurers covering 17% of higher income Chileans (Bitŕan et al., 2010). The second subsequent reform was implemented by the democratic administrations of the early 1990s to reverse some of the harm done by their military predecessors. This included imposing regulations on the private sector by creating a special public agency for oversight. Also there was a shift from privately administered retirement pensions back to the public sector and a doubling of government funding for health care (Marín & Wallace, 2002). In 2005, a third reform was implemented: Chile passed comprehensive health reform (Regimen de Garantias Explicitas en Salud) that mandated coverage by public and private health insurers for selected medical interventions for 69 priority diseases, some of which are chronic conditions. Despite the lack of ongoing evaluative data, some evidence suggests that this reform has resulted in significant increases in access to needed health services both in the public health and private insurance plans as it concerns the 69 identified health problems (Bitŕan et al., 2010). Although many of the targeted chronic conditions are associated with aging, there is relatively little information concerning its specific impact on older Chileans. Also, the rapid aging of the population and the advent of new technologies pose a significant challenge to the insurance system’s coverage capacity and threaten the sustainability of all of Chile’s health systems. Thus, some suggest that universal, comprehensive collective health systems, managed under an integrated authority may be the best solution for Chile and other developing countries (Mardones-Restat & de Azevedo, 2006).

Despite Chile’s long history of public health, there is still not a systematic and comprehensive approach to health and social services for its aging population. Health reforms resulting in private health sector growth have increased risk segmentation and inequalities in service provision (Araya et al., 2006). Common complaints of the public health sector for older adults center around the amount of time to wait to obtain a doctor’s appointment, and shortages in eye and dental care services, and lack of adequate coverage in these areas (Marín & Wallace, 2002). Inequities also persist with regard to mental health services. Individuals with public insurance have higher rates of mental disorders but lower rates of consultation compared with those with private coverage (Araya et al., 2006).

Current Health Indicators

Chile spends 8.2% of its gross domestic product on health care (CIA World Factbook, 2011) which is close to Japan’s relatively low health care costs (7.9%) and in comparison to the United States, which spends double that amount (Muramatsu & Akiyama, 2011).

Chile’s historical investments in sanitation, nutrition, potable water, and basic education dating back to the 1920s have resulted in significant reductions in communicable diseases (WHO, 2006). Thus, important changes in the causes of death have occurred over a relatively short period of time. Based on 2002 WHO data, noncommunicable diseases accounted for 79.4% of total deaths in Chile (Pan American Health Organization, 2011). Chile presently confronts the challenge of rising obesity (about 21% of the population) with prevalence rates significantly higher among people with lower education (Bambs, Cerda, & Escalona, 2011) and chronic illness. The top 10 causes of mortality for example are similar to developed countries reflecting in part cultural and lifestyle changes, which accompany economic advancement. These conditions include (a) coronary heart disease, (b) stroke, (c) influenza and pneumonia, (d) Alzheimer’s disease, (e) diabetes, (f) hypertension, (g) lung disease, (h) stomach cancer, (i) liver disease, and (j) lung cancers (World Life Expectancy, accessed December 1, 2011). As chronic disease is a growing problem, it has become a national priority of the Chilean Ministry of Health (Regimen de Garantias Explicitas en Salud). The governing agency has mandated coverage by the social health insurance system for various health conditions, many of which are chronic (Bitŕan et al., 2010), but only seven are exclusively related to older adults. It also has begun to sponsor various national health promotion programs for cardiovascular health and diabetes in particular, which emphasize nonpharmacologic approaches to disease management.

Furthermore, improved economic and social conditions have led to an increase in consumption of high-caloric foods and concomitantly a sharp increase in sedentarism, resulting in higher rates of overweight and obesity among young and old (Santos et al., 2004). The prevalence of a sedentary lifestyle among Chileans is extremely high, estimated at 89.4% (Bambs, Cerda, & Escalona, 2011).

Not surprisingly, nutrition was historically and remains today a primary emphasis of public health policy, programs, and research (Santos et al., 2004). To promote healthy aging, the government of Chile has been providing a nutritional supplement to older adults since 1998. The Programme of Complementary Feeding for the Older Population (PACAM) distributes micronutrient fortified foods to adults 70 years or over who are registered for the program through their Primary Health Centers. A focus of numerous research studies has been to examine outcomes and cost effectiveness of this program (Dangour et al., 2007).

Yet another health concern and focus of research is air pollution. As urban areas are more populated and have higher concentrations of air pollution, older adults are particularly susceptible to dying from this source (Cakmak, Dales, & Vidal, 2007). Cancer is also a rising critical health concern. In 2006, it ranked as the second leading cause of death in Chile, with males mostly experiencing stomach, lung, and prostate cancers, and females, gallbladder, breast, and stomach cancers. This rise in cancer incidents prompted a partnership in 2009 with the United States National Cancer Institute (NCI) and Chile’s Ministry of Health to accelerate basic and clinical research, and cancer registries across borders (www.cancer.gov/aboutnci/olacpd).

Lifestyle also profoundly affects women’s health. For example, one in every four Chilean woman dies from cardiovascular disease which in turn is due primarily to smoking, diabetes, and hypertension. This combined with higher rates of obesity and sedentarism among women than men has increased risk factors and prevalence of cardiovascular disease among middle-aged Chilean women (Morbid obesity in a developing country: The Chilean experience, accessed December 12, 2011; www.cancer.gov/aboutnci/olacpd). Thus, developing and testing health promotion life style supportive public health interventions are urgently needed (Kim, de la Rosa, Rice & Delva, 2007).

Key Public Policy Issues Concerning Aging

An increased focus on the specific health needs of older adults has only recently occurred. In 2002, a national effort to focus on health issues related to aging was initiated (Servicio Nacional del Adulto Mayor; SENAMA). Key public policy focuses on improving living conditions and health programs specific to the needs of older adults, developing and implementing elder abuse laws, and enhancing access to public spaces so that older adults can participate in tourism or use public transportation at reduced rates. The importance of specialized health care for the elderly such as comprehensive geriatric assessments is becoming an increasing focus of attention, as the prevalence of risk of falls and chronic diseases increases (Tapia et al., 2010). Yet, knowledge about health behaviors of older adults is scarce and how older adults with disability and comorbidities carry out everyday activities of living without adequate home care and other social supportive structures.

Emerging Issues on Aging

Only recently has aging become a topic of public policy and the focus of attention of the Ministry of Health of Chile. Emerging issues include designing and implementing health promotion programs to help older adults adapt healthy behaviors and special immunization programs. This is the dominate focus. Other issues, however, prevail such as dementia care. According to the National Health Survey, prevalence of dementia in Chileans 60 plus years of age is 8.5% (National Health Survey, 2003; Nitrini et al., 2009). Although dementia is the fourth leading cause of death, it is not yet a priority of the Ministry of Health, and thus, it has received insufficient public health attention and clinical and research funding. Researchers and practitioners are seeking a National Dementia Plan, so that a systematic care initiative can be developed and implemented. Emphasis is being placed on an approach that is interprofessional and which integrates pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic strategies.

Finally, another recent and pressing concern is “occupation” in the broadest sense of the term. As job opportunities favor younger adults, age discrimination is normative. Similarly, access to participation in meaningful activities can be challenging for older adults in Chile. In Santiago, the city is divided into provinces with each responsible for organizing events for older adults. Provinces with more resources offer enhanced activities including travel opportunities, free exercise facilities, and opportunities for social engagement. A rising concern, however, is the lack of meaningful opportunities to remain socially and economically integrated as one enters old age in Chile. Not surprisingly, there has been a rise of mental health issues and in particular, depression (Saldivia, Vicente, Kohn, Rioseco, & Torres, 2004).

Other research foci include understanding socioeconomic dynamics and their impact on aging. For example, research has focused on the hypothesis of an inverse relationship between socioeconomic position and all-cause mortality in developing countries. This “pauper-rich paradox” has been documented recently in Chile among 920 healthy participants (30–89 years of age) who were followed for 8 years. This and other studies suggest that whereas education has a protective effect on mortality risk, income has an unfavorable outcome on survival. The pauper-rich concept refers to the situation in which higher income quintiles in Chile correspond with lower income levels in developed countries. One explanation is that Chileans with better income do not necessarily have better education and vice versa. This discrepancy may result in negative consequences including increased stress and poor health. This may be particularly the case among those with high education but low income who may experience limited purchase power and be unable to fulfill lifestyle expectations (Koch et.al, 2010).

More in-depth research on the aging experience in Chile is significantly hampered by the lack of adequate epidemiological data to frame the parameters of need, risk, and daily life. There have been few epidemiological studies in Chile due primarily to the lack of public financing of such studies. Furthermore, basic, clinical, and behavioral studies have not been a funding or policy priority of government health agencies. Population-based surveys that do exist typically include multiple countries and cities. Thus, studies of Chile are mostly restricted to those living in Santiago and are typically part of cross-country comparative research efforts (Atkinson, Cohn, Ducci, & Gideon, 2005). Although such studies are informative, there is limited research on focal concerns most relevant to Chile; also, there is a dearth of research on older adults in regions other than the large urban centers. As regional inequities in access to health care and life expectancies exist, greater attention is needed for a within country research focus.

As Table 2 shows, we were able to identify only two population-based data sets available for investigation (Albala et al., 2005). The next country-wide census is scheduled in 2012, which will provide important information for more fully understanding Chile’s aging transition. In addition, the following are excellent sources for up-to-date foundational information about Chile: the CIA World Factbook provides yearly updates of country specific information concerning demographic and economic indicators, and the WHO and its Pan American Health Organization provides timely country-specific data on health indicators.

Table 2.

Data Sets

| Data Set | Dates | Brief description | Sources of Support | How to Access |

| Survey on Health, Well-being and Aging (SABE) | 1999 and 2000 | Survey on public health and aging in Latin America; A cross-sectional, multicenter study including face-to-face interviews in official languages. Santiago Chile was one of the 7 cities included in the survey. | Pan American Health Organization; National Institute on Aging | http://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/ICPSR/studies/3546 |

| National Quality of Life and health survey | 2000 | Sponsored by the Chilean government | Chilean government | Minsterio de Salud (MINSAL). Encuesta ancional de caldidad de vida y salud. Santiago, Chile, Departamento de Epidemioligia & Departmamento de Promocion de la Salud, 2002 |

Conclusion

Chile is an understudied country experiencing a unique historical juncture of rapid development and aging. Older adults, particularly those with compromised health or resources, may be particularly vulnerable to the social and psychological stressors associated with these dramatic transitions and concomitant cultural shifts. Alternatively, improvements in economic well-being of the country may portend unforeseen benefits and opportunities for older adults such as access to or creation of improved technologies to make life easier.

Although a limitation of this article is reliance mostly on English publications, it is nevertheless clear that little research exists specific to the aging experience in Chile and how its older populations fare within external and fast moving changes. There is much epidemiologic work that needs to be conducted to answer basic questions about aging, the health and wellbeing of older adults, adaptive and coping mechanisms healthy behaviors, and engagement. Currently, few data banks exist and basic demographic and epidemiologic information must be sifted from multiple sources, reflecting different collection dates spanning many years and limited to mostly urban areas. Thus, data are often not current and most studies are limited to residents of Santiago. Although most older adults reside in urban areas, of importance still is an understanding of the aging experience throughout Chile. There remains a relative dearth of information on health and well-being of older adults living in rural and remote areas.

Additionally, Chile’s current mixed private/public health care system is complex and threatens to increase fragmentation of care for older adults. It is unclear how the systems in place will be able to respond to rising chronic illness and what will undoubtedly become greater need and demand for in-home care support. Research concerning Chile’s response to these challenges may inform other countries, developing and developed, of possible pathways for addressing the health challenges posed by an aging society. As Chile continues with rapid economic development and its aging transition, it has the difficult challenge but great potential of creating a new model of health care that may be relevant to other developing countries in Latin American and elsewhere (Marín & Wallace, 2002).

The aging experience is necessarily and obviously grounded in and bounded by historical–sociopolitical and cultural environmental contexts and health systems of care. Chile presents as an intriguing case study of the confluence of rapid development and dramatic demographic transitions for which we urge greater research attention be paid. At the broadest level, research is warranted to understand how the intersection of exponential economic growth and demographic transitions impact the everyday lived experience of individuals who transcend cultural and economic divides of a country moving forward—from an under to developed economic state. In view of limited resources, an immediate research need is for epidemiological cross-sectional profiles and longitudinal trajectories of aging, health, disability, family caregiving, and environmental supports and barriers for purposeful and systematic planning. Additionally, another immediate research priority is for identifying, developing, testing, and implementing health promoting interventions for Chile’s aging population that is rapidly confronting rising obesity, sedentarism, and an array of chronic illnesses that are not adequately being addressed and which erode quality of life.

References

- Albala C, Lebrao ML, Leon Diaz EM, Ham-Chande R, Hennis AJ, Palloni A, et al. The health, well-being, and aging (“SABE”) survey: Methodology applied and profile of the study population. [Encuesta Salud, Bienestar y Envejecimiento (SABE): Metodologia de la encuesta y perfil de la poblacion estudiada] Revista Panamericana De Salud Publica = Pan American Journal of Public Health. 2005;17:307–322. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49892005000500003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araya R, Rojas G, Fritsch R, Frank R, Lewis G. Inequities in mental health care after health care system reform in Chile. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:109–113. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.055715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson S, Cohn A, Ducci ME, Gideon J. Implementation of promotion and prevention activities in decentralized health systems: Comparative case studies from Chile and Brazil. Health Promotion International. 2005;20:167–175. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dah605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bambs C, Cerda J, Escalona A. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2011 doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.048785. Retrieved December 12, 2011, from http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/86/10/07-048785/en/index.html. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitŕan R, Escobar L, Gassibe P. After Chile’s health reform: Increase in coverage and access, decline in hospitalization and death rates. Health Affairs (Project Hope) 2010;29:2161–2170. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cakmak S, Dales RE, Vidal CB. Air pollution and mortality in Chile: Susceptibility among the elderly. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2007;115:524–527. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Central Intelligence Agency World FactBook. Retrieved December 1, 2011, from https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/ci.html. [Google Scholar]

- Dangour AD, Albala C, Aedo C, Elbourne D, Grundy E, Walker D, et al. A factorial-design cluster randomised controlled trial investigating the cost-effectiveness of a nutrition supplement and an exercise programme on pneumonia incidence, walking capacity and body mass index in older people living in Santiago, Chile: The CENEX study protocol. Nutrition Journal. 2007;6:14. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-6-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Encuesta Nacional Bicentenario. Pontificia Universidad Católica-Adimark. Santiago, Chile: Universidad de Católica; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez C, Torres A. Las claves que deben considerarse al vivir solo en la tercera edad. El Mercurio. 2010:A11. [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, De La Rosa M, Rice CP, Delva J. Prevalence of smoking and drinking among older adults in seven urban cities in Latin America and the Caribbean. Substance Use & Misuse. 2007;42:1455–1475. doi: 10.1080/10826080701212501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch E, Romero T, Romero CX, Akel C, Manriquez L, Paredes M, et al. Impact of education, income and chronic disease risk factors on mortality of adults: Does ‘a pauper-rich pardox’ exist in Latin American societies? Public Health. 2010;124(1):39–48. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mardones-Restat F, de Azevedo AC. The essential health reform in Chile; a reflection on the 1952 process. Salud Publica de Mexico. 2006;48:504–511. doi: 10.1590/s0036-36342006000600009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marín P, Wallace S. Health care for the elderly in Chile: A country in transition. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research. 2002;14:271–278. doi: 10.1007/BF03324450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meza SJ. Demographic-epidemiologic transition in Chile, 1960–2011. Rev Esp Salud Publica. 2003;77(5):605–613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millennium Development Goals: Executive Summary. Retrieved December 2, 2011, from http://www.undg.org/docs/7621/resumen%20MDGR%20Chile%20ingles.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Morbid obesity in a developing country: The Chilean experience. Retrieved December 12, 2011, from www.cancer.gov/aboutnci/olacpd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muramatsu N, Akiyama H. Japan: Super-aging society preparing for the future. The Gerontologist. 2011;51:425–432. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnr067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Health Survey. Chile. 2003. Retrieved December 1, 2011, from http://epi.minsal.cl/epi/html/invest/ENS/InformeFinalENS.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Nitrini R, Bottino CM, Albala C, Custodio Capunay NS, Ketzoian C, Llibre Rodriguez JJ, et al. Prevalence of dementia in Latin America: A collaborative study of population-based cohorts. International Psychogeriatrics/IPA. 2009;21(4):622–630. doi: 10.1017/S1041610209009430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan American Health Organization. Non communicable diseases in Americas: Building a healthier future. 2011. Retrieved from http://new.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_docman&task=doc_view&gid=14832&Itemid= [Google Scholar]

- Pan American Health Organization. Retrieved November 10, 2011, from http://www.paho.org/english/dd/ais/cp_152.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Saldivia S, Vicente B, Kohn R, Rioseco P, Torres S. Use of mental health services in Chile. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.) 2004;55(1):71–76. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos JL, Albala C, Lera L, Garcia C, Arroyo P, Perez-Bravo F, et al. Anthropometric measurements in the elderly population of Santiago, Chile. Nutrition (Burbank, Los Angeles County, Calif.) 2004;20(5):452–457. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2004.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapia PC, Varela VH, Barra AL, Ubilla VMD, Iturra MV, Collao AC, et al. Cross sectional geriatric assessment of free living older subjects from Antofagasta, Chile. [Valoracion multidimensional del envejecimiento en la ciudad de Antofagasta] Revista Medica De Chile. 2010;138(4):444–451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. The Report of the World Social Situation 2005: The Inequality Predicament. New York, NY: United Nations Publications; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. The Millennium Development Report. New York, NY: United Nations Publications; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Walker DG, Aedo C, Albala C, Allen E, Dangour AD, Elbourne D, et al. Methods for economic evaluation of a factorial-design cluster randomised controlled trial of a nutrition supplement and an exercise programme among healthy older people living in Santiago, Chile: The CENEX study. BMC Health Services Research. 2009;9:85. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. WHO Global InfoBase Online. Country Profiles. 2006. Retrieved December 1, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- World Life Expectancy. Retrieved December 1, 2011, from http://www.worldlifeexpectancy.com/world-rankings-total-deaths#instructions. [Google Scholar]