Abstract

Background

Cross-sectional studies have associated poor insight in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) with increased OCD symptom severity, earlier age of comorbid depression, and treatment response. The goal of this current study was to examine the relationship between dimensions of OCD symp tomatology and insight in a large clinical cohort of Brazilian patients with OCD. We expect poor insight to be associated with total symptom severity as well as with hoarding symptoms severity.

Methods

824 outpatients underwent a detailed clinical assessment for OCD, including the Yale–Brown Obsessive–Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS), the Dimensional Yale–Brown Obsessive–Compulsive Scale (D-YBOCS), the Brown Assessment of Beliefs Scale (BABS), a socio-demographic questionnaire, and the Stuctured Clinical Interview for axis I DSM-IV disorders (SCID-P). Tobit regression models were used to examine the association between level of insight and clinical variables of interest.

Results

Increased severity of current and worst-ever hoarding symptoms was associated with poor insight in OCD after controlling for current OCD severity, age and gender. Poor insight was also correlated with increased current OCD symptom severity.

Conclusion

Hoarding and overall OCD severity explained were significantly but weakly associated with level of insight in OCD patients. Further studies should examine insight as a moderator and mediator of treatment response in OCD in both behavioral therapy and pharmacological trials. Behavioral techniques aimed at enhancing insight may be potentially beneficial in OCD, especially among patients with hoarding.

Keywords: obsessive-compulsive disorder, insight, hoarding, symptom dimension

Introduction

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is characterized by recurring, intrusive, anxiety-provoking thoughts or images (obsessions) associated with repetitive, physical or mental rituals (compulsions) aimed at relieving the anxiety. Despite being classified as a single disorder., OCD is a clinically heterogeneous condition, both in terms of symptom content (1) and insight into OCD symptoms (2) . Since the diagnostic qualifier “with poor insight” was included in the DSM-IV in 1994, between 5% and 45% of patients with OCD have been found to have poor insight (3-9).

Poor insight has been associated with more severe symptoms (6, 7, 10, 11), earlier age of onset, and longer duration of illness (4, 6, 7). Poor insight has also been found to be associated with comorbid diagnoses such as depression (6, 12, 13) and body dysmorphic disorder (14) and with a family history of schizophrenia (7, 12), OCD, and other anxiety disorders (11). Several studies have shown that patients with poor insight are less responsive to behavioral therapy (10, 13, 15-17) and to pharmacotherapy (6, 7, 12, 18) – although there is not unanimity on this point in the literature, as other studies have found no link between insight and response to CBT(19, 20) or SRI trials (3, 21, 22).

Therefore, it remains unclear whether insight, by itself, is a predictor of poor treatment response, or whether this relationship is due to other covarying clinical factors. As mentioned above, insight is associated with other clinical variables that are also markers of poor treatment response, such as OCD severity, comorbid illnesses (especially depression, personality disorders and other anxiety disorders), genetic polymorphism, and symptom subtype (6, 7, 10, 11, 21, 23-26). In order to better understand the poor-insight subgroup, it is important to clarify the pattern of symptoms and other clinical variables that is typically associated with poor insight. Additionally, few studies so far have analyzed how insight would associate with specific OCD symptom patterns. Previous studies have demonstrated a higher proportion of individuals with poor insight having a higher frequency of hoarding symptoms (4, 6, 25, 27). Another study has found a positive relationship between poor insight and symmetry symptoms (28).

Previous studies generally treated insight as a dichotomous entity (4, 5, 12, 16, 23): (29). Significant recent advances in the measurement are promising. For instance, standardized instruments such as the Brown Assessment of Beliefs Scale (BABS) (30) and the Overvalued Ideas Scale (OIS) (31) have since been developed that allow assessment of insight as a continuous entity. Similarly, tools to quantitatively characterize OCD symptom dimensions have similarly advanced in recent years. The Dimensional Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (DY-BOCS) allows assessment of well-validated symptom dimensions of OCD in a continuous fashion (32). Such continuous measures substantially increase both descriptive subtlety and analytical power.

The goal of the current study was to examine the relationship between OCD symptom dimensions and insight in a large clinical cohort of patients with OCD. We hypothesized that poor insight would be associated with total symptom severity as well as with hoarding symptoms (4, 6, 7, 10, 11, 25, 27).

Method

Subjects

Eight hundred twenty-four adult OCD outpatients were recruited from seven sites located in six different Brazilian cities. Subjects were interviewed between August 2003 and August 2008. Subjects were included if they fulfilled DSM- IV diagnostic criteria for OCD, were between 18 and 65 years old and had a current Y-BOCS total score of greater than sixteen. Subjects were excluded if they were diagnosed with schizophrenia or any other condition that could compromise their understanding of the protocol questions. Informed consents were obtained from all participants. The study was approved by the Ethics Committees from all participating sites (33).

Procedure

A more detailed description of the assessment methodology used for this study can be found elsewhere (33). In brief, all interviews were performed by clinical psychologists or psychiatrists with expertise in OCD. Socio-demographic and clinical data were collected using a questionnaire developed by the researchers. The interviews where typically conducted over 2 to 5 hours. A number of standardized instruments were used in the clinical interview. The Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnosis of Axis I (SCID-I) (34) was administered to confirm the diagnosis of OCD and to assess the presence of comorbid axis I disorders. The Yale–Brown Obsessive–Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) (29) was used to determine global symptom severity. The Dimensional Yale–Brown Obsessive–Compulsive Scale (DY-BOCS) (32) was administered to assess global severity of OCD as well as severity in each of the six OCD symptom dimensions, which include some obsessions and related compulsions (aggressive, sexual/religious, symmetry/ordering/counting, contamination/cleaning, hoarding, and miscellaneous). The Brown Assessment of Beliefs Scale (BABS) (30) was used to rate the level of each subject’s insight into their OCD symptoms.

Data Analysis

Exploratory analysis of the relationship between clinical variables and insight was performed using PASW Statistics 18.0 (35). Patients were divided into 4 subgroups based on BABS insight score: a “perfect” insight group with a score of 0, a “good” insight group with a score of 1 to 11, a “poor” insight group with a score of 12 to 18, and a “delusional” group with a score of 19 to 24. The thresholds for dividing these groups was specified a priori and based on methodology for prior studies (7, 30). We compared these 4 groups of patients on several demographic variables, using ANOVA for continuous variables and the Kruksal-Wallis H test for dichotomous variables. A total of 26 clinical comparisons were performed. Because these analyses were exploratory and intended for hypothesis generation, we set the threshold for statistical significance at p<0.05. All significant findings were then entered into an additional ANOVA model with Y-BOCS total score as a covariate to adjust for potential confounding by overall symptom severity.

Further statistical analyses were performed with STATA 11 (36). Our primary goal was to determine whether dimensional OCD symptom current and worst-ever severity scores on the DY-BOCS were associated with insight after adjusting for overall OCD symptom severity. We used Tobit regression rather than linear regression because BABS score were not normally distributed in our sample: BABS scores were left-censored with a large number of zero values. Backward stepwise Tobit regression was performed, with the total BABS score as dependent variable, forcing in age, gender and total Y-BOCS score as covariates. We entered the five DY-BOCS symptom dimensions scores – aggressive, sexual/religious, symmetry/ordering/counting, contamination/cleaning and hoarding – into seperate models for current and worst-ever symptoms. The ‘miscellaneous’ dimension was not included in these analyses because this category constitute a hodge-podge of OCD symptoms that do not correlate together with other symptoms in factor analysis. At each step we eliminated the least significant predictor until all remaining DY-BOCS symptom dimension were significant at an alpha level of .05. In order, to describe the association between OCD symptom severity and level of insight, we conducted an additional Tobit regression analysis. In this Tobit model BABS score was the dependent variable, Y-BOCS score was the independent variable and age and gender were forced in the model as covariates.

Results

Subjects

Eight hundred twenty-four patients were included in the study (329 men (40%)); the mean age at participation was 35.5 (SD=11.8) years. Six hundred eighty-two (83%) were employed and 506 (61%) were married or were living together with a partner. The mean age at the onset of OCD symptoms was 12.8 years (SD=7.5; range 3–59) and the mean duration of illness prior to study evaluation was 22.8 years (SD=12.4). The mean BABS total score was 7.15 (SD=5.49, range 0-24) and the median BABS score was 6.00.

Clinical Characteristics Based on Level of Insight

Table 1 compares the clinical characteristics of subjects based on their level of insight into their OCD symptoms. Subjects who were classified as ‘poor insight’ (BABS score 12-18) or as ‘delusional’ (BABS score 19-24) had higher rates of unemployment, higher Y-BOCS score, and significantly higher scores on several DY-BOCS (symmetry/ordering/counting, contamination/cleaning, and hoarding), though not on others (aggressive and sexual/religious) in the univariate analysis. After controlling for OCD severity in the multivariate analysis, only the associations of level of insight with DY-BOCS hoarding (F(3, 819)= 2.798, p=.039)score and with unemployment (F(3, 819)= 2.854, p=.036) remained significant. The groups did not differ significantly by gender (F(3, 819)= 0.835, p=.475), age (F(3, 819)= 1.854, p=.136), marital status (F(3, 819)= 0.583, p=.626), age at onset of OCD (F(3, 804)= 0.327, p=.806), duration of illness (F(3, 804)= 1.386, p=.246); DY-BOCS total score (F(3, 819)= 2.388, p=.068), suicidal thoughts (F(3, 786)= 1.511, p=.210) or acts (F(3, 7)= 0.846, p=.469) and pattern of comorbidities.

Table 1.

Clinical and sociodemographic characteristics of OCD patients with different levels of insight

| Perfect Insight | Good Insight | Poor insight | Delusional | F value/χ2 |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Sex, male, n, (%) | 46 44.24% | 216 37.37% | 53 36.02% | 14 43.68% | 2.825 | 0.419 |

| Age, mean ± SD | 33.73 ±10.00 | 35.35 ±11.95 | 37.06 ±12.12 | 35.93 ±13.69 | 1.730 | 0.159 |

| Marrital status, Relationship | 46.00 42.59% | 201.00 37.57% | 61.00 40.13% | 10.00 34.48% | 1.322 | 0.724 |

| Work Status, employed, n, % | 84.00 77.78% | 458.00 85.61% | 33.00 78.29% | 8.00 72.41% | 9.216 | 0.027 |

| Age at onset, years, mean ± SD | 13.30 ±7.73 | 12.70 ±7.36 | 13.11 ±8.06 | 12.10 ±6.73 | 0.797 | 0.850 |

| Length of illness, years, mean ± SD | 20.60 ±10.46 | 22.77 ±12.78 | 24.33 ±12.78 | 23.83 ±15.63 | 4.459 | 0.216 |

| Y-BOCS total score, mean ± SD | 25.45 ±5.55 | 27.07 ±5.79 | 28.68 ±5.47 | 30.41 ±5.74 | 9.905 | 0.000 |

| DY-BOCS Hoarding, mean ± SD | 2.34 ±3.61 | 3.44 ±4.12 | 3.99 ±4.38 | 5.38 ±5.25 | 5.492 | 0.001 |

| DY-BOCS Contamination, mean ± SD | 5.96 ±5.21 | 6.52 ±5.16 | 7.81 ±5.14 | 7.31 ±4.83 | 3.447 | 0.016 |

| DY-BOCS Symmetry, mean ± SD | 7.37 ±4.74 | 7.79 ±4.48 | 8.88 ±4.19 | 8.41 ±4.17 | 3.130 | 0.025 |

| DY-BOCS Sexual/Religious, mean ± SD | 4.27 ±5.09 | 4.65 ±4.98 | 4.92 ±5.11 | 6.62 ±5.00 | 1.792 | 0.147 |

| DY-BOCS Aggressive, mean ± SD | 5.18 ±5.01 | 6.00 ±5.11 | 6.30 ±4.81 | 5.03 ±4.73 | 1.431 | 0.232 |

| DY-BOCS Miscellaneous, mean ± SD | 6.82 ±4.88 | 8.21 ±4.47 | 8.70 ±4.34 | 9.14 ±4.57 | 4.385 | 0.005 |

| DY-BOCS total, mean ± SD | 21.98 ±4.93 | 22.40 ±4.95 | 22.72 ±5.28 | 23.28 ±4.66 | 0.740 | 0.528 |

| Hypochondriasis, n, % | 2.00 1.85% | 19.00 3.55% | 8.00 5.26% | 0.00 0.00% | 3.301 | 0.347 |

| Body Dysmorphic Disorder, n, % | 14.00 12.96% | 55.00 10.28% | 27.00 17.76% | 3.00 10.34% | 6.434 | 0.092 |

| Depression, n, % | 38.00 35.19% | 194.00 36.26% | 60.00 39.47% | 15.00 51.72% | 3.337 | 0.343 |

| Agoraphobia, n, % | 6.00 5.56% | 28.00 5.23% | 4.00 2.63% | 1.00 3.45% | 2.052 | 0.562 |

| Agoraphobia with Panic, n, % | 5.00 4.63% | 25.00 4.67% | 4.00 2.63% | 2.00 6.90% | 1.675 | 0.642 |

| Panic, n, % | 6.00 5.56% | 41.00 7.66% | 13.00 8.55% | 1.00 3.45% | 1.544 | 0.672 |

| Lifetime Suicidal Thoughts, n, % | 44.00 42.72% | 174.00 33.79% | 58.00 40.00% | 12.00 42.86% | 4.605 | 0.203 |

| Lifetime Suicide Attempts, n, % | 13.00 12.62% | 55.00 10.68% | 16.00 11.03% | 1.00 3.57% | 1.893 | 0.595 |

Bolded factors remained significant after covarying for overall symptom severity, as measured by the Y-BOCS total score.

Y-BOCS=Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale; DY-BOCS= Dimensional Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale

Relationship Between OCD Symptom Severity and Insight

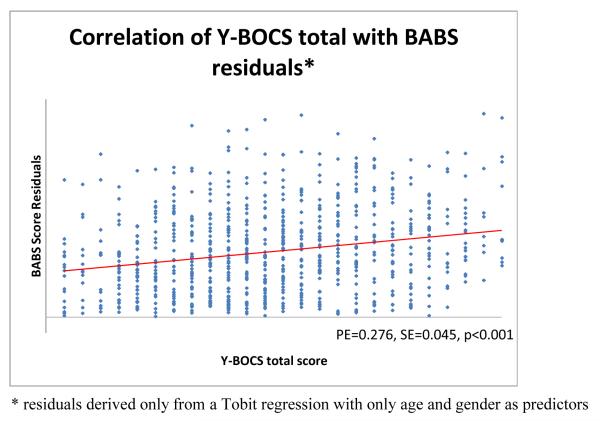

We found a strong association between level of insight and current level of OCD symptom severity when we adjusted for age and gender (Parameter estimate (PE)=.276, SE=.045, p<.001). Figure 1 demonstrates the strong association we found between current OCD symptom severity (total YBOCS score) and level of insight.

Figure 1. Association Between Level of Insight and OCD Symptom Severity.

Scatterplots of BABS score residuals and Y-BOCS score. BABS residuals were adjusted for age and gender in the analysis.

Relationship Between Current Severity in OCD Symptom Dimensions and Insight

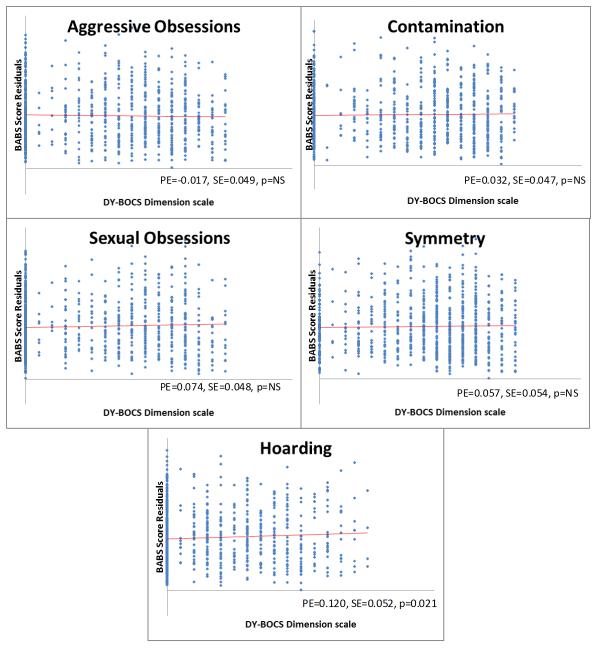

In Tobit regression analysis, after controlling for age, Y-BOCS total score and gender, only symptom severity in the hoarding dimension was associated with level of insight. Increased hoarding symptoms were associated with poor insight (PE=.120, SE=.052, p=.021). This association is depicted in Figure 2, which shows scatterplots of the 5 DY-BOCS symptom dimensions versus BABS score residuals (adjusting for Y-BOCS score, age and gender). No other DY-BOCS symptom dimension scores were significantly correlated with level of insight, after controlling for overall OCD severity.

Figure 2. Assoziation Between the Level of Insight and Current Severity in OCD Symptom Dimensions.

Scatterplots of BABS score residuals and DY-BOCS dimensions. BABS Residual were adjusted for Y-BOCS score, age and gender in the analysis.

Relationship Between Worst-Ever Severity in OCD Symptom Dimensions and Insight

A Tobit regression analysis similar to the one mentioned above was carried out using worst-ever instead of current symptom severity. Only symptom severity in the hoarding dimension was associated with level of insight after controlling for age, Y-BOCS total score and gender,. Increased hoarding symptoms were associated with poor insight (PE=.117, SE=.046, p=.011). No other DY-BOCS symptom dimension scores were significantly correlated with level of insight, after controlling for overall OCD severity.

Discussion

Previous studies have characterized 5% to 45% of patients with OCD as having poor insight (3-9). We found a similar result: 22% of adult OCD patients in this cohort from Brazil were classified as having poor insight, using a threshold score of 12 on the BABS. We found that OCD insight was significantly associated with the severity of current and worst-ever hoarding symptoms, after controlling for overall OCD severity, age, and gender. Poor insight was also associated with increased scores in other symptom dimensions (contamination/washing, and symmetry/ordering/counting); but all of these associations lost significance when overall symptom severity was adjusted for in the analysis. These results extend a previous study in pediatric OCD that associated hoarding symptoms with poor insight (27).

Our findings support the idea that compulsive hoarding might represent a distinct clinical entity from the other types of OCD. Experts have suggested that the hoarding OC symptom dimension should be used as a specifier in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition(37). Indeed, a strong case can be made that compulsive hoarding in the absence of other OCD symptoms should be listed as an entirely separate diagnostic entity (26, 37, 38). Recently, genetic (24), functional neuroimaging (39, 40) and anatomical imaging studies have added support to this hypothesis (41). Hoarding symptoms also have been associated with poor treatment responses. Short-term trials demonstrate poorer responses in OCD patients with primary hoarding symptoms when treated with either cognitive-behavioral therapy or pharmacotherapy (17, 26, 42-46). Additionally, longitudinal outcome studies have associated hoarding symptoms with poor adult outcome in pediatric-onset OCD (47).

Despite the statistical significance of the association between hoarding symptoms and insight, hoarding had only relatively little influence on insight among these patients which was indicated by a low parameter estimate of .120 . The parameter estimate in a Tobit regression model can be interpreted similarly to the regression coefficient in a linear regression. In other words, if the DY-BOCS hoarding score of a patient was to increase by 10 points, the BABS total score would only increase by 1.2 points. No other measured clinical variables (comorbid illness, age of onset, duration of illness etc.) were significantly associated with worse insight, once overall Y-BOCS severity was adjusted for in the analysis. Poor insight was also associated with an increased rate of unemployment among OCD patients. Therefore, unemployment may be an indirect indicator of the negative impact of OCD on occupational activities, particularly when the level of insight is not good. Previous research has suggested that poor insight is associated with poor treatment outcome in both behavior therapy (10, 13, 15, 16) and to pharmacotherapy (6, 7, 12, 18). Our results suggest that these findings are unlikely to be due to confounding of insight with other clinical variables correlated with outcome, because in our data set insight appears only marginally correlated with variables other than illness severity. This suggests that insight represents a distinct characteristic entity associated with worse illness severity that could serve as moderator and/or mediator of treatment effects in OCD, especially behavioral therapy.

Our study represents an advance over many previous studies examining insight in OCD in that both insight and dimension symptoms in OCD were examined using well-validated continuous rating scales. In many previous studies, both insight and symptom types have been treated as categorical entities (i.e. subjects either had good insight or poor insight and either had or didn’t have cleaning obsessions and compulsions). Current thinking about both insight and OCD symptom dimensions suggests that these are not all-or-none phenomenon, and so continuous measures such as those used here may better capture the underlying structure of the condition than artificially discrete categories. Strength of our study is a large sample size, which gives us greater power to detect small associations with OCD.

It is important to note that clinical assessments were made only once for each patient; all analyses are therefore based correlational. It is not clear if persistently increased symptom severity can contribute to a worsening of insight, or if impaired insight might be characteristic of chronic, deteriorating OCD. It remains possible that both insight and symptom severity are influenced by other factors, although such factor were not found in the current analysis.

In sum, we found that poor insight in OCD was correlated with increased OCD severity and increased hoarding symptomatology. No other clinical variables were correlated with level of insight in OCD, after controlling for OCD symptom severity. Traditional clinical variables such as OCD severity, symptom dimension scores and comorbidities were at times weakly but significantly associated with insight in OCD. Further studies should examine insight as a moderator and mediator of treatment response in OCD in both behavioral therapy and pharmacological trials. Behavioral techniques aimed at enhancing insight and/or motivation may be potentially beneficial in OCD. A recent study demonstrated that cognitive behavioral group therapy was more effective if preceded by two individual sessions of motivational interviewing and thought mapping. The symptom reduction was still maintained at a 3-months follow up (48).

Acknowledgements

Thanks for the C-TOC leaders (Aristides Cordioli, Katia Petribu, Christina Gonzales) and to all the mental health professionals that conducted the patients’ clinical assessments.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose

References

- 1.Bloch MH, Landeros-Weisenberger A, Rosario MC, Pittenger C, Leckman JF. Meta-analysis of the symptom structure of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(12):1532–42. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08020320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fontenelle JM, Santana Lda S, Lessa Lda R, Victoria MS, Mendlowicz MV, Fontenelle LF. [The concept of insight in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder] Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2010;32(1):77–82. doi: 10.1590/s1516-44462010000100015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eisen JL, Rasmussen SA, Phillips KA, Price LH, Davidson J, Lydiard RB, et al. Insight and treatment outcome in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 2001;42(6):494–7. doi: 10.1053/comp.2001.27898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matsunaga H, Kiriike N, Matsui T, Oya K, Iwasaki Y, Koshimune K, et al. Obsessive-compulsive disorder with poor insight. Compr Psychiatry. 2002;43(2):150–7. doi: 10.1053/comp.2002.30798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marazziti D, Dell’Osso L, Di Nasso E, Pfanner C, Presta S, Mungai F, et al. Insight in obsessive-compulsive disorder: a study of an Italian sample. Eur Psychiatry. 2002;17(7):407–10. doi: 10.1016/s0924-9338(02)00697-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kishore VR, Samar R, Janardhan Reddy * YC, Chandrasekhar CR, Thennarasu K. Clinical characteristics and treatment response in poor and good insight obsessive–compulsive disorder. European Psychiatry. 2004;19:202–8. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Catapano F, Perris F, Fabrazzo M, Cioffi V, Giacco D, De Santis V, et al. Obsessive-compulsive disorder with poor insight: a three-year prospective study. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2010;34(2):323–30. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2009.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foa EB, Kozak MJ, Goodman WK, Hollander E, Jenike MA, Rasmussen SA. DSM-IV field trial: obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152(1):90–6. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Storch EA, Milsom VA, Merlo LJ, Larson M, Geffken GR, Jacob ML, et al. Insight in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder: associations with clinical presentation. Psychiatry Res. 2008;160(2):212–20. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Solyom L, DiNicola VF, Phil M, Sookman D, Luchins D. Is there an obsessive psychosis? Aetiological and prognostic factors of an atypical form of obsessive-compulsive neurosis. Can J Psychiatry. 1985;30(5):372–80. doi: 10.1177/070674378503000515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bellino S, Patria L, Ziero S, Bogetto F. Clinical picture of obsessive-compulsive disorder with poor insight: a regression model. Psychiatry Res. 2005;136(2-3):223–31. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2004.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Catapano F, Sperandeo R, Perris F, Lanzaro M, Maj M. Insight and resistance in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychopathology. 2001;34(2):62–8. doi: 10.1159/000049282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Foa EB. Failure in treating obsessive-compulsives. Behav Res Ther. 1979;17(3):169–76. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(79)90031-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eisen JL, Phillips KA, Coles ME, Rasmussen SA. Insight in obsessive compulsive disorder and body dysmorphic disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 2004;45(1):10–5. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2003.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foa EB, Abramowitz JS, Franklin ME, Kozak MJ. Feared consequences, fixity of belief, and treatment outcome in patients with obsessive–compulsive disorder. Behav Ther. 1999;30:717–24. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Himle JA, Van Etten ML, Janeck AS, Fischer DJ. Insight as a predictor of treatment outcome in behavioral group treatment for obsessive–compulsive disorder. Cogn Ther Res. 2006;30:661–6. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mataix-Cols D, Marks IM, Greist JH, Kobak KA, Baer L. Obsessive-compulsive symptom dimensions as predictors of compliance with and response to behaviour therapy: results from a controlled trial. Psychother Psychosom. 2002;71(5):255–62. doi: 10.1159/000064812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Erzegovesi S, Cavallini MC, Cavedini P, Diaferia G, Locatelli M, Bellodi L. Clinical predictors of drug response in obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001;21(5):488–92. doi: 10.1097/00004714-200110000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lelliott PT, Noshirvani HF, Basoglu M, Marks IM, Monteiro WO. Obsessive-compulsive beliefs and treatment outcome. Psychol Med. 1988;18(3):697–702. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700008382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ito LM, de Araujo LA, Hemsley D, Marks IM. Belief and resistance in obsessive–compulsive disorder: observation from a controlled study. J Anxiety Disord. 1995;167:71–5. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alonso P, Menchon JM, Segalas C, Jaurrieta N, Jimenez-Murcia S, Cardoner N, et al. Clinical implications of insight assessment in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 2008;49(3):305–12. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferrao YA, Shavitt RG, Bedin NR, de Mathis ME, Carlos Lopes A, Fontenelle LF, et al. Clinical features associated to refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Affect Disord. 2006;94(1-3):199–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Turksoy N, Tukel R, Ozdemir O, Karali A. Comparison of clinical characteristics in good and poor insight obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Anxiety Disord. 2002;16(4):413–23. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(02)00135-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Samuels J, Shugart YY, Grados MA, Willour VL, Bienvenu OJ, Greenberg BD, et al. Significant linkage to compulsive hoarding on chromosome 14 in families with obsessive-compulsive disorder: results from the OCD Collaborative Genetics Study. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(3):493–9. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.3.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Samuels JF, Bienvenu OJ, 3rd, Pinto A, Fyer AJ, McCracken JT, Rauch SL, et al. Hoarding in obsessive-compulsive disorder: results from the OCD Collaborative Genetics Study. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45(4):673–86. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saxena S. Is compulsive hoarding a genetically and neurobiologically discrete syndrome? Implications for diagnostic classification. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(3):380–4. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.3.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Storch EA, Lack CW, Merlo LJ, Geffken GR, Jacob ML, Murphy TK, et al. Clinical features of children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder and hoarding symptoms. Compr Psychiatry. 2007;48(4):313–8. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Elvish J, Simpson J, Ball LJ. Which clinical and demographic factors predict poor insight in individuals with obsessions and/or compulsions? J Anxiety Disord. 2010;24(2):231–7. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, Mazure C, Fleischmann RL, Hill CL, et al. The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. I. Development, use, and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46(11):1006–11. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810110048007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eisen JL, Phillips KA, Baer L, Beer DA, Atala KD, Rasmussen SA. The Brown Assessment of Beliefs Scale: reliability and validity. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(1):102–8. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.1.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neziroglu F, McKay D, Yaryura-Tobias JA, Stevens KP, Todaro J. The Overvalued Ideas Scale: development, reliability and validity in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Behav Res Ther. 1999;37(9):881–902. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(98)00191-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosario-Campos MC, Miguel EC, Quatrano S, Chacon P, Ferrao Y, Findley D, et al. The Dimensional Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (DY-BOCS): an instrument for assessing obsessive-compulsive symptom dimensions. Mol Psychiatry. 2006;11(5):495–504. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miguel EC, Ferrao YA, Rosario MC, Mathis MA, Torres AR, Fontenelle LF, et al. The Brazilian Research Consortium on Obsessive-Compulsive Spectrum Disorders: recruitment, assessment instruments, methods for the development of multicenter collaborative studies and preliminary results. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2008;30(3):185–96. doi: 10.1590/s1516-44462008000300003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JB. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis I disorders: clinical version (SCID-CV) American Psychiatric Press; Washington, DC: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Inc. S. PASW Statistics 18.0. SPSS Inc.; Chicago IL: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 36.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 11. StataCorp LP; College Station, TX: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leckman JF, Bloch MH. A developmental and evolutionary perspective on obsessive-compulsive disorder: whence and whither compulsive hoarding? Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(10):1229–33. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08060891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pertusa A, Frost RO, Fullana MA, Samuels J, Steketee G, Tolin D, et al. Refining the diagnostic boundaries of compulsive hoarding: a critical review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30(4):371–86. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saxena S, Brody AL, Maidment KM, Smith EC, Zohrabi N, Katz E, et al. Cerebral glucose metabolism in obsessive-compulsive hoarding. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(6):1038–48. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.6.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mataix-Cols D, Wooderson S, Lawrence N, Brammer MJ, Speckens A, Phillips ML. Distinct neural correlates of washing, checking, and hoarding symptom dimensions in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(6):564–76. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.6.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gilbert AR, Mataix-Cols D, Almeida JR, Lawrence N, Nutche J, Diwadkar V, et al. Brain structure and symptom dimension relationships in obsessive-compulsive disorder: a voxel-based morphometry study. J Affect Disord. 2008;109(1-2):117–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.12.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mataix-Cols D, Rauch SL, Manzo PA, Jenike MA, Baer L. Use of factor-analyzed symptom dimensions to predict outcome with serotonin reuptake inhibitors and placebo in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(9):1409–16. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.9.1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abramowitz JS. Effectiveness of psychological and pharmacological treatments for obsessive-compulsive disorder: a quantitative review. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997;65(1):44–52. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stein DJ, Andersen EW, Overo KF. Response of symptom dimensions in obsessive-compulsive disorder to treatment with citalopram or placebo. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2007;29(4):303–7. doi: 10.1590/s1516-44462007000400003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rufer M, Fricke S, Moritz S, Kloss M, Hand I. Symptom dimensions in obsessive-compulsive disorder: prediction of cognitive-behavior therapy outcome. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;113(5):440–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saxena S, Brody AL, Schwartz JM, Baxter LR. Neuroimaging and frontal-subcortical circuitry in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 1998;(35):26–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bloch MH, Craiglow BG, Landeros-Weisenberger A, Dombrowski PA, Panza KE, Peterson BS, et al. Predictors of early adult outcomes in pediatric-onset obsessive-compulsive disorder. Pediatrics. 2009;124(4):1085–93. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Meyer E, Shavitt RG, Leukefeld C, Heldt E, Souza FP, Knapp P, et al. Adding motivational interviewing and thought mapping to cognitive-behavioral group therapy: results from a randomized clinical trial. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2010;32(1):20–9. doi: 10.1590/s1516-44462010000100006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]