SUMMARY

The fermentation of glucose in the presence of enough oxygen to support respiration, known as aerobic glycolysis, is believed to maximize growth rate. We measured increasing aerobic glycolysis during exponential growth at a constant rate, suggesting additional physiological roles for aerobic glycolysis. We investigated such roles in yeast batch cultures by quantifying metabolic fluxes, O2 consumption, CO2 production, amino-acids, mRNAs, proteins, post-translational modifications, and stress-sensitivity in the course of 9 doublings at a constant rate. During this course, the cells supported constant biomass-production rate with decreasing rates of respiration and ATP production but also decreased their heat- and oxidative-stress resistance. As the respiration rate decrease, so do the levels of enzymes catalyzing rate-determining reactions of the tricarboxylic-acid cycle (providing NADH for respiration) and of the mitochondrial folate-mediated NADPH production (required for oxidative defense). These findings suggest that aerobic glycolysis can reduce the energy demands associated with respiratory metabolism and stress survival.

INTRODUCTION

Understanding cell growth is essential to both basic science and treating diseases associated with deregulated cell growth, such as cancer. Accordingly, cell growth has been studied extensively, from the pioneering work of Krebs and Eggleston (1940); Monod (1949) to recent discoveries (DeBerardinis et al., 2007; Slavov et al., 2011; Scott et al., 2010; Youk and Van Oudenaarden, 2009; Clasquin et al., 2011; Chang et al., 2013). Although the major biochemical networks were identified by the 1950s (Krebs and Eggleston, 1940; Monod, 1949), understanding the coordination between these pathways in time remains a major challenge and opportunity to systems biology (Hartwell et al., 1999; McKnight, 2010; Slavov and Botstein, 2011). The challenge stems from the fact that both cell growth and metabolism may take alternative parallel paths. For example, cells can produce energy either by fermenting glucose to lactate/ethanol to generate 2 ATP molecules per glucose molecule or by respiration (oxidative phosphorylation) to generate substantially more (between 16 and 36 depending on the estimate) ATP molecules per glucose molecule. The estimates for the in vivo efficiency of oxidative phosphorylation vary widely depending on the measurement method and the underlying assumptions. These estimates come from: (i) measuring ATP production during fermentative growth and assuming it equals the ATP production and demand during respiratory growth (Von Meyenburg, 1969; Verduyn et al., 1991; Famili et al., 2003), (ii) in vivo 31P NMR flux measurements (Campbell et al., 1985; Gyulai et al., 1985; Portman, 1994; Sheldon et al., 1996), and (iii) in vitro measurements with isolated mitochondria (Rich, 2003; Famili et al., 2003).

Although respiration has higher ATP yield per glucose, cancer/yeast cells tend to ferment most glucose into lactate/ethanol even in the presence of sufficient oxygen to support respiration, a phenomenon known as aerobic glycolysis. This apparently counter–intuitive metabolic strategy of using the less efficient pathway is conserved from yeast to human and has been recognized as a hall mark of cancer (Heiden et al., 2009; Hanahan and Weinberg, 2011). Numerous competing models have been proposed to explain aerobic glycolysis both in yeast and in human (Warburg, 1956; Newsholme et al., 1985; De Deken, 1966; Pfeiffer et al., 2001; Gatenby and Gillies, 2004; Molenaar et al., 2009; Heiden et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2010; Shlomi et al., 2011; Lunt and Vander Heiden, 2011; Ward and Thompson, 2012). While the models propose different and often conflicting mechanisms, they aim to explain aerobic glycolysis as a metabolic strategy for maximizing the cellular growth rate. However, in some cases slowly growing or even even quiescent cells exhibit aerobic glycolysis (Boer et al., 2008; Lemons et al., 2010; Slavov and Botstein, 2013). Theoretical models of aerobic glycolysis are limited by the many incompletely characterized trade-offs of respiration and fermentation, such as the effects of aerobic glycolysis on signaling mechanisms (Chang et al., 2013). Further limitations stem from missing estimates for key metabolic fluxes. For example, depending on whether the increase in the flux of fermented glucose compensates for the low efficiency of fermentation, aerobic glycolysis may either increase or decrease the rate of energy (ATP) production. To better understand the role of aerobic glycolysis for cell growth, we sought to measure directly and precisely the fluxes of O2 consumption and CO2 production, and gene regulation (including levels of mRNAs, proteins, and post-translational modifications) in the conditions of aerobic glycolysis and exponential growth.

RESULTS

Rates of O2 consumption and CO2 production have been measured (Von Meyenburg, 1969; Verduyn et al., 1991; Hoek et al., 1998; van Hoek P et al., 2000; Jouhten et al., 2008; Wiebe et al., 2008) in high–density yeast cultures growing in chemostats at steady-state. The most commonly used laboratory growth condition, low–density cultures growing in batch, however, is a challenging condition for measuring O2 consumption and CO2 production because the small number of rapidly growing cells results in small and rapidly changing fluxes. To overcome this challenge and quantify the relative importance of respiration and fermentation during batch cell growth, we developed a bioreactor in which we can accurately measure the absolute rates of O2 uptake (ΨO2) and CO2 synthesis (ΨCO2). In this setup (Figure 1A), a constant flow of air at rate Jin containing 20.9% O2 and 0.04% CO2 is fed into the bioreactor. By accurately measuring, every second, the O2 and CO2 concentrations in the gas leaving the reactor and applying mass conservation (eqn. 1–2), we can estimate ΨO2 and ΨCO2:

| (1) |

| (2) |

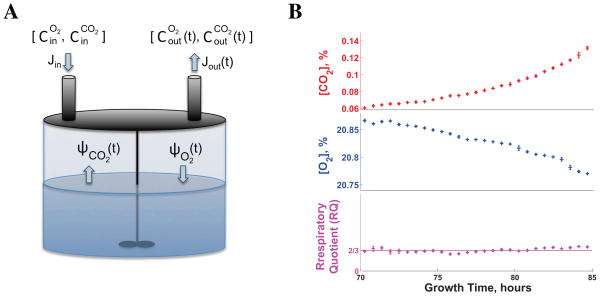

Figure 1. Experimental Design for Precision Measurements of O2 Uptake and CO2 Production in Time.

(A) A conceptual schematic of the method used for precision measurements of O2 and CO2 fluxes in low–density yeast cultures; Cin are the concentrations of gases in the air entering the reactor at rate Jin, and the Cout are the concentrations of gases existing the reactor at rate Jout.

(B) The respiratory quotient (RQ) estimated from O2 and CO2 concentrations measured in a low–density yeast culture growing on ethanol as a sole source of carbon and energy equals the RQ estimate from mass-conservation (2/3); the culture was inoculated at a density of 1000 cells/ml and measurements began 70 hours after inoculation, when the cultured had reached a density of about 105 cells/ml. Error bars denote standard deviations. See Figure S1 and the Supplemental Information for more control experiments and details.

See also Figure S1.

The fluxes are normalized to moles per hour by the molar volume Vm of air at 25 °C and 1 atmosphere. The out–flow rate (Jout) is determined from mass balance analysis and is typically very similar to Jin; see Supplemental Information.

To evaluate the accuracy of the O2 and CO2 fluxes, we measured these fluxes in control growth conditions for which the molar ratio of CO2 to O2, known as respiratory quotient (RQ), is known. First, we grew cells in media containing 100 mM ethanol as a sole source of carbon and energy. The complete oxidation of an ethanol molecule requires 3 O2 molecules and produces 2 CO2 molecules; thus, chemical stoichiometry and mass-conservation require that the RQ for ethanol oxidation equals 2/3, providing a strong benchmark for evaluating the accuracy of our measurements. The measured RQ (Figure 1B) matches the expected value of 2/3. Importantly, the sensitivity of our sensors to very small changes both in O2 consumption (0.005%) and CO2 production (0.002%) allows measuring fluxes from low density yeast cultures (105 cells/ml); see Supplemental Information and Figure S1 for details and more control experiments.

Growth Rate and Doubling Time Remain Constant for 9 Doublings

Having established a system for accurate quantification of O2 and CO2 fluxes, we applied it to a batch culture of budding yeast; two liters of well-aerated and well-stirred minimal medium containing 11.11 mM glucose as a sole source of carbon and energy were inoculated to a cell density of 1000 cells/ml; see Supplemental Information. After 10 hours (h), the culture reached a cell density allowing bulk measurements and was continuously sampled (Figure 2A; Figure S2). During the first 15 h of sampling (9 doubling periods, the pink region in Figure S2), the cell density increased exponentially with time, indicating a constant rate of cell division (μ = 0.4 h−1, 1.7 h doubling time), followed by sudden and complete cessation of growth and division upon glucose exhaustion. Then the cells resumed growth (purple region in Figure S2) supported by the ethanol accumulated during the first growth phase. Notably, during the second growth phase, biomass increased exponentially, indicating again a constant but much slower growth rate μ = 0.04 h−1. Thus, our experimental design provides two phases of exponential growth, characterized by different carbon sources and growth rates. The transition between the two phases has been studied extensively (Brauer et al., 2005; Zampar et al., 2013) and we will not address it; rather, we focus only on the phases with constant doubling times.

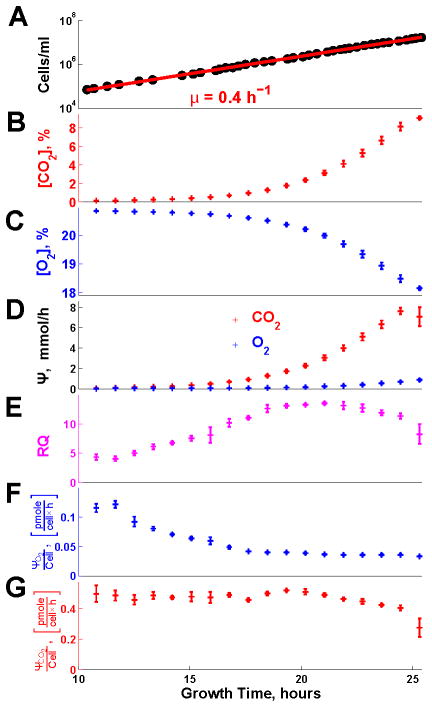

Figure 2. Rates of Respiration and Fermentation Evolve Continuously During Batch Growth at a Constant Growth Rate.

(A) Cell density (single cells per ml) during exponential growth on glucose as a sole source of carbon and energy.

(B) The levels of O2 in the exhaust gas were measured continuously (every second) with a ZrO2 electrochemical cell.

(C) The levels of CO2 in the exhaust gas were measured continuously (every second) with infra red spectroscopy.

(D) Fluxes of O2 uptake ΨO2 and CO2 production ΨCO2 estimated from the data in (A) and (B) and eqn. 1–2; see Supplemental Information for details.

(E) Respiratory quotient (RQ), defined as the ratio of ΨCO2 to ΨO2.

(F) Rate of O2 uptake per cell.

(G) Rate of CO2 production per cell.

In all panels, error bars denote standard deviations. See also Figure S2.

Oxygen Uptake Decreases during Growth at Constant Rate

The continuously measured concentrations of O2 and CO2 (Figure 2B–C) and the fluxes estimated from them (Figure 2D) allow computing the RQ during the first phases of exponential growth (Figure 2E). Since the complete oxidation of a glucose molecule requires 6 O2 and produces 6 CO2, RQ > 1 indicates that some glucose is also fermented in the presence of high level of O2 (Figure 2B), i.e., aerobic glycolysis. Such aerobic glycolysis (RQ > 1; Figure 2E) and the exponential growth in Figure 2A are consistent with previous observations (Brauer et al., 2005; Zampar et al., 2013) and expectations. In stark contrast, the continuously changing metabolic fluxes per cell (Figure 2E–F) during exponential growth suggest that the cells may not be at steady-state even when their growth rate remains constant; this observation is so unexpected that we sought to test it further by multiple independent experimental measurements described below. A second surprising observation is the direction of change: as cells grow and deplete glucose, the oxygen consumption per cell decrease (Figure 2F). This decreasing respiration likely contributes to the cessation of growth after the first growth phase (Figure S2) as cells with down–regulated respiration are challenged to grow on ethanol, an obligatory respiratory condition. During the last doublings on glucose, RQ remains high, albeit beginning to decline in concert with CO2 (Figure 2E,G), indicating that the metabolism remains mostly fermentative as long as glucose is present in the medium.

We sought to further test, by independent measurements and mass-conservation, the dynamically evolving rates of respiration and fermentation (Figure 2E–F) quantified during exponential growth. During the entire first growth phase (Figure 3A), we evaluated whether the flux of carbon intake from glucose equals the sum of all major output carbon fluxes (those due to respiration, biomass synthesis, and fermentation), as required by mass-conservation. The results of this mass-balance analysis (Figure 3B) demonstrate that the carbon fluxes estimated from the biomass and the gas measurements account completely and accurately for the fluxes estimated from glucose up-take, thus confirming the accuracy of all measurements and the metabolic dynamics at a constant doubling time.

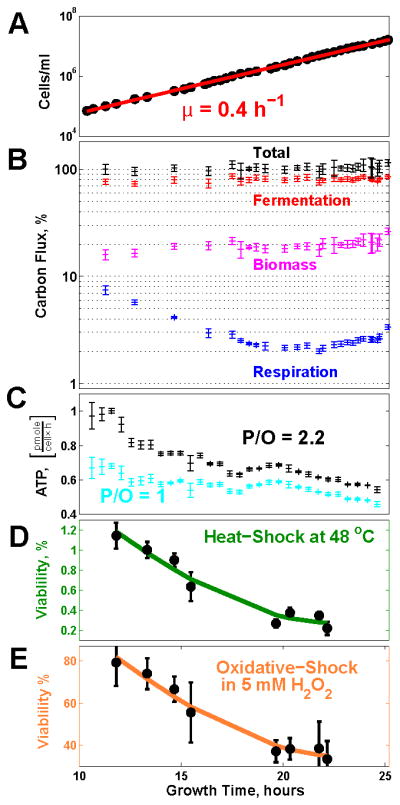

Figure 3. The Fraction of Glucose Carbon Flux Incorporated into Biomass and the Sensitivity to Stress Increase While the Growth Rate Remains Constant.

(A) Exponential increase in the number of cells indicates a constant doubling period.

(B) The fraction of carbon flux from glucose (moles of carbon per hour) directed into the major metabolic pathways, as computed from the gas and biomass data, evolves continuously; the sum of the fluxes through these pathways (total) can account, at all time points, for the carbon intake flux from glucose; see Supplemental Information.

(C) The ATP flux was estimated from the fluxes of CO2 and O2 in Figure 2E–F for low efficiency of oxidative phosphorylation, 1 ATP per oxygen atom (16 ATPs/glucose), and for high efficiency, 2.2 ATPs per oxygen atom (30.4 ATPs/glucose).

(D) The ability of the cells to survive heat shock (48°C for 10 min) declines during the exponential growth phase. Stress sensitivity was quantified by counting colony-forming units (CFU) on YPD plates.

(E) The ability of the cells to survive oxidative-shock (5mM H2O2 for 10 min) declines during the exponential growth phase.

In all panels, error bars denote standard deviations. See also Figure S3.

ATP Production and Stress Resistance Decrease during Exponential Growth

Increasing the rate of aerobic glycolysis is often modeled as a metabolic requirement for increasing the rate of growth (Newsholme et al., 1985; Pfeiffer et al., 2001; Molenaar et al., 2009; Heiden et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2010; Shlomi et al., 2011; Lunt and Vander Heiden, 2011; Ward and Thompson, 2012). Since the growth rate remains constant during the exponential growth phase (Figure 2A; Figure 3A), maximizing growth rate cannot be the only factor accounting for the increasing rate of aerobic glycolysis that we measured (Figure 2E; Figure 3B). Other factors must also influence the rate of aerobic glycolysis.

The reduced oxygen consumption per cell (Figure 2F) and the slight increase in the fraction of glucose carbon directed to biomass synthesis (Figure 3B) suggest a hypothesis, namely that the increasing rate of aerobic glycolysis might reduce the ATP flux while the cells maintain the same growth rate. To test this hypothesis, we used the O2 and CO2 fluxes (Figure 2C) to estimate the rate of ATP production over the range of reported efficiency of oxidative phosphorylation (Hinkle, 2005); see Supplemental Information. This result suggests decreasing rates of total ATP production (Figure 3C), bolstering our hypothesis. The declines in respiration (Figure 2F) and ATP flux (Figure 3C) parallel declines in both heat and oxidative stress resistance (Figure 3D–E). In contrast to previous reports (Lu et al., 2009; Zakrzewska et al., 2011), we observe changes in stress resistance while the growth rate remains constant. If the rate of ATP production reflects the cellular energetic demands (Famili et al., 2003), the decreasing ATP flux likely reflects the energy demands associated with respiratory metabolism and stress survival. Thus, the reduced respiration during aerobic glycolysis can reduce the overall rate of energy production (likely reflecting energy demands) in cells maintaining a constant growth rate.

Global Remodeling of Gene Regulation during Exponential Growth

To further evaluate the extent of the metabolic remodeling at a constant doubling period and to identify its molecular basis, we measured the levels of both mRNAs and proteins during the two phases of exponential growth, on glucose or on ethanol (Figure 4). Proteins were labeled with tandem-mass-tags (TMT) and quantified by mass-spectrometry (MS), resulting in over 58, 000 quantified distinct peptides corresponding to over 5000 proteins at a false discovery rate (FDR) < 1%. The peptides where quantified at MS2 level, resulting in high reproducibility (Spearman ρ = 0.993 for swapped TMT labels; Figure S4A) and reliable estimates of fold changes (error < 30%) as verified from measuring the levels of the dynamic universal proteomics standard (UPS2) spiked into the yeast samples (Figure S4B). The accuracy of UPS2 fold changes was highest for peptides with low coisolation–inferences and thus quantifying proteins based only on peptides with low–coisolation improves the accuracy.

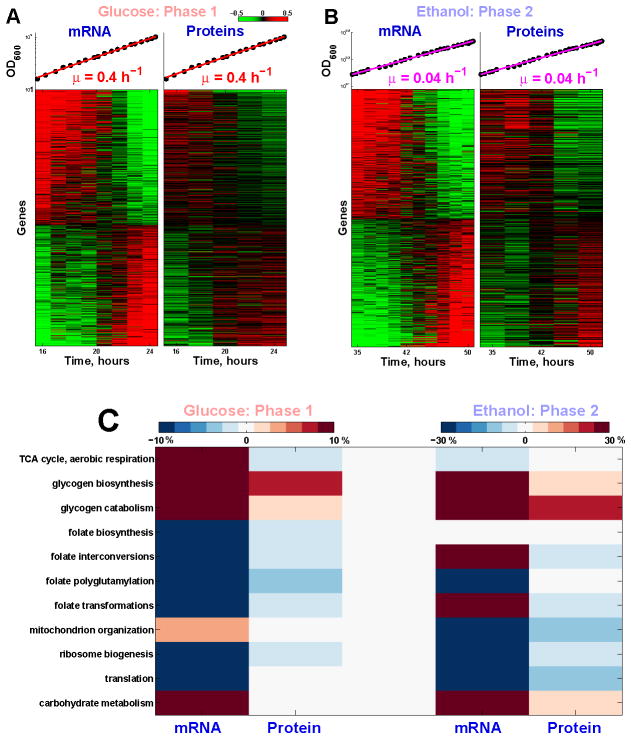

Figure 4. Global Remodeling of mRNA and Protein Regulation during Batch Growth at a Constant Growth Rate.

(A) Thousands of mRNAs and proteins (FDR< 1%) either increase or decrease monotonically in abundance during the first phase of exponential growth our culture. Levels are reported on a log2 scale with a 2 fold dynamic range. The mRNA and protein levels were measured in independent (biological replica) cultures and their correlation reflects the reproducibility of the measurements.

(B) Thousands of mRNAs and proteins (FDR< 1%) either increase or decrease monotonically in abundance during the second phase of exponential growth our culture.

(C) Metabolic pathways that show statistically significant dynamics (FDR < 1%) during the two phases of exponential growth; see Supplemental Information. The magnitude of change for each gene set is quantified as the average percent change in the level of its genes per doubling period of the cells.

See also Figure S4.

During each exponential growth phase, over 1000 genes (at FRD < 1%) increase or decrease monotonically at both the mRNA and the protein levels (Figure 4A–B); these genes are highly enriched (Bonferroni corrected p values < 10−42) for metabolic and protein synthesis functions (see Supplemental Information), emphasizing the global restructuring of metabolism even as the growth rate remains constant. A decline in protein synthesis genes has been observed previously during the last doubling before glucose exhaustion (Ju and Warner, 1994) and our data show that such decline begins much earlier and continues over many doublings at a constant rate.

Transcription Factors Mediating the Transcriptional Response

The changes in mRNA levels that we measured during exponential growth could reflect two regulatory mechanisms, changes in mRNA production and/or degradation rates. To identify transcription factors (TF) that mediate some of the changes in the rate of mRNA transcription, we overlapped known TF target genes (MacIsaac et al., 2006) with the sets of genes that either increase or decrease during the first phase of exponential growth (FDR < 1%); see Supplemental Information. The results (Table S1) indicate very significant overlap between the genes whose mRNAs decline and the targets of TFs involved in amino acid biogenesis (Gcn4p, Fhl1p, Leu3p, Arg81p, Met4p, and Met32p) and ribosomal biogenesis (Fhl1p, Sfp1p, Rap1p). The genes whose mRNA levels increase during the exponential growth phase overlap significantly with the targets of TFs regulating cell division (Fkh2p), stress response (Msn2p, and Msn4p) and redox metabolism (Aft1p and Aft2p). The functions and the changing activities of these TFs mirror the transcriptional responses from which they are inferred and adds a layer of mechanistic detail to the regulatory dynamics during exponential growth at a constant rate.

Dynamics of Enzymes Regulating Respiratory Metabolism

During the two phases of exponential growth, we systematically compared the dynamic trends in mRNA and protein levels for gene sets defined by all annotated biochemical pathways and by the gene ontology (GO). The statistical significance of the trends within a pathway, quantified by regression slopes, was evaluated by bootstrapping; see Supplemental Information and Figure S4C–D for details and all significant genes sets at FDR < 1%. Among the pathways exhibiting significant dynamics are gene sets (Figure 4C) mediating the measured changes in metabolic fluxes (Figure 2). The decline in the fraction of aerobically metabolized glucose (Figure 3B) and oxygen consumption (Figure 2F) parallels a decline in the key enzymes that funnel metabolites to respiration. These enzymes include the carnitine shuttle enzymes (Cat2p, Yat1p, Yat2p) that feed acetyl-CoA to the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and the rate–regulatory TCA cycle enzymes (Figure 5A and Figure S4) that catalyze the reactions through which metabolites enter the TCA. The levels of some mRNAs coding for TCA enzymes also decrease while the levels of other mRNAs coding for TCA enzymes increase (Figure S5A). The levels of mRNAs coding for the initial and flux–regulatory TCA enzymes decline in concert with the corresponding proteins, including pyruvate carboxylase (PYC) isoforms 1 and 2, citrate synthetases 2 and 3, and the isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (Figure 5A). Another transcriptional reflection of the decreased respiration during phase 1 is the decline of the mRNAs for the glutathione-dependent oxidoreductases (GRX3 and GRX4; Figure S5B), whose transcription is sensitive to peroxide and superoxide-radicals (Pujol-Carrion et al., 2006).

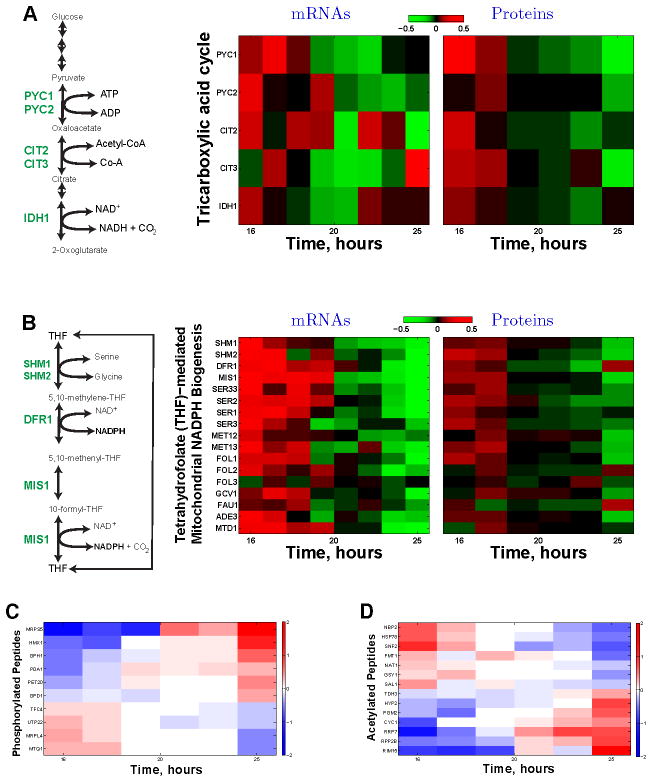

Figure 5. Dynamics of Enzymes and Post-translational Modifications Regulating Respiratory Metabolism at a Constant Growth Rate.

(A) The levels of enzymes (and their corresponding mRNAs) catalyzing the first rate-determining reactions of the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle decline, parallel to the decreased oxygen consumption (Figure 2F), during the first exponential growth phase. These enzymes include the pyruvate carboxylases (Pyc1p and Pyc2p), citrate synthetases (Cit1p and Cit2p), and the isocitrate dehydrogenase (Idh1p). See Figure 4 and Figure S4 for other related pathways that also show statistically significant declines. The data are displayed on a log2 scale with 2 fold dynamical range.

(B) The levels of enzymes (and their corresponding mRNAs) catalyzing the tetrahydrofolate (THF)-mediated mitochondrial NADPH biogenesis decline, parallel to the decreased oxygen consumption (Figure 2F), during the first exponential growth phase. These include all enzymes (Ser3p, Ser33p, Ser1p, Ser2p) catalyzing the serine biosynthesis from 3-phosphoglycerate, the hydroxymethyltransferases (Shm1p, Shm2p) and the mitochondrial NADPH synthetases: the dihydrofolate reductase (Dfr1p) and the mitochondrial C1–tetrahydrofolate synthase (Mis1p). See Figure 4 and Figure S4 for other related pathways that also show statistically significant declines. The data are displayed on a log2 scale with 2 fold dynamical range.

(C) Levels of phosphorylated peptides change during exponential growth at a constant rate.

(D) Levels of acetylated peptides change during exponential growth at a constant rate. The levels of peptides with post-translational modifications are shown on a log2 scale, and the corresponding proteins are marked on the y–axis.

See also Figure S5.

The mitochondrial respiratory chain generates reactive oxygen species (ROS) whose neutralization requires tetrahydrofolate (THF) mediated mitochondrial NADPH production from the carbon 3 of serine by the reactions shown in Figure 5B (Appling, 1991; Garcia-Martinez and Appling, 1993). All enzymes (and their corresponding mRNAs) producing NADPH from this pathways and from the associated pathways (Figure 5B and Figure S4) decline in parallel with the declining oxygen consumption (Figure 2) during the exponential growth phase. This concerted decline is particularly pronounced for the mitochondrial enzymes (Dfr1p and Mis1p) catalyzing the NADPH generating reactions (Figure 5B). The decline also includes all enzymes (Ser3p, Ser33p, Ser1p, Ser2p) catalyzing the serine biosynthesis from 3–phosphoglycerate. Since the growth rate and the cytoplasmic serine concentration remain constant (Figure S5C), the declining levels of serine biosynthetic enzymes likely reflect a decreasing flux of serine toward the folate-mediated mitochondrial NADPH production. Such a decrease in NADPH production could explain at least in part the decreased stress resistance that we measured (Figure 3D–E). This pathway for THF– mediated mitochondrial NADPH production is transcriptional upregulated with the growth–rate and increased respiration of yeast growing on ethanol carbon source (Slavov and Botstein, 2011), suggesting its broader significance for respiratory metabolism.

Similarly pervasive dynamics in metabolic pathways are observed during the second phase of exponential growth (Figure 4C and Figure S4C). The changing levels of metabolic enzymes synthesizing amino acids during the two exponential phases also lead to concerted changes in the intracellular amino acid levels (Figure S5C).

Post-translational Modifications during Exponential Growth

Hundreds of peptides quantified by MS carried post-translational modifications (PTMs), such as phosphorylation (of Ser and Thr) and acetylation (of Lys and Arg). Similar to the metabolic fluxes, mRNA and protein levels, the levels of peptides with PTMs increase or decrease over 10-fold dynamic range (Figure 5C–D; Figure S5D) during the exponential growth phases. These PTM dynamics reinforce the regulatory dynamics suggested by the metabolic fluxes, mRNAs, and proteins levels (Figure 4A–B). For example, the decreasing fraction of glucose carbon directed toward respiration is associated with the phosphorylation of the pyruvate dehydrogenase (Pda1p) that regulates the balance between respiration and fermentation and the acetylation of the glycolytic enzyme glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Tdh3p). Furthermore, the reduced respiration per cell (Figure 2F) is reflected in the phosphorylation pattern (Figure 5C) of mitochondrial respiratory and heme-related proteins (Pet20p and Hmx1p), of mitochondrial ribosomal proteins (Mrps5p and Mrpl4p), and the acetylation pattern (Figure 5D) of Cytochrome c (Cyc1p). The increasing metabolism of reserved carbohydrates during the first growth phase indicated by the mRNA and protein trends (Figure 4A–C; Figure S4) is also detected in the PTMs of participating enzymes (Gph1p and Pgm2p). Similarly, the translation-related changes in gene regulation (Figure 4A–C; Figure S4) are paralleled by translation-related PTMs including proteins involved in rRNA maturation and ribosome biogenesis (Utp22p, Rrp7p), elongation related factors (Hyp2p, Rpp2bp, Mtq1p), and tRNA synthesis (Tfc4p). Other proteins with dynamic PTMs during exponential growth (Figure 5C–D) include the proliferation regulating kinase Rim15p, the acetyltransferase (Nat1p), and the methyltransferase (Mtq1p), suggesting cross-talk among PTM signaling pathways. These results imply that quantifying PTM dynamics during well-characterized physiological states is a promising direction for characterizing the vast and largely unexplored space of PTM functions.

DISCUSSION

Six independent measurements (respiration, stress-resistance, transcripts, proteins, amino acids, and PTMs) demonstrate that metabolism, gene regulation, and stress sensitivity can change substantially even when the doubling time does not change over 9 generations. Specifically, we found that as aerobic glycolysis increases, a constant rate of biomass synthesis can be sustained with decreasing rate of ATP production. In other words, cells with reduced rate of respiration are able to maintain their growth rate constant with lower total ATP flux. Thus if the rate of ATP production reflects the cellular energy demands (Famili et al., 2003), our data suggest that while respiration is efficient in generating ATP, it may also substantially increase the energetic demands for growth, even when growth rate remains constant for many generations. Therefore, aerobic glycolysis may reduce the energetic demands of cellular growth by reducing the energy associated with respiration, such as that needed for detoxification of reactive oxygen species. Such decreased oxidative-stress defenses can naturally explain the decreasing stress-resistance that we measured in the course of exponential growth at a constant rate.

The decreasing rate of ATP production with the shift toward less aerobic metabolism prompts the reevaluation of the current estimates for the efficiency of oxidative phosphorylation based on the assumption that yeast growing in aerobic and in anaerobic conditions have identical energy requirements (Von Meyenburg, 1969; Verduyn et al., 1991; Famili et al., 2003). The decreased respiration in our cultures coincides with a concerted down-regulation, at both the mRNA and protein levels, of the TCA enzymes regulating the entry of metabolites into the respiratory pathway. This down-regulation of rate-determining enzymes not only supports the measured decrease in oxygen consumption but also suggests the molecular mechanisms mediating it. Similarly, we found that all pathways associated with the tetrahydrofolate–mediated production of mitochondrial NADPH decline in parallel to the decreased oxygen consumption and the decreased stress resistance, emphasizing the ROS burden of respiratory metabolism and the role of mitochondrial NADPH for relieving it.

Most work on aerobic glycolysis has focused on the correlation between aerobic glycolysis and growth rate (Warburg, 1956; Newsholme et al., 1985; De Deken, 1966; Brand and Hermfisse, 1997; Pfeiffer et al., 2001; Bauer et al., 2004; Gatenby and Gillies, 2004; Molenaar et al., 2009; Heiden et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2010; Shlomi et al., 2011; Lunt and Vander Heiden, 2011; Ward and Thompson, 2012). However, there are also examples of decoupling aerobic glycolysis and growth rate. These examples include high rates of fermentation measured in slowly growing yeast whose growth is limited by auxotrophic nutrients (Boer et al., 2008; Slavov and Botstein, 2013) and in quiescent mammalian fibroblasts whose growth is inhibited by serum withdrawal and/or contact inhibition (Lemons et al., 2010). Our data and analysis build upon and expand previous work showing decoupling of aerobic glycolysis and cellular growth–rate in several ways: (i) measurements of oxygen consumption (Figure 2), (ii) estimation of the total rate of ATP production (Figure 3), (iii) demonstration that the measured flux of carbon intake equals the measured flux of carbon release (Figure 3), (iv) measurements of stress resistance (Figure 3), (v) measurements of protein levels and PTMs (Figures 4–5). The measurement of oxygen consumption allows quantifying the extent of aerobic glycolysis by the respiratory quotient, and the carbon flux balance provides a cross-check of all measurements. Thus, we can rule out the possibility that our results are influenced by unmeasured fluxes, such as respiration, or by incorrectly measured fluxes. Our results are also unlikely to be influenced by mutations and external perturbations since our measurements were performed in wild–type cells growing in very well defined conditions. The estimate of energy production indicates that cells can support a constant growth rate while decreasing the rate of energy production and increasing the rate of aerobic glycolysis. Our results are consistent with and add to previous work (Brand and Hermfisse, 1997; Lemons et al., 2010; Jain et al., 2012; Chang et al., 2013) pointing to roles of aerobic glycolysis beyond maximizing cellular growth rate. Therefore, we conclude that understanding aerobic glycolysis requires taking into account multiple aspects of aerobic metabolism, such as mitochondrial NADPH production, not just the growth rate.

Many researchers (Ju and Warner, 1994; Shachrai et al., 2010; Zampar et al., 2013; Bren et al., 2013) have reported dynamic changes during batch growth. To our knowledge all previous reports were confined either to non-exponentially growing cultures or to a single exogenous protein or to the last generation of batch growth when growth rate, to the extent it can estimated, was declining. In contrast, we observed pervasive dynamics during the whole span (including early and middle phases) of batch growth, including during phases that are considered to represent a single well–defined steady-state (Newman et al., 2006; Belle et al., 2006; Pelechano and Pérez-Ortín, 2010; Schwanhäusser et al., 2011; Heyland et al., 2009; Youk and Van Oudenaarden, 2009; Boisvert et al., 2012).

Our data demonstrate that, at least for two very different growth conditions, exponentially growing cultures can change their metabolism continuously, prompting the investigation of metabolic and cell–signaling dynamics even in conditions previously assumed to represent steady–states (Silverman et al., 2010; Slavov et al., 2011, 2013). However, our data do not suggest that all exponentially growing cultures change their metabolism continuously and steady-state is impossible; many examples document constant, steady-state fluxes in exponentially growing cultures (Von Meyenburg, 1969; Küenzi and Fiechter, 1969; van Hoek P et al., 2000; Brauer et al., 2005, 2008; Slavov and Botstein, 2011, 2013). Our finding of changing metabolism and cell physiology at a constant growth rate provides a new direction for studying physiological dynamics and trade-offs, such as allowing flux-balance models to account for a constant growth rate at varying glucose uptake rates.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

All experiments described in the paper used a prototrophic diploid strain (DBY12007) with a S288c background and wild type HAP1 alleles, MATa/MATα HAP 1+. We grew our cultures in a commercial bioreactor (LAMBDA Laboratory Instruments), using minimal media with the composition of yeast nitrogen base (YNB) supplemented with 2 g/L D-glucose. CO2 and O2 were measured, every second, in the off-gas with zirconia and infrared sensors, respectively. All other measurements were done on samples taken from the culture via a sterile sampling port. Cell density was measured by a Coulter counter counting of at least 20000 cells (Slavov et al., 2011; Bryan et al., 2012). Stress sensitivity was assayed (Slavov et al., 2012) by exposing 250μl culture to stress for 10 min and subsequent plating on YPD plates to count colony forming units (survived cells). Details for all measurements and quality controls can be found in the Supplemental Information.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Increasing stress-sensitivity and aerobic glycolysis during exponential growth

Global remodeling of metabolism during 9 doublings at a constant rate

Parallel declines in respiration and in mitochondrial NADPH-producing enzymes

The deepest coverage (over 5000 quantified proteins) of the yeast proteome

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Manalis for the use of his coulter counter and K. Chatman for assistance with measuring amino acid levels, as well as J. Rabinowitz, D. Botstein, N. Wingreen, A. Murray, Q. Justman, E. Solis and members of the van Oudenaarden lab for critical discussions. This work was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health to A.v.O. (DP1 CA174420, R01-GM068957, U54CA143874) and to E.M.A. (R01-GM-096193) and Alfred P. Sloan Research Fellowship to E.M.A.

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes Extended Experimental Procedures, five supplemental figures and a table, and can be found with this article online at:

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Appling DR. Compartmentation of folate-mediated one-carbon metabolism in eukaryotes. The FASEB journal. 1991;5:2645–2651. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.5.12.1916088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer DE, Harris MH, Plas DR, Lum JJ, Hammerman PS, Rathmell JC, Riley JL, Thompson CB. Cytokine stimulation of aerobic glycolysis in hematopoietic cells exceeds proliferative demand. The FASEB journal. 2004;18:1303–1305. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1001fje. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belle A, Tanay A, Bitincka L, Shamir R, OShea EK. Quantification of protein half-lives in the budding yeast proteome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2006;103:13004–13009. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605420103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boer VM, Amini S, Botstein D. Influence of genotype and nutrition on survival and metabolism of starving yeast. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2008;105:6930–6935. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802601105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boisvert F-M, Ahmad Y, Gierliński M, Charrière F, Lamont D, Scott M, Barton G, Lamond AI. A quantitative spatial proteomics analysis of proteome turnover in human cells. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics. 2012:11. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.011429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand KA, Hermfisse U. Aerobic glycolysis by proliferating cells: a protective strategy against reactive oxygen species. The FASEB journal. 1997;11:388–395. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.11.5.9141507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brauer MJ, Huttenhower C, Airoldi EM, Rosenstein R, Matese JC, Gresham D, Boer VM, Troyanskaya OG, Botstein D. Coordination of Growth Rate, Cell Cycle, Stress Response, and Metabolic Activity in Yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:352–367. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-08-0779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brauer MJ, Saldanha AJ, Dolinski K, Botstein D. Homeostatic Adjustment and Metabolic Remodeling in Glucose-limited Yeast Cultures. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2005;16:2503–2517. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-11-0968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bren A, Hart Y, Dekel E, Koster D, Alon U, et al. The last generation of bacterial growth in limiting nutrient. BMC systems biology. 2013;7:27. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-7-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan A, Engler A, Gulati A, Manalis S. Continuous and long-term volume measurements with a commercial coulter counter. PloS one. 2012;7:e29866. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell S, Jones K, Shulman R. In vivo 31P nuclear magnetic resonance saturation transfer measurements of phosphate exchange reactions in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS letters. 1985;193:189–193. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(85)80148-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CH, Curtis JD, Maggi LB, Jr, Faubert B, Villarino AV, OSullivan D, Huang SCC, van der Windt GJ, Blagih J, Qiu J, et al. Posttranscriptional Control of T Cell Effector Function by Aerobic Glycolysis. Cell. 2013;153:1239–1251. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clasquin M, Melamud E, Singer A, Gooding J, Xu X, Dong A, Cui H, Campagna S, Savchenko A, Yakunin A, et al. Riboneogenesis in yeast. Cell. 2011;145:969–980. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Deken R. The Crabtree effect: a regulatory system in yeast. Journal of General Microbiology. 1966;44:149. doi: 10.1099/00221287-44-2-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBerardinis RJ, Mancuso A, Daikhin E, Nissim I, Yudkoff M, Wehrli S, Thompson CB. Beyond aerobic glycolysis: Transformed cells can engage in glutamine metabolism that exceeds the requirement for protein and nucleotide synthesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2007;104:19345–19350. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709747104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Famili I, Förster J, Nielsen J, Palsson BO. Saccharomyces cerevisiae phenotypes can be predicted by using constraint-based analysis of a genome-scale reconstructed metabolic network. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2003;100:13134–13139. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2235812100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Martinez LF, Appling DR. Characterization of the folate-dependent mitochondrial oxidation of carbon 3 of serine. Biochemistry. 1993;32:4671–4676. doi: 10.1021/bi00068a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatenby RA, Gillies RJ. Why do cancers have high aerobic glycolysis? Nature Reviews Cancer. 2004;4:891–899. doi: 10.1038/nrc1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyulai L, Roth Z, Leigh J, Chance B. Bioenergetic studies of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation using 31P NMR. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1985;260:3947. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartwell L, Hopfield J, Leibler S, Murray A. From molecular to modular cell biology. Nature. 1999;402:C47–C52. doi: 10.1038/35011540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiden MGV, Cantley LC, Thompson CB. Understanding the Warburg Effect: The Metabolic Requirements of Cell Proliferation. Science. 2009;324:1029–1033. doi: 10.1126/science.1160809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyland J, Fu J, Blank LM. Correlation between TCA cycle flux and glucose up-take rate during respiro-fermentative growth of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiology. 2009;155:3827–3837. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.030213-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinkle P. P/O ratios of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Bioenergetics. 2005;1706:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoek PV, Dijken JPV, Pronk JT. Effect of Specific Growth Rate on Fermentative Capacity of Baker’s Yeast. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1998;64:4226–4233. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.11.4226-4233.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain M, Nilsson R, Sharma S, Madhusudhan N, Kitami T, Souza AL, Kafri R, Kirschner MW, Clish CB, Mootha VK. Metabolite Profiling Identifies a Key Role for Glycine in Rapid Cancer Cell Proliferation. Science. 2012;336:1040–1044. doi: 10.1126/science.1218595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jouhten P, Rintala E, Huuskonen A, Tamminen A, Toivari M, Wiebe M, Ruohonen L, Penttilä M, Maaheimo H. Oxygen dependence of metabolic fluxes and energy generation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae CEN.PK113-1A. BMC Systems Biology. 2008;2:60. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-2-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju Q, Warner JR. Ribosome synthesis during the growth cycle of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1994;10:151–157. doi: 10.1002/yea.320100203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebs H, Eggleston L. The oxidation of pyruvate in pigeon breast muscle. Biochemical journal. 1940;34:442. doi: 10.1042/bj0340442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Küenzi MT, Fiechter A. Changes in carbohydrate composition and trehalase-activity during the budding cycle of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Archiv Fr Mikrobiologie. 1969;64:396–407. doi: 10.1007/BF00417021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemons JMS, Feng X, Bennett BD, Legesse-Miller A, Johnson EL, Raitman I, Pollina EA, Rabitz HA, Rabinowitz JD, Coller HA. Quiescent fibroblasts exhibit high metabolic activity. PLoS Biology. 2010;8:e1000514. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Zhou Y, Oltvai ZN, Vazquez Catabolic efficiency of aerobic glycolysis: the Warburg effect revisited. BMC Syst Biol. 2010;4:58. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-4-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C, Brauer MJ, Botstein D. Slow Growth Induces Heat-Shock Resistance in Normal and Respiratory-deficient Yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:891–903. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-08-0852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunt SY, Vander Heiden MG. Aerobic glycolysis: meeting the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Annual review of cell and developmental biology. 2011;27:441–464. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-092910-154237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacIsaac KD, Wang T, Gordon DB, Gifford DK, Stormo GD, Fraenkel E. An improved map of conserved regulatory sites for Saccharomyces cerevisiae. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:113–113. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKnight S. On getting there from here. Science Signalling. 2010;330:1338. doi: 10.1126/science.1199908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molenaar D, van Berlo R, de Ridder D, Teusink B. Shifts in growth strategies reflect tradeoffs in cellular economics. Molecular Systems Biology. 2009;5:323. doi: 10.1038/msb.2009.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monod J. The Growth of Bacterial Cultures. Annual Review of Microbiology. 1949;3:371–394. [Google Scholar]

- Newman JR, Ghaemmaghami S, Ihmels J, Breslow DK, Noble M, DeRisi JL, Weissman JS. Single-cell proteomic analysis of S. cerevisiae reveals the architecture of biological noise. Nature. 2006;441:840–846. doi: 10.1038/nature04785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newsholme E, Crabtree B, Ardawi M. The role of high rates of glycolysis and glutamine utilization in rapidly dividing cells. Bioscience reports. 1985;5:393–400. doi: 10.1007/BF01116556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelechano V, Pérez-Ortín JE. There is a steady-state transcriptome in exponentially growing yeast cells. Yeast. 2010;27:413–422. doi: 10.1002/yea.1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer T, Schuster S, Bonhoeffer S. Cooperation and Competition in the Evolution of ATP-Producing Pathways. Science. 2001;292:504–507. doi: 10.1126/science.1058079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portman MA. Measurement of unidirectional Pi → AT P flux in lamb myocardium in vivo. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Bioenergetics. 1994;1185:221–227. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(94)90213-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pujol-Carrion N, Belli G, Herrero E, Nogues A, de la Torre-Ruiz MA. Glutaredoxins Grx3 and Grx4 regulate nuclear localisation of Aft1 and the oxidative stress response in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Journal of cell science. 2006;119:4554–4564. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich PR. The molecular machinery of Keilin’s respiratory chain. Biochemical Society Transactions. 2003;31:1095–1105. doi: 10.1042/bst0311095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwanhäusser B, Busse D, Li N, Dittmar G, Schuchhardt J, Wolf J, Chen W, Selbach M. Global quantification of mammalian gene expression control. Nature. 2011;473:337–342. doi: 10.1038/nature10098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott M, Gunderson C, Mateescu E, Zhang Z, Hwa T. Interdependence of cell growth and gene expression: origins and consequences. Science. 2010;330:1099–1102. doi: 10.1126/science.1192588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shachrai I, Zaslaver A, Alon U, Dekel E. Cost of Unneeded Proteins in E. coli Is Reduced after Several Generations in Exponential Growth. Molecular cell. 2010;38:758–767. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon J, Williams S, Fulton A, Brindle K. 31 P NMR magnetization transfer study of the control of ATP turnover in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1996;93:6399. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shlomi T, Benyamini T, Gottlieb E, Sharan R, Ruppin E. Genome-Scale Metabolic Modeling Elucidates the Role of Proliferative Adaptation in Causing the Warburg Effect. PLoS Comput Biol. 2011;7:e1002018. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman S, Petti A, Slavov N, Parsons L, Briehof R, Thiberge S, Zenklusen D, Gandhi S, Larson D, Singer R, et al. Metabolic cycling in single yeast cells from unsynchronized steady-state populations limited on glucose or phosphate. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010;107:6946–6951. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002422107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slavov N, Airoldi EM, van Oudenaarden A, Botstein D. A conserved cell growth cycle can account for the environmental stress responses of divergent eukaryotes. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2012;23:1986–1997. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-11-0961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slavov N, Botstein D. Coupling among growth rate response, metabolic cycle, and cell division cycle in yeast. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2011;22:1997–2009. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-02-0132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slavov N, Botstein D. Decoupling Nutrient Signaling from Growth Rate Causes Aerobic Glycolysis and Deregulation of Cell-Size and Gene Expression. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2013;24:157–168. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E12-09-0670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slavov N, Carey J, Sara L. Calmodulin transduces Ca+2 oscillations into differential regulation of its target proteins. ACS Chemical Neuroscience. 2013;4:601–612. doi: 10.1021/cn300218d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slavov N, Macinskas J, Caudy A, Botstein D. Metabolic cycling without cell division cycling in respiring yeast. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:19090–19095. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1116998108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Hoek P, van Dijken JP, Pronk Regulation of fermentative capacity and levels of glycolytic enzymes in chemostat cultures of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Enzyme and Microbial Technology. 2000;26:724–736. doi: 10.1016/s0141-0229(00)00164-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verduyn C, Stouthamer A, Scheffers W, Dijken J. A theoretical evaluation of growth yields of yeasts. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 1991;59:49–63. doi: 10.1007/BF00582119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Meyenburg HK. Energetics of the budding cycle of Saccharomyces cerevisiae during glucose limited aerobic growth. Archives of Microbiology. 1969;66:289–303. doi: 10.1007/BF00414585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warburg O. On respiratory impairment in cancer cells. Science (New York, NY) 1956;124:269–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward PS, Thompson CB. Metabolic reprogramming: a cancer hallmark even warburg did not anticipate. Cancer cell. 2012;21:297–308. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiebe MG, Rintala E, Tamminen A, Simolin H, Salusjärvi L, Toivari M, Kokkonen JT, Kiuru J, Ketola RA, Jouhten P, Huuskonen A, Maaheimo H, Ruohonen L, Penttilä M. Central carbon metabolism of Saccharomyces cerevisiae in anaerobic, oxygen-limited and fully aerobic steady-state conditions and following a shift to anaerobic conditions. FEMS Yeast Research. 2008;8:140–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2007.00234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youk H, Van Oudenaarden A. Growth landscape formed by perception and import of glucose in yeast. Nature. 2009;462:875–879. doi: 10.1038/nature08653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakrzewska A, van Eikenhorst G, Burggraaff J, Vis D, Hoefsloot H, Delneri D, Oliver S, Brul S, Smits G. Genome-wide analysis of yeast stress survival and tolerance acquisition to analyze the central trade-off between growth rate and cellular robustness. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2011;22:4435–4446. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-08-0721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zampar GG, Kümmel A, Ewald J, Jol S, Niebel B, Picotti P, Aebersold R, Sauer U, Zamboni N, Heinemann M. Temporal system-level organization of the switch from glycolytic to gluconeogenic operation in yeast. Molecular systems biology. 2013;9:651. doi: 10.1038/msb.2013.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.