Abstract

Objective

The proper use of safety measures by welders is an important way of preventing and/or reducing a variety of health hazards that they are exposed to during welding. There is a lack of knowledge about hazards and personal protective equipments (PPEs) and the use of PPE among the welders in Nepal is limited. We designed a study to assess welders’ awareness of hazards and PPE, and the use of PPE among the welders of eastern Nepal and to find a possible correlation between awareness and use of PPE among them.

Materials and methods

A cross-sectional study of 300 welders selected by simple random sampling from three districts of eastern Nepal was conducted using a semistructured questionnaire. Data regarding age, education level, duration of employment, awareness of hazards, safety measures and the actual use of safety measures were recorded.

Results

Overall, 272 (90.7%) welders were aware of at least one hazard of welding and a similar proportion of welders were aware of at least one PPE. However, only 47.7% used one or more types of PPE. Education and duration of employment were significantly associated with the awareness of hazards and of PPE and its use. The welders who reported using PPE during welding were two times more likely to have been aware of hazards (OR=2.52, 95% CI 1.09 to 5.81) and five times more likely to have been aware of PPE compared with the welders who did not report the use of PPE (OR=5.13, 95% CI 2.34 to 11.26).

Conclusions

The welders using PPE were those who were aware of hazards and PPE. There is a gap between being aware of hazards and PPE (90%) and use of PPE (47%) at work. Further research is needed to identify the underlying factors leading to low utilisation of PPE despite the welders of eastern Nepal being knowledgeable of it.

Keywords: EPIDEMIOLOGY, OCCUPATIONAL & INDUSTRIAL MEDICINE

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is based on occupational safety and health which is a neglected area of research in Nepal.

Study methodology: use of pretested questionnaire, scientific calculation of sample size, random sampling and calculation of ORs.

Makes an attempt to bridge the information gap between the awareness and use of personal protective equipment (PPE) among welders in this part of the world.

The study highlights the frequent use of sunglasses and cloth masks as PPE which are not recommended.

The sample size of the current study is small which is reflected by the width of CIs.

The external validity of the study is limited in the context of urban cities which have more workshops and more welders.

Introduction

Occupational health aims at the promotion and maintenance of the highest degree of physical, mental and social well-being of workers in all occupations.1 Welding, a skilled profession, has been practiced since the ancient times.2 Welders join and cut metal parts using a flame or an electric arc and other sources of heat to melt and cut or to melt and fuse metal.3

Welding is a hazardous profession with a multiplicity of factors that can endanger the health of a welder, such as heat, burns, radiation (ultraviolet, visible and infrared), noise, fumes, gases, electrocution; uncomfortable postures involved in the work; high variability in the chemical composition of welding fumes, which differs according to the workpiece, method employed and surrounding environment and the routes through which these harmful agents enter the body.4 Some of the effects of welding on health include photokeratitis or arc eye, metal fume fever, decrease in lung function, pneumoconiosis, asthma, photodermatitis and fertility abnormalities.5–11

Hazards arising from workplaces could impair the health and well-being of the workers; therefore, it is necessary to anticipate, recognise, evaluate and control such hazards.12 The use of personal protective equipment (PPE) at all times is a good and safe practice by welders to protect from exposure to hazards and injuries during welding or cutting.13

Occupational safety and health (OSH) is not an old science; however, the working conditions for workers in general and welders in particular are unsatisfactory in Nepal. The fact that there is low awareness of safety measures and low frequency of their regular utilisation is a matter of concern. This may be due to various reasons like low level of education, lack of institutional training, age group structure and work experience along with non-adaptation of regulatory measures by concerned authorities for safety precautions.14 Welders in our study area do not have organised occupational health services, and to make matters worse, there is a lack of awareness regarding the importance of occupational safety at the workplace. The literature search showed that studies in Nepal have not tried to find out about the awareness of protective measures and the factors which facilitate their use. Thus, the current study was designed to assess awareness of occupational hazards and protective measures among welders working in three districts of eastern Nepal. We also tried to find the factors associated with awareness of occupational hazards and protective measures and the use of protective measures, and the possible relationship between awareness and actual use of PPE. This study was envisioned to highlight the need for research in the area of occupational health which is a neglected issue in our country.

Materials and methods

A cross-sectional study was designed to be conducted among welders working in three districts of eastern Nepal namely Jhapa, Morang and Sunsari from the period of July 2010 to July 2011.

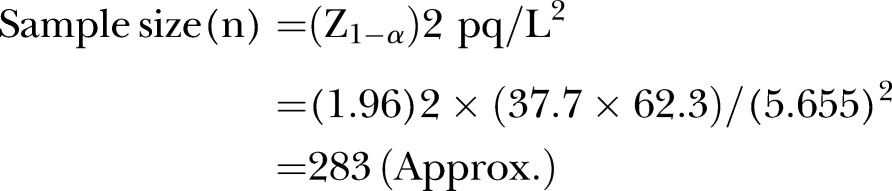

According to the available literature,15 the most prevalent health effects were arc eye injuries, followed by foreign bodies in the eyes, back/waist pain, metal fume fever, cuts/injuries from sharp metals, etc. Among these, the least prevalent (37.7%) work-related complaint was cut injuries from sharp metals.

Thus, prevalence (p)=37.7%.

Compliment of prevalence (q)=100–37.7=62.3%.

Permissible error at 15%, L=15% of 37.7=5.655.

|

Inflating the sample size by 5%, we got the estimated sample size of 298. We planned to interview 300 grill workers, 100 from each of the three districts.

The average number of welders present per shop was 3 (results based on preliminary survey of 15 workshops in the study area). Taking three welders per shop, the number of workers from each district required for the survey is298/3=100, that is, the number of workshops to be selected per district is100/3=34 shops. The workshops were selected through simple random sampling from a list of metal workshops provided by the Metal Workshops’ Association (GRILL BYABASAYI SANGH) using computer-generated random numbers.

Welders working in workshops listed in the Metal Workshops’ Association were included in the study. A workshop was visited with prior appointment from the workshop administration. The investigators conducted individual interviews of 45–90 min with the welders using a semistructured questionnaire. The questionnaire comprised open questions on age, level of education and duration of employment in years. These variables were divided into categories on the basis of literature review to show their impact on knowledge and use of PPE during analysis. Questions on awareness of hazards of welding, awareness of PPE and use of PPE were structured. The welders were first asked to list the hazards of welding followed by which, probing questions on specific hazards, light/radiation, welding fumes, sharp metals, electric current, heat, noise, sparks, vibration and physical environment at work were asked with yes/no answers. Similarly, for awareness and use of PPE, the welders were asked to list any PPE they were aware of and they used. This was again followed by yes/no option for welding helmet/face shield, protective gloves, welding goggles/eye shield, respirators/masks, sturdy footwear, apron, earmuffs and an open option for any other equipment they wore for their protection. The welders were asked to show us the PPE they used during welding.

Data collected were entered, edited and coded in a Microsoft excel sheet. The data were then exported to the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) V.11.5 for analysis. Bivariate analysis for categorical data was carried out using χ2 test. The strength of association was calculated using OR using Epi Info 7. The probability of significance was set at 5%.

Informed consent was taken from the participants ensuring their confidentiality and anonymity. Permission was sought from the welders to use their pictures for scientific publication.

Results

Data were collected from a total of 300 welders who agreed to participate in the current study. Since, permission was taken from the Metal Workshops’ Association and the authors have been working in this particular area with other programmes of OSH, all the workers gave a positive response leading to a response rate of 100%. All welders were men with a mean age of 31.29 years with an SD of 6.57 years. Almost half (48%) of the welders were in the age group of 30–39 years. In total, 93% of the welders in this study were literate. There were 16.3% of welders working for more than 10 years. The mean duration of employment of the welders in years in this study was 6.94 years (not shown in table).

The study showed that 90.7% of welders were aware of one or more hazards of welding. Excessive brightness (90.7%) was the most common hazard identified by the welders working in the area followed by sharp metals (86.7%), heat (83.7%), physical environment (83.3%), electrical current (80.30%), noise (75.70%), welding fumes (51.70%), sparks (44.3%) and vibration (17%) (not shown in table).

Table 1 shows that 90% of welders were aware of at least one kind of PPE while only 47.7% of welders use at least one kind of PPE during work. While welding goggles/eye shields (86.7%) were the most commonly reported PPE for use, the most commonly worn PPE was sturdy footwear (40.7%).

Table 1.

Distribution of welders according to awareness and use of personal protective equipment (PPE) (n=300)

| Number of welders* | Per cent* | |

|---|---|---|

| PPE types | ||

| Awareness among welders | ||

| At least one | 270 | 90.0 |

| Welding goggles/eye shield | 260 | 86.7 |

| Protective gloves | 255 | 85.0 |

| Sturdy footwear | 244 | 81.3 |

| Welding helmet/face shield | 162 | 54.0 |

| Apron | 161 | 53.7 |

| Masks | 156 | 52.0 |

| Earmuffs | 59 | 19.7 |

| Use among the welders | ||

| At least one | 143 | 47.7 |

| Sturdy footwear | 122 | 40.7 |

| Protective gloves | 70 | 23.3 |

| Welding goggles/eye shield | 54 | 18.0 |

| Apron | 50 | 16.67 |

| Welding helmet/face shield | 19 | 6.3 |

| Earmuffs | 16 | 5.3 |

*Multiple responses recorded per welder.

Sunglasses were considered protective and were used as a personal protective device by 74.3% of the 260 welders who reported being aware about welding goggles/eye shields as PPE. None of the welders used welding masks, while cotton mask was used by 45% of the 300 welders who reported being aware of welding masks. Sunglasses and cotton masks are however not included in the table, as they are not recommended PPE for welding.

An illustration of the sunglasses and cotton mask used by the welders in Nepal is depicted in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Welders at work using only sunglasses and cotton mask during welding in Nepal.

There was a positive association between level of education and awareness of hazards among the welders (p<0.001). Compared with illiterate welders, welders with primary education were 7 times more likely to be aware of the hazards of welding (OR=7.621, 95% CI 2.738 to 21.208), while the odds of awareness regarding welding were 60 times higher among welders with secondary level of education than welders who were illiterate (OR=60.5, 95% CI 14.517 to 252.132).

Duration of employment was seen to be negatively associated with the awareness of hazards among welders (p=0.01), that is, the chances of welders being aware of hazards was 66% more for those welders working for more than 5 years compared with those who had been working for 1–5 years as shown in table 2.

Table 2.

Factors associated with awareness of hazards among welders of eastern Nepal

| Variables | Aware of hazards |

p Value* | Unadjusted OR |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | OR | 95% CI | ||

| Education | |||||

| Illiterate | 10 | 11 | <0.001 | 1.00 | |

| Primary | 87 | 14 | 7.62 | 2.74 to 21.21 | |

| Secondary and above | 165 | 3 | 60.50 | 14.52 to 252.13 | |

| Duration of employment (years) | |||||

| 1–5 | 157 | 9 | 0.012 | 1.00 | |

| 6–10 | 73 | 12 | 0.34 | 0.14 to 0.86 | |

| 11 and more | 42 | 7 | 0.34 | 0.12 to 0.97 | |

*Calculated using χ2 at df=2.

Table 3 entails that awareness regarding the use of PPE was significantly associated with secondary level of education (p=0.004). The welders who had received secondary level of education were about five times (OR=4.93, 95% CI 1.50 to 16.23) more likely to be aware of PPE compared with illiterate welders.

Table 3.

Factors associated with awareness of personal protective equipment (PPE) among welders of eastern Nepal

| Aware of PPE | Unadjusted OR |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Yes | No | p Value* | OR | 95% CI |

| Education | |||||

| Illiterate | 16 | 5 | 0.004 | 1.00 | |

| Primary | 96 | 15 | 2.00 | 0.63 to 6.26 | |

| Secondary and above | 158 | 10 | 4.93 | 1.50 to 16.23 | |

| Duration of employment (years) | |||||

| 1–5 | 145 | 21 | 0.220 | 1.00 | |

| 6–10 | 80 | 5 | 2.13 | 0.84 to 6.38 | |

| 11 and more | 45 | 4 | 1.62 | 0.53 to 4.99 | |

*Calculated using χ2 at df=2.

There was a significant positive relation between reported use of PPE and secondary level of education (p<0.001). The welders who reported using PPE at work were two times more likely to have had secondary education or more (OR=2.167, 95% CI 1.865 to 5.430).

Interestingly, awareness regarding PPE did not find any significant association with duration of employment; however, the use of PPE was seen to be more among welders who had been working for a longer duration of time (p<0.001). The welders who had been working for 11 years or more were almost four times more likely to use PPE at work compared with those who had a work experience of 1–5 years (OR=3.98, 95% CI 1.99 to 7.97) as shown in table 4.

Table 4.

Factors associated with the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) at work among welders of eastern Nepal

| Variables | Use of PPE at work |

p Value* | Unadjusted OR |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | OR | 95% CI | ||

| Education | |||||

| Illiterate | 9 | 12 | <0.001 | 1.00 | |

| Primary | 30 | 81 | 0.49 | 0.18 to 1.29 | |

| Secondary and above | 104 | 64 | 2.16 | 0.86 to 5.43 | |

| Duration of employment (years) | |||||

| 1–5 | 64 | 102 | <0.001 | 1.00 | |

| 6–10 | 44 | 41 | 1.71 | 1.00 to 2.89 | |

| 11 and more | 35 | 14 | 3.98 | 1.99 to 7.97 | |

*Calculated using χ2 at df=2E.

Table 5 shows that the odds of using PPE during welding were twice as high among welders who were aware of the health hazards associated with welding than those who were not (OR=2.52, 95% CI 1.09 to 5.81). It was also seen that welders who knew about PPE were five times more likely to use them during welding compared with those who did not know about them (OR=5.13, 95% CI 2.34 to 11.26).

Table 5.

Association between awareness regarding hazards and personal protective equipment (PPE) and use of PPE at work

| Awareness | Use of PPE at work |

p Value* | Unadjusted OR |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | OR | 95% CI | ||

| Aware of hazard | |||||

| Not aware | 18 | 10 | 0.046 | 1.00 | |

| Aware | 223 | 49 | 2.52 | 1.09 to 5.81 | |

| Aware of PPE use | |||||

| Not aware | 15 | 15 | <0.001 | 1.00 | |

| Aware | 226 | 44 | 5.13 | 2.34 to 11.26 | |

*Calculated using χ2 at df=1.

All welders learned their welding skills working as apprentices to experienced welders. They had not had any formal training on welding, health and safety. Knowledge of hazards, PPE and use of PPE was limited to self-learning on the job.

Discussion

Almost half (48%) of the welders in our study were in the category of 30–39 years, similar to the finding by Sabitu et al,14 where majority (44.5%) fell in the same category but it differs from the study by Isah and Okojie15 in the same country where a higher proportion of welders (40.3%) were in the 20–29 years category. Although 93% of welders in the study had some schooling, only 90% of them had knowledge of one or more hazards of welding. These findings are similar to the study by Singh16 on jute mill workers of the same region.

The working population in this profession has a high turnover in this area with a very small number of people working for a longer duration. However, studies in Nigeria by Isah and Okojie15 show 74.8% of welders with an experience of more than 10 years, including 24.7% of welders with an experience of more than 21 years. Similarly, a Canadian study by El-Zein et al17 shows 81.8% of welders working for 10 years and more with 22.8% of welders aged 30 years and above and working for 20.33 years in this profession. The studies by Isah and Okojie15 and Sabitu et al14 in Nigeria show that there are welders even in the above-60 years category. The reasons for absence of welders above 49 years in our study could be due to migration of skilled experienced welders to other areas for better wages and opportunities.

This profession is regarded as the most hazardous profession and not all welders are aware of all the hazards.18 In our study, 90% of welders were aware of at least one hazard of welding. The comparison with other studies showed inconsistent results. The study by Isah and Okojie15 in Benin, Nigeria, showed 91.6% of welders being aware of one or more hazards of welding, while another study in Kaduna, Nigeria, by Sabitu K et al14 showed 77.9% of welders aware of one or more hazards of welding.

Excessive brightness was the most frequently identified hazard by the welders in our study. Welding fumes, which are a combination of highly toxic metals and their oxides,19 were identified as a hazard by 51.7% of welders. There were also 9.3% of welders who were not aware of any specific hazard in their work. They could not think of any harmful factor in welding.

In the study, 90.7% of welders were aware of welding goggles/eye shield to protect the eyes. The same percentage of welders were aware of at least one PPE. Although 75% of welders identified noise as a hazard at their workplace, only 19.7% were aware about earmuffs. The utilisation of at least one PPE among welders was 47.7%, as compared with the study by Sabitu et al14 (34.2%) and the study by Isah and Okojie15 (35.9%) in Nigeria. The most commonly used PPE were masks (45%), whereas the most common PPE worn were welding goggles in both Nigerian studies; 60.9% in the study by Sabitu et al14 and 35.9% in the study by Isah and Okojie.15 Welding goggles/face-shield use was seen among only 18% of welders in the current study.

It was found that a very high proportion of welders (74.3%) used sunglasses regularly at work. Sunglasses are not among the recommended PPE20 to protect the eye from welding radiation. The reasons for provision of sunglasses by the employer may be that they are cheap, easy available and comfortable. The sunglasses used were also not certified for UV protection. Masks used by welders in this study are also the commonly used cotton masks. These also do not meet the requirements21 as respirators for use during welding. It was also seen that more than half of the welders (52.3%) did not use any PPE during work.

Level of education had a significant relationship with awareness of hazard (p<0.05), awareness of PPE (p<0.05) and use of PPE (p<0.05) in this study. This showed that with an increase in the level of education among the population, awareness and safety practices also increased. Welders who have had a higher level of education have the tendency to read news, get updates which increases their awareness of hazards and PPE, and they tend to increase the practice of use of PPE as well. Sabitu et al14 also showed that awareness increased significantly with an increase in education level.

It was found that welders who were employed for a longer duration reported being less aware of the hazards of welding. It may be generally expected for the opposite to be true. The reason for such findings in this study could be that welders working for a longer duration fail to recognise the exposure as hazardous after being exposed to it for many years. However, this is just a possible explanation which needs to be further explored. In contrast, in terms of using PPE at work, welders who have been working for a longer duration report more use of PPE. It is seen that welders who have been working for a shorter duration are more aware of the hazards but their use of PPE is lower. One possible reason for this may be that younger people have a tendency of risk-taking behaviour. However, this also needs to be explored further in future studies.

Awareness of hazard (p<0.05) and awareness of PPE (p<0.05) when compared with the use of PPE at work showed significant relationship. Thus, the current study shows that when people are aware of hazards and equipments required to protect against them, the tendency to use those equipments increases.

All welders in the study learned welding through apprenticeship under an experienced welder for a few years. No welders in our study had any vocational training as compared with the findings of Sabitu et al14 that 8.5% of welders of Kaduna, Nigeria, went to a welding school. Learning by apprenticeship is a common practice in welding here; data by Sabitu et al14 also show that more than 90% welders in Kaduna learned welding by apprenticeship. There is no vocational training course or welding school so far for learning welding skills in this area.

The welders were also not trained or oriented regarding hazards and safety measures at work including basic first aid at work. This is also one of the reasons they are not aware of many hazards of their profession and the protective measures that they should take.

There are a few limitations of this study. Although the sample size was calculated with a scientific formula, the width of the CIs shows that the sample size is inadequate. A study with a larger sample size might provide a more accurate estimate of the study variables. Generalisability of this study to the other parts of Nepal, predominantly to urban cities, is limited as these cities have more workshops, more welders and, therefore, can have different working conditions.

Welding is a hazardous profession which exposes workers to various kinds of physical and chemical hazards in the absence of judicious and effective use of PPE. Unwanted exposure can lead to a variety of disease conditions among the welders. The use of recommended PPE at all times minimises exposure to these hazards. A lot of welders interviewed in the three districts of eastern Nepal were not aware of the hazards. Many welders are still not aware of PPE and a much smaller proportion among them actually uses PPE during welding. The mask and sunglasses being used are not the recommended PPE—respirators and welding goggles should be used instead.

Welders in the study area are not trained and have acquired their welding skills while working on the job. There is no culture of OSH among the welders and their employees. This study provides only a glance at the actual problems and risks involved in this profession. There is a gap between the knowledge of welders regarding awareness of hazards and PPE and the actual use of PPE at work by the same welders. This gap needs to be further explored, so that appropriate interventions can be planned to address it. With a high level of awareness present in this group, an intervention to increase the use of PPE is needed. OHS needs to be promoted by labour organisations in Nepal and should be highlighted by public health agencies which can make this a priority issue among the policy makers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to the study respondents who agreed to participate in this study and gave their invaluable time. They are also thankful to the Metal Workshops’ Association (GRILL BYABASAYI SANGH) which provided the list of workshops and also an important insight into the area and work practices.

Footnotes

Contributors: SSB developed the research idea, designed the questionnaire, collected data and wrote the preliminary drafts. SBS was responsible for streamlining the research idea, finalising the questionnaire and critiquing the drafts. RAS was involved in organising data, writing and critiquing the drafts. SRN was responsible for study designing and statistical analysis. PKP was involved and supervised the research idea, data measurement and appraisal of written drafts.

Funding: No funding was received for this research from any funding agency in the public, private or non-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Institutional Ethical Review Board, B P Koirala Institute of Health Sciences, Dharan, Nepal.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Park K. Park's textbook of preventive and social medicine. 20 ed. Jabalpur, India: Banarasidas Bhanot Publishers; 2007. Chapter 16, Occupational Health; pp 658–73. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antonini JM. Health effects of welding. Crit Rev Toxicol 2003;33:61–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vaidya SN. Occupational safety and situation in Nepal. In: Lehtinen S, Rantanen J, Elgstrand K, Liesivuori J, Peurala M, eds. Challenges to occupational health services in the regions: the national and international responses: proceedings of a workshop on 24 January 2005, Helsinki. Helsinki: Finnish Institute of Occupational Health, 2005:37–51 [Google Scholar]

- 4.International Labour Organisation (ILO). International classification of occupations 1968. Revised edn Geneva: International Labour Office; http://www.ilo.org/public/libdoc/ilo/1969/69B09_35_engl.pdf (accessed 5 Jul 2011) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zakhari S, Andersaon RS. American Welding Society, eds. Effects of welding on health. Vol II Miami, FL: 1981. Cited by Antonini JM. Health effects of welding. Crit Rev Toxicol 2003;33:61–103 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Voke J. Radiation effect on the eye-ocular effect of ultraviolet radiation. Optom Today 1999;8:30–5 Cited by: Davies KG, Asana U, Nku CO, et al. Ocular effects of chronic exposure to welding light on Calabar welders. Niger J Physiol Sci 2007;22:55–8 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liss GM. In: Ministry of Labor eds. Health effect of welding and cutting fume––an update. Toronto, Ontario, 1996. http://www.canoshweb.org/sites/canoshweb.org/files/odp/html/rp5.htm (accessed 20 Jun 2011) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sferlazza SJ, Beckett WS. The respiratory health of welders. Am Rev Respir Dis 1991;143:1134–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marek K, Starzynski Z. Pneumoconiosis in Poland. Int J Occup Med Environ Health 1994;7:13–21 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Contreas GR, Rousseau R, Chan-Yeung M. Occupational respiratory diseases in British Columbia, Canada in1991. Occup Environ Med 1994;51:710–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shehade SA, Roberts PJ, Difey BL, et al. Photodermatitis due to spot welding. Br J Dermatol 1987;117:117–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mortensen JT. Risk for reduced sperm quality among welders, workers with special reference to welders. Scand J Work Environ Health 1988;14:27–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Welding Society, eds. Personal protective equipment (PPE) for welding and cutting, safety and health fact sheet no. 33 2008. http://www.aws.org/technical/facts/FACT-33.pdf (accessed 15 Jan 2011)

- 14.Sabitu K, Iliyasu Z, Dauda MM. Awareness of occupational hazards and utilization of safety measures among welders in Kaduna Metropolis, Northern Nigeria. Ann Afr Med 2009;8:46–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Isah EC, Okojie OH. Occupational health problems of welders in Benin City, Nigeria. J Med Biomed Res 2006;5:64–9 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singh SB. Study of morbidity patterns among the workers of jute mill in eastern Nepal [MD Thesis] Dharan, Nepal, B.P. Koirala Institute of Health Sciences, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 17.El-Zein M, Malo J-L, Infante-Rivard C, et al. Prevalence and association of welding related systemic and respiratory symptoms in welders. Occup Environ Med 2003;60:655–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tierney MP. Analysis of mine injuries associated with maintenance and repair in metal and non-metal mines. U. S. Department of the Interior, Mining Enforcement and Safety Administration. 1977 cited by: Antonini JM. Health effects of welding Crit Rev Toxicol 2003;33:61–10312585507 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Waldron HA. Non neo-plastic disorders due to metallic, chemical and physical agents. In: Parkes WR. ed. Occupational lung disorders. 3rd edn Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann Ltd, 1994:629–31 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Norm M, Franck C. Long term changes in the outer part of the eye in welders. Prevalence of spheroid degeneration, pinguecula, pteryguim and cornea cicatrices. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1991;69:382–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rongo LM, Barten F, Msamangal GI, et al. Occupational exposure and health problems in small-scale industry workers in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: a situation analysis. Occup Med 2004;54:42–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.