Abstract

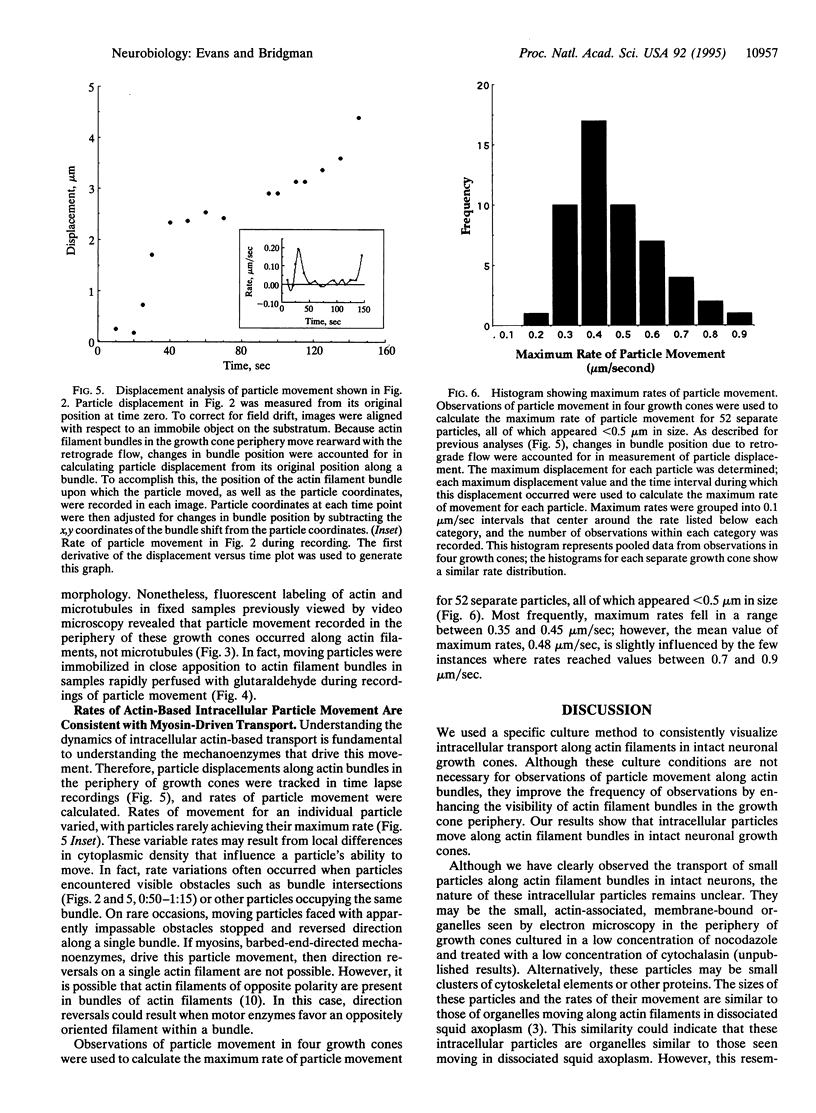

Organelle movement along actin filaments has been demonstrated in dissociated squid axoplasm [Kurznetsov, S. A., Langford, G.M. & Weiss, D. G. (1992) Nature (London) 356, 722-725 and Bearer, E.L., DeGiorgis, J.A., Bodner, R.A., Kao, A.W. & Reese, T.S. (1993) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90, 11252-11256] but has not been shown to occur in intact neurons. Here we demonstrate that intracellular transport occurs along actin filament bundles in intact neuronal growth cones. We used video-enhanced differential interference contrast microscopy to observe intracellular transport in superior cervical ganglion neurons cultured under conditions that enhance the visibility of actin bundles within growth cone lamellipodia. Intracellular particles, ranging in size from < 0.5-1.5 microns, moved along linear structures (termed transport bundles) at an average maximum rate of 0.48 micron/sec. After particle movement had been viewed, cultures were preserved by rapid perfusion with chemical fixative. To determine whether particle transport occurred along actin, we then used fluorescence microscopy to correlate this movement with actin and microtubule distributions in the same growth cones. The observed transport bundles colocalized with actin but not with microtubules. The rates of particle movement and the association of moving particles with actin filament bundles suggest that myosins may participate in the transport of organelles (or other materials) in intact neurons.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Allen R. D., Metuzals J., Tasaki I., Brady S. T., Gilbert S. P. Fast axonal transport in squid giant axon. Science. 1982 Dec 10;218(4577):1127–1129. doi: 10.1126/science.6183744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bearer E. L., DeGiorgis J. A., Bodner R. A., Kao A. W., Reese T. S. Evidence for myosin motors on organelles in squid axoplasm. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993 Dec 1;90(23):11252–11256. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.23.11252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg H. C., Block S. M. A miniature flow cell designed for rapid exchange of media under high-power microscope objectives. J Gen Microbiol. 1984 Nov;130(11):2915–2920. doi: 10.1099/00221287-130-11-2915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridgman P. C., Rochlin M. W., Lewis A. K., Evans L. L. Contributions of multiple forms of myosin to nerve outgrowth. Prog Brain Res. 1994;103:99–107. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)61130-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheney R. E., Mooseker M. S. Unconventional myosins. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1992 Feb;4(1):27–35. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(92)90055-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheney R. E., O'Shea M. K., Heuser J. E., Coelho M. V., Wolenski J. S., Espreafico E. M., Forscher P., Larson R. E., Mooseker M. S. Brain myosin-V is a two-headed unconventional myosin with motor activity. Cell. 1993 Oct 8;75(1):13–23. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(05)80080-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dailey M. E., Bridgman P. C. Vacuole dynamics in growth cones: correlated EM and video observations. J Neurosci. 1993 Aug;13(8):3375–3393. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-08-03375.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forscher P., Smith S. J. Actions of cytochalasins on the organization of actin filaments and microtubules in a neuronal growth cone. J Cell Biol. 1988 Oct;107(4):1505–1516. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.4.1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M. I., Argiro V. Techniques in the tissue culture of rat sympathetic neurons. Methods Enzymol. 1983;103:334–347. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(83)03022-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsov S. A., Langford G. M., Weiss D. G. Actin-dependent organelle movement in squid axoplasm. Nature. 1992 Apr 23;356(6371):722–725. doi: 10.1038/356722a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis A. K., Bridgman P. C. Nerve growth cone lamellipodia contain two populations of actin filaments that differ in organization and polarity. J Cell Biol. 1992 Dec;119(5):1219–1243. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.5.1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C. H., Forscher P. Growth cone advance is inversely proportional to retrograde F-actin flow. Neuron. 1995 Apr;14(4):763–771. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90220-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mermall V., McNally J. G., Miller K. G. Transport of cytoplasmic particles catalysed by an unconventional myosin in living Drosophila embryos. Nature. 1994 Jun 16;369(6481):560–562. doi: 10.1038/369560a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vale R. D., Schnapp B. J., Reese T. S., Sheetz M. P. Organelle, bead, and microtubule translocations promoted by soluble factors from the squid giant axon. Cell. 1985 Mar;40(3):559–569. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90204-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]