Abstract

Identification of therapeutic strategies that might enhance the efficacy of B-cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2) inhibitor ABT-737 [N-{4-[4-(4-chloro-biphenyl-2-ylmethyl)-piperazin-1-yl]-benzoyl}-4-(3-dimethylamino-1-phenylsulfanylmethyl-propylamino)-3-nitro-benzenesulfonamide] is of great interest in many cancers, including glioma. Our recent study suggested that Akt is a crucial mediator of apoptosis sensitivity in response to ABT-737 in glioma cell lines. Inhibitors of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt are currently being assessed clinically in patients with glioma. Because PI3K/Akt inhibition would be expected to have many proapoptotic effects, we hypothesized that there may be unique synergy between PI3K inhibitors and Bcl-2 homology 3 mimetics. Toward this end, we assessed the combination of the PI3K/Akt inhibitor NVP-BKM120 [5-(2,6-dimorpholinopyrimidin-4-yl)-4-(trifluoromethyl)pyridin-2-amine] and the Bcl-2 family inhibitor ABT-737 in established and primary cultured glioma cells. We found that the combined treatment with these agents led to a significant activation of caspase-8 and -3, PARP, and cell death, irrespective of PTEN status. The enhanced lethality observed with this combination also appears dependent on the loss of mitochondrial membrane potential and release of cytochrome c, smac/DIABLO, and apoptosis-inducing factor to the cytosol. Further study revealed that the upregulation of Noxa, truncation of Bid, and activation of Bax and Bak caused by these inhibitors were the key factors for the synergy. In addition, we demonstrated the release of proapoptotic proteins Bim and Bak from Mcl-1. We found defects in chromosome segregation leading to multinuclear cells and loss of colony-forming ability, suggesting the potential use of NVP-BKM120 as a promising agent to improve the anticancer activities of ABT-737.

Introduction

Malignant gliomas are aggressive, highly invasive brain tumors that have proven largely refractory to conventional treatment modalities such as surgery, irradiation, and cytotoxic chemotherapy (Pollack, 1994; DeAngelis 2001; Maher et al., 2001; Wen and Kesari, 2008). Recently, there have been important advances in our understanding of the molecular pathogenesis of malignant gliomas and progress in treating them. No underlying cause has been identified for the majority of malignant gliomas. Insight into the molecular pathogenesis of glioblastoma has led to the recent development of targeted therapeutic strategies aimed at the interruption of key molecular signaling pathways. However, gliomas have coactivation of multiple tyrosine kinases, as well as redundant signaling pathways, thus limiting the activity of single agents. We, among others, have focused on inhibitors that target receptor tyrosine kinases, such as epidermal growth factor receptor, platelet-derived growth factor receptor, and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor, as well as signal-transduction inhibitors targeting B-cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2), nuclear factor-кB, and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) in malignant human glioma (Jane et al., 2006, 2011; Premkumar et al., 2006a,b, 2010, 2012). Several Bcl-2 proteins are up-regulated in glioma; however, the mechanisms of up-regulation and their roles in resistance to cancer therapy remain unclear. Members of the Bcl-2 family are essential factors in the control of the intrinsic apoptosis pathway. ABT-737 is a rationally designed small molecule that binds with high affinity to Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL but not Mcl-1, and antagonizes their antiapoptotic function (Oltersdorf et al., 2005). The Bcl-2 homology 3 (BH3)-mimetic ABT-737 and related compounds act as single agents to induce apoptosis only in cancer cells that are dependent on Bcl-2 or Bcl-xL for survival (Certo et al., 2006; Konopleva et al., 2006; Del Gaizo Moore et al., 2007). For example, ABT-737 has shown efficacy in experimental models of B-cell malignancy; it induces apoptosis in chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells (Oltersdorf et al., 2005; Vogler et al., 2008, 2009), acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells (High et al., 2010), and primary follicular lymphoma cells and small-cell lung carcinoma cell lines (Oltersdorf et al., 2005). We, among others, have seen only weak activity against most solid tumor cell lines, such as gliomas (Tagscherer et al., 2008; Debien et al., 2011; Premkumar et al., 2012; Jane et al., 2013). Combination with the proteasomal inhibitor bortezomib (Premkumar et al., 2012), temozolomide (Voss et al., 2010), the survivin inhibitor YM-155 (Jane et al., 2013), or tumor necrosis factor–related apoptosis-inducing ligand (Cristofanon and Fulda 2012), significantly enhances ABT-737-induced glioma cytotoxicity, whereas inactivation of PTEN limits the therapeutic efficacy of ABT-737 (Premkumar et al., 2012), suggesting that the combined use of BH3 mimetics with Akt inhibition could be a novel and effective therapeutic approach for the management of malignant human glioma.

Aberrant activation of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt signaling pathway occurs in many types of cancers, including glioma, largely due to the prominent overexpression of epidermal growth factor receptor and platelet-derived growth factor receptor (Maher et al., 2001). One of the most frequently mutated tumor-suppressor genes in human cancer, PTEN, shows a very high frequency of mutations, estimated at >50% in glioblastoma (Salmena et al., 2008), leading to constitutive activation of Akt signaling. Accordingly, PI3K/Akt is an attractive target for small-molecule inhibitor therapy, with the expectation that blocking the activity of this lipid kinase and downstream survival kinase targets should lead to effective killing of cancer cells dependent on these pathways. NVP-BKM120, a 2,6-dimorpholino pyrimidine derivative, is a novel, potent, and highly selective pan-class I PI3K inhibitor. In preclinical studies it has been shown to be active in suppressing proliferation and inducing apoptosis of cancer cell lines and in inhibiting the growth of human tumors (xenografts) in mice at tolerated doses (Koul et al., 2012; Maira et al., 2012). Phase I clinical trials showed that overall, NVP-BKM120 was well tolerated (Bendell et al., 2012) and phase II clinical trials are ongoing. Several recent publications emphasized the enhanced antitumor effects in mouse models when NVP-BKM120 was combined with inhibitors of other signaling pathways (Ren et al., 2012).

Recently, we have used high-throughput RNA-interference screening to identify targets for rational combination therapies in glioma. We have found that silencing of antiapoptotic BCL-2 family members, nuclear factor-κB, or Akt potently reduces cell viability (Thaker et al., 2009, 2010a,b; Kitchens et al., 2011). Because ABT-737 has poor affinity for antiapoptotic Mcl-1, a downstream target in the PI3K/Akt pathway, and increased cellular Mcl-1 and Akt levels were found to be associated with resistance to ABT-737 (Qian et al., 2009; Premkumar et al., 2012; Spender and Inman 2012; Russo et al., 2013), we hypothesized that targeting Mcl-1 or regulators of its expression (PI3K/Akt signaling pathway) in combination with ABT-737 may be a useful strategy for the treatment of glioma. Here, we show that NVP-BKM120 induces apoptosis as a single agent. Inhibition of PI3K by NVP-BKM120 augments ABT-737–induced apoptosis in PTEN-deficient glioma cell lines to overcome resistance to ABT-737.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines.

The human glioma cell lines U87 (PTEN deleted, p53 wild type) and T98G (PTEN mutant, p53 mutant) were purchased from the ATCC (Manassas, VA). LN18 (PTEN wild type, p53 mutant), LN229 (PTEN wild type, p53 mutant), and LNZ308 (PTEN deleted, p53 deleted) were provided by Dr. Nicolas de Tribolet (Lausanne, Switzerland). The U87 and T98G cells were maintained in MEM, and the LN18, LN229, and LNZ308 cells were maintained in α-minimum essential medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, l-glutamine, nonessential amino acid, sodium pyruvate, penicillin, and streptomycin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Primary cultures were obtained from freshly resected tissues after surgical removal under an institutional review board–approved protocol for acquisition and use of tumor tissue collected at the time of tumor resection. We also obtained primary glioblastoma (GBM) cells from Conversant Biologics (Huntsville, AL), which were cultured in DMEM/F12 (Invitrogen).

Reagents.

Compounds used in our studies included the small-molecule Akt inhibitor, NVP-BKM120 (referred as BKM120 in this article) and the Bcl-2 inhibitor ABT-737 and were purchased from Chemie Tek (Indianapolis, IN). Necrostatin-1 and calpeptin were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). The caspase inhibitors were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Commercially available antibodies used for immunoblot or immunohistochemical detection of Akt, p-Akt (Ser473 or Thr308), JNK, p-JNK, p-H2AX, p-histone H3 (Ser10), S6-kinase, pS6-kinase (Thr389), S6 ribosomal protein, pS6 ribosomal protein (Ser235/236), ERK, pERK, BIM, Mcl-1, Bak, Bax, smac/DIABLO, cytochrome c, apoptosis-inducing factor, Bid, p-Chk1, p-Chk2, total Chk-1, PARP, and caspase-3, -7, and -8 were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA).

3-[4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2yl]-5-[3-carboxymethoxyphenyl]-2-[4-sulfophenyl]-2H,tetrazolium Assay and Measurement of Cell Proliferation.

Cells were seeded in 96-well plates (5000 cells/well) in 100 μl of growth medium and incubated at 37°C for 24 hours before the addition of inhibitors or vehicle for 3 days. Cell growth assays were done using the CellTiter96 Aqueous Non-Radioactive Cell Proliferation Assay kit (Promega, Madison, WI), per manufacturer's instructions, to evaluate the effect the inhibitors and doses as described previously (Premkumar et al., 2013b). Absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 490 nm, and the absorbance values of treated cells are presented as a percentage of the absorbance of untreated cells. Drug concentrations required to inhibit cell growth by 50% (IC50) were determined by interpolation of dose-response curves using IBM SPSS Statistics 21 Premium software.

Colony-Formation Assay.

For this analysis, 250 cells were plated in six-well trays in growth medium, and after overnight attachment, cells were treated in culture dishes for 24 hours with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (control) and varying concentrations of BKM120 or ABT-737, or the combination of both. Cells were then washed with inhibitor-free medium and allowed to grow for 2 weeks under inhibitor-free conditions. Then, cells were fixed and stained at room temperature with Hema 3 Manual Staining System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Plates were scanned and images were assembled using Adobe Photoshop CS2 software (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA).

Annexin V Apoptosis Assay.

Apoptosis induction in vehicle- or inhibitor-treated cells was assayed by the detection of membrane externalization of phosphatidylserine using an annexin V assay kit (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen) as described previously (Premkumar et al., 2013b). Cells (2 × 105) were harvested at various intervals after treatment, washed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and resuspended in 200 ml of binding buffer. Annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate and 1 mg/ml propidium iodide were added, and cells were incubated for 15 minutes in a dark environment. Labeling was analyzed by flow cytometry with a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA).

Cell Cycle Analysis.

The effects of varying concentrations of inhibitors on cell cycle distribution were determined as described previously (Premkumar et al., 2013a). Cells treated with inhibitors or vehicle were collected and fixed with 70% ethanol on ice for 30 minutes and then washed with Hanks' balanced salt solution. After being resuspended in Hanks' balanced salt solution with 50 μg/ml RNase and 50 μg/ml propidium iodide, cell cycle distributions were analyzed using a Becton Dickinson flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA). The percentages of cell populations in each cell cycle phase (sub-G1, G1, S, G2-M) were calculated from DNA content histograms using CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry, San Jose, CA).

Immunoprecipitation and Western Blot Analysis.

Treated and untreated cells were washed in ice-cold PBS and lysed in buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, and 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM polyvinylidene difluoride, 2 mM Na3VO4, 2 mM β-glycerophosphate, 50 µM bestatin, 15 µM E-64d, 20 µM leupeptin, 10 µM pepstatin A, and 0.8 µM aprotinin. After 20 minutes on ice, the lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 15,000g for 30 minutes at 4°C. Equal amounts of total protein were separated by SDS-PAGE–4% to 12% Bis-Tris (NuPAGE, Novex) gels, electrotransferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (Invitrogen) membranes, and analyzed following standard procedures as described previously (Premkumar et al., 2012). The molecular weight marker SeeBlue Plus 2 Standards (Invitrogen) was used to determine the molecular weights of the bands. All immunoblots are representative of at least three independent experiments.

For immunoprecipitation, cell extracts were prepared by lysing cells on ice for 30 minutes in 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonic acid (CHAPS) lysis buffer (10 mM HEPES at pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 2% CHAPS, protease, phosphatase inhibitors). Lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 15,000g for 15 minutes at 4°C, and the protein concentrations in the supernatants were determined. Equal amounts of protein extracts were incubated overnight with primary antibody. Afterward, Dynabeads Protein G (Invitrogen) were added for 2 hours. Supernatant (nonimmunoprecipitated fraction) was recovered by magnetic separation, and G-protein beads (immunoprecipitated fraction) were washed with ice-cold CHAPS lysis buffer. The beads were boiled in SDS sample buffer. The presence of immunocomplexes was determined by Western blot analysis.

Bax/Bak Conformational Change.

To analyze conformational changes of Bax and Bak, cells were lysed in CHAPS lysis buffer (1% CHAPS, 10 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, and protease inhibitors) and immunoprecipitated in lysis buffer by using 500 μg of total cell lysate and 2.5 μg of either anti–Bax 6A7 (Sigma-Aldrich) or anti–Bak-Ab1 (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) antibodies that recognize conformationally changed Bax or Bak, respectively. Immunoprecipitates were then subjected to immunoblotting analysis using anti-Bax or anti-Bak polyclonal antibodies.

In Vitro Cross-Linking and Analysis of Bax Oligomerization.

Cytosolic and membrane fractions were prepared by selective plasma membrane permeabilization with 0.05% digitonin, followed by membrane solubilization with 1% CHAPS as described previously (Premkumar et al., 2012). In brief, control and experimental cells in dishes were treated with 0.05% digitonin in isotonic buffer (10 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM EGTA, pH 7.4) containing protease inhibitors—1 mM 4-(2-aminoethyl) benzenesulfonyl fluoride hydrochloride, 0.8 mM aprotinin, 50 mM bestatin, 15 mM E-64d, 20 mM leupeptin, and 10 mM pepstatin A—for 1–2 minutes at room temperature. The permeabilized cells were shifted to 4°C, scraped with a rubber policeman, and collected into centrifuge tubes. The supernatants (digitonin-extracted cytosolic fraction) were routinely collected after centrifugation at 15,000g for 10 minutes. After centrifugation, the pellet was washed with isotonic buffer and further extracted with ice-cold detergent (1% CHAPS) in isotonic buffer containing protease inhibitors for 60 minutes at 4°C to release membrane- and organelle-bound proteins, including mitochondrial cytochrome c. CHAPS-soluble (membrane fraction) fractions were collected by high-speed (15,000g) centrifugation for 10 minutes. The protein cross-linker dithiobis(succinimidyl)propionate (DSP) was dissolved in DMSO and prepared just before use. Equal amounts of CHAPS-extracted membrane fraction protein were incubated with 1 mM DSP for 45 minutes at room temperature and subsequently quenched by adding 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4. To prevent disruption of disulfide bridges and disassembly of Bax or Bak oligomers, SDS-PAGE was performed under nonreducing conditions.

Subcellular Fractionation.

Cells were treated with or without inhibitors and cytosolic proteins were fractionated as described by Nencioni et al. (2005). In brief, cells were resuspended in a lysis buffer containing 0.025% digitonin, 250 mM sucrose, 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10 µg/ml aprotinin, and 10 µg/ml leupeptin. After 10-minute incubation at 4°C, cells were centrifuged (2 minutes at 13,000g) and the supernatant (cytosolic fraction) was removed and frozen at −80°C for subsequent use. The resulting digitonin-insoluble pellet was further dissolved in 2% SDS buffer as a membrane-bound organellar fraction enriched with mitochondria. These two fractions were analyzed by immunoblotting.

DiOC6 Labeling and Detection of Mitochondrial Membrane Depolarization.

Mitochondrial membrane depolarization was measured as described previously (Premkumar et al., 2012). In brief, floating cells were collected, and attached cells were trypsinized and resuspended in PBS. Cells were loaded with 50 nM 3′,3′-dihexyloxacarbo-cyanine iodide (DiOC6; Molecular Probes, Invitrogen) at 37°C for 15 minutes. The positively charged DiOC6 accumulates in intact mitochondria, whereas mitochondria with depolarized membranes accumulate less DiOC6. Cells were spun at 3,000g, rinsed with PBS twice, and resuspended in 1 ml of PBS. Fluorescence intensity was detected by flow cytometry and analyzed with CellQuest software (BD Biosciences). The percentage of cells with decreased fluorescence was determined. Following acquisition of data for mitochondrial membrane depolarization, the cell fluorescence information was saved in the Flow Cytometry Standard (.fcs) format. These files were then accessed with the FlowJo analysis software (Tree Star, Inc., Ashland, OR). Through this software, the fluorescence data were plotted as histograms, which were converted into and saved as Scalable Vector Graphics (.svg) files. Using Inkscape (The Inkscape Team), an Open Source vector graphics editor, the data were compiled into two-dimensional histogram overlays for comparative analysis. The loss of mitochondrial membrane potential (∆ψm) was quantified in FlowJo by gating any left-shifted populations and subtracting from control.

Immunocytochemistry and Fluorescence Microscopy.

Cells were grown on chamber slides (Nalge, Nunc, Naperville, IL) in growth medium. After an overnight attachment period, cells were exposed to inhibitors or vehicle (DMSO) for various intervals. Cells were fixed for 15 minutes at room temperature in PBS containing 3.7% formaldehyde. After fixation, the cells were permeabilized in PBS containing 0.5% bovine serum albumin and 0.05% Triton X-100 for 15 minutes at room temperature and overnight at 4°C with monoclonal anti-α-tubulin–fluorescein isothiocyanate (1:50 dilution; Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS, with 0.5% bovine serum albumin. The cells were washed (3 × 5 minutes with 0.05% Triton X-100 in PBS and once in PBS). Nuclei were stained with propidium iodide. Preparations were dried, mounted, and observed with a Zeiss Axiophot fluorescent microscope.

Statistical Analysis.

All data represent at least three independent experiments and are expressed as mean ± S.D. For annexin V/propidium iodide (PI) assays and loss of mitochondrial membrane potential analysis (∆ψm), experiments were repeated three times at least in duplicate. Western and immunoblot analyses were repeated three times. Scanning densitometry was performed on Western blots using acquisition into Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems) followed by image analysis (UN-SCAN-IT gel, version 6.1; Silk Scientific, Orem, UT). Values in arbitrary numbers shown in the Western blots represent densitometer quantification of bands normalized to loading control. The statistical significance between groups was assessed using analysis of variance with post-hoc Tukey’s test (IBM SPSS Statistics 21 Premium software), and significance was accepted at P < 0.05.

Results

Antiproliferative Activity of BKM120 in a Panel of Glioma Cell Lines.

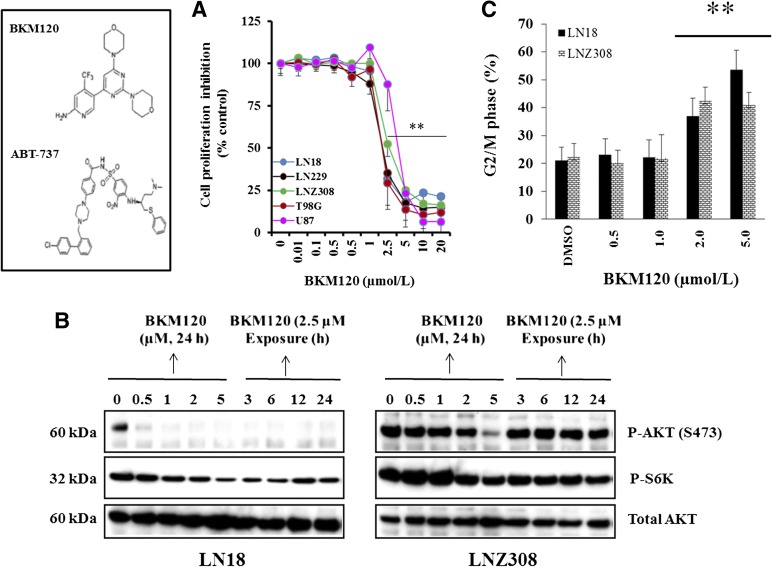

In the present study, to investigate the growth inhibitory effect of BKM120, we cultured glioma cells with various genotypic features (see Materials and Methods) for up to 72 hours and determined the viable cell number using the 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2yl]-5-[3-carboxymethoxyphenyl]-2-[4-sulfophenyl]-2H,tetrazolium assay. Growth of all five cell lines was inhibited by BKM120 in a dose-dependent manner, and the IC50 values for LN18, LN229, LNZ308, U87, and T98G cell lines were in the range of 2.5–5.0 µM. No obvious relationship between the sensitivity to BKM120 and PTEN or p53 status was apparent (Fig. 1A). To examine target inhibition, LN18 (PTEN wild type) and LNZ308 (PTEN deleted) cell lines were treated with increasing concentrations of BKM120 (0–5 µM) and incubated for various times (0–48 hours), and active Akt levels were examined. Phosphorylated (Ser473)-AKT was detected in cells treated with vehicle, and levels progressively declined with increasing concentrations of BKM120 (Fig. 1B; Supplemental Fig. 1). There was a minimal to modest level of pAKT (Thr308)-Akt detected in untreated control cells, which was completely inhibited by BKM120 (data not shown). Total Akt levels were not affected by treatment. The levels of phospho-S6 kinase, a direct substrate of Akt, decreased upon BKM120 treatment, indicating that the Akt activity is decreased (Fig. 1B; Supplemental Fig. 1). To demonstrate that BKM120 was specific to the Akt pathway, levels of other phosphorylated kinases that are not direct targets of Akt were measured. Levels of p(Thr202/Tyr204)-ERK as well as p(Thr183/Tyr185)-JNK did not change upon BKM120 treatment (data not shown). To investigate the effect on cell cycle progression, LN18 and LNZ308 cells were treated with varying concentrations of BKM120 for 24 hours, and the cell cycle profile was assessed by DNA content analysis using flow cytometry. When compared with untreated cells, BKM120-treated cells showed a tendency toward an increased proportion of cells in the G2/M phases of the cell cycle in LN18 and LNZ308 cell lines (Fig. 1C). Similar results were obtained for T98G, U87, and LN229 cell lines (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Antiproliferative activity of BKM120 in a panel of glioma cell lines. (A) Chemical structures of BKM120 and ABT-737 (left panel). Malignant human glioma cells were grown on 96-well plates in growth medium and, after an overnight attachment period, were exposed to selected concentrations of inhibitor or vehicle (DMSO) for 72 hours. Cell proliferation inhibition was assessed semiquantitatively by spectrophotometric measurement of 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2yl]-5-[3-carboxymethoxyphenyl]-2-[4-sulfophenyl]-2H,tetrazolium bioreduction. Points represent the mean of three measurements (right panel) carried out in triplicate. **P < 0.005, compared with vehicle-treated cells. (B) LN18 and LNZ308 cells were treated with BKM120 for the indicated concentrations/duration. Cell extracts were subjected to Western blot analysis with indicated antibodies. Total AKT served as loading control. (C) Cells were seeded at 60% confluence, allowed to attach overnight, and treated with the indicated concentrations of BKM120 for 24 hours. Cell cycle analysis using propidium iodide staining was performed as described under Materials and Methods. The G2/M phase of the cell cycle determined by FACS is shown. Data represent mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments carried out in triplicate. **P < 0.005, compared with vehicle-treated cells.

NVP-BKM120 Promotes ABT-737–Induced Toxicity in a Caspase-Dependent Manner.

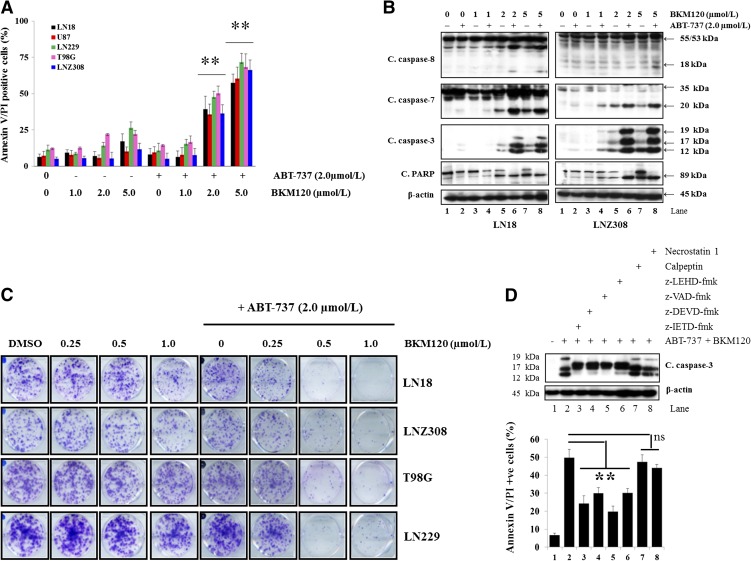

In our recent studies, we have demonstrated that ABT-737 induces minimal growth inhibition in glioma cell lines; however, simultaneous treatment with the proteasomal inhibitor bortezomib (Premkumar et al., 2012) or survivin inhibitor YM-155 (Jane et al., 2013) enhanced ABT-737–induced cytotoxicity in a synergistic manner. Because inhibition of apoptosis by Akt has been characterized in many cancer cell systems, including glioma, and Akt levels affect ABT-737 sensitivity (Premkumar et al., 2012), we questioned whether ABT-737 may be best used in combination with BKM120. First, to quantify the effects of the inhibitor combinations on apoptosis, LN18, LNZ308, LN229, T98G, and U87 cells treated with compounds for 24 hours were stained with annexin V and PI, and analyzed by flow cytometry. Three experiments were performed in duplicate with similar results. A representative bar graph is documented in Fig. 2A. Single-agent ABT-737 or BKM120 resulted in only modest annexin V/PI staining. On the other hand, cotreatment with ABT-737 and BKM120 enhanced annexin V/PI sensitivity. In accordance with the annexin V/PI analysis, the combination of ABT-737 and BKM120 strongly induced activated caspase-8, -7, -3, and PARP in LN18 (PTEN wild type) and LNZ308 (PTEN deleted) cell lines. The combination of BKM120 and ABT-737 strongly induced caspase-8 processing with 18-kDa cleavage product and caspase-3 with 19-, 17-, and 12-kDa cleavage products. Although dose-dependent cleavage of PARP is seen to a limited extent with BKM120 alone, there is substantially more dramatic cleavage (89-kDa fragment) of PARP with the combination of BKM120 and ABT-737 (Fig. 2B; Supplemental Fig. 2). Similar results were obtained for T98G, U87, and LN229 cell lines (data not shown). In addition to viability, colony-forming ability was confirmed by clonogenic growth assay in four different glioma cell lines. Neither ABT-737 nor BKM120 alone resulted in a significant reduction of viable cells; however, cotreatment of ABT-737 + BKM120 significantly inhibited colony-forming ability (Fig. 2C). Next, to further examine the role of the caspase signaling pathway, cells were treated with z-IETD-fmk (caspase-8 inhibitor); z-DEVD-fmk (caspase-3 inhibitor); z-VAD-fmk (pan caspase inhibitor) or z-LEHD-fmk (caspase-9 inhibitor), a cell-permeable caspase inhibitor; calpeptin (calpain inhibitor); or necrostatin-1 (inhibits necroptosis) prior to ABT-737 or BKM120 or the combination of both, and cell death was examined by annexin V/PI assay and Western blot analysis. As shown in Fig. 2D, ABT-737 + BKM120–induced cytotoxicity was significantly inhibited by caspase inhibitor pretreatment but not by calpeptin or necrostatin-1, indicating that caspase signaling pathways are critical for ABT-737 + BKM120–induced cell death (Fig. 2D; Supplemental Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

BKM120 promotes ABT-737-induced toxicity in a caspase-dependent manner. (A) LN18, LNZ308, T98G, U87, and LN229 cells were treated with ABT-737 (2.0 µM) or BKM120 (indicated concentration) or the combination of both for 24 hours. Frequency of apoptotic cells was determined by annexin V/PI binding assay. Simultaneous treatment with BKM120 and ABT-737 resulted in a significant increase in the apoptotic cell death. Data represent mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments carried out in triplicate. **P < 0.001, compared with BKM120 or ABT-737 as a single agent versus combination of ABT-737 plus BKM120. (B) LN18 and LNZ308 cells were treated with ABT-737 (2.0 µM) or BKM120 (indicated concentration) or the combination of both for 24 hours. Cell extracts were subjected to Western blot analysis with indicated antibodies. Cleaved fragments were densitometrically quantified and analyzed as described under Materials and Methods (Supplemental Fig. 2). (C) Human glioma cells were exposed to the indicated concentrations of BKM120 with or without ABT-737 for 24 hours. On the following day, the media were changed, complete media were added, and cells were grown for an additional 14 days in the absence of inhibitors. Control cells received equivalent concentrations of vehicle (DMSO). Colonies were fixed and stained as described under Materials and Methods. (D) LN18 cells were pretreated with 25 µM z-IETD-fmk (caspase-8 inhibitor), z-DEVD-fmk (caspase-3 inhibitor), z-LEHD-fmk (caspase-9 inhibitor), z-VAD-fmk (pan-caspase inhibitor), calpeptin (calpain inhibitor), or necrostatin-1 (necroptosis inhibitor) for 2 hours, followed by the combination of ABT-737 (2.0 µM) plus BKM120 (2.0 µM) for 24 hours. Control cells received an equivalent amount of DMSO. Apoptosis was analyzed by annexin/PI flow cytometry and Western blot (caspase-3 and β-actin). The cleaved fragment of caspase-3 (12 kDa) was densitometrically quantified and analyzed as described under Materials and Methods (Supplemental Fig. 3). Bar chart data represent mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments carried out in triplicate. **P < 0.005; ns, not significant.

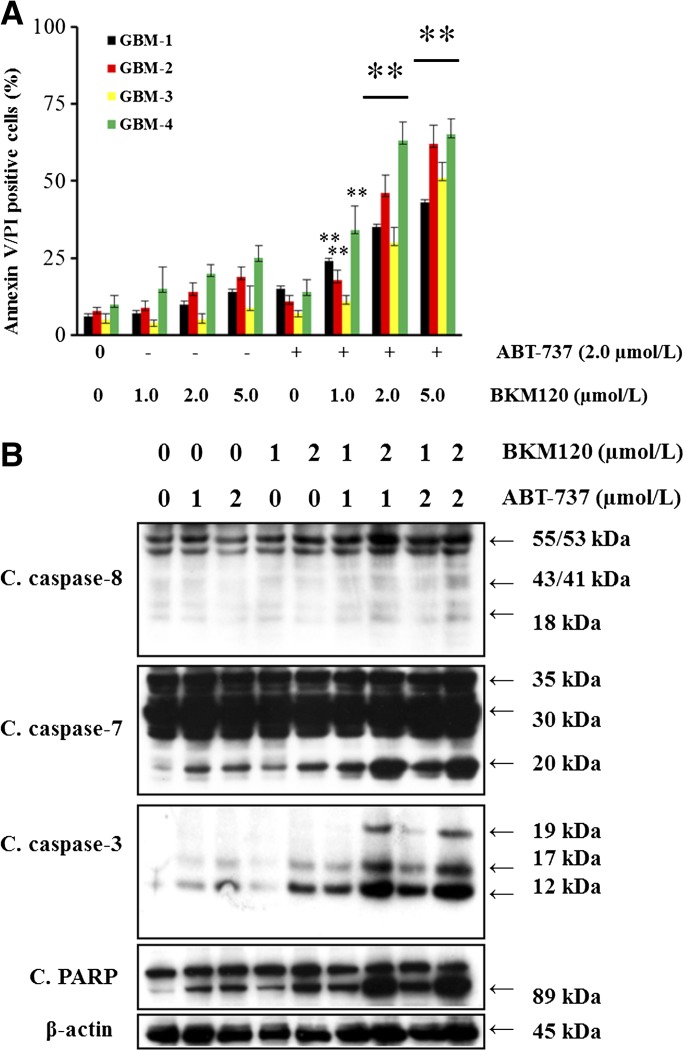

Sensitization of Primary Cultures of Cells Derived from Patients with Glioma.

To confirm that the increase in sensitivity was not restricted to established cell lines, primary cultures were established from cells collected from four patients diagnosed with brain tumor (histologically confirmed glioblastoma). Similar to the established cell lines, these cells were only modestly sensitive to ABT-737 or BKM120. However, the sensitivity of these cultures to ABT-737 was synergistically increased by cotreatment with NVP-BKM120, as demonstrated by annexin V/PI assay (Fig. 3A) and Western blot analysis (Fig. 3B; Supplemental Fig. 4). This suggests that BKM120 can, in principle, increase the sensitivity of primary cultures of GBM cells to ABT-737, but a larger study is necessary to quantify the proportion of such cultures that respond to these inhibitors.

Fig. 3.

Sensitization of primary cultures of cells derived from patients with glioma. (A) Primary cultures established from four GBM patients were exposed to ABT-737 (2.0 µM) or BKM120 (indicated concentration) or the combination of both for 24 hours, and frequency of apoptotic cells was determined by annexin V binding assay. Data represent mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments carried out in triplicate. **P < 0.005, compared with BKM120 or ABT-737 as a single agent versus the combination of ABT-737 plus BKM120). (B) In parallel, cell extracts (from GBM-4) were prepared, and equal amounts of protein were separated by SDS-PAGE and subjected to Western blot analysis with the indicated antibodies. The results of a representative study are shown; two additional experiments produced similar results. The protein levels have been quantified by densitometry and are shown in Supplemental Fig. 4.

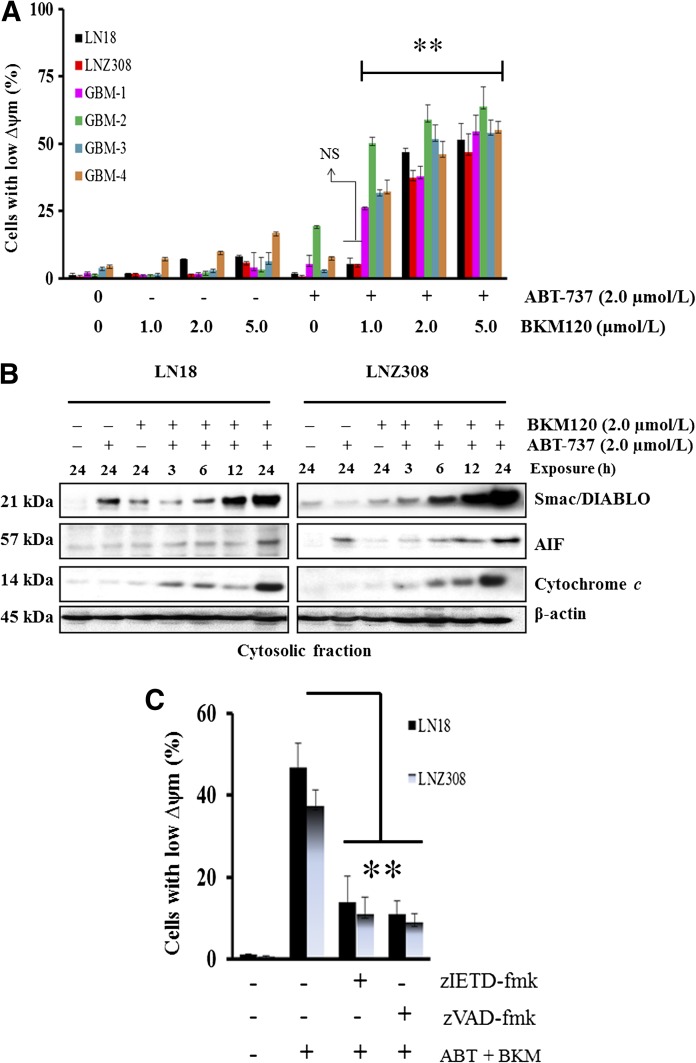

Loss of Mitochondrial Membrane Potential in ABT-737– and BKM120-Induced Cell Death.

Evidence is accumulating that mitochondria play a key role in the regulation of cell death (Tait and Green 2010). Among the sequence of events taking place in mitochondria during the course of cell death, loss of the ∆ψm and/or the release of soluble proteins in the intermembrane space, such as cytochrome c into the cytosol as a result of outer membrane permeabilization, appear to be the major events closely associated with cell death (Tait and Green 2010). To identify involvement of the mitochondria in ABT-737– and BKM120-induced apoptosis of glioma cells, we measured mitochondrial potential by using the DiOC6 probe. Primary GBM and established glioma cells were left untreated or treated with ABT-737 or BKM120 or the combination of both for 18 hours, stained with DiOC6, and then analyzed by flow cytometry. BKM120 and ABT-737 each induced a minimal decrease in mitochondrial ∆ψm. However, cotreatment with ABT-737 and BKM120 significantly increased the cell population with low mitochondrial membrane potential in both established and primary GBM cells (Fig. 4A). Because loss of mitochondrial membrane potential was associated with the release of various intermembrane proteins, which is a crucial event driving initiator caspase activation and apoptosis, we examined the release of cytochrome c, smac/DIABLO, and apoptosis-inducing factor in LN18 (PTEN wild type) and LNZ308 (PTEN deleted) cell lines. As identified by immunoblotting analysis, there is an accumulation of cytochrome c, Smac/DIABLO, and apoptosis-inducing factor in the cytosolic fraction (Fig. 4B; Supplemental Fig. 5) and a significant decrease in the mitochondrial membrane fraction (data not shown) under combined ABT-737 and BKM120 exposure. This apoptosis-associated redistribution of cytochrome c was further confirmed by immunofluorescence studies that identified a punctuate staining pattern in the cytoplasm of untreated cells, similar to the pattern produced by the mitochondria-specific Mitotracker red dye, and a more diffuse cytosolic staining in ABT-737 + BKM120–treated cells (data not shown). To determine whether the loss of mitochondrial membrane potential in glioma cells was a direct result of caspase activation, we examined the effect of z-IETD-fmk (caspase-8 inhibitor) and z-VAD-fmk (pan-caspase inhibitor) on ABT-737– and BKM120-induced loss of ∆ψm. Preincubation of cells with caspase-8 and pan-caspase inhibitors significantly inhibited the loss of ∆ψm, suggesting that ABT-737– and BKM120-induced loss of mitochondrial membrane potential lies upstream of initiator caspases (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

Loss of mitochondrial membrane potential in ABT-737 and BKM1120-induced cell death. (A) Established glioma cells (LN18, LNZ308) and primary cultures from four GBM patients (GBM-1, GBM-2, GBM-3, and GBM-4) were treated with BKM120 (indicated concentration), ABT-737 (2.0 µM) or the combination of both for 18 hours. The integrity of the mitochondrial membranes of the cells was examined by DiOC6 staining and flow cytometry. Decrease in fluorescence intensity reflected loss of ∆ψm. Data represent mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments carried out in triplicate. **P < 0.001, compared with BKM120 as a single agent versus combination of ABT-737 plus BKM120; NS, not significant). (B) LN18 and LNZ308 cells were treated with ABT-737 (2.0 µM) or BKM120 (2.0 µM) or the combination of both for the indicated duration. Cytosolic extract was prepared, and equal amounts of protein were separated by SDS-PAGE and subjected to Western blotting analysis with the indicated antibodies. The results of a representative study are shown; two additional experiments produced similar results. The protein levels have been quantified by densitometry and are shown in Supplemental Fig. 5. (C) LN18 and LNZ308 cells were pretreated with 25 µM z-IETD-fmk (caspase-8 inhibitor) or z-VAD-fmk (pan-caspase inhibitor) for 2 hours followed by the combination of ABT-737 plus BKM120 (2.0 µM each, ABT + BKM) for 18 hours. The integrity of the mitochondrial membranes of the cells was examined by DiOC6 staining and flow cytometry. Loss of mitochondrial membrane potential (∆ψm) is depicted in the bar chart. Data represent mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments carried out in triplicate. **P < 0.005.

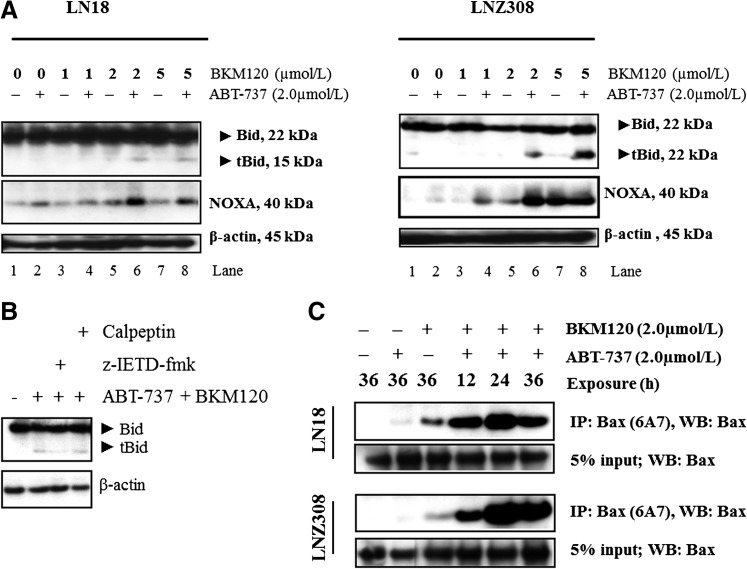

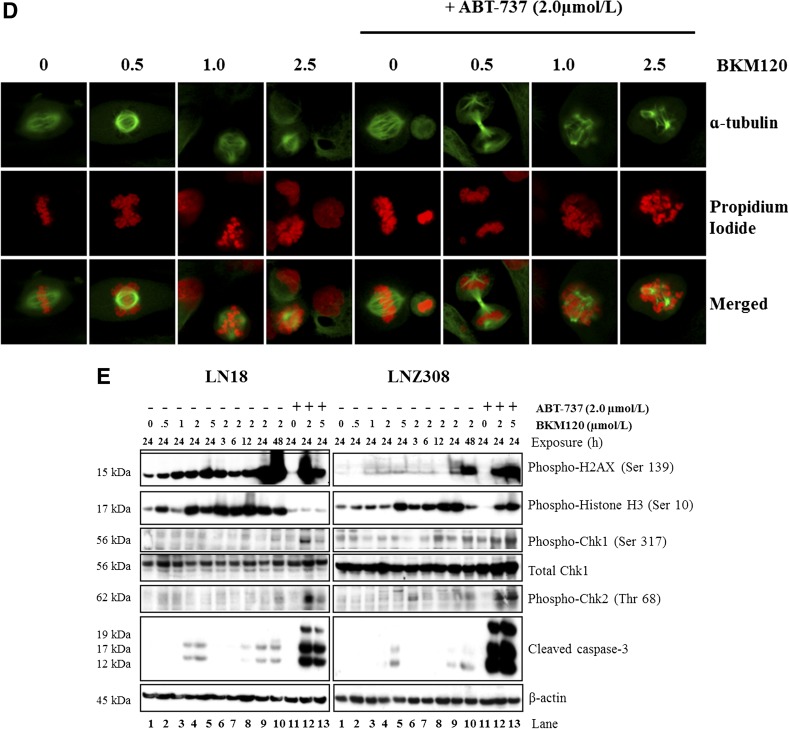

Noxa Activation and Truncation of Bid Are Crucial Events in ABT-737– and BKM120-Induced Apoptosis.

We (Premkumar et al., 2012; Jane et al., 2013), among others (Konopleva et al., 2006; van Delft et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2007), have shown that Mcl-1 and Noxa play crucial roles in determining ABT-737 sensitivity. Cotreatment with ABT-737 and BKM120 caused Noxa activation (Fig. 5A; Supplemental Fig. 6) and did not affect other Bcl-2 family members such as Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, or Mcl-1 (data not shown). Cross-talk between the extrinsic and intrinsic pathways occurs through caspase 8–mediated cleavage of Bid. Because activated caspase-8 can directly activate downstream effector caspases through mitochondria by cleaving the proapoptotic Bcl-2 family member Bid (Tait and Green 2010), we examined glioma cell lines by assessing drug-induced cleavage of Bid to its active, form: truncated Bid (tBid). After treatment with ABT-737 or BKM120, no Bid cleavage was seen after 24 hours, whereas cotreatment with ABT-737 and BKM120 induced a significant cleavage in LN18 (PTEN wild type; Fig. 5A; Supplemental Fig. 6, left panel) and LNZ308 (PTEN deleted; Fig. 5A; Supplemental Fig. 6, right panel) cell lines. Another enzyme that has been shown to be an apical activator of the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway is calpain. Calpain is a protease that has been demonstrated to induce the activation of Bid and other proapoptotic proteins through cleavage (Gil-Parrado et al., 2002). To examine the role of calpain in ABT-737- or BKM120-induced apoptosis, calpeptin, a specific inhibitor of calpain, was added to LN18 cells 2 hours prior to addition of ABT-737 plus BKM120 and was continuously present in the culture throughout the experiment. As shown in Fig. 5B, Bid cleavage induced by ABT-737 + BKM120 was not blocked by pretreatment with calpeptin (also see Supplemental Fig. 7). Annexin V/PI analysis further demonstrated that calpeptin or necrostatin-1 had no influence on ABT-737 + BKM120–induced apoptosis (Fig. 2D; Supplemental Fig. 3).

Fig. 5.

Noxa, Bax, Bak activation, and truncation of Bid are crucial events in ABT-737- and BKM120-induced apoptosis. (A) LN18 (PTEN wild type, left panel) and LNZ308 (PTEN deleted, right panel) cells were treated with ABT-737 (2.0 µM) or BKM120 (indicated concentration) or the combination of both for 24 hours. Cell extracts were subjected to Western blot analysis with indicated antibody. The results of a representative study are shown; two additional experiments produced similar results. The protein levels have been quantified by densitometry and the results are shown in Supplemental Fig. 6. (B) LN18 cells were pretreated with 25 µM z-IETD-fmk (caspase-8 inhibitor) or calpeptin (calpain inhibitor) for 2 hours followed by the combination of ABT-737 (2.0 µM) plus BKM120 (2.0 µM) for 22 hours. Cell extracts were subjected to Western blot analysis with indicated antibody. β-Actin served as the loading control. The protein levels have been quantified by densitometry, and the results are shown in Supplemental Fig. 7. (C) LN18 and LNZ308 cells were treated with ABT-737 (2.0 µM) or BKM120 (2.0 µM) or the combination of both for indicated duration and lysed with 1% CHAPS buffer. An equal amount of protein (500 µg) was immunoprecipitated with monoclonal anti-Bax (6A7; Sigma-Aldrich) antibody and then immunoblotted with polyclonal anti-Bax antibody (Cell Signaling Technology). Five percent of the whole-cell lysate (25 µg of protein) was subjected to Western blot analysis and probed with polyclonal anti-Bax antibody (Cell Signaling Technology) served as loading control. The results of a representative study are shown; two additional experiments produced similar results. Active Bax level has been quantified and is shown in Supplemental Fig. 8. (D) LN18 and LNZ308 cells were treated with ABT-737 [2.0 µM (A) or BKM120 (2.0 µM (B), or the combination of both (A and B)] for 24 hours and lysed with 1% CHAPS buffer. Control (C) received an equal amount of DMSO. An equal amount of protein (800 µg) was immunoprecipitated with monoclonal anti-Bak (Ab-1; Calbiochem) antibody and then immunoblotted with polyclonal anti-Bak antibody (Cell Signaling Technology). Five percent of the whole-cell lysate (40 µg of protein) was subjected to Western blot analysis and probed with polyclonal anti-Bak antibody (Cell Signaling Technology) served as loading control. Two additional experiments produced similar results. The active Bak level has been quantified and is shown in Supplemental Fig. 9. (E) LN18 and LNZ308 cells were treated with ABT-737 [2.0 µM (A) or BKM120 (2.0 µM (B), or a combination of both (2.0 µM each, A and B] for 24 hours. Control cells received an equivalent amount of DMSO (C). Membrane fractions were obtained as described under Materials and Methods, and proportional amounts corresponding to total protein were analyzed for Bax oligomerization by Western blotting under nonreducing conditions. Slow-moving Bax oligomers in DSP cross-linked cells were derived from Bax monomers, and the molecular masses of oligomers containing Bax were calculated by plotting their migrations against migrations of molecular mass standards. Two additional experiments produced similar results. The Bax homodimer (40-kDa fragment) level has been quantified by densitometry, and the results are shown in Supplemental Fig. 10. (F) LN18 cells were treated with ABT-737 (2.0 µM, A) or BKM120 (2.0 µM, B) or a combination of both (2.0 µM each, A and B) for 24 hours. Control cells received an equivalent amount of DMSO (C). Mitochondria-enriched membrane fractions were obtained as described under Materials and Methods and subjected to Western blot analysis as described under Materials and Methods with the indicated antibodies. Cox IV served as loading control. The results of three representative independent experiments are presented here; two additional experiments produced similar results. Protein levels have been quantified by densitometry, and the results are shown in Supplemental Fig. 11. (G) LN18 and LNZ308 cells were treated with indicated concentrations of ABT-737 or BKM120 or a combination of both for 24 hours as described in Fig. 5F. An equal amount of protein (500 µg) was immunoprecipitated with Mcl-1 antibody and subjected to Western blot analysis using the indicated antibodies. The results of three representative independent experiments are presented here; two additional experiments produced similar results. Protein levels have been quantified by densitometry, and the results are shown in Supplemental Fig.12.

ABT-737 and BKM120–Induced Apoptotic Cell Death Involves Alterations in the Conformation of Bax and Bak Proteins.

Bcl-2 family members Bax and Bak are crucial to the mitochondrial dysfunction-mediated apoptotic cell death pathways (Wei et al., 2001). To investigate Bax and Bak involvement, we used Bax (6A7, monoclonal Bax antibody; Sigma-Aldrich) and Bak antibodies (1-Ab, monoclonal Bak antibody; Calbiochem) that recognize the active conformations of the respective proteins. Immunoprecipitation followed by Western blot analysis was performed as described under Materials and Methods. As shown in Fig. 5C, treatment of LN18 (PTEN wild type) and LNZ308 (PTEN deleted) cell lines with BKM120 or ABT-737 for 36 hours induced little or no activation of Bax. However, the combination of BKM120 and ABT-737 for 12 hours induced an increased activation of Bax (Supplemental Fig. 8). Minimal Bak activation was evident in LN18 and LNZ308 glioma cell lines (Fig. 5D; Supplemental Fig. 9).

Homo-oligomerization of Bax (or Bak) has been hypothesized to be responsible for cell death through the mitochondria-dependent apoptosis pathway. The predominant view is that upon commitment to apoptosis, Bax and Bak undergo conformational changes, translocate into mitochondria, oligomerize, and form pores in the outer mitochondrial membrane that allow the release of proteins across the outer mitochondrial membrane (Korsmeyer et al., 2000; Martinou and Green 2001). To address the effects of ABT-737 and BKM120, we examined the Bax or Bak homo-oligomerization in glioma cell lines. Freshly prepared mitochondrial membrane fractions from untreated or treated cells were incubated with DSP, a membrane-permeable homo-bifunctional amine-reactive crosslinking agent. As shown in Fig. 5E, cotreatment with ABT-737 and BKM120 induces Bax oligomers in the mitochondrial membrane fraction (also see Supplemental Fig. 10). These results indicate that cotreatment with ABT-737 and BKM120- induced mitochondrial dysfunction–mediated apoptotic cell death in glioma cells that is mediated by the conformational changes and subsequent oligomerization of proapoptotic Bcl-2 family member Bax.

Bax oligomerization on mitochondria is known to require the presence of activated proapoptotic proteins such as Bim and/or Bid (i.e., tBid) on mitochondria (Tait and Green 2010). Indeed, we observed accumulation of Bim and tBid on mitochondria upon ABT-737 and BKM120 treatment (Fig. 5F; Supplemental Fig. 11). Because Bax involvement in apoptotic pathways was demonstrated to be associated with exposure of the N terminus in mitochondria (Goping et al., 1998), we used two antibodies that recognize distinct epitopes in the N terminus of Bax: a polyclonal antibody recognizing amino acids 150–165 (Calbiochem) and a monoclonal antibody recognizing amino acids 12–24 (BD Biosciences Pharmingen, San Diego, CA). As shown in Fig. 5F and Supplemental Fig. 11, cotreatment of ABT-737 and BKM120 was observed to trigger exposure of Bax N terminus epitopes in the mitochondrial fraction of LN18 cells. Together these findings suggest that cotreatment with ABT-737 and BKM120 induces Bim and tBid accumulation on mitochondria, contributing to the activation and oligomerization of Bax and Bak, and therefore, leading to mitochondrial membrane permeabilization and loss of mitochondrial membrane potential.

BKM120 and ABT-737 Disrupt the Mcl-1:Bak/Bim Association.

Our recent findings demonstrated that the silencing of Mcl-1 (either by pharmacologic or genetic means) overcame ABT-737 resistance, highlighting the role of Mcl-1 in the resistance to ABT-737 (Premkumar et al., 2012; Jane et al., 2013). To examine the effects of BKM120 and ABT-737 in glioma cell lines, and to determine the changes in the ability of Bak to bind Mcl-1, we performed immunoprecipitation of Mcl-1 protein from cells treated with ABT-737, BKM120, or the combination. BKM120 + ABT-37 significantly decreased Mcl-1/Bak association (Fig. 5G; Supplemental Fig. 12), suggesting that activation of Bak and dissociation from Mcl-1 may play a pivotal role in the marked induction of apoptosis in cells coexposed to BKM120 and ABT-737. Because Mcl-1 is also known to bind to Bim, and this interaction can block inhibition of Bax and Bak by Mcl-1 (Chen et al., 2005), we sought to determine whether ABT-737– and BKM120-induced apoptosis occurred in a Bim-dependent manner. We observed that Bim was efficiently released from Mcl-1 in LN18 (PTEN wild type) and LN308 (PTEN deleted) cell lines cotreated with ABT-737 and BKM120 (Fig. 5G; Supplemental Fig. 12), suggesting that the combination of ABT-737 and BKM120 may release Bim from Mcl-1. Together, these findings suggest that cotreatment with BKM120 and ABT-737 antagonizes interactions of Bak and Bim (proapoptotic proteins) with Mcl-1 (antiapoptotic protein) to promote the activation of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway.

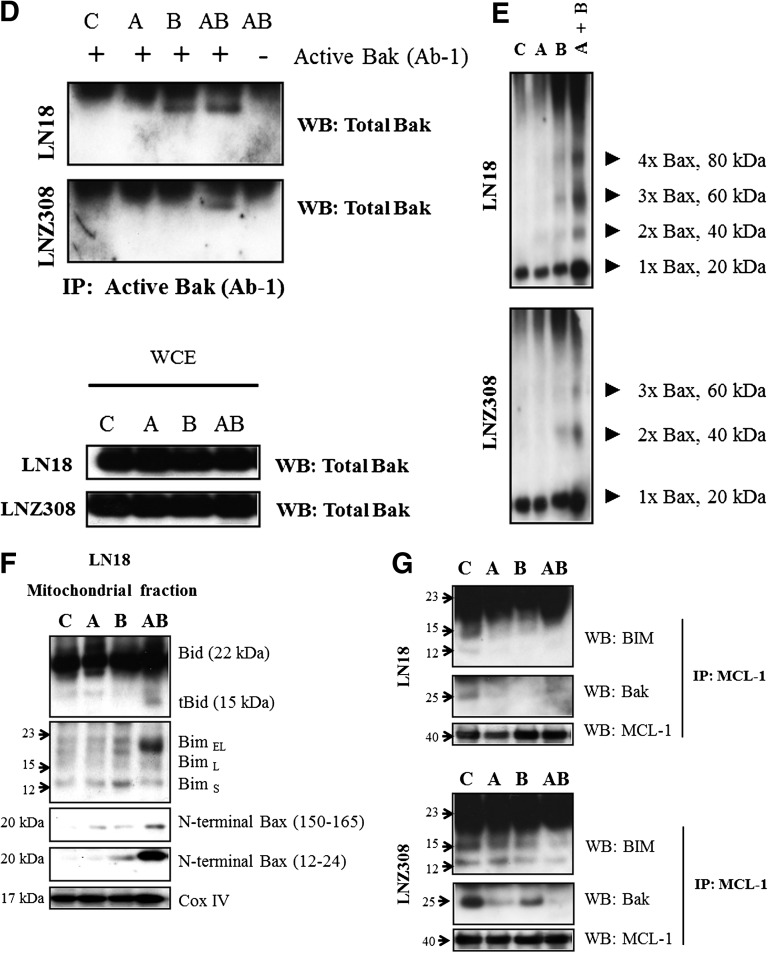

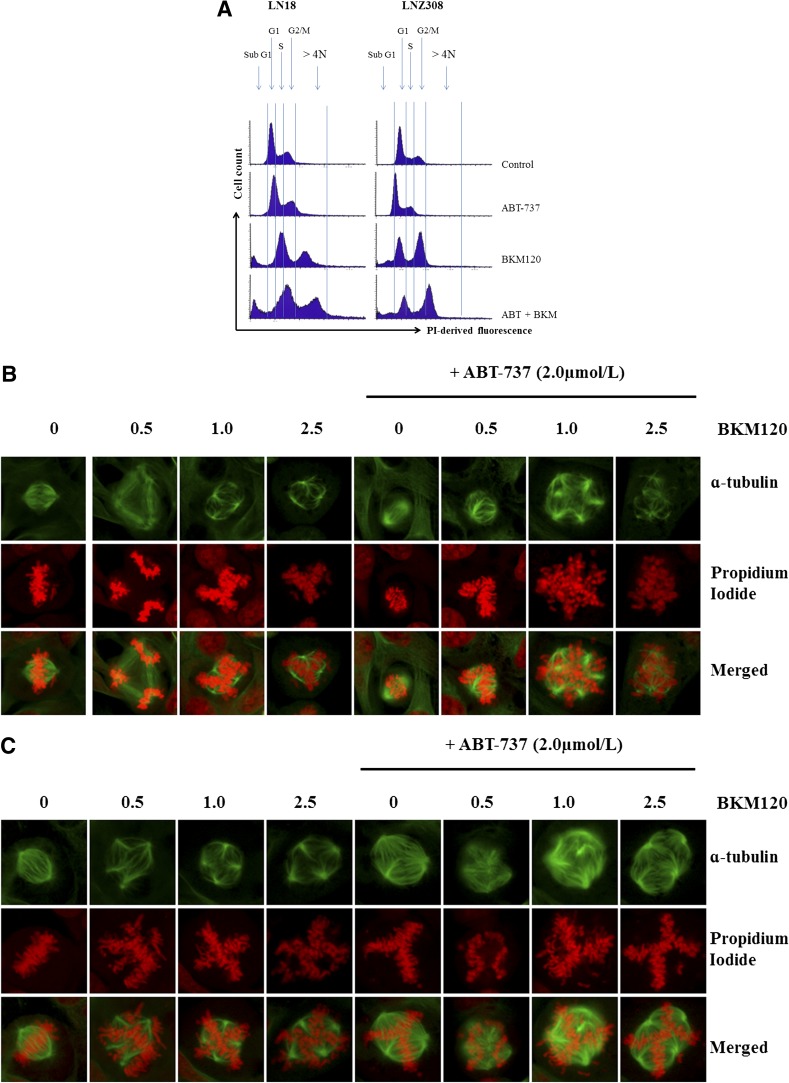

Cotreatment with ABT-737 and BKM120 Increases DNA Damage.

Cell cycle analysis demonstrates that BKM120 alone increased the percentage of cells at G2/M phase (Fig. 1C), which was correlated with the reduction of G1 cells; whereas ABT-737 exhibited no distinct change. More importantly, the combination of ABT-737 and BKM120 induced a profound cell death as indicated by the presence of sub-G1 DNA peak, and significantly increased the number of cells having >4 N DNA (polyploid) content (Fig. 6A), suggesting that ABT-737 might target the cell cycle checkpoint arrest induced by BKM120. Recently, BKM120 has been shown to induce mitotic catastrophe in glioma (Koul et al., 2012). In this study, we used fluorescence microscopy to investigate the effects of BKM120 and ABT-737 on chromosomal alignment and mitotic spindle defects. In comparison with the bipolar mitotic spindle formation and alignment of chromosomes on the metaphase plate in untreated cells, abnormalities were readily apparent in treated cells (Fig. 6, B–D). Where spindle pole separation had occurred, chromosomes appeared entangled and incorrectly aligned on the spindle equator, and the spindles themselves were asymmetric. We also noted that cotreatment with ABT-737 consistently increased the levels of spindle abnormalities (Fig. 6, B–D) and generation of multinucleated cells (propidium iodide staining). We then examined the potential of ABT-737 and BKM120 to induce H2AX expression, a canonical marker of DNA damage and double-strand breaks (Rogakou et al., 1998). The results showed that exposure of glioma cells to ABT-737 + BKM120 resulted in a significant increase of p-H2AX. Consistent with activation of pH2AX, Chk1 and Chk2 underwent phosphorylation at Ser317/Ser345 and Thr68, respectively (Fig. 6E; Supplemental Fig. 13). Chk1 activation was accompanied by a diminution of Cdc25A, cyclin A2, and CDK4 levels (data not shown). Caspase-3 cleavage was also observed (Fig. 6E), consistent with the increase in apoptosis noted with the annexin V/PI analysis. Taken together, these data indicate that cotreatment with ABT-737 and BKM120 significantly enhances DNA damage response and apoptosis.

Fig. 6.

Cotreatment of ABT-737 and BKM120 increases DNA damage. (A) LN18 and LNZ308 cells were seeded at 60% confluence, allowed to attach overnight, and treated with ABT-737 (2.0 µM), BKM120 (2.0 µM), or the combination of both (2.0 µM each) for 24 hours. Cell cycle analysis using propidium iodide staining was performed as described under Materials and Methods. The results of three representative independent experiments presented here; two additional experiments produced similar results. LN18 (B), LNZ308 (C), and GBM-4 (D) cells were exposed to indicated concentrations (µM) BKM120 (BKM) of ABT-737 (2.0 µM), or the combination of both for 24 hours. Cells were stained with α-tubulin–fluorescein isothiocyanate (1:50 dilution) as described under Materials and Methods. Nuclei were stained with propidium iodide. Control cells received DMSO (0). (E) LN18 and LNZ308 cells were treated with BKM120 (indicated concentration, µM) with or without ABT-737 (2.0 µM) for the indicated duration (h, hour). An equal amount of protein was subjected to Western blot analysis using the indicated antibodies. β-Actin served as the loading control. The results of three representative independent experiments are presented here; two additional experiments produced similar results. Protein levels have been quantified by densitometry, and the results are shown in Supplemental Fig. 13.

Discussion

Resistance to apoptosis is a major obstacle for most cancer therapeutics and can arise because of overexpression of apoptosis inhibitors. Since many signaling components are frequently affected in glioma, targeted therapies that inhibit multiple targets are required. ABT-737 is a promising agent being tested in clinical trials for solid tumors and lymphoid malignancies. One of the major limitations of ABT-737 reported in preclinical studies is that high levels of Mcl-1 confer resistance to ABT-737, suggesting the need for combined modality therapies (Konopleva et al., 2006; van Delft et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2007). Because glioma cells are relatively resistant to ABT-737, and Akt is a crucial mediator of apoptosis sensitivity in response to ABT-737 (Premkumar et al., 2012), we investigated pharmacologic interaction between the Bcl-2 inhibitor, ABT-737, and the PI3K/Akt inhibitor BKM120 in malignant human glioma cells. We found that BKM120, which itself has modest apoptotic activity, acts synergistically with ABT-737 to induce apoptosis (Figs. 2A and 3A). Although the absence of PTEN limited apoptotic activity of ABT-737 as a single agent (Premkumar et al., 2012), the combination of ABT-737 and BKM120 synergistically induced apoptosis independent of PTEN expression (LN18, PTEN wild type versus LNZ308, PTEN deleted glioma cell lines) in a caspase-dependent manner (Fig. 2B; Supplemental Fig. 2). When used as single agents in the same concentrations as in the combination therapies neither ABT-737 nor BKM120 was associated with any significant change in Δψm or induction of apoptosis. Of interest, the combination of drugs strongly induced mitochondrial membrane depolarization, as shown by flow cytometry with DiOC6 dye and subsequent potent induction of apoptosis as shown by Western blot and annexin V/PI analysis.

We (Premkumar et al., 2012; Jane et al., 2013), among others (Konopleva et al., 2006; van Delft et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2007), have shown that Mcl-1 and Noxa play crucial roles in determining ABT-737 sensitivity. Decreasing Mcl-1 levels with YM-155 (Jane et al., 2013) or increasing Noxa levels by bortezomib (Premkumar et al., 2012) resulted in synergistic effects with ABT-737 in malignant human glioma cell lines. Notably, the antiapoptotic protein Mcl-1 showed minimal or no reduction after treatment with BKM120 or cotreatment with ABT-737 (data not shown). However, in response to ABT-737 and BKM120, the proapoptotic activator Bim was displaced from its inhibitory associations with Mcl-1 (Fig. 5G; Supplemental Fig. 12). Based on the Western blot data presented here, there seems to be cooperation between ABT-737 and Noxa that serves to trigger apoptosis; Noxa accumulated after treatment with BKM120 (Fig. 5A; Supplemental Fig. 6). Noxa is a BH3-only protein capable of activating Bax and Bak, which then induce cytochrome c release; expression of this protein suggests the important role of Mcl-1 and Noxa interaction in ABT-737– and BKM120-induced apoptosis.

In this report, we also demonstrated that ABT-737 and BKM120 act together to promote the cleavage of Bid into tBid and enhance the accumulation of tBid at the mitochondrial membrane (Fig. 5F; Supplemental Fig. 11). This promotes the cross-talk between the extrinsic and intrinsic apoptosis pathways and initiates a mitochondrial amplification loop, resulting in increased Bax activation, loss of mitochondrial membrane potential, the release of cytochrome c and smac/DIABLO from mitochondria, and caspase-dependent apoptosis (Li et al., 1998; Lovell et al., 2008). In addition, ABT-737- and BKM120-induced cleavage of Bid into tBid was inhibited by a caspase-8 inhibitor, suggesting the involvement of the extrinsic apoptotic pathway as well (Fig. 5B; Supplemental Fig. 7). Thus, the combination ABT-737 and BKM120 simultaneously activates both the extrinsic and intrinsic apoptosis pathways and also enhances cross-talk between both pathways, resulting in synergistic induction of apoptosis. A critical role of tBid in the regulation of mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization has been shown in a recent study. Accordingly, tBid was reported to rapidly bind to mitochondrial membranes, where its BH3 domain facilitates the insertion of cytosolic Bax into the membrane, leading to activation and oligomerization of Bax and, subsequently, to membrane permeabilization (Lovell et al., 2008).

Bax and Bak activation or Bax conformational changes lead to the formation of a mitochondrial pore that facilitates the release of mitochondrial proapoptotic proteins. The mechanisms of this pharmacologic interaction involve synergistic mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization by the ABT-737 and BKM120 combination, as evidenced by effective conformational activation of Bax (Fig. 5C; Supplemental Fig. 8) and Bak (Fig. 5D; Supplemental Fig. 9) and Δψm loss (Fig. 4A). This is an additional and new observation that can account for these synergistic interactions of ABT-737 and BKM120. Because caspase-8–mediated cleavage of the BH3-only protein Bid to its active form, tBid, is required for the activation of Bax and Bak (Li et al., 1998), a role for the involvement of Bid in the multidomain proapoptotic proteins such as Bax and Bak in ABT-737– and BKM120-induced apoptosis can be assumed.

The morphologic changes of apoptosis include membrane blebbing, cell shrinkage, chromosome missegregation, microtubule misalignment, DNA fragmentation, and formation of apoptotic bodies. ABT-737– and BKM120-treated cells displayed chromatin condensation and alterations in the proper chromosome arrangement, as demonstrated by immunostaining. In agreement with Koul et al. (2012), accumulation of glioma cells in the G2/M phase of the cell cycle is among the earliest effects detected in response to BKM120 (Fig. 1C). We also observed the appearance of the sub-G1 population after ABT-737 and BKM120 treatment and the emergence of polyploid cells as revealed by the increase in cells with >4 N DNA content (Fig. 6A). In a recent study, we have shown that exposure to vorinostat and bortezomib promotes H2AX phosphorylation, which played an important role in the synergistic enhancement of DNA damage, double-strand break, and apoptosis (Premkumar et al., 2013a). In the data presented here, γH2AX, a marker of DNA damage (double-strand breaks), was elevated in the combination therapy compared with ABT-737 or BKM120 as single agents; this may be due to cells with abnormal or aborted mitosis, as evidenced by the high proportion of cells with >4 N DNA content. Additional investigations are needed to further define the molecular processes of ABT-737 plus BKM120–induced inhibition of DNA repair. Overall, our present findings establish that as a single agent, either BKM120 or ABT-737 displayed modest cytotoxic/cytostatic activity. Combination of ABT-737 and BKM120 potently inhibits cell growth and induces apoptosis regardless of PTEN status, suggesting a potential mechanistic rationale for these inhibitors in clinical application.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Robert Lacomy and Alexis Styche for FACS analysis and Qing Sun for statistical analysis.

Abbreviations

- ABT-737

N-{4-[4-(4-chloro-biphenyl-2-ylmethyl)-piperazin-1-yl]-benzoyl}-4-(3-dimethylamino-1-phenylsulfanylmethyl-propylamino)-3-nitro-benzenesulfonamide

- Bcl-2

B-cell lymphoma-2

- BH3

Bcl-2 homology 3

- CHAPS

3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonic acid

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- DSP

dithiobissuccinimidyl propionate

- E-64d

(2S,3S)-trans-epoxysuccinyl-L-leucylamido-3-methylbutane ethyl ester

- fmk

fluoromethyl ketone

- GBM

glioblastoma

- JNK

c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase

- MEM

minimal essential medium

- NVP-BKM120

5-(2,6-dimorpholinopyrimidin-4-yl)-4-(trifluoromethyl)pyridin-2-amine

- PARP

poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PI3K

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- PI

propidium iodide

- PTEN

phosphatase and tensin homolog

- tBid

truncated Bid

- z

N-benzyloxycarbony

- YM-155

3-(2-methoxyethyl)-2-methyl-4,9-dioxo-1-(pyrazin-2-ylmethyl)-4,9-dihydro-3H-naphtho[2,3-d]imidazol-1-ium bromide]

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Jane, Premkumar, Pollack.

Conducted experiments: Jane, Premkumar, Morales, Foster.

Performed data analysis: Jane, Premkumar, Morales, Foster, Pollack.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Premkumar, Foster, Pollack.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke [Grant P01-NS40923] (to I.F.P.); the Walter L. Copeland Fund of The Pittsburgh Foundation (to D.R.P. and K.A.F.); and Ian’s Friends Foundation (to I.F.P.).

This article has supplemental material available at jpet.aspetjournals.org.

This article has supplemental material available at jpet.aspetjournals.org.

References

- Bendell JC, Rodon J, Burris HA, de Jonge M, Verweij J, Birle D, Demanse D, De Buck SS, Ru QC, Peters M, et al. (2012) Phase I, dose-escalation study of BKM120, an oral pan-Class I PI3K inhibitor, in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol 30:282–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Certo M, Del Gaizo Moore V, Nishino M, Wei G, Korsmeyer S, Armstrong SA, Letai A. (2006) Mitochondria primed by death signals determine cellular addiction to antiapoptotic BCL-2 family members. Cancer Cell 9:351–365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Willis SN, Wei A, Smith BJ, Fletcher JI, Hinds MG, Colman PM, Day CL, Adams JM, Huang DC. (2005) Differential targeting of prosurvival Bcl-2 proteins by their BH3-only ligands allows complementary apoptotic function. Mol Cell 17:393–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Dai Y, Harada H, Dent P, Grant S. (2007) Mcl-1 down-regulation potentiates ABT-737 lethality by cooperatively inducing Bak activation and Bax translocation. Cancer Res 67:782–791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cristofanon S, Fulda S. (2012) ABT-737 promotes tBid mitochondrial accumulation to enhance TRAIL-induced apoptosis in glioblastoma cells. Cell Death Dis 3:e432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeAngelis LM. (2001) Brain tumors. N Engl J Med 344:114–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debien E, Hervouet E, Gautier F, Juin P, Vallette FM, Cartron PF. (2011) ABT-737 and/or folate reverse the PDGF-induced alterations in the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway in low-grade glioma patients. Clin Epigenetics 2:369–381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Gaizo Moore V, Brown JR, Certo M, Love TM, Novina CD, Letai A. (2007) Chronic lymphocytic leukemia requires BCL2 to sequester prodeath BIM, explaining sensitivity to BCL2 antagonist ABT-737. J Clin Invest 117:112–121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil-Parrado S, Fernández-Montalván A, Assfalg-Machleidt I, Popp O, Bestvater F, Holloschi A, Knoch TA, Auerswald EA, Welsh K, Reed JC, et al. (2002) Ionomycin-activated calpain triggers apoptosis. A probable role for Bcl-2 family members. J Biol Chem 277:27217–27226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goping IS, Gross A, Lavoie JN, Nguyen M, Jemmerson R, Roth K, Korsmeyer SJ, Shore GC. (1998) Regulated targeting of BAX to mitochondria. J Cell Biol 143:207–215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- High LM, Szymanska B, Wilczynska-Kalak U, Barber N, O’Brien R, Khaw SL, Vikstrom IB, Roberts AW, Lock RB. (2010) The Bcl-2 homology domain 3 mimetic ABT-737 targets the apoptotic machinery in acute lymphoblastic leukemia resulting in synergistic in vitro and in vivo interactions with established drugs. Mol Pharmacol 77:483–494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jane EP, Premkumar DR, DiDomenico JD, Hu B, Cheng SY, Pollack IF. (2013) YM-155 potentiates the effect of ABT-737 in malignant human glioma cells via survivin and Mcl-1 downregulation in an EGFR-dependent context. Mol Cancer Ther 12:326–338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jane EP, Premkumar DR, Pollack IF. (2006) Coadministration of sorafenib with rottlerin potently inhibits cell proliferation and migration in human malignant glioma cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 319:1070–1080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jane EP, Premkumar DR, Pollack IF. (2011) Bortezomib sensitizes malignant human glioma cells to TRAIL, mediated by inhibition of the NF-kappaB signaling pathway. Mol Cancer Ther 10:198–208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitchens CA, McDonald PR, Shun TY, Pollack IF, Lazo JS. (2011) Identification of chemosensitivity nodes for vinblastine through small interfering RNA high-throughput screens. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 339:851–858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konopleva M, Contractor R, Tsao T, Samudio I, Ruvolo PP, Kitada S, Deng X, Zhai D, Shi YX, Sneed T, et al. (2006) Mechanisms of apoptosis sensitivity and resistance to the BH3 mimetic ABT-737 in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Cell 10:375–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korsmeyer SJ, Wei MC, Saito M, Weiler S, Oh KJ, Schlesinger PH. (2000) Pro-apoptotic cascade activates BID, which oligomerizes BAK or BAX into pores that result in the release of cytochrome c. Cell Death Differ 7:1166–1173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koul D, Fu J, Shen R, LaFortune TA, Wang S, Tiao N, Kim YW, Liu JL, Ramnarian D, Yuan Y, et al. (2012) Antitumor activity of NVP-BKM120—a selective pan class I PI3 kinase inhibitor showed differential forms of cell death based on p53 status of glioma cells. Clin Cancer Res 18:184–195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Zhu H, Xu CJ, Yuan J. (1998) Cleavage of BID by caspase 8 mediates the mitochondrial damage in the Fas pathway of apoptosis. Cell 94:491–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovell JF, Billen LP, Bindner S, Shamas-Din A, Fradin C, Leber B, Andrews DW. (2008) Membrane binding by tBid initiates an ordered series of events culminating in membrane permeabilization by Bax. Cell 135:1074–1084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher EA, Furnari FB, Bachoo RM, Rowitch DH, Louis DN, Cavenee WK, DePinho RA. (2001) Malignant glioma: genetics and biology of a grave matter. Genes Dev 15:1311–1333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maira SM, Pecchi S, Huang A, Burger M, Knapp M, Sterker D, Schnell C, Guthy D, Nagel T, Wiesmann M, et al. (2012) Identification and characterization of NVP-BKM120, an orally available pan-class I PI3-kinase inhibitor. Mol Cancer Ther 11:317–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinou JC, Green DR. (2001) Breaking the mitochondrial barrier. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2:63–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nencioni A, Wille L, Dal Bello G, Boy D, Cirmena G, Wesselborg S, Belka C, Brossart P, Patrone F, Ballestrero A. (2005) Cooperative cytotoxicity of proteasome inhibitors and tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand in chemoresistant Bcl-2-overexpressing cells. Clin Cancer Res 11:4259–4265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oltersdorf T, Elmore SW, Shoemaker AR, Armstrong RC, Augeri DJ, Belli BA, Bruncko M, Deckwerth TL, Dinges J, Hajduk PJ, et al. (2005) An inhibitor of Bcl-2 family proteins induces regression of solid tumours. Nature 435:677–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollack IF. (1994) Brain tumors in children. N Engl J Med 331:1500–1507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Premkumar DR, Arnold B, Jane EP, Pollack IF. (2006a) Synergistic interaction between 17-AAG and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibition in human malignant glioma cells. Mol Carcinog 45:47–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Premkumar DR, Arnold B, Pollack IF. (2006b) Cooperative inhibitory effect of ZD1839 (Iressa) in combination with 17-AAG on glioma cell growth. Mol Carcinog 45:288–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Premkumar DR, Jane EP, Agostino NR, DiDomenico JD, Pollack IF. (2013a) Bortezomib-induced sensitization of malignant human glioma cells to vorinostat-induced apoptosis depends on reactive oxygen species production, mitochondrial dysfunction, Noxa upregulation, Mcl-1 cleavage, and DNA damage. Mol Carcinog 52:118–133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Premkumar DR, Jane EP, DiDomenico JD, Vukmer NA, Agostino NR, Pollack IF. (2012) ABT-737 synergizes with bortezomib to induce apoptosis, mediated by Bid cleavage, Bax activation, and mitochondrial dysfunction in an Akt-dependent context in malignant human glioma cell lines. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 341:859–872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Premkumar DR, Jane EP, Foster KA, Pollack IF. (2013b) Survivin inhibitor YM-155 sensitizes tumor necrosis factor- related apoptosis-inducing ligand-resistant glioma cells to apoptosis through Mcl-1 downregulation and by engaging the mitochondrial death pathway. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 346:201–210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Premkumar DR, Jane EP, Pollack IF. (2010) Co-administration of NVP-AEW541 and dasatinib induces mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis through Bax activation in malignant human glioma cell lines. Int J Oncol 37:633–643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian J, Zou Y, Rahman JS, Lu B, Massion PP. (2009) Synergy between phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway and Bcl-xL in the control of apoptosis in adenocarcinoma cells of the lung. Mol Cancer Ther 8:101–109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren H, Chen M, Yue P, Tao H, Owonikoko TK, Ramalingam SS, Khuri FR, Sun SY. (2012) The combination of RAD001 and NVP-BKM120 synergistically inhibits the growth of lung cancer in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Lett 325:139–146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogakou EP, Pilch DR, Orr AH, Ivanova VS, Bonner WM. (1998) DNA double-stranded breaks induce histone H2AX phosphorylation on serine 139. J Biol Chem 273:5858–5868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo M, Spagnuolo C, Volpe S, Tedesco I, Bilotto S, Russo GL. (2013) ABT-737 resistance in B-cells isolated from chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients and leukemia cell lines is overcome by the pleiotropic kinase inhibitor quercetin through Mcl-1 down-regulation. Biochem Pharmacol 85:927–936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmena L, Carracedo A, Pandolfi PP. (2008) Tenets of PTEN tumor suppression. Cell 133:403–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spender LC, Inman GJ. (2012) Phosphoinositide 3-kinase/AKT/mTORC1/2 signaling determines sensitivity of Burkitt’s lymphoma cells to BH3 mimetics. Mol Cancer Res 10:347–359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tagscherer KE, Fassl A, Campos B, Farhadi M, Kraemer A, Böck BC, Macher-Goeppinger S, Radlwimmer B, Wiestler OD, Herold-Mende C, et al. (2008) Apoptosis-based treatment of glioblastomas with ABT-737, a novel small molecule inhibitor of Bcl-2 family proteins. Oncogene 27:6646–6656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tait SW, Green DR. (2010) Mitochondria and cell death: outer membrane permeabilization and beyond. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 11:621–632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thaker NG, McDonald PR, Zhang F, Kitchens CA, Shun TY, Pollack IF, Lazo JS. (2010a) Designing, optimizing, and implementing high-throughput siRNA genomic screening with glioma cells for the discovery of survival genes and novel drug targets. J Neurosci Methods 185:204–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thaker NG, Zhang F, McDonald PR, Shun TY, Lazo JS, Pollack IF. (2010b) Functional genomic analysis of glioblastoma multiforme through short interfering RNA screening: a paradigm for therapeutic development. Neurosurg Focus 28:E4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thaker NG, Zhang F, McDonald PR, Shun TY, Lewen MD, Pollack IF, Lazo JS. (2009) Identification of survival genes in human glioblastoma cells by small interfering RNA screening. Mol Pharmacol 76:1246–1255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Delft MF, Wei AH, Mason KD, Vandenberg CJ, Chen L, Czabotar PE, Willis SN, Scott CL, Day CL, Cory S, et al. (2006) The BH3 mimetic ABT-737 targets selective Bcl-2 proteins and efficiently induces apoptosis via Bak/Bax if Mcl-1 is neutralized. Cancer Cell 10:389–399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogler M, Dinsdale D, Dyer MJ, Cohen GM. (2009) Bcl-2 inhibitors: small molecules with a big impact on cancer therapy. Cell Death Differ 16:360–367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogler M, Dinsdale D, Sun XM, Young KW, Butterworth M, Nicotera P, Dyer MJ, Cohen GM. (2008) A novel paradigm for rapid ABT-737-induced apoptosis involving outer mitochondrial membrane rupture in primary leukemia and lymphoma cells. Cell Death Differ 15:820–830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voss V, Senft C, Lang V, Ronellenfitsch MW, Steinbach JP, Seifert V, Kögel D. (2010) The pan-Bcl-2 inhibitor (-)-gossypol triggers autophagic cell death in malignant glioma. Mol Cancer Res 8:1002–1016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei MC, Zong WX, Cheng EH, Lindsten T, Panoutsakopoulou V, Ross AJ, Roth KA, MacGregor GR, Thompson CB, Korsmeyer SJ. (2001) Proapoptotic BAX and BAK: a requisite gateway to mitochondrial dysfunction and death. Science 292:727–730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen PY, Kesari S. (2008) Malignant gliomas in adults. N Engl J Med 359:492–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.