Significance

TPL-2 is a MEK-1/2 kinase that mediates Toll-like receptor activation of ERK-1/2 MAP kinases in macrophages and is critical for TNF induction during inflammation. TPL-2 activation of MEK-1/2 requires release from its associated inhibitor NF-κB1 p105, resulting from p105 proteolysis triggered by the IκB kinase (IKK) complex. Here, we show that IKK phosphorylation of the TPL-2 C terminus induces 14-3-3 association with TPL-2, stimulating its MEK kinase activity, which is essential for TPL-2 activation of ERK-1/2. The 14-3-3 binding to TPL-2 is also indispensible for its induction of TNF, which is regulated independently of ERK-1/2 activation. The IKK complex, a key regulator of NF-κB transcription factors, therefore directly controls two key steps for TPL-2 activation in inflammatory responses.

Keywords: inflammation, NF-κB, MAP3K8

Abstract

The MEK-1/2 kinase TPL-2 is critical for Toll-like receptor activation of the ERK-1/2 MAP kinase pathway during inflammatory responses, but it can transform cells following C-terminal truncation. IκB kinase (IKK) complex phosphorylation of the TPL-2 C terminus regulates full-length TPL-2 activation of ERK-1/2 by a mechanism that has remained obscure. Here, we show that TPL-2 Ser-400 phosphorylation by IKK and TPL-2 Ser-443 autophosphorylation cooperated to trigger TPL-2 association with 14-3-3. Recruitment of 14-3-3 to the phosphorylated C terminus stimulated TPL-2 MEK-1 kinase activity, which was essential for TPL-2 activation of ERK-1/2. The binding of 14-3-3 to TPL-2 was also indispensible for lipopolysaccharide-induced production of tumor necrosis factor by macrophages, which is regulated by TPL-2 independently of ERK-1/2 activation. Our data identify a key step in the activation of TPL-2 signaling and provide a mechanistic insight into how C-terminal deletion triggers the oncogenic potential of TPL-2 by rendering its kinase activity independent of 14-3-3 binding.

Cells of the innate immune system are rapidly activated following infection via stimulation of germ-line–encoded pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) that detect pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) (1). The Toll-like receptor (TLR) family of PRRs recognizes a wide range of PAMPs, including lipids, lipoproteins, proteins, and nucleic acids from bacteria, viruses, parasites, and fungi (2). TLRs trigger signaling pathways, leading to the activation of nuclear factor kappa light-chain enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) transcription factors, IFN-regulatory factors, and each of the major mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase subtypes [extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2 (ERK-1/2), c-Jun N-terminal kinases, and p38α/β]. Together, these signaling processes induce the expression of hundreds of proteins, which regulate multiple aspects of the innate immune response.

Activation of ERK-1/2 MAP kinases in macrophages by all TLRs is mediated by the MAP 3-kinase TPL-2 (tumor progression locus-2, also known as Cot and MAP3K8), which phosphorylates and activates the ERK-1/2 kinases, mitogen-activated ERK kinase-1 and -2 (MEK-1 and -2) (3, 4). TPL-2 regulates cytokine production by TLR-stimulated macrophages and dendritic cells, inducing production of tumor necrosis factor (TNF), interleukin (IL)-1β, and IL-10, while suppressing production of IL-12 and IFN-β (5–8). Although TPL-2 has complex effects on the production of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines by myeloid cells, experiments with Map3k8−/− mice indicate that the net effect of TPL-2 signaling in the innate immune system is to induce inflammation (3). For example, TPL-2 signaling promotes TNF-induced endotoxin shock (5), is required for the development of TNF-induced inflammatory bowel disease (9), and regulates the onset and severity of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, a model for multiple sclerosis (10). TPL-2 is consequently considered a potential drug target in certain autoimmune diseases (11).

In unstimulated cells, TPL-2 forms a stoichiometric complex with NF-κB1 p105, an NF-κB inhibitory protein and the precursor of the NF-κB p50 subunit (12, 13), and A20-binding inhibitor of NF-κB (ABIN)-2 (14). Interactions with both p105 and ABIN-2 are required to maintain TPL-2 protein stability (12, 15, 16). Binding to p105 also prevents access of TPL-2 to its substrates MEK-1/2. Consequently, LPS activation of TPL-2 MEK-1/2 kinase activity requires the release of TPL-2 from p105 (16, 17). This event is triggered by phosphorylation of p105 by the IκB kinase (IKK) complex, which induces p105 K48-linked ubiquitination and subsequent proteolysis by the proteasome (17, 18).

Although NF-κB1 p105 interaction prevents phosphorylation of MEK-1/2 by TPL-2, it does not inhibit TPL-2 catalytic activity (19, 20). LPS stimulation is still required for activation of ERK-1/2 by TPL-2 ectopically expressed in Nfkb1−/− macrophages, which express virtually undetectable amounts of endogenous TPL-2 (20). The signaling activity of TPL-2 is therefore regulated independently of its release from p105. This regulation involves the inducible phosphorylation of TPL-2 on serine 400 (S400) in its C-terminal tail (20). Mutation of this conserved residue to alanine blocks the ability of ectopically expressed TPL-2 to induce activation of ERK-1/2 in LPS-stimulated Nfkb1−/− macrophages. Thus, TPL-2 activation of the ERK-1/2 MAP kinase pathway requires TPL-2 phosphorylation on S400.

We have recently demonstrated that TPL-2 S400 phosphorylation is mediated by IKK2, a catalytic subunit of the IKK complex (21). However, it remained unclear how IKK2 phosphorylation of this residue controls TPL-2 signaling. In the present study, we show that S400 phosphorylation was critical for the association of 14-3-3 with the TPL-2 C terminus. Binding of 14-3-3 increased the efficiency of MEK-1 phosphorylation by TPL-2 in vitro and was essential for TPL-2 activation of the ERK-1/2 MAP kinase pathway in cells. Thus, the IKK complex, the principal regulator of NF-κB transcription factors, directly controls both of the key steps required for TPL-2 to phosphorylate MEK-1/2 and activate the ERK-1/2 MAP kinase pathway in inflammation.

Results

S400 Is Essential for TPL-2 Signaling in Macrophages.

We previously investigated the role of S400 in LPS activation of TPL-2 signaling in macrophages by retroviral overexpression of TPL-2 in Map3k8−/− macrophages (20). However, the molecular mechanism by which S400 phosphorylation regulated TPL-2 signaling remained unclear. To address this question, we first determined whether S400 was required for signaling by TPL-2 under physiological conditions by generating the Map3k8S400A/S400A mouse strain, which expressed mutant TPL-2S400A (Fig. S1). Immunoblot analysis of bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) generated from these mice demonstrated that the Map3k8S400A mutation did not affect steady-state levels of TPL-2, but completely blocked TPL-2–dependent activation of ERK-1/2 following LPS stimulation (Fig. 1A). LPS activation of p38α was fractionally reduced in Map3k8S400A/S400A macrophages compared with WT, as previously found with LPS-stimulated Map3k8−/− macrophages (7). To investigate the effect of S400A mutation on ERK-1/2 activation in vivo, mice were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with LPS (22). Intracellular staining clearly detected phospho–ERK-1/2 in WT peritoneal F480+ macrophages 10 min after LPS injection (Fig. 1B). In contrast, no phospho–ERK-1/2 signal was detected in Map3k8S400A/S400A macrophages, similar to Map3k8−/− macrophages (22), demonstrating that S400 was essential for TPL-2–dependent activation of ERK-1/2 in vivo.

Fig. 1.

Map3k8S400A mutation blocks LPS activation of ERK-1/2 in macrophages. (A) WT and Map3k8S400A/S400A BMDMs were stimulated with LPS for the indicated times. Lysates were immunoblotted. (B) WT and Map3k8S400A/S400A mice were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with LPS or PBS control. After 10 min, peritoneal cells were aspirated and stained for surface F4/80 and intracellular phospho–ERK-1/2 (P-ERK). Anti–P-ERK mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of F4/80+ cells was determined by flow cytometry (mean ± SEM; n = 6 mice per genotype). (C) Triplicate cultures of BMDMs were stimulated with LPS for the indicated times, and TNF levels in supernatants were assayed. (D) WT and Map3k8S400A/S400A mice were injected i.p. with LPS. After 1 h, mice were bled, and serum TNF levels were quantified (mean ± SEM; n = 8 mice per genotype). **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.

The Map3k8S400A mutation additionally blocked induction of ERK-1/2 phosphorylation in BMDMs by TNF, CpG (TLR9), Pam-3-Cys-4 (TLR2), poly-(I:C) (TLR3), flagellin (TLR5), and imiquimod (TLR7) (Fig. S2 A–E), which all induce ERK-1/2 activation via TPL-2 (7, 8, 22–24). However, activation of ERK-1/2 by phorbol ester, which does not require TPL-2 (5), was unaffected by Map3k8S400A mutation (Fig. S2F). Map3k8S400A mutation also fractionally reduced p38α phosphorylation after stimulation with TNF and CpG, consistent with earlier results suggesting that p38α activation by these stimuli was mediated in part by the NF-κB1 p105/TPL-2 pathway (22). Together, these data provided unequivocal genetic evidence that S400 is essential for TPL-2–dependent activation of ERK-1/2 in macrophages.

TPL-2 promotes the production of soluble TNF (sTNF) independently of IKK-induced release of TPL-2 from p105 and its ability to activate ERK-1/2 (22). Map3k8S400A/S400A BMDMs produced very low levels of sTNF after LPS stimulation, which was reduced by ∼90% compared with WT BMDMs (Fig. 1C). Furthermore, production of sTNF in vivo after i.p. LPS injection was substantially reduced in Map3k8S400A/S400A compared with WT controls (Fig. 1D). These results imply that Map3k8S400A mutation blocked TPL-2 phosphorylation of the unknown target protein(s) by which TPL-2 controls sTNF production.

TPL-2 S400 Does Not Regulate TPL-2 Release from NF-κB1 p105.

LPS activation of ERK-1/2 requires TPL-2 release from p105 to facilitate MEK-1/2 phosphorylation (17). To investigate whether Map3k8S400A mutation affected this step in TPL-2 activation, BMDM lysates were depleted of p105 and then immunoblotted for TPL-2. No p105-free TPL-2 was detected in unstimulated WT or Map3k8S400A/S400A cells (Fig. 2A). After 7.5 min of LPS stimulation, similar amounts of M1–TPL-2 and M30–TPL-2 [produced by alternative translational initiation on a second methionine at residue 30 (25)] were detected in the p105-depleted WT and Map3k8S400A/S400A lysates. These results demonstrated that Map3k8S400A mutation did not block TPL-2 activation of ERK-1/2 by preventing TPL-2 release from its inhibitor p105.

Fig. 2.

Map3k8S400A mutation does not affect LPS-induced release of TPL-2 from NF-κB1 p105 or TPL-2 intrinsic kinase activity. WT and Map3k8S400A/S400A (Map3k8S400A) BMDMs were stimulated with LPS. (A) Total and p105-depleted lysates were immunoblotted. (B) TPL-2 was immunoprecipitated and assayed for its ability to phosphorylate GST–MEK-1K207A in vitro. MEK-1 phosphorylation and TPL-2 levels were assayed by immunoblotting.

We next determined whether Map3k8S400A mutation inhibited the catalytic activity of TPL-2 by in vitro kinase assay. In WT BMDMs, LPS stimulation induced a marked increase in TPL-2 MEK-1 kinase activity (Fig. 2B). LPS induced the MEK-1 kinase activity of TPL-2S400A to a similar degree, although phosphorylation of endogenous MEK-1/2 was completely blocked in LPS-stimulated Map3k8S400A/S400A cells. These results showed that S400 is not required for TPL-2 catalytic activity in vitro, but is essential to couple TPL-2 to downstream signaling pathways in cells, consistent with an earlier study analyzing transfected TPL-2 in Jurkat T cells (26).

S400 Phosphorylation Is Required for TPL-2 Interaction with 14-3-3.

Because S400 was not required for TPL-2 intrinsic catalytic activity or release from p105, we hypothesized that S400 phosphorylation might promote TPL-2 interaction with a phospho-peptide binding protein. Scansite (27) was used to determine whether TPL-2 phospho-S400 corresponded to any known binding sites. This analysis revealed that the sequence around phospho-S400 (RCQpSLD, where pS represents phospho-serine) had similarity to a mode I 14-3-3 binding site (RSXpSXP) at low stringency (28). Consistent with this prediction, biolayer interferometry demonstrated that a synthetic TPL-2393–407 phosphopeptide corresponding to the sequence surrounding S400 bound to recombinant 14-3-3ζ with a Kd of 0.7 μM, whereas the corresponding nonphosphorylated peptide did not bind (Fig. 3A). This affinity was similar to those reported for 14-3-3 interaction with phospho-peptides containing consensus Raf 14-3-3 binding sites (28). Furthermore, pulldown experiments with GST–14-3-3γ demonstrated that TPL-2 could interact with 14-3-3 after LPS stimulation of WT primary macrophages (Fig. 3B). However, TPL-2S400A from LPS-stimulated Map3k8S400A/S400A cells did not bind to GST–14-3-3γ. LPS stimulation of WT macrophages also induced interaction of TPL-2 with GST–14-3-3ε, GST–14-3-3ζ, and GST–14-3-3η (Fig. S3A). Similarly, Myc–TPL-2 transiently expressed in IL-1R–293 cells interacted with GST–14-3-3γ after IL-1β stimulation, whereas Myc–TPL-2S400A did not (Fig. S3B). Furthermore, Flag–TPL-2 immunoprecipitated from transiently transfected IL-1R–293 cells associated with endogenous 14-3-3 after IL-1β stimulation, and this interaction was blocked by S400A mutation (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

S400 is required for TPL-2 interaction with 14-3-3. (A) Biolayer interferometry was used to measure the ability of TPL-2393–407 peptide nonphosphorylated (□) and phosphorylated on S400 (●) to displace 14-3-3ζ protein associated with biotinylated phospho-S621–cRaf peptide bound to a Streptavidin sensor chip. A Kd value of 0.7 μM for the phospho-S400 peptide was calculated. (B) GST–14-3-3γ pulldowns from lysates of BMDMs with or without LPS (15 min) were immunoblotted. (C) IL-1R–293 cells were transiently transfected with expression constructs encoding WT or S400A Flag–TPL-2 or empty vector (EV). Anti-Flag immunoprecipitates and cell lysates were immunoblotted. (D) BMDMs were preincubated with BI605906 IKK2 inhibitor or vehicle control for 1 h, before stimulation with LPS for 15 min. GST–14-3-3γ pulldowns from cells lysates were immunoblotted. (E and F) BMDMs of the indicated genotypes were stimulated with LPS or left unstimulated. GST–14-3-3γ pulldowns and total cell lysates were immunoblotted.

Phosphorylation of TPL-2 S400 is mediated by IKK2 (21), and 14-3-3 dimers bind to their client proteins via phosphorylated serine/threonine motifs (29). In accordance with this observation, pharmacological inhibition of IKK2 in macrophages blocked LPS-induced interaction of TPL-2 with GST–14-3-3γ (Fig. 3D). IKK2 phosphorylation of S400, therefore, was required for TPL-2 binding to GST–14-3-3γ, demonstrating why Map3k8S400A mutation ablated TPL-2 interaction with 14-3-3 in agonist-stimulated cells.

Analysis of Nfkb1SSAA/SSAA BMDMs, in which the IKK target serines on NF-κB1 p105 are mutated to alanine to prevent signal-induced p105 proteolysis, has demonstrated that TPL-2 catalytic activity induces the production of sTNF by macrophages independently of its release from p105 and activation of ERK-1/2 (22). Furthermore, TPL-2 can be phosphorylated on S400 while still associated with p105 (20). Because Map3k8S400A mutation inhibited LPS induction of sTNF by Nfkb1SSAA/SSAA BMDMs (Fig. S4A), in which LPS-induced release of TPL-2 from p105 is blocked (22), we speculated that TPL-2 could associate with 14-3-3 while still complexed with p105. Consistent with this hypothesis, LPS stimulation of Nfkb1SSAA/SSAA BMDMs promoted the interaction of GST–14-3-3γ with TPL-2, although at much lower levels than with LPS-stimulated WT cells, and also p105 (Fig. 3E). TPL-2 was not detected in GST–14-3-3γ pulldowns after immunodepletion of p105 from lysates of LPS-stimulated Nfkb1SSAA/SSAA BMDMs (Fig. S4B). Furthermore, GST–14-3-3γ did not bind to TPL-2S400A in lysates of LPS-stimulated Nfkb1SSAA/SSAA Map3k8S400A/S400A BMDMs (Fig. 3F). Therefore, TPL-2 could interact inefficiently with 14-3-3 while bound to p105, and this association was dependent on TPL-2 S400.

Together, these results indicate that IKK2 phosphorylation of S400 triggered binding of TPL-2–14-3-3, and this interaction could occur when TPL-2 was still associated with p105.

TPL-2 Interaction with 14-3-3 Regulates TPL-2 Activation of ERK-1/2.

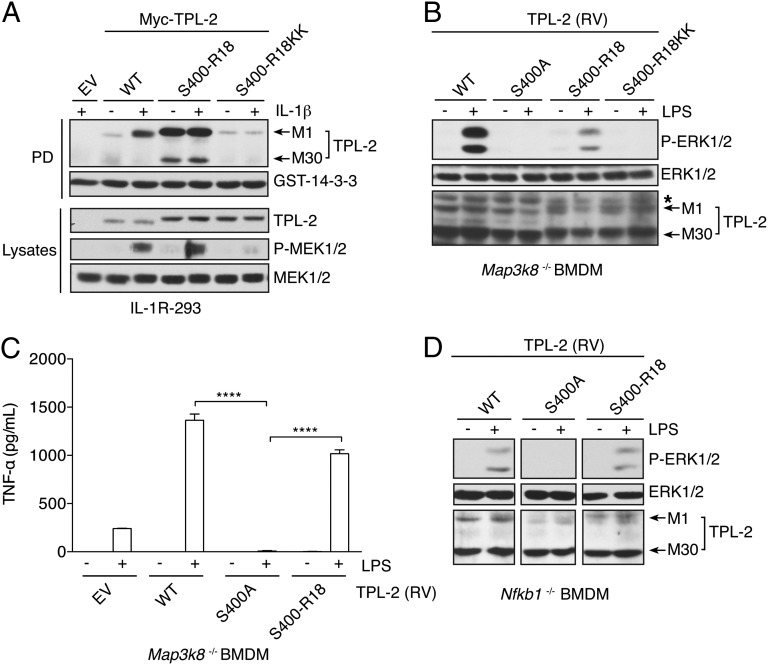

We next investigated whether the S400A mutation abrogated TPL-2 activation of ERK-1/2 by preventing recruitment of 14-3-3 dimers. To test this hypothesis, an expression construct was generated in which the TPL-2 S400 14-3-3 binding site was replaced with the R18 peptide motif that binds with high affinity to 14-3-3 proteins in a phosphorylation-independent fashion (30). In vitro kinase assays demonstrated that introduction of the R18 peptide into the S400 binding site did not alter the basal catalytic activity of TPL-2 (Fig. S5A). The resulting chimeric protein Myc–TPL-2S400–R18 was then transiently expressed in IL-1R–293 cells. As expected, Myc–TPL-2S400–R18 interacted constitutively with GST–14-3-3γ, whereas WT Myc–TPL-2 only bound after IL-1β stimulation (Fig. 4A). IL-1β induced the phosphorylation of endogenous MEK-1/2 in cells expressing Myc–TPL-2S400–R18, similar to WT Myc–TPL-2. In contrast, Myc–TPL-2S400–R18KK, in which two key negatively charged residues in the core binding motif of the R18 sequence were replaced with lysines, did not interact with GST–14-3-3γ or facilitate IL-1β activation of MEK-1/2, similar to Myc–TPL-2S400A (Fig. 4A and Fig. S3B). Binding of TPL-2S400–R18 to 14-3-3, therefore, replaced the requirement of S400 phosphorylation for TPL-2–mediated activation of ERK-1/2 in IL-1R–293 cells.

Fig. 4.

Reconstitution of TPL-2 signaling activity with 14-3-3–binding R18 motif. (A) IL-1R–293 cells, transiently transfected with empty vector (EV) or plasmids encoding Myc-tagged TPL-2, TPL-2S400A, and TPL-2S400–R18, were stimulated with IL-1β or left unstimulated. (B–D) GST–14-3-3γ pulldowns and lysates were immunoblotted. BMDMs generated from Map3k8−/− (B and C) or Nfkb1−/− (D) mice were transduced with retroviruses encoding the indicated TPL-2 proteins. In B and D, cells were stimulated with LPS for 15 min or left unstimulated, and lysates were immunoblotted. In C, cells were stimulated with LPS for 9 h, and sTNF in culture supernatants was assayed (mean ± SEM; n = 3). ****P < 0.0001.

To confirm the physiological significance of these data, TPL-2S400–R18 was expressed in Map3k8−/− BMDMs by retroviral transduction. As shown previously (20), WT TPL-2 rescued LPS induction of ERK-1/2 phosphorylation, whereas no ERK-1/2 phosphorylation was detected in cells expressing TPL-2S400A (Fig. 4B). Importantly, LPS stimulation clearly induced ERK-1/2 phosphorylation in cells transduced with TPL-2S400–R18, whereas expression of TPL-2S400–R18KK had no effect on LPS induction of ERK-1/2 phosphorylation. The level of ERK-1/2 phosphorylation was higher in LPS-stimulated Map3k8−/− cells expressing WT TPL-2 than TPL-2S400–R18, which may reflect in part the relative TPL-2 and TPL-2S400–R18 protein expression levels. Expression of TPL-2S400–R18 was also found to rescue LPS-induced sTNF production by Map3k8−/− BMDMs similar to WT TPL-2, whereas TPL-2S400 did not (Fig. 4C).

Together, these results suggested that S400 was essential for TPL-2 activation of ERK-1/2 due to its ability to mediate recruitment of 14-3-3 after IKK2-mediated phosphorylation. However, although constitutively bound to 14-3-3, agonist stimulation was nevertheless required for TPL-2S400–R18 activation of ERK-1/2 in both IL-1R–293 cells and Map3k8−/− BMDMs. Thus, 14-3-3 binding to the TPL-2 C terminus per se was insufficient to promote TPL-2–dependent activation of ERK-1/2. Because TPL-2S400–R18 was still able to interact with p105 (Fig. S5B), it was possible that this observation simply reflected a requirement for stimulus-induced release of TPL-2S400–R18 from p105. To investigate this possibility, TPL-2S400–R18 was expressed in Nfkb1−/− BMDMs, which lack endogenous p105 expression. Similar to Map3k8−/− BMDMs, LPS stimulation was required for TPL-2S400–R18 to induce ERK-1/2 phosphorylation in Nfkb1−/− BMDMs (Fig. 4D). Therefore, activation of ERK-1/2 was still dependent on agonist stimulation when TPL-2S400–R18 was constitutively bound to 14-3-3 and free from p105-mediated inhibition.

S443 Is Required for Optimal TPL-2 Interaction with 14-3-3.

The 14-3-3 dimers contain two independent ligand-binding sites, and consequently can interact simultaneously with two phosphopeptide-binding motifs, found either on single or separate client proteins (31). In addition to S400, Scansite analysis of the TPL-2 amino acid sequence identified S62 (RSKpSLLL), T80 (RYGpTVED), and S443 (R/KRQRpSLY) as potential phospho-peptide binding sites for 14-3-3. Biolayer interferometry confirmed that synthetic TPL-2 phosphopeptides corresponding to S62 and S443 both bound to 14-3-3ζ (Fig. 5A and Fig. S6A), although with slightly lower affinities than that for TPL-2 S400 phosphopeptide. No binding was detected with the T80 TPL-2 phosphopeptide. These results raised the possibility that phospho-S62 or -S443 might function cooperatively with phospho-S400 to mediate TPL-2 interaction with 14-3-3 dimers. We had previously shown that TPL-2 S62A mutation does not affect TPL-2 activation of ERK-1/2 in macrophages (21). Furthermore, TPL-2S62A, expressed in IL-1R–293 cells, was still able to interact with GST–14-3-3γ and mediate MEK-1/2 activation after IL-1β stimulation (Fig. S6B). Consequently, phosphorylation of S62 was not required for TPL-2–dependent activation of ERK-1/2, and further experiments focused on determining the role of S443 in TPL-2 signaling.

Fig. 5.

The 14-3-3 interaction with phospho-S443 is required for optimal TPL-2 signaling. (A) Binding between 14-3-3ζ and a synthetic phospho-S443–TPL-2436–450 peptide as in Fig. 3A. A Kd value of 1.9 ± 0.4 μM was calculated. (B) IL-1R–293 cells, transiently transfected with plasmids encoding WT, S400A, or S443 AMyc–TPL-2, were stimulated with IL-1β or left unstimulated. Anti-Myc immunoprecipitates and cell lysates were immunoblotted. (C) IL-1R–293 cells expressing Myc–TPL-2 were pretreated with C34 (TPL-2 inhibitor), BI605906 (IKK2 inhibitor), or vehicle control and then stimulated with IL-1β or left unstimulated. Anti-Myc immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted. (D) IL-1R–293 cells expressing Myc–TPL-2 or kinase-inactive Myc–TPL-2D270A were stimulated with IL-1β or left unstimulated. Anti-Myc immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted. (E) IL-1R–293 cells transiently expressing the indicated Myc–TPL-2 proteins were stimulated with IL-1β or left unstimulated. GST–14-3-3γ pulldowns and lysates were immunoblotted. (F) Map3k8−/− BMDMs, transduced with retroviruses encoding the indicated TPL-2 proteins, were stimulated with LPS (15 min) or left unstimulated. Lysates were immunoblotted.

Immunoblotting with a TPL-2 phospho-S443 antibody revealed that IL-1β stimulation induced the phosphorylation of S443 on Myc–TPL-2 expressed in IL-1R–293 cells (Fig. 5B). Analysis of Myc–TPL-2S400A and Myc–TPL-2S443A mutants demonstrated that TPL-2 S400 and S443 could be phosphorylated independently of one another. Pharmacological inhibition of TPL-2 catalytic activity with C34 small-molecule inhibitor (32) blocked TPL-2 S443 phosphorylation, whereas phosphorylation on TPL-2 S443 was largely unaffected by inhibition of IKK2 with BI605906 (Fig. 5C). These data suggested that IL-1β stimulation induced the autophosphorylation of TPL-2 on S443. Accordingly, IL-1β stimulation did not induce S443 phosphorylation of catalytically inactive TPL-2D270A (Fig. 5D). However, because it was not possible to detect in vitro S443 phosphorylation by using affinity-purified TPL-2, it cannot formally be ruled out that TPL-2 S443 phosphorylation was mediated by a downstream kinase activated by TPL-2 catalytic activity.

S443A mutation reduced the interaction of Myc–TPL-2 with GST–14-3-3γ induced by IL-1β stimulation (Fig. 5E), similar to S400A mutation (Fig. 3C). Consistent with the requirement for TPL-2 to interact with 14-3-3 to activate the ERK-1/2 MAP kinase pathway, IL-1β induction of MEK-1/2 phosphorylation was substantially reduced by the TPL-2 S443A mutation (Fig. 5D). Furthermore, S443A mutation prevented TPL-2 rescuing LPS induction of ERK-1/2 following retroviral transduction of Map3k8−/− BMDMs (Fig. 5F).

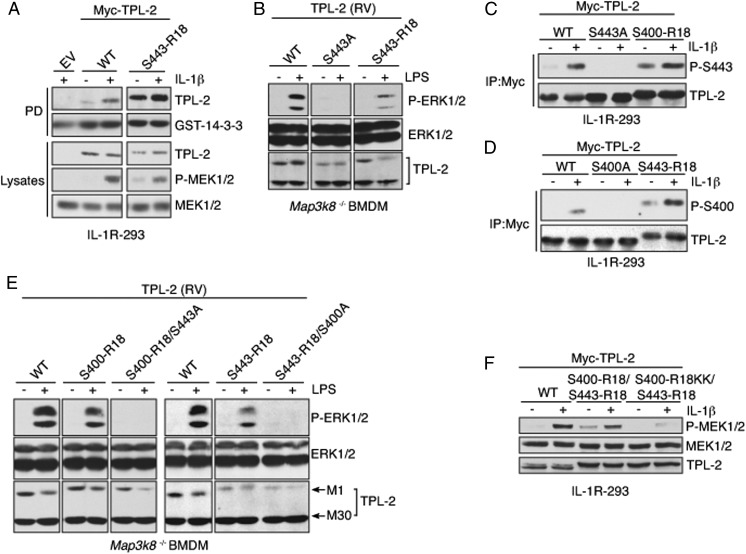

To determine whether 14-3-3 binding to phospho-S443 was sufficient to promote TPL-2 signaling, the S443 14-3-3 binding site in TPL-2 was replaced with the R18 motif. Introduction of the R18 peptide into the S443 binding site did not alter the basal catalytic activity of TPL-2 (Fig. S5A), but did abrogate its ability to interact with p105 (Fig. S5B). TPL-2S443–R18 was able to bind to 14-3-3 constitutively, but mediated activation of MEK-1/2 in IL-1R–293 cells only after IL-1β stimulation (Fig. 6A). LPS stimulation was also required to induce ERK-1/2 phosphorylation in Map3k8−/− BMDMs expressing TPL-2S443–R18 (Fig. 6B). Thus, introduction of the R18 motif into the S443 14-3-3 binding site removed the need for S443 phosphorylation, but not agonist stimulation, for TPL-2 signaling. However, TPL-2S443–R18 did not signal as efficiently as WT TPL-2 in either IL-1R–293 cells or Map3k8−/− BMDMs.

Fig. 6.

Optimal TPL-2 signaling requires 14-3-3 interaction with both phospho-S400 and -S443. (A) IL-1R–293 cells expressing the indicated Myc–TPL-2 constructs or empty vector (EV) were stimulated with IL-1β or left unstimulated. GST–14-3-3γ pulldowns and lysates were immunoblotted. (B and E) Map3k8−/− BMDMs, transduced with retroviruses encoding the indicated TPL-2 proteins, were stimulated with LPS for 15 min or left unstimulated. Lysates were immunoblotted. (C and D) WT and mutant forms of Myc–TPL-2 were immunoprecipitated from lysates of IL-1R–293 cells with or without IL-1β stimulation, and immunoblotted. (F) IL-1R–293 cells expressing the indicated Myc–TPL-2 constructs were stimulated with IL-1β or left unstimulated. Lysates were immunoblotted.

Both TPL-2S400–R18 and TPL-2S443–R18 chimeric proteins were able to constitutively bind to 14-3-3, but still required IL-1β stimulation to mediate activation of MEK-1/2 in IL-1R–293 cells and LPS stimulation of ERK-1/2 in Map3k8−/− BMDMs. These results suggested that 14-3-3 binding constitutively to phospho-S400 or to phospho-S443 was not sufficient to fully activate TPL-2. Immunoblotting with phospho-S443 antibody revealed that IL-1β stimulation induced S443 phosphorylation on TPL-2S400–R18 (Fig. 6C) and S400 phosphorylation on TPL-2S443–R18 (Fig. 6D). Because 14-3-3 dimers are able to bind separately to two phosphopeptide motifs, these findings implied that a 14-3-3 dimer bound simultaneously to phospho-S400 and -S443 to promote TPL-2 signaling. Consistent with this possibility, TPL-2S400–R18/S443A and TPL-2S443–R18/S400A, although constitutively bound to 14-3-3, failed to mediate LPS activation of ERK-1/2 when expressed in Map3k8−/− BMDMs, in contrast to TPL-2S400–R18 and TPL-2S443–R18, respectively (Fig. 6E). Together, these results indicated that TPL-2 must be phosphorylated on both S400 and S443 to efficiently recruit 14-3-3 dimers and trigger activation of ERK-1/2 MAP kinases.

To investigate whether 14-3-3 binding to both phospho-S400 and -S443 was sufficient to fully activate TPL-2 signaling, we generated a TPL-2 chimera in which the R18 peptide was inserted into both S400 and S443 sites. Expression of this chimera in IL-1R–293 cells slightly increased basal phospho–MEK-1/2 levels, and this increase was further augmented by IL-1β stimulation (Fig. 6F). Introduction of two positively charged residues in the S400–R18 sequence to disrupt 14-3-3 binding to this site blocked both basal and IL-1β–induced MEK-1/2 phosphorylation. These results indicated that 14-3-3 must bind simultaneously to both S400 and S443 sites to promote TPL-2 signaling. However, maximal activation of MEK-1/2 by TPL-2S400R18/S443R18 still required IL-1β stimulation, suggesting the existence of an additional 14-3-3–independent activating step.

Binding of 14-3-3 Does Not Promote TPL-2 Dimerization.

A key step in the activation of the MEK kinase B-Raf involves its heterodimerization with Raf-1 (33, 34). This interaction is dependent on 14-3-3 binding, which stabilizes the active conformation of B-Raf (35). Earlier studies have suggested that TPL-2 can also dimerize (36). Because 14-3-3 bound to two phosphorylated residues within the TPL-2 C terminus, it was not clear whether TPL-2 dimerization could be mediated via 14-3-3 dimers. To investigate this question, Flag–TPL-2 and V5–TPL-2 were coexpressed in IL-1R–293 cells. Immunoblotting of anti-Flag immunoprecipitates demonstrated that Flag–TPL-2 and V5–TPL-2 heterodimerize (Fig. S7A). This association was not affected either by IL-1β stimulation (to promote TPL-2 S400/S443 phosphorylation and association with 14-3-3) or S400A mutation (to block TPL-2/14-3-3 interaction), indicating that TPL-2 dimerization was independent of 14-3-3 interaction. Pulldowns with GST–MEK-1 also demonstrated that S400A mutation did not affect binding of TPL-2 to MEK-1 (Fig. S7B), which is required for efficient MEK-1/2 phosphorylation by TPL-2 (12). The 14-3-3 interaction, therefore, did not facilitate TPL-2 activation of MEK-1/2 by promoting TPL-2 binding to MEK-1 or itself.

Binding of 14-3-3 Enhances TPL-2 Catalytic Activity.

Truncation of the C terminus activates the oncogenic potential of TPL-2, which correlates with an increase in TPL-2–specific kinase activity (37). Furthermore, the free C terminus can bind in trans to the TPL-2 kinase domain, reducing its catalytic activity toward several model substrates. These data suggest that TPL-2 catalytic activity might be negatively regulated by an intramolecular interaction involving its C terminus. The 14-3-3 dimers are rigid structures and can induce conformational changes in protein ligands (29). This characteristic raised the possibility that 14-3-3 binding might alter the interaction between the kinase domain and C terminus of TPL-2, thereby increasing TPL-2 catalytic activity.

To investigate this possibility, we tested effect of recombinant 14-3-3 protein on the ability of TPL-2 to phosphorylate MEK-1 in vitro. The addition of 14-3-3ζ to immunoprecipitates of Flag–TPL-2 from IL-1β–stimulated IL-1R–293 cells increased phosphorylation of GST–MEK-1 by approximately fivefold (Fig. 7A). GST–MEK phosphorylation was further enhanced by coexpression of Flag–TPL-2 with IKK2, which increased both S400 and S443 phosphorylation in combination with IL-1β stimulation. In contrast, the addition of 14-3-3ζ had no detectable effect on the MEK-1 kinase activity of Flag–TPL-2S400A, isolated from IL-1β–stimulated cells coexpressing IKK2. Consistent with these data, the addition of recombinant 14-3-3ζ to TPL-2 immunoprecipitated from LPS-stimulated WT primary macrophages increased the phosphorylation of GST–MEK-1 (approximately threefold), whereas 14-3-3ζ had no effect on the MEK kinase activity of immunoprecipitated TPL-2S400A (Fig. 7B). Together, these results indicated that 14-3-3 binding to the phosphorylated C terminus augmented TPL-2 catalytic activity toward MEK-1.

Fig. 7.

TPL-2 MEK kinase activity is enhanced by 14-3-3. (A) IL-1R–293 cells, transiently coexpressing Flag–TPL-2 or Flag–TPL-2S400A and HA–IKK2, were stimulated with IL-1β. Immunoprecipitated Flag–TPL-2 was assayed for its ability to phosphorylate GST–MEK-1K207A (KA) with or without recombinant 14-3-3ζ protein. (B) Endogenous TPL-2 was immunoprecipitated from lysates of BMDMs with or without LPS (15 min) and assayed for its ability to phosphorylate GST–MEK-1K207A (KA) with or without recombinant 14-3-3ζ protein. (C) IL-1R–293 cells were transfected with the indicated amounts of HA–MEK-1 plasmid together with a fixed quantity of Myc–TPL-2 plasmid. Lysates, prepared with or without IL-1β stimulation, were immunoblotted.

TPL-2S400A mutation completely blocked the phosphorylation of endogenous MEK-1/2 in LPS-stimulated macrophages (Fig. 1B). In contrast, immunoprecipitated TPL-2S400A phosphorylated GST–MEK-1 to a similar degree to WT TPL-2, although only the latter was activated by 14-3-3 binding (Figs. 2A and 7B). For in vitro kinase assays, the concentration of GST–MEK-1 was near to the Km of TPL-2 for MEK-1 (38). Endogenous MEK-1 is likely present in much lower concentration in cells, suggesting that phospho-S400 recruitment of 14-3-3 might only be essential for TPL-2 signaling activity at low concentrations of MEK-1/2 substrate. To investigate this possibility, the ability of Myc–TPL-2S400A to phosphorylate overexpressed HA–MEK-1 was tested in IL-1R–293 cells. In contrast to endogenous MEK-1/2 (Fig. 3C), Myc–TPL-2S400A was still able to phosphorylate overexpressed HA–MEK-1 after IL-1β stimulation, although not to the same degree as WT Myc–TPL-2 (Fig. 7C). The binding of 14-3-3 to TPL-2, therefore, was not essential for phosphorylation of MEK-1 when the latter protein was expressed at supraphysiological levels.

Together, these data indicate that binding of 14-3-3 dimers to the TPL-2 C terminus increases the efficiency of TPL-2 substrate phosphorylation, which is essential for TPL-2 phosphorylation of MEK-1/2 at the limiting concentrations present in cells.

Discussion

Previous studies established that TPL-2 activation of MEK-1/2 in TLR-stimulated macrophages requires its release from its associated inhibitor NF-κB1 p105, which is triggered by IKK2-induced proteolysis of p105 by the proteasome (17, 18, 22). Here, we demonstrate that IKK2 controls a second critical step in TPL-2 activation of the ERK-1/2 MAP kinase pathway by directly phosphorylating the TPL-2 C terminus (21). IKK2 phosphorylation of S400, together with autophosphorylation on S443, triggers recruitment of 14-3-3 dimers to the TPL-2 C terminus. This interaction facilitates TPL-2 phosphorylation of MEK-1/2, possibly by relieving the inhibitory interaction between the TPL-2 C terminus and kinase domain (37).

By replacing the sequence surrounding S400 with R18 motif to generate TPL-2S400–R18, it was possible to demonstrate that TPL-2 activation can occur in the absence of S400 phosphorylation, provided that 14-3-3 binding to the C terminus was maintained. Importantly, TPL-2S400–R18KK, which could not interact with 14-3-3, was not able to activate ERK-1/2 after agonist stimulation, ruling out signaling due to structural alterations in the C terminus caused by insertion of the R18 sequence. Similarly, inserting the R18 peptide sequence in to the sequence surrounding S443 allowed TPL-2 to interact with 14-3-3 and to activate ERK-1/2 in the absence of S443 phosphorylation. These data suggest that S400 and S443 do not have alternative functions in TPL-2 signaling other than the recruitment of 14-3-3 dimers. The level of ERK-1/2 activation in cells expressing TPL-2S400–R18 or TPL-2S443–R18 was always lower than WT TPL-2, suggesting that the R18 peptide did not fully recapitulate the effects of the phosphorylated S400 and S443 14-3-3 binding sites. This observation may be due to differences in the way that 14-3-3 bound to the R18 motif compared with the phospho-S400 or -S443 peptides or because the spacing between 14-3-3 and the kinase domain is slightly compromised in the R18 fusions compared with the WT molecule. Similarly, replacement of the S621 14-3-3 binding site in Raf-1 with R18 peptide only partially rescues Raf-1 signaling activity (39).

S443 resides within the kinase regulatory domain of the TPL-2 C terminus (40), suggesting that binding of 14-3-3 to this region might alleviate its regulatory activity. However, agonist stimulation was required for TPL-2S443–R18 to induce MEK-1/2 and ERK-1/2 activation, indicating that 14-3-3 binding to the kinase regulatory domain was insufficient to activate TPL-2 signaling. The agonist-inducible phosphorylation of S400 in the TPL-2S443–R18 chimera, together with the failure of TPL-2S443–R18/S400A to activate MEK-1/2 following IL-1β stimulation, indicates that 14-3-3 dimers must bind to both pS400 and pS443 to promote TPL-2 signaling. In line with this suggestion, S443 was inducibly phosphorylated on TPL-2S400–R18, and TPL-2S400–R18/S443A was unable to activate MEK-1/2 after IL-1β stimulation. It therefore appears that 14-3-3 dimers must bind to the TPL-2 C terminus in a specific orientation to activate TPL-2 signaling to ERK-1/2. Interestingly, TPL-2 S443 autophosphorylation in IL-1R–293 cells, which was independent of IKK2 and S400 phosphorylation, required IL-1β stimulation. Thus, an additional, as yet uncharacterized, agonist-induced regulatory step triggers TPL-2 S443 autophosphorylation. Furthermore, IL-1β stimulation was required for maximal activation of MEK-1/2 by TPL-2S400R18/S443R18, suggesting that agonist stimulation controls TPL-2 signaling independently of S443 phosphorylation and 14-3-3 binding to the C terminus of TPL-2.

TPL-2 can induce sTNF production by LPS-stimulated macrophages independently of its IKK-induced release from p105 and ERK-1/2 activation (22). Map3k8S400A mutation blocked LPS induction of TNF by BMDMs and prevented the interaction of p105-associated TPL-2 with GST–14-3-3. Furthermore, expression of TPL-2S400–R18 rescued sTNF production by LPS-stimulated Map3k8−/− BMDMs. These data indicate that phosphorylation of the unknown target protein(s) by which p105-associated TPL-2 controls sTNF production is dependent on 14-3-3 interaction with the TPL-2 C terminus. Map3k8S400A mutation also blocked ERK-1/2 activation in macrophages by all tested TLR agonists and TNF. Activation of NF-κB in Jurkat T cells by overexpressed TPL-2 is also blocked by S400A mutation (26). The 14-3-3 binding appears to be required for TPL-2 to activate all downstream signaling pathways.

Activation of the oncogenic potential of TPL-2 requires deletion of its C terminus (37, 41). Our work suggests that one of the major effects of C-terminal deletion is to disrupt the normal regulatory mechanisms that control TPL-2 signaling activity. The recruitment of 14-3-3 dimers to the phosphorylated C terminus of WT TPL-2, which increases its specific activity for MEK-1, is essential for TPL-2 activation of ERK-1/2 in cells. Removal of the C terminus renders TPL-2 kinase activity independent of a requirement for 14-3-3 binding and also disrupts the negative regulatory effects of p105 on TPL-2 MEK kinase activity (12). Consequently, C-terminal truncation of TPL-2 results in uncontrolled phosphorylation of downstream substrates, promoting cell transformation.

In conclusion, our study supports a model in which the catalytic activity of TPL-2 is inhibited in nonstimulated cells by the interaction of the TPL-2 C terminus with the kinase domain. TLR stimulation induces IKK phosphorylation of TPL-2 S400 and TPL-2 S443 autophosphorylation, which triggers the recruitment of 14-3-3 to the TPL-2 C terminus. The 14-3-3 binding increases TPL-2–specific activity for MEK-1, possibly by altering the interaction of the C terminus with the TPL-2 kinase domain (37), which is essential for TPL-2 activation of ERK-1/2 in cells. TPL-2 activation of MEK-1/2 also requires its release from NF-κB1 p105 inhibition, which results from IKK-induced p105 proteolysis by the proteasome (17, 18). The IKK complex therefore directly controls two key steps in the activation of TPL-2 by TLRs, highlighting the close linkage between ERK-1/2 MAP kinase and NF-κB activation in inflammation.

Materials and Methods

Mouse Strains.

Mouse strains were bred in the specific pathogen-free animal facility of the National Institute for Medical Research (London). Seven- to 12-week-old mice were used for all experiments, which were performed in accordance with the United Kingdom Home Office regulations. Nfkb1−/− (42) and Map3k8−/− (5) mouse strains have been described. The generation of Map3k8S400A/S400A mice is detailed in SI Materials and Methods. All mouse strains were fully back-crossed onto a C57BL/6 background.

Reagents.

Myc-TPL-2, Flag-TPL-2D270A, and Flag-TPL-2 subcloned in pCDNA3 vector have been described (12, 43). Expression constructs encoding Flag and V5 epitope-tagged versions of WT and mutant TPL-2 and StepII-p105 were generated by PCR, using a Phusion polymerase kit (Finnzyme). All plasmids were verified by DNA sequencing.

Antibodies to TPL-2 (M20 and H-7) and ERK-1/2 were obtained from Santa Cruz. Antibody to activated phospho(T185/Y187)-ERK-1/2 (P-ERK) was obtained from Biosource. Antibodies against p38, phospho(T180/Y182)-p38 (P-p38), phospho–MEK-1/2, Flag, and 14-3-3 were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. Phospho-S400 TPL-2 antibody has been described (20). To generate the phospho-S443–TPL-2 antibody, a peptide was synthesized to correspond to residues 437–449 of murine TPL-2 in which S443 was phosphorylated. This phosphopeptide was coupled to keyhole limpet hemocyanin and injected into rabbits. An unphosphorylated form of the immunizing peptide (10 μg/mL) was incubated with phospho-S443 antibody during immunoblotting to minimize recognition of unphosphorylated TPL-2.

GST–14-3-3γ was expressed at 30 °C in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) and purified by affinity chromatography on glutathione–Sepharose 4B (Amersham Biosciences). Protein purity was estimated to be >90% by Coomassie brilliant blue (Novex) staining after SDS/PAGE. Recombinant His–14-3-3ζ was produced as described (44).

LPS (Salmonella enterica serovar Minnesota R595) was purchased from Alexis Biochemicals. CpG ODN 1668, Pam3Cys4, Imiquimod, and Flagellin were obtained from Invivogen. Recombinant mouse TNF and human IL-1β were from Peprotec. Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate was bought from Sigma. Inhibitors BI605906 (45) and C34 (32) were provided by the MRC Protein Phosphorylation Unit (University of Dundee, Scotland).

In Vitro Generation of Macrophages.

BMDMs were prepared as described (17, 46). More than 95% of the resulting BMDM cell populations were F4/80+CD11b+. Before stimulation, cells were cultured overnight in medium containing reduced FBS (1%) and no l-cell conditioned medium.

Retrovirus Infection of Macrophages.

Amphoteric recombinant retroviruses were produced as described (17). For retroviral infection, Map3k8−/− or Nfkb1−/− BM cells were plated in complete BMDM medium [RPMI medium 1640 (Sigma) supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) heat-inactivated FBS, 20% (vol/vol) l-cell conditioned medium, 2 mM glutamine, nonessential amino acids, antibiotics, 10 mM Hepes, and 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol] at 1 × 106 cells per well of six-well plate (2 mL of culture volume; Sarstedt). Following 4 d of culture, 200 μL of virus containing supernatant was added per well, and plates were centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 1 h. Cells were cultured for 3 h, 4 mL of complete BMDM medium was then added, and cells were recultured for a further 4 d. Cells harvested at this time were >95% F4/80+. For experiments, cells were replated at 1 × 106 cells per well (2 mL of culture volume) of a six-well plate (Nunc) in RPMI medium plus 1% FBS and lacking l-cell conditioned medium.

The 293 Cell Culture and Transfection.

HEK-293 cells stably expressing the IL-1R (C6 cells) were provided by Xiaoxia Li (Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Cleveland) (47). C6 cells were transiently transfected by using Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies). After overnight culture in complete medium [Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) FCS and 10 mM Hepes], cells were serum-starved for 24 h before stimulation with recombinant IL-1β (Peprotech; 20 ng/mL) for 20 min.

Protein Analyses.

Cells were washed once in cold PBS before lysis. For immunoblotting, cells were lysed in buffer A [50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 50 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4, 100 nM okadaic acid (Calbiochem), 2 mM Na4P2O7, and 5 mM Na β-glycerophosphate plus protease inhibitors (Roche Molecular Biochemicals)] containing 1% Nonidet-P40, 0.5% deoxycholate, and 0.1% SDS. After centrifugation, lysates were mixed with an equal volume of 2x SDS/PAGE sample buffer. For immunoprecipitations, lysis was carried out by using buffer B [50 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 20 mM NaF, and 1 mM Na4P2O7 plus a mixture of protease inhibitors (Roche Molecular Biochemicals)] containing 0.5% Nonidet-P40. Covalent coupling of antibodies to protein A-Sepharose (Amersham Biosciences) and immunoprecipitation were performed as described (48). To detect release of TPL-2 from p105, BMDM lysates were precleared of p105 by anti-p105 immunodepletion before immunoblotting (17).

For pulldown assays, cells were lysed in buffer B plus 0.5% Nonidet P-40. Recombinant GST, GST–14-3-3γ, or GST–MEK-1 (Millipore) proteins were mixed with lysates plus 10 µL of packed glutathione–Sepharose 4B beads (Amersham Biosciences) and incubated for 4h at 4 °C. Beads were then washed in lysis buffer B. Steptactin–Sepharose (Amersham Biosciences) was used for pulldowns of StepII–p105. Isolated proteins were eluted from beads with 2x SDS/PAGE sample buffer and analyzed by immunoblotting.

TPL-2 MEK Kinase Assays.

BMDMs or IL-1R–293 cells were cultured for 18 h in 1% or 0% serum, respectively. Cells were stimulated by 100 ng/mL LPS for 15 min (BMDMs) or 20 ng/mL hIL-1β for 20 min (IL-1R–293 cells) or left unstimulated and lysed by using kinase assay lysis buffer (buffer A containing 0.5% Nonidet P-40 and 1 mM DTT). Endogenous TPL-2 was immunoprecipitated from BMDM lysates by using a 1:1 mixture of 70-mer (17) and M20 (Santa Cruz) TPL-2 antisera coupled to protein A Sepharose. Flag mAb affinity gel (Sigma) was used to immunoprecipitate transfected Flag–TPL-2. Immunoprecipitates were washed four times in kinase assay lysis buffer and twice in kinase buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM β-glycerophosphate, 100 nM okadaic acid, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mM sodium vanadate, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, and 0.03% Brij 35). Beads were then resuspended in 50 μL of kinase buffer plus 1 mM ATP and 0.5 μM kinase-inactive GST–MEK-1D208A protein (MRC Protein Phosphorylation Unit, Dundee University) or GST–MEK-1K207A (49). After 30 min at 30 °C, reactions were terminated by the addition of EDTA. Phosphorylation of GST–MEK-1D208A and GST–MEK-1K207A were assessed by immunoblotting using phospho–MEK-1 mAb (Cell Signaling).

TNF Assay.

Concentrations of TNF in culture supernatants and sera were determined by using commercial ELISA kits (eBioscience).

In Vivo Analysis of ERK-1/2 Activation.

In vivo analysis of ERK-1/2 phosphorylation in macrophages was performed as described (22).

Biolayer Interferometry.

Binding of 14-3-3 to peptides was measured on an Octet RED biolayer interferometer (Pall ForteBio Corp.). Biotinylated phospho-S621 Raf peptide (at 1.5 μg/mL) was immobilized on streptavidin biosensors (Pall ForteBio Corp.). These sensors were then exposed to different concentrations of 14-3-3ζ (0.05–5 μM), and the response was recorded at the end of a 10-min association step. All measurements were made at 25 °C in 10 mM sodium phosphate, 150 mM NaCl, 0.002% Tween 20, 0.005% sodium azide, and 0.1 mg/mL BSA. The dependence of the response on the 14-3-3 ζ concentration was analyzed by using the standard nonlinear least-squares methods to calculate the Kd for phospho-S621 Raf peptide binding (1:1 binding model).

Equilibrium dissociation constants for the nonbiotinylated TPL-2 peptides were determined by using competition assays in which phospho-S621 Raf peptide-loaded sensors were exposed to a solution of 14-3-3ζ (at 1 μM) containing different concentrations of the competing peptide (0.05–80 μM). Standard nonlinear least-squares methods were used to calculate the Kd for the competing peptide with the Kd for phospho-S621 Raf peptide binding (0.49 ± 0.08 μM) fixed in the analysis (Fig. S6C).

Statistical Analysis.

In vitro data were compared by using the Student t test (two-tailed and unpaired test). For in vivo experiments, all statistical comparisons were carried out by using the nonparametric two-tailed Mann–Whitney test. Statistically significant differences are indicated on the figures.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Institute for Medical Research (NIMR) Photographics department, NIMR Biological Services, NIMR flow cytometry service, Caroline Morris (NIMR), John Offer (NIMR), Emilie Jacque (NIMR), and members of the Ley laboratory for help during the course of this work. We also thank Victor Tybulewicz (NIMR) and Peter Parker (Cancer Research UK, London) for helpful comments on the manuscript. This study was supported by UK Medical Research Council Grant U117584209, Arthritis Research UK Grant 18864 and Leukaemia Research Fund Grant 06050.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1320440111/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Janeway CA, Jr, Medzhitov R. Innate immune recognition. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:197–216. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.083001.084359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kawai T, Akira S. The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: Update on Toll-like receptors. Nat Immunol. 2010;11(5):373–384. doi: 10.1038/ni.1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gantke T, Sriskantharajah S, Sadowski M, Ley SC. IκB kinase regulation of the TPL-2/ERK MAPK pathway. Immunol Rev. 2012;246(1):168–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2012.01104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salmeron A, et al. Activation of MEK-1 and SEK-1 by Tpl-2 proto-oncoprotein, a novel MAP kinase kinase kinase. EMBO J. 1996;15(4):817–826. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dumitru CD, et al. TNF-α induction by LPS is regulated posttranscriptionally via a Tpl2/ERK-dependent pathway. Cell. 2000;103(7):1071–1083. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00210-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eliopoulos AG, Dumitru CD, Wang C-C, Cho J, Tsichlis PN. Induction of COX-2 by LPS in macrophages is regulated by Tpl2-dependent CREB activation signals. EMBO J. 2002;21(18):4831–4840. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaiser F, et al. TPL-2 negatively regulates interferon-beta production in macrophages and myeloid dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2009;206(9):1863–1871. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mielke LA, et al. Tumor progression locus 2 (Map3k8) is critical for host defense against Listeria monocytogenes and IL-1 beta production. J Immunol. 2009;183(12):7984–7993. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kontoyiannis D, et al. Genetic dissection of the cellular pathways and signaling mechanisms in modeled tumor necrosis factor-induced Crohn’s-like inflammatory bowel disease. J Exp Med. 2002;196(12):1563–1574. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sriskantharajah S, et al. Regulation of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by TPL-2. J Immunol. 2014;192(8):3518–3529. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.George D, Salmeron A. Cot/Tpl-2 protein kinase as a target for the treatment of inflammatory disease. Curr Top Med Chem. 2009;9(7):611–622. doi: 10.2174/156802609789007345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beinke S, et al. NF-kappaB1 p105 negatively regulates TPL-2 MEK kinase activity. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23(14):4739–4752. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.14.4739-4752.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Belich MP, Salmerón A, Johnston LH, Ley SC. TPL-2 kinase regulates the proteolysis of the NF-kappaB-inhibitory protein NF-kappaB1 p105. Nature. 1999;397(6717):363–368. doi: 10.1038/16946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lang V, et al. ABIN-2 forms a ternary complex with TPL-2 and NF-κ B1 p105 and is essential for TPL-2 protein stability. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24(12):5235–5248. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.12.5235-5248.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Papoutsopoulou S, et al. ABIN-2 is required for optimal activation of Erk MAP kinase in innate immune responses. Nat Immunol. 2006;7(6):606–615. doi: 10.1038/ni1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Waterfield MR, Zhang M, Norman LP, Sun S-C. NF-kappaB1/p105 regulates lipopolysaccharide-stimulated MAP kinase signaling by governing the stability and function of the Tpl2 kinase. Mol Cell. 2003;11(3):685–694. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beinke S, Robinson MJ, Hugunin M, Ley SC. Lipopolysaccharide activation of the TPL-2/MEK/extracellular signal-regulated kinase mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade is regulated by IkappaB kinase-induced proteolysis of NF-kappaB1 p105. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24(21):9658–9667. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.21.9658-9667.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Waterfield M, Jin W, Reiley W, Zhang MY, Sun S-C. IkappaB kinase is an essential component of the Tpl2 signaling pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24(13):6040–6048. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.13.6040-6048.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Babu GR, et al. Phosphorylation of NF-kappaB1/p105 by oncoprotein kinase Tpl2: Implications for a novel mechanism of Tpl2 regulation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1763(2):174–181. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2005.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robinson MJ, Beinke S, Kouroumalis A, Tsichlis PN, Ley SC. Phosphorylation of TPL-2 on serine 400 is essential for lipopolysaccharide activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase in macrophages. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27(21):7355–7364. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00301-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roget K, et al. IκB kinase 2 regulates TPL-2 activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2 by direct phosphorylation of TPL-2 serine 400. Mol Cell Biol. 2012;32(22):4684–4690. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01065-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang HT, et al. Coordinate regulation of TPL-2 and NF-κB signaling in macrophages by NF-κB1 p105. Mol Cell Biol. 2012;32(17):3438–3451. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00564-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Banerjee A, et al. NF-kappaB1 and c-Rel cooperate to promote the survival of TLR4-activated B cells by neutralizing Bim via distinct mechanisms. Blood. 2008;112(13):5063–5073. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-120832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eliopoulos AG, Wang C-C, Dumitru CD, Tsichlis PN. Tpl2 transduces CD40 and TNF signals that activate ERK and regulates IgE induction by CD40. EMBO J. 2003;22(15):3855–3864. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aoki M, et al. The human cot proto-oncogene encodes two protein serine/threonine kinases with different transforming activities by alternative initiation of translation. J Biol Chem. 1993;268(30):22723–22732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kane LP, Mollenauer MN, Xu Z, Turck CW, Weiss A. Akt-dependent phosphorylation specifically regulates Cot induction of NF-κ B-dependent transcription. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22(16):5962–5974. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.16.5962-5974.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Obenauer JC, Cantley LC, Yaffe MB. Scansite 2.0: Proteome-wide prediction of cell signaling interactions using short sequence motifs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31(13):3635–3641. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yaffe MB, et al. The structural basis for 14-3-3:phosphopeptide binding specificity. Cell. 1997;91(7):961–971. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80487-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morrison DK. The 14-3-3 proteins: Integrators of diverse signaling cues that impact cell fate and cancer development. Trends Cell Biol. 2009;19(1):16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang B, et al. Isolation of high-affinity peptide antagonists of 14-3-3 proteins by phage display. Biochemistry. 1999;38(38):12499–12504. doi: 10.1021/bi991353h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gardino AK, Smerdon SJ, Yaffe MB. Structural determinants of 14-3-3 binding specificities and regulation of subcellular localization of 14-3-3-ligand complexes: A comparison of the X-ray crystal structures of all human 14-3-3 isoforms. Semin Cancer Biol. 2006;16(3):173–182. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu J, et al. Selective inhibitors of tumor progression loci-2 (Tpl2) kinase with potent inhibition of TNF-alpha production in human whole blood. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2009;19(13):3485–3488. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rajakulendran T, Sahmi M, Lefrançois M, Sicheri F, Therrien M. A dimerization-dependent mechanism drives RAF catalytic activation. Nature. 2009;461(7263):542–545. doi: 10.1038/nature08314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garnett MJ, Rana S, Paterson H, Barford D, Marais R. Wild-type and mutant B-RAF activate C-RAF through distinct mechanisms involving heterodimerization. Mol Cell. 2005;20(6):963–969. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rushworth LK, Hindley AD, O’Neill E, Kolch W. Regulation and role of Raf-1/B-Raf heterodimerization. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26(6):2262–2272. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.6.2262-2272.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cho J, Tsichlis PN. Phosphorylation at Thr-290 regulates Tpl2 binding to NF-kappaB1/p105 and Tpl2 activation and degradation by lipopolysaccharide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(7):2350–2355. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409856102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ceci JD, et al. Tpl-2 is an oncogenic kinase that is activated by carboxy-terminal truncation. Genes Dev. 1997;11(6):688–700. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.6.688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jia Y, et al. Purification and kinetic characterization of recombinant human mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase COT and the complexes with its cellular partner NF-κ B1 p105. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2005;441(1):64–74. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2005.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Light Y, Paterson H, Marais R. 14-3-3 antagonizes Ras-mediated Raf-1 recruitment to the plasma membrane to maintain signaling fidelity. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22(14):4984–4996. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.14.4984-4996.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gándara ML, López P, Hernando R, Castaño JG, Alemany S. The COOH-terminal domain of wild-type Cot regulates its stability and kinase specific activity. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23(20):7377–7390. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.20.7377-7390.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Patriotis C, Makris A, Bear SE, Tsichlis PN. Tumor progression locus 2 (Tpl-2) encodes a protein kinase involved in the progression of rodent T-cell lymphomas and in T-cell activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90(6):2251–2255. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.6.2251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sha WC, Liou HC, Tuomanen EI, Baltimore D. Targeted disruption of the p50 subunit of NF-κ B leads to multifocal defects in immune responses. Cell. 1995;80(2):321–330. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90415-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gantke T, et al. Ebola virus VP35 induces high-level production of recombinant TPL-2-ABIN-2-NF-κB1 p105 complex in co-transfected HEK-293 cells. Biochem J. 2013;452(2):359–365. doi: 10.1042/BJ20121873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kostelecky B, Saurin AT, Purkiss A, Parker PJ, McDonald NQ. Recognition of an intra-chain tandem 14-3-3 binding site within PKCepsilon. EMBO Rep. 2009;10(9):983–989. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Clark K, et al. Novel cross-talk within the IKK family controls innate immunity. Biochem J. 2011;434(1):93–104. doi: 10.1042/BJ20101701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Warren MK, Vogel SN. Bone marrow-derived macrophages: Development and regulation of differentiation markers by colony-stimulating factor and interferons. J Immunol. 1985;134(2):982–989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li X, Commane M, Jiang Z, Stark GR. IL-1-induced NFkappa B and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) activation diverge at IL-1 receptor-associated kinase (IRAK) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(8):4461–4465. doi: 10.1073/pnas.071054198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kabouridis PS, Magee AI, Ley SC. S-acylation of LCK protein tyrosine kinase is essential for its signalling function in T lymphocytes. EMBO J. 1997;16(16):4983–4998. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.16.4983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marais R, et al. Requirement of Ras-GTP-Raf complexes for activation of Raf-1 by protein kinase C. Science. 1998;280(5360):109–112. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5360.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.