Abstract

The discipline taxonomy (the science of naming and classifying organisms, the original bioinformatics and a basis for all biology) is fundamentally important in ensuring the quality of life of future human generation on the earth; yet over the past few decades, the teaching and research funding in taxonomy have declined because of its classical way of practice which lead the discipline many a times to a subject of opinion, and this ultimately gave birth to several problems and challenges, and therefore the taxonomist became an endangered race in the era of genomics. Now taxonomy suddenly became fashionable again due to revolutionary approaches in taxonomy called DNA barcoding (a novel technology to provide rapid, accurate, and automated species identifications using short orthologous DNA sequences). In DNA barcoding, complete data set can be obtained from a single specimen irrespective to morphological or life stage characters. The core idea of DNA barcoding is based on the fact that the highly conserved stretches of DNA, either coding or non coding regions, vary at very minor degree during the evolution within the species. Sequences suggested to be useful in DNA barcoding include cytoplasmic mitochondrial DNA (e.g. cox1) and chloroplast DNA (e.g. rbcL, trnL-F, matK, ndhF, and atpB rbcL), and nuclear DNA (ITS, and house keeping genes e.g. gapdh). The plant DNA barcoding is now transitioning the epitome of species identification; and thus, ultimately helping in the molecularization of taxonomy, a need of the hour. The ‘DNA barcodes’ show promise in providing a practical, standardized, species-level identification tool that can be used for biodiversity assessment, life history and ecological studies, forensic analysis, and many more.

Keywords: DNA barcoding, Molecular markers, Species identification, Plant taxonomy, Biodiversity, Conservation genetics

1. Introduction

There are approximately 1.7 million species identified by using morphological (i.e. Linnean) characters including 808 gymnosperm, and 90,000 monocots and about 200,000 dicots of angiosperm. This number may be a gross under-estimate of the true biological diversity of Earth (Blaxter, 2003; Wilson, 2003). Recently, overwhelming landmark publications (Table 1) on DNA barcoding (Hebert et al., 2003) (syn.: profiling, genotyping) based on highly conserved sequence informations provide new tools for systematics (Hebert and Barrett, 2005) and phylogeny (Wyman et al., 2004; Leebens-Mack et al., 2005; Jansen et al., 2006; Hansen et al., 2006). DNA barcodes consist of short sequences of DNA between 400 and 800 base pairs that can be routinely amplified by PCR (polymerase chain reaction) and sequenced of the species studied.

Table 1.

Some landmark articles related to DNA barcoding published onward 2003.

| Year | Article | References |

|---|---|---|

| 2003 | Taxonomy, DNA, and the bar code of life | Stoeckle (2003) |

| Biological identifications through DNA barcodes | Hebert et al. (2003) | |

| A plea for DNA taxonomy | Tautz et al. (2003) | |

| 2004 | Now is the time | Janzen (2004) |

| DNA barcoding: promise and pitfalls | Moritz and Cicero (2004) | |

| Identification of birds through DNA barcodes | Hebert et al. (2004) | |

| Myth of the molecule: DNA barcodes for species cannot replace morphology for identification and classification | Will and Rubinoff (2004) | |

| 2005 | Genome sequencing in microfabricated high density picolitre reactors | Margulies et al. (2005) |

| Toward writing the encyclopedia of life: an introduction to DNA barcoding | Savolainen et al. (2005) | |

| DNA barcodes for Biosecurity: invasive species identification | Armstrong and Ball (2005) | |

| DNA barcoding does not compete with taxonomy | Gregory (2005) | |

| Will DNA bar codes breathe life into classification? | Marshall (2005) | |

| The promise of DNA barcoding for taxonomy | Hebert and Gregory (2005) | |

| DNA barcoding is no substitute for taxonomy | Ebach and Holdrege (2005) | |

| The perils of DNA barcoding and the need for integrative taxonomy | Will et al. (2005) | |

| Emerging technologies in DNA sequencing | Metzker (2005) | |

| Critical factors for assembling a high volume of DNA barcodes | Hajibabaei et al. (2005) | |

| DNA barcoding: Error rates based on comprehensive sampling | Meyer and Paulay (2005) | |

| Nextgeneration DNA sequencing techniques | Ansorge (2009) | |

| 2006 | Who will actually use DNA barcoding and what will it cost? | Cameron et al. (2006) |

| A minimalist barcode can identify a specimen whose DNA is degraded | Hajibabaei et al. (2006) | |

| 2007 | Limited performance of DNA barcoding in a diverse community of tropical butterflies | Elias et al. (2007) |

| A proposal for a standardized protocol to barcode all land plants | Chase et al. (2007) | |

| 2008 | The impact of next-generation sequencing technology on genetics | Mardis (2008) |

| A universal DNA mini-barcode for biodiversity analysis | Meusnier et al. (2008) | |

| DNA barcoding: how it complements taxonomy, molecular phylogenetics and population genetics | Hajibabaei et al. (2008) | |

| DNA barcodes: genes, genomics, and bioinformatics | Kress and Erickson (2008) | |

| 2009 | Evaluation of next generation sequencing platforms for population targeted sequencing studies | Harismendy et al. (2009) |

| DNA barcoding for ecologists | Valentini et al. (2009) | |

| 2010 | DNA barcoding: a six-question tour to improve users’ awareness about the method | Casiraghi et al. (2010) |

| A survey of sequence alignment algorithms for next-generation sequencing. Briefings in bioinformatics | Li and Homer (2010) | |

| 2011 | Pyrosequencing for mini-barcoding of fresh and old museum specimens | Shokralla et al. (2011) |

| Use of rbcL and trnL-F as a Two-Locus DNA Barcode for Identification of NWEuropean Ferns: An Ecological Perspective | De Groot et al. (2011) | |

| Environmental barcoding: a next-generation sequencing approach for biomonitoring applications using river benthos | Hajibabaei et al. (2011) | |

| On the future of genomic data | Kahn (2011) | |

| 2012 | An emergent science on the brink of irrelevance: a review of the past 9 years of DNA barcoding | Taylor and Harris (2012) |

| Next-generation sequencing technologies for environmental DNA research | Shokralla et al. (2012) | |

| Environmental DNA | Taberlet et al. (2012a) | |

| Toward next-generation biodiversity assessment using DNA metabarcoding | Taberlet et al. (2012c) | |

| The golden age of metasystematics | Hajibabaei (2012) | |

| A bloody boon for conservation | Callaway (2012) | |

| The future of environmental DNA in ecology | Yoccoz (2012) | |

| Tracking earthworm communities from soil DNA | Bienert et al. (2012) | |

| Persistence of environmental DNA in freshwater ecosystems | Dejean et al. (2011) | |

| New environmental metabarcodes for analyzing soil DNA: potential for studying past and present ecosystems | Epp et al. (2012) | |

| Don’t make a mista(g)ke: is tag switching an overlooked source of error in amplicon pyrosequencing studies? | Carlsen et al. (2012) | |

| Bioinformatic challenges for DNA metabarcoding of plants and animals | Coissac et al. (2012) | |

| ABGD, Automatic Barcode Gap Discovery for primary species delimitation | Puillandre et al. (2012) | |

| Soil sampling and isolation of extracellular DNA from large amount of starting material suitable for metabarcoding studies | Taberlet et al. (2012b) | |

| 2013 | DNA barcoding as a complementary tool for conservation and valorization of forest resources | Laiou et al. (2013) |

| Incorporating trnH-psbA to the core DNA barcodes improves significantly species discrimination within southern African Combretaceae | Gere et al. (2013) | |

| A DNA mini-barcode for land plants. Mol Ecol Resour | Little (2013) | |

| Toward a unified paradigm for sequence-based identification of fungi | Kõljalg et al. (2013) | |

| Potential of DNA barcoding for detecting quarantine fungi. Phytopathology | Gao and Zhang (2013) | |

| DNA barcoding in plants: evolution and applications of in silico approaches and resources | Bhargava and Sharma (2013) | |

| The short ITS2 sequence serves as an efficient taxonomic sequence tag in comparison with the full-length ITS | Han et al. (2013) | |

| Assessing DNA barcoding as a tool for species identification and data quality control | Shen et al. (2013) | |

| The seven deadly sins of DNA barcoding | Collins and Cruickshank (2013) | |

| Use of the potential DNA barcode ITS2 to identify herbal materials | Pang et al. (2013) | |

| 2014 | 20 years since the introduction of DNA barcoding: from theory to application | Fišer and Buzan (2014) |

| Ecology in the age of DNA barcoding: the resource, the promise and the challenges ahead | Joly et al. (2014) | |

Morphologically distinguishable taxa may not require barcoding; however, subspecies (ssp.), cultivars (cv.), eco- and morphotypes, mutants, species complex and clones can be diagnosed with molecular barcoding. Barcode of a specimen can be compared with sequences derived from other taxa, and in the case of dissimilarities species identity can be determined by molecular phylogenetic analyses based on MOTU, molecular operational taxonomic units (Floyd et al., 2002).

DNA barcoding was particularly useful for marine organisms (Shander and Willassen, 2005), including fishes (Mason, 2003; Ward et al., 2005); soil meiofauna (Blaxter et al., 2004) and freshwater meiobenthos (Markmann and Tautz, 2005); and extinct birds (Lambert et al., 2005). In the rainforests, rapid DNA-based entomological inventories were so effective (Monaghan et al., 2005; Smith et al., 2005) that tropical ecologists were the most active advocates of DNA barcoding (Janzen, 2004). More pragmatically, DNA barcodes have proved to be useful in biosecurity, e.g. for surveillance of disease vectors (Besansky et al., 2003) and invasive insects (Armstrong and Ball, 2005), as well as for law enforcement and primatology (Lorenz et al., 2005).

Barcoding has created some controversy in the taxonomy community (Mallet and Willmott, 2003; Lipscomb et al., 2003; Seberg et al., 2003; DeSalle et al., 2005; Lee, 2004; Ebach and Holdrege, 2005; Will et al., 2005). Traditional taxonomists use multiple morphological traits to delineate species. Today, such traits are increasingly being supplemented with DNA-based information. In contrast, the DNA barcoding identification system is based on what is in essence a single complex character (a portion of one gene, comprising ∼650 bp from the first half of the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I gene sometimes called COXI or COI), and barcoding results are therefore seen as being unreliable and prone to errors in identification (Dasmahapatra and Mallet, 2006). Although the mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase subunit I (CO1) is a widely used barcode in a range of animal groups (Hebert et al., 2003), this locus is unsuitable for use in plants due to its low mutation rate (Kress et al., 2005; Cowen et al., 2006; Fazekas et al., 2008). In addition, complex evolutionary processes, such as hybridization and polyploidy, are common in plants, making species boundaries difficult to define (Rieseberg et al., 2006; Fazekas et al., 2009).

The number and identity of DNA sequences that should be used for barcoding is a matter of debate (Pennisi, 2007; Ledford, 2008). The main DNA barcoding bodies and resources are (1) Consortium for the Barcode of Life (CBOL) http://www.barcodeoflife.org established in 2004. CBOL promotes DNA barcoding through over 200 member organizations from 50 countries, operates out of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History in Washington, (2) International Barcode of Life (iBOL) http://www.ibol.org launched in October 2010, iBOL represents a not-for-profit effort to involve both developing and developed countries in the global barcoding effort, establishing commitments and working groups in 25 countries. The Biodiversity Institute of Ontario is the project’s scientific hub and its director, (3) The Barcode of Life Datasystems (BOLD) http://www.boldsystems.org. The Barcode of Life Datasystems is an online workbench for DNA barcoders, combines a barcode repository, analytical tools, interface for submission of sequences to GenBank, a species identification tool and connectivity for external web developers and bioinformaticians. It is established in 2005 by the Biodiversity Institute of Ontario. The Consortium for the Barcode of Life (CBOL) Plant Working Group (2009) recommended rbcL + matK as a core two-locus combination. However, as these loci encode conserved functional traits it is not clear whether they provide sufficiently high species resolution. One of the challenges for plant barcoding is the ability to distinguish closely related or recently evolved species. Recently plant DNA barcoding has focused on several studies (e.g. Lágler et al., 2006; Chase et al., 2007; Kress and Erickson, 2008; Edwards et al., 2008; Newmaster et al., 2008; Newmaster and Ragupathy, 2009; Seberg and Petersen, 2009; Spooner, 2009; Starr et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2009; Mansour et al., 2009a,b; Clerc-Blain et al., 2010; Kelly et al., 2010; Zuo et al., 2011; Dong et al., 2011; Du et al., 2011; Fu et al., 2011; Gu et al., 2011; Guo et al., 2011; Li et al., 2011a,b; Shi et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2011; Xiang et al., 2011; Xue and Li, 2011; Yan et al., 2011; Yu et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2012; Saarela et al., 2013; Techen et al., 2014).

2. Molecular phylogeny and DNA barcoding

Dobzhansky (1973) stated that nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution. Phylogeny is in the midst of a renaissance, heralded by the widespread application of new analytical approaches and molecular techniques. Phylogenetic analyses provided insights into relationships at all levels of evolution. The phylogenetic trees now available at all levels of the taxonomic hierarchy for animals and plants, which play a pivotal role in comparative studies in diverse fields from ecology to molecular evolution and comparative genetics (Soltis and Soltis, 2000). The basic DNA nucleotide substitution rate was estimated to be 1.3 × 10−8 (Ma and Benetzen, 2004) and 6.5 × 10−9 (Gaut et al., 1996) substitution per locus per year in grasses, and it was estimated to 1.5 × 10−8 in Arabidopsis (Koch et al., 2000).

Traditionally, the studies of variation of a species are based on morphological characters. Variations at molecular level are primarily based on the changes of DNA nucleotide sequences of homologous genes of the populations of a species and higher taxa (Hamby and Zimmer, 1992). Our understanding on genetic variability of organisms located at various levels of the tree of life has advanced greatly with the advancement of the molecular techniques (Avise, 1994; Hillis et al., 1996; Soltis et al., 1998; Hollingsworth et al., 1999; Wen and Pandey, 2005; Mondini et al., 2009). Plant genomes range in size of 8.8 × 106 to more than 300 × 109 bp, however DNA can be prepared from a small amount of leaf tissue (0.1 g). A diverse array of molecular techniques are available for studying genetic variability, including restriction site analysis, analysis of DNA rearrangements, gene and intron loss, and the dominantly used PCR based techniques followed by DNA sequencing and cladistic analyses of the nuclear genome (nuDNA) and both organelle genomes of mitochondria (mtDNA) and chloroplast (cpDNA) (Martins and Hellwig, 2005; Mitchell and Wen, 2005). Multiple sequence alignments software programs of BioEdit Sequence Alignment Editor (North Carolina State University, USA) (Hall, 1999), MULTALIN (Combet et al., 2000), CLUSTAL W (Thompson et al., 1997), FastPCR (Kalendar et al., 2009), BLAST analysis of the NCBI databases (Altschul et al., 1997) and MEGA5 (Tamura et al., 2011) are available for inferring Phylogeny.

The use of DNA or protein sequences to identify organisms was proposed as a more efficient approach than traditional taxonomic practices (Blaxter et al., 2004; Tautz et al., 2003). A chloroplast gene such as matK (maturase K) or a nuclear gene such as ITS (internal transcribed spacer) may be an effective target for barcoding in plants (Kress et al., 2005). Kress et al. (2005) have demonstrated the effectiveness of DNA barcoding in angiosperms. Ribosomal DNA (e.g. ITS) could be used to complement of results based on plastid genes, that may provide a more sophisticated multiple component barcode for species diagnosis and delimitation (Chase et al., 2005). Sequences used for molecular barcoding are the nuclear small subunit ribosomal RNA gene (SSU, also known as 16S in prokaryotes, and 18S in most eukaryotes), the nuclear large-subunit ribosomal RNA gene (LSU, also known as 23S and 28S), the highly variable internal transcribed spacer section of the ribosomal RNA cistron (ITS, separated by the 5S ribosomal RNA gene into ITS1 and ITS2 regions), the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase 1 (CO1 or cox1) gene and the chloroplast ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase large subunit (rbcL) gene. Kress et al. (2005) have suggested that ITS spacer region and the plastid trnH-psbA have greater potential for species-level discrimination than any other locus, the trnH-psbA combined with rp136-rpf8, and trnL-F ranked the highest amplification success with appropriate sequence length (Kress et al., 2005).

2.1. Ribosomal DNA (rDNA) of the nuclear genome (nuDNA) – ITS

Sequence analyses of the nuclear multicopy ribosomal DNA (rDNA) genes encoding for structural RNAs (rRNAs) of ribosomes have been widely used in plant phylogenetics (Baldwin, 1992; Baldwin et al., 1995; Hershkovitz et al., 1999). The rDNA is arranged in tandem repeats in one or a few chromosomal loci with thousands of repeats. In total, rDNA can comprise as much as 10% of the total plant genome (Zimmer et al., 1980). The size of repeating unit of the human rDNA (18S rRNA; 28S rRNA; 5.8S rRNA; 5′ETS; 3′ETS; ITS1; ITS2; intergenic spacer; cdc27 pseudogene; p53 binding site) is 42.999 bp (NCBI # U13369).

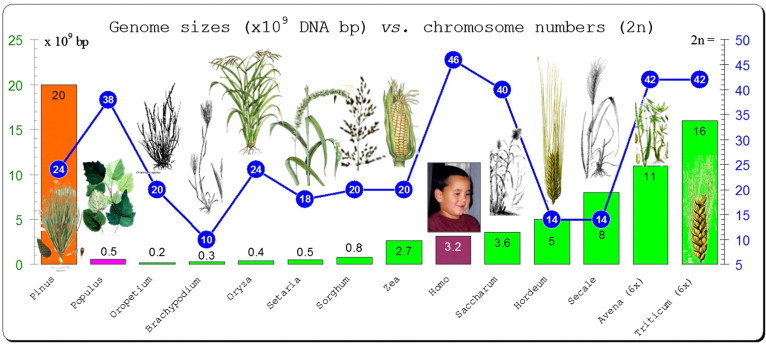

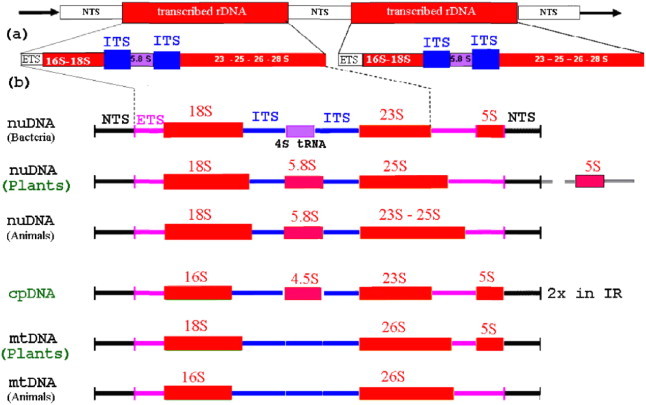

The majority of angiosperm genome sizes have a narrow range between 135 and 160 kb (Fig. 1). In plant genomes, the rDNA cistron encodes 18S, 26S and 5.8S rRNAs, which are separated by the two internal transcribed spacers (ITS1 and ITS2), and the cistron is flanked by the 5′ and 3′ external transcribed spacers (5′-ETS and 3′-ETS) (Fig. 2). The regions are relatively short sequences, ITS1 200–300 bp, ITS2 180–240 bp, and 5.8S 160 bp in flowering plants. The amplification and sequencing primers are highly universal (White et al., 1990). Eukaryotic ribosomes consist of two subunits with the large subunit (LSU), which is about twice the size of the small subunit (SSU). The 18S gene encodes the SSU; and LSU is encoded by 26S and 5.8S. The ITS region comprises the 5.8S gene, which has been the most widely used molecular marker at interspecific and intergeneric levels (Feliner et al., 2004). Because of the influence of concerted evolution (Zimmer et al., 1980), the polymorphisms are not due to the intra-genomic variability at these loci, rather, a more frequent merge of different ITS copies within the same genome (Campbell et al., 1997; Buckler et al., 1997; Hershkovitz et al., 1999; Feliner et al., 2004).

Figure 1.

Sizes of plant genomes. Sizes (bp) vs. chromosome numbers (2n) of plant genomes from different taxa and compared to human genome size (3.2 × 109 bp).

Figure 2.

rDNA sequence domains of tandem gene clusters (about 10 kb each) of nuclear and organellar rDNAs of different organisms and organelles (cp and mt). (a) Pre-rDNA in the genome and (b) the translated ribosomal subunits. Abbreviations: ETS – external transcribed spacer, ITS – internal transcribed spacer, NTS – non transcribed spacer, mt – mitochondrion; cp – chloroplast, nu – nucleus, 5.8S to 28S – ribosomal subunits of nucleoproteins of rRNAs.

The 18S gene is a slowly evolving marker and is also suitable for inferring phylogenies of angiosperms (Hamby and Zimmer, 1992; Soltis et al., 1997), and closely related families such as Caryophyllales (Cuenoud et al., 2002); however, the most common limitation of 18S rDNA using for phylogenetic analyses, is its low levels of variability within the angiosperms.

The phylogenetic utility of the 26S sequences has not been widely explored. In plants, the 26S gene is about 3.4 kb long and includes 12 expansion segments (ES), which are variable (Bult et al., 1995). The overall nucleotide substitution rate of 26S is 1.6–2.2 times higher than that in 18S (Kuzoff et al., 1998). The 26S sequences have been used to discriminate closely related families such as of Apiales (Chandler and Plunkett, 2004), and for determining phylogenetic position of plant families (Simmons et al., 2001; Neyland, 2002).

The external transcribed spacer (ETS) region (especially the 3′ end of the 5′-ETS sequence adjacent to 18S) has also been used for phylogenetic analyses. The frequency of ETS polymorphism is still poorly understood. Furthermore, the internal repetitive structure of the ETS region can make the amplifications and sequence alignments difficult (Baldwin and Markos, 1998; Linder et al., 2000).

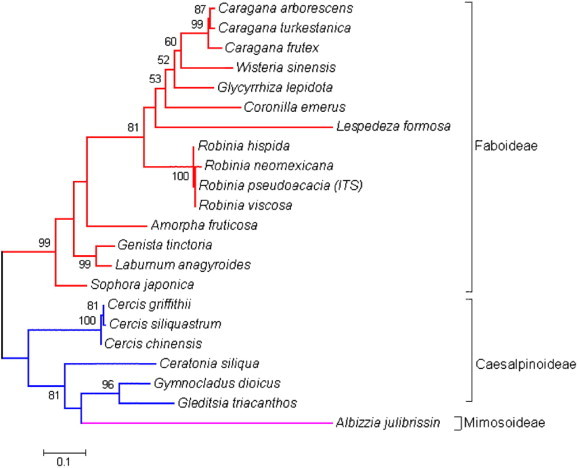

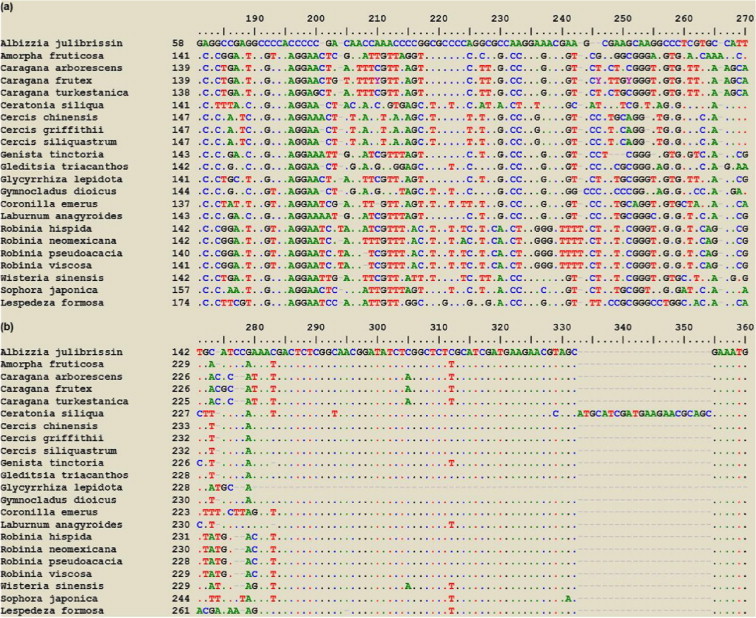

To compare all rDNA loci, the ITS is the most commonly sequenced locus used in plant phylogenetic studies (Pandey and Ali, 2006, 2012; Pandey et al., 2009; Choudhary et al., 2011; Ali et al., 2012, 2013; Lee et al., 2013) (Figs. 3 and 4). The advantage of the ITS region is that it can be amplified in two smaller fragments (ITS1 and ITS2) with the joining 5.8S locus. The quite conserved 5.8S region, in fact, contains enough phylogenetic signals for discrimination at levels of orders and phyla, however this locus is not the concern of barcoding. ITS regions often vary by insertions and deletions within an individual rather than substitution, which makes sequencing difficult as several ITS sequence types are being analyzed simultaneously (Elbadri et al., 2002).

Figure 3.

Sample of ITS phylogeny. ITS cladogaram of Legume trees. ITS sequences of twenty-two species were analyzed by BioEdit (Hall, 1999), and ML (Maximum Likelihood; Hillis et al., 1994) cladogaram was edited by MEGA4 (Tamura et al., 2007) (×1000 bootstrap). The three subfamilies of Fabaceae and the substitution rate (0.1) are indicated.

Figure 4.

Samples of ITS sequence polymorphism. Sequence alignment of ITS sequences of rDNAs of twenty-two Legume trees studied with low (a) (180–270 nt) and high (b) (270–360 nt) sequence similarities.

Taxonomy is a synthetic science, drawing upon data from such diverse fields as morphology, anatomy, embryology, cytology, and chemistry. In recent years, development of techniques in molecular biology including those for molecular hybridization, cloning, restriction endonuclease digestions and nucleic acid sequencing have provided many new tools for the investigation of phylogenetic relationships. The reconstructions of angiosperm phylogeny have relied largely on plastid and mitochondrial genes (Chase et al., 1993; Nandi et al., 1998; Savolainen et al., 2000; Hilu et al., 2003; Zhu et al., 2007; Qiu et al., 2010) and sometimes entire plastid genomes (Jansen et al., 2007; Moore et al., 2007, 2010) and nuclear genes (Doyle et al., 1994; Soltis et al., 1997; Mathews and Donoghue, 1999; Finet et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2011). Moreover, our understanding of the relationships among organisms at various levels in the tree of life has been advanced greatly in the last about three decades with the aid of DNA molecular systematic techniques and phylogenetic theory, this has resulted into a classification ‘Angiosperm Phylogeny Group’ (APGI, 1998; APGII, 2003; APGIII, 2009; Haston et al., 2009) of the families of the flowering plants (http://www.mobot.org/MOBOT/research/APweb/). From the first report of the utility of the internal transcribed spacers (ITS) sequence of nuclear ribosomal DNA (nrDNA) in plants (Baldwin, 1992), it has been extensively used to distinguish even very closely related species (Chen et al., 2010; Yao et al., 2010). Moreover, in the last two decades, the ITS sequence has gained much attention, along with the smartest genes available for the molecular phylogeny and taxonomy (Ali et al., 2013). Recently ITS2 loci have been suggested as a universal DNA barcode for identification of plant species and as a complementary locus for CO1 to identify animal species (Chen et al., 2010; Yao et al., 2010). The ITS2 region has been shown to be applicable in discrimination among a wide range of plants within families of Asteraceae, Rutaceae, Rosaceae and so on (Gao et al., 2010; Luo et al., 2010; Yao et al., 2010; Pang et al., 2011). The analyses of ITS2 secondary structures of ribosomal genes have been used to improve the quality of phylogenetic reconstructions (Keller et al., 2010); however, its assessment for phylogeny at higher hierarchy is still lacking.

2.2. Chloroplast DNA (cpDNA)

Chloroplast DNA (Figs. 5 and 6) has been used very frequently in plant systematic and phylogenetic studies. It is a circular molecule ranging in size of 120–217 kb, with a unique exception of green alga Floydiella terrestris with huge cpDNA of 521.168 bp (NCBI # NC_014346) (Gyulai et al., 2012). There are about 100 functional genes in the chloroplast genome. It contains, with few exceptions (IRL – IRless), two duplicate regions in reverse orientation, known as the inverted repeats (IR) of 10–76 kb, which divides the chloroplast genome into large (LSC) and small single-copy (SSC) regions. The structural organization of chloroplast genome is highly conserved, i.e., relatively free of large deletions, insertions, transpositions, inversions and SNPs (single nucleotide polymorphism), which make it advantageous for phylogenetic studies. Chloroplast DNA is a relatively abundant (generally, 50 chloroplast per cell multiplied with 50 cpDNA copy per chloroplast) compared to nuclear DNA (generally 2n), which facilitating DNA extraction and analysis. Chloroplast DNA is usually uniparentally inherited (maternally in angiosperms and paternally in gymnosperms, in general, with exceptions), which facilitates to determine the maternal parent in hybrids and allopolyploids (Ackerfield and Wen, 2003). Some chloroplast regions like psbA-trnH spacer, and rps16 intron gene evolve relatively rapidly. There are a number of noncoding cpDNA regions which are also useful target of study such as the intergenic spacer of atpB-rbcL (Baker et al., 1999; Asmussen and Chase, 2001; Manen and Natali, 1995; Manen et al., 2002), the rps16 intron, matK, ndhF, ycf6-psbM, and psbM-trnD (Oxelman et al., 1997; Andersson and Rova, 1999; Downie and Katz-Downie, 1999; Wallander and Albert, 2000; Štorchová and Olson, 2007), rpL16 intron (Jordan et al., 1996; Baum et al., 1998), trnL-F (Wallander and Albert, 2000), and psbA-trnH spacer, trnH-psbA (Kress et al., 2005; Chase et al., 2005) by using universal primers.

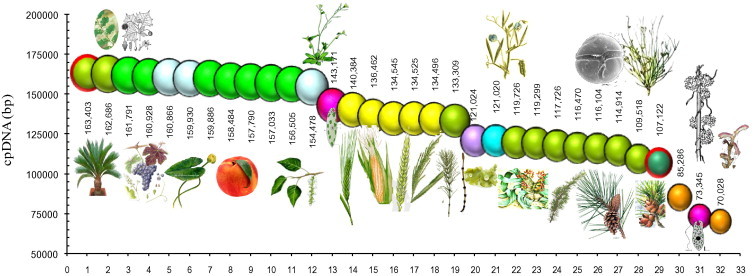

Figure 5.

cpDNA. Comparative sizes (bp) of total plant cpDNAs of different taxa (with NCBI accession numbers; Altschul et al., 1997). (1) Gymnosperm Cycas taitungensisNC_009618. (2) Transition species between gymnosperrm and angiosperms Amborella trichopodaNC_005086. (3) Platanus occidentalisNC_008335. (4) Vitis viniferaNC_007957. (5) Nuphar advenaNC_008788. (6) Nymphaea albaNC_006050. (7) Liriodendron tulipiferaNC_008326. (8) Morus indicaNC_008359. (9) Prunus persicaNC_014697. (10) Populus trichocarpaNC_009143. (11) Populus albaNC_008235. (12) Arabidopsis thalianaNC_000932. (13) Unicellular green alga Euglena gracilisNC_001603. (14) Zea maysNC_001666. (15) Hordeum vulgareNC_008590. (16) Triticum aestivumNC_002762. (17) Oryza sativa JaponicaNC_001320. (18) Oryza sativa indicaNC_008155. (19) Equisetum arvenseNC_014699. (20) Marchantia polymorphaNC_001319. (21) Lathyrus sativusNC_014063. (22) Welwitschia mirabilisNC_010654. (23) Cedrus deodaraNC_014575. (24) The longest-living plant Pinus longaevaNC_011157. (25) Durinskia balticaNC_014287. (26) Pinus monophyllaNC_011158. (27) Gnetum parvifoliumNC_011942. (28) Ephedra equisetinaNC_011954. (29) Cathaya argyrophyllaNC_014589 (described in 1955). (30) Cuscuta obtusifloraNC_009949. (31) Euglena longaNC_002652. (32) Epifagus virginianaNC_001568.

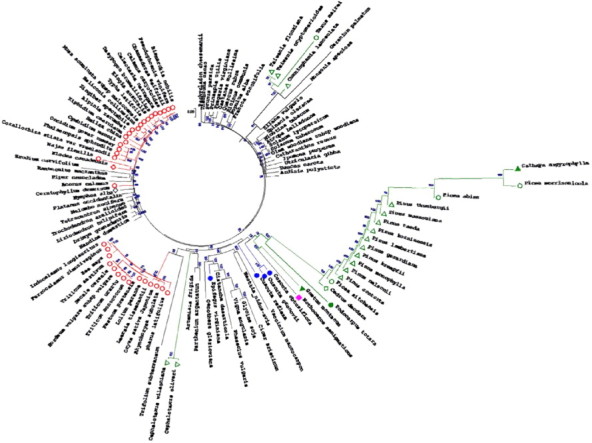

Figure 6.

Cladogram of total cpDNAs. ML (Maximum Likelihood; Hillis et al., 1994) cladogaram of total cpDNA genomes with 1000× bootstrap values (MEGA4; Tamura et al., 2007). Polyphyletic Dicots of Angiosperm are not labeled; monocots (○) show four cpDNA lineages including the individual Acorus. Gymnosperm clades (green) show three lineages: (1) Gnetum (▾) – Podocarpus (●) and the Pinaceae species of Pinus, Picea, Abies, Cathaya and Cedrus. Cathaya (▴) (NC_014589) has the smallest cpDNA genome (107.122 bp) of Coniferales. This clade shows close genetic distance to the bryophyte Nothoceros; (2) Taxodiaceae including Taiwania, Taxus, and Cunninghamia, which clade is close to eudicot Monsomia and Geranium; and (3) the evolutionarily youngest gymnosperm Cepahlotaxaceae (Cephalotaxus) of Coniferales. Water submerged plants of monocot Elodea and dicot Ceratophyllum (◊); and parasite plants with reduced cpDNA genomes of Cuscuta and Epifagus (●) are also labeled. Scale (0.05) shows relative genetic distances based on substitution rate. Accession numbers are available at NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) (Altschul et al., 1997) and CGP (http://chloroplast.ocean.washington.edu). For computing about 21 million nucleotides an eight core computer with 24 GB RAM was used running for 2–3 weeks.

For phylogenetic investigations cpDNA has been more readily exploited (Fig. 6), than the nuclear genome for barcoding, similar to mitochondrial genomes of animals. Kress et al. (2005) have compared plastid genomes of Atropa and Nicotiana, and recorded that nine intergenic spacers trnK-rps16, trnH-psbA, rp136-rps8, atpB-rbcL, ycf6-psbM, trnV-atpE, trnC-ycf6, psbM-trnD, and trnL-F fulfill the barcode criteria. For comparison, ITS had a much higher divergence value (13.6%) than any plastid regions, especially rbcL, which is far the lowest in divergence (0.83%).

2.3. Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA)

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) analysis has had a major impact on the study of phylogeny and population genetics in animals. Plant mtDNAs are rather poorly studied compared to animals (Palmer et al., 2000). Plant mtDNA encodes approximately 5% of the proteins found in the mitochondrion. Plant mtDNA is ‘abnormally’ large and variable in size (300–600 kb), many times larger than animal mtDNAs (16–25 kb). In Cucurbitaceae and Malvaceae, the mitochondrial genome was reported to exceed 2900 kb (Cucumis melo) (Alverson et al., 2010) (Figs. 7, 10 and 11). Many foreign sequences are found in plant mtDNA. Chloroplast DNA sequences as large as 12 kb in length, are found integrated in plant mtDNAs, and cpDNA sequences can fill up about 5–10% of the mtDNA. Plant mitochondrial genome seems to be unstable for barcoding for its frequent intramolecular and intermolecular recombinations, which continuously change gene orders (Palmer, 1992; Palmer et al., 2000). However, nucleotide substitution rates of mtDNA are 3–4 times lower than cpDNA, about 12 times lower than those of plant nuDNA, and 40–100 times lower than those of animal mtDNA (Cho et al., 2004). Only a few mitochondrial markers have shown promise for phylogenetic utility (Demesure et al., 1995; Freudenstein and Chase, 2001). However, the divergence of coding region of cytochrome oxidase subunit 1 (cox1) (referred as CO1) among plant and animal families has found documented to be only a few base pairs across 1.4 kb of sequence (Hebert et al., 2003; Folmer et al., 1994), which makes it useful for barcoding.

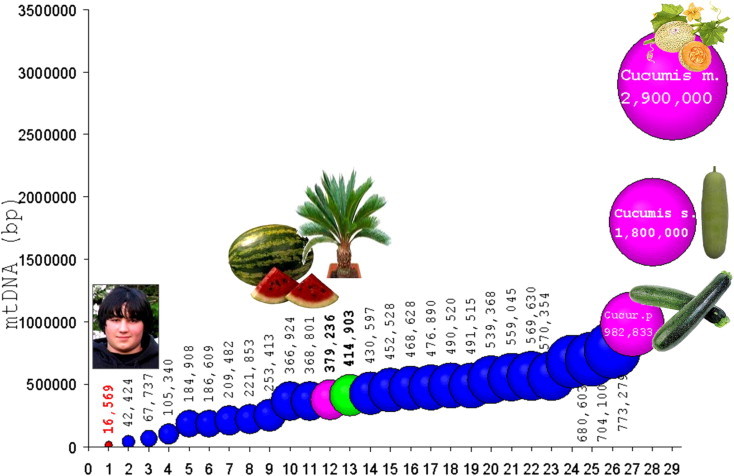

Figure 7.

The mtDNA (mitome) sizes (bp) of organisms in increasing order including the only wood available Cycas (13). Human mtDNS (1), and lower plants (2–7) are indicated (NCBI accession #, Altschul et al. 1997). (1) Homo s.NC_012920. (2) Mesostigma v.NC_008240. (3) Chara v.NC_005255. (4) Physcomitrella p.NC_007945. (5) Megaceros ae.NC_012651. (6) Marchantia p.NC_001660. (7) Phaeoceros l.NC_013765. (8) Brassica n.NC_008285. (9) Silene l.NC_014487. (10) Arabidopsis th.NC_001284. (11) Beta v.NC_002511. (12) Citrullus l.NC_014043. (13) Cycas taitungensisNC_010303. (14) Nicotiana t.NC_006581. (15) Triticum ae.NC_007579. (16) Sorghum b.NC_008360. (17) Carica p.NC_012116. (18) Oryza s. J.NC_011033. (19) Oryza s. I.NC_007886. (20) Zea lux.NC_008333. (21) Oryza r.NC_013816. (22) Zea m.NC_007982. (23) Zea pren.NC_008331. (24) Zea parv.NC_008332. (25) Tripsacum d.NC_008362. (26) Vitis v.NC_012119. (27) Cucurbita p.NC_014050. (28) Cucumis sativus. (29) Cucumis melo with the largest mtDNA. The mtDNAs of Human (1), Cucurbits (12, 27, 28, 29), and gymnosperm Cycas (13) are indicated.

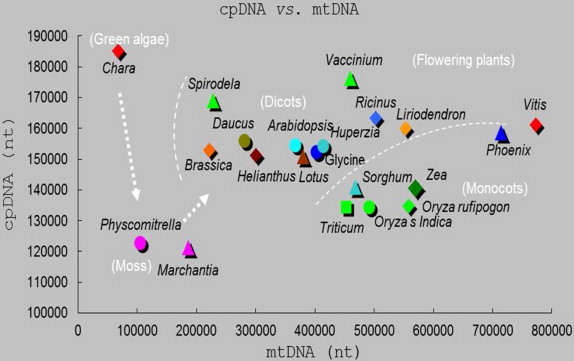

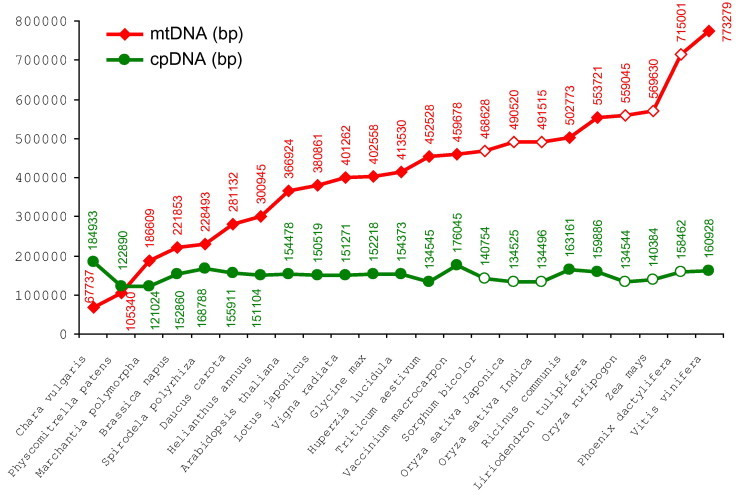

Figure 10.

Size correlations between cpDNA and mtDNA genomes show a shift from green algae (Chara vulgaris) with high cpDNA/mtDNA ratio (2.73) through mosses of Physcomitrella patens (1.16) and Marchantia polymorpha (0.65) toward flowering plants of dicots to monocots with exception of Vitis. The decreasing ratio of cpDNA/mtDNA indicates an enlarging mtDNA during the evolution: Spirodela polyrhiza (0.74); Brassica napus (0.69); Daucus carota (0.55); Helianthus annuus (0.50); Arabidopsis thaliana (0.42); Lotus japonicus (0.40); Vaccinium macrocarpon (0.38); Glycine max (0.38); Vigna radiata (0.38); Huperzia lucidula (0.37); Ricinus communis (0.32); Sorghum bicolor (0.30); Triticum aestivum (0.29); Liriodendron tulipifera (0.29); Oryza sativa Japonica (0.274); Oryza sativa Indica (0.273); Zea mays (0.25); Oryza rufipogon (0.24); Phoenix dactylifera (0.22); Vitis vinifera (0.21). NCBI (Altschul et al., 1997) data were plotted by XY plot of Microsoft Windows Xcel program.

Figure 11.

Changes of organelle genome sizes during the evolution (mtDNA – mitochondrial DNA; cpDNA chloroplast DNA) (see Fig. 10). NCBI (Altschul et al., 1997) data were plotted by Microsoft Windows Xcel program. Monocots are labeled with open symbols.

3. Molecular phylogenetic analyses

In DNA barcoding the sequences of the barcoding region are obtained from various individuals. The resulting sequence data are then used to construct a phylogenetic tree. In such a tree, similar, putatively related individuals are clustered together. The term ‘DNA barcode’ seems to imply that each species is characterized by a unique sequence, but there is of course considerable genetic variation within each species as well as between species. However, genetic distances between species are usually greater than those within species, so the phylogenetic tree is characterized by clusters of closely related individuals, and each cluster is assumed to represent a separate species (Dasmahapatra and Mallet, 2006).

GenBank (-the NIH genetic sequence database, an annotated collection of all publicly available DNA sequences) has a very important role in DNA barcoding. GenBank is part of the International Nucleotide Sequence Database Collaboration, which comprises the DNA DataBank of Japan (DDBJ), the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL), and GenBank at NCBI. The GenBank sequence database is an open access, annotated collection of all publicly available nucleotide sequences and their protein translations. This database is produced at National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) as part of the International Nucleotide Sequence Database Collaboration. GenBank and its collaborators receive sequences produced in laboratories throughout the world from more than 100,000 distinct organisms. GenBank is built by direct submissions from individual laboratories, as well as from bulk submissions from large-scale sequencing centers. GenBank has merged the values of natural history with those of the experimental sciences. The Entrez Nucleotide and BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) are the two main ways to search and retrieve data from GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/).

A wide range of programs (detailed information can be browsed at http://bioinformatics.unc.edu/software/opensource/index.htm, http://molbiol-tools.ca/molecular_biology_freeware.htm#Phylogeny, and http://evolution.genetics.washington.edu/phylip/software.html#recent) are available for sequence data analysis. The three commonly used methods for phylogenetic analysis are MP (maximum parsimony), ML (maximum likelihood), and (BI) Bayesian inference. Of them ML (maximum likelihood) was found to be the most discriminative (Hillis et al., 1994). The maximum parsimony algorithm (Farris, 1970; Swofford et al., 1996) searches for the minimum number of genetic events (e.g. nucleotide substitutions) to infer the shortest possible tree (i.e., the maximally parsimonious tree). Often the analysis generates multiple equally most parsimonious trees. When evolutionary rates are drastically different among the species analyzed, results from parsimony analysis can be misleading (e.g., long-branch attraction; Felsenstein, 1978). Parsimony analysis is most often performed with the computer program PAUP∗ 4.0 (Swofford, 2002), and MEGA (Tamura et al., 2007, 2011). The maximum likelihood (ML) method (Felsenstein, 1985; Hillis et al., 1994) evaluates an evolutionary hypothesis in terms of the probability that the proposed model and the hypothesized history would give rise to the observed data set properly. The topology with the highest maximum probability or likelihood is then chosen. This method may have lower variance than other methods and is thus least affected by sampling error and differential rates of evolution. It can statistically evaluate different tree topologies and use all of the sequence information. The Bayesian phylogenetic inference is model-based method and was proposed as an alternative to maximum likelihood (Rannala and Yang, 1996; Yang and Rannala, 1997). The computer program MrBayes 3.0 (Huelsenbeck and Ronquist, 2001) performs Bayesian estimation of phylogeny based on the posterior probability distribution of trees, which is approximated using a simulation technique called Markov chain Monte Carlo (or MCMC). MrBayes can combine information from different data partitions or subsets evolving under different stochastic evolutionary models. This allows the user to analyze heterogeneous data sets consisting of different data types, including morphology and nucleotides. Bayesian inference has facilitated the exploration of parameter-rich evolutionary models (Table 2).

Table 2.

A brief of the commonly used programs used for the phylogeny and DNA barcoding.

| Phylogenetic analysis software | Description | Link/References |

|---|---|---|

| Bayesian evolutionary analysis sampling trees (BEAST) | A Bayesian MCMC program for inferring rooted trees under the clock or relaxed-clock models. It can be used to analyze nucleotide and amino acid sequences, as well as morphological data. A suite of programs, such as Tracer and FigTree, are also provided to diagnose, summarize and visualize results | http://beast.bio.ed.ac.uk |

| Drummond and Rambaut (2007) | ||

| BioEdit | BioEdit is a fairly comprehensive sequence alignment and analysis tool. BioEdit supports a wide array of file types and offers a simple interface for local BLAST searches | http://www.mbio.ncsu.edu/bioedit/bioedit.html |

| Hall (1999) | ||

| ClustalX | ClustalX is a windows interface for the ClustalW multiple sequence alignment program. It provides an integrated environment for performing multiple sequence and profile alignments and analyzing the results. This program allows to create Neighbor Joining trees with bootstrapping | http://www.clustal.org/ |

| Thompson et al. (1997) | ||

| ClustalW | Multiple Sequence Alignment (EBI, United Kingdom). This provides one with a number of options for data presentation, homology matrices [BLOSUM (Henikoff), PAM (Dayhoff) or GONNET, and presentation of phylogenetic trees (Neighbor-Joining, Phylip or Distance). Other sites offering ClustalW alignment are at the Pasteur Institute, Kyoto University and chEMBLnet.org | http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalw2/ |

| DNA for Windows | DNA for Windows is a compact, easy to use DNA analysis program, ideal for small-scale sequencing projects | http://www.dna-software.co.uk/ |

| Geneious | Geneious (Alexei Drummond Biomatters Ltd. Auckland, New Zealand) provides an automatically-updating library of genomic and genetic data; for organizing and visualizing data. It provides a fully integrated, visually-advanced toolset for: sequence alignment and phylogenetics; sequence analysis including BLAST; protein structure viewing, NCBI, EMBL, Pubmed auto-find, etc. | http://www.geneious.com/ |

| MAFFT | MAFFT is a multiple sequence alignment program for unix-like operating systems. It offers a range of multiple alignment methods, L-INS-i (accurate; for alignment of <∼200 sequences), FFT-NS-2 (fast; for alignment of <∼10,000 sequences), etc. | http://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/software/ |

| FigTree | FigTree is designed as a graphical viewer of phylogenetic trees to display summarized and annotated trees produced by BEAST | http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/ |

| Format Converter v2.2.5 | This program takes as input a sequence or sequences (e.g., an alignment) in an unspecified format and converts the sequence(s) to a different user-specified format | http://www.hiv.lanl.gov/content/sequence/FORMAT_CONVERSION/form.html#details_section |

| Genetic algorithm for rapid likelihood inference (GARLI) | A program that uses genetic algorithms to search for maximum likelihood trees. It includes the GTR + Γ model and special cases and can analyze nucleotide, amino acid and codon sequences. A parallel version is also available | http://code.google.com/p/garli |

| Zwickl (2006) | ||

| Hypothesis testing using phylogenies (HYPHY) | A maximum likelihood program for fitting models of molecular evolution. It implements a high-level language that the user can use to specify models and to set up likelihood ratio tests | http://www.hyphy.org |

| Kosakovsky et al. (2005) | ||

| ITS2 Database | The ITS2 Database presents an exhaustive dataset of internal transcribed spacer 2 sequences from NCBI GenBank accurately reannotated. Following an annotation by profile Hidden Markov Models (HMMs), the secondary structure of each sequence is predicted. The ITS2 Database also provides several tools to process your own ITS2 sequences, including annotation, structural prediction, motif detection and BLAST (Altschul and Gapped, 1997) search on the combined sequence–structure information. Moreover, it integrates trimmed versions of 4SALE (Seibel et al., 2006, 2008) and ProfDistS (Wolf et al., 2008) for multiple sequence–structure alignment calculation and Neighbor Joining (Saitou and Nei, 1987) tree reconstruction. Together they form a coherent analysis pipeline from an initial set of sequences to a phylogeny based on sequence and secondary structure | http://its2.bioapps.biozentrum.uni-wuerzburg.de/ |

| Molecular evolutionary genetic analysis (MEGA) | A Windows-based program with a full graphical user interface that can be run under Mac OSX or Linux using Windows emulators. It includes distance, parsimony and likelihood methods of phylogeny reconstruction, although its strength lies in the distance methods. It incorporates the alignment program ClustalW and can retrieve data from GenBank | http://www.megasoftware.net |

| Tamura et al. (2011) | ||

| MrBayes | A Bayesian MCMC program for phylogenetic inference. It includes all of the models of nucleotide, amino acid and codon substitution developed for likelihood analysis | http://mrbayes.net |

| Huelsenbeck and Ronquist (2001) | ||

| Modeltest | Modeltest is a program that uses hierarchical likelihood ratio tests (hLRT) to compare the fit of the nested GTR (General Time Reversible) family of nucleotide substitution models. Additionally, it calculates the Akaike Information Criterion estimate associated with the likelihood scores | http://darwin.uvigo.es/software/jmodeltest.html |

| Posada and Crandall (1998) | ||

| Oligo Calculator | On line tool for to find length, melting temperature, %GC content and molecular weight of DNA sequence | http://mbcf.dfci.harvard.edu/docs/oligocalc.html |

| Phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood (PAML) | A collection of programs for estimating parameters and testing hypotheses using likelihood. It is mostly used for tests of positive selection, ancestral reconstruction and molecular clock dating. It is not appropriate for tree searches | http://abacus.gene.ucl.ac.uk/software |

| Yang (2007) | ||

| Phylogeny.fr | Phylogeny.fr – is a simple to use web service dedicated to reconstructing and analyzing phylogenetic relationships between molecular sequences. It includes multiple alignment (MUSCLE, T-Coffee, ClustalW, ProbCons), phylogeny (PhyML, MrBayes, TNT, BioNJ), tree viewer (Drawgram, Drawtree, ATV) and utility programs (e.g. Gblocks to eliminate poorly aligned positions and divergent regions) | http://www.phylogeny.fr/ |

| Dereeper et al. (2008) | ||

| PHYLIP | A package of programs for phylogenetic inference by distance, parsimony and likelihood methods | http://evolution.gs.washington.edu/phylip.html |

| PhyML | A fast program for searching for the maximum likelihood trees using nucleotide or protein sequence data | http://www.atgc-montpellier.fr/phyml/binaries.php |

| Guindon and Gascuel (2003) | ||

| PAUP | David Swofford of the School of Computational Science and Information Technology, Florida State University, Tallahassee, Florida has written PAUP∗ (which originally meant Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony). PAUP∗ version 4.0beta10 has been released as a provisional version by Sinauer Associates, of Sunderland, Massachusetts. It has Macintosh, PowerMac, Windows, and Unix/OpenVMS versions. PAUP∗ has many options and close compatibility with MacClade. It includes parsimony, distance matrix, invariants, and maximum likelihood methods and many indices and statistical tests | http://paup.csit.fsu.edu |

| Swofford (2002) | ||

| ProfDistS | Distance based phylogeny on sequence–structure alignments. Bioinformatics. 24, 2401–2402 | Wolf et al. (2008) |

| MacClade | MacClade is a computer program for phylogenetic analysis written by David Maddison and Wayne Maddison. Its analytical strength is in studies of character evolution. It also provides many tools for entering and editing data and phylogenies, and for producing tree diagrams and charts | http://macclade.org/ |

| Neighbor-Joining | Neighbor-Joining method is proposed for reconstructing phylogenetic trees from evolutionary distance data | Saitou and Nei (1987) |

| PHYLIP | PHYLIP (the PHYLogeny Inference Package) is a package of programs for inferring phylogenies. PHYLIP is the most widely-distributed phylogeny package, and competes with PAUP to be the one responsible for the largest number of published trees | http://evolution.genetics.washington.edu/phylip.html |

| RAxML | A fast program for searching for the maximum likelihood trees under the GTR model using nucleotide or amino acid sequences. The parallel versions are particularly powerful | http://scoh-its.org/exelixis/software.html |

| Stamatakis (2006) | ||

| Readseq | A tool for converting between common sequence file formats, particularly useful for those using various phylogenetic analysis tools | http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/sfc/readseq/ |

| 4SALE | A tool for synchronous RNA sequence and secondary structure alignment and editing | Seibel et al. (2006, 2008) |

| Sequencher | The Premier DNA Sequence Analysis Software for Sanger and NGS Datasets | http://www.genecodes.com/ |

| Tree analysis using new technology (TNT) | A fast parsimony program intended for very large data sets | http://www.zmuc.dk/public/phylogeny/TNT |

| Goloboff et al. (2008) | ||

| TreeView | TreeView provides a simple way to view the contents of a NEXUS, PHYLIP, or other format tree file | http://taxonomy.zoology.gla.ac.uk/rod/treeview.html |

4. Retrotransposon based barcoding

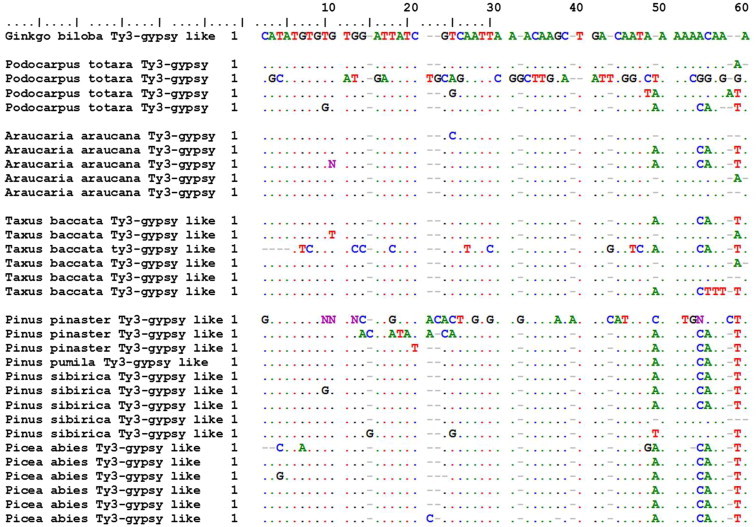

Retrotransposons (RTs) are ubiquitous and dispersed throughout the host genome of an organism with correlations to genome sizes (Alzohairy et al., 2012, 2013). RTs are classified into two main groups of long terminal repeats (LTR-RTs) and non-LTR retrotransposons with several subgroups (i.e. families). The copy-and-paste way of transposition of RTs consists of three molecular steps including transcription of an RNA copy from the genomic RT, followed by reverse transcription of the RNA copy to cDNA, which is synthesized by reverse transcriptase (RTase), and the final reintegration of cDNA-RT into a new location of the genome. These processes lead to new and new genomic insertions of the RTs without excision of the original element. Finally, a population of the given RT develops hundreds and hundreds of copies in the host genome with sequence modifications (i.e. polymorphism) due to the lack of proofreading activity of RTases (Kalendar et al., 2000). All these molecular characteristics of RTs provide targets for barcoding (Lágler et al., 2006; Schulman, 2007; Mansour et al., 2009a,b), and tracking of horizontal and vertical spread of RTs (Figs. 8 and 9).

Figure 8.

Samples’ (60 nt) sequence polymorphism of pPongy2 LTR retrotransposons. Spread and sequence diversity of RT (reverse transcriptase) gene of pPongy2, a Ty3-gypsy-like LTR-retrotransposon though the evolution of gymnosperms from Gingo → Podocarpus (248 My) → Araucaria (230 My) → Taxus (206 My) → Pinaceae (180 My). Sequence # AJ290647.1 was downloaded from NCBI and aligned by BioEdit program (Hall, 1999).

Figure 9.

The pPongy2 cladogram. Fast Minimum Dendrogram edited by NCBI server (Altschul et al., 1997) shows the spread among-and-within species of RT (reverse transcriptase) gene of pPongy2, a Ty3-gypsy-like LTR-retrotrasnposon though the evolutionary lineage of gymnosperms from Gingo → Podocarpus (248 My) → Araucaria (230 My) → Taxus (206 My) → Pinaceae (180 My). Genetic distance (scale 0.005) and branch length are indicated, and gymnosperm species are labeled with different color symbols. The accession numbers of taxon included in analyses were Araucaria araucana (AJ290651, AJ290652, AJ290653, AJ290654, AJ290655), Ginkgo biloba (AJ290656), Picea abies (AJ290585, AJ290586, AJ290591, AJ290592, AJ290593, AJ290594), Pinus pinaster (AJ290605, AJ290606), Pinus pumila (AJ290616), Pinus sibirica (AJ290623, AJ290626, AJ290629, AJ290630, AJ290631), Podocarpus totara (AJ290647, AJ290648, AJ290649, AJ290650), Taxus baccata (AJ290640, AJ290641, AJ290642, AJ290643, AJ290644, AJ290645).

5. Metabarcoding

In the early days, DNA barcoding mainly focused on taxonomic research. Nowadays, DNA barcoding could be used for a wide variety of purposes and the research field has diversified itself. Not only DNA of intact and isolated species is used, but also DNA that is shed into the environment by organisms (e.g. DNA from skin, nails, hairs, waste products, etc.). This form of DNA is called environmental DNA, or eDNA, and is usually highly degraded. It could be found in environmental samples like air, water or soil and it could be extracted without isolating the organisms (Taberlet et al., 2012a). The eDNA fragments are shorter than normal DNA fragments and thus an adjusted barcoding method is needed. Specifically, it requires the use of shorter barcodes (Hajibabaei et al., 2006). A second direction of development concerns the use of environmental samples, not only to identify one single species, but to identify a wide variety of species in one experiment. This is called metabarcoding. The development of metabarcoding approaches was aided by the discovery of NGS, which allows parallel reading of DNA sequences from a single DNA-extract without a necessity for cloning (i.e. Taberlet et al., 2012a,b,c; Hajibabaei, 2012). In this respect, metabarcoding differs from normal DNA barcoding in the sense that classic DNA barcoding aims to identify intact specimens (e.g. with complete genomes) up to species level, and metabarcoding aims to identify degraded DNA samples (eDNA) up to family level or higher.

6. Materials for DNA barcoding

DNA is a relatively stable molecule, besides fresh sample, DNA can also be isolated from museum collections, including animal specimens preserved in formalin (Fang et al., 2002). Plant DNA can be extracted from herbarium specimens up to 100 years old, and also from archeological plant remains (Szabó et al., 2005; Lágler et al., 2005; Gyulai et al., 2006, 2012; Palmer et al., 2012). Plant DNA quality depends on methodology adopted for drying after being pressed. If specimen-drying facilities are not immediately available, especially in humid tropical climates, botanists often treat pressed samples with ethanol to temporarily preserve against fungal attack and degradation. Alcohol has been shown to be detrimental to recovering high-quality DNA. It is encouraging that museum specimens of insects dried from ethanol storage readily yield CO1 sequences.

7. Benefits of DNA barcoding

DNA barcoding is of great utility to users of taxonomy. It provides more rapid progress then the traditional taxonomic work (Gregory, 2005). DNA barcoding allows taxonomists to rapidly sort specimens by highlighting divergent taxa that may represent new species. DNA barcoding offers taxonomists the opportunity to greatly expand, and eventually complete, a global inventory of life’s diversity. The advocates of DNA barcoding say that it has revitalizing biological collections and speed up species identification and inventories (Gregory, 2005; Schindel and Miller, 2005); however the opponents argue that it will destroy traditional systematics and turn it into a service industry (Ebach and Holdrege, 2005; Seberg et al., 2003). Once fully developed, DNA barcoding will have the potential to completely revolutionize our knowledge of diversity of living organisms and our relationship to nature. By harnessing technological advances in electronics and genetics, DNA barcoding will help many people to quickly and cheaply recognize known species and retrieve information about them, and will speed discovery of thousands of species yet to be named. Barcoding has the potential to provide a vital new tool for appreciating and managing the Earth’s immense biodiversity.

The urgency of creating tissue banks has been well recognized (Savolainen and Reeves, 2004; Lorenz et al., 2005), and solutions for linking DNA samples with taxonomic vouchers are being developed for all sorts of organisms. Barcoding of life will have to be both integrative and integrated with other taxonomic initiatives such as the Global Taxonomic Initiative of the Convention on Biological Diversity (www.biodiv.org), and the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (www.gbif.org). Finally, by barcoding of life, ‘Life Barcoders’ will identify species linked via the World Wide Web to other kinds of biodiversity data such as images, usage and conservation status.

Despite some drawbacks of using DNA barcoding, the reported success of using the barcoding region in distinguishing species from a range of taxa and to reveal cryptic species is remarkable. However, it is known that species identification based on a single DNA sequence will always produce some erroneous results. Efforts should therefore be made to develop nuclear barcodes to complement the barcoding region that is currently in use. As the advantages and limitations of barcoding become apparent, it is clear that taxonomic approaches integrating DNA sequencing, morphology and ecological studies will achieve maximum efficiency at species identification (Dasmahapatra and Mallet, 2006).

The main reasons of DNA barcoding are (a) DNA barcode works with fragments, (b) DNA barcode works for all stages of life, (c) DNA barcoding unmasks those species which look-alikes, (d) DNA barcoding reduces ambiguity, (e) DNA barcoding makes expertise to speed up the identification of known organisms and also facilitate rapid recognition of new species, (f) DNA barcoding facilitates democratizes access i.e. a standardized library of barcodes will empower many more people to call by name the species around them as well as it will make possible identification of species whether abundant or rare, native or invasive, engendering appreciation of biodiversity locally and globally, (g) DNA barcoding sprouts new leaves on the tree of life, (h) DNA barcoding demonstrates value of specimens collections, (i) DNA barcoding speeds writing the encyclopedia of life, and (j) barcoding links biological identification to advancing frontiers in DNA sequencing, miniaturization in electronics, computerized information storage, and these integrating will lead to portable desktop devices and ultimately to hand-held barcoders; however, promoting technology development of portable devices for field use will be a major goal of this initiative (http://barcoding.si.edu/PDF/TenReasonsBarcoding.pdf).

Although DNA sequence data and barcoding are well on the way to being accepted as the global standard for species identification; however, such development is still limited in use. With the rich biological resources in many developing countries and many excellent taxonomists who are intimately familiar with the regional flora and interesting systematic questions, more plant DNA barcoding and molecular systematic and studies by colleagues from developing countries should advance our understanding of the tree of life at the global scale and offer opportunities to address many new evolutionary questions as well. Plant DNA barcoding and molecular systematic research require more equipment for data collection and analysis. It is technically more expensive than the classical, morphological and anatomical studies, but perhaps affordable. There is need to harness the mountains of DNA data being generated in modern laboratories and also to use the data from deep morphology in systematic (Ali and Choudhary, 2011; Wen and Pandey, 2005).

7.1. Plant systematics

DNA sequence data and barcoding are well on the way to being accepted as the global standard for species identification (Ali and Choudhary, 2011). DNA barcodes are likely to play a major role in the future of taxonomy. The build-up of DNA databases has great potential for the identification and classification of organisms and for supporting ecological and biodiversity research programs (Tautz et al., 2003). As a uniform, practical method for species identification, it appears to have broad scientific applications. DNA-based identification of species offers enormous potential for the biological scientific community, educators, and the interested general public. It will help open the treasury of biological knowledge and increase community interest in conservation biology and understanding of evolution.

The direct benefits of DNA barcoding are to make the outputs of systematics available to a large number of end-users by providing standardized and high-tech identification tools, e.g. for biomedicine (parasites and vectors), agriculture (pests), environmental assays and customs (trade in endangered species). The future perspective of DNA barcoding will be to provide a bio-literacy tool for the general public and it will also help in opening to the treasury of biological knowledge, which is currently underused partly because of the weak taxonomic expertise for species identification. DNA barcoding will also relieve the enormous burden of identifications of taxonomists, so they can focus on more pertinent to discovering and describing the new species. The most important aspect of DNA barcoding is that it will facilitate basic biodiversity inventories (Savolainen et al., 2005; Lahaye et al., 2008).

DNA barcoding can be likened to aerial photography, in that it provides an efficient method for mapping the extant species, though in sample space rather than physical space. The “aerial map” of DNA barcodes will help investigators explore the biological world and make full use of the enormous knowledge that has been built on 250 years of classical taxonomy. As sequencing costs decrease, DNA-based species identification will become available to an increasingly wide scientific community. When costs are low enough, researchers, teachers and naturalists will be able to use DNA barcoding in depth for examination of local ecosystems. As DNA barcodes are applicable to all life stages, it is also useful in cases where e.g. larval stages are difficult to identify with traditional methods of butterflies (Janzen et al., 2005) or amphibians (Vences et al., 2005), and insects in which several casts have different ‘unrelated’ morphologies (Smith et al., 2005). However, DNA barcoding is applied only in conjunction with classical approaches based on morphology.

7.2. Medicinal and wild plants’ identification

One of the most important uses of the DNA barcoding is in the medicinal plant authentication. Recently ITS, trnH-psbA, rbcL, matK and trnL–trnF gene sequences have successfully been used for DNA barcoding of several plant species, such as ITS [Achyranthes bidentata (Wang et al., 2004), Aconitum species (Luo and Yang, 2008; Zhang et al., 2010b), Adenophora lobophylla (Ge et al., 1997), Alpinia (Zhao et al., 2000), Alpinia galangal (Zhao et al., 2001), Alpinia oxyphylla (Zhao et al., 2000), Amomum species (Pan et al., 2001; Zhou et al., 2002), Angelica sinensis (Ji et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2003; Zhao et al., 2006), Aquilaria sinensis (Shen et al., 2008; Niu et al., 2010), Arctium lappa (Liu et al., 2010), Astragalus species (Dong et al., 2003), Atractylodes species (Shiba et al., 2006), Bupleurum species (Xie et al., 2006; Yang et al., 2007; Xie et al., 2009), Changium smyrnioides (Tao et al., 2008), Chuanminshen violaceum (Tao et al., 2008), Citrus medica var. sarcodactylis (Gao et al., 2007), Cnidium monnieri (Cai et al., 2000), Codonopsis tangshen (Luo et al., 2010), Crocus sativus (Mao et al., 2007; Che et al., 2007), Cynanchum species (Zhang et al., 2010a); Dendrobium chrysanthum (Xu et al., 2001), Dendrobium nobile (Ge et al., 2008), Dendrobium officinale (Ding et al., 2002a), Dendrobium species (Lau et al., 2001; Ding et al., 2002a,b,c; Xu et al., 2006), Dioscorea species (Wang et al., 2007), Ephedra species (Guo et al., 2006), Eucommia ulmoides (Ma et al., 2004), Euphorbia species (Jiang et al., 2005), Gentiana dahurica (Ji et al., 2003b), Gynostemma pentaphyllum (Jiang et al., 2009), Hedyotis diffusa (Hao et al., 2004; Liu and Hao, 2005), Hypericum perforatum (Howard et al., 2009), Ligusticum chuanxiong (Liu et al., 2002), Liriope species (Huang et al., 2009), Lycium barbarum (Shi et al., 2008), Mitragyna speciosa (Sukrong et al., 2007), Morinda officinalis (Ding and Fang, 2005), Nelumbo nucifera (Lin et al., 2007), Ophiopogon japonicus (Huang et al., 2009), Panax ginseng (Ma et al., 2000), Panax species (Ngan et al., 1999), Polygonum multiflorum (Zhang and Shi, 2007), Polygonum tinctorium (Song et al., 2009), Pseudostellaria heterophylla (Yu et al., 2003; Zhu et al., 2007), Pueraria species (Zeng et al., 2003; Sun et al., 2007), Rheum palmatum (Zhang et al., 2003; Ji et al., 2003a), Rhodiola alsia (Gao et al., 2009), Salvia miltiorrhiza (Wang and Wang, 2005), Saussurea lappa (Chen et al., 2008), Saussurea medusa (Liu et al., 2001b), Schisandra chinensis (Gao et al., 2003), Stellaria media (Zhao et al., 2009), Stemona tuberose (Jiang et al., 2006), Swertia mussotii (Liu et al., 2001a), Tripterygium wilfordii (Law et al., 2010), Verbena officinalis (Ruzicka et al., 2009)], trnH-psbA [Aristolochia species (Li et al., 2010), Artemisia species (Liu and Ji, 2009), Citrus grandis (Su et al., 2010), Dendrobium species (Yao et al., 2009), Paris species (Yang et al., 2010), Sabia parviflora (Sui et al., 2010), Species in Polygonaceae (Song et al., 2009), Stemona tuberosa (Vongsak et al., 2008)], rbcL [Arisaema species (Kondo et al., 1998), Belamcanda chinensis (Qin et al., 2003), Cnidium officinale (Kondo et al., 1996), Dendrobium species (Asahina et al., 2010), Dryopteris crassirhizoma (Zhao et al., 2007), Glycyrrhiza species (Hayashi et al., 1998, 2000, 2005), Sabia parviflora (Sui et al., 2010), Species in Polygonaceae (Song et al., 2009)], matK [Cnidium monnieri (Cao et al., 2001), Cnidium officinale (Liu et al., 2002), Dendrobium species (Teng et al., 2002; Asahina et al., 2010), Ligusticum chuanxiong (Liu et al., 2002), Panax notoginseng (Fushimi et al., 2000; Zhang et al., 2006), Panax species (Zhu et al., 2003), Panax vietnamensis (Komatsu et al., 2001), Polygonum multiflorum (Yan et al., 2008), Rheum species (Yang et al., 2004), Sabia parviflora (Sui et al., 2010)], and trnL–trnF [Adenophora species (Zhao et al., 2003), Angelica acutiloba (Mizukami et al., 1997), Angelica species (Mizukami, 1995), Atractylodes species (Ge et al., 2007), Cinnamomum species (Kojoma et al., 2002), Epimedium species (Sun et al., 2004), Fritillaria species (Cai et al., 1999), Lonicera japonica (Li et al., 2001), Pueraria species (Sun et al., 2007), Saussurea lappa (Chen et al., 2008), Stellaria media (Zhao et al., 2009), Swertia mussotii (Yu et al., 2008), Tripterygium wilfordii (Law et al., 2010)].

In addition with the above, Chen et al. (2010) tested the discrimination ability of ITS2 in more than 6600 plant samples belonging to 4800 species from 753 distinct genera (see the link for reference: http://www.plosone.org/article/fetchSingleRepresentation.action?uri=info:doi/10.1371/journal.pone.0008613.s008) and found that the rate of successful identification with the ITS2 was 92.7% at the species level. Yao et al. (2010) also evaluated 50,790 plant and 12,221 animal (see the link for reference: http://www.plosone.org/article/fetchSingleRepresentation.action?uri=info:doi/10.1371/journal.pone.0013102.s006) ITS2 sequences downloaded from GenBank, and proposed that the ITS2 locus should be used as a universal DNA barcode for identifying plant species and as a complementary locus for CO1 to identify animal species.

7.3. Food safety and conservation biology

Sustainable utilization of plant genetic resources is essential to meet the demand for future food and health security. Molecular markers are increasingly used for screening of germplasm to study genetic diversity, identify redundancies in the collections (Rao, 2004). Despite the tradition of systematic biology as the science of diversity, systematics has until recently contributed relatively little to the theory and practice of conservation biology. The four areas in which systematics could contribute to the conservation of rare plant species are: (i) species concepts, (ii) the identification of lineages worthy of conservation, (iii) the setting of conservation priorities, and (iv) the effects of hybridization on the biology and conservation of rare species. Species concepts that incorporate history and reflect phylogeny ultimately are more useful for preserving biodiversity. Phylogenetic analyses involving conspecific populations often reveal multiple lineages that may warrant protection as evolutionarily distinct units. Phylogenetic information provides the tools for inferring relationships among organisms and, in conjunction with biogeography, for identifying those areas that harbor many actively speciation groups. Hybridization may lead to the extinction of a rare species, but in other cases, ironically, artificial hybridization with a more widespread congener may be the only way to preserve the gene pool of a rare species (Soltis and Gitzendanner, 1999).

A common problem with raw drug trade has been the admixtures with morphologically allied and geographically co-occurring species (Nair et al., 1983; Bisset, 1984; Sunita, 1992; Khatoon et al., 2006; Mitra and Kannan, 2007). Over 80% of the medicinal plants for raw drug trade are predominantly collected from the wild by local farmers or collectors, who often rely only on their experience in identifying the species being collected. Services of specialists like taxonomists are rarely availed for authentication. Thus, it is not uncommon to find admixtures of related/allied species and infrequently also for unrelated genera. Among the reasons attributed for species admixtures are the apparent confusion in vernacular names between indigenous systems of medicine and local dialects, non availability of authentic plant, similarity in morphological features, etc. (Mitra and Kannan, 2007). The possibility of admixtures is particularly high when the species in question co-occurs with morphologically similar species. Frequently, admixtures could also be deliberate due to adulteration (Mitra and Kannan, 2007). The consequences of species admixtures can range from reducing the efficacy of the drug to lowering the trade value (Wieniawski, 2001; Song et al., 2009). Efforts have been made to accurately identify medicinal plants (Jayasinghe et al., 2009). Besides conventional methods including examination of wood anatomy and morpho-taxonomical keys, several-DNA-based methods have been developed to resolve these problems (Sucher and Carles, 2008). With the advent of DNA barcode tools, attempts are being made to use several candidate barcode regions to identify species discussed above.

8. Limitations of DNA barcoding

DNA-based species identification depends on distinguishing intraspecific from interspecific genetic variation. The ranges of these types of variation are unknown and may differ between taxa. It may be difficult to resolve recently diverged species or new species that have arisen through hybridization. There is no universal gene for DNA barcoding, no single gene that is conserved in all domains of life and exhibits enough sequence divergence for species discrimination. The validity of DNA barcoding therefore depends on establishing reference sequences from taxonomically confirmed specimens. This is likely to be a complex process that will involve cooperation among a diverse group of scientists and institutions. Barcode sequences are, in general, short (approx. 500–1000 bp) and this fundamentally limits their utility in resolving deep branches (between orders or phyla) in phylogenies. Some controversy exists over the value of DNA barcoding, largely because of the perception that this new identification method would diminish rather than enhance traditional morphology-based taxonomy, and species determinations based solely on the genetic divergence could result in incorrect species recognition (Schindel and Miller, 2005). However, we must keep open the possibility that the barcode sequences per se and their ever-increasing taxonomic coverage could become an unprecedented resource for taxonomy, systematic and diagnosis (Kress et al., 2005; Chase et al., 2005, 2007), and may be equally useful (Monaghan et al., 2005).

9. Conclusions

In conclusion, the classical way of practice of plant taxonomy for the identification of species lead the discipline many a times to a subject of opinion; the plant DNA barcoding is now transitioning the epitome of species identification.

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Saud University for funding the work through the research group project No. RGP-VPP-195. The research was funded in part by the project Excellence in Faculty Support-Research, Centre of Excellence 17586-4/2013/TUDPOL, Hungary. The technical assistance of Sabiha Ali Ajmal is highly appreciated.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Contributor Information

M. Ajmal Ali, Email: alimohammad@ksu.edu.sa.

Gábor Gyulai, Email: Gyulai.Gabor@mkk.szie.hu.

Norbert Hidvégi, Email: Hidvegi.Norbert@mkk.szie.hu.

Balázs Kerti, Email: Kerti.Balasz@mkk.szie.hu.

Fahad M.A. Al Hemaid, Email: fhemaid@ksu.edu.sa.

Arun K. Pandey, Email: arunpandey79@gmail.com.

Joongku Lee, Email: joongku@kribb.re.kr.

References

- Ackerfield J.R., Wen J. Evolution of Hedera (the ivy genus, Araliaceae): insights from chloroplast DNA data. Int. J. Plant Sci. 2003;164:593–602. [Google Scholar]

- Ali M.A., Choudhary R.K. India needs more plant taxonomists. Nature. 2011;471(7336) doi: 10.1038/471037d. 37-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali M.A., Lee J., Kim S.Y., Al-Hemaid F.M.A. Molecular phylogenetic study of Cardamine amaraeformis Nakai using nuclear and chloroplast DNA markers. Genet. Mol. Res. 2012;11(3):3086–3090. doi: 10.4238/2012.August.31.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali M.A., Al-Hemaid F.M.A., Choudhary R.K., Lee J., Kim S.Y., Rub M.A. Status of Reseda pentagyna Abdallah & A.G. Miller (Resedaceae) inferred from analysis of combined nuclear ribosomal and chloroplast sequence data. Bangladesh J. Plant Taxon. 2013;20(2):233–238. [Google Scholar]

- Altschul S.F., Madden T.L., Schäffer A.A., Zhang J., Zhang Z., Miller W., Lipmanm D.J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25(17):3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alverson A.J., Wei X., Rice D.W., Stern D.B., Barry K., Palmer J.D. Insights into the evolution of mitochondrial genome size from complete sequences of Citrullus lanatus and Cucurbita pepo (Cucurbitaceae) Mol. Biol. Evol. 2010;27(6):1436–1448. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msq029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzohairy A.M., Gyulai G., Jansen R.K., Bahieldin A. Transposable elements domesticated and neofunctionalized by eukaryotic genomes. Plasmid. 2013;69:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzohairy A.M., Yousef M.A., Edris S., Kerti B., Gyulai G., Bahieldin A. Detection of LTR Retrotransposons reactivation induced by in vitro environmental stresses in barley (Hordeum vulgare) via RT-qPCR. Life Sci. J. 2012;9:5019–5026. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson L., Rova J.H.E. The rps16 intron and the phylogeny of the Rubioideae (Rubiaceae) Plant Syst. Evol. 1999;214:161–186. [Google Scholar]

- Angiosperm Phylogeny Group, APGI, 1998. An ordinal classification for the families of flowering plants. Ann. Miss. Bot. Gard. 85, 531–553.

- Angiosperm Phylogeny Group, APGII, 2003. An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG II. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 141, 399–436.

- Angiosperm Phylogeny Group, APGIII, 2009. An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG III. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 161, 105–121.

- Ansorge W.J. Next-generation DNA sequencing techniques. New Biotechnol. 2009;25(4):195–203. doi: 10.1016/j.nbt.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong K.F., Ball S.L. DNA barcodes for biosecurity: invasive species identification. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2005;360(1462):1813–1823. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2005.1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asahina H., Shinozaki J., Masuda K., Morimitsu Y., Satake M. Identification of medicinal Dendrobium species by phylogenetic analyses using matK and rbcL sequences. J. Nat. Med. 2010;64:133–138. doi: 10.1007/s11418-009-0379-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asmussen C.B., Chase M.W. Coding and noncoding plastid DNA in palm systematics. Am. J. Bot. 2001;88:1103–1117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avise J.C. Chapman & Hall; New York: 1994. Molecular Markers, Natural History and Evolution. [Google Scholar]

- Baker W.J., Asmussen C.B., Barrow S., Dransfield J., Hedderson T.A. A phylogenetic study of the palm family (Palmae) based on chloroplast DNA sequences from the trnL–trnF region. Plant Syst. Evol. 1999;219:111–126. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin B.G. Phylogenetic utility of the internal transcribed spacers of nuclear ribosomal DNA in plants: an example from the Compositae. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 1992;1:3–16. doi: 10.1016/1055-7903(92)90030-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin B.G., Markos S. Phylogenetic utility of the external transcribed spacer (ETS) of 18S–26S nrDNA: congruence of ETS and ITS trees of Calycadenia (Compositae) Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 1998;10:449–463. doi: 10.1006/mpev.1998.0545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin B.G., Sanderson M.J., Porter J.M., Wojciechowski M.F., Campbell C.S., Donoghue M.J. The ITS region of nuclear ribosomal DNA: a valuable source of evidence on angiosperm phylogeny. Ann. Miss. Bot. Gard. 1995;82:247–277. [Google Scholar]

- Baum D.A., Small R.L., Wendel J.F. Biogeography and floral evolution of baobabs (Adansonia, Bombacaceae) as inferred from multiple data sets. Syst. Biol. 1998;47:181–207. doi: 10.1080/106351598260879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besansky N.J., Severson D.W., Ferdig M.T. DNA barcoding of parasites and invertebrate disease vectors: what you don’t know can hurt you. Trends Parasitol. 2003;19:545–546. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2003.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhargava M., Sharma A. DNA barcoding in plants: evolution and applications of in silico approaches and resources. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2013;67(3):631–641. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienert F., De Danieli S., Miquel C., Coissac E., Poillot, Brun J.J., Taberlet P. Tracking earthworm communities from soil DNA. Mol. Ecol. 2012;21:2017–2030. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisset W.G. CRC Press; London: 1984. Herbal Drugs and Phytopharmaceuticals. [Google Scholar]

- Blaxter M. Counting angels with DNA. Nature. 2003;421:122–124. doi: 10.1038/421122a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaxter M., Elsworth B., Daub J. DNA taxonomy of a neglected animal phylum: an unexpected diversity of tardigrades. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2004;271:189–192. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2003.0130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckler E.S., Ippolito A., Holtsford T.P. The evolution of ribosomal DNA: divergent paralogues and phylogenetic implications. Genetics. 1997;145:821–832. doi: 10.1093/genetics/145.3.821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bult C.J., Sweere J.A., Zimmer E.A. Cryptic sequence simplicity, nucleotide composition bias, and molecular coevolution in the large subunit of ribosomal DNA in plants: implications for phylogenetic analyses. Ann. Miss. Bot. Gard. 1995;82:235–246. [Google Scholar]

- Cai J.N., Zhou K.Y., Xu L.S., Wang Z.T., Shen X., Wang Y.Q., Li X.B. Ribosomal DNA ITS sequence analyses of Cnidium monnieri from different geographical origin in China. Acta Pharm. Sin. 2000;35:56–59. [Google Scholar]