Abstract

MiRNAs regulate gene expression by binding predominantly to the 3′UTR of target transcripts to prevent their translation and/or induce target degradation. In addition to the more than 1200 human miRNAs, human DNA tumorviruses such as Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) encode miRNAs. Target predictions indicate that each miRNA targets hundreds of transcripts, many of which are regulated by multiple miRNAs. Thus, target identification is a big challenge for the field. Most methods used to date investigate single miRNA-target interactions and are not able to analyze complex miRNA-target networks. To overcome these challenges, cross-linking and immunoprecipitation (CLIP), a recently developed method to study direct RNA-protein interactions in living cells, was successfully applied to miRNA target analysis. It utilizes Argonaute (Ago)-immunoprecipitation to isolate native Ago-miRNA-mRNA complexes. In four recent publications two variants of the CLIP method (HITS-CLIP and PAR-CLIP) were utilized to determine the targetomes of human and viral miRNAs in cells infected with the gamma-herpesviruses KSHV and EBV that are associated with a number of human cancers. Here, we briefly introduce herpesvirus-encoded miRNAs and then focus on how CLIP technology has largely impacted our understanding of viral miRNAs in viral biology and pathogenesis.

I. MiRNA-mediated Regulation of Gene Expression

The first miRNA, lin-4, was discovered in 1993 in C. elegans as a small RNA regulating the expression of the lin-14 gene1. MiRNA-mediated regulation of gene expression was at first believed to be a nematode-specific phenomenon. This changed in 2000 with the discovery of let-72, which was soon after found to be conserved across species3, and triggered the search for more miRNA-encoding genes. Since then the number of miRNAs registered at miRBase4, 5 has risen to more than 18,000 entries (release 18, Nov. 2011). MiRNAs are short (21-23 nt), non-coding RNAs that bind to partially complementary sequences mostly in the 3′UTR of target transcripts to inhibit their translation and/or induce their degradation. The majority of miRNAs are processed from larger, capped and poly-adenylated RNA pol II transcripts as part of a 70-80 nt RNA stem-loop, the primary (pri)-miRNA. However, some gamma-herpesviral and a recently reported retroviral miRNA are processed from pol III transcripts6, 7. The pri-miRNA is cleaved in the nucleus by Drosha/DGCR8. This liberates a shorter stem-loop, the pre-miRNA, which is then exported into the cytoplasm by Exportin/Ran-GTP, where it is cleaved by Dicer, resulting in a 21-23 nt RNA duplex. Usually only one strand, the guide strand, is incorporated into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) to accomplish the silencing function, while the other strand (passenger strand) is degraded. In contrast to siRNAs, miRNAs in most cases are only partially complementary to their targets. MiRNA target specificity is predominantly determined by the seed sequence, which comprises 7-8 nt at the miRNA 5′ end that are fully complementary to the target8-10. Seed pairing can be supplemented by base pairing interactions at the 3′end of the miRNA10. Moreover, Shin et al. showed a new class of miRNAs lacking perfect seed and 3′ end pairing and binding instead with 11-12 central nucleotides11, while Chi et al. describe miRNAs binding with a G-bulge in the mRNA opposite to miRNA position five and six12.

A major component of RISC is the Argonaute (Ago) protein. In mammalian cells there are four Ago proteins that are all incorporated into RISC, however, only Ago2 has endocuclease activity to cleave the target transcript13. Ago proteins contain two RNA-binding domains, the PAZ domain binding the 3′ end of the mature miRNA and the PIWI domain interacting with the 5′ end. Together they position the miRNA for target interaction (reviewed by Yang et al.14). In the case of full-length complementarity between miRNA and mRNA, miRNAs have a siRNA-like function leading to direct cleavage of the mRNA by Ago2. This mode of action dominates in plants15, but is very rare in animals. Here, miRNAs predominantly function by inhibiting protein translation (reviewed by Fabian & Sonenberg16)

It is still a matter of debate, however, what the mechanism of translational repression is. Several studies involving micro-array experiments showed a decrease in transcript levels in response to miRNA targeting. This occurs via deadenylation of the targeted mRNA, which leads to decapping, initiating standard mRNA turnover processes17-19. However, the effects on mRNA levels are usually modest, feeding the idea that repression must be based on translational inhibition, which is supported by a few studies showing that RISC binding interferes with translation initiation (reviewed by Fabian et al.20). These are challenged, on the other hand, by recent high-throughput approaches indicating that for the majority of targets with decreased protein levels also the mRNA levels are reduced21-23.

Animal miRNAs predominantly bind to the 3′UTR of mRNAs. Increasing evidence shows that miRNAs can also function in CDS (e.g.24-27). The latter target sites, however, although functional, usually are less effective than 3′UTR target sites21, 22, 28, 29. Interestingly, target sites for the same miRNA in the 3′UTR and CDS of a transcript can have synergistic effects29. Although miRNA-induced changes in transcript levels are mostly moderate (1.5-2 fold), a recent very elegant paper showed that small changes in transcript levels can lead to large changes in protein levels if a certain threshold is crossed30.

II. Herpesviruses and Viral Mirnas

MiRNAs have been identified in many eukaryotes, from single cell organisms like algae and amoebae to organisms all across the metazoa (miRBase), and in 2004 the first virally-encoded miRNAs were also discovered in the herpesvirus Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)31. Since then more than 200 mature miRNAs have been identified in all herpesviruses analyzed so far, except for Varicella Zoster virus (for review see32, 33). Herpesviruses are double-stranded DNA viruses, which are categorized into three subfamilies: Alpha-, Beta-, and Gammaherpesvirinae. To date, three human alpha-, three beta-, and two gammaherpesviruses are known. Typical for herpesviruses is their ability to establish lifelong latent infections in the host. For this the virus needs to remain hidden from the host immune surveillance, which is achieved by very limited viral gene expression together with the downregulation of or interference with the host innate immune defense mechanisms34. During latency the viral genome persists as a circular episome that in dividing cells is replicated by the host cell replication machinery upon cell division. Certain triggers such as inflammation can cause the reactivation of the virus into the lytic cycle, which leads to replication of the viral DNA and production of progeny virus. For two human gammaherpesviruses latent infection can be associated with tumorigenesis: Kaposi's Sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) is the etiological agent of Kaposi's sarcoma (KS), primary effusion lymphoma (PEL), and a subset of multicentric Castleman's disease (MCD), while EBV causes Burkitt's lymphomas (BL), non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, and nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) (reviewed by Wen et al.35). In contrast, the pathogenesis of human alpha- and beta-herpesviruses is due to the lytic life cycle, which is characterized by uncontrolled viral replication. The subsequent immune responses result in tissue destruction, such as in the case of the encephalitis caused by herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1).

In many herpesviruses (e.g. EBV, KSHV, Rhesus rhadinovirus (RRV), HSV, and Marek's disease virus (MDV)) the viral miRNAs are expressed as part of the latency program32, implying a function in the maintenance of latency. This could indeed be confirmed for HSV-1 and -2, where several miRNAs are expressed as part of the latency-associated transcript (LAT), a long non-coding RNA that is transcribed antisense to lytic genes. Based on their antisense position several miRNAs were predicted to target immediate early lytic genes, which could be experimentally confirmed for ICP0 (HSV-1 and -2) and ICP34.5 (HSV-2)36, 37. Umbach et al. identified an additional miRNA in HSV-1 located in a different transcript downstream of LAT. This miRNA was experimentally confirmed to decrease protein levels of ICP436, the major viral transactivator required for reactivation and productive infection. Also in KSHV it could be shown that two viral miRNAs target the major lytic transactivator, RTA38, 39, while several EBV miRNAs target the viral oncoprotein LMP1, which is responsible for transformation40.

Most viral miRNA targets identified thus far, however, are cellular transcripts. Although until recently the number of experimentally confirmed targets was very low, they nevertheless clearly indicated a role of viral miRNAs in cellular pathways critical for the herpesvirus life cycle. Major themes are the targeting of pro-apoptotic genes such as PUMA (EBV41), SMAD2 (MDV142), THBS1 (KSHV43), TWEAKR (KSHV44), and CASP3 (KSHV45) and genes involved in immune evasion, such as CXCL16 (Mouse cytomegalovirus, mCMV46), CXCL11 (EBV47), and MICB (Table 1). Interestingly, despite the rather limited sequence conservation between herpesviral miRNAs, they display astonishing functional conservation. MiRNAs from three different viruses, Human cytomegalovirus (hCMV), EBV, and KSHV, target MICB48, 49, which is involved in the antiviral natural killer (NK) cell response. Other viral miRNA targets are involved in angiogenesis, cell cycle control, and endothelial cell differentiation. A comprehensive list of validated targets and their presumable functions is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Cellular targets of Herpesvirus miRNAs.

| Cellular target | Virus/sub-family | miRNA | (Proposed) functional consequences | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BACH1 | KSHV/γ | miR-K11 | Pro-proliferative, increased viability under oxidative stress | 101 102 106 |

| BCLAF1 | KSHV/γ | Inhibit caspase activity, facilitate lytic reactivation | 64 | |

| CASP3 | KSHV/γ | miR-K1, -K3, -K4-3p | Inhibition of apoptosis | 45 |

| CDKN1A/p21 | KSHV/γ | miR-K1 | release of cell cycle arrest | 101 |

| C/EBPbeta, C/EBPbeta p20 | KSHV/γ | miR-K11 miR-K3, -K7, |

De-repression of IL6/IL10 secretion; Modulation of macrophage cytokine response |

103 98 |

| IKBKE | KSHV/γ | miR-K11 | Suppression of antiviral immunity via IFN signaling | 97 101 |

| IRAK1 | KSHV/γ | miR-K9 | Decreased activity of TLR/IL1R signaling cascade | 99 |

| MAF1 | KSHV/γ | miR-K1, -K6-5p, -K11 | Induce endothelial cell reprogramming | 107 |

| MICB | KSHV/γ | miR-K7 | Immune evasion | 49 |

| MYD88 | KSHV/γ | miR-K5 | Decreased activity of TLR/IL1R signaling cascade | 99 |

| NFIB | KSHV/γ | miR-K3 | Promote latency | 108 |

| NFKBIA | KSHV/γ | miR-K1 | Promote latency | 109 |

| RBL2 | KSHV/γ | miR-K4-5p | De-repression of DNA methyl transferases (DNMT1, 3a, 3b) | 39 |

| SMAD5 | KSHV/γ | miR-K11 | Resistence to growth inhibitory effects | 100 |

| TGFBRII | KSHV/γ | miR-K10a, -K10b | Resistence to growth inhibitory effects | 110 |

| THBS1 | KSHV/γ | miR-K1, -K3-3p, -K6-3p, -K11 | Pro-angiogenic | 43 |

| TNFRSF10B/TWEAKR | KSHV/γ | miR-K10a | Reduced induction of inflammatory response and apoptosis | 44 |

| CXCL-11 | EBV/γ | miR-BHRF1-3 | Immune modulation | 47 |

| Dicer | EBV/γ | miR-BART6 | Global reduction of miRNA synthesis | 111 |

| MICB | EBV/γ | miR-BART2-5p | Immune evasion | 49 |

| PUMA | EBV/γ | miR-BART5 | Anti-apoptotic | 41 |

| CCNE2 | hCMV/β | miR-US25-1 | Block cell cycle to allow DNA replication, desensitize for apoptotic signals | 112 |

| MICB | hCMV/β | miR-UL112 | Immune evasion | 48 |

| CXCL16 | mCMV/β | miR-M23-2 | Immune evasion | 46 |

| C/EBPbeta | MDV1/α | miR-M4-5p | 113 | |

| c-Myb | MDV1/α | miR-M4-5p | Hematopoiesis | 113 |

| GPM6B | MDV1/α | miR-M4-5p | 113 | |

| MAP3K7IP2 | MDV1/α | miR-M4-5p | Repression of NFkappaB induction via IL-1 | 113 |

| PU.1 | MDV1/α | miR-M4-5p | 113 114 | |

| RREB1 | MDV1/α | miR-M4-5p | Lymphocyte differentiation | 113 |

| SMAD2 | MDV1/α | miR-M3 | Cell survival | 42 |

Listed are all targets that have been functionally confirmed at least by luciferase reporter repression upon ectopic miRNA expression, and de-repression of the reporter upon target site mutation; KSHV = Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus, EBV = Epstein-Barr virus, hCMV = Human cytomegalovirus, mCMV = Mouse cytomegalovirus, MDV1 = Marek's disease virus

III. Tools For MiRNA Target Identification

Viral miRNAs provide a unique opportunity to examine miRNA function: they are not expressed in non-infected cells, thereby allowing to compare the cellular transcriptome and proteome in presence and absence of the miRNAs. Viral miRNAs are, with few exceptions, not sequence-related to the metazoan miRNAs. Thus, a target with a functional seed match for a viral miRNA can in most cases unequivocally be assigned to this miRNA. Finally, viruses encode only a limited number of miRNA genes (typically between 2 and 40), which simplifies the transcriptome-wide target analysis compared to the more than 1,200 human miRNAs5. Most of the targets described above have been identified by either one or a combination of mainly three strategies: bioinformatics target prediction, gene-specific experimental target verification, and expression profiling.

A. Bioinformatics Target Prediction

Numerous target prediction algorithms have been developed in the last 10 years9, 50-57. Target prediction is complicated by the incomplete complementarity between a miRNA and its target and the still poorly understood rules of target recognition. Therefore, most algorithms are based on target binding via the seed sequence (nt 2-8) of the miRNA, the so far best characterized target recognition mechanism. Some programs additionally take supporting base pairing interactions, e.g. at the miRNA 3′ end, the overall thermodynamic stability of the miRNA/mRNA duplex, and evolutionary conservation into account. However, there are pronounced differences in the prediction results obtained by the different programs, reflecting in part the use of different sources for the 3′UTR sequences (Targetscan9, Miranda54), but also the high false positive rate (with estimates going up to 70%21, 22, 58-60) due to the high statistical probability with which a 7-mer sequence occurs in the genome. Considering only evolutionary conserved seed matches strongly enhances performance21, 22, but is not applicable for viral miRNA target prediction due to the lack of conservation even among closely related viruses. Additionally, current predictions mostly don't incorporate new findings such as alternative targeting strategies, or the existence of functional target sites beyond those in the 3′UTR, i.e. in protein encoding regions and even 5′UTRs, which leads to false-negative predictions. Thus bioinformatics target prediction provides a useful start, especially if nothing is known about potential targets of a miRNA, but always needs experimental follow-up.

B. Target Identification by Luciferase Reporter Assay, Quantitative RT-PCR, and Western Blot

The most commonly used approaches to experimentally validate a specific miRNA-target interaction are luciferase reporter assay, quantitative RT-PCR, and western blot. While the latter two measure downstream effects of miRNA expression without being able to distinguish between direct and indirect effects, the luciferase reporter assay reports direct miRNA-target interactions. They are based on cloning a 3′UTR with a potential miRNA target site downstream of a luciferase reporter gene. The reporter vector is transiently transfected into cells together with a miRNA expression vector or synthetic miRNA mimics, and the luciferase levels are determined in presence and absence of the miRNA. In case of a direct target effect, mutation of the seed match site in the 3′UTR should abolish the reporter repression through the miRNA. These data can be further backed up by western blot to visualize the effect on the corresponding protein product. However, all three assays study at best very few targets at a time, which by far doesn't capture the capacity of a single miRNA to regulate a complex network of targets.

C. Target Identification by Transcriptome or Proteome Profiling

A more global experimental approach is gene expression profiling, which uses overexpression of a miRNA in a cell line and monitoring of changes in transcript levels by micro-array or high-throughput sequencing. Down-regulated genes often are enriched for seed matches of the overexpressed miRNA28, 61, which is an indication for direct targeting. Although evidence is accumulating that miRNA-mediated repression is mostly due to decreased transcript levels21-23, some targets seem to be predominantly repressed at the translational level62 and therefore missed by micro-array analysis. Recently, two groups performed high-throughput proteomics21, 22, and indeed found targets that showed no change on the mRNA level but decreased protein levels. However, the majority of their results showed that miRNA-mediated repression occurs via modest mRNA destabilization. A drawback of both approaches (transcriptome and proteome profiling) is that they observe downregulation of targets within a background of secondary effects, making it difficult to sort out true, direct targets. Although seed match enrichment can point in the right direction, theoretically every target identified by either of the two methods needs to be confirmed by luciferase reporter assays to show the direct miRNA-mRNA interaction.

A caveat of all the methods discussed above is the exogenous expression of miRNAs, which often results in expression above physiological levels, and frequently is introduced into a non-natural transcriptome background, thus potentially reporting non-physiological interactions or even artifacts due to overloading RISC with either overexpressed miRNAs or high concentrations of mimics. A reverse approach is the silencing of a miRNA by transfection of an antisense oligonucleotide (e.g. antagomirs63). This avoids miRNA overexpression effects. On the downside, however, this approach is only as specific as the antisense oligo, which can be a limiting factor especially when targeting a specific member of a miRNA family, resulting in off-target effects. An elegant tandem-array approach was utilized by Ziegelbauer et al., who combined overexpression and inhibition of miRNAs to stringently identify targets that were repressed in the presence of the mimic and de-repressed in the presence of the antagomir64.

IV. Identification of MiRNA Regulatory Networks by Cross-linking and Immunoprecipitation (CLIP)

A. The HITS-CLIP and PAR-CLIP Techniques

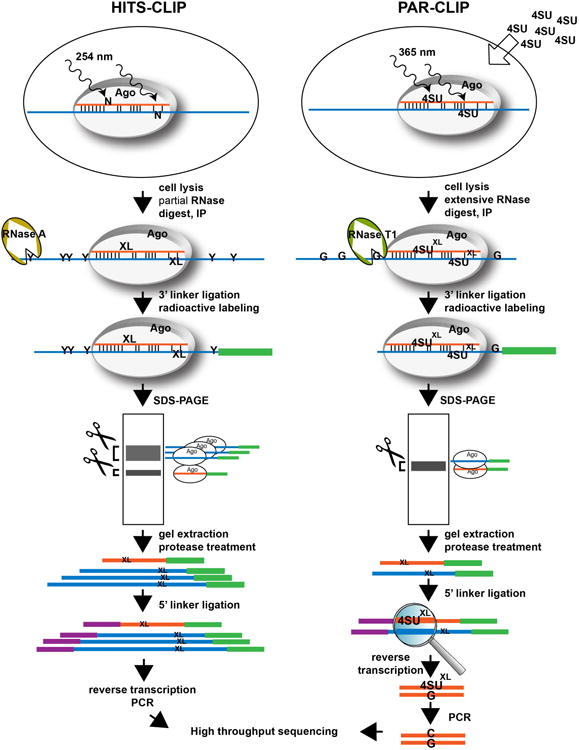

Two recently developed methods, high-throughput sequencing of RNA isolated by cross-linking immunoprecipitation (HITS-CLIP65) and Photoactivatable-Ribonucleoside-Enhanced Cross-linking and Immunoprecipitation (PAR-CLIP66), can – not completely but to a reasonable extent – address several of the issues discussed above. Both are based on UV cross-linking of RNA-protein complexes in living cells, followed by capturing of RISC complexes via Ago-immunoprecipitation. In brief, after cross-linking, (partial) RNase digest and immunoprecipitation, RISC complexes are further purified by SDS-PAGE. RNAs representing both miRNAs and their bound targets are extracted from the complexes of the correct migration size (i.e. desired length of cross-linked and clipped mRNA) and converted into small RNA libraries for high-throughput sequencing by adapter ligation and RT-PCR (Figure 1). Sequencing reads originating from Ago interactions with clipped mRNAs form narrow clusters of overlapping reads on transcripts after alignment to the reference genome. The clusters are usually enriched for seed matches of the most highly expressed miRNAs in the studied cell type65-67, especially within 20-30 nt upstream and downstream of the cluster peak position. This observation allowed to define the Ago footprint region to about 40 to 60 bases in length65.

Figure 1. Comparison of HITS-CLIP and PAR-CLIP experimental procedures.

RNA-protein cross-linking occurs in living cells. HITS-CLIP uses cross-linking at 254 nm, while in PAR-CLIP cells are fed with 4-Thiouridine (4SU), which is incorporated into nascent RNA and cross-links at 365 nm. Cross-linked cells are lysed and lysates are treated with RNase to trim the mRNA. In HITS-CLIP mRNAs are partially digested with RNase A, which cleaves after pyrimidines, leaving mRNAs with lengths between 50 and >100 bp. PAR-CLIP performs an extensive RNA digest with RNase T1, which cleaves after guanine nucleotides, resulting in very short mRNA fragments of 20-30 nt. After Ago-immunoprecipitation, linker ligation and radioactive labeling of the RNA, cross-linked Ago-miRNA-mRNA complexes are further purified by SDS-PAGE. HITS-CLIP yields two major bands, the Ago-miRNA complexes migrating at ∼100 kDa, and the Ago-mRNA and double cross-linked Ago-miRNA-mRNA complexes migrating at 120-130 kDa (corresponding to varying mRNA lengths between 50- and 80 bp). PAR-CLIP produces only one band at 100-110 kDa containing both RNA species. Complexes are cut out and RNAs are extracted and ligated to the 5′ linker. Reverse transcription and PCR amplification creates the final libraries for Illumina sequencing. In PAR-CLIP, the cross-linked 4SU base pairs with Guanosine instead of Adenosine during reverse transcription, resulting in a T to C transition in the final PCR product that allows identification of the crosslink site. N = any nucleotide; 4SU = 4-Thiouridine; G = Guanosine; Y = Pyrimidine; XL = symbolizes a cross-link position

The experimental setup of CLIP studies has major advantages over conventional Ago-IP protocols such as RIP-Chip46): (i) the cross-linking allows more stringent purification conditions, thus ensuring very limited carry-over of contaminations; and (ii) most importantly, while also in RIP-Chip-enriched transcripts can be screened for miRNA seed matches, they have to be searched over the entire transcript length, while in CLIP experiments the location of the seed-match is narrowed to the site of the Ago/miRNA/mRNA interaction, which adds specificity. Consequently, a high percentage of the HITS-CLIP or PAR-CLIP-predicted viral miRNA targets are confirmed in validation experiments68-70.

The major difference between HITS-CLIP and PAR-CLIP is the cross-linking technique. HITS-CLIP uses 254 nm UV light to cross-link RNA-protein complexes. As any of the 4 nucleotides is cross-linkable to amino acids (aa), there is a high chance for the presence of a favorably positioned nt-aa pair in each RNA binding protein (RBP)-target interaction. HITS-CLIP can thus be performed with any cell line or primary tissue without requiring pre-treatment. In contrast, in PAR-CLIP cells are first supplemented with the nucleoside analog 4-Thiouridine (4SU) that is incorporated into nascent mRNAs. 4SU cross-links are induced at 365 nm. Although cross-linking of 4SU is more efficient than that of the unmodified bases, it depends on the modified nucleotide being in a cross-linkable position (a 4SU must be in close distance to one of the reactive aa in the RNA binding pocket of Ago). Moreover, it can only be performed in cells lines, not in primary tissue samples. An important feature of PAR-CLIP, however, is a T to C transition of the cross-link site, since the cross-linked 4SU favors a U-G instead of a U-A base pair during reverse transcription66 (Figure 1), thus clearly labeling the Ago/RNA interaction site. Recent work from the Darnell lab demonstrated that 254 nm UV cross-linking as used in HITS-CLIP leads to single base deletions and transitions at the cross-link site during reverse transcription (although at a lower percentage than the T to C transitions in PAR-CLIP). While they are more complex to map during the bioinformatics analysis due to mutations of all four nucleotides occurring with different efficiencies, these cross-linking induced mutation sites (CIMS) also precisely map the location of the protein/RNA interactions71.

So far it is not well understood how the HITS-CLIP and PAR-CLIP experimental platforms compare. Certainly, there are a number of factors that contribute to differences in libraries, such as the cross-linking method, the nucleotide-specificity of the RNase used for clipping (RNase T1 vs. RNase A) and the extent of RNAse digest72, as well as the choice of linkers (ligation bias73). On the bioinformatics side, the algorithms and parameters chosen for alignment to the reference genome, algorithms and cut-off criteria used for cluster calling, and definition of seed matches influence which targets will be present in the final target lists. To date, only one study directly compared HITS-CLIP and PAR-CLIP data sets and determined a correlation of R2 > 0.4 to 0.65 between the two platforms72. In this study, all libraries were analyzed with the CLIPZ database74, a software pipeline specifically designed to analyze PAR-CLIP and HITS-CLIP data. Thus the observed differences between PAR-CLIP and HITS-CLIP datasets in this study are solely due to experimental differences/variation suggesting that cross-linking technique and RNase treatment differentially enrich for certain miRNA targets.

B. Viral MiRNA Regulatory Networks in EBV- and KSHV-Infected B Cells

Three laboratories including ours recently applied HITS-CLIP or PAR-CLIP to study the function of KSHV and EBV miRNAs: Riley et al. used HITS-CLIP to study EBV miRNA targets in Jijoye cells originally isolated from a patient tumor, exhibiting type III latency gene expression and expressing all 44 EBV miRNAs67. They found more than 1600 potential EBV miRNA targets. Skalsky et al. applied PAR-CLIP to a lymphoblastoid cell line (LCL) infected with an EBV laboratory strain, B95.8 lacking most of the BART miRNAs. This study reports a total of about 630 EBV miRNA targets70. The KSHV and EBV miRNA targetome was studied by Gottwein et al. in the KSHV/EBV co-infected primary effusion lymphoma (PEL) cell line BC-1 and the KSHV targetome in BC-3 (PAR-CLIP, more than 2000 putative targets)69. Finally, our laboratory identified more than 1600 putative targets of KSHV miRNAs in the KSHV-infected PEL cells BCBL-1 and BC-3 using HITS-CLIP68.

The three studies investigating EBV miRNAs report 7-25% of all sequenced miRNAs to originate from EBV. Similarly, KSHV miRNAs contribute about 20-30% of all miRNA reads in BCBL-1 and BC-1. In BC-3, however, KSHV miRNAs astonishingly comprised up to 70% of the sequencing reads. Deep sequencing data revealed miRNAs with alternatively processed 5′ ends, such as KSHV-miR-K10a_+1_5 (additional nt at the 5′ end) reported by Gottwein et al. Interestingly, this new version of miR-K10a shares the seed sequence with an alternatively processed miR-142-3p_-1_5 (lacking one nt at the 5′ end). It could be shown that miR-K10a_+1_5 indeed is a functional ortholog of miR-142-3p_-1_5 with a large set of common targets, several of which were experimentally validated69; in fact only 15% of the putative miR-K10a_+1_5 targets seem to be miR-K10a-specific. This is only the second functional ortholog of a human miRNA reported for KSHV in addition to miR-K11, which mimics the oncomir miR-15569, 70, 75, 76, a miRNA involved in lymphocyte activation 77-79. MiR-142-3p is a highly B cell-specific miRNA. Simultaneous targeting of transcripts by miR-142-3p and miR-K10a may serve to ensure the downregulation of certain miR-142-3p targets that are important for maintenance of KSHV latency. In non-B cells miR-K10a might mimic miR-142-3p function to create a more B cell-like environment69. Interestingly, EBV has developed a slightly distinct strategy: instead of expressing a human miRNA ortholog it induces miR-155 expression in type III latency cells to contribute to EBV-mediated signaling80-82.

C. HITS-CLIP and PAR-CLIP Revealed Only Few Viral Genes to be Regulated by Viral or Host MiRNAs

The majority of the mRNA sequencing reads align to the host genome, and only a very small number (< 2%) to the viral genomes, which is not unexpected since all studies investigate latently infected cells where viral gene expression is highly restricted. In KSHV, both studies recovered target sites for miR-K10a, -K10b, miR-142-3p and the let7/miR-98 family in the 3′UTRs of LANA, vCyclin, and v-FLIP, the ORFs of vCyclin and v-FLIP, and in the 3′UTRs of vIRF-3 and vIL-6. The latter was experimentally confirmed by luciferase reporter assay to be strongly down-regulated in the presence of miR-K10a68. vIL-6 is a mostly lytic gene involved in the inflammatory symptoms of KSHV-induced disorders such as MCD83, 84. However, vIL-6 has also pro-proliferative effects85 and was recently found to be expressed at very low levels during latency86. Possibly, targeting of vIL-6 by miR-K10a helps to keep vIL-6 levels low enough to profit from moderate growth support during latency while at the same time avoiding inflammatory responses.

In EBV, both studies consistently report targeting of EBNA2, LMP1 and BHRF167, 70. While EBNA2 displays an atypical pattern of wide clusters all over the transcript, there are very distinct clusters in the 3′UTRs of LMP1 and BHRF1 with seed matches for the human miR-17/20/106 seed family and viral miRNAs (BART3, BART19-5p, BART5-5p, BART10-3p), which were all functionally validated. Neither study, however, could confirm the previously reported miR-BART1-5p target sites in the LMP1 3′UTR40. Remarkably, instead of evolving to avoid targeting of the viral genome by human miRNAs, the miR-17/20/106 target sites in LMP1 and BHRF1 3′UTRs are even evolutionarily conserved between EBV and rhesus lymphocryptovirus (rLCV)70, which separated more than 13 million years ago87, indicating the importance of these target sites, although their role in viral biology is currently unknown67, 70. The miRNAs of the 17/20/106/93 seed family are part of three miRNA clusters, the oncogenic miR-17/92, the miR-106a-363 and miR-106b-25 cluster (reviewed by Olive et al.88). Both the mir-17/92 and 106/25 cluster are activated by the transcription factor c-myc89, 90, which in the EBV-positive BL cells is the major driver of proliferation91-93. MiR-17/92 activation via c-myc moreover leads to enhanced angiogenesis and inhibition of apoptosis. On the contrary, high expression of LMP1 can induce apoptosis94. Thus, targeting of LMP1 might serve to fine-tune a balance between proliferation and cell death during latency40, 67.

D. The Majority of Viral MiRNA Targets are Human Transcripts

HITS-CLIP as well as PAR-CLIP identified a large portion of previously validated viral miRNA targets. This together with the high percentage (>70%) of potential targets that could be functionally confirmed in each study68-70 reflects the confidence of the reported target sets produced by HITS-CLIP and PAR-CLIP. By using genetically engineered miRNA knockout viruses to compare potential miRNA interaction sites obtained in the presence or absence of a certain viral miRNA, Skalsky et al. moreover determined that the false–positive rate in PAR-CLIP-identified targets was just 11%70. The biggest target set for KSHV and EBV miRNAs was previously obtained by RIP-Chip, but it reported only 114 targets for KSHV and 44 for EBV46. Combined, the four CLIP studies demonstrate that, similar to human miRNAs, each viral miRNA targets between several dozen and a few hundred transcripts.

1.KSHV and EBV MiRNAs Target Similar Cellular Pathways

Interestingly, while EBV and KSHV miRNAs show no seed sequence homology, Gottwein et al. report a high overlap between EBV and KSHV targets in BC-1 cells (>55%)69. Consistently, there are many common themes in the pathways targeted by viral miRNAs in all four studies, such as apoptosis, cell cycle control, intracellular transport, protein transport and localization, transcription regulation, proteolysis, and immune evasion. So far only a few apoptotic genes were identified as KSHV44, 45, 64 or EBV miRNA targets41, 95, 96. Similarly, our knowledge of targeted immune modulatory genes such as the NK ligand MICB48, 49, IKBKE97, LIP (CEBP/B)98, IRAK1 and MYD8899 in KSHV, or CXCL1147 in EBV was very limited. The recent CLIP studies now suggest that dozens of apoptotic67-70 and immune modulatory68, 70 genes are targeted by KSHV and EBV miRNAs, thus not only confirming previous conclusions about viral miRNA functions but also underscoring the importance of these pathways. Interestingly, Skalsky et al. also found that many of the genes identified in LCLs with target sites for EBV miRNAs contain additional predicted target sites for KSHV or hCMV miRNAs70. The fact that miRNAs with no sequence homology have evolved to target identical pathways (e.g. immune evasion70) indicates that their downregulation is crucial for herpesvirus biology.

Moreover, the suggested miRNA targetomes of the four studies are strongly enriched for novel interesting cellular pathways, such as the glycolysis pathway in KSHV68, the WNT pathway in EBV67, 69, the MAPKKK cascade69, and the PI3 kinase and Ras pathways70. Follow-up studies will show how miRNA regulation of these targets contributes to viral biology and/or pathogenesis. We don't go deeper into details of specific new targets in this review, but instead point the interested reader to the extensive supplemental material about the identified targetomes provided by all four studies67-70.

2.Viral MiRNAs Co-target Transcripts with Human MiRNAs

For KSHV as well as for EBV a significant overlap between human and viral miRNA targets was reported. While in KSHV 55-65% of viral miRNA targets had additional interaction sites for human miRNAs68, in EBV 75-90% were co-targeted by human miRNAs67, 70. Interestingly, in Jijoye cells, 50% of the co-targeted transcripts are targets of the very abundant members of the miR-17/92 cluster67. One factor that contributes to the high number of overlapping targets are seed homologies between human and viral miRNAs, such as miR-155/miR-K11, and miR-142-3p_-1_5/miR-K10a_+1_5 in KSHV or the miR-29/miR-BART1-3p and miR-18/miR-BART5-5p in EBV, which share full seed homology (nt 1-7, 2-7 or 2-8). Others share a partial overlap (6-mer) that is offset by one nucleotide (e.g. miR-181/miR-K3, miR-15/miR-K6-5p, miR-27/miR-K11*, or miR-196/miR-K5* in KSHV (Haecker et al. unpublished observations). The concept that viral and human miRNAs with identical seeds indeed share common targets has been experimentally validated in several cases for miR-155/miR-K11 and miR-142-3p/miR-K10a68, 69, 100-103). The study by Riley et al. elegantly extends these observations, by analyzing how the nucleotides around the seed sequence can influence targeting by these orthologs. It shows that miR-BART5-5p targets LMP1 but miR-18a does not despite an identical seed sequence (nt 2-7). In this case the nucleotides directly adjacent to both sides of the seed seem to be the decisive factor. They cause the target alignment to be shifted by one nucleotide between the two miRNAs and LMP1 (nt 1-7 for miR-18a, and 2-8 for Bart-5-5p), resulting in a weaker predicted duplex for miR-18a67. Interestingly, seed homologies exist also among EBV miRNAs, e.g. miR-BHRF-1 and miR-BART4 or miR-BART1-3p and 3-3p share a seed that is off-set by one nucleotide and the latter two indeed target the same 3′UTR in a luciferase reporter assay70. Skalsky and coworkers suggest that this could help to ensure that important pathways are targeted at all times since EBV miRNA expression depends on latency stage and cell type (lymphoid versus epithelial).

The strong target overlap between human and viral miRNA targets, however, is only partially due to seed homologies. The majority of identified transcripts have distinct target sites for the co-targeting miRNAs in their 3′UTR. The functionality of multiple target sites (viral/viral or viral/human) within one 3′UTR was not only confirmed for several transcripts67-70, but it was also shown that these interactions can be cumulative43, 67, 68. The concept of co-targeting of a 3′UTR by multiple miRNAs certainly is not new, but these four CLIP studies for the first time indicates that it occurs at a large extent between viral and human miRNAs in infected cells. Co-targeting could reflect a hijacking of existing human pathways by viral miRNAs, especially in cases where viral miRNAs mimic their human counterparts70. Since in somatic cells miRNA-mediated post-transcriptional regulation fine tunes transcript levels, the effects of viral miRNAs (often expressed at high copy numbers) targeting the same genes could have significant consequences for the host cell by tipping gene expression in the direction that is advantageous for the virus. We call it active interference here. In an inverse scenario (passive interference), the high levels of viral miRNAs in infected cells (comprising up to 70% of the total RNA count) could have a different effect: instead of ensuring targeting of certain pathways by viral miRNAs, their large numbers could tip the competition for the existing limited pool of RISC complexes104, thereby excluding many human miRNAs from access to RISC67, 68. Conceptually intriguing, this sequence-independent passive mode of viral miRNA-dependent regulation could result in a global up-regulation of host cellular genes.

In summary, the recent CLIP studies not only provide a much broader picture of the viral miRNA targetomes but also point to novel cellular pathways that may play important roles in viral biology. Moreover, these comprehensive target databases are a valuable resource for the miRNA research community that allows to search for specific miRNA-target interactions and targeted pathways of interest (not only of viral but also human miRNAs) for the subsequent design of functional follow-up studies.

D. Opportunities and Challenges of HITS-CLIP and PAR-CLIP Studies

As with all methods that create large datasets, the complex data analysis is the bottleneck for all researchers taking on HITS-CLIP or PAR-CLIP studies. The drylab (bioinformatics) often cannot keep up with the wet lab, and many laboratories don't have the infrastructure and/or expertise nearby that would allow them to create their own analysis pipeline. To our knowledge, currently only two analysis tools are publically accessible, CLIPZ74, which can be used for HITS-CLIP and PAR-CLIP datasets, and PARalyzer105, developed specifically for PAR-CLIP. The limited availability of free analysis tools and resulting use of individual solutions by many different research groups makes the comparison of published target lists difficult. A true comparison would require the reanalysis of the original datasets with the same pipeline using identical parameters.

Nevertheless, Ago CLIP has opened an important door in miRNA targetome analysis. CLIP is the first method that truly allows the simultaneous analysis of hundreds of direct miRNA-mRNA interactions instead of single miRNA-target pairs, and thus is the best tool to provide information about the large and complex miRNA regulation networks. Moreover, instead of overexpression studies that are often conducted in unrelated cell lines, the targets of a miRNA can now be studied at physiological levels and in its physiological, cell type-specific environment. HITS-CLIP (but not PAR-CLIP) in addition can be applied to primary tissues to analyze organ or tumor-specific targetomes and the consequences of miRNA deregulation in various diseases including cancers. Finally, miRNA knockout viruses in combination with CLIP can be used to dissect the functions of single miRNAs within the complex network of other viral and human miRNAs, which will likely help to better understand the mechanisms of miRNA-mediated gene regulation.

Acknowledgments

We want to apologize to all authors whose work on viral miRNAs was not cited in this review due to space restraints. This work was in part supported by NIH/NCI grants RO1CA119917, and RC2CA148407.

References

- 1.Lee RC, Feinbaum RL, Ambros V. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell. 1993 Dec 3;75(5):843–54. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90529-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reinhart BJ, Slack FJ, Basson M, Pasquinelli AE, Bettinger JC, Rougvie AE, Horvitz HR, Ruvkun G. The 21-nucleotide let-7 RNA regulates developmental timing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2000 Feb 24;403(6772):901–6. doi: 10.1038/35002607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pasquinelli AE, Reinhart BJ, Slack F, Martindale MQ, Kuroda MI, Maller B, Hayward DC, Ball EE, Degnan B, Muller P, Spring J, Srinivasan A, Fishman M, Finnerty J, Corbo J, Levine M, Leahy P, Davidson E, Ruvkun G. Conservation of the sequence and temporal expression of let-7 heterochronic regulatory RNA. Nature. 2000 Nov 2;408(6808):86–9. doi: 10.1038/35040556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kozomara A, Griffiths-Jones S. miRBase: integrating microRNA annotation and deep-sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011 Jan;39(Database issue):D152–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Griffiths-Jones S. The microRNA Registry. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004 Jan 1;32(Database issue):D109–11. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bogerd HP, Karnowski HW, Cai X, Shin J, Pohlers M, Cullen BR. A mammalian herpesvirus uses noncanonical expression and processing mechanisms to generate viral MicroRNAs. Mol Cell. 2010 Jan 15;37(1):135–42. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kincaid RP, Burke JM, Sullivan CS. RNA virus microRNA that mimics a B-cell oncomiR. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012 Feb 21;109(8):3077–82. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1116107109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewis BP, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell. 2005 Jan 14;120(1):15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lewis BP, Shih IH, Jones-Rhoades MW, Bartel DP, Burge CB. Prediction of mammalian microRNA targets. Cell. 2003 Dec 26;115(7):787–98. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009 Jan 23;136(2):215–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shin C, Nam JW, Farh KK, Chiang HR, Shkumatava A, Bartel DP. Expanding the microRNA targeting code: functional sites with centered pairing. Mol Cell. 2010 Jun 25;38(6):789–802. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chi SW, Hannon GJ, Darnell RB. An alternative mode of microRNA target recognition. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2012 Mar;19(3):321–7. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Filipowicz W, Bhattacharyya SN, Sonenberg N. Mechanisms of post-transcriptional regulation by microRNAs: are the answers in sight? Nat Rev Genet. 2008 Feb;9(2):102–14. doi: 10.1038/nrg2290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang J, Yuan YA. A structural perspective of the protein-RNA interactions involved in virus-induced RNA silencing and its suppression. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009 Sep-Oct;1789(9-10):642–52. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones-Rhoades MW, Bartel DP, Bartel B. MicroRNAS and their regulatory roles in plants. Annual review of plant biology. 2006;57:19–53. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fabian MR, Sonenberg N. The mechanics of miRNA-mediated gene silencing: a look under the hood of miRISC. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2012 Jun;19(6):586–93. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eulalio A, Huntzinger E, Nishihara T, Rehwinkel J, Fauser M, Izaurralde E. Deadenylation is a widespread effect of miRNA regulation. RNA. 2009 Jan;15(1):21–32. doi: 10.1261/rna.1399509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giraldez AJ, Mishima Y, Rihel J, Grocock RJ, Van Dongen S, Inoue K, Enright AJ, Schier AF. Zebrafish MiR-430 promotes deadenylation and clearance of maternal mRNAs. Science. 2006 Apr 7;312(5770):75–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1122689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Behm-Ansmant I, Rehwinkel J, Doerks T, Stark A, Bork P, Izaurralde E. mRNA degradation by miRNAs and GW182 requires both CCR4:NOT deadenylase and DCP1:DCP2 decapping complexes. Genes Dev. 2006 Jul 15;20(14):1885–98. doi: 10.1101/gad.1424106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fabian MR, Sonenberg N, Filipowicz W. Regulation of mRNA translation and stability by microRNAs. Annu Rev Biochem. 2010;79:351–79. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060308-103103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baek D, Villen J, Shin C, Camargo FD, Gygi SP, Bartel DP. The impact of microRNAs on protein output. Nature. 2008 Sep 4;455(7209):64–71. doi: 10.1038/nature07242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Selbach M, Schwanhausser B, Thierfelder N, Fang Z, Khanin R, Rajewsky N. Widespread changes in protein synthesis induced by microRNAs. Nature. 2008 Sep 4;455(7209):58–63. doi: 10.1038/nature07228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guo H, Ingolia NT, Weissman JS, Bartel DP. Mammalian microRNAs predominantly act to decrease target mRNA levels. Nature. 2010 Aug 12;466(7308):835–40. doi: 10.1038/nature09267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takagi S, Nakajima M, Kida K, Yamaura Y, Fukami T, Yokoi T. MicroRNAs regulate human hepatocyte nuclear factor 4alpha, modulating the expression of metabolic enzymes and cell cycle. J Biol Chem. 2010 Feb 12;285(7):4415–22. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.085431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Forman JJ, Legesse-Miller A, Coller HA. A search for conserved sequences in coding regions reveals that the let-7 microRNA targets Dicer within its coding sequence. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008 Sep 30;105(39):14879–84. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803230105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang WX, Wilfred BR, Xie K, Jennings MH, Hu YH, Stromberg AJ, Nelson PT. Individual microRNAs (miRNAs) display distinct mRNA targeting “rules”. RNA biology. 2011 May-Jun;7(3):373–80. doi: 10.4161/rna.7.3.11693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schnall-Levin M, Rissland OS, Johnston WK, Perrimon N, Bartel DP, Berger B. Unusually effective microRNA targeting within repeat-rich coding regions of mammalian mRNAs. Genome research. 2011 Sep;21(9):1395–403. doi: 10.1101/gr.121210.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grimson A, Farh KK, Johnston WK, Garrett-Engele P, Lim LP, Bartel DP. MicroRNA targeting specificity in mammals: determinants beyond seed pairing. Mol Cell. 2007 Jul 6;27(1):91–105. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fang Z, Rajewsky N. The impact of miRNA target sites in coding sequences and in 3′UTRs. PloS one. 2011;6(3):e18067. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mukherji S, Ebert MS, Zheng GX, Tsang JS, Sharp PA, van Oudenaarden A. MicroRNAs can generate thresholds in target gene expression. Nat Genet. 2011 Sep;43(9):854–9. doi: 10.1038/ng.905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pfeffer S, Zavolan M, Grasser FA, Chien M, Russo JJ, Ju J, John B, Enright AJ, Marks D, Sander C, Tuschl T. Identification of virus-encoded microRNAs. Science. 2004 Apr 30;304(5671):734–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1096781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boss IW, Plaisance KB, Renne R. Role of virus-encoded microRNAs in herpesvirus biology. Trends Microbiol. 2009 Dec;17(12):544–53. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Skalsky RL, Cullen BR. Viruses, microRNAs, and host interactions. Annual review of microbiology. 2010 Oct 13;64:123–41. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Areste C, Blackbourn DJ. Modulation of the immune system by Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. Trends Microbiol. 2009 Mar;17(3):119–29. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wen KW, Damania B. Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV): molecular biology and oncogenesis. Cancer Lett. 2010 Mar 28;289(2):140–50. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Umbach JL, Kramer MF, Jurak I, Karnowski HW, Coen DM, Cullen BR. MicroRNAs expressed by herpes simplex virus 1 during latent infection regulate viral mRNAs. Nature. 2008 Aug 7;454(7205):780–3. doi: 10.1038/nature07103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tang S, Patel A, Krause PR. Novel less-abundant viral microRNAs encoded by herpes simplex virus 2 latency-associated transcript and their roles in regulating ICP34.5 and ICP0 mRNAs. Journal of virology. 2009 Feb;83(3):1433–42. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01723-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bellare P, Ganem D. Regulation of KSHV lytic switch protein expression by a virus-encoded microRNA: an evolutionary adaptation that fine-tunes lytic reactivation. Cell host & microbe. 2009 Dec 17;6(6):570–5. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lu F, Stedman W, Yousef M, Renne R, Lieberman PM. Epigenetic regulation of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latency by virus-encoded microRNAs that target Rta and the cellular Rbl2-DNMT pathway. Journal of virology. 2010 Mar;84(6):2697–706. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01997-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lo AK, To KF, Lo KW, Lung RW, Hui JW, Liao G, Hayward SD. Modulation of LMP1 protein expression by EBV-encoded microRNAs. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007 Oct 9;104(41):16164–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702896104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Choy EY, Siu KL, Kok KH, Lung RW, Tsang CM, To KF, Kwong DL, Tsao SW, Jin DY. An Epstein-Barr virus-encoded microRNA targets PUMA to promote host cell survival. J Exp Med. 2008 Oct 27;205(11):2551–60. doi: 10.1084/jem.20072581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu S, Xue C, Li J, Bi Y, Cao Y. Marek's disease virus type 1 microRNA miR-M3 suppresses cisplatin-induced apoptosis by targeting Smad2 of the transforming growth factor beta signal pathway. Journal of virology. 2010 Jan;85(1):276–85. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01392-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Samols MA, Hu J, Skalsky RL, Maldonado AM, Riva A, Lopez MC, Baker HV, Renne R. Identification of cellular genes targeted by KSHV-encoded microRNAs. PLoS Pathog. 2007 May 11; doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030065. 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Abend JR, Uldrick T, Ziegelbauer JM. Regulation of tumor necrosis factor-like weak inducer of apoptosis receptor protein (TWEAKR) expression by Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus microRNA prevents TWEAK-induced apoptosis and inflammatory cytokine expression. Journal of virology. 2010 Dec;84(23):12139–51. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00884-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Suffert G, Malterer G, Hausser J, Viiliainen J, Fender A, Contrant M, Ivacevic T, Benes V, Gros F, Voinnet O, Zavolan M, Ojala PM, Haas JG, Pfeffer S. Kaposi's sarcoma herpesvirus microRNAs target caspase 3 and regulate apoptosis. PLoS Pathog. 2011 Dec;7(12):e1002405. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dolken L, Malterer G, Erhard F, Kothe S, Friedel CC, Suffert G, Marcinowski L, Motsch N, Barth S, Beitzinger M, Lieber D, Bailer SM, Hoffmann R, Ruzsics Z, Kremmer E, Pfeffer S, Zimmer R, Koszinowski UH, Grasser F, Meister G, Haas J. Systematic analysis of viral and cellular microRNA targets in cells latently infected with human gamma-herpesviruses by RISC immunoprecipitation assay. Cell host & microbe. 2010 Apr 22;7(4):324–34. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xia T, O'Hara A, Araujo I, Barreto J, Carvalho E, Sapucaia JB, Ramos JC, Luz E, Pedroso C, Manrique M, Toomey NL, Brites C, Dittmer DP, Harrington WJ., Jr EBV microRNAs in primary lymphomas and targeting of CXCL-11 by ebv-mir-BHRF1-3. Cancer Res. 2008 Mar 1;68(5):1436–42. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stern-Ginossar N, Elefant N, Zimmermann A, Wolf DG, Saleh N, Biton M, Horwitz E, Prokocimer Z, Prichard M, Hahn G, Goldman-Wohl D, Greenfield C, Yagel S, Hengel H, Altuvia Y, Margalit H, Mandelboim O. Host immune system gene targeting by a viral miRNA. Science. 2007 Jul 20;317(5836):376–81. doi: 10.1126/science.1140956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nachmani D, Stern-Ginossar N, Sarid R, Mandelboim O. Diverse herpesvirus microRNAs target the stress-induced immune ligand MICB to escape recognition by natural killer cells. Cell host & microbe. 2009 Apr 23;5(4):376–85. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Enright AJ, John B, Gaul U, Tuschl T, Sander C, Marks DS. MicroRNA targets in Drosophila. Genome Biol. 2003;5(1):R1. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-5-1-r1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kertesz M, Iovino N, Unnerstall U, Gaul U, Segal E. The role of site accessibility in microRNA target recognition. Nat Genet. 2007 Oct;39(10):1278–84. doi: 10.1038/ng2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kiriakidou M, Nelson PT, Kouranov A, Fitziev P, Bouyioukos C, Mourelatos Z, Hatzigeorgiou A. A combined computational-experimental approach predicts human microRNA targets. Genes Dev. 2004 May 15;18(10):1165–78. doi: 10.1101/gad.1184704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Krek A, Grun D, Poy MN, Wolf R, Rosenberg L, Epstein EJ, MacMenamin P, da Piedade I, Gunsalus KC, Stoffel M, Rajewsky N. Combinatorial microRNA target predictions. Nat Genet. 2005 May;37(5):495–500. doi: 10.1038/ng1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Miranda KC, Huynh T, Tay Y, Ang YS, Tam WL, Thomson AM, Lim B, Rigoutsos I. A pattern-based method for the identification of MicroRNA binding sites and their corresponding heteroduplexes. Cell. 2006 Sep 22;126(6):1203–17. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kruger J, Rehmsmeier M. RNAhybrid: microRNA target prediction easy, fast and flexible. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006 Jul 1;34(Web Server issue):W451–4. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rehmsmeier M, Steffen P, Hochsmann M, Giegerich R. Fast and effective prediction of microRNA/target duplexes. RNA. 2004 Oct;10(10):1507–17. doi: 10.1261/rna.5248604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Maragkakis M, Alexiou P, Papadopoulos GL, Reczko M, Dalamagas T, Giannopoulos G, Goumas G, Koukis E, Kourtis K, Simossis VA, Sethupathy P, Vergoulis T, Koziris N, Sellis T, Tsanakas P, Hatzigeorgiou AG. Accurate microRNA target prediction correlates with protein repression levels. BMC bioinformatics. 2009;10:295. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bentwich I. Prediction and validation of microRNAs and their targets. FEBS Lett. 2005 Oct 31;579(26):5904–10. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sethupathy P, Megraw M, Hatzigeorgiou AG. A guide through present computational approaches for the identification of mammalian microRNA targets. Nat Methods. 2006 Nov;3(11):881–6. doi: 10.1038/nmeth954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Easow G, Teleman AA, Cohen SM. Isolation of microRNA targets by miRNP immunopurification. RNA. 2007 Aug;13(8):1198–204. doi: 10.1261/rna.563707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lim LP, Lau NC, Garrett-Engele P, Grimson A, Schelter JM, Castle J, Bartel DP, Linsley PS, Johnson JM. Microarray analysis shows that some microRNAs downregulate large numbers of target mRNAs. Nature. 2005 Feb 17;433(7027):769–73. doi: 10.1038/nature03315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pillai RS, Bhattacharyya SN, Artus CG, Zoller T, Cougot N, Basyuk E, Bertrand E, Filipowicz W. Inhibition of translational initiation by Let-7 MicroRNA in human cells. Science. 2005 Sep 2;309(5740):1573–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1115079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Krutzfeldt J, Rajewsky N, Braich R, Rajeev KG, Tuschl T, Manoharan M, Stoffel M. Silencing of microRNAs in vivo with ‘antagomirs'. Nature. 2005 Dec 1;438(7068):685–9. doi: 10.1038/nature04303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ziegelbauer JM, Sullivan CS, Ganem D. Tandem array-based expression screens identify host mRNA targets of virus-encoded microRNAs. Nat Genet. 2009 Jan;41(1):130–4. doi: 10.1038/ng.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chi SW, Zang JB, Mele A, Darnell RB. Argonaute HITS-CLIP decodes microRNA-mRNA interaction maps. Nature. 2009 Jul 23;460(7254):479–86. doi: 10.1038/nature08170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hafner M, Landthaler M, Burger L, Khorshid M, Hausser J, Berninger P, Rothballer A, Ascano M, Jr, Jungkamp AC, Munschauer M, Ulrich A, Wardle GS, Dewell S, Zavolan M, Tuschl T. Transcriptome-wide identification of RNA-binding protein and microRNA target sites by PAR-CLIP. Cell. 2010 Apr 2;141(1):129–41. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Riley KJ, Rabinowitz GS, Yario TA, Luna JM, Darnell RB, Steitz JA. EBV and human microRNAs co-target oncogenic and apoptotic viral and human genes during latency. Embo J. 2012 May 2;31(9):2207–21. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Haecker I, Gay LA, Yang Y, Hu J, Morse AM, McIntyre L, Renne R. Ago-HITS-CLIP Expands Understanding of Kaposi's Sarcoma-associated Herpesvirus miRNA Function in Primary Effusion Lymphomas. PLoS Pathog. 2012 Aug;8(8):e1002884. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gottwein E, Corcoran DL, Mukherjee N, Skalsky RL, Hafner M, Nusbaum JD, Shamulailatpam P, Love CL, Dave SS, Tuschl T, Ohler U, Cullen BR. Viral microRNA targetome of KSHV-infected primary effusion lymphoma cell lines. Cell host & microbe. 2011 Nov 17;10(5):515–26. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Skalsky RL, Corcoran DL, Gottwein E, Frank CL, Kang D, Hafner M, Nusbaum JD, Feederle R, Delecluse HJ, Luftig MA, Tuschl T, Ohler U, Cullen BR. The Viral and Cellular MicroRNA Targetome in Lymphoblastoid Cell Lines. PLoS Pathog. 2012 Jan;8(1):e1002484. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhang C, Darnell RB. Mapping in vivo protein-RNA interactions at single-nucleotide resolution from HITS-CLIP data. Nature biotechnology. 2011 Jul;29(7):607–14. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kishore S, Jaskiewicz L, Burger L, Hausser J, Khorshid M, Zavolan M. A quantitative analysis of CLIP methods for identifying binding sites of RNA-binding proteins. Nat Methods. 2011 May 15; doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jayaprakash AD, Jabado O, Brown BD, Sachidanandam R. Identification and remediation of biases in the activity of RNA ligases in small-RNA deep sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011 Nov;39(21):e141. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Khorshid M, Rodak C, Zavolan M. CLIPZ: a database and analysis environment for experimentally determined binding sites of RNA-binding proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011 Jan;39(Database issue):D245–52. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Costinean S, Zanesi N, Pekarsky Y, Tili E, Volinia S, Heerema N, Croce CM. Pre-B cell proliferation and lymphoblastic leukemia/high-grade lymphoma in E(mu)-miR155 transgenic mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006 May 2;103(18):7024–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602266103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.He L, Thomson JM, Hemann MT, Hernando-Monge E, Mu D, Goodson S, Powers S, Cordon-Cardo C, Lowe SW, Hannon GJ, Hammond SM. A microRNA polycistron as a potential human oncogene. Nature. 2005 Jun 9;435(7043):828–33. doi: 10.1038/nature03552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.O'Connell RM, Taganov KD, Boldin MP, Cheng G, Baltimore D. MicroRNA-155 is induced during the macrophage inflammatory response. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007 Jan 30;104(5):1604–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610731104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rodriguez A, Vigorito E, Clare S, Warren MV, Couttet P, Soond DR, van Dongen S, Grocock RJ, Das PP, Miska EA, Vetrie D, Okkenhaug K, Enright AJ, Dougan G, Turner M, Bradley A. Requirement of bic/microRNA-155 for normal immune function. Science. 2007 Apr 27;316(5824):608–11. doi: 10.1126/science.1139253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Vigorito E, Perks KL, Abreu-Goodger C, Bunting S, Xiang Z, Kohlhaas S, Das PP, Miska EA, Rodriguez A, Bradley A, Smith KG, Rada C, Enright AJ, Toellner KM, Maclennan IC, Turner M. microRNA-155 regulates the generation of immunoglobulin class-switched plasma cells. Immunity. 2007 Dec;27(6):847–59. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yin Q, McBride J, Fewell C, Lacey M, Wang X, Lin Z, Cameron J, Flemington EK. MicroRNA-155 is an Epstein-Barr virus-induced gene that modulates Epstein-Barr virus-regulated gene expression pathways. Journal of virology. 2008 Jun;82(11):5295–306. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02380-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Xu G, Fewell C, Taylor C, Deng N, Hedges D, Wang X, Zhang K, Lacey M, Zhang H, Yin Q, Cameron J, Lin Z, Zhu D, Flemington EK. Transcriptome and targetome analysis in MIR155 expressing cells using RNA-seq. RNA. 2010 Aug;16(8):1610–22. doi: 10.1261/rna.2194910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Linnstaedt SD, Gottwein E, Skalsky RL, Luftig MA, Cullen BR. Virally induced cellular microRNA miR-155 plays a key role in B-cell immortalization by Epstein-Barr virus. Journal of virology. 2010 Nov;84(22):11670–8. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01248-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mori Y, Nishimoto N, Ohno M, Inagi R, Dhepakson P, Amou K, Yoshizaki K, Yamanishi K. Human herpesvirus 8-encoded interleukin-6 homologue (viral IL-6) induces endogenous human IL-6 secretion. Journal of medical virology. 2000 Jul;61(3):332–5. doi: 10.1002/1096-9071(200007)61:3<332::aid-jmv8>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Uldrick TS, Wang V, O'Mahony D, Aleman K, Wyvill KM, Marshall V, Steinberg SM, Pittaluga S, Maric I, Whitby D, Tosato G, Little RF, Yarchoan R. An interleukin-6-related systemic inflammatory syndrome in patients co-infected with Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus and HIV but without Multicentric Castleman disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2010 Aug 1;51(3):350–8. doi: 10.1086/654798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Jones KD, Aoki Y, Chang Y, Moore PS, Yarchoan R, Tosato G. Involvement of interleukin-10 (IL-10) and viral IL-6 in the spontaneous growth of Kaposi's sarcoma herpesvirus-associated infected primary effusion lymphoma cells. Blood. 1999 Oct 15;94(8):2871–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chandriani S, Ganem D. Array-based transcript profiling and limiting-dilution reverse transcription-PCR analysis identify additional latent genes in Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. Journal of virology. 2010 Jun;84(11):5565–73. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02723-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cai X, Schafer A, Lu S, Bilello JP, Desrosiers RC, Edwards R, Raab-Traub N, Cullen BR. Epstein-Barr virus microRNAs are evolutionarily conserved and differentially expressed. PLoS Pathog. 2006 Mar;2(3):e23. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Olive V, Jiang I, He L. mir-17-92, a cluster of miRNAs in the midst of the cancer network. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology. 2010 Aug;42(8):1348–54. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.O'Donnell KA, Wentzel EA, Zeller KI, Dang CV, Mendell JT. c-Myc-regulated microRNAs modulate E2F1 expression. Nature. 2005 Jun 9;435(7043):839–43. doi: 10.1038/nature03677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Petrocca F, Vecchione A, Croce CM. Emerging role of miR-106b-25/miR-17-92 clusters in the control of transforming growth factor beta signaling. Cancer Res. 2008 Oct 15;68(20):8191–4. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Faumont N, Durand-Panteix S, Schlee M, Gromminger S, Schuhmacher M, Holzel M, Laux G, Mailhammer R, Rosenwald A, Staudt LM, Bornkamm GW, Feuillard J. c-Myc and Rel/NF-kappaB are the two master transcriptional systems activated in the latency III program of Epstein-Barr virus-immortalized B cells. Journal of virology. 2009 May;83(10):5014–27. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02264-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Thorley-Lawson DA, Allday MJ. The curious case of the tumour virus: 50 years of Burkitt's lymphoma. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008 Dec;6(12):913–24. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Allday MJ. How does Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) complement the activation of Myc in the pathogenesis of Burkitt's lymphoma? Semin Cancer Biol. 2009 Dec;19(6):366–76. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2009.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lu JJ, Chen JY, Hsu TY, Yu WC, Su IJ, Yang CS. Induction of apoptosis in epithelial cells by Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1. J Gen Virol. 1996 Aug;77(Pt 8):1883–92. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-8-1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Seto E, Moosmann A, Gromminger S, Walz N, Grundhoff A, Hammerschmidt W. Micro RNAs of Epstein-Barr virus promote cell cycle progression and prevent apoptosis of primary human B cells. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6(8):e1001063. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Marquitz AR, Mathur A, Nam CS, Raab-Traub N. The Epstein-Barr Virus BART microRNAs target the pro-apoptotic protein Bim. Virology. 2011 Apr 10;412(2):392–400. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2011.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Liang D, Gao Y, Lin X, He Z, Zhao Q, Deng Q, Lan K. A human herpesvirus miRNA attenuates interferon signaling and contributes to maintenance of viral latency by targeting IKKvarepsilon. Cell research. 2011 May;21(5):793–806. doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Qin Z, Kearney P, Plaisance K, Parsons CH. Pivotal advance: Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV)-encoded microRNA specifically induce IL-6 and IL-10 secretion by macrophages and monocytes. Journal of leukocyte biology. 2010 Jan;87(1):25–34. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0409251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Abend JR, Ramalingam D, Kieffer-Kwon P, Uldrick TS, Yarchoan R, Ziegelbauer JM. KSHV microRNAs target two components of the TLR/IL-1R signaling cascade, IRAK1 and MYD88, to reduce inflammatory cytokine expression. Journal of virology. 2012 Aug 15; doi: 10.1128/JVI.01147-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Liu Y, Sun R, Lin X, Liang D, Deng Q, Lan K. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-encoded microRNA miR-K12-11 attenuates transforming growth factor beta signaling through suppression of SMAD5. Journal of virology. 2012 Feb;86(3):1372–81. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06245-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Gottwein E, Mukherjee N, Sachse C, Frenzel C, Majoros WH, Chi JT, Braich R, Manoharan M, Soutschek J, Ohler U, Cullen BR. A viral microRNA functions as an orthologue of cellular miR-155. Nature. 2007 Dec 13;450(7172):1096–9. doi: 10.1038/nature05992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Skalsky RL, Samols MA, Plaisance KB, Boss IW, Riva A, Lopez MC, Baker HV, Renne R. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus encodes an ortholog of miR-155. Journal of virology. 2007 Dec;81(23):12836–45. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01804-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Boss IW, Nadeau PE, Abbott JR, Yang Y, Mergia A, Renne R. A Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-encoded ortholog of microRNA miR-155 induces human splenic B-cell expansion in NOD/LtSz-scid IL2Rgammanull mice. Journal of virology. 2011 Oct;85(19):9877–86. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05558-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Khan AA, Betel D, Miller ML, Sander C, Leslie CS, Marks DS. Transfection of small RNAs globally perturbs gene regulation by endogenous microRNAs. Nature biotechnology. 2009 Jun;27(6):549–55. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Corcoran DL, Georgiev S, Mukherjee N, Gottwein E, Skalsky RL, Keene JD, Ohler U. PARalyzer: definition of RNA binding sites from PAR-CLIP short-read sequence data. Genome Biol. 2011;12(8):R79. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-8-r79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Qin Z, Freitas E, Sullivan R, Mohan S, Bacelieri R, Branch D, Romano M, Kearney P, Oates J, Plaisance K, Renne R, Kaleeba J, Parsons C. Upregulation of xCT by KSHV-encoded microRNAs facilitates KSHV dissemination and persistence in an environment of oxidative stress. PLoS Pathog. 2010 Jan;6(1):e1000742. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Hansen A, Henderson S, Lagos D, Nikitenko L, Coulter E, Roberts S, Gratrix F, Plaisance K, Renne R, Bower M, Kellam P, Boshoff C. KSHV-encoded miRNAs target MAF to induce endothelial cell reprogramming. Genes Dev. 2010 Jan 15;24(2):195–205. doi: 10.1101/gad.553410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Lu CC, Li Z, Chu CY, Feng J, Feng J, Sun R, Rana TM. MicroRNAs encoded by Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus regulate viral life cycle. EMBO Rep. 2010 Oct;11(10):784–90. doi: 10.1038/embor.2010.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Lei X, Bai Z, Ye F, Xie J, Kim CG, Huang Y, Gao SJ. Regulation of NF-kappaB inhibitor IkappaBalpha and viral replication by a KSHV microRNA. Nat Cell Biol. 2010 Feb;12(2):193–9. doi: 10.1038/ncb2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Lei X, Zhu Y, Jones T, Bai Z, Huang Y, Gao SJ. A KSHV microRNA and its variants target TGF-beta pathway to promote cell survival. Journal of virology. 2012 Aug 22; doi: 10.1128/JVI.06855-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Iizasa H, Wulff BE, Alla NR, Maragkakis M, Megraw M, Hatzigeorgiou A, Iwakiri D, Takada K, Wiedmer A, Showe L, Lieberman P, Nishikura K. Editing of Epstein-Barr virus-encoded BART6 microRNAs controls their dicer targeting and consequently affects viral latency. J Biol Chem. 2010 Oct 22;285(43):33358–70. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.138362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Grey F, Tirabassi R, Meyers H, Wu G, McWeeney S, Hook L, Nelson JA. A viral microRNA down-regulates multiple cell cycle genes through mRNA 5′UTRs. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6(6):e1000967. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Muylkens B, Coupeau D, Dambrine G, Trapp S, Rasschaert D. Marek's disease virus microRNA designated Mdv1-pre-miR-M4 targets both cellular and viral genes. Archives of virology. 2010 Nov;155(11):1823–37. doi: 10.1007/s00705-010-0777-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Zhao Y, Yao Y, Xu H, Lambeth L, Smith LP, Kgosana L, Wang X, Nair V. A functional MicroRNA-155 ortholog encoded by the oncogenic Marek's disease virus. Journal of virology. 2009 Jan;83(1):489–92. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01166-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]