Abstract

Emerging data have shown a close association between compositional changes in gut microbiota and the development of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). The change in gut microbiota may alter nutritional absorption and storage. In addition, gut microbiota are a source of Toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands, and their compositional change can also increase the amount of TLR ligands delivered to the liver. TLR ligands can stimulate liver cells to produce proinflammatory cytokines. Therefore, the gut-liver axis has attracted much interest, particularly regarding the pathogenesis of NAFLD. The abundance of the major gut microbiota, including Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes, has been considered a potential underlying mechanism of obesity and NAFLD, but the role of these microbiota in NAFLD remains unknown. Several reports have demonstrated that certain gut microbiota are associated with the development of obesity and NAFLD. For instance, a decrease in Akkermansia muciniphila causes a thinner intestinal mucus layer and promotes gut permeability, which allows the leakage of bacterial components. Interventions to increase Akkermansia muciniphila improve the metabolic parameters in obesity and NAFLD. In children, the levels of Escherichia were significantly increased in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) compared with those in obese control. Escherichia can produce ethanol, which promotes gut permeability. Thus, normalization of gut microbiota using probiotics or prebiotics is a promising treatment option for NAFLD. In addition, TLR signaling in the liver is activated, and its downstream molecules, such as proinflammatory cytokines, are increased in NAFLD. To data, TLR2, TLR4, TLR5, and TLR9 have been shown to be associated with the pathogenesis of NAFLD. Therefore, gut microbiota and TLRs are targets for NAFLD treatment.

Keywords: Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, Gut microbiota, Toll-like receptor, Probiotics, Prebiotics

Core tip: The gut-liver axis has attracted much interest particularly regarding the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) because gut microbiota contribute to nutritional absorption and storage. In addition, gut microbiota are a source of Toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands, which can stimulate liver cells to produce proinflammatory cytokines. To date, TLR2, TLR4, TLR5, and TLR9 have been shown to be associated with the pathogenesis of NAFLD. The present article reviewed the current understanding of gut microbiota and TLR signaling in NAFLD and potential treatment targeted at gut microbiota and TLRs.

INTRODUCTION

The gut-liver axis has attracted much interest regarding the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), in which the balance between nutritional absorption and energy storage and expenditure is impaired. The gut is an organ that absorbs a variety of nutritional components from food; gut microbiota plays an important role in humans as well as rodents[1-3]. In addition, gut microbiota contribute to energy storage in the liver. Bäckhed et al[4] clearly showed that conventionally raised mice had a 42% higher body fat as well as hepatic triglyceride content than germ-free mice despite the fact that conventionally raised mice consuming fewer calories. Supporting the role of gut microbiota in nutritional absorption, germ-free mice in which gut microbiota from conventionally raised mice were transplanted produced a 57% increase in body fat within 2 wk. Certain gut bacteria are able to ferment complex carbohydrates, which are not digested by mammalian enzymes. Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which are digested products of complex carbohydrates, account for 10% of dairy energy intake[5] and also stimulate de novo lipogenesis[6]. Thus, gut microbiota contribute to the development of NAFLD.

In addition to nutritional absorption and energy storage, the gut microbiota are a source of Toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands, which induce inflammation under certain conditions. Although bacterial components are potent TLR ligands, the liver has a high tolerance to TLR ligands because hepatic cells express minimal TLRs in normal liver. In contrast, TLR signaling is activated and downstream molecules are increased in NAFLD because the tolerance has been disrupted[7]. Altered gut microbiota and increased gut permeability are potential causes of the breakdown of tolerance. Indeed, circulating bacterial components and hepatic TLR expression are increased in human NAFLD patients as well as in animal models[8-11]. Thus, gut microbiota and TLRs are potential targets for NAFLD treatment.

The exact mechanisms by which gut microbiota contribute to NAFLD are poorly understood, although the role of gut microbiota in the development of NAFLD is well documented. Here, we first review the role of TLRs that are associated with NAFLD. Then we describe the function of gut microbiota observed in metabolic syndromes including NAFLD.

TLRS ARE ASSOCIATED WITH THE DEVELOPMENT OF NAFLD

TLRs are pattern recognition receptors that perceive bacterial and viral components[12,13]. TLR signaling is suppressed in healthy liver but is activated when pathogenic microorganisms and bacteria-derived molecules are delivered to the liver. This TLR signaling is the first line of defense against the invading pathogens through the production of anti-bacterial and anti-viral cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α, interleukin (IL)-1β, and interferons. However, sustained elevation of these cytokines injures the host; thus, continuous stimulation of TLR signaling does not always provide a benefit for the host. Recent data demonstrate that TLR signaling enhances hepatic injury in NASH, alcoholic liver disease, and chronic viral hepatitis[14-16]. Among the 13 TLRs identified in mammals, the pathogenesis of NASH is associated with TLRs including TLR2, TLR4, TLR5, and TLR9[14,17-20], which recognize lipopolysaccharide (LPS), peptidoglycan, flagellin, and bacterial DNA, respectively. Table 1 summarizes the results of TLR mutant mice fed a diet that induce NAFLD. Although other TLRs may contribute to the development of NAFLD, no solid data are available.

Table 1.

Toll-like receptor mutant mice and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

| Mice | Diet | Duration | Steatosis | Inflammation | Fibrosis | Ref. |

| TLR2 KO | MCD | 5 wk | Identical | Worsen | N/A | [17] |

| TLR2 KO | MCD | 8 wk | Worsen | Worsen | N/A | [18] |

| TLR2 KO | CDAA | 22 wk | Identical | Improved | Improved | [48] |

| TLR2 KO | HF | 20 wk | Improved | Improved | N/A | [46] |

| TLR2 KO | HF | 5 wk | Improved | Improved | N/A | [47] |

| TLR4 mu | MCD | 3 wk | Improved | Improved | N/A | [9] |

| TLR4 KO | MCD | 8 wk | Improved | Improved | Improved | [19] |

| TLR4 mu | HF | 22 wk | Improved | N/A | N/A | [26] |

| TLR4 mu | Fru | 8 wk | Improved | Improved | N/A | [10] |

| TLR5 KO | ST | Worsen | Worsen | N/A | [20] | |

| TLR9 KO | CDAA | 22 wk | Improved | Improved | Improved | [14] |

Assessment of toll-like receptor (TLR) mutant mice were compared with control (WT) mice. CDAA: Choline-deficient amino-acid defined; Fru: Fructose-rich; HF: High fat; MCD: Methionine and choline deficient.

TLR4 is a receptor for LPS, which is a cell component of Gram-negative bacteria. Circulating LPS levels are elevated in rodent NAFLD induced by a high-fat (HF) diet, fructose-rich diet, methionine/choline-deficient (MCD) diet or choline-deficient amino acid-defined (CDAA) diet[9,11,19,21]. Although the mechanism by which these diets induce steatosis is different, these diets modify the gut microbiota and gut permeability[22,23]. Wild type (WT) mice on these diets show steatosis/steatohepatitis with increased expression of TLR4 and proinflammatory cytokines. LPS injections in NAFLD mice further increased proinflammatory cytokines and promoted liver injury[24,25]. Even in WT mice on standard laboratory chow, continuous infusion of low-dose LPS resulted in hepatic steatosis, hepatic insulin resistance, and hepatic weight gain[21]. Supporting the role of the LPS-TLR4 pathway in the development of NAFLD, TLR4 mutant mice are resistant to NAFLD[9,19,26], even though LPS levels are equivalent to those in WT mice. Consistent with histological findings in the liver, the expression of proinflammatory cytokines was suppressed in TLR4 mutant mice. Because 80% of intravenously injected LPS accumulates in the liver within 20-30 min[27,28], the liver is a target of LPS. In humans, plasma LPS levels are also elevated in metabolic syndromes including diabetes[29,30] and in NAFLD patients[31,32]. As in rodents, an HF diet elevates plasma endotoxin concentrations and endotoxin activity in humans[33,34]. Total parenteral nutrition and intestinal bypass surgery can increase plasma LPS levels. Under these conditions, hepatic steatosis occured without metabolic syndrome[35-37]. Antibiotics treatment to kill Gram-negative bacteria decreased plasma LPS levels and attenuated the steatosis in these patients[35-37]. Thus, LPS is closely associated with the development of NAFLD, and TLR4 signaling is a key pathway for the progression of NAFLD in humans as well as rodents.

TLR9 recognizes DNA containing an unmethylated-CpG motif, which is rich in bacterial DNA[12,13]. TLR9 expression in the liver is increased in several types of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) models[14,38,39], and bacterial DNA is detected in blood and ascites samples from advanced cirrhosis patients[40,41]. We have demonstrated that bacterial DNA is detectable in the blood in CDAA-fed mice but not in control diet-fed mice[14]. To investigate the role of TLR9, WT mice and TLR9 deficient mice were fed a CDAA diet to induce steatohepatitis. TLR9 deficient mice on the CDAA diet showed less steatosis, inflammation, and liver fibrosis compared with their WT counterparts. In addition, insulin resistance and weight gain induced by the CDAA diet were suppressed in TLR9 deficient mice[14]. A TLR9 ligand evokes inflammasome-associated liver injury[42,43], which is activated in human NASH compared with chronic hepatitis C[44]. Consistent with the in vivo experiments results, TLR9 signaling is associated with inflammasome expression in WT macrophages[14,45], resulting in the production of IL-1β. These data indicate that TLR9 signaling promotes the progression of NASH.

TLR2 perceives components of Gram-positive bacterial cell walls such as peptidoglycan and lipoteichoic acid[12,13]. The levels of Firmicutes, which are Gram-positive bacteria and a major component of the gut microbiota, are increased in mice on an HF diet, suggesting that TLR2 ligands are rich in gut microbiota in obese mice. Blockade of TLR2 signaling prevents insulin resistance induced by an HF diet in mice[46,47]. We have shown that TLR2 deficient mice are resistant to CDAA-induced steatohepatitis[48]. TLR2 deficient mice on a CDAA diet showed lower expression of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNFα and IL-1β. In in vitro experiments, TLR2 ligands induced proinflammatory cytokines in WT macrophages.

In contrast, TLR2-deficient mice on an MCD diet exhibit equivalent or more severe steatohepatitis as a result of hypersensitivity to LPS[17,18]. Although the MCD diet induces typical features of steatohepatitis, metabolic parameters are completely different; mice on MCD lose weight with increased insulin sensitivity, whereas mice on an HF or CDAA diet gain weight accompanied by insulin resistance. The difference in gut microbiota may account for the contrasting results in the role of TLR2 ligands.

TLR5 is a receptor for bacterial flagellin. Although the role of hepatic TLR5 expression remains unknown, its expression on intestinal mucosa plays critical roles in the development of metabolic syndrome. The first report on TLR5 showed that a lack of TLR5 in mice resulted in spontaneous colitis[49], indicating that TLR5 plays a protective role in the intestinal epithelium. A rederived line of TLR5 KO mice developed obesity and steatosis[20]. A striking finding in TLR5 KO mice is the alteration in gut microbiota at the species level. Transfer of TLR5 KO microbiota to WT germ-free mice reproduced the metabolic syndrome. On the other hand, TLR5 deficient mice from different animal colonies show no basal inflammation and metabolic syndrome under normal conditions[50]. These data suggest that the interplay between TLR5 and specific gut microbiota contributes to the development of metabolic syndrome.

PROINFLAMMATORY CYTOKINES IN NAFLD

Proinflammatory cytokines such as TNFα and IL-1β are downstream targets of TLRs and have been shown to promote the progression of NAFLD in animal models. For instance, TNFα signaling deficiency was resistant to NAFLD induced by an HF diet[51] or MCD diet[52]. Additionally, mice that were deficient in IL-1β signaling were protected from HF diet-induced fatty liver[53] or CDAA diet-induced NASH[14]. In addition, mice that were deficient in inflammasome components and caspase-1, which converts the pro-form of IL-1β to its active form, were also resistant to steatosis/steatohepatitis in NAFLD models[54,55]. These data indicate that TNFα and IL-1β are important mediators in the development of NAFLD. Because NAFLD patients show increased expressions of these cytokines as well as their receptors[56-58], these molecules are potential targets for NAFLD treatment.

TNFα regulates lipid metabolism and hepatocyte cell death. TNFα impairs insulin signaling by inhibiting insulin receptors and insulin receptor substrate-1[59], resulting in insulin resistance with elevated insulin levels. Insulin resistance increases fatty acid release from adipose tissue and inhibits free fatty acid (FFA) uptake in adipocytes. On the other hand, elevated insulin concentration facilitates FFA flux into hepatocytes and hepatic lipogenesis[60]. Moreover, TNFα promotes cholesterol accumulation in hepatocytes by increasing cholesterol uptake through LDL receptors and by decreasing the efflux through lipid transporting genes such as ABCA1[61]. Lipid-accumulated hepatocytes are more sensitive to TNFα-mediated cell death[62,63]. Although TNFα does not induce apoptosis in normal hepatocytes by inducing nuclear factor κB (NF-κB)-related anti-apoptotic genes[64], excessive lipid levels in hepatocytes alter the cell survival signals. For instance, lipid-accumulated hepatocytes generate reactive oxygen species[62] and show increased gene expression of ASK-1 and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK)[63], which drive cell death signaling.

IL-1β also mediates the features of NAFLD including steatosis[14,53] and hepatocyte death[14]. IL-1β regulates lipid metabolism by suppressing PPARα and its downstream molecules, resulting in hepatic accumulation of triglycerides[65]. On the other hand, IL-1β increases the expression of diacylglycerol acyltransferase 2, an enzyme that converts diglycerides to triglycerides[14]. Thus, IL-1β promotes triglycerides accumulation in hepatocytes. IL-1β contributes to hepatocyte death when hepatocytes are laden with lipids. Pro-apoptotic genes such as Bax are induced in lipid-accumulated hepatocytes upon IL-1β stimulation, whereas anti-apoptotic genes are increased in normal hepatocytes[14].

A major source of these proinflammatory cytokines is macrophages in the liver because macrophage depletion by liposomal clodronate causes low expression of TNFα and IL-1β[9,66]. In addition, mice deficient in TLR2, TLR4, and TLR9 exhibit low expression of proinflammatory cytokines even when these mice were fed a CDAA or MCD diet[9,14,48]. For a detailed analysis of hepatic macrophages, we generated chimeric mice in which WT mice and TLR2 deficient mice were reconstituted with TLR2 deficient macrophages and WT macrophages, respectively. Using a combination of macrophage depletion and bone marrow transplantation, more than 90% of the macrophages were successfully reconstituted by transplanted macrophages[11,15,67]. Chimeric mice reconstituted with TLR2 deficient macrophages reduced inflammation and liver fibrosis[48]. These data indicate that TLR2 on macrophages contribute not only to inflammation but also to liver fibrosis. Recent data show that TNFα and IL-1 produced by hepatic macrophages contribute to liver fibrosis by promoting the survival of activated hepatic stellate cells[68]. Indeed, IL-1β induces pro-fibrogenic genes in hepatic stellate cells[14,69,70]. These data indicate that hepatic macrophages contribute to the pathogenesis of NAFLD by TLR-mediated proinflammatory cytokine production.

COMPOSITIONAL CHANGE IN GUT MICROBIOTA IN OBESITY AND NAFLD

Because gut microbiota are a source of TLR ligands, their compositional change is a potential trigger in the activation of TLR signaling in the liver. Thus, there has been extensive research aimed at identifying the specific bacteria changes that lead to NAFLD. At least following nine microbacteria phyla reside in the gut: Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Cyanobacteria, Deferribacteres, Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, Tenericutes, TM7, and Verrucomicrobia. Of them, Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes are major components of gut microbiota at the phylum level in rodents and humans[71]. Table 2 shows the classification based on the Gram staining. Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, and Verrucomicrobia are minor phyla compared with Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes. Currently, there is insufficient information on TM7, Deferribacteres, Cyanobacteria and Tenericutes in metabolic syndrome.

Table 2.

Classification of gut microbiota based on Gram staining

| Gram-positive bacteria | Gram-negative bacteria | Unclassified |

| Actinobacteria | Bacteroidetes | Deferribacteres |

| Firmicutes | Cyanobacteria | Tenericutes |

| TM7 | Verrucomicrobia |

Most studies have shown that the levels of Firmicutes are increased whereas those of Bacteroidetes are decreased in obesity and its related diseases[72-74] in humans as well as rodents; thus, an increased Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio is a potential phenotype of obesity. In addition, the levels of Bacteroidetes were increased by interventions aimed at weight reduction, including prebiotics treatment[75] and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) surgery[76] in obese mice. These data suggest that Bacteroidetes are likely to have beneficial effects on obesity. On the other hand, transplantation of commensal Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron into germ-free mice induced a 23% increase in body fat[4]. It remains unclear whether the compositional change is a cause or result of obesity. To date, the role of Bacteroidetes in metabolic syndrome remains unknown. If a high Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio is a feature of obesity, one may speculate that a larger amount of TLR2 ligands is delivered to the liver because Firmicutes are Gram-positive bacteria. Indeed, TLR2 deficient mice were resistant to NAFLD induced by an HF diet, which increases Firmicutes. On the other hand, mice on an MCD diet, a NASH model that exhibits weight loss, showed an increase in the levels of Gram-negative bacteria of the Bacteroidetes fragilis group[22], suggesting that TLR4 ligands are increased. As expected, TLR4 mutant mice were protected from NASH induced by an MCD diet[9,19]. Although the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio is likely to be correlated with the amount of TLR2 and TLR4 ligands, the association between gut microbiota and TLRs is not so simple. For instance, TLR4 deficient mice are also resistant to NAFLD induced by an HF diet, which increases the levels of Gram-positive bacteria. Detailed analysis showed that an HF diet increased the abundance of some minor Gram-negative bacteria such as Desulfovibrionaceae and Enterobacteriaceae[21,77]. Although both of these bacteria belong to a minor phylum, Proteobacteria, they are a potential source of LPS[78,79]. In addition, Desulfovibrionaceae can disrupt the gut barrier[80], suggesting that these bacteria contribute to the pathogenesis of NAFLD, even at low levels. In vitro experiments indicate that LPS stimulates TLR4 at low concentrations compared with a TLR2 ligand. Thus, minor populations of gut microbiota may participate in the hepatic inflammation in the setting of an HF diet.

Proteobacteria, a phylum of Gram-negative bacteria, includes several pathogenic bacteria such as Escherichia coli, Salmonella, Vibrio parahaemolyticus, and Helicobacter pylori. In obese humans and mice, the levels of Proteobacteria are increased in their abundance. On the other hand, the Proteobacteria phylum was also increased after RYGB surgery[76]. Because the Proteobacteria phylum includes both non-harmful and pathogenic bacteria, further investigation is required to determine the role of Proteobacteria in the development of NAFLD.

The Verrucomicrobia phylum includes mucin-degrading bacteria Akkermansia muciniphila residing in the mucus layer of the intestine, which represents 3%-5% of the microbial community of healthy humans[81,82]. Recent studies showed that the proportion of Akkermansia muciniphila was decreased in the obese and was inversely correlated with body weight in rodents and humans[75,83-85]. Cani et al[75] intensively investigated the role of Akkermansia muciniphila in obese mice. Probiotic treatment significantly increased the abundance of Akkermansia muciniphila and improved metabolic parameters in obese mice models. In addition, Akkermansia muciniphila treatment reversed fat gain, serum LPS levels, gut barrier function, and insulin resistance by increasing endocannabinoids and gut peptides. Shin et al[86] reported that metformin, an anti-diabetic agent, increased the abundance of Akkermansia muciniphila, in which Treg cells improve insulin signaling. Furthermore, RYGB surgery increases the levels of Akkermansia muciniphila[76]. These data suggest that Akkermansia muciniphila has potential as a probiotics.

GUT MICROBIOTA IN OBESE CHILDREN

The incidence of NAFLD in children is also considerably increasing worldwide[87]; therefore, examination of gut microbiota has been extended to children. Mixed data were shown regarding Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes between normal and obese children: Xu et al[88] reported an increased levels of Firmicutes and an increased Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio in obese individuals, whereas Zhu et al[89] showed increased levels of Bacteroidetes and an increased Bacteroidetes/Firmicutes ratio. These studies were conducted in different countries, i.e., China and the United States. A report from Egypt further demonstrated different results[90], suggesting that the composition of gut microbiota may depend on the environment, particularly in children.

Zhu et al[89] further investigated the compositional changes in gut microbiota and focused on the function of the Proteobacteria phylum. Among the Proteobacteria phylum, the levels of Escherichia were significantly increased in NASH compared with those in obese children. They also found higher plasma ethanol levels in NASH children. They speculated that Escherichia produced ethanol in the gut because in vitro experiments showed that Escherichia could generate ethanol. However, it is unclear whether an increase in Escherichia is a common mechanism of adult NASH. RYBS surgery increased the abundance of Escherichia in the gut, although obesity and metabolic parameters were improved. Thus, the effect of Escherichia on the development of NASH may be different between children and adults. Similarly, the abundance of Desulfovibrio, a source of LPS, was decreased in obese children[84] whereas this species was increased by an HF diet[21,77].

PROBIOTICS AND NAFLD

Probiotics are live microorganisms that have beneficial effects on health. Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus are widely used as probiotics because these bacteria can inhibit an expansion of Gram-negative pathogenic bacteria by producing lactic acid and other antimicrobial substances. Although these probiotic bacteria generally reside in the gut, the population of probiotic bacteria decreases in pathogenic conditions. Indeed, the levels of Bifidobacterium, a member of the Actinobacteria phylum, are decreased in rodent NAFLD models[21,22,77] as well as in humans[89]. Thus, probiotic supplementation is expected to reverse the phenotype of gut microbiota, leading to improved health. There are many reports on the beneficial effects of probiotics such as Bifidobacterium spp. in rodents. Administration of Bifidobacterium spp improves metabolic parameters including cholesterol levels, visceral fat weight, and insulin resistance[91,92]. The Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota, a member of Firmicutes, protects against NASH induced by an MCD diet in mice[22] and steatosis induced by a fructose-rich diet[93]. VSL#3 is a probiotic that consists eight strains of bacteria including Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium species. VSL#3 administration ameliorates the grade of NAFLD in ApoE-/- mice or HFD-fed rats[94,95]. Probiotics suppress inflammatory indicators including serum LPS levels and hepatic TNFα expression in rodents[22,94,95]. In addition to compositional changes in gut microbiota, probiotics regulate gut permeability, which is enhanced in NAFLD. There are several junctions between intestinal epithelial cells to control barrier functions, including tight junctions, adherence junctions, gap junctions, and desmosomes. Of them, the tight junction is thought to play a central role in intestinal barrier function[5]. The expression of tight junction proteins such as ZO-1 and occludin decreased in murine models of NAFLD[96,97]. Several probiotic bacteria can strengthen barrier function by increasing the expression of tight junction proteins. For instance, the probiotics Bifidobacterium lactis 420, Escherichia coli Nissle 1917, and Lactobacillus plantarum increased tight junction proteins and preserved barrier function in DSS-induced colitis[98-100]. Probiotics also suppress the production of proinflammatory cytokines including TNFα, IL-1, and IFN-γ, which can disrupt tight junctions[101].

A question arises as to whether probiotic treatment may also supply TLR ligands including TLR2 and TLR9. Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium are Gram-positive bacteria and contain TLR2 ligands such as peptidoglycan and lipoteichoic acid. Interestingly, probiotic treatment increased anti-inflammatory cytokines in a TLR2-dependent manner[102]. Clostridium butyricum induced IL-10 production from intestinal macrophages in acute experimental colitis through TLR2[103]. These data suggest that TLR2 has a dual function: TLR2 ligands from probiotic bacteria direct an anti-inflammatory state, whereas TLR2 ligands from obesity-related bacteria induce inflammation. Probiotic bacteria also contain an unmethylated-CpG motif, which is a TLR9 ligand. Indeed, the CpG-motif, which is abundant in Bifidobacterium species, can drive a murine macrophage cell line to produce TNFα and MCP-1[104], which are mediators that promote the progression of NASH[66]. On the other hand, most probiotic bacteria are not able to produce TLR9-mediated IFN-γ in myeloid dendritic cells except for limited strains[105], suggesting that the response to TLR9 ligands in immune cells may differ among bacteria. Collectively, the TLR ligands derived from probiotics may suppress inflammation partially through the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines.

PREBIOTICS AND NAFLD

Prebiotics are indigestible food ingredients including inulin and fructooligosaccharides, which have beneficial effects by altering the composition of gut microbiota, lipid metabolism, and gut barrier function. Although mammalian enzymes cannot digest complex carbohydrates, certain gut microbiota are able to ferment the carbohydrates to SCFAs such as acetate, propionate, and butyrate. These SCFAs are used as energy[106,107] as well as molecules to stimulate lipogenesis and gluconeogenesis. Interestingly, SCFAs protect mice from obesity induced by diet or gene modification[108-110]. Acetate is a substrate for middle- to long- chain fatty acids[107] that stimulates hepatic lipogenesis, and the incorporation of acetate to these fatty acids did not occur under fasting conditions[111].

SCFAs can strengthen the barrier function of the intestine. For instance, butyrate restores the mucosal barrier in heat- or detergent-induced colonic injury[112]. In addition, treatment with MIYARI 588, a butyrate-producing probiotics, suppressed gut permeability by increasing the expression of tight junction proteins in mice fed a CDAA diet. As a result, elevation of LPS was inhibited, and steatohepatitis was ameliorated[23]. The probiotic Lactobacillus plantarum 299v showed beneficial effects by elevating butyrate concentrations in patients with recurrent Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea. Although the levels of butyrate-producing bacteria in NASH remain unknown, the relative proportion of butyrate-producing bacteria is decreased in type 2 diabetes[113,114].

PERSPECTIVES

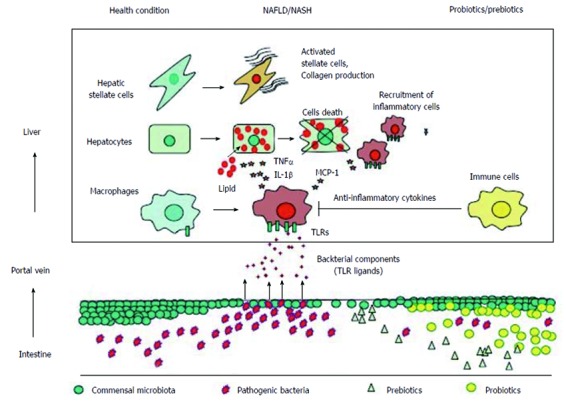

Accumulating evidence demonstrates that gut microbiota and TLR signaling are closely associated with the development of NAFLD. Figure 1 summarizes the association between gut microbiota and TLRs and potential effects of prebiotics and probiotics in NAFLD. To data, inconsistent data have been generated regarding the composition of gut microbiota at the phylum level in NAFLD patients because of environmental and interindividual diversity. In addition, studies that show beneficial effects of probiotics and prebiotics are based on small sample sizes. Because certain gut microbiota are likely to contribute to the development of NAFLD by regulating the intestinal barrier function, additional analyses should be performed to confirm their role in NAFLD. In the near future, further information will be provided by metagenomic analysis of gut microbiota in NAFLD. This information will inform NAFLD treatments through worldwide trials.

Figure 1.

Gut-liver axis in the development of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Under healthy conditions, commensal microbiota inhibit the expansion of pathogenic bacteria and maintain the barrier function of the intestinal epithelium. In nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), the levels of pathogenic bacteria may increase, and the barrier function is disrupted by multiple mechanisms, leading to a translocation of bacteria components [toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands] into the portal vein. TLR ligands stimulate TLR expressing cells, such as macrophages, to produce proinflammatory cytokines including tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) and interleukin-1b (IL-1b), which promote lipid accumulation as well as hepatocyte cell death. TLR ligands also stimulate macrophages to produce chemokines such as MCP-1, which recruits inflammatory macrophages. These proinflammatory cytokines and certain TLR ligands directly stimulate hepatic stellate cells to produce fibrogenic factors. In contrast, treatments with probiotics or prebiotics protects against the translocation of TLR ligands and the expansion of pathogenic bacteria. In addition, probiotics/prebiotics stimulate immune cells to produce anti-inflammatory cytokines.

Footnotes

Supported by JSPS [Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C)] (to Miura K)

P- Reviewers: Takayama F, Nowicki MJ, Schlegel A S- Editor: Wen LL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu XM

References

- 1.Tremaroli V, Bäckhed F. Functional interactions between the gut microbiota and host metabolism. Nature. 2012;489:242–249. doi: 10.1038/nature11552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DiBaise JK, Zhang H, Crowell MD, Krajmalnik-Brown R, Decker GA, Rittmann BE. Gut microbiota and its possible relationship with obesity. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83:460–469. doi: 10.4065/83.4.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tennyson CA, Friedman G. Microecology, obesity, and probiotics. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2008;15:422–427. doi: 10.1097/MED.0b013e328308dbfb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bäckhed F, Ding H, Wang T, Hooper LV, Koh GY, Nagy A, Semenkovich CF, Gordon JI. The gut microbiota as an environmental factor that regulates fat storage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:15718–15723. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407076101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conterno L, Fava F, Viola R, Tuohy KM. Obesity and the gut microbiota: does up-regulating colonic fermentation protect against obesity and metabolic disease? Genes Nutr. 2011;6:241–260. doi: 10.1007/s12263-011-0230-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zambell KL, Fitch MD, Fleming SE. Acetate and butyrate are the major substrates for de novo lipogenesis in rat colonic epithelial cells. J Nutr. 2003;133:3509–3515. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.11.3509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miyake Y, Yamamoto K. Role of gut microbiota in liver diseases. Hepatol Res. 2013;43:139–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2012.01088.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsukumo DM, Carvalho-Filho MA, Carvalheira JB, Prada PO, Hirabara SM, Schenka AA, Araújo EP, Vassallo J, Curi R, Velloso LA, et al. Loss-of-function mutation in Toll-like receptor 4 prevents diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2007;56:1986–1998. doi: 10.2337/db06-1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rivera CA, Adegboyega P, van Rooijen N, Tagalicud A, Allman M, Wallace M. Toll-like receptor-4 signaling and Kupffer cells play pivotal roles in the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J Hepatol. 2007;47:571–579. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spruss A, Kanuri G, Wagnerberger S, Haub S, Bischoff SC, Bergheim I. Toll-like receptor 4 is involved in the development of fructose-induced hepatic steatosis in mice. Hepatology. 2009;50:1094–1104. doi: 10.1002/hep.23122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kodama Y, Kisseleva T, Iwaisako K, Miura K, Taura K, De Minicis S, Osterreicher CH, Schnabl B, Seki E, Brenner DA. c-Jun N-terminal kinase-1 from hematopoietic cells mediates progression from hepatic steatosis to steatohepatitis and fibrosis in mice. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1467–1477.e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.06.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawai T, Akira S. The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: update on Toll-like receptors. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:373–384. doi: 10.1038/ni.1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kawai T, Akira S. The roles of TLRs, RLRs and NLRs in pathogen recognition. Int Immunol. 2009;21:317–337. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxp017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miura K, Kodama Y, Inokuchi S, Schnabl B, Aoyama T, Ohnishi H, Olefsky JM, Brenner DA, Seki E. Toll-like receptor 9 promotes steatohepatitis by induction of interleukin-1beta in mice. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:323–324.e7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.03.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inokuchi S, Tsukamoto H, Park E, Liu ZX, Brenner DA, Seki E. Toll-like receptor 4 mediates alcohol-induced steatohepatitis through bone marrow-derived and endogenous liver cells in mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35:1509–1518. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01487.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dhillon N, Walsh L, Krüger B, Ward SC, Godbold JH, Radwan M, Schiano T, Murphy BT, Schröppel B. A single nucleotide polymorphism of Toll-like receptor 4 identifies the risk of developing graft failure after liver transplantation. J Hepatol. 2010;53:67–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Szabo G, Velayudham A, Romics L, Mandrekar P. Modulation of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis by pattern recognition receptors in mice: the role of toll-like receptors 2 and 4. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:140S–145S. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000189287.83544.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rivera CA, Gaskin L, Allman M, Pang J, Brady K, Adegboyega P, Pruitt K. Toll-like receptor-2 deficiency enhances non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2010;10:52. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-10-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Csak T, Velayudham A, Hritz I, Petrasek J, Levin I, Lippai D, Catalano D, Mandrekar P, Dolganiuc A, Kurt-Jones E, et al. Deficiency in myeloid differentiation factor-2 and toll-like receptor 4 expression attenuates nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and fibrosis in mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2011;300:G433–G441. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00163.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vijay-Kumar M, Aitken JD, Carvalho FA, Cullender TC, Mwangi S, Srinivasan S, Sitaraman SV, Knight R, Ley RE, Gewirtz AT. Metabolic syndrome and altered gut microbiota in mice lacking Toll-like receptor 5. Science. 2010;328:228–231. doi: 10.1126/science.1179721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cani PD, Amar J, Iglesias MA, Poggi M, Knauf C, Bastelica D, Neyrinck AM, Fava F, Tuohy KM, Chabo C, et al. Metabolic endotoxemia initiates obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2007;56:1761–1772. doi: 10.2337/db06-1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okubo H, Sakoda H, Kushiyama A, Fujishiro M, Nakatsu Y, Fukushima T, Matsunaga Y, Kamata H, Asahara T, Yoshida Y, et al. Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota protects against nonalcoholic steatohepatitis development in a rodent model. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2013;305:G911–G918. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00225.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Endo H, Niioka M, Kobayashi N, Tanaka M, Watanabe T. Butyrate-producing probiotics reduce nonalcoholic fatty liver disease progression in rats: new insight into the probiotics for the gut-liver axis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e63388. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Imajo K, Fujita K, Yoneda M, Nozaki Y, Ogawa Y, Shinohara Y, Kato S, Mawatari H, Shibata W, Kitani H, et al. Hyperresponsivity to low-dose endotoxin during progression to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is regulated by leptin-mediated signaling. Cell Metab. 2012;16:44–54. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kudo H, Takahara T, Yata Y, Kawai K, Zhang W, Sugiyama T. Lipopolysaccharide triggered TNF-alpha-induced hepatocyte apoptosis in a murine non-alcoholic steatohepatitis model. J Hepatol. 2009;51:168–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Poggi M, Bastelica D, Gual P, Iglesias MA, Gremeaux T, Knauf C, Peiretti F, Verdier M, Juhan-Vague I, Tanti JF, et al. C3H/HeJ mice carrying a toll-like receptor 4 mutation are protected against the development of insulin resistance in white adipose tissue in response to a high-fat diet. Diabetologia. 2007;50:1267–1276. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0654-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mathison JC, Ulevitch RJ. The clearance, tissue distribution, and cellular localization of intravenously injected lipopolysaccharide in rabbits. J Immunol. 1979;123:2133–2143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ruiter DJ, van der Meulen J, Brouwer A, Hummel MJ, Mauw BJ, van der Ploeg JC, Wisse E. Uptake by liver cells of endotoxin following its intravenous injection. Lab Invest. 1981;45:38–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Creely SJ, McTernan PG, Kusminski CM, Fisher fM, Da Silva NF, Khanolkar M, Evans M, Harte AL, Kumar S. Lipopolysaccharide activates an innate immune system response in human adipose tissue in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;292:E740–E747. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00302.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pussinen PJ, Havulinna AS, Lehto M, Sundvall J, Salomaa V. Endotoxemia is associated with an increased risk of incident diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:392–397. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alisi A, Manco M, Devito R, Piemonte F, Nobili V. Endotoxin and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 serum levels associated with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;50:645–649. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181c7bdf1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harte AL, da Silva NF, Creely SJ, McGee KC, Billyard T, Youssef-Elabd EM, Tripathi G, Ashour E, Abdalla MS, Sharada HM, et al. Elevated endotoxin levels in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Inflamm (Lond) 2010;7:15. doi: 10.1186/1476-9255-7-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ghanim H, Abuaysheh S, Sia CL, Korzeniewski K, Chaudhuri A, Fernandez-Real JM, Dandona P. Increase in plasma endotoxin concentrations and the expression of Toll-like receptors and suppressor of cytokine signaling-3 in mononuclear cells after a high-fat, high-carbohydrate meal: implications for insulin resistance. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:2281–2287. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pendyala S, Walker JM, Holt PR. A high-fat diet is associated with endotoxemia that originates from the gut. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:1100–1101.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.01.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pappo I, Becovier H, Berry EM, Freund HR. Polymyxin B reduces cecal flora, TNF production and hepatic steatosis during total parenteral nutrition in the rat. J Surg Res. 1991;51:106–112. doi: 10.1016/0022-4804(91)90078-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pappo I, Bercovier H, Berry EM, Haviv Y, Gallily R, Freund HR. Polymyxin B reduces total parenteral nutrition-associated hepatic steatosis by its antibacterial activity and by blocking deleterious effects of lipopolysaccharide. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1992;16:529–532. doi: 10.1177/0148607192016006529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Drenick EJ, Fisler J, Johnson D. Hepatic steatosis after intestinal bypass--prevention and reversal by metronidazole, irrespective of protein-calorie malnutrition. Gastroenterology. 1982;82:535–548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gäbele E, Dostert K, Hofmann C, Wiest R, Schölmerich J, Hellerbrand C, Obermeier F. DSS induced colitis increases portal LPS levels and enhances hepatic inflammation and fibrogenesis in experimental NASH. J Hepatol. 2011;55:1391–1399. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roth CL, Elfers CT, Figlewicz DP, Melhorn SJ, Morton GJ, Hoofnagle A, Yeh MM, Nelson JE, Kowdley KV. Vitamin D deficiency in obese rats exacerbates nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and increases hepatic resistin and Toll-like receptor activation. Hepatology. 2012;55:1103–1111. doi: 10.1002/hep.24737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guarner C, González-Navajas JM, Sánchez E, Soriando G, Francés R, Chiva M, Zapater P, Benlloch S, Muñoz C, Pascual S, et al. The detection of bacterial DNA in blood of rats with CCl4-induced cirrhosis with ascites represents episodes of bacterial translocation. Hepatology. 2006;44:633–639. doi: 10.1002/hep.21286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Francés R, Zapater P, González-Navajas JM, Muñoz C, Caño R, Moreu R, Pascual S, Bellot P, Pérez-Mateo M, Such J. Bacterial DNA in patients with cirrhosis and noninfected ascites mimics the soluble immune response established in patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Hepatology. 2008;47:978–985. doi: 10.1002/hep.22083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Imaeda AB, Watanabe A, Sohail MA, Mahmood S, Mohamadnejad M, Sutterwala FS, Flavell RA, Mehal WZ. Acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in mice is dependent on Tlr9 and the Nalp3 inflammasome. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:305–314. doi: 10.1172/JCI35958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jiang W, Sun R, Zhou R, Wei H, Tian Z. TLR-9 activation aggravates concanavalin A-induced hepatitis via promoting accumulation and activation of liver CD4+ NKT cells. J Immunol. 2009;182:3768–3774. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0800973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Csak T, Ganz M, Pespisa J, Kodys K, Dolganiuc A, Szabo G. Fatty acid and endotoxin activate inflammasomes in mouse hepatocytes that release danger signals to stimulate immune cells. Hepatology. 2011;54:133–144. doi: 10.1002/hep.24341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huang H, Chen HW, Evankovich J, Yan W, Rosborough BR, Nace GW, Ding Q, Loughran P, Beer-Stolz D, Billiar TR, et al. Histones activate the NLRP3 inflammasome in Kupffer cells during sterile inflammatory liver injury. J Immunol. 2013;191:2665–2679. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ehses JA, Meier DT, Wueest S, Rytka J, Boller S, Wielinga PY, Schraenen A, Lemaire K, Debray S, Van Lommel L, et al. Toll-like receptor 2-deficient mice are protected from insulin resistance and beta cell dysfunction induced by a high-fat diet. Diabetologia. 2010;53:1795–1806. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1747-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Himes RW, Smith CW. Tlr2 is critical for diet-induced metabolic syndrome in a murine model. FASEB J. 2010;24:731–739. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-141929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miura K, Yang L, van Rooijen N, Brenner DA, Ohnishi H, Seki E. Toll-like receptor 2 and palmitic acid cooperatively contribute to the development of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis through inflammasome activation in mice. Hepatology. 2013;57:577–589. doi: 10.1002/hep.26081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vijay-Kumar M, Sanders CJ, Taylor RT, Kumar A, Aitken JD, Sitaraman SV, Neish AS, Uematsu S, Akira S, Williams IR, et al. Deletion of TLR5 results in spontaneous colitis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3909–3921. doi: 10.1172/JCI33084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Letran SE, Lee SJ, Atif SM, Flores-Langarica A, Uematsu S, Akira S, Cunningham AF, McSorley SJ. TLR5-deficient mice lack basal inflammatory and metabolic defects but exhibit impaired CD4 T cell responses to a flagellated pathogen. J Immunol. 2011;186:5406–5412. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Salles J, Tardif N, Landrier JF, Mothe-Satney I, Guillet C, Boue-Vaysse C, Combaret L, Giraudet C, Patrac V, Bertrand-Michel J, et al. TNFα gene knockout differentially affects lipid deposition in liver and skeletal muscle of high-fat-diet mice. J Nutr Biochem. 2012;23:1685–1693. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tomita K, Tamiya G, Ando S, Ohsumi K, Chiyo T, Mizutani A, Kitamura N, Toda K, Kaneko T, Horie Y, et al. Tumour necrosis factor alpha signalling through activation of Kupffer cells plays an essential role in liver fibrosis of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in mice. Gut. 2006;55:415–424. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.071118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kamari Y, Shaish A, Vax E, Shemesh S, Kandel-Kfir M, Arbel Y, Olteanu S, Barshack I, Dotan S, Voronov E, et al. Lack of interleukin-1α or interleukin-1β inhibits transformation of steatosis to steatohepatitis and liver fibrosis in hypercholesterolemic mice. J Hepatol. 2011;55:1086–1094. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.01.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stienstra R, van Diepen JA, Tack CJ, Zaki MH, van de Veerdonk FL, Perera D, Neale GA, Hooiveld GJ, Hijmans A, Vroegrijk I, et al. Inflammasome is a central player in the induction of obesity and insulin resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:15324–15329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100255108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dixon LJ, Flask CA, Papouchado BG, Feldstein AE, Nagy LE. Caspase-1 as a central regulator of high fat diet-induced non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e56100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hotamisligil GS, Shargill NS, Spiegelman BM. Adipose expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha: direct role in obesity-linked insulin resistance. Science. 1993;259:87–91. doi: 10.1126/science.7678183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hui JM, Hodge A, Farrell GC, Kench JG, Kriketos A, George J. Beyond insulin resistance in NASH: TNF-alpha or adiponectin? Hepatology. 2004;40:46–54. doi: 10.1002/hep.20280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Salmenniemi U, Ruotsalainen E, Pihlajamäki J, Vauhkonen I, Kainulainen S, Punnonen K, Vanninen E, Laakso M. Multiple abnormalities in glucose and energy metabolism and coordinated changes in levels of adiponectin, cytokines, and adhesion molecules in subjects with metabolic syndrome. Circulation. 2004;110:3842–3848. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000150391.38660.9B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hotamisligil GS, Murray DL, Choy LN, Spiegelman BM. Tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibits signaling from the insulin receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:4854–4858. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.4854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cawthorn WP, Sethi JK. TNF-alpha and adipocyte biology. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:117–131. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.11.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ma KL, Ruan XZ, Powis SH, Chen Y, Moorhead JF, Varghese Z. Inflammatory stress exacerbates lipid accumulation in hepatic cells and fatty livers of apolipoprotein E knockout mice. Hepatology. 2008;48:770–781. doi: 10.1002/hep.22423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Marí M, Caballero F, Colell A, Morales A, Caballeria J, Fernandez A, Enrich C, Fernandez-Checa JC, García-Ruiz C. Mitochondrial free cholesterol loading sensitizes to TNF- and Fas-mediated steatohepatitis. Cell Metab. 2006;4:185–198. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang W, Kudo H, Kawai K, Fujisaka S, Usui I, Sugiyama T, Tsukada K, Chen N, Takahara T. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha accelerates apoptosis of steatotic hepatocytes from a murine model of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;391:1731–1736. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.12.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kodama Y, Taura K, Miura K, Schnabl B, Osawa Y, Brenner DA. Antiapoptotic effect of c-Jun N-terminal Kinase-1 through Mcl-1 stabilization in TNF-induced hepatocyte apoptosis. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1423–1434. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.12.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stienstra R, Saudale F, Duval C, Keshtkar S, Groener JE, van Rooijen N, Staels B, Kersten S, Müller M. Kupffer cells promote hepatic steatosis via interleukin-1beta-dependent suppression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha activity. Hepatology. 2010;51:511–522. doi: 10.1002/hep.23337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Miura K, Yang L, van Rooijen N, Ohnishi H, Seki E. Hepatic recruitment of macrophages promotes nonalcoholic steatohepatitis through CCR2. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2012;302:G1310–G1321. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00365.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Seki E, De Minicis S, Osterreicher CH, Kluwe J, Osawa Y, Brenner DA, Schwabe RF. TLR4 enhances TGF-beta signaling and hepatic fibrosis. Nat Med. 2007;13:1324–1332. doi: 10.1038/nm1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pradere JP, Kluwe J, De Minicis S, Jiao JJ, Gwak GY, Dapito DH, Jang MK, Guenther ND, Mederacke I, Friedman R, et al. Hepatic macrophages but not dendritic cells contribute to liver fibrosis by promoting the survival of activated hepatic stellate cells in mice. Hepatology. 2013;58:1461–1473. doi: 10.1002/hep.26429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Aoki H, Ohnishi H, Hama K, Ishijima T, Satoh Y, Hanatsuka K, Ohashi A, Wada S, Miyata T, Kita H, et al. Autocrine loop between TGF-beta1 and IL-1beta through Smad3- and ERK-dependent pathways in rat pancreatic stellate cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2006;290:C1100–C1108. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00465.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhang YP, Yao XX, Zhao X. Interleukin-1 beta up-regulates tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase-1 mRNA and phosphorylation of c-jun N-terminal kinase and p38 in hepatic stellate cells. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:1392–1396. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i9.1392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bäckhed F, Ley RE, Sonnenburg JL, Peterson DA, Gordon JI. Host-bacterial mutualism in the human intestine. Science. 2005;307:1915–1920. doi: 10.1126/science.1104816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mouzaki M, Comelli EM, Arendt BM, Bonengel J, Fung SK, Fischer SE, McGilvray ID, Allard JP. Intestinal microbiota in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2013;58:120–127. doi: 10.1002/hep.26319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Turnbaugh PJ, Hamady M, Yatsunenko T, Cantarel BL, Duncan A, Ley RE, Sogin ML, Jones WJ, Roe BA, Affourtit JP, et al. A core gut microbiome in obese and lean twins. Nature. 2009;457:480–484. doi: 10.1038/nature07540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ley RE, Turnbaugh PJ, Klein S, Gordon JI. Microbial ecology: human gut microbes associated with obesity. Nature. 2006;444:1022–1023. doi: 10.1038/4441022a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Everard A, Belzer C, Geurts L, Ouwerkerk JP, Druart C, Bindels LB, Guiot Y, Derrien M, Muccioli GG, Delzenne NM, et al. Cross-talk between Akkermansia muciniphila and intestinal epithelium controls diet-induced obesity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:9066–9071. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219451110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Liou AP, Paziuk M, Luevano JM, Machineni S, Turnbaugh PJ, Kaplan LM. Conserved shifts in the gut microbiota due to gastric bypass reduce host weight and adiposity. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:178ra41. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhang C, Zhang M, Wang S, Han R, Cao Y, Hua W, Mao Y, Zhang X, Pang X, Wei C, et al. Interactions between gut microbiota, host genetics and diet relevant to development of metabolic syndromes in mice. ISME J. 2010;4:232–241. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2009.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Loubinoux J, Mory F, Pereira IA, Le Faou AE. Bacteremia caused by a strain of Desulfovibrio related to the provisionally named Desulfovibrio fairfieldensis. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:931–934. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.2.931-934.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Weglarz L, Dzierzewicz Z, Skop B, Orchel A, Parfiniewicz B, Wiśniowska B, Swiatkowska L, Wilczok T. Desulfovibrio desulfuricans lipopolysaccharides induce endothelial cell IL-6 and IL-8 secretion and E-selectin and VCAM-1 expression. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2003;8:991–1003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Beerens H, Romond C. Sulfate-reducing anaerobic bacteria in human feces. Am J Clin Nutr. 1977;30:1770–1776. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/30.11.1770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Belzer C, de Vos WM. Microbes inside--from diversity to function: the case of Akkermansia. ISME J. 2012;6:1449–1458. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2012.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Derrien M, Vaughan EE, Plugge CM, de Vos WM. Akkermansia muciniphila gen. nov., sp. nov., a human intestinal mucin-degrading bacterium. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2004;54:1469–1476. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.02873-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Santacruz A, Collado MC, García-Valdés L, Segura MT, Martín-Lagos JA, Anjos T, Martí-Romero M, Lopez RM, Florido J, Campoy C, et al. Gut microbiota composition is associated with body weight, weight gain and biochemical parameters in pregnant women. Br J Nutr. 2010;104:83–92. doi: 10.1017/S0007114510000176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Karlsson CL, Onnerfält J, Xu J, Molin G, Ahrné S, Thorngren-Jerneck K. The microbiota of the gut in preschool children with normal and excessive body weight. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2012;20:2257–2261. doi: 10.1038/oby.2012.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Collado MC, Isolauri E, Laitinen K, Salminen S. Distinct composition of gut microbiota during pregnancy in overweight and normal-weight women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88:894–899. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/88.4.894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Shin NR, Lee JC, Lee HY, Kim MS, Whon TW, Lee MS, Bae JW. An increase in the Akkermansia spp. population induced by metformin treatment improves glucose homeostasis in diet-induced obese mice. Gut. 2014;63:727–735. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ovchinsky N, Lavine JE. A critical appraisal of advances in pediatric nonalcoholic Fatty liver disease. Semin Liver Dis. 2012;32:317–324. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1329905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Xu P, Li M, Zhang J, Zhang T. Correlation of intestinal microbiota with overweight and obesity in Kazakh school children. BMC Microbiol. 2012;12:283. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-12-283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zhu L, Baker SS, Gill C, Liu W, Alkhouri R, Baker RD, Gill SR. Characterization of gut microbiomes in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) patients: a connection between endogenous alcohol and NASH. Hepatology. 2013;57:601–609. doi: 10.1002/hep.26093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Abdallah Ismail N, Ragab SH, Abd Elbaky A, Shoeib AR, Alhosary Y, Fekry D. Frequency of Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes in gut microbiota in obese and normal weight Egyptian children and adults. Arch Med Sci. 2011;7:501–507. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2011.23418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Shin HS, Park SY, Lee do K, Kim SA, An HM, Kim JR, Kim MJ, Cha MG, Lee SW, Kim KJ, et al. Hypocholesterolemic effect of sonication-killed Bifidobacterium longum isolated from healthy adult Koreans in high cholesterol fed rats. Arch Pharm Res. 2010;33:1425–1431. doi: 10.1007/s12272-010-0917-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Chen J, Wang R, Li XF, Wang RL. Bifidobacterium adolescentis supplementation ameliorates visceral fat accumulation and insulin sensitivity in an experimental model of the metabolic syndrome. Br J Nutr. 2012;107:1429–1434. doi: 10.1017/S0007114511004491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wagnerberger S, Spruss A, Kanuri G, Stahl C, Schröder M, Vetter W, Bischoff SC, Bergheim I. Lactobacillus casei Shirota protects from fructose-induced liver steatosis: a mouse model. J Nutr Biochem. 2013;24:531–538. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2012.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mencarelli A, Cipriani S, Renga B, Bruno A, D’Amore C, Distrutti E, Fiorucci S. VSL#3 resets insulin signaling and protects against NASH and atherosclerosis in a model of genetic dyslipidemia and intestinal inflammation. PLoS One. 2012;7:e45425. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Esposito E, Iacono A, Bianco G, Autore G, Cuzzocrea S, Vajro P, Canani RB, Calignano A, Raso GM, Meli R. Probiotics reduce the inflammatory response induced by a high-fat diet in the liver of young rats. J Nutr. 2009;139:905–911. doi: 10.3945/jn.108.101808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Brun P, Castagliuolo I, Di Leo V, Buda A, Pinzani M, Palù G, Martines D. Increased intestinal permeability in obese mice: new evidence in the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;292:G518–G525. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00024.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Miele L, Valenza V, La Torre G, Montalto M, Cammarota G, Ricci R, Mascianà R, Forgione A, Gabrieli ML, Perotti G, et al. Increased intestinal permeability and tight junction alterations in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2009;49:1877–1887. doi: 10.1002/hep.22848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Putaala H, Salusjärvi T, Nordström M, Saarinen M, Ouwehand AC, Bech Hansen E, Rautonen N. Effect of four probiotic strains and Escherichia coli O157: H7 on tight junction integrity and cyclo-oxygenase expression. Res Microbiol. 2008;159:692–698. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ukena SN, Singh A, Dringenberg U, Engelhardt R, Seidler U, Hansen W, Bleich A, Bruder D, Franzke A, Rogler G, et al. Probiotic Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 inhibits leaky gut by enhancing mucosal integrity. PLoS One. 2007;2:e1308. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Anderson RC, Cookson AL, McNabb WC, Park Z, McCann MJ, Kelly WJ, Roy NC. Lactobacillus plantarum MB452 enhances the function of the intestinal barrier by increasing the expression levels of genes involved in tight junction formation. BMC Microbiol. 2010;10:316. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-10-316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Donato KA, Gareau MG, Wang YJ, Sherman PM. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG attenuates interferon-{gamma} and tumour necrosis factor-alpha-induced barrier dysfunction and pro-inflammatory signalling. Microbiology. 2010;156:3288–3297. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.040139-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Jeon SG, Kayama H, Ueda Y, Takahashi T, Asahara T, Tsuji H, Tsuji NM, Kiyono H, Ma JS, Kusu T, et al. Probiotic Bifidobacterium breve induces IL-10-producing Tr1 cells in the colon. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002714. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Hayashi A, Sato T, Kamada N, Mikami Y, Matsuoka K, Hisamatsu T, Hibi T, Roers A, Yagita H, Ohteki T, et al. A single strain of Clostridium butyricum induces intestinal IL-10-producing macrophages to suppress acute experimental colitis in mice. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;13:711–722. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ménard O, Gafa V, Kapel N, Rodriguez B, Butel MJ, Waligora-Dupriet AJ. Characterization of immunostimulatory CpG-rich sequences from different Bifidobacterium species. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:2846–2855. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01714-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Jounai K, Ikado K, Sugimura T, Ano Y, Braun J, Fujiwara D. Spherical lactic acid bacteria activate plasmacytoid dendritic cells immunomodulatory function via TLR9-dependent crosstalk with myeloid dendritic cells. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32588. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Samuel BS, Shaito A, Motoike T, Rey FE, Backhed F, Manchester JK, Hammer RE, Williams SC, Crowley J, Yanagisawa M, et al. Effects of the gut microbiota on host adiposity are modulated by the short-chain fatty-acid binding G protein-coupled receptor, Gpr41. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:16767–16772. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808567105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Nomura T, Iguchi A, Sakamoto N, Harris RA. Effects of octanoate and acetate upon hepatic glycolysis and lipogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1983;754:315–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kondo T, Kishi M, Fushimi T, Kaga T. Acetic acid upregulates the expression of genes for fatty acid oxidation enzymes in liver to suppress body fat accumulation. J Agric Food Chem. 2009;57:5982–5986. doi: 10.1021/jf900470c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Sakakibara S, Yamauchi T, Oshima Y, Tsukamoto Y, Kadowaki T. Acetic acid activates hepatic AMPK and reduces hyperglycemia in diabetic KK-A(y) mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;344:597–604. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.03.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Lin HV, Frassetto A, Kowalik EJ, Nawrocki AR, Lu MM, Kosinski JR, Hubert JA, Szeto D, Yao X, Forrest G, et al. Butyrate and propionate protect against diet-induced obesity and regulate gut hormones via free fatty acid receptor 3-independent mechanisms. PLoS One. 2012;7:e35240. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lyon I, Masri MS, Chaikoff IL. Fasting and hepatic lipogenesis from C14-acetate. J Biol Chem. 1952;196:25–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Venkatraman A, Ramakrishna BS, Pulimood AB. Butyrate hastens restoration of barrier function after thermal and detergent injury to rat distal colon in vitro. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1999;34:1087–1092. doi: 10.1080/003655299750024878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Larsen N, Vogensen FK, van den Berg FW, Nielsen DS, Andreasen AS, Pedersen BK, Al-Soud WA, Sørensen SJ, Hansen LH, Jakobsen M. Gut microbiota in human adults with type 2 diabetes differs from non-diabetic adults. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9085. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Qin J, Li Y, Cai Z, Li S, Zhu J, Zhang F, Liang S, Zhang W, Guan Y, Shen D, et al. A metagenome-wide association study of gut microbiota in type 2 diabetes. Nature. 2012;490:55–60. doi: 10.1038/nature11450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]