Abstract

The genomic density of sequence polymorphisms critically affects the sensitivity of inferences about ongoing sequence evolution, function, and demographic history. Most animal and plant genomes have relatively low densities of polymorphisms, but some species are hyperdiverse with neutral nucleotide heterozygosity exceeding 5%. Eukaryotes with extremely large populations, mimicking bacterial and viral populations, present novel opportunities for studying molecular evolution in sexually-reproducing taxa with complex development. In particular, hyperdiverse species can help answer controversial questions about the evolution of genome complexity, the limits of natural selection, modes of adaptation, and subtleties of the mutation process. However, such systems have some inherent complications and here we identify topics in need of theoretical developments. Close relatives of the model organisms Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila melanogaster provide known examples of hyperdiverse eukaryotes, encouraging functional dissection of resulting molecular evolutionary patterns. We recommend how best to exploit hyperdiverse populations for analysis, for example, in quantifying the impact of non-crossover recombination in genomes and for determining the identity and micro-evolutionary selective pressures on non-coding regulatory elements.

Introduction

A central aim in biology is to fully describe the processes that promote biodiversity, both in terms of taxonomic abundance and in terms of phenotypic and molecular variation within lineages. Explaining disparities among species in molecular diversity forms a long-standing problem in evolutionary genetics (Lewontin 1974; Leffler et al. 2012). As a result, population genetics and molecular evolutionary theory developed to explain such molecular diversity is now also a cornerstone in genome-wide trait association mapping, infection dynamics, molecular ecology and conservation genetics (Frankham 1995a; Milgroom et al. 1997; Knowles & Maddison 2002; Boyko et al. 2008; Ioannidis et al. 2009). However, the theoretical underpinnings of current applications of theory to empirical data often rely on assumptions that are violated in a growing number of systems (Desai & Plotkin 2008; Sella et al. 2009; Ninio 2010; Pritchard et al. 2010; Cutter et al. 2012). One such characteristic – hyperdiversity of molecular genetic variation within populations – traditionally has been regarded as relevant only to microbes and viruses. Yet, emerging data demonstrate that multicellular eukaryotic organisms also can harbor exceptional levels of molecular polymorphism, including close relatives to some of the classic model organisms Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila melanogaster.

Here, we consider the implications of hyperdiversity in eukaryotes for advancing our understanding of the evolutionary processes that govern the origin and maintenance of diversity within populations. Hyperdiverse eukaryotes can inform a broad range of issues in evolutionary genetics that are challenging or impossible to explore in traditional study systems. We show how investigating hyperdiverse taxa can help clarify such problems as the origins and evolution of genome complexity, modes of adaptive evolution, the identification of functional regulatory elements, mutational dynamics, and the dissection of the limits of natural selection. To do so, an explicit accounting of the complications relative to standard models of molecular evolution is key to successfully exploiting hyperdiverse organisms.

Hyperdiverse eukaryotes in nature

What is hyperdiversity?

We consider populations to be hyperdiverse if, at the level of nucleotide sequence, a random pair of alleles differ on average by 5% or more of sites in genomic regions that putatively evolve without constraint (θneu). This 5% rule-of-thumb is motivated by the practical relevance of finite- versus infinite-sites models of mutation above this level of nucleotide polymorphism (Desai & Plotkin 2008). Historically, eukaryotes have been thought not to harbor such extensive genetic variation, but, as we document below, this view is changing. While many species comprised of subdivided populations might achieve species-wide hyperdiversity, it is the diversity within populations that concerns us here. By focusing on within-population variation, we clearly distinguish polymorphism from divergence, and target the measure of diversity that is most appropriate for comparing among species (Charlesworth 2009). In what follows, we focus on the situation in which large population size and high θneu are coincident, so that, presumably, long-term and short-term estimates of effective population size (Ne; Box 1) will be concordant. For our purposes, it is sufficient that θneu is very large and that Ne also is very large. We are interested in how extremely large Ne in eukaryotes can manifest as molecular hyperdiversity, how the presence of hyperdiversity can compromise conventional thought and analyses of population genetic phenomena, and how to exploit hyperdiversity to gain a deeper understanding of the evolutionary process. Some implications of these issues also are pertinent to species with high θneu induced by a high mutation rate, despite modest Ne, whereas other implications will also be relevant to species with high short-term population size despite only modest θneu.

Box 1. Timescales of Ne.

A classic prediction of Kimura’s (1968) neutral theory of molecular evolution is that the amount of standing genetic variation at sites unaffected by selection will equal the product of 4 times the neutral mutation rate and the effective population size (i.e., at equilibrium θneu = 4Neμ) (Tajima 1983). Consequently, we might expect diversity in genomic regions presumed to be unconstrained to differ between species as a direct consequence of differences in mutation rate (μ) and/or effective population size (Ne). The effective population size is that central concept in population genetics introduced by Wright (1933) that describes the strength of genetic drift in populations (Charlesworth 2009).

Ongoing evolution in some species that have large present-day ‘short-term’ population sizes might not reflect the predictions derived from smaller ‘long-term’ population size estimates inferred from observed θneu (Karasov et al. 2010; Weissman & Barton 2012). Short-term effective population size, the most intuitive way of thinking about how Ne relates to genetic drift, is best inferred from direct measures of allele frequency change across recent generations for putatively neutral markers (variance effective size, Ne(V)) or by heterozygosity excess (Ne(H)). Singleton variants in very large population samples provide another means of estimating recent Ne from new mutational input (Keinan & Clark 2012). These measures indicate the current influence of genetic drift.

By contrast, segregating genetic variation essentially reflects the harmonic mean size over the population’s entire coalescent history (Ne(θ)) and is therefore very sensitive to any bottlenecks that may have occurred over this long span of time (Kimura & Crow 1963; Drummond et al. 2002; Wang 2005). This can potentially create appearance of a disconnect between a small coalescent effective size estimated from genetic diversity despite the small role of drift in a large present-day population. For some purposes, however, even Ne(θ) may not be long-term enough – for example, in deducing selection efficacy in the interval between the coalescent of population variation and the more ancient most recent common ancestor with other species. It is possible, however, to infer ancestral population sizes from the distribution of sequence divergence and gene-tree species-tree discordance (Rannala & Yang 2003; Zhou et al. 2007). Linkage disequilibrium-based estimators of Ne should provide a view of Ne intermediate between the long-term view afforded by Ne(θ) and very recent estimates of genetic drift from Ne(V). Contrasting Ne(θ) values derived from molecular markers that mutate at different rates (e.g. SNPs vs. STRPs) might provide a supplementary way to assess Ne on different timescales (Payseur & Cutter 2006; Haasl & Payseur 2011). When census sizes (N) of a species can be very large and the species is subject to repeated, drastic bottlenecks or selective sweeps, then θneu implying a relatively small long-term Ne may fail to reflect the limited relevance of genetic drift to ongoing adaptation (Barton 2010; Karasov et al. 2010; Weissman & Barton 2012).

How common is molecular hyperdiversity among eukaryotes?

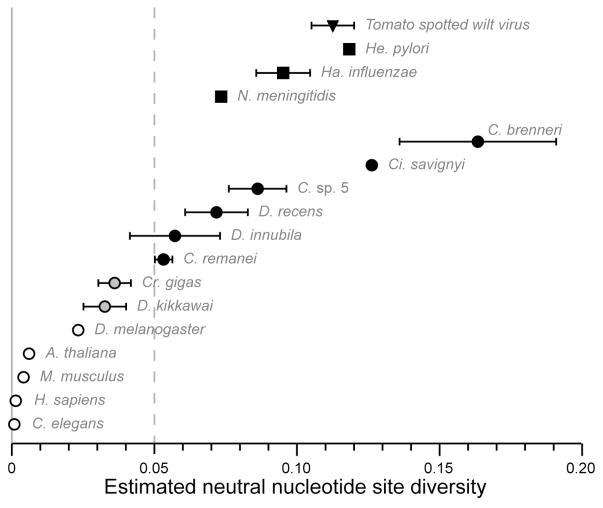

Lynch (2006) and Leffler et al. (2012) surveyed a broad array of taxa for quantitative measures of nucleotide polymorphism, but the data are sparse for most of the species nominally conforming to the notion of hyperdiversity (θneu > 5%). We consider cases with meager population genetic data as preliminary (very few loci or individuals assessed), warranting further detailed confirmation. Several species, however, are convincing and merit enumeration (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Examples of hyperdiverse eukaryotes and other organisms.

Estimates of neutral nucleotide diversity greater than 5% are shown for a single population of eukaryotic species (black circles), with two species that approach this definition of hyperdiversity (light grey circles). Estimates of nucleotide diversity for model organisms (white circles) and a few examples of hyperdiverse viruses (black triangle) and bacteria (black squares) are also indicated for comparison. A Jukes-Cantor correction for multiple hits was applied to diversity values (black circles and Ha. influenzae only) and a correction for codon bias was applied to Caenorhabditis other than C. elegans and to Ciona. Values for D. recens and D. innubila derive from Watterson’s θ estimator, whereas other values use average pairwise diversity (π). Data for Caenorhabditis and Drosophila include both autosomal and X-linked loci, with X-linked values unadjusted for any population sex ratio effects that would increase the values even further. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean across loci (values smaller than the symbol size not shown). References: A. thaliana (Nordborg et al. 2005); C. brenneri (Dey et al. 2013); C. elegans (Andersen et al. 2012); C. remanei (Jovelin et al. 2003; Cutter et al. 2006a; Jovelin 2009; Jovelin et al. 2009; Dey et al. 2012); C. sp 5 (Cutter et al. 2012); Ci. savignyi (Small et al. 2007); Cr. gigas (Sauvage et al. 2007); D. innubila (Dyer & Jaenike 2004); D. kikkawai (Goto et al. 2004); D. melanogaster (Langley et al. 2012); D. recens (Dyer et al. 2007); Ha. influenzae (Maughan & Redfield 2009); He. pylori (Hughes et al. 2008); H. sapiens (Perry et al. 2012); M. musculus (Perry et al. 2012); N. meningitidis (Hughes et al. 2008); TSWV (Tsompana et al. 2005).

First, the ascidian sea squirt Ciona savignyi exhibits polymorphism averaging 8% at 4-fold degenerate codon sites (Small et al. 2007) (we calculate θneu = 0.126 after correcting for multiple hits and codon bias; Figures 1, 2), and the related species Ci. intestinalis also appears to have very high diversity (Dehal et al. 2002; Nydam & Harrison 2010; Tsagkogeorga et al. 2012). These hermaphroditic marine chordates reproduce via broadcast spawning in shallow water and often achieve high densities (Jiang & Smith 2005; Therriault & Herborg 2008). Second, several species in the quinaria group of fungus-feeding Drosophila provide strong candidates for molecular hyperdiversity (Dyer & Jaenike 2004; Shoemaker et al. 2004; Dyer et al. 2007). Although only 5–6 nuclear loci were surveyed in each species, average silent-site diversity (θsi) is ~5% in both D. innubila and D. recens. Some species of Drosophila appear near the cusp of hyperdiversity (Leffler et al. 2012), so tests for diversity-reducing effects of selection on synonymous sites should be considered carefully to determine θneu, as we will describe later. Third, polymorphism averages an astonishing 14% at synonymous sites (θneu = 0.16) in the nematode Caenorhabditis brenneri (Barriere et al. 2009; Jovelin 2009; Dey et al. 2013). At least two other species in this genus (C. remanei, C. sp. 5) also have very high diversity (Figure 1) (reviewed in Cutter et al. 2009; Jovelin 2009; Wang et al. 2010b). Rapid decay of linkage disequilibrium, gene genealogies, morphological criteria and experimental genetic crosses all support species cohesion within these groups. These ~1 mm long animals related to the classic animal model C. elegans are obligately outbreeding, capable of extremely rapid development, and are thought to be able to disperse long distances during the stress-resistant ‘dauer’ phase of the life cycle (Kiontke et al. 2011; Lee et al. 2012). The nematode relatives of C. elegans and fly relatives of D. melanogaster provide particularly promising groups to study hyperdiversity, owing to the potential of porting model organism tools to these other species. Ciona also has a growing toolbox of experimental approaches (Lemaire 2011; Stolfi & Christiaen 2012).

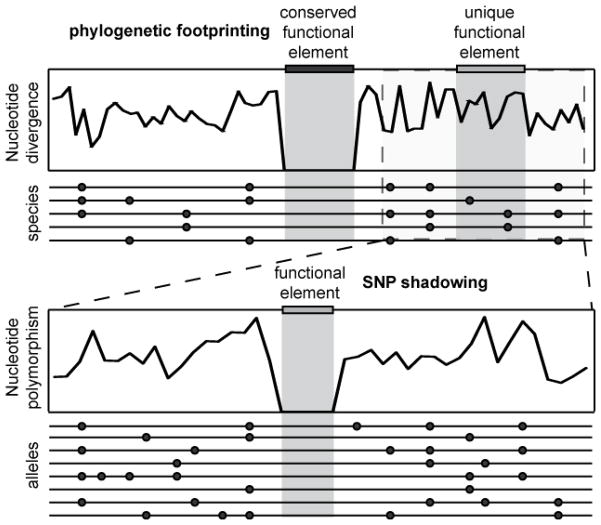

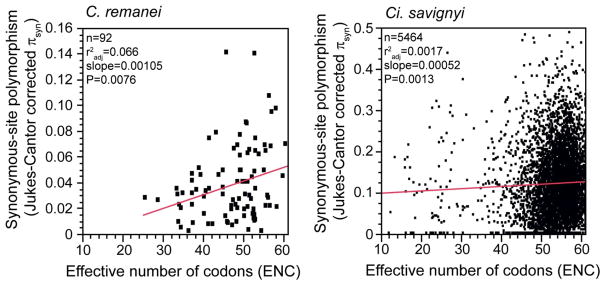

Figure 2. Loci with stronger selection on synonymous sites for codon usage bias exhibit lower polymorphism.

Data for C. remanei re-calculated from (Jovelin et al. 2003; Cutter et al. 2006a; Cutter 2008b; Jovelin 2009; Jovelin et al. 2009), plus 14 unpublished loci, using DnaSP and codonW with a manual Jukes-Cantor correction (Librado & Rozas 2009). Data for Ci. savignyi re-calculated from (Small et al. 2007), using Polymorphorama (Bachtrog & Andolfatto 2006) and codonW (14 loci with πsyn > 0.5 excluded). Genes with stronger codon bias have two-fold more strongly depressed synonymous-site diversity in C. remanei than in Ci. savignyi (see Box 4). For Ci. savignyi, the estimate for θneu = 0.126 lies at the point on the regression line for an effective number of codons (ENC) value of 61, which corresponds to uniform codon usage.

We mention two final examples with extreme overall diversity, but that do not conform to our notion of within-population hyperdiversity. Although the monkey-flower Mimulus guttatus retains enormous polymorphism for two loci that have been examined in detail (θsi ~ 7.7%), it has substantial population sub-structuring and allelic introgression from close relatives that contributes to much of the molecular diversity in this species complex (Sweigart & Willis 2003). These factors thus complicate inference of within-population effective size and hyperdiversity (Box 2). The free-living, non-parasitic protist Paramecium aurelia complex similarly does not have an easily-interpretable evolutionary history for its high overall levels of polymorphism (Catania et al. 2009).

Box 2. Ecological determinants of hyperdiversity.

What factors contribute to a species being hyperdiverse? Organisms that capitalize on dense or widespread resources should themselves have high population abundances, with correspondingly greater Ne and genetic variation (Stevens et al. 2007). It is physically small organisms that can more plausibly achieve and maintain exceptionally large populations (Peters & Wassenberg 1983; Marquet et al. 2005). Moreover, small-bodied organisms tend to have more rapid turnover of generations (Blueweiss et al. 1978), and species with short generation times have larger population sizes (Chao & Carr 1993). Very small organisms (<1mm) also are thought to have enormous inherent dispersal propensity and large geographic ranges (Finlay 2002), reinforcing the importance of small body size in hyperdiversity. This is encouraging, from the practical standpoint of studying hyperdiverse taxa in detail, because small organisms tend to make more tractable systems of laboratory interrogation.

Countervailing factors, however, may depress polymorphism in species that otherwise seem good candidates for high diversity. Subpopulations with restricted genetic exchange by migration can promote high species-wide diversity, but may largely reflect divergence between them and not particularly high intra-population variation (Nordborg et al. 2005; Ross-Ibarra et al. 2008). Turnover of subpopulations via extinction and recolonization generally reduces Ne and population variation (Pannell & Charlesworth 1999). Unidirectional dispersal with source-sink dynamics, even in an unstructured species distribution, will diminish the expected amount of diversity that can be maintained, as may occur in some marine organisms with larval stages dispersed by ocean currents (Wares & Pringle 2008; Casteleyn et al. 2010). Temporal fluctuations in population size or high variance in reproductive success also will constrain genetic variation below what might be expected from census size (Hedgecock 1994; Hedrick 2005). Similarly, biparental inbreeding in long-lived organisms, biased sex ratios, and self-fertilization all will act to restrict the maintenance of polymorphism. The confluence of many of these factors, compounded by a bias toward study of species with body sizes >1mm, may contribute to only a recent recognition of hyperdiversity among eukaryotes.

A greater variance in reproductive output among individuals in species that have large census sizes, or more drastically fluctuating populations, could explain a general tendency for highly abundant organisms to have smaller Ne/N ratios (Frankham 1995b; Pray et al. 1996; Hedrick 2005). Although high fecundity per se need not result in high fecundity variance (Nunney 1996), ‘sweepstakes’ effects and sexual selection that diminish the number of successfully breeding adults may be important in a variety of taxa, from plants to both terrestrial and aquatic invertebrates (Frankham 1995b; Pray et al. 1996; Boudry et al. 2002; Hedrick 2005); high reproductive skew changes expectations about how genetic drift works in relation to population size (Eldon & Wakeley 2006; Der et al. 2012). Genetic draft will further exacerbate small Ne/N ratios for abundant species (Gillespie 2001). For species with very low Ne/N ratios, Ne estimates may provide a poor predictor of the input of beneficial mutations available for screening by natural selection (e.g. Karasov et al. 2010).

Discovering hyperdiverse species

As the sampling of new species grows with the increasing pace of molecular approaches in ecology (Box 2), it is essential that efforts akin to DNA barcoding mature to include multiple nuclear loci, as in multi-locus sequence typing (MLST) used commonly in bacteria (Maiden et al. 1998; Perez-Losada et al. 2006), so as to appropriately interrogate the evolutionary history of organisms (Chenuil et al. 2010). With hyperdiverse lineages, standard thresholds of divergence – particularly for mitochondrial loci – are unlikely to be useful yardsticks of species membership (Vences et al. 2005; Hajibabaei et al. 2006). Sampling of multiple nuclear loci permits inference of recombination in the recent history of putative con-specifics (via the decline of linkage disequilibrium) and the uniformity of genealogical patterns across loci, which are much more powerful metrics of shared ancestry in a comparative population genetic framework (Edwards 2009; Fujita et al. 2012). The use of multi-locus, nuclear DNA barcode or tag-sequencing integrated with high-throughput next-generation sequencing platforms has the potential to provide an unprecedented view of population variation in poorly-characterized systems, in addition to capturing raw biodiversity at the level of species delimitation (Hudson 2008; Hohenlohe et al. 2010). We anticipate that the accelerated application of molecular ecological approaches, including metagenomics and multi-locus DNA barcoding, will drastically increase the number of hyperdiverse organisms known to science in the coming years.

Re-focusing models of mutation and mutational implications

Infinite-site vs. finite-site models

A straight-forward implication of nucleotide hyperdiversity is that a non-negligible fraction of sites will have experienced more than one mutation since the coalescent time of a population sample. This violates the key assumption of the ubiquitous infinite-sites mutation model (Kimura 1969; Tajima 1996). For example, ~10% of segregating sites observed in C. brenneri have three or even four nucleotide variants (i.e. tri-allelic or tetra-allelic single nucleotide polymorphisms, SNPs)(Dey et al. 2013). Thus, it becomes critical to incorporate the effects of multiple hits via finite-sites models of molecular evolution into population genetic analyses (Ninio 2010). Finite-sites models have been developed to analyze linkage disequilibrium, variant frequency spectra and estimators of θ (Fearnhead & Donnelly 2001; McVean et al. 2002; Desai & Plotkin 2008; Jenkins & Song 2011), which is preferable to simply applying a post-hoc Jukes-Cantor multiple hits correction. However, accessible software to estimate population genetic parameters in a finite-sites framework has not yet been deployed for all such metrics. Incorporation of finite-sites models into analyses of selection for hyperdiverse taxa is particularly important to arrive at appropriate interpretations about selection and demographic history (Desai & Plotkin 2008). Even in the absence of hyperdiversity, infinite-sites mutational models may handicap tests for adaptation; a ‘fitness flux’ perspective based on a finite-sites notion of evolution is potentially well-suited to both hyperdiverse species and taxa with typical levels of polymorphism (Mustonen & Lassig 2009).

Complex mutation

The exceptional density of heterozygosity in hyperdiverse genomes also will help to understand complex mutational patterns. The view that mutations can induce other mutations has emerged from observations that single nucleotide mutation rates are higher in the vicinity of insertion and deletions (indels) (Hardison et al. 2003; Longman-Jacobsen et al. 2003; Wetterbom et al. 2006; Tian et al. 2008; Zhu et al. 2009; De & Babu 2010; Hollister et al. 2010; McDonald et al. 2011; Jovelin & Cutter 2012), by the clustering of SNPs (Amos 2010; Schrider et al. 2011a) and from the higher-than-expected occurrence of tri-allelic variants (Hodgkinson & Eyre-Walker 2010). High heterozygosity will amplify these complex mutational patterns, with potentially major consequences for genome evolution by exacerbating heterogeneity in the distribution of nucleotide variation along chromosomes. Analyses of hyperdiverse species, with their high density of indels and tri-allelic SNPs, should thus help elucidate how the mutational process works and its attendant micro-evolutionary consequences.

Compensatory mutation

Deleterious mutations can impose a serious burden on finite populations. And yet, compensatory evolution can permit populations to recover fitness relatively quickly, given sufficiently large populations (Estes & Lynch 2003; Estes et al. 2004), and at equilibrium even a low rate of beneficial mutation can offset the effect of detrimental mutations to maintain high population mean fitness (Goyal et al. 2012). Fitness recovery can derive from new beneficial compensatory alleles (Denver et al. 2010) or from compensatory epistatic interactions between individually deleterious mutations (Kimura 1985). However, evolutionary responses for such epistatically-interacting sites is less sensitive to Ne than are independently-evolving sites (Piskol & Stephan 2011). A large population size also may increase the number of mutations at any locus, and standing variation can be very high, such that the raw material for compensatory and adaptive evolution may often not be limited by mutational input in hyperdiverse organisms (Hermisson & Pennings 2005; Ralph & Coop 2010). Should high μ cause a species’ hyperdiversity, then compensatory evolution will be more rapid (Piskol & Stephan 2011).

Co-evolution between pairs of interacting amino acid residues is a good predictor of protein structure and has successfully predicted protein folds de novo (Marks et al. 2011; Hopf et al. 2012). This method stems from the principle that conservation of protein structure is essential to maintain proper function, and that this imposes selection for conservation of physical interactions between amino acid residues. Thus, efficient selection in hyperdiverse species with large populations could strengthen such patterns of intragenic co-evolution through compensatory mutation between interacting sites. Analysis of protein sequence evolution in Drosophila lends support for this view. Non-synonymous substitutions cluster together along the protein backbone, preferentially within the same lineage, at least in part because of epistatic interactions between substitutions (Callahan et al. 2011). And, the most conserved genes, which experience the most effective selection, have greatest clustering of substitutions (Callahan et al. 2011).

Hyperdiverse species are particularly well suited for studying how compensatory mutation can mediate divergence under stabilizing selection, such as for RNA gene evolution (Piskol & Stephan 2011), transcription factor/target site coevolution (Baker et al. 2011) and developmental system drift (DSD) (True & Haag 2001). DSD involves the dissociation between homology at the phenotypic and molecular levels (Dickinson 1995; Abouheif et al. 1997; Wray & Abouheif 1998), and it may be common in developmental networks (True & Haag 2001; Abouheif & Wray 2002; Kiontke et al. 2007). When directional and stabilizing selection act on different traits that have an overlapping genetic basis (Johnson & Porter 2007), mutations at a locus for the trait that experiences stabilizing selection can compensate for divergence at a pleiotropic locus. The result is trait conservation at the phenotypic level despite divergence among species in its genetic underpinnings: ‘systems drift’ (Johnson & Porter 2007). Because all forms of natural selection are expected to be more efficient in species with large Ne, DSD might be particularly widespread among taxa that include hyperdiverse members and could therefore complicate inferences about the genetic basis of parallel and convergent evolution.

Ancestral state inference and ancestral polymorphism

Hyperdiversity complicates the inference of ancestral states for individual nucleotide sites. This is so because the deep genealogical history of a given locus increases the potential for multiple mutations to have occurred; this is most acute at sites that are observed presently to have 3 or 4 segregating variants. Unfortunately, this can create problems because the evolutionary polarization of mutational changes, to infer ancestral and derived states, is central to a variety of analytical methods (Kreitman 2000; Nielsen 2005). Typically, a single copy of an outgroup reference sequence is used, or sometimes a single copy from each of several outgroups, for comparison with the multiple sequences from the focal species’ population. But this approach neglects polymorphism within the outgroup taxa, which will underestimate the uncertainty in ancestral states, and potentially prove egregious, particularly if both focal and outgroup species are hyperdiverse. Coupled with the deep genealogical history of a locus, lineages corresponding to the closest outgroup species may share considerable ancestral polymorphism or, in the case of reciprocal monophyly, be very distantly related (Pamilo & Nei 1988; Clark 1997; Arbogast et al. 2002). Either of these scenarios will introduce marked uncertainty into the inference of ancestral states, owing to ancestral polymorphism or multiple mutational hits, respectively (Baudry & Depaulis 2003; Hernandez et al. 2007). Amino-acid changing sites will be less of a problem for inferring ancestral states than will synonymous or non-coding sites, partly due to purifying selection plausibly favoring the encoding of the same amino acid in multiple species and partly due to the empirical rarity of more than two variants at replacement-sites. Consequently, it will be critical to appropriately model the mutational process (and demography) of hyperdiverse lineages to capture the complexities of determining ancestral-derived variant relationships (Charlesworth et al. 2005; Hernandez et al. 2007), or instead to rely more heavily on finite-sites versions of ‘folded frequency spectrum’ approaches for population genetic analysis (Kreitman 2000; Nielsen 2005; Zeng 2010).

Whole-genome assembly, alignment, and conflation of alleles with gene duplicates

As population genomics takes its foothold as a standard means of quantifying population genetic variation, hyperdiverse organisms are particularly formidable for making biological sense of the data abundance (Vinson et al. 2005). For de novo genome assembly, heterozygosity within a sample makes the computational process of creating contigs from short reads a serious challenge (Donmez & Brudno 2011; Huang et al. 2012). Given high heterozygosity, allelic variation can easily be confused as paralogous duplicate copies of a genomic segment. For example, despite 20 generations of laboratory sib-mating, 10–30% of the reference genomes of several species of Caenorhabditis retained residual heterozygosity that initially inflated genome assembly sizes and estimates of the number of genes (Barriere et al. 2009). Even given a reference genome, high population polymorphism will make any given individual’s genome very different from the reference. Many read-mapping algorithms can tolerate few ‘mismatches’ between the sample and reference, which can compromise analyses from the very start: for θneu = 0.05, the 95% binomial expected range of mismatches is 2 to 8 for a random 100bp sequence read. For example, only ~30% of sequence reads from a population genomics survey for Ciona intestinalis were aligned to a reference cDNA collection, although the coverage was not high and the reference sequence is from a distinct subspecies (Tsagkogeorga et al. 2012). Fortunately, sequence coverage information, incorporation of long-read technologies, independent estimates of genome size (from e.g. flow cytometry), and more sophisticated haplotype-aware assemblers can help identify and alleviate these problems (Vinson et al. 2005; Kim et al. 2007; Barriere et al. 2009; Donmez & Brudno 2011; Lunter & Goodson 2011; Huang et al. 2012). In sequencing a heterozygous diploid genome, it is key to have sufficient coverage to sample both alleles at a locus to be able to confidently distinguish the alternative haplotypes (Zharkikh et al. 2008). Whole-genome sequencing of a haploid genome also provides a viable option in some taxa to circumvent heterozygosity within a sample (Langley et al. 2011).

Rate of adaptation

A primary aim of molecular population genetics is to infer and quantify adaptation in DNA sequences. Functional genetic variation is, of course, the raw material for adaptive evolution, and yet we have defined hyperdiversity in terms of neutral variation – what should we expect for how adaptive evolution leaves its imprint in the genomes of hyperdiverse species? The answers to this question intertwine intimately with the prevalence of different modes of adaptation: what is the relative incidence of ‘hard sweeps,’ ‘soft sweeps,’ and partial sweeps involving polygenic selection on traits (Pritchard et al. 2010)? Our expectations also depend on whether we conceive of adaptation as any form of positive selection, including compensatory evolution and genomic conflict, or in the more restrictive sense as a response to extrinsic ecological and/or environmental changes (Mustonen & Lassig 2009).

Hard, soft and partial selective sweeps

Hard sweeps epitomize the standard population genetic notion of adaptation: a new beneficial mutation arises and increases in frequency to fixation, in the process dragging along with it by genetic hitchhiking any linked variants (Maynard Smith & Haigh 1974). By contrast, soft sweeps involve the selective fixation of alleles that pre-existed in the population as segregating genetic variation, or the simultaneous selection on alternative alleles with equivalent fitness effects until their joint frequency reaches 1 (Hermisson & Pennings 2005). This broad soft sweep definition includes substitutions of beneficial alleles that are identical by descent, but that have recombined onto different genetic backgrounds, as well as substitutions by multiple copies of equivalent beneficial alleles that were created by independent mutations (‘parallel adaptation’; Ralph & Coop 2010). The segregating alleles typically are presumed to originally occur at mutation-drift or mutation-selection balance (Hermisson & Pennings 2005). For polygenic selection on standing variation, adaptation might not yield fixation of particular alleles at any locus at all or any obvious molecular signals of positive selection, despite a robust phenotypic evolutionary response to even very strong selection on the phenotype (Latta 1998; Le Corre & Kremer 2003; Kelly 2006; Chevin & Hospital 2008). This will yield incomplete ‘partial’ selective sweeps at the trait loci that simply reflects shifts in allele-frequency (Chevin & Hospital 2008; Pritchard et al. 2010). By considering only hyperdiverse species with both large Ne and high θneu, we can restrict the relevant portion of parameter space to evaluate the merits and implications of these alternative modes of adaptation.

When selection is strong and the population mutation rate is low, then a selectively favored allele most likely has a single mutational origin (Hermisson & Pennings 2005). Hyperdiverse organisms, however, are unlikely to conform neatly to this scenario – regardless of whether the hyperdiversity results from large Ne or high mutation rate. This implies that adaptation in such species often will not be mutation-limited and that selection via soft sweeps involving multiple allelic origins might be particularly important, especially for loci subject to weak selection (Hermisson & Pennings 2005; Ralph & Coop 2010). In the event of a soft sweep originating from segregating variation, species with large populations, in particular, will often not register much of a classic signature of deviation from neutrality around the selective target – in terms of polymorphism, linkage disequilibrium, or the variant frequency spectrum – even for a selectively favored allele with a single mutational origin (Innan & Kim 2004; Hermisson & Pennings 2005; Przeworski et al. 2005; Olson-Manning et al. 2012). This is because the coalescent depth of the beneficial allele typically is much greater than when selection favors a new allele, with recombination having diminished correspondingly more linkage disequilibrium between the beneficial allele and nearby neutral variants. Consequently, genomic scans for selection that presume signatures of ‘hard’ selective sweeps might generally be impotent to detect much of the positive selection operating in hyperdiverse organisms (Pritchard et al. 2010; Storz & Wheat 2010). Methods are being developed that focus on soft sweep detection (Pritchard et al. 2010; Sattath et al. 2011); if hyperdiverse organisms provide greater power than low-diversity species to identify soft sweeps by virtue of the greater density of polymorphic sites, then they may nevertheless prove valuable in testing theory related to dominance, epistasis and the distribution of selective effects (Orr & Betancourt 2001; Orr 2003; Kassen & Bataillon 2006; Teshima & Przeworski 2006; Silander et al. 2007; Otto & Whitlock 2009; Takahasi 2009; Orr 2010).

Should hard sweeps be relatively uncommon relative to soft sweeps in the adaptive process of hyperdiverse populations, then this holds important implications for genome-wide patterns of polymorphism in such taxa. Hard sweeps provide the conceptual basis to standard recurrent genetic hitchhiking models that predict reduced polymorphism levels in regions of the genome subject to infrequent crossover recombination (Wiehe & Stephan 1993; Stephan 2010). Hard sweeps also frame Gillespie’s models of genetic draft (Gillespie 2000a, b, 2001), suggesting that the consequences of draft will not be as extreme as predicted if soft sweeps dominate, because soft sweeps do not depress linked variation as greatly (Innan & Kim 2004; Hermisson & Pennings 2005; Przeworski et al. 2005) (Box 3). When many beneficial mutations across the genome are present simultaneously, then interference can limit their density and make recombination the limiting factor in combining beneficial genetic backgrounds in adaptation (Weissman & Barton 2012). Further theory is needed to better understand the consequences of recurrent soft sweeps on genome-wide patterns of polymorphism in contrast to hard sweeps.

Box 3. Drift, Draft and Ne.

On the one hand, Ne and genetic drift are often argued to play a dominant role in effecting evolutionary change (Lynch & Conery 2003b; Lynch 2007); on the other hand, some propose that differences among species in Ne are largely irrelevant to evolution (Gillespie 2001). In the latter view, the hitchhiking effects of recurrent selective sweeps are predicted to counteract the build-up of neutral polymorphism in species with large population size by ‘genetic draft,’ through the influence of genetic linkage (Maynard Smith & Haigh 1974; Gillespie 2000a, b; Neher & Shraiman 2011; Frankham 2012). The limitation of a species’ polymorphism by the draft effect will be most pronounced when selection pressures fluctuate dramatically (Barton 2000) and could lead to asymptotic θneu with increasing population size, approaching a value of 2μ/a (for complete linkage, where a is the rate of substitution via ‘hard sweeps’ fixing new beneficial mutations) (Gillespie 2000a, b, 2001). Thus, the draft model predicts that species with populations of a size exceeding a modest threshold will not differ appreciably in diversity. Consequently, fewer species will achieve hyperdiversity under the draft model than might be expected from the traditional expectation of a linear association between Ne and θneu. Note that development of the draft model was motivated by the observation that measures of molecular diversity do not seem to scale linearly with population size: measures of population size across species appear to range over more orders of magnitude than do estimates of θneu (Lewontin 1974; Maynard Smith & Haigh 1974; Gillespie 2000a; Lynch 2007; Leffler et al. 2012). Selection on cell-biological processes also might act to limit hyperdiversity, owing to base-pairing requirements of recombination and DNA repair (Stephan & Langley 1992; Harfe & Jinks-Robertson 2000). To some extent, the limiting effect of genetic draft on a species’ polymorphism must occur, but, as discussed in the main text, the increasing relative importance in adaptation of ‘soft sweeps’ over ‘hard sweeps’ for species with larger Ne may alleviate the extremity of its influence. Theory that can quantify the genome-wide influence of recurrent soft sweeps in adaptation will prove valuable in connecting population size and diversity to selection and linkage.

Even if soft sweeps are a common mode of adaptation in hyperdiverse taxa, surely some fraction of the episodes of positive selection will involve hard sweeps, and we may ask how hyperdiversity will affect the detection and localization of them in genomes. Indeed, recurrent hard sweep models applied to Drosophila simulans, a species that approaches our definition of being hyperdiverse, yields inference of frequent substitutions driven by positive selection (Begun et al. 2007; Macpherson et al. 2007; Andolfatto et al. 2011). When applied to hyperdiverse populations, their greater background levels of diversity and density of SNPs should provide more statistical power to detect shifts in polymorphism, linkage disequilibrium and the site frequency spectrum. In part, scanning genomes for hard sweeps is a practical stance, as most methods for detecting the imprint of selection presume this mode of adaptation within a local population or across the species range – and the corresponding signature of selection will be easier to identify (Storz 2005; Pavlidis et al. 2008; Siol et al. 2010). While we must recognize that the loci pinpointed by such analysis may represent a biased subset of substitutions with respect to the genetic architecture of adaptation, nevertheless they still may identify novel adaptive phenotypes (Storz & Wheat 2010).

Notions of adaptive molecular evolution

Mustonen and Lassig (2007, 2009, 2010) formalized the notion of adaptation as a non-equilibrium stationary population state with a surfeit of beneficial relative to deleterious substitutions. A population experiences such a positive ‘fitness flux’ as a byproduct of fluctuations in selection (presumably resulting from environmental or ecological fluctuations) with a timescale on the order of the reciprocal of the mutation rate. This contrasts with a static fitness landscape in which positive selection might also fix beneficial mutations, but this generally would reflect the balance between deleterious and compensatory beneficial mutations; it also differs from a frenetically changing fitness landscape, in which substitutions tend toward quasi-neutrality (Mustonen & Lassig 2009). Consequently, the time-dependent fitness flux concept of adaptation is more restrictive than simple fixation by positive selection, and perhaps better reflects ecologically-motivated notions of adaptive evolution (Mustonen & Lassig 2007; Mustonen et al. 2008; Mustonen & Lassig 2009, 2010). Because their approach explicitly implements finite-sites models of evolution, it may be particularly valuable for analysis of hyperdiverse organisms.

For recurring protein adaptation, as might be expected for organisms with positive fitness flux, tests of positive selection using variants of the McDonald-Kreitman test (MK test; McDonald & Kreitman 1991) may prove especially valuable for hyperdiverse species. Indeed, MK tests detect positive fitness flux (Mustonen & Lassig 2007). Special care must be taken with synonymous sites in MK tests to appropriately incorporate finite-sites mutational models, ancestral state inference, and translational selection (McDonald & Kreitman 1991; Eyre-Walker 2002; Charlesworth et al. 2005; Desai & Plotkin 2008; Eyre-Walker & Keightley 2009; Mustonen & Lassig 2009). Interestingly, the fitness flux model of adaptation predicts that long-term fluctuating population sizes will yield a signal of positive fitness flux across the genome: net adaptive evolution (Mustonen & Lassig 2010). Perhaps lineages that are undergoing speciation, or that only recently became reproductively isolated (e.g. within Drosophila), might also tend to be in a state of positive fitness flux – which could account for positive associations between rates of speciation and molecular divergence (Webster et al. 2003; Pagel et al. 2006; Venditti & Pagel 2010).

Fisher (1958) argued that the rate of adaptive evolution will be most efficient and rapid in large populations (e.g. scaling linearly or logarithmically with Ne (Neher et al. 2010; Weissman & Barton 2012)). Ohta (1972) subsequently predicted an inverse relationship between population size and the rate of adaptive substitution, based on the logic that large populations have bigger ranges that span more heterogeneous environmental conditions that, in turn, will retard the origin and fixation of globally advantageous mutations. And then, Gillespie (2001) predicted that the rate of adaptive evolution will be essentially uncorrelated with population size, owing to the interaction between selection and genetic linkage resulting in genetic draft (see also Neher & Shraiman 2011; Weissman & Barton 2012). Both inter-specific and intra-genomic studies are consistent with higher Ne being associated with positive selection causing faster substitution rates (α, the fraction of amino-acid-changing mutations that are fixed by positive selection, or ωa, the rate of positively selected substitution), in-line with Fisher’s prediction (Presgraves 2005; Petit & Barbadilla 2009; Gossmann et al. 2010; Halligan et al. 2010; Siol et al. 2010; Andolfatto et al. 2011; Strasburg et al. 2011; Gossmann et al. 2012). However, it is unresolved empirically whether α might saturate with Ne, as would be predicted by Gillespie. Adding estimates of α for hyperdiverse eukaryotes would help distinguish these alternatives. A rough and simplistic estimate of α for the hyperdiverse C. sp. 5 (i.e., (Smith & Eyre-Walker 2002)), gives α ≅ 74%, suggesting that increasing Ne might continue to yield increasing α estimates in eukaryotes. Mustonen and Lassig’s (2009) view of adaptation, for example, suggests that small populations may more likely fall in a range of positive fitness flux (i.e. κ ≫ κ*, the rate of environmental change being less than the average lifetime of polymorphisms), consistent with Ohta’s prediction. By estimating rates of adaptive evolution in eukaryote taxa that span an extreme of population sizes, including hyperdiverse species, we may be able to more confidently evaluate these alternative predictions.

Balancing selection and the maintenance of hyperdiversity

Balancing selection can be a powerful force to maintain genetic variability, whether through heterozygote advantage, frequency dependence, or some types of spatial or temporal fluctuations in selection pressures (Charlesworth 2006; Mitchell-Olds et al. 2007). However, linkage of functionally important polymorphisms to nearby neutral variants will constantly be eroded by recombination, provided the alleles are not contained within inversions. As a result, over the long term, balancing selection leaves only a narrow footprint on the genome (Charlesworth 2006). Even in humans, with its long haplotype blocks, the narrow window of elevated linked variation around loci subject to long-term balancing selection makes it difficult to find examples of such selection in the genome (Bubb et al. 2006; Andres et al. 2009), and other factors like population admixture, pooled sampling of subpopulations, and violation of the infinite sites mutation model can all generate skews in the site frequency spectrum in the same direction as will long-term balancing selection (Cutter et al. 2012). Input of duplication mutations, which would occur regularly in species with very large populations given estimated duplication rates (Lipinski et al. 2011), can provide a means of generating ‘fixed heterozygosity’ of beneficial allele combinations that does not require balancing selection (Mitchell-Olds et al. 2007). Also, recent work proposes that new beneficial mutations might commonly be subjected to short-term heterozygote advantage, which could leave genomic signatures of partial hard selective sweeps (Sellis et al. 2011). However, theory on frequent partial sweeps, which might also approximate the fate of loci subject to frequency dependent selection with allele turnover, generally acts to reduce the amount of linked neutral polymorphism, albeit to a much lesser degree than do recurrent hard selective sweeps favoring a single positively selected allele (Coop & Ralph 2012). Consequently, even if widespread, balancing selection seems unlikely to provide a plausible explanation for genome-wide persistence of neutral hyperdiversity.

Constraint and the limits of natural selection

Purifying selection against detrimental alleles should be more efficacious in larger populations (Wright & Andolfatto 2008; Ellegren 2009). This greater efficacy of selection with increasing Ne is most important for weakly-selected sites, however, because the probability of extinction of strongly deleterious mutations is essentially independent of Ne. Stated another way, species with larger Ne will have a smaller fraction of neutrally-evolving sites, following from the nearly-neutral amendment to the neutral theory of molecular evolution (Ohta 1973). This effect should be evident in nucleotide sequences for hyperdiverse populations in several well-defined ways.

Constraint on protein sequence

If hyperdiversity is caused by large Ne rather than high mutation rates, then we expect polymorphism at non-synonymous sites to be disproportionately small (i.e. low θA/θneu): even mildly deleterious changes to the amino acids encoded in genes will be eliminated by purifying selection (low θA), and most mutations with fitness effects are indeed deleterious (Eyre-Walker & Keightley 2007). This effect is clear at the scale of divergence among species (dN/dS) that differ in population size, with lineages having larger Ne tending to exhibit lower dN/dS (i.e., more effective purifying selection) (Wright & Andolfatto 2008; Ellegren 2009). For similar reasons, we also expect this stronger purifying selection to skew more strongly the variant frequency spectrum toward rare variants at such amino-acid changing sites (Tajima 1989). Nevertheless, hyperdiverse species might still segregate a high absolute number of non-synonymous polymorphisms.

Constraint on synonymous sites

Weak selection on synonymous sites provides an ideal test case for exploring the limits to natural selection introduced by effective population size. In many species, it is reasonable to assume that synonymous site evolution is unconstrained, with any codon skews being caused by mutational or gene conversion biases (Duret 2002; Hershberg & Petrov 2008). However, in species that have sufficiently large Ne, selection operates effectively even for weak benefits associated with translational efficiency, accuracy, and/or mRNA stability in highly-expressed genes, causing biased complements of alternative synonymous codons (Duret 2002; Chamary et al. 2006; Hershberg & Petrov 2008). Consequently, in such species, it is inappropriate to assume selective neutrality for synonymous sites in highly-expressed genes. Indeed, genes with more strongly skewed codon compositions, indicative of selection on codon usage, exhibit depressed levels of synonymous-site diversity in C. remanei (Dey et al. 2012) (Figure 2). A more appropriate estimate of neutral diversity corrects for the direct effects of selection on synonymous sites and, in the case of C. remanei, such correction yields a nearly 50% increase (Dey et al. 2012). While this adjustment accounts for direct selection on synonymous sites, it does not incorporate any effects of linked selection on diversity nor does it correct the variant frequency spectrum, which will tend to be skewed toward rare variants. Synonymous sites in lowly-expressed genes, with minimal effects of translational selection, may represent a tractable set of the ‘most unconstrained’ sites in the genome (Cutter & Moses 2011).

Several methods use polymorphism data to quantify the intensity of selection favoring ‘preferred’ codons (e.g., Akashi 1995; McVean & Vieira 1999; Cutter & Charlesworth 2006; Zeng 2010; Zeng & Charlesworth 2010). Notably, species with larger population size show more pronounced selection for codon bias (Petit & Barbadilla 2009). If a hyperdiverse species lacks evidence for effective selection on synonymous sites, then this would imply that Ne probably does not drive its exceptional levels of polymorphism; instead, a high mutation rate, recent admixture of differentiated subpopulations, or an artifact of polyploidy might be causes. Conversely, evidence of selection operating effectively on weakly selected sites should provide a good heuristic for deducing that the species has a very large long-term effective population size (e.g. free-living vs. parasitic nematodes, Cutter et al. 2006b). Further studies of the evolution of codon usage in hyperdiverse species will help dissect this interplay between mutation, genetic drift and natural selection (Box 4).

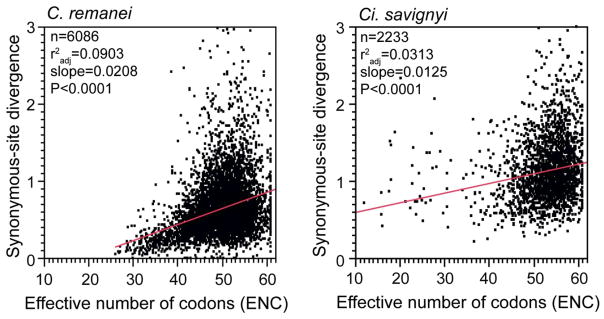

Box 4. Insights on Ciona from synonymous sites.

A brief case study of weak selection on synonymous sites permits some interesting insight into the potential causes of hyperdiversity in Ci. savignyi. A classic signature of translational selection is that rates of inter-species divergence will be depressed at synonymous sites (dS) in genes with stronger codon bias (i.e. lower dS for genes with lower values of the effective number of codons metric, ENC) (Sharp & Li 1987; Wright 1990). The more effective that selection is for biased codon usage over the long term, the clearer this pattern should be. Curiously, however, the dS × ENC association is rather weak in Ci. savignyi (Figure A), albeit significant even after incorporating GC3s as a covariate (not shown). Despite the nematode C. remanei having a much lower estimate of θneu, divergence of synonymous sites in the nematode are much more sensitive to codon usage (Figure A). This suggests that the hyperdiversity observed in Ci. savignyi might not result entirely from exceptionally large long-term Ne, but perhaps instead results from a high rate of mutation or possibly recent admixture among previously separated populations following its invasive spread across marine habitats. The related Ci. intestinalis is hypothesized to have a higher mutation rate than vertebrates, and also is comprised of two cryptic species (Tsagkogeorga et al. 2012). Alternatively, translational selection might have unusually low selection coefficients in Ciona.

Figure A. Weak association between codon bias and synonymous-site divergence in Ciona implies little effective long-term selection on synonymous sites.

Synonymous-site divergence for C. remanei reflects the lineage-specific values from (Cutter 2008a), based on a codon model of molecular evolution whereas Ci. savignyi values are half the Nei-Gojobori distance with orthologs of Ci. intestinalis (Small et al. 2007; Wang et al. 2010a); genes with values >3 excluded. ENC calculated with codonW (http://codonw.sourceforge.net); genes with values <10 excluded. See also Figure 2 for the relation between polymorphism and codon bias in these species.

Functional inference of non-coding regions

Unveiling the genomic regulatory code is critical for understanding developmental evolution and the genesis of many diseases (Wray 2007; Wittkopp & Kalay 2012). Despite rapid progress in mapping regulatory interactions between transcription factors (TF) and their targets (Gerstein et al. 2010; Negre et al. 2011; Niu et al. 2011; Shen et al. 2012), the identification of cis-regulatory response elements (CRE) within genomes still presents a major challenge. Comparative genomics is a powerful approach for identifying functional elements via phylogenetic footprinting, relying on the assumption that similar sequences between multiple species are conserved because of purifying selection to maintain similar functions (Figure 3). Although functional conservation is not always coupled with sequence conservation (Ludwig et al. 2005; Borneman et al. 2007), phylogenetic footprinting has been applied successfully to the human genome (Frazer et al. 2001; Dermitzakis et al. 2002; Frazer et al. 2004) and to the identification of CREs in model organisms (Kellis et al. 2003; Marri & Gupta 2009).

Figure 3. Functional genome annotation of cis-regulation response elements (CRE) based on the pattern of selective constraints among genomes.

Among-species comparative genomics is a powerful approach to identify conserved CREs by revealing phylogenetic footprints in the pattern of nucleotide divergence, but by nature fails to identify divergent and species-specific CREs (top). SNP shadowing, based on the pattern of allelic variation in hyperdiverse species, can circumvent some of the limitations of phylogenetic footprinting and helps refine cis-regulatory maps (bottom). Skewed measures of the variant frequency spectrum (e.g. Tajima’s D) can be applied in a similar manner. Functional elements could be unique to a lineage owing to novel regulatory effects or to positional turnover of element motifs.

A drawback of phylogenetic footprinting is its sensitivity to species divergence: if the species are too distant, then important elements will be missed, if the species are too close, then functional conservation cannot be distinguished from shared ancestry. A similar strategy, termed phylogenetic shadowing, aims to improve resolution by exploiting species that occupy key phylogenetic positions (Boffelli et al. 2003). With the high density of polymorphisms within hyperdiverse populations, fine-scale genome annotation may be derived in an analogous way by using population genetic criteria to identify functional elements. We term this approach ‘SNP shadowing,’ which uses the same logic that purifying selection will constrain allelic variation for functional elements below neutral expectations, and also shift the site frequency spectrum toward rare variants. Boffelli et al. (2004) elegantly demonstrated the validity of the approach with a small number of individuals of the species Ciona intestinalis, by identifying conserved non-coding sequences that regulate in cis the expression of two nearby early-development transcription factors. SNP shadowing can identify species-specific CREs that would be inaccessible from comparisons with distantly-related species, will assist in locating CREs with rearranged positions because of turnover (Doniger et al. 2005; Doniger & Fay 2007), and also may be particularly valuable in annotating the genomes of non-model hyperdiverse species. Although perturbations of patterns of polymorphism by selective sweeps, background selection or mutational cold-spots could complicate the detection of functional elements, applying the criterion of selective constraints in combination with other approaches such as the clustering of TF binding sites and assays of epigenetic features is likely to provide high resolution cis-regulatory maps of the genome (Hardison & Taylor 2012).

Species and speciation

Standard coalescent theory tells us that the genealogical history of a given neutrally-evolving locus traces to a single common ancestor 4Ne generations ago, on average, and that we expect neutral alleles for >95% of loci to have single common ancestors within the last 6Ne generations (Hein et al. 2004 p. 24). A pair of species will be reciprocally monophyletic at 95% of loci typically only after >9Ne generations (Hudson & Coyne 2002). For hyperdiverse species with large Ne, such time depths will be very long ago. Consequently, hyperdiverse sister species will either (1) share very ancient most recent common ancestors, if most loci are reciprocally monophyletic, implying low speciation rates, or (2) share with each other a great deal of ancestral polymorphism. Ancestral polymorphism among closely-related species will create extensive gene tree discordance, making it essential to apply isolation-with-migration types of approaches to study differentiation (Hey 2006; but see Becquet & Przeworski 2009; Strasburg & Rieseberg 2010; Hey & Pinho 2012) and providing an interesting perspective to the divergence with gene flow debate (Porter & Johnson 2002; Nosil 2008; Pinho & Hey 2010).

It is challenging to discern whether hyperdiversity might hinder or facilitate speciation. On the one hand, hyperdiverse species may tolerate more easily the introgression of divergent genetic material through hybridization between populations or incipient species. Ecological and life-history characteristics that promote hyperdiversity – such as having large ranges with high dispersal – also may counteract extrinsic barriers to reproductive isolation. On the other hand, haplotypes with extremely dense differences might hinder recombination and DNA repair, which could counteract species cohesion (Harfe & Jinks-Robertson 2000). When coupled with local adaptation, population structure across a broad geographic range can accelerate speciation (Gavrilets 2003). Hyperdiverse taxa will harbor an abundance of raw material for divergent local adaptation, the crux of ecological speciation scenarios (Rundle & Nosil 2005), but divergent selection may be impotent to yield complete reproductive isolation unless it is sufficiently strong to offset gene flow. These features likely contribute to the observed high overall polymorphism within Mimulus (Sweigart & Willis 2003), Paramecium (Catania et al. 2009), and other species complexes.

Does high Ne or high μ affect species diversification rates? Using Hey’s (2009) heuristic population genetic criteria for identifying species (separated for at least 1Ne generations with migration rate Nem less than 1), it is clear that the maximum rate of speciation must inevitably be slower for lineages with larger population sizes (see also Nei et al. 1983; Gavrilets 2003). However, this genealogical species concept differs from the more broadly useful biological species concept in genetic work on reproductive isolation (Coyne & Orr 2004). ‘Ubiquitous dispersal’ of superabundant, very small organisms – which likely are predisposed to hyperdiversity – also is proposed to limit both species diversification and extinction (Fenchel 1993; Finlay 2002). Based on different logic (Gavrilets 2003; Pagel et al. 2006; Venditti & Pagel 2010) – namely, bottlenecks or extreme subdivision causing accelerated fixation of genetic differences and that induce reproductive isolation – a similar negative effect of population size on net diversification rates has been predicted. Note that we presume that time is measured in units of generations; as we expect hyperdiverse taxa typically to have short generation times (Box 2), this must be appropriately accounted in contrasts of net speciation rates. Because large Ne also can retard extinction (Wright 1983; Gaston 2000), it is a challenge to disentangle speciation from extinction when evaluating net diversification rates (Coyne & Orr 2004).

Lanfear et al. (2010) recently concluded that bird taxa with higher mutation rates tend to have higher net speciation rates. In a related example, Venditti and Pagel (2010) similarly reported a positive correlation between rate of diversification and synonymous-site substitution. If positive associations between speciation and mutation rates prove general, and provided that taxa with higher mutation rates will exhibit higher estimates of θneu, then we might expect taxa with more polymorphism to show greater net diversification rates – contrary to the above predictions based on Ne. Sexual selection also can potentially drive faster speciation rates when population sizes are larger (Gavrilets 2000). Further work is required to understand the balance of factors important for diversification in the context of hyperdiversity, including a species’ propensity for local adaptation, mutation, and extinction, as well as its susceptibility to geographic or other barriers to gene flow.

Linkage disequilibrium and recombination

Provided that a population’s hyperdiversity is a byproduct of large Ne, rather than high μ, we also expect the effective rate of recombination to be high, as measured by the population recombination parameter, ρ = 4Nec (where c is the per-generation recombination rate between a pair of loci or polymorphic variants). It then follows that linkage disequilibrium (LD) in the population should be low, overall, and will decay rapidly within the genome as a function of the distance between loci or polymorphic sites. LD does decay rapidly in hyperdiverse Caenorhabditis (Cutter et al. 2006a; Wang et al. 2010b; Dey et al. 2013). A beneficial consequence of this is that population genetic models that assume free recombination will provide a very good approximation for many applications, even for SNPs that are physically quite close together. However, high diversity means that finite-sites models of mutation should be implemented in the estimation of LD (Fearnhead & Donnelly 2001). A drawback to such rapid breakdown of LD is that population association mapping techniques for identifying the genetic basis of phenotypic variation will only find successfully the small subset of quantitative trait loci (QTL) that are extremely close to the markers used for genotyping (Ioannidis et al. 2009). Given a QTL under such circumstances, however, identifying causal nucleotide changes would then be relatively easy. As genome-wide re-sequencing of population samples becomes mainstream (Pool et al. 2010), this concern for association mapping will largely be obviated, particularly for compact genomes like those of Caenorhabditis (100 – 150 Mb) and Drosophila (150 – 200 Mb).

Hyperdiverse populations also offer an opportunity to study the pattern and process of non-crossover recombination (gene conversion) on a finer scale than in traditional systems. The high density of SNPs means that gene conversion tract lengths can be defined with greater precision (Sawyer 1989). Exploiting genomic heterogeneity in nucleotide composition and SNP density should facilitate analyses of G/C-nucleotide biased conversion (Marais 2003) and heterozygosity-dependence (Hilliker et al. 1991; Stephan & Langley 1992). High heterozygosity might inhibit the gene conversion repair of DNA double-strand breaks, with important evolutionary consequences (Stephan & Langley 1992; Harfe & Jinks-Robertson 2000). Incorporating gene conversion into estimation of ρ also is critical in hyperdiverse taxa (Andolfatto & Nordborg 1998; Cutter 2008b). Thus, study of hyperdiverse organisms should provide new insights into the mechanisms and evolutionary consequences of non-crossover recombination, particularly when coupled with the molecular tools developed for functional interrogation of related model organisms (Robert et al. 2008).

Just as the middle of the last century was plagued by the question of how could there be so much allozyme diversity in populations (Lewontin 1974), we now face the opposite challenge of explaining why neutral sequence diversity is not even greater than it is in species with large populations (Frankham 2012; Leffler et al. 2012). Recurring hard selective sweeps provide one plausible answer (Maynard Smith & Haigh 1974; Gillespie 2001), owing to linkage of selected targets to flanking loci causing reductions in neutral genetic variation through genetic hitchhiking. But, as discussed above, much selection is purifying (yielding reductions in diversity through background selection (Charlesworth et al. 1993; Charlesworth 2012)), and much of positive selection might not involve hard sweeps (Pritchard et al. 2010). By assessing the factors that control the interplay between selection and recombination in species with differing population size, with hyperdiverse species as a valuable extreme, we may better understand the confluence of factors that regulate natural genetic variation (Cutter & Payseur 2013).

Genome complexity

Effective population size is proposed as a critical factor in the dynamics of a variety of genomic features, including gene families (Lynch & Conery 2003a), the origin and loss of introns (Lynch 2002), operons (Lynch 2007), and interactome complexity (Fernandez & Lynch 2011). A difficulty with Ne-based explanations for genome complexity across the tree-of-life is that contrasts often are most stark between high-Ne prokaryotes and lower-Ne eukaryotes, thus conflating complexity and phylogenetic history (Lynch & Conery 2003b; Lynch 2006, 2007; Whitney & Garland 2010). Detailed studies of hyperdiverse eukaryotic lineages should provide a bridge to better test the generality of effective population size as a dominant factor in the evolution of genome architecture.

Studying population processes in hyperdiverse eukaryotes, particularly sexually-reproducing metazoans, provides an exceptional counterpoint to taxa with small population sizes. For example, this can involve comparisons of selection on segregating variation for the presence/absence of introns within genes (Li et al. 2009; Schrider et al. 2011b) or of operon gene composition (Cutter & Agrawal 2010). Operons are genomic structures in which multiple genes are transcribed in a single RNA transcript, which is subsequently processed for translation of the separate genes (Blumenthal 2004). Lynch (2007) proposed that operons originated in the common ancestors of eukaryotes and prokaryotes, but that these structures have only been retained in eukaryote lineages that typically experience large Ne. Indeed, operons are common in the genomes of Caenorhabditis and Ciona, encompassing 15–20% of all encoded genes (Blumenthal et al. 2002; Satou et al. 2008; Cutter & Agrawal 2010). The evolution of different modes of regulatory control over gene expression also are hypothesized to be sensitive to population size, with enhancers favored over suppressors in large populations (Gerland & Hwa 2009). Horizontal transfer of genetic material is common in bacteria, but its potential role in eukaryote evolution is poorly known, except that it seems to most often involve transmission of transposable elements (Schaack et al. 2010). Given that species with higher diversity tend to have fewer transposable elements and smaller genomes (Lynch & Conery 2003b), and that theoretical models implicate stronger selection for element elimination in large populations (Brookfield & Badge 1997), perhaps horizontal transfer of transposable elements would play a smaller role in genome architecture in hyperdiverse lineages. Hyperdiverse species may therefore provide a unique opportunity to study the ongoing molecular evolution and function of these intriguing genomic features.

The large pool of neutral mutations in hyperdiverse populations also can play a creative role in the origin of evolutionary novelties by defining the substrate upon which subsequent evolution is contingent (Stoltzfus 1999; Lynch 2007). One way that neutral mutations can influence the trajectory of evolution is through epistatic interactions between the fitness effect of a mutation and its genetic background (Kimura 1985). It is through these epistatic interactions with neutral mutations that alleles that otherwise would be deleterious can alter-gene function and spread in populations (Zhang & Rosenberg 2002; Ortlund et al. 2007).

More drastic features of genome complexity – such as segmental and whole-genome duplications, karyotype changes, copy number variants, large inversions and other rearrangements – also might be sensitive to large effective population size. Specifically, if small Ne and genetic drift facilitate the fixation of such dramatic mutational events in many organisms, then we might expect large Ne taxa to have them only rarely as polymorphisms within species (Jakobsson et al. 2008) or as differences between species, because drift is a proportionately weaker force. Moreover, when large-scale differences do become fixed in hyperdiverse taxa, we could more confidently conjecture that positive selection drove the fixation and rapid accumulation of such large-scale changes to genome architecture.

Concluding remarks

Hyperdiversity in eukaryotes opens up exciting opportunities to enlighten our understanding of the evolutionary process. Such organisms represent a valuable bridge between bacteria and typical multicellular eukaryotic study systems, with key attributes of each: high polymorphism and enormous population size coupled with complex development and sexual reproduction. These features make hyperdiverse species novel models for dissecting a variety of fundamental issues, from genome complexity to modes of adaptation, mutational dynamics, and fine-scale inference of sequence function. While we anticipate that the near future will reveal many eukaryote taxa harboring extreme polymorphism levels, through application of emerging high-throughput sequencing technologies to molecular ecology, the existence of known hyperdiverse relatives of the model organisms C. elegans and D. melanogaster are particularly promising for detailed laboratory analyses.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Michael Brudno for providing sequence alignments for Ciona, to Josh Shapiro for providing diversity values for C. elegans, and to Heather Maughan for providing diversity values for H. influenzae. We thank three anonymous reviewers for their comments on the manuscript and Stephen Wright for insightful discussions. ADC is supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, grants from the National Institutes of Health, and by a Canada Research Chair. RJ is supported by a fellowship from the Ontario Ministry of Research and Innovation.

Glossary

- Hyperdiversity

Nucleotide diversity, defined as the average proportion of nucleotides that differ between a random pair of alleles, greater than or equal to 5%

- Ne

The effective population size that corresponds to an idealized ‘Wright-Fisher’ population of size N, which describes the rate of genetic drift in the population

- θ

The population mutation rate parameter (Neμ, mutation rate μ), estimated from segregating polymorphisms within a population

- α

The proportion of nonsynonymous site changes that are fixed by positive selection

- dN

The rate of accumulation of fixed changed at nonsynonymous sites in protein-coding sequences

- dS

The rate of accumulation of fixed changes at synonymous sites in protein-coding sequences

- site frequency spectrum

The distribution of single nucleotide variant frequencies within a population sample

- codon bias

The unequal use of alternative synonymous codons caused by mutational biases, gene conversion biases, or selection

- inbreeding depression

The reduction of fitness observed in the progeny of crosses from related genotypes because of the expression of recessive mutations that are masked in the parents

- ancestral polymorphism

Polymorphism present in an ancestral population that can lead to shared polymorphism in descendant species or discordance of gene trees and species trees

- reciprocal monophyly

Two lineage groups in which genes share a more recent common ancestor within each group than with any other lineages, leading to perfectly congruent gene trees and species trees

- linkage disequilibrium

The non-random association of variants within a population sample

- hard selective sweep

Fixation of a new beneficial allele by positive selection that induces linked variants to also become fixed by genetic hitchhiking

- soft selective sweep

Fixation of a beneficial allele by positive selection acting on pre-existing genetic variants or on a set of equivalent alleles that arose through multiple independent mutational events

- fitness flux

A measure of adaptation quantified from an excess of beneficial over deleterious allele fixations across the genome

- SNP

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- STR

Short tandem repeat or microsatellite locus

Footnotes

Data Accessibility

Citations for data sources are given in figure legends.

Literature Cited

- Abouheif E, Akam M, Dickinson WJ, et al. Homology and developmental genes. Trends in Genetics. 1997;13:432–433. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(97)01271-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abouheif E, Wray GA. Evolution of the gene network underlying wing polyphenism in ants. Science. 2002;297:249–252. doi: 10.1126/science.1071468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akashi H. Inferring weak selection from patterns of polymorphism and divergence at silent sites in Drosophila DNA. Genetics. 1995;139:1067–1076. doi: 10.1093/genetics/139.2.1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amos W. Even small SNP clusters are non-randomly distributed: is this evidence of mutational non-independence? Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2010;277:1443–1449. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2009.1757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen EC, Gerke JP, Shapiro JA, et al. Chromosome-scale selective sweeps shape Caenorhabditis elegans genomic diversity. Nature Genetics. 2012;44:285–290. doi: 10.1038/ng.1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andolfatto P, Nordborg M. The effect of gene conversion on intralocus associations. Genetics. 1998;148:1397–1399. doi: 10.1093/genetics/148.3.1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andolfatto P, Wong KM, Bachtrog D. Effective population size and the efficacy of selection on the X chromosomes of two closely related Drosophila species. Genome Biology and Evolution. 2011;3:114–128. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evq086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andres AM, Hubisz MJ, Indap A, et al. Targets of balancing selection in the human genome. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2009;26:2755–2764. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbogast BS, Edwards SV, Wakeley J, Beerli P, Slowinski JB. Estimating divergence times from molecular data on phylogenetic and population genetic timescales. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 2002;33:707–740. [Google Scholar]

- Bachtrog D, Andolfatto P. Selection, recombination and demographic history in Drosophila miranda. Genetics. 2006;174:2045–2059. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.062760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker CR, Tuch BB, Johnson AD. Extensive DNA-binding specificity divergence of a conserved transcription regulator. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 2011;108:7493–7498. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019177108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barriere A, Yang SP, Pekarek E, et al. Detecting heterozygosity in shotgun genome assemblies: Lessons from obligately outcrossing nematodes. Genome Research. 2009;19:470–480. doi: 10.1101/gr.081851.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton N. Understanding adaptation in large populations. PLoS Genetics. 2010;6:e1000987. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton NH. Genetic hitchhiking. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London Series B-Biological Sciences. 2000;355:1553–1562. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2000.0716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudry E, Depaulis F. Effect of misoriented sites on neutrality tests with outgroup. Genetics. 2003;165:1619–1622. doi: 10.1093/genetics/165.3.1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becquet C, Przeworski M. Learning about modes of speciation by computational approaches. Evolution. 2009;63:2547–2562. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2009.00662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begun DJ, Holloway AK, Stevens K, et al. Population genomics: whole-genome analysis of polymorphism and divergence in Drosophila simulans. PLoS Biology. 2007;5:e310. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blueweiss L, Fox H, Kudzma V, et al. Relationships between body size and some life history parameters. Oecologia. 1978;37:257–272. doi: 10.1007/BF00344996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal T. Operons in eukaryotes. Briefings in Functional Genomics and Proteomics. 2004;3:199–211. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/3.3.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]