Abstract

Introduction

The purpose of this study was to determine the safety, tolerability and effectiveness of daily administration of an orally administered pantothenic acid-based dietary supplement in men and women with facial acne lesions.

Methods

A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of adults previously diagnosed with mild to moderate acne vulgaris was performed. Subjects were randomized to the study agent, a pantothenic acid-based dietary supplement, or a placebo for 12 weeks (endpoint). The primary outcome of the study was the difference in total lesion count between the study agent group versus the placebo group from baseline to endpoint. Secondary measurements included differences in mean non-inflammatory and inflammatory lesions, Investigators Global Assessment and Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) scores between the two groups. Investigator assessment of overall improvement and skin photographs were also taken. Safety and tolerability endpoints were the assessment of adverse events and measurement of serum complete blood count and hepatic function.

Results

Forty-eight subjects were enrolled and 41 were evaluable. There was a significant mean reduction in total lesion count in the pantothenic acid group versus placebo at week 12 (P = 0.0197). Mean reduction in inflammatory lesions was also significantly reduced and DLQI scores were significantly lower at week 12 in the pantothenic acid group versus placebo. The study agent was safe and well tolerated.

Conclusions

The results from this study indicate that the administration of a pantothenic acid-based dietary supplement in healthy adults with facial acne lesions is safe, well tolerated and reduced total facial lesion count versus placebo after 12 weeks of administration. Secondary analysis shows that the study agent significantly reduced area-specific and inflammatory blemishes. Further randomized, placebo-controlled trials are warranted.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s13555-014-0052-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Acne, Clinical study, Dermatology, Dietary supplement, Facial lesions, Natural products, Pantothenic acid, Quality of life

Introduction

Acne is a common disease of the hair follicles in the skin associated with an oil gland. Facial lesions due to acne can affect up to 95% of people during their lifetime and frequently starts in teens, but often persists or begins during adulthood [1]. Lesions include non-inflammatory and inflammatory types. There are many common treatments for acne lesions including drugs, over the counter products and procedures such as laser therapy [2–4]. There has also been an increasing interest in the use of natural products for skin health such as vitamin C, other antioxidants, botanicals and omega-3 fatty acids [5, 6]. One agent that has shown promise in reducing facial acne lesions is pantothenic acid (vitamin B5). Pantothenic acid is a water-soluble member of the B-vitamin family that is converted into 4’-phosphopantetheine, which is then converted to co-enzyme A (CoA) via adenosine triphosphate [7, 8]. Pantothenic acid regulates epidermal barrier function and keratinocytes differentiation via CoA metabolism. Skin softening ability of pantothenic acid-based topical products have also been demonstrated in a recent clinical trial [9–11]. A recent feasibility study has also shown that daily oral supplementation of a nutritional agent containing pantothenic acid for 8 weeks was feasible and safe. Secondary endpoints of that study demonstrated that there was a reduction in total facial acne lesions over the 8-week study period [12]. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to further test the pantothenic acid-based supplement in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical study to assess the effectiveness of the study agent in reducing global facial lesion count versus placebo over a 12-week study period.

Methods

Subjects

Fifty-one adult subjects (average age) with ≥50 non-inflammatory and up to 50 inflammatory lesions were recruited at 2 dermatology sites. The main exclusion criteria included pregnancy and lactation, known allergy or hypersensitivity to any of the constituents in the study agent and current use of any prescription treatment (oral or topical) for acne (washout allowed). Past use of any procedures including laser therapy, microdermabrasion and other procedures was prohibited if the study participant had received it within the past three months.

Compliance with Ethics

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Quorum Institutional Review Board, Seattle, WA-Accredited by the Accreditation of Human Research Protection Programs and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 and 2008. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Study Design

The study was performed between August 2012 and November 2013. Once informed consent was given, consecutive human subjects with facial lesions as demonstrated by total lesion count were assessed and randomized 1:1 to either the study agent, a pantothenic acid-based dietary supplement herein referred to as study agent (Pantothen™, Avilan Marketing LLC, New York, USA) or an asthetically matched placebo tablet. The study agent was verified by the manufacturer to contain the correct dosage of ingredients as listed (certificate of analysis not shown). The ingredients in the placebo table were considered inert and the placebo tablet did not contain any active ingredients (certificate of analysis for the placebo tablet not shown). The dosage of the study agent or the placebo administered was two tablets taken orally, twice a day with food for 12 weeks. Each four-tablet dose of the study agent contained 2.2 g of pantothenic acid. The primary outcome of the study was the reduction in total facial lesions at the study endpoint (week 12) in the study agent group versus the placebo group. Secondary outcomes were changes in non-inflammatory lesions at specific facial areas, change in inflammatory lesions (total and specific facial areas), change in the Investigators Global Assessment (IGA) and change in scores on the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) from baseline to week 12 between the two groups. The DLQI is a general questionnaire that evaluates quality of life (QOL) in dermatology patients and consists of ten questions about symptoms, feelings, daily activities, type of clothing, social or physical activities, exercise, job or education, interpersonal relationships, marriage relationships, and relationship to dermatologic symptoms. Higher scores indicate a poorer QOL [13]. Finally, we assessed investigator overall improvement as deemed by the study doctor using a 5-point scale: 2 = marked improvement, 1 = slight improvement, 0 = unchanged, −1 = worsening, −2 = marked worsening at the study endpoint (week 12).

Statistics

The study sample size had 80% power to detect a significant difference in total lesions from baseline to week 12 of the study between the two groups and significance was set at 0.05. The IGA and Investigator Overall Improvement (IOI) evaluations were performed on a 5-point scale and transformed to numerical values (0–5) and the mean, standard deviation and percentages were calculated. Differences in DQLI scores were analyzed from baseline to week 12 using a t test. A last observation carried forward method was prospectively defined and used for missing data if the subjects had data at least for the first two visits. The tolerability and safety outcome was the incidence of adverse effects, complication/illness and/or serious medical events due to the study agent as measured by the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI) Common Criteria for Adverse Event Reporting Version 3.0 [14] and by analysis of serum complete blood count and hepatic function from baseline to week 12 (Esoterix™, LabCorp, Cranford, NJ, USA). Descriptive analyses were performed for demographics utilizing characteristic measures such as mean, standard deviation, and range.

Results

Subjects

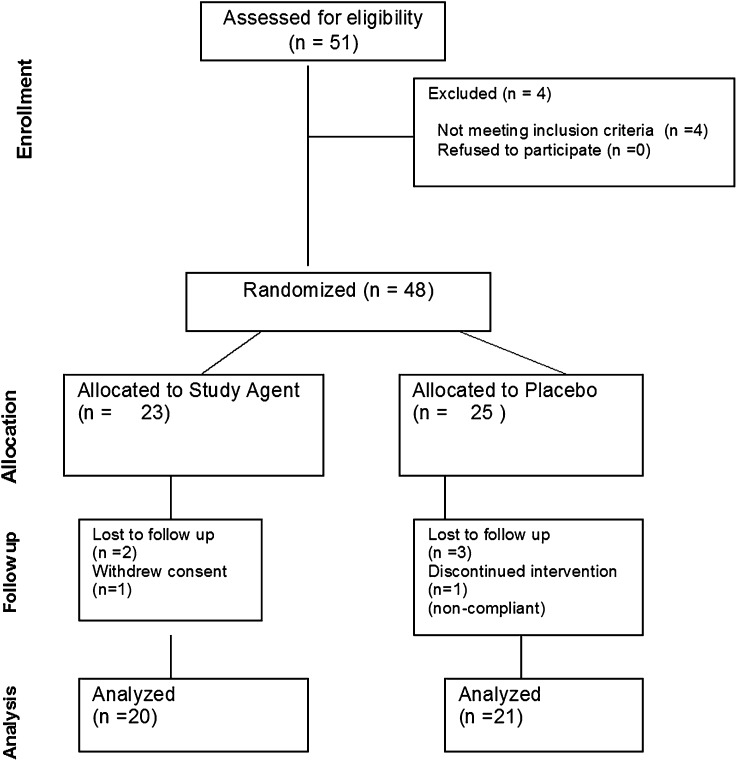

Fifty-one subjects were screened, forty-eight were randomized and forty-one subjects were evaluable. Of those, five subjects were lost to follow-up, one withdrew consent and one was dropped for non-compliance. None of the subjects were terminated due to an adverse event (AE) (see Fig. 1 for study flow). Demographics and baseline characteristics are listed in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Consort diagram representing subject flow throughout the study

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and characteristics

| Characteristic | Arm 1: study agent | Arm 2: placebo | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 20 | 21 | – |

| Mean age, years (SD) | 29.7 (7.5) | 27.1 (3.8) | – |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 3 | 2 | – |

| Female | 17 | 19 | – |

| BMI (SD) | |||

| All | 26.2 (5.7) | 26.1 (6.7) | – |

| Race (no. [%]) | |||

| White | 10 [52.6] | 10 [47.6] | – |

| Black | 6 [31.6] | 4 [19.05] | – |

| Asian | 2 [10.5] | 4 [19.05] | – |

| Other | 1 [5.3 | 3 [14.3] | – |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Latino | 3 [15.8] | 3 [14.3] | – |

| Non-Latino | 16 [84.2] | 18 [85.7] | – |

| Baseline blemish count [mean (SD)] | |||

| Total mean (SD) | 51.3 (22.4) | 71.8 (42.8) | 0.071 |

| Non-inflammatory | 41.2 (16.7) | 48.9 (33.7) | 0.374 |

| Inflammatory | 15.3 (8.9) | 17.3 (14.3) | 0.603 |

BMI body mass index, SD standard deviation

Efficacy Analysis

Primary Endpoint

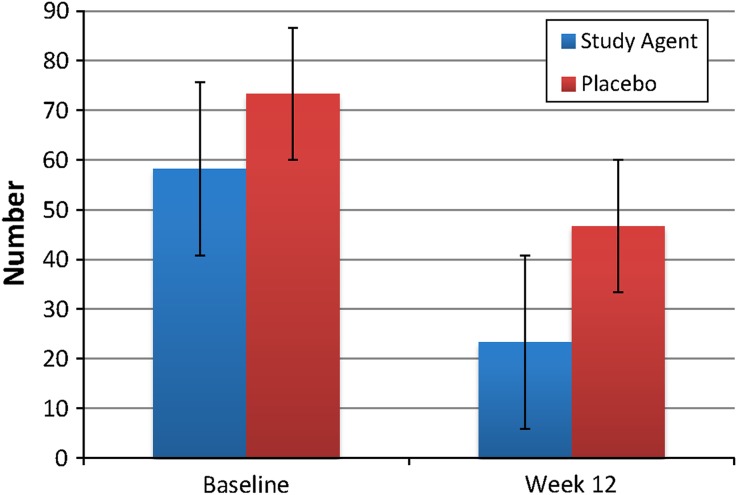

There was a statistically significant decrease in the number of total facial lesions over the study period in the subjects taking the study agent versus placebo (P = 0.0197) (Fig. 2). Lesion count in the study agent versus placebo group was reduced by 68.21%.

Fig. 2.

Difference in total lesion count between study agent and placebo at week 12. *P = 0.0197 study agent versus placebo

Secondary Endpoints

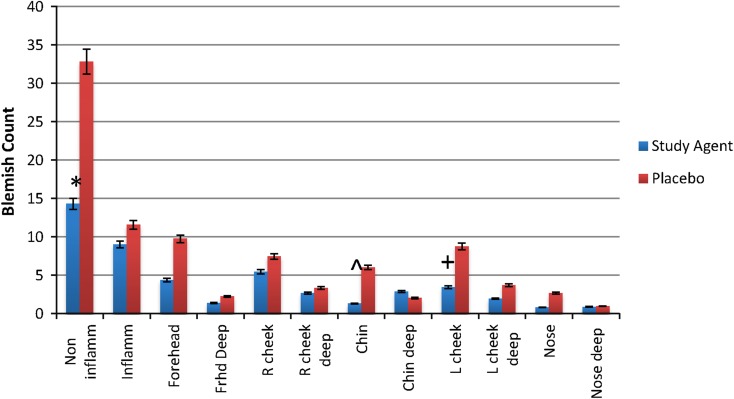

Analysis of the number of non-inflammatory blemishes demonstrated a significant mean reduction in lesion count from baseline to week 12 in the study agent versus the placebo group (P = 0.0162) (Fig. 3). Breakdown of changes in lesion count per facial area also demonstrated significance in numerous categories in the study agent versus placebo group (Fig. 3). Overall efficacy, as measured by the IGA, was significantly improved for the study agent group versus placebo at week 12 (P = 0.045) as 42.85% versus 14.28% were downgraded to grade 1 (almost clear skin, few non-inflammatory lesions and no more than 1 inflammatory lesion). Figure 4a, b demonstrates examples of clearer skin in both inflammatory and non-inflammatory blemishes from baseline versus week 12 in subjects in the study agent group.

Fig. 3.

Lesion count by facial area at week 12. *P = 0.0162, **P = 0.018, ^ P = 0.0024, + P=0.0192

Fig. 4.

a Representative photograph of forehead non-inflammatory lesion at baseline versus week 12 in a single subject in the study agent group. b Representative photograph of a subject with mixed lesions (chin and cheek, inflammatory and non-inflammatory) at baseline versus week 12, single subject in the study agent group

Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) and Overall Investigator Assessment of Improvement

The mean ± standard deviation (SD) DLQI score was lower at week 12 from baseline between the study agent and placebo group (baseline scores, 7.6 ± 5.3 versus 9.53 ± 7.69, P = 0.44 study agent versus placebo, versus week 12 scores, 1.93 ± 1.90 and 5.3 ± 4.8 study agent versus placebo, respectively, P = 0.022). The overall investigator assessment of improvement at week 12 as measured by a 5-point scale demonstrated that 85.7% of subjects had ≥1 rank improvement in the study agent versus the placebo group (35.7%).

Primary Safety and Tolerability Endpoints

The study agent was well tolerated. One subject withdrew consent due to complaint that the tablet size was too large. There were no differences in complete blood count or hepatic function as measured at week 12 from baseline in any subjects in either the study agent or placebo groups (data not shown). There were two AEs reported, one of fatigue (placebo group) and one of shingles (study agent group) that were deemed unrelated to the study agent by the study principal investigator. No serious AEs were reported during the study.

Discussion

Pantothenic acid (vitamin B5) is a water-soluble B-complex vitamin. In this study, volunteers with facial lesions who took a daily oral dose of a pantothenic acid-based dietary supplement demonstrated improved skin health versus those who took a placebo tablet. The results of this study further confirmed that it was safe and tolerable for healthy human volunteers to take a nutritional supplement containing pantothenic acid for 12 weeks. The results of this study showed that there was a greater than 67% reduction in the number of total facial lesions after 12 weeks of supplementation. Results also demonstrated that there was a significant reduction in the number of total and specific facial areas in non-inflammatory lesions after 12 weeks in the pantothenic acid group, improved scores on the IGA and improved overall investigators assessment at study endpoint. In addition, subjects in the study agent group demonstrated better quality of life as measured by the DLQI [13]; a well-validated quantitative questionnaire that measures the bother of unclear skin on patients’ QOL with regard to social, behavioral and mood indicators. Most importantly, the study agent was well tolerated and safe as demonstrated by minimal adverse events and no changes in serum blood chemistries.

The mechanism by which this occurs may be due to antibacterial and skin softening activity of pantothenic acid. Pantothenic acid is converted into 4′-phosphopantetheine that is then converted to CoA via adenosine triphosphate (ATP) [7]. CoA is a critical agent important in lipid metabolism and other cellular processes and it has been shown that pantothenic acid may regulate epidermal barrier function through proliferation and differentiation of keratinocytes via CoA metabolism [7, 15]. It is possible that the reduction in the amount of global skin lesions in volunteers following oral administration of the pantothenic acid-based study agent may function through these mechanisms. However, the exact mechanism of this effect is not understood. More recently the association between CoA metabolism and inflammation has also been suggested as it has been shown that the pantetheinase enzyme that recycles pantothenic acid and pantetheinase gene (vanin-1) knockout mice has been shown to be involved in the progression of inflammatory reactions [16]. The bioavailability of pantothenic acid has been reported in the range of 40–63% and amounts found in 24-h urine samples have been shown to correlate with this intake [17]. For example, avocados contain a wide variety of essential nutrients including pantothenic acid and essential fatty acids and studies have demonstrated that these correlate with improved health in persons who consume them [18].

In addition to physiologic mechanisms of action, this study also demonstrated that volunteers in the study agent group who demonstrated clear skin had improved quality of life as measured by a well-validated, quantitative questionnaire. It has been clearly shown that acne patients with poor facial skin have reduced quality of life with regard to dissatisfaction about appearance, social bother and even co-morbid depression. It has also been stressed that assessment of quality of life in studies testing any type of agent for facial acne lesions is important and strongly correlates with treatment success [19, 20].

Limitations of this study are its short duration intervention and that the study was powered to detect a difference in total lesions. If we aimed to look at the effects of the study agent in inflammatory lesions, a longer intervention period may be needed. Moreover, we are unable to measure long-term use and durability. Finally, there is always a possibility that milder, non-inflammatory lesions may resolve on their own by chance. Given that administration of study agent was safe, tolerable and demonstrated improvement in human facial lesions, further randomized, placebo-controlled studies are warranted.

Conclusions

The results from this study indicate that the administration of a pantothenic-based dietary supplement in healthy human adults with facial lesions is safe, well tolerated and reduces total facial lesion count versus placebo after 12 weeks of administration. Secondary analysis shows that administration of the study agent significantly reduced area-specific and inflammatory lesions. Further randomized, placebo-controlled trials are warranted.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

Sponsorship for this study was provided by Avilan Marketing LLC (Brooklyn, NY, USA). Article processing charge was provided by Nutraceutical Medical Research (New York, NY, USA).

Staff at Manhattan Medical Research (New York, USA) and Union Square Laser Dermatology (New York, USA) helped to provide care for study participants.

All named authors meet the ICMJE criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval for the version to be published.

Conflict of interest

MYang, B Moclair, V Hatcher, J Kaminetsky, M Mekas, A Chapas and J Capodice declare no conflict of interest.

Compliance with ethics

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Quorum Institutional Review Board, Seattle, WA-Accredited by the Accreditation of Human Research Protection Programs and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 and 2008. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

References

- 1.Goulden V, Stables GI, Cunliffe WJ. Prevalence of facial acne in adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(4):577–580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ingram JR, Grindlay DJ, Williams HC. Management of acne vulgaris: an evidence-based update. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35(4):351–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03683.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Knutsen-Larson S, Dawson AL, Dunnick CA, Dellavalle RP. Acne vulgaris: pathogenesis, treatment, and needs assessment. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30(1):99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams HC, Dellavalle RP, Garner S. Acne vulgaris. Lancet. 2012;379(9813):361–372. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60321-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Magin PJ, Adams J, Heading GS, Pond DC, Smith W. Complementary and alternative medicine therapies in acne, psoriasis, and atopic eczema: results of a qualitative study of patients’ experiences and perceptions. J Altern Complement Med. 2006;12(5):451–457. doi: 10.1089/acm.2006.12.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.El-Akawi Z, Abdel-Latif N, Abdul-Razzak K. Does the plasma level of vitamins A and E affect acne condition? Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31(3):430. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2006.02106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kelly GS. Pantothenic acid. Monograph. Altern Med Rev. 2011;16(3):263–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leung LH. Pantothenic acid deficiency as the pathogenesis of acne vulgaris. Med Hypotheses. 1995;44(6):490–492. doi: 10.1016/0306-9877(95)90512-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kobayashi D, Kusama M, Onda M, Nakahata N. The effect of pantothenic acid deficiency on keratinocyte proliferation and the synthesis of keratinocyte growth factor and collagen in fibroblasts. J Pharmacol Sci. 2011;115(2):230–234. doi: 10.1254/jphs.10224SC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jerajani HR, Mizoguchi H, Li J, Whittenbarger DJ, Marmor MJ. The effects of a daily facial lotion containing vitamins B3 and E and provitamin B5 on the facial skin of Indian women: a randomized, double-blind trial. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76(1):20–26. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.58674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Camargo FB, Jr, Gaspar LR, Maia Campos PM. Skin moisturizing effects of panthenol-based formulations. J Cosmet Sci. 2011;62(4):361–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Capodice JL. Feasibility, tolerability, safety and efficacy of a pantothenic acid based dietary supplement in subjects with mild to moderate facial acne blemishes. J Cosmet Dermatol Sci Appl. 2012;2:132–135. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)—a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19(3):210–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1994.tb01167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program, Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, Version 3.0, DCTD, NCI, NIH, DHHS; 2003. http://ctep.cancer.gov. Last accessed April 17, 2014.

- 15.Gaisa NT, Köster J, Reinartz A, Ertmer K, Ehling J, Raupach K, Perez-Bouza A, Knüchel R, Gassler N. Expression of acyl-CoA synthetase 5 in human epidermis. Histol Histopathol. 2008;23(4):451–458. doi: 10.14670/HH-23.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nitto T, Onodera K. The linkage between coenzyme a metabolism and inflammation: roles of pantetheinase. J Pharmacol Sci. 2013;123(1):1–8. doi: 10.1254/jphs.13R01CP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eissenstat BR, Wyse BW, Hansen RG. Pantothenic acid status of adolescents. Am J Clin Nutr. 1986;44(6):931–937. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/44.6.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dreher ML, Davenport AJ. Hass avocado composition and potential health effects. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2013;53(7):738–750. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2011.556759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barnes LE, Levender MM, Fleischer AB, Jr, Feldman SR. Quality of life measures for acne patients. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30(2):293–300. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gollnick HP, Finlay AY, Shear N. Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne. Can we define acne as a chronic disease? If so, how and when? Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9(5):279–284. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200809050-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.