Abstract

Objectives

Given the conflicting definitions of “generalized osteoarthritis” (GOA) in the literature, we performed a systematic review of GOA definitions, risk factors, and outcomes.

Methods

We searched the Medline literature with terms: osteoarthritis, generalized, polyarticular, multiple joint, and multi-joint, to obtain articles related to GOA, following evidence-based guidelines. Titles and abstracts of 948 articles were reviewed, with full text review of 108. Data were extracted based on pre-specified criteria for 74 articles plus 24 identified through bibliographic review (total=98).

Results

Twenty-four large cohorts (n~30,000) were represented along with numerous clinical series (n~9000), across 22 countries and 60 years (1952–2012). No less than 15 definitions of GOA were given in 30 studies with a stated GOA definition; at least 6 groups used a summed score of joints or radiographic grades. Prevalence estimates based on these GOA definitions were 1–80%, although most were 5–25%. Increased risk and progression of GOA was associated with age, female sex, and genetic/familial factors. Associations with increased body mass index or bone mineral density were not consistent. One study estimated the heritability of GOA at 42%. Collagen biomarker levels increased with number of involved joints. Increased OA burden was associated with increased mortality and disability, poorer health and function.

Conclusion

While there remains no standard definition of GOA, this term is commonly used. The impact on health may be greater when OA is in more than one joint. A descriptive term, such as multi-joint or polyarticular OA, designating OA of multiple joints or joint groups, is recommended.

INTRODUCTION

Generalized osteoarthritis (GOA) is a term that is widely used in the literature in an attempt to describe the often polyarticular nature of osteoarthritis (OA). Polyarticular involvement in OA was described as early as the mid-1800’s (although this report also included descriptions of inflammatory arthritis)(1), followed by a description of “chronic degenerative polyarthritis” of menopause in 1926(2), and the first clearly recognizable description of GOA in 1952(3). Unfortunately, to date, there is no clear, consistent definition for what actually constitutes GOA, and numerous alternative terms are used (e.g. polyarticular OA, multijoint or multiple joint OA, or lists of affected joints). One reference often cited as a definition of GOA (Lawrence 1969, (4)) actually explores two definitions (3 or more, and 5 or more joints). Although it remains clear that multiple joints are commonly involved in OA, the definition of the term GOA itself remains vague at best, and misleading at worst, since this term cannot be understood in the absence of a clearly stated definition by the authors, which may or may not be provided.

To examine the strengths and limitations of current definitions of GOA and the associations between GOA and risk factors and outcomes, we reviewed the literature reporting on multiple joint involvement in OA since 1946 to form a systematic summary of the work to date. Through this effort, we hope to identify difficulties and weaknesses with the current body of literature, and to suggest ways to improve the study of polyarticular involvement in OA, which we view as an important consideration in ongoing research which so often focuses on single joint sites in isolation.

METHODS

Following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, and with the assistance of a professional research librarian, we performed a Medline (1946-present) search first on March 23, 2011 and updated on September 25, 2012 for articles related to GOA (osteoarthritis, osteoarthrosis, degenerative joint disease, generalized, polyarticular, global, nodal, multiple joint, multi-joint, etc.) and published in a clinical journal, limited to English language articles in human adults (age 19 years and up, see Table 1 for full search details). Given the lack of standardized terminology, we limited our search to Medline to obtain the most relevant articles. Initial inclusion criteria were a focus on OA and assessment of more than one joint site. Two coauthors (AEN and MWS) performed independent review of the identified abstracts, and disagreements between reviewers were resolved by consensus. The full text articles were then reviewed by two coauthors (AEN and YMG) to determine which would be carried forward to data extraction. Exclusion criteria were 1) lack of a clear definition of OA (any of radiographic, symptomatic, clinical, self-report) or 2) failure to report on more than one distant joint site (multiple joints within one site, such as multiple hand joints, or tibiofemoral and patellofemoral alone, was not sufficient). Again, disagreements were resolved by consensus. Additionally, one author (AEN) reviewed the bibliographies for all articles at the full text review step and identified further relevant papers that were also included for data extraction.

Table 1.

Search terms and limits with results from initial search*

| Search | Queries | Result # |

|---|---|---|

| #1 | Search "Joints"[Mesh] | 156488 |

| #2 | Search "Osteoarthritis"[Mesh] | 34719 |

| #3 | Search osteoarthritis | 43289 |

| #4 | Search osteoarthrosis | 261351 |

| #9 | Search coxarthrosis | 10408 |

| #10 | Search gonarthrosis | 776 |

| #11 | Search "degenerative joint disease" | 1471 |

| #12 | Search #2 or #3 or #4 or #9 or #10 or #11 | 262009 |

| Combining terms for osteoarthritis and its synonyms | ||

| #13 | Search generalized | 75464 |

| #14 | Search polyarticular | 1521 |

| #15 | Search global | 147310 |

| #16 | Search nodal | 26481 |

| #17 | Search “multiple joint” or “multi-joint” or “multi-site” | 2276 |

| #18 | Search (hand* AND knee*) OR (hand* AND hip*) OR (knee* AND hip*) | 17027 |

| #19 | Search #13 or #14 or #15 or #16 or #17 or #18 | 267668 |

| Combining polyarticular with its synonyms to get at the concept of multiple joints | ||

| #20 | Search #12 and #19 | 11385 |

| The overlap—articles about polyarticular OA. | ||

| #21 | Search #12 and #19 and #1 | 4186 |

| #22 | Search Gout[Mesh] | 8695 |

| #23 | Search "Arthritis, Rheumatoid"[Mesh] | 89074 |

| #24 | Search "Arthritis, Psoriatic"[Mesh] | 2676 |

| #25 | Search #22 or #23 or #24 | 98762 |

| #26 | Search #21 NOT #25 | 3260 |

| Removing references about inflammatory arthritis. | ||

| #27 | Search #26 Limits: Humans, English | 2391 |

| Limiting to Human populations and English language articles. | ||

| #28 | Search neuropathy OR neuropathies | 53087 |

| #29 | Search skeletal muscle* OR "Muscle, Skeletal"[Mesh] | 213567 |

| #30 | Search "Surgical Procedures, Operative"[Mesh] | 2008342 |

| #31 | Search #28 or #29 or #30 | 2235850 |

| #32 | Search #27 NOT #31 | 1715 |

| Removing unwanted subjects | ||

| #33 | Search #32 Limits: All Adult: 19+ years | 1210 |

| Limiting to adults | ||

| #34 | Search #33 Limits: Clinical Trial, Letter, Meta-Analysis, Randomized Controlled Trial, Review, Case Reports, Classical Article, Clinical Conference, Clinical Trial, Phase I, Clinical Trial, Phase II, Clinical Trial, Phase III, Clinical Trial, Phase IV, Comment, Comparative Study, Congresses, Consensus Development Conference, Consensus Development Conference, NIH, Controlled Clinical Trial, Evaluation Studies, Guideline, Historical Article, Journal Article, Lectures, Multicenter Study, Twin Study, Validation Studies | 1209 |

| #35 | Search #34 Limits: Core clinical journals | 307 |

| Limiting to Core Clinical Journals – these were kept. | ||

| #38 | Search Orthopaedic Journals (full listing available from authors) | 228478 |

| #39 | Search #34 and #38 | 321 |

| Limiting to the 115 Orthopedic journals. These were kept. | ||

| #40 | Search Rheumatology Journals (full listing available from authors) | 115904 |

| #41 | Search #34 and #40 | 516 |

| Limiting to the 68 Rheumatology journals. These were kept. | ||

| #42 | Search "Am J Epidemiol"[Journal] | 10887 |

| #43 | Search #34 and #42 | 2 |

| Limiting to Am J Epidemiol. These were kept. | ||

| #44 | Search #35 or #39 or #41 or #43 | 855 |

| Combining Core clinical, Orthopaedic journals, Rheumatology journals, and American Journal of Epidemiology and removing duplicates. |

Search was initially performed on March 23, 2011 (n=855 as shown in the table) and was updated on September 25, 2012 (identical search terms, additional n=93 articles identified)

One author (AEN) performed data extraction using an Excel sheet containing categories agreed upon by all authors. Extracted data included general study characteristics (first author, publication year, study years, country, parent study, study type); OA-related characteristics (type of OA assessment, joint sites assessed, criteria for OA diagnosis, risk factors and outcomes considered); population characteristics (number of participants, age range, % female, race/ethnic groups considered, and body mass index); and results (joint sites affected, associations between joints, definitions of GOA, risk factors associated with GOA, and outcomes assessed in GOA). Given the descriptive nature of this review, which spans many years and various study types and does not focus on trials of interventions, no assessment of study quality or risk of bias was performed. Similarly, due to the variety of reported risk factors and outcomes, data were not combined and we did not perform any statistical analyses.

RESULTS

Search and articles

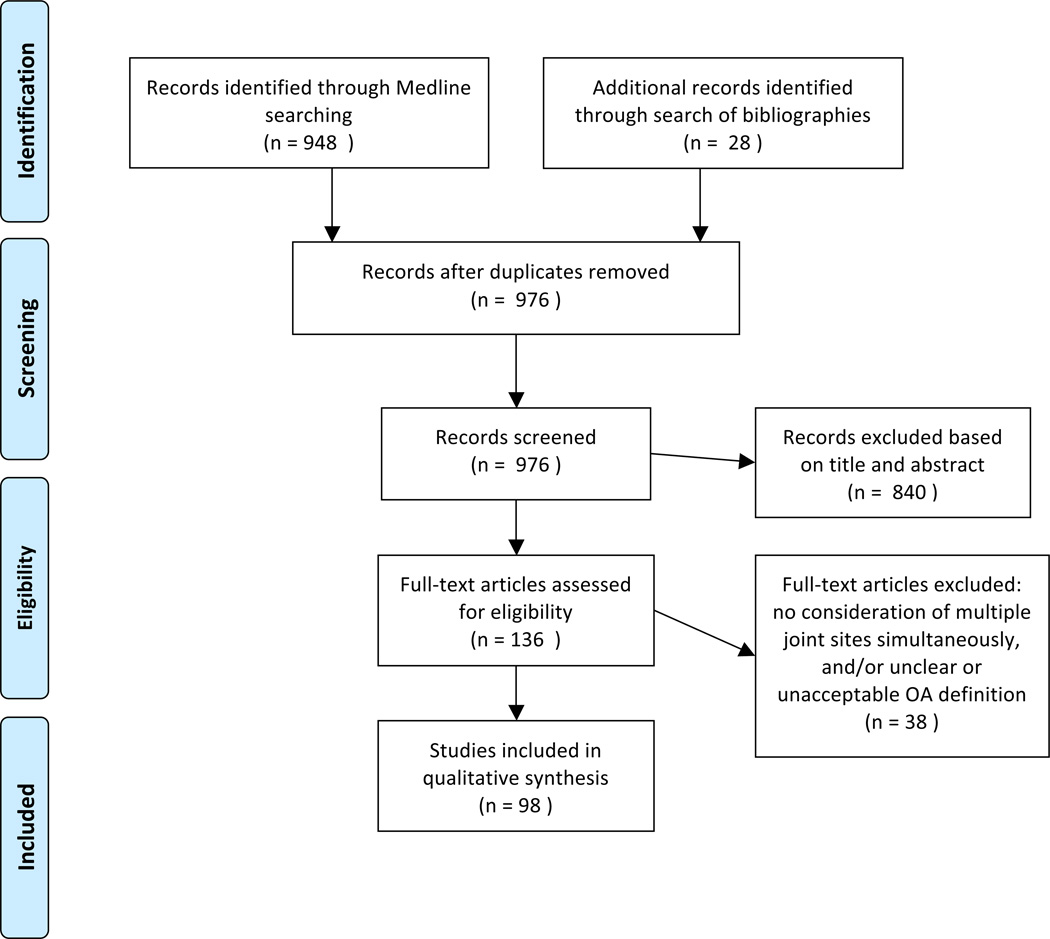

After removal of duplicates, the Medline search resulted in a total of 948 citations (855 on March 23, 2011 [Table 1] and an additional 93 on September 25, 2012 using an identical search strategy). An additional 28 citations were identified through hand searching of bibliographies. Of 976 total articles, 840 were excluded based on title and abstract review, leaving 136 for full-text review. Thirty-eight articles were excluded at this step (agreement was 85%, others were adjudicated) due to either lack of a clear definition of OA or failure to assess more than one joint site, leaving 98 articles for data extraction (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Description of search strategy and article inclusion/exclusion (per PRISMA guidelines)

In the 98 included articles, 24 unique large cohorts were represented (total n=30,223), along with numerous clinical series (total n=9252), across 22 countries, spanning five continents (North America, Europe, Africa, Asia, and Australia), and 60 years (1952–2012, Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of large cohorts represented in selected articles

| # | Cohort | Country | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Leigh and Wensleydale | UK | (4) |

| 2 | New Haven | USA | (23) |

| 3 | U.S. Health Examination Survey | USA | (65) |

| 4 | Spitalfields | UK | (25) |

| 5 | Bristol | UK | (26, 48) |

| 6 | Chingford | UK | (46, 66, 67) |

| 7 | Study of Osteoporotic Fractures | USA | (14) |

| 8 | Radium Dial Painters | USA | (45, 51) |

| 9 | Baltimore Longitudinal Study on Aging | USA | (68) |

| 10 | Ulm | Germany | (27, 39, 60, 61, 69) |

| 11 | Framingham | USA | (30, 53) |

| 12 | TwinsUK | UK | (70, 71) |

| 13 | Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project | USA | (15, 16, 54, 58, 72, 73) |

| 14 | Michigan Bone Health Study/Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation | USA | (22) |

| 15 | Rotterdam | Netherlands | (33, 74) |

| 16 | Clearwater Osteoarthritis Study | USA | (75) |

| 17 | Genetics, Arthrosis, and Progression | Netherlands | (33, 34, 36, 47, 52, 63, 76) |

| 18 | Genetics of Generalized Osteoarthritis | USA | (35) |

| 19 | Ullensaker | Norway | (28, 77) |

| 20 | Prediction of Osteoarthritis Progression | USA | (55) |

| 21 | Genetics of Osteoarthritis and Lifestyle | UK | (78) |

| 22 | Korean Longitudinal Study on Health and Aging | South Korea | (79) |

| 23 | Cohort Hip and Cohort Knee | Netherlands | (80) |

| 24 | Osteoarthritis Initiative | USA | (81) |

Joint sites

The joint sites assessed varied widely but most often included the hands and knees. Radiographic and/or clinical definitions of OA were most often cited, although the radiographic scales varied (Kellgren Lawrence grades were most often used), as did the clinical definitions (the American College of Rheumatology definitions (5–7) were most commonly cited). In some reports, only clinically abnormal or reportedly symptomatic joints underwent radiography, while in others a specified set of joints was examined in all participants. In 30 studies where a definition of GOA was clearly stated, no less than 15 definitions of GOA were given (Table 3). The interphalangeal joints of the hands were essentially always included in GOA definitions, but there appeared to be little agreement as to the appropriateness or necessity of including other joints such as the hip, spine, and feet. Among the 18 studies from the Table explicitly stating which joints were considered, 100% included the hands, 16/18 included knees, 12/18 included hips, and 7/18 assessed spine (any level) or feet.

Table 3.

Synthesis of studies reporting a definition of generalized osteoarthritis

|

Author (year) |

Country | Joint sites considered |

OA criteria |

n | Age range or mean (SD) |

% female |

Joint sites affected |

GOA definition |

Frequency (%) of GOA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kellgren (1952)(3) | UK | Ha, Hi, K, F, LS | C, R | 120 | 35–73 | 92 | 86% nodes, 66% CMC, 52% both, 41% PIP, 42% feet, 53% knee, 30% hips, 48% LS | Required HN and CMC OA in addition to other joints | 52% of OA pts had HN and CMC OA |

| Lawrenc (1969)(4) | UK | Ha, Hi, K, F, CS, LS | C, R | 1179 | 45+ | 54 | 15% of men and 28% of women had HN and 3+ joints with OA; 10% men and 15% women had HN and 5+ joints with OA | Either 3+ or 5+ joint groups where at least one joint has KL grade 2 or more | Non-HN: 3+ joints in 25% men and 20% women; 5+ joints in 9% men and 8% women |

| Solomon (1976)(82) | South Africa | Ha, F (some Hi, LS) | R | 300 | 35+ | 71 | 10% of men and 12% of women had 3+ joint groups, 1% of men and 3% of women had 5+ | HN and 2+ joint groups with rOA | HN and 2+ joints in 1 man and 0 women; non-HN and 2+ joints in 6% men and 9% women |

| Doherty (1983)(24) | UK | Ha, K | C, R | 150 | 36–80 | 15 | Among knees after meniscectomy, 92% had rOA vs. 52% of unoperated knees; those with hand OA had more severe knee OA | 3+ IP joints | 43% |

| Brighton (1985)(83) | South Africa | Ha, F | R | 543 | adult | 72 | DIP most frequent (21–30%), then PIP (11–15%), MTP (3–11%) | 3+ joint groups | 4% |

| Price (1987)(42) | UK | ns | C, R | 40 | 69 (5) | 100 | ns | HN and 6+ joint groups with rOA | 100% (selected GOA) |

| Doherty (1990)(84) | UK | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | HN + polyarticular hand OA (IP and CMC) | ns |

| Waldron (1991)(25) | UK | all | P | 255 | ns | 49 | Most common sites: shoulder (AC, 26–30%), spine (21–24%), hands (18–19%), feet (10–12%), sternoclavicular (6–8%), knee (4–6%), hip (3%); 27% had 3+ joints | DIP, CMC, and knee | 2% |

| Hopkinson (1992)(59) | UK | Ha, Hi, K | C, R | 255 | 45–90 | 90 | ns | HN and symptomatic IP OA in 3+ rays of each hand and clinical and/or radiographic OA at other sites | 34% (selected GOA cases) |

| Hart (1993)(46) | UK | Ha, K | C, R, S | 985 | 54 (6) | 100 | rOA: DIP rOA in 14%, PIP in 4%, CMC 17%, knee 12% | DIP, CMC, and knee rOA | 2% |

| Hordon (1993)(43) | UK | Ha, Hi, K, F, CS, LS, S, A | C, R | 20 | 52–79 | 100 | All had DIP, 65% had PIP, 60% CMC, 75% MTP, 90% knee, 15% hip | 3+ joint groups | 100% (selected GOA) |

| Loughlin (1994)(85) | UK | ns | ns | 133 | ns | ns | ns | HN before age 60 and 3+ other joint groups | 100% of cases (selected for GOA) |

| Cooper (1996)(67) | UK | Ha, Hi, K | R | 702 | 45–64 | 100 | Age 63–64: 54% had DIP, 45% CMC, 20–25% had PIP, hip, or knee | Age and threshold-based: for O:E 1.5 or more, 2+ joint groups needed at age 45–47 but 5+ at age 63–64. | 7% overall for O:E 1.5 |

| Dougados (1996)(86) | France | Ha, Hi, K, F, CS, TS, LS, S, E, others | C, R | 1021 | ns | ns | Most frequent: LS (63–65%), CMC (46%), CS (46%), DIP (45%), Knee (40%) | Either bilateral finger OA or spine and bilateral knee OA | 44% (27% bilat finger, 17% spine and knee) |

| Gunther (1998)(27) | Germany | Hi or K and Ha | TJR, R | 809 | 63 (8) | 62 | Of TJR pts, only 16% had unilateral (signal joint only) findings; 66% had IP, 30% CMC | 2 or more IP joints and one or more CMC in addition to TJR of hip or knee (Ulm definition (39, 60, 61)) | 27% |

| Malaviya (1998)(87) | Kuwait | nd | C, R | 69 | 39–97 | 74 | 94% had knee OA, bilateral in 85%; no pts had hip OA | HN and DIP/PIP OA | 6% |

| Ushiyama (1998)(31) | Japan | Ha, Hi, K | R | 383 | 49–86 | 100 | Of GOA pts, 55% had hip, 82% had knee, 43% had both, 6% had neither | 3+ IP joints | 17% |

| Naito (1999)(57) | Japan | Ha, K | C, R | 102 | 71 (8) | 100 | 100% had knee OA | 3+ IP joints | 45% |

| Huang (2000)(62) | Japan | Ha, Hi, K | R | 270 | 29–87 | 100 | Hand OA (50%), hip (54%), knee (67%), PFJ (62%) | Hand, hip, and knee (hand=3+ IP joints) | 17% |

| Min (2005)(33) | Netherlands | Ha, Hi, K, CS, LS | C, R, S | 1751 | 60–63 (4–8) | 58–82 | 2+ of 4 sites (hand, knee, hip, spine) | 23% Rotterdam and 66% GARP | |

| Miura (2008)(40) | Japan | DIP, K, LS | R | 518 | 24–87 | 72 | Knee (23% men/31% women), LS (68% men/44% women), DIP (16% men/20% women) | Bilateral knee and LS OA | 13% |

| Riyazi (2008)(47) | Netherlands | Ha, Hi, K, CS, LS | R, S | 382 | 40–79 | 64–82 | 57% had hand/spine, 21% hand/knee, 13% hand/hip, 27% knee/spine, 20% hip/spine, 8% hip/knee | Symptomatic OA in 2 or more sites (GARP definition(52, 63)) | 90% had multiple hand joins or 2+ other sites |

| Carroll (2009)(88) | Australia | Ha, Hi, K, F, A, E, wrist | C, R | 67 | 67–71 (9) | 64 | Type I had more CMC OA and more HN | Type I: 2+ DIP or PIP and both knees or both MTP1. Type II: 2+ of MCP2,3 and at least 1 of elbow, wrist, hip, ankle, or tarsometatarsa l (alternate (89)) | 58% type I, 42% type II |

| Hoogeboom (2010)(90) | Netherlands | ns | C, S | 170 | ns | ns | ns | All 3: 1) complaints in 3+ joint groups; 2) 2+ signs of OA in 2+ joints; 3) limited ADLs | ns |

Ha=hand; Hi=hip, K=knee, F=foot, CS=cervical spine, LS=lumbar spine, S=shoulder, A=ankle, E=elbow, HN=Heberden’s nodes, ns=not specified or no data

C=clinical, R=radiographic, P=pathologic

For cohorts using the same definition, only one representative study is included in the table with others referenced along with the definition; 24 listed studies are representative of 30 total studies with a definition

Other studies assessed multiple joint sites but did not propose a GOA definition. Several of these were supportive of GOA as a construct (supporting the constitutional/systemic nature of OA)(8–16), while others were skeptical(17) or found little support for such a construct(18). It is very difficult and potentially misleading to assess prevalence of GOA given the variability of definitions, joint sites and populations (varied by setting, gender, age, race, etc.) assessed. Reported estimates of the frequency of such variably defined GOA ranged from 1–80%, although in most that were not selected for OA status, estimates were in the 5–25% range.

Associated factors

Studies were focused primarily on the patterns of OA involvement, although a variety of risk factors and outcomes were considered in the literature. Most studies were in Caucasian populations, but a few assessed racial differences. Nodal changes and hip OA were infrequent among African descent populations compared with British (19–21). Chinese individuals had a similar frequency of DIP involvement compared to British, but had a low frequency of OA at other joint sites(8). African American women compared with Caucasian women had a higher frequency of MCP and knee OA and their combination (22). In another study, African American men and women were less likely than Caucasians to have hand OA, but more likely to have knee OA(16). That multiple joint OA is more common in women compared with men was confirmed in several studies (4, 16, 23–28).

Increased frequency of GOA or higher risk of GOA progression was associated with age in nearly all studies. Evidence of genetic/familial risk factors was reported (29–36). Some studies reported associations between elevated body mass index and other measures of body mass and multiple joint OA(22, 37, 38), but this finding was not consistent(39, 40). A higher bone mineral density was seen in GOA patients in some series(41), but this association was either equivocal(42, 43), or not seen in other work(44). One study estimated the heritability of GOA at 42%(30). Smoking was noted to be possibly protective for GOA(45–47), but again was not consistently seen across studies(22). Increased OA burden was associated with poorer function and quality of life and increased disability(10, 26, 28, 48, 49).

At least 8 studies from 6 research groups used a summed score to capture OA at multiple sites, generally to allow correlations with systemic markers such as bone mass, cytokines, OA biomarkers or genetic markers. These included summed radiographic grades(44, 50) and sums of numbers of affected joints or joint groups(30, 36, 45, 51–53). Cerhan, et al, reported associations between the number of joints with OA, number of joint groups with OA, and a binary definition of GOA (3 or more joints with K–L grade of 2 or higher) and survival time(51). Joint counts correlated with levels of putative OA biomarkers including urinary type II collagen C-telopeptide (uCTX-II)(52), cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (COMP)(54, 55), YKL 40 (human cartilage glycoprotein 39)(56), matrix metalloproteinase-3 (MMP3)(57), and hyaluronic acid(58) but not with inflammatory markers such as adiponectin, c-reactive protein, or tumor necrosis factor(53, 58).

DISCUSSION

This systematic review provides the first comprehensive summary of the literature to date assessing multiple joint involvement in OA. A detailed search with many synonyms was performed given the lack of standardized terminology in this area. Our hope is that this work will serve as a reference, in order to inform future studies, with the goal of encouraging more research in this area. It seems clear from the results above that a higher burden of OA is associated with poorer outcomes, with the suggestion that multiple joint OA may be a marker of more severe disease that may show increased progression. It is also possible that those with multiple joint OA may benefit more from systemic therapies than would those with single joint/localized OA. However, it is also clear that there is a lack of not only a clear consensus definition for research, but also of a widely understood clinical construct for GOA.

Generally, two groups of similar, although not entirely consistent, definitions emerged: 1) multiple hand joint OA, and 2) hand with large joint OA. Multiple hand joint OA, which was reported mostly in descriptive papers, was defined as 3 or more hand joints, or 3 or more specifically IP joints, with or without Heberden nodes, and in some definitions, bilateral distribution was required. Hand with large joint (knee and/or hip) OA usually included DIP or CMC joints with knee or hip joints. In the first group (multiple hand joints), Doherty et al describe greater frequency and severity of radiographic and symptomatic knee OA in patients 19 years or more after unilateral meniscectomy among patients with concomitant polyarticular hand OA versus those without, independent of sex and age, and for both operated and unoperated knees (24). Another group assessed nodal GOA (nodes + at least 3 IP joints) in comparison with large joint OA (hip or knee) or controls and found more frequent immunoglobulin (Ig) G rheumatoid factor positivity among nodal GOA (51%) versus large joint OA (17%) or controls (11%, p<0.0001), with no differences for IgA or IgM rheumatoid factor positivity (59). Nodal GOA patients more frequently had low IgA levels (23%) compared to those with large joint OA (14%) or controls (6%) (59). Associations have also been reported between multiple joint hand GOA and estrogen receptor genotype (31) and elevated MMP-3 levels (57).

The second group, utilizing a definition of GOA that includes hand and large joint OA, includes several studies from the Ulm and GARP cohorts. The Ulm study included individuals scheduled for unilateral hip (n=420) or knee (n=389) joint replacement, and defined GOA as OA involvement in at least 1 CMC joint, at least 2 IP joints (DIP or PIP) in addition to the involved hip or knee (27). Eighty-two percent of hip and 87% of knee patients had involvement of the contralateral joint, and 27% had GOA. GOA was more frequent in knee OA patients (35%) compared with hip OA patients (19%) but the prevalence was similar in these two groups after accounting for age and sex variation. GOA was about twice as common in women compared to men, and was more frequent with increasing age (27). Other analyses using this cohort have found that overweight (27%) or obese (29%) individuals were more likely to have GOA compared with normal weight (24%, although not statistically significant) (39); those in the highest tertile of serum uric acid were more likely to have GOA in the hip group (adjusted OR [aOR] 3.5, 95% CI [1.3–9.1]) but not in the knee group (aOR 1.2, 95% CI [0.6–2.4]) (60); and among women, those status post hysterectomy were less likely to have GOA (aOR 0.6 [95% CI 0.34–0.99]), again more markedly in the hip group (aOR 0.34, 95% CI [0.12–0.97]) versus the knee group (aOR 0.63, 95% CI [0.32–1.23]) (61). Other groups using a similar definition have found a possible protective effect of smoking for GOA (46) and no association with vitamin D receptor phenotype (62). Interestingly, in a post-mortem skeletal study, Waldron et al defined GOA in the same way, but also found that all individuals meeting those criteria also had shoulder OA (25).

The GARP study defined GOA as radiographic involvement of multiple hand joints or 2 of 4 total sites (of hands, cervical or lumbar spine, knee, and hip) with at least one symptomatic site. GOA was positively associated with being married versus unmarried (aOR 2.0, 95% CI [1.3–3.3]), having had menopause before age 45 years versus age 45–52 years (aOR 2.6, 95% CI [1.5–4.5]), with hysterectomy and ovariectomy (aOR 1.5–1.8), and with overweight and obesity (aOR 1.9–2.1) (47). GOA was negatively associated with smoking (aOR 0.7, 95% CI [0.4–1.0]) and was less prevalent in those over 180cm versus under 160cm in height (47). Physically demanding jobs were associated with GOA among men only (for men aOR 2.5 95% CI [1.2–5.3]; for women aOR 1.3, 95% CI [0.6–2.8]) (47). Each of the joint areas studied in GARP, with the exception of disc degeneration, contributed to higher levels of uCTX-II, and a significant association was found between uCTX-II levels and a composite summed score of radiographic OA at multiple sites (estimate 0.06, 95% CI [0.04–0.07]) (52). Kornaat et al used data from the first 42 GARP patients along with 27 age and sex matched controls and found that GOA patients had higher popliteal vessel wall thickness compared to controls, suggesting an association between GOA and the metabolic syndrome (63). Min et al used data from GARP and a similar GOA definition in the Rotterdam study to assess genetic associations with the frizzled-related protein gene (part of the Wnt pathway), finding that the G allele of the R324G variant was more common in GOA in both populations (aOR 1.4 to 1.6) (33).

Overall, the studies included in this review have several limitations as a group, including vague definitions of GOA or related constructs. It was often unclear exactly which joints or joint groups were considered in a given study, and whether these were the same for all participants; some studies assessed only symptomatic joints which varied among individuals. Variation in assessed joints across studies, even when specified, makes comparison of risk factors and outcomes difficult. In some cases, misclassification bias due to differential assessment in cases and controls was a concern. Several studies were of radiographic OA alone, without consideration of symptomatic or clinical factors. Study participants were often recruited based on pain in a signal joint, such that the generalizability to other groups or the general population was uncertain.

The strengths of this systematic review include our use of a professional research librarian, adherence to the PRISMA guidelines, and dual independent reviews of both abstracts and full text articles with adjudication. We were admittedly limited by the lack of appropriate medical subject heading (MeSH) terms and the disparate terminology in the literature on this topic, and in part because of this we were unable to perform any statistical or meta-analysis.

Future research should focus on defining phenotypes of multiple joint involvement of OA to determine if more homogeneous groups may exist. Such phenotypes, if identified, could be used as outcomes for studies of systemic risk factors such as genetics and biomarkers, and possibly in clinical trials particularly of systemic therapies. Focused trials in well-defined subgroups thought to be at higher risk for incidence or progression of OA could result in shorter, less expensive trials of promising OA treatments (both pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic). It will also be important for future trials in OA to account for symptoms in multiple joints, even if a signal joint is the therapeutic focus, since benefit or harm could potentially be observed at distant joint sites (e.g. the adverse events observed in shoulder, ankle, and foot for patients enrolled in tanezumab studies for hip and knee OA (64)).

CONCLUSION

We feel, based on the lack of clear definitions identified in this study, that the term GOA should be discarded in favor of more specific and understandable terms, such as multiple joint or polyarticular OA, which must be accompanied in every case by an unambiguous statement as to the joints considered and the construct being used. Further study is needed to determine appropriate phenotypes for clinical and research use.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill: Christiane Voisin, MSLS, for her assistance with the literature search, and Tim Carey, MD, MPH for guidance at the inception of the project and helpful comments on the abstract and manuscript.

ROLE OF FUNDING SOURCE: The funding sources had no role in study design, data collection/analysis, interpretation of data, manuscript writing, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Funding for this work provided in part by: NIAMS K23 AR061406 and a Rheumatology Research

Foundation Clinical Investigator Fellowship Award (Nelson), National Center for Advancing

Translational Sciences/ National Institutes of Health (NIH), through Grant KL2TR000084 and Arthritis

Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship Award (Golightly), Rheumatology Research Foundation Fellowship

Training Award (Smith)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

COMPETING INTERESTS: The authors declare no competing interest in relation to this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams R. A treatise on rheumatic gout, or chronic rheumatic arthritis of all the joints. London: John Churchill and Sons; 1857. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cecil RL, Archer BH. Classification and treatment of chronic arthritis. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 1926;87(10):741–746. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kellgren JH, Moore R. Generalized osteoarthritis and Heberden's nodes. British medical journal. 1952;1(4751):181–187. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.4751.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lawrence JS. Generalized osteoarthrosis in a population sample. Am J Epidemiol. 1969;90(5):381–389. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a121083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Altman R, Alarcon G, Appelrouth D, Bloch D, Borenstein D, Brandt K, et al. The American College of Rheumatology criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis of the hip. Arthritis Rheum. 1991;34(5):505–514. doi: 10.1002/art.1780340502. Epub 1991/05/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Altman R, Alarcon G, Appelrouth D, Bloch D, Borenstein D, Brandt K, et al. The American College of Rheumatology criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis of the hand. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33(11):1601–1610. doi: 10.1002/art.1780331101. Epub 1990/11/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Altman R, Asch E, Bloch D, Bole G, Borenstein D, Brandt K, et al. Development of criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis. Classification of osteoarthritis of the knee. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee of the American Rheumatism Association. Arthritis Rheum. 1986;29(8):1039–1049. doi: 10.1002/art.1780290816. Epub 1986/08/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoaglund FT, Yau AC, Wong WL. Osteoarthritis of the hip and other joints in southern Chinese in Hong Kong. The Journal of bone and joint surgery American volume. 1973;55(3):545–557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roh YS, Dequeker J, Mulier JC. Osteoarthrosis at the hand skeleton in primary osteoarthrosis of the hip and in normal controls. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1973;(90):90–94. (90) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Massardo L, Watt I, Cushnaghan J, Dieppe P. Osteoarthritis of the knee joint: an eight year prospective study. Ann Rheum Dis. 1989;48(11):893–897. doi: 10.1136/ard.48.11.893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doherty M, Preston B. Primary osteoarthritis of the elbow. Ann Rheum Dis. 1989;48(9):743–747. doi: 10.1136/ard.48.9.743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Croft P, Cooper C, Wickham C, Coggon D. Is the hip involved in generalized osteoarthritis? Br J Rheumatol. 1992;31(5):325–328. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/31.5.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris PA, Hart DJ, Dacre JE, Huskisson EC, Spector TD. The progression of radiological hand osteoarthritis over ten years: a clinical follow-up study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 1994;2(4):247–252. doi: 10.1016/s1063-4584(05)80076-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hochberg MC, Lane NE, Pressman AR, Genant HK, Scott JC, Nevitt MC. The association of radiographic changes of osteoarthritis of the hand and hip in elderly women. J Rheumatol. 1995;22(12):2291–2294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sayre EC, Jordan JM, Cibere J, Murphy L, Schwartz TA, Helmick CG, et al. Quantifying the association of radiographic osteoarthritis in knee or hip joints with other knees or hips: the Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project. J Rheumatol. 2010;37(6):1260–1265. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.091154. Epub 2010/04/17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nelson AE, Renner JB, Schwartz TA, Kraus VB, Helmick CG, Jordan JM. Differences in multijoint radiographic osteoarthritis phenotypes among African Americans and Caucasians: The Johnston County Osteoarthritis project. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(12):3843–3852. doi: 10.1002/art.30610. Epub 2011/10/25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vignon E. Hand osteoarthritis and generalized osteoarthritis: a need for clarification. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2000;8(Suppl A):S22–S24. doi: 10.1053/joca.2000.0331. (Journal Article) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacGregor AJ, Li Q, Spector TD, Williams FM. The genetic influence on radiographic osteoarthritis is site specific at the hand, hip and knee. Rheumatology (Oxford, England) 2009;48(3):277–280. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bremner JM, Lawrence JS, Miall WE. Degenerative joint disease in a Jamaican rural population. Ann Rheum Dis. 1968;27(4):326–332. doi: 10.1136/ard.27.4.326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Solomon L, Beighton P, Lawrence JS. Rheumatic disorders in the South African Negro. Part II. Osteo-arthrosis. South African medical journal = Suid-Afrikaanse tydskrif vir geneeskunde. 1975;49(42):1737–1740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adebajo AO. Pattern of osteoarthritis in a West African teaching hospital. Ann Rheum Dis. 1991;50(1):20–22. doi: 10.1136/ard.50.1.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sowers M, Lachance L, Hochberg M, Jamadar D. Radiographically defined osteoarthritis of the hand and knee in young and middle-aged African American and Caucasian women. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2000;8(2):69–77. doi: 10.1053/joca.1999.0273. Epub 2000/04/20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Acheson RM, Collart AB. New Haven survey of joint diseases. XVII. Relationship between some systemic characteristics and osteoarthrosis in a general population. Ann Rheum Dis. 1975;34(5):379–387. doi: 10.1136/ard.34.5.379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Doherty M, Watt I, Dieppe P. Influence of primary generalised osteoarthritis on development of secondary osteoarthritis. Lancet. 1983;2(8340):8–11. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)90003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Waldron HA. Prevalence and distribution of osteoarthritis in a population from Georgian and early Victorian London. Ann Rheum Dis. 1991;50(5):301–307. doi: 10.1136/ard.50.5.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cushnaghan J, Dieppe P. Study of 500 patients with limb joint osteoarthritis. I. Analysis by age, sex, and distribution of symptomatic joint sites. Ann Rheum Dis. 1991;50(1):8–13. doi: 10.1136/ard.50.1.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gunther KP, Sturmer T, Sauerland S, Zeissig I, Sun Y, Kessler S, et al. Prevalence of generalised osteoarthritis in patients with advanced hip and knee osteoarthritis: the Ulm Osteoarthritis Study. Ann Rheum Dis. 1998;57(12):717–723. doi: 10.1136/ard.57.12.717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grotle M, Hagen KB, Natvig B, Dahl FA, Kvien TK. Prevalence and burden of osteoarthritis: results from a population survey in Norway. J Rheumatol. 2008;35(4):677–684. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spector TD, Cicuttini F, Baker J, Loughlin J, Hart D. Genetic influences on osteoarthritis in women: a twin study. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 1996;312(7036):940–943. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7036.940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Felson DT, Couropmitree NN, Chaisson CE, Hannan MT, Zhang Y, McAlindon TE, et al. Evidence for a Mendelian gene in a segregation analysis of generalized radiographic osteoarthritis: the Framingham Study. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41(6):1064–1071. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199806)41:6<1064::AID-ART13>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ushiyama T, Ueyama H, Inoue K, Nishioka J, Ohkubo I, Hukuda S. Estrogen receptor gene polymorphism and generalized osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol. 1998;25(1):134–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Okma-Keulen P, Hopman-Rock M. The onset of generalized osteoarthritis in older women: a qualitative approach. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;45(2):183–190. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200104)45:2<183::AID-ANR172>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Min JL, Meulenbelt I, Riyazi N, Kloppenburg M, Houwing-Duistermaat JJ, Seymour AB, et al. Association of the Frizzled-related protein gene with symptomatic osteoarthritis at multiple sites. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(4):1077–1080. doi: 10.1002/art.20993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Botha-Scheepers SA, Watt I, Slagboom E, Meulenbelt I, Rosendaal FR, Breedveld FC, et al. Influence of familial factors on radiologic disease progression over two years in siblings with osteoarthritis at multiple sites: a prospective longitudinal cohort study. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(4):626–632. doi: 10.1002/art.22680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kraus VB, Jordan JM, Doherty M, Wilson AG, Moskowitz R, Hochberg M, et al. The Genetics of Generalized Osteoarthritis (GOGO) study: study design and evaluation of osteoarthritis phenotypes. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007;15(2):120–127. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2006.10.002. Epub 2006/11/23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meulenbelt I, Bos SD, Kloppenburg M, Lakenberg N, Houwing-Duistermaat JJ, Watt I, et al. Interleukin-1 gene cluster variants with innate cytokine production profiles and osteoarthritis in subjects from the Genetics, Osteoarthritis and Progression Study. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(4):1119–1126. doi: 10.1002/art.27325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dequeker J, Goris P, Uytterhoeven R. Osteoporosis and osteoarthritis (osteoarthrosis). Anthropometric distinctions. JAMA. 1983;249(11):1448–1451. Epub 1983/03/18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spector TD, Campion GD. Generalised osteoarthritis: a hormonally mediated disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 1989;48(6):523–527. doi: 10.1136/ard.48.6.523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sturmer T, Gunther KP, Brenner H. Obesity, overweight and patterns of osteoarthritis: the Ulm Osteoarthritis Study. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2000;53(3):307–313. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00162-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miura H, Kawano T, Takasugi S, Manabe T, Hosokawa A, Iwamoto Y. Two subtypes of radiographic osteoarthritis in the distal interphalangeal joint of the hand. Journal of orthopaedic science : official journal of the Japanese Orthopaedic Association. 2008;13(6):487–491. doi: 10.1007/s00776-008-1270-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Belmonte-Serrano MA, Bloch DA, Lane NE, Michel BE, Fries JF. The relationship between spinal and peripheral osteoarthritis and bone density measurements. J Rheumatol. 1993;20(6):1005–1013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Price T, Hesp R, Mitchell R. Bone density in generalized osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol. 1987;14(3):560–562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hordon LD, Stewart SP, Troughton PR, Wright V, Horsman A, Smith MA. Primary generalized osteoarthritis and bone mass. Br J Rheumatol. 1993;32(12):1059–1061. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/32.12.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reid DM, Kennedy NS, Smith MA, Tothill P, Nuki G. Bone mass in nodal primary generalised osteoarthrosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1984;43(2):240–242. doi: 10.1136/ard.43.2.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cerhan JR, Wallace RB, el-Khoury GY, Moore TE. Risk factors for progression to new sites of radiographically defined osteoarthritis in women. J Rheumatol. 1996;23(9):1565–1578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hart DJ, Spector TD. Cigarette smoking and risk of osteoarthritis in women in the general population: the Chingford study. Ann Rheum Dis. 1993;52(2):93–96. doi: 10.1136/ard.52.2.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Riyazi N, Rosendaal FR, Slagboom E, Kroon HM, Breedveld FC, Kloppenburg M. Risk factors in familial osteoarthritis: the GARP sibling study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2008;16(6):654–659. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2007.10.012. Epub 2008/01/30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dieppe P, Cushnaghan J, Tucker M, Browning S, Shepstone L. The Bristol 'OA500 study': progression and impact of the disease after 8 years. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2000;8(2):63–68. doi: 10.1053/joca.1999.0272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kwok WY, Vliet Vlieland TP, Rosendaal FR, Huizinga TW, Kloppenburg M. Limitations in daily activities are the major determinant of reduced health-related quality of life in patients with hand osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(2):334–336. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.133603. Epub 2010/11/18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cooke TD. Immune pathology in polyarticular osteoarthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1986;(213):41–49. (213) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cerhan JR, Wallace RB, el-Khoury GY, Moore TE, Long CR. Decreased survival with increasing prevalence of full-body, radiographically defined osteoarthritis in women. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;141(3):225–234. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117424. Epub 1995/02/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Meulenbelt I, Kloppenburg M, Kroon HM, Houwing-Duistermaat JJ, Garnero P, Hellio Le Graverand MP, et al. Urinary CTX-II levels are associated with radiographic subtypes of osteoarthritis in hip, knee, hand, and facet joints in subject with familial osteoarthritis at multiple sites: the GARP study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65(3):360–365. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.040642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vlad SC, Neogi T, Aliabadi P, Fontes JD, Felson DT. No association between markers of inflammation and osteoarthritis of the hands and knees. J Rheumatol. 2011;38(8):1665–1670. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.100971. Epub 2011/05/17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jordan JM, Luta G, Stabler T, Renner JB, Dragomir AD, Vilim V, et al. Ethnic and sex differences in serum levels of cartilage oligomeric matrix protein: the Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(3):675–681. doi: 10.1002/art.10822. Epub 2003/03/13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Addison S, Coleman RE, Feng S, McDaniel G, Kraus VB. Whole-body bone scintigraphy provides a measure of the total-body burden of osteoarthritis for the purpose of systemic biomarker validation. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(11):3366–3373. doi: 10.1002/art.24856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Abe M, Takahashi M, Naitou K, Ohmura K, Nagano A. Investigation of generalized osteoarthritis by combining X-ray grading of the knee, spine and hand using biochemical markers for arthritis in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2003;22(6):425–431. doi: 10.1007/s10067-003-0802-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Naito K, Takahashi M, Kushida K, Suzuki M, Ohishi T, Miura M, et al. Measurement of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 (TIMP-1) in patients with knee osteoarthritis: comparison with generalized osteoarthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford, England) 1999;38(6):510–515. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/38.6.510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Elliott AL, Kraus VB, Luta G, Stabler T, Renner JB, Woodard J, et al. Serum hyaluronan levels and radiographic knee and hip osteoarthritis in African Americans and Caucasians in the Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(1):105–111. doi: 10.1002/art.20724. Epub 2005/01/11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hopkinson ND, Powell RJ, Doherty M. Autoantibodies, immunoglobulins and Gm allotypes in nodal generalized osteoarthritis. Br J Rheumatol. 1992;31(9):605–608. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/31.9.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sun Y, Brenner H, Sauerland S, Gunther KP, Puhl W, Sturmer T. Serum uric acid and patterns of radiographic osteoarthritis--the Ulm Osteoarthritis Study. Scand J Rheumatol. 2000;29(6):380–386. doi: 10.1080/030097400447589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stove J, Sturmer T, Kessler S, Brenner H, Puhl W, Gunther KP. Hysterectomy and patterns of osteoarthritis. The Ulm Osteoarthritis Study. Scand J Rheumatol. 2001;30(6):340–345. doi: 10.1080/030097401317148534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Huang J, Ushiyama T, Inoue K, Kawasaki T, Hukuda S. Vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms and osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, knee: acase-control study in Japan. Rheumatology (Oxford, England) 2000;39(1):79–84. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/39.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kornaat PR, Sharma R, van der Geest RJ, Lamb HJ, Kloppenburg M, Hellio le Graverand MP, et al. Positive association between increased popliteal artery vessel wall thickness and generalized osteoarthritis: is OA also part of the metabolic syndrome? Skeletal Radiol. 2009;38(12):1147–1151. doi: 10.1007/s00256-009-0741-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tanezumab FDA. Arthritis Advisory Committee Briefing Document. 2012 Available from: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/Drugs/ArthritisAdvisoryCommittee/UCM295205.pdf.

- 65.Davis MA, Neuhaus JM, Ettinger WH, Mueller WH. Body fat distribution and osteoarthritis. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;132(4):701–707. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hart D, Spector T, Egger P, Coggon D, Cooper C. Defining osteoarthritis of the hand for epidemiological studies: the Chingford Study. Ann Rheum Dis. 1994;53(4):220–223. doi: 10.1136/ard.53.4.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cooper C, Egger P, Coggon D, Hart DJ, Masud T, Cicuttini F, et al. Generalized osteoarthritis in women: pattern of joint involvement and approaches to definition for epidemiological studies. J Rheumatol. 1996;23(11):1938–1942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hirsch R, Lethbridge-Cejku M, Scott WW, Jr, Reichle R, Plato CC, Tobin J, et al. Association of hand and knee osteoarthritis: evidence for a polyarticular disease subset. Ann Rheum Dis. 1996;55(1):25–29. doi: 10.1136/ard.55.1.25. Epub 1996/01/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kessler S, Stove J, Puhl W, Sturmer T. First carpometacarpal and interphalangeal osteoarthritis of the hand in patients with advanced hip or knee OA. Are there differences in the aetiology? Clin Rheumatol. 2003;22(6):409–413. doi: 10.1007/s10067-003-0783-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cicuttini FM, Baker J, Hart DJ, Spector TD. Relation between Heberden's nodes and distal interphalangeal joint osteophytes and their role as markers of generalised disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 1998;57(4):246–248. doi: 10.1136/ard.57.4.246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.MacGregor AJ, Li Q, Spector TD, Williams FM. The genetic influence on radiographic osteoarthritis is site specific at the hand, hip and knee. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009;48(3):277–280. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken475. Epub 2009/01/21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Clark AG, Jordan JM, Vilim V, Renner JB, Dragomir AD, Luta G, et al. Serum cartilage oligomeric matrix protein reflects osteoarthritis presence and severity: the Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42(11):2356–2364. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199911)42:11<2356::AID-ANR14>3.0.CO;2-R. Epub 1999/11/11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Allen KD, Helmick CG, Schwartz TA, DeVellis RF, Renner JB, Jordan JM. Racial differences in self-reported pain and function among individuals with radiographic hip and knee osteoarthritis: the Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2009;17(9):1132–1136. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2009.03.003. Epub 2009/03/31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dahaghin S, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, Reijman M, Pols HA, Hazes JM, Koes BW. Does hand osteoarthritis predict future hip or knee osteoarthritis? Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(11):3520–3527. doi: 10.1002/art.21375. Epub 2005/10/29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wilder FV, Barrett JP, Farina EJ. The association of radiographic foot osteoarthritis and radiographic osteoarthritis at other sites. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2005;13(3):211–215. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2004.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bos SD, Kloppenburg M, Suchiman E, van Beelen E, Slagboom PE, Meulenbelt I. The role of plasma cytokine levels, CRP and Selenoprotein S gene variation in OA. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2009;17(5):621–626. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2008.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Grotle M, Hagen KB, Natvig B, Dahl FA, Kvien TK. Obesity and osteoarthritis in knee, hip and/or hand: an epidemiological study in the general population with 10 years follow-up. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9:132. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-9-132. (Journal Article) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.McWilliams DF, Doherty S, Maciewicz RA, Muir KR, Zhang W, Doherty M. Self-reported knee and foot alignments in early adult life and risk of osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2010;62(4):489–495. doi: 10.1002/acr.20169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Oh JH, Chung SW, Oh CH, Kim SH, Park SJ, Kim KW, et al. The prevalence of shoulder osteoarthritis in the elderly Korean population: association with risk factors and function. Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery / American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons [et al] 2011;20(5):756–763. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2011.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kinds MB, Vincken KL, Vignon EP, ten Wolde S, Bijlsma JW, Welsing PM, et al. Radiographic features of knee and hip osteoarthritis represent characteristics of an individual, in addition to severity of osteoarthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2012;41(2):141–149. doi: 10.3109/03009742.2011.617311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Haugen IK, Cotofana S, Englund M, Kvien TK, Dreher D, Nevitt M, et al. Hand joint space narrowing and osteophytes are associated with magnetic resonance imaging-defined knee cartilage thickness and radiographic knee osteoarthritis: data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. J Rheumatol. 2012;39(1):161–166. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.110603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Solomon L, Beighton P, Lawrence JS. Osteoarthrosis in a rural South African Negro population. Ann Rheum Dis. 1976;35(3):274–278. doi: 10.1136/ard.35.3.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Brighton SW, de la Harpe AL, Van Staden DA. The prevalence of osteoarthrosis in a rural African community. Br J Rheumatol. 1985;24(4):321–325. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/24.4.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Doherty M, Pattrick M, Powell R. Nodal generalised osteoarthritis is an autoimmune disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 1990;49(12):1017–1020. doi: 10.1136/ard.49.12.1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Loughlin J, Irven C, Fergusson C, Sykes B. Sibling pair analysis shows no linkage of generalized osteoarthritis to the loci encoding type II collagen, cartilage link protein or cartilage matrix protein. Br J Rheumatol. 1994;33(12):1103–1106. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/33.12.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Dougados M, Nakache JP, Gueguen A. Criteria for generalized and focal osteoarthritis. Revue du rhumatisme (English ed) 1996;63(9):569–575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Malaviya AN, Shehab D, Bhargava S, Al-Jarallah K, Al-Awadi A, Sharma PN, et al. Characteristics of osteoarthritis among Kuwaitis: a hospital-based study. Clin Rheumatol. 1998;17(3):210–213. doi: 10.1007/BF01451049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Carroll GJ, Breidahl WH, Jazayeri J. Confirmation of two major polyarticular osteoarthritis (POA) phenotypes--differentiation on the basis of joint topography. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2009;17(7):891–895. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Carroll GJ. Primary osteoarthritis in the ankle joint is associated with finger metacarpophalangeal osteoarthritis and the H63D mutation in the HFE gene: evidence for a hemochromatosis-like polyarticular osteoarthritis phenotype. J Clin Rheumatol. 2006;12(3):109–113. doi: 10.1097/01.rhu.0000221800.77223.d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hoogeboom TJ, Stukstette MJ, de Bie RA, Cornelissen J, den Broeder AA, van den Ende CH. Non-pharmacological care for patients with generalized osteoarthritis: design of a randomized clinical trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010;11:142. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-11-142. (Journal Article) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]