Abstract

Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) is the major biological cofactor contributing to development of Kaposi’s sarcoma. KSHV establishes a latent infection in human B cells expressing the latency-associated nuclear antigen (LANA), a critical factor in the regulation of viral latency. LANA is known to modulate viral and cellular gene expression. We report here on some initial proteomic studies to identify of cellular proteins associated with the amino and carboxy terminal domains of LANA. The results of these studies show an association of known cellular proteins which support LANA functions and have identified additional LANA associated proteins. These results provide new evidence for complexes involving LANA with a number of previously unreported functional classes of proteins including DNA polymerase, RNA helicase and cell cycle control proteins. The results also indicate that the amino terminus of LANA can interact with its carboxy terminal domain. This interaction is potentially important for facilitating associations with other cell cycle regulatory proteins which include CENP-F identified in association with both the amino and carboxy termini. These novel associations add to the diversity of LANA functions in relation to the maintenance of latency and subsequent transformation of KSHV infected cells.

Keywords: Proteomics, Latency associated nuclear antigen, KSHV

Introduction

Approximately 15% of cancers (about 1.5 million cases per year, worldwide) have been attributed to viral (11%), bacterial (4%), and other pathogens (0.1%) (Gencer, Salepci, and Ozer, 2003; O’Brien et al., 2003; Rosenblatt et al., 2003; Somech et al., 2003). Infectious agents that cause cancer are also known to persist for long periods in the host. How the host responds to the infectious agents and how the agent modulates this response is critical in allowing for its persistence, and may determine the risk of cancer (Srivastava, Verma, and Gopal-Srivastava, 2005). In addition, oncogenic viruses in many cases have learned to evade the immune system and such evasion strategies likely contribute to their oncogenic potential. Therefore, the immunobiology of persistent infections and in particular those that lead to cancer must be better understood (Srivastava, Verma, and Gopal-Srivastava, 2005). Studying viral-host protein interaction in infected cells can provide new information on these various strategies. The application of proteomics technology to identify cellular proteins that can interact with viral antigens in the infected host during latency, can lead us to explore the specific viral-host protein interactions which contribute to oncogenesis.

Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV), also known as human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8), has been linked to several malignancies in humans (Cesarman et al., 1995a). KSHV is the etiologic agent associated with development of Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS), primary effusion lymphoma (PEL), and multicentric Castleman’s disease (MCD) (Moore and Chang, 2003). KSHV is a double-stranded DNA virus classified as a gammaherpesvirus also called human herpesvirus type 8 (HHV-8) and is the only known human γ2-herpesvirus (Rhadinovirus) and the most recently discovered human tumor virus (Chang et al., 1994). Like other members of the herpesvirus family, KSHV/HHV-8 tightly regulates expression of its genes. These genes can be divided in two groups: those involved in latent infection, which facilitate persistence of the viral genome; and those involved in lytic infection, which ultimately leads to host cell destruction and release of new viruses. The viral proteins expressed shown to be associated with latent infection include the latency associated nuclear antigen (LANA1; ORF 73), viral cyclin (ORF 72), and viral Fas associated death domain-like interleukin 1 gamma-converting enzyme inhibitory protein (vFLIP; ORF 71), Kaposin A, vIRF1 and LANA2 (Dourmishev et al., 2003).

LANA1 (also commonly referred to as LANA) is a large nuclear antigen detected in the majority of KS lesions as well as in cell lines derived from BCBLs (Cesarman et al., 1995a). LANA has a number of functions related to the transcription and replication of viral episomal DNA, and anchors the circular viral DNA to the host chromatin during interphase and mitosis. LANA is critical to the persistence of KSHV episomes and functions in this capacity by tethering viral episomes to chromosomes during mitosis, which allows for efficient segregation of viral episomes to daughter cells (Ballestas, Chatis, and Kaye, 1999; Cotter and Robertson, 1999b; Lan, Kuppers, and Robertson, 2005; Lan et al., 2004). In addition, LANA physically interacts with cellular proteins, including p53 (Friborg et al., 1999), pRB (Radkov, Kellam, and Boshoff, 2000), RING3 (Platt et al., 1999), histone H1 (Cotter and Robertson, 1999b; Lan, Kuppers, and Robertson, 2005; Lan et al., 2004), ATF4/CREB2 (Lim et al., 2000), EC5S Ubiquitin Complex (Cai et al., 2006b) and members of the mSin3 corepressor complex (Krithivas et al., 2000). Functional consequences of these interactions include inhibition of p53-mediated apoptosis (Borah, Verma, and Robertson, 2004; Friborg et al., 1999), inhibition of the transcriptional activity of ATF4/CREB2 (Lim et al., 2000), dysregulation of β-catenin and the Wnt signaling pathway (Fujimuro et al., 2003), regulation of HIF-1α by inducing ubiquitination and degradation of VHL and p53 (Cai et al., 2006a), degradation of the VHL and p53 tumor suppressors by recruiting the EC5S ubiquitin complex (Cai et al., 2006b), and in conjunction with Hras, transformation of primary rat embryonic fibroblasts (Radkov, Kellam, and Boshoff, 2000).

The secondary structure of LANA suggests that there are potential sites for interactions with other cellular factors involved in transcription (Verma, Lan, and Robertson, 2007). Its amino acid sequence indicates that it has an acidic-rich, a proline-rich and a glutamine-rich domain, a zinc finger DNA binding domain, a leucine zipper and a potential nuclear localization signal (Verma, Lan, and Robertson, 2007). LANA can also repress transcription when fused to the GAL4 DNA binding domain, tested on a GAL4 responsive promoter (Verma, Borah, and Robertson, 2004). LANA tethers the viral genome through binding to the 13-bp LANA binding sequence (LBS) in the terminal repeats (TRs) which were identified by overlapping probes (Cotter, Subramanian, and Robertson, 2001). During long-term persistence viral DNA replicates in a synchronized fashion and segregates to the daughter cells in a non-random fashion (Verma et al., 2006). LANA binds to the LANA binding sequence (LBS) through its carboxy-terminal DNA binding domain (Verma et al., 2006). The amino terminus is important for tethering to the nucleosomes, in particular interactions with the histones including histone H1, and probably with other cellular proteins, which includes MeCP2 and DEK (Barbera et al., 2006a; Cotter and Robertson, 1999b; Krithivas et al., 2002; Shinohara et al., 2002). Therefore, LANA appears to be a multifunctional protein involved in modulating activation and repression of transcription. Thus, these activities are likely to be important for regulation of cell proliferation and apoptosis in KSHV-infected cells.

To obtain a more comprehensive view of the critical role for LANA in maintenance of KSHV latency, a list of all cellular proteins associated with LANA was generated experimentally through proteomic studies. These results will provide new insights into the breadth of potential functions linked to LANA at the molecular level. These include viral genome maintenance during latency and contribution to cell proliferation and KSHV associated pathogenesis. This is a first step in understanding the complexities of interaction between host cellular proteins and LANA. Once specific proteins are identified, characterization of novel LANA functions will be pursued as the biochemical role of many of the identified proteins in context of virus infection and latency remain to be explored. The overall goal of this present study was to obtain a comprehensive list of cellular proteins capable of associating with LANA. GST-pull down assays were used to fractionate protein complexes that interact specifically with the amino as well as the carboxy terminal domains of LANA followed by MALDI-TOF analysis to identity LANA interacting proteins.

Results & Discussion

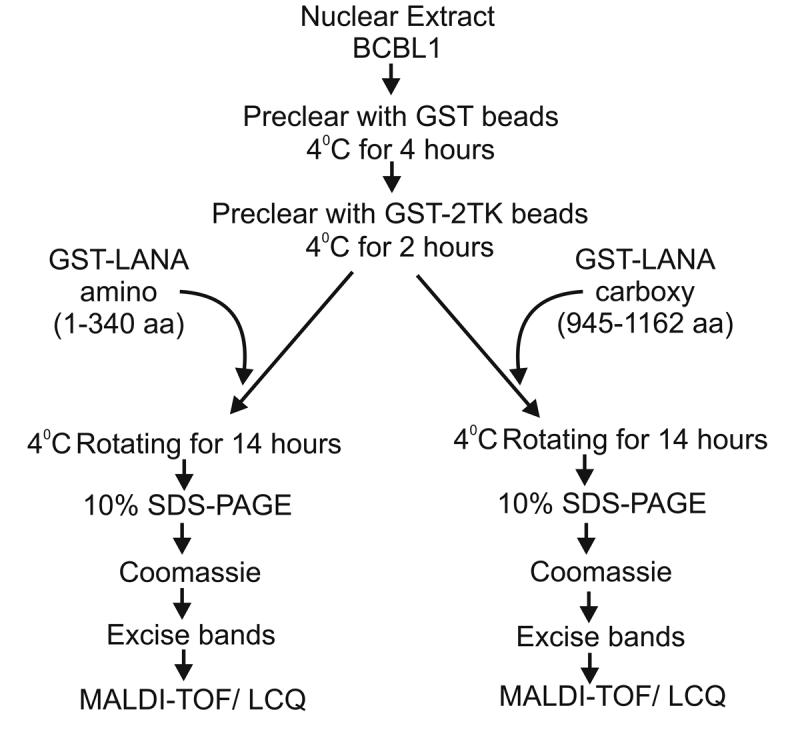

To determine the identity of cellular proteins interacting with LANA we performed pull-down assays with nuclear extracts from KSHV positive BC-3 cells. Nuclear extracts were incubated with Glutathione conjugated beads bound to GST fused to the amino terminal domain of LANA and the carboxy terminal domain (see Figure 1) independently.

Figure 1.

GST tagged LANA-amino terminal domain and GST tagged LANA-carboxy terminal domain bound on Glutathione Sepharose beads was used as bait to pull down interacting protein from BC3 cell nuclear extract. BC-3 nuclear extract (500μg) was first pre-cleared with GST only (6mg) by incubating at 4°C for 4 hours with rotation. The supernatant was then pre-cleared with GST-2TK for 2 more hours at 4°C in similar way. The supernatant from this step was then incubated with GST-LANA-N at 4°C overnight. The beads were washed four times with binding buffer by centrifugation at 4°C. The beads were then collected and boiled at 95°C in SDS-PAGE loading buffer and run on SDS-PAGE with gel with appropriate controls. Protein bands unique to LANA pulldown lanes were excised and processed for MALDI-TOF peptide analysis

We hypothesized that protein complexes associated with the amino and carboxy termini of LANA would be involved in tethering, genome maintenance, replication, segregation and transcriptional regulation can be identified with a proteomic approach. Results obtained from our pull down assays, MALDI-TOF analysis and protein sequencing identified proteins belonging to about 36 classes of cellular proteins based on the scheme utilised by the human protein reference database, copyright® John Hopkins University and the Institute of Bioinformatics (Mishra et al., 2006; Peri et al., 2003). The predominant groups identified were DNA binding proteins, serine/threonine kinases, structural proteins, cytoskeleton proteins, transcriptional regulatory proteins as well as adapter and motor proteins all associated with the amino and carboxy termini domains of LANA (Table 1a and 1b). Other potentially important cellular proteins identified include polymerases, cell cycle control proteins, transcription factors, ubiquitin proteosome system regulatory proteins, cytokines, deacetylases and guaninine exchange factors. A total of 53 proteins were identified in association with the amino terminal domains of LANA and 56 proteins were identified associated with the carboxy terminal domain of LANA.

Table1a.

Cellular proteins associated with the amino terminal domain of LANA having a >95% CI score and arranged according to their functional category

| Protein functional category | Annotation | Acession No. | kDa/pI | Prot. Score (CI%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ribosomal subunit | 39S Ribosomal protein L32 | RM32_HUMAN | 21/9.78 | 99.5 |

| 40S ribosomal protein S10 | RS10_HUMAN | 19/10.15 | 98.9 | |

| Serine/Threonine Kinase | DNA dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit | PRKD_HUMAN | 468/6.75 | 100 |

| LIM domain kinase 1 | LIK1_HUMAN | 72/6.53 | 99 | |

| Protein kinase C, beta type | KPCB_HUMAN | 77/6.57 | 97 | |

| Adapter molecule | SH3 domain-binding protein 2 | 3BP2_HUMAN | 62/7.67 | 96.5 |

| Homer protein homolog 2 | HOM2_HUMAN | 40/6.03 | 95 | |

| A-kinase anchor protein 9 | AKA9_HUMAN | 453/4.95 | 99.8 | |

| Enzyme-Oxidoreductase | Arachidonate 12-lipoxygenase | LOXP_HUMAN | 75/5.82 | 95 |

| Cell cycle control protein | CENP-F kinetochore protein | CENF_HUMAN | 367/5.03 | 98.8 |

| Cytokine | Interferon alpha-1/13 precursor | INA1_HUMAN | 21/5.32 | 98.5 |

| Structural protein | Spectrin beta chain | SPCB_HUMAN | 246/5.13 | 96.9 |

| Lamin A/C | LAMA_HUMAN | 74/6.57 | 98.7 | |

| Spectrin beta chain | SPCB_HUMAN | 246/5.13 | 96.9 | |

| Myosin Heavy Chain | MYH8_HUMAN | 222/5.59 | 95 | |

| Cytoskeletol associated protein | Vinculin | VINC_HUMAN | 123/5.51 | 99.6 |

| Protein 4.1 | 41_HUMAN | 96/5.45 | 99.9 | |

| Bullous pemphigoid antigen 1 isoforms | BPA1_HUMAN | 371/6.38 | 99.9 | |

| Diaphanous protein homolog 1 | DIA1_HUMAN | 138/5.31 | 98.8 | |

| Leiomodin 1 | LMD1_HUMAN | 64/9.51 | 95 | |

| Nesprin 2 | SNE2_HUMAN | 795/5.26 | 99.7 | |

| Chemokine | Small inducible cytokine B14 precursor | SZ14_HUMAN | 11/9.94 | 97.4 |

| Transcription factor | Zinc finger protein 224 | Z224_HUMAN | 82/9.03 | 97.3 |

| Zinc finger protein 255 | Z255_HUMAN | 72/8.99 | 97.2 | |

| Transcription regulatory protein | SET and MYND domain containing protein 1 | SMY1_HUMAN | 56/6.66 | 96.8 |

| MAX binding protein MNT | MNT_HUMAN | 62/8.78 | 97 | |

| SET and MYND domain containing protein 1 | SMY1_HUMAN | 56/6.66 | 96.8 | |

| Possible global transcription activator SNF2L4 | SN24_HUMAN | 184/7.65 | 95.4 | |

| Motor protein | Myosin XVIIIB | M18B_HUMAN | 285/6.49 | 98.1 |

| Ciliary dynein heavy chain 11 | DYHB_HUMAN | 520/6.03 | 97.9 | |

| Kinesin-like protein | KF3C_HUMAN | 89/8.45 | 95 | |

| DNA binding protein | Synaptonemal complex protein 2 | SCP2_HUMAN | 175/9.01 | 99.7 |

| Centromeric protein E | CENE_HUMAN | 312/5.46 | 95 | |

| Zinc finger protein 179 | Z179_HUMAN | 68/8.88 | 95 | |

| Chaperon | DNAJ homolog subfamily C member 8 | DJC8_HUMAN | 30/9.15 | 98.9 |

| Unclassified | Nasopharyngeal epithelium specific protein 1 | NESG_HUMAN | 46/9.99 | 98.3 |

| MAGUK p55 subfamily member 6 | MPP6_HUMAN | 61/5.82 | 99.9 | |

| WD-repeat protein 9 | WDR9_HUMAN | 257/8.68 | 99.6 | |

| Ribosome biogenesis protein BMS1 homolog | BMS1_HUMAN | 145/6.04 | 95 | |

| Nesprin 1 | SNE1_HUMAN | 1010/5.38 | 95 | |

| Sperm-specific antigen 2 | SSF2_HUMAN | 29/4.83 | 95 | |

| Phosphorylase | Glycogen phosphorylase, muscle form | PHS2_HUMAN | 96/6.57 | 97.8 |

| Thymidine kinase 2, mitochondrial precursor | KITM_HUMAN | 31/8.71 | 95 | |

| RNA helicase | Putative pre-mRNA splicing factor RNA helicase | DD16_HUMAN | 119/6.39 | 98.5 |

| DNA Polymerase | DNA polymerase theta | DPOQ_HUMAN | 197/6.57 | 95 |

| Cell surface recepter | GDNF family receptor alpha 4 precurser | GFR4_HUMAN | 32/10.47 | 95 |

| Ubiquitin proteosome system protein | F-box only protein 16 | FX16_HUMAN | 34/10.05 | 96.6 |

| Intracellular ligand gated channel | Inositol 1.4,5-triphosphate receptor type 3 | IP3T_HUMAN | 303/6.04 | 99.6 |

| Phospho-transferase | Putative nucleoside diphosphate kinase | NDK8_HUMAN | 15/8.76 | 98 |

| Carboxylase | Propionyl-CoA carboxylase alpha chain | PCCA_HUMAN | 77/6.63 | 96.6 |

| Guanine nucleotide exchange factor | Guanine nucleotide exchange factor DBS | DBS_HUMAN | 123/6.16 | 99.3 |

| Deacetylase | Heparin sulfate N-deacetylase/N-sulfotransferase | HSS2_HUMAN | 101/8.81 | 95 |

| Hydroxylase | Cytochrome P450 | CPS1_HUMAN | 56/7.71 | 95 |

Protein previously shown to interact LANA

Table1b.

Cellular proteins associated with the carboxy terminal domain of LANA having a >95% CI score and arranged according to their functional category

| Protein functional category | Annotation | Acession No. | kDa/pI | Protein Score (CI%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serine/ Threonine Kinase | Serine/threonine-protein kinase 4 | STK4_HUMAN | 55/4.97 | 95 |

| Ribosomal subunit | 40S ribosomal protein S11 | RS11_HUMAN | 18/10.31 | 99.9 |

| 40S ribosomal protein S9 | RS9_HUMAN | 22/10.66 | 100 | |

| 40S ribosomal protein S10 | RS10_HUMAN | 19/10.15 | 99 | |

| 40S ribosomal protein S18 | RS18_HUMAN | 17/10.99 | 100 | |

| 40S ribosomal protein S16 | RS16_HUMAN | 16/10.21 | 100 | |

| Adapter Molecule | A-kinase anchor protein 9 | AKA9_HUMAN | 453/4.95 | 99.9 |

| Enzyme-Oxidoreductase | Myeloperoxidase precursor | PERM_HUMAN | 83/9.19 | 99.9 |

| Cytokine | Interferon alpha-1/13 precursor | INA1_HUMAN | 21/5.32 | 99.4 |

| Cell cycle control protein | CENP-F kinetochore protein | CENF_HUMAN | 367/5.03 | 99.3 |

| Diablo homolog, mitochondrial precursor | DBOH_HUMAN | 27/5.68 | 99.1 | |

| Structural protein | Myosin heavy chain, skeletal muscle, fetal | MYH4_HUMAN | 222/5.67 | 98.9 |

| Myosin heavy chain, cardiac muscle beta isoform | MYH7_HUMAN | 222/5.63 | 98.5 | |

| Nuclear mitotic apparatus protein 1 | NUMA_HUMAN | 238/5.63 | 95 | |

| Cytoskeletol associated protein | Src substrate cortactin | SRC8_HUMAN | 61/5.24 | 99.7 |

| Tropomyosin 1 alpha chain | TPM1_HUMAN | 32/4.69 | 97.1 | |

| Nebulette | NEBL_HUMAN | 116/7.89 | 96.9 | |

| Cytoskeletol protein | Merlin | MERL_HUMAN | 69/6.11 | 95 |

| Moesin | MOES_HUMAN | 67/6.09 | 97.8 | |

| Periplakin | PEPL_HUMAN | 204/5.44 | 96.6 | |

| Nebulin | NEBU_HUMAN | 772/9.1 | 97.9 | |

| Chemokine | Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase regulatory gamma subunit | P55G_HUMAN | 54/5.75 | 99.7 |

| Transcription factor | General transcription factor 3C polypeptide 1 | T3C1_HUMAN | 238/7.03 | 95 |

| Possible global transcription activator SNF2L4 | SN24_HUMAN | 184/7.65 | 95.4 | |

| Homeobox protein TGIF2LY | TGLY_HUMAN | 20/9.84 | 97.3 | |

| ATP-dependent RNA helicase A | DD16_HUMAN | 119/6.39 | 99 | |

| Transcription regulatory protein | RNA polymerase II transcription factor SIII subunit A2 | ELA2_HUMAN | 84/9.76 | 95 |

| Possible global transcription activator SNF2L1 | SN21_HUMAN | 114/8.72 | 97.5 | |

| Thyroid hormone receptor-associated protein complex 150 kDa component | T150_HUMAN | 150/xx | 95 | |

| Motor protein | Ciliary dynein heavy chain 11 | DYHB_HUMAN | 520/6.03 | 97.9 |

| Unclassified | Nasopharyngeal epithelium specific protein 1 | NESG_HUMAN | 46/9.99 | 99.9 |

| DNA binding protein | Synaptonemal complex protein 1 | SCP1_HUMAN | 113/5.85 | 95.9 |

| Centromeric protein E | CENE_HUMAN | 311/5.46 | 98.7 | |

| Histone H3.4 | H3T_HUMAN | 15/11.13 | 100 | |

| Histone H3.3 | H33_HUMAN | 15/11.27 | 100 | |

| Histone H2B type 12 | H2BX_HUMAN | 13/10.32 | 100 | |

| Histone H2A.e* | H2AE_HUMAN | 13/10.88 | 100 | |

| Histone H2A.q* | H2AQ_HUMAN | 13/10.90 | 100 | |

| Histone H2B.b* | H2BB_HUMAN | 13/10.32 | 100 | |

| Histone H2A.l* | H2AL_HUMAN | 14/11.05 | 100 | |

| Histone H2A.g* | H2AG_HUMAN | 14/10.9 | 100 | |

| Methyl-CpG-binding protein 2* | MBD2_HUMAN | 43/xx | 95 | |

| Chaperon | Nucleophosmin | NPM_HUMAN | 32/4.64 | 100 |

| ATPase | Putative pre-mRNA splicing factor RNA helicase | DD16_HUMAN | 119/6.39 | 98.5 |

| RNA Binding protein | Splicing factor, arginine/serine-rich 3 | SFR3_HUMAN | 19/11.64 | 99.3 |

| GTPase activating protein | 1-phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate phosphodiesterase beta 4 | PIB4_HUMAN | 134/6.47 | 95 |

| GTPase | Dynamin- like 120 kDa protein | OPA1_HUMAN | 111/7.88 | 99.1 |

| Nucleolar GTP-binding protein 1 | NOG1_HUMAN | 74/xx | 95 | |

| Anchor protein | Kinectin | KTN1_HUMAN | 156/5.52 | 99.4 |

| Plectin 1 | PLE1_HUMAN | 531/5.73 | 97.5 | |

| Ribonucleoprotein | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein M | ROM_HUMAN | 77/8.94 | 96.6 |

| MHC Complex protein | SET protein | SET_HUMAN | 33/4.23 | 99.9 |

| Transport/ cargo protein | ATP-binding cassette sub-family E member 1 | ABE1_HUMAN | 67/8.63 | 99 |

| Topoisomerase | DNA topoisomerase II, alpha isozyme* | TP2A_HUMAN | 174/xx | 95 |

| DNA topoisomerase I | TOP1_CRIGR | 90/xx | 95 |

Protein previously shown to interact LANA

A list of identified proteins specifically associated with the amino terminal of LANA and their functional properties are shown in Table 1a. Proteins which were deemed unclassified made up approximately 11%. The largest group of classified proteins interacting with the amino terminal domain of LANA were transcriptional factors and regulatory proteins which made up approximately 11%, cytoskeletol associated proteins which accounted for 9% and structural proteins which made up about 7% of the total proteins identified. Other important functional group of proteins interacting with the amino terminus of LANA included Serine/ threonine kinases, DNA binding proteins and cell cycle control proteins (see Table 1a).

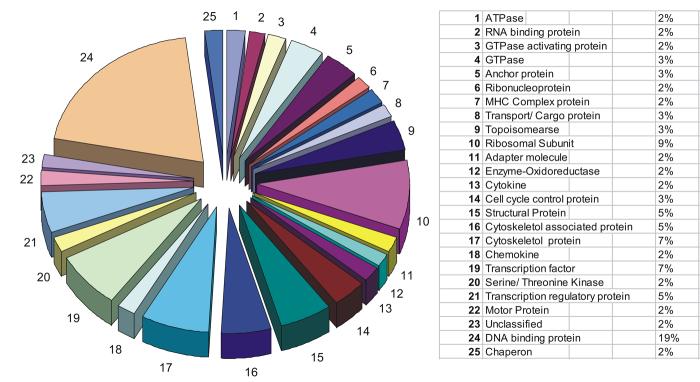

An analysis of the cellular proteins interacting with the carboxy terminus of LANA showed that the majority of the proteins belong to five major groups of proteins. These groups were DNA binding proteins which made up about 19% of the total proteins, 12% were cytoskeletol or associated proteins, transcription factors and regulatory proteins made up another 12% of the total, 9% were ribosomal subunits and 5% were structural proteins (Table 1b). Other groups less prevalent included transcriptional regulatory proteins, RNA binding proteins, ribonucleoproteins and ATPases (Table 1b).

The five major groups of interacting proteins supported previous work which showed that LANA had transcription and DNA binding activities (Groves et al., 2001; Hyun et al., 2001; Jeong, Papin, and Dittmer, 2001; Knight, Cotter, and Robertson, 2001; Lim et al., 2001; Renne et al., 2001; Verma, Lan, and Robertson, 2007). It is interesting to note that 12% of the proteins associated with the carboxy terminal were cytoskeletol proteins and may suggest a functional role for LANA in association with structural proteins. This may provide new clues as to the cellular molecules that are active members of complexes containing LANA responsible for tethering of the KSHV genome to the host chromosome.

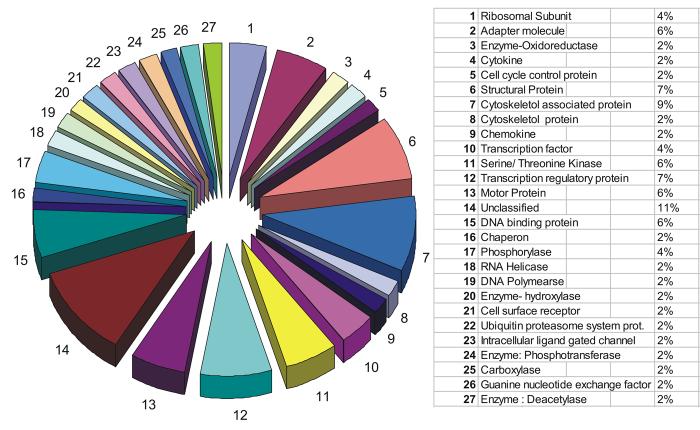

The data accumulated so far shows 27 specific categories of proteins associated with the amino terminal domain of LANA and 25 specific categories for the carboxy terminal domain (see Figure 2 and 3). Overall the total number of functional categories of proteins involved in LANA association was 36 with 16 of these categories of polypeptides including some identical proteins associating with both the amino and carboxy terminal of LANA (see Table 2). Thus, these results broadly suggest that there may be some interplay between the amino and carboxy termini and these two domains may be involved in similar functions in the context of KSHV persistence and pathogenesis.

Figure 2.

Proportional distribution of LANA-amino terminal interacting proteins in classes based on their functions. The proteins have been classified based on their molecular function as per the scheme followed by Human protein reference database Copyright © Johns Hopkins University and the Institute of Bioinformatics

Figure 3.

Proportional distribution of LANA-carboxy terminal interacting proteins in classes based on their functions. The proteins have been classified based on their molecular function as per the scheme followed by Human protein reference database Copyright © Johns Hopkins University and the Institute of Bioinformatics.

Table 2.

Comparison of proteome complex composition at amino and carboxy termini of LANA

| Protein Category | Carboxy terminal | Amino terminal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. Proteins identified | Proportion | No. Proteins identified | Proportion | ||

| 1 | ATPase | 1 | 2% | None | NA* |

| 2 | RNA binding protein | 1 | 2% | None | NA |

| 3 | GTPase activating protein | 1 | 2% | None | NA |

| 4 | GTPase | 2 | 3% | None | NA |

| 5 | Anchor protein | 2 | 3% | None | NA |

| 6 | Ribonucleoprotein | 1 | 2% | None | NA |

| 7 | MHC Complex protein | 1 | 2% | None | NA |

| 8 | Transport/ Cargo protein | 1 | 3% | None | NA |

| 9 | Topoisomearse | 2 | 3% | None | NA |

| 10 | Ribosomal Subunit | 5 | 9% | 2 | 4% |

| 11 | Adapter molecule | 1 | 2% | 3 | 6% |

| 12 | Enzyme-Oxidoreductase | 1 | 2% | 1 | 2% |

| 13 | Cytokine | 1 | 2% | 1 | 2% |

| 14 | Cell cycle control protein | 2 | 3% | 1 | 2% |

| 15 | Structural Protein | 3 | 5% | 4 | 7% |

| 16 | Cytoskeletol associated protein | 3 | 5% | 5 | 9% |

| 17 | Cytoskeletol protein | 4 | 7% | 1 | 2% |

| 18 | Chemokine | 1 | 2% | 1 | 2% |

| 19 | Transcription factor | 4 | 7% | 2 | 4% |

| 20 | Serine/ Threonine Kinase | 1 | 2% | 3 | 6% |

| 21 | Transcription regulatory protein | 3 | 5% | 4 | 7% |

| 22 | Motor Protein | 1 | 2% | 3 | 6% |

| 23 | Unclassified | 1 | 2% | 6 | 11% |

| 24 | DNA binding protein | 11 | 19% | 3 | 6% |

| 25 | Chaperon | 1 | 2% | 1 | 2% |

| 26 | Phosphorylase | None | NA | 2 | 4% |

| 27 | RNA Helicase | None | NA | 1 | 2% |

| 28 | DNA Polymearse | None | NA | 1 | 2% |

| 29 | Enzyme- hydroxylase | None | NA | 1 | 2% |

| 30 | Cell surface receptor | None | NA | 1 | 2% |

| 31 | Ubiquitin proteasome system protein | None | NA | 1 | 2% |

| 32 | Intracellular ligand gated channel | None | NA | 1 | 2% |

| 33 | Enzyme: Phosphotransferase | None | NA | 1 | 2% |

| 34 | Carboxylase | None | NA | 1 | 2% |

| 35 | Guanine nucleotide exchange factor | None | NA | 1 | 2% |

| 36 | Enzyme : Deacetylase | None | NA | 1 | 2% |

| Total | 55 | 53 | |||

NA: Not applicable

Regulation of cell signaling pathways

Protein kinases control cell signaling events through ATP-dependent phosphorylation of serine, threonine and tyrosine residuesof the target substartes. The recognition of these protein substrates by the kinases relies on two principal factors: proper subcellular co-localization and molecular interactions between the kinase and substrate (Lieser et al., 2005). LANA has previously been shown to interact with a number of cellular kinases including GSK-3β (Fujimuro and Hayward, 2003; Fujimuro and Hayward, 2004; Fujimuro et al., 2005), an unidentified kinase in association with RING3 (Mattsson et al., 2002; Platt et al., 1999), and most recently the Pim-1 kinase (Bajaj et al., 2006). LANA has also been shown to be critical for tethering of the viral episome to host cell chromosomes (Ballestas, Chatis, and Kaye, 1999; Cotter, Subramanian, and Robertson, 2001; Krithivas et al., 2002; Piolot et al., 2001) and is consistently expressed in all KSHV positive cells (Kedes et al., 1997). The interaction with kinases provides LANA with an opportunity to modulate cell signaling pathways and regulate host gene expression. Indeed, earlier studies have shown that LANA can function as a potent transcriptional regulator of both viral as well as host genes (Friborg et al., 1999; Fujimuro and Hayward, 2003; Lim et al., 2001; Lim et al., 2000; Radkov, Kellam, and Boshoff, 2000; Renne et al., 2001). In our study we found four novel proteins belonging to serine/ threonine kinase molecular class that interacted with LANA. DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit (DNA-PKcs) is one of the three subunit that forms DNA-PK and phosphorylates p53 at serine15 and serine37 that leads to its activation (Kim et al., 1999). The major role of DNA-PK is repairing breaks in double stranded DNA (Collis et al., 2005). Interaction with LANA may possibly lead to the inhibition of p53 phosphorylation which results in a block to apoptosis as well as an increase in chromosomal instability by blocking the DNA repair mechanism of DNAPK (Someya et al., 2006). Another LANA interacting kinase is LIM kinase-1 (LIMK1) which belongs to a small subfamily of proteins with a unique combination of 2 amino-terminal LIM motifs and a carboxy-terminal serine only protein kinase domain (Stanyon and Bernard, 1999). LIMK1 has been found to be over-expressed in prostate tumors and in prostate cancer cell lines (Davila et al., 2003). The interaction of LANA with kinases suggests a process which may provide an explanation for the mechanism by which LANA might be regulating host cell regulatory pathways and cell fate decisions. It is quite possible that interaction with LANA might interfere with the kinase activity of these proteins leading to a cascade of events. This results in enhancement of the tumorigenic phenotype or a blockade of apoptotic pathways.

A Potential role for LANA in cell division

DNA-binding proteins include various transcription factors, nucleases and histones which are involved in DNA packaging in the cell nucleus. Since one of the primary roles of LANA is the tethering of KSHV episome to the host cell chromatin and that LANA itself is a DNA binding protein (Groves et al., 2001; Hyun et al., 2001; Jeong, Papin, and Dittmer, 2001; Knight, Cotter, and Robertson, 2001; Lim et al., 2001; Renne et al., 2001; Verma, Lan, and Robertson, 2007), it is highly probable that other DNA binding proteins might interact with LANA either directly or indirectly through association with LANA bound to DNA. One of the proteins identified in our study associated with LANA in our pull-down assay was the centromeric protein E (CENP-E) (Table 1). CENP-E has been reported to be essential for stable, bi-oriented attachment of chromosomes to spindle microtubules, for development of tension across aligned chromosomes, for stabilization of spindle poles, and for satisfying the mitotic checkpoint (Yao et al., 2000). This interaction might suggests a role for LANA in ensuring efficient genomic replication during mitosis and later distribution of KSHV episomes to daughter nuclei through interaction with DNA binding proteinslike CENP-E which is involved in spindle attachment (Yao et al., 2000).

LANA is associated with cell cycle regulatory proteins

As obligatory intracellular parasites, viruses need a host cell to keep dividing to enable them to propagate. Herpesviruses, however, can survive in host cells for prolonged duration by virtue of their ability to remain latent and avoid detection by host immune responses and expression of a limited set of genes (Minarovits, 2006). When the host is immuno-compromised the virus can reactivate from latent infection and ultimately lead to an increase in viral load and subsequent development of lymphoproliferative disease (Cesarman and Mesri, 2007). One of the categories of proteins that might play an important role in modulating this process is the cell cycle regulatory proteins. In the present study we found that the KSHV latent protein LANA interacts with Mitosin/CENP-F which belongs to this class of regulatory proteins (Table 1). CENP-F is a large nuclear/ kinetochore protein which contains multiple leucine zipper motifs important for protein-protein interactions. Its expression levels and subcellular localization patterns are regulated in a cell cycle-dependent manner (Feng, Huang, and Yen, 2006). Recently, accumulating lines of evidence have suggested that it is a multifunctional protein involved in mitotic control, microtubule dynamics, transcriptional regulation, and muscle cell differentiation (Ma, Zhao, and Zhu, 2006). Thus, its interaction with LANA suggests a role for LANA in regulating these associated processes.

The role of LANA in transcription regulation

The regulation of host gene expression is an important aspect of the life cycle of KSHV that enables it to persist, replicate and propagate its genome into new cells. The most common mechanism is by regulating the transcription of host cell genes involved in cell fate decisions. LANA has previously been shown to be a potent transcriptional regulator of both viral as well as host cell genes (Friborg et al., 1999; Fujimuro and Hayward, 2003; Lim et al., 2001; Lim et al., 2000; Radkov, Kellam, and Boshoff, 2000; Renne et al., 2001). LANA is known to activate as wells as repress transcription (An et al., 2002; Groves et al., 2001; Hyun et al., 2001; Jeong, Papin, and Dittmer, 2001; Knight, Cotter, and Robertson, 2001; Lim et al., 2001; Renne et al., 2001). A look at the secondary structure of LANA suggests that there are potential sites for interactions with other cellular factors involved in transcription (Cotter and Robertson, 1999a). In addition, our study suggested that LANA may directly interact with a number of host transcriptional factors and transcription regulatory proteins (Table 1). These include the zinc finger protein 224, nucleoside diphosphate kinase B, MAX binding protein MNT (ROX protein), Sp110 nuclear body protein, SSX5 protein and SET and MYND domain containing protein 1 (see Table 1). The zinc finger protein 224 has been shown to contain a repressor domain and act as a transcriptional repressor (Lee et al., 2002). Interestingly, LANA also binds to MNT which when complexes with MAX and is known to repress transcription of E box promoters (Cvekl et al., 2004; Hurlin, Queva, and Eisenman, 1997) and can function as a possible tumor suppressor gene in this context (Cvekl et al., 2004). On the other hand, Nm23-H2 has been shown to function as a transcriptional activator of the translocated c-Myc allele in Burkitt’s lymphoma (Ji, Arcinas, and Boxer, 1995). SP110 is the closest human homolog of the mice Ipr1 gene which has been speculated to function in integrating signals generated by intracellular pathogens with mechanisms controlling innate immunity, cell death, and pathogenesis (Pan et al., 2005). SSX5 is also a cancer related protein whose expression has been shown to correlate with adverse prognosis in multiple myeloma patients (Taylor et al., 2005). The carboxy terminal of LANA also was able to pull down transcription factors including the Transcription factor IIIC (TFIIIC) which is a general RNA polymerase III transcription factor (Shen et al., 1996). The interaction of LANA with different transcription factors and regulators strongly suggest a potential role for LANA in dysregulating genes that are involved in tumorigenesis or tumor suppression. Moreover a large number of the transcription factors and regulators were shown to interact with the amino-terminal domain of LANA. The amino-terminus of LANA has been shown to bind to the chromosomal linker protein histone H1 and thus contributing to tethering of the KSHV genome to host cell chromosomes (Cotter and Robertson, 1999b; Verma and Robertson, 2003). Our results suggest that the amino-terminal domain of LANA may play a major role in transcriptional regulation of other genes when compared to the carboxy-terminal domain. In fact these two domains may co-operate with each other by contributing to the transcription regulation of specific cellular genes.

Cytoskeleton proteins associate with LANA

LANA is critical for the establishment of latent KSHV infection through maintenance of the viral episome (Ballestas, Chatis, and Kaye, 1999; Ballestas and Kaye, 2001; Moorman, Willer, and Speck, 2003; Piolot et al., 2001). LANA also tethers the KSHV genome to host cell chromosome (Cotter and Robertson, 1999b; Verma and Robertson, 2003). It is also believed that the KSHV genome persists as chromatin in latently infected cells. Therefore it is not surprising that LANA interacts with several DNA binding proteins including histones (Barbera et al., 2006a; Barbera et al., 2006b; Cotter and Robertson, 1999b; Shinohara et al., 2002). Our assays also showed the binding of LANA to several structural proteins and cytoskeletol associated proteins (see Table1). Interestingly, one such protein was identified as the centrosomal protein Cep290 which contains a series of coiled-coil domains important for association with the centrosomes and may reflect a role for LANA in regulation of cell shape, polarity, motility and cell division through its effects on the mitotic spindle apparatus (Warby, 2006).

Uncategorized proteins associated with LANA

Other proteins of interest bound to the amino terminal domain of LANA include a putative RNA helicase (MOV10), the theta subunit of DNA polymerase, a phosphotransferase (NDP kinase), a Guanine nucleotide exchange factor (DBL’s big sister), and a cell cycle control protein (Centromere protein F) (see Table 1a). The carboxy terminus of LANA also showed interactions with an ATPase (ATP-dependent RNA helicase), a RNA binding protein (pre-mRNA splicing factor SRP20), a GTPase activating protein, and a GTPase (see Table 1b). The identification of these proteins also provides some insights into the potential additional roles for LANA in a range of distinct multiple cellular processes that are yet to be explored.

The amino and carboxy termini of LANA interact with CENP-F and can from a complex with each other in vitro

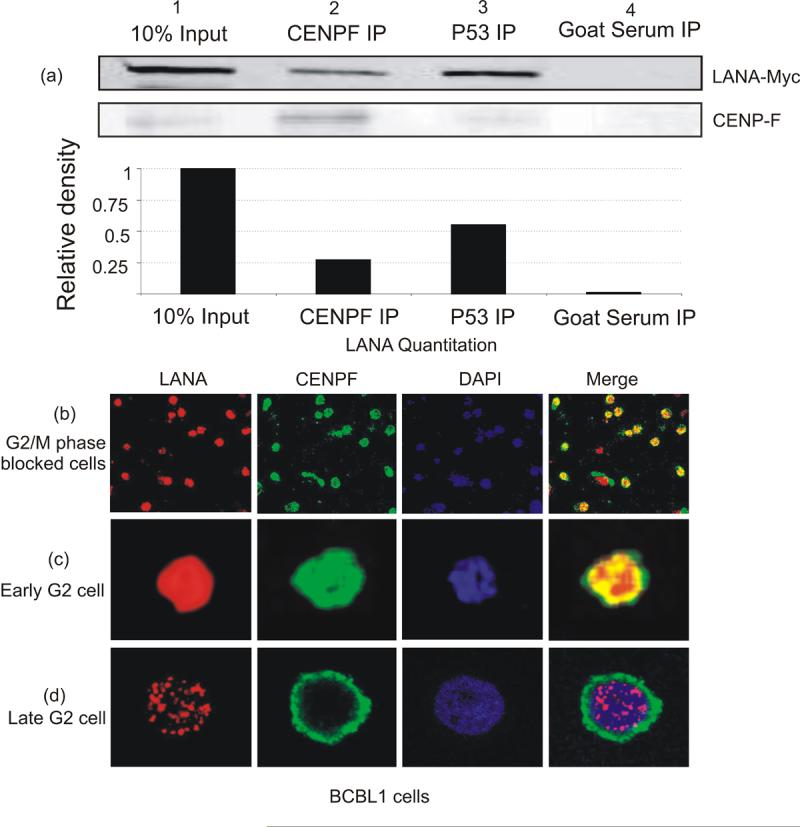

Analysis of the amino acid sequence of LANA reveals three major protein domains. These include the amino-terminal domain, the central domain and the carboxy-terminal domain (Verma, Borah, and Robertson, 2004). On comparing the proteins interacting with the amino terminus of LANA with those seen with the carboxy terminus of LANA, we noticed that several of the host cell proteins showed interaction with both the carboxy and amino termini of LANA (see Table 2). One of the most prominent of such proteins were the Centromeric proteins CENP-E and CENP-F as well as another DNA binding protein the syneptonemal complex protein 2 (SCP-2 protein) (Tables 1a and 1b). We hypothesized that the amino and carboxy termini of LANA might be folded in such a way as to facilitate their interaction with these common interacting proteins and possibly with each other. To test this hypothesis we first validated the interaction of CENP-F with full length LANA. CENP-F was identified in association with both the amino and carboxy termini of LANA. Cell lysates prepared from 293T cells transfected with Myc-tagged LANA or PA3M vector alone control were incubated with anti-CENP-F antibody after preclearing with matched immunoglobulin G control antibody. The immune complexes were precipitated using a mixture of protein A+G beads and then probed with anti-Myc antibody in western blot. The results of these experiments showed that LANA can coimmunoprecipitate complexes which contained CENP-F when expressed in human epithelial cells (Figure 4a, top panel).

Figure 4.

CENP-F interacts with LANA. 293T were transected with LANA-Myc expressing construct and harvested after 24 hours. CENP-F was immuno-precipitated from the cell lysate using specific antibody and then probed for coimmunoprecipitated LANA with anti-Myc antibody. Anti-p53 antibody was used as positive control to coimmunoprecipitate LANA and normal goat serum was used as non-specific antibody control. Lane 2 (fig. 5a, top panel) shows the coimmunoprecipated LANA compared to 10% input in lane 1. Lane 3 shows the coimmunoprecipitated LANA along with p53 as positive control. Bottom panel (fig 5a) shows the same membrane reprobed with CENP-F antibody. The immunofluoroscence assay was done to visualize the localization of LANA (nuclear) and CENP-F (nuclear membrane) in KSHV positive BCBL-1 cells. The cells were blocked in G2/M phase by nocadozole treatmen (fig. 5b) Panel c shows the localisation of CENP-F in nuclear matrix partially colocalising with LANA. Panel d shows a cell in late G2 phase with CENP-F localising mainly around nuclear envelope

To further support the potential associations of CENP-F with LANA, we investigated the localization of LANA and CENP-F in normal and G2/M phase arrested BCBL-1 cells by immunofluorescence assay. Localization of LANA using rabbit anti-LANA antibody visualized by Alexa Fluor 594 showed the characteristic punctate pattern of LANA in the nuclei of BCBL-1 cells (Figure 4, see panel b) as reported previously (Ballestas, Chatis, and Kaye, 1999; Cotter and Robertson, 1999b). CENP-F expression is regulated by the cell cycle, reaching maximum levels in G2/M, followed by rapid degradation after mitosis (Liao et al., 1995; Zhu et al., 1995). Therefore, we blocked the BCBL-1 cells at the G2/M phase by nocadozole treatment. This resulted in the majority of cells been blocked in G2/M phase (Figure 4). As cells progress through G2, CENP-F begins to localize around the nuclear boundary (Figure 4, panel c and d). CENP-F was detected by mouse primary anti-CENP-F antibody and detected by Alexa Fluor 488 secondary antibody showed nuclear staining (Figure 4). These results suggest that LANA is present in compartments similar to that of CENP-F in KSHV-positive cells. This occurs in G2 phase of the cell cycle when CENP-F is expressed at its maximum level and is localized in nuclear matrix (Figure 4). The specificity of the signals was confirmed by incubating the cells with control immunoglobulin G and Alexa Fluor secondary antibodies which showed no specific signals (data not shown). Thus, these colocalization data strongly suggests that LANA associates with CENP-F during the G2 phase of the cell cycle when the expression of CENP-F is at the highest levels and its localization is diffused within the nuclear matrix.

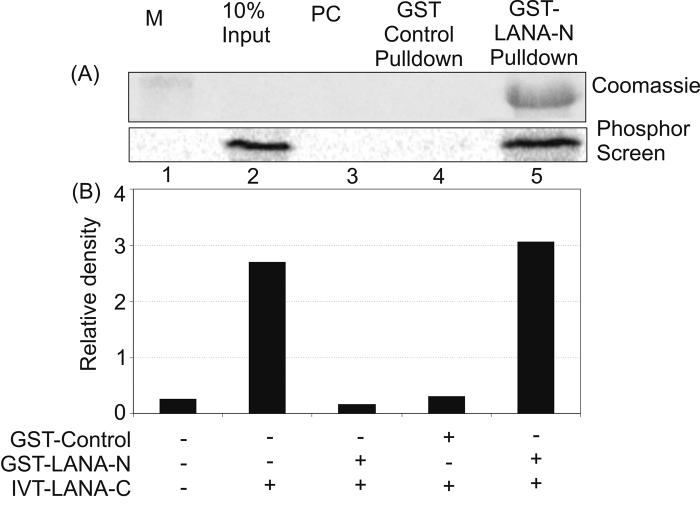

To confirm whether or not the carboxy and amino termini of LANA can interact with each other, we performed in vitro binding assays with GST fusion proteins of LANA-amino terminus with in vitro translated LANA-carboxy terminus. The binding data demonstrated that the amino terminus of LANA do directly interact with the carboxy terminus of LANA (Figure 5). When the results were quantified using Image Quant analysis, the binding activity suggested a greater than 10% binding affinity based on a comparison with input protein.

Figure 5.

LANA-amino terminus interacts with LANA-carboxy terminal doamin. GST tagged LANA-amino domain (aa 1-340) protein was incubated with in vitro translated LANA-carboxy terminus labeled with S35 Methionine. LANA-carboxy doman showed binding to the amino terminal domain (lower panel, lane 5) but not to GST control (Lower panel, lane 4). The coomassie stained gel with GST-LANA amino terminus is shown in the upper panel.

MALDI-TOF approach for identification of proteins interacting with LANA

The application of MALDI-TOF based peptide analysis to identify LANA associated proteins from nuclear extract was able to identify a number of known LANA interacting proteins, and has significantly expanded the number and categories of proteins which interact with the Kapsoi sarcoma associated latent nuclear antigen. A large number of proteins were identified that have potentially important roles in KSHV latency, specifically the DNA polymerase theta and DNA-PKcs. LANA therefore forms complexes with proteins belonging to several defined functional classes. This expanded view of cellular interacting proteins suggests new cellular functional areas that may be involved in KSHV biology. Further examination of the coupling of some of the identified proteins to LANA function or KSHV latency, by overexpression or by specific knock down of individual proteins using siRNA, may identify drug targets for KSHV associated diseases. The fingerprint of interacting partners derived in this study may be useful for further comparisons, for example between the KSHV LANA and other gammaherpesvirus latent proteins (Ackermann, 2006), or to examine the relation between differences in function and changes in complexes with cellular interacting proteins.

Materials & Methods

Cell lines and Plasmids

KSHV positive cell line BC-3 was cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 7% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2mM L-glutamine and 25 U/ml of penicillin-streptomycin. This cell line was grown at 37°C in a humidified chamber supplemented with 5% CO2. The carboxy-terminal domain (945 to 1162 aa) and amino-terminal domain (1-340aa) constructs tagged with GST were prepared by PCR amplification of fragment from PA3M-LANA followed by cloning into pGEX-2TK vector within BamH1 and EcoR1 restriction sites.

Preparation of GST fusion proteins for in vitro binding assays

Escherichia coli BL-21 cells were transformed with plasmid constructs for each fusion protein, and single colonies were picked and grown overnight in 2 ml of Luria-Bertani (LB) medium. Five hundred milliliters of LB medium were inoculated at a dilution of 1:200 and allowed to shake at 37°C until the mid-exponential growth phase. Cells were then induced with 1 mM IPTG (isopropyl-ß-D-thiogalactopyranoside) for 4 h with continuous shaking at 37°C. Cells were harvested and sonicated, and the proteins were solubilized in the presence of protease inhibitors. Solubilized proteins were incubated with Glutathione S-transferase (GST)-Sepharose beads for 6 h or overnight at 4°C with rotation and then collected by centrifugation and washed three times in NETN buffer with protease inhibitors. GST fusion proteins bound to beads were used for binding assays and stored in NETN buffer with protease inhibitors and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride at 4°C.

Preparation of nuclear extract from KSHV positive (BC3) cells

To isolate nuclear proteins binding with LANA-amino and LANA-carboxy terminal domains, nuclear extract was prepared from BC-3 cells. BC-3 cells are B cells latently infected with KSHV (Cesarman et al., 1995b) expressing LANA. Therefore these cells are expected to express large amount of LANA interacting proteins. The nuclear extract was prepared to enrich for low abundance proteins and to overcome the low sensitivity of experimental setup that involves manual excision of single protein bands from SDS-PAGE. Briefly, 1000 × 106 cells were harvested, washed with cold PBS, resuspended in buffer A (10mM HEPES, 10mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 5mM DTT, and protease inhibitors), incubated on ice for 1 hour. These were then homogenized in douncer and the extracted nuclei were separated by centrifugation at low speed. Nuclei were then lysed by resuspending in Buffer B (20mM HEPES, 10% glycerol, 420 mM Nacl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 5mM DTT and protease inhibitors) for 30 minutes. Nuclear membrane debris was removed by high speed centrifugation and supernatant containing nuclear proteins was mixed with equal volume of buffer C (20mM HEPES, 30% glycerol, , 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EDTA, 5mM DTT and protease inhibitors). The protein concentration was determined by Bradford assay and the nuclear extract was stored at -80° C.

GST-fusion pull down assay for identification of LANA interacting proteins

BC-3 nuclear extract (500μg) was first pre-cleared with GST only (6mg) by incubating at 4°C for 4 hours with rotation. The supernatant was then pre-cleared with GST-2TK for 2 more hours at 4°C in similar way. The supernatant from this step was then incubated with GST-LANA -C or GST-LANA-N at 4°C overnight. The beads were washed four times with binding buffer at 4°C. The beads were then collected and boiled at 95°C in SDS-PAGE loading buffer and run on SDS-PAGE with gel with appropriate controls.

In vitro binding of LANA amino to LANA carboxy terminal proteins

LANA-carboxy terminal was expressed in vitro by the coupled in vitro transcription/translation system (TNT) of Promega Inc. (Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, using [35S]methionine/cysteine (Perkin Elmer Inc., Boston, MA) in the TNT reaction mixture. LANA-N-GST fusion protein (approximately 10 μg for each reaction), expressed in Escherichia coli were used for in vitro bindings. In vitro-translated proteins were precleared with Glutathione-Sepharose beads in binding buffer (1× phosphate-buffered saline, 0.1% NP-40, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, 10% glycerol, 1 mM phenylmethyl sulfonyl fluoride, 2 μg of aprotinin per ml) for 30 min. Precleared labeled protein were then incubated with either GST or GST-LANA-amino fusion proteins in binding buffer. Binding was performed overnight at 4°C with constant rotation followed by centrifugation for collecting the beads. The beads were washed three times with 1 ml of binding buffer followed by resuspending them in SDS lysis buffer and resolving them on SDS-PAGE. The bound fraction was analyzed after drying the gel and exposing to a phosphorImager plate (Molecular Dynamics, Inc.).

Protein isolation and mass spectroscopy

Visible protein bands between 18 to >204 kDa size that were unique to the GST-LANA-N or GST-LANA-C pull down lanes were cut out of the Coomassie stained gel and in-gel digestion conducted with sequencing grade trypsin. The excised gel pieces were then washed with 100μl of 50mM ammonium bicarbonate in 50% acetonitrile. They were then shrunk by dehydration in acetonitrile followed by solvent removal in a vaccum centrifuge. They were swollen in 100μl of a digestion buffer containing 50mM ammonium bicarbonate, 5mM calcium chloride (50μl), and 12.5 ng/ml of trypsin and enzymatic cleavage was allowed to continue overnight at 37°C. Peptides were extracted into 20mM ammonium bicarbonate (100μl) followed by two separate extractions into 100μl of water/acetonitrite/formic acid (10:10:1, v/v/v). After evaporation to dryness, peptides were redissolved in 10μl of 5% acetonitrile and 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid.

One portion (1/10) of the digest was analysed directly by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ ionization-TOF mass spectroscopy for molecular weight determination and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ ionization-TOF/TOF for sequence information (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The other portion (1/3) was subjected to nanoLC/Qstar-XL (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) analysis. The data were analyzed with GPS explorer (for TOF-TOF) or Analyst QS (for Qstar) software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and were searched with Mascot software (Matrix Science Ltd., London, UK) against the National Center for Biotechnology Information database. The proteins with CI% score above 95 were selected for analysis.

Immunoprecipitation and Western blotting

After 48 h of incubation, the transfected cells were lysed in cold radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 7.6], 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1% Nonidet P-40, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, aprotinin [1 μg/ml], and pepstatin [1 μg/ml]) on ice and homogenized. The lysates were precleared with Protein A/G-Sepharose beads (Amersham Biosciences Inc., Piscataway, N.J.), and then incubated first with antibodies against myc (1 μg) in immunoprecipitation (IP) buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 10% glycerol, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1% Tween 20, 0.1 M KCl, 1× protease inhibitor cocktail [Amersham Biosciences Inc., Piscataway, NJ], and 0.5 mM dithiothreitol) overnight at 4°C with constant rotation and then with Protein A/G (50/50)-Sepharose beads for 1 h. Beads were washed three times with IP buffer and resuspended in 40 μl of 2× sodium dodecyl sulfate Laemmli buffer. The sample was subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Western blot analyses were performed using primary monoclonal antibodies against myc (9E10), and ß-actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA). Detection and quantification were done using a Li-Cor Odyssey scanner (Li-Cor, Inc., Lincoln, NE).

Immunofluoroscence assays

Nocadozole treated BCBL1 cells were washed with PBS and spread evenly on a slide. The cells were fixed with 1:1 methanol-acetone for 10 min at -20°C, dried, and rehydrated with PBS. For blocking, cells were incubated with PBS containing 3% bovine serum albumin and 1% glycine for 30 min. Cells were then incubated with appropriate antibodies (1:100 dilution of anti-CENPF antibody, and a 1:100 dilution of anti-LANA antibody). Slides were washed three times in phosphate-buffered saline and further incubated with a 1:1,000 dilution of goat anti-rabbit or goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin-fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated secondary antibodies. Slides were examined with an Olympus IX70 fluorescence microscope, and images were captured with a PixelFly digital camera (Cooke, Inc., Auburn Hills, MI).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society of America and public health service grants from the NCI CA072510, CA108461 and CA091792 and from NIDCR DE01436 and DEO17338 and NIAID AI067037 (to ESR). ESR is a scholar of the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society of America. We are thankful to Dr Stephen Taylor (University of Manchester, Manchester, UK) for providing the anti-CENPF antibody cells. We also thank Chao-Xing Yuan and the Proteomics Core Facility at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine for their technical support.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ackermann M. Pathogenesis of gammaherpesvirus infections. Vet Microbiol. 2006;113(3-4):211–22. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2005.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An J, Lichtenstein AK, Brent G, Rettig MB. The Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) induces cellular interleukin 6 expression: role of the KSHV latency-associated nuclear antigen and the AP1 response element. Blood. 2002;99(2):649–54. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.2.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajaj BG, Verma SC, Lan K, Cotter MA, Woodman ZL, Robertson ES. KSHV encoded LANA upregulates Pim-1 and is a substrate for its kinase activity. Virology. 2006;351(1):18–28. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballestas ME, Chatis PA, Kaye KM. Efficient persistence of extrachromosomal KSHV DNA mediated by latency-associated nuclear antigen. Science. 1999;284(5414):641–4. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5414.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballestas ME, Kaye KM. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latency-associated nuclear antigen 1 mediates episome persistence through cis-acting terminal repeat (TR) sequence and specifically binds TR DNA. J Virol. 2001;75(7):3250–8. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.7.3250-3258.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbera AJ, Chodaparambil JV, Kelley-Clarke B, Joukov V, Walter JC, Luger K, Kaye KM. The nucleosomal surface as a docking station for Kaposi’s sarcoma herpesvirus LANA. Science. 2006a;311(5762):856–61. doi: 10.1126/science.1120541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbera AJ, Chodaparambil JV, Kelley-Clarke B, Luger K, Kaye KM. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus LANA hitches a ride on the chromosome. Cell Cycle. 2006b;5(10):1048–52. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.10.2768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borah S, Verma SC, Robertson ES. ORF73 of herpesvirus saimiri, a viral homolog of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus, modulates the two cellular tumor suppressor proteins p53 and pRb. J Virol. 2004;78(19):10336–47. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.19.10336-10347.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Q, Lan K, Verma SC, Si H, Lin D, Robertson ES. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latent protein LANA interacts with HIF-1 alpha to upregulate RTA expression during hypoxia: Latency control under low oxygen conditions. J Virol. 2006a;80(16):7965–75. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00689-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai QL, Knight JS, Verma SC, Zald P, Robertson ES. EC5S ubiquitin complex is recruited by KSHV latent antigen LANA for degradation of the VHL and p53 tumor suppressors. PLoS Pathog. 2006b;2(10):e116. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesarman E, Chang Y, Moore PS, Said JW, Knowles DM. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in AIDS-related body-cavity-based lymphomas. N Engl J Med. 1995a;332(18):1186–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199505043321802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesarman E, Mesri EA. Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus and other viruses in human lymphomagenesis. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2007;312:263–87. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-34344-8_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesarman E, Moore PS, Rao PH, Inghirami G, Knowles DM, Chang Y. In vitro establishment and characterization of two acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related lymphoma cell lines (BC-1 and BC-2) containing Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like (KSHV) DNA sequences. Blood. 1995b;86(7):2708–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y, Cesarman E, Pessin MS, Lee F, Culpepper J, Knowles DM, Moore PS. Identification of herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in AIDS-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma. Science. 1994;266(5192):1865–9. doi: 10.1126/science.7997879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collis SJ, DeWeese TL, Jeggo PA, Parker AR. The life and death of DNA-PK. Oncogene. 2005;24(6):949–61. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotter I, Murray A, Robertson ES. The Latency-Associated Nuclear Antigen Tethers the Kaposi’s Sarcoma-Associated Herpesvirus Genome to Host Chromosomes in Body Cavity-Based Lymphoma Cells. Virology. 1999a;264(2):254–264. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotter MA, 2nd, Robertson ES. The latency-associated nuclear antigen tethers the Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus genome to host chromosomes in body cavity-based lymphoma cells. Virology. 1999b;264(2):254–64. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotter MA, 2nd, Subramanian C, Robertson ES. The Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latency-associated nuclear antigen binds to specific sequences at the left end of the viral genome through its carboxy-terminus. Virology. 2001;291(2):241–59. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cvekl A, Jr., Zavadil J, Birshtein BK, Grotzer MA, Cvekl A. Analysis of transcripts from 17p13.3 in medulloblastoma suggests ROX/MNT as a potential tumour suppressor gene. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40(16):2525–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davila M, Frost AR, Grizzle WE, Chakrabarti R. LIM kinase 1 is essential for the invasive growth of prostate epithelial cells: implications in prostate cancer. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(38):36868–75. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306196200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dourmishev LA, Dourmishev AL, Palmeri D, Schwartz RA, Lukac DM.Molecular genetics of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (human herpesvirus-8) epidemiology and pathogenesis Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 2003672175–212. table of contents [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng J, Huang H, Yen TJ. CENP-F is a novel microtubule-binding protein that is essential for kinetochore attachments and affects the duration of the mitotic checkpoint delay. Chromosoma. 2006;115(4):320–9. doi: 10.1007/s00412-006-0049-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friborg J, Jr., Kong W, Hottiger MO, Nabel GJ. p53 inhibition by the LANA protein of KSHV protects against cell death. Nature. 1999;402(6764):889–94. doi: 10.1038/47266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimuro M, Hayward SD. The latency-associated nuclear antigen of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus manipulates the activity of glycogen synthase kinase-3beta. J Virol. 2003;77(14):8019–30. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.14.8019-8030.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimuro M, Hayward SD. Manipulation of glycogen-synthase kinase-3 activity in KSHV-associated cancers. J Mol Med. 2004;82(4):223–31. doi: 10.1007/s00109-003-0519-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimuro M, Liu J, Zhu J, Yokosawa H, Hayward SD. Regulation of the interaction between glycogen synthase kinase 3 and the Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latency-associated nuclear antigen. J Virol. 2005;79(16):10429–41. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.16.10429-10441.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimuro M, Wu FY, ApRhys C, Kajumbula H, Young DB, Hayward GS, Hayward SD. A novel viral mechanism for dysregulation of beta-catenin in Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latency. Nat Med. 2003;9(3):300–6. doi: 10.1038/nm829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gencer S, Salepci T, Ozer S. Evaluation of infectious etiology and prognostic risk factors of febrile episodes in neutropenic cancer patients. J Infect. 2003;47(1):65–72. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(03)00044-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves AK, Cotter MA, Subramanian C, Robertson ES. The latency-associated nuclear antigen encoded by Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus activates two major essential Epstein-Barr virus latent promoters. J Virol. 2001;75(19):9446–57. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.19.9446-9457.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurlin PJ, Queva C, Eisenman RN. Mnt, a novel Max-interacting protein is coexpressed with Myc in proliferating cells and mediates repression at Myc binding sites. Genes Dev. 1997;11(1):44–58. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyun TS, Subramanian C, Cotter MA, 2nd, Thomas RA, Robertson ES. Latency-associated nuclear antigen encoded by Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus interacts with Tat and activates the long terminal repeat of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in human cells. J Virol. 2001;75(18):8761–71. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.18.8761-8771.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong J, Papin J, Dittmer D. Differential regulation of the overlapping Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus vGCR (orf74) and LANA (orf73) promoters. J Virol. 2001;75(4):1798–807. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.4.1798-1807.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji L, Arcinas M, Boxer LM. The transcription factor, Nm23H2, binds to and activates the translocated c-myc allele in Burkitt’s lymphoma. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(22):13392–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.22.13392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kedes DH, Lagunoff M, Renne R, Ganem D. Identification of the gene encoding the major latency-associated nuclear antigen of the Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J Clin Invest. 1997;100(10):2606–10. doi: 10.1172/JCI119804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim ST, Lim DS, Canman CE, Kastan MB. Substrate specificities and identification of putative substrates of ATM kinase family members. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(53):37538–43. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.53.37538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight JS, Cotter MA, 2nd, Robertson ES. The latency-associated nuclear antigen of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus transactivates the telomerase reverse transcriptase promoter. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(25):22971–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101890200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krithivas A, Fujimuro M, Weidner M, Young DB, Hayward SD. Protein interactions targeting the latency-associated nuclear antigen of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus to cell chromosomes. J Virol. 2002;76(22):11596–604. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.22.11596-11604.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krithivas A, Young DB, Liao G, Greene D, Hayward SD. Human herpesvirus 8 LANA interacts with proteins of the mSin3 corepressor complex and negatively regulates Epstein-Barr virus gene expression in dually infected PEL cells. J Virol. 2000;74(20):9637–45. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.20.9637-9645.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan K, Kuppers DA, Robertson ES. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus reactivation is regulated by interaction of latency-associated nuclear antigen with recombination signal sequence-binding protein Jkappa, the major downstream effector of the Notch signaling pathway. J Virol. 2005;79(6):3468–78. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.6.3468-3478.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan K, Kuppers DA, Verma SC, Robertson ES. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-encoded latency-associated nuclear antigen inhibits lytic replication by targeting Rta: a potential mechanism for virus-mediated control of latency. J Virol. 2004;78(12):6585–94. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.12.6585-6594.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee TH, Lwu S, Kim J, Pelletier J. Inhibition of Wilms tumor 1 transactivation by bone marrow zinc finger 2, a novel transcriptional repressor. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(47):44826–37. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205667200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao H, Winkfein RJ, Mack G, Rattner JB, Yen TJ. CENP-F is a protein of the nuclear matrix that assembles onto kinetochores at late G2 and is rapidly degraded after mitosis. J Cell Biol. 1995;130(3):507–18. doi: 10.1083/jcb.130.3.507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieser SA, Aubol BE, Wong L, Jennings PA, Adams JA. Coupling phosphoryl transfer and substrate interactions in protein kinases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1754(1-2):191–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2005.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim C, Gwack Y, Hwang S, Kim S, Choe J. The transcriptional activity of cAMP response element-binding protein-binding protein is modulated by the latency associated nuclear antigen of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(33):31016–22. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102431200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim C, Sohn H, Gwack Y, Choe J. Latency-associated nuclear antigen of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (human herpesvirus-8) binds ATF4/CREB2 and inhibits its transcriptional activation activity. J Gen Virol. 2000;81(Pt 11):2645–52. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-11-2645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L, Zhao X, Zhu X. Mitosin/CENP-F in mitosis, transcriptional control, and differentiation. J Biomed Sci. 2006;13(2):205–13. doi: 10.1007/s11373-005-9057-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattsson K, Kiss C, Platt GM, Simpson GR, Kashuba E, Klein G, Schulz TF, Szekely L. Latent nuclear antigen of Kaposi’s sarcoma herpesvirus/human herpesvirus-8 induces and relocates RING3 to nuclear heterochromatin regions. J Gen Virol. 2002;83(Pt 1):179–88. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-83-1-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minarovits J. Epigenotypes of latent herpesvirus genomes. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2006;310:61–80. doi: 10.1007/3-540-31181-5_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra GR, Suresh M, Kumaran K, Kannabiran N, Suresh S, Bala P, Shivakumar K, Anuradha N, Reddy R, Raghavan TM, Menon S, Hanumanthu G, Gupta M, Upendran S, Gupta S, Mahesh M, Jacob B, Mathew P, Chatterjee P, Arun KS, Sharma S, Chandrika KN, Deshpande N, Palvankar K, Raghavnath R, Krishnakanth R, Karathia H, Rekha B, Nayak R, Vishnupriya G, Kumar HG, Nagini M, Kumar GS, Jose R, Deepthi P, Mohan SS, Gandhi TK, Harsha HC, Deshpande KS, Sarker M, Prasad TS, Pandey A. Human protein reference database--2006 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34(Database issue):D411–4. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore PS, Chang Y. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus immunoevasion and tumorigenesis: two sides of the same coin? Annu Rev Microbiol. 2003;57:609–39. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.090824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moorman NJ, Willer DO, Speck SH. The gammaherpesvirus 68 latency-associated nuclear antigen homolog is critical for the establishment of splenic latency. J Virol. 2003;77(19):10295–303. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.19.10295-10303.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien K, Cokkinides V, Jemal A, Cardinez CJ, Murray T, Samuels A, Ward E, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics for Hispanics, 2003. CA Cancer J Clin. 2003;53(4):208–26. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.53.4.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan H, Yan BS, Rojas M, Shebzukhov YV, Zhou H, Kobzik L, Higgins DE, Daly MJ, Bloom BR, Kramnik I. Ipr1 gene mediates innate immunity to tuberculosis. Nature. 2005;434(7034):767–72. doi: 10.1038/nature03419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peri S, Navarro JD, Amanchy R, Kristiansen TZ, Jonnalagadda CK, Surendranath V, Niranjan V, Muthusamy B, Gandhi TK, Gronborg M, Ibarrola N, Deshpande N, Shanker K, Shivashankar HN, Rashmi BP, Ramya MA, Zhao Z, Chandrika KN, Padma N, Harsha HC, Yatish AJ, Kavitha MP, Menezes M, Choudhury DR, Suresh S, Ghosh N, Saravana R, Chandran S, Krishna S, Joy M, Anand SK, Madavan V, Joseph A, Wong GW, Schiemann WP, Constantinescu SN, Huang L, Khosravi-Far R, Steen H, Tewari M, Ghaffari S, Blobe GC, Dang CV, Garcia JG, Pevsner J, Jensen ON, Roepstorff P, Deshpande KS, Chinnaiyan AM, Hamosh A, Chakravarti A, Pandey A. Development of human protein reference database as an initial platform for approaching systems biology in humans. Genome Res. 2003;13(10):2363–71. doi: 10.1101/gr.1680803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piolot T, Tramier M, Coppey M, Nicolas JC, Marechal V. Close but distinct regions of human herpesvirus 8 latency-associated nuclear antigen 1 are responsible for nuclear targeting and binding to human mitotic chromosomes. J Virol. 2001;75(8):3948–59. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.8.3948-3959.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platt GM, Simpson GR, Mittnacht S, Schulz TF. Latent nuclear antigen of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus interacts with RING3, a homolog of the Drosophila female sterile homeotic (fsh) gene. J Virol. 1999;73(12):9789–95. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.12.9789-9795.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radkov SA, Kellam P, Boshoff C. The latent nuclear antigen of Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus targets the retinoblastoma-E2F pathway and with the oncogene Hras transforms primary rat cells. Nat Med. 2000;6(10):1121–7. doi: 10.1038/80459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renne R, Barry C, Dittmer D, Compitello N, Brown PO, Ganem D. Modulation of cellular and viral gene expression by the latency-associated nuclear antigen of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J Virol. 2001;75(1):458–68. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.1.458-468.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblatt KA, Carter JJ, Iwasaki LM, Galloway DA, Stanford JL. Serologic evidence of human papillomavirus 16 and 18 infections and risk of prostate cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12(8):763–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y, Igo M, Yalamanchili P, Berk AJ, Dasgupta A. DNA binding domain and subunit interactions of transcription factor IIIC revealed by dissection with poliovirus 3C protease. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16(8):4163–71. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.8.4163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinohara H, Fukushi M, Higuchi M, Oie M, Hoshi O, Ushiki T, Hayashi J, Fujii M. Chromosome binding site of latency-associated nuclear antigen of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus is essential for persistent episome maintenance and is functionally replaced by histone H1. J Virol. 2002;76(24):12917–24. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.24.12917-12924.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somech R, Amariglio N, Spirer Z, Rechavi G. Genetic predisposition to infectious pathogens: a review of less familiar variants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003;22(5):457–61. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000068205.82627.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Someya M, Sakata K, Matsumoto Y, Yamamoto H, Monobe M, Ikeda H, Ando K, Hosoi Y, Suzuki N, Hareyama M. The association of DNA-dependent protein kinase activity with chromosomal instability and risk of cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27(1):117–22. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava S, Verma M, Gopal-Srivastava R. Proteomic maps of the cancer-associated infectious agents. J Proteome Res. 2005;4(4):1171–80. doi: 10.1021/pr050017m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanyon CA, Bernard O. LIM-kinase1. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1999;31(3-4):389–94. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(98)00116-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor BJ, Reiman T, Pittman JA, Keats JJ, de Bruijn DR, Mant MJ, Belch AR, Pilarski LM. SSX cancer testis antigens are expressed in most multiple myeloma patients: co-expression of SSX1, 2, 4, and 5 correlates with adverse prognosis and high frequencies of SSX-positive PCs. J Immunother. 2005;28(6):564–75. doi: 10.1097/01.cji.0000175685.36239.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma SC, Borah S, Robertson ES. Latency-associated nuclear antigen of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus up-regulates transcription of human telomerase reverse transcriptase promoter through interaction with transcription factor Sp1. J Virol. 2004;78(19):10348–59. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.19.10348-10359.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma SC, Choudhuri T, Kaul R, Robertson ES. Latency-associated nuclear antigen (LANA) of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus interacts with origin recognition complexes at the LANA binding sequence within the terminal repeats. J Virol. 2006;80(5):2243–56. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.5.2243-2256.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma SC, Lan K, Robertson E. Structure and function of latency-associated nuclear antigen. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2007;312:101–36. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-34344-8_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma SC, Robertson ES. Molecular biology and pathogenesis of Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. FEMS Microbiology Letters. 2003;222(2):155–163. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00261-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warby S. Genes for Joubert syndrome: CEP290 is in the middle of it. Clin Genet. 2006;70(4):309–11. [Google Scholar]

- Yao X, Abrieu A, Zheng Y, Sullivan KF, Cleveland DW. CENP-E forms a link between attachment of spindle microtubules to kinetochores and the mitotic checkpoint. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2(8):484–91. doi: 10.1038/35019518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Mancini MA, Chang KH, Liu CY, Chen CF, Shan B, Jones D, Yang-Feng TL, Lee WH. Characterization of a novel 350-kilodalton nuclear phosphoprotein that is specifically involved in mitotic-phase progression. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15(9):5017–29. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.9.5017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]