Abstract

Drugs of abuse generate strong drug-context associations, which can evoke powerful drug cravings that are linked to reinstatement in animal models and to relapse in humans. Work in learning and memory has demonstrated that contextual memories become more distributed over time, shifting from dependence on the hippocampus for retrieval to dependence on cortical structures. Implications for such changes in the structure of memory retrieval to addiction are unknown. Thus, to determine if the passage of time alters the substrates of conditioned place preference (CPP) memory retrieval, we investigated the effects of inactivation of the dorsal hippocampus (DH) with the GABA-A receptor agonist muscimol on expression of recent or remote CPP. We compared these effects with the same manipulation on expression of contextual fear conditioning. DH inactivation produced similar deficits in expression of both recent and remote CPP, but blocked expression of recent but not remote contextual fear memory. We describe the implications of these findings for mechanisms underlying long-term storage of contextual information.

Keywords: Cocaine; Conditioned Place Preference; Fear Conditioning, Systems Consolidation; Muscimol

Introduction

A key finding from studies of substance abuse is that drug-conditioned contexts and cues generate strong cravings, even years after cessation [1–4]. A better understanding of the processes that support long-term maintenance of drug-associated memories may allow generation of targeted therapies to disrupt drug-context associations or facilitate extinction of drug-seeking [5]. While many compounds have shown promise in animal models of drugseeking [5–10], part of the problem may be translation from animal models to clinical populations. Many complex factors, such as number of drug administrations, environmental complexity, social factors, individual differences, and time since initial drug exposure, separate animal models of drug-seeking from human addiction [11].

A primary goal of drug abuse research is to develop animal models that are well matched to human drug addiction. In humans, addiction forms over months and years, whereas animal models of drug abuse generally acquire drug-seeking behavior on the order of days and weeks. This difference is compounded by associative learning models that predict that different neural substrates support expression of recent and remote memories [12]. Much of what is known about the ability to modulate drug-associated memories comes from the study of memories that have been recently acquired; much less is known about modulation of these memories after long retention intervals. Thus, age of drug-associated memories is one factor that could contribute to a mismatch between human addiction and animal models of substance abuse.

Many studies have demonstrated that memories that require the hippocampus for initial consolidation become less dependent on the hippocampus over time [13–17]. This observation has led to the idea of systems consolidation, where hippocampus-dependent memories become hippocampus-independent in the weeks following acquisition [12]. This effect has been most demonstrated in contextual fear conditioning, though it also occurs in other forms of hippocampus-dependent learning, such as trace fear conditioning [15, 16]. In each case, hippocampal disruption interferes with expression of recent but not remote memories. Systems consolidation is thought to support formation of long-lasting memories, since context learning in the absence of the hippocampus is less stable over time [18]. Although it is notable that systems consolidation effects can be difficult to replicate and are open to other interpretations [19–22], investigation of these processes may prove valuable, because similar time constraints have also been shown for reactivation-dependent impairments in memory [23, 24], an approach that has been applied to models of drug abuse treatment [25, 26]. Thus, understanding what tasks are affected by these processes may help identify clinical problems that could be treated by targeted disruption of particular consolidation mechanisms.

As systems consolidation is most reliably demonstrated in contextual fear learning [22], it is of interest to determine if hippocampus-dependent systems consolidation also occurs in other forms of contextual learning. In conditioned place preference, hippocampal structures have been implicated in acquisition of context-drug associations [27, 28]. However, it is not clear to what extent the hippocampus is involved in retrieval of a previously learned context-drug association, or if that involvement changes over time. Thus, we used cocaine-induced conditioned place preference (CPP) to determine if hippocampal involvement in context-drug memory retrieval changes over time. To investigate this, we used muscimol to inactivate the dorsal hippocampus (DH) of mice prior to testing for cocaine-induced CPP that was either 1 or 28 days old, time points regularly used to examine long-term memory consolidation [14, 17]. Additionally, we examined the effects of DH inactivation on expression of recent and remote contextual fear conditioning.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

These studies were conducted with 108 8–16 week old, male, C57BL6/J mice, which were singly housed with ad lib food and water and maintained on a 12 hr/12 hr light/dark cycle. All procedures were approved by the Oregon Health & Science University Animal Care and Use Committee and were in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the National Institutes for Health.

Drugs

Cocaine (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MS) was dissolved in saline and administered at 20 mg/kg ip, as described previously [8]. Muscimol (Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved in PBS and administered via bilateral, intra-cranial infusions into the DH (0.5 mg/side, in 0.25 ul, over 1m), as described previously [29].

Surgical Procedures

On Day 15 of behavioral procedures (CPP or Fear Conditioning) mice were implanted with intra-cranial cannula targeted towards the DH, see Raybuck & Lattal (2011) [29]. One caveat to this design that is common to all experiments examining the effects of time on behavior is that recent animals were trained prior to surgery, while remote animals were trained following surgery. However, since performance of vehicle animals did not change over time, it is unlikely that timing of surgical procedures was responsible for our present findings. Cannula placements were visualized with histological nissl staining with cresyl violet and verified by gliosis along infusion cannula tracts. All placements were within the DH (see Figure 2).

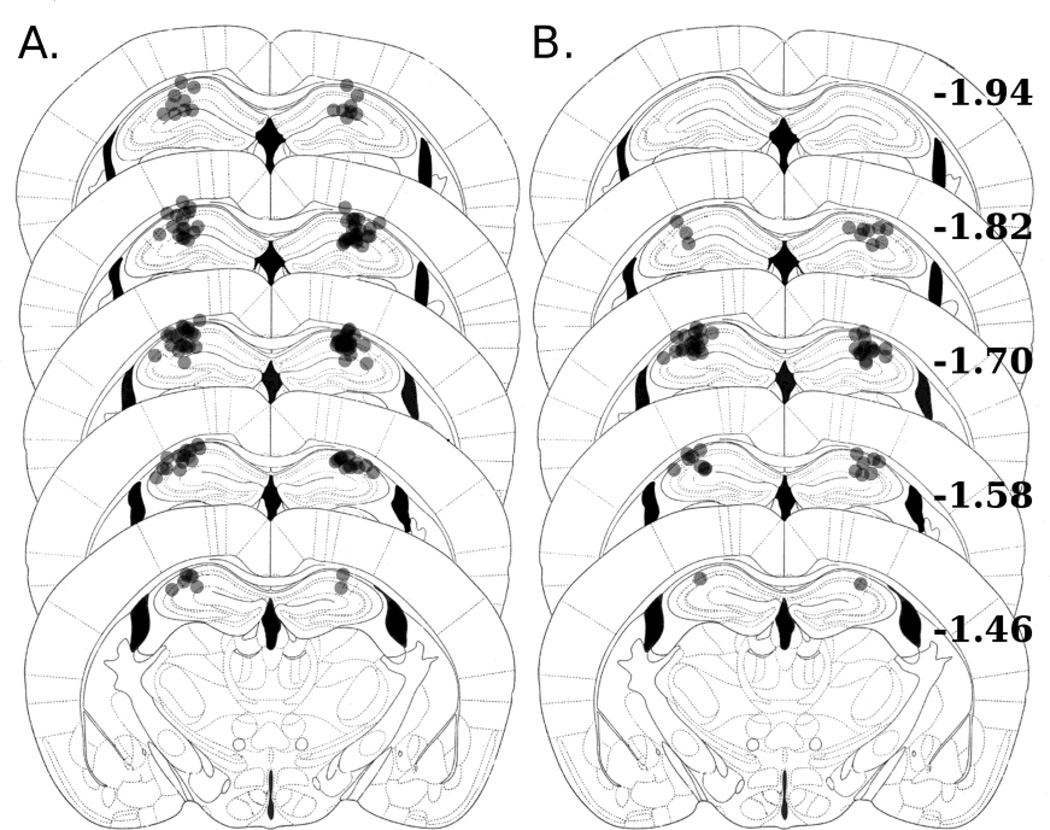

Figure 2.

Schematic representations of cannula placements in the DH. Though there were more subjects in the CPP experiment (A) than the fear conditioning (B) experiment, in both experiments all placements were within the DH and clustered around CA1 at Bregma −1.70. Individual placements are shown as dark circles with 50% opacity, allowing visualization of overall placement locations.

Behavioral Methods

Conditioned Place Preference

To determine if the hippocampal-dependence of CPP expression changes over time, mice were divided into two experimental groups (recent or remote). For each group, conditioning consisted of alternating exposures (15 min) to unique tactile floor cues (grid or hole floors). Prior to placement on a floor, mice received injection of cocaine (20 mg/kg) or saline, counterbalanced across floor types for a total of two pairings of floor with cocaine (CS+) and floor with saline (CS−); see [8, 31]. Mice in the remote training group received CPP training on Days 1–4, whereas mice in the recent training group received CPP training on Days 29–32. Importantly, drug exposure was matched such that during the remote training phase mice in the recent condition received cocaine administration in their home cages and vice versa. Thus, both recency of cocaine exposure and cocaine history were matched across training conditions. All animals were tested for CPP preference on Day 33, 20 minutes following infusion of muscimol or PBS. The preference test consisted of 15 min of simultaneous access to both tactile floor cues (CS+ and CS−).

Fear Conditioning

As a positive control, we also examined the effects of hippocampal inactivation on expression of contextual fear conditioning. Fear conditioning procedures were conducted as previously described [29]. Briefly, to generate sensitive levels of context learning, mice were trained in 2-pairing trace fear conditioning on either Day 1 or Day 28, then on Day 29 tested for context fear following muscimol infusion. Fear conditioning was trained with a 30 s 85 dB white noise CS and 2 s 0.5 mA US, and contextual conditioning was assessed with a 5 min exposure to the training context, for full description please see [29].

Analysis

Place preference (time on CS+) at testing was analyzed with 2-way ANOVA with training (Recent & Remote) and drug (Muscimol & Vehicle) as factors. Additionally, to examine effects of training and drug on locomotor activity during testing, distance traveled was also analyzed by 2-way ANOVA. Further analysis of preference data was conducted by t-test comparisons of time on grid floor between Grid + and Grid- conditioned mice within training and drug conditions. Analysis of fear conditioning data was similar to that of place preference, except that freezing during the 5-min context test was the dependent measure. All analysis was conducted with the open-source statistical program R using the Rcmdr package run with Rexcel, for current source code and instruction see [30].

Results

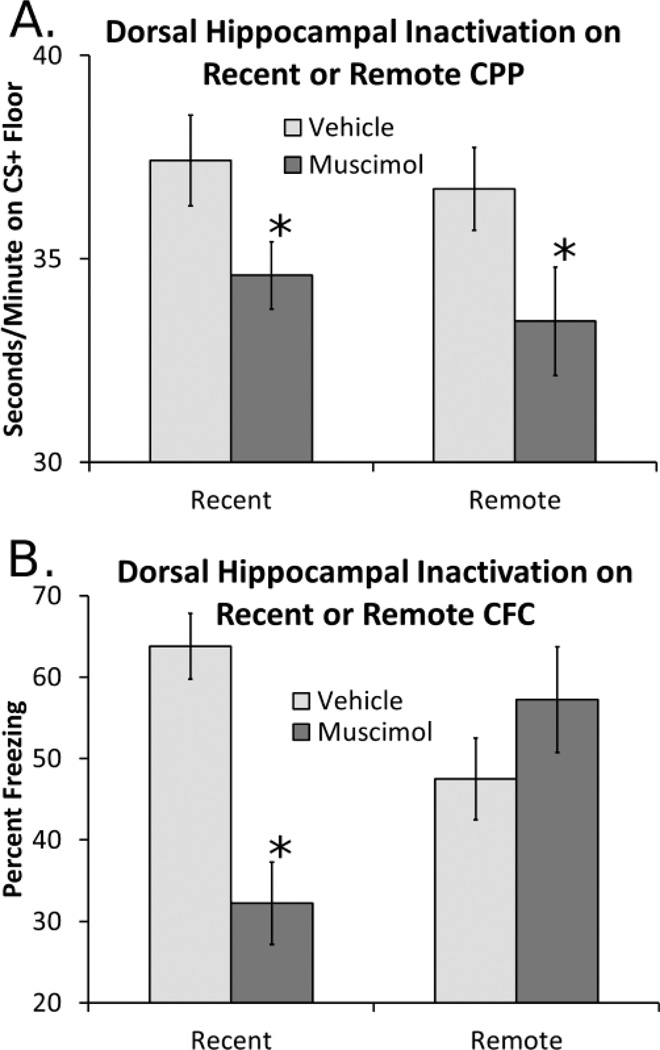

Inactivation of the DH with muscimol produced deficits in expression of cocaine-induced CPP regardless of whether training was recent or remote (Figure 1A). A two-way ANOVA revealed a main effect of muscimol infusion on place preference [F(1,77)=8.24, p<0.01], but no effect of time of training and no interaction. Additionally, examination of time on grid-floor in G+ and G− conditioning subgroups (reported as Mean, SEM) revealed that all groups showed significant place preference; Vehicle-Recent: [G+ 37.9, 1.5; G− 23.1, 1.8; t(22)=5.93, p<0.001]; Muscimol-Recent: [G+ 33.5, 1.1; G− 24.5,1.2; t(21)=4.95, p<0.001]; Vehicle-Remote: [G+ 38.1, 1.1; G− 24.4,1.6; t(17)=6.08, p<0.001]; Muscimol-Remote: [G+ 31.0,2; G− 24.0,1.5; t(17)=2.25, p<0.05]. Thus, although hippocampal inactivation produced deficits in CPP expression, muscimol-treated mice still showed conditioned preference. Though there were no significant differences in the effects of muscimol on preference (time on CS+) between recent and remote training groups, it is notable that of these groups the muscimol-remote mice showed the weakest preference (in terms of G+ vs G−), which may suggest that preference in the remote training group was more sensitive to hippocampal inactivation than the recent training group. Importantly, analysis of locomotor activity (distance traveled) showed no effects of training or muscimol on locomotion (Vehicle Recent 260.9, 11.4; Muscimol-Recent 286.4, 12.2; Vehicle-Remote 282.3, 12.5; Muscimol-Remote 292.8, 24.7; data are Mean, SEM of distance in cm traveled during testing). Additionally, there were no differences in cocaine-induced locomotor activity between training groups during training of CPP.

Figure 1.

Effects of DH inactivation on retrieval of recent of remote CPP and contextual fear conditioning. A). Inactivation of the DH with muscimol produces similar deficits in retrieval of cocaine-induced CPP regardless of training condition. Subjects per group were Recent-Vehicle, 23; Recent-Muscimol 22; Remote-Vehicle 18; Remote-Muscimol 18. B). In contextual fear conditioning inactivation of the DH produced selective deficits in retrieval of recent contextual fear without affecting remote memory. Subjects per group were Recent-Vehicle, 7; Recent- Muscimol 6; Remote-Vehicle 6; Remote-Muscimol 6. Data are mean ± the standard error of the mean, * denotes p<0.05.

Inactivation of the DH with muscimol produced training dependent deficits in expression of contextual fear conditioning (Figure 1B). A two-way ANOVA revealed a main effect of drug [F(1,23)=4.6, p<0.05] and a drug by training interaction [F(1,23)=18.6, p<0.001] on contextual fear conditioning. Post-hoc t-test comparisons showed that muscimol infusion produced significant deficits in expression of contextual fear conditioning in mice that had been trained one day before testing (Recent) [t(12)=5.2, p<0.001], but had no effect on contextual fear conditioning in mice that had been trained 28 days before testing (Remote). Additionally, examination within drug treatment conditioning showed that recent vehicle animals froze more in the recent conditioning than the remote conditioning [t(15)=2.6, p=0.02], and that there was also a significant difference between muscimol treated animals [t(12)=3.2, p=0.008].

Discussion

The present findings show that inactivation of the DH with muscimol infusion produces deficits in expression of CPP in mice trained either 1 or 28 days prior to CPP testing, whereas in mice trained for fear conditioning DH inactivation selectively blocked expression of recent contextual learning. Though this is the first investigation of the role of the DH in expression of remote CPP, the finding that cocaine induced-CPP expression is disrupted by hippocampal inactivation is in agreement with previous studies showing that DH lesions and inactivation block both acquisition and expression of cocaine induced-CPP [27, 28, 32–34]. However, the present effects of DH inactivation on contextual fear conditioning, though well supported [16, 17, 29], are in stark contrast to the effects on CPP. While it is notable that a recent report showed that optogenetic inactivation of the DH can have variable effects on retrieval of remote contextual fear [17], where extended optogenetic inactivation matched effects of pharmacological inactivation, the present findings suggest that similar effects do not occur in CPP.

There are multiple possibilities for effects of hippocampal inactivation on expression of CPP. Inactivating the hippocampus may disrupt retrieval of the context-drug memory or it may disrupt expression through effects on performance or motivation. For instance, it may temporarily disrupt the conditioned rewarding value of the cues associated with cocaine [35]. It also is possible that CPP memories become independent of the hippocampus with time, but the specific training and testing protocols used here may have resulted in contextual memories that fail to become hippocampus-independent. For instance, a key component of the CPP test is the presence of CS+ and CS− cues, whereas in contextual fear conditioning, the animal is tested only in the context previously associated with shock. In context discrimination tasks, effects of hippocampal manipulation on retrieval are similar regardless of memory age [36]. Thus, the context discrimination component of CPP may partly explain the present findings; however more work will be required to determine the mechanisms through which CPP retains hippocampus dependence. Another implication of the present finding is that time between acquisition of drugcue learning and retrieval is not a critical difference in models of addiction, such as CPP.

Learning and response strategies change with extended training, transitioning from response types that are hippocampus dependent to those that are hippocampus independent [37]. Therefore it is possible that in the present experiments additional training may have resulted in CPP memories that would not be affected by hippocampal inactivation. Although this would allow for hippocampus-independent drug memories to emerge over time, such a shift would not reflect systems consolidation, but rather altered response strategy. Thus, it is possible that over-trained CPP may depend on habit based responding. Though such work could shed important light on animal models of addiction, the unique role of drug-associated cues early in substance abuse, which critically contribute to the development of addiction [11, 38], may be lost with such an approach. Further research will be required determine if hippocampus-independent CPP can be achieved by more extensive training.

Finally, there are clinical implications for this demonstration that drug-associated memories may maintain their hippocampus-dependence across long retention intervals. Behavioral therapies for substance abuse are often designed to weaken the ability of cues to evoke drug cravings, which may lead to relapse. In contrast to fear, the present findings that both recent and remote drug-associated memories are disrupted by hippocampal inactivation suggest that drug-context associations have a different temporal response than context-fear associations in terms of hippocampal involvement. Thus, it may be feasible to develop behavioral and pharmacological strategies that target hippocampus-dependent memories long after they have been established.

Conclusions

The present findings demonstrate that cocaine-CPP has a different temporal profile for DH dependence than contextual fear conditioning. While these findings may be important for the development of drug-context based interventions, such as, pharmacologically enhanced extinction [8–10] and re-exposure based enhancement of extinction [25, 26], further research will be required to determine which of a number of factors described above are responsible for the present effects.

Highlights.

Systems consolidation predicts that retrieval of remote memories can occur independent of the hippocampus.

Hippocampal inactivation impairs expression of recent and remote cocaine CPP, but only affects only recent contextual fear.

We discuss models of substance abuse and issues in the translation of memory mechanisms to clinical therapies.

Acknowledgments

Grant sponsor: NIDA, NIMH

Grant number: R01DA025922 KML, RO1MH077111 KML, T32DA007262 F32DA031537 JDR

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Penberthy JK, Ait-Daoud N, Vaughan M, Fanning T. Review of treatment for cocaine dependence. Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 2010;3:49–62. doi: 10.2174/1874473711003010049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O'Brien CP, Childress AR, Ehrman R, Robbins SJ, et al. Conditioning factors in drug abuse: can they explain compulsion? J. Psychopharmacol. (Oxford) 1998;12:15–22. doi: 10.1177/026988119801200103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koob GF, Volkow ND. Neurocircuitry of addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:217–38. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dutra L, Stathopoulou G, Basden SL, Leyro TM, Powers MB, Otto MW. A meta-analytic review of psychosocial interventions for substance use disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:179–87. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06111851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Milton A. Drink, drugs and disruption: memory manipulation for the treatment of addiction. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2012.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalivas PW, Volkow ND. New medications for drug addiction hiding in glutamatergic neuroplasticity. Mol. Psychiatry. 2011;16:974–86. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reichel CM, See RE. Chronic N-acetylcysteine after cocaine self-administration produces enduring reductions in drug-seeking. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37:298. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raybuck JD, McCleery EJ, Cunningham CL, Wood MA, Lattal KM. The histone deacetylase inhibitor sodium butyrate modulates acquisition and extinction of cocaine-induced conditioned place preference. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2013;106:109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2013.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malvaez M, Sanchis-Segura C, Vo D, Lattal KM, Wood MA. Modulation of chromatin modification facilitates extinction of cocaine-induced conditioned place preference. Biol. Psychiatry. 2010;67:36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Malvaez M, McQuown SC, Rogge GA, Astarabadi M, Jacques V, Carreiro S, et al. HDAC3-selective inhibitor enhances extinction of cocaine-seeking behavior in a persistent manner. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2013;110:2647–2652. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1213364110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bardo MT, Bevins RA. Conditioned place preference: what does it add to our preclinical understanding of drug reward? Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 2000;153:31–43. doi: 10.1007/s002130000569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frankland PW, Bontempi B. The organization of recent and remote memories. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2005;6:119–130. doi: 10.1038/nrn1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dash PK, Hebert AE, Runyan JD. A unified theory for systems and cellular memory consolidation. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 2004;45:30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anagnostaras SG, Maren S, Fanselow MS. Temporally graded retrograde amnesia of contextual fear after hippocampal damage in rats: within-subjects examination. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:1106–1114. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-03-01106.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quinn JJ, Ma QD, Tinsley MR, Koch C, Fanselow MS. Inverse temporal contributions of the dorsal hippocampus and medial prefrontal cortex to the expression of long-term fear memories. Learn. Mem. 2008;15:368–372. doi: 10.1101/lm.813608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beeman CL, Bauer PS, Pierson JL, Quinn JJ. Hippocampus and medial prefrontal cortex contributions to trace and contextual fear memory expression over time. Learn. Mem. 2013;20:336–343. doi: 10.1101/lm.031161.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goshen I, Brodsky M, Prakash R, Wallace J, Gradinaru V, Ramakrishnan C, et al. Dynamics of retrieval strategies for remote memories. Cell. 2011;147:678–689. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zelikowsky M, Bissiere S, Fanselow MS. Contextual fear memories formed in the absence of the dorsal hippocampus decay across time. J. Neurosci. 2012;32:3393–3397. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4339-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wiltgen BJ, Tanaka KZ. Systems consolidation and the content of memory. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wiltgen BJ, Zhou M, Cai Y, Balaji J, Karlsson MG, Parivash SN, et al. The hippocampus plays a selective role in the retrieval of detailed contextual memories. Curr. Biol. 2010;20:1336–1344. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.06.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moscovitch M, Rosenbaum RS, Gilboa A, Addis DR, Westmacott R, Grady C, et al. Functional neuroanatomy of remote episodic, semantic and spatial memory: a unified account based on multiple trace theory. J. Anat. 2005;207:35–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2005.00421.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sutherland RJ, Lehmann H. Alternative conceptions of memory consolidation and the role of the hippocampus at the systems level in rodents. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2011;21:446–451. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2011.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inda MC, Muravieva EV, Alberini CM. Memory retrieval and the passage of time: from reconsolidation and strengthening to extinction. J. Neurosci. 2011;31:1635–1643. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4736-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Milekic MH, Alberini CM. Temporally graded requirement for protein synthesis following memory reactivation. Neuron. 2002;36:521–525. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00976-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Otis JM, Dashew KB, Mueller D. Neurobiological dissociation of retrieval and reconsolidation of cocaine-associated memory. J. Neurosci. 2013;33:1271–1281a. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3463-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Otis JM, Mueller D. Inhibition of β-adrenergic receptors induces a persistent deficit in retrieval of a cocaine-associated memory providing protection against reinstatement. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:1912–20. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meyers RA, Zavala AR, Speer CM, Neisewander JL. Dorsal hippocampus inhibition disrupts acquisition and expression, but not consolidation, of cocaine conditioned place preference. Behav. Neurosci. 2006;120:401–412. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.120.2.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meyers RA, Zavala AR, Neisewander JL. Dorsal, but not ventral, hippocampal lesions disrupt cocaine place conditioning. Neuroreport. 2003;14:2127–2131. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200311140-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raybuck JD, Lattal KM. Double dissociation of amygdala and hippocampal contributions to trace and delay fear conditioning. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e15982. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baier T, Neuwirth E. Excel :: COM :: R. Computational Statistics. 2007;22/1:91–108. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cunningham CL, Gremel CM, Groblewski PA. Drug-induced conditioned place preference and aversion in mice. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:1662–1670. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zarrindast M, Lashgari R, Rezayof A, Motamedi F, Nazari-Serenjeh F. NMDA receptors of dorsal hippocampus are involved in the acquisition, but not in the expression of morphine-induced place preference. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2007;568:192–198. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rezayof A, Razavi S, Haeri-Rohani A, Rassouli Y, Zarrindast M. GABA(A) receptors of hippocampal CA1 regions are involved in the acquisition and expression of morphine-induced place preference. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2007;17:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zarrindast M, Massoudi R, Sepehri H, Rezayof A. Involvement of GABA(B) receptors of the dorsal hippocampus on the acquisition and expression of morphine-induced place preference in rats. Physiol. Behav. 2006;87:31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bernardi RE, Ryabinin AE, Berger SP, Lattal KM. Post-retrieval disruption of a cocaine conditioned place preference by systemic and intrabasolateral amygdala beta2- and alpha1- adrenergic antagonists. Learn Mem. 2009;16:777–789. doi: 10.1101/lm.1648509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang S, Teixeira CM, Wheeler AL, Frankland PW. The precision of remote context memories does not require the hippocampus. Nat. Neurosci. 2009;12:253–5. doi: 10.1038/nn.2263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Packard MG, McGaugh JL. Inactivation of hippocampus or caudate nucleus with lidocaine differentially affects expression of place and response learning. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 1996;65:65–72. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1996.0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vanderschuren LJMJ, Pierce RC. Sensitization processes in drug addiction. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2010;3:179–95. doi: 10.1007/7854_2009_21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]