Abstract

Connective tissue growth factor (Ctgf) or CCN2 is a protein synthesized by osteoblasts necessary for skeletal homeostasis, although its overexpression inhibits osteogenic signals and bone formation. Ctgf is induced by bone morphogenetic proteins, transforming growth factor β and Wnt; and in the present studies, we explored whether Notch regulated Ctgf expression in osteoblasts. We employed RosaNotch mice, where the Notch intracellular domain (NICD) is expressed following the excision of a STOP cassette, placed between the Rosa26 promoter and NICD. Notch was activated by transduction of adenoviral vectors expressing Cre recombinase (Ad-CMV-Cre). Notch induced Ctgf mRNA levels in a time dependent manner and increased Ctgf heterogeneous nuclear RNA. Notch also destabilized Ctgf mRNA shortening its half-life from 13 h to 3 h. The effect of Notch on Ctgf expression was lost following Rbpjκ downregulation, demonstrating that it was mediated by Notch canonical signaling. However, downregulation of the classic Notch target genes Hes1, Hey1 and Hey2 did not modify the effect of Notch on Ctgf expression. Wild type osteoblasts exposed to immobilized Delta-like 1 displayed enhanced Notch signaling and increased Ctgf expression. In addition to the effects of Notch in vitro, Notch induced Ctgf in vivo, and calvariae and femurs from RosaNotch mice mated with transgenics expressing the Cre recombinase in cells of the osteoblastic lineage exhibited increased expression of Ctgf. In conclusion, Ctgf is a target of Notch canonical signaling in osteoblasts, and may act in concert with Notch to regulate skeletal homeostasis.

Keywords: Notch, CCN proteins, connective tissue growth factor, osteoblasts, transcription

1. INTRODUCTION

The fate of mesenchymal cells and their differentiation toward cells of the osteoblastic lineage is tightly controlled by extracellular and intracellular signals [1–6]. A critical regulatory component of cell differentiation and function is provided by families of proteins that modulate the extracellular signals that target cells of the osteoblastic lineage. These regulatory proteins can bind growth factors directly or modify growth factor-receptor interactions, and frequently act as growth factor antagonists. These proteins include insulin-like growth factor binding proteins (IGFBP), bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) and Wnt antagonists, as well as members of the Cyr61, connective tissue growth factor (Ctgf) and nephroblastoma overexpressed (Nov) (CCN) family of proteins [1, 4, 7, 8]. CCN proteins are highly conserved, and are structurally related to IGFBPs, and to certain BMP antagonists, such as twisted gastrulation and chordin, and can interact with regulators of osteoblast cell growth and differentiation [4, 9, 10].

Ctgf or CCN2 is a protein synthesized by chondrocytes, osteoblasts and osteocytes. In osteoblasts, Ctgf expression is induced by BMP, transforming growth factor β and Wnt [11–13]. Ctgf regulates different cellular functions, including cell adhesion, proliferation, migration and differentiation [14, 15]. The effects of Ctgf on osteoblast differentiation and function depend on its interactions with local regulatory signals, the concentration of Ctgf in the bone environment and the stage of osteoblast differentiation [16–19]. Ctgf is necessary for chondrogenesis and osteoblastogenesis, but when in excess Ctgf is inhibitory since it tempers the effects of osteogenic signals in the skeleton [16, 17, 20, 21]. Studies performed by our laboratory revealed that the overexpression of Ctgf under the control of the osteocalcin/bone gamma carboxyglutamate protein (Bglap) promoter causes osteopenia by decreasing bone formation, an effect attributed to suppressed BMP, Wnt and IGFI signaling [17]. Similarly, Ctgf overexpression in chondrocytes causes bone loss [22]. Targeted disruption of Ctgf in mice leads to severe skeletal developmental abnormalities, as a result of impaired cartilage/bone development [21, 23]. We demonstrated that the conditional inactivation of Ctgf in the limb bud or in differentiated osteoblasts results in osteopenia, confirming its direct role in skeletal development, and demonstrating that Ctgf is necessary for adult skeletal homeostasis [20].

Notch signaling plays a critical role in osteoblast cell fate and function, and is activated following interactions with specific ligands of the Delta-like (Dll) and Jagged families [3, 6]. Notch-ligand interactions result in the proteolytic cleavage of the Notch receptor and the release and translocation of the Notch intracellular domain (NICD) to the nucleus, where it forms a complex with CSL (for CBF1, suppressor of hairless and Lag1), also termed Rbpjκ, and with Mastermind [24, 25]. This is known as the Notch canonical signaling pathway and results in the expression of the classic Notch target genes Hairy and Enhancer of Split (Hes) and Hes-related with an YRPW motif (Hey) [26]. However, it is not known whether other genes are targeted by Notch signaling in osteoblasts.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the direct effects of Notch signaling on Ctgf expression in osteoblasts from the RosaNotch mouse model, where a STOP cassette, placed between the Rosa26 promoter and the Notch1 NICD coding sequence, is flanked by loxP sites [27, 28]. Notch was activated in RosaNotch osteoblasts by the transduction of adenoviral vectors expressing the Cre recombinase [29, 30]. In addition, Ctgf expression was studied in vivo by obtaining calvariae and femurs from RosaNotch mice crossed with transgenics expressing the Cre recombinase under the control of the Osterix (Osx), the Bglap (Osteocalcin), the 2.3 kb fragment of Col1a1 (Col2.3) or the Dentin matrix protein1 (Dmp1) promoter [31–34].

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 RosaNotch Conditional Mice

RosaNotch mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) in a 129SvJ/C57BL/6 genetic background [27, 28]. Homozygous RosaNotch mice were used as a source of calvarial osteoblasts or were bred with heterozygous mice expressing Cre under the control of the Osx (Osx-Cre), the Bglap (Bglap-Cre), the Col1a1 (Col2.3-Cre) or the Dmp1 promoter (Dmp1-Cre) [33, 35–37]. All transgenics were in a C57BL/6 genetic background, but the Col2.3-Cre, which were in a tropism to friend leukemia virus type B (FVB) background. All mating schemes created Cre+/−;RosaNotch experimental and RosaNotch littermate controls, as described [38]. In the Osx-Cre transgenics, the expression of Cre is under the control of a tet-off cassette, and RosaNotch pregnant dams were treated with a diet containing 625 mg of doxycycline hyclate/kg of chow to deliver 2 to 3 mg of doxycycline daily from the time of conception to delivery (Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN). Osx-Cre, Bglap-Cre, Col2.3-Cre and Dmp1-Cre were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory, T. Clemens (Baltimore, MD), the Mutated Mouse Regional Resource Center (Davis, CA) and J. Fang (Dallas, TX), respectively [33, 35–37]. Genotyping was carried out by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in tail DNA extracts, and deletion of the loxP flanked STOP cassette by the Cre recombinase was documented by PCR in DNA from tibiae, as previously reported [38]. The induction of Notch in the skeleton was confirmed by documenting enhanced Notch1 NICDHes1, Hey1 and Hey2 mRNA expression in calvarial extracts by quantitative reverse transcription (qRT)-PCR, as reported previously [38]. All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Saint Francis Hospital and Medical Center.

2.2 Cell Cultures

Osteoblast-enriched cells were isolated by sequential collagenase digestion from parietal bones of 3–5 day old RosaNotch mice or wild-type C57BL/6 mice, as described [39]. Osteoblasts from homozygous RosaNotch mice were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY), supplemented with nonessential amino acids (Life Technologies), 20 mM HEPES, 100 μg/ml ascorbic acid (both from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Atlanta Biologicals, Norcross, GA) at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. When RosaNotch osteoblast cultures reached 70% confluence, they were transferred to medium containing 2% FBS for 1 h and exposed overnight to 100 multiplicity of infection of replication defective recombinant adenoviruses. An adenoviral vector expressing Cre recombinase under the control of the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter (Ad-CMV-Cre, Vector Biolabs, Philadelphia, PA) was delivered to RosaNotch cells to induce recombination of the loxP sequences and NICD expression [40]. An adenoviral vector expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP) under the control of the CMV promoter (Ad-CMV-GFP, Vector Biolabs) was used as control. In one experiment, osteoblast enriched cells were obtained from Bglap-Cre+/−;RosaNotch mice, to induce loxP recombination and excision of the STOP cassette in vivo, and RosaNotch controls and cultured as described. Notch receptors can be activated by Notch ligands adherent to the cell culture substrate [41]. For this purpose, cell culture plates were exposed to the Notch ligand Dll1 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 1 h at room temperature to immobilized Dll1. Bovine serum albumin (BSA, Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS at a concentration of 500 ng/ml was used as a control. Wild type C57BL/6 osteoblasts were seeded on immobilized Dll1 or BSA and cultured in DMEM as described for osteoblasts from RosaNotch mice.

2.3 RNA Decay Experiments

The effects of Notch on the stability of Ctgf mRNA were assessed in RosaNotch osteoblasts transduced with Ad-CMV-Cre or Ad-CMV-GFP, grown for 72 h after reaching confluence and exposed to 75 μm 5,6-dichloro-1-β-D-ribofuranosylbenzimidazole (DRB, BioMol, Plymouth Meeting, PA) to arrest transcription [42]. Total RNA was extracted and subjected to qRT-PCR analysis to determine Ctgf mRNA levels following different times of exposure to DRB. To establish the slopes of Ctgf mRNA decay, Ctgf copy numbers corrected for Rpl38 transcript levels, expressed as a percentage of the corrected Ctgf mRNA levels measured before exposure to DRB, were transformed by a base 10 logarithmic function and fitted against time by linear regression.

2.4 RNA Interference (RNAi)

To downregulate Rbpjκ, Hes1, Hey1 and Hey2 in RosaNotch osteoblasts transduced with Ad-CMV-Cre or Ad-CMV-GFP, 19-mer double-stranded small interfering (si) RNAs targeted to the murine Rbpjκ (siRNA Id: S72811), Hes1 (siRNA Id: 158034), Hey1 (siRNA Id: 158942) or Hey2 (siRNA Id: 159333) mRNA sequences were obtained commercially (Life Technologies) [43]. A scrambled 19-mer siRNA with no homology to known mouse sequences was used as control. Rbpjκ, Hes1, Hey1 and Hey2 or scrambled siRNA at 20 nM were transfected into 60–70% confluent osteoblasts using siLentFect lipid reagent, in accordance with manufacturer’s instructions (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). To test for the effects of Rbpjκ, Hes or Hey downregulation on Ctgf expression, Ctgf mRNA or heterogeneous nuclear (hnRNA) were determined by qRT-PCR 72 h following the transfection of siRNAs. To ensure adequate downregulation, Rbpjκ, Hes1, Hey1 and Hey2 mRNA levels were determined.

2.5 Reverse Transcription – Polymerase Chain Reaction

Total RNA was extracted from cell layers, calvariae or femurs, following removal of bone marrow stromal cells by centrifugation, with the RNeasy mini kit, according to manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Changes in mRNA and hnRNA levels were determined by qRT-PCR [44, 45]. 0.5–1 μg of total RNA was reverse transcribed using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad) according to manufacturer’s instructions and amplified in the presence of specific primers (Table 1) and iQ SYBR Green supermix (Bio-Rad) at 60°C for 35 cycles. cDNA copy number was estimated by comparison with a standard curve constructed using Ctgf (from Rolf-Peter Rysek, Princeton, NJ), Hes1 (from American Type Culture Collection, ATCC, Manassas, VA), Hey1, Hey2 (both from T. Iso, Los Angeles, CA) and Rbpjκ (from Thermo Scientific, Lafayette, CO) cDNAs and corrected for ribosomal protein l38 (Rpl38) or glyceraldehydes-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gapdh) expression, estimated by comparison with serial dilutions of cDNA for either Rpl38 (ATCC) or Gapdh (R. Wu, Ithaca, NY) [46–50]. Amplification reactions were conducted in a CFX96 real time system (Bio-Rad). To assess Ctgf hnRNA levels, 0.5μg of total RNA were reverse-transcribed in the presence of a specific antisense primer targeted to the junction between intron 2 and exon 3 of Ctgf and amplified, as described for mRNA. Amplification efficiency was estimated by comparison with a standard curve generated by parallel amplification of a dilution series of genomic murine DNA, and Ctgf hnRNA was normalized to Rpl38 expression [51]. Fluorescence was monitored during every PCR cycle at the annealing step, and specificity of the reaction was confirmed by the presence of a single peak in the melt curve analysis of PCR products.

Table 1.

Primers used for qRT-PCR assay determinations. GenBank accession number identifies transcript recognized by primer pairs.

| qRT-PCR | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Strand | Sequence 5'–3' | GenBank Accession Number |

| Ctgf mRNA | Forward | CTGCCTGGGAAATGCTGCGAGGAGT | NM_010217 |

| Reverse | GTTGGGTCTTGGGCCAAATGT | ||

| Ctgf hnRNA | Forward | ACCCTACGCCTGACCTACAA | NC_000076 |

| Reverse | CATCTTTGGCTGCGGGAGAG | ||

| Gapdh | Forward | CCCCTCTGGAAAGCTGTGGCGT | NM_008084 |

| Reverse | AGCTTCCCGTTCAGCTCTGG | ||

| Hes1 | Forward | ACCAAAGACGGCCTCTGAGCACAGAAAGT | NM_008235 |

| Reverse | ATTCTTGCCCTTCGCCTCTT | ||

| Hey1 | Forward | ATCTCAACAACTACGCATCCCAGC | NM_010423 |

| Reverse | GTGTGGGTGATGTCCGAAGG | ||

| Hey2 | Forward | AGCGAGAACAATTACCCTGGGCAC | NM_013904 |

| Reverse | GGTAGTTGTCGGTGAATTGGACCT | ||

| Rbpjκ | Forward | ACAGACAAGGCAGAATACAC | NM_001080928 |

| NM_009035 | |||

| Reverse | CAACTGAAGACTTTCTACGA | NM_001080927 | |

| Rpl38 | Forward | AGAACAAGGATAATGTGAAGTTCAAGGTTC | NM_001048057 |

| NM_023372 | |||

| Reverse | CTGCTTCAGCTTCTCTGCCTTT | NM_001048058 | |

2.6 Constructs and Transfections

To study effects of Notch on Notch transactivation and Ctgf promoter activity, a construct containing six multimerized dimeric CSL binding sites, linked to the β-globin basal promoter (12xCSL-Luc; L. J. Strobl, Munich, Germany) or a 3.8 kilobase (kb) fragment of the Ctgf promoter (Ctgf-Luc; Bruce Kone, Houston, TX) cloned upstream of luciferase were transfected into RosaNotch cells transduced with Ad-CMV-Cre or Ad-CMV-GFP vectors [52, 53]. To verify these effects, osteoblasts from wild type C57BL/6 mice were co-transfected with the described constructs and a construct expressing the Notch1 cloned into pcDNA3.1 (pcDNA-NICD) or control vector [54]. To determine whether the 3' untranslated region (3'UTR) of Ctgf was a target of Notch, the Ctgf 3'UTR was cloned into the CMV promoter driven luciferase reporter pMIR.Target (Blue Heron Biotech, Bothel, WA). pMIR.Target and pMIR-Ctgf 3'UTR were transfected into Ad-CMV-Cre and Ad-CMV-GFP control transduced RosaNotch cells. All transfections were conducted in cells cultured to 70% confluence using X-tremeGENE 9 DNA Transfection Reagent (3 μl X-tremeGENE 9/2 μg of DNA), according to manufacturer’s instructions (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN). A CMV-directed β-galactosidase expression construct (Clontech, Mountain View, CA) was used to control for transfection efficiency. All cells were exposed to the X-tremeGENE 9/DNA mixture for 16 h, transferred to fresh medium for 24 h, and harvested. Luciferase and β-galactosidase activities were measured using an Optocomp luminometer (MGM Instruments, Hamden, CT). Luciferase activity was corrected for β-galactosidase activity.

2.7 Ctgf Enzyme-linked Immune Absorbent Assay (ELISA)

Murine Ctgf was measured by ELISA in culture medium from RosaNotch osteoblasts and from wild type osteoblasts plated on BSA or Dll1 coated plates and in serum from Cre+/−;RosaNotch and control mice using a commercially available kit in accordance with manufacturer’s instructions (Uscn Life Science Inc., Wuhan, Hubei, China)

2.8 Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as means ± SEM. Statistical differences were determined by Student’s t test or analysis of variance with Schaffés post hoc analysis for pairwise or multiple comparisons. Statistical differences for the slopes of mRNA decay were analyzed by analysis of covariance [55].

3. RESULTS

3.1 Effects of Notch on the Expression of Ctgf in Osteoblasts

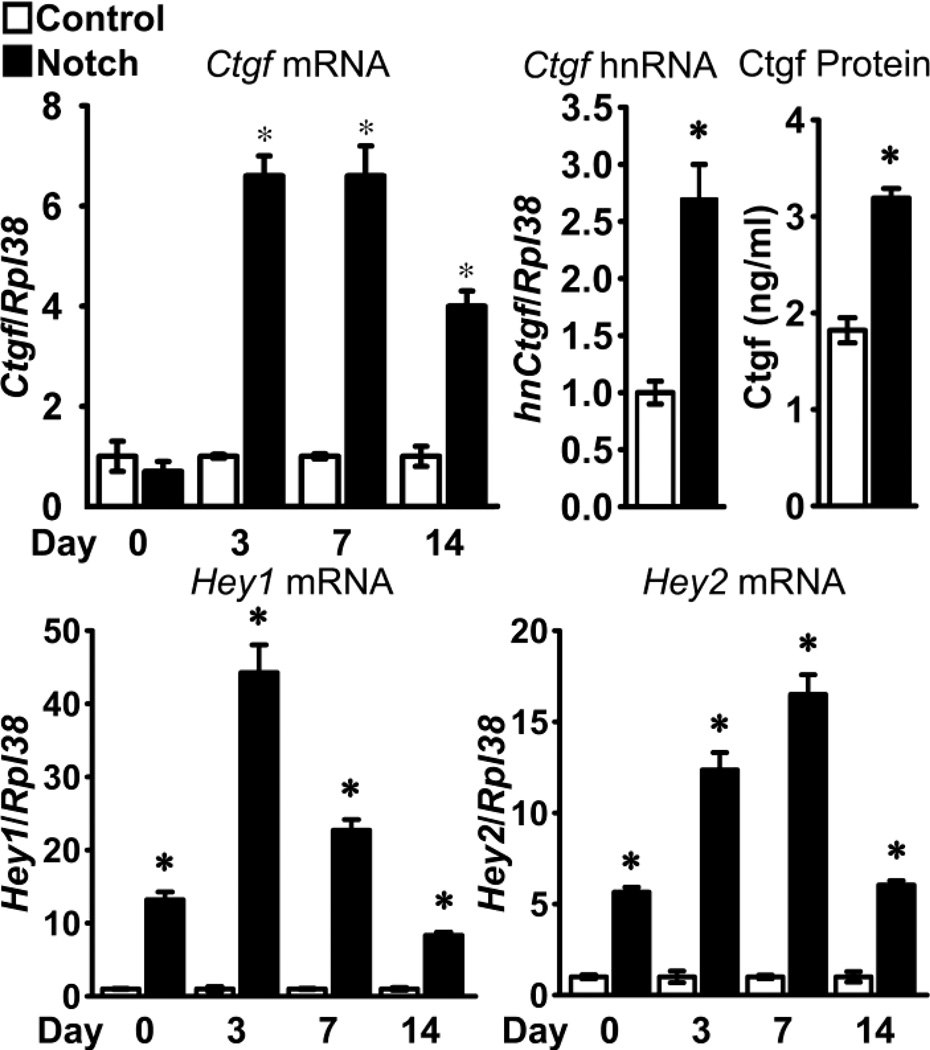

The effects of Notch on the expression of Ctgf were tested in primary calvarial osteoblast cultures from RosaNotch mice transduced with Ad-CMV-Cre, to excise the loxP flanked STOP cassette and allow NICD expression under the control of the Rosa26 promoter, or with control Ad-CMV-GFP. Notch activation was previously confirmed by demonstration of increased Notch1 NICD, Hey1 and Hey2 mRNA expression and enhanced transactivation of Notch reporter constructs [40]. Notch increased Ctgf mRNA levels in a time dependent manner. Notch induced Ctgf transcripts 3 days after the cells reached confluence and the effect was sustained for 2 weeks (Figure 1, upper left panel). Notch increased Ctgf hnRNA levels by 2.7 fold, indicating that Notch enhances Ctgf transcription (Figure 1, upper middle panel). The induction of Ctgf transcripts by Notch was translated into a ~2 fold increase in Ctgf protein levels (Figure 1, upper right panel). The induction of Ctgf expression was concomitant with the induction of the canonical Notch target genes Hey1 and Hey2 (Figure 1, lower panel). Consistent with the known decline of adenoviral vector activity, the induction of Hey1 and Hey 2 was more prominent in the early phases in the culture. There was minimal effect of the transduced adenoviral vector on Ctgf mRNA levels. In an experiment where Notch activation induced Ctgf mRNA 7.5 fold, there was little difference in Ctgf mRNA levels between non-transduced RosaNotch osteoblasts, Ad-CMV-GFP-transduced RosaNotch cells and wild type osteoblasts. Ctgf/Rpl38 copy number (values means ± SEM; n = 4) was 0.14 ± 0.1 in wild type osteoblasts; 0.24 ± 0.1 in non-transduced RosaNotch osteoblasts; 0.20 ± 0.1 in Ad-CMV-GFP-transduced; and 1.5 ± 0.1 in Ad-CMV-Cre-transduced RosaNotch cells.

Figure 1.

Effect of Notch on Hey1, Hey2 (lower panel) and Ctgf (upper left panel) mRNA, Ctgf hnRNA (upper middle panel) and Ctgf protein (upper right panel) expression in osteoblasts. Calvarial osteoblasts isolated from RosaNotch mice were transduced with Ad-CMV-Cre, to activate Notch (black bars), or control Ad-CMV-GFP (white bars) and cultured to confluence (day 0) or up to 2 weeks following confluence. Samples for hnRNA and protein determination were obtained 3 days post-confluence. Total RNA was extracted, reversed transcribed and amplified by qRT-PCR. Data for mRNA and hnRNA are expressed as Ctgf, Hey1 and Hey2 copy number corrected for Rpl38 expression relative to the mRNA or to the Ctgf hnRNA expression in Ad-CMV-GFP control cells, arbitrarily set at a value of 1. Data for Ctgf protein, measured by ELISA, are expressed as ng/ml of culture medium. Data for Ctgf, Hey1 and Hey2 mRNA were pooled from 2 experiments. Values are means ± SEM; n = 4. *Significantly different between Ad-CMV-Cre Notch activated cells and control, p < 0.05.

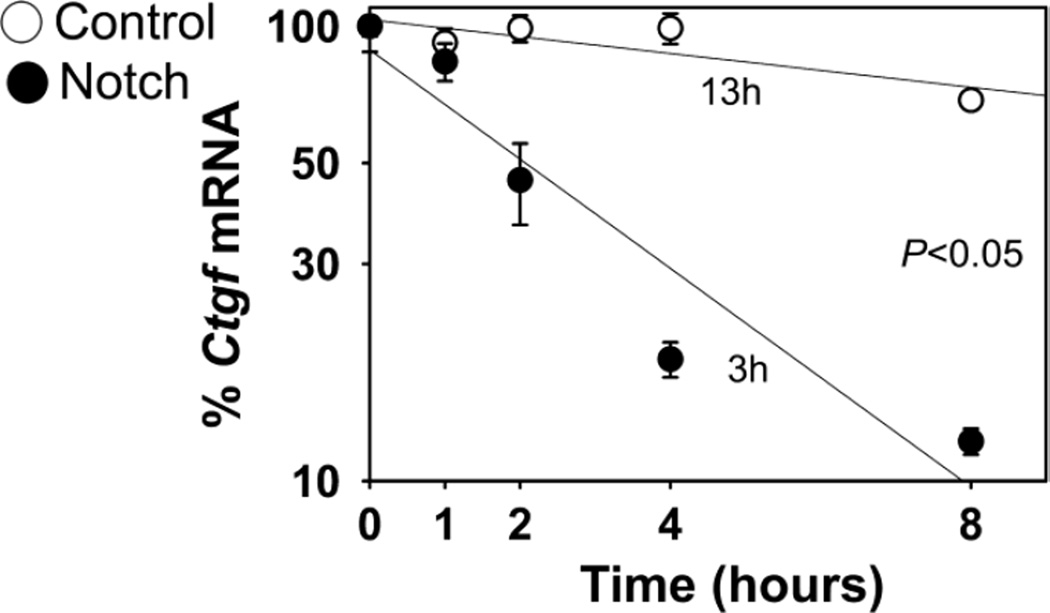

Although Notch induced Ctgf mRNA and hnRNA levels, the effect occurred 3 days after the cells reached confluence, suggesting possible indirect effects on Ctgf transcription. Indeed, in acute transfection experiments conducted in transduced RosaNotch osteoblasts, Notch enhanced the transactivation of the Notch reporter construct 12xCSL-Luc, but failed to enhance the activity of a 3.8 kb fragment of the Ctgf promoter directing luciferase activity (Table 2A). Similar results were observed when wild type osteoblasts were co-transfected with pcDNA-NICD expression constructs and either 12xCSL-Luc or the Ctgf-Luc promoter fragment, confirming that Notch did not enhance the transactivation of the Ctgf promoter fragment tested (Table 2B). In both experiments, a modest decrease in Ctgf promoter activity was noted. To determine whether Notch also regulated Ctgf expression by post-transcriptional mechanisms, the decay of Ctgf transcripts was assessed in RosaNotch osteoblasts transcriptionally arrested with DRB 3 days after the cells reached confluence. The half-life of Ctgf mRNA was 13 h in control cultures, and unexpectedly Notch shortened the half-life of Ctgf mRNA to 3 h, demonstrating that Notch destabilizes Ctgf transcripts, and confirming that Notch increased Ctgf mRNA exclusively by transcriptional mechanisms (Figure 2). To explore further the effect of Notch on Ctgf mRNA stability, pMIR-Ctgf 3'UTR constructs were transfected into RosaNotch osteoblasts transduced with Ad-CMV-Cre or control vector. Notch decreased the activity of the pMIR-Ctgf 3'UTR reporter by 85% indicating that the 3'UTR, a region containing sequences that often confer transcript stability, is a target of Notch, offering a potential mechanism for the destabilization of Ctgf mRNA by Notch signaling (Table 2C) [56].

Table 2.

Effect of Notch on the activity of Ctgf promoter and pMIR-Ctgf 3'UTR constructs.

| 12xCSL-Luc | 3.8 kb Ctgf-Luc | |

|---|---|---|

| Luciferase/β-galactosidase | ||

| A. | ||

| Control | 0.4 ± 0.4 | 1854 ± 250 |

| Notch | 19.7 ± 7.5* | 1489 ± 393 |

| B. | ||

| Control | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 190 ± 9 |

| pcDNA-NICD | 127 ± 15 | 141 ± 18* |

|

pMIR-Ctgf 3'UTR Luciferase/β-galactosidase |

||

| C. | ||

| Control | 1637 ± 219 | |

| Notch | 232 ± 22* | |

Calvarial osteoblasts isolated from RosaNotch mice were transduced with Ad-CMV-Cre (Notch) or Ad-CMV-GFP (Control) and transfected in A. with a 12xCSL-Luc reporter or a 3.8 kb Ctgf-Luc promoter construct and in C. with pMIR-Ctgf 3'UTR reporter. In B. wild type osteoblasts were co-transfected with pcDNA-NICD expression construct or control pcDNA3.1 and 12xCSL-Luc or Ctgf-Luc promoter fragment. Values are means ± SEM; n = 6 of luciferase activity corrected for β-galactosidase activity.

Significantly different from control, p < 0.05

Figure 2.

Effect of Notch on Ctgf transcript stability in osteoblasts. Calvarial osteoblasts isolated from RosaNotch mice were transduced with Ad-CMV-Cre, to activate Notch (filled circles), or control Ad-CMV-GFP (open circles) and cultured. Seventy-two h after confluence, cells were transcriptionally arrested by the addition of DRB (time 0), and harvested at the indicated times after DRB. Total RNA was extracted, reversed transcribed and amplified by qRT-PCR. Values are means ± SEM; n = 11 to 12. Data are expressed as percent of Ctgf mRNA corrected for Rpl38 expression, relative to the time of DRB addition and plotted versus time, and were pooled from 3 independent experiments. Slopes from Notch activated and control cells are significantly different, p < 0.05.

3.2 Mechanisms Responsible for the Induction of Ctgf by Notch

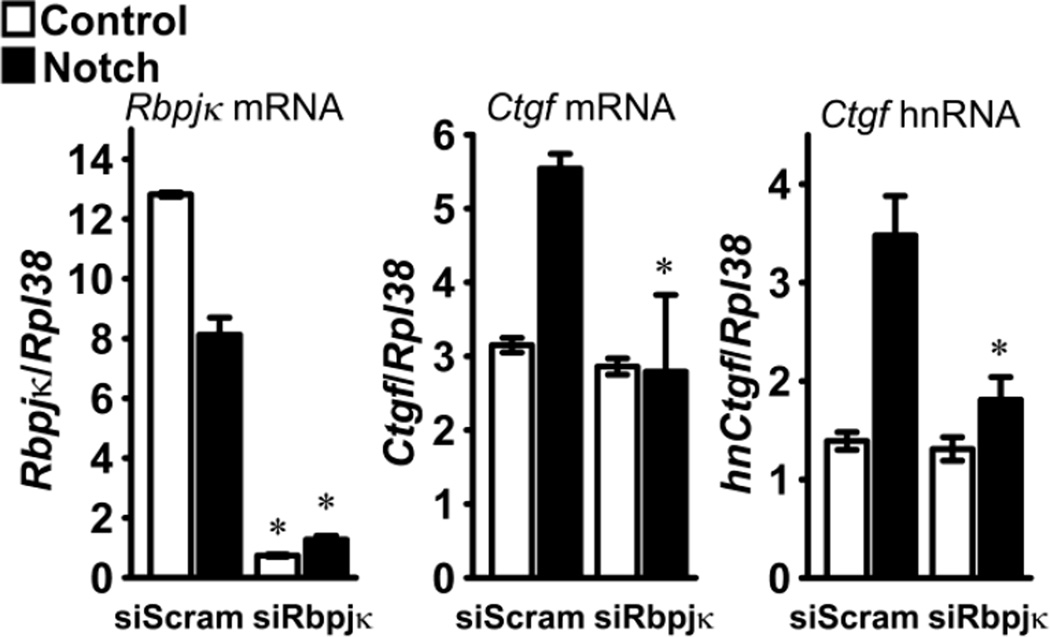

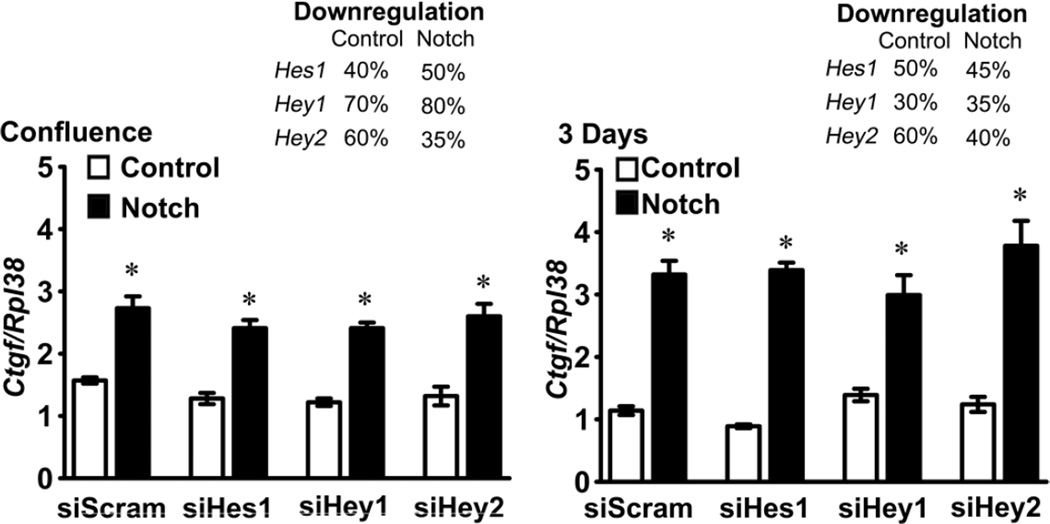

To determine whether or not the induction of Ctgf by Notch was mediated by canonical signaling, the effect of Notch on Ctgf expression was tested in the context of Rbpjκ downregulation by RNAi. Transfection of siRNAs targeting Rbpjκ into RosaNotch osteoblasts transduced with Ad-CMV-Cre precluded the induction of Ctgf mRNA and hnRNA by Notch, so that Ctgf mRNA and hnRNA levels were not different than those found in control RosaNotch osteoblasts transduced with Ad-CMV-GFP (Figure 3). To determine whether one of the classic Notch canonical target genes was responsible for the induction of Ctgf by Notch, the effect of Notch was tested in the context of the downregulation of Hes1, Hey1 or Hey2 expression by RNAi. Transfection of siHes1, siHey1 or siHey2 resulted in the downregulation of their respective transcripts by 30 to 80%, but did not modify the induction of Ctgf achieved by the activation of Notch, suggesting that the effect of Notch on Ctgf expression was not mediated by Hes1, Hey1 or Hey2 (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Effect of Notch on Ctgf expression in the context of Rbpjκ downregulation. Calvarial osteoblasts isolated from RosaNotch mice were transduced with Ad-CMV-Cre, to activate Notch (black bars), or with control Ad-CMV-GFP (white bars), transfected with Rbpjκ small interfering RNA (siRbpjκ) or scrambled siRNA (siScram) and cultured for 72 h. Total RNA was extracted, reverse transcribed and amplified by qRT-PCR. Data are expressed as copy number of Rbpjκ mRNA, Ctgf mRNA and Ctgf hnRNA, corrected for Rpl38. Values are means ± SEM; n = 4. * Significantly different between siRbpjκ and siScram, p < 0.05.

Figure 4.

Effect of Notch on Ctgf expression in the context of Hes1, Hey1 or Hey2 downregulation. Calvarial osteoblasts isolated from RosaNotch mice were transduced with Ad-CMV-Cre, to activate Notch (black bars), or with control Ad-CMV-GFP (white bars), transfected with Hes1, Hey1 or Hey2 small interfering RNA (si) or scrambled siRNA (siScram) and cultured to confluence or for 3 days after confluence. Total RNA was extracted, reverse transcribed and amplified by qRT-PCR. Data are expressed as copy number of Ctgf mRNA corrected for Rpl38. Downregulation of Hes1, Hey1 and Hey2 mRNA in control (Ad-CMV-GFP) and Notch activated (Ad-CMV-Cre) cells, expressed as the mean % of suppression relative to the mRNA expression in siScram cells is indicated in the right upper corners of both panels. Values are means ± SEM; n = 4. * Significantly different between siHes1, Hey1 or Hey2 and siScram, p < 0.05.

3.3 Effects of Notch on the Expression of Ctgf Under Physiological and In Vivo Conditions

To verify the results obtained following the activation of Notch in vitro by the transduction of Ad-CMV-Cre vectors, calvarial osteoblasts were obtained from Bglap-Cre+/−;RosaNotch and RosaNotch control mice, and cultured. Three days after confluence, osteoblasts from Bglap-Cre+/−;RosaNotch mice expressed 10 fold higher Hey2 mRNA levels than control cultures, documenting activation of Notch signaling, and 2.5 fold higher Ctgf mRNA levels, confirming the induction of Ctgf by Notch. Copy number of Ctgf/Rpl38 was (means ± SEM; n = 4) 1.3 ± 0.1 in control cultures and 3.1 ± 0.1 (p < 0.05) in cultures from Bglap-Cre+/−;RosaNotch mice.

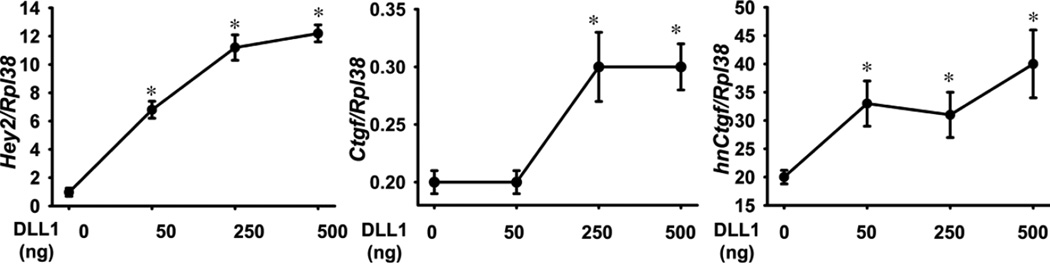

To confirm that Notch activation induced Ctgf mRNA levels under physiological conditions, wild type C57BL/6 osteoblasts were exposed to immobilized Dll1 to induce Notch signaling, or to BSA, as control. Following 3 days of culture, osteoblasts exposed to Dll1 exhibited increased Hey2 mRNA expression in comparison to cells exposed to BSA, confirming activation of Notch signaling by Dll1. In agreement with the stimulatory effects of NICD overexpression on Ctgf transcripts in RosaNotch osteoblasts, Dll1 increased Ctgf mRNA and hnRNA levels by ~1.5 - 2 fold (Figure 5), confirming that Notch induces Ctgf transcription in osteoblasts. However, Ctgf protein levels were not increased in the culture medium possibly due to the limited induction of Ctgf mRNA. Ctgf concentrations in the medium of cultures plated on BSA (values means ± SEM; n = 4) were 1.0 ± 0.1 ng/ml and in cultures plated on Dll1 were 1.0 ± 0.1 ng/ml.

Figure 5.

Effect of Notch on Hey2 mRNA, Ctgf mRNA and Ctgf hnRNA expression in osteoblasts. Wild type calvarial osteoblasts were cultured on plates coated with the Notch ligand Delta like 1 (Dll1) at the indicated doses for 72 h following confluence. Total RNA was extracted, reverse transcribed and amplified by qRT-PCR. Data are expressed as copy number of Hey2 mRNA, Ctgf mRNA and Ctgf hnRNA corrected for Rpl38 expression. Values are means ± SEM; n = 4. *Significantly different from control, p < 0.05.

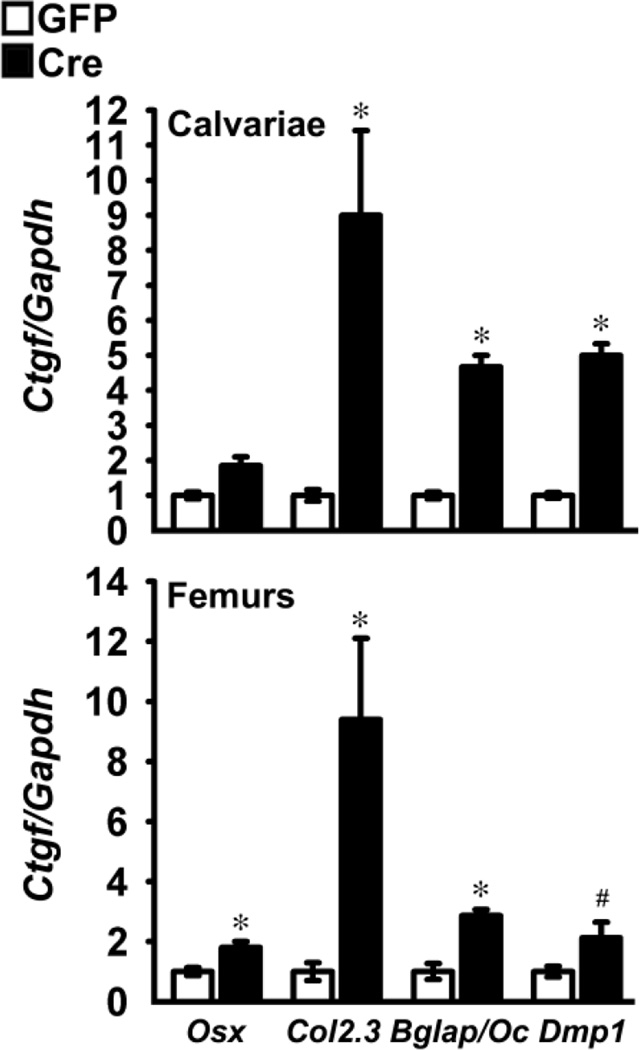

To establish whether Notch induced Ctgf in vivo, calvariae and femurs from Osx-Cre+/−;RosaNotch, Bglap-Cre+/−;RosaNotch, Col2.3-Cre+/−;RosaNotch and Dmp1-Cre+/−;RosaNotch mice and RosaNotch controls were analyzed for Ctgf mRNA expression. Notch activation was documented by demonstrating increased expression of Notch1 NICD, Hey1 and Hey2 transcripts, as previously published [38]. Notch induced Ctgf mRNA in the four RosaNotch models tested by 2 to 9 fold, demonstrating that Ctgf is a Notch target gene in vitro and in vivo (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Effect of Notch on Ctgf expression in calvarial and femoral extracts. Total RNA extracted from calvariae of male and female mice and femurs from male Osx-Cre+/−;RosaNotch, Col2.3-Cre+/−;RosaNotch; Bglap/Oc-Cre+/−;RosaNotch and Dmp1-Cre+/−;RosaNotch (black bars) and respective control RosaNotch littermates of the same sex (white bars) was reverse transcribed and amplified by qRT-PCR. Data are expressed as copy number of Ctgf corrected for Gapdh and expressed as the relative ratio with respect to controls (ratio 1.0). Values are means ± SEM; n = 3 to 10. *Significantly different between RosaNotch and control littermates, p < 0.05; # p < 0.07.

To determine whether the induction of Ctgf by Notch in the skeleton may have a systemic effect in addition to a local function, serum levels of Ctgf were measured in 1 month old RosaNotch mice. Because Osx-Cre+/−;RosaNotch dams were exposed to doxycycline throughout their pregnancy and the induction of Ctgf mRNA was modest in their progeny at 1 month of age, serum levels in this model were obtained in 3 month old mice. Activation of Notch in cells of the osteoblastic lineage resulted in an increase in serum levels of Ctgf in the four models studied, although the effect did not reach statistically significance in Col2.3+/−;RosaNotch mice (Table 3).

Table 3.

Effect of Notch activation in the skeleton on Ctgf serum levels.

| Control | RosaNotch | |

|---|---|---|

| Ctgf pg/ml | ||

| Osx-Cre;RosaNotch | 318 ± 26 | 448 ± 40* |

| Col2.3-Cre;RosaNotch | 833 ± 101 | 1448 ± 359 |

| Bglap/Oc-Cre;RosaNotch | 1011 ± 177 | 2055 ± 263* |

| Dmp1-Cre;RosaNotch | 240 ± 51 | 2047 ± 235* |

Serum levels of Ctgf were determined by ELISA in 3 month old Osx-Cre+/−;RosaNotch and 1 month old Bglap/Oc-Cre+/−;RosaNotch; Col2.3-Cre+/−;RosaNotch and Dmp1-Cre+/−;RosaNotch male mice and control male littermates. Values are means ± SEM; n = 3 – 4.

Significantly different between RosaNotch and control littermates, p < 0.05.

4. DISCUSSION

The present studies demonstrate that Notch signaling causes a time dependent induction of Ctgf expression in osteoblasts by transcriptional mechanisms. The effect of Notch on Ctgf expression is mediated by the canonical signaling pathway since it is abrogated by the downregulation of Rbpjκ by RNAi. The induction of Ctgf by Notch was observed in the RosaNotch model, where Notch is activated following the deletion of the loxP flanked STOP cassette placed downstream the Rosa26 promoter and upstream sequences coding for the NICD. It is of interest that Notch activation itself caused a modest but reproducible downregulation of Rbpjk mRNA. This may be a protective mechanism to reduce canonical effects of Notch signaling but not sufficient to prevent the induction of Ctgf by Notch, which may require nearly complete obliteration of Rbpjk expression. Notch also induced Ctgf under more “physiological” conditions in wild type osteoblasts cultured on plates pre-coated with immobilized Notch ligand Dll1. Ctgf hnRNA was induced at lower concentrations of Dll1 than Ctgf mRNA, but there is no immediate explanation for this different level of sensitivity in the response observed. The induction of Ctgf by Notch occurred in vitro and in vivo and was observed in calvariae and femurs from RosaNotch mice crossed with transgenics expressing Cre in cells of the osteoblastic lineage at various stages of differentiation and in osteocytes. There was a greater induction of Ctgf when Notch was activated by crossing RosaNotch mice with Col2.3-Cre transgenics expressing Cre in mature osteoblasts and osteocytes, and a lesser induction when RosaNotch mice were crossed with Osx-Cre transgenics expressing Cre in osteoblast precursors. This may be related to differences in the activity of the promoter used to direct Cre expression as well as differences in the genetic background of the transgenic lines expressing Cre. Col2.3-Cre transgenics are in an FVB background whereas all other lines are in a 129SvJ/C57BL/6 background. The expression of Cre in Osx-Cre transgenics is under the control of the tet-off cassette; and Cre expression was suppressed prenatally by administering doxycycline to dams throughout the pregnancy [27, 28]. This may account for the limited induction of Ctgf in 1 month old Osx-Cre;RosaNotch mice. It is important to note that skeletal derived Ctgf may be effective at the local level as well as in distant tissues since Notch activation in cells of the osteoblastic lineage in vivo resulted in an increase in serum levels of Ctgf. However, there was not a good correlation between the degree of mRNA induction in skeletal tissue and changes in serum levels. The greatest increase in serum Ctgf levels was observed in Dmp1-Cre;RosaNotch mice activating Notch in osteocytes. These cells communicate signals to other cells via a canalicular network that could make the secretion of the protein to the circulation more efficient than when induced in osteoblast precursors and mature osteoblasts.

The induction of Ctgf by Notch consistently occurred 3 days after cells reached confluence, suggesting that the effect was indirect and not due to direct interactions of the Notch transcriptional complex and the Ctgf promoter. Confirming this possibility, Notch failed to enhance the activity of a Ctgf promoter fragment acutely transfected into RosaNotch osteoblasts. We do recognize that this may also represent an absence of elements required for the activation of transcription in the promoter fragment tested. Members of the Hes and Hey families are classic Notch target genes and are thought to mediate most of the cellular effects of Notch in bone. However, the induction of Ctgf by Notch does not appear to be mediated by the products of classic canonical Notch target genes Hes1, Hey1 or Hey2 since their downregulation did not preclude the induction of Ctgf by Notch. It is noteworthy that the downregulation of each one of these target genes (30 to 80%) may have been insufficient or that the actions of a downregulated gene may have been compensated by a related gene since there is known redundancy in the biological functions of the products of Hes and Hey genes [3, 26]. However, Hes and Heys are mostly inhibitors of transcription; therefore, are not likely to be responsible for the induction of Ctgf by Notch [3].

It is conceivable that genes other than Hes and Heys are affected by Notch signaling to regulate selected cellular events. Ctgf may be among these genes since Ctgf has important effects on cell adhesion, proliferation, migration and differentiation [57]. The effects of Notch on cells of the osteoblastic lineage are cell-context dependent. When Notch is expressed in differentiated osteoblasts or in osteoblast precursors, it suppresses osteoblastic gene markers in vitro and causes osteopenia in vivo [38, 40, 58, 59]. Similarly, transgenic overexpression of Ctgf (Bglap-Ctgf) causes osteopenia and osteoblasts from these mice express suppressed osteocalcin and alkaline phosphatase mRNA levels [17]. These observations suggest that Ctgf may contribute to the effects of Notch or act in concert with Notch signaling in the skeleton [17]. Ctgf plays an important role in tissue fibrosis, and activation of Notch signaling has been implicated in the development of interstitial fibrosis in the kidney and in hepatic fibrosis [60–63]. The mechanism of action of Ctgf involves important interactions with other regulatory signals, such as Wnt, BMP and IGF, acting by binding either the peptide or its receptor [17–19]. Similarly, Notch has important interactions with Wnt signaling in cells of the osteoblastic lineage [54, 64].

In previous work, we documented that Ctgf decreases Notch signaling and that the effect is reversed by inhibitors of proteasome degradation [16]. The induction of Ctgf by Notch may lead to a decrease in Notch signaling and serve as a negative feedback mechanism to temper Notch activity in skeletal cells. It is of interest that Notch can destabilize Ctgf transcripts in transcriptionally arrested osteoblasts, and this effect may reduce steady state Ctgf mRNA levels. However, the net effect observed is an increase in Ctgf mRNA indicating that the prevailing effect of Notch is the transcriptional induction of Ctgf. The mechanisms involved in the destabilization of Ctgf transcripts by Notch were only partially explored, and we did not test whether the effect was due to activation of Notch canonical signaling. Reporter assays revealed that the 3'UTR of Ctgf is targeted by Notch and may be responsible for the effect on transcript destabilization. This is not unexpected since 3'UTRs frequently modulate mRNA stability. A well studied family of RNA stability motifs consists of adenosine-uridine (AU) rich elements and in previous work we demonstrated that they play a critical role in the stabilization of matrix metalloproteinase 13 in osteoblasts [56]. Similar motifs are present in the 3'UTR of Ctgf and may regulate the stability of Ctgf transcripts. It should not be surprising that Notch regulates Ctgf transcription and transcript stability since often the same regulatory elements and proteins regulate both events and could be controlled by Notch signaling [65, 66]. The destabilization of Ctgf mRNA may serve as a protective mechanism to prevent the excessive accumulation of Ctgf transcripts and protein.

Nov (CCN3) has been shown to have important interactions with Notch signaling; and in previous work, we demonstrated that Nov downregulates Notch signaling in cells of the osteoblastic lineage [67]. The effects of Nov are cell-context dependent and in myogenic cells Nov was found to upregulate Notch signaling [68]. We also tested whether Nov regulated Ctgf expression in osteoblastic ST-2 cells. In accordance with work by others in different cells, Nov suppressed Ctgf mRNA expression by 50% in ST-2 cells (E. Canalis unpublished). These results indicate that in cells of the osteoblastic lineage Nov inhibits Notch signaling and Ctgf expression.

In conclusion, Notch induces Ctgf expression in osteoblasts, and Ctgf and Notch may act in concert to regulate skeletal homeostasis.

HIGHLIGHTS.

We examined the effects of Notch on Ctgf expression in osteoblasts in vitro and in vivo.

Notch induces Ctgf mRNA and protein levels in osteoblasts by transcriptional mechanisms.

Notch canonical signaling is responsible for the induction of Ctgf.

Ctgf is a novel target of Notch signaling, and could mediate selected effects of Notch in the skeleton.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank T. Clemens for Bglap-Cre and J. Feng for Dmp1-Cre transgenics, R.P. Rysek for Ctgf cDNA, T. Iso for Hey2 cDNA, R. Wu for Gapdh cDNA, L. J. Strobhl for 12xCSL-Luc construct and B. C. Kone for Ctgf promoter construct, Lauren Kranz for technical assistance and Mary Yurczak for secretarial help.

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, under Award Numbers AR021707 and AR063049 (EC) and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, under award number DK045227 (EC). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

ABBREVIATIONS

- ATCC

American Type Culture Collectin

- Bglap

bone gamma carboxyglutamate protein

- BMP

bone morphogenetic protein

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- CCN

Cyr61, connective tissue growth factor and Nov

- CMV

cytomegalovirus

- Col2.3

2.3 kb fragment of Col1a1

- CSL

CBF1, suppressor of hairless and Lag1

- Ctgf

connective tissue growth factor

- Dll1

Delta like 1

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium

- Dmp1

Dentin matrix protein 1

- DRB

5,6-dichloro-1-β-D-ribofuranosylbenzimidazole

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- FVB

friend leukemia virus type B

- Gapdh

glyceraldehydes-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- Hes

Hairy and Enhancer of Split

- Hey

Hes-related with an YRPW motif

- hnRNA

heterogeneous nuclear RNA

- IGFBP

insulin-like growth factor binding protein

- NICD

Notch intracellular domain

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- Nov

nephroblastoma overexpressed

- Oc

osteocalcin

- Osx

osterix

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- qRT-PCR

quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction

- RNAi

RNA interference

- Rpl38

ribosomal protein l38

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Contributor Information

Ernesto Canalis, Email: ECanalis@stfranciscare.org.

Stefano Zanotti, Email: SZanott@stfranciscare.org.

Anna Smerdel-Ramoya, Email: ASRamoya@stfranciscare.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Canalis E, Economides AN, Gazzerro E. Bone morphogenetic proteins, their antagonists, and the skeleton. Endocr Rev. 2003;24:218–235. doi: 10.1210/er.2002-0023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Monroe DG, McGee-Lawrence ME, Oursler MJ, Westendorf JJ. Update on Wnt signaling in bone cell biology and bone disease. Gene. 2012;492:1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2011.10.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zanotti S, Canalis E. Notch and the Skeleton. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:886–896. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01285-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gazzerro E, Canalis E. Skeletal actions of insulin-like growth factors. Expert Rev Endocrinol Metab. 2006;1:47–56. doi: 10.1586/17446651.1.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Canalis E. Wnt signalling in osteoporosis: mechanisms and novel therapeutic approaches. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2013;9:575–583. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2013.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zanotti S, Canalis E. Notch signaling in skeletal health and disease. Eur J Endocrinol. 2013;168:R95–R103. doi: 10.1530/EJE-13-0115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brigstock DR. The CCN family: a new stimulus package. J Endocrinol. 2003;178:169–175. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1780169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brigstock DR, Goldschmeding R, Katsube KI, Lam SC, Lau LF, Lyons K, et al. Proposal for a unified CCN nomenclature. Mol Pathol. 2003;56:127–128. doi: 10.1136/mp.56.2.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Isaacs NW. Cystine knots. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1995;5:391–395. doi: 10.1016/0959-440x(95)80102-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garcia AJ, Coffinier C, Larrain J, Oelgeschlager M, De Robertis EM. Chordin-like CR domains and the regulation of evolutionarily conserved extracellular signaling systems. Gene. 2002;287:39–47. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00827-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pereira RC, Durant D, Canalis E. Transcriptional regulation of connective tissue growth factor by cortisol in osteoblasts. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2000;279:E570–E576. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2000.279.3.E570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parisi MS, Gazzerro E, Rydziel S, Canalis E. Expression and regulation of CCN genes in murine osteoblasts. Bone. 2006;38:671–677. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumar A, Ruan M, Clifton K, Syed F, Khosla S, Oursler MJ. TGF-beta mediates suppression of adipogenesis by estradiol through connective tissue growth factor induction. Endocrinology. 2012;153:254–263. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arnott JA, Lambi AG, Mundy C, Hendesi H, Pixley RA, Owen TA, et al. The role of connective tissue growth factor (CTGF/CCN2) in skeletogenesis. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 2011;21:43–69. doi: 10.1615/critreveukargeneexpr.v21.i1.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nishida T, Nakanishi T, Asano M, Shimo T, Takigawa M. Effects of CTGF/Hcs24, a hypertrophic chondrocyte-specific gene product, on the proliferation and differentiation of osteoblastic cells in vitro. J Cell Physiol. 2000;184:197–206. doi: 10.1002/1097-4652(200008)184:2<197::AID-JCP7>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smerdel-Ramoya A, Zanotti S, Deregowski V, Canalis E. Connective tissue growth factor enhances osteoblastogenesis in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:22690–22699. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710140200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smerdel-Ramoya A, Zanotti S, Stadmeyer L, Durant D, Canalis E. Skeletal Overexpression Of Connective Tissue Growth Factor (CTGF) Impairs Bone Formation And Causes Osteopenia. Endocrinology. 2008;149:4374–4381. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abreu JG, Ketpura NI, Reversade B, De Robertis EM. Connective-tissue growth factor (CTGF) modulates cell signalling by BMP and TGF-beta. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:599–604. doi: 10.1038/ncb826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mercurio S, Latinkic B, Itasaki N, Krumlauf R, Smith JC. Connective-tissue growth factor modulates WNT signalling and interacts with the WNT receptor complex. Development. 2004;131:2137–2147. doi: 10.1242/dev.01045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Canalis E, Zanotti S, Beamer WG, Economides AN, Smerdel-Ramoya A. Connective Tissue Growth Factor Is Required for Skeletal Development and Postnatal Skeletal Homeostasis in Male Mice. Endocrinology. 2010;151:3490–3501. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ivkovic S, Yoon BS, Popoff SN, Safadi FF, Libuda DE, Stephenson RC, et al. Connective tissue growth factor coordinates chondrogenesis and angiogenesis during skeletal development. Development. 2003;130:2779–2791. doi: 10.1242/dev.00505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakanishi T, Yamaai T, Asano M, Nawachi K, Suzuki M, Sugimoto T, et al. Overexpression of connective tissue growth factor/hypertrophic chondrocyte-specific gene product 24 decreases bone density in adult mice and induces dwarfism. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;281:678–681. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lambi AG, Pankratz TL, Mundy C, Gannon M, Barbe MF, Richtsmeier JT, et al. The skeletal site-specific role of connective tissue growth factor in prenatal osteogenesis. Dev Dyn. 2012;241:1944–1959. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.23888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nam Y, Sliz P, Song L, Aster JC, Blacklow SC. Structural basis for cooperativity in recruitment of MAML coactivators to Notch transcription complexes. Cell. 2006;124:973–983. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilson JJ, Kovall RA. Crystal structure of the CSL-Notch-Mastermind ternary complex bound to DNA. Cell. 2006;124:985–996. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iso T, Kedes L, Hamamori Y. HES and HERP families: multiple effectors of the Notch signaling pathway. J Cell Physiol. 2003;194:237–255. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murtaugh LC, Stanger BZ, Kwan KM, Melton DA. Notch signaling controls multiple steps of pancreatic differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:14920–14925. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2436557100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stanger BZ, Datar R, Murtaugh LC, Melton DA. Direct regulation of intestinal fate by Notch. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:12443–12448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505690102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buchholz F, Ringrose L, Angrand PO, Rossi F, Stewart AF. Different thermostabilities of FLP and Cre recombinases: implications for applied site-specific recombination. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:4256–4262. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.21.4256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sauer B, Henderson N. Site-specific DNA recombination in mammalian cells by the Cre recombinase of bacteriophage P1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:5166–5170. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.14.5166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bogdanovic Z, Bedalov A, Krebsbach PH, Pavlin D, Woody CO, Clark SH, et al. Upstream regulatory elements necessary for expression of the rat COL1A1 promoter in transgenic mice. J Bone Miner Res. 1994;9:285–292. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650090218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Frenkel B, Capparelli C, Van Auken M, Baran D, Bryan J, Stein JL, et al. Activity of the osteocalcin promoter in skeletal sites of transgenic mice and during osteoblast differentiation in bone marrow-derived stromal cell cultures: effects of age and sex. Endocrinology. 1997;138:2109–2116. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.5.5105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lu Y, Xie Y, Zhang S, Dusevich V, Bonewald LF, Feng JQ. DMP1-targeted Cre expression in odontoblasts and osteocytes. J Dent Res. 2007;86:320–325. doi: 10.1177/154405910708600404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakashima K, Zhou X, Kunkel G, Zhang Z, Deng JM, Behringer RR, et al. The novel zinc finger-containing transcription factor osterix is required for osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. Cell. 2002;108:17–29. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00622-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rodda SJ, McMahon AP. Distinct roles for Hedgehog and canonical Wnt signaling in specification, differentiation and maintenance of osteoblast progenitors. Development. 2006;133:3231–3244. doi: 10.1242/dev.02480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang M, Xuan S, Bouxsein ML, von Stechow D, Akeno N, Faugere MC, et al. Osteoblast-specific knockout of the insulin-like growth factor (IGF) receptor gene reveals an essential role of IGF signaling in bone matrix mineralization. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:44005–44012. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208265200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dacquin R, Starbuck M, Schinke T, Karsenty G. Mouse alpha1(I)-collagen promoter is the best known promoter to drive efficient Cre recombinase expression in osteoblast. Dev Dyn. 2002;224:245–251. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Canalis E, Parker K, Feng JQ, Zanotti S. Osteoblast Lineage-specific Effects of Notch Activation in the Skeleton. Endocrinology. 2013;154:623–634. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McCarthy TL, Centrella M, Canalis E. Further biochemical and molecular characterization of primary rat parietal bone cell cultures. J Bone Miner Res. 1988;3:401–408. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650030406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zanotti S, Smerdel-Ramoya A, Canalis E. Reciprocal regulation of notch and nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NFAT)c1 transactivation in osteoblasts. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:4576–4588. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.161893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nobta M, Tsukazaki T, Shibata Y, Xin C, Moriishi T, Sakano S, et al. Critical regulation of bone morphogenetic protein-induced osteoblastic differentiation by Delta1/Jagged1-activated Notch1 signaling. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:15842–15848. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412891200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zandomeni R, Bunick D, Ackerman S, Mittleman B, Weinmann R. Mechanism of action of DRB. III. Effect on specific in vitro initiation of transcription. J Mol Biol. 1983;167:561–574. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80098-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Elbashir SM, Harborth J, Lendeckel W, Yalcin A, Weber K, Tuschl T. Duplexes of 21-nucleotide RNAs mediate RNA interference in cultured mammalian cells. Nature. 2001;411:494–498. doi: 10.1038/35078107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nazarenko I, Lowe B, Darfler M, Ikonomi P, Schuster D, Rashtchian A. Multiplex quantitative PCR using self-quenched primers labeled with a single fluorophore. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:e37. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.9.e37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nazarenko I, Pires R, Lowe B, Obaidy M, Rashtchian A. Effect of primary and secondary structure of oligodeoxyribonucleotides on the fluorescent properties of conjugated dyes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:2089–2195. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.9.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Iso T, Sartorelli V, Poizat C, Iezzi S, Wu HY, Chung G, et al. HERP, a novel heterodimer partner of HES/E(spl) in Notch signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:6080–6089. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.17.6080-6089.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Iso T, Sartorelli V, Chung G, Shichinohe T, Kedes L, Hamamori Y. HERP, a new primary target of Notch regulated by ligand binding. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:6071–6079. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.17.6071-6079.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ryseck RP, donald-Bravo H, Mattei MG, Bravo R. Structure, mapping, and expression of fisp-12, a growth factor-inducible gene encoding a secreted cysteine-rich protein. Cell Growth Differ. 1991;2:225–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tso JY, Sun XH, Kao TH, Reece KS, Wu R. Isolation and characterization of rat and human glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase cDNAs: genomic complexity and molecular evolution of the gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 1985;13:2485–2502. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.7.2485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Akazawa C, Sasai Y, Nakanishi S, Kageyama R. Molecular characterization of a rat negative regulator with a basic helix-loop-helix structure predominantly expressed in the developing nervous system. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:21879–21885. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Strobl LJ, Hofelmayr H, Stein C, Marschall G, Brielmeier M, Laux G, et al. Both Epstein-Barr viral nuclear antigen 2 (EBNA2) and activated Notch1 transactivate genes by interacting with the cellular protein RBP-J kappa. Immunobiology. 1997;198:299–306. doi: 10.1016/s0171-2985(97)80050-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yu Z, Kong Q, Kone BC. CREB trans-activation of disruptor of telomeric silencing-1 mediates forskolin inhibition of CTGF transcription in mesangial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2010;298:F617–F624. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00636.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Deregowski V, Gazzerro E, Priest L, Rydziel S, Canalis E. Notch 1 Overexpression Inhibits Osteoblastogenesis by Suppressing Wnt/beta-Catenin but Not Bone Morphogenetic Protein Signaling. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:6203–6210. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508370200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sokal RR, Rohlf FJ. Biometry. 2nd Edition. San Francisco, CA: W.H. Freeman; 1981. Biometry. 2nd Edition. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rydziel S, Delany AM, Canalis E. AU-rich elements in the collagenase 3 mRNA mediate stabilization of the transcript by cortisol in osteoblasts. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:5397–5404. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311984200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Safadi FF, Xu J, Smock SL, Kanaan RA, Selim AH, Odgren PR, et al. Expression of connective tissue growth factor in bone: its role in osteoblast proliferation and differentiation in vitro and bone formation in vivo. J Cell Physiol. 2003;196:51–62. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zanotti S, Smerdel-Ramoya A, Stadmeyer L, Durant D, Radtke F, Canalis E. Notch Inhibits Osteoblast Differentiation And Causes Osteopenia. Endocrinology. 2008;149:3890–3899. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zanotti S, Smerdel-Ramoya A, Canalis E. Nuclear Factor of Activated T-cells (Nfat)c2 Inhibits Notch Signaling in Osteoblasts. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:624–632. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.340455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yang J, Velikoff M, Canalis E, Horowitz JC, Kim KK. Activated Alveolar Epithelial Cells Initiate Fibrosis Through Autocrine and Paracrine Secretion of Connective Tissue Growth Factor. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2014 doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00243.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chen Y, Zheng S, Qi D, Zheng S, Guo J, Zhang S, et al. Inhibition of Notch signaling by a gamma-secretase inhibitor attenuates hepatic fibrosis in rats. PLoS One. 2012;7:e46512. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhu F, Li T, Qiu F, Fan J, Zhou Q, Ding X, et al. Preventive effect of Notch signaling inhibition by a gamma-secretase inhibitor on peritoneal dialysis fluid-induced peritoneal fibrosis in rats. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:650–659. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bielesz B, Sirin Y, Si H, Niranjan T, Gruenwald A, Ahn S, et al. Epithelial Notch signaling regulates interstitial fibrosis development in the kidneys of mice and humans. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:4040–4054. doi: 10.1172/JCI43025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Canalis E, Adams DJ, Boskey A, Parker K, Kranz L, Zanotti S. Notch Signaling in Osteocytes Differentially Regulates Cancellous and Cortical Bone Remodeling. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:25614–25625. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.470492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bregman A, Avraham-Kelbert M, Barkai O, Duek L, Guterman A, Choder M. Promoter elements regulate cytoplasmic mRNA decay. Cell. 2011;147:1473–1483. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Haimovich G, Medina DA, Causse SZ, Garber M, Millan-Zambrano G, Barkai O, et al. Gene expression is circular: factors for mRNA degradation also foster mRNA synthesis. Cell. 2013;153:1000–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rydziel S, Stadmeyer L, Zanotti S, Durant D, Smerdel-Ramoya A, Canalis E. Nephroblastoma overexpressed (Nov) inhibits osteoblastogenesis and causes osteopenia. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:19762–19772. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700212200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sakamoto K, Yamaguchi S, Ando R, Miyawaki A, Kabasawa Y, Takagi M, et al. The nephroblastoma overexpressed gene (NOV/ccn3) protein associates with Notch1 extracellular domain and inhibits myoblast differentiation via Notch signaling pathway. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:29399–29405. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203727200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]