Abstract

Background and Aim

Cytokine-inducible SRC homology 2 domain protein (CISH) is the first member of the suppressors of cytokine signaling (SOCS) protein family. An association between multiple CISH polymorphisms and susceptibility to infectious diseases has been reported. This study aimed to investigate the possible association of these single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in CISH gene with different outcomes of Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection.

Methods

1019 unrelated Chinese Han subjects, including 240 persistent asymptomatic HBV carriers, 217 chronic hepatitis B patients, 137 HBV-related liver cirrhosis patients, and 425 cases of spontaneously recovered HBV as controls, were studied. Four SNPs (rs622502, rs2239751, rs414171 and rs6768300) in CISH gene were genotyped with the snapshot technique. Transcriptional activity of the CISH promoter was assayed in vitro using the dual-luciferase reporter assay system.

Results

At position rs414171, A allele and AA genotype frequencies were significantly higher in the HBV-resolved group as compared to the persistent HBV infection group. At position rs2239751, TT genotype was further observed in the HBV-resolved group. Using asymptomatic HBV carriers as controls, our results indicated that the rs414171 and rs2239751 polymorphisms were unrelated to HBV progression. The other two SNPs (rs622502 and rs6768300) showed no association with persistent HBV infection. Haplotype analysis revealed that the GGCA haplotype was associated with spontaneous clearance of HBV in this population. Moreover, luciferase activity was significantly higher in the PGL3-Basic-rs414171T construct as compared to the PGL3-Basic-rs414171A construct (p<0.001).

Conclusion

Two SNPs (rs414171 and rs2239751) in the CISH gene were associated with persistent HBV infection in Han Chinese population, but not with HBV progression.

Introduction

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection remains a global health problem. Patients with chronic HBV infection are at risk of developing diverse severe outcomes, including liver cirrhosis, liver failure, or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [1]. Although the precise mechanisms of susceptibility to chronic HBV infection and factors influencing different clinical outcomes are not well understood, accumulating evidence indicates that host factors such as polymorphisms in some key genes could influence the outcomes of patients with HBV infection [2], [3], [4].

The suppressors of cytokine signaling (SOCS) are a family of intracellular proteins, which have been shown to play critical roles in both innate and adaptive immune responses [5], [6], [7], [8]. Cytokine-inducible SH2-containing protein (CISH), the first identified member of the SOCS protein family,can be induced in response to stimulation by different cytokines, and negatively regulates the signaling of cytokines, in particular IL-2. Recent studies have suggested that CISH is involved in human diseases [9], [10], and polymorphisms in CISH gene are associated with susceptibility to infectious diseases [11], including bacteremia, malaria, tuberculosis and Hepatitis B [12]. Therefore, we aimed to investigate the possible relationship between these CISH polymorphisms (rs622502, rs2239751, rs414171 and rs6768300) and the different outcomes of HBV infection in Chinese Han population.

Materials and Methods

Study population

The study participants were selected from the first affiliated hospital of Chengdu medical college in Sichuan province of southwestern China. The study protocol adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by the ethics committee of the first affiliated hospital of Chengdu medical college. All patients signed an informed consent prior to enrollment in the study. A total of 594 persistent HBV-infected patients of unrelated Chinese Han population were included in this study, of which 240 were chronic asymptomatic HBV carriers (AsC), 217 patients had active chronic hepatitis B (CHB) infection, and 137 were liver cirrhosis (LC) patients. Persistent HBV infection was defined as presence of positive HBsAg for at least 6 months. A group of 425 individuals with spontaneous clearance of HBV (HBV-resolved) served as the control group. Clinical criteria for HBV-resolved group were: negative for HBsAg, plus positive for both anti-HBs and anti-HBc, or plus anti-HBs positive without any history of hepatitis B vaccination. About 90% of HBV-resolved cases were anti-HBc positive in our cohort. All individuals were tested to exclude Hepatitis C (HCV), Hepatitis D (HDV), and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infections(The baseline characteristics of the study subjects are summarized in Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of study subjects.

| HBV-resolved(n = 425) | AsC(n = 240) | CHB(n = 217) | LC(n = 137) | |

| Male | 191(44.90%) | 147(61.25%) | 148(68.20%) | 109(79.56%) |

| Female | 234(55.06%) | 93(38.75%) | 69(31.80%) | 28(20.44%) |

| age | 41.08±14.38 | 36.23±11.98 | 40.65±13.13 | 49.69±11.63 |

| HBsAg+ | 0 | 240(100.0%) | 217(100.0%) | 137(100%) |

| Anti-HBs+ | 410(96.47%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| HBeAg+ | 0 | 56(23.33%) | 98(45.16%) | 21(15.33%) |

| Anti-HBc+ | 398(93.65%) | 138(57.50%) | 142(65.44%) | 107(78.10%) |

| ALT>40(IU/L) | 0 | 0 | 201(92.63%) | 46(33.58%) |

DNA isolation and genotyping

Genomic DNA was isolated from peripheral whole blood using TIANamp blood DNA kit. The concentration and purity of the DNA were determined with a NanoDrop spectrophotometer, and the DNA was diluted to a final concentration of 10 ng/µL. Multiplex PCR reactions were designed to amplify CISH fragments covering all objective CISH SNP loci(The primers used in this study were shown in Table S1). These PCR reactions were performed in a total volume of 20 µl containing 1×GC Buffer I (Takara), 3.0 mM Mg2+, 0.3 mM dNTP, 1 U of HotStart Taq DNA polymerase (Takara), 2 µl of multiple primers, and 1 µl of genomic DNA. The cycling conditions were 95°C for 2 min, 11 cycles at 94°C for 20 s, 65°C for 40 s, 72°C for 1.5 min; 24 cycles at 94°C for 20 s, 59°C for 30 s, 72°C for 1.5 min, followed by 72°C for 2 min, and finally kept at 4°C. 15 µl of mixed PCR products were then incubated with 5 U of shrimp alkaline phosphatase (SAP) and 5 U of Exonuclease I (ExoI) at 37°C for 1 hour, and then inactivated at 75°C for 15 min. 10 µl of extension reaction contained 5 µl of SNaPshot Multiplex Kit (ABI), 2 µl of purified PCR products, 1 µl of extension primers, and 2 µl of ultrapure water. The ligation cycling programs were 96°C for 1 min; 28 cycles at 96°C for 10 s, 52°C for 5 s, 60°C for 30 s, and then kept at 4°C. 0.5 µl of purified extension products were loaded in ABI 3130XL sequencer (Applied Biosystems, USA), and the primary data were analyzed by GeneMapper 4.1 (Applied Biosystems, USA).

Luciferase assay with SNP at rs414171 in the CISH promoter

The Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega, USA) was chosen to identify the activity of CISH promoter. All experiments were performed according to the manufacturer's guidelines. Briefly, primer sequences were designed using Primer Premier 5.0 and Oligo software as follows: Sense: 5′ –CTAGCTAGCGCTGCCTAATCCTTTGTCTG-3′ (the sequence in bold is an NheI restriction site), Antisense: 5′-CCGCTCGAGCACGCCGACAGACCTCCTTG-3′ (the sequence in bold is an XhoI restriction site). Consensus primers were designed to CISH regions, which includes rs414171 A>T polymorphisms were used to amplify a 493 bp sequence from human genomic DNA by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). In this clone, all 493 bp nucleotides were located upstream of the first exon of CISH sequence. DNA fragments corresponding to CISH promoter region from nucleotides −12 to −505 (relative to the first nucleotide of the open reading frame of CISH) were inserted upstream of the firefly luciferase gene in the pGL3-Basic plasmid vector (Promega, USA) in separate steps, and were named as basic AA and basic TT. All reporter constructs were confirmed by direct sequencing. 293T cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM, Gibco, USA) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Biowest, France). For luciferase assays, 293T cells were plated in a 96-well plate and grown to 60% confluency. For transfections, 0.1 µg of a given reporter construct and 10 ng of pRL-TK (renilla, internal control, Promega) per well were co-transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 Reagent (Invitrogen, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. After transfection for 48 hours, cells were lysed in 100 µl of 1× passive lysis buffer (PLB buffer from Promega) at room temperature for 20 min. For dual luciferase assay, 30 µl of lysate was aliquoted into a 96-well plate for measuring firefly luciferase (50 µl of LAR II) and renilla luciferase (50 µl of stop and glow buffer) activity. Fluorescence intensity was read on BioTek Synergy 4 multi-mode microplate reader (BioTek Instruments Inc., USA). All experiments were repeated three times in triplicate.

Statistical analysis

Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium (HWE) assumptions were independently tested for each polymorphism using x2 test. The strength of association between the alleles or genotypes and disease status were calculated using SPSS 18.0 software. The odds ratios (ORs) with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were computed on the basis of the binary logistic regression analysis, and adjusted for age and gender. P value <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Haplotype frequencies were estimated by using PHASE 2.1.

Results

Genotyping of CISH polymorphisms

Four SNPs in CISH gene were genotyped in 594 persistent HBV infection and 425 HBV-resolved controls. The genotypic distributions of CISH polymorphisms (rs622502, rs2239751, rs414171 and rs6768300) were found to be in HWE with an minor allele frequency (MAF) of 1% in the southwestern Chinese Han population (Table 2).

Table 2. SNP marker information for CISH gene for all subjects studied (persistent HBV infection and HBV-resolved).

| Gene | Chr.No | SNPs | position | location | ObesHET | PredHET | HWpval | MAF | Alleles |

| rs622502 | +3415 | intron | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.33 | 0.06 | G:C | ||

| CISH | 3 | rs2239751 | +1320 | exon | 0.47 | 0.47 | 0.81 | 0.39 | T:G |

| rs6768300 | −163 | promoter | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.89 | 0.06 | C:G | ||

| rs414171 | −292 | promoter | 0.48 | 0.49 | 0.50 | 0.44 | T:A |

Comparison of CISH gene polymorphisms between HBV-persistent and HBV-resolved groups

The CISH gene and genotype frequencies are presented in Table 3. The alleles and genotype frequencies for SNPs of rs622502 and rs6768300, did not significantly differ between persistent HBV infection and HBV-resolved groups (all p>0.05). Regression analyses showed no association between the above-mentioned SNPs and different outcomes following HBV infection in this study (data not shown). While rs414171 showed significant association with persistent HBV infection, in the case of rs414171 with AA as reference, the TT carriage had a significantly higher risk for persistent HBV infection group after adjustments for age and gender (OR = 1.71; CI: 1.19–2.47; x2-value = 8.40, p = 0.004). Taking A allele as conference, the OR of T allele carriage for persistent HBV infection was 1.27 (p<0.01). Compared to individuals carrying the GG genotype and G allele of rs2239751, those with TT genotype and T allele had an increased risk of persistent HBV infection with an adjusted OR of 1.63 (95% CI = 1.10–2.37) and 1.23 (95% CI = 1.02–1.47), respectively.

Table 3. CISH genotype and allelic frequencies for association with persistent HBV infection in Chinese Han population.

| SNPs | Case (n = 594) | Control(n = 425) | OR(95%CI) | x2 | adjusted p value |

| rs2239751 | |||||

| GG | 78 (13.13%) | 75 (17.65%) | 1 | 6.01 | 0.05 |

| GT | 277 (46.63%) | 201 (47.29%) | 1.39 (0.95–2.02) | 2.92 | 0.09 |

| TT | 239 (40.24%) | 149 (35.06%) | 1.63(1.10–2.39) | 5.99 | 0.01 |

| G | 433(36.45%) | 351(41.29%) | 1 | ||

| T | 755(63.55%) | 499(58.70%) | 1.23(1.02–1.47) | 4.92 | 0.03 |

| rs414171 | |||||

| AA | 107(18.01%) | 101(23.76%) | 1 | 8.40 | 0.02 |

| TA | 283(47.64%) | 204(48.00%) | 1.39(0.99–1.99) | 3.67 | 0.06 |

| TT | 204(34.34%) | 120(28.24%) | 1.71(1.19–2.47) | 8.40 | 0.004 |

| Allele A | 497(41.83%) | 406(47.76%) | 1 | ||

| Allele T | 691(58.16%) | 444(52.24% | 1.27(1.07–1.52) | 7.06 | 0.01 |

| rs622502 | |||||

| GG | 529(89.06%) | 372(87.53%) | 1 | 1.13 | 0.57 |

| GC | 62 (10.43%) | 50 (11.76%) | 1.30(0.242–6.70) | 0.09 | 0.76 |

| CC | 3 (0.51%) | 3 (0.71%) | 1.58(0.31–8.17) | 0.30 | 0.59 |

| G | 1120(94.28%) | 794(93.41%) | 1 | ||

| C | 68(5.72%) | 56(6.59%) | 1.16(0.81–1.67) | 0.65 | 0.42 |

| rs6768300 | |||||

| CC | 532(89.56%) | 373(87.76%) | 1 | 2.32 | 0.31 |

| GC | 61 (10.27%) | 49 (11.53%) | 0.82 (0.55–1.24) | 0.86 | 0.35 |

| GG | 1 (0.17%) | 3 (0.71%) | 0.24 (0.02–2.37) | 1.51 | 0.22 |

| C | 1125(94.70%) | 795(93.53%) | 1 | ||

| G | 63(5.30%) | 55(6.47%) | 1.24(0.85–1.79) | 1.24 | 0.27 |

Data were calculated by binary logistic regression analysis.

Association between CISH gene polymorphisms (rs2239751 and rs414171) in different persistent HBV infection groups

To determine whether rs414171 and rs2239751 polymorphisms were associated with different outcomes of persistent HBV infection, a similar analysis was done by comparing case CHB+LC with AsC group, and case LC with AsC group. However, no significant association was observed in any of these comparisons (Tables 4 and 5).

Table 4. Genotype and allelic distribution for CISH gene polymorphisms when AsC group was compared to CHB+LC group.

| SNP | AsC (N = 240) | CHB+LC (N = 354) | OR(95%CI) | x2 | adjusted P value |

| rs2239751 | |||||

| GG | 37(15.42%) | 41(11.58%) | 1 | 2.06 | 0.36 |

| GT | 102(42.50%) | 175(49.44%) | 1.47(0.86–2.51) | 2.01 | 0.16 |

| TT | 101(42.08%) | 138 (38.98%) | 1.29 (0.75–2.22) | 0.86 | 2.51 |

| G | 176(36.67%) | 257(36.30%) | 1 | ||

| T | 304(63.33%) | 451(63.70%) | 0.98(0.774–1.25) | 0.02 | 0.90 |

| rs414171 | |||||

| AA | 50(20.83%) | 57 (16.10%) | 1 | 2.32 | 0.31 |

| AT | 104(43.33%) | 179 (50.56%) | 1.45 (1.90–2.33) | 2.32 | 0.13 |

| TT | 86(35.83%) | 118 (33.33%) | 1.31(0.80–2.16) | 1.13 | 0.30 |

| A | 204(42.50%) | 293(41.38%) | 1 | ||

| T | 276(57.50%) | 415(58.62%) | 0.96(0.76–1.21) | 0.15 | 0.70 |

Table 5. Genotype and allelic distribution for CISH gene polymorphisms when AsC group was compared to LC group.

| SNP | AsC(N = 240) | LC (N = 137) | OR(95%CI) | x2 | adjusted p value |

| rs2239751 | |||||

| GG | 37(15.42%) | 16(11.68%) | 1 | 3.81 | 0.15 |

| GT | 102(42.50%) | 76(55.47%) | 1.64(0.76–3.52) | 0.39 | 0.21 |

| TT | 101(42.08%) | 45(32.85%) | 0.99 (0.45–2.20) | 0.00 | 0.99 |

| G | 176(36.67%) | 108(39.42%) | 1 | ||

| T | 304(63.33%) | 166(60.58%) | 1.12(0.83–1.53) | 0.56 | 0.45 |

| rs414171 | |||||

| AA | 50(20.83%) | 21(15.33%) | 1 | 5.90 | 0.05 |

| AT | 104(43.33%) | 80(58.39%) | 1.92(0.96–3.85) | 3.41 | 0.07 |

| TT | 86(35.83%) | 36(26.28%) | 1.05(0.50–2.22) | 0.02 | 0.90 |

| A | 204(42.50%) | 122(44.53%) | 1 | ||

| T | 276(57.50%) | 152(55.47%) | 1.09(0.81–1.47) | 0.29 | 0.60 |

Haplotype analysis

We constructed haplotypes of these four SNPs (rs622502, rs2239751, rs6768300 and rs414171) for association analysis correlating with persistent HBV infection. As compared to the most common GTCT haplotype, only GGCA haplotype was significantly associated with lower risk of chronic HBV infection (OR = 0.79; 95% CI: 0.65–0.95; x2 = 6.51, p = 0.003) (Table 6).

Table 6. Results of the association test for four SNPs (rs622502, rs2239751, rs6768300 and rs414171) haplotypes in Han population from southwestern China.

| Haplotype | Cases(Freq) | Controls(Freq) | OR(95%CI) | chip-square | Adjusted p value |

| GTCT | 689(58.00%) | 443(52.10%) | 1 | ||

| GGCA | 428(36.03%) | 350(41.20%) | 0.79(0.65–0.95) | 6.51 | 0.003 |

| CTGA | 63(5.30%) | 54(6.35%) | 0.75(0.51–1.10) | 2.18 | 0.14 |

The most common haplotype as the reference.

Effects of rs414171 on transcriptional activity of CISH gene

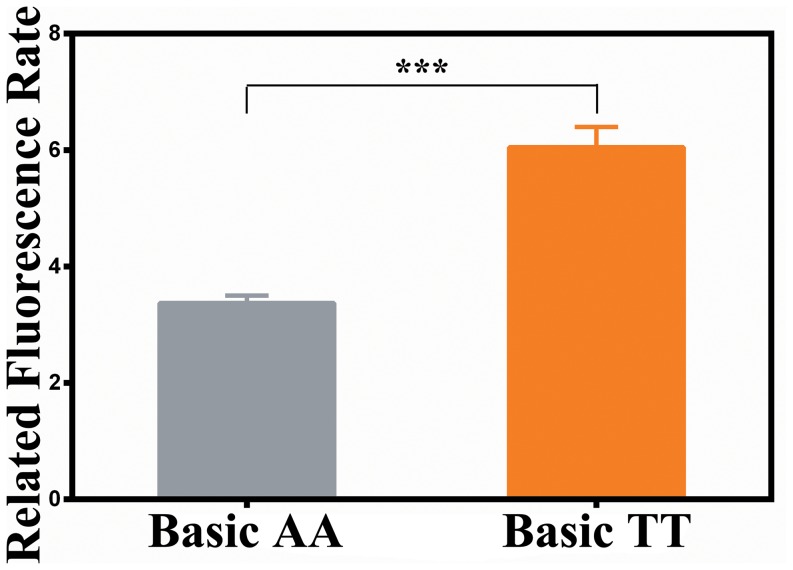

To confirm the effects of rs414171 SNP on CISH gene transcription, we analyzed the transcriptional activity of its promoter with a dual-luciferase reporter assay system, and compared the activities of rs414171A and rs414171T alleles using a transient transfection assay in 293T cells. As shown in Figure 1, the pGL3-Basic-rs414171TT reporter showed significantly higher luciferase activity as compared to pGL3-Basic-rs414171AA, suggesting that the A to T polymorphism at position rs414171 may increase the activity of the CISH promoter.

Figure 1. Effect of the rs414171 polymorphism on promoter transcriptional activity.

Significantly higher luciferase activities were generated by the pGL3-Basic-T construct as compared to the pGL3-Basic-A construct. (***P<0.001).

Discussion

Several methods exist for SNP detection. In the present study, we adapted the snapshot method for SNP detection. As compared to the direct sequencing method, the snapshot method is both time- and cost-efficient, and is therefore, suitable for examining large samples and multilocus genotyping. The accuracy of the assay was validated by direct sequencing [13].

In this study, we investigated four SNPs in the CISH gene, and the correlation of these polymorphisms with HBV clearance and disease progression. The frequency of allele A and AA genotype at position rs414171, and GG genotype at position rs2239751 of CISH gene were higher in the HBV clearance group as compared to the persistence group. This finding is consistent with a recent study conducted by Tong et al. [12]. Individuals carrying the GGCA haplotype are at a higher risk of developing persistent HBV infection as compared to the most common haplotype, GTCT. However, there is no correlation of these four SNPs with disease progression. Our study suggests that the rs414171 and rs2239751 polymorphisms could be associated with the persistence or chronicity of HBV infection, but perhaps they did not correlate with the development of CHB after adjustments for age and gender. Additionally, our findings indicate that SNP rs414171 (A/T) affects the activity of the CISH promoter, and either the A allele or the T allele can substantially drive reporter gene expression. Moreover, significantly higher luciferase activity was found for the rs414171 TT genotype as compared to the AA genotype. This finding suggests that SNP rs414171 is functional, and the substitution of a T for an A can enhance CISH promoter transcriptional activity. However, our results are inconsistent with the previous study [11] in that higher level of CISH gene expression in human PBMCs following Interleukin-2 stimulation is associated with the rs414171AA genotype.

Previous studies have demonstrated that CISH is an immediate-early gene that is induced by several cytokines and T cell receptor (TCR) stimulation. As a result, elevated CISH can negatively regulate cytokine receptor signaling through JAK/STAT pathway, and promote T cell proliferation and survival in a STAT5-independent manner [14], [15]. Since CISH has a pivotal role in immune responses, and it can inhibit the activation of STAT3, STAT5 and STAT6 in T cells, CISH-deficient T cells tend to differentiate into Th2 and Th9 subsets. Also, airway inflammation arises spontaneously in CISH-deficient mice [16], indicating that CISH could be involved in diseases by regulating the differentiation of T cells. By binding to protein kinase Cφ, CISH could enhance FoxP3 expression of natural regulatory CD4+ T cells (Tregs), and mediate expansion of Tregs [17], [18], [19], which have been demonstrated to be enhanced in patients with CHB. The expansion of Treg cells in patients carrying rs414171 TT genotype could play a crucial role in persistent HBV infection by modulating HBV-specific immune responses [20], [21], [22].

Strong HBV-specific cytotoxic T cell (CTL) responses were assumed to be the central mechanism in HBV clearance and liver damage during HBV infection, and deficient Th1 immunity accompanied by inefficient CTL responses were found in patients with chronic HBV infection or therapeutic failure [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28]. IL-2 is an important Th1 cytokine for inducing polyclonality and multispecificity of the CTL responses following HBV infection. By blocking IL-2/JAK/STAT signal pathway,significantly higher production of CISH could remarkably decrease STAT5 signaling and depress the function of CD8+ T cells, which could possibly explain why a patient bearing the rs41417 TT genotype has a greater risk for persistent HBV infection.

In conclusion, this study suggests that the polymorphisms of rs414171 and rs2239751 in CISH gene could possibly be linked to persistent HBV infection in Chinese HBV patients. However, the role of CISH in T cell biology remains unclear with some contradictory findings [29], [30]. Further studies are needed to validate our results and clarify the potential functions of human CISH in HBV infection.

Supporting Information

Primer sequences used for amplification of CISH gene.

(DOC)

Funding Statement

This work was financially supported by the First Affiliated Hospital of Chengdu Medical College and the Health Department of Sichuan Province. The funders had no role role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Liang TJ (2009) Hepatitis B:the virus and disease. Hepatology 49: S13–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nishida N, Sawai H, Matsuura K, Sugiyama M, Ahn SH, et al. (2012) Genome-wide association study confirming association of HLA-DP with protection against chronic hepatitis Band viral clearance in Japanese and Korea. PLoS One 7: e39175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Deng G, Zhou G, Zhai Y, Li S, Li X, et al. (2004) Association of estrogen receptor alpha polymorphisms with susceptibility to chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Hepatology 40: 318–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mbarek H, Ochi H, Urabe Y, Kumar V, Kubo M, et al. (2011) A genome-wide association study of chronic hepatitis B identified novel risk locus in a Japanese population. Hum Mol Genet 20: 3884–3892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yoshimura A, Nishinakamura H, Matsumura Y, Hanada T (2005) Negative regulation of cytokine signaling and immune responses by SOCS proteins. Arthritis Res Ther 7: 100–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yoshimura A, Ohishi HM, Aki D, Hanada T (2004) Regulation of TLR signaling and inflammation by SOCS family proteins. J Leukoc Biol 75: 422–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Palmer DC, Restifo NP (2009) Suppressors of cytokine signaling(SOCS) in T cell differentiion,maturation,and function. Trends Immunol 30: 592–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Trengove MC, Ward AC (2013) SOCS proteins in development and disease. Am J Clin Exp Immunol 2: 1–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tsao JT, Kuo CC, Lin SC (2008) The analysis of CIS, SOCS1, SOSC2 and SOCS3 transcript levels in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis patients. Clin Exp Med 8: 179–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. De Andrés MC, Imagawa K, Hashimoto K, Gonzalez A, Goldring MB, et al. (2011) Suppressors of cytokine signaling(SOCS) are reduced in osteoarthritis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 407: 54–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Khor CC, Vannberg FO, Chapman SJ, Wong SH, Walley AJ, et al. (2010) CISH and susceptibility to infectious diseases. N Engl J Med 362: 2092–2101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tong HV, Toan NL, Song le H, Kremsner PG, Kun JF, et al. (2012) Association of CISH -292A/T genetic variant with hepatitis B virus infection. Immunogenetics 64: 261–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Di Cristofaro J, Silvy M, Chiaroni J, Bailly P (2010) Single PCR multiplplex SNaPshot reaction for detection of eleven blood group nucleotide polymorphis:optimization,validation,and one year of routine clinical use. J Mol Diagn 12: 453–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Borgés S, Moudilou E, Vouyovitch C, Chiesa J, Lobie P, et al. (2008) Involvement of a JAK/STAT pathway inhibitor: cytokine inducible SH2 containing protein in breast cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol 617: 321–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Li S, Chen S, Xu X, Sundstedt A, Paulsson KM, et al. (2000) Cytokine-induced Src homology 2 protein(CIS) promotes T cell receptor-mediated proliferation and prolongs survival of activated T cells. J Exp Med 191: 985–994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yang XO, Zhang H, Kim BS, Niu X, Peng J, et al. (2013) The signaling suppressor CIS controls proallergic T cells development and allergic airway inflammation. Nat Immunol 14: 732–740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chen S, Anderson PO, Sjiogren HO, Wang P, Li SL (2003) Functional association of cytokine-induced SH2 protein and protein kinase C in activated T cells. Int Immunol 15: 403–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Periasamy S, Dhiman R, Barnes PF, Paidipally P, Tvinnereim A, et al. (2011) Programmed death 1 and cytokine inducible SH2-containing protein dependent expansion of regulatory T cells upon stimulation with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Infection Dis 203: 1256–1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gupta S, Manicassamy S, Vasu C, Kumar A, Shang W, et al. (2008) Diffential requirement of PKC-theta in the development and function of natural regulatory T cells. Mol Immunol 46: 213–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Peng G, Li S, Wu W, Sun Z, Chen Y, et al. (2008) Circulating CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells correlate with chronic hepatitis B infection. Immunology 23: 57–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Barboza L, Salmen S, Goncalves L, Colmenares M, Peterson D, et al. (2007) Antigen-induced regulatory T cells in HBV chronically infectioned patients. Virology 368: 41–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Stoop JN, van der Molen RG, Baan CC, van der Laan LJ, Kuipers EJ, et al. (2005) Regulatory T cells contribute to the impaired immune response in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Hepatology 41: 771–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sprengers D, van der Molen RG, Kusters JG, De Man RA, Niesters HG, et al. (2006) Analysis of intrahepatic HBV-specific cytotoxic T-cells during and after acute HBV infection in humans. J Hepatpl 45: 182–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Maini MK, Boni C, Lee CK, Larrubia JR, Reignat S, et al. (2000) The role of virus-specific CD8(+) cells in liver damage and viral control during persistent hepatitis B virus infection. J Exp Med 191: 1269–8120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Maini MK, Boni C, Ogg GS, King AS, Reignat S, et al. (1999) Direct ex vivo analysis of hepatitis B virus-specific CD8(+) T cells associated with the control of infection. Gastroenterology 117: 1386–1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Maini MK, Bertoletti A (2000) How can the cellular immune response control hepatitis B virus replication? J Viral Hepat 7: 321–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jung MC, Pape GR (2002) Immunology of hepatitis B infection. Lancet Infect Dis 2: 43–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tsai SL, Sheen IS, Chien RN, Chu CM, Huang HC, et al. (2003) Activation of Th1 immunity is a common immune mechanism for the successful treatment of hepatitis B and C: tetramer assay and therapeutic implications. J Biomed Sci 10: 120–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Palmer DC, Restifo NP (2009) Suppressors of cytokine signaling(SOCS) in T cell differential,maturation,and dunction. Trend Immunol 30: 592–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Miah MA, Yoon CH, Kim J, Jang J, Seonq YR, et al. (2012) CISH is induced during DC development and regulates DC-mediated CTL activation. Eur J Immunol 42: 58–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Primer sequences used for amplification of CISH gene.

(DOC)