Abstract

Background

Abnormal task-related activation in primary motor cortices (M1) has been consistently found in functional imaging studies of subcortical stroke. Whether the abnormal activations are associated with neuronal alterations in the same or homologous area is not known.

Objective

Our goal was to establish the relationships between M1 measures of motor task-related activation and a neuronal marker, N-acetylaspartate, in patients with severe to mild hemiparesis.

Methods

Eighteen survivors of an ischemic subcortical stroke (confirmed on T2-weighted images) at more than six months post-onset and sixteen age- and sex-matched right-handed healthy controls underwent functional MRI during a handgrip task (impaired hand in patients, dominant hand in controls) and proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS) imaging. Spatial extent and magnitude of blood oxygen level-dependent response (or activation) and N-acetylaspartate levels were measured in each M1. Relationships between activation and N-acetylaspartate were determined.

Results

Compared to controls, patients had greater extent of contralesional (ipsilateral to impaired hand, p<.001) activation, higher magnitude of activation and lower N-acetylaspartate in both ipsilesional (p=.008 and p<.001 respectively) and contralesional (p<.0001, p<.05) M1. There were significant negative correlations between extent of activation and N-acetylaspartate in each M1 (p=.02) and a trend between contralesional activation and ipsilesional N-acetylaspartate (p=.08) in patients but not in controls.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that greater neuronal recruitment could be a compensatory response to lower neuronal metabolism. Dual-modality imaging may be a powerful tool for investigating relationships between complementary data regarding post-stroke brain reorganization.

Keywords: subcortical stroke, primary motor cortex, 1H-MRS, fMRI, functional-biochemistry relationship

Introduction

Stroke remains the leading cause of motor disability among adults1. A major contributor to disability is persistent arm/hand motor impairment2. Stroke survivors show altered brain activation patterns in both hemispheres on functional imaging studies. Specifically, execution of simple movements with the impaired arm is associated with increased activation in ipsilesional (same as the stroke) non-motor areas3, contralesional (opposite to the stroke) motor areas4-6, and bilateral premotor areas5, 7. Successful recovery occurs in patients who return to relatively normal patterns of brain activation, whereas patients who show persistent bilateral cortical activation typically have poorer recovery8, 9.

Although the normalization of activation in the ipsilesional M1 (iM1) is generally associated with return of arm motor function9-11, the relationship between contralesional M1 (cM1) activation and arm motor recovery remains under debate. Studies using transcranial magnetic stimulation12-14 or cathodal transcranial direct current stimulation15, 16 suggest that cM1 is recruited to compensate for damaged crossed pathways17. Some argue that the cM1 recruitment reflects the recruitment of un-crossed pathways4, 18, although there is no evidence that contralesional activation represents firing of uncrossed corticospinal tract (CST) fibers, which would be expected to involve proximal rather than distal movements19. Contralesional M1 recruitment might also represent an epiphenomenon reflecting either a diffuse recruitment of the motor networks driven by higher orders areas during a task performance18, or a dendritic overgrowth due to overuse of the healthy hand. Hence, although the exact role of cM1 in recovery remains elusive, interactions between cM1 and iM1 are likely to be critical for motor recovery, particularly in patients with poor recovery5, 20-22.

Although the neural mechanisms underlying the M1 functional changes after stroke remain largely unknown, non-invasive proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS) studies have found lower M1 levels of N-acetylaspartate (NAA), particularly in the ipsilesional hemisphere23-26. Though the precise biological function remains uncertain, reduced NAA levels are though to index neuronal loss, dysfunction, or both27. This suggests that changes in activation of the M1 may be a consequence of, or a compensation for, an underlying neuronal impairment28. However, no study to date has acquired these measures within the same area in the same patient.

In the present study, we sought to clarify the neural basis underlying the activation changes seen in chronic subcortical stroke using a combined fMRI and 1H-MRS approach. We focused primarily on the primary motor cortex (M1), given previous evidence of its major involvement in motor recovery after stroke9-11. For the fMRI paradigm, we used the handgrip task that has been shown to robustly activate M15, 26. We then acquired 1H-MRS measures from the activated M1 regions. Based on previous work, we hypothesized that patients would show increased handgrip-related activation, particularly in cM1, and decreased NAA levels in both M1s. We also determined the relationships between activation and NAA within and between M1s. We hypothesized that inverse relationships would constitute evidence in support of compensatory M1 activation driven by a neuronal impairment.

Methods

Participants

Eighteen right-handed stroke patients and 16 right-handed healthy controls provided written informed consent to this study, which was approved by the institutional ethics committee. Of these, 11 patients and 10 controls participated in an earlier study that explored M1 neurochemical levels26.

Patients were required to have a first-ever ischemic subcortical stroke at least six months previously, have M1 intact on T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and be able to perform a handgrip task (Fugl-Meyer Upper Extremity Scale (FMUE)≥10). Patients were also required to understand simple instructions (Token test) and have no visual attention deficits (Cancellation test), apraxia (clinical observation of the use of scissors to cut paper and making coffee), or other neurological or psychiatric diseases. Patients were on anti-hypertensive (75%), cholesterol-lowering (62%), and/or antiplatelet (81%) therapy, but were not receiving rehabilitation treatment.

Age-, sex-, and education-matched healthy controls, without neurological or psychiatric disorders, participated.

Patients attended an initial screening session to assess arm motor impairment using FMUE (where a score of 66 indicates no impairment29). All participants completed one magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) session, including brain structural, functional, and 1H-MRS imaging (3T Allegra MR system, Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany). The total duration for the MRI session was about 45 min. Full details of the MRI protocol appear elsewhere26, 30.

Structural MRI

Two structural data sets were acquired, T1-weighted structural (TR=2300ms; TE=3ms; FOV=240mm; matrix=256×256; resolution=1×1×1mm3) and T2-weighted structural (TR=4800ms; TE1/TE2=18/106ms; FOV=240mm; matrix=256×256; slice thickness=5mm, no gap), to: (i) confirm lesion location, (ii) exclude other pathological conditions, (iii) estimate the brain tissue volume in spectroscopic voxels (see below), (iv) quantify lesion volume: Lesions were defined as tissue having abnormal high signal on T2-weighted images and as subcortical if they include >50% of subcortical tissue31. We manually traced the lesion slice-by-slice on axial T2-weigthed images (MedINRIA, Cedex, France, wwwsop.inria.fr/asclepios/software/MedINRIA/). Finally, we estimated the volume using MIPAV (http://mipav.cit.nih.gov/); (v) identify white matter hyperintensities (WMH; the Fazekas scale32: range 0 to 3, 0 and 1 being considered normal in the elderly); and (vi) estimate global grey matter volume (SIENAX33).

Functional MRI

Blood Oxygenation Level Dependent (BOLD; TR=2000ms; TE=50ms; 25 slices; slice thickness=5mm; 0 skip; 100 data points; resolution: 5×5mm2) was acquired while performing a visually-cued handgrip, as described previously26, 30. For this task, we used an MRI-compatible device, consisting of an air-filled polymer bulb connected to a pressure transducer (placed outside of the scanner field). During the handgrip, pressure values were detected by transducer and presented graphically to the participant (LabVIEW 7.1, National Instruments, Texas). Patients performed the task with the impaired hand and controls used the right (dominant) hand. Since the ability to perform handgrip returns earlier than fractioned finger movements34, handgrip task is a well-suited task to study patients with a wide range of recovery. Thus, we were able to study patients with mild to severe hemiparesis.

Each participant's maximal voluntary contraction (MVC) on the handgrip task was measured prior to scanning. Participants generated MVC on three five-second trials; the highest peak pressure produced was used as the MVC. During scanning, a target pressure of 25% of MVC was displayed graphically while participants performed the handgrip task. This target pressure was used to control for effort across all participants. Upon reaching the target pressure, the grip was released. Practice outside the scanner minimized unwanted movements and made the participant confortable with the task.

We used a block design consisting of two alternating conditions, movement and rest. In the movement condition, each handgrip was cued by the appearance of the word ‘MOVE’. In the resting condition, participants were instructed (by word cue ‘STOP’) to remain motionless. The word cue was repeated five times, every 4s, for each condition (20s each) and the run consisted of 25 cued events (handgrip) and 25 null events (one run=3min 28s).

BOLD data analysis

The fMRI analysis was performed off-line using Brain Voyager software (Brain Innovation B.V., Maastricht, Netherlands). The first 2 volumes of each scan were discarded to avoid T1 saturation effects. Preprocessing included motion correction using rigid body transformation, estimating six parameters (three translational and three rotational). Inspection of these parameters found that none of the participants moved their head more than 2 mm in any direction; spatial smoothing using 4mm Gaussian filter, to permit valid statistical inferences based on Gaussian random field theory; mean-based intensity normalization of all volumes by the same factor; and high-pass temporal filtering at 0.01Hz, to remove low frequency confounds.

Without knowledge of the activation patterns, M1 was outlined on the coincident T1-weighted image using standard sulcal and gyral landmarks: anterior bank of the central sulcus with the caudal border lying in the depth of the central sulcus close to its fundus and anterior border abutting Brodmann area 635, and the total voxels was counted for each M1. We then counted the activated voxels in M1 using a Bonferroni corrected p=0.01 (see below). The ratio between the number of activated voxels and the total voxels in each M1 represents the spatial extent of activation (SEA)36. The general linear model was used to contrast BOLD signal between movement and rest conditions, modeled by a boxcar function with hemodynamic response modification (predictor movement). The voxel values were considered significant if the activation survived a Bonferroni-corrected significance threshold of 0.01. We selected a cluster of 100 contiguous voxels for hand representation in each M1. Signal intensity versus time curves were examined for each significant activation and a mean signal change (or MSC) in movement vs. rest condition was calculated.

Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy imaging (1H-MRSI)

Immediately after the BOLD acquisition was completed, we analyzed the fMRI results using the scanner analysis software to locate the M1 activation for 1H-MRSI positioning. These results were not used for the subsequent analyses. Point Resolved Spectroscopy or PRESS was used (TE=30ms; TR=1500ms; FOV=160mm2; matrix=16×16; slice thickness=15mm; in-plane resolution=5×5mm2; spectral width=1200Hz). We minimized lipid artifact from the scalp by using eight outer voxel suppression bands (thickness=30 mm) around the volume of interest. We used automatic and manual shimming to achieve full-width at half maximum of <20Hz of the water signal from the entire excitation volume.

NAA concentrations were calculated using LCModel37. Using custom-designed software (Matlab v7.1) to overlay the LCModel output, BOLD images, and segmented T1-weighted images (SPM2 Department of Cognitive Neurology, London, UK), we selected three spectroscopic voxels in the hand representation in M126 with a signal-to-noise ratio >10 and >75% brain tissue (BT, grey+white matter from SPM2 segmentation) and NAA Cramer-Rao lower bounds <20%. If M1 activation was absent, we selected the spectroscopic voxels corresponding to the “hand knob” in M1 (http://neuro.imm.dtu.dk/services/jerne/ninf/voi.html) (Fig. 1A).

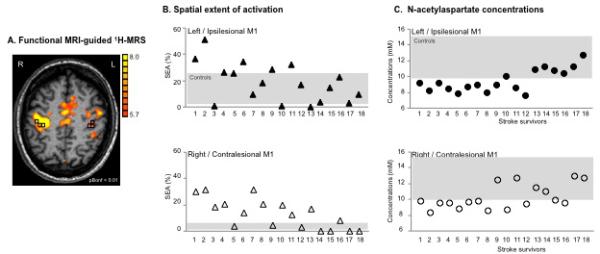

Fig. 1.

(A) Motor-related cortical activation during a handgrip task executed with the impaired right hand in a 45-age old patient who had experienced infarct involving the left basal ganglia and corona radiata (Patient 7, Table 1). Spectroscopic voxels (black squares) were selected in the hand knob area (based on M1 activation and/or anatomical landmarks in case the activation tended to zero). The front of the brain is upwards. L=left, R=right. (B) Spatial extent of M1 activation during handgrip executed with the impaired hand (%) and (C) NAA concentrations (mM) in both ipsilesional (upper row, closed symbols) and contralesional (lower row, open symbols) M1 are shown for individual patient. Stroke survivors are ranked by FMUE scores (see Table 1, with #1, no arm motor impairment; #18, severely impaired). Grey rectangles signify the range of spatial extent activation (B) and NAA concentrations (C) in left (upper row) and right (lower row) M1 in healthy controls.

We corrected metabolite concentrations as follows: c=cLCModel/BT where c is the BT-corrected concentration, cLCModel is the concentration in institutional units (from LCModel), and BT is the estimated brain tissue. The BT-corrected concentration was then converted into molar concentrations (millimoles per kilogram wet weight brain tissue)26.

Statistical analysis

Variables (demographic: age, years of education; clinical: FMUE scores, time post-stroke, lesion volume, WMH, global grey matter volume) and M1 outcomes (primary: NAA, SEA; secondary: MSC) were described by means and standard deviations. Since lesion volume was not normally distributed, we used a logarithmic transform. To quantify differences in SEA and MSC between M1s, we used the activation laterality index3, 38 (LI =(C-I)/(C+I), where C and I represents the contralateral M1 SEA (MSC) or ipsilateral M1 SEA (MSC) to the hand performing the motor task, respectively. The LI can range from 1.0 (all activity in the contralateral M1) to −1.0 (all activity in the ipsilateral M1).

Between-group differences in demographic variables and M1 outcomes were explored using parametric (t-test) or non-parametric (Wilcoxon rank-sum test) statistics, depending on their distributions.

Within group, between-hemisphere differences in variables were assessed using 2-tailed paired t-tests. We used Spearman rank order correlation to analyze the relationships between (i) primary outcomes and clinical variables, and (ii) SEA, MSC, and NAA within and across M1. The significance level was set at p<0.05 (SPSS 18.0, SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL).

Results

Participant characteristics

Patients

Stroke survivors had experienced a single subcortical infarction between 6 and 144 months prior to scanning (mean±SD=37.4±36.7mo) leading to moderate arm paresis (FMUE=42.9±16.9). Lesion volume varied from 180mm3 to 25,340mm3 (8,575.4±15,239.0mm3). Twelve patients had left-sided infarcts. Fourteen survivors had infarcts in the basal ganglia, with extension to posterior limb of the internal capsule (PLIC) in seven patients, to anterior limb (ALIC) in three patients, to both PLIC and ALIC in two patients, and to corona radiata in five patients. One patient had an infarct in the PLIC with extension to thalamus, one had an ALIC infarction, one survivor had cerebral peduncles infarction, and one had an infarct in pons. Fazekas scores varied between 0 and 1 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical stroke characteristics.

| Patient | Age/Sex | Time after stroke (mo) | Lesion location | Lesion volume (mm3) | Fazekas | FMUE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 61/M | 24 | L / BG, IC, CR | 25,339.9 | 1 | 10 |

| 2 | 58/M | 27 | R / PLIC, BG | 553.7 | 1 | 24 |

| 3 | 59/M | 144 | L / PLIC, BG | 1,451.9 | 0 | 25 |

| 4 | 44/F | 106 | L / BG, IC, CR | 17,881.3 | 0 | 26 |

| 5 | 56/F | 6 | R / PLIC, BG | 6,902.9 | 0 | 29 |

| 6 | 61/M | 12 | L/Pons | 1,445.8 | 0 | 30 |

| 7 | 45/M | 27 | L / BG, CR | 180.4 | 0 | 36 |

| 8 | 71/M | 26 | R / PLIC, BG | 1,192.7 | 1 | 37 |

| 9 | 73/M | 60 | R / ALIC, BG | 21,960.35 | 0 | 41 |

| 10 | 65/M | 36 | R / BG, CR | 271.6 | 1 | 42 |

| 11 | 61/F | 27 | L / CP | 2357.2 | 1 | 50 |

| 12 | 56/M | 23 | L / ALIC | 490.4 | 1 | 50 |

| 13 | 46/F | 8 | R / BG | 737.4 | 1 | 58 |

| 14 | 54/F | 12 | L /ALIC/genu, BG | 450.0 | 0 | 60 |

| 15 | 48/F | 11 | L / PLIC, BG | 60,450.3 | 0 | 61 |

| 16 | 46/M | 52 | L / PLIC, BG | 740.0 | 0 | 63 |

| 17 | 68/M | 63 | L / PLIC, T | 1,449.3 | 0 | 65 |

| 18 | 57/M | 6 | L / BG, CR | 10501.9 | 1 | 66 |

M, male; F, female; mo, months; L, left; R, right; BG, basal ganglia; CR, corona radiata; PLIC, posterior limb internal capsule; ALIC, anterior limb internal capsule; CP, cerebral peduncle; T, thalamus; mm=millimeters; Fazekas scale for white matter hyperintensities FMUE (0 to 3, 0 and 1 normal for elderly), Fugl-Meyer Upper Extremity, normal=66, as recorded at the recruitment into study, Fazekas scale (normal for elderly people=0 and 1).

Patients vs. Controls

Age (57.4±9.1 vs. 49.9±13.7yrs, NS), male/female distribution (12/6 vs. 10/6, NS), or years of education (13.6±1.7 vs. 14.0±2.5yrs, NS) did not differ between patients and controls. We compared the iM1 to the left M1 (lM1) from controls based on (i) lack of M1 NAA lateralization in healthy26,30, (ii) similar handgrip activations for both dominant and non-dominant hands in healthy5, and (iii) most (67%) of our patients had left hemisphere injury.

Spatial extent of handgrip-related activation in primary motor cortex

Controls

A robust contralateral BOLD response was seen in all controls while using the right (dominant) hand (lM1, 13.0±8.8% of total lM1, Fig. 1B for range of SEA). Ipsilateral, i.e., right, M1 activation was significantly smaller (0.6±1.4%, p<.001) and was recorded in only 5 out of 16 controls. The LI was 0.9, suggesting dominant contralateral M1 activation.

Patients

Patients consistently activated both M1s while using the impaired arm (iM1, 18.6±14.7%; cM1, 13.0±11.2.0%). No significant differences between iM1 activation and cM1 activation were found (p=.2).

Spatial extent of M1 activation was significantly correlated with FMUE scores, but not with lesion volume, global grey matter volume, or time after stroke (Table 2).

Table 2.

Spearman correlations (r, p-value) between primary motor cortex (M1) outcomes, measured bilaterally, and clinical variables in stroke survivors.

| Fugl-Meyer Upper Extremity | Lesion volume | Global grey matter volume | Time after stroke | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N-acetylaspartate (mM) | ||||

| Ipsilesional | 0.63, .005 | 0.42, .08 | 0.25, .3 | −0.13, .6 |

| Contralesional | 0.55, .02 | −0.02, .9 | 0.23, .4 | −0.09, .7 |

| Spatial extent of activation (%) | ||||

| Ipsilesional | −0.48, .04 | −0.05, .8 | 0.04, .9 | −0.04, .9 |

| Contralesional | −0.77, <.01 | 0.11, .6 | 0.15, .5 | 0.33, .2 |

Subgroup analysis (Table 3) showed no significant differences in M1 activation based on stroke lateralization, left vs. right hemisphere, or internal capsule location, PLIC vs. ALIC.

Table 3.

Comparisons of mean (SD) of primary motor cortex (M1) outcomes in patients with left vs. right stroke and with PLIC vs. ALIC stroke.

| Left hemisphere stroke (n=12, FMUE=45.2±19.1, time after stroke=32.7±28.4mo) | Right hemisphere stroke (n=6, FMUE=38.5±11.6, time after stroke=46.8±51.6mo) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N-acetylaspartate (mM) | |||

| Ipsilesional | 9.6±1.6 | 9.3±1.1 | .7 |

| Contralesional | 11.3±1.6 | 10.1±1.5 | .8 |

| Spatial extent of activation (%) | |||

| Ipsilesional | 22.5±14.4 | .1 | |

| Contralesional | 11.7±11.9 | 15.7±10.3 | .5 |

| PLIC stroke (n=7, FMUE=43.4±18.8, time after stroke=47.0±47.4mo) | ALIC stroke (n=3, FMUE=50.3±9.5, time after stroke=32.0±24.9mo) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N-acetylaspartate (mM) | |||

| Ipsilesional | 9.3±1.4 | 9.3±1.2 | .9 |

| Contralesional | 9.6±1.6 | 10.9±1.5 | .2 |

| Spatial extent of activation (%) | |||

| Ipsilesional | 19.3±16.8 | 16.6±12.4 | .8 |

| Contralesional | 11.8±12.1 | 2.4±2.2 | .2 |

n, number of patients; FMUE, Fugl-Meyer Upper Extremity, mo, months

Patients vs. controls

Although patients, as a group, generally activated a larger iM1 than controls, this did not reach statistical significance (p=.2). Five out of 18 patients showed greater SEA than the range recorded from uninjured group (Fig. 1B). As expected, cM1 SEA in patients was considerably greater than in controls (13.0±11.2% vs. 0.6±1.4%, p<.001). Eleven patients activated more cM1 compared to the range of our control group (Fig. 1B). We also found altered lateralization for the patient group. The LI was 0.2, reflecting an increased involvement of cM1.

Magnitude of handgrip-related activation in primary motor cortex

Patients vs. controls

The magnitude of M1 activation, as measured by MSC, was significantly higher in patients than in controls (iM1: 0.9±0.3% vs. lM1, 0.7±0.2%, p=.008; cM1: 0.8±0.7% vs. rM1, 0.01±0.02%, p<.001). Activation was also less lateralized in patients compared to controls (LI: 0.05 vs. 0.95 in controls), similar to the results for SEA (see above).

N-acetylaspartate levels in primary motor cortex

1H-MRS spectra with good signal-to-noise ratios were obtained consistently from both control and stroke participants. Similar percentages of brain tissue within spectroscopic voxels were found between groups (iM1: 89.0±6.2% vs. lM1, 88.8±7.2%, p=.9; cM1: 87.0±7.9% vs. rM1, 88.9±5.0%, p=.4).

Controls

Consistent with our previous findings26, 30, similar NAA levels were found in lM1 and rM1 in healthy controls (11.5±1.4mM vs. 11.7±1.9mM, p=.8; see Fig. 1C for range of NAA).

Patients

Ipsilesional NAA was significantly lower than contralesional NAA (9.5±1.4mM vs. 10.4±1.6mM, p=.02). Significant positive correlations were found between NAA and FMUE (Table 2), suggesting that NAA is lower in both M1s in patients with poorer outcomes (Fig. 1C). There were no significant correlations between NAA and stroke volume, global grey matter volume, or time post-stroke (Table 2). NAA levels were not significantly different in left vs. right stroke or in PLIC vs. ALIC stroke (Table 3).

Patients vs. controls

Mean NAA levels in each M1 in patients were significantly lower than those in controls (iM1 vs. lM1 p<.001; cM1 vs. rM1 p<.05).

Relationships between spatial extent and magnitude of activation and NAA levels in primary motor cortex

Controls

No significant correlations were detected between SEA and NAA level within lM1 (Spearman r=−0.17, p=.5) or rM1 (r=0.36, p=.2) nor between MSC and NAA (lM1, r=−0.08, p=.8; rM1, r=−0.04, p=.9).

Patients

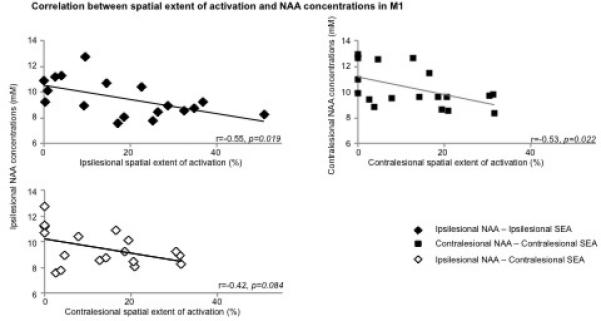

In contrast, patients showed a significant negative correlation between SEA and NAA in each M1 (ipsilesional, r=−0.55, p=.02; contralesional, r=−0.53, p=.02; Fig. 2, upper row). Patients showed weaker negative correlation between cM1 SEA and iM1 NAA levels (r=−0.42, p=.08, Fig. 2A, lower row). Although correlations between MSC and NAA within or across M1s were all negative, similar to SEA, (iM1, r=−0.14, p=.6; cM1, r=−0.38, p=.1; iM1 MSC -cM1 NAA, r=−0.24, p=.4; cM1 MSC -iM1 NAA, r=−0.42, p=.1), they did not reach statistical significance.

Fig. 2.

Scatterplot of Spearman correlations between (A) ipsilesional NAA concentrations (mM) and ipsilesional (top row, black diamond, r=−0.55, p=0.02) and contralesional (low row, white diamond, r=−0.42, p=0.08) handgrip-related spatial extent of activation (SEA, %), and between (B) NAA and SEA within contralesional M1 (square, r=−0.53, p=0.02) in stroke patients.

Discussion

Although numerous studies have used either fMRI or 1H-MRS to examine brain reorganization after stroke, to our knowledge this is the first report that integrates these modalities to investigate the relationships between activation and neuronal metabolism measures in M1 after stroke.

Handgrip-related activation in primary motor cortex in chronic subcortical stroke

As reported in previous studies5, 20, the activation pattern associated with impaired hand movement consistently included both ipsilesional and contralesional M1. Our data also showed that a greater motor deficit is associated with a greater bilateral M1 activation5, 20-22. Increased ipsilesional activation is likely to reflect a recruitment of larger pool of neurons with intact axons39 probably due to a loss of recurrent inhibition onto surrounding pyramidal cells40, changes in the properties of existing neuronal pathways41, and/or changes in anatomical connections between areas42. Our finding of greater contralesional activation might be due to altered inter-hemispheric inhibition14, dendritic overgrowth due to overuse of the healthy hand, recruitment of un-crossed CST fibers recruitment4, 19, and/or mirror movements43. An alternative explanation might be that patients with poor motor outcome might perceive the task as more complex resulting in greater bilateral M1 activation44. Although the effort levels of our task were matched at 25% of individual MVC, we did not control attention. Thus, we cannot rule out the possibility that attention differences contributed to larger M1activations.

N-acetylaspartate in primary motor cortex in chronic subcortical stroke

Our second finding of lower NAA corroborates prior reports in stroke23-26. Although the specific mechanism underlying lower NAA remains the topic of some conjecture, dysfunctional neurons may contain lower NAA due to less synthesis and/or release45. Indeed, in ipsilesional M1, dysfunctional neurons could result from distal ischemic axotomy46-48 and/or diaschisis, i.e., depressed neural activity in brain regions distant but structurally or functionally connected to the damaged brain area49, 50. Although it is unknown whether biochemical and/or electrophysiological changes described in surviving neurons with ischemic axotomy47, 48 are similar to those classically described in diaschitic neurons51, these changes are likely to be associated with impaired mitochondrial function, and hence NAA decline. The concept of metabolically depressed neurons is further supported by observation of morphological and biochemical cell body changes47, 48 after axonal injury, indicating that neurons shift from “transmitting” to “degenerative/regenerative” state55. Our findings of lower NAA in the contralesional M1, also confirm our prior work26 and might result from trans-hemispheric diaschisis51, 52.

Other explanations for lower NAA are also possible. NAA is involved in myelin/fatty acid synthesis and osmotic regulation, but these processes are unlikely to be altered in normal appearing cortex remote from the injury. Lower NAA can also result from dead neurons53. However, neuronal loss seems unlikely in M1 since there is little evidence of retrograde degeneration54 or cortical cell death after subcortical stroke55. Moreover, we found no differences in brain tissue volume in the spectroscopic voxels in patients compared to controls, which would be expected in the context of appreciable neuronal loss. Therefore, although lower NAA levels potentially reflect a variety of underlying mechanisms, in the context of the present findings, we consider that lower NAA levels suggest metabolically depressed neurons.

Correlation between handgrip-related activation and N-acetylaspartate in primary motor cortex in chronic subcortical stroke

Our third finding of a negative correlation between extent of activation and NAA levels in each M1 suggests that the amount of neuronal recruitment during a motor task is related to the magnitude of M1 metabolic abnormality. We speculate that the morphological and biochemical cell body changes after axonal injury in the ipsilesional M1, noted above, associated with increased synthesis of proteins associated with growth56 may support formation of new local intracortical connections42. For instance, these could recruit adjacent neurons with intact axons, i.e., pyramidal tract neurons, which potentially have similar muscle projections as the metabolically depressed neurons. Similarly, the changes in neuronal morphology in the contralesional M157 could be associated with a larger neuronal recruitment in this area. Moreover, the contralesional recruitment was also negatively correlated to ipsilesional NAA, suggesting that as the ipsilesional M1 neuronal compartment is increasingly compromised, the more contralesional M1 is recruited. This result is supported by recent findings that contralesional M1 activation correlates with ipsilesional motor pathway integrity58. This is a novel finding that requires further attention.

An alternative strategy for investigating BOLD activations is to examine the magnitude of signal changes. Our results are generally consistent with those from the SEA analysis discussed above i.e., the NAA levels were also negatively correlated to a modest extent with the magnitude of activation. Further studies are needed to elucidate the relationships between the BOLD signal and the physiological role of NAA in neurons.

Nevertheless, these findings help us to rule out the contribution of attention or mirror movements to enlarged M1 activation, as we would not expect underlying neuronal disturbances in the areas regularly recruited during normal motor programming. Further, contralesional dendritic overgrowth could be also omitted from our interpretation, based on our findings of lower contralesional M1 NAA levels.

Study limitations

We recruited a relatively large sample for a study of this type, i.e., imaging study after stroke. Since this was the first study to use a dual-imaging modality approach, we increased our statistical power by recruiting only survivors of sub-cortical stroke and examining only one cortical motor area, M1. We also chose to examine only one neurometabolite, NAA and asked a series of very focused questions. Nonetheless, there were some limitations. The focus on subcortical infarcts provides statistical power by minimizing patient variance, but limits our ability to explore the effects of infarct location on the relationships brain function-biochemistry. Similarly, since our analysis focused on M1, we cannot comment on the involvement of other brain regions that are critical to stroke recovery. Our focus on NAA means that we can make no comment on other brain metabolites such as glutamate and GABA. Clearly, future studies of the relationship between these metabolites and motor performance and recovery would be of great interest.

Our data could be explained, in part, by resting cerebral blood flow alterations, perhaps resulting from carotid stenosis. However, there is evidence that reduced resting cerebral blood flow also results in elevated choline and lactate59, which were not significantly altered in our sample (results not shown). Thus, we consider that carotid stenosis is not a significant contributor to our findings.

Finally, due to the point-spread function of 1H-MRSI, the effective voxel size is bigger than the nominal voxel size. Thus, we cannot rule out the possibility that our measurements include more than hand representation in each area.

Summary

Although overlapping processes underly functional M1 changes after stroke60, our findings suggest that one factor could be the altered neuronal metabolism in these areas. Thus, we advocate that functional MRI and 1H-MRS provide complementary probes of cerebral tissue that, when used together, improve our understanding of the cellular substrate of brain reorganization after stroke. Further use of such combined approaches might help us to better understand the mechanisms of recovery and develop better therapeutic approaches.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding: This work was supported by American Heart Association (0860041Z to CMC; 0655759Z to WMB). The Hoglund Brain Imaging Center is supported by a generous gift from Forrest and Sally Hoglund and National Institutes of Health (P30 AG 035382, P30 HD 002528, and UL1 TR000001). The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or its institutes.

Footnotes

Disclosure/Conflict of Interest

No duality of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Feigin VL, Lawes CM, Bennett DA, Barker-Collo SL, Parag V. Worldwide stroke incidence and early case fatality reported in 56 population-based studies: a systematic review. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:355–369. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70025-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lai SM, Studenski S, Duncan PW, Perera S. Persisting consequences of stroke measured by the Stroke Impact Scale. Stroke. 2002;33:1840–1844. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000019289.15440.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weiller C, Ramsay SC, Wise RJ, Friston KJ, Frackowiak RS. Individual patterns of functional reorganization in the human cerebral cortex after capsular infarction. Ann Neurol. 1993;33:181–189. doi: 10.1002/ana.410330208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nelles G, Contois KA, Valente SL, et al. Recovery following lateral medullary infarction. Neurology. 1998;50:1418–1422. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.5.1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ward NS, Brown MM, Thompson AJ, Frackowiak RS. Neural correlates of outcome after stroke: a cross-sectional fMRI study. Brain. 2003;126:1430–1448. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cramer SC, Nelles G, Benson RR, et al. A functional MRI study of subjects recovered from hemiparetic stroke. Stroke. 1997;28:2518–2527. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.12.2518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johansen-Berg H, Rushworth MF, Bogdanovic MD, Kischka U, Wimalaratna S, Matthews PM. The role of ipsilateral premotor cortex in hand movement after stroke. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:14518–14523. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222536799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marshall RS, Perera GM, Lazar RM, Krakauer JW, Constantine RC, DeLaPaz RL. Evolution of cortical activation during recovery from corticospinal tract infarction. Stroke. 2000;31:656–661. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.3.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ward NS, Brown MM, Thompson AJ, Frackowiak RS. Neural correlates of motor recovery after stroke: a longitudinal fMRI study. Brain : a journal of neurology. 2003;126:2476–2496. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johansen-Berg H, Dawes H, Guy C, Smith SM, Wade DT, Matthews PM. Correlation between motor improvements and altered fMRI activity after rehabilitative therapy. Brain. 2002;125:2731–2742. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calautti C, Naccarato M, Jones PS, et al. The relationship between motor deficit and hemisphere activation balance after stroke: A 3T fMRI study. Neuroimage. 2007;34:322–331. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takeuchi N, Tada T, Toshima M, Chuma T, Matsuo Y, Ikoma K. Inhibition of the unaffected motor cortex by 1 Hz repetitive transcranical magnetic stimulation enhances motor performance and training effect of the paretic hand in patients with chronic stroke. J Rehabil Med. 2008;40:298–303. doi: 10.2340/16501977-0181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fregni F, Pascual-Leone A. Hand motor recovery after stroke: tuning the orchestra to improve hand motor function. Cogn Behav Neurol. 2006;19:21–33. doi: 10.1097/00146965-200603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nowak DA, Grefkes C, Dafotakis M, et al. Effects of low-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the contralesional primary motor cortex on movement kinematics and neural activity in subcortical stroke. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:741–747. doi: 10.1001/archneur.65.6.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fregni F, Boggio PS, Mansur CG, et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation of the unaffected hemisphere in stroke patients. Neuroreport. 2005;16:1551–1555. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000177010.44602.5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boggio PS, Nunes A, Rigonatti SP, Nitsche MA, Pascual-Leone A, Fregni F. Repeated sessions of noninvasive brain DC stimulation is associated with motor function improvement in stroke patients. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2007;25:123–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ago T, Kitazono T, Ooboshi H, et al. Deterioration of pre-existing hemiparesis brought about by subsequent ipsilateral lacunar infarction. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74:1152–1153. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.8.1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Calautti C, Baron JC. Functional neuroimaging studies of motor recovery after stroke in adults: a review. Stroke. 2003;34:1553–1566. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000071761.36075.A6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foltys H, Krings T, Meister IG, et al. Motor representation in patients rapidly recovering after stroke: a functional magnetic resonance imaging and transcranial magnetic stimulation study. Clin Neurophysiol. 2003;114:2404–2415. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(03)00263-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cramer SC, Crafton KR. Somatotopy and movement representation sites following cortical stroke. Exp Brain Res. 2006;168:25–32. doi: 10.1007/s00221-005-0082-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perez MA, Cohen LG. The corticospinal system and transcranial magnetic stimulation in stroke. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2009;16:254–269. doi: 10.1310/tsr1604-254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lotze M, Beutling W, Loibl M, et al. Contralesional motor cortex activation depends on ipsilesional corticospinal tract integrity in well-recovered subcortical stroke patients. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2012;26:594–603. doi: 10.1177/1545968311427706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Munoz Maniega S, Cvoro V, Chappell FM, et al. Changes in NAA and lactate following ischemic stroke: a serial MR spectroscopic imaging study. Neurology. 2008;71:1993–1999. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000336970.85817.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kang DW, Roh JK, Lee YS, Song IC, Yoon BW, Chang KH. Neuronal metabolic changes in the cortical region after subcortical infarction: a proton MR spectroscopy study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;69:222–227. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.69.2.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kobayashi M, Takayama H, Suga S, Mihara B. Longitudinal changes of metabolites in frontal lobes after hemorrhagic stroke of basal ganglia: a proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. Stroke. 2001;32:2237–2245. doi: 10.1161/hs1001.096621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cirstea MC, Brooks WM, Craciunas SC, et al. Primary motor cortex - a functional MRI-guided proton magnetic resonance spectroscopic study. Stroke. 2011;42:1004–1009. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.601047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moffett JR, Ross B, Arun P, Madhavarao CN, Namboodiri AM. N-Acetylaspartate in the CNS: from neurodiagnostics to neurobiology. Prog Neurobiol. 2007;81:89–131. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hao X, Xu D, Bansal R, et al. Multimodal magnetic resonance imaging: The coordinated use of multiple, mutually informative probes to understand brain structure and function. Human brain mapping. 2013;34:253–271. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brunnstrom S. Motor testing procedures in hemiplegia: based on sequential recovery stages. Physical therapy. 1966;46:357–375. doi: 10.1093/ptj/46.4.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Craciunas CS, Brooks MW, Nudo RJ, et al. Motor and premotor cortices in subcortical stroke: proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy measures and arm motor impairment. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2013;XX(X):1–10. doi: 10.1177/1545968312469835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schouten EA, Schiemanck SK, Brand N, Post MW. Long-term deficits in episodic memory after ischemic stroke: evaluation and prediction of verbal and visual memory performance based on lesion characteristics. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2009;18:128–138. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2008.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fazekas F, Chawluk JB, Alavi A, Hurtig HI, Zimmerman RA. MR signal abnormalities at 1.5 T in Alzheimer's dementia and normal aging. AJR American journal of roentgenology. 1987;149:351–356. doi: 10.2214/ajr.149.2.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith SM, Zhang Y, Jenkinson M, et al. Accurate, robust, and automated longitudinal and cross-sectional brain change analysis. Neuroimage. 2002;17:479–489. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heller A, Wade DT, Wood VA, Sunderland A, Hewer RL, Ward E. Arm function after stroke: measurement and recovery over the first three months. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1987;50:714–719. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.50.6.714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Geyer S, Matelli M, Luppino G, Zilles K. Functional neuroanatomy of the primate isocortical motor system. Anat Embryol (Berl) 2000;202:443–474. doi: 10.1007/s004290000127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Duvernoy H, et al. The Human Brain: Surface, Three-Dimensional Section Anatomy and MRI. Springer-Verlag; New York, NY: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Provencher SW. Automatic quantitation of localized in vivo 1H spectra with LCModel. NMR Biomed. 2001;14:260–264. doi: 10.1002/nbm.698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lotze M, Markert J, Sauseng P, Hoppe J, Plewnia C, Gerloff C. The role of multiple contralesional motor areas for complex hand movements after internal capsular lesion. J Neurosci. 2006;26:6096–6102. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4564-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Newton JM, Ward NS, Parker GJ, et al. Non-invasive mapping of corticofugal fibres from multiple motor areas--relevance to stroke recovery. Brain : a journal of neurology. 2006;129:1844–1858. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ghosh S, Porter R. Morphology of pyramidal neurones in monkey motor cortex and the synaptic actions of their intracortical axon collaterals. The Journal of physiology. 1988;400:593–615. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ward NS. The neural substrates of motor recovery after focal damage to the central nervous system. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;87:S30–35. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2006.08.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dancause N, Barbay S, Frost SB, et al. Extensive cortical rewiring after brain injury. J Neurosci. 2005;25:10167–10179. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3256-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Leocani L, Cohen LG, Wassermann EM, Ikoma K, Hallett M. Human corticospinal excitability evaluated with transcranial magnetic stimulation during different reaction time paradigms. Brain : a journal of neurology. 2000;123(Pt 6):1161–1173. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.6.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Johansen-Berg H, Matthews PM. Attention to movement modulates activity in sensori-motor areas, including primary motor cortex. Exp Brain Res. 2002;142:13–24. doi: 10.1007/s00221-001-0905-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bates TE, Strangward M, Keelan J, Davey GP, Munro PM, Clark JB. Inhibition of N-acetylaspartate production: implications for 1H MRS studies in vivo. Neuroreport. 1996;7:1397–1400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Willis DE, Twiss JL. The evolving roles of axonally synthesized proteins in regeneration. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2006;16:111–118. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hinman JD, Rasband MN, Carmichael ST. Remodeling of the axon initial segment after focal cortical and white matter stroke. Stroke. 2013;44:182–189. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.668749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schafer DP, Jha S, Liu F, Akella T, McCullough LD, Rasband MN. Disruption of the axon initial segment cytoskeleton is a new mechanism for neuronal injury. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2009;29:13242–13254. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3376-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Seitz RJ, Azari NP, Knorr U, Binkofski F, Herzog H, Freund HJ. The role of diaschisis in stroke recovery. Stroke. 1999;30:1844–1850. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.9.1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Frost SB, Barbay S, Friel KM, Plautz EJ, Nudo RJ. Reorganization of remote cortical regions after ischemic brain injury: a potential substrate for stroke recovery. Journal of neurophysiology. 2003;89:3205–3214. doi: 10.1152/jn.01143.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Clarkson AN, Clarkson J, Jackson DM, Sammut IA. Mitochondrial involvement in transhemispheric diaschisis following hypoxia-ischemia: Clomethiazole-mediated amelioration. Neuroscience. 2007;144:547–561. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dobkin JA, Levine RL, Lagreze HL, Dulli DA, Nickles RJ, Rowe BR. Evidence for transhemispheric diaschisis in unilateral stroke. Archives of neurology. 1989;46:1333–1336. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1989.00520480077023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Baslow MH. N-acetylaspartate in the vertebrate brain: metabolism and function. Neurochem Res. 2003;28:941–953. doi: 10.1023/a:1023250721185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liang Z, Zeng J, Liu S, et al. A prospective study of secondary degeneration following subcortical infarction using diffusion tensor imaging. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 2007;78:581–586. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2006.099077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kraemer M, Schormann T, Hagemann G, Qi B, Witte OW, Seitz RJ. Delayed shrinkage of the brain after ischemic stroke: preliminary observations with voxel-guided morphometry. J Neuroimaging. 2004;14:265–272. doi: 10.1177/1051228404264950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Navarro X, Vivo M, Valero-Cabre A. Neural plasticity after peripheral nerve injury and regeneration. Prog Neurobiol. 2007;82:163–201. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schallert T, Leasure JL, Kolb B. Experience-associated structural events, subependymal cellular proliferative activity, and functional recovery after injury to the central nervous system. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2000;20:1513–1528. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200011000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bradnam LV, Stinear CM, Barber PA, Byblow WD. Contralesional Hemisphere Control of the Proximal Paretic Upper Limb following Stroke. Cerebral Cortex. 2011 doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hattingen E, Lanfermann H, Menon S, et al. Combined 1H and 31P MR spectroscopic imaging: impaired energy metabolism in severe carotid stenosis and changes upon treatment. Magma. 2009;22:43–52. doi: 10.1007/s10334-008-0148-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wieloch T, Nikolich K. Mechanisms of neural plasticity following brain injury. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2006;16:258–264. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]