Abstract

The herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) latency-associated transcript (LAT) is abundantly expressed in latently infected trigeminal ganglionic sensory neurons. Expression of the first 1.5 kb of LAT coding sequences restores wild type reactivation to a LAT null HSV-1 mutant. The anti-apoptosis functions of the first 1.5 kb of LAT coding sequences are important for wild type levels of reactivation from latency. Two small non-coding RNAs (sncRNAs) contained within the first 1.5 kb of LAT coding sequences are expressed in trigeminal ganglia of latently infected mice, they cooperate to inhibit apoptosis, and reduce the efficiency of productive infection. In this study, we demonstrated that LAT sncRNA1 cooperates with the RNA sensor, retinoic acid inducible gene I (RIG-I), to stimulate IFN-β promoter activity and NF-κB dependent transcription in human or mouse cells. LAT sncRNA2 stimulated RIG-I induction of NF-κB dependent transcription in mouse neuroblastoma cells (Neuro-2A) but not human 293 cells. Since it is well established that NF-κB interferes with apoptosis, we tested whether the sncRNAs cooperated with RIG-I to inhibit apoptosis. In Neuro-2A cells, both sncRNAs cooperated with RIG-I to inhibit cold-shock induced apoptosis. Double stranded RNA (PolyI:C) stimulates RIG-I dependent signaling; but enhanced cold-shock induced apoptosis. PolyI:C, but not LAT sncRNAs, interfered with protein synthesis when cotransfected with RIG-I, which correlated with increased levels of cold-shock induced apoptosis. LAT sncRNA1 appeared to interact with RIG-I in transiently transfected cells suggesting this interaction stimulates RIG-I.

Keywords: Latency associated transcript (LAT), HSV-1, RIG-I, Cell survival, Apoptosis

1. Introduction

Acute herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) infection is initiated in mucocutaneous epithelium [reviewed in (Jones, 1998, 2003)]. High levels of lytic cycle viral gene expression and infectious virus occur during acute infection. Despite a vigorous immune response during acute infection, HSV-1 efficiently establishes lifelong latency in sensory neurons. In contrast to productive infection, abundant lytic cycle viral gene expression and shedding of infectious virus does not occur in latently infected neurons. Latent HSV-1 periodically reactivates from latency resulting in virus transmission and occasionally recurrent disease.

Mice, rabbits, or humans latently infected with HSV-1 express abundant levels of the latency-associated transcript (LAT) in latently infected sensory neurons (Croen et al., 1987; Deatly et al., 1987, 1988; Krause et al., 1988; Mitchell et al., 1990; Rock et al., 1987; Stevens et al., 1987; Wagner et al., 1988a, 1988b). The primary LAT transcript is 8.3 kb and splicing yields a stable 2 kb LAT and unstable 6.3 kb LAT (Deatly et al., 1988; Rock et al., 1987; Zwaagstra et al., 1990). The 2 kb LAT can be further spliced in infected neurons (Mador et al., 1995). The 2 kb LAT is not capped or poly-adenylated because it is a stable intron (Farrell et al., 1991; Krummenacher and Zabolotny, 1997). The LAT locus also encodes numerous micro-RNAs (miRNA) (Cui et al., 2006; Jurak et al., 2010; Umbach et al., 2008, 2009). Two small non-coding RNAs, 62 nt and 36 nt long, are expressed from the first 1.5 kb of LAT coding sequences (LAT sncRNA1 and sncRNA2) (Peng et al., 2008). LAT sncRNA1 and sncRNA2 are not miRNAs because the mature miRNA band that migrates between 21 and 23 nucleotides is not detected, they lack certain structural features of miRNAs, and both sncRNAs have the potential to form complex secondary structures. It is unlikely that LAT sncRNA1 and sncRNA2 were detected using procedures described for the HSV-1 encoded LAT miRNAs (Jurak et al., 2010; Umbach et al., 2008) because RNA species migrating between 17 and 30 nucleotides were size selected and then deep-sequencing performed.

In general, HSV-1 LAT null mutants do not reactivate from latency as efficiently as LAT expressing strains [reviewed by (Jones, 1998, 2003; Wagner and Bloom, 1997)]. Expression of the first 1.5 kb of LAT coding sequences (LAT nucleotides 1–1499) restores wild type levels of reactivation to a LAT null mutant (Inman et al., 2001; Jin et al., 2003; Perng et al., 1996a, 1996b). LAT reduces apoptosis in infected tissue culture cells (Jin et al., 2004), and promotes neuronal survival in TG of infected rabbits (Perng et al., 2000) and mice (Ahmed et al., 2002; Branco and Fraser, 2005). Plasmids expressing LAT interfere with caspase 8- and caspase 9-induced apoptosis (Ahmed et al., 2002; Henderson et al., 2002; Inman et al., 2001; Jin et al., 2003; Peng et al., 2003; Perng et al., 2000). Inhibiting apoptosis is a crucial function of LAT because three anti-apoptosis genes (Jin et al., 2005, 2008; Mott et al., 2003; Perng et al., 2002) restore the wild type reactivation phenotype to a LAT null mutant. In transient transfection studies, the LAT sncRNAs inhibit cold-shock induced apoptosis in mouse neuroblastoma cells and productive infection (Shen et al., 2009). LAT also interferes with expression of infected cell protein 4 (ICP4) (Chen et al., 1997; Garber et al., 1997) and ICP0 (Chen et al., 1997; Garber et al., 1997; Mador et al., 1998).

The retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I) is a cytosolic RNA sensor, which when activated, stimulates production of type I IFNs (IFN-α/β) and inflammatory cytokines (Yoneyama et al., 2004). RIG-I contains a N-terminal caspase recruitment domain (CARD) and a C-terminal DExD/H-box RNA helicase domain (Yoneyama et al., 2004). The helicase domain recognizes viral dsRNA, and the CARD domain activates downstream signaling through the mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein (MAVS) (Yoneyama and Fujita, 2009). The C-terminal regulatory domain of RIG-I interacts with the N-terminal CARD domain, preventing its association with MAVS. RNA binding to the C-terminal helicase induces conformational changes and exposes the CARD domain, which promotes an interaction with MAVS. The interaction between RIG-I and MAVS activates two transcription factors, nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) and IFN regulatory factor 3 (IRF3). NF-κB and IRF3 induce transcription of type I IFN and other innate immune modulatory genes (Yoneyama et al., 2004). In vitro, RIG-I recognizes RNAs containing a 5′-triphosphate moiety and partially double-stranded regions (Hornung et al., 2006; Kato et al., 2008; Pichlmair et al., 2006; Schlee et al., 2009b; Takahasi et al., 2008). In the context of a viral infection, RIG-I preferentially associates with shorter viral RNAs that contain 5′-triphosphates and/or regions that resemble double stranded RNA (dsRNA) (Baum et al., 2010). RIG-I stimulates innate immune responses independent of toll-like receptor 3 (Alexopoulou et al., 2001).

In this study, we demonstrated that LAT sncRNA1 cooperates with RIG-I to consistently stimulate IFN-β promoter activity and NF-κB dependent transcription. LAT sncRNA2 stimulated NF-κB dependent transcription as efficiently as LAT sncRNA1 in mouse neuroblastoma (Neuro-2A) cells, but not in human 293 cells. LAT sncRNA1 and sncRNA2, but not PolyI:C, cooperated with RIG-I to interfere with cold shock induced apoptosis in Neuro-2A cells. PolyI:C, but not the LAT sncRNAs, interfered with protein synthesis in transfected Neuro-2A cells, which correlated with the ability of PolyI:C to enhance cold-shock induced apoptosis.

2. Results

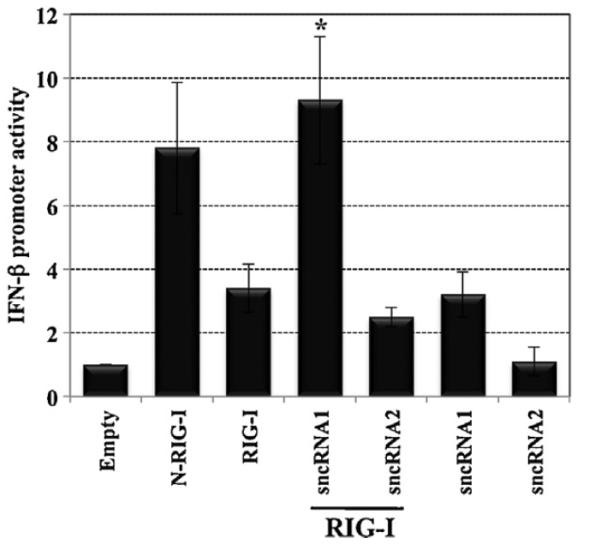

2.1. LAT sncRNA1 stimulate IFN-β promoter activity in the presence of RIG-I

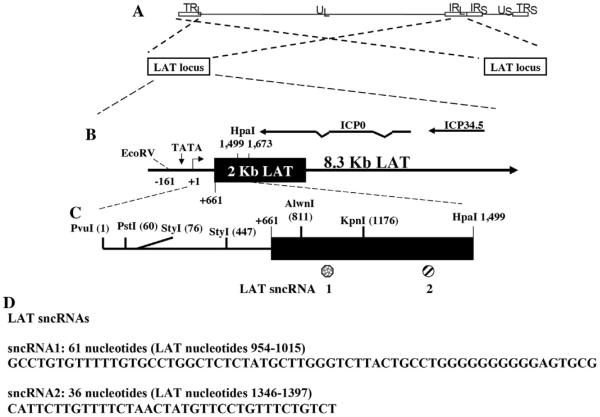

The first 1.5 kb of LAT coding sequences encode two small non-coding RNAs (sncRNAs) that are expressed in trigeminal ganglia of latently infected mice (Peng et al., 2008; Shen et al., 2009) (Fig. 1C and D). We predicted that the sncRNAs might interact with and regulate the RNA sensor (RIG-I) because they have the potential to be folded into dsRNA (Peng et al., 2008; Shen et al., 2009) and they are relatively short RNAs. To test this prediction, human cells (293) were cotransfected with a plasmid that expresses a LAT sncRNA, a reporter construct that is driven by the human IFN-β promoter, and RIG-I. The plasmid expressing sncRNA1, but not sncRNA2, cooperated with RIG-I to increase IFN-β promoter activity approximately 10-fold (Fig. 2). The induction of IFN-β promoter activity by LAT sncRNA1 and RIG-I was significantly different than RIG-I or RIG-I cotransfected with LAT sncRNA2 (P < 0.05). In the absence of RIG-I, sncRNA1 consistently stimulated IFN-β promoter activity approximately 3-fold. LAT sncRNA2 did not stimulate IFN-β promoter activity any better than the empty vector. The constitutively active RIG-I construct, N-RIG-I, stimulated higher levels of IFN-β promoter activity in transfected cells compared to the wt RIG-I construct. As expected, RIG-I efficiently stimulated IFN-β promoter activity when cotransfected with double stranded RNA (PolyI:C) in 293 cells (data not shown) and primary bovine testicle cells (da Silva and Jones, 2012b).

Fig. 1.

Schematic of HSV-1 and organization of the LAT locus. Panel A: The prototypic HSV-1 genomic structure is shown at the top. The viral repeat regions are shown as open rectangles. TRL is the terminal long repeat. IRL is the internal (or inverted) long repeat. TRS is the terminal short repeat. IRS is the internal (or inverted) short repeat. The unique long (UL) and the unique short (US) regions are each represented by a solid line, and the position of the LAT locus within the repeats is denoted. Panel B: The LAT region (one in each long repeat) is shown in expanded form. The primary 8.3 kb LAT is denoted as a long arrow. The stable 2 kb LAT is shown as a solid rectangle. The LAT TATA box is denoted by TATA, and the small arrow and +1 indicate the start of LAT transcription (genomic nucleotide 118801). The relative locations of mRNAs encoding ICP0 and ICP34.5 are shown for reference. Panel C: The position of certain restriction enzyme sites within the first 1.5 kb of LAT coding sequences and relative locations of the two LAT sncRNAs previously identified (Peng et al., 2008). Panel D: The nucleotide sequence and positions of LAT sncRNA1 and LAT sncRNA2 are presented.

Fig. 2.

LAT sncRNA1 induces IFN-β promoter activity when cotransfected with RIG-I. Human 293 cells (2 × 106) were transfected with a CAT reporter plasmid containing the human IFN-β promoter (1 μg), RIG-I (1 μg), and 2 μg of a plasmid expressing the LAT sncRNA1 or sncRNA2. N-RIG-I (1 μg) served as a positive control. Equivalent amounts of DNA were used for transfection by adding an empty expression vector (pSilencer 2.1-U6 neo). 2 days after transfection, cells were harvested and CAT activity measured. The results are shown as fold increase relative to cells transfected with the IFN-β CAT reporter plasmid plus the empty pSilencer plasmid (Empty), which was arbitrarily set as 1. The values are the average of three independent experiments. An asterisk denotes significant differences (P < 0.05) in cells transfected with the human IFN-β CAT reporter plasmid plus LAT sncRNA1 and the RIG-I expression plasmid relative to IFN-β promoter activity in cells transfected with LAT sncRNA2 plus RIG-I or RIG-I plus empty vector, as determined by the Student t-test.

2.2. LAT sncRNA1 cooperates with RIG-I to consistently stimulate NF-βB dependent transcription

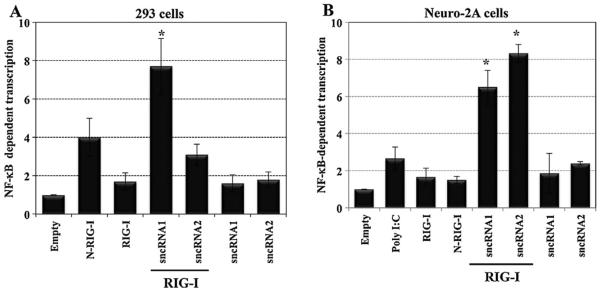

The cellular transcription factor NF-κB is also activated by RIG-I, and NF-κB is important for stimulating IFN-β promoter activity, reviewed in (Yoneyama and Fujita, 2009). Consequently, studies were performed to test whether LAT sncRNAs had an effect on NF-κB dependent transcription in the presence of RIG-I. A luciferase reporter gene containing a simple promoter and 5 consensus NF-κB binding sites (p5X-NF-κB) was used to measure NF-κB dependent transcription. LAT sncRNA1 stimulated NF-κB dependent transcription approximately 8-fold in 293 cells when cotransfected with RIG-I (Fig. 3A). LAT sncRNA2 stimulated NF-κB dependent transcription approximately 3-fold when cotransfected with RIG-I, which was significantly less (P < 0.05) than the effect seen with sncRNA1 or just RIG-I cotransfected with empty vector. In the absence of RIG-I, LAT sncRNA1 stimulated NF-κB dependent transcription less than twofold. As expected, the constitutively activated RIG-I deletion construct (N-RIG-I), but not wt RIG-I, stimulated NF-κB dependent transcription approximately fourfold in 293 cells.

Fig. 3.

LAT sncRNA1 stimulate NF-κB dependent transcription when cotransfected with RIG-I. Approximately 6 × 105 293 cells (Panel A) or Neuro-2A cells (Panel B) were transfected with the 5× NF-κB luciferase reporter construct (1 μg), pRL-TK (0.033 μg), RIG-I (1 μg) and 2 μg of the indicated LAT sncRNAs. N-RIG-I (1 μg) and Poly I:C (0.5 μg) served as positive controls. Cells were harvested at 24 h after transfection and the Dual-Luciferase assay performed. The data represents the firefly luciferase activity normalized relative to Renilla luciferase activity. The values are expressed as fold difference relative to cells transfected with the luciferase reporter vectors plus an empty vector (Empty), which was arbitrarily set as 1. The values are the average of three independent experiments. An asterisk denotes significant differences (P < 0.05) in cells transfected with the human IFN-β CAT reporter plasmid plus LAT sncRNA1 and the RIG-I expression plasmid relative to IFN-β promoter activity in cells transfected with RIG-I plus empty vector, as determined by the Student t-test.

As a comparison to the results obtained in 293 cells, the studies were repeated in mouse neuroblastoma cells (Neuro-2A). LAT sncRNA1 and sncRNA2 stimulated NF-κB dependent transcription at least 6-fold when cotransfected with RIG-I (Fig. 3B), which was significantly different compared to RIG-I cotransfected with empty vector (P < 0.5). In contrast to 293 cells, LAT sncRNA2 consistently activated NF-κB dependent transcription at slightly higher levels relative to LAT sncRNA1; but the difference was not significantly different (P > 0.05). In the absence of RIG-I, their effect was nominal indicating that the ability of LAT sncRNAs to stimulate NF-κB dependent transcription was dependent on abundant levels of RIG-I. As expected, PolyI:C induced NF-κB dependent transcription but the effect was less than the LAT sncRNAs. In contrast to 293 cells, the N-RIG-I construct was unable to stimulate NF-κB dependent transcription in Neuro-2A cells. These studies indicated that LAT sncRNA1 induced NF-κB dependent transcription when cotransfected with RIG-I in 293 and Neuro-2A cells. LAT sncRNA2 stimulated NF-κB dependent transcription in Neuro-2A cells, but not in 293 cells.

2.3. LAT sncRNAs stimulate cell survival following cold shock induced apoptosis

Additional studies were performed to test whether RIG-I stimulates the anti-apoptosis functions of LAT sncRNAs. The rationale for this study is NF-κB promotes cell survival (Foehr et al., 2000; Goodkin et al., 2003; Mattson and Meffert, 2006), LAT sncRNA1 interferes with apoptosis in transiently transfected Neuro-2A cells (Shen et al., 2009), and LAT sncRNA1 cooperated with RIG-I to stimulate NF-kB dependent transcription in 293 and Neuro-2A cells. Furthermore, LAT sncRNA2 enhances the anti-apoptosis properties of sncRNA1 (Shen et al., 2009).

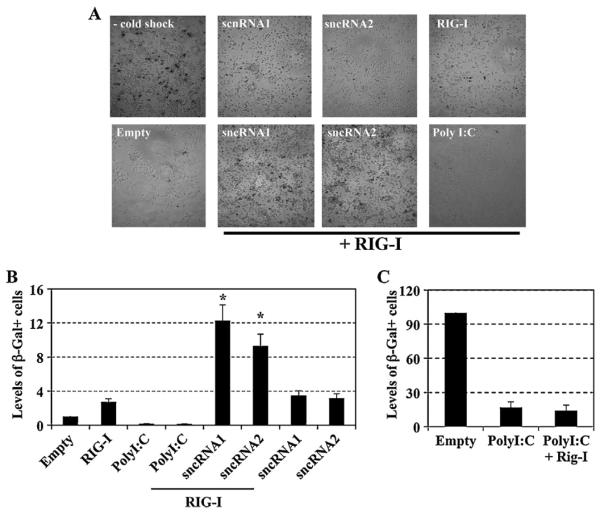

Neuro-2A cells were chosen for these studies because unlike 293 cells they are sensitive to cold shock induced apoptosis (Shen et al., 2009; Shen and Jones, 2008). Furthermore, cold shock may have relevance to the HSV-1 latency-reactivation cycle because cold stress can induce recurrent herpetic keratitis in squirrel monkies (Varnell et al., 1995). Plasmids expressing the respective LAT sncRNAs, RIG-I, and a CMV β-Gal expression plasmid were transfected into Neuro-2A cells and cold-shock induced apoptosis performed as previously described (Carpenter et al., 2007; Shen et al., 2009; Shen and Jones, 2008). The β-Gal co-transfection assay accurately measures the effects of various genes on apoptosis (Ciacci-Zanella et al., 1999; Henderson et al., 2002; Inman et al., 2001; Jin et al., 2003; Perng et al., 2000) because a known apoptosis stimulator reduces the number of β-Gal+ cells. Comparing changes in the number of β-Gal+ Neuro-2A cells after cold shock induced apoptosis among cultures treated with anti-apoptosis genes versus those treated with negative controls are identical to differences in DNA laddering, the number of sub-G1 levels of DNA, and trypan blue exclusion (Shen et al., 2009). At 36 h after transfection, cells were starved in 2% fetal calf serum for 12 h, cultures were incubated on ice for 1 h, and cultures were then returned to 37 °C for 3.5 h. Neuro-2A cells (Fig. 4A) or Neuro-2A cells placed on ice for 1 h contain little to no detectable DNA laddering or cell death as judged by a decrease in the number of β-Gal+ cells (Shen et al., 2009; Shen and Jones, 2008). However, extensive DNA laddering, indicative of apoptosis, occurs when Neuro-2A cells are returned to 37 °C for 3 or 6 h (Shen et al., 2009; Shen and Jones, 2008).

Fig. 4.

LAT sncRNAs interfere with cold-shock induced apoptosis. Panel A: Neuro-2A cells were cotransfected with plasmids encoding the β-Galactosidase (β-Gal) gene (0.025 μg), RIG-I (1 μg), the sncRNA1 or sncRNA2 (2 μg), or Poly I:C (0.5 μg), as indicated. At 48 h after transfection, Neuro-2A cells were submitted to cold-shock induced apoptosis and subsequently recovered for 3.5 h at 37°C. As a control, Neuro-2A cells that were transfected with the β-Gal expression vector and pSilencer 2.1-U6 neo; but not subjected to cold-shocked induced apoptosis were included. Cells were then fixed, stained for β-Gal expression, and representative pictures of the respective cultures shown. Panel B: The number of β-Gal positive cells (blue cells) was counted and the relative cell survival after cold-shock induced cell death was expressed as fold of induction relative to cells transfected with an empty vector plus the β-Gal plasmid, which is arbitrarily set as 1. The results are the average of three independent experiments. An asterisk denotes significant differences (P < 0.05) in cell survival following transfection with the RIG-I expression plasmid and LAT sncRNAs relative to cells transfected with RIG-I plus empty vector, as determined by the Student t-test. Panel C: The number of surviving blue Neuro-2A cells in mock transfected cells was compared to cells treated with PolyI:C or PolyI:C plus over-expression of Rig-I.

When LAT sncRNA1 or sncRNA2 were cotransfected with the RIG-I expression plasmid, the number of β-Gal+ Neuro-2A cells was significantly increased (P < 0.05) after cold shocking cultures and then returning them to 37 °C for 3.5 h relative to cells transfected with an empty expression vector and RIG-I (Fig. 4A and B). PolyI:C, in contrast to the LAT sncRNAs, reduced the number of β-Gal+ Neuro-2A cells when cotransfected with RIG-I. No significant differences were observed when comparing the number of β-Gal+ Neuro-2A cells treated with PolyI:C relative to cells treated with PolyI:C and transfected with RIG-I (Fig. 4B and C). In the absence of the RIG-I expression plasmid, LAT sncRNA1 and LAT sncRNA2 increased the number of β-Gal+ cells approximately 3-fold. A previous study (Shen et al., 2009) found that LAT sncRNA2 had little effect on inhibiting apoptosis; whereas this study demonstrated that it inhibited cold shock apoptosis. Although Neuro-2A cells are immortalized, they exhibit different growth properties as they are passaged, which affects their sensitivity to cold shock induced apoptosis suggesting this influenced the results we obtained with LAT sncRNA2. In summary, these studies demonstrated that LAT sncRNA1 and sncRNA2 cooperated with RIG-I to inhibit cold shock induced apoptosis in Neuro-2A.

2.4. LAT sncRNAs stimulate RIG-I activity but do not interfere with expression of Flag-tagged proteins

The finding that LAT sncRNAs promoted cell survival when transfected with RIG-I but PolyI:C enhanced apoptosis when transfected with RIG-I suggested that the mechanism by which PolyI:C stimulated RIG-I dependent signaling pathways was different than the LAT sncRNAs. In general, dsRNA (PolyI:C for example) induces the IFN-β signaling pathway and protein synthesis is inhibited, reviewed in (Clemens and Elia, 1997; Katze et al., 2002; Yoneyama and Fujita, 2009). It is also well established that inhibiting protein synthesis enhances apoptosis (Coxon et al., 1998; Marissen and Patel, 1998; Martin et al., 1990) suggesting that PolyI:C, but not the LAT sncRNAs, interfered with protein synthesis in Neuro-2A cells and enhanced cold-shock induced apoptosis.

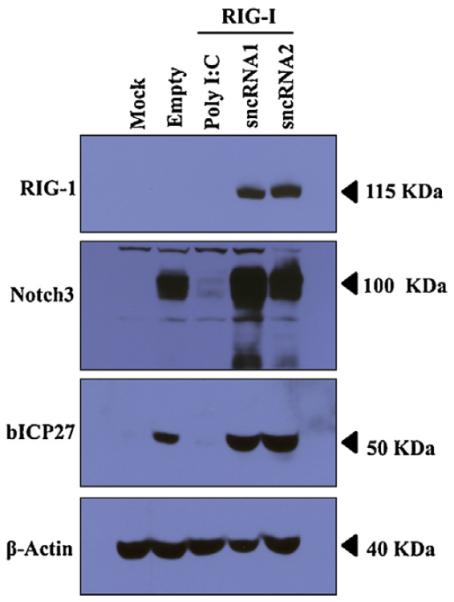

Studies were consequently conducted to test whether LAT sncRNAs interfered with protein synthesis when cotransfected with RIG-I. Since not all Neuro-2A cells are transfected with a plasmid that expresses a LAT sncRNA, we were concerned it would not be possible to compare total protein synthesis in the respective samples cells. Consequently, we included in the transfection mixture a plasmid that expresses a Flag tagged protein, which allowed us to examine the effect that PolyIC or the LAT sncRNAs has on steady state levels of the respective Flag-tagged proteins. In the presence of PolyI:C and RIG-I, protein levels of the Notch3 intercellular domain (Notch3) or the BHV-1 ICP27 protein were reduced compared to cells transfected with just an empty vector (Fig. 5). Neuro-2A cells cotransfected with plasmids expressing LAT sncRNA1 or LAT-sncRNA2 and RIG-I expressed similar levels of Notch3 or bICP27 when compared to cells transfected with an empty expression vector and plasmids expressing Notch3 or bICP27. In summary, this study suggested that PolyI:C, but not the LAT sncRNAs, reduced Notch3 or bICP27 steady state protein levels in transfected Neuro-2A cells.

Fig. 5.

In contrast to PolyI:C, LAT sncRNAs do not interfere with protein synthesis. Western blot analysis comparing the levels of two proteins (Notch3 and bICP27) in the presence of Poly I:C or RIG-I cotransfected with plasmids expressing a LAT sncRNA expression plasmid. Neuro-2A cells were cotransfected with plasmids encoding Notch3 (1 μg) or bICP27 (1 μg), Poly I:C (0.5 μg), RIG-I (1 μg) and 2 μg of the LAT sncRNAs (1 or 2). After 36 h, whole cell lysate was prepared. A total of 100 μg of protein was separated in an 8% SDS-PAGE gel, end expression of Notch3 or Flag-tagged bICP27 detected by Western blot analysis using a rabbit anti-Notch3 polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz) or a anti-Flag monoclonal antibody (Sigma) to detect Flag tagged bICP27, respectively. β-actin protein levels were analyzed in the respective samples as a loading control.

2.5. LAT sncRNA1 is associated with RIG-I

Although the results presented above suggested that LAT sncRNA1 consistently stimulated RIG-I dependent signaling in 293 and Neuro-2A cells, they do not allow us to conclude whether this effect was direct or indirect. When RIG-I interacts with short dsRNA, the RIG-I signaling pathway is activated (Kato et al., 2008; Schlee et al., 2009b; Schmidt et al., 2009; Yoneyama et al., 2004). If LAT sncRNA1 directly activates the RIG-I signaling pathway, one would predict that LAT sncRNA1 would be stably associated with the RIG-I protein. Conversely, if LAT sncRNA1 indirectly activated the RIG-I signaling pathway, it would not be expected to stably associate with RIG-I.

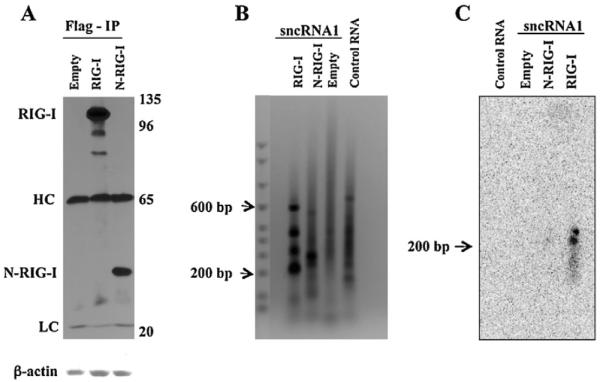

To test whether LAT sncRNA1 was associated with RIG-I, 293 cells were cotransfected with RIG-I, N-RIG-I or an empty vector plus a plasmid expressing LAT sncRNA1. As previously reported (da Silva and Jones, 2012b), immunoprecipitation of RIG-I or N-RIG-I with a FLAG monoclonal antibody efficiently precipitated the RIG-I or N-RIG-I protein (Fig. 6A). As expected, the IgG heavy chain (HC) and light chains (LC) were also readily detected. N-RIG-I lacks the RNA binding domain of RIG-I and thus LAT sncRNA1 would not be expected to associate with N-RIG-I. 48 h after transfection, 293 cells were lysed and RIG-I/RNA or N-RIG-I/RNA complexes were immunoprecipitated (IP) with a FLAG-antibody (Fig. 6A). Following IP, RNA associated with RIG-I or N-RIG-I was recovered by acid phenol extraction and converted into cDNA by performing RT-PCR using adapter specific primers. The resulting cDNA was subsequently used as a template for PCR with primers specific for the LAT sncRNA1 as described in the material and methods. In several independent studies, we found that this procedure led to multiple bands in all of the lanes (Fig. 6B) suggesting that non-specific amplification of RNAs associated with RIG-I occurred. To test for specific amplification of LAT sncRNA1, a Southern blot was performed using a 32P-labeled DNA fragment containing the full-length LAT sncRNA1 as a probe (Fig. 6C). The probe recognized a band of approximately 200 bp that was amplified from cDNA originating from the RIG-I/RNA complex from cells cotransfected with RIG-I and LAT sncRNA1 (Fig. 6C). In contrast, the 32P-labeled LAT sncRNA1 probe did not recognize a specific band in the RIG-I IP from cells transfected with N-RIG-I or the empty vector. Although this fragment appears to be larger than expected, there appears to be more than one adapter that was added to LAT sncRNA1 during the ligation process. Furthermore, LAT sncRNA1, perhaps due to its potential secondary structure, migrates larger than expected. Similar studies were unable to detect a stable association between LAT sncRNA2 and RIG-I in 293 cells (data not shown).

Fig. 6.

LAT sncRNA1 interacts with full length RIG-I. Panel A: Monolayers containing 4 × 106 293 cells were transfected with 5 μg of an empty Flag-vector (Empty) or Flag-vectors expressing RIG-I or N-RIG-I along with 5 μg of plasmids expressing the LAT sncRNA1. 48 h after transfection cells were harvested in hypotonic buffer and then a RIG-I IP performed using an anti-Flag monoclonal antibody. The efficiency of the IP was monitored by western blot (WB) analysis using the anti-Flag monoclonal antibody. The position of the RIG-I protein, N-RIG-I protein, heavy chain of IgG (HC), and light chain of IgG (LC) are denoted. The position of molecular weight markers (kD) is shown on the right side of the western blot. Panel B: The RNA associated with RIG-I was extracted by acid–phenol:chloroform extraction and subsequently converted into cDNA using a MicroRNA Amplification kit as described in material and methods. The resultant cDNA served as a template for PCR-amplification by the forward primers specific for the LAT sncRNA1 and the reverse primer specific for the 3′-adaptor. The resultant PCR products were electrophoresed on a 1.2% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide. Panel C: Southern blot analysis was performed using as a probe a 32P-labeled DNA fragment digested from a plasmid containing the sequences encoding LAT sncRNA1. The arrow denotes the position of the LAT sncRNA1-specific band recognized by the probe. These results are representative of 2 independent experiments.

3. Discussion

These studies suggested that expression of LAT sncRNA1 and sncRNA2 play a role in the latency-reactivation cycle because they regulate RIG-I dependent signaling pathways, which consequently enhances cell survival. Both sncRNAs are located within the first 1.5 kb of LAT coding sequences. It is well established that the first 1.5 kb of LAT coding sequences restore the high wt reactivation phenotype to a LAT null mutant in small animal models (Perng et al., 1994, 1996a, 2001). Additional genetic studies support a role for expression of the LAT sncRNAs in the latency-reactivation cycle. For example, a recombinant virus that expresses just the first 811 bases of LAT coding sequences, and thus lacks the coding sequences for LAT sncRNA1 and sncRNA2, has reduced reactivation from latency (Drolet et al., 1999; Inman et al., 2001). Recombinant viruses containing more extensive LAT deletions reactivate from latency like a LAT null mutant (Drolet et al., 1999; Inman et al., 2001).

RIG-I recognizes RNA of various lengths and appears to prefer dsRNA with or without 5′-triphosphates (Baum et al., 2010; Hornung et al., 2006; Pichlmair et al., 2006; Schlee et al., 2009a, 2009b; Schmidt et al., 2009; Yoneyama and Fujita, 2009). RIG-I has structural similarity to DICER, an RNAse III-type nuclease, that mediates RNA interference (Zou et al., 2009). Dicer requires dsRNA binding protein partners, PACT for example, for maximal activity (Kok et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2006). RIG-I also directly binds to PACT, and this interaction facilitates innate antiviral responses (Kok et al., 2011). Due to the complexity by which RIG-I recognizes its substrates, it is not clear how LAT sncRNA1 stimulated RIG-I dependent signaling or why LAT sncRNA2 cooperated with RIG-I to stimulate NF-κB dependent transcription in neuro-2A cells but not in 293 cells. It seems reasonable to predict that cell type specific proteins, in part, regulate the RNA sensing functions of RIG-I and how RIG-I signals after being activated. Certain BHV-1 sequences derived from the latency related gene expressed from the pSilencer 2.1-U6 neo do not cooperate with RIG-I and stimulate IFN-β promoter activity (da Silva and Jones, 2012b) indicating that over-expression of any GC-rich sncRNA is not sufficient for this activity. For example, PolyI:C, but not LAT sncRNA1 or sncRNA2, reduced expression of proteins encoded by a plasmid when cotransfected with PolyI:C. Furthermore, LAT sncRNA1 and sncRNA2 promoted cell survival in Neuro-2A cells whereas PolyI:C enhanced cold-shock induced apoptosis.

Type I IFN (IFN-α and IFN-β) induction can induce apoptosis (Chawla-Sarkar et al., 2003; Leaman et al., 2002; Takaaoka et al., 2003) or promote cell survival (Yang et al., 2000). Type I IFN promotes cell survival, in part by activating NF-κB (Yang et al., 2005) and the threonine/serine protein kinase Akt (Yang et al., 2001). Further evidence that NF-κB promotes cell survival comes from studies demonstrating that NF-κB stimulates expression of c-FLIP (Benayoun et al., 2008), Bcl-2 family members (Bcl-X and Bfl-1/A1) (Lee et al., 1999), and the inhibitor of apoptosis (IAP) family members (Salvesen and Duckett, 2002). Interestingly, NF-κB can also promote cell survival and neurite process formation in nerve growth factor-stimulated rat pheochromocytoma cells, PC12 (Foehr et al., 2000). Recent studies provide evidence that RIG-I protects neurons from axonal damage and decreases inflammation in the central nervous system (Dann et al., 2012) suggesting the LAT sncRNAs promote the repair of damaged neurons after infection. LAT, directly or indirectly, stimulates Akt activity in mouse neruoblastoma cells (Li et al., 2010) providing evidence that the LAT sncRNAs inhibited cold shock induced apoptosis by stimulating NF-κB dependent transcription and perhaps Akt signaling.

In the context of the latency-reactivation cycle, we predict that the ability of the LAT sncRNAs to stimulate RIG-I dependent signaling is important during the establishment and maintenance of latency because it impairs HSV-1 replication and gene expression in sensory neurons. For example, the ability of LAT sncRNA1 to reduce HSV-1 replication efficiency (Shen et al., 2009) may be due to its ability to consistently stimulate IFN-β promoter activity in the presence of RIG-I. RIG-I is an IFN inducible gene (Cui et al., 2004; Kawaguchi et al., 2009), and consequently amplification of IFN signaling would dampen viral gene expression and enhance neuronal survival. During the maintenance of latency, low levels of viral gene expression periodically occur in a subset of latently infected neurons, which is defined as spontaneous molecular reactivation (Feldman et al., 2002). During spontaneous reactivation, IFN-β signaling and increased RIG-I protein levels may occur as a result of lytic cycle viral gene expression. Although RIG-I is IFN inducible, RIG-I protein expression is detected in many un-stimulated cell types (Kawaguchi et al., 2009) suggesting LAT encoded sncRNAs interact with RIG-I in the absence of viral gene activity and consequently enhances neuronal survival. Support for this prediction comes from the finding that LAT sncRNA1 stimulated IFN-β promoter activity even when RIGI was not over-expressed. In summary, our studies suggest that interactions between RIG-I and LAT sncRNAs promote latency and neuronal survival by “sensing” viral activity during acute infection or spontaneous reactivation. To directly examine the role that LR sncRNAs play in the latency-reactivation cycle, it will be necessary to determine whether expression of the LAT sncRNAs influence the latency-reactivation cycle of HSV-1 in small animal models of infection.

4. Methods

4.1. Cells and transfection of these cells

Mouse neuroblastoma cells (Neuro-2A) and human embryonic kidney cells (293) were cultured in Earle's modified Eagle's (EMEM) medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, penicillin (10 U/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml) in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37 °C.

Neuro-2A cells were transfected with the designated plasmids using TransIT Neural (MIR2145; Mirus) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Human 293 were transfected with the designated plasmids using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

4.2. Plasmids

The human IFN-β chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) plasmid was obtained from Stavros Lomvards (Columbia University, NY) and contains sequences (positions −110 to −20) necessary for IFN-β activation. The LAT-encoded sncRNA1 and sncRNA2 constructs were cloned into pSilencer 2.1-U6 neo (Ambion) (Shen et al., 2009). The FLAG tagged RIG-I constructs; including the full length RIG-I (pFE-BOS RIG-I) and the constitutively active C-terminal deletion mutant RIG-I (pEF-BOS N-RIG-I) (Sumpter et al., 2005) were obtained from M. Gale (University of Washington), and are referred to as RIG-I and N-RIG-I, respectively. The p5X-NF-κB-luciferase reporter construct (Alexopoulou et al., 2001) was obtained from R. Flavell (Yale University School of Medicine), and the Renilla luciferase (pRL-TK) reporter construct was purchased from Promega. Plasmids expressing a Flag-tagged infected cell protein 27 (bICP27) encoded by BHV-1 and the notch intercellular domain 3 (Notch3) were previously described (da Silva and Jones, 2012a; Workman et al., 2011).

4.3. Measurement of reporter gene expression

Chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) reporter assays were performed as previously described (da Silva and Jones, 2011, 2012b; Workman et al., 2012; Workman and Jones, 2010). Approximately 40 h after transfection, 293 cells were lysed by three freeze-thaw cycles in 250 mM Tris-HCl (pH7.4). CAT assays were performed with 0.2 μCi (7.4 KBq) 14C-chloramphenicol (Amersham Biosciences, CFA754) and 0.5 mM acetyl coenzyme A (Sigma, A2181). Chloramphenicol and its acetylated forms were separated by thin-layer chromatography and CAT activity measured with a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics, CA). Transfection experiments for CAT assays were repeated at least three times to confirm the results.

The NF-κB luciferase reporter assays were performed in Neuro-2A and 293 cells as previously described (da Silva and Jones, 2012b). In brief, Neuro-2A and 293 cells seeded in 60 mm dishes containing EMEM plus 5% FCS at approximately 24 h before transfection. 2 h before transfection, EMEM with 5% FCS was replaced with fresh EMEM containing 0.5% FCS, which kept basal levels of NF-κB promoter activity consistently low. Cells were then transfected with a plasmid containing the firefly-luciferase gene that is regulated by a simple promoter with 5 consensus NF-κB binding sites (p5X-NF-κB-luciferase), a plasmid encoding Renilla-luciferase under control of the herpesvirus TK promoter (pRL-TK) plus the indicated plasmids. 24 h after transfection, cells were harvested and subjected to the dual luciferase-assay by using a commercially available kit (Promega, E1910), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

4.4. Cell survival studies

Cold shock induced apoptosis was performed as previously described (Shen and Jones, 2008; Shen et al., 2009). In brief, approximately 3 μ 105 Neuro-2A cells were plated in six well culture plates containing EMEM with 10% FCS 24 h prior to transfection. Cells were cotransfected with a plasmid encoding the β-Galactosidase (β-Gal) gene (0.025 μg), the RIG-I expression plasmid (1 μg), and 2 μg of pSilencer encoding a LAT sncRNA1 or sncRNA2. To maintain equal amounts of DNA for transfection, the empty pSilencer plasmid was used. After transfection for 24 h, cells were seeded in 24 well plates containing EMEM with 10% FCS and incubated for 12 h, and then EMEM with 2% FCS was added to the cultures. After 12 h in EMEM with 2% FCS, Neuro-2A cells were placed on ice for 1 h with the culture plates sealed with Parafilm. After 1 h on ice, the Parafilm was removed and plates were incubated at 37 °C for 3.5 h. Cells were then fixed and stained for β-Gal expression. To calculate the relative level of cell survival after cold-shock induced cell death, the number of β-Gal positive cells were counted as previously described (Ciacci-Zanella et al., 1999; Ciacci-Zanella and Jones, 1999; Henderson et al., 2002; Perng et al., 2000, 2002). The number of blue cells in cultures transfected with the empty vector plus β-Gal was set as 1. The number of blue cells in cultures transfected with RIG-I along with empty vector or the LAT sncRNAs constructs was divided by the number of blue cells in cultures transfected with the empty vector plus β-Gal. The results are the average of at least three independent experiments.

4.5. Western blots

Western blot analysis was performed as previously described (da Silva and Jones, 2011; da Silva et al., 2011; da Silva and Jones, 2012a, 2012b).

4.6. Identification of RIG-I-associated RNA in transfected 293 cells

Procedures to identify interactions between BHV-1 miRNAs encoded by the latency related gene and RIG-I were previously described (da Silva and Jones, 2012b). In brief, human 293 cells (4 × 106) were cotransfected with 5 μg of full-length RIG-I plasmid, the C-terminal deletion mutant N-RIG-I or an empty FLAG expression vector, plus 5 μg of plasmids expressing sncRNA1 or sncRNA2. 48 h after transfection cells were harvested in hypotonic buffer (10 mM Tris pH7.5, 10 mM KCl, 0.5 mM EGTA and 1.5 mM MgCl2, plus protease inhibitor) and subjected to immunoprecipitation followed by isolation of RIG-I-associated RNA, as previously described (Chiu et al., 2009; da Silva and Jones, 2011). One hundred ng of RIG-I-associated RNA was used to amplify total sncRNAs using the Global MicroRNA Amplification Kit (SBI System Biosciences, catalog # RA400A-1) according to the manufacturer's instructions. One percent of the amplified cDNA served as a template for PCR-amplification with the forward primers specific for sncRNA1 (5′-GCCTGTGTTTTTGTGCCTGGCTC-3′) or sncRNA2 (5′-CATTCTTGTTTTCTAACTATGTTCCTG-3′) and a reverse primer specific for the 3′-adaptor provided in the kit. The PCR reactions were electrophoresed in a 1.2% agarose gel. The DNA in the gel was blotted onto Hybond N+ (Amersham Biosciences), UV cross-linked, and probed at 55 °C with the full-length LAT sncRNA1 sequences. The probe was obtained by digestion of the pSilencer 2.1-U6 neo construct containing LAT sncRNA1 with BamHI and HindIII to release LAT sncRNA1 sequences. LAT sncRNA1 was labeled at its 5′-termini with 32P using polynucleotide kinase and 32P-gamma-ATP. After autoradiography, radioactive bands were visualized using a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics, CA).

Acknowledgements

A grant to the Nebraska Center for Virology (1P20RR15635) supported certain aspects of these studies. This project was also partially supported by Agriculture and Food Research Initiative competitive grant no. 09-01653 from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture.

References

- Ahmed M, Lock M, Miller CG, Fraser NW. Regions of the herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-associated transcript that protect cells from apoptosis in vitro and protect neuronal cells in vivo. Journal of Virology. 2002;76:717–729. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.2.717-729.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexopoulou L, Holt AC, Medzhitov R, Flavell RA. Recognition of double-stranded RNA and activation of NF-kappaB by toll-like receptor 3. Nature. 2001;413:732–738. doi: 10.1038/35099560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum A, Sachidanandam R, Garcia-Sastre A. Preference of RIG-I for short viral RNA molecules in infected cells revealed by next-generation sequencing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:16303–16308. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005077107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benayoun B, Baghdiguian S, Lajmanovich A, Bartoli M, Daniele N, Gicquel E, Bourg N, Raynaud F, Pasquier M-A, Suel L, Lochmuller H, Lefranc G, Richard I. NF-kB-dependent expression of the antiapoptotic factor c-FLIP is regulated by calpain 3, the protein involved in limb-girdle muscular dystrophy type 2A. FASEB Journal. 2008;22:1521–1529. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-8701com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branco FJ, Fraser NW. Herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-associated transcript expression protects trigeminal ganglion neurons from apoptosis. Journal of Virology. 2005;79:9019–9025. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.14.9019-9025.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter D, Hsiang C, Jin L, Osorio N, BenMohamed L, Jones C, Wechsler SL. Stable cell lines expressing high levels of the herpes simplex virus type 1 LAT are refractory to caspase 3 activation and DNA laddering following cold shock induced apoptosis. Virology. 2007;369:12–18. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chawla-Sarkar M, Lindner DJ, Liu Y-F, Williams BR, Sen GC, Silverman RH, Borden EC. Apoptosis and interferons: role of interferon-stimulated genes as mediators of apoptosis. Apoptosis. 2003;8:237–249. doi: 10.1023/a:1023668705040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen SH, Kramer MF, Schaffer PA, Coen DM. A viral function represses accumulation of transcripts from productive-cycle genes in mouse ganglia latently infected with herpes simplex virus. Journal of Virology. 1997;71:5878–5884. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.8.5878-5884.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu YH, Macmillan JB, Chen ZJ. RNA polymerase III detects cytosolic DNA and induces type I interferons through the RIG-I pathway. Cell. 2009;138:576–591. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciacci-Zanella J, Stone M, Henderson G, Jones C. The latency-related gene of bovine herpesvirus 1 inhibits programmed cell death. Journal of Virology. 1999;73:9734–9740. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.12.9734-9740.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciacci-Zanella JR, Jones C. Fumonisin B1, a mycotoxin contaminant of cereal grains, and inducer of apoptosis via the tumour necrosis factor pathway and caspase activation. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 1999;37:703–712. doi: 10.1016/s0278-6915(99)00034-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemens MJ, Elia A. The double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase PKR: structure and function. Journal of Interferon and Cytokine Research. 1997;17:503–524. doi: 10.1089/jir.1997.17.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coxon FP, Benford HL, Russell RGG, Rogers MJ. Protein synthesis is required for caspase activation and induction of apoptosis by bisphosphonate drugs. Molecular Pharmacology. 1998;54:631–638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croen KD, Ostrove JM, Dragovic LJ, Smialek JE, Straus SE. Latent herpes simplex virus in human trigeminal ganglia, Detection of an immediate early gene “anti-sense” transcript by in situ hybridization. New England Journal of Medicine. 1987;317:1427–1432. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198712033172302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui C, Griffiths A, Li G, Silva LM, Kramer MF, Gaasterland T, Wang X-J, Coen DC. Prediction and identification of herpes simplex virus 1-encoded microRNAs. Journal of Virology. 2006;80:5499–5508. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00200-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui X-F, Imaizumi T, Yoshida H, Borden EC, Satoh K. Retinoic acid-inducible gene-I is induced by interferon-gamma and regulates the expressionof interferon-gamma stimulated gene 15 in MCF-7 cells. Biochemistry and Cell Biology – Biochimie et Biologie Cellulaire. 2004;82:401–405. doi: 10.1139/o04-041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva LF, Jones C. Infection of cultured bovine cells with bovine herpesvirus 1 (BHV-1) or Sendai virus induces different beta interferon subtypes. Virus Research. 2011;157:54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva LF, Gaudreault N, Jones C. Cytoplasmic localized infected cell protein 0 (bICP0) encoded by bovine herpesvirus 1 inhibits beta interferon promoter activity and reduces IRF3 (interferon response factor 3) protein levels. Virus Research. 2011;169:143–149. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva LF, Jones C. The ICP27 protein encoded by bovine herpesvirus type 1 (bICP27) interferes with promoter activity of the bovine genes encoding beta interferon 1 (IFN-β1) and IFN-β3. Virus Research. 2012a:162–168. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2012.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva LF, Jones C. Two micro-RNAs encoded within the BHV-1 latency related (LR) gene promote cell survival by interacting with RIG-I and stimulating nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-kB) dependent transcription and beta-interferon signaling pathways. Journal of Virology. 2012b;86:1670–1682. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06550-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dann A, Poeck H, Croxford AL, Gaupp S, Kierdorf K, Knust M, Pfeifer D, Maihoefer C, Endres S, Kalinke U, Meuth SG, Wiendl H, Knobeloch K-P, Akira S, Waisman A, Hartmann G, Prinz M. Cytosolic RIG-I like helicases act as negative regulators of sterile inflammation in the CNS. Nature Neuroscience. 2012;15:98–106. doi: 10.1038/nn.2964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deatly AM, Spivack JG, Lavi E, O'Boyle DR, Fraser NW. Latent herpes simplex virus type 1 transcripts in peripheral and central nervous system tissues of mice map to similar regions of the viral genome. Journal of Virology. 1988;62:749–756. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.3.749-756.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deatly AM, Spivack JG, Lavi E, Fraser NW. RNA from an immediate early region of the type 1 herpes simplex virus genome is present in the trigeminal ganglia of latently infected mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1987;84:3204–3208. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.10.3204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drolet BS, Perng GC, Villosis RJ, Slanina SM, Nesburn AB, Wechsler SL. Expression of the first 811 nucleotides of the herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-associated transcript (LAT) partially restores wild-type spontaneous reactivation to a LAT-null mutant. Virology. 1999;253:96–106. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell MJ, Dobson AT, Feldman LT. Herpes simplex virus latency-associated transcript is a stable intron. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1991;88:790–794. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.3.790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman LT, Ellison AR, Voytek CC, Yang L, Krause P, Margolis TP. Spontaneous molecular reactivation of herpes simplex virus type 1 latency in mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99:978–983. doi: 10.1073/pnas.022301899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foehr ED, Lin X, O'Mahony A, Geleziunas R, Bradshaw RA, Greene WC. NF-kB signaling promotes both cell survival and neurite process formation in nerver growth factor-stimulated PC12 cells. Journal of Neuroscience. 2000;20:7556–7563. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-20-07556.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garber DA, Schaffer PA, Knipe DM. A LAT-associated function reduces productive-cycle gene expression during acute infection of murine sensory neurons with herpes simplex virus type 1. Journal of Virology. 1997;71:5885–5893. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.8.5885-5893.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodkin ML, Ting AT, Blaho JA. NF-kB is required for apoptosis prevention during herpes simplex virus type 1 infection. Journal of Virology. 2003;77:7261–7280. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.13.7261-7280.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson G, Peng W, Jin L, Perng G-C, Nesburn AB, Wechsler SL, Jones C. Regulation of caspase 8- and caspase 9-induced apoptosis by the herpes simplex virus latency-associated transcript. Journal of Neurovirology. 2002;8:103–111. doi: 10.1080/13550280290101085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornung V, Ellegast J, Kim S, Brzozka K, Jung A, Kato H, Poeck H, Akira S, Conzelmann KK, Schlee M, Endres S, Hartmann G. 5′-Triphosphate RNA is the ligand for RIG-I. Science. 2006;314:994–997. doi: 10.1126/science.1132505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inman M, Perng G-C, Henderson G, Ghiasi H, Nesburn AB, Wechsler SL, Jones C. Region of herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-associated transcript sufficient for wild-type spontaneous reactivation promotes cell survival in tissue culture. Journal of Virology. 2001;75:3636–3646. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.8.3636-3646.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin L, Carpenter D, Moerdyk-Schauwecker M, Vanarsdall AL, Osorio N, Hsiang C, Jones C, Wechsler SL. Cellular FLIP can substitute for the herpes simplex virus type 1 LAT gene to support a wild type virus reactivation phenotype in mice. Journal of Neurovirology. 2008;14:389–400. doi: 10.1080/13550280802216510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin L, Perng G-C, Nesburn AB, Jones C, Wechsler SL. The baculovirus inhibitor of apoptosis gene (cpIAP) can restore reactivation of latency to a herpes simplex virus type 1 that does not express the latency associated transcript (LAT) Journal of Virology. 2005:12286–12295. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.19.12286-12295.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin L, Perng G-C, Brick DJ, Naito J, Nesburn AB, Jones C, Wechsler SL. Methods for detecting the HSV-1 LAT anti-apoptosis activity in virus infected tissue culture cells. Journal of Virological Methods. 2004;118:9–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2004.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin L, Peng W, Perng G-C, Nesburn AB, Jones C, Wechsler SL. Identification of herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) latency associated transcript (LAT) sequences that both inhibit apoptosis and enhance the spontaneous reactivation phenotype. Journal of Virology. 2003;77:6556–6561. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.11.6556-6561.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones C. Alphaherpesvirus latency: its role in disease and survival of the virus in nature. Advances in Virus Research. 1998;51:81–133. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3527(08)60784-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones C. Herpes simplex virus type 1 and bovine herpesvirus 1 latency. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2003;16:79–95. doi: 10.1128/CMR.16.1.79-95.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurak I, Kramer MF, Mellor JC, van Lint AL, Roth RP, Knipe DM, Coen DM. Numerous conserved and divergent microRNAs expressed by herpes simplex viruses 1 and 2. Journal of Virology. 2010;84:4569–4672. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02725-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato H, Takeuchi O, Mikamo-Satoh E, Hirai R, Kawai T, Matsushita K, Hiiragi A, Dermody TS, Fujita T, Akira S. Length-dependent recognition of double-stranded ribonucleic acids by retinoic acid-inducible gene-I and melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2008;205:1601–1610. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katze MG, Heng Y, Gale M. Viruses and interferon: fight for supremacy. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2002;2:675–686. doi: 10.1038/nri888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi S, Ihiguro Y, Imaizumi T, Matsumiya T, Yoshida H, Ota K, Sakuraba H, Yamagata K, Suto Y, Tanji K, Haga T, Wakabayashi K, Fukuda S, Satoh K. Retinoic acid-inducible gene-I is constitutively expressed and involved in IFN-gamma-stimulate CXCL9-11 production in intestinal epithelial cells. Immunology Letters. 2009;123:9–13. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2009.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kok KH, Ng MHJ, Ching YP, Jin DY. Human TRBP and PACT interact with each other and associate with Dicer to facilitate the production of siRNA. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282:17649–17657. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611768200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kok KH, Liu P-Y, Ng M-HJ, Siu K-L, Au SWN, Jin DY. The double-stranded RNA-binding protein PACT functions as a cellular activator of RIG-I to facilitate innate immune antiviral response. Cell Host and Microbe. 2011;9:299–309. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause PR, Croen KD, Straus SE, Ostrove JM. Detection and preliminary characterization of herpes simplex virus type 1 transcripts in latently infected human trigeminal ganglia. Journal of Virology. 1988;62:4819–4823. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.12.4819-4823.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krummenacher C, Zabolotny JM, Fraser NW. Selection of a nonconsensus branch point is influenced by an RNA stem-loop structure and is important to confer stability to the herpes simplex virus 2-kilobase latency-associated transcript. Journal of Virology. 1997;71:5849–5860. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.8.5849-5860.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leaman DW, Chawla-Sarkar M, Vyas K, Reheman M, Tamai K, Toji S, Borden EC. Identification of X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis-associated factor-1 as an interferon-stimulate gene that augments TRAIL Apo2L-induced apoptosis. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277:28504–28511. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204851200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HH, Dadgostar H, Cheng Q, Shu J, Cheng G. NF-kB-mediated upregulation of Bcl-X and Bfl-1/A1 is required for CD40 survivial signaling in B lymphocytes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96:9136–9141. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.9136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y, Hur I, Park S-Y, Kim Y-K, Suh MR, Kim VN. The role of PACT in the RNA silencing pathway. EMBO Journal. 2006;25:522–532. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Carpenter D, Hsiang C, Wechsler SL, Jones C. The herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-associated transcript (LAT) locus inhibits apoptosis and promotes neurite sprouting in neuroblastoma cells following serum starvation by maintaining active AKT (protein kinase B) Journal of General Virology. 2010;91:858–866. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.015719-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mador N, Panet A, Latchman D, Steiner I. Expression and splicing of the latency-associated transcripts of herpes simplex virus type 1 in neuronal and non-neuronal cell lines. Journal of Biochemistry. 1995;117:1288–1297. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a124857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mador N, Goldenberg D, Cohen O, Panet A, Steiner I. Herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-associated transcripts suppress viral replication and reduce immediate-early gene mRNA levels in a neuronal cell line. Journal of Virology. 1998;72:5067–5075. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.6.5067-5075.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marissen W, Patel AJ. Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4G is targeted for proteolytic cleavage by casapse 3 during inhibition of translation in apoptotic cells. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1998;18:7565–7574. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.12.7565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin SJ, Lennon SV, Bonham AM, Cotter TG. Induction of apoptosis (programmed cell death) in human leukemic HL-60 cells by inhibition of RNA or protein synthesis. Journal of Immunology. 1990;145:1859–1867. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson MP, Meffert MK. Roles for NF-kB in nerve cell survival, plasticity, and disease. Cell Death and Differentiation. 2006;13:852–860. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell WJ, Lirette RP, Fraser NWNW. Mapping of low abundance latency-associated RNA in the trigeminal ganglia of mice latently infected with herpes simplex virus type 1. Journal of General Virology. 1990;71:125–132. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-71-1-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mott K, Osorio N, Jin L, Brick D, Naito J, Cooper J, Henderson G, Inman M, Jones C, Wechsler SL, Perng G-C. The bovine herpesvirus 1 LR ORF2 is crucial for this gene's ability to restore the high reactivation phenotype to a Herpes simplex virus-1 LAT null mutant. Journal of General Virology. 2003;84:2975–2985. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.19421-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng W, Henderson G, Perng G-C, Nesburn AB, Wechsler SL, Jones C. The gene that encodes the herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-associated transcript influences the accumulation of transcripts (Bcl-xL and Bcl-xS) that encode apoptotic regulatory proteins. Journal of Virology. 2003;77:10714–10718. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.19.10714-10718.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng W, Vitvitskaia O, Carpenter D, Wechsler SL, Jones C. Identification of two small RNAs within the first 1.5-kb of the herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) encoded latency-associated transcript (LAT) Journal of Neurovirology. 2008;14:41–52. doi: 10.1080/13550280701793957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perng G-C, Maguen B, Jin L, Mott KR, Osorio N, Slanina SM, Yukht A, Ghiasi H, Nesburn AB, Inman M, Henderson G, Jones C, Wechsler SL. A gene capable of blocking apoptosis can substitute for the herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-associated transcript gene and restore wild-type reactivation levels. Journal of Virology. 2002;76:1224–1235. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.3.1224-1235.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perng G-C, Jones C, Ciacci-Zanella J, Stone M, Henderson G, Yukht A, Slanina SM, Hoffman FM, Ghiasi H, Nesburn AB, Wechsler SL. Virus-induced neuronal apoptosis blocked by the herpes simplex virus latency-associated transcript (LAT) Science. 2000;287:1500–1503. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5457.1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perng G-C, Esmail D, Slanina S, Yukht A, Ghiasi H, Osorio N, Mott KR, Maguen B, Jin L, Nesburn AB, Wechsler SL. Three herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-associated transcript mutants with distinct and asymmetric effects on virulence in mice compared with rabbits. Journal of Virology. 2001;75:9018–9028. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.19.9018-9028.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perng G-C, Dunkel EC, Geary PA, Slanina SM, Ghiasi H, Kaiwar R, Nesburn AB, Wechsler SL. The latency-associated transcript gene of herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) is required for efficient in vivo spontaneous reactivation of HSV-1 from latency. Journal of Virology. 1994;68:8045–8055. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.12.8045-8055.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perng G-C, Ghiasi H, Slanina SM, Nesburn AB, Wechsler SL. The spontaneous reactivation function of the herpes simplex virus type 1 LAT gene resides completely within the first 1.5-kilobases of the 8.3-kilobase primary transcript. Journal of Virology. 1996a;70:976–984. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.2.976-984.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perng GC, Ghiasi H, Slanina SM, Nesburn AB, Wechsler SL. The spontaneous reactivation function of the herpes simplex virus type 1 LAT gene resides completely within the first 1.5-kilobases of the 8.3-kilobase primary transcript. Journal of Virology. 1996b;70:976–984. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.2.976-984.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichlmair A, Schulz O, Tan CP, Naslund TI, Liljestrom P, Weber F, Reis e Sousa C. RIG-I-mediated antiviral responses to single-stranded RNA bearing 5′-phosphates. Science. 2006;314:997–1001. doi: 10.1126/science.1132998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rock DL, Nesburn AB, Ghiasi H, Ong J, Lewis TL, Lokensgard JR, Wechsler SLSL. Detection of latency-related viral RNAs in trigeminal ganglia of rabbits latently infected with herpes simplex virus type 1. Journal of Virology. 1987;61:3820–3826. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.12.3820-3826.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvesen GS, Duckett CS. IAP proteins: blocking the road to death's door. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2002;3:401–410. doi: 10.1038/nrm830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlee M, Hartmann E, Coch C, Wimmenauer V, Janke M, Barchet W, Hartmann G. Approaching the RNA ligand for RIG-I? Immunological Reviews. 2009a;227:66–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00724.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlee M, Roth A, Hornung V, Hagmann CA, Wimmenauer V, Barchet W, Coch C, Janke M, Mihailovic A, Wardle G, Juranek S, Kato H, Kawai T, Poeck H, Fitzgerald KA, Takeuchi O, Akira S, Tuschl T, Latz E, Ludwig J, Hartmann G. Recognition of 5′-triphosphate by RIG-I helicase requires short blunt double-stranded RNA as contained in panhandle of negative-strand virus. Immunity. 2009b;31:25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt A, Schwerd T, Hamm W, Hellmuth JC, Cui S, Wenzel M, Hoffmann FS, Michallet MC, Besch R, Hopfner KP, Endres S, Rothenfusser S. 5′-triphosphate RNA requires base-paired structures to activate antiviral signaling via RIG-I. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:12067–12072. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900971106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen W, Jones C. Open reading frame 2, encoded by the latency-related gene of bovine herpesvirus 1, has antiapoptotic activity in transiently transfected neuroblastoma cells. Journal of Virology. 2008;82:10940–10945. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01289-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen W, Sa e Silva M, JaberF T, Vitvitskaia O, Li S, Henderson G, JonesF C. Two small RNAs encoded within the first 1.5 kb of the herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) latency-associated transcript (LAT) can inhibit productive infection, and cooperate to inhibit apoptosis. Journal of Virology. 2009;90:9131–9139. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00871-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens JG, Wagner EK, Devi-Rao GB, Cook ML, Feldman LT. RNA complementary to a herpesvirus alpha gene mRNA is prominent in latently infected neurons. Science. 1987;235:1056–1059. doi: 10.1126/science.2434993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumpter R, Jr., Loo YM, Foy E, Li K, Yoneyama M, Fujita T, Lemon SM, Gale M., Jr. Regulating intracellular antiviral defense and permissiveness to hepatitis C virus RNA replication through a cellular RNA helicase RIG-I. Journal of Virology. 2005;79:2689–2699. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.5.2689-2699.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takaaoka A, Hayakawa S, Yanai H, Negishi H, Kikuchi H, Sasaki S, Imai K, Shibue T, Honda K, Taniguchi T. Integration of interferon-a/b signalling to p53 responses in tumour suppression and antiviral defence. Nature. 2003;424:516–523. doi: 10.1038/nature01850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahasi K, Yoneyama M, Nishihori T, Hirai R, Kumeta H, Narita R, Gale M, Jr., Inagaki F, Fujita T. Nonself RNA-sensing mechanism of RIG-I helicase and activation of antiviral immune responses. Molecular Cell. 2008;29:428–440. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umbach JL, Kramer MF, Jurak I, Karnowski HW, Coen DM, Cullen BR. MicroRNAs expressed by herpes simplex virus 1 during latent infection regulate viral mRNAs. Nature. 2008;454:780–785. doi: 10.1038/nature07103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umbach JL, Kramer MF, Jural I, Karnowski HW, Coen DM, Cullen BR. Analysis of human alphaherpesvirus microRNA expression in latently infected human trigeminal ganglia. Journal of Virology. 2009;83:10677–10683. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01185-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varnell E, Kaufman H, Hill J, Thompson H. Cold stress-induced recurrences of herpetic keratitis in the squirrel monkeys. Ophthalmology and Visual Science. 1995;36:1181–1183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner EK, Bloom DC. Experimental investigation of herpes simplex virus latency. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 1997;10:419–443. doi: 10.1128/cmr.10.3.419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner EK, Devi-Rao G, Feldman LT, Dobson AT, Zhang YF, Flanagan WM, Stevens JG. Physical characterization of the herpes simplex virus latency-associated transcript in neurons. Journal of Virology. 1988a;62:1194–1202. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.4.1194-1202.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner EK, Flanagan WM, Devi-Rao G, Zhang YF, Hill JM, Anderson KP, Stevens JG. The herpes simplex virus latency-associated transcript is spliced during the latent phase of infection. Journal of Virology. 1988b;62:4577–4585. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.12.4577-4585.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Workman A, Sinani D, Pittayakhajonwut D, Jones C. A Protein (ORF2) Encoded by the latency related gene of bovine herpesvirus 1 interacts with Notch1 and Notch3. Journal of Virology. 2011;85:2536–2546. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01937-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Workman A, Eudy J, Smith L, Frizzo da Silva L, Sinani D, Bricker H, Cook E, Doster A, Jones C. Cellular transcription factors induced in trigeminal ganglia during dexamethasone-induced reactivation from latency stimulate bovine herpesvirus 1 productive infection and certain viral promoters. Journal of Virology. 2012;86:2459–2473. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06143-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Workman A, Jones C. Bovine herpesvirus 1 productive infection and bICP0 early promoter activity are stimulated by E2F1. Journal of Virology. 2010;84:6308–6317. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00321-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang CH, Murti A, Pfeffer LM. Interferon induces NF-kB-inducing kinase/tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor dependent NF-kB activation to promote cell survival. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280:31530–31536. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503120200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang CH, Murti A, Pfeffer SR, Kim JG, Donner DB, Pfeffer LM. Interferon a/b promote cell survival by activating nuclear factor kB through phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and Akt. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276:13756–13761. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011006200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang CH, Murti A, Pfeffer SR, Basu L, Kim JG, Pfeffer LM. IFNalpha/beta promotes cell survival by activating NF-kB. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97:13631–13636. doi: 10.1073/pnas.250477397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoneyama M, Fujita T. RNA recognition and signal transduction by RIG-I-like receptors. Immunological Reviews. 2009;227:54–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoneyama M, Kikuchi M, Natsukawa T, Shinobu N, Imaizumi T, Miyagishi M, Taira K, Akira S, Fujita T. The RNA helicase RIG-I has an essential function in double-stranded RNA-induced innate antiviral responses. Nature Immunology. 2004;5:730–737. doi: 10.1038/ni1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou J, Chang M, Nie P, Secombes CJ. Origin and evolution of the RIG-I like RNA helicase gene family. BMC Evolutionary Biology. 2009:9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-9-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwaagstra JC, Ghiasi H, Slanina SM, Nesburn AB, Wheatley SC, Lillycrop K, Wood J, Latchman DS, Patel K, Wechsler SL. Activity of herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-associated transcript (LAT) promoter in neuron-derived cells: evidence for neuron specificity and for a large LAT transcript. Journal of Virology. 1990;64:5019–5028. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.10.5019-5028.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]