Abstract

Sertoli cell tight junctions (SCTJs) of the seminiferous epithelium create a specialized microenvironment in the testis to aid differentiation of spermatocytes and spermatids from spermatogonial stem cells. SCTJs must be chronically broken and rebuilt with high fidelity to allow the transmigration of preleptotene spermatocytes from the basal to adluminal epithelial compartment. Impairment of androgen signaling in Sertoli cells perturbs SCTJ remodeling. Claudin (CLDN) 3, a tight junction component under androgen regulation, localizes to newly forming SCTJs and is absent in Sertoli cell androgen receptor knockout (SCARKO) mice. We show here that Cldn3-null mice do not phenocopy SCARKO mice: Cldn3−/− mice are fertile, show uninterrupted spermatogenesis, and exhibit fully functional SCTJs based on imaging and small molecule tracer analyses, suggesting that other androgen-regulated genes must contribute to the SCARKO phenotype. To further investigate the SCTJ phenotype observed in SCARKO mutants, we generated a new SCARKO model and extensively analyzed the expression of other tight junction components. In addition to Cldn3, we identified altered expression of several other SCTJ molecules, including down-regulation of Cldn13 and a noncanonical tight junction protein 2 isoform (Tjp2iso3). Chromatin immunoprecipitation was used to demonstrate direct androgen receptor binding to regions of these target genes. Furthermore, we demonstrated that CLDN13 is a constituent of SCTJs and that TJP2iso3 colocalizes with tricellulin, a constituent of tricellular junctions, underscoring the importance of androgen signaling in the regulation of both bicellular and tricellular Sertoli cell tight junctions.

Sertoli cell tight junctions (SCTJs) of the seminiferous epithelium create a specialized microenvironment in the testis to aid in the differentiation of sperm from spermatogonial stem cells. The continuous network of tight junction fibrils between adjacent Sertoli cells divides the seminiferous epithelium into two functionally distinct compartments. The basal compartment harbors the germline stem cells, progenitor transit-amplifying spermatogonial cells, and preleptotene spermatocytes, whereas the adluminal compartment contains the meiotic spermatocytes and differentiating postmeiotic spermatids. SCTJs contribute to the function of the blood-testis barrier (BTB) by blocking the passive movement of molecules through the Sertoli cell paracellular space and by providing immune privilege to differentiating germ cells (1–4).

SCTJs differ from other epithelial tight junctions in several ways. Unlike most polarized epithelia, in which tight junctions are apical, the seminiferous epithelium is reversed, ie, the tight junctions are located basally. In addition, the seminiferous epithelium is the only known epithelium that is regularly traversed by another cell type, preleptotene spermatocytes. Every 8.6 days (in the mouse), the SCTJs undergo complete dissolution and reformation to allow the translocation of syncytial chains of preleptotene spermatocytes from the basal to the adluminal compartment. Three-dimensional (3-D) imaging during this dynamic stage has revealed that extensive reorganization of the SCTJ occurs wherein the preleptotene cells are temporarily enclosed in a double-layered tight junction compartment (5).

Claudins are the primary structural and functional units of tight junctions and are encoded by 26 genes in the mouse genome (6–11). They are 4-pass integral membrane proteins connected to the intracellular actinomyosin cytoskeleton by the tight junction proteins (TJPs) (TJP1, TJP2, and TJP3, also referred to as ZO-1, ZO-2 and ZO-3, respectively) (12). Claudins (CLDNs) 3, 5, and 11 have been reported to localize to SCTJs (13–17). Unlike Cldn3, which is expressed in a stage-specific manner, CLDN11 is constitutively expressed in SCTJs throughout all stages of the seminiferous epithelial cycle. Cldn11 mutant mice are sterile owing to the loss of SCTJ maintenance (17). Like CLDN3, CLDN5 is expressed in the SCTJs in a stage-specific manner with Cldn5 knockout mice displaying early postnatal lethality, precluding assessment of CLDN5 in SCTJ function (18). However, in Etv5 mutant mice, which have reduced levels of Cldn5, SCTJs are compromised (15). Mutations of Tjp1 and Tjp2 produce early embryonic lethal phenotypes; however, Tjp2+/+/Tjp2−/− chimeras that survive to adulthood show reduced fertility and have a defective SCTJ barrier (19).

Sertoli cells express high levels of AR during spermatogenic stages when preleptotene spermatocytes traverse the SCTJ barrier (20–22). Genetic studies have established that testosterone, acting through the androgen receptor (AR) expressed in Sertoli cells, is essential for germ cell differentiation (23–25). Furthermore, in vivo gene ablation studies have shown that Sertoli cells require AR for proper SCTJ formation and function (16, 26–29). How androgens regulate tight junction remodeling is not known.

The expression of several SCTJ components is altered in Sertoli cell androgen receptor knockout (SCARKO) models (16, 27). CLDN3 is expressed during the spermatogenic stages containing the migrating preleptotene spermatocytes (16) and localizes to the newly forming SCTJs (5). Unlike other TJP–encoding genes, which show a moderate 2- to 5-fold level reduction in SCARKO testes, Cldn3 levels are reduced 50-fold (27).

The long-term fertility of males suggests that the chronic breaking and rebuilding of SCTJs occurs with high fidelity. The identification of Cldn3 as an AR-regulated gene, its localization to newly forming SCTJs, and the SCTJ defects in SCARKO models suggest that it is an AR effector molecule in the remodeling stage (5, 16, 27). Here, we tested the in vivo consequences of Cldn3 loss on SCTJs, BTB integrity, and reproductive capacity. We also created a new SCARKO model and identified additional androgen-responsive tight junction components whose expression is altered in SCARKO mutants.

Materials and Methods

Animals

All mice were bred and maintained in a high barrier facility at The Jackson Laboratory. All experimental protocols were approved by The Jackson Laboratory Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (permit no 07007) and were in accordance with accepted institutional and government policies outlined in the NIH Guide for the Care and Use Laboratory Animals (1996; revised 2011).

Gene targeting and generation of a Cldn3 floxed allele

To construct the conditional Cldn3 gene–targeting vector, a BAC clone (RP23-153011) containing the Cldn3 genomic fragment was obtained from a mouse RP23 BAC genomic library (Children's Hospital Oakland Research Institute [CHORI]). Xmn1-digested DNA fragments were subcloned into the pBluescript (pBS) vector. Colony hybridization was performed using a Cldn3 probe to select the pBS clone containing the 5.4-kb genomic fragment of the Cldn 3 locus. A LoxP site containing a synthetic oligo was introduced into the BstB1/Not1 site in the 3′-untranslated region of the Cldn3 gene. The BstB1 5′ overhang in the synthetic oligo was modified to obtain a nonfunctional BstB1 site to facilitate screening of correctly targeted clones at later steps.

A 1.6-kb EcoRV-Xmn fragment, 3′ of the Cldn3 locus, was subcloned into the 5′ multiple cloning site of the targeting vector pBS4600 (kindly provided by Richard Palmiter, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, Washington). A 3.7-kb fragment containing a 2.4-kb 5′ genomic region and the Cldn3 exon was subcloned into the 3′ multiple cloning site of the targeting vector pBS4600. The functionality of the LoxP sites was confirmed by excision using an in vitro Cre reaction (New England Biolabs). The Cldn3 conditional knockout vector was linearized with AscI and electroporated into 129S1/SvImJ embryonic stem (ES) cells. ES cell clones of interest were enriched by a positive selection based on neomycin and a negative selection based on thymidine kinase and diphtheria toxin A. ES cell clones with 1 targeted allele were identified by Southern blot analysis by probing Bsm1/BstB1- or Bsm1-digested DNA with PCR-generated probes. Targeted ES clones were microinjected into C57BL/6 blastocysts to generate chimeric mice. The chimeric males were crossed to C57BL/6 females to identify mice with germline transmission.

Mice harboring the chimeric floxed Cldn3 allele were crossed to both 129S1/SvImJ and C57BL/6J females. The B6129 F1 progeny were backcrossed to control C57BL/6J for 7 generations to obtain pure C57BL/6 mice for experimental purposes. The floxed C57BL/6 strain was crossed to a transgenic cytomegalovirus (CMV)-Cre deleter strain, (B6.C-Tg[CMV-cre]1Cgn/J, stock no 006054; The Jackson Laboratory) and bred as above to generate a global deletion of Cldn3 on the C57BL/6 background.

Gene targeting and generation of an Ar exon 1 floxed allele

To generate an Ar conditional allele, a 9.5-kb SacI fragment containing the first exon of Ar was subcloned into the pBS vector from the 12.5-kb fragment used to generate the Artm1Reb allele (25). A LoxP site and a unique BstEII restriction enzyme site were introduced at a StuI site 2.5 kb from the transcriptional start site of Ar. A neomycin resistance (NeoR) cassette was inserted in a BamHI site immediately 3′ of the splice donor of Ar exon 1. The NeoR was flanked by Flp-recombinase target (FRT) sites and by a single LoxP site at the 3′ end of the cassette (a generous gift from Dr Gail Martin, University of California at San Francisco). A SalI-XhoI fragment containing a CMV promoter–driven diphtheria toxin (Dta) was inserted into an XhoI site in the polylinker sequence at the 3′ end of the construct for use in negative selection in ES cells. A linearized targeting vector was electroporated into 129S1/SvImJ ES cells, and G418-resistant clones were expanded for Southern blot analyses. Properly targeted clones were identified by probing Southern blots containing EcoRV-digested genomic DNA (gDNA) with an Ar exon 1 probe. Clones were then electroporated with a CMV-Flp recombinase–expressing plasmid to remove the NeoR cassette flanked by the FRT sites. Clones were analyzed by Southern blot using EcoRV/BstEII-digested gDNA. NeoR-negative targeted ES clones were microinjected into C57BL/6J blastocysts to generate chimeric mice. The chimeric males were crossed to C57BL/6J and 129S1 to produce B6129F1 hybrid and 129S1 inbred mice carrying the targeted Artm2Reb allele. 129S1-Artm2Reb heterozygous females were bred with 129S1-Tg(Amh-cre) males to produce SCARKO male mice. B6129F1-Artm2Reb heterozygous females were bred with 129-Alpltm1(cre)Nagy/J males to produce heterozygous Artm2Reb females that have a deleted exon 1 in the germline due to the Cre expression from the Alpltm1(cre)Nagy allele. These females were mated with 129S1/SvImJ wild-type males to produce male mice containing whole-body knockout of Ar exon 1.

Southern blots

gDNA was purified using a DNeasy kit (QIAGEN). Then 10 μg of gDNA was digested overnight at 65°C with BstB1/Bsm1 or Bsm1 and resolved on an 0.8% agarose gel by electrophoresis for 19 hours at 40 V. The gel was depurinated in 0.25 M HCl for 10 minutes, rinsed with water, and denatured in 0.5 M NaOH and 1.0 M NaCl for 30 minutes on a shaker. After rinsing with water, the gel was then neutralized in 0.5 M Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) and 1.5 M NaCl for 30 minutes. DNAs were transferred onto a Zeta-Probe GT Membrane (Bio-Rad Laboratories) by capillary transfer for 19 hours at room temperature in 20× SSC. Blots were dried for 30 minutes, UV cross-linked, and prehybridized for 60 minutes at 65°C in 6× standard saline citrate (SSC), 5× Denhardt's solution, 0.5 mg/mL salmon sperm DNA, 0.5% SDS, and 10% dextran sulfate. An additional 10 mL of the prehybridization buffer containing 50 ng of radiolabeled probe was added to the membrane and hybridized overnight at 65°C. For radiolabeling, 50 ng of the probe was heated at 95°C for 3 minutes, placed on ice for 2 minutes, and labeled with 5 μl of [32P]CTP (BLU513H250, Perkin-Elmer) at 37°C for 60 minutes. Unlabeled nucleotides were removed using a MicroSpin column (Amersham). The purified probe was boiled for 5 minutes before hybridization. The blots were washed twice for 45 minutes at 65°C in 2× SSC and 0.5% SDS and then for 30 minutes at 65°C in 0.15× SSC and 0.5% SDS and for 20 minutes at room temperature in 0.1× SSC and 0.1% SDS, followed by exposure to phosphor screens at room temperature for 3 days. The screens were scanned in a Fuji FLA-5100 scanner (Fujifilm).

Genotyping

Mice were genotyped by mixing the following primers in a single PCR tube for detection of the floxed allele: P1 (5′-CGTCAGTTTTCGAAGGGCAGTTG-3′) and P2 reverse (5′-GGTGATCTCCAGGCCCATGG-3′). To confirm the deletion of the Cldn3 exon the following primers were used: E1 (5′-CCCAGTCTCAGAAGCCAGTC-3′) and E2 (5′-GATAAACCTCGCTCGCCATA-3′). The expected amplicon sizes were 127, 315, and 161 bp for the Cldn3 wild-type, null, and conditional floxed alleles, respectively. PCR was used to identify the Artm2Reb allele by detection of the 5′ LoxP and 3′ LoxP sites in separate reactions. An Ar P1 (5′-CAGCACCCTACACTAGAATACTG-3′) and Ar P2 (5′- AATGACCTGAGAGTGCTTCCTCC-3′) primer pair amplify the 5′ LoxP site to produce a 200- and 220-bp control and targeted conditional allele, respectively. An Ar P3 (5′-AGGGCACAGAGTAAGCAGTTTGC-3′) and Ar P4 (5′-TCCAGATGTAGGACAGACCTTCC-3′) primer pair amplify the 3′ FRT-LoxP site to produce a 200- and 220-bp control and targeted conditional allele, respectively. The post-Cre recombinase allele is amplified using the Ar P1 and Ar P4 primers and produces a 450-bp product. Genotyping of the Cre transgenic allele included the primer set, forward 5′-TGGTTTCCCGCAGAACCTGAAG-3′ and reverse 5′-GAGCCTGTTTTGCACGTTCACC-3′, and yielded a 220-bp product.

Histology and immunostaining

Testes from control and mutant mice were weighed, fixed overnight at 4°C in Bouin's fixative, rinsed with water, and dehydrated for paraffin embedding. For histological analysis, 5-μm sections were cut and mounted on glass slides and stained with periodic acid/Schiff reagent using the standard protocol. For immunocytochemical studies, tissues were fixed in neutral buffered formalin, rinsed with PBS followed by dehydration in 70% ethanol, and then embedded. Sections were deparaffinized (2 times for 10 minutes each) in Xylene and rehydrated (2 times for 5 minutes each in 100% ethanol, 1 for 5 minutes in 95% ethanol, 1 time for 5 minutes in 70% ethanol, 1 time for 5 minutes in 50% ethanol, and 1 time for 5 minutes in PBS). For antigen retrieval, slides were boiled in 10 mM sodium citrate (pH 6.0) for 10 minutes. The sections were blocked in 3% normal donkey serum for 1 hour at room temperature followed by overnight incubation in primary antibody in 3% normal donkey serum at 4°C. After washes in PBS, sections were incubated with secondary donkey antirabbit or antimouse antibodies conjugated to Alexa Fluor 568 or Alexa Fluor 488 (Molecular Probes). Slides were rinsed in PBS and mounted in Vectashield mounting medium with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Vector Laboratories). Images were taken on a Nikon Eclipse E600W epifluorescence microscope equipped with an EXi Aqua Camera (model no 01-EXi-AQA-R-F-M-14C) from QImaging. Images were acquired with Image-Pro Plus 7.0 software using a ×20 0.75 numerical aperture or a ×40 0.90 dry objective lens.

For staining with CLDN13 and CLDN15 antibodies, testis sections were frozen in a methyl-butanol bath dipped in liquid nitrogen, and 5-μm sections were mounted on glass slides and treated with acetone at −20°C for 10 minutes. Samples were then blocked in 1% BSA for 30 minutes followed by incubation with the primary antibody for 20 minutes at 37°C. Samples were then washed in PBS and incubated with secondary antibody for 20 minutes at 37°C. Samples were washed 3 times in PBS for 5 minutes each before mounting in Vectashield. For staining with TJP2iso3-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated antibodies, samples were first incubated with antitricellulin and Alexa Fluor 568 secondary antibody as mentioned above. Sections were then washed in PBS followed by a quick fixation with 2% paraformaldehyde for 5 minutes before staining with TJP2iso3-FITC–conjugated antibodies. Stage-specific visualization of TJP2iso3 levels was observed best in testicular sections embedded in OCT and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 5 minutes followed by block and incubation in antibodies as mentioned above.

Epididymal sperm counts

A single epididymis from each animal was minced in 1 mL of PBS. Sperm were allowed to swim out for 1 hour at 37°C. Epididymal sperm counts were determined using a hemocytometer.

Whole-mount immunostaining

Adult (2–3 months old) 129S1/SvImJ or C57BL/6J male mice were killed with CO2, and the testes were immediately transferred into chilled PBS. The tunica albuginea was removed, and the seminiferous tubules were teased apart. The interstitial cells were loosened from the tubules by a 5-minute incubation with 0.5 mg/mL collagenase (Sigma-Aldrich) at room temperature (RT). The tubules were rinsed 3 times with PBS and fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences) for 6 hours at 4°C.

Paraformaldehyde-fixed tubules were rinsed 3 times with PBS and permeabilized with 0.25% NP-40 in PBS-T (PBS + 0.05% Tween 20) for 25 minutes at RT. The tubules were rinsed 3 times with PBS-T for 5 minutes and blocked using 5% normal donkey serum (Jackson ImmunoResearch) in PBS-T for 2 hours at RT or overnight at 4°C. The tubules were incubated with primary antibody diluted in PBS-T with 5% normal donkey serum overnight at 4°C and rinsed 3 times with PBS-T for 5 minutes. The tubules were then reacted with secondary antibodies for 1 hour at room temperature. Samples were rinsed 3 times with PBS-T for 5 minutes with DAPI added to the first rinse. The tubules were spread in a drop of Vectashield with DAPI, covered with a coverslip, and sealed with nail polish.

Antibodies

Antibodies were purchased from the following companies: rabbit α-CLDN11 H-107 (1:200), goat-α-OCLN (1:200), rabbit α-human AR (1:200), goat antimouse ALB (P-20, 1:500), and normal rabbit IgG from Santa Cruz Biotechnology; rabbit α-CLDN3 (1:100) from Zymed Laboratories; rabbit α-ZO-2 and phalloidin (1:200) from Invitrogen; rabbit α-CLDN13 (1:200) from Novus Biologicals; mouse α-FLAG M2 (1:1000) from Sigma-Aldrich; rabbit α-CLDN15 (1:30) from Life Technologies; and rabbit α-tricellulin (1:300; LS-C107991–50) from LifeSpan Biosciences Inc. A peptide antibody against the N-terminal sequence (SGPGKKQALRTTGK) unique to TJP2iso3 was generated in rabbit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Secondary donkey antirabbit or antimouse antibodies conjugated to Alexa Fluor 568 or Alexa Fluor 488 were used to visualize the specific proteins with fluorescence microscopy (1:800; Molecular Probes).

Antibody conjugation

Antibody conjugation was performed as described previously (30). In brief, 1 mL of antibody in carbonate buffer (pH 9.3) was mixed slowly with 50 μL of 1 mg/mL FITC, isomer 1 (F7250; Sigma-Aldrich) in dimethylsulfoxide, and the TJP2iso3 antibodies were conjugated overnight at 4°C. Unconjugated fluorescein was removed using a Sephadex G-25 coarse (GE Life Sciences) column.

Confocal microscopy of seminiferous tubules

The seminiferous tubules were imaged on an AOBS equipped Leica TCS SP2 laser scanning confocal microscope with a ×63 HCX Plan-Apochromat 1.3 numerical aperture glycerol immersion lens. Leica LCS software was used for image acquisition. The images were acquired using serial sections starting from the basement membrane and ending on the apical side of the SCTJs with an average voxel size of 150 nm × 150 nm × 150 nm. The stage of the seminiferous epithelial cycle at which the series was taken was confirmed using both differential interference microscopy and DAPI optical cross sections. The image series were rendered using the Amira 4.1.2 software package (Visage Imaging). Heat map colorimetrics were used; DAPI fluorescence is represented on a blue to white scale and red fluorescence on a red to bright yellow scale. Isosurfaces were rendered using a fixed color.

Tracer studies

Mice were killed with CO2 and perfused through the left ventricle with 30 mL of saline (0.85% NaCl) solution (37°C) containing 2 U of heparin/mL to flush out the blood. Lanthanum hydroxide (pH 7.8) was prepared by slowly adding 0.1 N and then 0.01 N NaOH dropwise to 4% (w/v) La(NO3)3 · 6H2O (Sigma-Aldrich) in degassed water. Ten-week-old mice were perfused through the left ventricle with 50 mL of a freshly prepared solution of 1:1 mixture of (5% glutaraldehyde [Electron Microscopy Sciences] in 0.2 M S-collidine, pH 7.4 [Polysciences Inc] and 4% lanthanum, pH 7.8). The hardened testes were dissected, cut into small cubes (2–3 mm3), and immersed in the same lanthanum containing fixative for an additional 1 hour at room temperature. After repeated rinsing in the buffer (0.2 M S-collidine, containing 2% lanthanum), the tissues were fixed in collidine-buffered 1% osmium tetroxide (1 volume of 0.2 M S-collidine and 2 volumes of 2% osmium tetroxide [Electron Microscopy Sciences]) for 1 hour and then rapidly dehydrated through 50, 80, and 95% and absolute alcohols containing 2% lanthanum. After dehydration, tissues were embedded in Epon 812-Araldite 506 (Electron Microscopy Sciences). Thin sections were prepared for light microscopy. Selected ultrathin sections (90 nm) were mounted on 100-mesh copper grids and lightly contrasted with 2% uranyl acetate in distilled water for 1 hour and 0.5% lead citrate in distilled water for 30 minutes. The grids were examined in a 1230 JEM transmission electron microscope (JEOL USA) using an AMT ORCA HR high-resolution camera using AMT Image Capture Engine software, version 602. Images are in the 2240 × 2240 pixel format.

SDS-PAGE electrophoresis and immunoblotting

Whole testes were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and then ground to a fine powder with a cold mortar and pestle. The tissue powder was suspended in NaHCO3 buffer (1 mM NaHCO3 and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, pH 7.5) at a concentration of 100 mg of tissue/1 mL of buffer. The tissues were sonicated for 16 seconds at 30 W power in a Misonix Sonicator 3000 Ultrasonic Cell Disruptor (Cole-Parmer) and then cooled on ice for 30 minutes. The samples were boiled in 1× Laemmli buffer at a final concentration of 25 mg of tissue/1 mL of buffer. The samples were resolved on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Immunobilon-P; Millipore). The blots were rinsed in PBS-T (PBS and 0.1% Tween 20) and were blocked in PBS-T with 5% w/v nonfat dry milk for 30 minutes at 37°C. The blots were then incubated overnight with primary antibody.

The blots were washed 3 times in PBS-T and incubated with goat antirabbit horseradish peroxidase secondary antibody (Bio-Rad Laboratories) at 37°C for 30 minutes as per the manufacturer's instruction. The blots were washed 3 times in PBS-T and developed with the ECL Plus detection reagent (GE Healthcare).

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis of tight junction components

To analyze any changes in the expression of tight junction components, whole testes were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and ground to a fine powder using a mortar and pestle. The powdered tissue was then homogenized using a QIAshredder column, and total RNA was extracted using an RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN). The RNA was then reverse transcribed using a SuperScript First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen). qPCR was performed on the cDNA using SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) and analyzed on an ABI 7500 Real-Time PCR Machine (Applied Biosystems). The sequence of each qPCR product was verified. To identify products not amplified within the testis, a cDNA pool derived from mouse kidney, liver, intestine, lung, testis, and thymus was used. Statistical analysis was performed using an unpaired two-tail Student t test (Q-Gene; http://bioinformatics.oxfordjournals.org/content/19/11/1439.short).

Rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE)

The SMARTer RACE cDNA Amplification Kit (634923; Clontech) was used to verify the full coding sequence for TJP2 using primers based on a RIKEN clone from a full-length enriched mouse cDNA library (AK076689.1). 3′ and 5′ RACE-ready cDNA was made using 0.5 μg of total RNA from C57BL/6J mouse testes and SMARTScribe reverse transcriptase according to the manufacturer's instructions. For RACE PCR amplification, gene-specific primers 5′-CCTCTTTTGGAATCCTTCTGCAGGGTCACGG-3′ (antisense 295R) or 5′-CCGTGACCCTGCAGAAGGATTCCAAAAGAGG-3′ (sense 295F) and the Universal primer from the kit was used in 50 μL of PCR using Advantage 2 Polymerase Mix (639206; Clontech). The program used for amplification was 5 cycles at 94°C for 30 seconds and 72°C for 3 minutes, 5 cycles at 94°C for 30 seconds, 70°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 3 minutes, and a final 25 cycles at 94°C for 30 seconds, 68°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 3 minutes. The PCR products were cloned into a TA cloning vector from Promega, Inc, and 5 to 6 clones were sequenced for each RACE reaction.

Tjp2iso3 cloning and expression

RNA from whole testis was isolated using a RiboPure Kit (Life Technologies). cDNA preparation was performed using a SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System (Life Technologies). Full-length TJP2iso3 cDNA was cloned in-frame into a C-terminal 3xFLAG tag PCMV-3Tag-3a vector (Agilent Technologies) using primers containing EcoR1 and XhoI site overhangs. FLAG-tag TJP2iso3 constructs were transfected into Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells (ATCC) using Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent (Life Technologies), and cell lysates were analyzed after 24 hours.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay

Single-cell suspensions were prepared from seminiferous tubules as described previously (31). ChIP analysis was conducted using the EZ-ChIP Kit and protocol (17–371; Millipore EMD). In brief, cells were cross-linked, lysed, and frozen at a concentration of 1 × 107 cells/mL at −80°C. Cells were then thawed, and the chromatin was fragmented for 10 minutes using a Bioruptor (B01010002; Diagenode) with the power setting at high and cycles of 30 seconds on and 30 seconds off. Precleared chromatin (106 cell equivalents) was incubated overnight at 4°C with 5 μg of rabbit antihuman androgen receptor (sc-816 X; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or 5 μg of normal rabbit IgG (sc-2027). The samples were incubated with protein G agarose for 1 hour and then washed according to the manufacturer's instructions. Immune complexes were eluted from the beads, reverse cross-linked, and deproteinated before DNA fragments were purified using a QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (28106; Qiagen). The sample DNA concentration was determined using the Qubit High Sensitivity Fluorometric Quantitation Kit (Q32851; Life Technologies). Real-time qPCR amplification was performed with 30 pg of DNA from ChIP experimental, control, and input samples. Rhox5 was used as a positive control (32), and Lin28a was used as a negative control.

Results

Complete loss of CLDN3 in Cldn3 targeted mutant mice

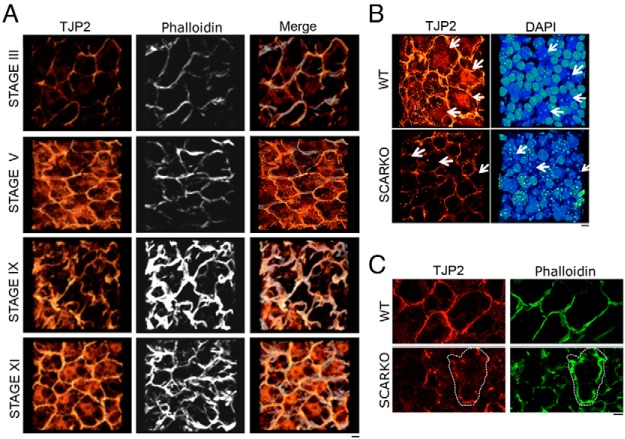

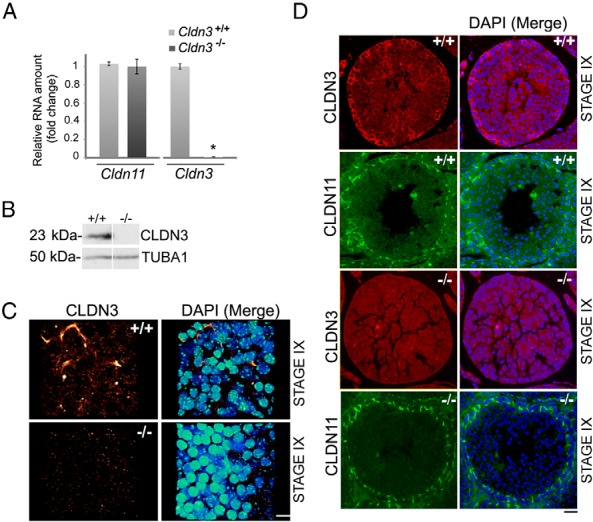

To determine the in vivo function of CLDN3 in SCTJ remodeling, we generated a Cldn3 targeted mutation in mice. Proper targeting was confirmed with Southern blot and PCR analyses of ES cells as well as the first-generation heterozygous (Cldn3Flox/+) mice derived from the ES cell containing chimeras (Supplemental Figure 1 A–D). A loss-of-function Cldn3 null allele was produced by breeding Cldn3Flox/+ mice with a transgenic mouse strain expressing Cre recombinase in the germline. Cldn3−/− mice were obtained by intercrossing heterozygous null mice. Expression of Cldn3 was completely abolished in adult liver, lung, and testes in Cldn3−/− mice, whereas expression of Cldn11, a member of the same gene family, was unchanged (Figure 1A and Supplemental Figure 1E). Western blot analysis of total testis protein from Cldn3−/− males confirmed the absence of CLDN3 protein as would be expected for the null allele that deletes the entire Cldn3 protein coding sequence (Figure 1B). Consistent with the above finding, whole-mount immunostaining of mutant testis seminiferous tubules showed that they were also deficient in CLDN3 expression normally observed in the newly forming tight junction (Figure 1C). In histological cross sections, mouse spermatogenesis can be defined by 12 stages (I–XII) based on the germ cell composition (33). CLDN3 localizes to newly forming SCTJs, which occurs during stages VIII to X of the spermatogenic cycle (5, 16). We assayed CLDN3 protein localization in stage IX tubule cross sections by immunofluorescence microscopy. In control (Cldn3+/+) samples, CLDN3 was detected near the basal lamina of the epithelium, similar to CLDN11, a known component of the SCTJs (Figure 1D). This was in contrast to Cldn3−/− SCTJs, which lacked CLDN3 staining (Figure 1D). Notably, the staining pattern of CLDN11 was not altered, suggesting that this TJP, required for the maintenance of SCTJs, was present and grossly exhibited a preserved cellular distribution in Cldn3 mutant testes (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

Loss of CLDN3 transcripts and protein in Cldn3−/− testes. A, RT-qPCR analysis of Cldn3 and Cldn11 transcripts from adult testis of Cldn3−/− mice and littermate controls showing a loss of Cldn3 transcript. Error bars represent SEM. n = 3. *, P ≤ .01. B, Western blot analysis of total testis protein extracts prepared from control and Cldn3−/− mice probed with anti-CLDN3 antibody. α-tubulin (TUBA1) antibody was used as a loading control. C, A 3-D confocal reconstruction of a stage IX whole-mount seminiferous tubule immunostained for CLDN3 (red to yellow heat map) and counterstained with DAPI (DNA, blue to green heat map). CLDN3 staining is absent in Cldn3−/− seminiferous tubules. Scale bar corresponds to 10 μm. D, Immunofluorescence detection of CLDN3 (red) and CLDN11 (green) proteins on adult testis sections from control (+/+) and Cldn3−/− mice. CLDN3 protein was absent in Cldn3−/− stage IX tight junctions marked by CLDN11. Staging was determined by DAPI counterstaining (blue). Scale bar corresponds to 10 μm.

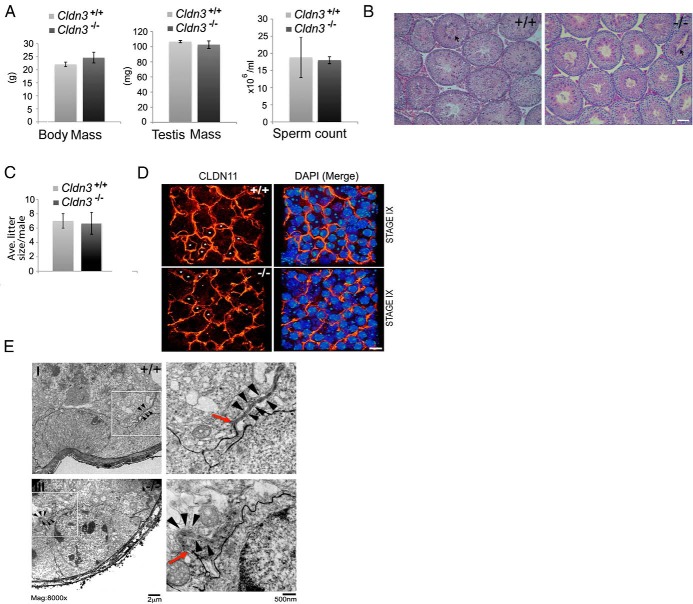

Unimpaired spermatogenesis in the absence of CLDN3

Unlike Cldn11 null mice, which exhibited male sterility and loss of SCTJs, adult Cldn3−/− mice are viable and have normal body and testis masses (Figure 2A) (7, 13, 17). We analyzed histological testis cross sections and observed all spermatogenetic stages in mutant testes (Figure 2B). Spermiation, the release of fully differentiated elongated spermatids into the tubule lumen in stage VIII, is indicative of successful completion of the spermatogonia cycle. Spermiation in mutant tubules at stage VIII was unaffected, and sperm numbers in the epididymides were comparable to those in controls (Figure 2, A and B). The functional capacity of sperm derived from Cldn3−/− testes was tested by mating with control dams. The average litter sizes produced by Cldn3−/− or littermate control males, when mated with wild-type females, were equivalent (Figure 2C). In addition to the testis, adult Cldn3−/− mice were subjected to histopathology studies of tissues that normally express CLDN3. No mutant-specific differences were detected (Supplemental Figure 1F).

Figure 2.

Qualitative and quantitative spermatogenesis persists in the absence of CLDN3, and SCTJs remain functionally intact. A, Body mass, testis mass, and epididymal sperm counts from 10-week-old control and Cldn3−/− males. n = 5. Error bars represent SEM. No difference between body mass, testis mass, and sperm numbers was detected. B, PAS-stained testis cross sections from 10-week-old control and Cldn3−/− mice. Cldn3−/− testis sections confirm the presence of all cell types and normal spermiation (arrow) in stage VIII tubules. Scale bar corresponds to 30 μm. C, When mated to 12-week-old control females; adult Cldn3−/− males produced litter sizes comparable to those of control males. n = 3. Error bars represent SEM. D, A 3-D confocal reconstruction of a stage IX whole-mount seminiferous tubule immunostained for CLDN11 (red to bright yellow heat map) to identify SCTJs. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue to green heat map). Migrating preleptotene spermatocytes were observed enclosed within the SCTJs in stage IX (marked by asterisks) of the seminiferous epithelial cycle in both control and Cldn3−/− mice. Scale bar corresponds to 10 μm. E, Electron micrographs of lanthanum colloid tracer studies. Electron microscopy analysis was performed on control and Cldn3−/− testes, after perfusion with lanthanum nitrate (tracer). The lanthanum tracer (black) permeates across the incomplete system of myoid cell layer tight junctions into the intercellular space between Sertoli cells and spermatogonia (insets I and III), where it is blocked by the SCTJs (red arrows). Insets (II and IV) show boxed regions magnified with representative SCTJs (black arrowheads). Diffusion of the tracer across the SCTJ barrier into the adluminal compartment was prevented in control and Cldn3−/− testes. Red arrows mark the point at which the diffusion of the tracer is restricted by the SCTJs.

Structural and functional integrity of Cldn3−/− SCTJs

During the translocation of germ cells across SCTJs, preleptotene spermatocytes are briefly enclosed in a transient intermediary compartment formed by old tight junctions on the adluminal side and newly forming basal tight junctions (5). CLDN3 is found bridging the gaps in the newly forming basal tight junctions, suggesting that it may play a critical role in new SCTJ formation (5). To visualize formation of the germ cell compartment formed during preleptotene cyst cell migration, we imaged the tight junctions using confocal microscopy on whole-mount tubule preparations. We immunostained tubules for CLDN11, a known component of the SCTJ, and imaged regions of the seminiferous tubules where preleptotene spermatocytes were translocating across the SCTJs. Control and Cldn3−/− tubules contained transient intermediary compartments marked by CLDN11, suggesting that the formation of the new tight junctions was not altered in the absence of CLDN3 (Figure 2D, asterisks).

As a complementary approach, we tested the functional integrity of the SCTJs in a permeability assay using lanthanum as an intercellular tracer. SCTJs form one of the most stringent barriers in mammals and restrict the passive permeability of proteins such as ferritin and peroxidase and small molecules such as lanthanum (1, 34, 35). Ultrastructural analysis of Cldn3−/− mice showed lanthanum penetration through the myoid cell tight junction layer of the tubules and the intercellular space around the spermatogonia in 25% of the tubules. However, the lanthanum failed to diffuse beyond the SCTJ into the adluminal compartment (Figure 2E, red arrow). These results were similar to those observed in control mice. Furthermore, the ultrastructure of the Cldn3−/− SCTJs was similar to that in control mice, exhibiting a series of electron-dense “kissing points,” representing lipid bilayers of adjacent Sertoli cell membranes in close proximity forming an impermeable barrier (Figure 2E, black arrows).

A compromised SCTJ can lead to loss of testicular immune privilege and result in testis-specific antibodies (29). Therefore, we tested for the presence of autoantibodies against postmeiotic germ cells in sera collected from control and Cldn3−/− mice. Histological sections of 8-week-old control testes were incubated with sera obtained from both Cldn3−/− mutant and control animals (n = 6). No serum samples, whether they were derived from mutant or control animals, showed immunoreactivity against germ cells (data not shown). This functional test suggests that testicular immune privilege is not compromised in mice lacking CLDN3. In aggregate, these data suggest that in Cldn3−/− mutants, SCTJs are structurally and functionally intact and capable of fully supporting spermatogenesis.

Creation of a new SCARKO model

The SCTJ phenotype disparity between Cldn3-null mice and SCARKO models suggests that additional molecular perturbations are present in the SCARKO testes, which may account for the SCTJ phenotype. Our previously described SCARKO model of AR depletion used the Artm1Reb allele (referred to herein as Artm1), which because of a cryptic splice acceptor in the NeoR gene cassette in intron 1, behaves as a hypomorph, independent of Cre-mediated recombination (25). Whereas the Artm1/Y;Tg(Amh-Cre) genetic model (referred to herein as SCARKOtm1) exhibits a loss-of-function phenotype in Sertoli cells, all remaining cell types in the mouse maintain the Ar hypomorphic state. The consequence of this is a compensatory elevation in testosterone levels due to the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal negative feedback loop (25, 36). In addition, the other existing SCARKO models (23, 24) delete exon 2, leaving intact an allele that produces a large N-terminal fragment of 517 amino acids (58% of the full-length protein). It is a formal possibility that the exon 2 SCARKO models may not represent the true null phenotype. To overcome these potential complications in relation to interpreting the SCTJ phenotypes, we created a new conditional allele of Ar (Artm2Reb) by flanking exon 1 with direct repeats of LoxP sites in 129S1/SvImJ ES cells (Supplemental Figure 2A). To remove any influence of the NeoR gene on the Ar locus, we excised the NeoR cassette from a properly targeted Artm2Reb recombinant clone by transient expression of FLP recombinase to ultimately produce ES cell clones harboring the conditional, nonhypomorphic Artm2.1Reb allele (Supplemental Figure 2A).

We conditionally deleted exon 1 specifically from Sertoli cells by mating Artm2.1Reb (referred to herein as Artm2.1) females with Tg(Amh-Cre) males (referred to herein as SCARKOtm2.1). PCR genotyping confirmed the loss of 5′ and 3′ LoxP sites and the generation of the novel genomic rearrangement predicted from a post-Cre recombination event at the Ar locus (Supplemental Figure 2B). Immunostaining with an anti-AR antibody directed at the N terminus showed a complete absence of signal in SCARKOtm2.1 Sertoli cells, whereas other AR-expressing cell types, such as Leydig and myoid epithelial cells, were unaffected (Supplemental Figure 2C). Similar to other SCARKO genetic models with conditional ablation of more 3′ Ar exons, SCARKOtm2.1 mice showed a block in meiosis (Supplemental Figure 2D). Taken together, these data show that the Artm2.1 allele can be used to conditionally delete Ar exon 1 sequences to produce a complete genetic loss-of-function mutation.

Stage-specific defects in tight junction architecture in SCARKO mice

SCARKOtm1 mice display SCTJ barrier defects and a complete lack of CLDN3 from SCTJs marked by CLDN11 (16, 25). To ensure that the Artm2.1 allele, in the SCARKOtm2.1 model, recapitulated the SCTJ defects observed in SCARKOtm1 and other Sertoli cell AR depletion models, we analyzed SCARKOtm2.1 mutants for SCTJ organization.

Confocal imaging of whole-mount seminiferous tubules using CLDN11 as a marker for the SCTJs revealed stretches of severely disorganized SCTJs in SCARKOtm2.1 mutants interspersed with intact stretches of tight junctions (Supplemental Figure 2E). 3-D confocal imaging revealed preleptotene spermatocytes enclosed in incomplete SCTJ compartments, indicating a potential breach in barrier function (Supplemental Movie 1 and Supplemental Movie 2).

To determine whether the absence of germ cells affects tight junction architecture and perhaps explains the SCTJ defects in SCARKO mice, we performed confocal imaging of SCTJs in KitW/Wv mice, which are devoid of meiotic and postmeiotic germ cells (37, 38). In contrast to SCARKO mutants, we never observed regions of tight junction discontinuity in W/Wv testis (Supplemental Figure 2F).

We next assessed whether the macroscopic SCTJ abnormalities correlated with functional defects in tight junctions in SCARKOtm1 and SCARKOtm2 mutants, particularly during the time of SCTJ remodeling. Because demarcation of stages in SCARKOtm2 mutants is not obvious, we used STRA8 to identify stages with transmigrating spermatocytes (39). We then used immunohistochemical analysis to assay for the presence of serum albumin in the lumen of STRA8-positive tubules. In normal tubules, serum albumin epitopes are excluded from the adluminal compartment, whereas they are detected in the adluminal compartment when SCTJ barrier function is compromised (40). Immunohistochemical analysis revealed the presence of serum albumin in both STRA8-positive and -negative tubules in SCARKOtm1 and SCARKOtm2.1 mice (Supplemental Figure 3B). We also used the albumin detection method to look at the functional integrity in KitW/Wv mutants. Surprisingly, albumin was readily detected in the adluminal compartment in KitW/Wv mutants (Supplemental Figure 3B). We conclude that in both SCARKO models, Artm1 and Artm2.1, SCTJ remodeling is similarly impaired. In addition, despite robust CLDN11 staining, the SCTJs in KitW/Wv mutants are permeable to serum albumin.

Deregulation of other SCTJ components in SCARKO and Cldn3−/− testes

Because the in vivo loss of CLDN3 failed to phenocopy the SCTJ defects observed in SCARKOtm2.1 mice, we hypothesized that other tight junction proteins could be acting in a manner redundant to that of CLDN3 or compensating for its absence. We first performed real-time qPCR on RNA from control testes to determine the other claudins and tight junction components that are normally expressed in the testis.

Of the 26 known claudin genes, we detected abundant transcript levels for several genes previously not described, including Cldn4, Cldn5, Cldn8, Cldn13, Cldn15, Cldn25, Cldn26, and TJP2iso3 (Supplemental Figure 4A). To validate the real-time qPCR data, we performed immunohistochemical analysis on tissue sections to detect protein localization of some of the abundant transcripts. CLDN15 showed a typical endothelial tight junction–staining pattern and was detected in cross sections of mouse intestinal villi but was absent from the testicular SCTJs, whereas CLDN13 showed typical SCTJ localization (Supplemental Figure 4B–D).

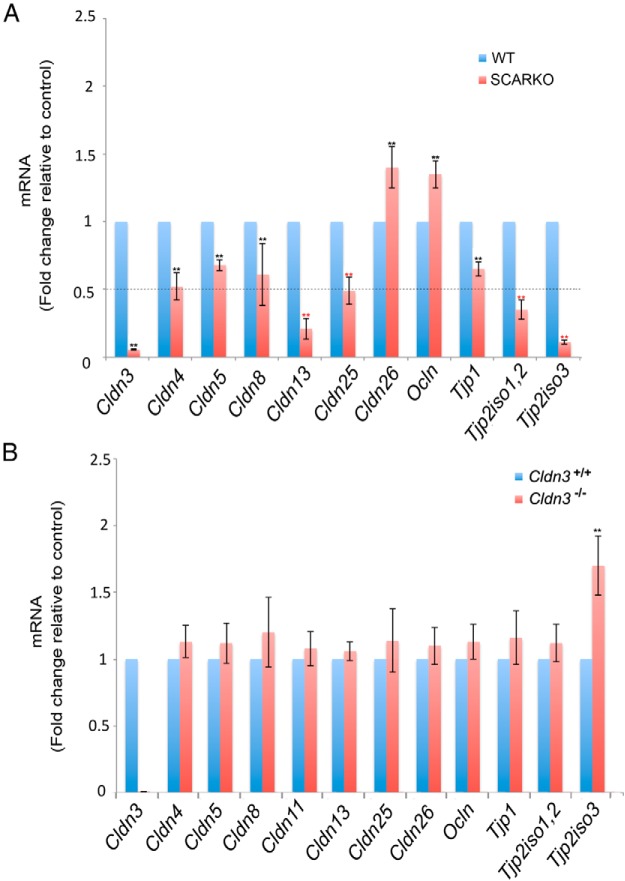

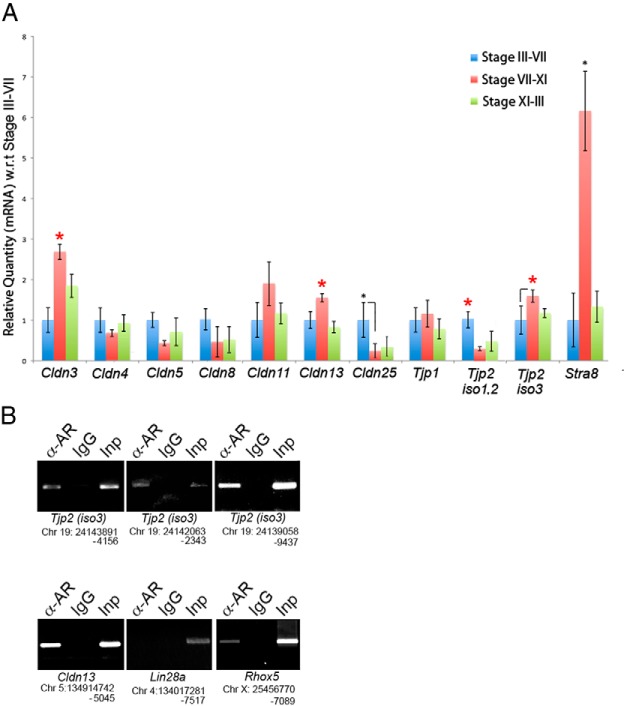

We then asked whether any of the tight junction transcripts, besides Cldn3, were altered in SCARKOtm2.1 mutants but not in Cldn3−/− mutants. We speculated that such tight junction components could be masking a phenotype in Cldn3−/− mice. Because the transcript levels of Cldn11 were not altered in SCARKO mutants in comparison with controls, it was used as a normalizer for the real-time qPCR experiments (Supplemental Figure 4E). Of the claudins and other tight junction components that are expressed in the testis, Cldn3, Cldn13, Cldn25, Tjp2iso1,2, and Tjp2iso3 transcripts were significantly diminished (>50%) in SCARKOtm2.1 testes (Figure 3A). In addition, transcript levels of Cldn4, Cldn5, and Cldn8 were reduced, although not to the magnitude of the above genes. Interestingly, SCARKO mutants had increased levels of Cldn26 and occludin (Ocln) transcripts (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Misregulation of TJP–encoding genes in SCARKO and Cldn3−/− testes. A, Transcript levels of abundant tight junction components were assessed by RT-qPCR analysis from adult control and SCARKO mice. Transcript levels were normalized to Cldn11 and the fold change in mRNA was calculated relative to that of control samples. A >50% reduction in transcripts of Cldn3, Cldn13, Cldn25, Tjp2iso1,2, and Tjp2iso3 was observed in SCARKO testes, whereas Ocln and Cldn26 transcripts were increased. Error bars represent SEM. n = 4. *, P ≤ .05. B, RT-qPCR analysis of abundant tight junction transcripts from adult testes of Cldn3−/− mice and littermate controls show a significant increase in Tjp2iso3 transcript levels, whereas other claudin and tight junction–related transcripts are unaltered. Transcript levels were normalized to actin. Error bars represent SEM. n = 4. *, P ≤ .05. WT, wild-type.

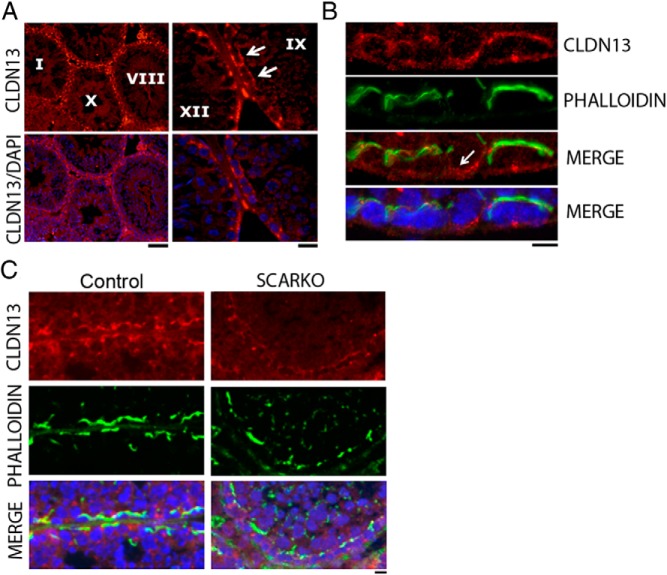

Because of the magnitude of the down-regulation of Cldn13, we further validated CLDN13 as a novel SCTJ constituent by immunohistochemical analysis of testis cross sections. Similar to CLDN11, CLDN13 is localized to SCTJs in all stages of the seminiferous cycle (Figure 4A). Colocalization studies with phalloidin revealed its presence at SCTJs; however, CLDN13 staining extended beyond phalloidin staining at certain regions, suggesting its presence in the Sertoli cell or germ cell cytoplasm in the basal compartment (Figure 4B, white arrow). Immunohistochemical studies using CLDN13 antibodies on testis sections from SCARKOtm2.1 mice showed reduced levels of CLDN13 at SCTJs compared with those of control mice (Figure 4C). Unlike in SCARKOtm2 testes, Cldn13 continues to be expressed at high levels in Cldn3−/− mice (Figure 3B).

Figure 4.

CLDN13 localizes to SCTJs and is reduced in AR-deficient Sertoli cells. A, Immunofluorescence detection of CLDN13 (red) and DNA (DAPI; blue) on adult testis cross sections. A typical basal SCTJ-type staining pattern was observed for CLDN13 in all stages. Scale bar corresponds to 20 μm. The right panel confirms presence of CLDN13 in stage IX tubules (white arrow). Scale bar corresponds to 10 μm. B, Immunofluorescence detection of CLDN13 (red), phalloidin (green), and DNA (DAPI; blue) on adult testis cross sections. CLDN13 colocalizes with phalloidin at tight junctions and at subcellular regions not associated with tight junction structures (arrow). Scale bar corresponds to 5 μm. C, Immunofluorescence detection of CLDN13 (red), phalloidin (green), and DNA (DAPI; blue) on adult testis cross sections from control and SCARKO mice. CLDN13 levels were reduced in mutant SCTJs, as identified by phalloidin staining. Scale bar corresponds to 10 μm.

Altered expression of TJP2iso3

In addition to the misregulation of several claudin genes in SCARKOtm2.1 testes, we observed a significant down-regulation of other tight junction components. As in other SCARKO models, we observed reduced Tjp1 expression (Figure 3A) (27). Furthermore, we identified reduced expression levels of Tjp2 transcripts in SCARKOtm2.1 testes, including a ∼7-fold reduction of Tjp2iso3 transcript, which encodes a poorly characterized truncated isoform of Tjp2 of unknown function (Figure 3A). Of all these tight junction–encoding genes, only Tjp2iso3 was misregulated in Cldn3−/− testes. Interestingly, in contrast to SCARKOtm2.1 testes, Cldn3−/− mice have an increased expression level of Tjp2iso3 (Figure 3B).

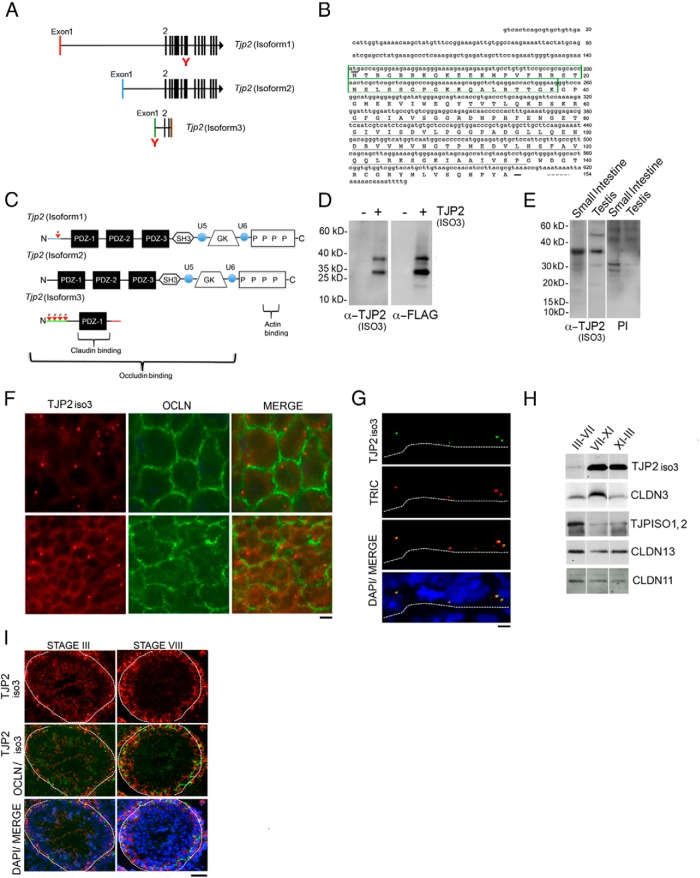

Tjp2iso3 was originally identified as a RIKEN clone (RNA accession no. AK076689.1) using the cap-trapper method to enrich for testis RNA molecules with a 7-methylguanine cap (41, 42). We performed 5′ and 3′ RACE using a common primer sequence and confirmed that the previously reported sequence encoded a complete cDNA. A polyadenylation signal (AATAAA) and a translational stop codon in addition to a canonical translational start site were mapped at the 3′ and 5′ ends of the sequence, respectively. In contrast to the well-described longer 1190- and 1167-amino acid Tjp2iso1 and Tip2iso2, respectively, which contain exons 2 to 23, Tjp2iso3 shares exons 2 to 4 but transcriptionally terminates after exon 4. All 3 Tjp2 transcript isoforms have disparate exon 1 sequences, suggesting alternate promoter usage as observed for the two human TJP2 isoforms (43, 44) (Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

TJP2iso3, a truncated isoform of TJP2, is present in the cytosol of germ cells and Sertoli cells and also accumulates at tricellular SCTJs. A, Tjp2 exons are indicated as vertical bars. All 3 isoforms have unique first exons, indicated in red, blue, and green for Tjp2iso1, Tjp2iso2, and Tjp2iso3, respectively. Exons 2, 3, and part of exon 4 are common to all 3 isoforms. The orange bar represents the unique region of exon 4 in Tjp2iso3. B, Nucleic acid sequence and inferred protein sequence derived from Tjp2iso3. The unique amino-terminal sequence contains multiple putative PKA and PKC phosphorylation sites predicted by the NetPhos server (boxed in green). The translational start and stop codons are underlined in bold and the poly(A) signal (AATAAA) is marked with a dashed line. The tight junction binding PDZ-1 domain is underlined in black. C, Comparison of protein domains derived from Tjp2 transcript isoforms. TJP2 proteins link tight junctions to peripheral cytoplasmic proteins. Tight junction association at the cell surface occurs via the PDZ domain, whereas interactions with the actin cytoskeleton are mediated by their proline-rich carboxyl-terminal ends. The PDZ-1 domain alone can associate with the C-terminal cytoplasmic tail of claudins, whereas the PDZ-2 domain binds with TJP1 and connexins. The Src homology-3 and the membrane-associated GUK domains aid in the interactions with the cytoskeletal components such as Ras, Srk kinases, and microtubule-associated proteins. The variable domains termed U (unique) 5 and U6 modulate the specificity of these interactions. The smaller Tjp2iso3 contains the PDZ-1 domain and probably retains its ability to associate with claudins at the tight junctions but lacks domains required for association with cytoskeletal components. D, MDCK cells were stably transfected with the FLAG-TJP2iso3 cDNA or control vector. Whole-cell lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis with anti-FLAG or anti-TJP2iso3 antibodies. The newly generated TJP2iso3 antibody specifically detected the FLAG-TJP2iso3 protein. E, Analysis of endogenous TJP2iso3 in intestinal and testicular tissues by immunoblot analysis using anti-TJP2iso3 antibody or preimmune serum. F, Longitudinal images of two different regions of a whole seminiferous tubule immunostained for TJP2iso3 (red) and occludin (green). All tubule regions showed a punctate staining, whereas others revealed an additional diffuse cytoplasmic staining pattern. Scale bar corresponds to 5 μm. G, Simultaneous detection of tricellulin (red) and FITC-TJP2iso3 (green). The basal lamina of the tubule is outlined with a white dotted line. Scale bar corresponds to 5 μm. H, Immunoblot analysis of tight junction components in extracts from stage dissected seminiferous tubule fragments. TJP2iso3 and CLDN3 show higher protein levels in stages VII to IX, whereas TJP2iso1,2 levels are greater in stages III to VII. I, Immunofluorescence detection of TJP2iso3 (red) and occludin (green) in 8-week-old adult testis cross sections. DAPI (blue) counterstaining was used to identify stages (III and VIII). Scale bar corresponds to 20 μm.

The TJPs are multidomain polypeptides containing 3 PSD-95/discs-large/zonula occludens-1 (PDZ) domains, a Src homology-3 domain, and a region of homology to guanylate kinase (GUK) domain at their NH2-terminal region, followed by a short COOH terminus that harbors an acidic and proline-rich domain. The PDZ-1 domain alone can associate with the C-terminal cytoplasmic tail of claudins, whereas the PDZ-2 domain binds TJP1 and connexins (45). Notably, the Tjp2iso3 transcript is predicted to encode a putative 154-amino acid protein with an estimated molecular mass of 16.8 kDa and contain a single PDZ-1 domain (Figure 5, B and C). Unlike the other TJP2 isoforms, the unique exon 1 sequence of Tjp2iso3 is predicted to produce an amino terminus harboring multiple putative protein kinase A (PKA) and protein kinase C (PKC) phosphorylation sites (Figure 5, B and C).

To further characterize TJP2iso3, we assessed its expression and subcellular localization. We generated a polyclonal rabbit antibody against the unique N-terminal peptide sequence (SGPGKKQALRTTGK) present in exon 1 of TJP2iso3. To validate the antibody, the mouse TJP2iso3 cDNA was subcloned in-frame into a C-terminal FLAG epitope-tagged expression vector and transfected into MDCK cells. Both affinity-purified anti-TJP2iso3 and anti-FLAG antibodies detected protein species at identical molecular masses in cell extracts, confirming the specificity of the newly generated antibody (Figure 5D). Interestingly, the 3xFLAG-TJP2iso3 predicted to migrate at 19.66 kDa (16.8 kDa of TJP2iso3 and 2.86 kDa of the 3xFLAG epitope) revealed an anomalous migration pattern on SDS-PAGE. In addition, both antibodies detected a 35- to 40-kDa species, possibly revealing an SDS-resistant dimeric form (approximate molecular mass ∼39 kDa) of the protein (Figure 5D). The lower band, however, migrated at a molecular mass that was higher than predicted. This band is not likely to be a degradation product of the dimeric form of TJP2iso3 because it was recognized with both N-terminal (ie, anti-TJP2iso3) and C-terminal (ie, anti-FLAG) antibodies. Thus, the lower band probably reflects an anomalous migration of the monomeric form of TJP2iso3 on SDS-PAGE (Figure 5D). In endogenous tissue lysates from intestine and testis, the TJP2iso3 antibody detected only the higher form, as observed in transfection experiments. The lower band was absent in endogenous lysates (Figure 5E).

Next, we assessed the subcellular localization of endogenous TJP2iso3. Double immunofluorescence staining of whole-mount seminiferous tubules of adult mice with TJP2iso3 and occludin antibodies revealed prominent TJP2iso3 punctate foci proximal to the crossing points of SCTJ strands, as marked by occludin (Figure 5F). The punctate TJP2iso3 expression colocalized with tricellulin, a marker of tricellular junctions that are formed at points of contact between 3 epithelial cells (Figure 5G) (46–49).

To determine whether specific stages of the seminiferous cycle have elevated TJP2iso3 levels, we extracted protein from stage-selected seminiferous tubules using the transillumination microdissection technique. Immunoblots with PAGE resolved proteins from stage-dissected tubules revealed elevated levels of TJP2iso3 protein in stage VIII through stage II tubules (Figure 5H). Immunostaining stage VIII and stage III in seminiferous tubule cross sections with TJP2iso3 and occludin antibodies were consistent with Western blot data, revealing stage VIII tubules with an enhanced cytoplasmic TJP2iso3 signal (Figure 5I).

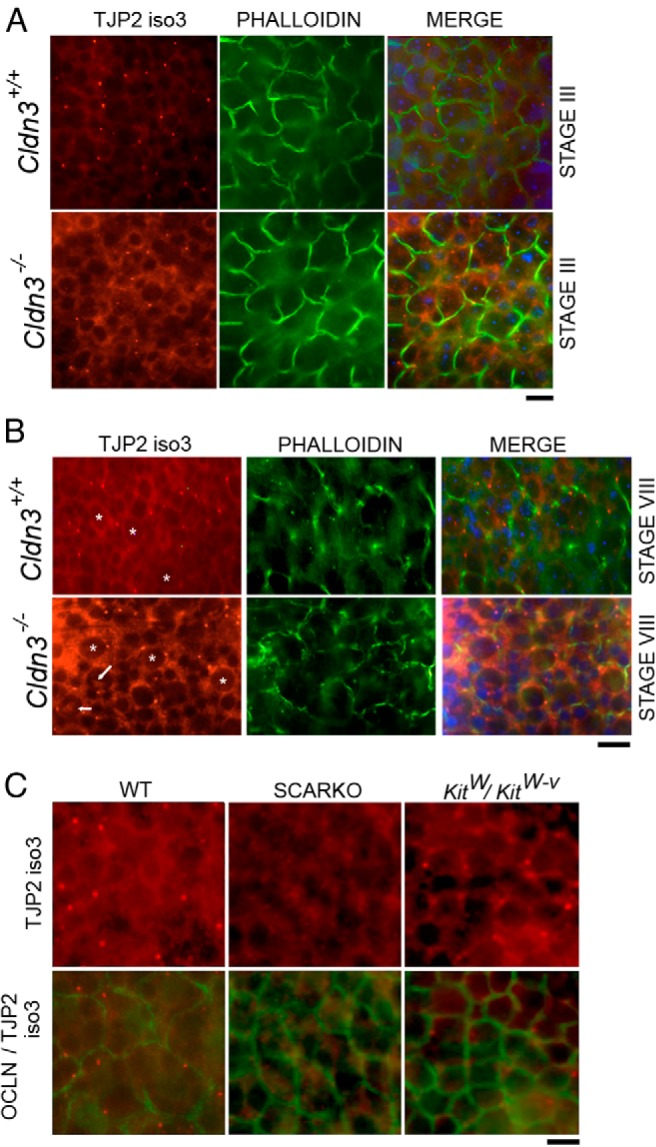

TJP2iso3 protein levels are elevated in Cldn3−/− mutants and significantly diminished in SCARKO mice

Gene expression profiling of SCARKOtm2.1 and Cldn3−/− mutants using RT-qPCR analysis showed reciprocal changes in testicular Tjp2iso3 transcript levels. We sought to use our new isoform-specific antibody to assess TJP2iso3 protein levels in these different mutant mouse models. Consistent with our RNA transcript findings, whole-mount immunostaining of testis tubules with the TJP2iso3-specific antibody confirmed an increase in protein levels in Cldn3−/− mutant mice (Figure 6, A and B). Furthermore, a characteristic nucleolar staining pattern was observed in multiple Sertoli cell nuclei in these mice. To visualize the Sertoli cell nuclei, a plane slightly basal to the tight junctions was imaged as revealed by the discontinuous tight junction–staining pattern (denoted with arrows in Figure 6B). Next, we determined whether the decrease in the Tjp2iso3 transcript levels observed in SCARKO mice correlated with a decrease in protein levels. Whole-mount immunostaining with TJP2iso3 and occludin antibodies was performed. We observed an overall reduction in TJP2iso3 staining in SCARKOtm2.1 seminiferous tubules. Notably, a decrease in the punctate staining pattern of TJP2iso3 in SCARKOtm2.1 mutants was observed (Figure 6C). To determine whether this observed lack of staining at the tricellular junctions was due to the absence of germ cells, we assayed for the presence of TJP2iso3 in KitW/Wv mutant mice (38). KitW/Wv mutant tubules maintained distinct punctate TJP2iso3 localization at tricellular junctions, thus confirming that the defect observed in SCARKOtm2.1 mice was an intrinsic abnormality specific to the mouse model (Figure 6C). Taken together, these data suggest that SCARKOtm2.1 mice have altered tricellular tight junction composition that may affect SCTJ barrier integrity.

Figure 6.

TJP2iso3 protein levels are enhanced in Cldn3−/− mutants and diminished in SCARKO mutants. A, Immunofluorescence detection of TJP2iso3 (red) and phalloidin (green) on whole-mount seminiferous tubules from control and Cldn3−/− mice (DAPI = blue). The diffuse cytosolic TJP2iso3 distribution in Cldn3−/− mutants was enhanced in stage III, whereas the punctate bodies were unaltered. B, Fluorescent images of seminiferous tubules at stage VIII showing TJP2iso3 (red) and phalloidin (green) localization, emphasizing the marked increase in cytoplasmic staining in Cldn3−/− mutant Sertoli cells in comparison with that in controls. Sertoli cells were identified by the bright heterochromatic DAPI foci (asterisks). Nucleolar staining (arrows) of TJP2iso3 was observed in many Sertoli cells in Cldn3−/− mutant mice. The images were obtained at an optical plane (as indicated by a discontinuous tight junction pattern) that clearly displays the Sertoli cell cytoplasm. C, Fluorescence staining of seminiferous tubules with TJP2iso3 (red) and occludin (green) showed a significant reduction in punctate staining of TJP2iso3 in SCARKO mice, whereas the punctate TJP2iso3 staining is still present in KitW/Wv mutant tubules. WT, wild-type.

Cytoplasmic and nuclear localization of TJP2

In addition to reduced TJP2iso3 levels in SCARKOtm2.1 mutants, we observed reduced levels of Tjp2iso1 and Tjp2iso2 transcripts. To confirm that the TJP2iso1 and TJPiso2 protein isoforms were also reduced, we performed whole-mount immunostaining using a pan-TJP2iso1/2 antibody. Analyses of control tubules revealed that TJP2 levels and subcellular localization are dynamic throughout the seminiferous epithelial cycle. An increase in TJP2 staining was observed in the SCTJs from stages III to V with stage V tubules showing cytoplasmic localization of TJP2 in addition to its tight junction association (Figure 7A). Prominent tight junction staining of TJP2 was observed in stage IX, whereas XI tubules showed TJP2 protein in the nucleus and the tight junctions (Figure 7A). In contrast, we never observed nuclear staining of TJP2 in SCARKOtm2.1 mutants (Figure 7B, arrows denote Sertoli cell nuclei that can be identified by their bright heterochromatic DAPI foci). Consistent with a reduction in Tjp2 transcripts in SCARKOtm2.1 mutants, TJP2 levels were reduced in regions of the seminiferous tubule with damaged tight junctions, marked by phalloidin (Figure 7C).

Figure 7.

TJP2 levels and spatial localization change during the seminiferous cycle and in SCARKO mice. A, Immunofluorescence detection of TJP2 (red to yellow heat map) and phalloidin (gray) by whole-mount immunostaining and 3-D confocal microscopy show that Sertoli cells have TJP2 in tight junctions throughout the seminiferous cycle (stages III, V, IX, and XI). Stage V Sertoli cells show elevated cytoplasmic TJP2 levels, whereas stage XI Sertoli cells have nuclear localized TJP2. The TJP2 antibody recognizes TJP2iso1 and TJP2iso2 but not TJP2iso3. Scale bar corresponds to 10 μm. B, SCARKO tubules have reduced TJP2 nuclear staining (red to yellow heat map). White arrows in the right panel denote Sertoli cell nuclei, displaying the characteristic heterochromatic pattern. Arrows in the left panel depict the position of the nuclei marked by DAPI (blue to green heat map). Scale bar corresponds to 10 μm. C, Disorganized tight junctions (marked by phalloidin, green) in SCARKO tubules show a modest reduction in TJP2. The white dotted line outlines a tight junction surrounding a single Sertoli cell. Scale bar corresponds to 10 μm. WT, wild-type.

Androgen responsive element (ARE) binding sites in Cldn13 and Tjp2iso3 are bound by AR in vivo

In Sertoli cells, transcripts that are predominantly regulated by AR would be predicted to change during stages of the seminiferous epithelium that have elevated AR protein expression. Tight junction transcripts reduced in SCARKOtm2.1 testes represent possible direct AR-regulated target genes. We determined whether transcripts that were reduced in SCARKOtm2.1 testes were enriched in stages VII to XI, a developmental phase in the seminiferous epithelial cycle that exhibits induction of key AR effector molecules (50). To accomplish this, we used transillumination microdissection of control seminiferous tubules to isolate RNA from 3 sets of tubules: stages III to VII, VII to XI, and XI to III (51). As expected, we observed significant enrichment of Cldn3 transcripts in stages VII to XI, which have abundant AR levels as well as extensive SCTJ remodeling (Figure 8A). Similar to Cldn3 expression, Cldn13 was also significantly enriched during the remodeling stages. In addition, Tjp2iso3 was enriched in stages VII to XI, whereas the “longer” Tjp2 isoforms (1 and 2) were enriched in stage III to VII tubules (Figure 8A). The increased transcript levels of these genes during the SCTJ remodeling phase and their misregulation in SCARKOtm2.1 mutant testes suggest that they could be direct downstream effectors of AR in mediating SCTJ remodeling.

Figure 8.

Transcript analysis of TJP–encoding genes throughout the seminiferous tubule cycle. A, RT-qPCR analysis of tight junction components performed on total RNA obtained from different seminiferous tubules stages as identified by the transillumination technique. Stra8, a gene expressed at high levels in differentiating spermatocytes during stages VII to XI was used as a positive control to validate the tubule stages isolated using transillumination. Error bars denote SEM. n = 3. *, P ≤ .05. Transcript abundance was plotted relative to stage III to VII for each mRNA. Both TJP2iso3 and Cldn13 transcripts were enriched in stages VII to XI, whereas TJP2iso1 and TJPiso2 were enriched in stages III to VII. B, Testes from 8-week-old male mice were subjected to ChIP with nonimmunized rabbit IgG (negative control) and anti-AR antibodies. The PCR reactions were performed with primer pairs spanning putative AREs in the depicted genomic regions of Tjp2iso3, Cldn13, Lin28a (negative control), and Rhox5 (positive control). (Assembly of mouse genome used for design of primer pairs: December 2011, GRCm38/mm10.)

To determine whether Tjp2iso3 and Cldn13 are direct targets of AR, we performed ChIP assays on 8-week-old adult testes. Tjp2iso3 and Cldn13 genes contain several putative ARE sequences; primarily the conserved TGTTCT motif. AR binding sites were specifically enriched in 3 genomic regions in the Tjp2iso3 locus and one in the Cldn13 locus (Figure 8B). Lin28a was used a negative control and Rhox5, a direct AR target gene in Sertoli cells, was used as a positive control for the ChIP assay (32). Taken together, these results suggest that AR directly regulates the expression of Tjp2iso3 and Cldn13 in the seminiferous tubules.

Discussion

Tight junction remodeling during the cycle of the seminiferous tubule epithelium is necessary for the translocation of preleptotene spermatocytes from the basal to the adluminal compartment. The lack of androgen signaling in Sertoli cells results in a block in the differentiation of pachytene spermatocytes and defects in tight junction remodeling, although preleptotene spermatocytes do translocate from the basal to the adluminal compartment in SCARKO mutants. A goal of this work was to determine the role of Cldn3, a direct transcriptional target of the androgen receptor in Sertoli cells, in tight junction remodeling.

We found that mutation of Cldn3 does not recapitulate the SCTJ defects observed in SCARKOtm1 and SCARKOtm2.1 mutants (16, 27). Furthermore, Cldn3−/− mice are fertile and show no SCTJ structural defects, even during the stages of SCTJ remodeling when preleptotene spermatocytes translocate from the basal to the adluminal compartment. Consistent with the above observations, Cldn3−/− SCTJs were impermeable to lanthanum tracers, a gold standard in assessing the in vivo integrity of SCTJs.

To explore the possibility that other tight junction molecules might be regulated by AR, we intensively interrogated SCARKOtm2.1 mutants for dysregulation of other tight junction molecules. In doing so, we confirmed that several other tight junction molecules are altered in SCARKOtm2.1 mice (eg, Tjp1, Tjp2iso1, and Tjp2iso2) and discovered several new tight junction molecules (eg, Cldn13, Cldn25, and Tjp2iso3) that are down-regulated in SCARKOtm2.1 mutants. ChIP data suggest that, along with Cldn3, Cldn13 and Tjp2iso3 are likely direct targets of AR signaling in Sertoli cells. Like CLDN11, CLDN13 is expressed throughout the seminiferous cycle and is localized to bicellular tight junctions. Unexpectedly, TJP2iso3 colocalizes with tricellulin, a component of tricellular junctions. Tjp2iso3 is also up-regulated in Cldn3−/− mutants suggesting that its abundance is coupled with Cldn3 function. Our data indicate that the tight junction defects present in SCARKOtm2.1 mice result from a disruption of a network of tight junction molecules.

Possible functions for TJP2iso3

CLDN3 expression in newly formed SCTJs is conserved in humans (Supplemental Figure 5) and mice, an evolutionary divergence of ∼100 million years (52). This expression conservation and the absence of a histological or functional SCTJ phenotype in the Cldn3−/− testes suggest that redundant mechanisms could account for the absence of an observable defect in Cldn3 mutants.

In our efforts to detect changes in tight junction protein components that could compensate for the absence of CLDN3, we searched for other claudins and tight junction–associated proteins whose expression is altered in Cldn3−/− mutants. We identified an isoform of Tjp2, Tjp2iso3, which is significantly up-regulated in Cldn3−/− mutants. Like Cldn3, its transcript and protein levels peaked in stages of SCTJ remodeling, and it is 7-fold less abundant in SCARKOtm2.1 mice than in controls. At all stages of the spermatogenic cycle, TJP2iso3 colocalizes with tricellulin, a component of tricellular junctions. In addition to the junction localization, prominent cytoplasmic levels increase in stage VIII.

The Tjp2iso3 protein product exhibits several features that suggest it is involved in SCTJ remodeling. Tjp2iso3 uses a different transcriptional start compared with the 2 frequently described isoforms (Tjp2iso1 and Tjp2iso2) and transcriptionally terminates after sequences that encode the PDZ-1 domain. TJP2iso3 contains a short N-terminal peptide sequence harboring multiple putative PKA and PKC phosphorylation sites followed by the single PDZ-1 protein-protein interaction domain. The longer TJP2iso1 and TJP2iso2 isoforms act as cross-linkers between tight junctions and the intracellular actin filaments via the carboxyl terminal region. This contrasts with TJP2iso3, which lacks the protein cross-linking domains. Interestingly, C-terminal truncated TJP1 molecules, containing only the N-terminal PDZ domains, can regulate the clustering of CLDN3 in vitro (53). Like the TJP1 truncation mutants, which are capable of binding to claudins (54), the naturally occurring TJP2iso3 contains a single PDZ-1 domain, suggesting that it too could affect tight junction remodeling.

How could the loss of CLDN3 lead to a specific increase in Tjp2iso3 transcript levels? TJP proteins can localize to the nucleus and regulate transcription (55, 56). Interestingly, we observed a stage-dependent localization of TJP2iso1 and TJP2iso2 proteins to the nucleus. This subcellular distribution is absent in SCARKOtm2.1 mutants, whereas Cldn3−/− mutants show an increase in nuclear staining. Considering the molecular features of the TJP1 truncation mutant and the fact that TJP functions in transcription, perhaps TJP2iso3 facilitates the clustering of claudins during the remodeling stage, yet in the absence of CLDN3, free TJP2iso3 could transcriptionally enhance a feed-forward loop, resulting in the production of more TJP2iso3. This in turn would facilitate the clustering of other claudins into the newly forming SCTJ in the absence of CLDN3.

It is possible that the cytoplasmic pool of TJP2iso3 observed in Cldn3−/− mutants could compensate for a noncanonical CLDN3 function. Thus far we have primarily envisaged CLDN3 as a tight junction protein based on its localization in new tight junctions at stage IX. However, the peak of CLDN3 protein expression occurs in stage VIII, similar to that for TJP2iso3, in which it is not yet incorporated into new tight junctions and instead is distributed across the basal surface of Sertoli cells (5). Importantly, contrary to many claudins whose levels diminish in metastatic cancers due to loss of cell polarity, Cldn3 levels are found to be elevated (57–60). In addition, overexpression of CLDN3 in in vitro cultured ovarian epithelial cells causes increased cell invasion and motility, and small interfering RNA–mediated Cldn3 gene silencing reduces ovarian tumor growth and metastasis (61, 62). Given these findings, it is possible that CLDN3 plays a role in cellular remodeling by promoting cytoplasmic projections under preleptotene spermatocytes in stage VIII to establish Sertoli cell contacts before initiation of new tight junction formation. In support of this hypothesis, overexpression of truncated TJP1 molecules, containing only the N-terminal PDZ domains, can induce an epithelial to mesenchymal transition that occurs before metastasis and involves complex cytoskeletal rearrangements (63). Concordant with these ideas, 3-D rendering of the tight junction images obtained from SCARKO mutants showed the presence of incomplete compartments enclosing premeiotic germ cells. These could be a consequence of reduced levels of both CLDN3 and TJP2iso3 in SCARKO mutants.

Tight junction defects in SCARKO mutants are probably due to the dysregulation of multiple tight junction components

Of the known 26 known claudins, transcripts for 9 of them can be detected in the testis (Cldn3, Cldn4, Cldn5, Cldn8, Cldn11, Cldn13, Cldn15, Cldn25, and Cldn26). Although testis transcripts for some of these have been reported previously (60), protein expression has only been reported for CLDN3, CLDN5, and CLDN11. This study adds CLDN13 to that growing list of claudins that are constituents of SCTJs. Cldn13 is tightly linked with Cldn4 on mouse chromosome 5 and represents a rodent-specific paralog. Intriguingly, the Cldn13 locus contains an AR-occupied consensus ARE and its transcript levels are reduced in the SCARKOtm2.1 testis and elevated in the stages of the spermatogenic cycle associated with maximum AR signaling. Mutational analyses of Cldn13, on its own and in a Cldn3−/−-deficient genetic background, will provide a valuable in vivo test of separate and overlapping functions for these two claudins. If Cldn13 function is redundant with Cldn3, it may explain the lack of male fertility defects in Cldn3-null mice. On the contrary, loss of Cldn3 in humans may result in severe fertility defects due to absence of compensation by Cldn13.

In addition to a >2-fold reduction of Cldn3 and Cldn13 expression in SCARKOtm2.1 mice, we also found statistically elevated levels of transcripts for Ocln and Cldn26, and reduced levels of Tjp1, Tjp2iso1, Tjp2iso2, and Tjp2iso3. A decrease in Tjp1 has been reported previously in a different SCARKO model (26). TJP1 and TJP2 are in the membrane-associated GUK family of proteins and link the transmembrane tight junction proteins to the cell cytoskeleton and signaling pathways, thus mediating tight junction structure and function (55, 64, 65). In vivo studies in the mouse have revealed the requirement for TJP2 in maintaining the BTB (19). On the other hand, Ocln −/− mice have normal-appearing tight junctions and are initially fertile, although at about 1 year of age they lose germ cells and undergo testicular atrophy for unknown reasons (66). Interestingly, cell culture studies illustrate role of occludin in aiding transepithelial migration of neutrophils across tight junctions, a process analogous to preleptotene cyst migration (67). Occludin has also been shown to aid formation of tricellular junctions (68). Clearly, we are only at the beginning of acquiring a full understanding of tight junction dynamics in Sertoli cells.

Additional material

Supplementary data supplied by authors.

Acknowledgments

We thank P. Finger and Ted Duffy at The Jackson Laboratory Electron Microscopy and Flow Cytometry Services for assistance with experiments and also Andrea Dearth, Adrienne Burton, and Dr Beth Snyder for providing critical help with mouse experiments.

This work was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health as part of the Specialized Cooperative Centers Program in Reproduction Research (Grant HD12629 to R.E.B.) and by the National Cancer Institute (Grant CA34196) in support of The Jackson Laboratories shared services. P.C. was supported by the National Institutes of Health (Training Grant HD07065). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the article.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- AR

- androgen receptor

- ARE

- androgen responsive element

- BTB

- blood-testis barrier

- CLDN

- claudin

- CMV

- cytomegalovirus

- 3-D

- three-dimensional

- DAPI

- 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- ES

- embryonic stem

- FITC

- fluorescein isothiocyanate

- FRT

- Flp-recombinase target

- gDNA

- genomic DNA

- GUK

- guanylate kinase

- MDCK

- Madin-Darby canine kidney

- pBS

- pBluescript

- PDZ

- PSD-95/discs-large/Zonula occludens-1

- PKA

- protein kinase A

- PKC

- protein kinase C

- qPCR

- quantitative PCR

- RACE

- rapid amplification of cDNA ends

- SCARKO

- Sertoli cell androgen receptor knockout

- SCTJ

- Sertoli cell tight junction

- SSC

- standard saline citrate

- TJP

- tight junction protein.

References

- 1. Dym M, Fawcett DW. The blood-testis barrier in the rat and the physiological compartmentation of the seminiferous epithelium. Biol Reprod. 1970;3:308–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Russell L. Movement of spermatocytes from the basal to the adluminal compartment of the rat testis. Am J Anat. 1977;148:313–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mruk DD, Cheng CY. Sertoli-Sertoli and Sertoli-germ cell interactions and their significance in germ cell movement in the seminiferous epithelium during spermatogenesis. Endocr Rev. 2004;25:747–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tung KS, Teuscher C, Meng AL. Autoimmunity to spermatozoa and the testis. Immunol Rev. 1981;55:217–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Smith BE, Braun RE. Germ cell migration across Sertoli cell tight junctions. Science. 2012;338:798–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Furuse M, Hata M, Furuse K, et al. Claudin-based tight junctions are crucial for the mammalian epidermal barrier: a lesson from claudin-1-deficient mice. J Cell Biol. 2002;156:1099–1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gow A, Davies C, Southwood CM, et al. Deafness in Claudin 11-null mice reveals the critical contribution of basal cell tight junctions to stria vascularis function. J Neurosci. 2004;24:7051–7062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kitajiri S, Miyamoto T, Mineharu A, et al. Compartmentalization established by claudin-11-based tight junctions in stria vascularis is required for hearing through generation of endocochlear potential. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:5087–5096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ben-Yosef T, Belyantseva IA, Saunders TL, et al. Claudin 14 knockout mice, a model for autosomal recessive deafness DFNB29, are deaf due to cochlear hair cell degeneration. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:2049–2061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Miyamoto T, Morita K, Takemoto D, et al. Tight junctions in Schwann cells of peripheral myelinated axons: a lesson from claudin-19-deficient mice. J Cell Biol. 2005;169:527–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lal-Nag M, Morin PJ. The claudins. Genome Biol. 2009;10:235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Furuse M. Molecular basis of the core structure of tight junctions. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a002907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mazaud-Guittot S, Meugnier E, Pesenti S, et al. Claudin 11 deficiency in mice results in loss of the Sertoli cell epithelial phenotype in the testis. Biol Reprod. 2010;82:202–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Morrow CM, Hostetler CE, Griswold MD, et al. ETV5 is required for continuous spermatogenesis in adult mice and may mediate blood testes barrier function and testicular immune privilege. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2007;1120:144–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Morrow CM, Tyagi G, Simon L, et al. Claudin 5 expression in mouse seminiferous epithelium is dependent upon the transcription factor ets variant 5 and contributes to blood-testis barrier function. Biol Reprod. 2009;81:871–879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Meng J, Holdcraft RW, Shima JE, Griswold MD, Braun RE. Androgens regulate the permeability of the blood-testis barrier. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:16696–16700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gow A, Southwood CM, Li JS, et al. CNS myelin and Sertoli cell tight junction strands are absent in Osp/claudin-11 null mice. Cell. 1999;99:649–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nitta T, Hata M, Gotoh S, et al. Size-selective loosening of the blood-brain barrier in claudin-5-deficient mice. J Cell Biol. 2003;161:653–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Xu J, Anuar F, Ali SM, et al. Zona occludens-2 is critical for blood-testis barrier integrity and male fertility. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:4268–4277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhou Q, Nie R, Prins GS, Saunders PT, Katzenellenbogen BS, Hess RA. Localization of androgen and estrogen receptors in adult male mouse reproductive tract. J Androl. 2002;23:870–881. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bremner WJ, Millar MR, Sharpe RM, Saunders PT. Immunohistochemical localization of androgen receptors in the rat testis: evidence for stage-dependent expression and regulation by androgens. Endocrinology. 1994;135:1227–1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. O'Shaughnessy PJ, Verhoeven G, De Gendt K, Monteiro A, Abel MH. Direct action through the Sertoli cells is essential for androgen stimulation of spermatogenesis. Endocrinology. 2010;151:2343–2348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]