Abstract

Mammalian sperm must undergo a maturational process, named capacitation, in the female reproductive tract to fertilize the egg. Sperm capacitation is regulated by a cAMP/PKA pathway and involves increases in intracellular Ca2+, pH, Cl−, protein tyrosine phosphorylation, and in mouse and some other mammals a membrane potential hyperpolarization. The cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), a Cl− channel modulated by cAMP/PKA and ATP, was detected in mammalian sperm and proposed to modulate capacitation. Our whole-cell patch-clamp recordings from testicular mouse sperm now reveal a Cl− selective component to membrane current that is ATP-dependent, stimulated by cAMP, cGMP and genistein (a CFTR agonist, at low concentrations), and inhibited by DPC and CFTRinh-172, two well-known CFTR antagonists. Furthermore, the Cl− current component activated by cAMP and inhibited by CFTRinh-172 is absent in recordings on testicular sperm from mice possessing the CFTR ΔF508 loss-of-function mutation, indicating that CFTR is responsible for this component. A Cl− selective like current component displaying CFTR characteristics was also found in wild type epididymal sperm bearing the cytoplasmatic droplet. Capacitated sperm treated with CFTRinh-172 undergo a shape change, suggesting that CFTR is involved in cell volume regulation. These findings indicate that functional CFTR channels are present in mouse sperm and their biophysical properties are consistent with their proposed participation in capacitation.

Keywords: Ionic currents, CFTR, capacitation, hyperpolarization, sperm

1. INTRODUCTION

Mouse epididymal sperm need to undergo a maturational process in the female reproductive tract, named capacitation, to become competent to fertilize the female gamete and generate a new individual. This complex process involves plasma membrane reorganization, cholesterol removal, protein tyrosine phosphorylation, membrane hyperpolarization (in mouse and other species) and increases in intracellular pH (pHi), Ca2+([Ca2+]i) and Cl− ([Cl−]i) (Darszon et al., 2005; Hernandez-Gonzalez et al., 2007; Krapf et al., 2010; Santi et al., 2010; McPartlin et al., 2011). Capacitation prepares sperm to undergo a physiologically induced exocytotic reaction, known as acrosome reaction (AR) (Yanagimachi, 1994; Visconti et al., 2011), and is accompanied by the development of hyperactivated motility, an asymmetric mode of flagellar beating (Suarez and HO, 2003). Sperm protein tyrosine phosphorylation, hyperpolarization and hyperactivation depend on a cAMP/protein kinase A (PKA) pathway, where a bicarbonate (HCO3−)-dependent soluble adenylate cyclase (SACY) is a key player (Buck et al., 1999; Chen et al., 2000; Kaupp and Weyand, 2000; Esposito et al., 2004; Hess et al., 2005). HCO3− is essential for capacitation to stimulate SACY, yet how it enters sperm is not fully understood (reviewed in Salicioni et al., 2007).

In mouse sperm, the capacitation-associated hyperpolarization is thought to result from activity changes in K+ channels (Slo3 (Santi et al., 2010; Zheng et al., 2011)) and inward rectifiers (Muñoz-Garay et al., 2001; Acevedo et al., 2006), amiloride sensitive epithelial Na+ channels (ENaCs) (Hernandez-Gonzalez et al., 2006) and the cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator (CFTR) (Hernandez-Gonzalez et al., 2007; Xu et al., 2007). CFTR channels are known to modulate ENaCs (and vice versa) in several tissues (Schreiber et al., 1999; Kunzelmann et al., 2000; Berdiev et al., 2009), and evidence indicates this may occur in mouse sperm (Hernandez-Gonzalez et al., 2007; Escoffier et al., 2012). On the other hand, it is known that external Cl− is required for the capacitation-associated increase in tyrosine phosphorylation, hyperactivation, the Zona pellucida (ZP)-induced AR and fertilization (Wertheimer et al., 2008). The Cl− equilibrium potential (ECl−) for noncapacitated sperm has been estimated at~ −31 mV and ~ −24.5 mV for capacitated sperm. Furthermore, it has been shown that [Cl−]i increases during capacitation (Hernández-Gonzalez et al., 2007). Altogether, these data suggest that Cl− has an essential role in the regulation of this process (Wertheimer et al., 2008).

The CFTR channel belongs to the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter family (Riordan et al., 1989). It has two transmembrane domains (TMD1 and TMD2), each comprised of six membrane-spanning regions, two nucleotide-binding domains (NBD1 and NBD2) (Holland and Blinght, 1999; Higgins and Linton, 2004) and a regulatory (R) domain containing potential sites for phosphorylation by PKA and protein kinase C (Riordan et al., 1989; Baukrowitz et al., 1994; Hwang et al., 1994). The TMDs contribute to pore formation, while NBD and R domains control channel activity. CFTR is expressed in respiratory airways, the digestive apparatus and the reproductive tracts (Poulsen et al., 1994; Quinton, 1999). It is a Cl− channel activated by PKA (Anderson et al., 1991; Sheppard and Welsh, 1999; Li et al., 2007) and regulated by Cl−, ATP levels, membrane potential and protein-protein interactions (Schwiebert et al., 1998; Boucher, 2004, Riordan, 2005).

Certain CFTR mutations produce cystic fibrosis, an inherited autosomal recessive disease leading to progressive lung and pancreatic insufficiency, and to severe fertility reduction (Silber, 1994; Guggino and Stanton, 2006). Infertility in cystic fibrosis patients is mostly due to congenital bilateral absence of the vas deferens with resultant obstructive azoospermia (Wong, 1998). Cystic fibrosis patients producing sperm may have a specific defect in sperm-ZP penetration (Silber, 1994) and up to 50% of the sperm are dimorphic. In addition, it has been proposed that CFTR participates in spermatogenesis (Trezise et al., 1993; Gong et al., 2001). Taking into account that the frequency of CFTR heterozygosity is 2-fold higher in infertile men than in the general population, mutations in this channel may lead to male infertility (Schultz et al., 2006). However, the physiological roles of CFTR in mammalian reproductive physiology are not well understood. Immunological and pharmacological evidence has indicated the presence of CFTR channels in human and mouse sperm and their participation in capacitation (Hernandez-Gonzalez et al., 2007; Xu et al., 2007). Here we report whole-cell patch-clamp recordings from testicular mouse sperm that reveal a Cl− selective current component that is ATP-dependent and stimulated by cAMP, cGMP and genistein, a CFTR agonist (at low concentrations). This current is inhibited by diphenylamine-2-carboxylic acid (DPC) and CFTRinh-172, two well-known CFTR antagonists (Schultz et al., 1999; Zhang et al., 2000; Ma et al., 2002; Taddei et al., 2004; Caci et al., 2008). Notably, the Cl− current component activated by cAMP and inhibited by CFTRinh-172 is absent in recordings on testicular sperm from the CFTR ΔF508 loss-of-function mutant mice, showing that CFTR is responsible for this component. Furthermore, a similar current component was also found in wild type epididymal sperm bearing the cytoplasmatic droplet. These findings support the presence of functional CFTR channels in mouse sperm and are consistent with their proposed participation in capacitation. In addition, consistent with the well-known role of Cl− channels in cell volume regulation (Yeung et al., 2005), our results indicate that CFTRinh-172 causes shape changes in mouse sperm.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Dibutyryl cyclic AMP (db-cAMP), dibutyryl cyclic GMP (db-cGMP), 8-Bromo cyclic GMP (8Br-cGMP), 8-Bromo adenosine 3´,5´-cyclic monophosphate (8Br-cAMP), diphenyl-amine-2-carboxylate (DPC), genistein, n-methyl-D-glucamine (NMDG), sodium gluconate (GluNa), NMDG-metanesulphonate (NMDG-MeSO3), NMDG-gluconate (NMDG-gluconate), 3-[(3-trifluoromethyl)phenyl]-5-[(4 carboxyphenyl)methylene]-2-thioxo-4thiazolidinone (CFTRinh-172) were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Stock solutions were prepared in DMSO, except 8Br-cGMP and 8Br-cAMP that were solubilized in water, and stored at −20 °C until use. Db-cAMP, db-cGMP, 8Br-cGMP and 8Br-cAMP were prepared fresh and used at the indicated concentration. DMSO in medium was always less than 0.1% and alone had no effect on channel activity.

Mouse sperm preparations

All experimental protocols were approved by the local Animal Care and Bioethics Committee. Testicular and epididymal sperm were obtained from 3-month-old CD-1 mice as previously described (Acevedo et al., 2006; Martínez-López et al., 2011). Mice carrying the F508del Cftr mutant gene (Van Doorninck et al., 1995; French et al., 1996) and generously provided by Dr. B. J. Scholte from Erasmus MC Rotterdam, the Netherlands, were also used. The genetic background of these mice is C57Bl/6J obtained by 13 backcrosses to wt from the original 129/FVB strain (Wilke et al, 2011). Homozygous mutants were obtained by breeding heterozygous mice and fed with normal chow and acidified water ad lib. Genotyping was done by PCR as described (Van Doorninck et al., 1995).

Testicles were excised after cervical dislocation and suspended on ice-cold dissociation solution containing (in mM): 130 NaCl, 3 KCl, 10 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, 1 NaHCO3, 0.5 NaH2PO4, 5 Hepes and 10 glucose (pH 7.4). The tunica albuginea was removed and the seminiferous tubules separated using dissecting tweezers. Tubules were dispersed into individual cells and/or synplasts and testicular sperm by mechanical dispersion using Pasteur pipettes. The cells were stored at 4°C until assayed. Subsequently ~300 µl aliquots of cell suspension were dispensed into a recording chamber (1 ml total volume) and subjected to electrophysiological recording. Cauda epididymal mouse sperm were collected by placing minced cauda epididymis in Whittens medium. After 20 min the sperm suspension was washed in 10 ml of the same medium by centrifugation at 800 × g for 10 min at room temperature. Sperm were then resuspended in the indicated medium and used for electrophysiology.

Whole cell currents from mouse sperm

Whole-cell ionic currents were obtained by patch-clamping the sperm cytoplasmic droplet in testicular and epididymal sperm and analyzed as reported (Ren and Xia, 2010; Kirichok and Lishko, 2011). Recordings were performed using an Axopatch 200A patch-clamp amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) at room temperature 22°C. Pulse protocols, data capture and analysis were performed using pCLAMP software (Axon, Molecular Devices, Palo Alto, CA), Origin 7.5 (Microcal Software, Northampton MA) and Sigma Plot 10 (SYSTAT Software, Foster City). The currents were captured on-line at a sampling rate of 5–10 kHz and filtered (2–5 kHz; internal 4-pole Bessel filter) using a computer attached to a Digidata 1200 interface (Axon). Patch pipettes were pulled from borosilicate glass (Kimble®) and had resistances of 8–10 MΩ when filled with internal solution. All external and internal solutions were adjusted with sucrose to have 300 and 290 mOsm, respectively. Initial experiments were performed with a physiological extracellular solution containing (in mM): 130 NaCl, 3 KCl, 10 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, 1 NaHCO3, 0.5 NaH2PO4, 5 HEPES, 10 glucose, adjusted to pH 7.4 with NaOH. The internal solution contained (in mM): 120 CsCl, 10 CsF, 4.6 CaCl2, 10 EGTA (free Ca2+ 75 nM), 5 HEPES, adjusted to pH 7.3 with CsOH. To isolate CFTR Cl− currents, extracellular solutions contained (in mM): 145 NMDG-Cl, 2 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 10 HEPES, adjusted to pH 7.2 with NMDG or alternatively (in mM): 145 TEACl, 2 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 10 HEPES, adjusted to pH 7.2 with NMDG. The internal solution contained (in mM): 35 NMDG-Cl, 110 NMDG-gluconate, 2 CaCl2, 2 EGTA (free Ca2+ ~10 µM), 2 MgCl2, 3 ATP-Mg, 10 HEPES, adjusted to pH 6.8 with NMDG. Experiments were also carried out lowering the internal solution free Ca2+ concentration to a physiological level of ~60 nM by increasing EGTA to 5 mM or basically eliminating it using 10 mM EGTA. In these latter experiments extracellular Ca2+ was also removed (Fig. 3G, H and inset). Free Ca2+ concentration was estimated using MaxChelator software V2.00 (Chris Patton, Stanford University, USA). ATP was absent inside the patch pipette only when its role was examined and in Fig. 1. To confirm that currents were mainly carried by Cl−, NMDG-Cl was replaced by NMDG-MeSO3 or NMDG-gluconate in the external solution (Fig. 2C). Db-cAMP, 8Br-cGMP, genistein, DPC and CFTRinh-172 in the extracellular solution were applied using a perfusion system (ALA Scientific Instruments, Great Neck NY). Reversibility was examined after perfusing external solution without inhibitor or without agonist and inhibitor for 5 minutes. Since stimulation by cyclic nucleotides of CFTR is reversible in minutes (Tsumura et al., 1998; Riordan, 2005), recovery was estimated with respect to the control current, except for the experiments in epididymal sperm. Unless indicated otherwise, currents were evoked from a holding potential of −40 mV, with pulses from −80 to 100 mV in 20 mV increments and lasting 600 ms. In all cases capacitative currents were compensated electronically and no leak current compensation was used.

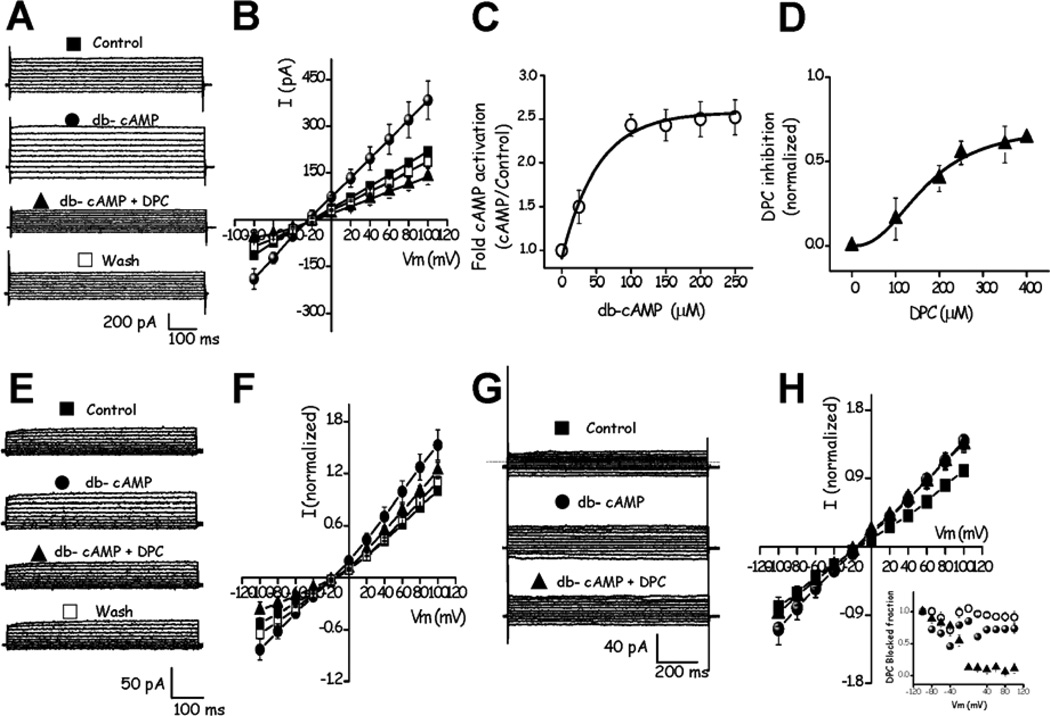

Fig. 3.

DPC inhibits the db-cAMP stimulated whole-cell Cl− currents in testicular mouse sperm in a [Ca2+]i and voltage dependent manner. A, currents were obtained applying a voltage protocol as in Fig. 2A, to sperm exposed to Cl− recording solutions (external: 145 NMDG-Cl, 2 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 10 HEPES, adjusted to pH 7.2 with NMDG/ internal: 35 NMDG-Cl, 110 NMDG-gluconate, 2 CaCl2, 2 EGTA (free Ca2+ ~10 µM), 2 MgCl2, 3 ATP-Mg, 10 HEPES, adjusted to pH 6.8 with NMDG). Control Cl− currents (■ Control) were significantly stimulated by extracellular db-cAMP (100 µM) (● db-cAMP) and inhibited following the addition of extracellular DPC (250 µM) (▲db-cAMP + DPC). DPC inhibition was partially reversible (□ Wash). B, I–V relationships of the currents in A. Symbols represent the means ± SD of 6 cells. Some SD bars were smaller than the symbols. C, Dose-response curve for db-cAMP on the whole-cell Cl− currents in testicular mouse sperm. Fold activation of macroscopic Cl− current at +100 mV plotted as a function of [db-cAMP] (○). A Hill equation was adjusted to the data (solid line) yielding an EC50= ~35 µM. D, Fractional block of macroscopic Cl− current as a function of [DPC] at −80 mV (▲), blockade was normalized with respect to the db-cAMP stimulated current at this potential. The data were fit with the Hill equation (solid line) yielding an IC50= ~175 µM and nH ~3. E, Currents obtained reducing free Ca2+ to 60 nM inside the pipette (see Methods). The db-cAMP stimulated Cl− currents (● db-cAMP) were significantly inhibited by 250 µM DPC (▲db-cAMP + DPC). This effect is partially reversible (□ Wash). F, I–V relationships of the currents in E. G, In the absence of external and internal Ca2+ (see Methods) db-cAMP increased control currents (● db-cAMP) which were inhibited by 250 µM DPC only at negative potentials (▲db-cAMP + DPC). The dotted line in G represents zero current. H, I–V relationship of the currents in G. The inset on the figure shows the DPC blocked fraction of the currents as a function of voltage and [Ca2+]i. All pipette solutions contained ATP. Symbols represent the means ± SEM of six independent experiments (some SEM bars were smaller than symbols) with the exception of B which shows SDs, and F and H where n=3. Current voltage relations (B, F and H) show data normalized with respect to the control Cl− current measured at +100 mV.

Fig. 1.

DPC inhibits and db-cAMP stimulates the macroscopic currents of testicular sperm. A, representative macroscopic currents before (■ Control), during (▲DPC) and after (□ Wash) DPC (250 µM) exposure. The currents were evoked using 200 ms square test pulses from a holding potential of −40 mV to voltages between −100 to 40 mV in 10mV increments. The dotted line in A represents zero current. B, mean whole cell current-voltage (I–V) relationships recorded in A. Addition of 250 µM DPC (▲) reduced the normalized currents ~35% at −100 mV with respect to the control C (■). Current inhibition by DPC is partially reversible (□ Wash). The top inset in the figure shows the kinetics of DPC inhibiton at −100 mV. Symbols represent the means ± SD of 18 cells. Some SD bars were smaller than the symbols. The bottom inset in the figure depicts the DPC percent inhibition of the currents as a function of voltage. Symbols represent the means ± SEM of six independent experiments. C, db-cAMP (○) significantly increased control currents recorded under physiological ionic conditions. db-cAMP (100 µM) stimulated by ~89% the control sperm currents. D, I–V relationships for the currents in C. The top inset in the figure illustrates the kinetics of DPC inhibition of the currents activated by cAMP at −100 mV. Symbols represent the means ± SD of 18 cells. Some SD bars were smaller than the symbols. The bottom inset shows the DPC percent inhibition of the cAMP activated currents as a function of voltage. Symbol represents the means ± SEM of six experiments. Currents were normalized with respect to the maximum current of the control at −100 mV.

Fig. 2.

Effect of extracellular Cl− concentration on whole-cell currents in testicular mouse sperm. A, whole-cell Cl− currents recorded in the presence of 35 mM intracellular Cl− (as NMDG-Cl) and different extracellular Cl− concentrations (mM): 145 NMDG-Cl (■), 110 NMDG-Cl (○), 60 NMDG-Cl (●) y 35 NMDG-Cl (Δ). The currents were recorded by applying square voltage pulses from a holding potential of −40 mV to test potentials ranging from 100 to −80 mV in 20 mV steps. The applied voltage protocol is shown between A and D. B, I–V relationships of the currents in A, showing the change in zero-current values (reversal potential, Erev) as extracellular Cl− was reduced. C, I–V plots illustrating the current changes that result when external Cl− (■) is replaced by MeSO3 (○) or gluconate (▼). Symbols represent the means ± SEM of five experiments. Some SEM bars were smaller than the symbols. D, Whole-cell currents recorded in the presence of extracellular Cl−, Br−, I− and HCO3−, respectively. The currents were obtained from sperm exposed to 145 mM TEA salts of the following external anions Cl− (■), Br− (○),I− (□), and HCO3− (▲), respectively after stimulation with db-cAMP. The applied voltage protocol is shown under A. E, I–V curves obtained from the currents in D. Replacement of external Cl− by Br−, I− and HCO3− in these experiments shifted Erev gaving a permselectivity sequence of Br−≥Cl−>I−>HCO3−. Symbols represent the means ± SEM of three experiments. F, I–V curve shows blockage by DPC (250 µM, ▲) and additional inhibition by NA (50 µM, ○) of the basal sperm Cl− currents (■). The inhibitory effect of blockers was partially reversible (□ Wash). All pipette solutions contained ATP. Symbols represent the means ± SEM of five experiments; some SEM bars were smaller than symbols. The currents were normalized with respect to the Cl− current of the control (145 mM external Cl−) at 100 mV.

Sperm analysis by flow cytometry

Sperm were obtained from CD1 male mice (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) by manually triturating cauda epididymis in a 1 ml drop of Whitten’s HEPES-buffered medium. This medium does not support capacitation unless supplemented with 5 mg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA, fatty acid-free) and 15 mM of NaHCO3. After 10 min, the fraction of motile sperm was diluted four times in medium for capacitation, adding NaHCO3 and BSA. Sperm were incubated in capacitation medium at 37 °C for 60 min. To test the effect of CFTRinh-172 inhibitor on capacitation, sperm were preincubated with the inhibitor in non-capacitating medium for 15 min prior to beginning of capacitating period. Before assaying the sperm by flow cytometry, sperm suspensions were filtered through a 100-µm nylon mesh (Small Parts, Inc. USA). Analyses were conducted using a LSR II flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) by using a 488-nm argon excitation laser. Recording of scatter properties of all events stopped when 50,000 events were reached. Two dimensional plots of sideways- (SSC) and forward-scatter (FSC) properties were obtained using FlowJo™ software v7.6 (Adam Treister and Mario Roederer, Tree Star, Inc. USA). Forward-scatter and sideways-scatter light properties are proportional to the cell-surface area (size) and the granularity of the cell respectively.

Statistical Analysis

Most data are expressed as the mean ± SEM of n independent experiments. Only figures 1B, D and 3B show the raw values of the currents with the SD to appreciate their magnitude and variability. The means were compared using paired Student’s t test and p = 0.05 was considered to be the limit of statistical significance.

3. RESULTS

Previously we and others have shown the presence of CFTR in sperm using immunological detection and specific inhibitors; however, CFTR currents have not been characterized before. To directly determine the functional presence of CFTR channels, we recorded whole-cell currents by sealing at the cytoplasmic droplet of mouse testicular sperm (Santi et al., 2010; Kirichok and Lishko, 2011). Initially currents were evoked in cells exposed to physiological external solution (see Methods) from a −40 mV holding potential by square voltage steps, lasting 300 ms, from −100 to 40 mV in 10 mV increments (Fig. 1A). At positive potentials the currents rapidly activate and remain constant over the employed time window. The currents at negative potentials are slightly smaller than those at positive potentials (compare slopes of the I–V curves in Fig. 1B). Addition of DPC (250 µM), a CFTR inhibitor, reduced the current at −100 mV by 35 ± 5 % (n=6) (Fig. 1A middle) in a partially reversible manner (Fig. 1A bottom). Figure 1B illustrates I–V curves obtained from experiments in figure 1A. The top inset in figure 1B illustrates the time course of DPC inhibition of the currents at −100 mV (n=18). The bottom inset in figure 1B shows the voltage dependence of the DPC percent inhibition (n=6) which is similar to that reported earlier for heterologously expressed CFTR (McCarty et al., 1993).

Because cAMP-dependent phosphorylation is a prerequisite for CFTR function, we also examined the effect of a membrane-permeable cAMP analogue (db-cAMP). Addition of db-cAMP (100 µM) activated the currents by 87 ± 2% (n=6) at −100 mV in physiological extracellular solution (Fig. 1C, bottom). Part D illustrates the I–V curves obtained from experiments shown in figure 1C. In addition, we also recorded the currents with cAMP (100 µM) in the pipette (Fig. 1D, open triangles). The top inset in figure 1D illustrates the time course of DPC inhibition of the intracellular cAMP activated currents at −100 mV (n=18). The bottom inset in figure 1D again shows that the DPC percent inhibition is voltage dependent (n=6).

The experiments described above were carried out using physiological solutions therefore several types of channels may contribute to the currents. However, the results show that there is a cAMP and DPC sensitive component that could be due to CFTR. DPC at similar concentrations can also inhibit Ca2+ activated Cl− channels (CaCCs), which at an estimated [Ca2+]i of 75 nM would be activated ~30 % (Arreola et al., 1996), and other cAMP stimulated Cl− currents (Tsumura et al., 1998). The DPC-resistant current recorded under these conditions reflects the contribution of other ionic channels present in sperm (Martínez-López et al., 2011; Santi et al., 2010).

To further establish the functional presence of CFTR channels in mouse sperm, we modified the ionic composition of the solutions to determine the selectivity of the DPC-sensitive currents and included 3 mM ATP in the pipette solution in all further experiments unless indicated. This was done by substituting all monovalent cations by the non-permeant NMDG and following the reversal potential (Erev) at different extracellular Cl− concentrations (NMDG-Cl), keeping [Cl−]i at 35 mM (Fig. 2A). Panel B of this figure illustrates the I–V curves obtained at different external Cl− concentrations, where the Erev values are consistent with the theoretical ECl− values calculated from the Nernst equation (Table 1). As expected, replacement of most Cl− (95 %) in the external solution with MeSO3− or gluconate−, two impermeant anions, significantly decreased the current, eliminated the DPC inhibition and shifted Erev away from ECl− (−24.5 mV) to −2.2 ± 0.8 mV (MeSO3−, n=5) and −3 ± 0.6 mV (gluconate, n=5) (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, experiments comparing Erev (Table 2) for sperm exposed to different external anions and stimulated with db-cAMP gave a selectivity sequence Br−≥Cl−>I−>HCO3− (see Fig. 2E), in agreement with that displayed by heterologously expressed CFTR (Anderson et al., 1991). Figure 2D shows whole-cell currents recorded in these conditions. Together, these results indicate that the fraction of current inhibited by DPC corresponds to sperm Cl− currents that have a component most likely conducted through CFTR.

TABLE 1.

Reversal potencial (Erev) data obtained from the currents in sperm and theorical ECl values at differents extracellular Cl− concentrations.

| Cl− concentration (mM) (Bath solutiona/Pipette solutionb) |

Experimental Erev (mV) |

Theoretical Erev (mV) |

|---|---|---|

| 145/35 | −24.5 ± 0.4 | −31.9 |

| 110/35 | −22.9 ± 0.2 | −25.4 |

| 60/35 | −11.5 ± 0.2 | −11 |

| 35/35 | +1.4 ±0.2 | 0 |

Bath solutions contained (in mM): 145 (110, 60 or 35) NMDG-C1, 0 ( 35, 65 or 110) NMDG-gluconate, 2 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 10 HEPES, adjusted to pH 7.2/NMDG.

The pipette solution contained (inmM): 35 NMDG-C1, 110 NMDG-gluconate, 2 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, 3 ATP-Mg, 2 EGTA, 10 HEPES, adjusted to pH 6.8/NMDG.

The data represents the means ± SEM of six experiments.

TABLE 2.

Permeability of CFTR Channels to Intracellular Anions in Mouse Sperm

| Extracellular anion | Erev | PX/PCl | n |

|---|---|---|---|

| mV | |||

| Bromide | −30.2±1.2 | 1.2 | 3 |

| Chloride | −26.5±1.0 | 1 | 3 |

| Iodide | −9.3 ±1.8 | 0.54 | 3 |

| Bicarbonate | −6.3±1.1 | 0.48 | 3 |

Summary of mean reversal potentials and permeability ratios measured with different extracellular anions in mouse sperm. See material and methods for details.

As CFTR may not be the only Cl− channel in mouse sperm and our internal solution had ~10 µM free Ca2+ we performed experiments in the presence of niflumic acid (NA), an inhibitor better known for blocking Ca2+ activated Cl− channels (IC50~10 µM) (Hartzell et al., 2005), to examine this latter channel’s contribution. Using Cl− as the main charge carrier, we first exposed sperm to 250 µM DPC, which should block most CFTR current (IC50= 175 µM, see Fig. 3G) and partially affect CaCCs (Schroeder et al., 2008), and then added 50 µM NA which significantly increased inhibition of the Cl− currents from 37 ± 3 % to 50 ± 0.4 % (n=5) (Fig. 2F). The DPC- and NA-induced inhibition largely reversed upon washing (74.5 ± 0.4 %) (Fig. 2F) (n=5), as described for heterologously expressed CFTR experiments (Schultz et al., 1999) and Ca2+ activated Cl− channels in Xenopus oocytes (Hartzell et al., 2005).

To dissect the contribution of both CFTR and CaCCs to the total Cl− currents in mouse testicular sperm we compared recordings with 10 µM (Fig. 3A and B) and 60 nM free Ca2+ (Fig. 3E and F) inside the pipette, and without Ca2+ in the pipette and in the external media (Fig. 3G and H). Figure 3A shows that 100 µM db-cAMP significantly increased the current by 75 ± 12 % (+100 mV, n=9). A concentration-response study indicated an IC50 of ~ 35 µM for db-cAMP (Fig. 3C), which is close to that described for heterologously expressed CFTR (Sullivan et al., 1995). As expected, the addition of this permeant cAMP analog shifted the Erev of the activated currents closer to the theoretical ECl− of −31.9 mV (Fig. 3B) and potentiated the DPC inhibition at 250 µM of the Cl− currents by 69.8 ± 10 % at −80 mV (Fig. 3A and B). This inhibition was partially reversible (Fig. 3A bottom and B) and displayed an IC50 of ~175 µM (Fig. 3D), similar to the previously observed inhibition on heterologously expressed CFTR (Zhang et al., 2000). However, the Hill coefficient (nH) of the DPC blockade obtained was ~3 and not 1 as anticipated for CFTR alone (Zhang et al., 2000). This result is consistent with the presence in mouse sperm of both CFTR and CaCCs, whose nH is ~3 (Qu et al., 2003). Experiments performed using 8Br-cAMP instead of db-cAMP yielded similar results (n=3; not shown).

Figure 3E and F show that at 60 nM [Ca2+]i db-cAMP increased the current by 53 ± 8 % at +100 mV (n=3, ± sd). The DPC blockade at positive potentials, where CFTR is not inhibited by this compound, depends on [Ca2+]i. At +100 mV blockade decreased from 63.8 ± 25 % (n=9, ± sd) at 10 µM to 19.3 ± 6.8 % (n=6, ± sd) at 60 nM [Ca2+]i while at −80 mV it was 69.8 ± 10 % at 10 µM and 51.4 ± 15 % at 60 nM [Ca2+]i (Fig. 3E and F). Finally, the currents and I–V curves obtained in the absence of external Ca2+ and using internal solutions with 0 free Ca2+ to eliminate all CaCCs activity are shown in figures G and H. At +100 mV db-cAMP stimulated the current by 39 ± 4.6 % (n=3, ± sd). As expected, blockade was only observed at negative potentials where CFTR is sensitive to this compound (18 ± 2.3 % at −100 mV, n=3, ± sd). The inset in figure 3H summarizes how [Ca2+]i affects the voltage dependence of the DPC blockade. These results agree with published findings of the DPC voltage dependent blockade of CFTR currents (Zhang et al. 2000; McCarty et al. 1993; Walsh and Wang 1996; Schultz et al., 1999). In addition, these findings corroborate the presence of CaCCs in mouse sperm (Espinosa et al., 1998), which were not further characterized.

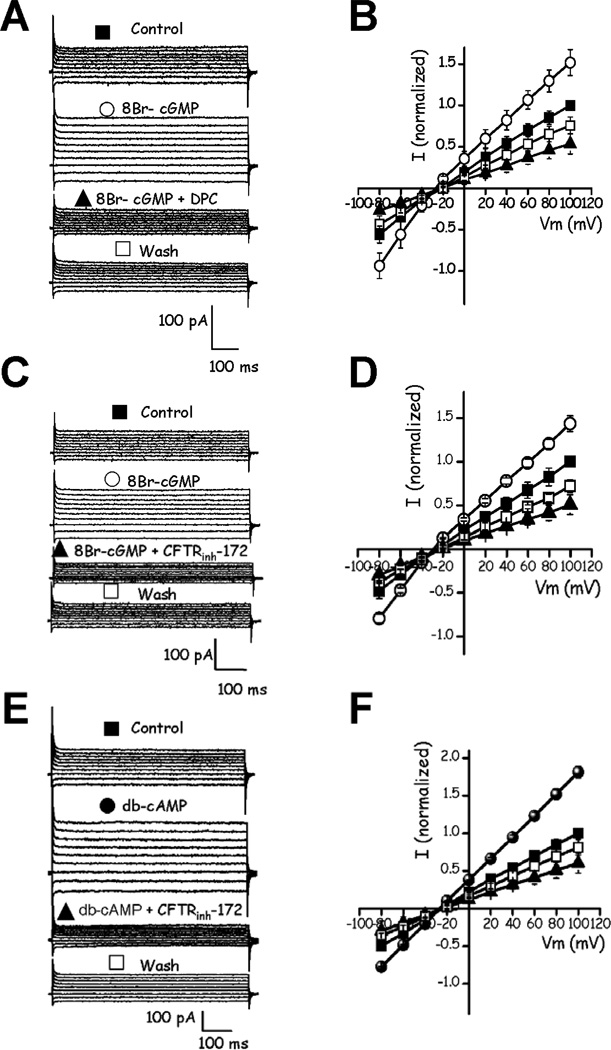

In our hands, obtaining the whole cell configuration was significantly more difficult in the absence of [Ca2+]i therefore in the rest of the experiments it was maintained at 10 µM, except for the experiments in epididymal sperm. Heterologously expressed CFTR is also stimulated by cGMP (IC50 ~0.3 µM) (Sullivan et al., 1995). Experiments adding 20 µM 8Br-cGMP to testicular mouse sperm stimulated the sperm Cl− currents and these currents were sensitive to DPC. The DPC induced inhibition was partially reversed upon washing (Fig. 4A and B). Both the pharmacology and the ionic selectivity of the mouse sperm currents contain a component whose properties are consistent with those of CFTR. To test further the notion that the Cl− currents stimulated by cyclic nucleotides and inhibited by DPC are through CFTR, CFTRinh-172 (2–5 µM), a more specific and reversible blocker of this channel, was tested. All the current stimulated by the cyclic nucleotide analogs was eliminated by this inhibitor which decreased the current beyond the unstimulated level (Fig. 4C – D). Considering the cyclic nucleotide stimulated current as 100 %, CFTRinh-172 inhibited 50 % of the 8Br-cGMP-dependent current and 60 % of that stimulated by db-cAMP (Fig. 4C, D, E and F). In addition, CFTRinh-172 (2–5 µM) and DPC (250 µM) also inhibited (19.9 ± 4 %, n=6; 21.8 ± 4 %, n=5, respectively) the Cl− currents in the absence of cyclic nucleotide (Supplementary Fig. 1, DPC values at −80 mV). This indicates that there are basally active CFTR channels and explains why addition of the inhibitors decreases the current beyond the unstimulated current level.

Fig. 4.

DPC and CFTRinh-172, two CFTR channel inhibitors, block the 8Br-cGMP and db-cAMP stimulated whole-cell Cl− currents in testicular mouse sperm. A, representative recordings from a whole-cell patch-clamp experiments in control conditions as in Fig. 3A (■ Control) showing Cl− current activation by 8Br-cGMP (20 µM) (○ 8Br-cGMP) and their inhibition by 250 µM DPC (▲ 8Br-cGMP + DPC). Blockade by DPC was partially reversible (□ Wash). B, I–V curves of the currents in A. C, 8Br-cGMP-stimulated Cl− currents (○ 8Br-cGMP) were also significantly inhibited by 5 µM CFTRinh-172 (■ 8Br-cGMP + CFTRinh-172) and this effect was partially reversible (□ Wash). D, I–V relationships of the currents recorded in C. E, Cl− currents (■ Control) are also significantly stimulated by db-cAMP (100 µM) (● db-cAMP) and inhibited by extracellular CFTRinh-172 (5 µM) (■db-cAMP + CFTRinh-172) in a partially reversible manner (□ Wash). F, I–V relationships of the currents in E. The applied voltage protocol is as in Fig. 3. The currents were recorded under the ionic conditions as in Fig. 3A. Symbols represent the means ± SEM of six experiments; some of the SEM bars were smaller than symbols. The currents in IV plots were normalized with respect to the maximum of the control Cl− current at +100 mV.

CFTR is characteristically activated by genistein (Wang et al., 1998; Gadsby and Nairn, 1999), a phenomenon that was indirectly shown to occur in mature mouse sperm (Hernandez-Gonzalez, et al., 2007). Figure 5A–D shows that 20 µM genistein caused a DPC sensitive stimulation (54 ± 0.5 % at 20 µM, at −80 mV) (n=6) of the sperm currents, while at 50 µM a lesser level of stimulation was observed (38 ± 0.7 % at 50 µM, at −80 mV) (n=6). These results are consistent with the bell-shaped concentration dependence of the genistein effect on CFTR documented previously (Wang et al., 1998; Gadsby and Nairn, 1999; see Discussion section).

Fig. 5.

Genistein increases the whole-cell Cl− currents in testicular mouse sperm. A, genistein at 20 µM (○ Genistein) potentiated Cl− currents with respect to control currents (■ Control). The stimulated current was inhibited by DPC (250 µM) (■ Genistein + DPC) reversibly (□ Wash). B, I–V curves of the currents in A. C, notably, a higher isoflavonoid concentration (○ Genistein 50 µM) stimulated the currents to a lesser extent than as seen with 20 µM (A). DPC (250 µM) caused the anticipated inhibition of the current (■ Genistein + DPC) in a partially reversible form (□ Wash). D, I–V relationships of the currents in C. The currents were obtained applying a voltage protocol as in Fig. 2A and using the ionic conditions as in Fig. 3A. E and F, ATP dependence of the db-cAMP-activated testicular mouse sperm Cl− currents and their blockade by DPC. The concentrations used were: 100 µM db-cAMP (A), 100 µM db-cAMP + 250 µM DPC (A+I) in the control condition (C) in the presence (///) or absence (□) of ATP (3 mM). Currents were recorded under ionic conditions as in Fig. 4. The macroscopic Cl− currents at +100 mV (E) and −80 mV (F), normalized with respect to the corresponding control without ATP were used to measure the ATP dependence. Symbols represent the means ± SEM of six experiments. Some SEM bars were smaller than the symbols. a, b and c were not significantly different; *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001. For F: d, p<0.05 and e, p<0.01, f, n.s, *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01.

The stimulation of CFTR caused by cAMP is ATP dependent (Hwang et al., 1994; Ikuma and Welsh, 2000). Figure 5E and F illustrates that the mouse testicular currents mainly carried by Cl− reproduce this behavior. The permeant analog of cAMP is significantly less able to stimulate the DPC sensitive component of the currents in the absence of ATP both at +100 mV and at −80 mV.

To establish whether the Cl− currents stimulated by cAMP and inhibited by CFTRinh-172 are due to CFTR channels, we explored if they were present in testicular sperm from ΔF508 CFTR loss-of-function mice. Deletion of phenylalanine 508 (ΔF508) is the most common mutation in cystic fibrosis; it impairs CFTR folding and consequently, its biosynthetic and endocytic processing as well as its Cl− channel function (Lukacs and Verkman, 2011). As anticipated, the Cl− currents of sperm from ΔF508 CFTR loss-of-function mice are not stimulated by 100 µM cAMP or inhibited by 5 µM CFTRinh-172 (Fig. 6A and B). They were by contrast present in sperm obtained from CFTR-ΔF508 littermate wild type mice (Fig. 6C and D). These findings strongly argue that CFTR channels are functionally present in testicular mouse spermatozoa.

Fig. 6.

Anion currents of testicular mouse sperm of CFTR-■F508 mutant mice are not stimulate by cAMP or inhibited by CFTRinh-172. A, the currents were obtained applying voltage protocol as in Fig. 3A, to a sperm obtained from a CFTR-■F508 mutant mouse bathed with control Cl− recording solution (145 mM NMDG-Cl external/35 mM NMDG-Cl internal). Whole-cell Cl− currents were recorded before (■ Control) and after addition of 100 µM db-cAMP (● db-cAMP), 5 µM CFTRinh-172 (■db-cAMP + CFTRinh-172), and finally after washout (□ Wash). B, I–V relationships of the currents in A. C, currents in a sperm obtained from a wild type litter-mate of the CFTR-■F508 mutant mice in A show that db-cAMP-stimulated Cl− currents (● db-cAMP) are also significantly inhibited by 5 µM CFTRinh-172 (■db-cAMP + CFTRinh-172) and this effect is partially reversible (□ Wash). D, I–V relationships of currents recorded as in C. All pipette solutions contained ATP. These results demonstrate that the Cl− current component activated by cAMP and inhibited by CFTRinh-172 indeed must correspond to active CFTR. Symbols represent the means ± SEM of three experiments; some SEM bars were smaller than the symbols. The currents were normalized with respect to the control Cl− current at 100 mV.

Recent evidence has indicated that ion channels such as Cav3s recorded in mouse testicular sperm (Martinez-Lopez et al., 2011) cannot be detected in more mature epididymal sperm (Ren and Xia, 2010; Kirichok and Lishko, 2011). To ascertain if CFTR-like currents are functional in more mature sperm these currents were recorded in mouse sperm obtained from the epididymis. Figure 7 shows currents recorded with the same external and internal solutions as figure 3E and F (containing 3 mM ATP and 60 nM [Ca2+]i), used to characterize the CFTR currents in testicular sperm, in the presence of NA (50 µM). The currents were significantly stimulated by db-cAMP (63 ± 5 % at +100 mV) and inhibited by CFTRinh-172 at all potentials (71 ± 3 % at +100 mV, n=4) (Fig. 7A, B and C). This inhibition was partially reversible (81 ± 4 %) (Fig. 7A bottom and B). These experiments demonstrate that there are Cl− currents in epididymal sperm that are stimulated by db-cAMP and blocked by CFTRinh-172 similar to those obtained in testicular sperm with characteristics consistent with the presence of the CFTR channel in more mature sperm. These findings indicate functional CFTR channels are preserved as spermatozoa mature in transit from the testicle through the epididymis. Figure 7D illustrates the I–V curve corresponding to the current obtained by subtracting the CFTRinh-172 sensitive current from the db-cAMP stimulated current has the anticipated characteristics of a CFTR-like current. Therefore, as we could not find stimulation by db-cAMP or inhibition by CFTRinh-172 in testicular sperm from ΔF508 CFTR loss-of-function mice, these results strengthen the likelihood that functional CFTR currents are preserved in mouse epididymal sperm. Furthermore, these findings are consistent with other functional data indicating CFTR channels play a role during capacitation (Guggino and Stanton, 2006; Wertheimer et al., 2008; Chen et al., 2009; Li et al., 2010; Chávez et al., 2012; Escoffier et al., 2012).

Fig. 7.

CFTR channels are functional in epididymal mouse spermatozoa. A, extracellular db-cAMP (100 µM) (● db-cAMP) significantly stimulates whole-cell control Cl− currents (■ Control) and CFTRinh-172 at external concentrations that inhibit CFTR (5µM) (■db-cAMP + CFTRinh-172) blocked them in a partially reversible manner (□ Wash). The effects of agonist and Inh-172 were recorded with the same external and internal solutions as in Fig. 3F (60 nM free Ca2+ inside the pipette) used to characterize the CFTR currents in testicular sperm, in the presence of NA (50 µM), to eliminate the contribution of other Cl− channels. B, I–V relationships of the currents in A. C, summary of activation and inhibition of the Cl− currents in the presence of CFTR´s agonist and antagonists respectively, on the control Cl− currents at +100 mV in epididymal sperm. D, I–V plot showing the arithmetic difference between the currents in presence of db-cAMP (●) and + CFTRinh-172 (▲) shown in A. Symbols represent the means ± SEM of four experiments; some SEM bars were smaller than the symbols. The currents were normalized with respect to the stimulated Cl− current at +100 mV. **, p<0.01; *, p<0.05.

Considering that it is well known that Cl− channels participate in volume regulation in many cell types including sperm (Yeung et al., 2005; Duran et al., 2010), we tested the effects of CFTRinh-172 on epididymal capacitated mouse sperm and subjected them to cell sorting (see Methods). This inhibitor caused a significant change in the Forward vs. side scatter two dimensional dot plots. This observation is consistent with a sperm volume change and suggests the participation of CFTR channels in setting the volume of sperm (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

CFTRinh-172 modifies the sideways- (SSC) and forward-scatter (FSC) properties of epididymal capacitated mouse sperm. A, Two dimensional plots of sideways- (SSC) and forward-scatter (FSC) properties of cauda epididymal mouse sperm incubated under capacitating conditions (CAP) in the absence or in the presence of increasing concentrations of CFTRinh-172 (0, 1, 5, 10, 20 and 40 µM). Each dot represents the two types of scatter from an individual sperm. B, average ± SEM of sperm mean forward-scatter and sideways-scatter light of five independent experiments in which sperm were incubated with increasing concentrations of CFTRinh-172 under capacitating conditions ((*, p<0.05**, p<0.01) and (***, p<0.001) are statistically significant). Histogram of the SSC and FSC mean fluorescence ± SEM from five independent experiments (*, p<0.05; **, p<0.01) and (***, p<0.001) are statistically significant.

4. DISCUSSION

CFTR, a cAMP/PKA and ATP-regulated Cl− channel, is mutated in patients with cystic fibrosis. This Cl− channel plays a crucial role in the transport of Cl− and HCO3− in several cellular types and interacts with other proteins such as ENaCs, Cl−/HCO3− exchangers, and the Na+/HCO3− cotransporter, to control ion transport (reviewed in Riordan, 2005). Notably, CFTR has been immunodetected in the mid piece and the post acrosomal region of mouse, guinea pig and human sperm. Pharmacological tools and indirect functional assays have indicated that CFTR participates in capacitation and possibly in hyperactivation, the acrosome reaction and in fertilization (Hernandez-Gonzalez et al., 2007; Xu et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2009; Li et al., 2010; Visconti et al., 2011).

Membrane potential measurements in mouse sperm revealed that CFTR is activated by cAMP and its activation may lead to the closure of ENaC channels, which are also located in the mouse sperm mid piece (Hernandez-Gonzalez et al., 2006; Hernandez-Gonzalez et al., 2007). ENaC closure was shown to contribute to the hyperpolarization that accompanies mouse sperm capacitation. Our findings suggest that a functional CFTR is required for the [Cl−]i increase and the hyperpolarization that accompany capacitation (Hernandez-Gonzalez et al., 2007). These permeability changes are most likely necessary to achieve the increase in intracellular HCO3− that stimulates SACY, a crucial event for capacitation (reviewed in Visconti et al., 2011). The HCO3− requirement for capacitation has been widely established (Visconti et al., 2011) and it has been proposed that a Na+/HCO3− cotransporter significantly contributes to the initial increase in intracellular HCO3− (Demarco et al., 2003). In addition, HCO3− could be entering the cell through Cl−/HCO3− exchangers (Zeng et al., 1996; Chen et al., 2009; Visconti et al., 2011) and through CFTR, as observed in other cell types (Ishiguro et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2009), and proposed in sperm (Chen et al., 2009).

The fact that CFTR has been detected in the sperm post acrosomal region is consistent with reports indicating its participation in the human sperm acrosome reaction and in fertilization (Li et al., 2010). However, experiments in the mouse system also performed with DPC and CFTRinh-172, though under different conditions, indicated inhibition occurred during sperm capacitation and not during the acrosome reaction, and no effects were found on the regulation of the capacitation-associated increase in tyrosine phosphorylation (Hernandez-Gonzalez et al., 2007; Wertheimer et al., 2008). These differing findings could also reflect distinct aspects of the mouse and human sperm signaling cascades that are becoming apparent, as in the progesterone activation of CatSper (Lishko et al., 2011; Strünker et al., 2011) and the presence of proton channels (Hv) (Lishko et al., 2010).

Here we show that whole-cell currents recorded from testicular mouse sperm display a Cl− selective component that is ATP-dependent, stimulated by cAMP, cGMP and genistein (a CFTR agonist, at low concentrations), and inhibited by DPC and CFTRinh-172, two well-known CFTR antagonists (Schultz et al., 1999; Ma et al., 2002; Hernandez-Gonzalez et al., 2007; Caci et al., 2008). Remarkably, the genistein effect is higher at 20 µM than at 50 µM (see fig. 5). An explanation of the biphasic effect of genistein on the CFTR channel suggests that phosphorylated CFTR has two binding sites for genistein, one of higher affinity (5–30 µM) and one of lower affinity (>35 µM) (Wang et al., 1998; Gadsby and Nairn, 1999). It is proposed that genistein interacts with NBD2 lengthening the average time of the channel’s open state. The effect of genistein on channel gating is similar to that of the non-hydrolysable ATP analogues, suggesting a possible interaction with NBD2. The association of genistein to the lower affinity site in NBD1 potentially inhibits channel opening (Wang et al., 1998). Possibly, at high concentrations, genistein can also bind weakly to a site within the pore of CFTR where it may act as an open-channel blocker (Lansdell et al., 2000).

The overall characteristics of a component of the Cl− currents documented here in mouse testicular sperm match those described for CFTR in many cell types and in heterologously expressed CFTR channels (Gong et al., 2001; Riordan et al., 2005; Guggino and Stanton, 2006). The presence of functional CFTR in mouse testicular sperm is further demonstrated by the fact that Cl− currents recorded from sperm from CFTR ΔF508 loss-of-function mice displayed no cAMP stimulation and were insensitive to CFTRinh-172.

It is worth noting that mouse testicular sperm possess Cl− currents stimulated by db-cAMP, 8-Br-cGMP and genistein that are blocked by NA and DPC at positive potentials (Fig. 2F, Fig. 3A, B, E, F, 4A–D, 5A–D) in an ATP dependent manner (Fig. 5E). Part of the blocked currents may be due to CaCCs (Shroeder et al., 2008; Tian et al., 2011), consistent with previous single channel patch-clamp recordings documenting the presence of a NA sensitive Cl− channel (IC50 = 11 µM) (Espinosa et al., 1998) with a very similar sensitivity as that of the recently identified Ca2+ dependent Cl− channel TMEM16A (Galietta, 2009). Matchkov et al. (2004) and Piper and Lang (2003) report Ca2+ dependent and voltage and time independent Cl− currents stimulated by cGMP in rat smooth muscle (cGMP EC50 = 6.4 µM). In the presence of cGMP these currents are stimulated by cAMP by ~ 10 %. Therefore, part of the inhibition caused by DPC at positive potentials upon the cGMP stimulated currents may be also due to CaCCs, and cAMP could also mildly stimulate these currents. Another component of these Cl− currents is similar to that reported in guinea-pig Paneth cells apparently lacking CFTR. These cells display currents with very similar characteristics to CFTR that are stimulated by db-cAMP, ATP dependent and blocked by DPC even at positive potentials (Tsumura et al., 1998). If present in mouse sperm, such a current would contribute to the blockade of DPC at positive potentials and its dependence on ATP. Genistein stimulates CFTR but can also inhibit tyrosine kinases (Akiyama and Ogawara, 1991) which could somehow stimulate CaCCs or the CFTR like current (Tsumura et al., 1998) in sperm. Future experiments will have to be performed to examine if these channels and CaCCs can be stimulated by genistein and why DPC blockade at positive potentials is ATP dependent. On the other hand, we do not fully understand why DPC and CFTRInh-172 block a similar fraction of the current at positive potentials possibly indicating that CaCCs and CFTR currents appear to have a similar contribution.

To ascertain whether the CFTR-like currents are maintained during epididymal maturation, epididymal sperm were patch-clamped under the conditions used to study the Cl− currents using an internal solution containing 60 nM [Ca2+]i. The currents we recorded were similar to those seen in testicular sperm (Fig. 7). They were activated by db-cAMP and inhibited by CFTRinh-172; the difference between these two conditions yielded currents displaying I–V characteristics compatible with those of CFTR.

Furthermore, in agreement with the role of Cl− channels in cell volume regulation (Yeung et al., 2005; Duran et al., 2010; Ando-Akatsuka et al., 2002), the CFTR inhibitor induced volume changes in epidydimal mouse sperm. Our overall results are consistent with the functional presence of CFTR channels in mouse sperm and with their proposed participation in sperm physiology.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by DGAPA: IN211809 (to AD), CONACyT: 49113 and 128566 (to AD), NIH: R01 HD44044 and HD038082 (to PEV). Work at CECs was partially funded by Conicyt PFB. We would also like to thank the Posgrado en Ciencias Biológicas de la UNAM as DFF is their PhD student. DFF was a fellow of CONACyT, Number 49115. We appreciate the advice of the Dra. María Isabel Niemeyer (CECs) in technical aspects of the work and Dr. B.J. Scholte (Erasmus University) for providing the CFTR-DF508 mice and for technical assistance. The assistance of Marcela Ramírez, Elizabeth Mata, Juan Manuel Baamonde and José Luis De La Vega is also gratefully acknowledged.

REFERENCES

- Acevedo JJ, Mendoza-Lujambio I, De la Vega-Beltran JL, Treviño CL, Felix R, Darszon A. KATP channels in mouse spermatogenic cells and sperm, and their role in capacitation. Dev Biol. 2006;289:395–405. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson MP, Gregory RJ, Thompson S, Souza DW, Paul S, Mulligan, Smith AE, Welsh MJ. Demonstration that CFTR is a chloride channel by alteration of its anion selectivity. Science. 1991;253:202–205. doi: 10.1126/science.1712984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ando-Akatsuka Y, Abdullaev I, Lee EL, Okada Y, Sabirov R. Down-regulation of volume-sensitive Cl− channels by CFTR is mediated by the second nucleotide-binding domain. Pflugers Arch. 2002;445:177–186. doi: 10.1007/s00424-002-0920-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arreola J, Melvin JE, Begenisich T. Activation of calcium-dependent chloride channels in rat parotid acinar cells. J Gen Physiol. 1996;108:35–47. doi: 10.1085/jgp.108.1.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baukrowitz T, Hwang T-C, Nairn AC, Gadsby DC. Coupling of CFTR Cl− channel gating to an ATP hydrolysis cycle. Neuron. 1994;12:473–482. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90206-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berdiev BK, Qadri YJ, Benos DJ. Assessment of the CFTR and ENaC association. Mol Biosyst. 2009;5:123–127. doi: 10.1039/b810471a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucher RC. New concepts of the pathogenesis of cystic fibrosis lung disease. Eur Respir J. 2004;23:146–158. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00057003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck J, Sinclair ML, Schapa L, Cann MJ, Levin LR. Cytosolic adenylyl cyclase defines a unique signaling molecule in mammails. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:79–84. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.1.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caci E, Caputo A, Hinzpeter A, Arous N, Fanen P, Sonawane N, Verkman AS, Ravazzolo R, Zegarra-Moran O, Galietta LJ. Evidence for direct CFTR inhibition by CFTR (inh)-172 based on Arg347 mutagenesis. Biochem J. 2008;413:135–142. doi: 10.1042/BJ20080029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chávez JC, Hernández-González EO, Wertheimer E, Visconti PE, Darszon A, Treviño CL. Participation of the Cl-/HCO3- exchangers SLC26A3 and SLC26A6, the Cl- channel CFTR, and the regulatory factor SLC9A3R1 in mouse sperm capacitation. Biol Reprod. 2012;86:1–14. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.111.094037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WY, Xu WM, Chen ZH, Ni Y, Yuan YY, Zhou SC, Zhou WW, Tsang LL, Chung YW, Höglund P, Chan HC, Shi QX. Cl− is required for HCO3− entry necessary for sperm capacitation in guinea pig: involvement of a Cl−/HCO3− exchanger (SLC26A3) and CFTR. Biol Reprod. 2009;80:115–123. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.068528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Cann MJ, Litvin TN, Iourgentko V, Sinclair ML, Levin LR, Buck J. Soluble adenylyl cyclase as an evolutionarily conserved bicarbonate sensor. Science. 2000;289:625–628. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5479.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darszon A, Nishigaki T, Wood C, Treviño CL, Felix R, Beltran C. Calcium channels and Ca2+ fluctuations in sperm physiology. Int Rev Cytol. 2005;243:79–172. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(05)43002-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demarco IA, Espinosa F, Edwards J, Sosniik J, De la Vega-Beltran JL, Hockensmith JW, Kopf GS, Darszon A, Visconti PE. Involvement of a Na+/HCO− 3 cotransporter in mouse sperm capacitation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:7001–7009. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206284200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duran C, Thompson CH, Xiao Q, Hartzell HC. Chloride channels: often enigmatic, rarely predictable. Annu Rev Physiol. 2010;17:95–121. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021909-135811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escoffier J, Krapf D, Navarrete F, Darszon A, Visconti PE. Flow cytometry analysis reveals a decrease in intracellular sodium during sperm capacitation. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:473–485. doi: 10.1242/jcs.093344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa F, de la Vega-Beltrán JL, López-González I, Delgado R, Labarca P, Darszon A. Mouse sperm patch-clamp recordings reveal single Cl− channels sensitive to niflumic acid, a blocker of the sperm acrosome reaction. FEBS Lett. 1998;426:47–51. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00305-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito G, Jaiswal BS, Xie F, Krajnc-Franken MA, Robben TJ, Strik AM, Kuil C, Philipsen RL, Van Duin M, Conti M, Gossen JA. Mice deficient for soluble adenylyl cyclase are infertile because of a severe sperm-motility defect. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:2993–2998. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400050101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French PJ, van Doorninck JH, Peters RH, Verbeek E, Ameen NA, Marino CR, de Jonge HR, Bijman J, Scholte BJ. A delta F508 mutation in mouse cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator results in a temperature-sensitive processing defect in vivo. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:1304–1312. doi: 10.1172/JCI118917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadsby DC, Nairn AC. Control of CFTR channel gating by phosphorylation and nucleotide hydrolysis. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:S77–S107. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.1.S77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galietta LJ. The TMEM16 protein family: a new class of chloride channels? Biophys. 2009;J97:3047–3053. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong XD, Li JC, Cheung KH, Leung GP, Chew SB, Wong PY. Expression of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator in rat spermatids: implication for the site of action of antispermatogenic agents. Mol Hum Reprod. 2001;7:705–713. doi: 10.1093/molehr/7.8.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guggino WB, Stanton BA. New insights into cystic fibrosis: molecular switches that regulate CFTR. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:426–436. doi: 10.1038/nrm1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartzell C, Putzier I, Arreola J. Calcium-activated chloride channels. Annu Rev Physiol. 2005;67:719–758. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.67.032003.154341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess KC, Jones BH, Marquez B, Chen Y, Ord TS, Kamenetsky M, Miyamoto C, Zippin JH, Kopf GS, Suarez SS, Levin LR, Williams CJ, Buck J, Moss SB. The ‘‘soluble’’ adenylyl cyclase in sperm mediates multiple signaling events required for fertilization. Dev Cell. 2005;9:249–259. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Gonzalez EO, Sosnik J, Edwards J, Acevedo JJ, Mendoza-Lujambio I, Lopez-Gonzalez I, Demarco I, Wertheimer E, Darszon A, Visconti PE. Sodium and epithelial sodium channels participate in the regulation of the capacitation-associated hyperpolarization in mouse sperm. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:5623–5633. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508172200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Gonzalez EO, Treviño CL, Castellano LE, de la Vega-Beltrán JL, Ocampo AY, Wertheimer E, Visconti PE, Darszon A. Involvement of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator in mouse sperm capacitation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:24397–24406. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701603200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins CF, Linton KJ. The ATP switch model for ABC transporters. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:918–926. doi: 10.1038/nsmb836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland IB, Blinght MA. ABC-ATPases, adaptable energy generators fuelling transmembrane movement of a variety of molecules organisms from bacteria to humans. J Mol Biol. 1999;293:381–399. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang T-C, Nagel G, Nair AC, Gadsby DC. Regulation of the gating of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator Cl− channels by phosphorylation and ATP hydrolysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:4698–4702. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.4698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikuma M, Welsh MJ. Regulation of CFTR Cl− channel gating by ATP binding and hydrolysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:8675–8680. doi: 10.1073/pnas.140220597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiguro H, Steward MC, Naruse S, Ko SB, Goto H, Case RM, Kondo T, Yamamoto A. CFTR functions as a bicarbonate channel in pancreatic duct cells. J Gen Physiol. 2009;133:315–326. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200810122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaupp UB, Weyand I. Cell biology. A universal bicarbonate sensor. Science. 2000;289:559–560. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5479.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirichok Y, Lishko PV. Rediscovering Sperm Ion Channels with the Patch-Clamp Technique. Mol Hum Reprod. 2011;17:478–499. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gar044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krapf D, Arcelay E, Wertheimer EV, Sanjay A, Pilder SH, Salicioni AM, Visconti PE. Inhibition of Ser/Thr phosphatases induces capacitation-associated signaling in the presence of Src kinase inhibitors. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:7977–7985. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.085845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunzelmann K, Schreiber R, Nitschke R, Mall M. Control of epithelial Na+ conductance by the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Pflugers Arch. 2000;440:193–201. doi: 10.1007/s004240000255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansdell KA, Cai Z, Kidd JF, Sheppard DN. Two mechanisms of genistein inhibition of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator Cl− channels expressed in murine cell line. J Physiol. 2000;524:317–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00317.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Krishnamurthy PC, Penmatsa H, Marrs KL, Wang XQ, Zaccolo M, Jalink K, Li M, Nelson DJ, Schuetz JD, Naren AP. Spatiotemporal coupling of cAMP transporter to CFTR chloride channel function in the gut epithelia. Cell. 2007;131:940–951. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li CY, Jiang LY, Chen WY, Li K, Sheng HQ, Ni Y, Lu JX, Xu WX, Zhang SY, Shi QX. CFTR is essential for sperm fertilizing capacity and is correlated with sperm quality in humans. Hum Reprod. 2010;5:317–327. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lishko PV, Botchkina IL, Fedorenko A, Kirichok Y. Acid extrusion from human spermatozoa is mediated by flagellar voltage-gated proton channel. Cell. 2010;140:327–337. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lishko PV, Botchkina IL, Kirichok Y. Progesterone activates the principal Ca2+channel of human sperm. Nature. 2011;471:387–391. doi: 10.1038/nature09767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukacs GL, Verkman AS. CFTR: folding, misfolding and correcting the ΔF508 conformational defect. Trends Mol Med. 2011;18:81–91. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma T, Thiagarajah JR, Yang H, Sonawane ND, Folli C, Galietta LJ, Verkman AS. Thiazolidinone CFTR inhibitor identified by high-throughput screening blocks cholera toxin-induced intestinal fluid secretion. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:1651–1658. doi: 10.1172/JCI16112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-López P, Treviño CL, de la Vega-Beltrán JL, De Blas G, Monroy E, Beltrán C, Orta G, Gibbs GM, O'Bryan MK, Darszon A. TRPM8 in mouse sperm detects temperature changes and may influence the acrosome reaction. J Cell Physiol. 2011;226:1620–1631. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matchkov VV, Aalkjaer C, Nilsson H. A cyclic GMP-dependent calcium-activated chloride current in smooth-muscle cells from rat mesenteric resistance arteries. J Gen Physiol. 2004;123:121–134. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200308972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty NA, McDonough S, Cohen BN, Riordan JR, Davidson N, Lester HA. Voltage-dependent block of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator Cl- channel by two closely related arylaminobenzoates. J Gen Physiol. 1993;102:1–23. doi: 10.1085/jgp.102.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPartlin LA, Visconti PE, Bedford-Guaus SJ. Guanine-Nucleotide ExchangeFactors (RAPGEF3/RAPGEF4) Induce Sperm Membrane Depolarization and Acrosomal Exocytosis in Capacitated Stallion Sperm. Biol Reprod. 2011;85:179–188. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.110.085555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Garay C, De la Vega-Beltrán JL, Delgado R, Labarca P, Felix R, Darszon A. Inwardly rectifying K+ channels in spermatogenic cells: Functional expression and implication in sperm capacitation. Developmental Biology. 2001;234:261–274. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper AS, Large WA. Direct effect of Ca2+-calmodulin on cGMP-activated Ca2+-dependent Cl- channels in rat mesenteric artery myocytes. J Physiol. 2004;559:449–457. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.070045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulsen JH, Fischer, Illek B, Machen TE. Bicarbonate conductance and pH regulatory capability of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:5340–5344. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.12.5340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu Z, Wei RW, Hartzell HC. Characterization of Ca2+–activated Cl- currents in mouse kidney inner medullary collecting duct cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2003;285:F326–F335. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00034.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinton PM. Physiological basis of cystic fibrosis: a historical perspective. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:S3–S22. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.1.S3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren D, Xia J. Calcium signaling through CatSper channels in mammalian fertilization. Physiology (Bethesda) 2010;25:165–175. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00049.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riordan JR. Assembly of functional CFTR chloride channels. Annu Rev Physiol. 2005;67:701–718. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.67.032003.154107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riordan JR, Rommens JM, Kerm B-S, Alon N, Rozmahel R, Grzelczak Z, Zielenski J, Lok S, Plavsic N, Chou JL, Drumm ML, Iannuzzi MC, Collins FS, Tsui LC. Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: cloning and characterization of complementary DNA. Science. 1989;245:1066–1073. doi: 10.1126/science.2475911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salicioni AM, Platt MD, Wertheimer EV, Arcelay E, Allaire A, Sosnik J, Visconti PE. Signalling pathways involved in sperm capacitation. Soc Reprod Fertil. 2007;(Suppl 65):245–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santi CM, Martinez-Lopez P, de la Vega-Beltrán JL, Butler A, Alisio A, Darszon A, Salkoff L. The SLO3 sperm-specific potassium channel plays a vital role in male fertility. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:1041–1046. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber R, Hopf A, Mall M, Greger R, Kunzelmann K. The first nucleotide binding fold of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator is important for inhibition of the epithelial Na+ channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:5310–5315. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.5310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder BC, Cheng T, Jan YN, Jan LY. Expression cloning of TMEM16A as a calcium-activated chloride channel subunit. Cell. 2008;134:1019–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz BD, Singh AK, Devor DC, Bridges RJ. Pharmacology of CFTR chloride channel activity. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:S109–S144. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.1.S109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz S, Jakubiczka S, Kropf S, Nickel I, Muschke P, Kleinstein J. Increased frequency of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene mutations in infertile males. Fertil Steril. 2006;85:135–138. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.07.1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwiebert EM, Morales MM, Devidas S, Egan ME, Guggino WB. Chloride channel and chloride conductance regulator domains of CFTR, the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:2674–2679. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard DN, Welsh MJ. Structure and function of the CFTR chloride channel. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:S23–S45. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.1.S23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silber SJ. A modern view of male infertility. Reprod Fertil Dev. 1994;6:93–103. doi: 10.1071/rd9940093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strünker T, Goodwin N, Brenker C, Kashikar ND, Weyand I, Seifert R, Kaupp UB. The CatSper channel mediates progesterone-induced Ca2+ influx in human sperm. Nature. 2011;471:382–386. doi: 10.1038/nature09769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez S, Ho H-C. Hyperactivated motility in sperm. Reproduction in domestic animals. 2003;38:119–124. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0531.2003.00397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan SK, Agellon LB, Schick R. Identification and partial characterization of a domain in CFTR that may bind cyclic nucleotides directly. Curr Biol. 1995;5:1159–1167. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(95)00232-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taddei A, Folli C, Zegarra-Moran O, Fanen P, Verkman AS, Galietta LJ. Altered channel gating mechanism for CFTR inhibition by a high-affinity thiazolidinone blocker. FEBS Lett. 2004;558:52–56. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(04)00011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian Y, Kongsuphol P, Hug M, Ousingsawat J, Witzgall R, Schreiber R, Kunzelmann K. Calmodulin-dependent activation of the epithelial calcium-dependent chloride channel TMEM16A. FASEB J. 2011;25:1058–1068. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-166884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trezise AE, Linder CC, Grieger D, Thompson EW, Meunier H, Griswold MD, Buchwald M. CFTR expression is regulated during both the cycle of the seminiferous epithelium and the oestrous cycle of rodents. Nat Genet. 1993;3:157–164. doi: 10.1038/ng0293-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsumura T, Hazama A, Miyoshi T, Ueda S, Okada Y. Activation of cAMP-dependent Cl− currents in guinea-pig Paneth cells without relevant evidence for CFTR expression. J Physiol. 1998;512:765–777. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.765bd.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Doorninck JH, French PJ, Verbeek E, Peters RH, Morreau H, Bijman J, Scholte BJ. A mouse model for the cystic fibrosis delta F508 mutation. EMBO J. 1995;14:4403–4411. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00119.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visconti PE, Krapf D, de la Vega-Beltrán JL, Acevedo JJ, Darszon A. Ion channels, phosphorylation and mammalian sperm capacitation. Asian J Androl. 2011;13:395–405. doi: 10.1038/aja.2010.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F, Zeltwanger S, Yang IC, Nairn AC, Hwang TC. Actions of genistein on cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator channel gating. Evidence for two binding sites with opposite effects. J Gen Physiol. 1998;111:477–490. doi: 10.1085/jgp.111.3.477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh KB, Wang C. Effect of chloride channel blockers on the cardiac CFTR chloride and L-type calcium currents. Cardio vasc Res. 1996;391:3989. doi: 10.1016/0008-6363(96)00075-2. 32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wertheimer EV, Salicioni AM, Liu W, Trevino CL, Chavez J, Hernandez-Gonzalez EO, Darszon A, Visconti PE. Chloride is essential for capacitation and for the capacitation-associated increase in tyrosine phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:35539–35550. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804586200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilke M, Buijs-Offerman RM, Aarbiou J, Colledge WH, Sheppard DN, Touqui L, Bot A, Jorna H, de Jonge HR, Scholte BJ. Mouse models of cystic fibrosis: phenotypic analysis and research applications. J Cyst Fibros. 2011;(Suppl 2):S152–S171. doi: 10.1016/S1569-1993(11)60020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong PY. CFTR gene and male fertility. Mol Hum Reproduction. 1998;4:107–110. doi: 10.1093/molehr/4.2.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu WM, Shi QX, Chen WY, Zhou CX, Ni Y, Rowlands DK, Yi Liu G, Zhu H, Ma ZG, Wang XF, Chen ZH, Zhou SC, Dong HS, Zhang XH, Chung YW, Yuan YY, Yang WX, Chan HC. Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator is vital to sperm fertilizing capacity and male fertility. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:9816–9821. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609253104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang D, Shcheynikov N, Zeng W, Ohana E, So I, Ando H, Mizutani A, Mikoshiba K, Muallem S. IRBIT coordinates epithelial fluid and HCO3- secretion by stimulating the transporters pNBC1 and CFTR in the murine pancreatic duct. J Clin Invest. 2009;19:193–202. doi: 10.1172/JCI36983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagimachi R. In The Physiology of Reproduction. New York: Raven Press; 1994. p. 189. [Google Scholar]

- Yang D, Shcheynikov N, Zeng W, Ohana E, So I, Ando H, Mizutani A, Mikoshiba K, Muallem S. IRBIT coordinates epithelial fluid and HCO3 secretion by stimulating the transporters pNBC1 and CFTR in the murine pancreatic duct. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:193–202. doi: 10.1172/JCI36983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung CH, Barfield JP, Cooper TG. Chloride channels in physiological volume regulation of human spermatozoa. Biol Reprod. 2005;73:1057–1063. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.105.044123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Y, Oberdorf JA, Florman HM. pH regulation in mouse sperm: identification of Na(+)-, Cl(−)-, and HCO3(−)-dependent and arylaminobenzoate-dependent regulatory mechanisms and characterization of their roles in sperm capacitation. Dev Biol. 1996;173:510–520. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang ZR, Zeltwanger S, McCarty NA. Direct comparison of NPPB and DPC as probes of CFTR expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J Membr Biol. 2000;175:35–52. doi: 10.1007/s002320001053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng H, Liu W, Anderson LY, Jiang QX. Lipid-dependent gating of a voltage-gated potassium channel. Nat Commun. 2011;2:250. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.