Abstract

Background

Coronary microvascular dysfunction (CMD) is a prevalent and prognostically important finding in patients with symptoms suggestive of coronary artery disease (CAD). The relative extent to which CMD affects both genders is largely unknown.

Methods and Results

We investigated 405 men and 813 women referred for evaluation of suspected CAD with no previous history of CAD and no visual evidence of CAD on rest/stress positron emission tomography (PET) myocardial perfusion imaging. Coronary flow reserve (CFR) was quantified and CFR<2.0 used to define the presence of CMD. Major adverse cardiac events (MACE), including cardiac death, non-fatal myocardial infarction, late revascularization and hospitalization for heart failure, were assessed in blinded fashion over a median follow-up of 1.3 years (IQR 0.5–2.3 years). CMD was highly prevalent both in men and women (51% and 54%, respectively; P(Fisher exact test)=0.39; P(equivalence)=0.0002). Regardless of gender, CFR was a powerful incremental predictor of MACE (hazard ratio 0.80 [95% CI 0.75–086] per 10% increase in CFR; P<0.0001) and resulted in favorable net reclassification improvement (NRI=0.280 [95% CI 0.049–0.512]), after adjustment for clinical risk and ventricular function. In a subgroup (N=404; 307 female/97 male) without evidence of coronary artery calcification (CAC) on gated CT imaging, CMD was common in both genders, despite normal stress perfusion imaging and zero CAC (44% of men versus 48% of women; P(Fisher exact test)=0.56; P(equivalence)=0.041).

Conclusions

CMD is highly prevalent among at risk individuals and is associated with adverse outcomes regardless of gender. The high prevalence of CMD in both genders suggests that it may be a useful target for future therapeutic interventions.

Keywords: microcirculation, atherosclerosis, blood flow, sex, women

Introduction

Multiple studies have demonstrated that, compared to men, women generally have a lesser extent of both overt1 and subclinical coronary atherosclerosis2. Nonetheless, the Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) study demonstrated that even in the absence of obstructive coronary atherosclerosis, many women who present with chest pain have evidence of exercise-induced myocardial ischemia3 and coronary vasomotor dysfunction.4 This syndrome of angina without obstructive coronary atherosclerosis has been attributed to coronary microvascular dysfunction (CMD).5,6 Indeed, a number of studies have reported that abnormalities in the function and structure of the coronary microcirculation may occur in patients with risk factors who have no evidence of obstructive atherosclerosis.6 Although several studies have implicated a hormonal basis to CMD7,8, these results have been inconsistent.9,10 Importantly, recent studies have demonstrated that the presence of CMD in symptomatic women without overt atherosclerosis can be associated with increased risk of cardiovascular events.4,11 These observations, among others, have motivated and driven the development of gender-specific diagnostic and treatment guidelines for CAD risk mitigation in women.12 However, because most of these studies have not evaluated men in parallel, the extent to which this syndrome and its prognostic implications are limited to women remains unknown.

In the present study, we sought to compare the gender differences in the frequency and severity of CMD assessed non-invasively with positron emission tomography (PET), and determine its prognostic implications in a large cohort of patients without clinical evidence of obstructive CAD.

Methods

Study Sample

We evaluated men and women referred for clinically indicated rest/stress myocardial perfusion PET imaging at the Brigham & Women’s Hospital (Boston, MA) between January 1, 2006, and June 30, 2010.13 Patients with known CAD, history of myocardial infarction, coronary revascularization, heart transplantation or moderate or severe valvular disease were excluded. The study was approved by the Partners Healthcare Institutional Review Board and conducted in accordance with institutional guidelines.

PET Imaging

Patients were studied with a whole-body PET–computed tomography scanner (Discovery RX or STE LightSpeed 64, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI) in 2D mode using 1480–2200 MBq of 82Rubidium as a flow tracer at rest and stress as has been previously described.13 Maximal coronary vasodilation was achieved using dipyridamole (N=584), adenosine (N=96), regadenoson (N=482) or dobutamine (N=56), as clinically appropriate. PET images were evaluated semi-quantitatively to identify obstructive CAD.14 Scans with summed stress score <3 were considered normal. Hybrid factor analysis15 with a two-compartment tracer kinetic model and well-validated extraction model for 82Rubidium16 were used to quantify absolute myocardial blood flow (MBF) in ml/min/g of tissue and coronary flow reserve (CFR; stress/rest MBF). Corrected CFR, was computed by dividing the stress MBF by the corrected rest MBF, which accounts for differences in resting cardiac work (rest MBF / [rest heart rate * rest systolic blood pressure]) multiplied by 10,000).

Assessment of Outcomes

The primary outcome was the composite of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) including: death resulting from any cardiac cause, myocardial infarction, late revascularization (after 90 days) and admission for congestive heart failure. Outcomes were ascertained by a combination of public and institutional databases, death certificates, mail surveys and telephone calls and were blindly adjudicated by two cardiologists. Admissions for congestive heart failure were adjudicated on the basis of admission and discharge notes, echocardiography and chest x-ray reports and, where available, right heart catheterization results.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical significance was assessed with Wilcoxon tests, Fisher exact tests, and χ2 tests for continuous, dichotomous, and categorical variables, respectively. Two-sided values of P<0.05 were considered significant. We found that the distribution of observed CFR values differed significantly from normal (Shapiro Wilk test P<0.0001) but was well represented by a log-normal distribution (Shapiro-Wilk test P=0.19). Consequently, the natural log transformation was applied to CFR prior to analysis and inverse transformed for presentation and interpretation. CFR values are presented as the geometric mean with 95% confidence intervals. Comparisons for CFR were performed with t-tests with an underlying log-normal distribution. In order to exclude the possibility that clinically important differences in CFR between genders could exist, equivalence testing was performed using Schuirmann’s two one-sided tests approach17 with a pre-determined equivalence threshold <10% for relative difference in CFR with an underlying log-normal distribution. All statistical analyses were performed with SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Multivariable Modeling

In order to identify factors which independently contribute to CFR, we conducted a stepwise linear regression using the Schwarz-Bayes criterion to select the best model. In order to reduce right skew, the natural logarithm of CFR was used as the dependent variable. Independent predictors were selected in a stepwise fashion among 35 demographic, historical, hemodynamic and imaging variables including gender. Because gender was not identified by the selection procedure as an independent predictor, it was added to the best model.

Gender and an interaction between gender and MVD were added to Cox survival models incorporating a gender neutral modification of the Duke clinical risk score18 (a measure of pre-test risk of CAD which integrates age, gender, angina type, smoking, hyperlipidemia, diabetes and EKG findings), left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and CFR. The latter was transformed with the natural logarithm to reduce right skew and heteroscedasticity. Incremental improvement in model fit was assessed using the likelihood ratio test. Additional models incorporating interactions between CFR and gender were used to evaluate for effect modification. The global χ2 statistic and Schwarz-Bayes criterion were used to evaluate model fit. The c-index and relative integrated discrimination index (IDI) were used to evaluate improved risk discrimination. The relative IDI is defined as the IDI divided by the discrimination slope of the base model.19 Net reclassification improvement (NRI) was computed without categories and also using annual rates of 1% and 3% to define low, intermediate and high risk categories. In order to assess the impact of incomplete follow-up, the analysis was repeated with right point and multiple imputation methods (Supplement).

Subgroup Analysis

Because subclinical non obstructive atherosclerotic plaques may exist even among patients with normal stress myocardial perfusion imaging, we analyzed patients who also underwent gated computed tomography scans for calcium scoring and had zero coronary artery calcium scores (CAC=0) (Supplement). We also performed a similar subgroup analysis among those with significant coronary calcium (CAC>100) as these patients have the greatest likelihood of meaningful subclinical atherosclerosis.

Results

Study Cohort

During the study period, there were 1,470 patients (women: 947; men: 523) without known CAD, prior myocardial infarction, coronary revascularization, heart transplantation or moderate or greater severity valvular disease. Of these, 252 patients had abnormal stress myocardial perfusion scans, reflecting obstructive CAD (23% versus 14%, in men and women respectively, p=0.003) (Figure S1). The remaining 1,218 patients with normal scans by semi-quantitative visual analysis comprised the study cohort (Table 1). Women were slightly older, more likely to be Hispanic and non-white than men. Compared to men, women were also more frequently obese and hypertensive. However, women were less likely to use tobacco. Chest pain and dyspnea were also more frequent in women than men. The pre-test clinical risk based on the gender-neutral modified Duke clinical risk score18 was higher among women than men (35% versus 29%, respectively, p=0.007). Left ventricular ejection fractions were slightly higher among women, although were normal in both genders.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics by Gender

| Variable | Males (N=405) |

Females (N=813) |

P- Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age (y) | 61.2 [52.8–68.8] | 62.3 [54.1–71.6] | 0.06 |

| Hispanic | 42 (10.4) | 152 (18.7) | 0.0002 |

| Race | |||

| White | 250 (61.7) | 409 (50.3) | 0.0008 |

| Black | 70 (17.3) | 184 (22.6) | |

| Other/Unknown | 85 (21) | 220 (27.1) | |

| Risk Factors | |||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.9 [25.4–35] | 30.2 [25.4–37.1] | 0.08 |

| BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 | 172 (42.5) | 420 (51.7) | 0.003 |

| Hypertension | 279 (68.9) | 615 (75.6) | 0.01 |

| Dyslipidemia | 212 (52.3) | 451 (55.5) | 0.33 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 119 (29.4) | 244 (30) | 0.84 |

| Family history of CAD | 94 (23.2) | 228 (28) | 0.07 |

| Tobacco Use | 53 (13.1) | 68 (8.4) | 0.01 |

| Modified Duke Clinical Risk (%) | 29 [16–50] | 35 [18–56] | 0.007 |

| Medications | |||

| Aspirin | 203 (50.1) | 379 (46.6) | 0.27 |

| β-adrenergic Blockers | 182 (44.9) | 381 (46.9) | 0.54 |

| Cholesterol agents | 184 (45.4) | 384 (47.2) | 0.58 |

| Insulin | 43 (10.6) | 91 (11.2) | 0.85 |

| Oral hypoglycemics | 43 (10.6) | 90 (11.1) | 0.85 |

| Ca-channel blockers | 80 (19.8) | 175 (21.5) | 0.50 |

| ACE inhibitors | 129 (31.9) | 254 (31.2) | 0.84 |

| Nitrates | 23 (5.7) | 37 (4.6) | 0.40 |

| Diuretics | 97 (24) | 268 (33) | 0.001 |

| Symptoms & Test Indications | |||

| Chest Pain | 166 (41.0) | 488 (60.0) | <0.0001 |

| Dyspnea | 97 (24) | 245 (30.1) | 0.03 |

| Pre-operative | 79 (19.5) | 105 (12.9) | 0.003 |

| Other | 30 (7.5) | 71 (8.7) | 0.51 |

| Chest Pain Characteristics | |||

| Typical Angina | 21 (5.2) | 76 (9.3) | 0.01 |

| Atypical Angina | 26 (6.4) | 66 (8.1) | 0.36 |

| Non-Anginal Chest Pain | 119 (29.4) | 346 (42.6) | <0.0001 |

| Imaging Findings | |||

| Rest LVEF (%) | 59 [53–63] | 65 [59–70] | <0.0001 |

| LVEF reserve>0 | 353 (87.2) | 707 (87) | 1.00 |

| Coronary Artery Calcium Score (N=898) | 37.5 [0–378] | 0 [0–112] | <0.0001 |

| Stress MBF (ml/g/min) | 1.85 [1.3–2.51] | 2.38 [1.82–3.14] | <0.0001 |

| Rest MBF (ml/g/min) | 0.92 [0.75–1.17] | 1.2 [0.95–1.53] | <0.0001 |

| Corrected Rest MBF (ml/g/min) | 0.92 [0.69–1.27] | 1.22 [0.9–1.77] | <0.0001 |

| CFR | 1.97 [1.51–2.49] | 1.94 [1.54–2.44] | 0.73 |

| Corrected CFR | 1.91 [1.39–2.64] | 1.81 [1.36–2.52] | 0.16 |

| Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction (CFR<2.0) | 206 (50.9) | 435 (53.5) | 0.39 |

Clinical and imaging characteristics of patients included in this study by gender. Corrected rest myocardial blood flow (MBF) is computed by multiplying by the rest rate-pressure product/10000. Coronary flow reserve (CFR) is computed as the ratio of stress/rest MBF. Continuous variables are presented as median with inter-quartile range. Binary variables are presented as absolute numbers and percentages. Comparisons across gender were performed using Wilcoxon, Fisher exact and chi-square tests for continuous, binary and categorical variables, respectively.

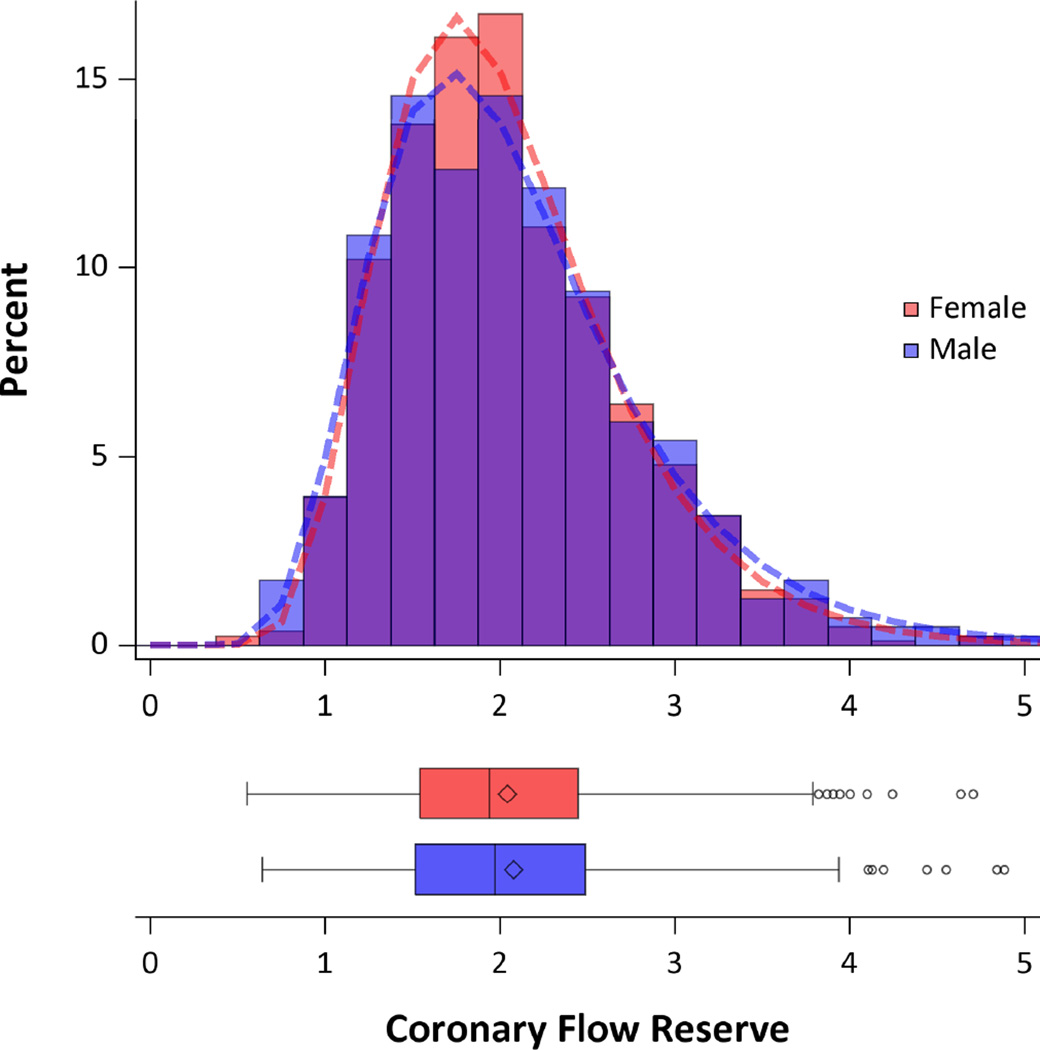

Coronary Vasomotor Function and Frequency of Microvascular Dysfunction

Compared to men, women showed higher myocardial blood flow both at rest (0.92 [IQR 0.75–1.17] versus 1.2 [IQR 0.95–1.53] mL/min/g, respectively, p<0.0001) and during peak stress (1.85 [IQR 1.3–2.51] versus 2.38 [IQR 1.82–3.14] mL/min/g, respectively, p<0.0001) (Table 1). CFR was similar in men and women (1.95 [95%CI 1.88–2.02] versus 1.94 [95% CI 1.89–1.98], respectively; P(t-test)=0.73; P(equivalence)<0.0001) (Figure 1). This did not change even after correcting the rest MBF by the rest rate-pressure product, an index of cardiac work (Table 1). The frequency of CFR<2.0, reflecting primarily CMD, was high and similar in men (N=206, 51%) and women (N=435, 54%; P(Fisher exact test)=0.39 and P(equivalence)=0.0002; Figure S1).

Figure 1.

Distribution of Coronary Flow Reserve by Gender. Histogram (top) showing the distribution of coronary flow reserve for men (blue) and women (red). Areas of overlap are shown in purple. Fitted log-normal distribution for men (dashed blue line) and women (dashed red line) are also displayed. Similar data are also shown in box plots (bottom). No statistically significant difference was seen between genders using t-test with log-normal distribution (P=0.73). CFR was equivalent between the genders (P=0.0005 for <10% difference) using two one-sided tests and log-normal distribution.

Among those patients with typical or atypical angina and/or dyspnea (N=471; 341 women and 130 men), CFR was not significantly different compared to those with non-cardiac chest pain or without symptoms (1.93 [95%CI 1.87–1.99] versus 1.95 [95%CI 1.90–2.00]; P(t-test)=0.63; P(equivalence)<0.0001). This is not surprising given that these patients lacked evidence of overt myocardial ischemia on visual examination of stress perfusion images. However, even within this symptomatic group, no differences in CFR between men and women were found (1.95 [95%CI 1.83–2.08] versus 1.92 [95%CI 1.86–1.99]; P(t-test)=0.69; P(equivalence)=0.01). Stepwise multivariable linear regression analysis identified age, BMI, hypertension, diabetes, dialysis, evaluation for pre-operative risk stratification and LVEF reserve, but not gender or race, as independent predictors of corrected CFR (Table S1, Model 1). Addition of gender to the best fitting model (Model 2) demonstrated that gender per se was not informative to the model. Because corrected CFR may be more useful for characterization of sample population group behavior rather than individual patient values, we performed a similar analysis for CFR without correction by rate-pressure product with similar results.

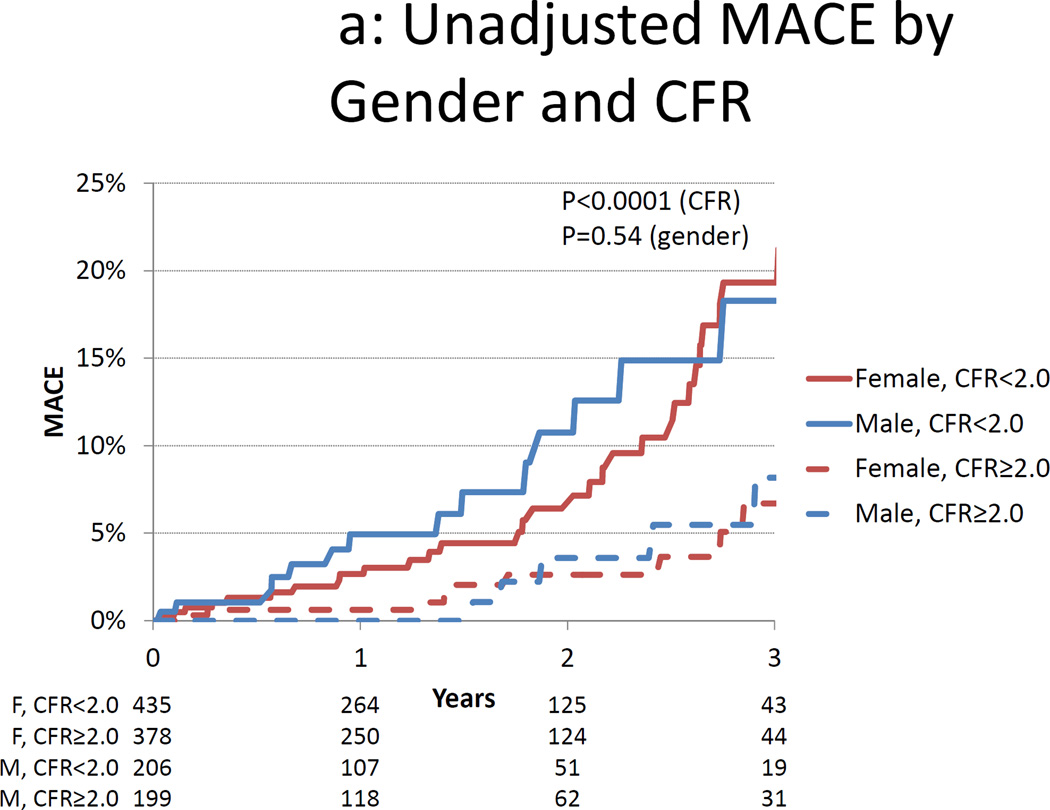

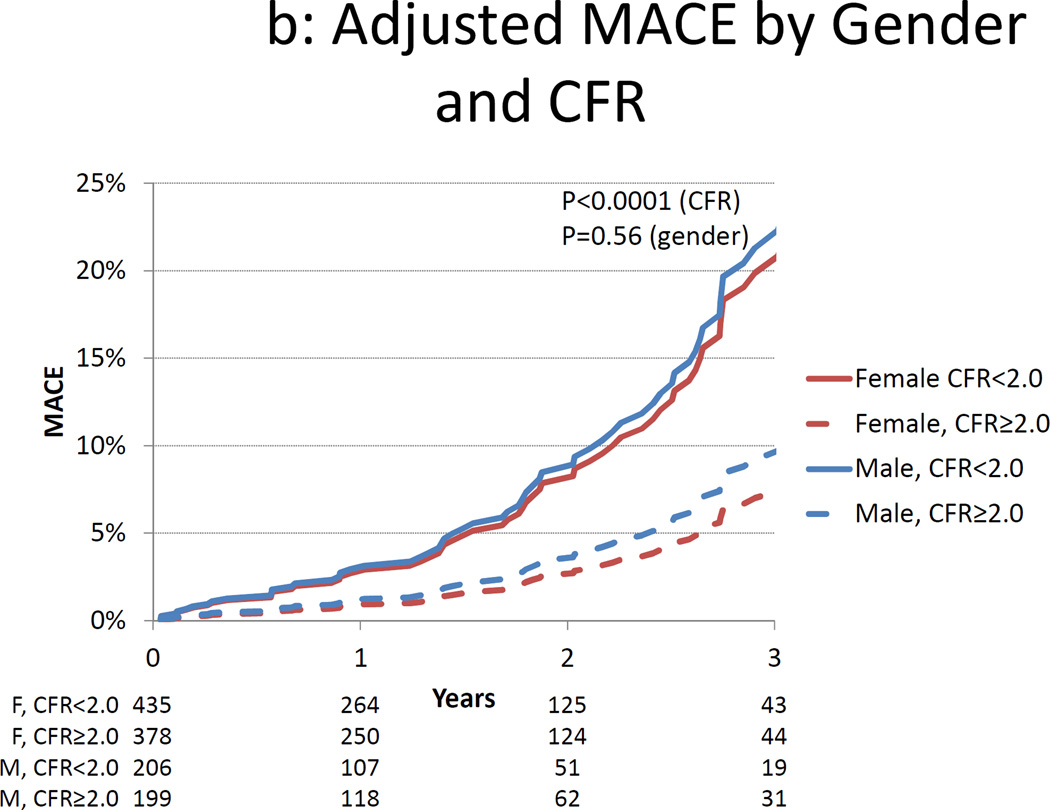

Clinical Outcomes

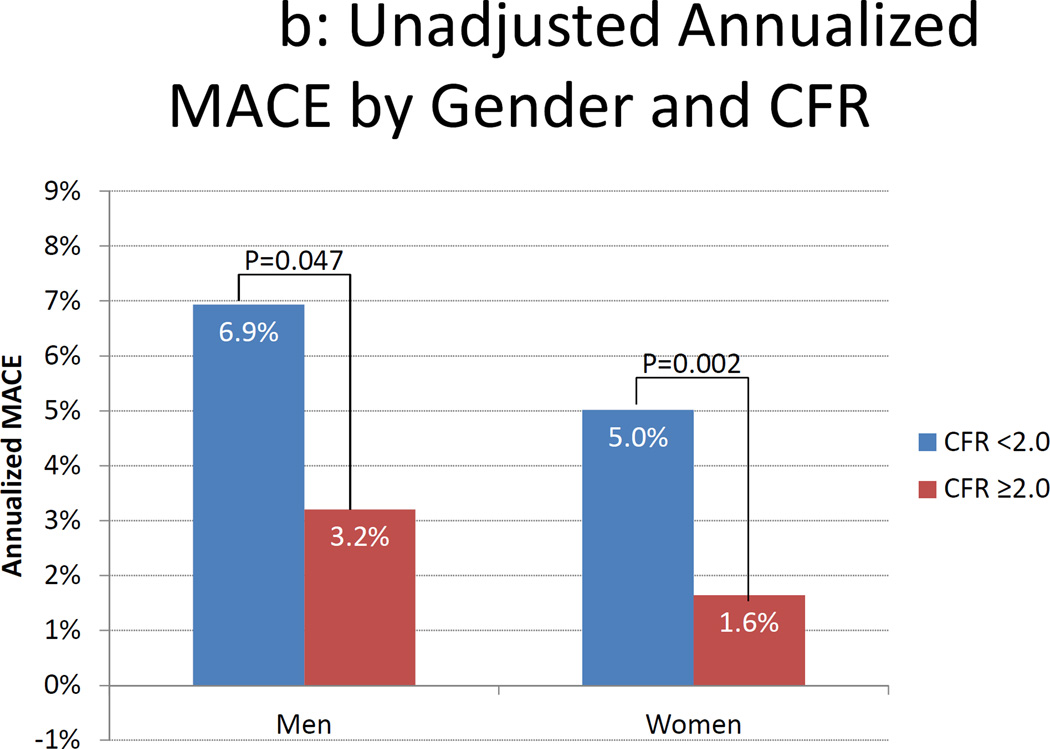

During the median follow-up of 1.3 years (IQR 0.5–2.3 years), a total of 75 first-MACE events occurred (Table 2). MACE occurred earlier and more frequently among both men and women with CMD than those without (Figures 2 and 3). In survival analysis (Table 3), the modified Duke clinical risk score (HR 1.06 [95%CI 1.03–1.1]; P= 0.0007) and rest LVEF (each 10% increase, HR 0.56 [95%CI 0.44–0.72]; P< 0.0001) were significantly associated with MACE. CFR provided incremental prognostic information (increase in global χ2 from 35.5 to 74.9, p<0.0001) and was significantly associated with MACE (HR 0.80 [95%CI 0.75–0.86] for each 10% increase; P<0.0001). Of note, gender was not associated with MACE (HR 0.90 [95%CI 0.55–1.45]; P=0.65). Further, referral for evaluation of symptoms (i.e. either chest pain or dyspnea) was not related to MACE (P=0.43).

Table 2.

Clinical Outcomes by CFR and Gender

| Outcome | CFR <2.0 (N=641) |

CFR ≥2.0 (N=577) |

All Subjects (N=1218) |

P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MACE | 55 (8.6) | 20 (3.5) | 75 (6.2) | 0.0002 |

| Death | 32 (5) | 13 (2.3) | 45 (3.7) | 0.01 |

| Cardiac Death | 12 (1.9) | 1 (0.2) | 13 (1.1) | 0.004 |

| Myocardial Infarction | 27 (4.2) | 8 (1.4) | 35 (2.9) | 0.003 |

| Late Revascularization | 10 (1.6) | 7 (1.2) | 17 (1.4) | 0.63 |

| Heart Failure Admission | 27 (4.2) | 12 (2.1) | 39 (3.2) | 0.05 |

| Outcome |

Males (N=405) |

Females (N=813) |

All Subjects (N=1218) |

P-Value |

| MACE | 30 (7.4) | 45 (5.5) | 75 (6.2) | 0.21 |

| Death | 22 (5.4) | 23 (2.8) | 45 (3.7) | 0.03 |

| Cardiac Death | 5 (1.2) | 8 (1) | 13 (1.1) | 0.77 |

| Myocardial Infarction | 13 (3.2) | 22 (2.7) | 35 (2.9) | 0.59 |

| Late Revascularization | 12 (3) | 5 (0.6) | 17 (1.4) | 0.003 |

| Heart Failure Admission | 14 (3.5) | 25 (3.1) | 39 (3.2) | 0.73 |

Major adverse cardiac outcomes (MACE) indicates the composite of death resulting from any cardiac cause, myocardial infarction, late revascularization (after 90 days) and admission for congestive heart failure. P-values were computed with Fisher’s exact test.

Figure 2.

Cumulative Incidence of MACE by Gender and Coronary Flow Reserve. Unadjusted (panel A) and adjusted (panel B) cumulative rate of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) by gender and coronary flow reserve (CFR). Data in panel B are adjusted for the modified Duke clinical risk score18 and rest LVEF.

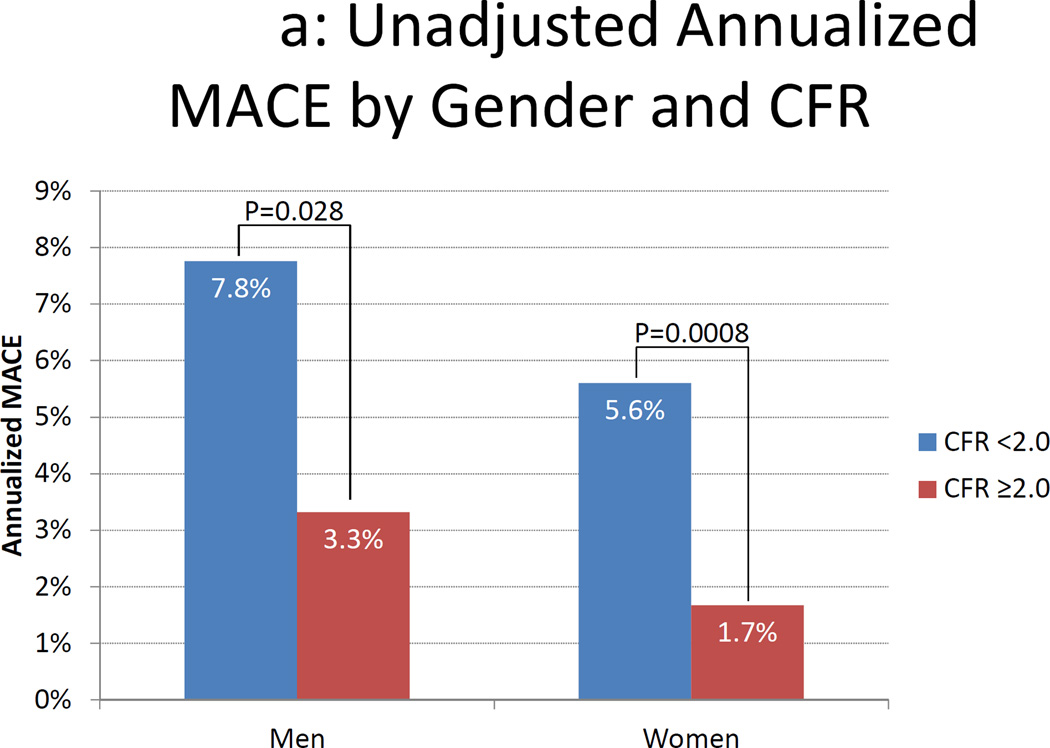

Figure 3.

Annualized MACE Rates by Gender and Coronary Flow Reserve. Unadjusted (panel A) and adjusted (panel B) annualized major adverse cardiac events (MACE) rate by gender and coronary flow reserve (CFR). Data in panel B are adjusted for the modified Duke clinical risk score18. Rates are computed as the number of first MACE events divided by the number of person-years of follow-up in each subgroup. Comparisons were made using Poisson regression.

Table 3.

Multivariable Cox Regression for MACE

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fit Statistic | Estimate | P- Value |

Estimate | P- Value |

Estimate | P- Value |

Estimate | P- Value |

| Global χ2 | 35.498 | ref | 74.9 | <0.0001 | 75.1 | 0.66 | 75.6 | 0.42 |

| AIC | 822.065 | ref | 784.7 | <0.0001 | 786.5 | 1.00 | 786.0 | 1.00 |

| SBC | 826.7 | ref | 791.6 | <0.0001 | 795.7 | 1.00 | 795.3 | 1.00 |

| C-Index | 0.646 [0.557–0.735] |

ref | 0.723 [0.638–0.808] |

0.01 | 0.721 [0.636–0.806] |

0.43 | 0.719 [0.633–0.805 |

0.36 |

| Continuous NRI | ref | N/A | 0.627 [0.265–0.982] |

P<0.05 | 0.160 [–0.187–0.521] |

P>0.05 | 0.322 [−0.048– 0.682] |

P>0.05 |

| Categorical NRI | ref | N/A | 0.280 [0.049–0.512] |

P<0.05 | −0.027 [−0.082– 0.003] |

P>0.05 | −0.031 [−0.093–0.002] |

P>0.05 |

| Relative IDI | ref | N/A | 2.4016 [1.618–3.350] |

P<0.05 | 0.009 [−0.010–0.028] |

P>0.05 | 0.000 [−0.003–0.002] |

P>0.05 |

| Variable |

Hazard Ratio |

P- Value |

Hazard Ratio |

P- Value |

Hazard Ratio |

P- Value |

Hazard Ratio |

P- Value |

| Clinical Risk (per 10% increase) | 1.07 [1.03–1.10]] |

<0.0001 | 1.06 [1.03–1.10] |

0.0007 | 1.06 [1.03–1.10] |

0.0008 | 1.06 [1.03–1.10] |

0.0008 |

| Rest LVEF (per 10% increase) | 0.56 [0.44–0.72] |

<0.0001 | 0.56 [0.44–0.72] |

<0.0001 | 0.57 [0.44–0.74] |

<0.0001 | 0.57 [0.45–0.74] |

<0.0001 |

| ln(CFR) (per 10% increase) | 0.80 [0.75–0.86] |

<0.0001 | 0.80 [0.75–0.86] |

<0.0001 | 0.79 [0.73–0.85] |

<0.0001 | ||

| Female Gender | 0.90 [0.55–1.45] |

0.65 | ||||||

| Gender*ln(CFR) Interaction | ||||||||

| Female (per 10% increase in CFR) | 0.79 [0.73–0.85] |

0.42 (women vs. men) | ||||||

| Male (per 10% increase in CFR) | 0.82 [0.76–0.88] |

|||||||

Values in square brackets indicate 95% confidence intervals. MACE indicates Major Adverse Cardiac Events. SBC indicates Schwarz-Bayes Criteria. AIC indicates Akaike’s information criterion. NRI indicates net reclassification improvement. Categorical NRI was computed with threshold rates of 1 and 3% per year to define low, intermediate and high risk categories. IDI indicates integrated discrimination index. NRI, IDI and P-values for fit statistics compare Model 1 vs. Model 0, Model 2 vs. Model 1, Model 3 vs. Model 2, and Model 4 vs. Model 2, respectively. C-index, NRI and relative IDI are computed at two years. Clinical risk indicates the Duke clinical risk score18 modified to be gender neutral. CFR indicates coronary flow reserve without correction for rate-pressure product. LVEF indicates left ventricular ejection fraction.

An interaction term between gender and CFR was also not statistically significant (P=0.42), indicating that there is no effect modification by gender on CFR (Table 3). Further, addition of CFR improved both risk discrimination and reclassification, with statistically meaningful increases in c-index, IDI and NRI. Analysis of men and women separately suggested the magnitude of the effect of CFR on MACE was similar for both genders (Table 4), although NRI was not statistically significant for men, possibly due to sample size limitations. Because revascularization can reflect both clinical worsening and a combination of patient and provider preferences, we repeated this analysis excluding revascularization from the outcome with similar results. Of note, gender remained non-informative for MACE (P=0.78) as did interaction terms between gender and CFR (P=0.95). Finally, we found the rate of MACE increased monotonically with progressively decreasing CFR for both genders (Figure S2).

Table 4.

Comparison of Relationship between CFR and MACE for Men and Women

| Women (N=813) | Men (N=405) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value [95% CI] | P-Value | Value [95% CI] | P-Value | |

| Adjusted Hazard Ratio (10% increase) |

0.795 [0.730–0.865] |

<0.0001 | 0.809 [0.725–0.903] |

0.0002 |

| C-Index | 0.716 [0.613–0.819] |

0.12 | 0.741 [0.607–0.876] |

0.049 |

| Relative IDI | 2.430 [1.449, 3.81] |

P<0.05 | 3.190 [1.828–5.022] |

P<0.05 |

| Continuous NRI | 0.685 [0.215–1.108] |

P<0.05 | 0.501 [−0.083–1.085] |

P>0.05 |

| Categorical NRI | 0.379 [0.053–0.718] |

P<0.05 | 0.067 [–0.206–0.354] |

P>0.05 |

95% CI indicates 95% confidence interval. IDI indicates integrated discrimination improvement. NRI indicates net reclassification improvement. Categorical NRI was computed with threshold rates of 1 and 3% per year to define low, intermediate and high risk categories. C-index, NRI and IDI were computed at two years.

Because of incomplete follow-up (follow-up was 94% complete), we conducted several sensitivity analyses, which yielded comparable results (Supplement and Table S2). Finally, we also performed survival analysis for men and women separately and found similar results (Table 4). However, NRI was not statistically significant among men, perhaps due to limited sample size.

Subgroup without Coronary Artery Calcium

Because subclinical atherosclerosis and, very rarely, obstructive CAD may exist even in the presence of normal myocardial perfusion imaging, we also evaluated the subgroup (N=404; 307 female and 97 male) who also had no coronary artery calcification (CAC=0) on gated CT imaging (Supplement and Table S3). Among these individuals without evidence of hemodynamically significant epicardial stenoses or even calcific subclinical plaques, CMD was common in both genders, despite normal stress perfusion imaging and zero CAC (44% of men versus 48% of women; P(Fisher exact test)=0.56; P(equivalence)=0.041). Even among those with a CAC score of zero, CFR was equivalent across genders (2.03 [95%CI 1.95–2.11] for women versus 2.03 [1.89–2.19] for men; P(t-test)=0.93; P(equivalence)=0.01) (Figure S3). Similarly, gender did not improve linear regression models for prediction of CFR (P=0.88) (Table S4).

Even among the subgroup with CAC=0, CFR remained significantly associated with MACE (Figure S4) (HR 0.82 [95%CI 0.72–0.93] per 10% increase; p=0.0001), similar in magnitude to that in the overall cohort. Gender was not a significant predictor of MACE in Cox regression models adjusting for clinical risk and LVEF (HR 0.78 [95%CI 0.24–2.59]; p=0.69) (Tables S5 & S6). Finally, no statistically significant interaction between gender and CFR was found in Cox regression analysis for MACE (p=0.32), confirming that the effect of CFR on outcomes is similar regardless of gender.

Subgroup with Significant Coronary Artery Calcium

In order to further characterize the additive effect of CMD beyond anatomic measures of CAD, we also evaluated the subgroup with CAC>100 (N=280; 121 male and 159 female) (Supplement and Table S7). Rates of CMD were high among both genders and were similar (58% of men and 63% of women; P(Fisher exact test)=0.54; P(equivalence)=0.18). CFR was similar across genders (1.79 [95%CI 1.71–1.88] for women versus 1.83 [1.72–1.96] for men; P(t-test)=0.56; P(equivalence)=0.037) (Figure S5). In this subgroup, male gender was associated with a higher CFR than female gender (difference of 0.28 [95% CI 0.08–0.47]; P=0.006) (Table S8).

However, even in the presence of anatomic evidence of subclinical CAD, CFR remained significantly associated with MACE (Figure S6) (HR 0.83 [95%CI 0.74–0.94] per 10% increase; p=0.01), similar in magnitude to that in the overall cohort and those with CAC=0. Gender was not a significant predictor of MACE in Cox regression models adjusting for clinical risk and LVEF (HR 0.84 [95%CI 0.39–1.78]; p=0.64) (Tables S9 & S10). Finally, as for the overall cohort and those with CAC=0, no statistically significant interaction between gender and CFR was found in Cox regression analysis for MACE (p=0.26), again confirming that the effect of CFR on outcomes is similar regardless of gender.

Discussion

We have demonstrated that although men are more likely than women to have imaging evidence of obstructive CAD, women and men are equally likely to have CMD as a manifestation of preclinical coronary atherosclerosis. In line with previous studies, we found that the severity of CMD is associated with older age and the burden of coronary risk factors including hypertension, diabetes, and obesity. More importantly, we found that the presence of CMD increases the risk of adverse events irrespective of gender. Collectively, these findings suggest that CMD is not uniquely a female disorder.

Several small studies have previously demonstrated that CFR as an index of microvascular function is similar between men and women20–23. Rosen and colleagues evaluated 29 subjects with chest pain with normal coronary arteries and demonstrated using 15O-water and PET that although men had lower hyperemic blood flows than women, gender was not a predictor of coronary vasodilator capacity20. Likewise, using similar methodology Danad and colleagues demonstrated among 173 subjects without obstructive CAD that although male gender was associated with a lower maximal hyperemic blood flow, CFR was not dependent on gender23. The current study confirms these results in a much larger population and, notably, it links these findings to clinical outcomes.

The mechanisms underlying the observed differences in coronary vascular reactivity are likely to be multi-factorial. Vasomotor tone has been shown to be lower in coronary arteries in females than in males, which may in part be due to sex hormone effects24,25, although other mechanisms have also been implicated including gender-related differences in autonomic regulation26,27 and in responses to oxidative stress28, adenosine29, endothelin-130, angiotensin II31, among other stimuli.32 Risk factors such as diabetes, hypertension and dyslipidemia were highly prevalent among both genders in our study sample. These risk factors are well known to contribute to coronary vasomotor dysfunction among both genders6,33, mirroring the equally high prevalence of significantly reduced CFR (<2.0) in both genders.

Finally, in patients with multiple risk factors, CMD may be a manifestation of low-grade systemic inflammation, and may precede the florid intimal thickening and lipid deposition which characterize high-risk epicardial coronary atherosclerosis. Indeed, in patients with exertional angina and ST-segment depression on exercise stress testing, but normal coronary angiograms, only those with elevated high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP, >3 mg/L) have reduced CFR34. Among patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome and non-obstructive CAD by angiography, reduced CFR (assessed by invasive Doppler flow velocity monitoring) was associated with more thin-cap fibroatheroma, greater plaque burden and higher levels of hsCRP, despite a similar burden of epicardial disease.35

Another interesting finding of this study is that among patients with multiple coronary risk factors, there does not appear to be a clear cut relationship between symptoms (angina and dyspnea) and CMD. Kaski and colleagues have shown that epicardial coronary vasomotion is similar in patients with microvascular dysfunction and those with non-cardiac chest pain.36 Indeed, MBF at rest and during pharmacological stress may be similar in patients with cardiac syndrome X compared to healthy controls without coronary disease or cardiac risk factors34. Furthermore, the manifestations of discomfort related to myocardial ischemia are highly variable37 and may vary by gender38.

Our study has several inherent limitations. Coronary angiography was not a part of the standard evaluation of these patients, because it would be unjustified based on the absence of objective clinical evidence of obstructive CAD. Indeed, subjecting patients with normal stress testing to systematic invasive angiography would be ethically challenging and face difficult recruitment. Importantly, we confirmed our findings in the subgroup of patients who had no evidence of coronary artery calcium. These patients, with normal stress perfusion imaging and no coronary calcium are very unlikely to have obstructive CAD by conventional invasive angiography. Although the generalizability of PET measures of CFR to routine clinical practice has not yet been fully established, reproducibility of CFR measurements using several largely automated, FDA-approved software packages suggest this is unlikely to be a major hurdle39–41.

This study is a single center, retrospective study and subject to all of the limitations of this study design. Nevertheless, we believe that our study sample is reflective of those referred for evaluation of suspected CAD in many, if not most, large centers, which enhances its clinical relevance, generalizability, and translation to clinical practice. Further, because of limitations of sample size, we were only able to adjust for a limited number of potential confounding variables in survival analyses. Consequently, the impact of these potentially important factors on outcomes was not evaluated.

Additionally, the rate of loss to follow-up was comparable to the rate of MACE. We performed several sensitivity analyses and found that the results were robust. Nonetheless, the number of outcome events in several subgroup analyses is small and should be interpreted with caution. Finally, although this observational study adds to the growing body of literature suggesting a potential diagnostic and prognostic role of CFR, it does not establish a management role for coronary flow reserve. Nonetheless, findings of this study may be helpful in the design of prospective, randomized trials designed to test whether medical or other treatments for patients with CFR below specific thresholds are associated with improved outcomes.

Despite these limitations, our finding that CMD is highly prevalent among members of both genders, even in the absence of obstructive CAD, confirms findings of the WISE study4,42 and extends these observations to men. Similarly, our observation of a higher rate of adverse outcomes in both genders with impaired microvascular function also confirms findings of the WISE study and extends them to men.4,11 Importantly, the prognostic importance of CMD was seen despite a study cohort in which all subjects had normal stress PET testing and would be expected to have a favorable prognosis of <1% annual rate of cardiac death or myocardial infarction based on many prior studies.43 Indeed, similar findings were noted even among those without evidence of coronary artery calcification, a subgroup which would be expected to have even lower risk of adverse events.44 Those with CMD had elevated rates of cardiac mortality, overall mortality (including from non-cardiac causes), myocardial infarction and heart failure. The broad impact of CFR on outcomes suggests that it may be not only a marker of coronary physiology but also a marker of vascular and overall health. Consequently, traditional testing modalities, namely stress testing and coronary calcium testing, may miss large numbers of both men and women at risk of adverse events. These findings also identify CMD as a prognostically-relevant potential target for therapy in patients at particularly high clinical risk in need of aggressive therapeutic intervention45.

Conclusions

Manifestations of CAD differ between men and women. Consistent with prior studies, myocardial infarction and overt stress-induced ischemia are more common among men. Coronary vasomotor dysfunction is highly and equally prevalent among women and men with risk factors and symptoms consistent with CAD even in the absence of overt coronary atherosclerosis, suggesting that CMD is not a uniquely female disorder. More importantly, the presence of CMD identifies men and women at increased clinical risk.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Perspectives.

A large body of literature has demonstrated that men are more likely than women to have both overt and subclinical coronary atherosclerosis. The Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) study and others have shown that women who present with chest pain frequently exhibit coronary microvascular dysfunction (CMD). The extent to which this is exclusively or predominantly female disorder had been previously poorly studied. Using a cohort of patients referred for clinically indicated stress testing with positron emission tomography (PET) for the evaluation of suspected coronary disease who did not exhibit evidence of epicardial coronary stenosis based on the absence of regional perfusion defects, we demonstrate that the prevalence of CMD is similar among both men and women. Indeed, the coronary flow reserve (CFR) or ratio of stress/rest myocardial blood flow, was nearly identical across genders. Furthermore, the prognostic implications of CMD were similar across genders: in both cases, impaired CFR was associated with a markedly increased risk of major adverse cardiac events (MACE). These data suggest that CMD is a common disorder affecting approximately half of members of both genders referred for stress testing and that may be a target for future therapeutic studies.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: The study was funded in part by a training grant from the National Institutes of Health (T32 HL094301-01A1).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr. Murthy owns equity in General Electric and has received research support from INVIA Medical Imaging Solutions. Dr. Dorbala received research grant support from Astellas Global Pharma Development and Bracco Diagnostics. Dr. Blankstein received research grant support from Astellas Global Pharma Development. Dr. Camici is a consultant for Servier International.

References

- 1.Kennedy JW, Killip T, Fisher LDP, Alderman EL, Gillespie MJ, Mock MB., III The clinical spectrum of coronary artery disease and its surgical and medical management, 1974–1979. The Coronary Artery Surgery study. Circulation. 1982;66:16–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McClelland RL, Chung H, Detrano R, Post W, Kronmal RA. Distribution of coronary artery calcium by race, gender, and age: results from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Circulation. 2006;113:30–37. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.580696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson BD, Shaw LJ, Buchthal SD, Bairey Merz CN, Kim H-W, Scott KN, Doyle M, Olson MB, Pepine CJ, den Hollander J, Sharaf B, Rogers WJ, Mankad S, Forder JR, Kelsey SF, Pohost GM. Prognosis in women with myocardial ischemia in the absence of obstructive coronary disease: results from the National Institutes of Health-National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute-Sponsored Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) Circulation. 2004;109:2993–2999. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000130642.79868.B2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pepine CJ, Anderson RD, Sharaf BL, Reis SE, Smith KM, Handberg EM, Johnson BD, Sopko G, Bairey Merz CN. Coronary microvascular reactivity to adenosine predicts adverse outcome in women evaluated for suspected ischemia results from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute WISE (Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:2825–2832. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.01.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones E, Eteiba W, Merz NB. Cardiac Syndrome X and Microvascular Coronary Dysfunction. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2012;22:161–168. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2012.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Camici PG, Crea F. Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction. New Engl J oMed. 2007;356:830–840. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra061889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hirata K, Shimada K, Watanabe H, Muro T, Yoshiyama M, Takeuchi K, Hozumi T, Yoshikawa J. Modulation of coronary flow velocity reserve by gender, menstrual cycle and hormone replacement therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:1879–1884. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01658-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campisi R, Nathan L, Pampaloni MH, Schöder H, Sayre JW, Chaudhuri G, Schelbert HR. Noninvasive assessment of coronary microcirculatory function in postmenopausal women and effects of short-term and long-term estrogen administration. Circulation. 2002;105:425–430. doi: 10.1161/hc0402.102860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duvernoy C, Martin J, Briesmiester K, Bargardi A, Muzik O, Mosca L. Myocardial blood flow and flow reserve in response to hormone therapy in postmenopausal women with risk factors for coronary disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:2783–2788. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwitter J, Kozerke S, Bremerich J, Baltes C, Attenhofer Jost C, Birkhäuser M, Boesiger P, Buser P. Oral administration of 17beta-estradiol over 3 months without progestin co-administration does not improve coronary flow reserve in post-menopausal women: a randomized placebo-controlled cross-over CMR study. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2007;9:665–672. doi: 10.1080/10976640601138730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doyle M, Weinberg N, Pohost GM, Bairey Merz CN, Shaw LJ, Sopko G, Fuisz A, Rogers WJ, Walsh EG, Johnson BD, Sharaf BL, Pepine CJ, Mankad S, Reis SE, Vido DA, Rayarao G, Bittner V, Tauxe L, Olson MB, Kelsey SF, Biederman RWW. Prognostic value of global MR myocardial perfusion imaging in women with suspected myocardial ischemia and no obstructive coronary disease: results from the NHLBI-sponsored WISE (Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation) study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010;3:1030–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mosca L, Benjamin EJ, Berra K, Bezanson JL, Dolor RJ, Lloyd-Jones DM, Newby LK, Piña IL, Roger VL, Shaw LJ, Zhao D, Beckie TM, Bushnell C, D’Armiento J, Kris-Etherton PM, Fang J, Ganiats TG, Gomes AS, Gracia CR, Haan CK, Jackson EA, Judelson DR, Kelepouris E, Lavie CJ, Moore A, Nussmeier NA, Ofili E, Oparil S, Ouyang P, Pinn VW, Sherif K, Smith SC, Sopko G, Chandra-Strobos N, Urbina EM, Vaccarino V, Wenger NK. Effectiveness-Based Guidelines for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in Women—2011 Update. Circulation. 2011;123:1243–1262. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31820faaf8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murthy VL, Naya M, Foster CR, Hainer J, Gaber M, Di Carli G, Blankstein R, Dorbala S, Sitek A, Pencina MJ, Di Carli MF. Improved cardiac risk assessment with noninvasive measures of coronary flow reserve. Circulation. 2011;124:2215–2224. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.050427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cerqueira MD, Weissman NJ, Dilsizian V, Jacobs AK, Kaul S, Laskey WK, Pennell DJ, Rumberger JA, Ryan T, Verani MS. Standardized Myocardial Segmentation and Nomenclature for Tomographic Imaging of the Heart: A Statement for Healthcare Professionals From the Cardiac Imaging Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology of the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2002;105:539–542. doi: 10.1161/hc0402.102975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sitek A, Gullberg GT, Huesman RH. Correction for ambiguous solutions in factor analysis using a penalized least squares objective. Medical Imaging, IEEE Transactions on. 2002;21:216–225. doi: 10.1109/42.996340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoshida K, Mullani N, Gould KL. Coronary Flow and Flow Reserve by PET Simplified for Clinical Applications Using Rubidium-82 or Nitrogen-13-Ammonia. J Nucl Med. 1996;37:1701–1712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schuirmann DJ. A comparison of the two one-sided tests procedure and the power approach for assessing the equivalence of average bioavailability. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm. 1987;15:657–680. doi: 10.1007/BF01068419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pryor DB, Shaw L, McCants CB, Lee KL, Mark DB, Harrell FE, Muhlbaier LH, Califf RM. Value of the History and Physical in Identifying Patients at Increased Risk for Coronary Artery Disease. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118:81–90. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-118-2-199301150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pencina MJ, D’ Agostino Sr RB, D’ Agostino RB, Jr., Vasan RS. Evaluating the added predictive ability of a new marker: From area under the ROC curve to reclassification and beyond. Stat Med. 2008;27:157–172. doi: 10.1002/sim.2929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosen S, Uren N, Kaski J, Tousoulis D, Davies G, Camici P. Coronary vasodilator reserve, pain perception, and sex in patients with syndrome X. Circulation. 1994;90:50–60. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chareonthaitawee P, Kaufmann PA, Rimoldi O, Camici PG. Heterogeneity of resting and hyperemic myocardial blood flow in healthy humans. Cardiovasc Res. 2001;50:151–161. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00202-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Danad I, Raijmakers PG, Appelman YE, Harms HJ, de Haan S, van den Oever MLP, van Kuijk C, Allaart CP, Hoekstra OS, Lammertsma AA, Lubberink M, van Rossum AC, Knaapen P. Coronary risk factors and myocardial blood flow in patients evaluated for coronary artery disease: a quantitative [15O]H2O PET/CT study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2012;39:102–112. doi: 10.1007/s00259-011-1956-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Danad I, Raijmakers PG, Appelman YE, Harms HJ, de Haan S, Marques KM, van Kuijk C, Allaart CP, Hoekstra OS, Lammertsma AA, Lubberink M, van Rossum AC, Knaapen P. Quantitative relationship between coronary artery calcium score and hyperemic myocardial blood flow as assessed by hybrid 15O-water PET/CT imaging in patients evaluated for coronary artery disease. J Nucl Cardiol. 2012;19:256–264. doi: 10.1007/s12350-011-9476-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knot HJ, Lounsbury KM, Brayden JE, Nelson MT. Gender differences in coronary artery diameter reflect changes in both endothelial Ca2+ and ecNOS activity. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1999;276:H961–H969. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.3.H961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mericli M, Nádasy GL, Szekeres M, Várbíró S, Vajo Z, Mátrai M, Acs N, Monos E, Székács B. Estrogen replacement therapy reverses changes in intramural coronary resistance arteries caused by female sex hormone depletion. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;61:317–324. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Momen A, Gao Z, Cohen A, Khan T, Leuenberger UA, Sinoway LI. Coronary vasoconstrictor responses are attenuated in young women as compared with age-matched men. J Physiol (Lond) 2010;588:4007–4016. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.192492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim A, Deo SH, Vianna LC, Balanos GM, Hartwich D, Fisher JP, Fadel PJ. Sex differences in carotid baroreflex control of arterial blood pressure in humans: relative contribution of cardiac output and total vascular conductance. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;301:H2454–H2465. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00772.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Veerareddy S, Cooke C-LM, Baker PN, Davidge ST. Gender differences in myogenic tone in superoxide dismutase knockout mouse: animal model of oxidative stress. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:H40–H45. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01179.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heaps CL, Bowles DK. Gender-specific K(+)-channel contribution to adenosine-induced relaxation in coronary arterioles. J Appl Physiol. 2002;92:550–558. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00566.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stauffer BL, Westby CM, Greiner JJ, Van Guilder GP, Desouza CA. Sex differences in endothelin-1-mediated vasoconstrictor tone in middle-aged and older adults. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2010;298:R261–R265. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00626.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mann MC, Exner DV, Hemmelgarn BR, Turin TC, Sola DY, Ahmed SB. Impact of gender on the cardiac autonomic response to angiotensin II in healthy humans. J Appl Physiol. 2012;112:1001–1007. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01207.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Orshal JM, Khalil RA. Gender, sex hormones, and vascular tone. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2004;286:R233–R249. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00338.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murthy VL, Di Carli MF. Non-invasive quantification of coronary vascular dysfunction for diagnosis and management of coronary artery disease. J Nucl Cardiol. 2012;19:1060–1072. doi: 10.1007/s12350-012-9590-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Recio-Mayoral A, Rimoldi OE, Camici PG, Kaski JC. Inflammation and microvascular dysfunction in cardiac syndrome x patients without conventional risk factors for coronary artery disease. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6:660–667. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2012.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dhawan SS, Corban MT, Nanjundappa RA, Eshtehardi P, McDaniel MC, Kwarteng CA, Samady H. Coronary microvascular dysfunction is associated with higher frequency of thin-cap fibroatheroma. Atherosclerosis. 2012;223:384–388. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2012.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaski JC, Tousoulis D, Galassi AR, McFadden E, Pereira WI, Crea F, Maseri A. Epicardial coronary artery tone and reactivity in patients with normal coronary arteriograms and reduced coronary flow reserve (syndrome X) J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;18:50–54. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(10)80216-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Malliani A. The elusive link between transient myocardial ischemia and pain. Circulation. 1986;73:201–204. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.73.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sheps DS, Kaufmann PG, Sheffield D, Light KC, McMahon RP, Bonsall R, Maixner W, Carney RM, Freedland KE, Cohen JD, Goldberg AD, Ketterer MW, Raczynski JM, Pepine CJ. Sex differences in chest pain in patients with documented coronary artery disease and exercise-induced ischemia: Results from the PIMI study. Am Heart J. 2001;142:864–871. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2001.119133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.El Fakhri G, Kardan A, Sitek A, Dorbala S, Abi-Hatem N, Lahoud Y, Fischman A, Coughlan M, Yasuda T, Di Carli MF. Reproducibility and Accuracy of Quantitative Myocardial Blood Flow Assessment with 82Rb PET: Comparison with 13N-Ammonia PET. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:1062–1071. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.104.007831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dekemp RA, Declerck J, Klein R, Pan X-B, Nakazato R, Tonge C, Arumugam P, Berman DS, Germano G, Beanlands RS, Slomka PJ. Multisoftware Reproducibility Study of Stress and Rest Myocardial Blood Flow Assessed with 3D Dynamic PET/CT and a 1-Tissue-Compartment Model of 82Rb Kinetics. J Nucl Med. 2013;54:571–577. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.112219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tahari AK, Lee A, Rajaram M, Fukushima K, Lodge MA, Lee BC, Ficaro EP, Nekolla S, Klein R, Dekemp RA, Wahl RL, Bengel FM, Bravo PE. Absolute myocardial flow quantification with (82)Rb PET/CT: comparison of different software packages and methods. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging[Internet] 2013 doi: 10.1007/s00259-013-2537-1. Available from: http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00259-013-2537-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Reis SE, Holubkov R, Smith AJC, Kelsey SF, Sharaf BL, Reichek N, Rogers WJ, Merz CNB, Sopko G, Pepine CJ. Coronary microvascular dysfunction is highly prevalent in women with chest pain in the absence of coronary artery disease: results from the NHLBI WISE study. Am Heart J. 2001;141:735–741. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2001.114198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shaw L, Iskandrian A. Prognostic value of gated myocardial perfusion SPECT. J Nucl Cardiol. 2004;11:171–185. doi: 10.1016/j.nuclcard.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schenker MP, Dorbala S, Hong ECT, Rybicki FJ, Hachamovitch R, Kwong RY, Di Carli MF. Interrelation of Coronary Calcification, Myocardial Ischemia, and Outcomes in Patients With Intermediate Likelihood of Coronary Artery Disease. Circulation. 2008;117:1693–1700. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.717512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Taqueti VR, Ridker PM. Inflammation, coronary flow reserve, and microvascular dysfunction: moving beyond cardiac syndrome x. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6:668–671. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.