Abstract

Iron-dependent halogenases employ cis-halo-Fe(IV)-oxo (haloferryl) complexes to functionalize unactivated aliphatic carbon centers, a capability elusive to synthetic chemists. Halogenation requires (1) coordination of a halide anion (Cl− or Br−) to the enzyme's Fe(II) cofactor; (2) coupled activation of O2 and decarboxylation of α-ketoglutarate to generate the haloferryl intermediate; (3) abstraction of hydrogen (H•) from the substrate by the ferryl oxo group; and (4) transfer of the cis halogen as Cl• or Br• to the substrate radical. This enzymatic solution to an unsolved chemical challenge is potentially generalizable to installation of other functional groups, provided that the corresponding anions can support the four requisite steps. We show here that the wild-type halogenase SyrB2 can indeed direct aliphatic nitration and azidation reactions by the same chemical logic. The discovery and enhancement by mutagenesis of these previously unknown reaction types suggests unrecognized or untapped versatility in ferryl-mediated enzymatic C–H-bond activation.

INTRODUCTION

The capacity to install functional groups onto aliphatic carbon centers late in synthetic sequences is considered a holy grail of synthetic chemistry. Despite much effort and significant progress, it remains an unsolved problem1,2. Biosynthetic sequences, by contrast, provide many spectacular examples of late aliphatic C–H bond functionalization3–9. Enzymes that employ (1) a free-radical or high-valent metal-oxo intermediate to abstract hydrogen (H•) from an aliphatic carbon, (2) a substrate binding site that permits only the C–H target and not other, more reactive functional groups to approach the reactive intermediate, and (3) allosterically controlled timing of intermediate formation achieve a degree of specificity and control not yet replicated in chemical systems6,7. However, biological C–H functionalization would, in light of current knowledge, appear to have its own limitations. Whereas enzymatic couplings of carbon10, oxygen3–5,11, phosphorus12, sulfur13, and halogen atoms14–16 to aliphatic carbon centers are known, examples of the installation of nitrogenous functional groups have not been forthcoming. Indeed, although there have been recent reports of an intramolecular amination of the benzylic carbon in an elegantly engineered, unnatural substrate and the nitration of an aromatic carbon by cytochrome P450 enzymes17, enzymatic C–N coupling at a completely unactivated aliphatic carbon center is unknown. In this reaction type, the development of synthetic methods has, ironically, outstripped the discovery or development of enzymatic activities18,19. It remains unclear whether such reactions do not exist in nature or simply remain to be discovered.

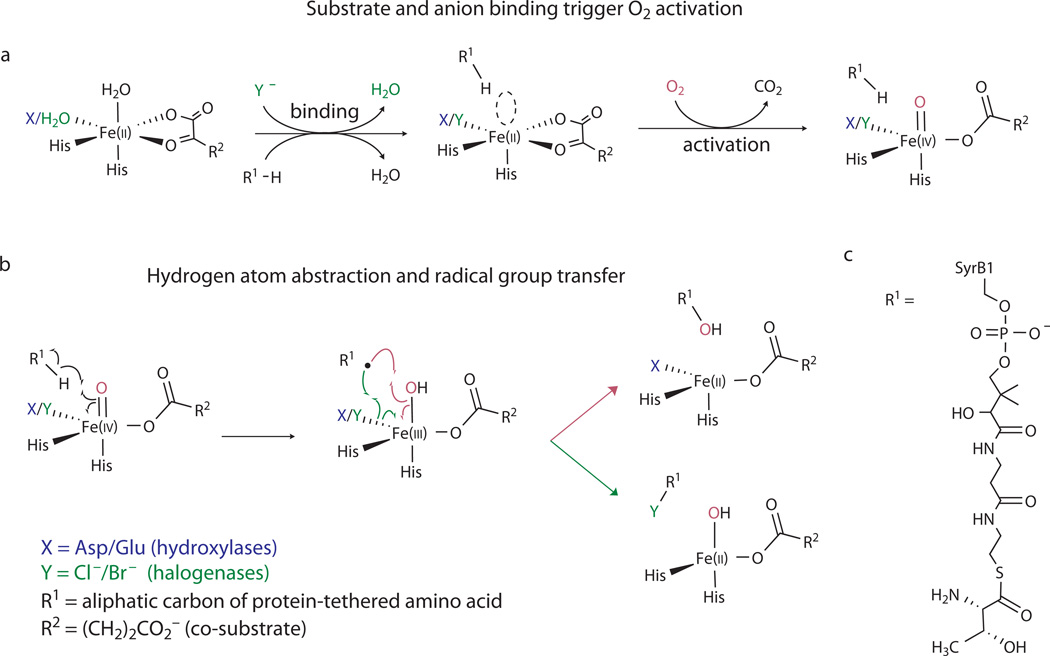

The iron(II)- and α-ketoglutarate-dependent (Fe/αKG) hydroxylases and halogenases have similar structures and share a common initial mechanism for aliphatic C–H activation3–5,11. In each reaction, an Fe(IV)-oxo (ferryl) intermediate, which forms from the Fe(II) cofactor, O2, and two electrons derived from oxidative decarboxylation of αKG to succinate (Fig. 1a), abstracts H• from the substrate to form a carbon-centered radical and Fe(III)-OH form of the cofactor (Fig. 1b)3–5,11,20. The reactions diverge according to the fate of this intermediate (Fig. 1b). In the hydroxylases, the substrate radical couples with the OH ligand (termed "oxygen rebound”21), thereby returning the cofactor to its resting +II oxidation state. In the halogenases, the substrate radical instead couples with a halogen ligand coordinated cis to the OH ligand, presumably converting the cofactor to an Fe(II)-OH form15,16,22–24. The halogen that is ultimately transferred to the substrate initially coordinates to the Fe(II) cofactor as free chloride or bromide at a position that is occupied in the hydroxylases by a carboxylate ligand from an aspartate residue22,25 (Fig. 1a). The controlling structural distinction is thus the replacement of the protein-donated carboxylate ligand in the hydroxylases by a non-coordinating alanine in the halogenases to open the site for coordination of halide22 in preparation for O2-driven ferryl formation15,16,23 and ferryl-mediated radical-group transfer24,25.

Figure 1. Related mechanistic logic of the Fe/αKG halogenases and hydroxylases.

(a) Steps leading to formation of the H•-abstracting (halo)ferryl complexes; (b) Divergence of the mechanisms of (halo)ferryl-mediated hydroxylation (top, magenta arrows) and halogenation (bottom, green arrows); (c) structure of the native SyrB2 substrate, SyrB1-appended L-threonine (Thr-S-SyrB1). The substrate used most extensively in this study had L-2-aminobutyric acid (Aba) appended to SyrB1 (Aba-S-SyrB1), which effectively replaced the side chain hydroxyl group of Thr-S-SyrB1 by hydrogen.

For the halogenase SyrB2 from the syringomycin biosynthetic pathway of Pseudomonas syringae B301D25,26, the basis for selective coupling of the substrate carbon radical with the cis-halogen rather than the hydroxyl ligand is the positioning of the C–H target of the substrate away from the (hydr)oxo ligand and closer to the halogen, which effectively sacrifices proficiency in the initial H• abstraction for selectivity in the subsequent group-transfer step24. Modifications to the native substrate (the C4 amino acid, L-threonine, appended to the carrier protein, SyrB125; Thr-S-SyrB1; Fig. 1c) anticipated to permit closer approach of the side-chain methyl target to the oxygen ligand (e.g., lengthening of the alkyl side chain) are associated with marked acceleration of an otherwise sluggish H•-abstraction step and a marked increase in competing hydroxylation. The substrate with the C5 amino acid, L-norvaline (Nva), appended to SyrB1 (Nva-S-SyrB1) supports 130-fold faster H• abstraction and undergoes primarily hydroxylation at C5. Computational studies have provided structural rationales for the positioning effect27 and suggested that the different target positions result in the engagement of different frontier orbitals in the H•-abstraction step, which in turn sets the stage for different group-transfer outcomes28,29. SyrB2 thus possesses two crucial features that enable its halogenation outcome: substrate and cofactor binding sites arranged so as to disfavor HO• rebound to the substrate radical after abstraction of H• by the ferryl oxygen, and an open coordination site cis to the oxygen that is more favorably disposed for transfer. We considered that these features might confer capabilities for ferryl-mediated radical-group-transfer reactions beyond the known halogenation and hydroxylation outcomes, including, perhaps, installation of nitrogenous functional groups.

RESULTS

Demonstration of azidation and nitration products

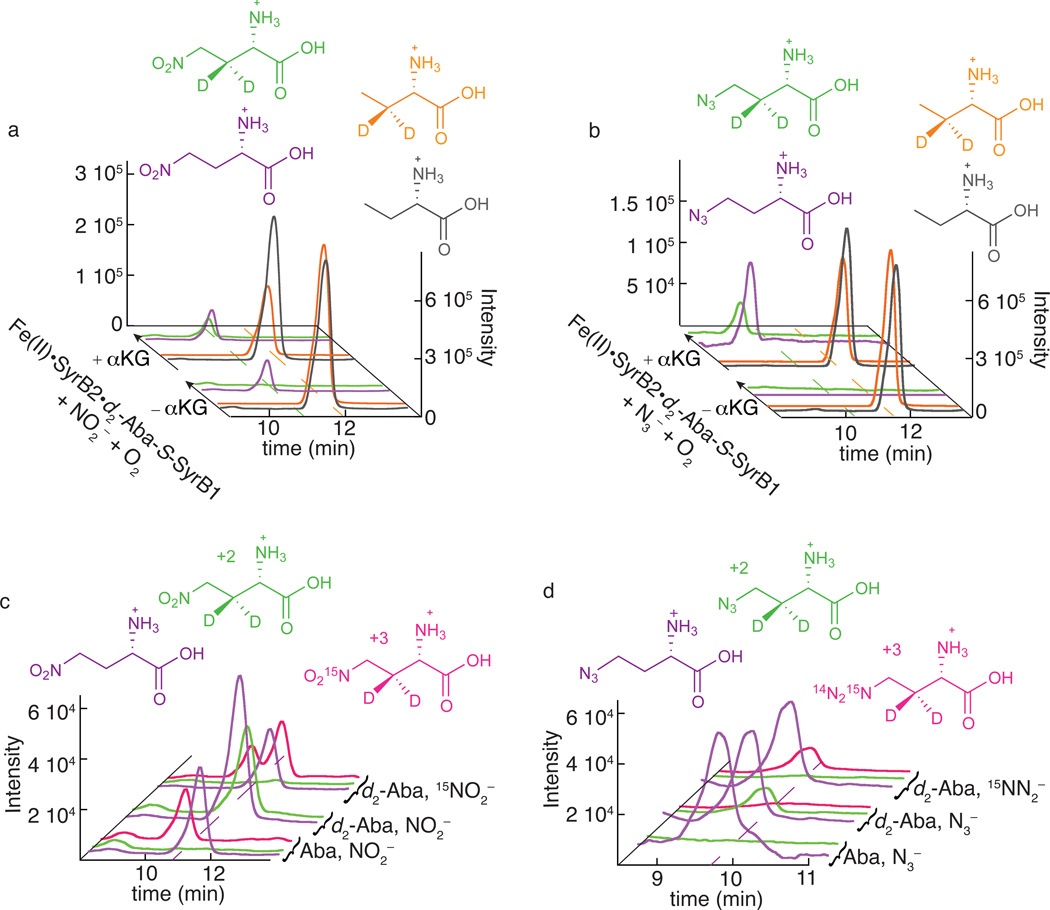

Analysis by liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry (LC-MS) of SyrB2 reactions carried out in the presence of the anions N3− and NO2− revealed that the wild-type halogenase can indeed mediate unprecedented azidation and nitration reactions upon a completely unactivated aliphatic carbon (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Results, Supplementary Fig. 1). We selected L-2-aminobutyrate (Aba; see Fig. 2 for structure) appended to SyrB1 (Aba-S-SyrB1) as the ideal substrate for this analysis, for two reasons. First, we anticipated that it would provide the optimal balance between proficiency in the H•-abstraction step, which varies in the order Thr-S-SyrB1 < Aba-S-SyrB1 < Nva-S-SyrB1, and propensity of the substrate radical to couple with the cis ligand rather than the HO•, which varies in the opposite order24 (Supplementary Fig. 2). Second, we could more easily obtain standards for the expected 4-NO2-Aba (1) and 4-N3-Aba (2) products (see Online Methods) than for the corresponding derivatives of the native Thr-S-SyrB1 substrate. We used remotely deuterium-labeled Aba (3,3-[2H2]-Aba or 3-d2-Aba) to prepare the Aba-S-SyrB1 substrate (giving 3-d2-Aba-S-SyrB1) so that MS signatures of the enzymatic products would be shifted by +2 units and the standard compounds with natural isotopic abundance could be used as LC-MS internal standards. We also analyzed control reactions lacking αKG (−αKG) to distinguish peaks associated with authentic products of the SyrB2 reaction from those associated with other reaction components and contaminants. The addition of the unlabeled Aba standard permitted quantification of the 3-d2-Aba-S-SyrB1 substrate that was consumed in the complete reactions (+αKG) (Fig. 2a, b). Single-ion-monitoring (SIM) LC-MS chromatograms revealed a diminished intensity of the peak for the 3-d2-Aba released from the substrate relative to that of the unlabeled Aba standard, indicating that the substrate was indeed consumed in the complete reactions. This substrate depletion was associated with formation of products having the m/z values expected for the 4-NO2-3-d2-Aba ([M+H]+ = 151.1) and 4-N3-3-d2-Aba ([M+H]+ = 147.1) products (Fig. 2, a–d). The peaks for these products had the same LC elution times as the authentic 4-NO2-Aba and 4-N3-Aba standards detected in the m/z = 149.1 and 145.1 SIM chromatograms. Their proper m/z values, co-elution with authentic standards, and absence from the chromatograms of the −αKG control samples strongly suggested that the peaks arose from the desired nitration and azidation products. These assignments were confirmed by both SIM chromatograms (Fig. 2c and d) and MS/MS-fragmentation chromatograms (Supplementary Fig. 1a and b) of samples prepared with isotopically labeled anions. In the reaction with NO2−, use of Aba-S-SyrB1 substrate prepared with unlabeled Aba resulted in a product with the same m/z as the standard, and, consequently, no peak was seen at m/z = 151.1 corresponding to the 4-NO2-3-d2-Aba product (Fig. 2c). The chromatograms from this reaction exposed a peak from a contaminant eluting just ahead of 4-NO2-Aba and having the same m/z (152.1) as 4-15NO2-3-d2-Aba. The contaminant peak could thus be properly accounted for in the actual experiment. The corresponding MS/MS chromatograms (Supplementary Fig. 1a) were free from this contaminant, owing to the specificity of the fragmentation used for detection. Use of the 3-d2-Aba-S-SyrB1 substrate gave a peak at the proper mass and elution time for 4-NO2-3-d2-Aba (Fig. 2c), as also shown in Fig. 2a. The abolition of this peak upon use of 15NO2− (98% isotopic enrichment) in place of the natural-isotopic-abundance anion and the appearance of the expected +1 peak (m/z = 152.1) eluting just after and largely resolved from the peak of the contaminant (Fig. 2c) confirmed the attachment of the nitrogenous anion to the Aba-S-SyrB1 substrate, an unprecedented C–N-coupling reaction. Analogously, in the N3− reaction, use of unlabeled Aba-S-SyrB1 substrate and the anion with natural isotopic abundance resulted in 4-N3-Aba product (2) indistinguishable from the standard, and no peak for 4-N3-3-d2-Aba was seen (Fig. 2d). Use of the 3-d2-Aba-S-SyrB1 substrate and natural-abundance N3− resulted in the expected peak at m/z = 147.1, as also shown in Fig. 2b. Replacement of the anion by 15N14N2− (98% isotopic enrichment) eliminated this peak and gave rise to the expected +1 peak, which was absent from the reaction with natural-isotopic-abundance N3− (Fig. 2d). These data confirmed the enzymatic coupling also of N3− to Aba-S-SyrB1. Nitration and azidation at the C4 methyl (rather than C3 methylene) of the appended Aba was implied both by co-elution of the enzymatic NO2- and N3-Aba products with the 4-modified standards and, more definitively, by the m/z value of the product: attachment at C3 of 3-d2-Aba-S-SyrB1 would have given a product with m/z = 150.1, rather than 151.1, as a result of the loss of 2H from C3, rather than 1H from C4, in the C–H-activation step.

Figure 2. LC-MS analysis demonstrating the novel C-N coupling reactions catalyzed by SyrB2.

Panels a and c illustrate detection of the nitration product (1) and b and d the azidation product (2). In a and b, single-ion chromatograms at the m/z values for deuterium-labeled substrate (orange) and unlabeled standard (black) and for the deuterium-labeled enzymatic nitration/azidation product (green) and unlabeled standard (purple) are shown. The scaling applied to match the intensities of the peaks for the labeled Aba substrate and its unlabeled standard in the −αKG control reactions reveals consumption of the labeled substrate in the complete (+αKG) reaction by diminution of the orange peaks at back. The 4-NO2-3-d2-Aba (a, green) and 4-N3-3-d2-Aba (b, green) products co-eluting with the unlabeled synthetic standards (purple) are formed only in the presence of αKG. Note that the unlabeled 4-N3-Aba standard was omitted from the −αKG control sample (b, purple at front) to permit baseline correction of the corresponding chromatogram from the +αKG reaction sample. The single-ion chromatograms in c and d definitively show the attachment of the anions in the detected products by the elimination of the "+2" peaks for 4-14NO2/14N3-3-d2-Aba (green) and appearance of the "+3" peaks for 4-15NO2/15NN2-3-d2-Aba (magenta) upon use of the 15N-labeled anion. Reaction conditions, sample preparation, and LC-MS method are provided in Online Methods.

Yields of the nitration and azidation products

We estimated the yields of the C-N-coupling products from the LC-MS SIM and LC-MS/MS fragmentation chromatograms (see Online Methods for details). The relative areas of the peaks for deuterium-labeled products and unlabeled standards in Fig. 2a and b and Supplementary Fig. 1 afforded estimates of the absolute concentrations of the 4-(NO2/N3)-3-d2-Aba products recovered in the small-molecule fractions after extended incubation to allow for their release from SyrB1 by hydrolysis of the thioester linkage. Comparison of the areas of the peaks for the 3-d2-Aba recovered from the carrier protein in the complete-reaction and −αKG-control samples to the area of the peak for the unlabeled Aba internal standard afforded estimates of both the quantity of 3-d2-Aba recovered in the workup in the absence of any substrate consumption (−αKG) and the quantity consumed in the complete reaction (+αKG). From these values, we obtained yields of (5 ± 2)% of the total Aba and (8 ± 2)% of the Aba consumed (means and standard deviations from 3 trials) for the nitration reaction; the corresponding azidation yields were (1 ± 0.4)% and (4 ± 2)% (4 trials), respectively. We consider the yields relative to the consumed substrate to be the more relevant metric, because unprocessed substrate presumably remains available for conversion in additional turnovers. Consistent with the reasoning from our previous study24, Aba-S-SyrB1 appeared to be more efficiently nitrated than either Thr-S-SyrB1 or Nva-S-SyrB1, although these other two substrates did also yield detectable quantities of C-N-coupling products (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Anion triggering of halo/nitrito/azido-ferryl formation

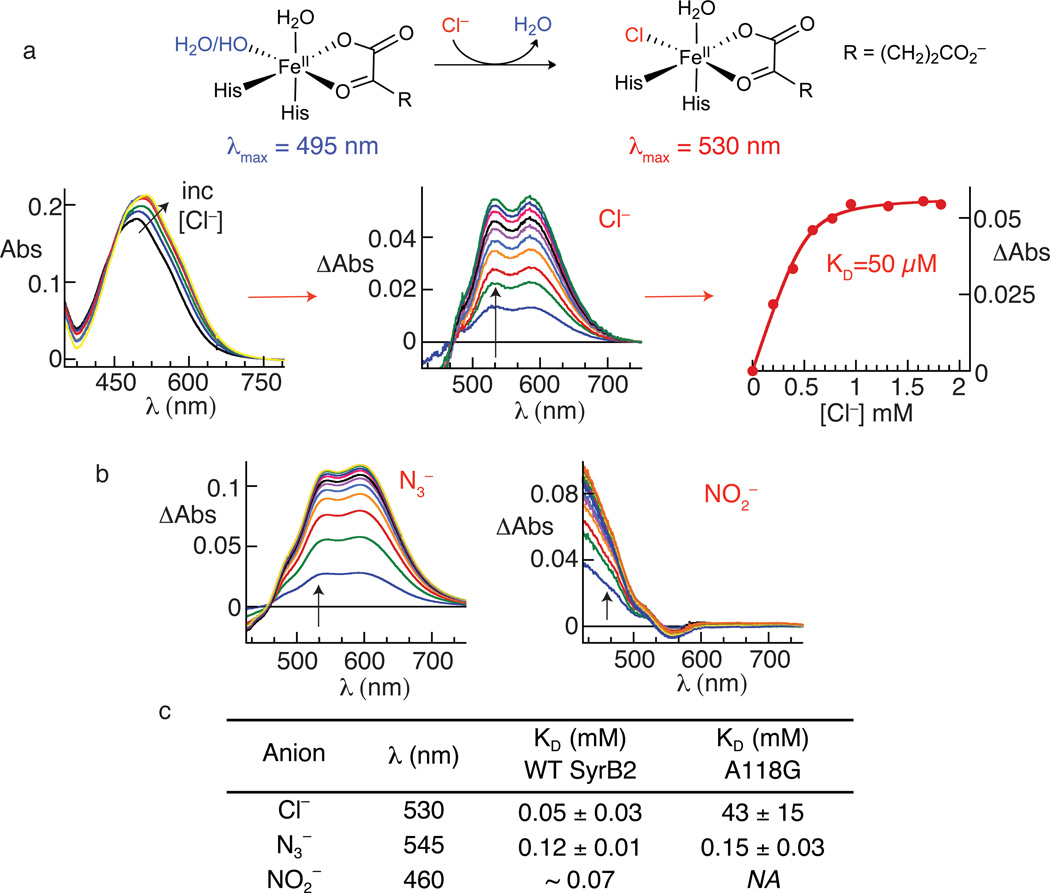

To establish that the novel aliphatic nitration and azidation reactions proceed by the expected ferryl-mediated radical-group-transfer mechanism, we interrogated the requisite steps in the mechanism (steps 1–4 enumerated above) individually. After noting a visible color change upon addition of Cl− to a solution of the SyrB2•Fe(II)•αKG complex, we discovered that binding of the native anion could be monitored directly by a shift in the FeII→αKG metal-to-ligand charge-transfer (MLCT) band at ~ 500 nm (Fig. 3a), which is a well-established hallmark of enzymes in this class3,30. Similar perturbations caused by addition of various non-native anions (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 4) demonstrated both the versatility of the anion-binding site and the robustness of this previously unknown spectral perturbation for assessing anion binding in efforts to engineer the halogenase either for greater efficiency in the detected nitration and azidation reactions or for other conceivable group-transfer outcomes. Indeed, binding of the nitrogenous anions, N3− and NO2−, could also readily be monitored by this assay (Fig. 3b), although the spectral change associated with addition of NO2− was quite different from those associated with the other anions, owing in part to its inherent ultraviolet absorption31. Plots of the extent of spectral change as a function of the anion (Y−) concentration (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 5) provided estimates of the equilibrium dissociation constants (KDs) of the anions from the SyrB2•Fe(II)•αKG•Y− complex. The apparent rank order of affinities for the anions that caused a measureable shift in the MLCT band was Cl− > NO2− > CN− ~ N3− ~ OCN− > Br− ~ HS− > HCO2− (no evidence for binding of SCN−, CH3S−, I−, NO3− and F−; data not shown), but the KD values for the competent anions spanned only a factor of ~ 10 (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Table 1). The anion site was thus found to be quite tolerant of differences in shape, steric bulk, and electronic structure.

Figure 3. inding of chloride, azide and nitrite to the SyrB2•Fe(II)•αKG complex monitored by perturbations to the absorption spectrum from the FeII→αKG MLCT transition.

Panel a summarizes the basis for the perturbation (top) and the progression in the analysis from experimental spectra (left) to difference spectra (middle) to titration curve (right) for the native Cl−. Spectra were collected after each addition of an aliquot of the concentrated, buffered Cl− solution. For each experimental spectrum, correction was made for dilution by the Cl− solution, the spectrum of the starting solution was subtracted from the dilution-corrected spectrum, and the absorbance at 800 nm was set to zero. Panel b shows the corresponding difference spectra for the titrations with N3− (left) and NO2− (right). Panel c gives the dissociation constants (KD) determined by plotting the change in absorbance (ΔAbs) at an appropriate wavelength (indicated by the arrows in a and b) versus [anion] and fitting the equation for a hyperbolic or quadratic curve to the data, as appropriate. Difference spectra and titration curves used to determine KD values reported in c for the A118G variant are shown in Supplementary Figs. 10 and 11.

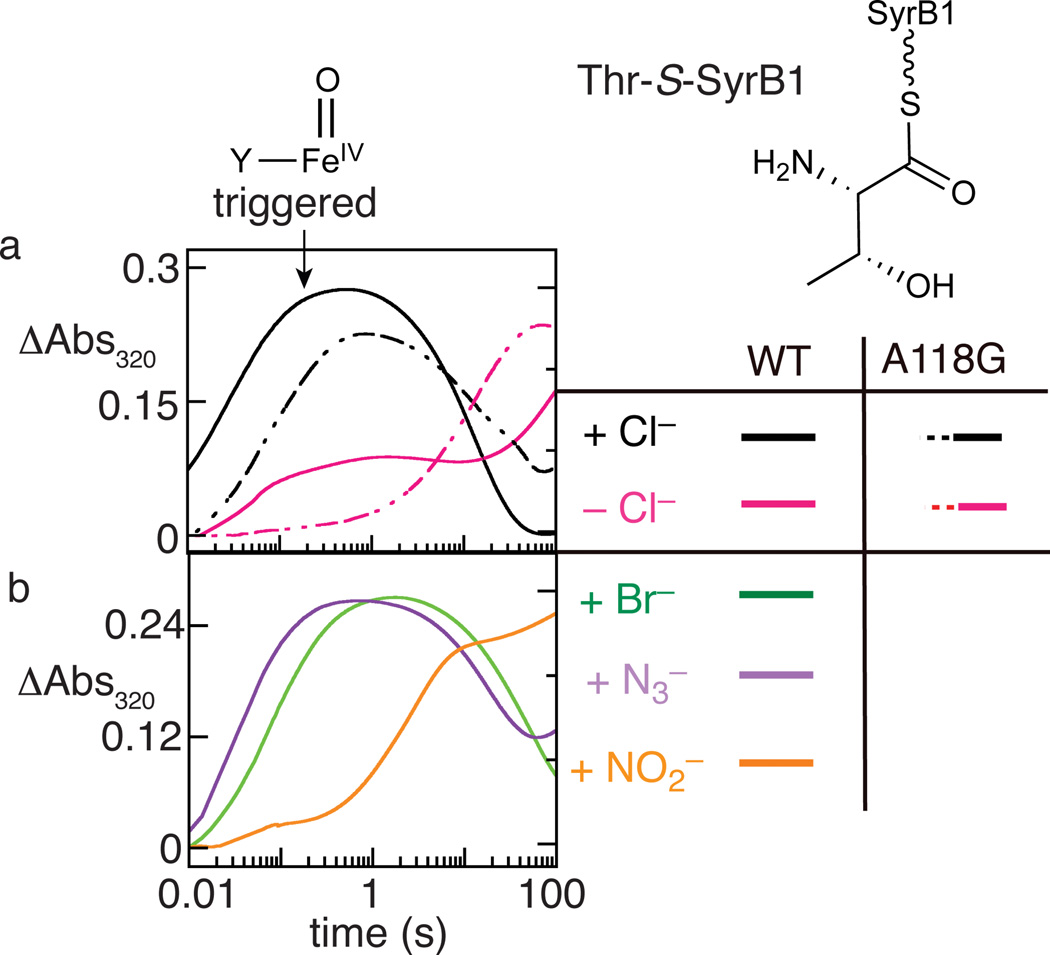

By interrogating the O2 reactivity of SyrB2 in the presence of its aminoacyl-SyrB1 substrate and in the absence or presence of an added anion, we discovered an important but previously unrecognized functional feature of the halogenase: binding of the anion profoundly activates the enzyme and its Fe(II) cofactor for reaction with O2, just as binding of the aminoacyl-carrier protein substrate was previously shown to "trigger" formation of the key ferryl intermediate16. In the reaction with either the native, chlorination-predominant Thr-S-SyrB1 substrate or the hydroxylation-predominant Nva-S-SyrB1 substrate, development of the ultraviolet absorption and Mössbauer quadrupole doublet features of the chloroferryl complex was impeded or eliminated in reactions from which Cl− was omitted and was restored upon addition of the native anion (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Figs. 6–8). The small, faster phase in the ∆Abs320 kinetic trace of the Thr-S-SyrB1 reaction lacking added anion (Fig. 4a) suggested the presence of contaminating Cl− despite extensive dialysis intended to remove it, a deduction consistent with our detection by LC-MS of chlorinated products even in reactions to which Cl− was not intentionally added (see below). Difficulty in removing Cl− has been reported in other studies on aliphatic halogenases25. The non-native halide, Br−, and the nitrogenous anions, N3− and NO2−, all also triggered activation of O2 (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 9, d–i), albeit with varying efficacy. Among the non-native anions, N3− was the most effective and NO2− the least effective. For each of the non-native anions, Mössbauer quadrupole doublet features consistent with the accumulation of one or more Fe(IV) complex could be observed in freeze-quenched samples of the reaction triggered by the anion (Supplementary Fig. 6 and reference 23). These observations established that installation of the nitrogenous anions proceeds by the same mechanism as the native halogenation reaction. They further established anion triggering of O2 activation as a control mechanism employed by SyrB2 in its native function. The differential triggering of O2 activation by different anions hints at the possibility of engineering the enzyme not only for improved binding selectivity for a given non-native anion but also for improved triggering efficacy by that anion, which could potentially provide an additional tool for enhancing efficiency of novel group-transfer outcomes.

Figure 4. "Triggering" of O2 addition and ferryl formation in SyrB2 by binding of the anion.

Development of absorption at 320 nm, previously shown to reflect formation of the ferryl complex, was monitored after an O2-saturated buffer solution was mixed in the stopped-flow apparatus with an O2-free solution of either the SyrB2•Fe(II)•αKG•Thr-S-SyrB1 complex (solid traces) or the SyrB2-A118G•Fe(II)•αKG•Thr-S-SyrB1 complex (dashed traces) containing (a) no added anion (magenta) or 50 mM added Cl− (black); or (b) 50 mM Br− (green), 0.20 mM N3− (purple), or 1.0 mM NO2− (orange). In a, comparisons of the solid black trace to the solid magenta trace and the dashed black trace to the dashed magenta trace reveal the triggering effect of Cl− in wild-type SyrB2 and the A118G variant, respectively. The minor fast phase in the solid magenta trace reflects the presence of contaminating Cl−. In b, the major rise phase in each of the three traces is faster than the slower rise phase in the solid magenta trace in a, illustrating the triggering effects of the non-native anions. Mössbauer spectra of samples freeze-quenched at the reaction times of maximum ΔA320 are shown in Supplementary Fig. 6 and demonstrate development of quadrupole-doublet features with parameters characteristic of ferryl complexes.

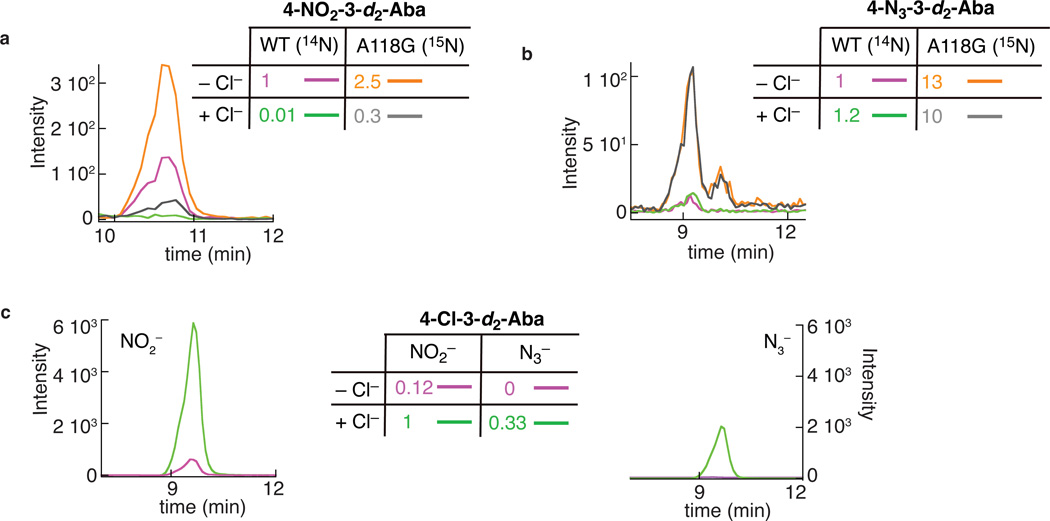

Rational improvement of C-N coupling efficiency

The ability to install nitrogenous functional groups, in particular the azido group, onto aliphatic carbon centers could enable new methods in the field of chemical biology. Indeed, the so-called "click" and Staudinger-ligation reactions, already widely used in the field, rely on the unique and "bio-orthogonal" reactivity of the azido group32–34. Development of an azidation catalyst useful for in vivo applications would be facilitated by improvement upon the modest yields observed here and might require modification of the enzyme to cope with the relatively high concentrations of Cl− in biological milieu35. Unlike the native Cl−, neither N3− nor NO2− is spherical, and each could potentially experience steric clashes within a pocket evolved to bind Cl− selectively. We reasoned that substitutions opening space in the anion-binding site of SyrB2 might, therefore, improve the enzyme as a catalyst for C–N-coupling reactions by diminishing affinity for the native Cl−, attenuating the thermodynamic discrimination against binding of the complex anions, perturbing the relative triggering efficacies of the native and non-native anions, permitting binding in a geometry more favorable for radical-group transfer, or some combination of these four effects. The Ala118→Gly (A118G) substitution effectively replaces a methyl group in this pocket by hydrogen. This substitution results in ~1,000-fold diminution in the affinity for the native Cl− without significantly affecting the affinity for N3− (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Figs. 10 and 11). In addition, anion triggering of O2 addition is retained in the A118G variant protein (Fig. 4a). Trials comparing intensities of LC-MS/MS peaks from reaction products generated by the wild-type and variant enzymes under identical reaction conditions showed that, indeed, the quantities of both C–N-coupling products were invariably greater with the A118G variant (e.g., Supplementary Fig. 1a and b), and so the extent of enhancement associated with the substitution and impact of the substitution on the ability of added Cl− to suppress the C–N-coupling outcomes were accurately assessed in an isotope-ratio experiment (Fig. 5). In this experiment, the products from the wild-type and A118G variant enzymes were distinguished by use of the isotopologic anions, 14NO2− or 14N3− with the wild-type enzyme and 15NO2− or 15N14N2− with the A118G variant. After being allowed to proceed to completion, the reaction samples were combined and analyzed by LC-MS/MS. Under the conditions examined (in a single trial), the A118G substitution was found to enhance the yield of nitration by ~ 2.5-fold (Fig. 5a) and the yield of azidation by ~ 13-fold (Fig. 5b) in the absence of added Cl−. An azidation yield of greater than 20% of the 3-d2-Aba consumed was estimated for this experiment. For the more efficient nitration reaction, yields as high as (52 ± 8)% of the 3-d2-Aba consumed [(22 ± 4)% of the initial 3-d2-Aba present] were observed (mean and range of two experiments in Supplementary Fig. 1). Moreover, nitration by the A118G variant protein was more robust to suppression by Cl− than nitration by the wild-type enzyme. In the isotope-ratio experiment, the level of contaminating Cl− was sufficient to support chlorination in competition with nitration (Fig. 5c), and the peak intensities implied similar yields of the two products under these conditions (Fig. 5a and c). In the presence of one equivalent (with respect to SyrB2) of additional Cl−, nitration by the wild-type enzyme was almost completely suppressed, whereas nitration by the A118G variant still proceeded to a significant extent (Fig. 5a). Thus, under these conditions, the variant SyrB2 was more efficient than the wild-type enzyme by ~ 30-fold. The azidation reaction was observed to be intrinsically more robust to Cl− suppression than the nitration reaction, even in the wild-type enzyme. With just the contaminating Cl− present, chlorination was undetectable in the presence of the 2.5 equivalents (per SyrB2) of N3− that was added in the reaction (Fig. 5c). In the presence of one equivalent of additional Cl− along with the N3−, chlorination was detected (Fig. 5c), but the yield of the azidation product was not significantly diminished for either the wild-type or variant SyrB2 (Fig. 5b).

Figure 5. Enhanced efficiency of C–N coupling in the A118G variant of SyrB2.

The LC-MS/MS chromatograms monitor collision-induced transitions associated with the (a) nitration, (b) azidation, and (c) chlorination products formed in the reactions of the wild-type and A118G variant SyrB2. a and b: reactions of the wild-type protein in the presence of the natural-abundance anion and the A118G variant protein in the presence of 15NO2− or 15N14N2− were combined and co-injected. Purple and orange: reactions containing no added Cl−; green and gray: reactions containing 1 equiv per SyrB2(-A118G) added Cl−. Comparison of the orange and purple traces in a illustrates that the nitration yield of the A118G variant is ~ 2.5-fold greater than the yield of the wild-type enzyme in the absence of added Cl−; comparison of the gray and green traces implies a ~ 30-fold greater nitration yield for the A118G variant in the presence of one equivalent added Cl−. Cross comparisons of the orange and gray or purple and green traces illustrate the ability of added Cl− to suppress the nitration reaction in both wild-type SyrB2 and the A118G variant. Comparison of the orange and purple traces in b illustrates that the azidation yield of the A118G variant is ~ 13-fold greater than yield of the wild-type enzyme in the absence of added Cl−. Comparisons of the orange and gray or purple and green traces illustrate the inability of one equivalent added Cl− to suppress the azidation reaction in either wild-type or A118G variant SyrB2. c: chromatograms for the chlorination product showing that addition of Cl− (green) enhances the chlorination yields in both the reaction with NO2− (left) and the reaction with N3− (right) compared to the corresponding reactions without added Cl− (purple).

DISCUSSION

To assess the virtues and limitations of the newly demonstrated reactions, it is relevant first to compare the mechanistic strategy employed by SyrB2 to those of other known enzymatic and chemical C–N-coupling reactions. A recently reported nitration of an aromatic carbon mediated by a cytochrome P450 bears some resemblance to the SyrB2-mediated nitration reaction36, but the aromatic nitration almost certainly does not proceed by initial C–H cleavage, as group transfers to aliphatic carbons must. Similarly, C–N-coupling by a streptavidin-based artificial Pd-containing metalloenzyme targets an olefinic carbon37, a chemically less challenging transformation. A recently reported intramolecular amination of a benzylic carbon by an engineered cytochrome P450 on an unnatural substrate having an adjacent photo-reactive aryl azide functionality to generate an iron-nitrenoid intermediate is perhaps more closely related, but it also does not target a completely unactivated aliphatic C–H bond in the presence of inherently more reactive targets, as the SyrB2 reactions do17. Likewise, the several, novel chemical strategies for coupling nitrogen to aliphatic carbon centers (e.g., aminations) that have recently been developed38–41 have certain inherent limitations. In some cases, the outcomes are intramolecular couplings directed by proximity engineered into the substrates39–41. In others, the C–H target is partially activated38–40. Most importantly, the intimate involvement of the nitrogen atom in the C–H-cleaving iron-nitrenoid intermediates initiating all of these reactions limits their potential scope.

The strategy employed by SyrB2 in its native halogenation and now nitration and azidation reactions has different limitations. Firstly, all halogenases discovered to date require a carrier-protein appended substrate (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 2a). This requirement limits the substrate scope to amino acids that the corresponding charging ("adenylation") function, which in SyrB1 resides in the N-terminus of the same polypeptide, will append to the phosphopantetheine cofactor of the carrier protein/domain. However, our previous work showed that SyrB1 is, fortuitously, relatively promiscuous and will self-charge multiple amino acids with diverse side-chains16. Moreover, the two other aminoacyl-SyrB1 substrates (Thr-S-SyrB1 and Nva-S-SyrB1) in the series of three that was used to establish the dominant role of substrate positioning in controlling the reaction outcome24 are also both detectably nitrated. This observation implies that, whereas proper substrate positioning is important also for the nitration outcome, the requirement is not so stringent as to limit the scope of the reaction to a single substrate. Moreover, modification of adenylation modules for altered amino-acid specificity has been achieved42,43 and could further expand the substrate scope. Finally, there is no a priori reason that the mechanistic strategy could not be extended to small-molecule substrates (in either natural or engineered enzymes), a possibility that we continue to explore. The second limitation of the reactions in their current forms is the modest yields. Here, the ability of a single, rationally chosen substitution to enhance the binding specificity of the desired anion, augment the yields of both reactions, and confer robustness to suppression by the native anion bodes well for the potential to evolve Fe/αKG oxygenases for such alternative outcomes.

Despite their present limitations, the new C–N-coupling reactions extend an enzymatic strategy for functionalization of unactivated carbon centers that is fundamentally distinct from the other chemical and enzymatic precedents and is, at least potentially, more versatile. With the requisite, initiating H•-abstraction delegated to the common oxo ligand of the ferryl intermediates, the scope of cis-coordinated anionic ligands that might conceivably be coupled is broad. Although we have not yet detected products resulting from the transfer of other non-halide ligands, the promiscuous binding and triggering of O2 activation by different anions and the robustness of ferryl formation in their presence (Supplementary Fig. 6) suggest that other reactions will be possible. Moreover, all demonstrated and envisaged couplings are intermolecular and expected to be exquisitely controlled by the active site architecture. Indeed, it is precisely this absolute chemo-, regio- and stereo-specificity that can be accomplished by enzymes by virtue of their complex substrate binding sites that has made their use in synthetic chemistry seductive and, more recently, practically important44,45. These considerations provide impetus for ongoing efforts to develop and discover enzymatic catalysts for aliphatic C–N coupling reactions.

ONLINE METHODS

Materials

Sodium bromide (NaBr), sodium sulfide nonahydrate (Na2S•9H2O), sodium cyanide (NaCN), sodium nitrite (NaNO2), sodium methyl thiolate (NaSCH3), sodium thiocyanate (NaSCN), sodium fluoride (NaF), L-glycine, and ammonium formate (NH4HCO2) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Sodium azide (NaN3) was purchased from EMD Chemicals, Inc. (Gibbstown, NJ). Potassium cyanate (KOCN) was purchased from Alfa Aesar (Ward Hill, MA). Sodium nitrate (NaNO3) was purchased from J. T. Baker (Phillipsburg NJ). (2S)-2-Amino-4-azido-butanoic acid (4-N3-Aba) was obtained from Toronto Research Chemicals Product List (North York, Canada). All other chemicals (except for 4-NO2-Aba, which was synthesized as summarized below) were obtained from sources previously noted.16,24 Purchased reagents were used as received, without purification.

General synthetic methods

NMR spectra were recorded on Bruker 360 MHz spectrometers. Chemical shifts are reported in ppm using a residual solvent peak as an internal standard. J values are reported in Hz.

Synthesis of 4-NO2-Aba

4-NO2-Aba was synthesized as previously reported46. Lithium diisopropylamide (3.5 mL of 0.5 M solution in THF, 1.75 mmol) was added dropwise to a solution of N-diphenylmethyleneglycine t-butyl ester (500 mg, 1.7 mmol) in THF (5.0 mL) at −78 °C, and the solution was stirred for 1.5 h. Nitroethylene (3.4 mL of 0.5 M solution in THF, 1.7 mmol) was then added to the reaction solution at the same temperature. After stirring for 1 h, the reaction mixture was gradually brought to room temperature and quenched by addition of water (20 mL) followed by ethylacetate (20 mL). The combined organic layer was washed with brine and concentrated under vaccum. The product was purified by silica gel chromatography using hexanes:ethylacetate (4:1) as an eluent to obtain the pure product in 40% yield. The 1H-NMR spectrum of the t-butyl 2-diphenylmethyleneimino-4-nitrobutanoate was identical to that reported in the literature46. Global deprotection was carried out by adding 1N HCl (5 mL) to the t-butyl 2-diphenylmethyleneimino-4-nitrobutanoate (37 mg, 0.1 mmol) and stirring at room temperature overnight. The reaction mixture was extracted with ethyl ether (3 × 5 mL), and the aqueous layer was subjected to lyophilization to obtain the final product. 1H-NMR: (360 MHz, D2O) δ 4.03 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 2.39–2.49 (m, 3H) (Supplementary Fig. 12).

Protein purification and substrate assembly

These steps were performed as previously described16.

Anion titrations and analysis to extract dissociation constants

Analogously to published titrations of SyrB2 with Fe(II)47, a concentrated, buffered, O2-free stock of the relevant anion was added in small aliquots to an O2-free solution of the SyrB2•Fe(II)•αKG complex or A118G-SyrB2•Fe(II)•αKG complex containing 0.75 mM Fe(II), 5 mM αKG, and 1 mM SyrB2 or SyrB2-A118G. Spectra were acquired after each addition until the absorption spectrum stopped changing (after several min).

Stopped-flow absorption experiments

The kinetics of formation and decay of the ferryl intermediate at 5 °C were monitored by its absorbance at 320 nm (ΔAbs320). An O2-saturated buffer solution (20 mM Na-HEPES, pH 7.5) was mixed in the stopped-flow apparatus with an equal volume of an O2-free solution containing 0.4 mM SyrB2 (or SyrB2-A118G), 0.3 mM Fe(II), 10 mM αKG, and 0.9 mM of the indicated aminoacyl-SyrB1 substrate. The anion concentrations in the experiment of Fig. 4 were 50 mM Cl− (panel a) and 0.2 mM N3− or 1 mM NO2− (panel b). The reactant concentrations in the experiments depicted in Supplementary Figs. 7 and 9 were equivalent. Solely to clarify presentation of the stopped-flow data, the Steineman smoothing function supplied as a standard feature of the Kaleidagraph (Synergy Software, Reading, PA) analysis software was applied to all kinetic traces.

Preparation of Mössbauer samples and spectral analysis

Unless otherwise noted, the final concentrations for all Mössbauer samples in Supplementary Figs. 6 and 8 were: [57Fe] ~ 0.4 mM, [SyrB2] ~ 0.5 mM, [aminoacyl-S-SyrB1] ~ 0.8 mM, [αKG] = 5 mM, [NaCl] = 50 mM, [NaCN/NaNO2/Na2S] = 1 mM, and [N3−] = 0.4 mM. 4.2-K/zero-field spectra of the reactant SyrB2•Fe(II)•αKG•Y−•aminoacyl-S-SyrB1 complexes were analyzed by regression analysis assuming one or two symmetrical quadrupole doublets. The fits returned parameters typical of high-spin Fe(II) complexes. Spectra of samples that were reacted with O2 exhibited features with parameters typical of high-spin Fe(IV), which were assigned to the Y–Fe(IV)=O intermediates, and features from unreacted high-spin Fe(II) complex(es). The high-energy lines of the quadrupole doublets assigned to Fe(IV) and Fe(II) were well-resolved, but the associated low-energy lines were unresolved. To overcome this lack of resolution and determine the Mössbauer parameters of the Fe(IV) complexes, we analyzed experimental spectra of freeze-quenched samples in one of three ways. First, we subtracted the appropriate contribution of the experimental spectrum of the corresponding Fe(II)-containing reactant complex, as judged by comparison of the intensity of the resolved high-energy lines. This subtraction produced "reference spectra" for the Fe(IV) complexes that were of variable quality but yields acceptable results when the shape of the high-energy line of the Fe(II) component matched well with that from the Fe(II) reactant complex or if the contribution from Fe(II) in the spectrum of the freeze-quenched sample was small. The second method for generation of Fe(IV) reference spectra involved modeling the spectral contribution of the Fe(II) complexes as quadrupole doublets with parameters (isomer shift, γ, quadrupole splitting, ΔEQ, and line width, Γ) obtained from fitting of the spectra of the reactant complexes, but in varying proportions. The third method for generation of the Fe(IV) reference spectra was identical to the second method, except that the line widths of the Fe(II) quadrupole doublets were allowed to vary within 10% of the value obtained from fitting of the Fe(II) reference spectrum. The Fe(IV) reference spectra were then simulated as a single quadrupole doublet, except for that of the chloroferryl intermediate in the presence of either Thr-S-SyrB116 or d5-Nva-S-SyrB1, for which the high-energy line of the Fe(IV) reveals two partially resolved peaks, indicating the presence of two ferryl complexes, as previously reported15,16. The spectra of the presumed nitritoferryl [O2N–Fe(IV)=O] and (hydro)sulfidoferryl [(H)S–Fe(IV)=O] complexes with d5-Thr-S-SyrB1 were rather sharp, and the positions of the low-energy lines of the various reference spectra were well determined. The azidoferryl [N3–Fe(IV)=O] intermediate formed with d5-Thr-S-SyrB1 accumulated in high yield, and the lines were nearly symmetrical but broad. The spectrum of the cyanidoferryl [CN–Fe(IV)=O] complex was the least well-resolved, owing to its lesser accumulation, differences between the Fe(II) components in the reactant and freeze-quenched samples, and the breadth of the lines in the Fe(IV) reference spectrum. From these analyses, we estimated the uncertainties in the values for the Mössbauer parameters to be 0.05 mm/s for the isomer shifts and 0.10 mm/s for the quadrupole splitting parameters. These error estimates are conservative: they represent the upper limits of the observed variations in the extracted parameters for the different methods of analysis.

C–N coupling reactions and analysis by LC-MS

Reactions associated with Fig. 2 were performed as follows. Aba-S-SyrB1 and 3-d2-Aba-S-SyrB1 were prepared by incubation of 3.0 mM HS-SyrB1, 5.0 mM Aba or 3-d2-Aba, 30 mM ATP, and 30 mM MgSO4 for 30 min at room temperature. Prior to their use in the SyrB2 reactions, assembled substrates were purified from small-molecules as previously described24. The final concentrations in the SyrB2 reactions were 0.2 mM Fe(II), 0.2 mM SyrB2, 0.8 mM Y−, 0.12 mM αKG and 0.1 mM desalted Aba-S-SyrB1 or 3-d2-Aba-S-SyrB1. L-glycine, an amino acid that SyrB1 cannot append to its carrier domain, was added to 10 µM as an internal standard. Overnight incubation at ambient temperature allowed the SyrB2 reaction to proceed to completion and the thioester-linked amino acid substrates and products to be hydrolyzed from the phosphopantetheine cofactor. The amino acids were then purified from the free SyrB1 and SyrB2 proteins via passage through a Microcon centrifugal filter unit with 10-kDa molecular mass cut-off (Millipore). In the control reactions lacking αKG, a typical recovery of 3-d2-Aba in this procedure was ~ 50%. Prior to LC-MS analysis, 25 µM Aba, 2.5 µM 4-NO2-Aba, and/or 2.5 µM 4-N3-Aba were added to the filtrate, as appropriate. The concentrations of standards were chosen such that their measured peak areas were comparable to those for corresponding reaction products.

Reactions associated with Fig. 5 were performed essentially as described above, with the following exceptions. After the reaction of the wild-type and A118G variant SyrB2 were allowed to reach completion, equal volumes of the two solutions were mixed. C–N coupling products generated by each enzyme could be distinguished by using isotopologic anions. Unlabeled 14NO2− or 14N3− was used with the wild-type enzyme and isotopically enriched 15NO2− or 15N14N2− was used with the A118G variant, necessarily associating 4-N3- and 4-NO2-d2-Aba products with the reaction of the wild-type enzyme and 4-15N14N2- and 4-15NO2-d2-Aba products with the reaction of the A118G variant. The concentrations of reactants in the nitration and azidation reactions were 0.25 mM Fe(II), 0.25 mM SyrB2, 1.3 mM NO2−, 0.25 mM αKG, and 0.13 mM 3-d2-Aba-S-SyrB1, and 0.25 mM Fe(II), 0.25 mM SyrB2, 0.63 mM N3−, 0.15 mM αKG, and 0.13 mM 3-d2-Aba-S-SyrB1, respectively. In this case, the 3-d2-Aba-S-SyrB1 substrate was prepared by incubation of 0.19 mM HS-SyrB1, 0.15 mM 3-d2-Aba, 2.3 mM ATP, and 2.3 mM MgSO4 for 30 min at ambient temperature and was used in the SyrB2 reactions without desalting.

The liquid chromatography was performed on a ZIC-HILIC column (Merck-Millipore). The mobile phase was a mixture of 95:5 (v/v) CH3CN:H2O (A) and 95:5 (v/v) H2O:CH3CN (B), of which both were supplemented with 0.1% formic acid to facilitate ionization. Following sample injection (10 µL) under 95% B with a flow rate of 0.4 mL/min, the mobile phase was varied linearly to 80% B over the first 10 min, held constant for 5 min, changed to 0% B over the next 20 min, increased linearly to 95% B over the following 20 min, and held constant at 95% B in preparation for the next injection. In the SIM chromatograms of Fig. 2, parent amino acid cations were monitored. In the MS/MS fragmentation chromatograms of Fig. 5, the daughter iminium ions formed by neutral loss of CO2 and H2 (a combined mass of 46 atomic mass units) from the parent cations were selectively monitored (see Supplementary Table 4 for the m/z values of the relevant transitions). The fragmentation was detected by application of a collision energy of 3V to the parent ion. The drying gas temperature was 350 °C with a nebulizer pressure of 40 psi and flow rate of 9 L/min. The capillary voltage was set to 4000 V. The fragmentor voltage was set at 70 V to achieve maximal electrospray ionization for detection. Dwell times of 50 ms and 400 ms were dedicated to detection of each parent or parent-to-daughter cation transition, respectively.

Estimation of the yields of the 4-NO2/N3-Aba products

The fact that the initial amino acid products of the SyrB2 reaction are linked as thioester to SyrB1 creates the challenge of determining the combined yield of hydrolysis off the carrier protein and recovery in the workup. The immediate 4-NO2/N3-3-d2-Aba-S-SyrB1 products were not readily accessible either by synthesis or by enzymatic attachment of the synthetic amino acid products to the phosphopantetheine cofactor of the carrier domain by the adenylation domain (they appear not to be accepted for charging). Recovery of the 3-d2-Aba substrate off the SyrB1 carrier protein was assessed in a control reaction from which αKG was omitted. In the control, comparison of the peak for the 3-d2-Aba released from SyrB1 to that for the unlabeled free Aba amended to the sample afforded absolute quantification of the released 3-d2-Aba and its fractional recovery (40–60% overall). Likewise, this same comparison for the reaction sample containing αKG permitted quantification of unreacted 3-d2-Aba recovered in the complete reaction. The difference between these concentrations gave the concentration of 3-d2-Aba consumed in the reaction. Comparison of the peak for the 4-NO2/N3-3-d2-Aba amino acid to that for the synthetic, unlabeled 4-NO2/N3-Aba standard amended to the reaction afforded absolute quantification of the recovered enzymatic product. By invoking the necessary assumption that the fractional recovery of the 4-NO2/N3-3-d2-Aba amino acid from the 4-NO2/N3-3-d2-Aba-S-SyrB1 primary product was identical to that determined for the unreacted 3-d2-Aba, the yield of the product with respect to either the 3-d2-Aba consumed or the total 3-d2-Aba initially present in the reaction was calculated. For example, in two typical nitration reactions under conditions optimized for this reaction with the A118G variant, we detected 11(±1) µM 4-NO2-3-d2-Aba (reaction volume of 0.10 mL) when the recovered 3-d2-Aba in the −αKG-control reaction was 49 µM and the amount of 3-d2-Aba recovered in the complete reaction was 28(±1) µM (mean and range of two measurements). The 3-d2-Aba concentrations imply that ~ 21 µM substrate was consumed in the complete reaction. Dividing the 11 µM 4-NO2-3-d2-Aba produced by the 21 µM 3-d2-Aba consumed gives a nitration yield of ~ 52% of the 3-d2-Aba consumed. Alternatively, the ratio of the 11 µM 4-NO2-3-d2-Aba produced to the 49 µM recovered in the absence of any conversion gives a nitration yield of ~ 22% of the 3-d2-Aba initially present in the reaction.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (GM-69657 to C.K and J.M.B.), the National Science Foundation (MCB-642058 and CHE-724084 to C.K and J.M.B.). We thank Prof. Catherine Drennan and Dr. Mishtu Dey at M.I.T. for the kind gift of the plasmid to express SyrB2-A118G.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M.L.M. prepared reagents, designed and carried out experiments, analyzed data, and composed and edited the manuscript. W-c.C. prepared reagents, designed and carried out experiments, analyzed data, and edited the manuscript. A.P.L. prepared reagents, carried out experiments, and analyzed data. L.A.M. prepared reagents, carried out experiments and analyzed data. C.K. designed experiments, analyzed data, and edited the manuscript. J.M.B. designed experiments and composed and edited the manuscript.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS STATEMENT

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Contributor Information

Megan L Matthews, Email: matthews@scripps.edu.

J Martin Bollinger, Jr, Email: jmb21@psu.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Godula K, Sames D. C-H bond functionalization in complex organic synthesis. Science. 2006;312:67–72. doi: 10.1126/science.1114731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herrerias CI, Yao X, Li Z, Li CJ. Reactions of C-H bonds in water. Chem. Rev. 2007;107:2546–2562. doi: 10.1021/cr050980b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Solomon EI, et al. Geometric and electronic structure/function correlations in non-heme iron enzymes. Chem. Rev. 2000;100:235–349. doi: 10.1021/cr9900275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Costas M, Mehn MP, Jensen MP, Que L., Jr Dioxygen activation at mononuclear nonheme iron active sites: Enzymes, models, and intermediates. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:939–986. doi: 10.1021/cr020628n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krebs C, Galonic Fujimori D, Walsh CT, Bollinger JM., Jr Non-heme Fe(IV)-oxo intermediates. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007;40:484–492. doi: 10.1021/ar700066p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Booker SJ. Anaerobic functionalization of unactivated C-H bonds. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2009;13:58–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.02.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bollinger JM, Jr, Broderick JB. Frontiers in enzymatic C-H-bond activation. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2009;13:51–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van der Donk WA, Krebs C, Bollinger JM., Jr Substrate activation by iron superoxo intermediates. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2010;20:673–683. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lewis JC, Coelho PS, Arnold FH. Enzymatic functionalization of carbon-hydrogen bonds. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011;40:2003–2021. doi: 10.1039/c0cs00067a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sydor PK, et al. Regio- and stereodivergent antibiotic oxidative carbocyclizations catalysed by Rieske oxygenase-like enzymes. Nat. Chem. 2011;3:388–392. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hausinger RP. Fe(II)/-α-ketoglutarate-dependent hydroxylases and related enzymes. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2004;39:21–68. doi: 10.1080/10409230490440541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ogura K, Sankawa U. Dynamic Aspects of Natural Products Chemistry. Kodansha Ltd. and Harwood Academic Publishers; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baldwin JE, Bradley M. Isopenicillin N synthase: Mechanistic studies. Chem. Rev. 1990;90:1079–1088. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vaillancourt FH, Yeh E, Vosburg DA, Garneau-Tsodikova S, Walsh CT. Nature's inventory of halogenation catalysts: Oxidative strategies predominate. Chem. Rev. 2006;106:3364–3378. doi: 10.1021/cr050313i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Galonic DP, Barr EW, Walsh CT, Bollinger JM, Jr, Krebs C. Two interconverting Fe(IV) intermediates in aliphatic chlorination by the halogenase CytC3. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2007;3:113–116. doi: 10.1038/nchembio856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matthews ML, et al. Substrate-triggered formation and remarkable stability of the C-H bond-cleaving chloroferryl intermediate in the aliphatic halogenase, SyrB2. Biochemistry. 2009;48:4331–4343. doi: 10.1021/bi900109z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McIntosh JA, et al. A Enantioselective intramolecular C–H amination catalyzed by engineered cytochrome P450 enzymes in vitro and in vivo. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:9309–9312. doi: 10.1002/anie.201304401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Surry DS, Buchwald SL. Dialkylbiaryl Phosphines in Pd-Catalyzed Amination: A User's Guide. Chem. Sci. 2011;2:27–50. doi: 10.1039/C0SC00331J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cho SH, Kim JY, Kwak J, Chang S. Recent advances in the transition metal-catalyzed twofold oxidative C-H bond activation strategy for C-C and C-N bond formation. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011;40:5068–5083. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15082k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Price JC, Barr EW, Hoffart LM, Krebs C, Bollinger JM., Jr Kinetic dissection of the catalytic mechanism of taurine:alpha-ketoglutarate dioxygenase (TauD) from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 2005;44:8138–8147. doi: 10.1021/bi050227c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Groves JT. Key elements of the chemistry of cytochrome P-450. The oxygen rebound mechanism. J. Chem. Ed. 1985;62:928–931. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blasiak LC, Vaillancourt FH, Walsh CT, Drennan CL. Crystal structure of the non-haem iron halogenase SyrB2 in syringomycin biosynthesis. Nature. 2006;440:368–371. doi: 10.1038/nature04544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Galonić Fujimori D, et al. Spectroscopic evidence for a high-spin Br-Fe(IV)-oxo intermediate in the alpha-ketoglutarate-dependent halogenase CytC3 from Streptomyces. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:13408–13409. doi: 10.1021/ja076454e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matthews ML, et al. Substrate positioning controls the partition between halogenation and hydroxylation in the aliphatic halogenase, SyrB2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci U.S.A. 2009;106:17723–17728. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909649106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vaillancourt FH, Yin J, Walsh CT. SyrB2 in syringomycin E biosynthesis is a nonheme FeII α-ketoglutarate- and O2-dependent halogenase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005;102:10111–10116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504412102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vaillancourt FH, Vosburg DA, Walsh CT. Dichlorination and bromination of a threonyl-S-carrier protein by the non-heme Fe(II) halogenase SyrB2. ChemBioChem. 2006;7:748–752. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200500480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kulik HJ, Drennan CL. Substrate placement influences reactivity in non-heme Fe(II) halogenases and hyroxylases. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:11233–11241. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.415570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ye S, Neese F. Nonheme oxo-iron(IV) intermediates form an oxyl radical upon approaching the C-H bond activation transition state. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S. A. 2011;108:1228–1233. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008411108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wong SD, Srnec M, Matthews ML, Liu LV, Kwak Y, Park K, Bell CB, Alp EE, Zhao J, Yoda Y, Kitao S, Seto M, Krebs C, Bollinger JM, Jr, Solomon EI. Elucidation of the Fe(IV)=O intermediate in the catalytic cycle of the halogenase SyrB2. Nature. 2013;499:320–323. doi: 10.1038/nature12304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neidig ML, et al. CD and MCD of CytC3 and taurine dioxygenase: role of the facial triad in alpha-KG-dependent oxygenases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:14224–14231. doi: 10.1021/ja074557r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Strickler SJ, Kasha M. Solvent effects on the electronic absorption spectrum of nitrite ion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1963;85:2899–2901. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huisgen R. 1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition Chemistry. Wiley; New York: 1984. pp. 1–176. Ch. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saxon E, Bertozzi CR. Cell surface engineering by a modified Staudinger reaction. Science. 2000;287:2007–2010. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5460.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kolb HC, Finn MG, Sharpless KB. Click chemistry: Diverse chemical function from a few good reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2001;40:2004–2021. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010601)40:11<2004::AID-ANIE2004>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fraústo da Silva JJR, Williams RJP. The Biological Chemistry of the Elements: the Inorganic Chemistry of life, 2nd Ed., Ch. 8: Sodium, potassium, and chlorine: osmotic control, electrolytic equilibria, and currents. USA: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barry SM, et al. Cytochrome P450-catalyzed L-tryptophan nitration in thaxtomin phytotoxin biosynthesis. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2012;8:814–816. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hyster TK, Knorr L, Ward TR, Rovis T. Biotinylated Rh(III) complexes in engineered streptavidin for accelerated asymmetric C-H activation. Science. 2012;338:500–503. doi: 10.1126/science.1226132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang Z, Zhang Y, Fu H, Jiang Y, Zhao Y. Efficient intermolecular iron-catalyzed amidation of C-H bonds in the presence of N-bromosuccinimide. Org. Lett. 2008;10:1863–1866. doi: 10.1021/ol800593p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paradine SM, White MC. Iron-catalyzed intramolecular allylic C-H amination. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:2036–2039. doi: 10.1021/ja211600g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nguyen Q, Nguyen T, Driver TG. Iron(II) bromide-catalyzed intramolecular C-H bond amination [1,2]-shift tandem reactions of aryl azides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:620–623. doi: 10.1021/ja3113565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hennessy ET, Betley TA. Complex N-heterocycle synthesis via iron-catalyzed, direct C-H bond amination. Science. 2013;340:591–595. doi: 10.1126/science.1233701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stevens BW, Lilien RH, Georgiev I, Donald BR, Anderson AC. Redesigning the PheA domain of gramicidin synthetase leads to a new understanding of the enzyme's mechanism and selectivity. Biochemistry. 2006;45:15495–15504. doi: 10.1021/bi061788m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Han JW, et al. Site-directed modification of the adenylation domain of the fusaricidin nonribosomal peptide synthetase for enhanced production of fusaricidin analogs. Biotechnol. Lett. 2012;34:1327–1334. doi: 10.1007/s10529-012-0913-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Savile CK, et al. Biocatalytic asymmetric synthesis of chiral amines from ketones applied to sitagliptin manufacture. Science. 2010;329:305–309. doi: 10.1126/science.1188934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huisman GW, Collier SJ. On the development of new biocatalytic processes for practical pharmaceutical synthesis. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2013;17:284–292. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2013.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cashin AL, Torrice MM, McMenimen KA, Lester HA, Dougherty DA. Chemical-scale studies on the role of a conserved aspartate in preorganizing the agonist binding site of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Biochemistry. 2007;46:630–639. doi: 10.1021/bi061638b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Price JC, Barr EW, Tirupati B, Bollinger JM, Jr, Krebs C. The first direct characterization of a high-valent iron intermediate in the reaction of an alpha-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase: a high-spin FeIV complex in taurine/alpha-ketoglutarate dioxygenase (TauD) from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 2003;42:7497–7508. doi: 10.1021/bi030011f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.