Summary

The role of PPARβ/δ altering AHR-dependent signaling was examined. Results demonstrate that PPARβ/δ reduces AHR-dependent signaling in keratinocytes and that this crosstalk is unique to keratinocytes and conserved between mice and humans.

Abstract

Whether peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor β/δ (PPARβ/δ) reduces skin tumorigenesis by altering aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR)-dependent activities was examined. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) increased expression of cytochrome P4501A1 (CYP1A1), CYP1B1 and phase II xenobiotic metabolizing enzymes in wild-type skin and keratinocytes. Surprisingly, this effect was not found in Pparβ/δ-null skin and keratinocytes. Pparβ/δ-null keratinocytes exhibited decreased AHR occupancy and histone acetylation on the Cyp1a1 promoter in response to a PAH compared with wild-type keratinocytes. Bisulfite sequencing of the Cyp1a1 promoter and studies using a DNA methylation inhibitor suggest that PPARβ/δ promotes demethylation of the Cyp1a1 promoter. Experiments with human HaCaT keratinocytes stably expressing shRNA against PPARβ/δ also support this conclusion. Consistent with the lower AHR-dependent activities in Pparβ/δ-null mice compared with wild-type mice, 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene (DMBA)-induced skin tumorigenesis was inhibited in Pparβ/δ-null mice compared with wild-type. Results from these studies demonstrate that PPARβ/δ is required to mediate complete carcinogenesis by DMBA. The mechanisms underlying this PPARβ/δ-dependent reduction of AHR signaling by PAH are not due to alterations in the expression of AHR auxiliary proteins, ligand binding or AHR nuclear translocation between genotypes, but are likely influenced by PPARβ/δ-dependent demethylation of AHR target gene promoters including Cyp1a1 that reduces AHR accessibility as shown by reduced promoter occupancy. This PPARβ/δ/AHR crosstalk is unique to keratinocytes and conserved between mice and humans.

Introduction

Pparβ/δ-null mice exhibit an enhanced hyperplastic response in the epidermis following treatment with the tumor promoter 2-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate compared with wild-type mice (1–3). This effect has been found in three different Pparβ/δ-null mouse models by three independent laboratories (1–3). Pparβ/δ-null primary keratinocytes, the progenitor cell type of many skin tumors, are also more proliferative than wild-type keratinocytes (4–6). These studies indicate that one function of PPARβ/δ in skin is to inhibit epidermal hyperplasia. This is consistent with the fact that ligand activation of the PPARβ/δ inhibits cell proliferation in both mouse and human skin and keratinocyte models (reviewed in refs. 7 and 8). A number of mechanisms have been elucidated that may mediate the inhibitory effect of PPARβ/δ on keratinocyte proliferation, including ubiquitin-dependent degradation of protein kinase C α (6,9), reduced MAP kinase signaling (10), induction of terminal differentiation markers (11–13), inhibition of cell cycle progression (10,14,15), increased apoptosis (4) and crosstalk with E2F signaling (15).

Given the fact that PPARβ/δ regulates epidermal cell proliferation and differentiation, it is not surprising that Pparβ/δ-null mice exhibit enhanced sensitivity and greater tumor multiplicity in a two-stage chemically induced skin cancer model compared with wild-type mice (6,11,16–18). Further, ligand activation of PPARβ/δ inhibits the onset of tumor formation, tumor incidence and tumor multiplicity in wild-type mice in two-stage skin chemical carcinogenesis bioassays. These effects require PPARβ/δ because they are not found in similarly treated Pparβ/δ-null mice (11,16,18). Although there is strong evidence that PPARβ/δ inhibits chemically induced skin cancer by inhibiting cell proliferation and inducing terminal differentiation, which would significantly modify the promotion phase of tumorigenesis, it remains unclear whether PPARβ/δ could influence the initiation of DNA damage by chemical carcinogens.

Chemical carcinogens are modified by phase I and II xenobiotic metabolizing enzymes that catalyze detoxification and excretion. Phase I enzymes, including the cytochrome P450s (CYPs), can generate DNA-reactive diol-epoxide intermediates from chemical carcinogens such as the polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) benzo[a]pyrene (B[a]P) and 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene (DMBA). These bioactivated intermediates can either form DNA adducts that may or may not be repaired, or be further conjugated by phase II enzymes to stable, detoxified derivatives (19). Although the expression of phase I and II enzymes is regulated by a number of transcription factors, expression of several key phase I and II enzymes involved in PAH metabolism are primarily regulated by the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) (reviewed in ref. 20). Thus, the AHR is considered a key modulator of chemical carcinogenesis that influences the balance between bioactivation and detoxification. The AHR exists in the cytoplasm bound to heat shock protein 90 (HSP90), p23 and hepatitis B virus X-associated protein 2 (XAP2). Similar to other soluble receptors that act dynamically, the AHR translocates to the nucleus after ligand binding, heterodimerizes with the aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator (ARNT) and binds to dioxin response elements often upstream of target genes such as Cyp1a1. The activated AHR/ARNT complex facilitates coactivator recruitment, chromatin remodeling and transcription of target genes, which include phase I and II enzymes (reviewed in ref. 20). Transcriptional regulation mediated by the AHR is dynamic because similar to other soluble receptors, the AHR is continually interacting with chromatin in the presence of endogenous and exogenous ligands and the fact that binding sites for the AHR in chromatin are continually regulated in cells by many different transcription factors and mechanisms (21–24).

Whether PPARβ/δ can alter the initiation of DNA damage caused by chemical carcinogens and influence PPARβ/δ-dependent modulation of chemically induced skin tumorigenesis has not been examined to date. Analysis of Ahr-null mice indicates that the AHR is required for the metabolism of PAH to form genotoxic DNA adducts (25–27) and PAH-induced skin tumorigenesis (26,27). However, although Ahr-null mice are completely refractory to the carcinogenic effects of some PAH, this effect is not found for all PAH (26,27). It is of interest to note that there is evidence that AHR activity can be inhibited or altered by PPARα (28–31) because there are many studies showing that all three PPARs can interact with other proteins through similar mechanisms (i.e. all three PPARs can directly bind with and interfere with various proteins (8)). Combined, this supports the hypothesis that there could be an interaction between the PPARβ/δ and the AHR. This study examined the hypothesis that PPARβ/δ reduces AHR-dependent activities associated with PAH-induced skin cancer.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

See Supplementary Materials and methods, available at Carcinogenesis Online.

Cell culture

The human embryonic kidney cell line HEK293T and HaCaT human keratinocytes, provided by Dr Yanming Wang and Dr Stuart Yuspa, respectively, were cultured in Dulbecco’s minimal essential medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 IU/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Hepa1c cells were cultured in α-modified minimal essential media supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 IU/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. All cells were cultured at 37°C and 5% carbon dioxide.

Isolation and treatment of primary mouse keratinocytes and dermal fibroblasts

Primary keratinocytes and dermal fibroblasts from wild-type and Pparβ/δ-null mice were isolated from neonatal skin and cultured as described previously (32). Keratinocytes were cultured in low calcium (0.05mM) Eagle’s minimal essential medium with 8% chelexed FBS, 100 IU/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Dermal fibroblasts were cultured in Dulbecco’s minimal essential medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 IU/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. All cells were cultured at 37°C and 5% carbon dioxide. Fibroblasts and keratinocytes for mRNA expression analyses were treated for 8h with vehicle or the indicated treatment unless otherwise stated.

In vivo studies

Wild-type or Pparβ/δ-null mice (3) in the resting phase of the hair cycle were shaved and treated with acetone (control) or the indicated PAH. Studies using mice were approved by The Pennsylvania State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Mice were euthanized and the dorsal skin regions isolated and snap frozen until further analysis.

RNA isolation and quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA was prepared from samples using RiboZol RNA Extraction Reagent (AMRESCO, Solon, OH) and the manufacturer’s recommended protocol. The mRNA encoding AHR target genes, DNA damage markers, PPARβ/δ and a PPARβ/δ target gene were measured by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) analysis as described previously (4). The relative mRNA value for each gene was normalized to the relative mRNA value for the housekeeping gene glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gapdh). The following genes were examined, with the primers described in Supplementary Table 1, available at Carcinogenesis Online: activating transcription factor 3 (Atf3), angiopoietin-like protein 4 (Angptl4), cyclooxygenase-2 (Cox2), cytochrome P450 1A1 (Cyp1a1), Cyp1a2, Cyp1b1, glutathione S-transferase alpha 1 (Gsta1), heme oxygenase 1 (Hox1), NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase 1 (Nqo1), NF-E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), p53, Pparβ/δ and UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1a2 (Ugt1a2).

Western blot analysis

Protein samples were isolated from mouse skin microsomes, primary keratinocytes or HaCaT shRNA stable cell lines as described previously (4,33). The expression of AHR, ARNT, CYP1A1, CYP1B1, microsomal epoxide hydrolase (mEH), COX2, HSP90, PPARβ/δ, XAP2, β-ACTIN and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) was examined by western blot analysis as described previously (4). Hybridization signals for specific proteins were normalized to hybridization signal for β-actin or LDH. The following antibodies were used: anti-AHR MAb Rpt1 (Affinity Bioreagents, Golden, CO), anti-ARNT, anti-CYP1A1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), anti-HSP90 (34), anti-XAP2 (Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO), anti-CYP1B1 (35), anti-human PPARβ/δ (Abcam, Cambridge, MA), anti-LDH and anti-β-actin (Rockland, Gilbertsville, PA).

B[a]P DNA adduct post-labeling

B[a]P DNA adduct formation was quantified as described previously (36–38). Briefly, triplicate 100mm dishes of wild-type or Pparβ/δ-null primary keratinocytes were treated for 24h with 1 μM B[a]P, and genomic DNA was isolated. Five microgram of genomic DNA was labeled with γ-32P-ATP and polynucleotide kinase. Two-dimensional thin layer chromatography on PCI-cellulose plates was used to separate and identify γ-32P-labeled B[a]P-adducted nucleotides compared with standards. B[a]P-DNA adducts were quantified and normalized to the total amount of nucleotides examined, and are presented as adducts per 109 nucleotides.

Photoaffinity ligand 125I-N3Br2DpD binding assay

Primary keratinocytes from wild-type and Pparβ/δ-null mice were trypsinized, pelleted and homogenized in MENG buffer (25mM 3-(N-morpholino) propane sulfonic acid (MOPS), 2mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), 0.02% NaN3 and 10% glycerol pH 7.4) containing 20mM sodium molybdate and protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, San Francisco, CA). Cytosol was obtained by centrifugation at 100 000g for 1h. All binding experiments were conducted in the dark until ultraviolet-mediated cross-linking of 2-azido-3-125I-iodo-7,8-dibromodibenzo-p-dioxin (125I-N3Br2DpD) was completed as described previously (39). Briefly, 150 µg of cytosolic protein was incubated at room temperature with increasing amounts of 125I-N3Br2DpD. Ligand was allowed to bind protein for 30min at room temperature and samples photolyzed at 8cm with 402nm ultraviolet light. Three percent dextran-coated charcoal was added to the photolyzed samples for 5 min followed by centrifugation to remove free ligand. Labeled samples were resolved using 8% acrylamide-sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane and visualized using autoradiography. Radioactive AHR bands were then excised and counted using a γ-counter to quantify radioligand binding.

Reversible ligand 125I-Br2DpD mediated AHR nuclear translocation

Wild-type and Pparβ/δ-null primary keratinocytes were cultured and treated for 1h with 2-125I-iodo-7,8-dibromo-p-dioxin (125I-Br2DpD), washed twice with Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline, trypsinized and pelleted. Nuclear translocation was examined as described previously (39). Bovine serum albumin (4.4 S) and catalase (11.3 S) were used as external markers of sedimentation in the sucrose gradients.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

Wild-type and Pparβ/δ-null primary keratinocytes were treated for 3h with vehicle or 1 μM B[a]P. Chromatin was isolated and used for chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) as described previously (40) with specific antibodies for either AHR (Enzo, Farmingdale, NY), anti-acetylated histone H4 (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY) as a positive control, or rabbit IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) as a negative control. Immunoprecipitated DNA was used for qPCR analysis to quantify occupancy of the AHR in the proximal promoter of the Cyp1a1 gene because this is a specific AHR target gene. The primers for Cyp1a1 were 5′-GTCGTTGCGCTTCTCACGCGA-3′ (forward) and 5′-CACTGAGGGAGGGGTTTGAGG-3′ (reverse). The specific values were normalized to treatment inputs and verified to be greater than rabbit IgG controls. Promoter occupancy was determined based on fold accumulation to normalized vehicle values.

Mouse complete skin carcinogenesis bioassay

Female, wild-type (+/+), Pparβ/δ-null (−/−) (3)) and Ahr-null (41), mice in the resting phase of the hair cycle (6–8 weeks of age) were shaved and topically treated weekly with 100 μg of DMBA or B[a]P or 300 μg of N-methyl-N′-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine (MNNG) dissolved in 200 μl acetone (Supplementary Table 2, available at Carcinogenesis Online). The B[a]P and DMBA dosing regimen was chosen based on previous bioassays using the C57BL/6 strain (42–44). The studies were carried out for 34 weeks (B[a]P), 27 weeks (DMBA) or 25 weeks (MNNG), respectively. The onset of lesion formation, lesion number and lesion size was assessed weekly, and mice were euthanized by overexposure to carbon dioxide at the end of the study.

Statistical analysis

In vitro data were analyzed for statistical significance using Student’s t-test, one-way or two-way analysis of variance with the Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test (Prism 5.0, GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA) or the Mann-Whitney test (DNA adducts). Tumor data were analyzed for significance using Fisher’s exact test (lesion incidence) or Student’s t-test (lesion/mouse and average lesion size). All results are reported as mean ± SEM.

Results

PPARβ/δ specifically reduces PAH-dependent signaling in the skin and keratinocytes

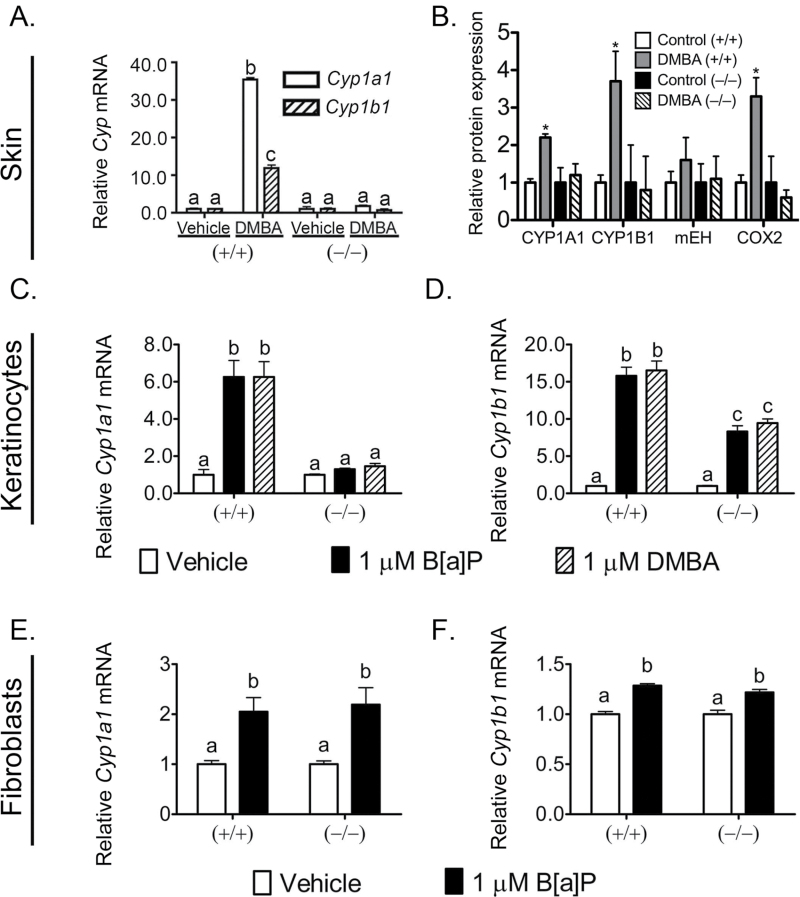

To determine if PPARβ/δ reduces PAH-dependent signaling in the skin, wild-type and Pparβ/δ-null mice were treated topically with DMBA. The expression of both CYP1A1 and CYP1B1 mRNA and protein were increased in DMBA-treated wild-type mice but this effect was not found in similarly treated Pparβ/δ-null mice (Figure 1A and B). Expression of mEH, which can also metabolize PAH (45), was not different between genotypes (Figure 1B). Expression of COX2 was increased by treatment with DMBA and this effect was not found in similarly treated Pparβ/δ-null mouse skin (Figure 1B). However, basal expression of COX2 was higher in Pparβ/δ-null mouse skin compared with wild-type (data not shown). This is consistent with a previous study (17) and could be due to PPARβ/δ-dependent repression of gene expression (46). B[a]P and DMBA both increased expression of Cyp1a1 and Cyp1b1 mRNA in wild-type keratinocytes and this effect was markedly lower in similarly treated Pparβ/δ-null keratinocytes, in particular for Cyp1a1 mRNA (Figure 1C and D). This suggests that the keratinocyte is at least one of the cell types within the epidermis where PPARβ/δ could reduce AHR-dependent effects induced by PAH.

Fig. 1.

PPARβ/δ specifically reduces PAH-induced changes in P450 expression in mouse skin and primary keratinocytes. (A and B) Wild-type (+/+) and Pparβ/δ-null (−/−) mice were topically treated with 50 μg DMBA or (C and D) primary keratinocytes and (E and F) primary dermal fibroblasts from (+/+) and (−/−) mice were treated 8h with 1 μM B[a]P or DMBA. (A) qPCR of total RNA to quantify the mRNA expression of Cyp1a1 and Cyp1b1 in response to DMBA. Values are the average normalized fold change compared with (+/+) vehicle control and represent the mean ± SEM of N = 5 biological replicates. (B) Protein expression of CYP1A1, CYP1B1, mEH, COX2 was normalized to LDH and is shown as ‘relative protein expression’. (C–F) qPCR of primary keratinocyte or primary dermal fibroblast total RNA to quantify the expression of (C and E) Cyp1a1 or (D and F) Cyp1b1. Values were normalized to the respective genotype vehicle controls and represent the mean ± SEM of N = 4 biological replicates. Values with different letters are significantly different than controls (P ≤ 0.05). *Significantly different than wild-type control (P ≤ 0.05).

The specificity of this effect was examined in primary dermal fibroblasts, the liver and primary hepatocytes to determine if this regulation is a global or tissue-specific phenomenon. Dermal fibroblasts were examined because this cell type is directly adjacent to keratinocytes. The liver and primary hepatocyte cultures were examined because they are a primary site of PAH metabolism mediated by AHR. Interestingly, B[a]P increased expression of Cyp1a1 and Cyp1b1 mRNA in mouse primary dermal fibroblasts (Figure 1E and F) and Cyp1a1 and Cyp1a2 mRNA in mouse primary hepatocytes in both genotypes (Supplementary Figure S1A and B, available at Carcinogenesis Online). Moreover, the AHR agonist β-naphthoflavone increased expression of Cyp1a1 and Cyp1a2 mRNA in mouse liver of both genotypes (Supplementary Figure S1C and D, available at Carcinogenesis Online).

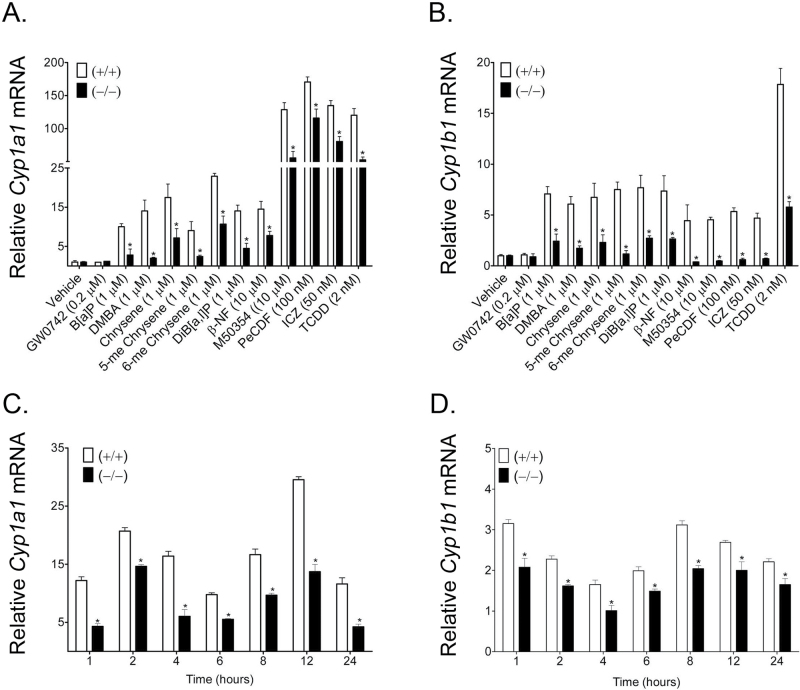

The ability of PPARβ/δ to reduce AHR-dependent signaling in response to structurally diverse PAH/AHR agonists was also examined. Treatment with 11 different PAH/AHR agonists caused an increase in expression of Cyp1a1 and Cyp1b1 mRNA and this effect was diminished in similarly treated Pparβ/δ-null keratinocytes (Figure 2A and B). This effect was even observed with the highly potent AHR full agonist 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin. It is worth noting that treatment with the PPARβ/δ agonist GW0742 did not alter the mRNA levels of Cyp1a1 or Cyp1b1 in either genotype (Figure 2A and B). Temporally, the absence of PPARβ/δ expression attenuated B[a]P-induced expression of Cyp1a1 and Cyp1b1 mRNA even over a 24 h period (Figure 2C and D). PAH exposure beyond 24 h resulted in high keratinocyte toxicity and minimal recovery of quality RNA for gene expression analyses (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Modulation of AHR-dependent signaling by PPARβ/δ by multiple PAH. Wild-type (+/+) and Pparβ/δ-null (−/−) primary keratinocytes were treated with the indicated compounds (A and B) or 1 µM B[a]P (C and D) for either 8 (A and B) or 1 to 24h (C and D). qPCR was performed using total RNA isolated from primary keratinocytes to quantify the mRNA expression of (A and C) Cyp1a1 or (B and D) Cyp1b1. Values were normalized to the respective genotype vehicle controls and represent the mean ± SEM of N = 3 biological replicates. *Significantly different than control (P ≤ 0.05).

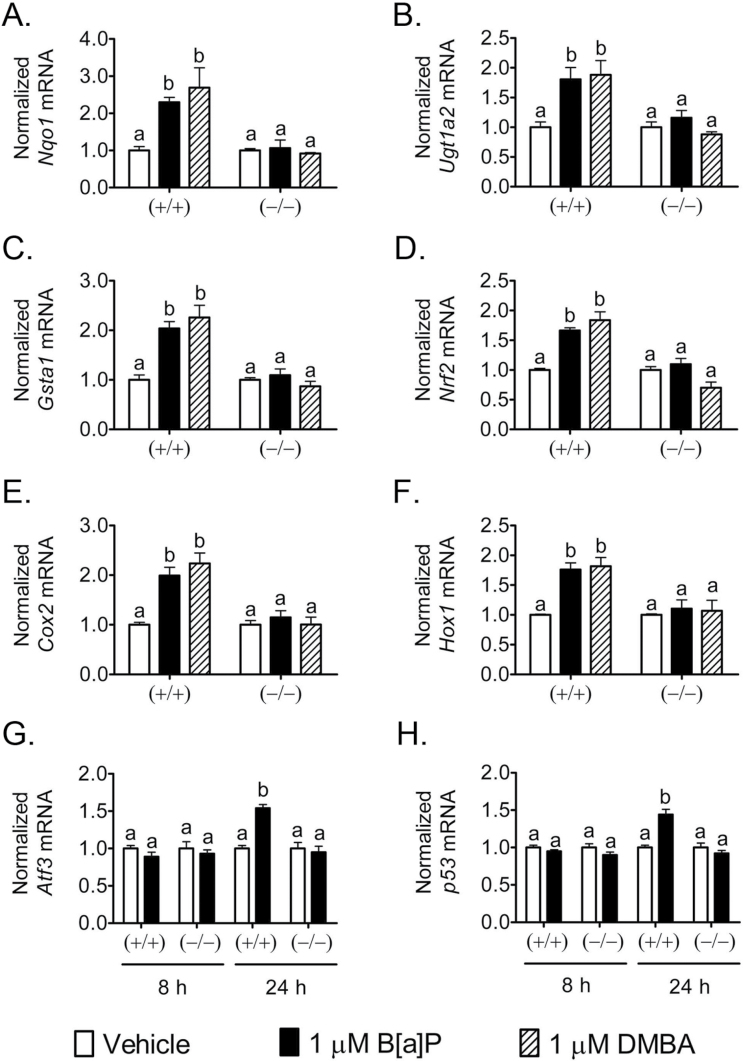

PPARβ/δ reduces phase II enzyme expression, markers of oxidative stress and markers of DNA damage

Activation of the AHR by PAH directly regulates genes encoding phase I and II xenobiotic metabolizing enzymes known as the ‘AHR gene battery’ (47). Additionally, PAHs can increase oxidative stress and modulate NRF2 activity causing changes in expression of both AHR and/or NRF2 target genes, which include phase II xenobiotic metabolizing enzymes (48). Thus, the ability of PPARβ/δ to alter AHR-dependent expression of genes encoding phase II xenobiotic metabolizing enzymes was examined. DMBA and B[a]P increased expression of mRNA encoding the phase II enzymes Nqo1, Ugt1a2 and Gsta1 in wild-type keratinocytes, an effect not found in Pparβ/δ-null keratinocytes (Figure 3A−C). DMBA and B[a]P also increased expression of mRNA encoding Nrf2, Cox2 and Hox1 in wild-type keratinocytes, but these effects were not observed in Pparβ/δ-null keratinocytes (Figure 3D−F). It is also known that DNA damage by PAHs enhances p53 signaling, particularly in the skin, and Atf3 mRNA expression has recently been identified as an indirect marker of DNA damage (49). B[a]P had no effect on expression of mRNA encoding p53 or Atf3 at 8 h post-PAH treatment but was increased in wild-type keratinocytes 24h post-PAH treatment (Figure 3G and H). These effects were not observed in Pparβ/δ-null keratinocytes (Figure 3G and H).

Fig. 3.

PPARβ/δ reduces PAH-dependent mRNA expression of phase II enzymes, oxidative stress markers and DNA damage markers. Wild-type (+/+) and Pparβ/δ-null (−/−) primary keratinocytes were treated with 1 μM B[a]P or DMBA for 8 or 24h. qPCR was performed using total RNA isolated from primary keratinocytes to quantify the expression of (A) Nqo1, (B) Ugt1a2, (C) Gsta1, (D) Nrf2, (E) Cox2, (F) Hox1, (G) Atf3 or (H) p53. Values were normalized to the respective genotype vehicle controls and represent the mean ± SEM of N = 4 biological replicates. Values with different letters are significantly different than controls (P ≤ 0.05).

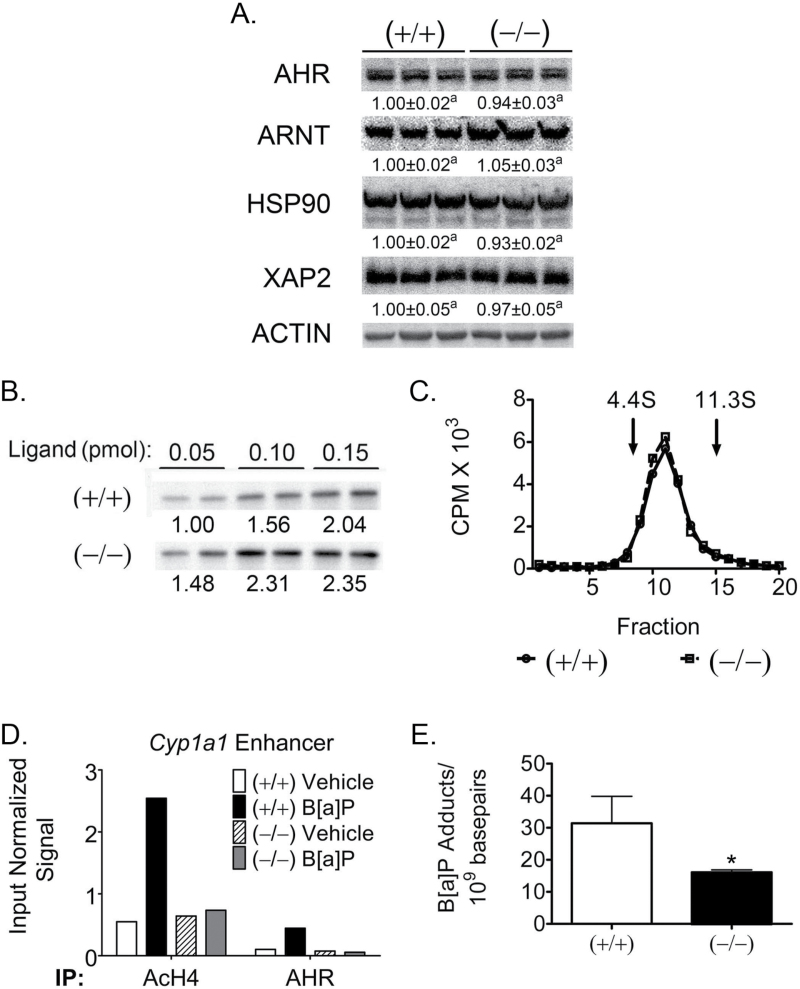

AHR nuclear function and DNA damage are reduced by PPARβ/δ

To begin to assess the mechanism(s) by which PPARβ/δ reduces AHR signaling, intrinsic functions of AHR, including protein expression, ligand binding, nuclear translocation, promoter occupancy, chromatin remodeling and DNA adduct formation were all examined. Quantitative western blot analysis showed no significant alterations in the expression of AHR, ARNT, HSP90 or XAP2 between wild-type and Pparβ/δ-null keratinocytes (Figure 4A). AHR ligand binding was assessed using a radioactive irreversible and reversibly bound dioxin derivatives (50,51). 125I-N3Br2DpD is a high-affinity AHR ligand that can be irreversibly cross-linked to AHR by ultraviolet exposure. A dose-dependent increase in ligand binding based on this assay was observed in both genotypes (Figure 4B). AHR ligand binding and function was also assessed with the reversible 125I-Br2DpD ligand binding assay used in a previous study that showed a difference in sedimentation between the unliganded AHR/HSP90 complex (9S) and ligand-bound AHR/ARNT complex (6S (50)). No differences in the amount of 6S receptor complex present in nuclear extracts were observed between wild-type and Pparβ/δ-null samples (Figure 4C).

Fig. 4.

Functional differences in AHR-dependent signaling are reduced by PPARβ/δ. (A) Quantitative protein expression of AHR and AHR accessory proteins in wild-type (+/+) and Pparβ/δ-null (−/−) primary keratinocytes normalized to ACTIN expression. Normalized expression values are fold expression relative to (+/+) and represent the mean ± SEM of N = 3 biological replicates. Values with different letters are significantly different than controls (P ≤ 0.05). (B) Level of cytosolic AHR binding of the irreversible photoaffinity ligand 125I-N3Br2DpD. Cytosol from (+/+) and (−/−) keratinocytes was incubated with increasing amounts of radioaffinity ligand with N = 2 technical replicates. Relative binding was determined by gamma counting of the excised bands from the protein blots and normalized to the (+/+) 0.05 pmol average signal. (C) AHR nuclear translocation using reversible ligand 125I-Br2DpD. (+/+) or (–/–) keratinocytes were treated 1h with 125I-Br2DpD, and nuclear extracts were isolated and subjected to sucrose density gradient ultracentrifugation. Isolated gradient factors were quantified by gamma counting, and the marker proteins bovine serum albumin (4.4S) and catalase (11.3S) were used as external standards to evaluate AHR complex status. (D) ChIP to assess promoter occupancy at the Cyp1a1 enhancer element in response to B[a]P. Keratinocytes were treated for 3h with vehicle or 1 μM B[a]P, and ChIP and qPCR quantification was performed. Results are from one biological replicate pooled from keratinocytes isolated from N = 3 neonates. Acetylated histone H4 immunoprecipitation was used as a positive marker of transcriptional activation compared with specific AHR occupancy. (E) Quantitative DNA adduct formation as determined by γ-32P-post-labeling of B[a]P-adducted nucleotides. Keratinocytes were treated 24h with 1 μM B[a]P, and DNA isolation and post-labeling were performed. Values are normalized to nucleotide content and represent the mean ± SEM of quantified number of adducts per 109 basepairs from N = 3 biological replicates. *Significantly different than control (P ≤ 0.05).

ChIP was performed to assess whether PPARβ/δ altered the ability of AHR to bind a target gene promoter and cause chromatin remodeling in response to B[a]P exposure. Compared with control, B[a]P treatment resulted in increased accumulation of acetylated histone H4 and increased occupancy of AHR in chromatin of wild-type keratinocytes containing the Cyp1a1 promoter, and these effects were not found in similarly treated Pparβ/δ-null keratinocytes. In addition, decreased DNA adducts were noted in Pparβ/δ-null keratinocytes treated with B[a]P compared with wild-type keratinocytes (Figure 4E).

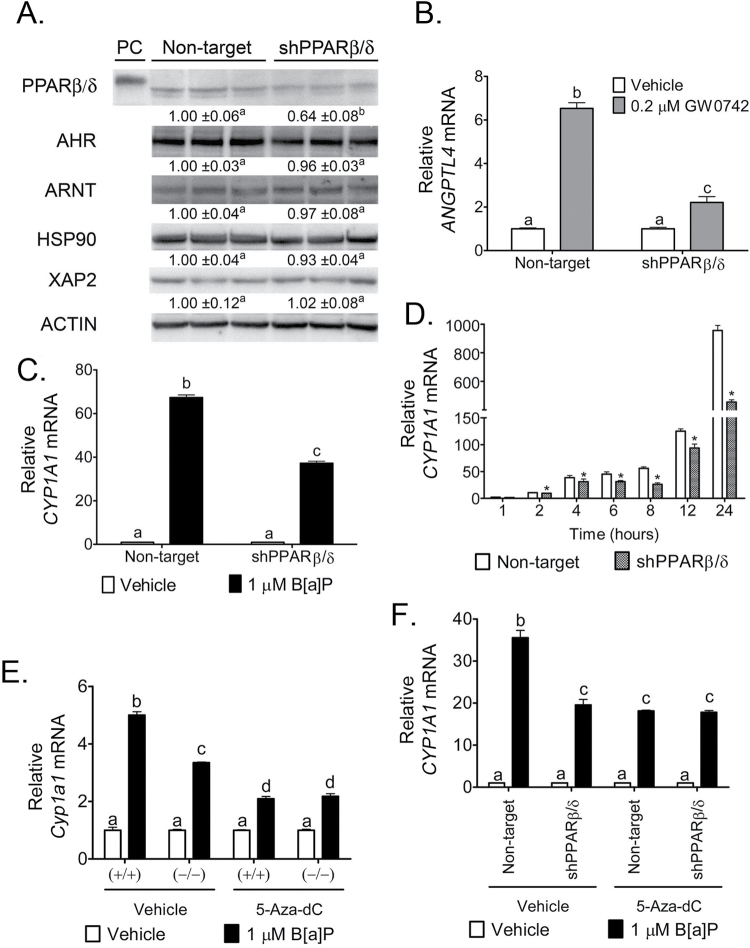

PPARβ/δ reduces AHR signaling in a human keratinocyte cell line

To examine whether PPARβ/δ-dependent modulation of AHR-dependent signaling found in mouse keratinocytes also occurs in human keratinocytes, a stable human HaCaT keratinocyte cell line was generated to knockdown PPARβ/δ expression. A 36% decrease in PPARβ/δ protein expression was observed in the shPPARβ/δ HaCaT cell line compared with control shRNA HaCaT cells (Figure 5A). Knockdown of PPARβ/δ expression significantly reduced ligand-dependent regulation of the PPARβ/δ target gene ANGPTL4 compared with controls (Figure 5B). Notably, expression of AHR, ARNT, HSP90 and XAP2 was not altered by reduced PPARβ/δ protein expression in HaCaT keratinocytes (Figure 5A). B[a]P increased expression of Cyp1a1 and Cyp1b1 mRNA in control shRNA HaCaT cells and this effect was reduced in shPPARβ/δ HaCaT cells (Figure 5C and Supplementary Figure S2A, available at Carcinogenesis Online). The attenuated expression of Cyp1a1 and Cyp1b1 mRNA was observed as early as 2h post-B[a]P treatment in shPPARβ/δ HaCaT cells and continued until 24h post-B[a]P treatment compared with control shRNA HaCaT cells (Figure 5D and Supplementary Figure S2B, available at Carcinogenesis Online).

Fig. 5.

Modulation of AHR-dependent signaling by PPARβ/δ is conserved in human HaCaT keratinocytes and possibly influenced by epigenetic modification of AHR target genes. (A) Quantitative protein expression of PPARβ/δ, AHR and AHR accessory proteins in the HaCaT shRNA cell lines normalized to ACTIN expression. Expression values are fold expression relative to the non-target cell line and represent mean ± SEM of N = 3 biological replicates. PC = positive control (lysate of COS-1 cells transfected with human PPARβ/δ expression vector). qPCR was performed using total RNA isolated from the HaCaT shRNA stable cell lines to quantify the mRNA expression of (B) ANGPTL4 in response to the PPARβ/δ ligand GW0742 or (C) CYP1A1 in response to B[a]P. qPCR was performed using total RNA isolated from the HaCaT shRNA stable cell lines to quantify temporal mRNA expression of (D) CYP1A1 in response to 1 µM B[a]P. Wild-type (+/+) and Pparβ/δ-null (−/−) primary keratinocytes as well as HaCaT shRNA cell lines were treated with 5 μM 5-Aza-dC for 72h prior to an 8h 1 μM B[a]P treatment. qPCR was performed using total RNA to quantify the expression of Cyp1a1/CYP1A1 mRNA in (E) primary keratinocytes or (F) HaCaT shRNA cell lines. Values were normalized to the respective genotype or stable cell line vehicle control and represent the mean ± SEM of N = 4 biological replicates. Values with different letters are significantly different than control (P ≤ 0.05). *Significantly different than control (P ≤ 0.05).

PPARβ/δ-dependent differences in promoter methylation of the AHR target gene, Cyp1a1

Methylation of DNA can cause silencing of gene expression and can modulate initiation and progression of cancers (reviewed in refs 52 and 53). To examine whether DNA methylation may be a mechanism by which PPARβ/δ alters the occupancy of AHR on the Cyp1a1 promoter, mouse keratinocytes or human HaCaT keratinocytes were treated with a cytosine analog, 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (5-aza-dC), which cannot be methylated. This results in ablation of methylation patterns following extended treatment (72 h) (54). B[a]P increased expression of Cyp1a1 and Cyp1b1 mRNAs in control wild-type keratinocytes and this effect was diminished in Pparβ/δ-null keratinocytes (Figure 5E and Supplementary Figure S2C, available at Carcinogenesis Online). B[a]P increased expression of Cyp1a1 and Cyp1b1 mRNAs to similar levels in keratinocytes from both genotypes co-treated with 5-aza-dC in control wild-type and Pparβ/δ-null keratinocytes (Figure 5E and Supplementary Figure S2C, available at Carcinogenesis Online). Similarly, B[a]P increased expression of CYP1A1 and CYP1B1 mRNAs in control shRNA HaCaT cells and this effect was diminished in shPPARβ/δ HaCaT cells (Figure 5F and Supplementary Figure S2D, available at Carcinogenesis Online). B[a]P increased expression of CYP1A1 and CYP1B1 mRNAs to similar levels in both control shRNA HaCaT and shPPARβ/δ HaCaT cells co-treated with 5-aza-dC (Figure 5F and Supplementary Figure S2D, available at Carcinogenesis Online).

Bisulfite sequencing was performed to directly examine whether methylation at the mouse Cyp1a1 promoter contributes to PPARβ/δ-dependent modulation of AHR signaling, in particular decreased occupancy of AHR on the Cyp1a1 promoter observed in Pparβ/δ-null keratinocytes. A putative 933 basepair CpG island at approximately –1481 to –548 basepairs upstream of the Cyp1a1 transcription start site was identified and examined (Supplementary Figure S2E, available at Carcinogenesis Online). Examination of the methylation map revealed that Pparβ/δ-null keratinocytes had more DNA methylation at the Cyp1a1 promoter compared with wild-type cells (Supplementary Figure S2E, available at Carcinogenesis Online). Increased promoter methylation is known to repress gene expression (reviewed in ref. 55), and Pparβ/δ-null keratinocytes also exhibited reduced basal mRNA levels of Cyp1a1 compared with wild-type keratinocytes (data not shown).

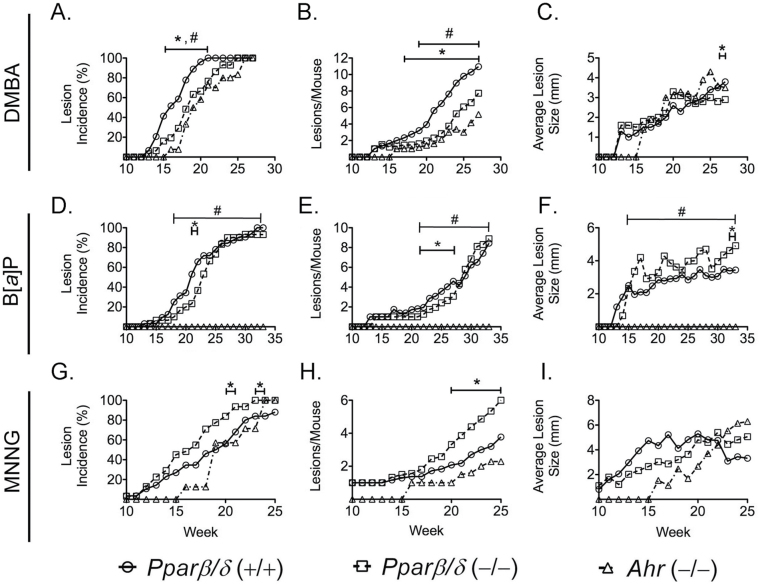

PPARβ/δ reduces complete skin carcinogenesis

Collectively, the former results suggest that PPARβ/δ could reduce PAH-induced initiation of DNA damage mediated by the AHR, and that Pparβ/δ-null mice would be resistant to PAH-induced skin cancer. This is paradoxical because previous studies showed that Pparβ/δ-null mice exhibit exacerbated skin tumorigenesis (6), and ligand activation of PPARβ/δ prevents chemically induced skin tumorigenesis using a two-stage model (6,11,16–18), which requires application of both a chemical carcinogen and a tumor promoter. Since PPARβ/δ could influence both initiation and/or promotion, a complete carcinogenesis bioassay was performed (Supplementary Table 2, available at Carcinogenesis Online). This approach was used, rather than a two-stage bioassay, to reduce the impact of a tumor promoter coapplied with the chemical carcinogen because PPARβ/δ can modulate cell proliferation and differentiation in the two-stage model (9–15) and a complete carcinogen bioassay does not require coadministration of a tumor promoter. The mechanisms by which complete carcinogens cause tumorigenesis without administration of a tumor promoter and the precise molecular pathways that cause tumor promotion in this model are not entirely understood (56). However, the complete carcinogen bioassay is highly dependent on expression of PAH metabolizing enzymes including CYP1A1, to bioactivate the PAH throughout the assay (25–27). DMBA and B[a]P were used because each require AHR-dependent bioactivation (25–27) and to cause skin cancer, at least in part (25–27). In contrast, the mutagen MNNG was used as a control because it causes skin tumorigenesis independent of AHR signaling (57).

The incidence of lesions was higher in wild-type mice compared with Pparβ/δ-null and Ahr-null mice following treatment with DMBA from weeks 15 to 21 (Figure 6A). Tumor multiplicity was higher in wild-type mice compared with Pparβ/δ-null and Ahr-null mice following treatment with DMBA from weeks 17 to 27, or from weeks 19 to 27, respectively (Figure 6B). DMBA administration resulted in larger average tumor size in wild-type mice than Pparβ/δ-null mice for the final 2 weeks of the study (Figure 6C). The incidence of lesions was also higher in wild-type mice compared with Pparβ/δ-null mice following treatment with B[a]P from weeks 21 to 22, and completely absent in Ahr-null mice compared with other two genotypes (Figure 6D). Tumor multiplicity was higher in wild-type mice compared with Pparβ/δ-null mice following treatment with B[a]P from weeks 21 to 27, whereas Ahr-null mice had no tumors (Figure 6E). B[a]P administration resulted in larger average tumor size in Pparβ/δ-null mice compared with wild-type mice during the last 2 weeks, and was markedly higher in both wild-type and Pparβ/δ-null mice compared with Ahr-null mice, which were refractory to skin tumorigenesis by B[a]P (Figure 6F). In contrast, skin tumor incidence induced by MNNG was significantly higher in Pparβ/δ-null mice compared with wild-type mice during weeks 20–21 and 23–24 (Figure 6G). Tumor multiplicity induced by MNNG was lower in wild-type and Ahr-null mice compared with Pparβ/δ-null mice during the final 5 weeks (Figure 6H). No differences in average lesion size caused by MNNG were observed between the three genotypes (Figure 6I).

Fig. 6.

Effect of PPARβ/δ on the outcome of complete carcinogenesis bioassays. Wild-type (+/+), Pparβ/δ-null (−/−) and Ahr-null (−/−) mice were topically treated weekly with 100 μg of PAH (DMBA or B[a]P) or 300 μg MNNG during a 25–33 week complete carcinogen bioassay. (A) Onset of lesion formation (the week when lesions were noted on any mouse within each group and treatment, as indicated by percentage of mice with visible lesion(s)) and incidence of lesions (the percentage of mice with visible lesion(s) on the indicated week), (B) lesion multiplicity (the average number of lesions per mouse) and (C) average lesion size in the complete carcinogen bioassay using DMBA. (D) Onset of lesion formation and incidence of lesions, (E) lesion multiplicity and (F) average lesion size in the complete carcinogen bioassay using B[a]P. (G) Onset of lesion formation and incidence of lesions, (H) lesion multiplicity and (I) average lesion size in the complete carcinogen bioassay using MNNG. *Significantly different between wild-type (+/+) and Pparβ/δ-null (−/−) mice (P ≤ 0.05). #Significantly different between wild-type (+/+) and Ahr-null (−/−) mice (P ≤ 0.05).

Discussion

Results from the present studies are the first to demonstrate that the lack of PPARβ/δ expression can reduce AHR-dependent signaling via decreased occupancy of the AHR on an AHR target gene, decreased expression of AHR-dependent target genes, decreased PAH-induced DNA adduct formation and decreased skin tumorigenicity in Pparβ/δ-null mice compared with wild-type. This is based on data obtained from two independent, complementary models: mouse wild-type and Pparβ/δ-null keratinocytes, and control and shPPARβ/δ HaCaT knockdown human keratinocytes. These effects are not due to altered expression of the AHR or AHR auxiliary protein, or altered ligand specificity for AHR. This PPARβ/δ-dependent influence on AHR signaling is unique to keratinocytes and conserved between mice and humans. Both of these models contain a ‘rescue’ component (i.e. the control cells express PPARβ/δ whereas the null cells and the shRNA cells exhibit complete ablation or markedly reduced expression of the receptor, respectively). However, additional experiments with alternative rescue approaches (i.e. reintroduce expression of PPARβ/δ in Pparβ/δ-null keratinocytes) would further strengthen the results from the present study.

The AHR is considered the master regulator of PAH-dependent tumorigenesis (reviewed in ref. 58) as Ahr-null mice are refractory to PAH-induced skin carcinogenesis (26,27). Identification of PPARβ/δ as a new modulator of AHR-dependent signaling is a novel finding. Although the AHR is essential for chemically induced tumorigenesis to bioactivate PAH (reviewed in ref. 58), increased PAH-induced tumorigenesis has also been found in phase II xenobiotic metabolizing enzyme null mice (reviewed in refs 59 and 60). Since the AHR regulates many phase I and II xenobiotic enzymes (47), results from the present studies support the hypothesis that the AHR is not the single master regulator of PAH-induced skin tumorigenesis and that PPARβ/δ that can also influence PAH-induced skin tumorigenesis. This is consistent with the results from studies showing that PAH, such as DMBA can cause some tumorigenesis in Ahr-null mice whereas Ahr-null mice are completely refractory to B[a]P-induced skin tumorigenesis (26,61). Results from the complete carcinogenesis studies indicate that PPARβ/δ can reduce PAH-induced skin cancer and the overall outcome depends on the AHR agonist used. This could be due to differences mediated by differential recruitment of coregulators to the AHR, that in turn influence expression of AHR target genes required for metabolic activation of chemical carcinogens. This hypothesis requires testing by further experimentation.

There is a complex regulatory network regulated by the AHR following agonist activation. This is illustrated by the fact that activation of the AHR by agonists not only increase expression of some phase I xenobiotic metabolizing enzymes (i.e. CYPs) (47), COX2 (62) and phase II xenobiotic metabolizing enzymes (i.e. GSTs, UGTs, NQO, etc.), but also increases oxidative stress (63), causing activation of NRF2 (64), which in turn coregulates expression of many phase II enzymes (GSTs, NQO, etc.) (64) and anti-inflammatory enzymes (i.e. HOX1) (65). Results from the present studies demonstrate that PPARβ/δ can influence some of these effects because PAH-induced expression of CYPs, COX2, NRF2, HOX1 and phase II xenobiotic metabolizing enzymes was reduced in the absence of PPARβ/δ expression compared with controls. This AHR/NRF2 pathway could be differentially influenced by various AHR agonists due to differences in the AHR agonists, differences in cofactor recruitment to the AHR and the relative contribution of NRF2-dependent signaling (48). Further studies are needed to examine this hypothesis. However, results from the present investigation also indicate that PPARβ/δ can impact the AHR/NFR2 axis, which contributes to the mechanisms by which PAH cause skin cancer.

Reduced occupancy of the AHR on a gene promoter following B[a]P treatment of Pparβ/δ-null keratinocytes compared with wild-type cells was correlated with minimal cytosine methylation in wild-type keratinocytes at the putative Cyp1a1 CpG island. In contrast, increased methylation of the Cyp1a1 promoter was found in Pparβ/δ-null keratinocytes. This difference could alter accessibility of the AHR to the Cyp1a1 promoter and explain the decrease in CYP1A1 expression following treatment with PAH in Pparβ/δ-null keratinocytes. Recent studies in mouse and human cell lines have also shown that methylation of the Cyp1a1 or Cyp1b1 promoter causes decreased AHR-mediated transcriptional activity (66–70). Thus, it is of interest to note that when global methylation of chromatin was reduced by 5-Aza-dC in PPARβ/δ knockout or knockdown keratinocytes, B[a]P induced both CYP1A1 and CYP1B1 similarly compared with wild-type cells. Although B[a]P-induced expression of the two AHR target genes was relatively lower in the cells treated with 5-Aza-dC, compared with control, it is critical to note that 5-Aza-dC alters global methylation patterns. This could influence expression of multiple genes that in turn alter AHR-dependent activity. However, because reducing methylation by treating Pparβ/δ-null keratinocytes or shPPARβ/δ HaCaT cells with 5-Aza-dC caused a similar level of B[a]P-induced expression of two AHR target genes, these data support the hypothesis that PPARβ/δ-dependent alteration of DNA methylation of AHR target genes could explain how PPARβ/δ influences AHR-dependent signaling.

The complete chemical carcinogen bioassay was used in these studies to focus more on the potential role of PPARβ/δ to influence AHR-dependent signaling during chemical carcinogenesis and to minimize the influence of coadministering a tumor promoter because it is known that PPARβ/δ can inhibit proliferation of keratinocytes stimulated by phorbol ester (4–6), and thus influence the extent of tumor promotion. MNNG treatment was included in these studies because it is a direct mutagen that causes skin tumorigenesis independent of AHR signaling. Thus, it is of interest to note that in contrast to effects observed with B[a]P and DMBA, the tumor incidence and tumor multiplicity was greater in Pparβ/δ-null mice treated with the mutagen MNNG compared with wild-type and Ahr-null mice. This difference is consistent with the findings that PPARβ/δ inhibits cell proliferation in skin (1,3,4,6,9,10,12,16) and provides more support that PPARβ/δ can inhibit tumor promotion.

Combined, results from these studies demonstrate two distinct roles for PPARβ/δ in chemically induced skin cancer. Results from the complete carcinogen bioassay using either B[a]P or DMBA as the proximal carcinogen suggest that one plausible role is that PPARβ/δ is required for optimal AHR-dependent bioactivation of a chemical carcinogen in skin. Paradoxically, results from the complete carcinogen bioassay using MNNG as the proximal carcinogen that does not require AHR-dependent bioactivation suggest that PPARβ/δ can also have a different role and inhibit tumor promotion. The latter finding is consistent with previous studies showing PPARβ/δ-dependent inhibition of two-stage skin chemical carcinogenesis and malignant conversion (6,11,16,17). Future studies are needed to elucidate the mechanisms underlying these dual, opposing roles of PPARβ/δ in chemical skin carcinogenesis.

Supplementary material

Supplementary Materials and methods, Tables 1 and 2 and Figures 1 and 2 can be found at http://carcin.oxfordjournals.org/.

Funding

National Institutes of Health (CA141029, CA124533 to J.M.P); (ES004869, ES019964 to G.H.P.).

Conflict of Interest Statement: None declared.

Supplementary Material

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- 125I-Br2DpD

2-125I-iodo-7,8-dibromo-p-dioxin

- 125I-N3Br2 DpD

2-azido-3-125I-iodo-7,8-dibromodibenzo-p-dioxin

- 5-Aza-dC

5-Aza-2′-deoxycytidine

- AHR

aryl hydrocarbon receptor

- ANGPTL4

angiopoietin-like protein 4

- ARNT

aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator

- ATF3

activating transcription factor 3

- B[a]P

benzo[a]pyrene

- ChIP

chromatin immunoprecipitation

- COX2

cyclooxygenase-2

- CpG

cytosine-phosphate-guanine

- CYP

cytochrome P450

- CYP1A1

cytochrome P450 1A1

- DiB[a,l]P

dibenzo[a,l]pyrene

- DMBA

7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- GSTA1

glutathione S-transferase alpha 1

- GW0742

(4-(((2-(3-fluoro-4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-4-methyl-5-thiazolyl)methyl)thio)-2-methylphenoxy acetic acid

- HOX1

heme oxygenase 1

- LDH

lactate dehydrogenase

- mEH

microsomal epoxide hydrolase

- MNNG

N-methyl-N′-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine

- NQO1

NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase 1

- NRF2

NF-E2-related factor 2

- PAH

polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon

- PeCDF

2,3,4,7,8-pentachlorodibenzofuran

- qPCR

quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

- PPAR

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor

- UGT1A2

UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1a2

- XAP2

hepatitis B virus X-associated protein 2.

References

- 1. Man M.Q., et al. (2007). Deficiency of PPARbeta/delta in the epidermis results in defective cutaneous permeability barrier homeostasis and increased inflammation. J. Invest. Dermatol., 128, 370–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Michalik L., et al. (2001). Impaired skin wound healing in peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)α and PPARβ mutant mice. J. Cell Biol., 154, 799–814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Peters J.M., et al. (2000). Growth, adipose, brain, and skin alterations resulting from targeted disruption of the mouse peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor β/δ. Mol. Cell. Biol., 20, 5119–5128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Borland M.G., et al. (2008). Ligand activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-β/δ (PPARβ/δ) inhibits cell proliferation in human HaCaT keratinocytes. Mol. Pharmacol., 74, 1429–1442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Genovese S., et al. (2010). A natural propenoic acid derivative activates peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-β/δ (PPARβ/δ). Life Sci., 86, 493–498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kim D.J., et al. (2004). Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor β (δ)-dependent regulation of ubiquitin C expression contributes to attenuation of skin carcinogenesis. J. Biol. Chem., 279, 23719–23727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Peters J.M., et al. (2009). Sorting out the functional role(s) of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-β/δ (PPARβ/δ) in cell proliferation and cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1796, 230–241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Peters J.M., et al. (2012). The role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors in carcinogenesis and chemoprevention. Nat. Rev. Cancer, 12, 181–195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kim D.J., et al. (2005). Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-β/δ inhibits epidermal cell proliferation by down-regulation of kinase activity. J. Biol. Chem., 280, 9519–9527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Burdick A.D., et al. (2007). Ligand activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-β/δ (PPARβ/δ) inhibits cell growth of human N/TERT-1 keratinocytes. Cell. Signal., 19, 1163–1171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bility M.T., et al. (2008). Ligand activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor β/δ (PPAR β/δ) inhibits chemically induced skin tumorigenesis. Carcinogenesis, 29, 2406–2414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kim D.J., et al. (2006). PPARβ/δ selectively induces differentiation and inhibits cell proliferation. Cell Death Differ., 13, 53–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schmuth M., et al. (2004). Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-β/δ stimulates differentiation and lipid accumulation in keratinocytes. J. Invest. Dermatol., 122, 971–983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Borland M.G., et al. (2011). Stable over-expression of PPARβ/δ and PPARγ to examine receptor signaling in human HaCaT keratinocytes. Cell. Signal., 23, 2039–2050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhu B., et al. (2012). Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor β/δ cross talks with E2F and attenuates mitosis in HRAS-expressing cells. Mol. Cell. Biol., 32, 2065–2082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bility M.T., et al. (2010). Ligand activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-β/δ and inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2 enhances inhibition of skin tumorigenesis. Toxicol. Sci., 113, 27–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kim D.J., et al. (2006). Inhibition of chemically induced skin carcinogenesis by sulindac is independent of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-β/δ (PPARβ/δ). Carcinogenesis, 27, 1105–1112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhu B., et al. (2011). Chemoprevention of chemically induced skin tumorigenesis by ligand activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-β/δ and inhibition of cyclooxygenase 2. Mol. Cancer Ther., 9, 3267–3277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Xu C., et al. (2005). Induction of phase I, II and III drug metabolism/transport by xenobiotics. Arch. Pharm. Res., 28, 249–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Beischlag T.V., et al. (2008). The aryl hydrocarbon receptor complex and the control of gene expression. Crit. Rev. Eukaryot. Gene Expr., 18, 207–250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Biddie S.C., et al. (2009). Glucocorticoid receptor dynamics and gene regulation. Stress, 12, 193–205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Biddie S.C., et al. (2010). Genome-wide mechanisms of nuclear receptor action. Trends Endocrinol. Metab., 21, 3–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hager G.L., et al. (2012). Chromatin in time and space. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1819, 631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. McNally J.G., et al. (2000). The glucocorticoid receptor: rapid exchange with regulatory sites in living cells. Science, 287, 1262–1265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kleiner H.E., et al. (2004). Role of cytochrome p4501 family members in the metabolic activation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in mouse epidermis. Chem. Res. Toxicol., 17, 1667–1674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nakatsuru Y., et al. (2004). Dibenzo[A,L]pyrene-induced genotoxic and carcinogenic responses are dramatically suppressed in aryl hydrocarbon receptor-deficient mice. Int. J. Cancer, 112, 179–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shimizu Y., et al. (2000). Benzo[a]pyrene carcinogenicity is lost in mice lacking the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 97, 779–782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shaban Z., et al. (2004). Down regulation of hepatic PPARα function by AhR ligand. J. Vet. Med. Sci., 66, 1377–1386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shaban Z., et al. (2004). PPARα-dependent modulation of hepatic CYP1A by clofibric acid in rats. Arch. Toxicol., 78, 496–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Villard P.H., et al. (2011). CYP1A1 induction in the colon by serum: involvement of the PPARα pathway and evidence for a new specific human PPREα site. PLoS One, 6, e14629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Villard P.H., et al. (2007). PPARalpha transcriptionally induces AhR expression in Caco-2, but represses AhR pro-inflammatory effects. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., 364, 896–901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dlugosz A.A., et al. (1995). Isolation and utilization of epidermal keratinocytes for oncogene research. Methods Enzymol., 254, 3–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Thomas P.E., et al. (1983). Induction of two immunochemically related rat liver cytochrome P-450 isozymes, cytochromes P-450c and P-450d, by structurally diverse xenobiotics. J. Biol. Chem., 258, 4590–4598 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Singh S.S., et al. (1993). Alterations in the Ah receptor level after staurosporine treatment. Arch. Biochem. Biophys., 305, 170–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Vidal J.D., et al. (2005). 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin induces CYP1B1 expression in human luteinized granulosa cells. Arch. Biochem. Biophys., 439, 53–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Amin S., et al. (1989). Chromatographic conditions for separation of 32P-labeled phosphates of major polynuclear aromatic hydrocarbon–deoxyribonucleoside adducts. Carcinogenesis, 10, 1971–1974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gupta R.C. (1985). Enhanced sensitivity of 32P-postlabeling analysis of aromatic carcinogen:DNA adducts. Cancer Res., 45(11 Pt 2), 5656–5662 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Reddy M.V., et al. (1986). Nuclease P1-mediated enhancement of sensitivity of 32P-postlabeling test for structurally diverse DNA adducts. Carcinogenesis, 7, 1543–1551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Perdew G.H. (1991). Comparison of the nuclear and cytosolic forms of the Ah receptor from Hepa 1c1c7 cells: charge heterogeneity and ATP binding properties. Arch. Biochem. Biophys., 291, 284–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Palkar P.S., et al. (2010). Cellular and pharmacological selectivity of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-beta/delta antagonist GSK3787. Mol. Pharmacol., 78, 419–430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fernandez-Salguero P., et al. (1995). Immune system impairment and hepatic fibrosis in mice lacking the dioxin-binding Ah receptor. Science, 268, 722–726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nesnow S., et al. (1983). Mouse skin tumor initiation-promotion and complete carcinogenesis bioassays: mechanisms and biological activities of emission samples. Environ. Health Perspect., 47, 255–268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Reiners J.J., Jr, et al. (1984). Murine susceptibility to two-stage skin carcinogenesis is influenced by the agent used for promotion. Carcinogenesis, 5, 301–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Slaga T.J., et al. (1983). Initiation-promotion versus complete skin carcinogenesis in mice: importance of dark basal keratinocytes (stem cells). Cancer Invest., 1, 425–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wiese F.W., et al. (2001). Carcinogen substrate specificity of human COX-1 and COX-2. Carcinogenesis, 22, 5–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Shi Y., et al. (2002). The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor delta, an integrator of transcriptional repression and nuclear receptor signaling. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA., 99, 2613–2618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Nebert D.W., et al. (2000). Role of the aromatic hydrocarbon receptor and [Ah] gene battery in the oxidative stress response, cell cycle control, and apoptosis. Biochem. Pharmacol., 59, 65–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Yeager R.L., et al. (2009). Introducing the “TCDD-inducible AhR-Nrf2 gene battery”. Toxicol. Sci., 111, 238–246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wang A., et al. (2003). Response of human mammary epithelial cells to DNA damage induced by BPDE: involvement of novel regulatory pathways. Carcinogenesis, 24, 225–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bradfield C.A., et al. (1988). Kinetic and equilibrium studies of Ah receptor-ligand binding: use of [125I]2-iodo-7,8-dibromodibenzo-p-dioxin. Mol. Pharmacol., 34, 229–237 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Poland A., et al. (1986). Photoaffinity labelling of the Ah receptor. Food Chem. Toxicol., 24, 781–787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Jones P.A. (1999). The DNA methylation paradox. Trends Genet., 15, 34–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Miranda T.B., et al. (2007). DNA methylation: the nuts and bolts of repression. J. Cell. Physiol., 213, 384–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Patra S.K., et al. (2009). Epigenetic DNA-(cytosine-5-carbon) modifications: 5-aza-2’-deoxycytidine and DNA-demethylation. Biochemistry. (Mosc)., 74, 613–619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Vaissière T., et al. (2008). Epigenetic interplay between histone modifications and DNA methylation in gene silencing. Mutat. Res., 659, 40–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Verma A.K., et al. (1982). Differential effects of retinoic acid and 7,8-benzoflavone on the induction of mouse skin tumors by the complete carcinogenesis process and by the initiation-promotion regimen. Cancer Res., 42, 3519–3525 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Rehman I., et al. (2000). Frequent codon 12 Ki-ras mutations in mouse skin tumors initiated by N-methyl-N’-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine and promoted by mezerein. Mol. Carcinog., 27, 298–307 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Gonzalez F.J., et al. (1998). The aryl hydrocarbon receptor: studies using the AHR-null mice. Drug Metab. Dispos., 26, 1194–1198 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Gonzalez F.J., et al. (1999). Role of gene knockout mice in understanding the mechanisms of chemical toxicity and carcinogenesis. Cancer Lett., 143, 199–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Gonzalez F.J., et al. (2003). Study of P450 function using gene knockout and transgenic mice. Arch. Biochem. Biophys., 409, 153–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Ide F., et al. (2004). Skin and salivary gland carcinogenicity of 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene is equivalent in the presence or absence of aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Cancer Lett., 214, 35–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Fritsche E., et al. (2007). Lightening up the UV response by identification of the arylhydrocarbon receptor as a cytoplasmatic target for ultraviolet B radiation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 104, 8851–8856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Tsuji G., et al. (2011). An environmental contaminant, benzo(a)pyrene, induces oxidative stress-mediated interleukin-8 production in human keratinocytes via the aryl hydrocarbon receptor signaling pathway. J. Dermatol. Sci., 62, 42–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ma Q. (2013). Role of nrf2 in oxidative stress and toxicity. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol., 53, 401–426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Shin J.W., et al. (2011). Zerumbone induces heme oxygenase-1 expression in mouse skin and cultured murine epidermal cells through activation of Nrf2. Cancer Prev. Res. (Phila)., 4, 860–870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Beedanagari S.R., et al. (2010). Role of epigenetic mechanisms in differential regulation of the dioxin-inducible human CYP1A1 and CYP1B1 genes. Mol. Pharmacol., 78, 608–616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Beedanagari S.R., et al. (2010). Differential regulation of the dioxin-induced Cyp1a1 and Cyp1b1 genes in mouse hepatoma and fibroblast cell lines. Toxicol. Lett., 194, 26–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Habano W., et al. (2009). CYP1B1, but not CYP1A1, is downregulated by promoter methylation in colorectal cancers. Int. J. Oncol., 34, 1085–1091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Nakajima M., et al. (2003). Effects of histone deacetylation and DNA methylation on the constitutive and TCDD-inducible expressions of the human CYP1 family in MCF-7 and HeLa cells. Toxicol. Lett., 144, 247–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Okino S.T., et al. (2006). Epigenetic inactivation of the dioxin-responsive cytochrome P4501A1 gene in human prostate cancer. Cancer Res., 66, 7420–7428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.