Abstract

Antimicrobial peptide LL-37 is produced in response to active vitamin D to exert immunomodulatory effects and inhibits HIV replication in vitro. To date, no studies have investigated LL-37 in HIV-infected patients. This study sought to investigate LL-37 and the relationship to 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] and HIV-related variables in this population. HIV-infected subjects and healthy controls ages 1–25 years old were prospectively enrolled in this cross-sectional study. Fasting plasma LL-37 and 25(OH)D concentrations were measured in duplicate with ELISA. HIV+ subjects (36 antiretroviral therapy (ART)-experienced subjects; 27 ART-naïve subjects) and 31 healthy controls were enrolled. Overall, 93% were black and the median age was 20 years. There was no difference in median (interquartile range) LL-37 between the HIV-infected group and controls [58.3 (46.4,69.5) vs. 51.3 (40.8,98.2) ng/ml, respectively; p=0.57]; however, the ART-experienced group had higher concentrations than the ART-naive group [66.2 (55.4,77.0) vs. 48.9 (38.9,57.9) ng/ml, respectively; p<0.001]. LL-37 was positively correlated with 25(OH)D in controls, but not in HIV-infected groups, and was positively correlated with current CD4 and ΔCD4 (current-nadir) in the ART-experienced group. After adjustment for age, race, sex, and HIV duration, the association between LL-37 and CD4 remained significant. These findings suggest that HIV and/or HIV-related variables may alter the expected positive relationship between vitamin D and LL-37 and should be further investigated.

Introduction

The prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in the HIV-infected population, as determined by blood concentrations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D], is very high, and is widespread among HIV-infected adults and children.1–3 We and others have demonstrated >90% of subjects with HIV have concentrations <30 ng/ml, which has been suggested to be optimal for vitamin D status.2,4–6 While the causes of vitamin D deficiency in HIV are multifactorial, including inadequate diet and darker skin pigmentation, certain commonly prescribed antiretroviral medications, particularly efavirenz, have been shown to interfere with normal vitamin D metabolism.2,4,5

Vitamin D is a steroid hormone that has long been known to play a critical role in the immune system, including effects on innate immunity, adaptive immunity, and levels of inflammatory cytokines, including interleukin-6 (IL-6).7–10 In non-HIV populations, an individual's vitamin D status affects their susceptibility to tuberculosis, the disease severity, and their response to treatment.11,12 Clinical studies have also shown that children with vitamin D deficiency and rickets are predisposed to respiratory infections and pneumonia, and vitamin D supplementation reduces this risk.13–16 Moreover, vitamin D deficiency has been shown to negatively impact HIV disease progression and mortality,17,18 whereas increased vitamin D concentrations inhibit HIV replication.19

More recently, studies have shown that vitamin D's effects on the immune system derive from its upregulation of the antimicrobial peptide cathelicidin, LL-37.19–22 In response to endogenously produced 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D [1,25(OH)2D], cells produce LL-37, which in turn inhibits bacteria through the disruption of the cellular membrane, but also has broad antimicrobial activity against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria as well as certain viruses and fungi. LL-37 also exerts chemotactic, immunomodulatory, and angiogenic effects, and affects serum levels of proinflammatory cytokines. Moreover, LL-37 has been shown to increase autophagy in macrophages to enhance innate immunity against viral infections,21 and in vitro LL-37 inhibits HIV replication in peripheral blood mononuclear cells including in CD4+ T cells.19,22

There are few studies that have evaluated LL-37 in vivo in non-HIV populations,23–25 and to date, there are no published studies in HIV-infected individuals despite the in vitro data suggesting that LL-37 inhibits HIV replication. Investigating LL-37 in the HIV-infected population, particularly in HIV-infected youth, where opportunity exists to optimize health earlier in life, is important. Thus, the purpose of this study was to (1) determine plasma LL-37 concentrations in HIV-infected children and young adults, (2) examine the relationship between plasma LL-37 and 25(OH)D concentrations, and (3) investigate the relationship between LL-37 and HIV-related variables, especially CD4 cell counts and CD4 restoration after antiretroviral therapy (ART). Secondary objectives were to (1) explore the relationship between LL-37 and inflammatory markers that are known to be elevated in HIV, and (2) compare the results to a healthy control group.

Materials and Methods

Study design/population

Individuals ages 1–25 years with documented HIV-1 infection who obtained their medical care through the Grady Health System in Atlanta, GA were eligible for the original, prospective, cross-sectional study. Subjects were drawn from this larger, parent study investigating the vitamin D status of HIV-infected youth and its relationship with cardiac biomarkers, inflammation, and immune restoration.4 This current analysis included all ART-naive subjects from the parent study. Antiretroviral therapy-experienced subjects and healthy controls with plasma 25(OH)D concentrations in the upper and lower quartiles were then chosen from the parent study in similar numbers to the ART-naive subjects. This allowed for the widest range of 25(OH)D to evaluate the relationship between LL-37 and vitamin D.

Patients with acute illnesses were eligible after complete resolution of symptoms for ≥1 month, while those with active inflammatory conditions or medication use known to affect inflammation were not eligible. Eligible HIV-infected patients were recruited during their regular clinic visits over a 10-month period of time (June–March). Over 95% of approached patients consented to study participation.

Healthy controls were chosen over this same time period from a larger convenience sample with similar socioeconomic demographics, which included relatives of HIV-infected patients and HIV-negative patients seen at the clinic. Controls were recruited with advertisement flyers hung in the HIV clinic and by word of mouth and selected so that the overall group matched the HIV-infected subjects in age, sex, and race. Controls were eligible if they self-reported to be free of chronic disease and had no recent or current infection. Potential subjects ≥13 years of age were screened for HIV infection before enrollment with the OraQuick Advance Rapid HIV Test (OraSure Technologies, Inc, Bethlehem, PA). Controls <13 years of age were assumed to be HIV uninfected unless they were considered at high risk for having or contracting HIV. Exclusion criteria for controls were the same as for the infected group.

The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Emory University and Grady Health Systems. Written informed consent was provided by all participants (and/or their legal guardian, if applicable). Subjects between the ages of 6 and 10 years gave verbal assent and those between 11 and 16 years gave written assent.

Clinical assessments

All HIV-infected subjects and controls (or guardians) completed questionnaires providing relevant demographic and medical information. In addition, an extensive chart review was conducted for the HIV+ subjects, including known duration of HIV infection, detailed ART history, past and current medical diagnoses, current medications, and nadir CD4 count.

Laboratory assessments

Subjects fasted for ≥8 h prior to blood sampling. Plasma was extracted and stored at −80°C until analysis without prior thawing. Plasma concentrations for LL-37 and 25(OH)D were both assessed with a specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) (Hycult Biotechnology, Uden, Netherlands and IDS, LTD, Fountain Hills, AZ, respectively) as per the manufacturer's product manual and tested in duplicate.24,25 The calculated means of the measurements were used in the analysis. Median intraassay and interassay coefficients of variation (CV) for both LL-37 and 25(OH)D were <12%. Quality control for 25(OH)D was ensured by participation in the vitamin D external quality assessment scheme (DEQAS, site 606). Laboratory personnel were blinded to clinical information.

Biomarkers that we have previously shown to be elevated in HIV-infected patients were selected.26,27 Plasma levels of the proinflammatory cytokines, soluble tumor necrosis factor-α receptors I, II (sTNFR-I, -II), and IL-6 were measured using Luminex (IL-6: Millipore, Billerica, MA; sTNFR-I, II: Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) was measured by ELISA (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI). Cellular adhesion molecules, soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (sICAM-1) and soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (sVCAM-1), were measured using Luminex (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Protocols were per the manufacturers' product manuals. Median intraassay and interassay CVs were all <10%.

CD4 counts, CD8 counts, and HIV-1 RNA were recorded from HIV-infected subjects' medical records as markers of HIV disease.

Statistical methods

Demographics, clinical characteristics, and laboratory parameters are described by HIV status. Continuous measures are described by medians/interquartile range, and nominal variables are described with frequencies/percentages. Nonparametric tests (Kruskall–Wallis for medians; chi-squared for categorical variables) were used to assess differences between groups. Spearman coefficients were used to assess correlations with LL-37. Multivariable linear regression models were then performed to determine variables independently associated with LL-37. Variables for the regression models were chosen either based on the results of the univariate analysis and/or those likely to affect LL-37. p values<0.05 were considered significant. All analyses were carried out using SAS, v.9.2 (The SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Sixty-three HIV-infected subjects (27 ART-naïve and 36 ART-experienced subjects) and 31 healthy controls were enrolled. Table 1 shows the demographic, clinical, and laboratory characteristics of the three groups. Groups were similar with regards to age, race, sex, and body mass index. The ART-naive group had significantly more males compared to the other two groups (p<0.01). All three groups had similar plasma concentrations of 25(OH)D, and almost all subjects were in the vitamin D deficient range (<20 ng/ml) as per the Institute of Medicine's guidelines.28 Table 2 shows the HIV-related characteristics for both HIV-infected groups. The minimum length of time of ART exposure in the ART-experienced group was 6 months. No HIV-infected subjects were coinfected with hepatitis C.

Table 1.

Demographics and Clinical Characteristics by Study Group

| Median (IQR) or no. (%) | HIV+ART-Exp. (N=36) | HIV+ART-naive (N=27) | Healthy controls (N=31) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 17.9 (4.6, 20.2) | 20.2 (19.1, 21.0) | 21.0 (18, 23) |

| Male sex | 21 (58%) | 23 (85%)* | 16 (52%) |

| Black race | 34 (94%) | 26 (96%) | 27 (87%) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 21.4 (20.0, 25.3) | 20.6 (19.9, 23.3) | 23.9 (21.0, 27.5) |

| 25(OH)D, ng/ml | 15.5 (10.8, 19.6) | 14.0 (12.4, 18.4) | 15.4 (11.9, 21.9) |

p<0.05.

IQR, interquartile range; ART, antiretroviral therapy; Exp., experienced; 25(OH)D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the HIV-Infected Group

| Median (IQR) or no. (%) | ART-Exp. (N=36) | ART-naive (N=27) |

|---|---|---|

| Known years of HIV | 14 (5, 17) | 2 (1, 3) |

| Perinatally infected | 27 (75%) | 1 (4%) |

| Current CD4, cells/mm3 | 431 (263, 646) | 297 (244, 476) |

| Current CD4 % | 28 (17, 32) | 19 (14, 26) |

| CD4 nadir, cells/mm3 | 184 (77, 337) | 296 (204, 480) |

| ΔCD4 (current-nadir)a | 229 (103, 342) | — |

| Current CD4/CD8 ratio countb | 0.41 (0.21, 0.55) | 0.65 (0.22, 1.07) |

| HIV-1 RNA <80 copies/ml | 29 (81%) | 0 0% |

| HIV-1 RNA copies/ml (if >80) | 5,980 (2,878, 15,018) | 15,480 (6,678, 29,378) |

| [N=8] | [N=27] | |

| Currently on ART | 30 (83%) | — |

| Currently on EFV | 13 (36%) | — |

| Cumulative NRTI duration, months | 103 (46, 135) | — |

| Cumulative EFV duration, months | 13 (0, 39) | — |

| Cumulative PI duration, months | 83 (10, 112) | — |

ΔCD4 cell count=current−nadir CD4 cell count.

Current CD4/CD8 % ratio similar.

p-values were not calculated between groups, as groups are expected to be significantly different from one another.

ART, antiretroviral therapy; Exp., experienced; EFV, efavirenz; NRTI, nucleoside/nucleotide analogue reverse transcriptase inhibitor; PI, protease inhibitor.

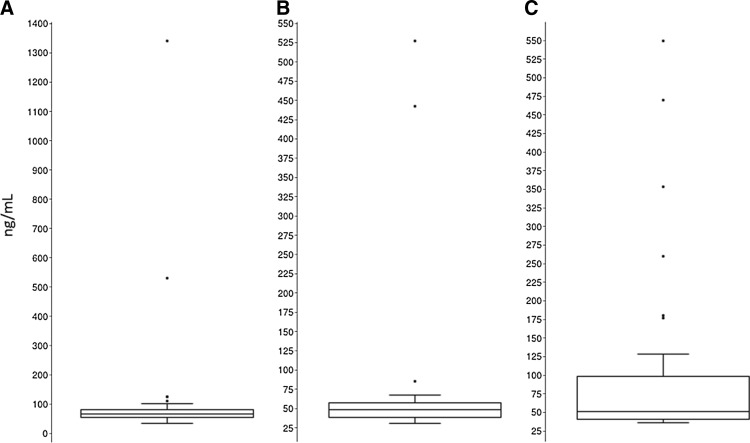

There was no difference in plasma concentrations of LL-37 between the HIV-infected group as a whole compared to the healthy controls [median (interquartile range (IQR) HIV: 58.3 (46.4, 69.5) ng/ml; controls: 51.3 (40.8, 98.2) ng/ml; p=0.57]. However, as Fig. 1 illustrates, when the HIV-infected group was evaluated separately by ART status, the ART-experienced group had a statistically significantly higher LL-37 plasma concentration compared to the ART-naive group (p<0.001). When adjusted for age, sex, race, and HIV duration, this difference did not remain statistically significant (p=0.52). The median plasma LL-37 concentration in each of the HIV-infected groups was still similar to the controls even when separated by ART status.

FIG. 1.

Box and whisker plots for LL-37 concentrations by antiretroviral treatment (ART) status. Box and whisker plots show the LL-37 concentrations for HIV-infected, ART-experienced subjects (A), HIV-infected, ART-naive subjects (B), and healthy controls (C). Each HIV group was compared to each other and to the healthy controls. The ART-experienced group had statistically higher LL-37 concentrations compared to the ART-naive group [median (IQR) ART-exp.: 66.2 (55.4, 77.0) ng/ml; ART-naive: 48.9 (38.9, 57.9) ng/ml; p<0.001]. There was no difference between the ART-experienced group and the healthy controls [median IQR controls: 51.3 (40.8, 98.2) ng/ml; p=0.68]. ART, antiretroviral therapy; Exp., experienced; IQR, interquartile range.

Next, in a univariate fashion, variables that may be associated with plasma LL-37 concentrations were investigated (Table 3). Plasma concentrations of LL-37 were positively correlated with 25(OH)D in the healthy control group, but not within either of the HIV groups. In the ART-experienced group, plasma concentrations of LL-37 were positively correlated with current CD4 counts and with ΔCD4 (current – nadir). In both HIV groups, plasma concentrations of LL-37 were strongly positively correlated with plasma levels of IL-6, but not with the other selected inflammatory markers. This relationship was heavily driven by LL-37 values >100 μg/ml. With all HIV-infected subjects considered together, the correlation decreased but remained statistically significant when these extreme values were eliminated (from R=0.58; p<0.01 to R=0.30; p=0.02). Interleukin-6 was not correlated LL-37 in the healthy controls.

Table 3.

Significant Correlations Between LL-37 and Variables of Interest

| Variable | ART-Exp. Rap | ART-naive R p | Controls R p |

|---|---|---|---|

| 25(OH)D | −0.24 | 0.02 | 0.43 |

| 0.15 | 0.93 | 0.02 | |

| Age | −0.35 | 0.11 | −0.14 |

| 0.04 | 0.59 | 0.14 | |

| CD4 count | 0.37 | 0.09 | — |

| 0.02 | 0.63 | — | |

| ΔCD4b | 0.40 | — | — |

| 0.02 | — | — | |

| IL-6 | 0.52 | 0.62 | 0.33 |

| <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.08 | |

| sTNFR-I | 0.39 | 0.29 | 0.20 |

| 0.02 | 0.15 | 0.29 | |

| sVCAM-1 | 0.03 | −0.12 | 0.36 |

| 0.87 | 0.53 | 0.04 |

R=Spearman correlation coefficient.

ΔCD4 cell count=current−nadir CD4 cell count.

Blank spaces indicate nonapplicable correlations; body mass index, CD4 nadir, CD4/CD8 ratio, CD4/CD8 % ratio, HIV-1 RNA, hsCRP, sTNFR-II, and sICAM-1 were also tested but were not significant in any group.

Exp., experienced; hsCRP, high sensitivity C-reactive protein; IL-6, interleukin-6; sTNFR-I, soluble tumor necrosis factor-α receptor-I; sTNFR-II, soluble tumor necrosis factor-α receptor-II; sVCAM-1, soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule-1; sICAM-1, soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1.

Two multivariable linear regression models were then constructed to further investigate the relationship between LL-37 and current CD4 and ΔCD4, respectively. Variables that are known to affect plasma concentrations of 25(OH)D and may also affect LL-37 were entered into each model with either current CD4 count or ΔCD4. After adjustment for age, race, sex, and HIV duration, the relationship between LL-37 and current CD4 count remained significant (p=0.03); however, the relationship between LL-37 and ΔCD4 did not (p=0.09).

Discussion

This study sought to evaluate plasma LL-37 concentrations for the first time within an HIV-infected population and investigate the relationship with plasma concentrations of 25(OH)D and HIV-related variables. LL-37 concentrations were higher in ART-experienced HIV-infected subjects compared to ART-naive, HIV-infected subjects. In the ART-experienced group, LL-37 concentrations were associated with both current CD4 counts and immune restoration after ART. Although LL-37 was positively correlated with 25(OH)D in the controls, as would be expected by known pathways, the same relationship was not seen in either HIV group. LL-37 was positively correlated with the proinflammatory cytokine IL-6 in both HIV groups.

Although vitamin D has long been known to play a critical role in the immune system, the precise mechanism has only recently been elucidated. One of the most important developments came from the study by Liu et al., showing that vitamin D-deficient human macrophages have less effective mRNA cathelicidin expression upon toll-like receptor stimulation.20 In response to endogenously produced 1,25(OH)2D, macrophages produce the antimicrobial peptide cathelicidin, LL-37, which increases autophagy in macrophages to enhance innate immunity. This response is particularly important in controlling microbes such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis, but also appears to inhibit HIV replication as well, including in CD4+ lymphocytes.11,12,21,22

Another more recent study showed that the interaction between vitamin D, LL-37, and HIV may be more complicated than previously thought. Campbell et al. demonstrated that exposing macrophages with 1,25(OH)2D in vitro induces autophagy and inhibits HIV-1 replication.19 However, exposing macrophages with LL-37 at the concentrations found to be elicited by macrophages in response to physiological concentrations of 1,25(OH)2D in vitro, and in the absence of 1,25(OH)2D, LL-37 is unable to induce autophagy and actually enhances HIV-1 replication. Conversely, at concentrations of LL-37 higher than those produced by macrophages in vitro in response to physiological concentrations of 1,25(OH)2D, but at concentrations found in the plasma of healthy individuals, they observed the inhibition of HIV-1. The authors suggest that perhaps other peptides are at play in addition to just LL-37 in controlling macrophage autophagy and HIV replication.

This latter study may explain why we did not observe the expected relationship between 25(OH)D and LL-37 in the HIV groups. There may be additional peptides at play that obscure this pathway, particularly in the setting of HIV infection. However, we did observe a link between LL-37 and both current CD4 counts and ΔCD4 in HIV-infected subjects who have been on ART. This is consistent with the in vitro data that show that LL-37 inhibits HIV replication, including in CD4+ cells. Studies evaluating the relationship between vitamin D status and CD4 counts have been conflicting.2,4,29–34 Thus, plasma concentrations of LL-37 may be a more direct link to CD4 counts than circulating concentrations of 25(OH)D.

Although we demonstrated a link between LL-37 and both current CD4 counts and ΔCD4 count in univariate analysis, only the current CD4 count remained significant after adjustment for age, sex, race, and HIV duration. Statistically, one typically adjusts for variables that are associated with the outcome (in this case, LL-37). However, it is unknown what affects LL-37 in vivo. Thus, we chose variables that are known to affect plasma concentrations of 25(OH)D. With this approach, ΔCD4 did not remain significant. This is likely due to the small sample size and the relatively large number of variables we included in the regression; however, it may be due to the fact that we have adjusted for the wrong variables. For example, genetic variants may also play a role.35 As a result, more studies are needed to further evaluate the relationship between LL-37, CD4 counts, immune restoration after ART, and disease progression in HIV-infected subjects. In particular, well-designed, randomized, placebo-controlled vitamin D supplementation studies in subjects with a range of CD4+ cell counts that include LL-37 assessments are needed to answer some of these critical questions.

It is unclear in this current study as to why the relationship between LL-37 and current CD4 counts, as well as increased LL-37 concentrations, was seen in ART-experienced, HIV-infected subjects compared to ART-naive subjects (although this did not remain significant after adjusting for several variables, including HIV duration). One explanation may be that other factors specific to one of the HIV groups, such as the degree of immune activation, inflammation, and/or the addition of ART, change the concentrations of LL-37 and/or alter its function. For example, since certain antiretrovirals interfere with vitamin D metabolism,2,4,5 perhaps there is an alternate, compensatory pathway to produce adequate concentrations of LL-37. We did assess the relationship between LL-37 and CD4/CD8 ratio as a crude marker of immune activation36; however, no significant relationship was seen. In future studies, evaluating additional immune activation markers, such as those expressed from monocytes/macrophages, would be important. Although there was no significant difference between the ART-experienced, HIV-infected subjects and the healthy controls, this appeared to be a function of a few outliers in the latter group. Additional studies are needed to determine if the increased plasma concentrations of LL-37 in ART-experienced, HIV-infected subjects are real and what specific causes may be at play.

There was a strong relationship between plasma concentrations of LL-37 and IL-6, but not the other measured inflammatory markers, in both the HIV groups. This was partly driven by the LL-37 outliers, but remained significant even when they were removed. Interleukin-6 is an immune protein with a wide range of functions from key roles in acute-phase protein induction to B and T cell growth and differentiation. Many of the cells that produce IL-6 also produce LL-37, including T cells, macrophages, and epithelial cells.37–39 Interleukin-6 has also been shown to be elevated in HIV infection26. Thus, it is reasonable to think that LL-37 and IL-6 interact with one another or one affects the other in HIV. In fact, this relationship has been previously demonstrated in other populations40 and in vitro.41 This is an important finding that deserves further investigation, including evaluating functional links between IL-6 and LL-37.

There are several important limitations to this study. Foremost, this was a cross-sectional study with a relatively small number of subjects, which limits the conclusions one can draw from these data. Given the small number of subjects in the ART-experienced group, it was impossible to evaluate the effects of specific antiretrovirals or ART classes on LL-37 concentrations. In addition, the subjects spanned a wide age range, including many younger and perinatally infected subjects. However, this population may be the ones who would benefit the most from interventions that would maximize immune restoration induced by ART and maintain CD4 counts, given the number of decades that they will live with HIV. Likewise, the majority of subjects were black. But, again, this population is at high risk for vitamin D deficiency and may benefit the most by optimizing vitamin D status, and thus LL-37 concentrations. Importantly, the normal plasma concentrations for LL-37 are not currently known, and LL-37 measured in plasma may not reflect tissue or intracellular concentrations. Finally, the investigation between LL-37 and 25(OH)D maybe be incomplete since all subjects had suboptimal concentrations of 25(OH)D.

These exploratory data are novel and shed light onto the role that LL-37 may play in HIV. LL-37 concentrations were higher in ART-experienced compared to ART-naive subjects, and, notably, were associated with CD4 counts and immune restoration after treatment in this former group. Importantly, LL-37 was associated with the proinflammatory cytokine IL-6 in both HIV groups but not in controls, whereas LL-37 was associated with 25(OH)D in healthy controls but not in either HIV group. These data suggest that HIV infection and/or HIV-related variables may modify the expected relationship between vitamin D and LL-37. Likewise, LL-37 may affect the degree of inflammation seen in HIV-infected patients, which is known to alter the risk of many long-term HIV-related complications. More research is urgently needed to better characterize the role of LL-37 within the HIV population.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by research grants from GlaxoSmithKline; Emory-Egleston Children's Research Center; Emory's Center for AIDS Research (P30 AI050409); the National Institute of Child Health and Development at the National Institutes of Health (K23 HD069199 to A.R.E. and R01 HD070490 to G.A.M.); the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases at the National Institutes of Health (K23 AR054334 to V.T.); National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (UL1 TR000454 to V.T. and T.R.Z.); and National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Disease at the National Institutes of Health (K24 DK096574 to T.R.Z.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Data in part were presented previously at the 14th International Workshop on Adverse Drug Reactions and Co-morbidities in HIV, Washington D.C., July 2012, and published as an abstract as Ross (Eckard) AC, Judd SE, Alvarez JA, Ziegler TR, Hao L, Seaton L, McComsey GA, and Tangpricha V: The immunomodulatory peptide, LL-37, is associated with CD4 cell counts and immune restoration in HIV-infected youth. Antiviral Ther 2012;17(Suppl 2):A19.

Author Disclosure Statement

A.R.E. has received research funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cubist Pharmaceuticals, and GlaxoSmithKline, and has served as an advisor to Gilead. G.A.M. serves as a consultant and speaker for and has received research funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and Tibotec. G.A.M. currently chairs a DSMB for a Pfizer-funded study.

References

- 1.Stephensen CB, Marquis GS, Kruzich LA, Douglas SD, Aldrovandi GM, and Wilson CM: Vitamin D status in adolescents and young adults with HIV infection. Am J Clin Nutr 2006;83(5):1135–1141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ross AC, Judd S, Kumari M, et al. : Vitamin D is linked to carotid intima-media thickness and immune reconstitution in HIV-positive individuals. Antivir Ther 2011;16(4):555–563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rutstein R, Downes A, Zemel B, Schall J, and Stallings V: Vitamin D status in children and young adults with perinatally acquired HIV infection. Clin Nutr 2011;30(5):624–628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eckard AR, Judd SE, Ziegler TR, et al. : Risk factors for vitamin D deficiency and relationship with cardiac biomarkers, inflammation and immune restoration in HIV-infected youth. Antivir Ther 2012;17(6):1069–1078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown TT. and McComsey GA: Association between initiation of antiretroviral therapy with efavirenz and decreases in 25-hydroxyvitamin D. Antivir Ther 2010;15(3):425–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holick MF: Vitamin D deficiency. N Engl J Med 2007;357(3):266–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schleithoff SS, Zittermann A, Tenderich G, Berthold HK, Stehle P, and Koerfer R: Vitamin D supplementation improves cytokine profiles in patients with congestive heart failure: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2006;83(4):754–759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kamen DL. and Tangpricha V: Vitamin D and molecular actions on the immune system: Modulation of innate and autoimmunity. J Mol Med (Berl) 2010;88(5):441–450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Etten E, Stoffels K, Gysemans C, Mathieu C, and Overbergh L: Regulation of vitamin D homeostasis: Implications for the immune system. Nutr Rev 2008;66(10Suppl 2):S125–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khazai N, Judd SE, and Tangpricha V: Calcium and vitamin D: Skeletal and extraskeletal health. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2008;10(2):110–117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilkinson RJ, Llewelyn M, Toossi Z, et al. : Influence of vitamin D deficiency and vitamin D receptor polymorphisms on tuberculosis among Gujarati Asians in west London: A case-control study. Lancet 2000;355(9204):618–621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davies PD, Brown RC, and Woodhead JS: Serum concentrations of vitamin D metabolites in untreated tuberculosis. Thorax 1985;40(3):187–190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cannell JJ, Hollis BW, Zasloff M, and Heaney RP: Diagnosis and treatment of vitamin D deficiency. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2008;9(1):107–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rehman PK: Sub-clinical rickets and recurrent infection. J Trop Pediatr 1994;40(1):58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams B, Williams AJ, and Anderson ST: Vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency in children with tuberculosis. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2008;27(10):941–942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muhe L, Lulseged S, Mason KE, and Simoes EA: Case-control study of the role of nutritional rickets in the risk of developing pneumonia in Ethiopian children. Lancet 1997;349(9068):1801–1804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mehta S, Giovannucci E, Mugusi FM, et al. : Vitamin D status of HIV-infected women and its association with HIV disease progression, anemia, and mortality. PLoS One 2010;5(1):e8770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Viard JP, Souberbielle JC, Kirk O, et al. : Vitamin D and clinical disease progression in HIV infection: Results from the EuroSIDA study. AIDS 2011;25(10):1305–1315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Campbell GR. and Spector SA: Hormonally active vitamin D3 (1alpha,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol) triggers autophagy in human macrophages that inhibits HIV-1 infection. J Biol Chem 2011;286(21):18890–18902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu PT, Stenger S, Tang DH, and Modlin RL: Cutting edge: Vitamin D-mediated human antimicrobial activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis is dependent on the induction of cathelicidin. J Immunol 2007;179(4):2060–2063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yuk JM, Shin DM, Lee HM, et al. : Vitamin D3 induces autophagy in human monocytes/macrophages via cathelicidin. Cell Host Microbe 2009;6(3):231–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bergman P, Walter-Jallow L, Broliden K, Agerberth B, and Soderlund J: The antimicrobial peptide LL-37 inhibits HIV-1 replication. Curr HIV Res 2007;5(4):410–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grossmann RE, Zughaier SM, Liu S, Lyles RH, and Tangpricha V: Impact of vitamin D supplementation on markers of inflammation in adults with cystic fibrosis hospitalized for a pulmonary exacerbation. Eur J Clin Nutr 2012;66(9):1072–1074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jeng L, Yamshchikov AV, Judd SE, et al. : Alterations in vitamin D status and anti-microbial peptide levels in patients in the intensive care unit with sepsis. J Transl Med 2009;7:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamshchikov AV, Kurbatova EV, Kumari M, et al. : Vitamin D status and antimicrobial peptide cathelicidin (LL-37) concentrations in patients with active pulmonary tuberculosis. Am J Clin Nutr 2010;92(3):603–611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ross AC, Rizk N, O'Riordan MA, et al. : Relationship between inflammatory markers, endothelial activation markers, and carotid intima-media thickness in HIV-infected patients receiving antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis 2009;49(7):1119–1127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ross AC, Armentrout R, O'Riordan MA, et al. : Endothelial activation markers are linked to HIV status and are independent of antiretroviral therapy and lipoatrophy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2008;49(5):499–506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Institute of Medicine (U.S.): Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D. The National Academies Press, Washington, D.C., 2011 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Luis DA, Bachiller P, Aller R, et al. : [Relation among micronutrient intakes with CD4 count in HIV infected patients]. Nutr Hosp 2002;17(6):285–289 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stein EM, Yin MT, McMahon DJ, et al. : Vitamin D deficiency in HIV-infected postmenopausal Hispanic and African-American women. Osteoporos Int 2011;22(2):477–487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Teichmann J, Stephan E, Discher T, et al. : Changes in calciotropic hormones and biochemical markers of bone metabolism in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Metabolism 2000;49(9):1134–1139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van den Bout-van den Beukel CJ, van den Bos M, Oyen WJ, et al. : The effect of cholecalciferol supplementation on vitamin D levels and insulin sensitivity is dose related in vitamin D-deficient HIV-1-infected patients. HIV Med 2008;9(9):771–779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arpadi SM, McMahon D, Abrams EJ, et al. : Effect of bimonthly supplementation with oral cholecalciferol on serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations in HIV-infected children and adolescents. Pediatrics 2009;123(1):e121–126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kakalia S, Sochett EB, Stephens D, Assor E, Read SE, and Bitnun A: Vitamin D supplementation and CD4 count in children infected with human immunodeficiency virus. J Pediatr 2011;159(6):951–957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Powe CE, Evans MK, Wenger J, et al. : Vitamin D-binding protein and vitamin D status of black Americans and white Americans. N Engl J Med 2013;369(21):1991–2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Serrano-Villar S, Gutierrez C, Vallejo A, et al. : The CD4/CD8 ratio in HIV-infected subjects is independently associated with T-cell activation despite long-term viral suppression. J Infect 2013;66(1):57–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ray A, Tatter SB, Santhanam U, Helfgott DC, May LT, and Sehgal PB: Regulation of expression of interleukin-6. Molecular and clinical studies. Ann NY Acad Sci 1989;557:353–361; discussion 361–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Frohm Nilsson M, Sandstedt B, Sorensen O, Weber G, Borregaard N, and Stahle-Backdahl M: The human cationic antimicrobial protein (hCAP18), a peptide antibiotic, is widely expressed in human squamous epithelia and colocalizes with interleukin-6. Infect Immun 1999;67(5):2561–2566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Krueger J, Ray A, Tamm I, and Sehgal PB: Expression and function of interleukin-6 in epithelial cells. J Cell Biochem 1991;45(4):327–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Inomata M, Into T, and Murakami Y: Suppressive effect of the antimicrobial peptide LL-37 on expression of IL-6, IL-8 and CXCL10 induced by Porphyromonas gingivalis cells and extracts in human gingival fibroblasts. Eur J Oral Sci 2010;118(6):574–581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pistolic J, Cosseau C, Li Y, et al. : Host defence peptide LL-37 induces IL-6 expression in human bronchial epithelial cells by activation of the NF-kappaB signaling pathway. J Innate Immun 2009;1(3):254–267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]