Abstract

The canonical double-stranded RNA (dsRNA)-binding domain (dsRBD) is composed of an α1-β1-β2-β3-α2 secondary structure that folds in three-dimensions to recognize dsRNA. Recently, structural and functional studies of divergent dsRBDs revealed adaptations that include intra- and/or inter-molecular protein interactions, sometimes in the absence of detectable dsRNA-binding ability. We describe here how discrete dsRBD components can accommodate pronounced amino-acid sequence changes while maintaining the core fold. We exemplify the growing importance of divergent dsRBDs in mRNA decay by discussing Dicer, Staufen 1 and 2, TARBP2, PACT and DGCR8 proteins, and other steps of RNA metabolism by discussing DHX30 and dsRBD-like fold-containing proteins that have ribosomal-related functions. We also elaborate on the computational limitations to discovering yet-to-be-identified divergent dsRBDs.

Keywords: double-stranded RNA-binding domain (dsRBD), divergent dsRBDs, degenerate dsRBDs, dsRBD-protein interactions, mRNA decay, RNA metabolism

Features of dsRBD folds that bind RNA

Human cells contain an estimated 30 proteins that contain a double-stranded RNA-binding domain (dsRBD), and certainly more exist that have yet to be discovered (see below). These proteins can work in synergy with the dsRNAs to which they bind to edit, unwind, transport or degrade. Alternatively, they can become activated upon dsRNA binding so as to function more globally. There are a number of examples of dsRBD-containing proteins that form homodimers or heterodimers with another dsRBD-containing protein, sometimes but not always via their dsRBDs. This expands the functions of dsRBD-containing proteins and also illustrates the utility of the dsRBD fold beyond binding dsRNA.

Double-stranded RNA (dsRNA)-binding domains (dsRBDs, also called DRBDs, RBDs, DRMs, dsRBMs, DSRMs or DRBMs, where “M” represents motif) are commonly ~68 amino acids and adopt an α1-L1-β1-L2-β2-L3-β3-L4-α2 secondary structure, where L specifies a loop [1]. In 3D, dsRBDs have two α-helices that overlap in a “y” shape to form an α1-α2 face that packs against an anti-parallel β1-β2-β3 sheet (Figures 1A-C). dsRBDs are distinct from single-stranded RNA (ssRNA)-recognition motifs (RRMs), which also have α-helices and an anti-parallel β-sheet on opposing sides of their β1-α1-β2-β3-α2-β4 fold [2]. To date, the NMR and/or X-ray crystallographic structures of >30 dsRBDs are known, seven as dsRBD-dsRNA complexes [1].

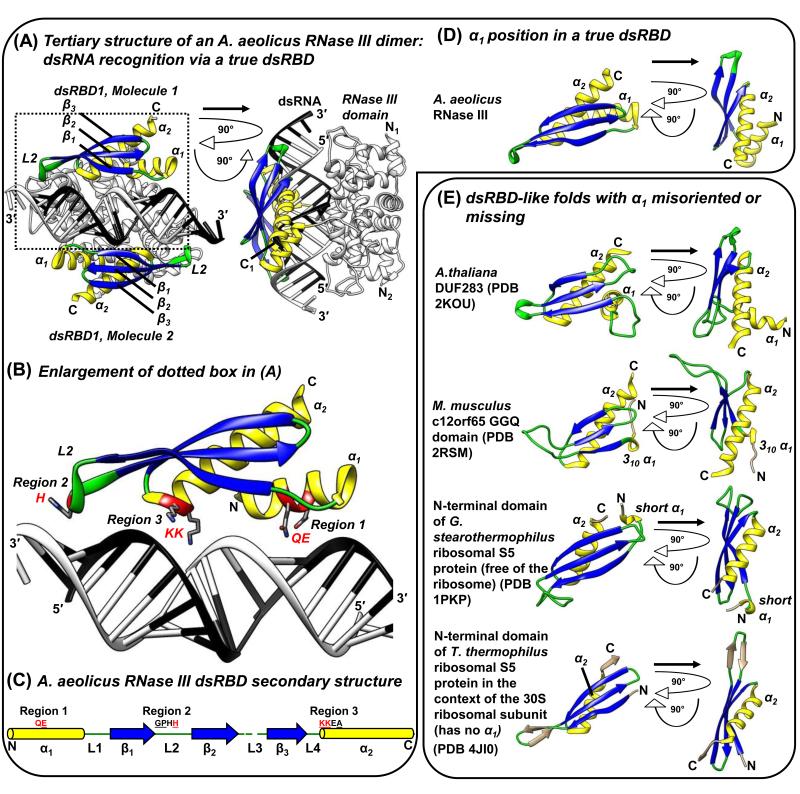

Figure 1. A representative true dsRBD bound to dsRNA and examples of α1 variations. (A-D).

Aquifex aeolicus RNase III dsRBD as a representative true dsRBD. (A) The X-ray crystal structure of an A. aeolicus RNase III dimer bound to dsRNA (PDB 2NUG; [3]). dsRBD α-helices are yellow, β-strands blue, and loops green here and throughout. The rest of the protein structure is white with β-strands black. dsRNA is black and white. Secondary structure elements are indicated. The right image is rotated 90° on the z and y axes relative to the left image. (B) Close-up of the dotted-boxed region in (A), specifying conserved motifs within Regions 1-3 of true dsRBDs that make direct contacts with dsRNA: QE of Region 1 contacts the dsRNA minor groove; H of the GPxH motif (GPHH for A. aeolicus RNase III) of Region 2 contacts a minor groove that is situated one dsRNA helical turn away from Region 1; and KK of the KKxAK motif of Region 3 (KKEA for A. aeolicus RNase III) interacts with the intermediate major groove [1, 3, 4]. (C) Secondary structure schematic of the A. aeolicus RNase III true dsRBD [3]. The relative positions and identities of dsRNA-interacting Regions 1-3 are indicated. Underlined residues match the canonical dsRBD Regions 1-3. Consensus sequences for true dsRBDs are E (sometimes QE) for Region 1, GPxH for Region 2, and KKxAK for Region 3 [1, 3]. Red residues make direct contacts with dsRNA in (B). (D) A. aeolicus RNase III dsRBD structure [3] to exemplify true dsRBD α1 length and position. (E) Examples of α1 variations in dsRBD or dsRBD-like proteins.

Three canonical dsRBD Regions within the α1-β1-β2-β3-α2 topology contain conserved sequence motifs that recognize A-form dsRNA (Figures 1A-C) [1, 3, 4]. Regions 1 and 2 together span two sequential dsRNA minor grooves by recognizing ribose sugars through a conserved Region 1 glutamate from α1, and a Region 2 GPxH (x is any amino acid) motif from L2. The positively charged KKxAK of Region 3 from the N-terminus of α2 concomitantly recognizes the phosphate backbone of the intermediate major groove [1, 4].

In support of base-specific readout by dsRBDs, dsRBD1 and 2 of adenosine deaminase acting on RNA 2 (ADAR2) uses an α1 side-chain and an L2 main-chain carboxyl moiety to contact dsRBD-specific minor groove bases that reside a specific distance apart and/or in a particular register [1, 5, 6]. α1 can also confer RNA-structure readout to some dsRBDs by interacting with the minor groove of loops at the apex of hairpin RNA [6-9]. Bulge-containing bent dsRNA can be straightened to the preferred A-form by dsRBD-containing proteins, for example protein kinase RNA-activated (PKR) [10]. When positioned in tandem, dsRBDs can have added functions. For example, the two N-terminal-most dsRBDs of Homo sapiens trans-activation responsive RNA-binding protein 2 (TARBP2), H. sapiens protein activator of PKR (PACT), and Drosophilia melanogaster Loquacious (Loqs) isoform B (R3D1-L) move along the length of dsRNA in an ATP-independent manner, whereas just one dsRBD cannot [11].

Conserved hydrophobic sidechains rigidify the α1-β1-β2-β3-α2 fold and are largely distinct from dsRNA-binding residues [1]. However, comparing structures of apo and dsRNA-bound dsRBDs reveals that loops such as L2 can transition from being flexible to rigid upon dsRNA binding [12]. As an exception, the dsRBD of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae RNase III Rnt1p undergoes a conformational change upon binding a dsRNA apex loop via an extended hydrophobic core contributed by α1 and L1 discussed more below [8, 13, 14]. To be considered a dsRBD, these central rigid interactions must be conserved. However, provided that the basic fold is maintained, variations can manifest in the amino acids that comprise the fold, in the length of any of the four loops, and/or in dsRNA-interacting residues that reside on the surface of the dsRBD fold.

Along with the first true dsRBD consensus sequence discovered in 1992, termed “type-A” [15], “type-B” dsRBDs were defined as a subclass that primarily resemble the L4-α2 regions of true dsRBDs [15, 16]. Today, the dsRBD-like collection is larger due to sophisticated motif- and domain-detection software and an increased number of annotated genomic sequences. The InterPro database (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/) uses four different discovery programs, each with its own set of algorithms, to identify domains and/or motifs in proteins: Gene3D (http://gene3d.biochem.ucl.ac.uk/Gene3D/), SMART (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/), Prosite (http://prosite.expasy.org/) and Pfam (http://pfam.sanger.ac.uk/). All four programs unanimously identify canonical but not divergent dsRBDs using default search parameters (Table 1). For example, human Staufen 1 (STAU1) dsRBD5, which constitutes the only type-B dsRBD structure solved to date ([17]; see below), completely escapes identification (Table 1). Here, we use the term “black sheep” to describe those dsRBDs that are not found by all four discovery programs or, more rarely, are recognized by all four programs but nonetheless deviate from a true dsRBD by either failing to conform to the canonical ~68-amino acid dsRBD fold and/or failing to bind dsRNA. See Box 1 for contrasting examples that further clarify dsRBD distinctions.

Table 1. List of known and putative dsRBD folds in human proteins, and databases that identify them.

| Identified in InterPro database as a dsRBDd |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein / UniProtKB accession numbera |

Amino acid number in representative isoformb |

dsRBD nomenclature |

Amino acids in dsRBD (dsRBD size)c |

Gene3D (CATH) |

SMART | Prosite | Pfam |

| A1CF / Q9NQ94 | 594 | 1 | 446-523 (78) | Y | N | N | N |

| ADAD1 / Q96M93 | 576 | 1 | 96-164 (69) | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| ADAD2 / Q8NCV1 | 583 | 1 | 115-181 (67) | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| ADAR1 / P55265 | 1226 | 1 | 502-571 (70) | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 2 | 614-682 (69) | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||

| 3 | 725-794 (70) | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||

| ADAR2 / P78563 | 741 | 1 | 78-146 (69) | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 2 | 232-299 (68) | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||

| ADAR3 / Q9NS39 | 739 | 1 | 125-193 (69) | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 2 | 274-342 (69) | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||

| CDKN2AIP / Q9NXV6 | 580 | 1 | 462-537 (76) | Y | N | Y | N |

| DGCR8 / Q8WYQ5 | 773 | 1 | 501-586 (67) | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 2 | 620-685 (66) | N | Y | N | Y | ||

| DHX9 / Q08211 | 1270 | 1 | 3-73 (71) | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 2 | 180-254 (75) | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||

| DHX30 / Q7L2E3 | 1222 | 1 | 80-153 (74) | N | N | N | N |

| 2 | 273-342 (70) | N | N | N | N | ||

| Dicer / Q9UPY3 | 1922 | 1 (DUF283) | 630-722 (80) | N | N | N | N |

| C-terminal | 1849-1918 (70) | Y | N | Y | N | ||

| Drosha / Q9NRR4 | 1374 | 1 | 1259-1334 (76) | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| DUS2/ Q9NX74 | 493 | 1 | 369-435 (67) | Y | Y | N | Y |

| ILF3 / Q12906 | 894 | 1 | 398-467 (70) | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 2 | 524-590 (67) | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||

| Kanadaptin / Q9BWU0 | 796 | 1 | 370-439 (70) | N | Y | N | Y |

| NkRF / O15226 | 690 | 1 | 349-411 (63) | Y | Y | N | N |

| 2 | 451-512 (62) | N | Y | N | N | ||

| PACT / O75569 | 313 | 1 | 34-101 (68) | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 2 | 126-194 (69) | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||

| 3 | 239-308 (70) | Y | Y | Y | N | ||

| PKR / P19525 | 551 | 1 | 8-81 (74) | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 2 | 99-171 (73) | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||

| SON / P18583 | 2140 | 1 | 2053-2120 (68) | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 2426 | 1 ΔC-terminus | 2371-2412 (42) | Y | N | Y | N | |

| STAU1 / Q6PJX3 | 577 | 2 | 69-164 (96) | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 3 | 180-260 (67) | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||

| 4 | 283-365 (67) | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||

| 5 | 488-554 (67) | N | N | N | N | ||

| STAU2 / Q9NUL3 | 570 | 1 | 3-87 (85) | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 2 | 91-184 (94) | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||

| 3 | 203-284 (67) | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||

| 4 | 303-381 (67) | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||

| 5 Δmiddle | 496-521 (26) | N | N | N | N | ||

| STRBP / Q96SI9 | 672 | 1 | 387-453 (67) | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 2 | 510-578 (69) | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||

| TARBP2 / Q15633 | 366 | 1 | 27-100 (74) | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 2 | 159-227 (69) | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||

| 3 | 294-361 (68) | Y | Y | Y | N | ||

| Protein / UniProtKB accession numbere |

Ribosome typef |

Amino acid number in representative isoformb |

dsRBDg or dsRBD-like fold nomenclature |

Amino acids in dsRBD or dsRBD- like fold (dsRBD or dsRBD-like fold size)c |

Gene3D (CATH) |

SMART | Prosite | Pfam |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C12orf65 / Q9H3J6 | mitochondrial | 166 | 1 | 53-125 (73) | Y | N | N | N |

| ICT1 / Q14197 | mitochondrial | 206 | 1 | 72-163 (92) | N | N | N | N |

| L44mt / Q9H9J2 | mitochondrial | 332 | 1 | 236-306 (71) | Y | N | Y | N |

| MRF-1 / O75570 | mitochondrial | 445 | 1g | 289-367 (79) | Y | N | N | N |

| RPS2/ P15880 | cytoplasmic | 293 | 1 | 98-167 (70) | Y | N | N | N |

| S5mt / P82675 | mitochondrial | 430 | 1 | 215-283 (69) | Y | N | N | N |

Full length protein names and identifiers (UniProtKB [http://www.uniprot.org/]) are as follows: A1CF, apolipoprotein B mRNA editing enzyme, catalytic polypeptide 1 (APOBEC1) complementation factor; ADAD, adenosine deaminase domain-containing protein; ADAR, adenosine deaminase that acts on RNA; CDKN2AIP, cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A-interacting protein; DGCR8, DiGeorge syndrome critical region 8; DHX9, DEAH box protein 9, also called ATPdependent RNA helicase A; DHX30, DEAH box protein 30, also called putative ATP-dependent RNA helicase DHX30; Dicer, endoribonuclease; Drosha, RNase III; DUS2, dihydrouridine synthase 2, also called tRNA-dihydrouridine(20) synthase nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate-like; ILF3, interleukin enhancer-binding factor 3; NκRF, nuclear factor kappa-light-chain enhancer of activated B cells-repressing factor; PACT, protein activator of the interferon-induced, dsRNA-activated protein kinase (PKR); PKR, also called protein kinase RNA-activated; kanadaptin; human lung cancer oncogene 3 protein; SON, Bax antagonist selected in saccharomyces 1; STAU, Staufen dsRNAbinding protein; STRBP, spermatid perinuclear RNA-binding protein; TARBP2, trans-activationresponsive RNA-binding protein.

Representative isoform harbors the largest number of complete dsRBDs.

dsRBD boundaries are derived from InterPro or manually edited based on available structural information.

Note that InterPro (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/) and the four programs that it uses – Genomic Threading Database (Gene3d; http://gene3d.biochem.ucl.ac.uk/Gene3D/) based on Class, Architecture, Topology and Homology (CATH) protein assignments; the Simple Modular Architecture Research Tool (SMART; http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/); Prosite (http://prosite.expasy.org/prosite.html); and the Protein families (Pfam; http://pfam.sanger.ac.uk/) – are constantly being updated. Thus, future results might differ from those we collected for this review. N, not found using default search parameters of InterPro; “Y”, found using default search parameters of InterPro.

Full length protein names and UniProtKB identifiers of dsRBD or dsRBD-like folds that majorly interact with ribosomes.

Type of ribosome that associates with this dsRBD or dsRBD-like fold. C12orf65, probable peptide chain release factor C12orf65, mitochondrial; ICT1, immature colon carcinoma transcript 1; L44mt, protein L44 of the mitochondrial 39S ribosomal subunit; MRF-1, mitochondrial peptide chain release factor 1; RPS2, protein S2 of the 40S ribosomal subunit; S5mt, protein S5 of the 28S mitochondrial ribosome small subunit.

Conforms more closely to a dsRBD fold than does dsRBD-like folds.

Divergent dsRBDs play a variety of roles in RNA metabolism that are often mediated by dsRBD–protein interactions and can involve the loss of dsRNA binding. The concept that RNA-binding folds can bind proteins has precedence in RNA-recognition motifs (RRMs) [2, 30]. Like true dsRBDs, divergent dsRBDs often co-exist in cis with one or more true dsRBDs (Table 1). A divergent dsRBD, even when it does not bind dsRNA itself, can cooperate with a true dsRBD to augment dsRNA recognition [31]. dsRBDs are found in prokaryotes [1], and they were present in the last common ancestor of metazoans [32]. Data indicate that more complex organisms harbor not only a greater number and diversity of dsRBDs but also more dsRBDs per protein. Although dsRBD-protein interactions have been discussed in the past [33-35], structural and functional data available today provide an improved perspective, which we present here.

Where the dsRBD fold can stray yet stay

Variations in α1

α1 is highly variable. The dsRBD-like fold of S5 prokaryotic ribosomal proteins either lacks α1 or harbors a very small α1 (Figures 1D and 1E; [36, 37]), whereas the dsRBD-like fold of class I peptide chain release factors (RFs), including bacterial RF1 and RF2, mitochondrial (mt) Mus musculus C12orf65 and immature colon carcinoma transcript 1 protein (ICT1), contain a 310 α1-helix [38-40]; Figure 1E; see [41] for 310 α1-helix description). Of dsRBD-like folds that lack α1, those of RNase H, HIV-1 integrase and MuA transposase form an integral component of a larger tertiary structure [11], whereas those of S5 form a modular extension [42]. Other β1-β2-β3-α2 dsRBD-like folds that we identified using DaliLite searches (http://ekhidna.biocenter.helsinki.fi/dali_server/start) as having structural similarity to human STAU1 dsRBD5 β1-β2-β3-α2 include bacterial Leptospira interrogans α-isopropylmalate synthase (PDB: 3F6H; [43]) and Mycobacterium tuberculosis Rv2632c-like DUF1876 (PDB: 2FGG; Turberculosis (TB) Structural Genomics Consortium).

When present, a full-length α1 can deviate in orientation. This is exemplified by the Domain of Unknown Function 283 (DUF283) of Dicer and Dicer-like proteins that is conserved across plant and animal species. Although DUF283 is deficient in RNA binding, extensive computational analyses indicate that it contains a dsRBD-like fold [44, 45]; Table 1). The NMR structure of apo-DUF283 from the Arabidopsis thaliana Dicer-like protein 4 reveals that it folds like a true dsRBD, except that L1 is extended to permit α1 to cross α2 at a right angle (Figure 1E; [46]) so that α1 cannot align along the channel formed by the dsRNA minor groove, as does α1 of a true dsRBD, without undergoing a conformational change. DUF283 dsRNA-binding deficiency is also likely to be inhibited by the lack of conserved residues in Region 1 of α1 and the conserved His in Region 2 of L2 [45]. As another example of α-deviation, hibernation promoting factor (HPF) and YfiA bacterial proteins have parallel rather than crossing α-helices in their dsRBD-like α1-β1-β2-β3-α2 folds; these are planted atop many highly structured 30S ribosomal RNAs to inhibit 70S ribosome translation elongation during stationary phase [46].

Variations in L2

Among dsRBDs classified as such, L1-3 have the most variability in length of any dsRBD element; however, in true (i.e. canonical) dsRBDs L1, L2, L3 and L4 are very consistent in length, being usually 4-6, 6, 1-2 and 1 amino acids, respectively [1, 4]. L4 has the potential to be even more variable in dsRBD-like folds, but an extended L4 might preclude identification of a dsRBD because existing programs are biased to discover the consensus L4-α2, which is highly conserved among known dsRBDs [15].

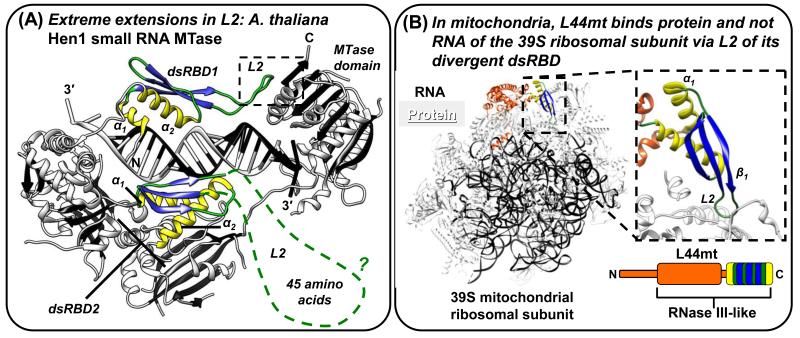

X-ray and NMR structures reveal that L2, when not bound to dsRNA, is generally the most flexible component of dsRBDs ([47-50]; see also PDBs 1O0W, Joint Center for Structural Genomics; 3P1X, [51]; 2L33, Northeast Structural Genomics Consortium; and 1X48, RIKEN Structural Genomics/Proteomics Initiative). The X-ray crystal structure of Arabidopsis thaliana Hen1 small RNA 3′-RNA ribose 2′-O-methyltransferase (MTase) reveals a remarkably long L2 in its two dsRBDs (Figure 2A; [52]). Hen1 forms a circle, thereby creating a pocket in which the dsRBDs bind a single microRNA (miRNA) via a Region 2 GPx motif (rather than the canonical GPxH motif) and a unique asparagine that interacts with the miRNA phosphate backbone [52]. The 18-amino acid dsRBD1 L2 is critical for circle formation by contributing hydrophobic residues that interact directly with the MTase domain, suggesting that this L2 has evolved to extend to the MTase domain for overall protein stabilization and length-specific interactions with miRNA. The even longer dsRBD2 L2 (45-amino acids) is disordered (Figure 2A), and a secondary structure prediction (Jpred3) suggests that dsRBD2 L2 might contain two α-helices that hamper identifying the α1-β1-β2-β3-α2 fold (Table 1). An NMR structure of the C-terminal dsRBD of Schizosaccharomyces pombe Dicer-1 also reveals an unusually long, 16-amino acid L2 harboring only the last residue of the canonical Region 2 GPxH motif in the context of an α1-β1-β2-β3-α2 fold [47]. L2, in combination with other unique features of this dsRBD (see below), contributes to dsRNA-binding and dsDNA-binding [47].

Figure 2. Alterations of L2 that add protein-protein interaction functions to dsRBDs and human STAU1 dsRBD5 as a model type-B dsRBD that has lost dsRNA-binding residues, but retains the dsRBD fold.

(A) X-ray crystal structure of A. thaliana Hen1 small RNA MTase (PDB 3HTX; [52]). The two dsRBDs maintain the color scheme of Figure 1, but the dashed green line of dsRBD2 represents missing L2 electron density, which is an indication of protein disorder. Other protein regions are white with black β-strands, and the dashed box indicates intra-molecular protein interactions between L2 and the MTase domain. (B) The 4.9 Å resolution cryo-electron microscopy structure of the mammalian (Sus scrofa domesticus; domestic pig) mitochondrial ribosome (PDB 4CE4; [53]) illustrating that the dsRBD domain of RNase III-like L44mt protein, which was modeled with a complete α1-β1-β2-β3-α2 fold, binds ribosomal protein and not RNA. The inset to the right shows the dsRBD-ribosomal protein interactions mediated through L2.

Even though H. sapiens STAU1 and STAU2 dsRBD2 have a predicted L2 of 30 amino acids (Jpred3) containing patches of hydrophobic residues that presumably preclude dsRNA binding [54], both dsRBDs are identified (Table 1) because discovery programs might be biased for L4-α2 conservation. D. melanogaster STAU dsRBD2 has a similar hydrophobic insertion, making its L2 ~100-amino acids (Jpred3) and thus able to contribute to microtubule-dependent mRNA localization [55]. When excess residues are removed from D. melanogaster STAU dsRBD2 L2, it is then capable of binding dsRNA [55]. dsRBD2 contributes to H. sapiens STAU1 multimerization via interactions that can be recapitulated using full-length protein [56], possibly via undefined L2-mediated intramolecular or intermolecular interactions. As another example of L2 divergence, two STAU1 isoforms in rat brain differ only by the presence or absence of 6 amino acids in β1 of dsRBD3, and the presence of these 6 amino acids reduce dsRNA binding [57]. The structure of D. melanogaster STAU dsRBD3 [58] together with secondary structure predictions (Jpred3) of rat STAU1 dsRBD3 suggest that the 6 amino acids inhibit RNA binding by re-positioning the L2 Region 2 GPxH motif.

A recent 4.9 Å electron microscopy structure of RNase-like L44mt from Sus scrofa domesticus (pig) in association with the 39S ribosomal subunit demonstrates that the complete and canonically sized α1-β1-β2-β3-α2 fold of L44mt (Table 1) lacks residues of Regions 2 and 3 that are important for dsRNA binding (Figure 2B) but contains a Region 2 L2 that inserts between proteins on the external surface of the ribosomal subunit [53]. In this instance, variations in L2 sequence rather than length add a protein-binding function to this dsRBD. Interestingly, human STAU1, which harbors degenerate dsRBDs 2 and 5, interacts with the 60S subunit of cytoplasmic ribosomes independently of dsRBDs 3 and 4 binding dsRNA [59-61]. It would be interesting to learn if STAU1 also uses its degenerate dsRBDs to facilitate protein-mediated interactions with ribosomes and with their divergent surfaces that constitute Regions 1-3 in true dsRBDs.

dsRBD-like folds of S5 and RF/C12orf65 family members bind RNA (ribosomal RNA of prokaryotic or human mitochondria) differently than do true dsRBDs, perhaps because of deviations in not only α1 (see above) but also L2. Although the structure of the S5 protein alone shows a bent L2 [37], X-ray data obtained for several prokaryotic ribosomes reveal that S5 L2 adopts a short β-hairpin structure while contacting RNA [36, 62]. The 15- or 16-amino acid L2 of, respectively, prokaryotic RF1 or RF2 penetrates the ribosome so that its apical GGQ motif, which is part of a short α-helix, becomes ordered upon ribosome binding, interacts directly with a translation termination codon in the ribosomal A-site, and hydrolyzes nascent peptide release [38, 40, 42]. RF1 and RF2 manifest other variations, including an α2 that is almost twice the length of a true dsRBD α2 [40, 42].

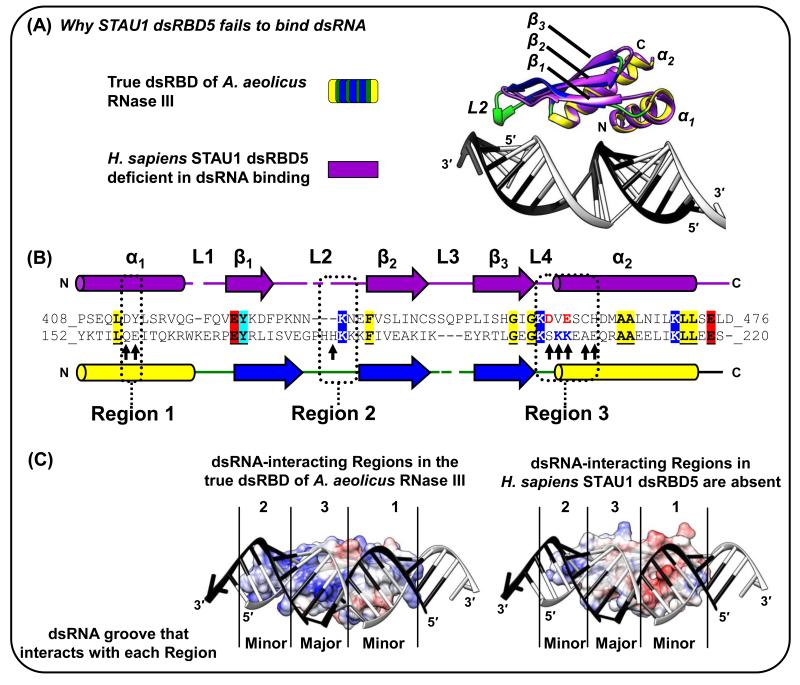

Variations in dsRNA-interacting Regions 1-3

Conserved dsRBD residues can be separated into those that contribute to the α1-β1-β2-β3-α2 tertiary fold and those fold extensions, namely Regions 1-3, that directly contact dsRNA [1]. Despite escaping identification as a true dsRBD (Table 1), a recent X-ray crystal structure (Figure 3A) reveals that the type-B dsRBD5 of human STAU1, which is important for human STAU1 dimerization if not multimerization [17, 56], assumes a true dsRBD fold but fails to bind RNA for several reasons: Region 1 lacks an important glutamate, Region 2 is abnormally short and lacks the GPxH motif, and Region 3 lacks the KKxAK motif, which is essentially replaced by negatively charged residues that would repel dsRNA (Figures 3B and 3C) [17, 54]. The highly similar dsRBD5 in D. melanogaster Staufen is likewise deficient in dsRNA binding [55] but contributes to oskar mRNA localization in the developing oocyte via direct interactions with the protein Miranda [61], further exemplifying type-B dsRBD interactions with proteins rather than dsRNAs.

Figure 3. The STAU1 dsRBD5 type-B dsRBD can fold nearly identically to true dsRBDs but lacks all three dsRNA-interacting Regions [17].

(A) Superposition of the X-ray crystal structure of human STAU1 dsRBD5 with that of the true dsRBD of A. aeolicus RNase III (Figure 1A-D; [3, 17]). The mainchain (i.e. Cα backbone) of STAU1 dsRBD5 has root mean square deviations as low as 1.8 Å relative to true dsRBDs. (B) Structural-based alignment of dsRBDs in (A). Identical residues are shaded and underlined if they reside outside the dsRNA-interacting regions, which suggests conserved contributions to the fold rather than to dsRNA-binding directly. Arrows within Regions 1-3 are those in the A. aeolicus RNase III dsRBD 3 that match the consensus dsRBD. Notice especially the STAU1 dsRBD5 negatively charged D and E residues positioned in Region 3 near where dsRNA-interacting residues KK exist in true dsRBDs. (C) Electrostatic potential surfaces, generated using the Chimera program, of (left) A. aeolicus RNase III dsRBD (Figure 1A-D; [3]), or (right) STAU1 dsRBD5 [17] superimposed onto the A. aeolicus RNase III dsRBD. Blue, red or white signify, respectively, positively, negatively or neutral charged surfaces. dsRNA in the A. aeolicus RNase III dsRBD structure is shown for both dsRBDs to illustrate for STAU1 dsRBD5 the lack of charged residues in Region 3 and the shortened Region 2, which partially explain its inability to bind dsRNA.

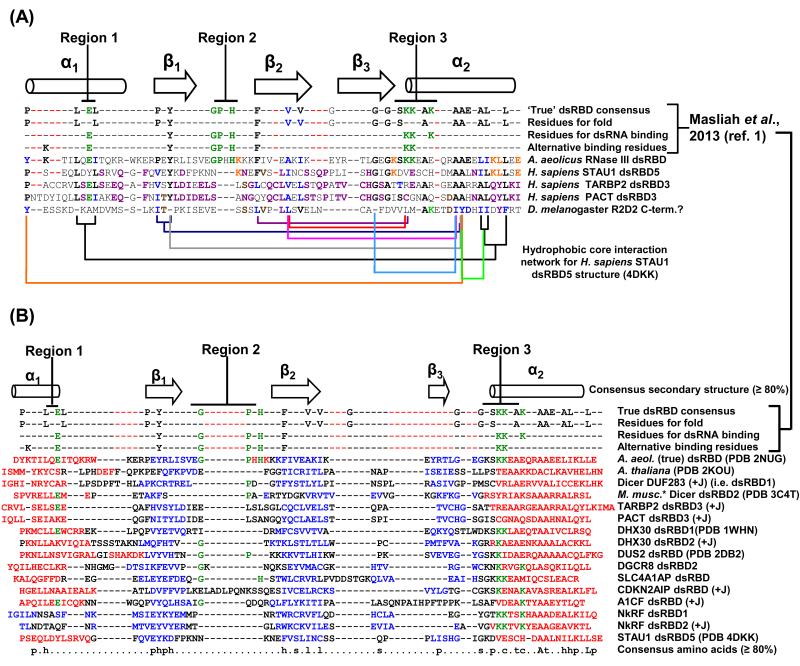

In fact, type-B dsRBDs generally fail to bind dsRNA, but are instead important for protein-protein interactions. Human TARBP2 and PACT, which are characterized by a common modular structure, each have a dsRBD3 that is not found by one of the discovery programs (Table 1; [50, 63]), indicating their divergence. The C-terminal region that encompasses TARBP2 dsRBD3 has been named “Medipal” because it binds Merlin, Dicer and PACT as a liaison [63]. Moreover, both PACT and TARBP2 hetero- and homo-dimerize through their true (i.e. dsRNA-binding) dsRBD1- and 2-containing regions, and they additionally use these dsRBD regions to bind, respectively, dsRBD1 and dsRBD2 of PKR [63] demonstrating that protein binding is not exclusive to black sheep dsRBDs and typifies some true dsRBDs. There are no structures for TARBP2 or PACT dsRBD3s. However, alignments of TARBP2 dsRBD3 with STAU1 dsRBD5, which share 31% identity over 91% of their sequence, indicate that both TARBP2 and PACT dsRBD3 lack dsRNA-interacting Regions 2 and 3 but contain the conserved core-folding residues (Figure 4A) and, thus, would be expected to assume a dsRBD fold that fails to bind dsRNA.

Figure 4. Black sheep and true dsRBDs share conservation in residue properties to generate the dsRBD fold.

(A) Conserved core dsRBD-folding residues in black sheep dsRBD3s of TARBP2 and PACT. Structurally guided sequence alignment of TARBP2 and PACT dsRBD3s (PROMALS3D; http://prodata.swmed.edu/promals3d/promals3d.php) generated using structures of a true dsRBD (A. aeolicus RNase III dsRBD; [3]) and the black sheep STAU1 dsRBD5 [17]. Hydrophobic interactions observed in the X-ray crystal structure of STAU1 dsRBD5 are indicated by connecting brackets. Residues of similar hydrophobicity and size are conserved in TARBP2 and PACT. As an exercise, a sequence in D. melanogaster R2D2 that harbors a predicted but small (60-amino acid) α1-β1-β2-β3-α2 secondary structure and has escaped identity as a dsRBD appears to share some of the conserved folding residues of dsRBDs. Green, residues that are consensus dsRBD-interacting; black, residues conserved in true dsRBD folds [1]; blue, residues hydrophobically conserved in all sequences shown; orange, residues conserved only between STAU1 dsRBD5 and A. aeolicus RNase III dsRBD; purple, residues conserved in all three black sheep dsRBDs; brown, residues conserved between the putative dsRBD in R2D2 and the three black sheep dsRBDs. Dashed red lines accommodate extra sequences in type-B dsRBDs relative to the true dsRBD consensus. (B) PROMALS3D-generated structure-based (when known) and/or sequence-based sequence alignment of all known or putative human black sheep dsRBDs (Table 1) with the A. aeolicus RNase III dsRBD (Figure 1A-D; [3]). Known human black sheep dsRBD structures are denoted using their PDB identifier. PROMALS3D output was manually modified to incorporate structure-derived secondary structure information and Jpred3 (+J) secondary structure information, the latter when it was more representative of a dsRBD fold than information obtained using PsiPred and PROMALS3D. Additionally, slight changes to the alignment were made by hand in L2 to align, when present, residues that match the GPxH motif of true dsRBDs [1]. Red or blue, known or predicted residues within, respectively, an α-helix or β-strand; green, residues known to directly interact with dsRNA in one of the three dsRNA-binding Regions. *The C-terminal dsRBD sequence in the X-ray crystal structure of Mus musculus Dicer is identical to the C-terminal dsRBD sequence in human Dicer. Full protein names are provided in Table 1. p, polar; h, hydrophobic; s, small; l, aliphatic; c, charged; t, tiny (i.e. small sidechain); “A”, conserved alanine; “L”, conserved leucine; dashed red lines as in (A).

PKR is a central hub of interactions for dsRBD-containing proteins that regulate its function as an innate response to infection by dsRNA viruses. Provided that PKR can dimerize on dsRNA and, as a consequence, autophosphorylate to become activated, PKR phosphorylates eIF2α, which in turn inhibits global cellular translation and, in particular, the synthesis of viral proteins [64]. PACT, TARBP2, ADAR1, dihydrouridine synthase 2 (DUS2), spermatid perinuclear RNA-binding protein (SPNR) and interleukin enhancer-binding factor 3 (ILF3) are dsRBD-containing proteins that interact with PKR [65-69]. Besides dsRNA, PKR can be activated by PACT [70]. TARBP2, ADAR1 and DUS2 repress PKR activation [65-69]. The ability of TARBP2 and PACT to form a heterodimer might interfere with the ability of each to control PKR [67]. DUS2, which catalyzes the conversion of uridine to dihydro-uridine on the D-loop of tRNA, contains a single dsRBD residing C-terminal to its enzymatic domain only in animals [71]. This dsRBD binds dsRNA [72] but is not recognized by Prosite, most likely due to the complete or partial absence of Regions 1, 2 and 3 (Table 1 and Figure 3B). The DUS2 dsRBD also binds both PKR and PACT [72]. While the interaction of DUS with PACT is less understood, the DUS2 dsRBD binds PKR dsRBD1 so as to represses PKR activation [72]. Repression might be enhanced by the sequestration of DUS2 by PACT, which has been proposed to alleviate the interaction of PACT with PKR [72]. High-resolution data describing the protein–protein interactions that regulate PKR activity should in the future provide major insights into the overlapping functions of these dsRBDs.

Although the primary sequence of all but L4-α2 of STAU1 dsRBD5 and other type-B dsRBDs is not well-conserved relative to true dsRBDs, structural studies illustrate that STAU1 dsRBD5 and other known and putative black sheep dsRBDs (Figure 4B) maintain residues in key positions to fulfill the two criteria required to fold like a true dsRBD: forming the five secondary structure elements, and forming the dsRBD core that dictates the correct three-dimensional topology via correctly positioned hydrophobic side-chains of the appropriate length. That noted, an α1 leucine and β1 tyrosine are conserved in true and type-B dsRBDs. Mapping the hydrophobic interaction network of the STAU1 dsRBD5 core gives insight into the basic requirements for type-B and putative dsRBD folds (Figure 4A). For example, STAU1 dsRBD5 harbors a valine in the first position of Region 3 that, unlike the amphipathic lysine of true dsRBDs, contributes to folding but not dsRNA binding (Figure 4A) [1, 7].

As made clear by the STAU1 dsRBD5 structure, L4-α2 provides the central hub for interactions that extend throughout the core, especially through the almost invariant alanine-alanine (AA) that typifies α2 of true and type-B dsRBDs [15]. The short side chains of the AA residues appear to be critical for the β-sheet to pack closely on top of them. Likewise, the importance of the conserved second glycine that resides at the β3-L4 transition appears to allow α2 to closely pack on top of it (Figure 4A; the second glycine is alanine in TARBP2 dsRBD3, which exemplifies a black sheep). Possibly, the AA residues could be longer if their complementary hydrophobic binding partners within the core were shorter, which should be considered when developing new dsRBD fold discovery algorithms.

Taken together the dsRBD fold can persist even with variability in the lengths of α1, L2 and/or other loops, and with the presence or absence of dsRNA-interacting Regions. What can be defined as dsRBD-like is subjective as illustrated by, for example, dsRBD-like folds that have lost α1 and also contain insertions. It remains to be determined if some α1-β1-β2-β3-α2 folds have been preserved for the sake of folding or the sake of function, the latter of which could be to bind proteins either in addition to or instead of binding dsRNA.

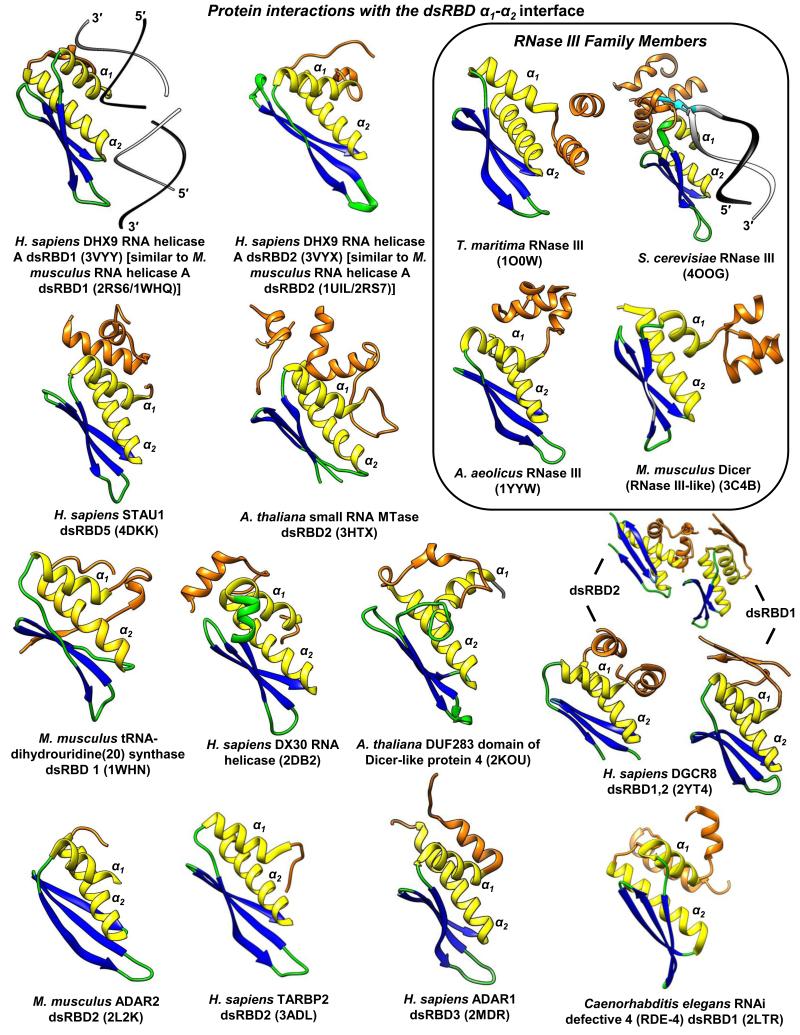

Protein binding to the α1-α2 surface

X. laevis Xlrbpa dsRBD3 and, by inference, its human ortholog PACT dsRBD3, are type-B dsRBDs thought to homodimerize through dsRBD3-dsRBD3 interactions; however, the addition of a five residue appendage C-terminal to Xlrbpa dsRBD3 that we do not expect to be within the dsRBD fold enhances dsRBD3 interactions with full-length protein ~5-fold [73]. As of yet, there is no structure that has elucidated how dsRBDs without appendages can homodimerize. Additionally, there has yet to be a clear structure representing an exclusively trans dsRBD-protein interaction. Yet, an abundance of dsRBD-appendage structures have revealed that appendages as short as three amino acids N- and/or C-terminal to the dsRBD fold often interact with the dsRBD α1-α2 interface in cis (Figure 5). Appendage interactions with dsRBDs in cis can be important for achieving full-length protein architecture. For example, the α-helical face of A. thaliana Hen1 MTase A dsRBD2 interacts in cis with two N-terminal α-helices that are separated from dsRBD2 by a rigid 22-amino acid linker (Figures 2A and 5) [52].

Figure 5. Known structural examples of intra-molecular (cis) dsRBD-protein interactions via the dsRBD α1-α2 surface.

All structures are positioned in the same relative orientation for comparisons. Orange, dsRBD appendages that interact with the α1-α2 interface. Species, protein, dsRBD, and PDB identifier are listed. Structurally redundant homologs are specified. As a frame of reference, H. sapiens DHX9 RNA helicase A dsRBD1 is shown bound to dsRNA [74] to illustrate the consensus dsRBD interface interaction with dsRNA. S. cerevisiae Rnt1p RNase III is also shown bound to dsRNA to illustrate the important dsRBD “G-loop” appendage, which specifically recognizes the stem-loop apex guanosine (cyan) [14]. PDB ID followed by corresponding reference or group for solving the structure if there is no described associated manuscript described in the PDB are as follows: 3VYY and 3VYX, [74]; 4DKK, [17]; 3HTX, [52]; 1WHN and 2DB2, RIKEN Structural Genomics/Proteomics Initiative; 2KOU, [45]; 2YT4, [48]; 2L2K, [6]; 3ADL, [75]; 2MDR, [76]; 2LTR, [77]; 1O0W, Joint Center for Structural Genomics; 4OOG, [14]; 1YYW, [78]; and 3C4B, [79].

New studies suggest that some dsRBD appendages can additionally mediate important trans interactions with dsRBDs in other proteins. For example, the black-sheep human STAU1 dsRBD5 uses its α1-α2 interface to interact in cis and in trans with the appended “STAU-swapping motif” (SSM) (Figure 5) [17]. The SSM resides N-terminal to dsRBD5 to which it is connected via a flexible 16-amino acid linker. STAU1 dimerization, that is, a trans interaction, augments the efficiency of Staufen-mediated mRNA decay [17, 80]. Notably, all isoforms of the STAU1 and its paralog STAU2 contain an SSM and α1 of dsRBD5, and only these regions are required for STAU1–STAU1, STAU1–STAU2 and, probably, STAU2–STAU2 dimerization [17, 81]. Similarly, DGCR8 uses an appendage C-terminal to its black sheep dsRBD2 to simultaneously bind in cis the α1-α2 interfaces of dsRBD1 and dsRBD2 (Table 1 and Figure 5) [48], and it is tempting to speculate that these interactions function in DGCR8 multimerization [82].

A recent crystal structure of S. cerevisiae Rnt1p RNase III that includes the homodimerized N-terminal domain illustrates how a dsRBD has diverged in multiple ways to bind not only dsRNA but also protein [14]. It was known that the unusual hydrophobic residues of α1 and L1 with the α-helix that resides C-terminal to the dsRBD form an extended core [8, 13]. The new structure revealed a second α-helix that resides C-terminal to the known α-helix, and demonstrated that the two α-helices form a “G-loop” that recognizes a specific guanosine in the apex of the hairpin RNAs to which it binds (Figure 5; [14]). Moreover, the interface formed by α1, α2 and first C-terminal α-helix with the dimerized N-terminal domain properly orients the Rnt1p dimer–hairpin RNA complex so that the stem of the hairpin is cleaved asymmetrically [14] (Figure 5).

While some dsRBDs bind dsRNA and protein simultaneously, the ADAR1 dsRBD3 binds either RNA or protein, the latter to facilitate its nuclear import. While a number of nuclear localization sequences (NLSs) within proteins derive from contiguous amino acids, ADAR1 dsRBD3 acts as a scaffold that juxtaposes its N- and C-terminal appendages to form a bipartite NLS. In this way, cytoplasmic ADAR1 cannot be imported into the nucleus when bound to dsRNA but is accessible to transportin 1 when free of dsRNA [76]. Other examples of function appendages include sequences C-terminal to Staufen1 dsRBD3, which forms an NLS [83], and sequences N-terminal to the incomplete dsRBD1 (lacking α1-L2) the 59-kD isoform of Staufen 2, which forms a nuclear export signal recognized by exportin 1 [84].

Structural data indicate that dsRBDs predominantly use their α-helical face rather than their β-sheet face for protein interactions. This is unlike RRMs, which in addition to their α-helical face sometimes use the hydrophobic ssRNA-base-recognizing residues of their β-sheet face to interact with protein-binding partners [2, 30]. Some type A dsRBDs appear capable of simultaneously binding protein and dsRNA [63, 82] and for at least cis interactions, protein binding to the α-α2 interface does not always preclude the dsRNA-binding interface (Figure 5). Our current understanding of protein interactions with any type of dsRBD is very limited and will hopefully be improved by additional high-resolution structure determinations.

Removing the wool: high-resolution studies of other protein-binding dsRBD folds are needed

Many degenerate dsRBD-mediated protein interactions are important to the mechanism of RNA interference. In humans, TARBP2 contains three dsRBDs, the C-terminal-most of which is a divergent dsRBD (Table 1). dsRBD3 within C4 of the TARBP2 Medipal domain, which fails to bind dsRNA, interacts with the N-terminal helicase domain of Dicer as a flexible part of the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) that contains Argonaute 2 (AGO2), Dicer and TARPB2 [85-88]. TARBP2 is proposed to rearrange its position during RISC processing to facilitate handing-off diced small interfering RNA (siRNA) to AGO2. In D. melanogaster, the TARBP2 ortholog Loqs, like human TARBP2 and PACT, binds Dicer-1 with its C-terminal dsRBD3 to process pre-miRNAs to miRNAs [89-91]. Notably, 46 amino acids that reside N-terminal to dsRBD3 of the Loqs-PB isoform are missing from the Loqs-PA isoform, explaining why Loqs-PB but not Loqs-PA functions in a complex with Dicer-1 [91]. This exemplifies the importance of determining whether the ability of a dsRBD fold to bind proteins requires N- and/or C-terminal appendages. ADAR1, which contains exclusively true dsRBDs capable of binding dsRNA (Table 1), uses dsRBD2 in a dsRNA-independent manner to interact with both the N-terminal helicase domain and the DUF283 degenerate dsRBD fold of Dicer to accelerate Dicer-mediated generation and RISC-loading of miRNA [92]. Given that the N-terminal helicase domain of Dicer is also known to interact with TARBP2, PACT, and ADAR1, possibly these interactions occur by Dicer recognition of elements common to other dsRBD folds regardless of their dsRNA-binding properties. For example, one might hypothesize that the N-terminal helicase region of Dicer could bind in cis to its own divergent DUF283 or C-terminal RNase III-like dsRBD.

The repertoire of DUF283-mediated interactions extends across Dicer homologs as exemplified by A. thaliana Dicer-like protein 4 (DCL4) DUF283, which preferentially heterodimerizes with dsRBD1 of dsRNA-binding protein 4 (DRB4), and by A. thaliana DCL1 DUF283, which preferentially heterodimerizes with the dsRBD2 of the DRB4 paralog hyponastic leave 1 (HYL1) [45, 93]. Accordingly, the Pfam database refers to DUF283 as a “Dicer dimerization domain”. Data indicate that DRB4 dsRBD2 binds not only dsRNA using its conserved Regions 1-3 [94] but also the E3 ubiquitin ligase anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome core subunit [95], whereas HYL1 dsRBD2 fails to bind dsRNA [93].

In addition to DUF283, the second and C-terminal dsRBD of S. pombe Dicer-1 is also divergent, and it regulates processes through unknown protein interactions [96]. Together with a C-terminal appendage that contributes two cysteines, an L1 cysteine and L3 histidine of this dsRBD form a CHCC zinc coordination motif [47]. This motif acts as a thermoswitch, where temperatures above 34-38 °C result in a loss of zinc coordination and therefore Dicer-1 denaturation. Under non-stress conditions, Dicer-1 co-localizes with Atf1 transcription factor bound to stress genes at nuclear pores to co-transcriptionally degrade stress-gene transcripts. Stress-induced denaturation of Dicer-1 causes a loss of transcript degradation and therefore up-regulation of Atf1-inducible proteins that mediate a stress response [47, 96]. Although S. pombe Dicer-1 binds dsRNA and dsDNA, its nuclear localization functions are independent of dsRNA binding [47]. Notably, like the C-terminal dsRBD of S. pombe Dicer-1, DUF283 of A. thaliana DCL4 coordinates zinc, but using three cysteines [45]. Human Dicer DUF283 harbors only one of the three cysteines and likely fails to bind zinc.

There are undoubtedly many cellular functions yet to be discovered for divergent dsRBD interactions with proteins. For example, a dsRBD1-containing fragment of A. thaliana FRY2 interacts presumably through KH domains 3 and 4 of HOS5 to facilitate pre-mRNA splicing [97], a field of research more often associated with RRM rather than dsRBD functions. Future high-resolution dsRBD–protein 3D structures will reveal their functional utility in such important cellular mechanisms.

Concluding remarks: finding the fold

To further expand the repertoire of black sheep dsRBDs that are increasingly proving important to cellular function, future dsRBD-fold recognition software must avoid bias by evolving away from algorithms built upon true dsRBDs. New divergent dsRBD structures will allow us to tease apart how component and flanking amino acids contribute to the dsRBD fold and dsRNA and/or protein binding.

It is challenging to identify new degenerate dsRBD folds. Past tendencies to identify dsRBDs by their ability to bind dsRNA [15] are not amenable to finding black sheep that do not bind dsRNA. First, new software would ideally identify the fold even when all nine of the conserved dsRNA-binding residues are not present (Figure 4). For example, STAU1 dsRBD5, which is not found by any of the four discovery programs (Table 1), lacks 7 of the 9 conserved dsRNA-binding residues [1]. Second, new software would ideally find an α1-β1-β2-β3-α2 fold that harbors large insertions that might include additional secondary structure elements. Although dsRBD loops can apparently tolerate large variations while conserving the central rigid body of the α1-β1-β2-β3-α2 fold, variations that result in misalignment of conserved residues and secondary structure elements might hamper discovery programs from finding the fold, as is the case for the dsRBDs of A. thaliana Hen1. Third, structural determinations using NMR and/or X-ray crystallography will be required to verify putative degenerate dsRBD folds identified by discovery programs.

The need for improved dsRBD-fold recognition software is exemplified by a comparison of human DHX30 and DHX9, both of which are members of the DEAH/ATP-dependent RNA helicase A family [98] and predicted to share a similar overall architecture. Both co-immunoprecipitate with the AGO1 and AGO2 RISC components; however, co-immunoprecipitation of DHX30 is RNase-sensitive whereas co-immunoprecipitation of DHX9 is not [99]. Neither of the two DHX30 dsRBDs is identified using InterPro, whereas InterPro finds both DHX9 dsRBDs (Table 1). Proof that DHX30 dsRBD1 assumes a dsRBD fold derives from its NMR structure (PDB 2DB2: RIKEN structural genomics project), which demonstrates that it lacks most dsRNA-nteracting residues in Regions 1-3 (Figure 4B) and harbors a two-turn α-helix insertion in L1 (Figure 5). We discovered DHX30 dsRBD2 by searching the poorest of dsRBD profile hits in Prosite followed by secondary structure predictions (JPred3), suggesting that other dsRBD-like folds are also hidden within known protein sequences. For example, the C-terminal region of D. melanogaster R2D2, which interacts with the helicase domain of Dicer-2 [90] analogously to how D. melanogaster Loqs interacts with the helicase domain of Dicer-1 [100], contains a predicted (MeDor) ~60-amino acid α1-β1-β2-β3-α2 topology. No one to our knowledge has interpreted this predicted secondary structure as a dsRBD, and it is not identified as such using low-fidelity Prosite parameters that were able to define STAU1 dsRBD5 (Table 1). While we are not certain that the C-terminal region of D. melanogaster R2D2 assumes a dsRBD fold, this exercise illustrates that future discovery programs will have to step outside of current search biases, which utilize only a narrow definition of what constitutes a dsRBD fold, before the repertoire of cellular dsRBD folds can be significantly expanded.

Thinking “outside of the dsRBD” will add an advantage to future structural determinations of degenerate and true dsRBDs. Prediction software such as XtalPred (http://ffas.burnham.org/XtalPred-cgi/xtal.pl) informs crystallographers to avoid flexible regions outside of dsRBDs. The STAU1 SSM-loop-dsRBD5 structure, which was solved despite a “difficult” XtalPred score [17], indicates that structural and functional studies would do well to consider intramolecular and/or intermolecular dsRBD-protein interactions that could stabilize complexes for crystallization. An increased number of dsRBD structures in the context of full-length proteins with or without dsRNA and/or protein-binding partners are required to more completely understand the remarkable breadth of dsRBD function.

Elements

Box 1. α1-β1-β2-β3-α2 folds that are not dsRBDs, and protein domains that bind dsRNA without an α1-β1-β2-β3-α2 fold.

Not all proteins with α1-β1-β2-β3-α2 dsRBD-like tertiary topology bind dsRNA. According to the Structural Classification of Proteins database (http://scop.mrc-lmb.cam.ac.uk/scop/), the human DNA recombination protein RAD52 has dsRBD-like fold containing β1-β2-β3-α2 secondary structure elements that are approximately two-times longer than in canonical dsRBDs and harbors hydrophobic residues in place of polar residues that bind dsRNA in true dsRBDs [18, 19]. The α1-β1-β2-β3-α2 fold of 11 RAD52 molecules form the inside wall of a ring, and extensions from each fold form the outer surface that together bind ssDNA and dsDNA [18-20]. In notable contrast, the human RAD52 ortholog, Sak, of the Lactococcus lactis phage ul36 is predicted to contain dsRBD-sized secondary structure elements [21] (Jpred3; http://www.compbio.dundee.ac.uk/www-jpred/).

Offering another twist to the dsRBD fold are proteins that contain α1-β1-β2-β3-α2 secondary topology but lack the appropriate tertiary topology to be classified as a dsRBD; we call these domains dsRBD-like. Examples include the α1-β1-β2-β3-α2 folds within signal recognition particle (SRP) components SRP9 and SRP14 that form their heterodimerization surface and also associate with 7S RNA [22, 23]. The resulting trimeric complex competes with eukaryotic elongation factor 2 for binding to dsRNA-containing regions in the 80S ribosome. Complex binding stalls translation elongation, permitting other SRP constituents to bind the N-terminal signal sequence of the nascent peptide and a membrane-bound SRP receptor for subsequent co-translational translocation of the peptide into the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum [24, 25]. Relative to canonical dsRBDs, the positions of α1 and α2 within SRP9 and SRP14 are switched [26], which is one of many reasons why SRP9 and SRP14 contact dsRNA differently than do canonical dsRBDs. The X-ray crystal structure of SRP9–SRP14 in complex with the 5′Alu domain of 7SL RNA indicates that SRP9 and SRP14 have a Region 3 KKxAK-like motif (KKIEK in SRP9; KEVNK in SRP14) residing proximal to the N-terminus of α2 that contacts or is close to 7SL RNA [23].

Proteins that lack α1-β1-β2-β3-α2 dsRBD folds also can recognize dsRNA. Examples include i) the melanoma differentiation-associated protein 5 (MDA5), which has multiple modular domains that wrap around a 12-bp dsRNA and form oligomeric filaments through head-to-tail interactions when bound to dsRNAs >100 bps [27]; ii) the D2 RecA-like domain of the Mss116p DEAD-box helicase, the structure of which has been resolved bound to a 14-bp dsRNA [28]; and iii) stem-loop-binding protein, which binds the 3′-untranslated region hairpin of cell cycle-regulated histone mRNAs [29].

Highlights.

dsRBD α1-β1-β2-β3-α2 folds can form despite large sequence variations

These variations might or might not support dsRNA binding

Loop 2 insertions and the α-helical dsRBD face can provide protein-binding sites

Identifying additional dsRBD folds might be obscured by large sequence variations

Acknowledgments

Funding for this work was provided by a US National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant NIH R01 GM074593 to L. Maquat and an NIH NCI T32 grant CA09363 to H. Land that supported M. Gleghorn. M. Guy and J. Liberman contributed helpful comments. We apologize to authors whose work we did not cite due to reference number limitations.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Masliah G, et al. RNA recognition by double-stranded RNA binding domains: a matter of shape and sequence. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013;70:1875–1895. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-1119-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maris C, et al. The RNA recognition motif, a plastic RNA-binding platform to regulate post-transcriptional gene expression. FEBS J. 2005;272:2118–2131. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gan J, et al. A stepwise model for double-stranded RNA processing by ribonuclease III. Mol Microbiol. 2008;67:143–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.06032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tian B, et al. The double-stranded-RNA-binding motif: interference and much more. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:1013–1023. doi: 10.1038/nrm1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barraud P, Allain FH. ADAR proteins: double-stranded RNA and Z-DNA binding domains. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2012;353:35–60. doi: 10.1007/82_2011_145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stefl R, et al. The solution structure of the ADAR2 dsRBM-RNA complex reveals a sequence-specific readout of the minor groove. Cell. 2010;143:225–237. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramos A, et al. RNA recognition by a Staufen double-stranded RNA-binding domain. EMBO J. 2000;19:997–1009. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.5.997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Z, et al. Structure of a yeast RNase III dsRBD complex with a noncanonical RNA substrate provides new insights into binding specificity of dsRBDs. Structure. 2011;19:999–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu H, et al. Structural basis for recognition of the AGNN tetraloop RNA fold by the double-stranded RNA-binding domain of Rnt1p RNase III. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:8307–8312. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402627101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zheng X, Bevilacqua PC. Straightening of bulged RNA by the double-stranded RNA-binding domain from the protein kinase PKR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:14162–14167. doi: 10.1073/pnas.011355798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koh HR, et al. ATP-independent diffusion of double-stranded RNA binding proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:151–156. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1212917110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ryter JM, Schultz SC. Molecular basis of double-stranded RNA-protein interactions: structure of a dsRNA-binding domain complexed with dsRNA. EMBO J. 1998;17:7505–7513. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.24.7505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hartman E, et al. Intrinsic dynamics of an extended hydrophobic core in the S. cerevisiae RNase III dsRBD contributes to recognition of specific RNA binding sites. J Mol Biol. 2013;425:546–562. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.11.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liang YH, et al. Structure of a Eukaryotic RNase III Postcleavage Complex Reveals a Double-Ruler Mechanism for Substrate Selection. Mol Cell. 2014;54:431–444. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.St Johnston D, et al. A conserved double-stranded RNA-binding domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:10979–10983. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.10979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krovat BC, Jantsch MF. Comparative mutational analysis of the double-stranded RNA binding domains of Xenopus laevis RNA-binding protein A. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:28112–28119. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.45.28112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gleghorn ML, et al. Staufen1 dimerizes through a conserved motif and a degenerate dsRNA-binding domain to promote mRNA decay. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20:515–524. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kagawa W, et al. Crystal structure of the homologous-pairing domain from the human Rad52 recombinase in the undecameric form. Mol Cell. 2002;10:359–371. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00587-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singleton MR, et al. Structure of the single-strand annealing domain of human RAD52 protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:13492–13497. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212449899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kagawa W, et al. Identification of a second DNA binding site in the human Rad52 protein. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:24264–24273. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802204200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ploquin M, et al. Functional and structural basis for a bacteriophage homolog of human RAD52. Curr Biol. 2008;18:1142–1146. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.06.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Birse DE, et al. The crystal structure of the signal recognition particle Alu RNA binding heterodimer, SRP9/14. EMBO J. 1997;16:3757–3766. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.13.3757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weichenrieder O, et al. Structure and assembly of the Alu domain of the mammalian signal recognition particle. Nature. 2000;408:167–173. doi: 10.1038/35041507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ataide SF, et al. The crystal structure of the signal recognition particle in complex with its receptor. Science. 2011;331:881–886. doi: 10.1126/science.1196473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Halic M, et al. Structure of the signal recognition particle interacting with the elongation-arrested ribosome. Nature. 2004;427:808–814. doi: 10.1038/nature02342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wild K, et al. Towards the structure of the mammalian signal recognition particle. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2002;12:72–81. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(02)00292-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu B, et al. Structural basis for dsRNA recognition, filament formation, and antiviral signal activation by MDA5. Cell. 2013;152:276–289. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.11.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mallam AL, et al. Structural basis for RNA-duplex recognition and unwinding by the DEAD-box helicase Mss116p. Nature. 2012;490:121–125. doi: 10.1038/nature11402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tan D, et al. Structure of histone mRNA stem-loop, human stem-loop binding protein, and 3′hExo ternary complex. Science. 2013;339:318–321. doi: 10.1126/science.1228705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Safaee N, et al. Interdomain allostery promotes assembly of the poly(A) mRNA complex with PABP and eIF4G. Mol Cell. 2012;48:375–386. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brooks R, et al. The double-stranded RNA-binding domains of Xenopus laevis ADAR1 exhibit different RNA-binding behaviors. FEBS Lett. 1998;434:121–126. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00963-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kerner P, et al. Evolution of RNA-binding proteins in animals: insights from genome-wide analysis in the sponge Amphimedon queenslandica. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:2289–2303. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chang KY, Ramos A. The double-stranded RNA-binding motif, a versatile macromolecular docking platform. FEBS J. 2005;272:2109–2117. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Doyle M, Jantsch MF. New and old roles of the double-stranded RNA-binding domain. J Struct Biol. 2002;140:147–153. doi: 10.1016/s1047-8477(02)00544-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fierro-Monti I, Mathews MB. Proteins binding to duplexed RNA: one motif, multiple functions. Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25:241–246. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01580-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Demirci H, et al. The central role of protein S12 in organizing the structure of the decoding site of the ribosome. RNA. 2013;19:1791–1801. doi: 10.1261/rna.040030.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ramakrishnan V, White SW. The structure of ribosomal protein S5 reveals sites of interaction with 16S rRNA. Nature. 1992;358:768–771. doi: 10.1038/358768a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kogure H, et al. Solution structure and siRNA-mediated knockdown analysis of the mitochondrial disease-related protein C12orf65. Proteins. 2012;80:2629–2642. doi: 10.1002/prot.24152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shin DH, et al. Structural analyses of peptide release factor 1 from Thermotoga maritima reveal domain flexibility required for its interaction with the ribosome. J Mol Biol. 2004;341:227–239. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weixlbaumer A, et al. Insights into translational termination from the structure of RF2 bound to the ribosome. Science. 2008;322:953–956. doi: 10.1126/science.1164840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rohl CA, Doig AJ. Models for the 3(10)-helix/coil, pi-helix/coil, and alpha-helix/3(10)-helix/coil transitions in isolated peptides. Protein Sci. 1996;5:1687–1696. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560050822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Laurberg M, et al. Structural basis for translation termination on the 70S ribosome. Nature. 2008;454:852–857. doi: 10.1038/nature07115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang P, et al. Molecular basis of the inhibitor selectivity and insights into the feedback inhibition mechanism of citramalate synthase from Leptospira interrogans. Biochem J. 2009;421:133–143. doi: 10.1042/BJ20090336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dlakic M. DUF283 domain of Dicer proteins has a double-stranded RNA-binding fold. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:2711–2714. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Qin H, et al. Structure of the Arabidopsis thaliana DCL4 DUF283 domain reveals a noncanonical double-stranded RNA-binding fold for protein-protein interaction. RNA. 2010;16:474–481. doi: 10.1261/rna.1965310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Polikanov YS, et al. How hibernation factors RMF, HPF, and YfiA turn off protein synthesis. Science. 2012;336:915–918. doi: 10.1126/science.1218538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barraud P, et al. An extended dsRBD with a novel zinc-binding motif mediates nuclear retention of fission yeast Dicer. EMBO J. 2011;30:4223–4235. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sohn SY, et al. Crystal structure of human DGCR8 core. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:847–853. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weinberg DE, et al. The inside-out mechanism of Dicers from budding yeasts. Cell. 2011;146:262–276. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yamashita S, et al. Structures of the first and second double-stranded RNA-binding domains of human TAR RNA-binding protein. Protein Sci. 2011;20:118–130. doi: 10.1002/pro.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kuglstatter A, et al. Insights into the conformational flexibility of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase from multiple ligand complex structures. Protein Sci. 2011;20:428–436. doi: 10.1002/pro.575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Huang Y, et al. Structural insights into mechanisms of the small RNA methyltransferase HEN1. Nature. 2009;461:823–827. doi: 10.1038/nature08433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Greber BJ, et al. Architecture of the large subunit of the mammalian mitochondrial ribosome. Nature. 2013 doi: 10.1038/nature12890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wickham L, et al. Mammalian staufen is a double-stranded-RNA- and tubulin-binding protein which localizes to the rough endoplasmic reticulum. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:2220–2230. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.3.2220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Micklem DR, et al. Distinct roles of two conserved Staufen domains in oskar mRNA localization and translation. EMBO J. 2000;19:1366–1377. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.6.1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Martel C, et al. Multimerization of Staufen1 in live cells. RNA. 2010;16:585–597. doi: 10.1261/rna.1664210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Monshausen M, et al. Two rat brain staufen isoforms differentially bind RNA. J Neurochem. 2001;76:155–165. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bycroft M, et al. NMR solution structure of a dsRNA binding domain from Drosophila staufen protein reveals homology to the N-terminal domain of ribosomal protein S5. EMBO J. 1995;14:3563–3571. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07362.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dugre-Brisson S, et al. Interaction of Staufen1 with the 5′ end of mRNA facilitates translation of these RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:4797–4812. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Luo M, et al. Molecular mapping of the determinants involved in human Staufen-ribosome association. Biochem J. 2002;365:817–824. doi: 10.1042/bj20020263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ricci EP, et al. Staufen1 senses overall transcript secondary structure to regulate translation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2014;21:26–35. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Roy-Chaudhuri B, et al. Ribosomal protein S5, ribosome biogenesis and translational fidelity. In: Rodnina M, et al., editors. Ribosomes. Springer Vienna; 2011. pp. 263–270. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Laraki G, et al. Interactions between the double-stranded RNA-binding proteins TRBP and PACT define the Medipal domain that mediates protein-protein interactions. RNA Biol. 2008;5:92–103. doi: 10.4161/rna.5.2.6069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dauber B, Wolff T. Activation of the Antiviral Kinase PKR and Viral Countermeasures. Viruses. 2009;1:523–544. doi: 10.3390/v1030523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Clerzius G, et al. ADAR1 interacts with PKR during human immunodeficiency virus infection of lymphocytes and contributes to viral replication. J Virol. 2009;83:10119–10128. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02457-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Coolidge CJ, Patton JG. A new double-stranded RNA-binding protein that interacts with PKR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:1407–1417. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.6.1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Daher A, et al. TRBP control of PACT-induced phosphorylation of protein kinase R is reversed by stress. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:254–265. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01030-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nie Y, et al. Double-stranded RNA deaminase ADAR1 increases host susceptibility to virus infection. J Virol. 2007;81:917–923. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01527-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wen X, et al. NF90 exerts antiviral activity through regulation of PKR phosphorylation and stress granules in infected cells. J Immunol. 2014;192:3753–3764. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Li S, et al. Molecular basis for PKR activation by PACT or dsRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:10005–10010. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602317103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kasprzak JM, et al. Molecular evolution of dihydrouridine synthases. BMC Bioinformatics. 2012;13:153. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-13-153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mittelstadt M, et al. Interaction of human tRNA-dihydrouridine synthase-2 with interferon-induced protein kinase PKR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:998–1008. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hitti EG, et al. Oligomerization activity of a double-stranded RNA-binding domain. FEBS Lett. 2004;574:25–30. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.07.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fu Q, Yuan YA. Structural insights into RISC assembly facilitated by dsRNA-binding domains of human RNA helicase A (DHX9) Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:3457–3470. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yang SW, et al. Structure of Arabidopsis HYPONASTIC LEAVES1 and its molecular implications for miRNA processing. Structure. 2010;18:594–605. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Barraud P, et al. A bimodular nuclear localization signal assembled via an extended double-stranded RNA-binding domain acts as an RNA-sensing signal for transportin 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:E1852–1861. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1323698111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chiliveri SC, Deshmukh MV. Structure of RDE-4 dsRBDs and mutational studies provide insights into dsRNA recognition in the Caenorhabditis elegans RNAi pathway. Biochem J. 2014;458:119–130. doi: 10.1042/BJ20131347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gan J, et al. Intermediate states of ribonuclease III in complex with double-stranded RNA. Structure. 2005;13:1435–1442. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Du Z, et al. Structural and biochemical insights into the dicing mechanism of mouse Dicer: a conserved lysine is critical for dsRNA cleavage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:2391–2396. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711506105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Park E, Maquat LE. Staufen-mediated mRNA decay. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2013;4:423–435. doi: 10.1002/wrna.1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Park E, et al. Staufen2 functions in Staufen1-mediated mRNA decay by binding to itself and its paralog and promoting UPF1 helicase but not ATPase activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:405–412. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1213508110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Faller M, et al. DGCR8 recognizes primary transcripts of microRNAs through highly cooperative binding and formation of higher-order structures. RNA. 2010;16:1570–1583. doi: 10.1261/rna.2111310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Martel C, et al. Staufen1 is imported into the nucleolus via a bipartite nuclear localization signal and several modulatory determinants. Biochem J. 2006;393:245–254. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Miki T, Yoneda Y. Alternative splicing of Staufen2 creates the nuclear export signal for CRM1 (Exportin 1) J Biol Chem. 2004;279:47473–47479. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407883200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chakravarthy S, et al. Substrate-specific kinetics of Dicer-catalyzed RNA processing. J Mol Biol. 2010;404:392–402. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Daniels SM, Gatignol A. The multiple functions of TRBP, at the hub of cell responses to viruses, stress, and cancer. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2012;76:652–666. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00012-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Parker GS, et al. dsRNA binding properties of RDE-4 and TRBP reflect their distinct roles in RNAi. J Mol Biol. 2008;384:967–979. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wang HW, et al. Structural insights into RNA processing by the human RISC-loading complex. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:1148–1153. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lee Y, et al. The role of PACT in the RNA silencing pathway. EMBO J. 2006;25:522–532. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Leuschner PJ, et al. MicroRNAs: Loquacious speaks out. Curr Biol. 2005;15:R603–605. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ye X, et al. Functional anatomy of the Drosophila microRNA-generating enzyme. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:28373–28378. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705208200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ota H, et al. ADAR1 forms a complex with Dicer to promote microRNA processing and RNA-induced gene silencing. Cell. 2013;153:575–589. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hiraguri A, et al. Specific interactions between Dicer-like proteins and HYL1/DRB-family dsRNA-binding proteins in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol Biol. 2005;57:173–188. doi: 10.1007/s11103-004-6853-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Fukudome A, et al. Specific requirement of DRB4, a dsRNA-binding protein, for the in vitro dsRNA-cleaving activity of Arabidopsis Dicer-like 4. RNA. 2011;17:750–760. doi: 10.1261/rna.2455411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Marrocco K, et al. APC/C-mediated degradation of dsRNA-binding protein 4 (DRB4) involved in RNA silencing. PLoS One. 2012;7:e35173. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Woolcock KJ, et al. RNAi keeps Atf1-bound stress response genes in check at nuclear pores. Genes Dev. 2012;26:683–692. doi: 10.1101/gad.186866.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Chen T, et al. A KH-Domain RNA-Binding Protein Interacts with FIERY2/CTD Phosphatase-Like 1 and Splicing Factors and Is Important for Pre-mRNA Splicing in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003875. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Fairman-Williams ME, et al. SF1 and SF2 helicases: family matters. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2010;20:313–324. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2010.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hock J, et al. Proteomic and functional analysis of Argonaute-containing mRNA-protein complexes in human cells. EMBO Rep. 2007;8:1052–1060. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7401088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lim do H, et al. Functional analysis of dicer-2 missense mutations in the siRNA pathway of Drosophila. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;371:525–530. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.04.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]