Abstract

Exposure-based therapies are considered the state-of-the-art treatment for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Yet, a substantial number of PTSD patients do not recover after therapy. In the light of the well-known gene × environment interactions on the risk for PTSD, research on individual genetic factors that influence treatment success is warranted. The gene encoding FK506-binding protein 51 (FKBP5), a co-chaperone of the glucocorticoid receptor (GR), has been associated with stress reactivity and PTSD risk. As FKBP5 single-nucleotide polymorphism rs1360780 has a putative functional role in the regulation of FKBP5 expression and GR sensitivity, we hypothesized that this polymorphism influences PTSD treatment success. We investigated the effects of FKBP5 rs1360780 genotype on Narrative Exposure Therapy (NET) outcome, an exposure-based short-term therapy, in a sample of 43 survivors of the rebel war in Northern Uganda. PTSD symptom severity was assessed before and 4 and 10 months after treatment completion. At the 4-month follow-up, there were no genotype-dependent differences in therapy outcome. However, the FKBP5 genotype significantly moderated the long-term effectiveness of exposure-based psychotherapy. At the 10-month follow-up, carriers of the rs1360780 risk (T) allele were at increased risk of symptom relapse, whereas non-carriers showed continuous symptom reduction. This effect was reflected in a weaker treatment effect size (Cohen's D=1.23) in risk allele carriers compared with non-carriers (Cohen's D=3.72). Genetic factors involved in stress response regulation seem to not only influence PTSD risk but also responsiveness to psychotherapy and could hence represent valuable targets for accompanying medication.

Introduction

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is the most common mental health condition in the aftermath of traumatic stress. PTSD prevalence rates depend on cumulative trauma exposure1 and converge around 8% in the United States,2,3 whereas the disorder occurrence is much higher in post-conflict settings.4

Without treatment, PTSD may take a chronic course,1 associated with severe impairments in daily functioning, higher risk of physical illness5,6 and suicidality.7 However, even when treated with exposure-based psychotherapy, considered to be the most effective treatment for PTSD,8,9 a substantial proportion of survivors does not recover.10 Therefore, the identification of individual factors that influence PTSD treatment success is of utmost scientific and clinical importance.

The formation of strong fear memories of traumatic experiences11 and a failure to extinguish the associated reactions to trauma reminders12 are thought to be the key processes of PTSD development. Hence, exposure-based treatments aim at the modification of fear memories through extinction learning.13 The heritability of PTSD susceptibility after trauma is ~30–40%,14,15 and studies investigating gene × environment interactions have identified several memory-related genetic factors that moderate the influence of cumulative trauma exposure on PTSD risk.16 Hence, the response to exposure-based PTSD treatments might be also moderated by particular genetic variants that are implicated in memory processes. To date, two studies identified genetic variations of the serotonin transporter gene17 as well as the brain-derived neurotrophic factor18 as genetic modulators of PTSD treatment outcome.

Hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal axis regulation has been implicated in the etiology of stress-related disorders such as PTSD.19 The release of glucocorticoids facilitates the mobilization of resources for a fight or a flight response. Concurrently, binding of cortisol to the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) is critical to terminate the stress reaction via negative feedback.20 Hence, the functioning of the GR is necessary for an adequate stress response regulation. Several chaperones and co-chaperones, including FK506-binding protein 51 (FKBP5), modulate GR sensitivity. Binding of FKBP5 to the GR reduces its cortisol-binding capacity and prevents nuclear translocation,21,22 which leads to impaired negative feedback regulation of the hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal axis and a prolonged stress response. Interestingly, FKBP5 gene expression can be triggered by cortisol via intronic glucocorticoid response elements.23 Binding of cortisol to GRs leads to a rapid increase in FKBP5 expression, which in turn reduces GR sensitivity—an ultrashort negative feedback loop of GR sensitivity.24 Therefore, traumatic stress and subsequent increased cortisol release could lead to enhanced FKBP5 gene expression and reduced GR sensitivity.25 As glucocorticoid signaling can influence the risk of PTSD26,27 and is known to have an important role in fear memory formation and extinction,28,29 genetic variability of FKBP5 may influence PTSD vulnerability as well as responsiveness to trauma-focused treatments.

The FKBP5 gene, located on the short arm of chromosome 6, harbors several common polymorphisms in high linkage disequilibrium, found to be associated with different psychological disorders.25 Single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) rs1360780 is located closest to a functional glucocorticoid response element and has a putative functional role in the regulation of FKBP5 expression and GR sensitivity.30 In healthy individuals, the risk (T) allele was associated with higher FKBP5 expression31 and relatively reduced GR sensitivity32 as well as impaired recovery of cortisol levels in response to stress33,34 (but see also Mahon et al.35). Furthermore, the T allele predicted enhanced risk for depression, albeit with inconsistent findings,31,36, 37, 38 elevated probability of anxiety disorder development39 and higher suicide risk.40 Most important in this context, FKBP5 genotype was also found to be associated with peritraumatic dissociation, a strong risk factor for subsequent PTSD development,41 as well as with PTSD risk.32 The latter study investigated four FKBP5 polymorphisms, including rs1360780, and found the highest PTSD probability in individuals with the risk genotype who had experienced physical and sexual child abuse. Xie et al.42 confirmed the FKBP5 genotype × environment interaction effect only for one of the four SNPs investigated (rs9470080) in an African American sample. An extension study of the original study of Binder and colleagues30 replicated the interaction effect of rs1360780 and childhood trauma on current PTSD. Interestingly, rs1360780 risk allele carrier status was associated with a differential chromatin conformation, which promotes higher FKBP5 gene expression in response to early stress. Furthermore, risk allele carriers who experienced childhood trauma showed elevated DNA demethylation near and at functional glucocorticoid response elements of the FKBP5 gene, further enhancing FKBP5 gene expression in response to GR activation.30 Yet, in contrast to healthy subjects, FKBP5 risk genotype carriers with PTSD show lower FKBP5 gene expression43 and enhanced GR sensitivity compared with non-carriers,32,44 a finding that is in accordance with cumulative evidence of GR hypersensitivity in PTSD.26

Summing up, rs1360780, a putative functional SNP of the FKBP5 gene,30 has been shown to effect—in a PTSD disease status-dependent manner—FKBP5 gene expression and GR sensitivity. This is the first study to investigate whether FKBP5 rs1360780 genotype modulates treatment outcome of Narrative Exposure Therapy (NET), an exposure-based short-term trauma-therapeutic treatment approach especially developed for the context of mass conflict and organized violence.45 The efficacy of NET for the treatment of PTSD symptoms has been previously shown in multiple settings,46 including the post-war context of Northern Uganda.47 We hypothesized that carriers of rs1360780 risk (T) allele would benefit less from treatment with NET.

Materials and methods

Subjects

Participants were survivors of the rebel war led by the Lord's Resistance Army in Northern Uganda, who had experienced numerous atrocities, including abductions and forced recruitment into the rebel forces, mutilations, forced participation in combats, killings and sexual violence. The recruitment for the present study took place in the former Internal Displaced People camps Anaka, Pabbo and Koch Goma. Inclusion criteria were (1) a diagnosis of PTSD according to DSM-IV, (2) age between 18 and 65, (3) absence of any signs of alcohol or substance dependence, (4) absence of psychotic symptoms, (5) no psychotropic medication and (6) no prior trauma-focused psychotherapy. Fifty-three subjects were enrolled in the study and received treatment with NET by trained local counselors under the supervision of clinical experts in the field of trauma therapy. Chip-based genotyping was impossible for four individuals because of low DNA concentrations, and one further participant was excluded after genotyping quality control. In addition, three participants were excluded from the present study because of discontinuation of therapy (N=1, rs1360780 genotype=C/T), unavailability for both follow-up interviews (N=1, genotype=C/C) and an extraordinary strength of flashbacks, which required that a clinical expert resumed the treatment (N=1, genotype=C/C). In the latter case, the therapy was completed successfully; however, comparability to the other treatments conducted by trained local counselors was no longer given. Individuals who we could only trace for one follow-up assessment (only 4 months, N=1, genotype=C/C; only 10 months, N=1, genotype=T/T) were still included in the analyses. Finally, chip-based genotyping of FKBP5 rs1360780 failed for two participants. Hence, results are reported on a final sample of N=43 (29 females, mean age=31.91, s.d.=9.49, rs1360780 genotype C/C=13, C/T=15, T/T=15).

Procedure

Clinical interviews were conducted before treatment (t1) and 4 and 10 months (t2 and t3, respectively) after treatment completion. Current PTSD diagnosis and symptom severity were assessed in a structured interview based on the Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale (PDS).48 A 62-item event list, adapted for the context of the Lord's Resistance Army war, cf.49 was employed to assess the number of experienced traumatic event types (traumatic load). We assessed suicidal risk utilizing the respective section of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.).50 Local interviewers who attended 6 weeks of training on the concepts of clinical interviews, quantitative data collection and PTSD conducted the interviews. The instruments were translated into the local language (Luo) followed by blind back-translations, group discussions and corrections by independent translators. Retest reliability and validity (consistency with expert ratings) of the psychological assessment by trained local interviewers were previously investigated and revealed good psychometric quality.51 Participants provided saliva samples in the first diagnostic interview using Oragene Self Collection Kits (DNA Genothek, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada). SNP-based genotyping was performed according to the Genome-Wide Human SNP Nsp/Sty 6.0 User Guide (Affymetrix Inc, Santa Clara, CA, USA). SNP rs1360780 is represented on the array (SNP ID: SNP_A-8589266). Genetic quality control was performed in PLINK v1.07.52

Treatment

The study participants received an average of 12 sessions of NET. Sessions took place twice a week and generally lasted between 90 and 120 min. In brief, the aim of NET is to reconstruct the survivor's life story with a particular focus on traumatic stressors. The first session comprises psychoeducation and serves to obtain a biographical overview of the client's life. The subsequent sessions involve exposure therapy to the most severe traumatic experiences in chronological order and the last session comprises the re-reading of the narrated life story.45 Intensively trained local counselors performed the therapies under the supervision of expert psychologists. Treatment adhesion was monitored in case discussions, weekly supervision meetings as well as via reviews of detailed case documentations.

After a detailed explanation of the study protocol participants gave written informed consent. All procedures followed the Declaration of Helsinki and were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Gulu University, Uganda, the Ugandan National Council for Science and Technology and the ethics committee of the German Psychological Society (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychologie).

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed in the statistical environment R 3.0.2.53 Demographic and clinical data of the genotype groups were compared using Fisher's exact test for count data and one-factorial analyses of variance (ANOVA) for continuous data. If ANOVA residuals were non-normally distributed, a non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis H test was employed.

The effect of FKBP5 rs1360780 genotype on treatment outcome was evaluated by fitting linear mixed effect models (R package nlme 3.1-111).54 PDS score was defined as the outcome variable, genotype as a between-subject fixed factor, time as a within-subject repeated fixed factor and participants as a random effect, with random intercepts for each participant. The correlations of the repeated measurements within participants were modeled with a general correlation structure,55,56 and the maximum likelihood estimation method was employed to fit the model.

In the model selection procedure, we fitted nested models of increasing complexity and compared their goodness-of-fit. The initial analysis was performed including only time and FKBP5 rs1360780 genotype as predictors. Next, we analyzed whether a genotype model, comparing the three rs1360780 genotype groups (C/C, C/T and T/T), or a risk allele carrier model, combining C/T and T/T genotypes in one group, represented the data best. As traumatic load is known to strongly influence PTSD symptomatology,1 and FKBP5 gene × environment interactions have been observed previously,30,32 further analyses were performed with and without traumatic load as a covariate, and with and without allowing for potential time × FKBP5 genotype × traumatic load interaction effects. In addition, it was evaluated whether the inclusion of the covariates sex and age would improve model fit. As recommended by Burnham and Anderson,57 model selection was based on Akaike's Information Criterion, which has a profound information-theoretic foundation and aims at minimizing the expected Kullback–Leibler divergence between the model and the true underlying data-generating process.

We expected T allele carriers to benefit less from NET treatment, which would result in a significant time × FKBP5 rs1360780 interaction. More specifically, we hypothesized that the difference between the pretreatment PDS score (time point t1) and the follow-up PDS scores (time points t2 or t3) would be higher in individuals with the protective genotype (C/C) than in carriers of the T (risk) allele. We tested this specific hypothesis by evaluating the statistical significance of planned contrasts while adjusting for multiple comparisons (R package multcomp 1.3-1).58

Results

FKBP5 rs1360780 genotype groups showed no differences in age, gender distribution, traumatic load, number of NET sessions, PTSD symptom severity, PTSD symptom scores and suicidality before treatment (Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic and clinical information by FKBP5 rs1360780 genotype group.

| C/C (N=13) | C/T (N=15) | T/T (N=15) | Statistica | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N female (%) | 9 (69) | 9 (60) | 11 (73) | Fisher's exact test | 0.78 |

| Mean age (s.d.) | 35.38 (10.40) | 30.60 (13.06) | 30.20 (10.52) | H2=3.58 | 0.17 |

| Mean traumatic load (s.d.) | 35.92 (5.54) | 38.07 (7.06) | 35.93 (7.25) | F2,40=0.50 | 0.61 |

| Mean number of sessions (s.d.) | 11.46 (2.18) | 11.67 (2.50) | 12 (1.46) | H2=2.03 | 0.36 |

| Mean PDS score (t1) (s.d.) | 17.69 (4.44) | 16.47 (4.76) | 16.8 (5.27) | H2=0.70 | 0.70 |

| Mean PDS intrusions score (t1) (s.d.) | 4.85 (2.51) | 3.87 (2.45) | 5.20 (2.01) | F2,40=1.32 | 0.28 |

| Mean PDS avoidance score (t1) (s.d.) | 6.38 (2.10) | 6.67 (1.88) | 5.47 (2.07) | H2=3.68 | 0.16 |

| Mean PDS hyperarousal score (t1) (s.d.) | 6.46 (2.15) | 5.93 (1.91) | 6.13 (3.48) | H2=0.77 | 0.68 |

| Mean M.I.N.I. suicidality score (t1) (s.d.) | 12.69 (8.31) | 12.13 (10.21) | 11.67 (12.49) | H2=0.40 | 0.82 |

Abbreviations: ANOVA, analysis of variance; M.I.N.I., Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; PDS, Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale.

ANOVA F-test for continuous data if test residuals were normally distributed, Kruskal–Wallis H-test for continuous data if residuals were not normally distributed and Fisher's exact test for categorical data.

Confirming our main hypothesis, we found a significant time × FKBP5 rs1360780 genotype interaction effect. This effect was present in every estimated linear mixed effect model. Our successive model selection procedure strongly suggested that a risk allele carrier model, including traumatic load and sex as covariates, represented the data best (Table 2). We therefore report statistical inference from this model.

Table 2. Estimated models and model selection procedure.

| Estimated model (fixed effects) | AIC |

|---|---|

| Model 1: Time × FKBP5 rs1360780 Genotypea | 789.52 |

| Model 2: Time × FKBP5 rs1360780 T allele carrierb | 783.82 |

| Model 3: Time × FKBP5 rs1360780 T allele carrier + traumatic load | 771.18 |

| Model 4: Time × FKBP5 rs1360780 T allele carrier × traumatic load | 773.54 |

| Model 5: Time × FKBP5 rs1360780 T allele carrier + traumatic load + sexc | 767.38 |

| Model 6: Time × FKBP5 rs1360780 T allele carrier + traumatic load + sex + age | 769.23 |

Abbreviations: AIC, Akaike's Information Criterion; FKB5, FK506-binding protein 51.

The genotype model contrasts the three genotype groups (C/C, C/T and T/T).

The T allele carrier model compares carriers of the T risk allele (C/T and T/T genotypes) with non-carriers (C/C genotype).

Model 5 (marked in bold letters) was chosen based on the model selection criteria as it yielded the smallest AIC.

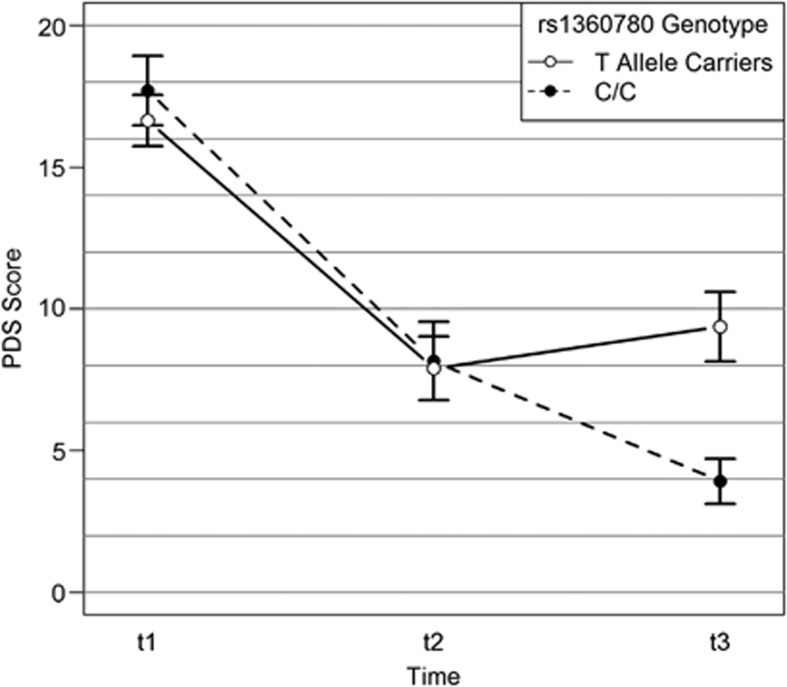

The selected model revealed a significant treatment effect (main effect time, F2,80=96.84, P<0.001), no significant main FKBP5 rs1360780 genotype effect, but a significant time × FKBP5 rs1360780 genotype interaction effect (F2,80=5.40, P=0.006, Figure 1). Furthermore, the two included covariates, traumatic load (F1,39=18.42, P<0.001) and sex (F1,39=6.08, P=0.018) significantly predicted PTSD symptom severity.

Figure 1.

Carriers of the FKBP5 rs1360780 T allele display less symptom improvements following trauma-focused therapy. Depicted are the mean values and s.e.'s of measurement. PDS, Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale; t1, before treatment; t2, 4-month follow-up; t3, 10-month follow-up.

To further examine the nature of the time × FKBP5 rs1360780 genotype interaction effect, we next calculated three planned orthogonal contrasts while adjusting P-values for multiple testing. There was no genotype-dependent difference in treatment success rates 4 months after treatment (comparison t1–t2). Yet, 10 months after the end of the treatment (comparison t1–t3), non-carriers of the risk allele had significantly higher symptom improvements than risk allele carriers (Z=3.37, P<0.001, Figure 1). Furthermore, there was a significant difference in the symptom development between the two follow-up assessments (difference t2–t3); whereas risk allele carriers had a greater risk for symptom relapse, non-carriers continued to show symptom improvements (Z=2.71, P=0.009, Figure 1).

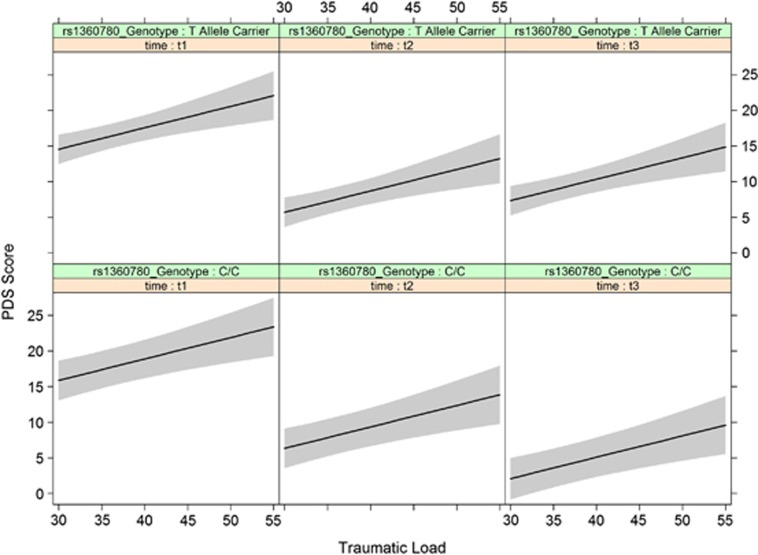

To obtain a better understanding of the substantial main effect of traumatic load, we plotted the fitted values of the PDS score against traumatic load separately for the three time points and genotype groups (Figure 2). We observed a dose-dependent relationship between traumatic load and PDS score at all time points, yet T allele carriers showed a higher intercept 10 months post treatment.

Figure 2.

Fitted values and confidence intervals of the PDS Score separately for the two genotype groups and three time points in dependence of traumatic load. Traumatic load predicted Posttraumatic Stress Disorder symptom severity at all time points, but at 10 months following therapy T allele carriers have higher symptoms compared with non-carriers. PDS, Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale; t1, before treatment; t2, 4-month follow-up; t3, 10-month follow-up.

We next analyzed the clinical significance of the genotype effect on therapy outcome by investigating the mean change scores between the 10-month follow-up and the pretreatment assessment, as well as the treatment effect sizes for each genotype group. Both genotype groups presented with large treatment effects according to the conventions of Cohen; however, for individuals with the protective (C/C) genotype the treatment effect size was approximately three times higher than for carries of the risk allele (Table 3). Furthermore, 10 months after treatment, no individual in the C/C genotype group fulfilled the diagnosis of PTSD, whereas 43% of T allele carriers still met the diagnostic criteria according to DSM-IV (Table 3).

Table 3. Treatment-associated changes in clinical variables by genotype groups.

| t1(pretreatment) | t2(4 months) | t3 (10 months) | Change scorea | Effect size Cohen's Db | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N PTSD diagnosis (%) | |||||

| C/C | 13 (100) | 4 (31) | 0 (0)c | ||

| T allele carrier | 30 (100) | 7d (29) | 13 (43) | ||

| Mean PDS score (s.d.) | |||||

| C/C | 17.69 (4.44) | 8.15 (5.00) | 3.92 (2.78) | −13.58 (6.37) | 3.72 |

| T allele carrier | 16.63 (4.94) | 7.90 (6.03) | 9.37 (6.73) | −7.27 (5.60) | 1.23 |

| Mean M.I.N.I. suicidality score (s.d.) | |||||

| C/C | 12.69 (8.31) | 5.31 (6.47) | 2.08 (4.94) | −11.08 (8.67) | 1.55 |

| T allele carrier | 11.90 (11.21) | 8.45 (10.60) | 7.37 (8.31) | −4.53 (6.85) | 0.45 |

| Mean PDS intrusions score (s.d.) | |||||

| C/C | 4.85 (2.51) | 2.54 (1.51) | 1.50 (1.68) | −3.08 (3.32) | 1.57 |

| T allele carrier | 4.53 (2.30) | 1.83 (2.25) | 2.53 (2.36) | −2.00 (3.25) | 0.86 |

| Mean PDS avoidance score (s.d.) | |||||

| C/C | 6.38 (2.10) | 2.46 (1.94) | 0.83 (1.27) | −5.50 (2.54) | 3.20 |

| T allele carrier | 6.07 (2.03) | 2.52 (2.23) | 3.17 (2.36) | −2.90 (2.29) | 1.32 |

| Mean PDS hyperarousal score (s.d.) | |||||

| C/C | 6.46 (2.15) | 3.15 (2.41) | 1.58 (1.00) | −5.00 (2.45) | 2.92 |

| T allele carrier | 6.03 (2.76) | 3.55 (2.68) | 3.67 (2.68) | −2.37 (2.51) | 0.87 |

Abbreviations: M.I.N.I., Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; PDS, Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale; PTSD, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder.

Change score describes the difference between pretreatment and 10-month follow-up assessment.

Cohen's D describes the within-group treatment effect size between pretreatment and 10-month follow-up assessment.

One individual was not found for 10-month follow-up.

One individual was not found for 4-month follow-up.

Finally, we exploratively investigated whether genotype differences in treatment success would be also reflected in the three PTSD symptom clusters and suicidality risk. T Allele carriers scored higher on all variables 10 months after treatment (Table 3,Supplementary Figures S1 and 2). These effects resulted in a significant rs1360780 × time interaction for avoidance (F2,80=5.74, P=0.005) and hyperarousal symptoms (F2,80=4.65, P=0.012), but not for intrusion symptoms (F2,80=2.10, P=0.130). The interaction was marginally significant for the outcome suicidality (F2,80=3.06, P=0.053).

Discussion

Confirming our hypothesis, we found a significant effect of FKBP5 rs1360780 genotype on therapeutic outcome of NET. This effect was present at 10 months, but not 4 months after treatment completion, indicating that the FKBP5 genotype predominantly influences long-term therapeutic outcome. Psychotherapy—in contrast to pharmacological treatment—initializes a process of recovery that continues over time. Confirming this, evidence from Northern Uganda shows that NET treatment effects increase over time (that is, treatment effects assessed 1 year after therapy completion were more pronounced than 6 months post treatment).47 Hence, genetic variants that are linked to psychotherapeutic outcome should show stronger effects on the long-term course of symptoms rather than on immediate psychotherapeutic outcomes. This is in line with the findings of Bryant et al.,17 reporting a moderating influence of genetic variation at the serotonin transporter locus on trauma therapy outcome at the follow-up assessment, but not immediately post treatment.

The empirical data favored a risk allele carrier model: carriers of one or two copies of the T allele showed enhanced risk for symptom relapse 10 months after treatment, whereas individuals with the protective C/C genotype showed continuous symptom improvement. The genotype effect had significant clinical implications: individuals with the protective genotype had three times higher treatment effect sizes than risk allele carriers. Whereas 43% of risk allele carriers fulfilled the diagnostic criteria of PTSD, the entire C/C genotype group showed clinical remission 10 months post treatment. In addition, the strong effect of the FKBP5 genotype on treatment success was descriptively reflected in all PTSD symptom clusters as well as in suicidality, with significant effects on the avoidance and hyperarousal symptom cluster. Hence, trauma-related symptoms of distress and arousal seem to be more resistant to modification through trauma-focused therapy in carriers of the rs1360780 T allele.

How might FKBP5 rs1360780 genotype influence psychotherapy success? Extensive evidence indicates that the stress hormone cortisol facilitates memory formation, impairs retrieval and enhances memory extinction processes.28 Both the formation of traumatic memories and their modification through psychotherapy rely on learning and memory processes: whereas fear conditioning is thought to be responsible for the onset of PTSD, extinction learning is the basis of exposure therapy.16 Indeed, stress and associated elevated cortisol levels increase extinction memory consolidation,59 and the administration of glucocorticoids enhances the effects of exposure therapy for anxiety disorders.60, 61, 62 Accordingly, FKBP5 genotype might influence the initial fear memory strength as well as the process of extinction learning.

The FKBP5 rs1360780 T allele is characterized by a different three-dimensional structure of the FKBP5 gene, which allows direct interaction between the glucocorticoid response element at intron 2 and the promoter region.30 This leads to higher FKBP5 induction by glucocorticoids, reduced GR sensitivity and consequently to a prolonged cortisol response following stress exposure.30 This corresponds well with findings of reduced GR sensitivity32,44 and enhanced cortisol responses to stress in healthy individuals carrying the high induction risk allele.33,34 Furthermore, higher FKBP5 mRNA expression in peripheral blood hours after the traumatic experience predicted PTSD symptom development in survivors 4 months later.63

However, the described relationship between FKBP5 risk genotype, higher FKBP5 expression, relative GR resistance and prolonged cortisol response seems to be only valid for PTSD-unaffected individuals. In contrast, carriers of the FKBP5 risk genotype with PTSD show enhanced GR sensitivity compared with non-carriers,32,44 corresponding well to repeated findings of GR supersensitivity in PTSD.26 In addition, lower FKBP5 gene expression has been reported in individuals with PTSD,43,64,65 and was associated with FKBP5 risk genotype.43 Furthermore, two recent studies reported an increase in FKBP5 gene expression as a marker for successful exposure-based trauma therapy,65,66 which was accompanied by an increase in plasma cortisol in one of the studies.66 In line with these findings, cortisol administration has been shown to improve exposure therapy success60, 61, 62 and to reduce symptoms in PTSD.67

The present study is the first to show that the FKBP5 genotype modulates psychotherapeutic outcome. Reasons for the reduced long-term therapeutic benefits in risk allele carriers may include stronger stress reactions at the time of trauma and hence stronger memories of the encountered traumata, which are more resistant to modification. On the other hand, initial evidence indicates that once PTSD is developed, FKBP5 risk genotype may be associated with higher GR sensitivity and hence a rapid reduction in cortisol levels following stress.32,44 Assuming that exposure to the traumatic experiences during psychotherapy triggers the stress response, a shortened cortisol response may impair the process of extinction learning or extinction memory consolidation,28 which could explain the resurgence of symptoms in T allele carriers.

We did not find a three-way interaction effect of time, FKBP5 genotype and traumatic load. In other words, genotype influenced the symptom improvement following NET; however, this effect was not moderated by traumatic load. Instead, the number of traumatic events experienced increased PTSD symptom severity at all time points. This result replicates earlier findings of a dose-dependent effect of traumatic load on PTSD symptom severity1,68 and extends them by illustrating that higher trauma load also leads to higher PTSD symptoms after treatment. Several explanations may account for the lack of an interaction effect. First of all, genetic risk × trauma exposure interaction effects might be more central to the onset of PTSD than to its treatment. However, our results do not exclude the possibility of an interaction with childhood trauma, which was found in previous investigations.30,32,69 Our trauma questionnaire only includes four items of experienced or witnessed physical childhood abuse and we did not find any interaction effect with this assessment of childhood trauma. A more detailed assessment of childhood trauma and the investigation of a larger sample with greater variations in childhood trauma might be required to detect potential interactions. The relatively small sample size clearly represents a limitation of this study, as it prevents the assessment of potential underlying population stratification. Replication studies with much larger samples are warranted to confirm the moderating role of FKBP5 on trauma therapy outcome.

Nevertheless, this investigation provides initial evidence of a strong effect of the FKBP5 genotype that influences long-term treatment outcome at all investigated levels of traumatic load. What do these results imply for PTSD treatment development? According to a meta-analysis performed by Bradley et al.10 approximately one-third of clients treated with exposure-based therapies still meet diagnostic criteria for PTSD. Comparable rates (32%) were found 12 months after treatment with NET in survivors of the Lord's Resistance Army war in Northern Uganda.47 Similarly, 31% of our total study population still met DSM-IV criteria for PTSD 10 months after treatment completion; however, all of them were carriers of the FKBP5 rs1360780 T allele. Given the strong effects of the FKBP5 genotype on treatment outcome in this study, in combination with the central role of FKBP5 in the regulation of the stress response, this molecule seems to be an interesting drug target for the treatment of stress-related disorders69,70 or for the pharmacological enhancement of psychotherapeutic effectiveness.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by a grant of the German Research Foundation (DFG) awarded to ITK, DQ and AP (D-CH programme), by a doctoral scholarship of the German National Academic Foundation (Studienstiftung des deutschen Volkes) awarded to SW and by the Swiss National Science Foundation (Sinergia grant CRSI33_130080 to DQ and AP). We would like to thank the team of Ugandan therapists for conducting therapies and diagnostic interviews of highest quality, and for their commitment, empathy and professionalism in the work with traumatized survivors. We thank the non-governmental organization vivo international for the fruitful cooperation.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Translational Psychiatry website (http://www.nature.com/tp)

Supplementary Material

References

- Kolassa IT, Ertl V, Kolassa S, Onyut LP, Elbert T. The probability of spontaneous remission from PTSD depends on the number of traumatic event types experienced. Psychol Trauma. 2010;3:169–174. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52:1048–1060. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuner F, Schauer M, Karunakara U, Klaschik C, Robert C, Elbert T. Psychological trauma and evidence for enhanced vulnerability for posttraumatic stress disorder through previous trauma among West Nile refugees. BMC Psychiatry. 2004;4:34. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-4-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubzansky LD, Bordelois P, Jun HJ, Roberts AL, Cerda M, Bluestone N, et al. The weight of traumatic stress: a prospective study of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and weight status in women. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;71:44–51. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.2798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaesmer H, Brahler E, Gundel H, Riedel-Heller SG. The association of traumatic experiences and posttraumatic stress disorder with physical morbidity in old age: a German population-based study. Psychosom Med. 2011;73:401–406. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31821b47e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakupcak M, Cook J, Imel Z, Fontana A, Rosenheck R, McFall M. Posttraumatic stress disorder as a risk factor for suicidal ideation in Iraq and Afghanistan War veterans. J Trauma Stress. 2009;22:303–306. doi: 10.1002/jts.20423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisson JI, Ehlers A, Matthews R, Pilling S, Richards D, Turner S. Psychological treatments for chronic post-traumatic stress disorder. Systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;190:97–104. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.021402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers A, Bisson J, Clark DM, Creamer M, Pilling S, Richards D, et al. Do all psychological treatments really work the same in posttraumatic stress disorder. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30:269–276. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley R, Greene J, Russ E, Dutra L, Westen D. A multidimensional meta-analysis of psychotherapy for PTSD. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:214–227. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.2.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbert T, Schauer M. Burnt into memory. Nature. 2002;419:883. doi: 10.1038/419883a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jovanovic T, Ressler KJ. How the neurocircuitry and genetics of fear inhibition may inform our understanding of PTSD. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:648–662. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09071074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbaum BO, Davis M. Applying learning principles to the treatment of post-trauma reactions. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;1008:112–121. doi: 10.1196/annals.1301.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- True WR, Rice J, Eisen SA, Heath AC, Goldberg J, Lyons MJ, et al. A twin study of genetic and environmental contributions to liability for posttraumatic stress symptoms. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50:257–264. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820160019002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein MB, Jang KL, Taylor S, Vernon PA, Livesley WJ. Genetic and environmental influences on trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms: a twin study. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1675–1681. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.10.1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilker S, Kolassa IT. The formation of a neural fear network in posttraumatic stress disorder: Insights from molecular genetics. Clin Psychol Sci. 2013;1:452–469. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant RA, Felmingham KL, Falconer EM, Pe Benito L, Dobson-Stone C, Pierce KD, et al. Preliminary evidence of the short allele of the serotonin transporter gene predicting poor response to cognitive behavior therapy in posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:1217–1219. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felmingham KL, Dobson-Stone C, Schofield PR, Quirk GJ, Bryant RA. The brain-derived neurotrophic factor Val66Met polymorphism predicts response to exposure therapy in posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73:1059–1063. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.10.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pervanidou P, Chrousos GP. Neuroendocrinology of post-traumatic stress disorder. Prog Brain Res. 2010;182:149–160. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(10)82005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapolsky RM, Romero LM, Munck AU. How do glucocorticoids influence stress responses? Integrating permissive, suppressive, stimulatory, and preparative actions. Endocr Rev. 2000;21:55–89. doi: 10.1210/edrv.21.1.0389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wochnik GM, Ruegg J, Abel GA, Schmidt U, Holsboer F, Rein T. FK506-binding proteins 51 and 52 differentially regulate dynein interaction and nuclear translocation of the glucocorticoid receptor in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:4609–4616. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407498200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denny WB, Valentine DL, Reynolds PD, Smith DF, Scammell JG. Squirrel monkey immunophilin FKBP51 is a potent inhibitor of glucocorticoid receptor binding. Endocrinology. 2000;141:4107–4113. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.11.7785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubler TR, Scammell JG. Intronic hormone response elements mediate regulation of FKBP5 by progestins and glucocorticoids. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2004;9:243–252. doi: 10.1379/CSC-32R.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeer H, Hendriks-Stegeman BI, van der Burg B, van Buul-Offers SC, Jansen M. Glucocorticoid-induced increase in lymphocytic FKBP51 messenger ribonucleic acid expression: a potential marker for glucocorticoid sensitivity, potency, and bioavailability. J Clin Endocrin Metab. 2003;88:277–284. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-020354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder EB. The role of FKBP5, a co-chaperone of the glucocorticoid receptor in the pathogenesis and therapy of affective and anxiety disorders. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34:S186–S195. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yehuda R. Status of glucocorticoid alterations in post-traumatic stress disorder. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1179:56–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04979.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Zuiden M, Kavelaars A, Geuze E, Olff M, Heijnen CJ. Predicting PTSD: pre-existing vulnerabilities in glucocorticoid-signaling and implications for preventive interventions. Brain Behav Immun. 2013;30:12–21. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2012.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Quervain DJ-F, Aerni A, Schelling G, Roozendaal B. Glucocorticoids and the regulation of memory in health and disease. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2009;30:358–370. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitman RK, Rasmusson AM, Koenen KC, Shin LM, Orr SP, Gilbertson MW, et al. Biological studies of post-traumatic stress disorder. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:769–787. doi: 10.1038/nrn3339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klengel T, Mehta D, Anacker C, Rex-Haffner M, Pruessner JC, Pariante CM, et al. Allele-specific FKBP5 DNA demethylation mediates gene-childhood trauma interactions. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:33–41. doi: 10.1038/nn.3275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder EB, Salyakina D, Lichtner P, Wochnik GM, Ising M, Putz B, et al. Polymorphisms in FKBP5 are associated with increased recurrence of depressive episodes and rapid response to antidepressant treatment. Nat Genet. 2004;36:1319–1325. doi: 10.1038/ng1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder EB, Bradley RG, Liu W, Epstein MP, Deveau TC, Mercer KB, et al. Association of FKBP5 polymorphisms and childhood abuse with risk of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in adults. JAMA. 2008;299:1291–1305. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.11.1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ising M, Depping AM, Siebertz A, Lucae S, Unschuld PG, Kloiber S, et al. Polymorphisms in the FKBP5 gene region modulate recovery from psychosocial stress in healthy controls. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;28:389–398. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchmann AF, Holz N, Boecker R, Blomeyer D, Rietschel M, Witt SH, et al. Moderating role of FKBP5 genotype in the impact of childhood adversity on cortisol stress response during adulthood. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;24:837–845. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahon PB, Zandi PP, Potash JB, Nestadt G, Wand GS. Genetic association of FKBP5 and CRHR1 with cortisol response to acute psychosocial stress in healthy adults. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2013;227:231–241. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2956-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann P, Bruckl T, Nocon A, Pfister H, Binder EB, Uhr M, et al. Interaction of FKBP5 gene variants and adverse life events in predicting depression onset: results from a 10-year prospective community study. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:1107–1116. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10111577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lekman M, Laje G, Charney D, Rush AJ, Wilson AF, Sorant AJ, et al. The FKBP5-gene in depression and treatment response—an association study in the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) Cohort. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63:1103–1110. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papiol S, Arias B, Gasto C, Gutierrez B, Catalan R, Fananas L. Genetic variability at HPA axis in major depression and clinical response to antidepressant treatment. J Affect Disord. 2007;104:83–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minelli A, Maffioletti E, Cloninger CR, Magri C, Sartori R, Bortolomasi M, et al. Role of allelic variants of FK506-binding protein 51 (fkbp5) gene in the development of anxiety disorders. Depress Anxiety. 2013;30:1170–1176. doi: 10.1002/da.22158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy A, Gorodetsky E, Yuan Q, Goldman D, Enoch MA. Interaction of FKBP5, a stress-related gene, with childhood trauma increases the risk for attempting suicide. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:1674–1683. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenen KC, Saxe G, Purcell S, Smoller JW, Bartholomew D, Miller A, et al. Polymorphisms in FKBP5 are associated with peritraumatic dissociation in medically injured children. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10:1058–1059. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie P, Kranzler HR, Poling J, Stein MB, Anton RF, Farrer LA, et al. Interaction of FKBP5 with childhood adversity on risk for post-traumatic stress disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:1684–1692. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarapas C, Cai G, Bierer LM, Golier JA, Galea S, Ising M, et al. Genetic markers for PTSD risk and resilience among survivors of the World Trade Center attacks. Dis Markers. 2011;30:101–110. doi: 10.3233/DMA-2011-0764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta D, Gonik M, Klengel T, Rex-Haffner M, Menke A, Rubel J, et al. Using polymorphisms in FKBP5 to define biologically distinct subtypes of posttraumatic stress disorder: evidence from endocrine and gene expression studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:901–910. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schauer M, Neuner F, Elbert T.Narrative Exposure Therapy. A Short- Term intervention for Traumatic Stress Disorders after War, Terror or Torture2nd edn, Hogrefe & Huber: Göttingen, Germany; 2011 [Google Scholar]

- Robjant K, Fazel M. The emerging evidence for narrative exposure therapy: a review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30:1030–1039. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ertl V, Pfeiffer A, Schauer E, Elbert T, Neuner F. Community-implemented trauma therapy for former child soldiers in Northern Uganda: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2011;306:503–512. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Cashman L, Jaycox L, Perry K. The validation of a self-report measure of posttraumatic stress disorder: The Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale. Psychol Assess. 1997;9:445–451. [Google Scholar]

- Wilker S, Kolassa S, Vogler C, Lingenfelder B, Elbert T, Papassotiropoulos A, et al. The role of memory-related gene WWC1 (KIBRA) in lifetime posttraumatic stress disorder: evidence from two independent samples from African conflict regions. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;74:664–671. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59:22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ertl V, Pfeiffer A, Saile R, Schauer E, Elbert T, Neuner F. Validation of a mental health assessment in an African conflict population. Psychol Assess. 2010;22:318–324. doi: 10.1037/a0018810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team . R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro J, Bates D, DebRoy S, Sarkar D and the R Development Core Team. nlme: Linear and Nonlinear Mixed Effects Models. R package version 3.1-111. 2013.

- Pinheiro J, Bates D. Unconstrained parametrizations for variance-covariance matrices. Stat Comput. 1996;6:289–296. [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro J, Bates D. Mixed-Effects Models in S and S-PLUS. Statistics and Computing: Springer: New York, NY, USA; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Burnham KP, Anderson DR.Model Selection and Multi-Model Inference: A Practical Information-Theoretic Approach2nd edn, Springer: New York, NY, USA; 2002 [Google Scholar]

- Hothorn T, Bretz F, Westfall P. Simultaneous inference in general parametric models. Biom J. 2008;50:346–363. doi: 10.1002/bimj.200810425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamacher-Dang TC, Engler H, Schedlowski M, Wolf OT. Stress enhances the consolidation of extinction memory in a predictive learning task. Front Behav Neurosci. 2013;7:108. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2013.00108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soravia LM, Heinrichs M, Winzeler L, Fisler M, Schmitt W, Horn H, et al. Glucocorticoids enhance in vivo exposure-based therapy of spider phobia. Depress Anxiety. 2013;31:429–435. doi: 10.1002/da.22219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Quervain DJ-F, Bentz D, Michael T, Bolt OC, Wiederhold BK, Margraf J, et al. Glucocorticoids enhance extinction-based psychotherapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:6621–6625. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018214108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentz D, Michael T, de Quervain DJ, Wilhelm FH. Enhancing exposure therapy for anxiety disorders with glucocorticoids: from basic mechanisms of emotional learning to clinical applications. J Anxiety Disord. 2010;24:223–230. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segman RH, Shefi N, Goltser-Dubner T, Friedman N, Kaminski N, Shalev AY.Peripheral blood mononuclear cell gene expression profiles identify emergent post-traumatic stress disorder among trauma survivors Mol Psychiatry 200510500–513., 425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yehuda R, Cai G, Golier JA, Sarapas C, Galea S, Ising M, et al. Gene expression patterns associated with posttraumatic stress disorder following exposure to the World Trade Center attacks. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66:708–711. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy-Gigi E, Szabo C, Kelemen O, Keri S. Association among clinical response, hippocampal volume, and FKBP5 gene expression in individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder receiving cognitive behavioral therapy. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;74:793–800. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yehuda R, Daskalakis NP, Desarnaud F, Makotkine I, Lehrner AL, Koch E, et al. Epigenetic biomarkers as predictors and correlates of symptom improvement following psychotherapy in combat veterans with PTSD. Front Psychiatry. 2013;4:118. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aerni A, Traber R, Hock C, Roozendaal B, Schelling G, Papassotiropoulos A, et al. Low-dose cortisol for symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1488–1490. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.8.1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollica RF, McInnes K, Poole C, Tor S. Dose-effect relationships of trauma to symptoms of depression and post-traumatic stress disorder among Cambodian survivors of mass violence. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;173:482–488. doi: 10.1192/bjp.173.6.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zannas AS, Binder EB. Gene-environment interactions at the FKBP5 locus: sensitive periods, mechanisms and pleiotropism. Genes Brain Behav. 2014;13:25–37. doi: 10.1111/gbb.12104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt MV, Paez-Pereda M, Holsboer F, Hausch F. The prospect of FKBP51 as a drug target. ChemMedChem. 2012;7:1351–1359. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201200137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.