Summary

Coats plus is a rare recessive disorder characterized by intracranial calcifications, hematological abnormalities, and retinal vascular defects. This disease results from mutations in CTC1, a member of the CTC1–STN1–TEN1 (CST) complex critical for telomere replication. Telomeres are specialized DNA/protein structures essential for the maintenance of genome stability. Several patients with Coats plus display critically shortened telomeres, suggesting that telomere dysfunction plays an important role in disease pathogenesis. These patients inherit CTC1 mutations in a compound heterozygous manner, with one allele encoding a frameshift mutant and the other a missense mutant. How these mutations impact upon telomere function is unknown. We report here the first biochemical characterization of human CTC1 mutations. We found that all CTC1 frameshift mutations generated truncated or unstable protein products, none of which were able to form a complex with STN1–TEN1 on telomeres, resulting in progressive telomere shortening and formation of fused chromosomes. Missense mutations are able to form the CST complex at telomeres, but their expression levels are often repressed by the frameshift mutants. Our results also demonstrate for the first time that CTC1 mutations promote telomere dysfunction by decreasing the stability of STN1 to reduce its ability to interact with DNA Polα, thus highlighting a previously unknown mechanism to induce telomere dysfunction.

Keywords: aging, mouse models, telomeres

Introduction

Telomeres are nucleoprotein complexes that play important roles in the maintenance of genome stability. They cap chromosome ends to prevent the activation of DNA damage and repair pathways that would otherwise result in cell cycle arrest and apoptosis (Greider, 1996). Mammalian telomeres consist of TTAGGG repetitive sequences and are maintained by the enzyme telomerase, a specialized ribonucleoprotein complex that includes an RNA template (TERC or TR) and a reverse transcriptase catalytic subunit (TERT). Telomerase is normally expressed only in stem and progenitor cells. In somatic cells, the lack of telomerase results in progressive telomere shortening. Overexpression of telomerase in somatic cells extends telomeres, preserving genomic stability, and prevents the onset of replicative senescence (Bodnar et al., 1997; Weinrich et al., 1997). In addition to telomerase, mammalian telomeres are bound by six telomere-specific binding proteins, termed ‘the shelterin complex’ that caps and protects telomeres from inappropriately activating DNA damage response (DDR) checkpoints (Palm & de Lange, 2008). Three sequence-specific DNA-binding proteins are recruited to chromosomal ends: the duplex telomere-binding proteins, TRF1 and TRF2-RAP1, and the single-stranded (ss) telomere DNA-binding protein POT1. POT1 forms a heterodimer with TPP1, and this complex is tethered to telomeres through the protein TIN2 (Chan & Chang, 2010). The proper positioning of POT1 on telomeres is necessary to prevent the initiation of an ATR-dependent DDR at telomeres (He et al., 2006, 2009; Hockemeyer et al., 2006; Wu et al., 2006; Denchi & de Lange, 2007; Guo et al., 2007).

Defects in telomere maintenance pathways contribute directly to both acquired and inherited human disorders termed ‘telomopathies’ (Calado & Young, 2008, 2009; Hills & Lansdorp, 2009; Young, 2010; Shtessel & Ahmed, 2011). Critical telomere shortening results in proliferative defects in hematopoietic stem cells, leading to the onset of bone marrow (BM) failure syndromes (Allsopp et al., 2003). Dyskeratosis congenita (DC) is characterized a high incidence of BM failure, distinct cutaneous phenotypes, age-related pathologies including hair greying and an increased incidence of cancer (Dokal, 2001). DC is genetically heterogeneous and is caused by mutations in genes encoding proteins involved in telomere homeostasis. Autosomal dominant and recessive forms of this disease are due to mutations in hTERC and hTERT, respectively (Vulliamy et al., 2001, 2004), while X-linked DC is a result of mutations in Dyskerin (DC1), a small nuclear RNA–binding protein that interacts with TERC and is required for telomerase function (Mitchell et al., 1999). Mutations in the shelterin component TIN2 result in a very severe form of DC, with patients bearing very short telomeres and displaying premature BM failure as early as 10 years of age, even though telomerase function remains intact (Savage et al., 2008; Walne et al., 2008). These observations strongly implicate defects in telomere maintenance as a mechanism for disease formation and suggest that DC could arise not only from loss of telomerase activity but also from defects in the capping functions of the shelterin complex.

The recent discovery that BM failure and telomere dysfunction are observed in patients with the human disorder Coats plus syndrome provides yet another compelling link between disruption of telomere homeostasis and human pathology (Armanios, 2012; Savage, 2012). Whole-exome sequencing revealed that missense mutations in the gene encoding the telomere protein conserved telomere maintenance component 1 (CTC1) causes Coats plus, a rare autosomal recessive disorder characterized by retinal telangiectasia, intracranial calcifications, osteopenia, and gastrointestinal bleeding (Anderson et al., 2012; Polvi et al., 2012; Walne et al., 2012). Some affected individuals develop hair greying, nail dystrophy, and normocytic anemia, phenotypes resembling DC (Anderson et al., 2012; Polvi et al., 2012; Walne et al., 2012). Indeed, some patients with Coats plus possess very short telomeres, suggesting that telomere maintenance function is compromised in these patients (Anderson et al., 2012; Keller et al., 2012). CTC1 encodes a highly evolutionarily conserved protein that possesses three oligosaccharide–oligonucleotide (OB) folds, protein domains that interact with other proteins or with ss DNA (Flynn & Zou, 2010). CTC1 was originally discovered as a protein that stimulates DNA Polymerase alpha (Polα)–primase activity, suggesting that it plays an essential role in DNA replication (Goulian & Heard, 1990; Goulian et al., 1990; Casteel et al., 2009).

The exciting discovery that CTC1 is a member of the mammalian CTC1–STN1–TEN1 (CST) complex implicates CTC1 in telomere replication (Miyake et al., 2009; Surovtseva et al., 2009). In yeast, this complex (with Cdc13 as the putative homolog of CTC1) interacts with Polα and couples telomeric C- and G-strand synthesis during DNA replication, preventing the formation of excessively long ss G-overhangs (Chandra et al., 2001). In contrast to the shelterin complex, which is primarily involved in telomere end protection, the mammalian CST complex promotes telomere replication and does not play a direct role in repressing a DDR at telomeres (Gu et al., 2012). Instead, it promotes both C-strand fill-in following G-strand extension by telomerase and repressing excessive C-strand resection by interacting with POT1 (Gu et al., 2012; Huang et al., 2012; Stewart et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2012). In mice, deletion of CTC1 results in rapid loss of C-strand telomeric DNA, leading to catastrophic telomere loss and premature death from total BM failure (Gu et al., 2012). Taken together, these results suggest that CTC1 is critically important for telomere length maintenance by promoting efficient telomere replication and C-strand protection.

Patients with Coats plus are compound heterozygous for two different CTC1 mutations, with one allele harboring a frameshift mutation and the other a missense variant (Anderson et al., 2012; Keller et al., 2012; Polvi et al., 2012; Walne et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2012). Given the early lethality phenotype observed in CTC1 null mice, it is perhaps not surprising that no Coats plus patients have been discovered with homozygous frameshift mutations predicted to generate severely truncated protein products. Little is known about how the plethora of CTC1 mutations impacts upon telomere homeostasis in patients, given the protein’s large size and lack of systematic analysis of its protein domains. Because characterization of human mutations has often yielded valuable insights into basic biological functions perturbed by the mutations, we investigated how human CTC1 mutations disrupted normal protein functions at telomeres. We found that CTC1 frameshift mutations generated truncated protein products, none of which were able to form a complex with STN1–TEN1 on telomeres, resulting in progressive telomere shortening and formation of fused chromosomes. We also demonstrate for the first time that CTC1 mutations promote telomere dysfunction by decreasing the stability of STN1 to reduce its ability to interact with DNA Polα, and highlight a previously unknown mechanism to induce telomere dysfunction.

Results

Characterizations of the telomere-binding properties of CTC1 mutants

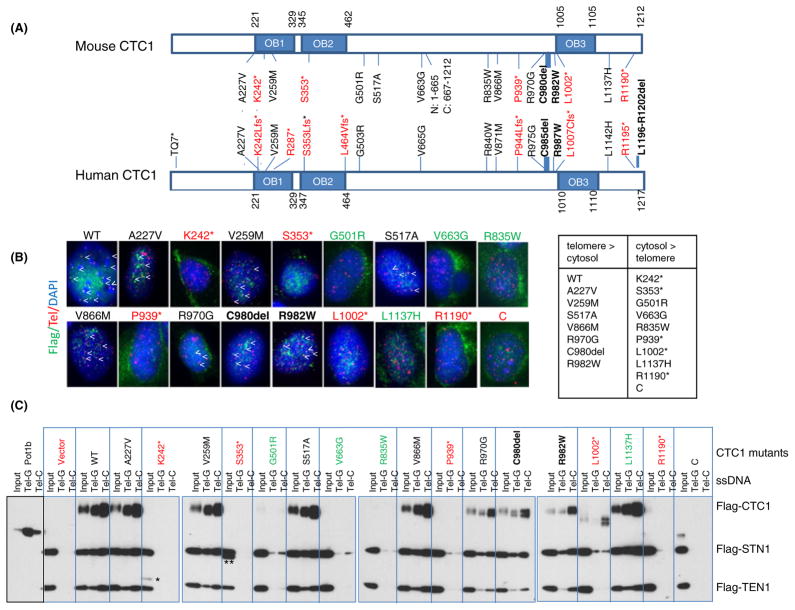

Four independent studies revealed that of 25 distinct CTC1 mutations identified so far, 14 induce missense mutations leading to single amino acid changes, some involving highly evolutionarily conserved amino acids (Fig. 1A; Anderson et al., 2012; Keller et al., 2012; Polvi et al., 2012; Walne et al., 2012). Eight are frameshift mutations resulting in the generation of premature stop codons likely to form truncated protein products (denoted by a * in Fig. 1A), and three are internal in-frame deletions (Fig. 1A). Most of the mutations are clustered in or near the three OB folds. To understand mechanistically how these mutations impact upon CTC1 function and CST complex formation in vivo, we introduced the majority of the human CTC1 mutations into the corresponding positions in the mouse CTC1 cDNA, because all mutated human CTC1 residues are conserved in the mouse (Fig. 1A). We paid particular attention to mutations that affected more than one individual. We also generated truncation mutants containing only the N-terminus [N: amino acids (aa) 1–665] or the C-terminus (C: aa 667–1212) and a S517A mutant that abolished a potential phosphorylation site hypothesized to be important for CTC1 function (Li et al., 2009). We chose to analyze these mutations in the murine background to take advantages of our CTC1−/− mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEFs), which offers the ability to reconstitute mutant proteins while avoiding the confounding effects of endogenous CTC1. We first asked whether localization of CTC1 to telomeres was impacted by theCTC1 mutations. Were constituted WT and mutant CTC1 cDNAs into CTC1−/− MEFs and confirmed robust RNA expression (Fig. S1). While Flag-CTC1WT readily localized to telomeres, immunofluorescent signals at telomeres were not detected for any of the frameshift or truncated mutants (Fig. 1B and data not shown). It is interesting to note that the CTC1R1190* mutant, which is missing only the last 22 aa, failed to localize to telomeres. Most missense mutations and the C980delmutant were able to localize to telomeres to some extent, with the exceptions being mutants CTC1G501R, CTC1R835W, and CTC1L1137H, which displayed minimal telomeric localization.

Fig. 1.

CTC1 mutations affect telomere localization. (A) Schematic of all documented human CTC1 mutations. Corresponding mutations in mouse CTC1 analyzed in this study are illustrated. Frameshift mutations (denoted by *) are in red; missense mutations, in black; and in-frame deletions, in black (bold). OB: OB folds. N: N-terminal mutant (aa 1–665); C: C-terminal mutant (aa 667–1212). (B) Telomere PNA-FISH demonstrating the localization of Flag-CTC1WT and several Flag-CTC1 mutants to telomeres in CTC1−/− MEFs. Cells were stained with anti-Flag antibody (green), telomere PNA-FISH with Tam-OO-(CCCTAA)4 telomere peptide nucleic acid (red) and 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, blue). A minimum of 500 nuclei were analyzed per genotype. Localization of CTC1 to telomeres is indicated by arrowheads. Frameshift mutants are illustrated in red, missense or in-frame mutants that localize to telomeres are in black, and missense mutants that cannot localize to telomeres are in green. C: C-terminal truncation mutant. (C) Impact of CTC1 mutations on CST complex formation on ss telomeric DNA. WT or mutant Flag-CTC1, Flag-STN1, and Flag-TEN1 were co-expressed in 293T cells, purified, and incubated with streptavidin beads bound by biotinylated ss Tel-G (TTAGGG)6 or Tel-C (CCCTAA)6 oligonucleotides. After washing, the DNA bound CST complexes were eluted and detected by immunoblotting. Labeling scheme of mutant CTC1 is the same as in (B). Purified POT1b was used as a positive control for preferential binding to Tel-G oligos. C: C-terminal truncation mutant; *: K242*; **: CTC1S353* truncated protein products.

We next asked whether CTC1 mutants were able to form a complex with STN1 and TEN1 on ss telomeric DNA. WT and mutant Flag-tagged CTC1 cDNAs were cotransfected into 293T cells expressing Flag-STN1 and Flag-TEN1 to generate WT or mutant CST complexes. The complexes were then incubated with biotinylated TTAGGG (Tel-G) or CCCTAA (Tel-C) ss telomeric oligos. We found that Flag-CTC1WT efficiently formed a complex with Flag-STN1 and Flag-TEN1 and bound to both Tel-G and Tel-C oligo, with increased preference for Tel-C (Fig. 1C). While the CTC1K242*, CTC1S353*, CTC1P939*, CTC1R1190*, and CTC1L1002* frameshift mutants generated truncated protein products, none of them enabled CST complex formation on ss telomeric DNA (Fig. 1C). Examination of CTC1 missense mutations revealed that mutants CTC1A227V, CTC1V258M, CTC1S517A, and CTC1V866M were able to complex with STN1 and TEN1 to bind telomeric DNA (Fig. 1C). Interestingly, while CTC1L1137H efficiently complexed with STN1–TEN1 on ss telomeric DNA, it was not able to localize to telomeres in vivo (Fig. 1B, C). In contrast, mutants CTC1R970G, CTC1C980del, and CTC1R982W all showed reduced complex formation on ss telomeric DNA, suggesting that these amino acids play a role in DNA-binding (Figs 1C and 2A). Due to the very low expression of mutants CTC1G501R, CTC1V663G, and CTC1R835W, we were not able to conclusively determine whether these mutants were able to form a complex with STN1 and TEN1 (Figs 1C and 2A). Taken together, our results suggest that (i) STN1 and TEN1 cannot form a complex on ss telomeric DNA in the absence of CTC1, (ii) most missense CTC1 mutations are able to form a complex with STN1 and TEN1 on telomeres, (iii) truncated CTC1 frameshift mutants cannot form a complex with STN1–TEN1 to localize to telomeres, (iv) the last 22 aa of CTC1 are critical for protein stability, and (v) the L1137 residue is essential for telomeric localization in vivo, but not in vitro.

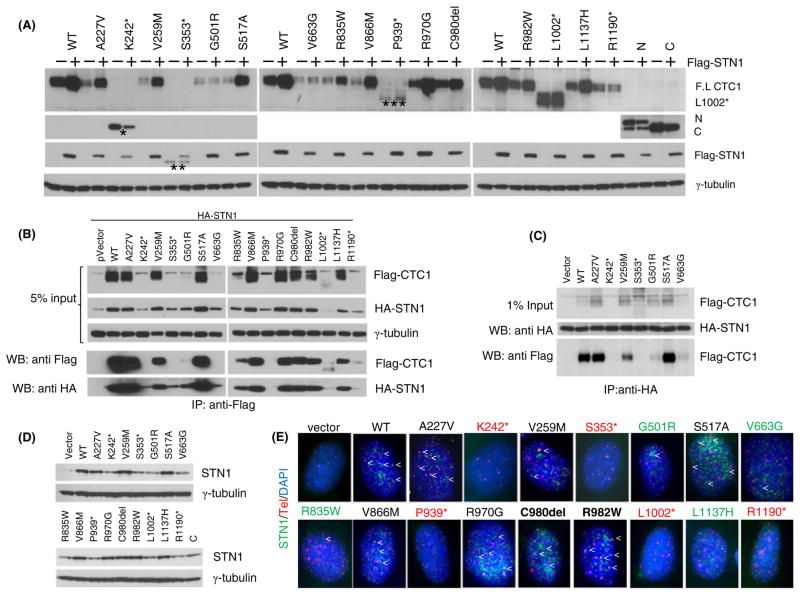

Fig. 2.

Interaction of CTC1 mutants with STN1. (A) Expression of Flag-tagged WT or CTC1 mutants in 293T cells with (+) or without (−) co-expression with Flag-STN1. *: K242*; **: S353*; ***: P939* truncated protein products. N: N-terminal truncation mutant; C: C-terminal truncation mutant. γ-tubulin served as loading control. (B) HA-STN1 was co-expressed with WT or CTC1 mutants in 293T cells, and anti-Flag antibody was used for immunoprecipitation (IP). Anti-HA and anti-Flag antibodies were used for immunodetection. γ-tubulin served as loading control. Input represents 5% of lysate used for IP. (C) Flag-tagged WT and mutant CTC1 were expressed in 293T cells, mixed with 293T lysates normalized for the amount of HA-STN1, immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibody, and immunoblotted with anti-HA antibody to detect HA-STN1 or anti-Flag to detect Flag-CTC1. γ-tubulin served as loading control and input represented 5% of lysate used for IP. (D) Expression of WT and mutant Flag-CTC1 in CTC1−/− MEFs. Endogenous STN1 was detected with an anti-STN1 antibody. γ-tubulin served as loading control. (E) Telomere PNA-FISH demonstrating the localization of endogenous STN1 to telomeres following expression of Flag-tagged WT or CTC1 mutants in CTC1−/− MEFs. Cells were stained with anti-STN1 antibody (green), telomere PNA-FISH, with Tam-OO-(CCCTAA)4 telomere peptide nucleic acid (red) and 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, blue). A minimum of 150 nuclei were analyzed per genotype. Localization of STN1 to telomeres is indicated by arrowheads. Black labeling: missense mutants localizing to telomeres; red: frameshift mutants do not localize to telomeres; green: missense mutants with minimal telomere localization.

CST complex formation is disrupted by mutations in CTC1

The reduced expression levels of several CTC1 mutants suggest that they might be intrinsically unstable. We have previously shown that in CTC1 null MEFs, STN1 levels were markedly reduced, suggesting that both proteins are most stable when forming a complex in vivo (Gu et al., 2012). This notion is supported by our observations that TEN1 and STN1 stabilize each other, and STN1 and CTC1 stabilize each other (Fig. S2). We therefore asked whether STN1 expression was required to stabilize the CTC1 mutants. Co-expression of Flag-STN1 with Flag-CTC1WT resulted in increased Flag-CTC1WT levels by approximately five fold (Fig. 2A). Overexpression of Flag-STN1 was not able to stabilize any of the frameshift mutants. Instead, it was able to stabilize most missense full-length CTC1 mutants to levels comparable to that observed for CTC1WT (Fig. 2A). The only exceptions were CTC1G501R and CTC1V663G in which Flag-STN1 expression did not result in increased protein stabilization. This result suggests the possibility that Flag-STN1 was not able to interact with these CTC1 mutants. To test this hypothesis, we performed reciprocal co-immunoprecipitation experiments and found that HA-STN1 bound poorly to both Flag-CTC1G501R and Flag-CTC1V663G (Fig. 2B, C). We then reconstituted WT or CTC1 mutants into CTC1−/− MEFs and examined the levels of endogenous STN1. While expression of Flag-CTC1WT readily increased endogenous STN1 levels, expression of Flag-CTC1G501R and Flag-CTC1V663G mutants (as well as all frameshift mutants and to some extent mutant Flag-CTC1R835W) resulted in markedly reduced endogenous STN1 levels (Fig. 2D). Immunofluorescence analysis confirmed the reduced levels of endogenous STN1 localization to telomeres in CTC1−/− MEFs expressing these CTC1 mutants (Fig. 2E). Because STN1–TEN1 cannot localize to telomeres in the absence of CTC1 (Fig. 1C), these results suggest that expression of CTC1 frameshift and some missense mutants led to a reduction of CST complex formation on telomeres. In addition, CTC1 residues G501 and V663 are also required for robust interactions with STN1.

CTC1 mutations impact upon telomere length maintenance

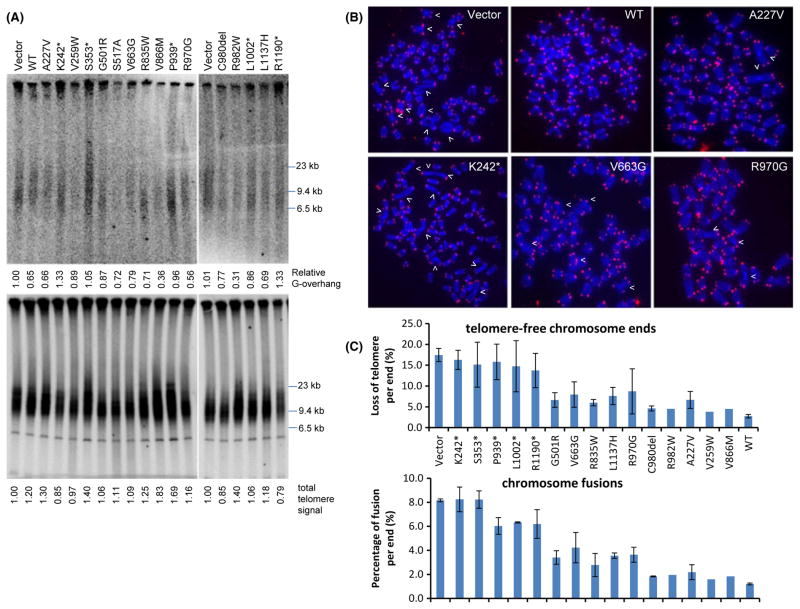

A striking characteristic of CTC1−/− mice is the rapid telomere attrition due to loss of the telomeric C-strand, resulting in the generation of ss G-overhangs. Progressive telomere attrition in the absence of CTC1 leads to the formation of end-to-end chromosome fusions, culminating in complete BM failure and premature death (Gu et al., 2012). Critically shortened telomeres were also observed in some Coats Plus patients with phenotypes resembling DC, including those bearing the K242*/R987W and R287*/C985del CTC1 mutations (Anderson et al., 2012; Keller et al., 2012). However, it was not clear whether all CTC1 mutations resulted in telomere shortening, because two reports failed to demonstrate any telomere shortening in patients bearing CTC1 mutations (V665G/L1142H mutations; Polvi et al., 2012; Walne et al., 2012). To address this discrepancy, we stably reconstituted WT and CTC1 mutants into early passage CTC1 null MEFs that have not yet experienced any observable telomeric defects. CTC1−/− MEFs expressing vector, WT and CTC1 mutants were passaged for 10 population doublings. Because total telomere length was not expected to change dramatically during this short time period, we monitored the length of the G-overhang, which we have shown previously to elongate in CTC1Δ/Δ MEFs as rapidly as 9 days after Cre-mediated deletion of CTC1 floxed alleles (Gu et al., 2012). We also examined the number of telomere-free chromosome ends and fused chromosomes in reconstituted MEFs by telomere PNA-FISH. Compared with CTC1−/− MEFs expressing only vector DNA, expression of CTC1WT reduced ss G-overhang formation, the number of chromosomal ends lacking telomeric signals, and the number of fused chromosomes observed (Fig. 3). A similar phenotype was observed in CTC1−/− MEFs expressing the CTC1C980del, CTC1R982W, CTC1A227V, CTC1V259W, and CTC1V866M missense mutants, suggesting that inheritance of these mutations likely will not dramatically perturb telomere functions (Fig. 3). In contrast, expression of all CTC1 frameshift mutations examined resulted in overhang elongation, increased telomere-free chromosome ends, and increased number of chromosome fusions (to involve approximately 8% of all chromosome ends; Fig. 3). This result is not surprising given that the frameshift mutations were not able to form any CST complexes at telomeres. More interesting are the missense mutations CTC1G501R, CTC1V663G, CTC1R835W, CTC1L1137H, and CTC1R970G: expression of these mutants all resulted in only a 4–10% increase in the number of telomere-free chromosome ends and an approximately 4% increase in the number of fused chromosomes observed with a minimal increase in G-overhang (Fig. 3). Because CTC1G501R and CTC1V663G both interacted poorly with STN1 but were still able to maintain telomere length (Fig. 2B–E), it is likely that CTC1’s interaction with STN1 through these two amino acids is not essential for complete telomere length maintenance.

Fig. 3.

CTC1 mutants affect telomere length. (A) HinfI/RsaI-digested genomic DNA isolated from CTC1−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) expressing WT or CTC1 mutants was hybridized with a 32P-labeled [CCCTAA]4-oligo under nondenaturation (top) conditions to detect 3′ ss G-overhangs and denaturation (bottom) conditions to detect total telomere DNA. 3′ ss G-overhangs and total telomere signal intensity (%) were quantified by setting DNA from CTC1−/− MEFs expressing vector control as 100%. (B) Telomere PNA-FISH and DAPI analysis on metaphase chromosome spreads of CTC1−/− MEFs stably expressing either Flag-tagged WT or CTC1 mutants, using Tam-OO-(CCCTAA)4 telomere peptide nucleic acid (red) and DAPI (blue). White arrowheads: chromosome fusion sites. (C) Quantification of chromosome aberrations in (B). Top, telomere signal-free chromosome ends; bottom, chromosome fusions. A minimum of 30 metaphases were examined. Mean values were derived from at least three experiments. Error bars: SEM.

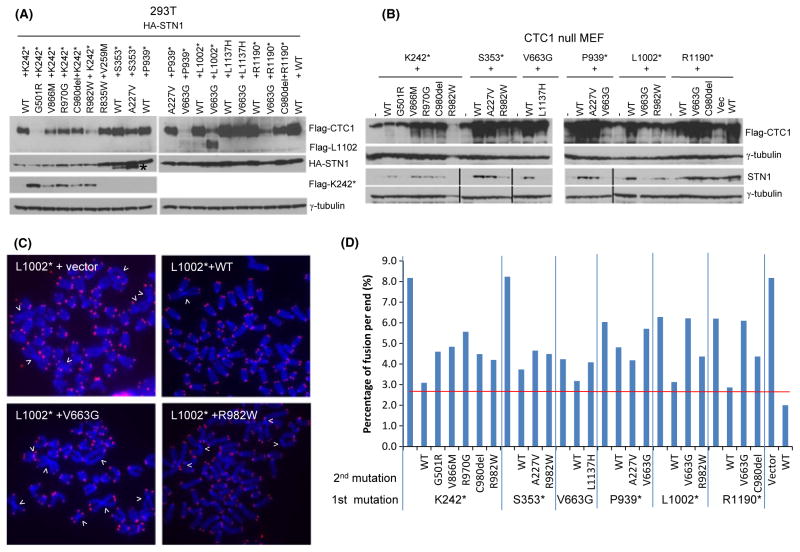

Characterization of CTC1 compound heterozygous mutations in vivo

Because patients with Coats plus are compound heterozygous for two different CTC1 mutations, to more faithfully model the human disease condition, we generated cell lines expressing 14 of the most common compound heterozygous mutation pairs. Most of these mutant pairs consisted of one CTC1 allele containing a frameshift mutation with the other allele containing a missense mutation (Anderson et al., 2012; Polvi et al., 2012). We first ascertained that co-expression of both CTC1 mutants in 293T cells stably expressing HA-STN1 resulted in detectable protein products (Fig. 4A). We found that co-expression of CTC1WT with CTC1 mutants repressed the expression of the mutant proteins (e.g., CTC1WT repressed the expression of both CTC1K242* and CTC1S353*; Fig. 4A). This result likely explains why individuals heterozygous for CTC1 mutations do not develop any disease phenotypes (Anderson et al., 2012; Polvi et al., 2012). Expression of CTC1K242* repressed the expression of CTC1G501R and CTC1R982W (Fig. 4A). Because CTC1G501R and CTC1R982W all have near WT functions at telomeres, inheritance of the CTC1K242*/CTC1G501R and CTC1K242*/CTC1R982W mutation pairs likely results in telomere dysfunction. Indeed, we found that when expressed in CTC1−/− MEFs, these mutant pairs all displayed higher levels of fused chromosomes than the CTC1K242*/CTC1WT combination (Fig. 4D). In addition, all cells expressing CTC1K242* displayed markedly reduced HA-STN1 levels, suggesting that expression of this truncated protein disrupted CST complex formation despite robust expression of the other missense alleles. Because monitoring endogenous STN1 levels in CTC1−/− MEFs is a sensitive method to probe the ability of a particular CTC1 mutant to form CST complexes at telomeres (Fig. 2D, E), we expressed CTC1K242* and its missense mutant partners in CTC1−/− MEFs and monitored endogenous STN1 levels. We confirmed that expression of CTC1K242* resulted in greatly reduced endogenous STN1 levels that cannot be rescued by the expression of any missense mutants or CTC1WT (Fig. 4B). Mutant combinations CTC1K242*/CTC1G501R, CTC1K242*/CTC1R982W, CTC1S353*/CTC1R982W, CTC1V663G/CTC1L1137H, CTC1P939*/CTC1V663G, CTC1L1002*/CTC1V663G and CTC1L1002*/CTC1R982W were especially potent in reducing endogenous STN1 levels. Introducing these mutant combinations into CTC1−/− MEFs resulted in increased number of fused chromosomes, suggesting compromised telomere length maintenance in the absence of functional CST complex formation on telomeres (Fig. 4C, D). Taken together, these results suggest that telomere dysfunction is a prominent feature of cells containing compound heterozygous CTC1 mutations, although the degree of telomere dysfunction appears to vary with the types of mutations inherited.

Fig. 4.

Characterization of CTC1 compound heterozygous mutations in vivo. (A) Lysates from 293T cells stably expressing HA-STN1 and the indicated Flag-CTC1 mutations were probed with anti-Flag and anti-HA antibodies. γ-tubulin served as loading control. (B) Flag-tagged WT and mutant CTC1 were expressed in CTC1−/− MEFs and lysates probed with antibodies against Flag and STN1. Dual expression of mutant CTC1 in CTC1−/− MEFs was performed as described in Experimental procedures. γ-tubulin served as loading control. (C) Telomere PNA-FISH and DAPI analysis on metaphase chromosome spreads of CTC1−/− MEFs stably expressing either WT or compound heterozygous CTC1 mutants indicated in (B), using Tam-OO-(CCCTAA)4 telomere peptide nucleic acid (red) and DAPI (blue). White arrowheads: fused chromosomes. (D) Quantification of chromosome fusions in (C). A minimum of 30 metaphases were examined. Red horizontal line refers to average number of chromosome fusions from seven independent experiments of CTC1 mutant cell lines co-expressing WT CTC1.

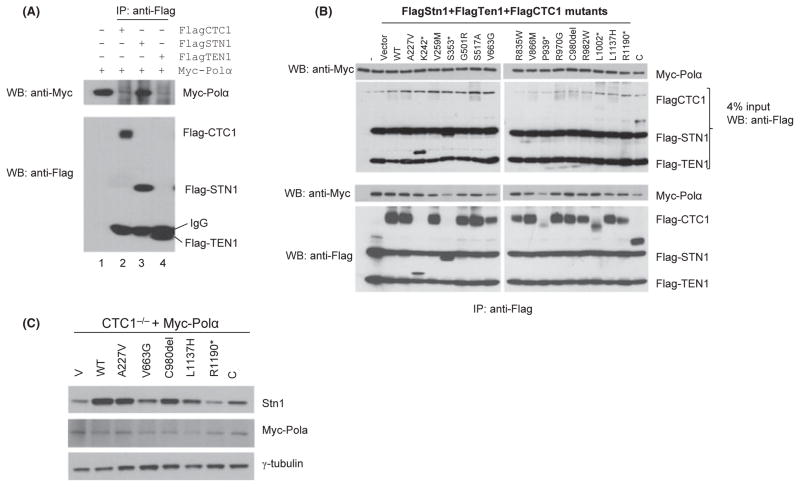

CTC1 modulates the interaction of DNA Polα with STN1

We have previously shown that CTC1 is required for efficient replication of the telomeric C-strand (Gu et al., 2012). The CST complex is required to facilitate priming and synthesis of telomere DNA on the lagging-strand template and promotes re-initiation of lagging telomere DNA synthesis by DNA Polα at stalled replication forks (Gu et al., 2012; Stewart et al., 2012). To determine the impact of CTC1 mutations on Polα’s interaction with components of the CST complex, we first performed IP experiments between Myc-Polα and individual components of the CST complex. To our surprise, we found that only Flag-STN1 was able to interact with Myc-Polα (Fig. 5A). We next transiently expressed both Myc-Polα and either WT or CTC1 mutants into 293T cells already stably expressing both Flag-STN1 and Flag-TEN1. Quantitative IP Western blotting was able to detect Myc-Polα in all cells expressing WT and mutant CTC1, even those expressing truncated CTC1 proteins, confirming our results that stable interaction between STN1 and DNA Polα did not depend on the presence of CTC1. However, Myc-Polα levels were lower in cells expressing truncated CTC1 proteins, suggesting that these mutants might be adversely affecting Myc-Polα levels by impacting upon Flag-STN1 stability (Fig. 5B). To test this hypothesis, we expressed various CTC1 mutants in CTC1−/− MEFs stably expressing Myc-Polα. Western blotting analysis revealed that all MEFs expressing CTC1 mutants (e.g., CTC1V663G) resulted in reduced endogenous STN1 levels and showed a corresponding reduction in Polα levels (Fig. 5C). These results suggest that CTC1 mutations impacted upon STN1’s ability to interact with DNA Polα by decreasing the stability of STN1.

Fig. 5.

CTC1 modulates the interaction between STN1 and DNA Polα. (A) STN1 alone interacts with DNA Polα. Flag-CTC1, Flag-STN1, and Flag-TEN1 were expressed individually in 293T cells and lysates mixed with lysates containing Myc-Polα. Anti-Flag antibody was used for immunoprecipitation (IP) and immunoblots detected by anti-Flag and anti-Myc antibodies. (B) CTC1 WT or mutants were expressed in 293T cells stably expressing Flag-STN1 and Flag-TEN1. Cell lysates were isolated and mixed with cell lysates containing equal quantities of Myc-Polα. This mixture was immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag antibody. Anti-Myc and anti-Flag antibodies were used for immunodetection. C: C-terminal truncation mutant. (C) Expression of WT or mutant CTC1 and detection of endogenous STN1 levels in CTC1−/− MEFs stably expressing Polα. Anti-STN1 antibody was used to detect endogenous STN1 levels, and anti-Myc, for Polα levels. γ-tubulin served as loading control. Quantifications of endogenous STN1 and Myc-Polα expression levels relative to γ-tubulin are indicted, with cells expressing WT CTC1 set at 1.0.

Discussion

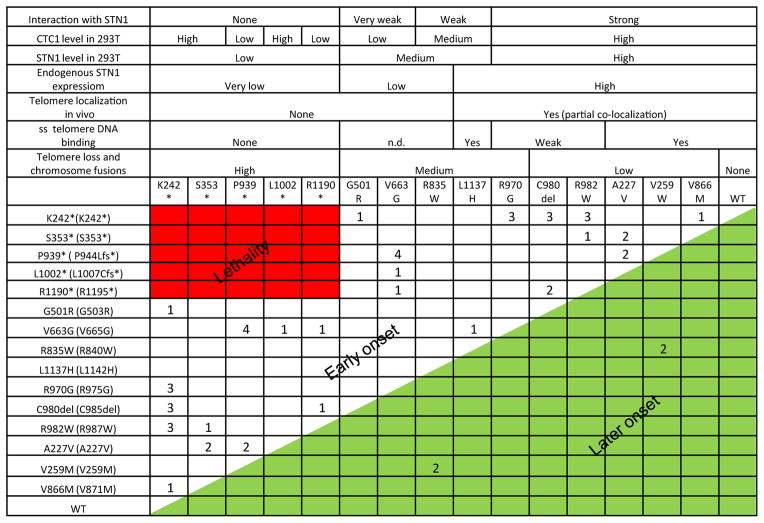

In this report, we present the first comprehensive characterization of the compound heterozygous CTC1 mutations inherited in patients with Coats plus syndrome. By generating corresponding human CTC1 mutations in the mouse CTC1 protein and expressing these mutants in CTC1−/− MEFs, we were able to perform in vivo biochemical experiments without the presence of endogenous CTC1 to complicate data interpretation. All CTC1 frameshift mutations examined in this report either generated truncated protein products or were expressed at low levels. Most of these frameshift mutants were unable to form a complex with STN1–TEN1 to localize to ss telomeric DNA or to telomeres in vivo (Fig. 1) (the exception being CTC1L1002*, which can form a weak CST complex on ss telomeric DNA, but not on telomeres in vivo). In addition, expression of truncated mutants, including CTC1K242* and CTC1S353*, was able to repress endogenous STN1 expression to prevent CST complex formation on telomeres, resulting in telomere dysfunction, increased G-overhang formation, chromosome fusions, and decreased DNA Polα binding to STN1 (Figs 3 and 5). Interestingly, analysis of co-expressed heterozygous mutants revealed that several truncated CTC1 proteins, including CTC1K242*, were also able to function as dominant negatives to repress the expression of their missense CTC1 counterparts (Fig. 4). Inheritance of the CTC1K242* mutation with any missense allele is thus predicted to result in the manifestation of severe disease phenotypes (Fig. 6). This notion is substantiated by clinical data, which reveal that patients inheriting the CTC1K242* mutation experience very early disease onset, with several patients displaying severe telomere shortening (Anderson et al., 2012; Keller et al., 2012; Polvi et al., 2012; Walne et al., 2012). Our results also reveal why no patients inheriting two frameshift mutations have been observed – this likely would result in early lethality (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Summary of CTC1 mutations. The biochemical characteristics of the CTC1 mutations analyzed in this report are summarized. The first row describes the mouse mutations analyzed, and in the first column, mouse mutations are listed to the left of the corresponding human mutations (in parenthesis). Numbers correspond to the number of patients found to possess these compound mutations (Anderson et al., 2012; Keller et al., 2012; Polvi et al., 2012; Walne et al., 2012). Inheriting compound mutations indicated in red is predicted to result in early lethality, while inheriting mutations denoted in green is predicted to result in delayed onset of disease phenotypes.

We found that most of the missense CTC1 mutations examined behaved like their WT counterpart – most of them expressed at high levels and interacted with STN1–TEN1 to form a CST complex at telomeres. This result likely explains why compound heterozygous patients survive, because our mouse knockout studies revealed that only one functional CTC1 allele is required for survival (Gu et al., 2012). The three exceptions are mutants CTC1G501R, CTC1V663G, and CTC1R835W. All three mutated proteins expressed at low levels and cannot form a complex with STN1–TEN1 to localize to telomeres. In particular, Co-IP experiments revealed that CTC1G501R and CTC1V663G also interacted very poorly with STN1. Previous reports suggest that the C-terminus of CTC1 is required for STN1 interaction (Miyake et al., 2009; Chen et al., 2013). Our results support these findings, confirming that CTC1 C-terminal deletion mutants CTC1L1002* and CTC1R1190* were unstable, likely due to their inability to interact with STN1. However, the CTC1G501R and CTC1V663G mutations also uncovered a novel additional region of CTC1 that is also required for STN1 interaction. While sequence conservation is low between CTC1 and its putative yeast ortholog Cdc13, it is intriguing to note that residues G501R and V663G in CTC1 fall within a corresponding region of Cdc13 recently documented to be involved in homodimerization and STN1 binding (Mason et al., 2013). It is therefore tempting to speculate that the domain between amino acids 500–663 of CTC1 cooperates with its C-terminus for STN1 binding.

Our finding that STN1 is able to interact with DNA Polα (Fig. 5), and that CTC1 levels impact upon STN1 stability, suggests that the CST complex could both recruit Polα to telomeres and modulate its activity to facilitate efficient restart of stalled replication forks and to promote C-strand fill-in reactions (Gu et al., 2012; Huang et al., 2012; Stewart et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2012). The observation that CTC1 mutants negatively impact upon STN1 stability favors a scenario in which mutant CTC1 disrupts STN1 interaction with Polα, resulting in insufficient accumulation of Polα at telomeres, leading to progressive telomere attrition and onset of chromosome fusions. Our data also suggest why inactivating human mutations in STN1 have not yet been discovered – we predict that any mutations in STN1 that perturbs its interaction with Polα will likely be incompatible for survival.

Experimental procedures

Plasmids and antibodies

Expression vectors used were retrovirus expression vector pQCXIP from Clontech. Anti-Flag and anti-HA (mouse) antibodies are from Sigma, and anti-HA (rabbit) antibody is from Santa Cruz. Anti-Stn1 (rabbit) was generated as previously described (Gu et al., 2012). Mouse DNA polymerase alpha cDNA was obtained from Drs. Takeshi Mizuno and Fumio Hanaoka (Nakamura et al., 2005).

Reconstitution of CTC1−/− MEFs with CTC1 mutants

Murine CTC1 point mutants were generated by site-directed mutagenesis (Stratagene, Santa Clara, CA, USA) corresponding to clinically described human CTC1 mutants and confirmed by Sanger sequencing. CTC1−/− MEFs were infected with retrovirus expressing either WT or mutant CTC1 constructs and selected by puromycin. To achieve dual expression of compound heterozygous CTC1 mutants, CTC1 null MEFs stably expressing frameshift mutants were first selected with puromycin and then reinfected with WT or missense CTC1 mutants. RT–PCR and Western blotting were performed to confirm robust expressions of both alleles.

DNA-binding and Co-IP assays

Streptavidin-sepharose beads (Invitrogen, Grand island, NY, USA) coated with Biotin-Tel-C (CCCTAA)6 or Biotin-Tel-G (TTAGGG)6 were used for the ssDNA-binding assay. Protein A/G-sepharose beads (GE Healthcare, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) were used for Co-IP. Both beads were incubated with crude cell lysates in TEB150 buffer (50 mM Hepes pH 7.3, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 5 mM EGTA, 0.5% Triton X-100, 10% Glycerol, proteinase inhibitors) overnight at 4 °C. After washing with the same buffer, the proteins bound on beads were eluted and analyzed by immunoblotting.

PNA-FISH on metaphase chromosomes and telomere immuno-FISH assays

Cells were treated with 0.5 μg mL−1 of Colcemid for 4 h before harvest. Trypsinized cells were treated with 0.06 M KCl, fixed with methanol/acetic acid (3:1), and spread on glass slides. Metaphase spreads were hybridized with 5′-Tam-OO-(CCCTAA)4-3′ probe. For telomere immuno-FISH, cells were first seeded in eight-well chambers and immunostained with primary antibodies and FITC secondary antibodies and then hybridized with the peptide nucleic acid 5′-Cy3-OO-(CCCTAA)4-3′ probe to detect proteins localized to telomeres.

TRF Southern blotting

The 20 μg total genomic DNA was separated by pulse-field gel electrophoresis (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The gels were dried at 50 °C and prehybridized at 58 °C in Church mix (0.5 M NaH2PO4, pH 7.2, 7% SDS) and hybridized with γ-32P-(CCCTAA)4 oligonucleotide probes at 58 °C overnight. Gels were washed with 4XSSC and 0.1% SDS buffer at 55 °C and exposed to Phosphorimager screens. After in-gel hybridization for the G-overhang under native conditions, gels were denatured with 0.5 N NaOH and 1.5 M NaCl solution and neutralized with 3 M NaCl and 0.5 M Tris–HCl, pH 7.0, and then reprobed with (TTAGGG)4 oligonucleotide probes to detect total telomere DNA. To determine the relative G-overhang signals, the signal intensity for each lane was scanned with TYPHOON (GE) and quantified by IMAGEQUANT (GE) before and after denaturation. The G-overhang signal was normalized to the total telomeric DNA and compared between samples.

Supplementary Material

Fig. S1 RT-PCR analysis of Flag-tagged WT and mutant CTC1 expression (top) and endogenous STN1 expression (bottom) in reconstituted CTC1−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts.

Fig. S2 Stabilization of CTC1, STN1 and TEN1 requires CST complex formation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Branden Wu and Jin-na Min for technical help. We thank Drs. Takeshi Mizuno and Fumio Hanaoka (RIKEN, Japan) for the Polymerase alpha cDNA construct. This work was supported by the NIA (R21 AG043747) to Sandy Chang.

Footnotes

Author contributions

Peili Gu and Sandy Chang designed the experiments, and Peili Gu performed all the experiments. Peili Gu and Sandy Chang wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher’s web-site.

References

- Allsopp RC, Morin GB, Horner JW, DePinho R, Harley CB, Weissman IL. Effect of TERT over-expression on the long-term transplantation capacity of hematopoietic stem cells. Nat Med. 2003;9:369–371. doi: 10.1038/nm0403-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson BH, Kasher PR, Mayer J, Szynkiewicz M, Rice GI, Crow YJ. Mutations in CTC1, encoding conserved telomere maintenance component 1, cause Coats plus. Nat Genet. 2012;44:338–342. doi: 10.1038/ng.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armanios M. An emerging role for the conserved telomere component 1 (CTC1) in human genetic disease. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;59:209–210. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodnar AG, Ouellette M, Frolkis M, Holt SE, Chiu CP, Morin GB, Harley CB, Shay JW, Lichtsteiner S, Wright WE. Extension of life-span by introduction of telomerase into normal human cells. Science. 1997;279:349–352. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5349.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calado RT, Young NS. Telomere maintenance and human bone marrow failure. Blood. 2008;111:4446–4455. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-019729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calado RT, Young NS. Telomere diseases. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2353–2365. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0903373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casteel DE, Zhuang S, Zeng Y, Perrino FW, Boss GR, Goulian M, Pilz RB. A DNA polymerase-alpha·primase cofactor with homology to replication protein A-32 regulates DNA replication in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:5807–5818. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807593200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan SS, Chang S. Defending the end zone: studying the players involved in protecting chromosome ends. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:3773–3778. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra A, Hughes TR, Nugent CI, Lundblad V. Cdc13 both positively and negatively regulates telomere replication. Genes Dev. 2001;15:404–414. doi: 10.1101/gad.861001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen LY, Redon S, Lingner J. The human CST complex is a terminator of telomerase activity. Nature. 2013;488:540–544. doi: 10.1038/nature11269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denchi EL, de Lange T. Protection of telomeres through independent control of ATM and ATR by TRF2 and POT1. Nature. 2007;448:1068–1071. doi: 10.1038/nature06065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dokal I. Dyskeratosis congenita. A disease of premature ageings. Lancet. 2001;358 (Suppl):S27. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)07040-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn RL, Zou L. Oligonucleotide/oligosaccharide-binding fold proteins: a growing family of genome guardians. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;45:266–275. doi: 10.3109/10409238.2010.488216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goulian M, Heard CJ. The mechanism of action of an accessory protein for DNA polymerase alpha/primase. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:13231–13239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goulian M, Heard CJ, Grimm SL. Purification and properties of an accessory protein for DNA polymerase alpha/primase. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:13221–13230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greider CW. Telomere length regulation. Annu Rev Biochem. 1996;65:337–365. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.002005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu P, Min JN, Wang Y, Huang C, Peng T, Chai W, Chang S. CTC1 deletion results in defective telomere replication, leading to catastrophic telomere loss and stem cell exhaustion. EMBO J. 2012;31:2309–2321. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X, Deng Y, Lin Y, Cosme-Blanco W, Chan S, He H, Yuan G, Brown EJ, Chang S. Dysfunctional telomeres activate an ATM-ATR-dependent DNA damage response to suppress tumorigenesis. EMBO J. 2007;26:4709–4719. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He H, Multani AS, Cosme-Blanco W, Tahara H, Ma J, Pathak S, Deng Y, Chang S. POT1b protects telomeres from end-to-end chromosomal fusions and aberrant homologous recombination. EMBO J. 2006;25:5180–5190. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He H, Wang Y, Guo X, Ramchandani S, Ma J, Shen MF, Garcia DA, Deng Y, Multani AS, You MJ, Chang S. Pot1b deletion and telomerase haploin-sufficiency in mice initiate an ATR- dependent DNA damage response and elicit phenotypes resembling dyskeratosis congenita. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:229–240. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01400-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hills M, Lansdorp PM. Short telomeres resulting from heritable mutations in the telomerase reverse transcriptase gene predispose for a variety of malignancies. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1176:178–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hockemeyer D, Daniels JP, Takai H, de Lange T. Recent expansion of the telomeric complex in rodents: two distinct POT1 proteins protect mouse telomeres. Cell. 2006;126:63–77. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C, Dai X, Chai W. Human Stn1 protects telomere integrity by promoting efficient lagging-strand synthesis at telomeres and mediating C-strand fill-in. Cell Res. 2012;22:1681–1695. doi: 10.1038/cr.2012.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller RB, Gagne KE, Usmani GN, Asdourian GK, Williams DA, Hofmann I, Agarwal S. CTC1 Mutations in a patient with dyskeratosis congenita. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;59:311–314. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Makovets S, Matsuguchi T, Blethrow JD, Shokat KM, Blackburn EH. Cdk1-dependent phosphorylation of Cdc13 coordinates telomere elongation during cell-cycle progression. Cell. 2009;136:50–61. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason M, Wanat JJ, Harper S, Schultz DC, Speicher DW, Johnson FB, Skordalakes E. Cdc13 OB2 dimerization required for productive Stn1 binding and efficient telomere maintenance. Structure. 2013;21:109–120. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JR, Wood E, Collins K. A telomerase component is defective in the human disease dyskeratosis congenita. Nature. 1999;402:551–555. doi: 10.1038/990141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyake Y, Nakamura M, Nabetani A, Shimamura S, Tamura M, Yonehara S, Saito M, Ishikawa F. RPA-like mammalian Ctc1–Stn1–Ten1 complex binds to single-stranded DNA and protects telomeres independently of the Pot1 pathway. Mol Cell. 2009;36:193–206. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura M, Nabetani A, Mizuno T, Hanaoka F, Ishikawa F. Alterations of DNA and chromatin structures at telomeres and genetic instability in mouse cells defective in DNA polymerase alpha. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:11073–11088. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.24.11073-11088.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palm W, de Lange T. How shelterin protects mammalian telomeres. Annu Rev Genet. 2008;42:301–334. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.41.110306.130350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polvi A, Linnankivi T, Kivela T, Herva R, Keating JP, Makitie O, Pareyson D, Vainionpaa L, Lahtinen J, Hovatta I, Pihko H, Lehesjoki AE. Mutations in CTC1, encoding the CTS telomere maintenance complex component 1, cause cerebroretinal microangiopathy with calcifications and cysts. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90:540–549. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage SA. Connecting complex disorders through biology. Nat Genet. 2012;44:238–240. doi: 10.1038/ng.2206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage SA, Giri N, Baerlocher GM, Orr N, Lansdorp PM, Alter BP. TINF2, a component of the shelterin telomere protection complex, is mutated in dyskeratosis congenita. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:501–509. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shtessel L, Ahmed S. Telomere dysfunction in human bone marrow failure syndromes. Nucleus. 2011;2:24–29. doi: 10.4161/nucl.2.1.13993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart JA, Wang F, Chaiken MF, Kasbek C, Chastain PD, 2nd, Wright WE, Price CM. Human CST promotes telomere duplex replication and general replication restart after fork stalling. EMBO J. 2012;31:3537–3549. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surovtseva YV, Churikov D, Boltz KA, Song X, Lamb JC, Warrington R, Leehy K, Heacock M, Price CM, Shippen DE. Conserved telomere maintenance component 1 interacts with STN1 and maintains chromosome ends in higher eukaryotes. Mol Cell. 2009;36:207–218. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vulliamy T, Marrone A, Goldman F, Dearlove A, Bessler M, Mason PJ, Dokal I. The RNA component of telomerase is mutated in autosomal dominant dyskeratosis congenita. Nature. 2001;413:432–435. doi: 10.1038/35096585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vulliamy T, Marrone A, Szydlo R, Walne A, Mason PJ, Dokal I. Disease anticipation is associated with progressive telomere shortening in families with dyskeratosis congenita due to mutations in TERC. Nat Genet. 2004;36:447–449. doi: 10.1038/ng1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walne AJ, Vulliamy T, Beswick R, Kirwan M, Dokal I. TINF2 mutations result in very short telomeres: analysis of a large cohort of patients with dyskeratosis congenita and related bone marrow failure syndromes. Blood. 2008;112:3594–3600. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-153445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walne AJ, Bhagat T, Kirwan M, Gitiaux C, Desguerre I, Leonard N, Nogales E, Vulliamy T, Dokal IS. Mutations in the telomere capping complex in bone marrow failure and related syndromes. Haematologica. 2012;98:334–338. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2012.071068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F, Stewart JA, Kasbek C, Zhao Y, Wright WE, Price CM. Human CST has independent functions during telomere duplex replication and C-strand fill-in. Cell Rep. 2012;2:1096–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinrich SL, Pruzan R, Ma L, Ouellette M, Tesmer VM, Holt SE, Bodnar AG, Lichtsteiner S, Kim NW, Trager JB, Taylor RD, Carlos R, Andrews WH, Wright WE, Shay JW, Harley CB, Morin GB. Reconstitution of human telomerase with the template RNA component hTR and the catalytic protein subunit hTRT. Nat Genet. 1997;17:498–502. doi: 10.1038/ng1297-498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L, Multani AS, He H, Cosme-Blanco W, Deng Y, Deng JM, Bachilo O, Pathak S, Tahara H, Bailey SM, Behringer RR, Chang S. Pot1 deficiency initiates DNA damage checkpoint activation and aberrant homologous recombination at telomeres. Cell. 2006;126:49–62. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu P, Takai H, de Lange T. Telomeric 3′ overhangs derive from resection by Exo1 and Apollo and fill-in by POT1b-associated CST. Cell. 2012;150:39–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young NS. Telomere biology and telomere diseases: implications for practice and research. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2010;2010:30–35. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2010.1.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1 RT-PCR analysis of Flag-tagged WT and mutant CTC1 expression (top) and endogenous STN1 expression (bottom) in reconstituted CTC1−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts.

Fig. S2 Stabilization of CTC1, STN1 and TEN1 requires CST complex formation.