Abstract

Aims: Chronic cerebral hypoperfusion (CCH) is a common pathological factor that contributes to neurodegenerative diseases such as vascular dementia (VaD). Although oxidative stress has been strongly implicated in the pathogenesis of VaD, the molecular mechanism underlying the selective vulnerability of hippocampal neurons to oxidative damage remains unknown. We assessed whether the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase (Nox) complex, a specialized superoxide generation system, plays a role in VaD by permanent ligation of bilateral common carotid arteries in rats. Results: Male Wistar rats (10 weeks of age) were subjected to bilateral occlusion of the common carotid arteries (two-vessel occlusion [2VO]). Nox1 expression gradually increased in hippocampal neurons, starting at 1 week after 2VO and for approximately 15 weeks after 2VO. The levels of superoxide, DNA oxidation, and neuronal death in the CA1 subfield of the hippocampus, as well as consequential cognitive impairment, were increased in 2VO rats. Both inhibition of Nox by apocynin, a putative Nox inhibitor, and adeno-associated virus-mediated Nox1 knockdown significantly reduced 2VO-induced reactive oxygen species generation, oxidative DNA damage, hippocampal neuronal degeneration, and cognitive impairment. Innovation and Conclusion: We provided evidence that neuronal Nox1 is activated in the hippocampus under CCH, causing oxidative stress and consequential hippocampal neuronal death and cognitive impairment. This evidence implies that Nox1-mediated oxidative stress plays an important role in neuronal cell death and cognitive dysfunction in VaD. Nox1 may serve as a potential therapeutic target for VaD. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 21, 533–550.

Introduction

Vascular dementia (VaD) is one of the most common cognitive disorders in the elderly, after Alzheimer's disease (AD). VaD is caused by a range of cardiovascular or cerebrovascular conditions, leading to ischemic, hypoperfusive, or hemorrhagic brain lesions that are characterized by loss of cognitive functions (2, 27, 33, 59). Chronic cerebral hypoperfusion (CCH) is strongly related to progressive cognitive decline (23, 46). The effect of CCH is not restricted to VaD; it is also one of the early components of AD pathogenesis (56). However, the mechanisms underlying the cognitive deficit caused by CCH in VaD remain elusive.

Innovation.

In the present study, we have demonstrated that neuronal nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase 1 (Nox1) was activated in the hippocampus under chronic cerebral hypoperfusion (CCH), causing oxidative stress and consequential hippocampal neuronal death and cognitive impairment. Adeno-associated virus serotype 2 (AAV2)-mediated targeting of Nox1 provided protection against hippocampal neuronal death and cognitive impairment induced by CCH in rats. Nox1 may serve as a novel molecular target for therapeutic intervention in vascular dementia.

Since the establishment of two-vessel occlusion (2VO), which is the permanent bilateral occlusion of the common carotid artery, in rats as an animal model to reproduce CCH (51, 52), this model has been widely used to study the molecular mechanisms underlying the cognitive impairment, white matter lesions, and neuronal damage observed in CCH, as well as in therapeutic intervention studies (16, 34, 35, 65). Generation and accumulation of amyloid and injury to white matter integrity and glial activation, which result in cognitive impairment, have also been observed in the 2VO rat model (29). We previously reported that memory impairment is exacerbated through the interaction between CCH and amyloid toxicity in a 2VO rat model (16). In that previous study, we found that cerebral blood flow and cerebral metabolism in the cortex of 2VO rats were decreased to 74.5% and 80.3% at 8 weeks after 2VO operation, respectively (16).

Oxidative stress is considered a major contributing factor in the pathogenesis of VaD and AD (8, 48). Increased oxidative stress in the brain parenchyma, as manifested by protein oxidation, lipid peroxidation, and oxidative DNA damage, is a major characteristic feature of both AD and VaD (8, 30). Oxidative stress is important in the development of cognitive impairment that is caused by vascular hypoperfusion-induced pathology (3, 47). The activity of antioxidant enzymes, such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), glutathione peroxidase (GPx), glutathione reductase (GR), and heme oxygenase/biliverdin reductase, is decreased in patients with AD (4–6, 24) and VaD (14, 47). Reduced antioxidant enzyme levels in blood samples from VaD patients have also been reported (28, 64). Increasing evidence suggests that the family of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidases (Noxs), which are the enzyme complexes that transport electrons across the membrane and generate superoxide, plays a major role in generating reactive oxygen species (ROS) in various types of tissue (7). NADPH oxidase (Nox2) was originally identified in phagocytes (60) and is responsible for killing bacteria through the release of substantial quantities of superoxide into the phagosomes. Seven homologues, including Nox1, Nox2, Nox3, Nox4, Nox5, Duox1, and Duox2, have been identified in various tissues, including the central nervous system (CNS) (15, 22, 26).

Recent studies have demonstrated that Nox activity and expression are significantly elevated in the temporal gyri in patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) (12) and in mice with CCH (25). NOXs play an important role in inflammatory neuronal loss during the development of AD (9, 76). The involvement of the Nox family in neuronal death was demonstrated under various conditions, such as exposure to zinc (37, 54), growth-factor deprivation (70), hypoglycemia (21, 67, 77), and N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) activation (11). It has also been shown that the p47phox subunit is responsible for the generation of oxidants and neuronal death after stroke (68). Inhibition of Nox4 has been shown to prevent stroke-induced oxidative stress and neurodegeneration (45).

Several studies have focused on the role of the Nox family and Nox2 in CNS diseases, whereas Nox1, which is an inducible enzyme that belongs to the Nox family, has not been widely studied in these diseases.

Recent studies have reported that Nox1 participates in the ROS-dependent death of non-neuronal cells (13, 38, 41) and dopaminergic neurons (17, 20). Therefore, in the present work, we used an established rat model of VaD to investigate the role of Nox1 in the cognitive impairment that results from CCH, to test our hypothesis that Nox1-mediated ROS generation and consequential neuronal loss in the hippocampus are responsible for cognitive impairment. In this study, we obtained the first evidence that hippocampal Nox1 plays a pivotal role in the development of the brain damage and cognitive impairment induced by CCH.

Results

Increased ROS generation and neuronal death in the hippocampus of 2VO-operated rats

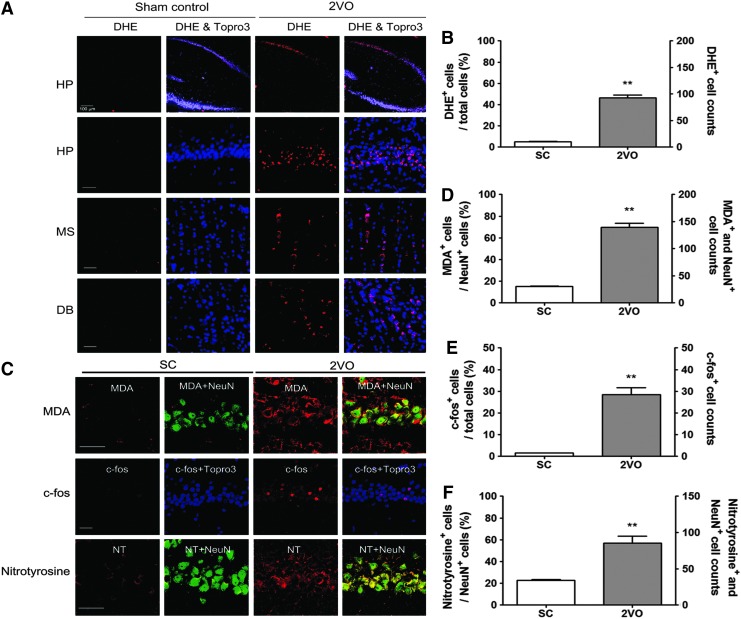

To determine whether superoxide is generated in the rat brain after 2VO operation, in situ visualization of superoxide and its derivative oxidant products was performed using hydroethidine histochemistry. ROS levels were increased in both the hippocampal CA1 region and the basal forebrain (medial septal nucleus and diagonal band) at 10 weeks after 2VO operation (Fig. 1A, B).

FIG. 1.

Increased superoxide generation in the hippocampus (HP) of 2VO-operated rats. (A) Representative fluorescence micrographs of superoxide production as visualized by ethidium fluorescence (red) in the HP and the medial septal nucleus (MS), and diagonal band (DB) at 10 weeks post-2VO operation. Scale bars=30 μm. (B) Changes in the % DHE (red) stained neurons of total cells and the number of DHE-stained neurons of Topro3 (nuclear marker, blue)-stained cells in the hippocampal CA1 subfield after sham- and 2VO operation in rats (n=4 per group, Error bars indicate SE). **p<0.01 versus Sham-operated rats. (C) Representative images of tissue sections immunostained with MDA, c-fos, or nitrotyrosine from rat hippocampal CA1 taken from sham-operated group (Sham control, n=4) and 2VO group (n=4) at 10 weeks after operation. (D) Changes in the % MDA (red)-stained neurons of NeuN (green)-stained cells and the number of MDA and NeuN-stained neurons in the hippocampal CA1 subfield after sham- and 2VO operation in rats (n=4 per group, Error bars indicate SE). MDA expression in NeuN+ neurons is demonstrated as yellow staining after merging green (NeuN) and red (DHE) images. **p<0.01 versus Sham-operated rats. (E) Changes in the % c-fos (red)-stained neurons of Topro3 (blue) stained cells and the number of c-fos-stained neurons of total neurons in the hippocampal CA1 subfield after sham- and 2VO operation in rats (n=4 per group, Error bars indicate SE). **p<0.01 versus Sham-operated rats. (F) Changes in the % nitrotyrosine (red)-stained neurons of NeuN (green)-stained cells and the number of nitrotyrosine and NeuN-stained neurons in the hippocampal CA1 subfield after sham- and 2VO operation in rats (n=4 per group, Error bars indicate SE). **p<0.01 versus sham-operated rats. Nitrotyrosine expression in NeuN+ neurons is demonstrated as yellow staining after merging green (NeuN) and red (DHE) images. Scale bars=30 μm. 2VO, two-vessel occlusion; DHE, dihydroethidium; MDA, malondialdehyde; NT, nitrotyrosine To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

As depicted in Figure 1C, an increase in malondialdehyde (MDA) immunoreactivity, which is a well-established marker of lipid peroxidation, was also found in the hippocampal CA1 subfield of rats treated with 2VO operation compared with rats treated with sham operation. To endorse the involvement of oxidative stress in 2VO operation, we assessed the expression of redox modification markers, such as the c-fos transcription factor and nitrotyrosine levels. As depicted in Figure 1C, increases in c-fos and nitrotyrosine immunoreactivity were found in the hippocampal CA1 subfield of rats treated with 2VO operation compared with rats treated with sham operation.

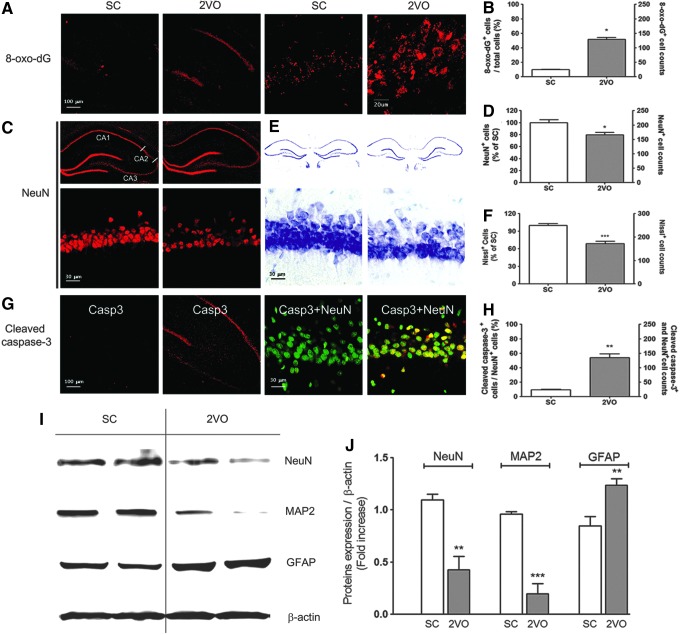

Oxidative DNA damage, as determined by increased 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-oxo-dG) immunoreactivity, was increased in the hippocampal CA1 subfield after 2VO operation (Fig. 2A, B). Moreover, choline acetyl-transferase (ChAT) immunoreactivity in cholinergic neurons was decreased in the medial septal nucleus and in the vertical diagonal bands of the basal forebrain at 10 weeks after 2VO operation (Supplementary Fig. S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/ars). Hippocampal neuronal death was determined by NeuN immunostaining, Nissl staining, and cleaved caspase-3 immunostaining in tissue sections from the hippocampus obtained at 10 weeks after sham or 2VO operation. Ten weeks after 2VO operation, the number of NeuN+- and Nissl-stained cells was decreased by 21.5%±4.11% (p<0.05 vs. sham control) and 31.2%±4.05% (p<0.05 vs. sham control), respectively, in the CA1 region of 2VO-operated rats (Fig. 2C–F). The number of cleaved caspase-3-stained cells was increased in the CA1 region of 2VO-operated rats (Fig. 2G, H).

FIG. 2.

Increased neuronal death in the hippocampus of 2VO-operated rats. (A) Representative fluorescence micrographs of DNA oxidation as visualized by 8-oxo-dG immunoreactivity (red) in the hippocampus (HP) at 10 weeks post-2VO operation. (B) Changes in the % by 8-oxo-dG (red)-stained neurons in the hippocampal CA1 subfield after sham- and 2VO operation in rats (n=4 per group, Error bars indicate SE). *p<0.05 versus Sham-operated rats. Representative images of tissue sections immunostained with NeuN (C), stained with Cresyl violet (E), and immunostained with cleaved caspase-3 (G) from rat hippocampal CA1 taken from sham-operated group (Sham control, n=4) and 2VO group (n=4) at 10 weeks after operation. (D) Changes in the % NeuN (red)-stained neurons of sham control and the number of NeuN (red)-stained neurons in the hippocampal CA1 subfield after sham- and 2VO operation in rats (n=4 per group, Error bars indicate SE). *p<0.05 versus sham-operated rats. (F) Changes in the % Cresyl violet-stained neurons of sham control and the number of Cresyl violet-stained neurons in the hippocampal CA1 subfield after sham- and 2VO operation in rats (n=4 per group, Error bars indicate SE). ***p<0.001 versus sham-operated rats. (H) Changes in the % cleaved caspase-3 (red)-stained neurons of NeuN (green)-stained cells and the number of cleaved caspase-3 and NeuN-stained neurons (yellow) in the hippocampal CA1 subfield after sham- and 2VO operation in rats (n=4 per group, Error bars indicate SE). **p<0.01 versus sham-operated rats. (I) Western blot analysis showing NeuN, MAP-2, and GFAP levels in the HP of the sham control (n=3) or 2VO group (n=3) at 10 weeks after operation. (J) The intensity of each band was densitometrically determined and normalized against β-actin. NeuN and MAP-2 levels were statistically decreased in 2VO-operated rats (n=3, **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001 vs. sham-operated rats). GFAP level significantly increased in 2VO-operated rats. 8-oxo-dG, 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine; GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

Proteins extracted from sham- or 2VO-operated total hippocampal tissue were subjected to Western blot analysis using anti-NeuN, anti-MAP-2, and anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) antibodies. The levels of expression of NeuN (p<0.01 vs. the sham control) and MAP-2 (p<0.001 vs. sham control) were significantly decreased in the hippocampus of 2VO rats (Fig. 2H, I). The level of GFAP was increased in the hippocampus at 10 weeks after 2VO operation (p<0.01 vs. the sham control), which implies that astrogliosis had occurred.

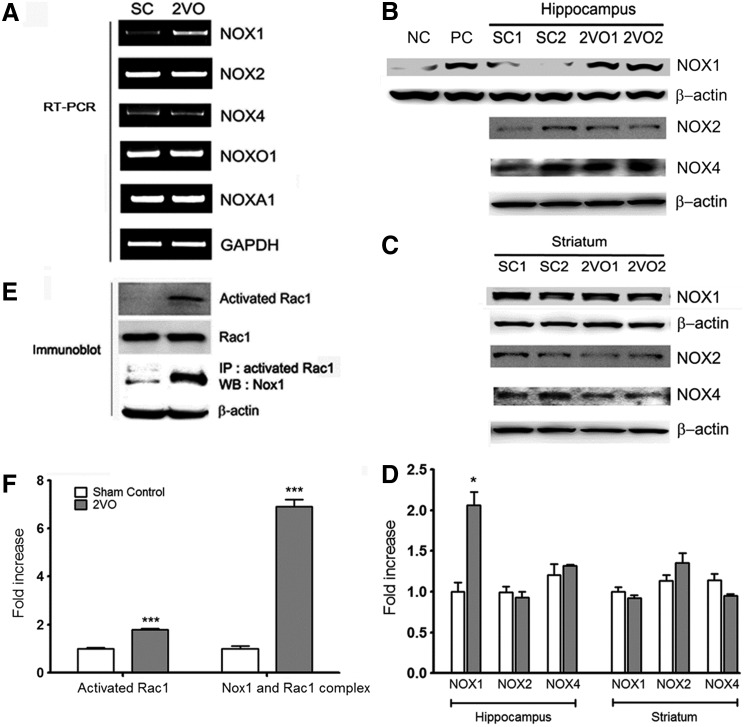

Increased expression of Nox1 and activation of Rac1 in the hippocampus of 2VO-operated rats

Next, we determined whether Nox-derived oxidative stress was responsible for neuronal degeneration under 2VO-induced CCH. Nox is a multisubunit enzyme that consists of catalytic subunits (Nox isoforms), regulatory subunits, and the small GTPase Rac1 (17). The mRNAs that encode each Nox isoform (Nox1, Nox2, and Nox4) and their regulatory subunits (NOX organizer 1 [Noxo1] and NOX activator 1 [Noxa1]) were identified using reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). Nox isoforms (Nox1, Nox2, and Nox4) and regulatory subunits (Noxo1 and Noxa1) were detected (Fig. 3A). Other variants were constitutively expressed, whereas Nox1 was induced robustly by chronic hypoperfusion that lasted for 2 weeks (Fig. 3A). Nox1 expression in the hippocampus and striatum was detected by Western blot analysis (Fig. 3B–D). Nox1 expression was increased in the hippocampus, whereas no increase was observed in the striatum at 2 weeks after 2VO operation (p<0.01 vs. the sham control). To confirm the results of the Nox1 immunoblotting analysis, total lysates of the SN tissues of rats injected with 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA) or vehicle were used as a positive or negative control, respectively (Fig. 3B). Both Nox2 and Nox4 were constitutively expressed in the hippocampus and striatum (Fig. 3B–D). The activation of the small GTPase Rac1 is indispensable for the activation of Nox1 and Nox2 (10). GTP-bound active Rac1 was observed at 2 weeks after 2VO operation in hippocampal tissue (p<0.001 vs. the sham control); moreover, Nox1 was coprecipitated with active Rac1 (p<0.001 vs. the sham control) (Fig. 3E, F), suggesting that CCH by 2VO activates the Nox1/Rac1 system in the hippocampus.

FIG. 3.

Increased expressions of Nox1 mRNA and Nox1 proteins and Rac1 activation in the hippocampus of 2VO-operated rats. (A) A representative PCR of Nox1 mRNA in hippocampus of 2VO-operated rats at 2 weeks after operation. (B, C) Representative photomicrographs of Western blot analysis showing Nox1, Nox2, and Nox4 levels in the hippocampus and striatum of rats 2 weeks after the rats were subjected to SC and 2VO operations. To verify Nox1 antibody specificity, total lysates of the SN tissues of rats injected with 6-OHDA or vehicle were used as a positive or negative control, respectively. NC, negative control; PC, positive control. (D) The intensity of each band was densitometrically determined and normalized against β-actin. Nox1 expression was significantly increased in hippocampus of 2VO-operated rats (n=3, *p<0.01 vs. Sham control). (E) The activated fraction of Rac1 was determined in the hippocampus of SC and 2VO-operated rats with the active GTPase pull-down assay. Rac1 levels were measured as an internal control. After GTPase pull-down, Nox1 was detected using Western blot analysis on the same blot to determine binding with activated Rac1 and Nox1. (F) The intensity of each band was densitometrically determined and normalized against Rac1 or β-actin. Rac1 activation and binding with activated Rac1 and Nox1 were significantly increased in hippocampus of 2VO-operated rats (n=3, ***p<0.001 vs. Sham control). 6-OHDA, 6-hydroxydopamine; NADPH, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate; Nox1, NADPH oxidase 1; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; SN, substantia nigra.

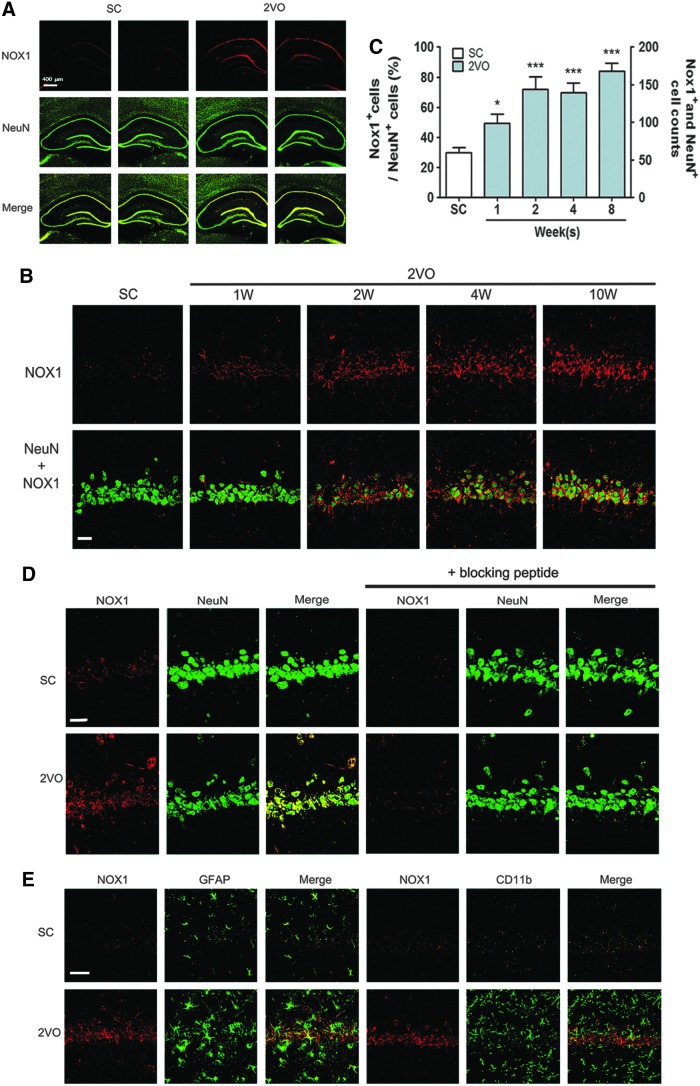

The immunohistochemical analysis revealed that Nox1 expression in the hippocampal CA1 was profoundly increased at 10 weeks after 2VO operation compared with that observed in sham-operated animals (Fig. 4A). Nox1 expression in the hippocampal CA1 subfield steadily increased from 1 week after 2VO operation (Fig. 4B, C). Nox1 immunostaining (red) was mostly colocalized with pyramidal neurons (NeuN), which were immunostained green in the hippocampal CA1 subfield (as identified by the yellow staining observed after merging the two images). To verify the Nox1 immunohistochemical analysis, we compared Nox1-stained hippocampal neurons at 10 weeks after the 2VO operation with the dopaminergic neurons of the SN tissues of rats injected with 6-OHDA, which was used as a specific positive control (17). Nox1 immunostaining (red) was increased in both hippocampal neurons (green) after 2VO operation and dopaminergic neurons (TH-positive neurons, green) exposed to 6-OHDA (Fig. 4D and Supplementary Fig. S2A). Nox1 immunostaining (red) was colocalized with dopaminergic neurons (TH-positive neurons), which were immunostained green in the SN (as identified by the yellow staining observed after merging the two images). Nox1 antibody specificity was evaluated by preincubation with a specific blocking peptide for 1 h. The preincubation of the Nox1 antibody with the blocking peptides led to a failure to detect Nox1 (red) in both hippocampal neurons after 2VO operation and TH-stained dopaminergic neurons in SN exposed to 6-OHDA (Fig. 4D and Supplementary Fig. S2A). These results suggest the hippocampal-neuron-specific expression of Nox1 (Fig. 4A–D). Neither astrocytes nor microglia expressed Nox1, which was demonstrated by coimmunostaining using NeuN and GFAP (astrocytes) or CD11b (microglia) (Fig. 4E). The levels of Nox2, Nox4, Noxa1, and Noxo1 expression were not altered after 2VO operation (Supplementary Fig. S2B, C). In these experiments, for the first time, we investigated Nox1 expression in hippocampal neurons after CCH.

FIG. 4.

Increased expression of neuronal Nox1 in the hippocampal tissues of 2VO-operated rats. (A, D) Representative photographs of tissue sections stained with Nox1 (Red) and NeuN (green) antibody from rat hippocampal CA1 taken from sham-operated group (SC, n=4) and 2VO (n=4)-operated rats at 10 weeks after the operation. Nox1 expression in NeuN+ neurons is demonstrated as yellow staining after merging green (NeuN) and red (Nox1) images. (B) Representative photographs of tissue sections stained with Nox1 (red) and NeuN (green) antibody from rat hippocampal CA1 taken from sham-operated group (SC, n=4) and 2VO (n=4)-operated rats at 1, 2, 4, and 10 weeks after the operation. Nox1 expression in NeuN+ neurons is demonstrated as yellow staining after merging green (NeuN) and red (Nox1) images. (C) Changes in the % Nox1 (red)-stained neurons of NeuN (green)-stained cells and the number of Nox1(red) and NeuN (green)-stained neurons (yellow) in the hippocampal CA1 subfield after sham- and 2VO operation in rats (n=4 per group, Error bars indicate SE). *p<0.05, ***p<0.001 versus sham-operated rats. (D) Representative photographs of disappearance of Nox1 staining (red) in hippocampal tissue sections after antibody absorption with blocking peptide. Nox1 antibody specificity was evaluated by preincubation with specific blocking peptide for 1 h. (E) Nox1 (red) expression was observed neither in astrocytes nor in microglia (n=4). GFAP (green) and CD11b (green) were stained as markers for astrocytes and microglia, respectively (n=4). Scale bars=30 μm. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

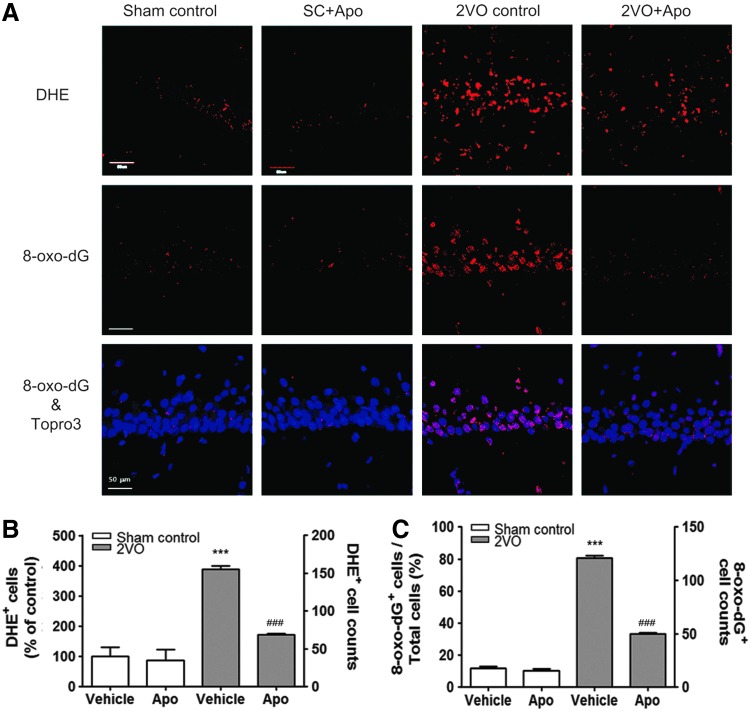

Apocynin reduced superoxide generation, DNA oxidation, and neuronal death in the hippocampus of 2VO-operated rats

To verify the role of Nox1-mediated oxidative stress in hippocampal neuronal death and cognitive impairment after CCH, a putative Nox inhibitor, apocynin, was tested. Either vehicle (1% DMSO in saline) or apocynin (10 mg/kg) was administered intraperitoneally every day for 8 weeks from the same day that the sham or 2VO operation was performed. Apocynin administration strongly reduced 2VO-elicited superoxide generation (p<0.001 vs. the sham control; Fig. 5A, B) and oxidative DNA damage, as determined by the observation of increased 8-oxo-dG immunoreactivity (p<0.001 vs. the sham control; Fig. 5A, C) in the hippocampus. This finding suggests that DNA oxidation is induced by the superoxide which was generated through Nox activation after 2VO operation.

FIG. 5.

Increased superoxide generation and DNA oxidation in hippocampal neurons of 2VO-operated rats attenuated by apocynin. (A) Representative fluorescence micrographs of superoxide production as visualized by ethidium fluorescence (DHE, red) and 8-oxo-dG immunoreactivity (red) at 10 weeks post-2VO operation. (B) Increased % DHE (red)-stained neurons of sham control and the number of DHE-stained neurons in 2VO-operated rats treated with vehicle were significantly decreased by apocynin treatment. (n=6, ***p<0.001 vs. sham-operated rats treated with vehicle, ###p<0.001 vs. 2VO-operated rats treated with vehicle). (C) Increased % of 8-oxo-dG (red)-stained neurons of Topro3 (blue)-stained cells and the number of 8-oxo-dG (red)-stained neurons in 2VO-operated rats treated with vehicle were significantly decreased by apocynin treatment. (n=6, ***p<0.001 vs. sham-operated rats treated with vehicle, ###p<0.001 vs. 2VO-operated rats treated with vehicle). Sham control, sham-operated rats treated with vehicle; SC+Apo, sham-operated rats treated with apocynin (10 mg/kg/day for 8 weeks); 2VO control, 2VO-operated rats treated with vehicle; 2VO+Apo, 2VO-operated rats treated with apocynin. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

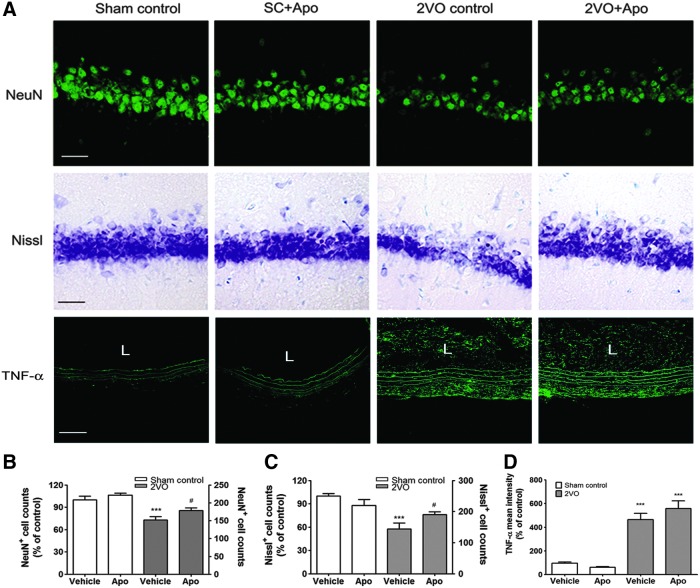

The increased neuronal loss observed in the hippocampal CA1 subfield of 2VO rats, as determined via NeuN immunostaining and Nissl staining, was significantly reduced by treatment with apocynin (Fig. 6). The decreased number of NeuN+ cells and Nissl-stained cells after 2VO operation recovered to 17.13%±5.46% (p<0.05) and 32.31%±5.21% (p<0.05) after treatment with apocynin (Fig. 6). In addition, to confirm the role of apocynin in the ligated common carotid artery, expression levels of proinflammatory cytokines at the ligation site were detected by real-time PCR and immunohistochemistry. Expressions of interleukin-1beta (IL-1β), Interleukin-6 (IL-6), and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) mRNA were increased in the ligated common carotid artery at 1 week and 4 weeks after 2VO operation (Supplementary Fig. S3). In the immunohistochemical analysis, expressions of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α were increased in the elastin fiber of the tunica media in the ligated common carotid artery (Fig. 6 and Supplementary Fig. S4). Especially, increased expression of TNF-α was also determined in the neointima at 4 weeks after 2VO operation (Fig. 6). However, apocynin administration has not changed increased expressions of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α in the ligated common carotid artery at 1 and 4 weeks after 2VO operation (Fig. 6 and Supplementary Figs. S3 and S4).

FIG. 6.

Hippocampal neuronal loss in 2VO-operated rats is attenuated by apocynin. (A) Representative photographs of tissue sections stained with the NeuN (green) antibody, Cresyl violet, or TNF-α (green) antibody from rat hippocampal CA1 and common carotid artery taken from the sham-operated group (Sham control, n=6) and 2VO group (n=6) with or without apocynin. Scale bars=30 μm (upper and middle panel), 50 μm (lower panel). (B, C) Decreased NeuN- and Nissl-positive cell counts in 2VO-operated rats treated with vehicle were significantly decreased by apocynin treatment. (n=6, ***p<0.001 vs. sham-operated rats treated with vehicle, #p<0.05 versus 2VO-operated rats treated with vehicle). (D) Increased mean intensity of TNF-α expression in neointima and tunica media of ligated common carotid artery was not decreased by apocynin treatment at 4 weeks after 2VO operation (n=6, ***p<0.001 vs. sham-operated rats treated with vehicle). Sham control, sham-operated rats treated with vehicle; SC+Apo, sham-operated rats treated with apocynin (10 mg/kg/day for 8 weeks); 2VO control, 2VO-operated rats treated with vehicle; 2VO+Apo, 2VO-operated rats treated with apocynin; L, lumen; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor alpha. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

These findings indicate that the activation of NOX is crucial for hippocampal ROS generation and for the neuronal loss observed after CCH but is not involved in conformational change and inflammation in the ligated common carotid artery.

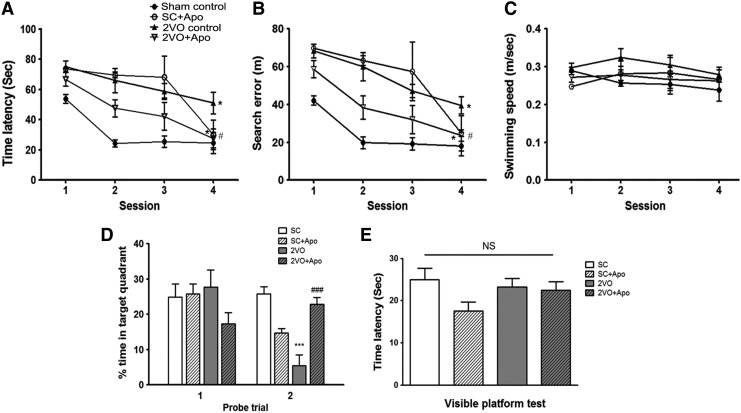

Apocynin reduced the memory impairment induced by CCH

To evaluate the effect of apocynin on the recovery of cognitive function after 2VO, spatial memory was evaluated by assessing learning and memory retention using the Morris water maze (MWM) test. In the acquisition trials, the sham-operated animals gradually learned the location of the hidden platform, which was evidenced by shorter latencies and fewer search errors throughout the test period. CCH induced by 2VO resulted in a significant impairment in spatial learning (time latencies, F(3,20)=22.19; search errors, F(3,20)=24.17) compared with sham-operated controls (repeated-measures two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), p<0.05; Fig. 7A, B). Apocynin-treated 2VO animals exhibited shorter mean session latencies and fewer search errors in locating the platform compared with the 2VO group (repeated-measures two-way ANOVA, p<0.05; Fig. 7A, B). These results suggest that, although abnormally overproduced superoxide induces impairment in spatial memory, normal Nox-mediated-superoxide production might be essential for learning and memory retention. To determine whether the group differences observed in escape latencies were due to differences in swimming, especially between the sham-operated group and the 2VO group, swimming speeds were calculated for each group. No differences in swimming speed were observed among the four groups (repeated-measures two-way ANOVA, F(3,20)=1.761; Fig. 7C). In the first probe trial, the time spent in the target quadrant was not different among the groups. However, in the second probe trial, the time spent in the target quadrant was different among the groups (F(3,29)=18.10). A post hoc analysis showed that the percentage of time spent in the target quadrant was significantly decreased in 2VO-operated rats (p<0.001) compared with sham-operated rats (Fig. 7D) and was significantly increased in apocynin-treated 2VO-operated rats (p<0.001) compared with 2VO-operated rats (Fig. 7D). The times required to reach the visible platform during the visible platform test were not different among the groups (F(3,20)=1.642; Fig. 7E).

FIG. 7.

Effect of apocynin on chronic cerebral hypoperfusion-induced Morris water maze (MWM) performance deficits in rats. Spatial memory evaluation using time latency (A), search error (B), swimming speed (C) % time in target quadrant (D), and (E) time latency in visible platform test. n=6/group, *p<0.05, ***p<0.001 versus Sham control, #p<0.05, ###p<0.001 versus 2VO control. Sham control, sham-operated rats treated with vehicle; SC+Apo, sham-operated rats treated with apocynin (10 mg/kg/day for 8 weeks); 2VO control, 2VO-operated rats treated with vehicle; 2VO+Apo, 2VO-operated rats treated with apocynin; NS, not significant.

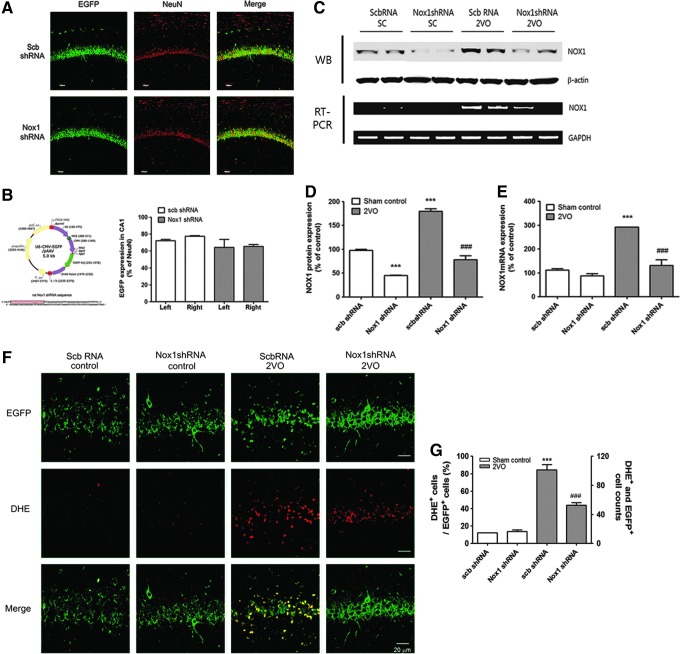

Inhibition of Nox1 reduced superoxide generation, DNA oxidation, and neuronal death in the hippocampus of 2VO-operated rats

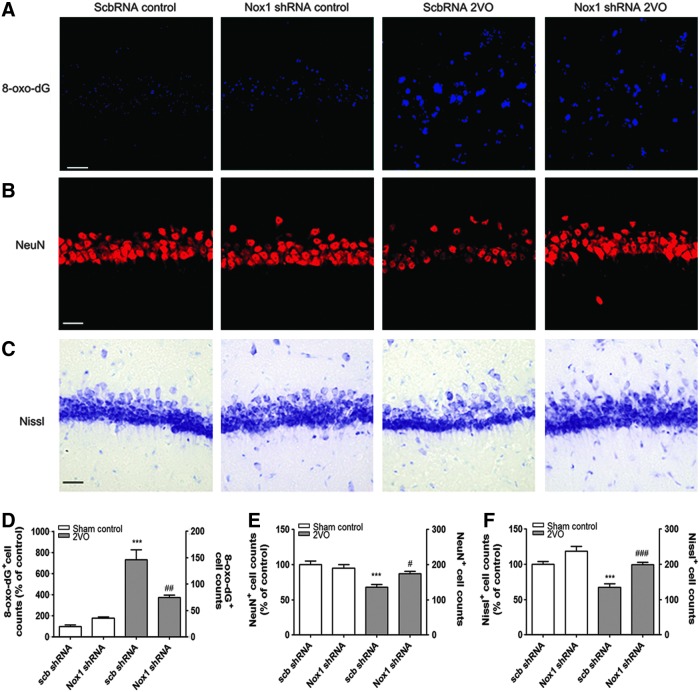

To achieve selective inhibition of Nox1, an adeno-associated virus 2 (AAV2) containing an shRNA targeting Nox1 was stereotaxically delivered into the hippocampal CA1 subfield (Fig. 8A). These vectors expressed enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) separately, as a marker of transduction efficiency. Due to the neuronal tropism of the AAV2, the shRNA construct was selectively transferred to neurons in the brain and efficiently knocked down Nox1 expression (17). 2VO operation was performed at 4 weeks after AAV2 injection; ∼60% of NeuN+ pyramidal neurons in the hippocampal CA1 subfield were transduced with AAV2 particles, as indicated by EGFP signal (Fig. 8A, B). Nox1 knockdown efficiency in the hippocampal CA1 subfield was verified by both Western blot analysis and RT-PCR performed at 12 weeks after AAV2 injection (Fig. 8C–E). A 4-week preinjection with Nox1 shRNA/AAV2 viral particles (EGFP-expressing cells) in the hippocampus CA1 area resulted in a significant reduction in superoxide generation (p<0.05 vs. scrambled shRNA and 2VO) caused by 2VO, as determined by dihydroethidium (DHE) histochemistry (Fig. 8F, G). Reductions in the intensity of 8-oxo-dG immunoreactivity (p<0.01 vs. scrambled shRNA and 2VO; Fig. 9A, D) and in the number of NeuN-immunostained cells (p<0.05 vs. scrambled shRNA and 2VO; Fig. 9B, E) and Nissl-stained neurons (p<0.001 vs. scrambled shRNA and 2VO) suggested a similar protective effect, indicating that selective inhibition of Nox1/Rac1 activation attenuates 2VO-elicited neuronal loss in the hippocampus (Fig. 9C, F). In parallel with the transduction rate of the Nox1 shRNA in the hippocampal CA1 subfield, 2VO-mediated ROS generation, DNA oxidation, and neuronal loss were decreased (Figs. 8F and 9A–C).

FIG. 8.

The transduction efficiency of scramble shRNA or Nox1 shRNA expression in hippocampal neurons and reduced superoxide generation by Nox1 knockdown in 2VO rats. (A) Representative photographs of tissue sections expressed EGFP (green) and stained with the NeuN (red) antibody from rat hippocampal CA1 taken from rats at 4 weeks after scramble shRNA/AAV2 or Nox1 shRNA/AAV2 injection. shRNA expression in NeuN+ neurons is demonstrated as yellow staining after merging green (EGFP) and red (NeuN) images. (B) Establishment of U6 promoter-based Nox1 shRNA/AAV vector. U6 promoter-driven shRNA expression system was established in AAV vector. EGFP expression is separately controlled by a CMV promoter as a marker for the transduction efficiency. Nox1 shRNA sequence was designed based on the siRNA sequence (boxed red nucleotides). EGFP expression levels were measured as % volume of EGFP expression in NeuN+ neurons in both hippocampal CA1 subfields. Left: left hemisphere of brain; Right: right hemisphere of brain. (C–E) Nox1 knockdown efficiency in the hippocampal CA1 subfield was verified by both Western blot analysis and RT-PCR performed at 12 weeks after AAV2 injection. n=4/group, ***p<0.001 versus Sham control with scramble RNA/AAV2, ###p<0.001 versus 2VO control with scramble RNA/AAV2. Scb, scramble (F) AAV particles containing scramble shRNA or Nox1 shRNA were stereotaxically injected into the rat hippocampal CA1 subfield. After 4 weeks of incubation, animals were subject to either sham or 2VO operation. Fifteen weeks later, hippocampal CA1 subfields were visualized with DHE (red) for superoxide detection (n=5/group). Cells expressing EGFP (green) represent AAV-transduced cells. shRNA expression in NeuN+ neurons is demonstrated as yellow staining after merging green (EGFP) and red (NeuN) images. (G) Increased % of DHE-stained cells in EGFP-expressed cells and the number of DHE- and EGFP-positive cells in 2VO-operated rats injected with scrambled shRNA were significantly decreased by Nox1 knockdown. (n=5, ***p<0.001 vs. Scb RNA control, ###p<0.001 vs. ScbRNA 2VO). Scb RNA control, Sham-operated rats injected with scramble shRNA AAV particles; Nox1 shRNA control, Sham-operated rats injected with Nox1 shRNA AAV particles; ScbRNA 2VO, 2VO-operated rats injected with scramble shRNA AAV particles; Nox1 shRNA 2VO, 2VO-operated rats injected with Nox1 shRNA AAV particles. Scale bar=20 μm. AAV2, adeno-associated virus serotype 2; EGFP, enhanced green fluorescent protein; RT-PCR, reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

FIG. 9.

Increased DNA oxidation and neuronal loss in the hippocampal neurons of 2VO-operated rats attenuated by Nox1 knockdown. Representative photographs of tissue sections stained with (A) 8-oxo-dG (blue), (B) NeuN (red) antibody, and (C) Cresyl violet from rat hippocampal CA1 taken from sham-operated group (Sham control) and 2VO group with scramble (scb) shRNA or Nox1 shRNA (n=5/group). (D) Increased DNA oxidation (8-oxo-dG-positive cells) was significantly decreased by Nox1 knockdown (n=5, ***p<0.001 vs. scb shRNA control; ##p<0.01 vs. scb shRNA 2VO). (E, F) Decreased NeuN- or Nissl-positive cell counts were statistically recovered by Nox1 knockdown (n=5, ***p<0.001 vs. sham control with scb shRNA; #p<0.05 and ###p<0.001 vs. 2VO with scb shRNA). Scb RNA control, Sham-operated rats injected with scramble shRNA AAV particles; Nox1 shRNA control, Sham-operated rats injected with Nox1 shRNA AAV particles; ScbRNA 2VO, 2VO-operated rats injected with scramble shRNA AAV particles; Nox1 shRNA 2VO, 2VO-operated rats injected with Nox1 shRNA AAV particles. Scale bar=20 μm. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

Inhibition of Nox1 reduced the memory impairment induced by CCH

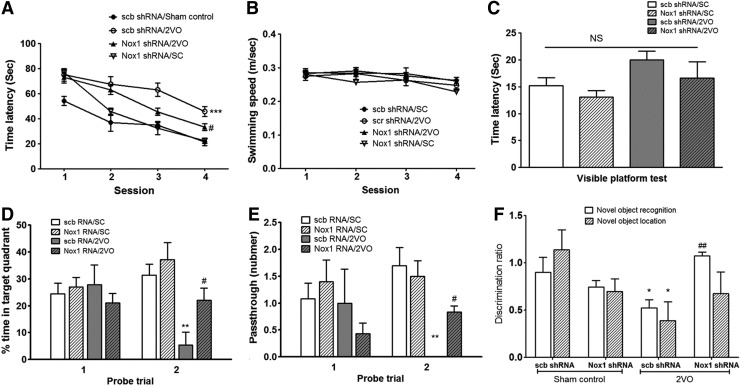

As shown in Figure 10, sham-operated control rats injected with scrambled shRNA quickly became proficient at locating the submerged platform during the training sessions; however, the 2VO rats injected with scrambled shRNA showed poor improvement over the course of training compared with the control rats. The decreased spatial memory observed in 2VO rats injected with scrambled shRNA was significantly recovered by the inhibition of Nox1 using Nox1 shRNA/AAV2 particles (repeated-measures two-way ANOVA, F(3,36)=18.9, p<0.05 vs. scrambled shRNA/2VO; Fig. 10A). There was no significant difference in the swimming speed (repeated-measures two-way ANOVA, F(3,36)=2.645; Fig. 10B) between the training trials and the visible platform test. The times required to reach the visible platform during the visible platform test (mean±SE) for the four groups were not significantly different between the sham-operated, 2VO, and 2VO plus Nox1 shRNA/AAV2 groups (repeated-measures two-way ANOVA, F(3,24)=2.473; Fig. 10C). In addition, differences in performance were observed during the probe trial, as assessed by the percentage of time spent in the target quadrant or by the number of platform crossings during the 30 s probe (Fig. 10D, E). One-way ANOVA of the time spent in the target quadrant and number of platform crossings on the second probe trial showed that the between-group effects were significant (F(3,20)=5.998 and F(3,26)=6.743, respectively). A post hoc analysis revealed that 2VO rats which were subjected to Nox1 shRNA/AAV exhibited significant improvements during the probe trials compared with 2VO rats that were treated with scrambled shRNA/AAV (scb shRNA/AAV) (percentage of time spent in the target quadrant, p<0.05; number of platform crossings, p<0.05; Fig. 10D, E). In the novel object recognition (NOR) test and novel object location (NOL) test, discrimination ratios were significantly different between scramble shRNA plus sham control and scramble shRNA plus 2VO (NOR, F(3,36)=5.728, p<0.05; NOL, F(3,36)=2.517, p<0.05; Fig. 10F). In the novel location recognition test, the discrimination ratio was significantly different between scramble shRNA plus 2VO and Nox1 shRNA plus 2VO (F(3,28)=5.728, p<0.05; Fig. 10F). In the odorant discrimination test, the percentage of time spent digging was significantly different among groups (p<0.05). A post hoc analysis revealed that the increased percentage of time spent digging in the odorant discrimination test was significantly decreased in rats treated with Nox1 shRNA compared with scramble shRNA-treated/sham-operated rats (p<0.05; Supplementary Fig. S5). In parallel with the transduction rate of the Nox1 shRNA in the hippocampal CA1 subfield, the decreased spatial memory observed in 2VO rats was recovered during the performance of the probe trial, as assessed by the percentage of time spent in the target quadrant or by the number of platform crossings observed during the 30 s probe, NOR, and odorant discrimination tests (Fig. 10D–F).

FIG. 10.

Inhibition of Nox1 reduced the memory impairment in 2VO rats. The MWM test was employed to evaluate spatial memory. (A) time latency, (B) swimming speed, (C) time latency in visible platform test, (D) % time in target quadrant, and (E) number of passes through the platform were measured. (F) The novel object recognition and location test were performed at 13 weeks after 2VO. Exploratory time spent for novel objects was recorded, and the discrimination ratio was calculated. n=10/group, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 versus scb shRNA/Sham control; #p<0.05 versus scb shRNA/2VO. Time latency in visible platform test (C) was not different among groups. scb shRNA/Sham control, Sham-operated rats injected with scramble shRNA AAV particles; scb shRNA/2VO, 2VO-operated rats injected with scramble shRNA AAV particles; Nox1 shRNA/2VO, 2VO-operated rats injected with Nox1 shRNA AAV particles; Nox1 shRNA/SC, sham-operated rats injected with Nox1 shRNA AAV particles.

Discussion

In this study, we showed that the Nox complex mediates oxidative stress, hippocampal neuronal death, and cognitive impairment caused by CCH in 2VO-operated rats. We also demonstrated for the first time that the Nox1 isoform is constitutively expressed in hippocampal neurons and that its level is elevated after CCH in rats. Accumulation of the Nox1 complex, production of ROS, and nuclear DNA damage were found in degenerating hippocampal neurons. In addition, nuclear 8-oxo-dG staining preceded the other indications of neuronal degeneration. These results strongly indicate that Nox1-mediated oxidative damage may serve as critical upstream processes in neurodegeneration and cognitive impairment. We provide important evidence that the ROS produced by the Nox1/Rac1 complex accumulate in hippocampal neurons and damage nuclear DNA, which may be responsible for hippocampal neuronal neurodegeneration, and that Nox1-derived ROS cause cognitive impairment in chronic cerebral hypoperfused rats. The evidences that support this conclusion were as follows: (i) accumulation of the Nox1/Rac1 complex in hippocampal neurons in the 2VO-operated rat model; (ii) increased DHE and 8-oxo-dG staining in the nucleus; and (iii) subsequent attenuation of hippocampal neurodegeneration and cognitive impairment, either by chemical inhibition of Nox1 through apocynin or by genetic interventions targeting Nox1.

NADPH oxidase (Nox2 or gp91phox)-derived superoxide plays a role in bacterial killing through phagocytosis in polymorphonuclear leucocytes (60). Nox1 is the first homolog of Nox2 and was found in several tissues and cells, including the colon, smooth muscle, uterus, and prostate (69). Since then, a family of homologues has been found in various cells and tissues, especially in the brain (39, 63).

In the CNS, although NADPH oxidase-mediated ROS are required for normal cellular functions, such as long-term potentiation (72) and cardiovascular homeostasis (57), excess ROS generation may contribute to pathological conditions. Interestingly, several of the activators and effectors of the NADPH oxidase complex have also been implicated in the signal transduction mechanisms that underlie synaptic plasticity and memory formation (43, 44). A recent study has reported that NADPH-oxidase-derived ROS may play a protective role in regulating cerebral vascular tone during disease (49).

Several studies have shown that ROS derived from Nox2 in microglia, an immune component in the brain, cause oxidative stress in several brain diseases (18, 40). Recent studies, however, have indicated that Nox2 expression is not limited to microglia (1) and that other homologues, including Nox1, are involved in various pathological conditions in neuronal cells. Glutamate toxicity in SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells is largely attenuated by the inhibition of NADPH oxidase activation (53).

Our results demonstrated that CCH increased Nox1 expression in hippocampal neurons, suggesting that Nox1-mediated oxidative stress is a common feature observed in hippocampal cells under long-lasting ischemia. Consistently increased expression of Nox1 was observed in hippocampal neurons starting at 1 week after CCH. Both Nox2 and Nox4 were also detected in hippocampal neurons under normal conditions, but the expression levels of Nox2 and Nox4 were not altered by 2VO operation. Very little is known regarding the function of Nox1 in the CNS. A recent study showed the involvement of NADPH oxidase-generated ROS in the apoptotic death of cerebellar granule neurons and speculated a role for Nox1 in this process (19). Moreover, Jackman et al. investigated whether Nox1 is essential for superoxide production in large cerebral arteries in response to angiotensin II after ischemic stroke (32). Western blot analysis showed that the basal level of Nox1 detected in sham control rats might come from the vasculature of the brain (32).

Nox1-mediated superoxide generation requires other components, including Rac1 activation and Noxo1 and Noxa1, which are the homologues of p47phox and p67phox, respectively (22). Rac1, a small Rho GTPase, is a subunit that is important for the activation of Nox1-derived superoxide generation (22, 73). To activate the NADPH oxidase system, activated Rac1 forms a Nox1 enzyme complex in conjunction with Noxo1 and Noxa1 (20). In the present study, we found that hippocampal neurons were equipped with Noxo1 and Noxa1; moreover, CCH-mediated Rac1 activation was observed.

Apocynin can act as a NADPH oxidase inhibitor, and its neuroprotective effects have been reported in several CNS disorders (31, 36). Therefore, we tested whether apocynin reduces the ROS generation mediated by CCH and impairment of cognitive function. As previously reported, apocynin can penetrate the intact blood–brain barrier, offering neuroprotective effects against neuronal damage, particularly because of global and focal cerebral ischemia (61). However, the effect of apocynin on brain damage after experimental stroke depends on the dose used. In fact, the administration of apocynin at a dose of 2.5 mg/kg 30 min before reperfusion improved neurological function, reduced infarction volume, and reduced the incidence of cerebral hemorrhage. At higher doses (3.75 and 5 mg/kg), it increased brain hemorrhage (71). In addition, apocynin (5 mg/kg) protects against the oxidative stress and injury induced by global cerebral ischemia–reperfusion in the gerbil hippocampus (74). Other reports have indicated that the therapeutic potential of the systemic administration of apocynin is in the dose range of 2.5–12 mg/kg in various animal models (42, 66). Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) mice treated with 300 mg/kg of apocynin showed an increase in their average life spans (31). Recent studies, however, have reported the controversial finding that apocynin may work as an antioxidant instead of an NADPH oxidase inhibitor, especially in the vascular system (62). Zhang and colleagues demonstrated that apocynin significantly inhibited intracellular ROS generation, toll-like receptor 4-mediated proinflammatory cytokine expression, and proliferation and migration of vascular smooth muscle cells in wire injury-induced carotid neointima (55). These results suggest that apocynin may have a tissue-specific role. Based on these facts, an apocynin dose of 10 mg/kg was selected for our experiments. Brain sections of animals treated with 10 mg/kg of apocynin did not exhibit cerebral hemorrhage, either in sham controls or in 2VO-operated rats (data not shown). Both CCH-induced ROS and hippocampal neuronal death were significantly decreased by cotreatment with apocynin. Subsequent cognitive dysfunction was recovered by apocynin treatment. However, apocynin-treated sham-operated animals exhibited impairment in spatial learning. These results closely agreed with those of previous reports about pharmacological inhibitors of NADPH oxidase, as well as with studies that used mutant mice which are genetically deficient for either gp91phox or p47phox and indicated that NADPH oxidase is involved in long-term potentiation (LTP) (43). Nevertheless, a particularly important finding was that apocynin is protective against behavioral deficits in the 2VO animal group. We also confirmed the role of apocynin in the ligated common carotid artery of 2VO animals. Increased expression of proinflammatory cytokines in the ligated common carotid artery has not been altered by apocynin treatment.

To selectively target Nox1 in hippocampal neurons in vivo, we developed an adeno-associated virus serotype 2 (AAV2)-mediated overexpression or knockdown system. Many reports, including our recent study (17, 50), have shown that AAV2-mediated gene transfer provides an effective means of achieving long-term expression of target genes in nondividing cells, such as neurons (75), and that AAV-mediated shRNA delivery to the CNS for targeted knockdown of specific genes can also be successfully achieved (58). Four weeks after an AAV2 injection into the rat hippocampal CA1 subfield, more than 60% of the neurons were EGFP positive, indicating that our AAV system worked efficiently in hippocampal neurons. Similarly, the AAV2-mediated delivery of the Nox1 shRNA construct led to reduced DNA oxidative damage, a reduction of about 40% in hippocampal neuronal death, and attenuation of cognitive impairment induced by CCH. In parallel with the transduction rate of the Nox1 shRNA in the hippocampal CA1 subfield, 2VO-mediated ROS generation, DNA oxidation, neuronal loss, and cognitive impairment were decreased.

Conversely, other relevant sources of ROS in the brain, such as mitochondria (48) and xanthine oxidase, may be involved in 2VO (47). In addition, recent studies have demonstrated that CCH induced the activation of the brain renin–angiotensin system. A renin inhibitor ameliorated brain damage and working memory deficits in the model of chronic cerebral ischemia through the attenuation of oxidative stress (25). Therefore, various molecular and cellular mechanisms may be related to ROS generation and cognitive impairment in 2VO.

In summary, our study demonstrated that CCH may induce its toxic effects on hippocampal neurons by overactivating the Nox system, particularly Nox1, which, in turn, generates ROS and, eventually, results in hippocampal neuronal death and subsequent impairment of cognitive function. The results of this study also imply that hippocampal Nox1 may serve as a novel target for pharmacological intervention in VaD.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Rabbit anti-Nox1, goat anti-Nox1, rabbit anti-Nox2, rabbit anti-Nox4, rabbit anti-Noxo1, and rabbit anti-Noxa1 from Santa Cruz biotechnology; rat anti-CD11b from Serotec; and anti-goat immunoglobulin G (IgG), anti-rat IgG, and anti-rabbit IgG antibodies from Jackson ImmunoResearch were used. Other materials are described in the Supplementary Methods.

Animals and surgery

All procedures were approved by the Animal Experiment Review Board of Laboratory Animal Research Center of Konkuk University. Males are more susceptible to the cerebrovascular complications of hypertension, such as a stroke and VaD (62). Therefore, CCH was induced in male Wistar rats (weighing 200–250 g; 10 weeks age; Samtako BioKorea. Co. Ltd.).

The rats were anesthetized with 70% nitrogen and 30% isoflurane. Through a midline cervical incision, both common carotid arteries were exposed and double ligated with silk sutures (2VO). The sham-operated animals (SC) were treated in a similar manner to the operated rats except for the common carotid arteries occlusion. Detailed procedures are described in the Supplementary Methods. Detailed animal allocation and timeline for experiment were described (Supplementary Fig. S6).

Western blot analysis

Tissues were washed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and lysed on ice in RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP40, 0.25% Na-deoxycholate, and 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS]) containing a protease inhibitor mixture and phosphatase inhibitors (Sigma-Aldrich). Thirty μg of soluble protein was subjected to SDS-PAGE and electrotransferred onto a PVDF membrane. Specific protein bands were detected by using a specific anti-Nox1 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and Enhanced Chemiluminescence (Pierce).

Rac1 activation assay

One milligram of protein extracted from hippocampal tissue was incubated with 20 μl of agarose beads containing the p21-binding domain (PBD) of the p21-activated protein kinase 1 (PAK1), an effector of activated Rac, for 1 h at 4°C. The beads were collected by centrifugation and washed twice in the lysis buffer. The beads were resuspended in sample buffer and boiled for 5 min. Detailed procedures are described in the Supplementary Methods.

In situ visualization of superoxide

In situ visualization of superoxide and its derivative oxidant products was performed by hydroethidine histochemistry, as previously described (40). Detailed procedures are described in the Supplementary Methods.

Nissl staining

Nissl staining was performed by incubating the samples in 0.1% of Cresyl violet solution for 5–10 min at room temperature, quickly rinsing them in distilled water, dehydration in serially diluted ethanol, and cleaning in xylene. Detailed procedures are described in the Supplementary Methods.

Immunohistochemistry

After perfusion with saline and 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, brains were removed, and the forebrain and midbrain blocks were immersion fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and cryoprotected in sucrose. Serial coronal sections (40 μm) were cut on a cryostat, collected in cryopreservative, and stored at −20°C. For immunolabeling studies, sections were incubated with a blocking solution (5% horse serum and 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS, pH 7.5) and then with primary antibodies at 4°C overnight. Finally, the sections were incubated with secondary antibodies in a blocking solution at room temperature for 1 h. For antibody blocking, Nox1 antibody was preabsorbed with a five-fold high concentration of blocking peptide (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) in 500 μl of PBS at room temperature for 1 h.

Detailed procedures are described in the Supplementary Methods.

Quantitative analysis

Sections including the hippocampus from four rats per group were subjected to analysis. Five regions of interests (ROIs) of 0.1 mm2 per one section in the CA1 of the hippocampus (bregma −3.0 to −4.20 mm; six sections per rat, every fifth sections) were selected. The number of DHE-, MDA-, c-fos, nitrotyrosine-, 8-oxo-dG-, NeuN- or Nissl-positive neurons of total cells was counted in each ROI and averaged. Data were represented as a percentage of total cell and signal positive cell counts. All quantitative analyses were carried out in a blind manner.

Total RNA extraction, RT-PCR, and real-time PCR analysis

Total RNA was extracted from the hippocampal tissue using the Trizol reagent. Reverse transcription was performed for 40 min at 42°C with 1 μg of total RNA using 1 U/μl of superscript II reverse transcriptase. Oligo (dT) and random primers were used as primers. The samples were then heated at 94°C for 5 min to terminate the reaction. The cDNA obtained from 1 μg of total RNA was used as a template for PCR amplification. Detailed procedures and real-time quantitative RT-PCR methods are described in the Supplementary Methods.

Adeno-associated virus 2-mediated Nox1 knockdown

AAV particles containing either Nox1 shRNA/AAV or scb shRNA/AAV (17) were stereotaxically injected into the hippocampal CA1 subfield for 4 weeks before 2VO or sham operation (n=10/group). Rats were deeply anesthetized (ketamine and xylazine mixture 30 mg/kg, intraperitoneal [IP]) and placed in a rat stereotaxic apparatus. Nox1 shRNA/AAV and scb shRNA/AAV were then injected into both sites in the hippocampal CA1 subfield (coordinate: anteroposterior, −3.3 mm; mediolateral,±2.0 mm; dorsoventral, −3.5 mm). Detailed procedures are described in the Supplementary Methods.

Behavior test

The MWM test was employed to evaluate the learning and memory of rats (16). The MWM procedure was based on a principle, where if the animals were placed in a large pool of water, they would attempt to escape from the water by finding an escape platform. Moreover, novel location recognition and NOR behavior test and olfactory discrimination task were performed to evaluate cognitive impairment. Detailed procedures are described in the Supplementary Methods.

Data analysis and statistics

Parameters for spatial memory, including the search error and time latency as well as swimming speed, were analyzed by two-way repeated measures ANOVA followed by a post hoc least significant difference's multiple Comparison Test. One-way ANOVA was conducted to compare the results of the probe trials, cued behavior, percent exploratory preference, percent time spent digging, and quantitative data of the Western blot analysis and immunohistochemistry (mean±SE). Statistical analysis was performed using a one-way ANOVA followed by Newman–Keuls Multiple Comparison Test. Null hypotheses of no difference were rejected if p-values were less than 0.05. Data analyses were performed with the SPSS software version 12.0.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations Used

- 2VO

two-vessel occlusion

- 6-OHDA

6-hydroxydopamine

- 8-oxo-dG

8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine

- AAV2

adeno-associated virus serotype 2

- AD

Alzheimer's disease

- ALS

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- CAT

catalase

- CCH

chronic cerebral hypoperfusion

- ChAT

choline acetyl-transferase

- CNS

central nervous system

- DHE

dihydroethidium

- EGFP

enhanced green fluorescent protein

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- GFAP

glial fibrillary acidic protein

- GPx

glutathione peroxidase

- GR

glutathione reductase

- IgG

immunoglobulin G

- IL

interleukin

- IP

intraperitoneal

- LTP

long-term potentiation

- MCI

mild cognitive impairment

- MDA

malondialdehyde

- MWM

Morris water maze

- NADPH

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate

- NMDA

N-methyl-D-aspartate

- NOL

novel object location

- NOR

novel object recognition

- Nox

NADPH oxidase

- Nox1

NADPH oxidase 1

- Nox2

gp91phox

- Nox4

NADPH oxidase 4

- Noxa1

NOX activator 1

- Noxo1

NOX organizer 1

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- ROI

region of interest

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- RT-PCR

reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction

- scb shRNA/AAV

scrambled shRNA/AAV

- SN

substantia nigra

- SOD

superoxide dismutase

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor alpha

- VaD

vascular dementia

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MEST) (No. 2011-0017016).

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Abramov AY, Jacobson J, Wientjes F, Hothersall J, Canevari L, and Duchen MR. Expression and modulation of an NADPH oxidase in mammalian astrocytes. J Neurosci 25: 9176–9184, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aggarwal NT. and Decarli C. Vascular dementia: emerging trends. Semin Neurol 27: 66–77, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aliev G, Smith MA, Obrenovich ME, de la Torre JC, and Perry G. Role of vascular hypoperfusion-induced oxidative stress and mitochondria failure in the pathogenesis of Azheimer disease. Neurotox Res 5: 491–504, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barone E, Di Domenico F, Cenini G, Sultana R, Cini C, Preziosi P, Perluigi M, Mancuso C, and Butterfield DA. Biliverdin reductase—a protein levels and activity in the brains of subjects with Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment. Biochim Biophys Acta 1812: 480–487, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barone E, Di Domenico F, Cenini G, Sultana R, Coccia R, Preziosi P, Perluigi M, Mancuso C, and Butterfield DA. Oxidative and nitrosative modifications of biliverdin reductase-A in the brain of subjects with Alzheimer's disease and amnestic mild cognitive impairment. J Alzheimers Dis 25: 623–633, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barone E, Di Domenico F, Sultana R, Coccia R, Mancuso C, Perluigi M, and Butterfield DA. Heme oxygenase-1 posttranslational modifications in the brain of subjects with Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment. Free Radic Biol Med 52: 2292–2301, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bedard K. and Krause KH. The NOX family of ROS-generating NADPH oxidases: physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol Rev 87: 245–313, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bennett S, Grant MM, and Aldred S. Oxidative stress in vascular dementia and Alzheimer's disease: a common pathology. J Alzheimers Dis 17: 245–257, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Block ML. NADPH oxidase as a therapeutic target in Alzheimer's disease. BMC Neurosci 9Suppl 2: S8, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bokoch GM. and Diebold BA. Current molecular models for NADPH oxidase regulation by Rac GTPase. Blood 100: 2692–2696, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brennan AM, Suh SW, Won SJ, Narasimhan P, Kauppinen TM, Lee H, Edling Y, Chan PH, and Swanson RA. NADPH oxidase is the primary source of superoxide induced by NMDA receptor activation. Natu Neurosci 12: 857–863, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bruce-Keller AJ, Gupta S, Parrino TE, Knight AG, Ebenezer PJ, Weidner AM, LeVine H, 3rd, Keller JN, and Markesbery WR. NOX activity is increased in mild cognitive impairment. Antioxid Redox Signal 12: 1371–1382, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carnesecchi S, Deffert C, Pagano A, Garrido-Urbani S, Metrailler-Ruchonnet I, Schappi M, Donati Y, Matthay MA, Krause KH, and Barazzone Argiroffo C. NADPH oxidase-1 plays a crucial role in hyperoxia-induced acute lung injury in mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 180: 972–981, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Casado A, Encarnacion Lopez-Fernandez M, Concepcion Casado M, and de La Torre R. Lipid peroxidation and antioxidant enzyme activities in vascular and Alzheimer dementias. Neurochem Res 33: 450–458, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng G, Cao Z, Xu X, van Meir EG, and Lambeth JD. Homologs of gp91phox: cloning and tissue expression of Nox3, Nox4, and Nox5. Gene 269: 131–140, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choi BR, Lee SR, Han JS, Woo SK, Kim KM, Choi DH, Kwon KJ, Han SH, Shin CY, Lee J, Chung CS, Lee SR, and Kim HY. Synergistic memory impairment through the interaction of chronic cerebral hypoperfusion and amlyloid toxicity in a rat model. Stroke 42: 2595–2604, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi DH, Cristovao AC, Guhathakurta S, Lee J, Joh TH, Beal MF, and Kim YS. NADPH oxidase 1-mediated oxidative stress leads to dopamine neuron death in Parkinson's disease. Antioxid Redox Signal 16: 1033–1045, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choi SH, Lee DY, Chung ES, Hong YB, Kim SU, and Jin BK. Inhibition of thrombin-induced microglial activation and NADPH oxidase by minocycline protects dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra in vivo. J Neurochem 95: 1755–1765, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coyoy A, Valencia A, Guemez-Gamboa A, and Moran J. Role of NADPH oxidase in the apoptotic death of cultured cerebellar granule neurons. Free Radic Biol Med 45: 1056–1064, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cristovao AC, Choi DH, Baltazar G, Beal MF, and Kim YS. The role of NADPH oxidase 1-derived reactive oxygen species in paraquat-mediated dopaminergic cell death. Antioxid Redox Signal 11: 2105–2118, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cryer PE. Hypoglycemia, functional brain failure, and brain death. J Clin Invest 117: 868–870, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Deken X, Wang D, Many MC, Costagliola S, Libert F, Vassart G, Dumont JE, and Miot F. Cloning of two human thyroid cDNAs encoding new members of the NADPH oxidase family. J Biol Chem 275: 23227–23233, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de la Torre JC. Vascular risk factor detection and control may prevent Alzheimer's disease. Ageing Res Rev 9: 218–225, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Di Domenico F, Barone E, Mancuso C, Perluigi M, Cocciolo A, Mecocci P, Butterfield DA, and Coccia R. HO-1/BVR-a system analysis in plasma from probable Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment subjects: a potential biochemical marker for the prediction of the disease. J Alzheimers Dis 32: 277–289, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dong YF, Kataoka K, Toyama K, Sueta D, Koibuchi N, Yamamoto E, Yata K, Tomimoto H, Ogawa H, and Kim-Mitsuyama S. Attenuation of brain damage and cognitive impairment by direct renin inhibition in mice with chronic cerebral hypoperfusion. Hypertension 58: 635–642, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Edens WA, Sharling L, Cheng G, Shapira R, Kinkade JM, Lee T, Edens HA, Tang X, Sullards C, Flaherty DB, Benian GM, and Lambeth JD. Tyrosine cross-linking of extracellular matrix is catalyzed by Duox, a multidomain oxidase/peroxidase with homology to the phagocyte oxidase subunit gp91phox. J Cell Biol 154: 879–891, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Erkinjuntti T, Roman G, Gauthier S, Feldman H, and Rockwood K. Emerging therapies for vascular dementia and vascular cognitive impairment. Stroke 35: 1010–1017, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Famulari AL, Marschoff ER, Llesuy SF, Kohan S, Serra JA, Dominguez RO, Repetto M, Reides C, and Sacerdote de Lustig E. The antioxidant enzymatic blood profile in Alzheimer's and vascular diseases. Their association and a possible assay to differentiate demented subjects and controls. J Neurol Sci 141: 69–78, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Farkas E, Luiten PG, and Bari F. Permanent, bilateral common carotid artery occlusion in the rat: a model for chronic cerebral hypoperfusion-related neurodegenerative diseases. Brain Res Rev 54: 162–180, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gackowski D, Rozalski R, Siomek A, Dziaman T, Nicpon K, Klimarczyk M, Araszkiewicz A, and Olinski R. Oxidative stress and oxidative DNA damage is characteristic for mixed Alzheimer disease/vascular dementia. J Neurol Sci 266: 57–62, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harraz MM, Marden JJ, Zhou W, Zhang Y, Williams A, Sharov VS, Nelson K, Luo M, Paulson H, Schoneich C, and Engelhardt JF. SOD1 mutations disrupt redox-sensitive Rac regulation of NADPH oxidase in a familial ALS model. J Clin Invest 118: 659–670, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jackman KA, Miller AA, Drummond GR, and Sobey CG. Importance of NOX1 for angiotensin II-induced cerebrovascular superoxide production and cortical infarct volume following ischemic stroke. Brain Res 1286: 215–220, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jellinger KA. Morphologic diagnosis of “vascular dementia”—a critical update. J Neurol Sci 270: 1–12, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ji HJ, Hu JF, Wang YH, Chen XY, Zhou R, and Chen NH. Osthole improves chronic cerebral hypoperfusion induced cognitive deficits and neuronal damage in hippocampus. Eur J Pharmacol 636: 96–101, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jiwa NS, Garrard P, and Hainsworth AH. Experimental models of vascular dementia and vascular cognitive impairment: a systematic review. J Neurochem 115: 814–828, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kahles T, Luedike P, Endres M, Galla HJ, Steinmetz H, Busse R, Neumann-Haefelin T, and Brandes RP. NADPH oxidase plays a central role in blood-brain barrier damage in experimental stroke. Stroke 38: 3000–3006, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kauppinen TM, Higashi Y, Suh SW, Escartin C, Nagasawa K, and Swanson RA. Zinc triggers microglial activation. J Neurosci 28: 5827–5835, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim HJ, Lee JH, Kim SJ, Oh GS, Moon HD, Kwon KB, Park C, Park BH, Lee HK, Chung SY, Park R, and So HS. Roles of NADPH oxidases in cisplatin-induced reactive oxygen species generation and ototoxicity. J Neurosci 30: 3933–3946, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim MJ, Shin KS, Chung YB, Jung KW, Cha CI, and Shin DH. Immunohistochemical study of p47Phox and gp91Phox distributions in rat brain. Brain Res 1040: 178–186, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim YS, Choi DH, Block ML, Lorenzl S, Yang L, Kim YJ, Sugama S, Cho BP, Hwang O, Browne SE, Kim SY, Hong JS, Beal MF, and Joh TH. A pivotal role of matrix metalloproteinase-3 activity in dopaminergic neuronal degeneration via microglial activation. FASEB J 21: 179–187, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim YS, Morgan MJ, Choksi S, and Liu ZG. TNF-induced activation of the Nox1 NADPH oxidase and its role in the induction of necrotic cell death. Mol Cell 26: 675–687, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kimura S, Zhang GX, Nishiyama A, Shokoji T, Yao L, Fan YY, Rahman M, Suzuki T, Maeta H, and Abe Y. Role of NAD(P)H oxidase- and mitochondria-derived reactive oxygen species in cardioprotection of ischemic reperfusion injury by angiotensin II. Hypertension 45: 860–866, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kishida KT, Hoeffer CA, Hu D, Pao M, Holland SM, and Klann E. Synaptic plasticity deficits and mild memory impairments in mouse models of chronic granulomatous disease. Mol Cell Biol 26: 5908–5920, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kishida KT. and Klann E. Sources and targets of reactive oxygen species in synaptic plasticity and memory. Antioxid Redox Signal 9: 233–244, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kleinschnitz C, Grund H, Wingler K, Armitage ME, Jones E, Mittal M, Barit D, Schwarz T, Geis C, Kraft P, Barthel K, Schuhmann MK, Herrmann AM, Meuth SG, Stoll G, Meurer S, Schrewe A, Becker L, Gailus-Durner V, Fuchs H, Klopstock T, de Angelis MH, Jandeleit-Dahm K, Shah AM, Weissmann N, and Schmidt HH. Post-stroke inhibition of induced NADPH oxidase type 4 prevents oxidative stress and neurodegeneration. PLoS Biol 8: pii:, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lin MS, Chiu MJ, Wu YW, Huang CC, Chao CC, Chen YH, Lin HJ, Li HY, Chen YF, Lin LC, Liu YB, Chao CL, Tseng WY, Chen MF, and Kao HL. Neurocognitive improvement after carotid artery stenting in patients with chronic internal carotid artery occlusion and cerebral ischemia. Stroke 42: 2850–2854, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu H. and Zhang J. Cerebral hypoperfusion and cognitive impairment: the pathogenic role of vascular oxidative stress. Int J Neurosci 122: 494–499, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mancuso C, Scapagini G, Curro D, Giuffrida Stella AM, De Marco C, Butterfield DA, and Calabrese V. Mitochondrial dysfunction, free radical generation and cellular stress response in neurodegenerative disorders. Front Biosci 12: 1107–1123, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miller AA, Drummond GR, and Sobey CG. Novel isoforms of NADPH-oxidase in cerebral vascular control. Pharmacol Ther 111: 928–948, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mouravlev A, Dunning J, Young D, and During MJ. Somatic gene transfer of cAMP response element-binding protein attenuates memory impairment in aging rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103: 4705–4710, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Naritomi H. Experimental basis of multi-infarct dementia: memory impairments in rodent models of ischemia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 5: 103–111, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ni J, Ohta H, Matsumoto K, and Watanabe H. Progressive cognitive impairment following chronic cerebral hypoperfusion induced by permanent occlusion of bilateral carotid arteries in rats. Brain Res 653: 231–236, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nikolova S, Lee YS, and Kim JA. Rac1-NADPH oxidase-regulated generation of reactive oxygen species mediates glutamate-induced apoptosis in SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells. Free Radic Res 39: 1295–1304, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Noh KM. and Koh JY. Induction and activation by zinc of NADPH oxidase in cultured cortical neurons and astrocytes. J Neurosci 20: RC111, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pi Y, Zhang LL, Li BH, Guo L, Cao XJ, Gao CY, and Li JC. Inhibition of reactive oxygen species generation attenuates TLR4-mediated proinflammatory and proliferative phenotype of vascular smooth muscle cells. Lab Invest 93: 880–887, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pimentel-Coelho PM, Michaud JP, and Rivest S. Effects of mild chronic cerebral hypoperfusion and early amyloid pathology on spatial learning and the cellular innate immune response in mice. Neurobiol Aging 34: 679–693, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rajagopalan S, Kurz S, Munzel T, Tarpey M, Freeman BA, Griendling KK, and Harrison DG. Angiotensin II-mediated hypertension in the rat increases vascular superoxide production via membrane NADH/NADPH oxidase activation. Contribution to alterations of vasomotor tone. J Clin Invest 97: 1916–1923, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rodriguez-Lebron E, Denovan-Wright EM, Nash K, Lewin AS, and Mandel RJ. Intrastriatal rAAV-mediated delivery of anti-huntingtin shRNAs induces partial reversal of disease progression in R6/1 Huntington's disease transgenic mice. Mol Ther 12: 618–633, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Roman GC. Vascular dementia: distinguishing characteristics, treatment, and prevention. J Am Geriatr Soc 51: S296–S304, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rossi F. and Zatti M. Biochemical aspects of phagocytosis in polymorphonuclear leucocytes. NADH and NADPH oxidation by the granules of resting and phagocytizing cells. Experientia 20: 21–23, 1964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schiavone S, Sorce S, Dubois-Dauphin M, Jaquet V, Colaianna M, Zotti M, Cuomo V, Trabace L, and Krause KH. Involvement of NOX2 in the development of behavioral and pathologic alterations in isolated rats. Biol Psychiatry 66: 384–392, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Selemidis S, Sobey CG, Wingler K, Schmidt HH, and Drummond GR. NADPH oxidases in the vasculature: molecular features, roles in disease and pharmacological inhibition. Pharmacol Ther 120: 254–291, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Serrano F, Kolluri NS, Wientjes FB, Card JP, and Klann E. NADPH oxidase immunoreactivity in the mouse brain. Brain Res 988: 193–198, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shi GX, Liu CZ, Wang LP, Guan LP, and Li SQ. Biomarkers of oxidative stress in vascular dementia patients. Can J Neurol Sci 39: 65–68, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shibata M, Yamasaki N, Miyakawa T, Kalaria RN, Fujita Y, Ohtani R, Ihara M, Takahashi R, and Tomimoto H. Selective impairment of working memory in a mouse model of chronic cerebral hypoperfusion. Stroke 38: 2826–2832, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sonta T, Inoguchi T, Tsubouchi H, Sekiguchi N, Kobayashi K, Matsumoto S, Utsumi H, and Nawata H. Evidence for contribution of vascular NAD(P)H oxidase to increased oxidative stress in animal models of diabetes and obesity. Free Radic Biol Med 37: 115–123, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Suh SW, Gum ET, Hamby AM, Chan PH, and Swanson RA. Hypoglycemic neuronal death is triggered by glucose reperfusion and activation of neuronal NADPH oxidase. J Clin Invest 117: 910–918, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Suh SW, Shin BS, Ma H, Van Hoecke M, Brennan AM, Yenari MA, and Swanson RA. Glucose and NADPH oxidase drive neuronal superoxide formation in stroke. Ann Neurol 64: 654–663, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Suh YA, Arnold RS, Lassegue B, Shi J, Xu X, Sorescu D, Chung AB, Griendling KK, and Lambeth JD. Cell transformation by the superoxide-generating oxidase Mox1. Nature 401: 79–82, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tammariello SP, Quinn MT, and Estus S. NADPH oxidase contributes directly to oxidative stress and apoptosis in nerve growth factor-deprived sympathetic neurons. J Neurosci 20: RC53, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tang XN, Cairns B, Cairns N, and Yenari MA. Apocynin improves outcome in experimental stroke with a narrow dose range. Neuroscience 154: 556–562, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tejada-Simon MV, Serrano F, Villasana LE, Kanterewicz BI, Wu GY, Quinn MT, and Klann E. Synaptic localization of a functional NADPH oxidase in the mouse hippocampus. Mol Cell Neurosci 29: 97–106, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ueyama T, Geiszt M, and Leto TL. Involvement of Rac1 in activation of multicomponent Nox1- and Nox3-based NADPH oxidases. Mol Cell Biol 26: 2160–2174, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wang Q, Tompkins KD, Simonyi A, Korthuis RJ, Sun AY, and Sun GY. Apocynin protects against global cerebral ischemia-reperfusion-induced oxidative stress and injury in the gerbil hippocampus. Brain Res 1090: 182–189, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wang T, Wang J, Yin C, Liu R, Zhang JH, and Qin X. Down-regulation of Nogo receptor promotes functional recovery by enhancing axonal connectivity after experimental stroke in rats. Brain Res 1360: 147–158, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wilkinson BL. and Landreth GE. The microglial NADPH oxidase complex as a source of oxidative stress in Alzheimer's disease. J Neuroinflamm 3: 30, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Won SJ, Yoo BH, Kauppinen TM, Choi BY, Kim JH, Jang BG, Lee MW, Sohn M, Liu J, Swanson RA, and Suh SW. Recurrent/moderate hypoglycemia induces hippocampal dendritic injury, microglial activation, and cognitive impairment in diabetic rats. J Neuroinflamm 9: 182, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.