Abstract

Tenderness is the most important meat quality trait, which is determined by intracellular environment and extracellular matrix. Particularly, specific protein degradation and protein modification can disrupt the architecture and integrity of muscle cells so that improves the meat tenderness. Endogenous proteolytic systems are responsible for modifying proteinases as well as the meat tenderization. Abundant evidence has testified that calpains (CAPNs) including calpain I (CAPN1) and calpastatin (CAST) have the closest relationship with tenderness in livestock. They are involved in a wide range of physiological processes including muscle growth and differentiation, pathological conditions and post-mortem meat aging. Whereas, Calpain3 (CAPN3) has been established as an important activating enzyme specifically expressed in livestock’s skeletal muscle, but its role in domestic animals meat tenderization remains controversial. In this review, we summarize the role of CAPN1, calpain II (CAPN2) and CAST in post-mortem meat tenderization, and analyse the relationship between CAPN3 and tenderness in domestic animals. Besides, the possible mechanism affecting post-mortem meat aging and improving meat tenderization, and current possible causes responsible for divergence (whether CAPN3 contributes to animal meat tenderization or not) are inferred. Only the possible mechanism of CAPN3 in meat tenderization has been confirmed, while its exact role still needs to be studied further.

Keywords: Calpains, Post-mortem Meat tenderization, Proteolysis System, Domestic Animals

INTRODUCTION

Nowadays, meat quality has been the focus for livestock industries and also consumers’ need. As for most consumers, tenderness is considered as the most important feature for eating quality. Up until now, the primary focus on beef tenderness has been on a longer storage time (at least 14 d) in cooling conditions to obtain the final tenderness. Many studies have shown that the meat tenderization process is complex and could be affected by several different pathways including pre-slaughter and post-slaughter factors and their interaction (Destefanis et al., 2008). Within these factors, it is likely that ultimate tenderness is mainly determined by the extent of proteolysis of key target skeleton proteins within muscle fibres and the alteration of muscle structure (Taylor et al., 1995; Koohmaraie and Geesink, 2006).

CAPNs are a large family of intracellular Ca2+-dependent cysteine proteases. The CAPN system is one of the endogenous proteolysis systems, which plays a major role in meat tenderization. It is consistent with the basic criteria: i) proteases must be endogenous to skeletal muscle cells; ii) they must be able to mimic postmortem changes in myofibrils in vitro under optimum conditions; iii) these proteases are available to cytoskeletal protein of myofibrils in tissue (Goll et al., 1983; Koohmaraie, 1996). Numerous studies have shown that the proteolytic CAPNs activity is responsible for meat tenderization (Sentandreu et al., 2002; Koohmaraie and Geesink, 2006). Therefore, the CAPN system is regarded as the main endogenous protease system contributing to postmortem proteolysis and meat tenderization (Koohmaraie and Geesink, 2006; Bernard et al., 2007; Neath et al., 2007).

Even if considerable evidence linking CAPNs (CAPN1 and CAST) to meat tenderization has been established (Koohmaraie et al., 1991), the role of CAPN3 and other members of CAPN family are still controversial. Some evidence supports its involvement, some rejects. CAPN3 is one member of the CAPN family, located in the N2 line by binding to titin (the giant myofibrillar protein) (Sorimachi et al., 1995), where proteolysis has been linked to meat tenderization (Taylor et al., 1995). Thus, its location has encouraged scientists to look for much more functions. In this review, we mainly concentrate on determining whether CAPN3 functions in postmortem proteolysis and meat tenderization of domestic animals. Meanwhile, the role of CAPN1, CAPN2 and CAST in postmortem meat tenderization is also mentioned.

MEAT TENDERNESS

The conversion of muscle into meat

After slaughter, muscle goes rapidly into rigor mortis and the muscle is tough and tenderness declines. Subsequently, as the aging process occurs there is an improvement in tenderness (Grobbel et al., 2008).

In vivo, energy is obtained through aerobic metabolism. After slaughter, aerobic metabolism declines with the decreasing oxygen supply, instead, anaerobic metabolism accounts for most glycolysis (Mayes, 1993), and a pH value that falls to 5.4 to 5.8. In addition, many investigations have shown a series of intracellular environmental changes occurred during the process that produces a high ionic strength and muscle cells that are unable to keep the reducing conditions (Huff Lonergan et al., 2010). Alteration in pH/ionic strengths may produce conformational changes of the proteolytic enzymes that activate them to autolyze and hydrolyze the protein substrates (Huff-Lonergan and Lonergan, 1999; Melody et al., 2004). In particular, the rate of pH decline is closely related to the extent of proteolysis of myofibrillar proteins by CAPNs, such as the production of PSE pork (Barbut et al., 2008). Furthermore, the decline of temperature and pH parallels the development of rigor, and is partially associated with it (Huff Lonergan et al., 2010). Consequently, these changes have an effect on the rate of tenderization and occasionally on water holding capacity (Melody et al., 2004; Simmons et al., 2008).

The factors affected meat tenderness

Meat tenderness is considered as the most important parameter determining meat quality (Moeller et al., 2010). Generally, the phenotype of tenderness is the result of genetic-environmental interaction (Peaston and Whitelaw, 2006). Changes on-farm, pre-slaughter, post-slaughter processing factors and other man-made factors such as electric stimulus account for the environmental contribution. Factors originated from the muscle also contribute to meat tenderness, such as intermuscular variation, sensitivity of muscle structural proteins to proteolysis, the distribution of muscular connective tissue and sarcomere length (Koohmaraie et al., 1988; Seideman et al., 1989; Wheeler and Koohmaraie, 1999). A range of studies have shown that postmortem factors, particularly temperature and sarcomere length could determine pre-rigor and proteolysis and affect the conversion of muscle to meat (Taylor et al., 1995; Koohmaraie et al., 1996; Roberts et al., 1996; Gollasch and Nelson, 1997; Hwang et al., 2003; Koohmaraie and Geesink, 2006). For muscle itself, meat tenderness is determined by the structure of myofibres, integrity of muscle cells, the intracellular protease activity and the extracellular matrix (Mccormick, 2009). The ultimate tenderness depends upon the interplay between intra- and extra factors such as the movement of water from myofibrils to extracellular space. Much research has indicated that three endogenous proteolytic systems participated in the postmortem proteolysis and meat tenderization: the system of CAPNs, cathepsins and proteasomes (mainly multicatalytic proteinase complex (MPC), called 20S proteasome) (Dutaud et al., 2006; Koohmaraie and Geesink, 2006; Bernard et al., 2007; Kemp et al., 2010). Here, we focus on the effect of the endogenous protease activity especially the CAPN system on meat tenderization.

ROLE OF CAPN1, CAPN2, CAPN3 AND CAST IN MEAT TENDERIZATION

The CAPN system

Introduction of CAPN system: Discovered in 1964 (Guroff, 1964), CAPNs are a large family of intracellular Ca2+-dependent cysteine neutral proteinases (EC 3.4.22.17; Clan CA, family C02), which are found in almost all eukaryotes and a few bacteria but not in archaebacteria (Croall and Demartino, 1991; Goll et al., 2003). To date, 14 isoforms have been identified, which are expressed in ubiquitous and tissue-specific forms (Goll et al., 2003). In skeletal muscle, the CAPN family contains at least three proteases: CAPN1 (μ-calpain), CAPN2 (m-calpain) and CAPN3 (p94), as well as CAST-being a CAPN inhibitor (Goll et al., 2003; Koohmaraie and Geesink, 2006; Moudilou et al., 2010), and they are encoded by CAPN1, CAPN2, CAPN3 and CAST genes (Moudilou et al., 2010), respectively.

Structure: The structure of CAPNs is highly homologous. Both CAPN1 and CAPN2 consist of a discrepant 80-kDa subunit (Imajoh et al., 1988; Ohno et al., 1990) and an identical 28-kDa subunit encoded by CAPN4 (Emori et al., 1986; Ohno et al., 1990). In the large subunit, four domains are distinguished (domains I–IV). Domains V and VI are classified in the small subunit (Goll et al., 2003). Domain I modulates the proteolytic activity by removing it or not. Domain II is catalytic with a Cys residue. Domain III, a Ca2+-binding domain is linked to the catalytic domain II, which may regulate the activity of CAPN by participating in critical electrostatic interactions and the binding of phospholipids (Hosfield et al., 1999; Strobl et al., 2000; Tompa et al., 2001). Domain IV contains four sets of sequences that predict EF-hand Ca2+-binding sites. Domain V is enriched by glycine residues with hydrophobicity (Eisenberg et al., 1982) and is mainly involved in autolysis. Domain VI is similar to IV and consists of five Ca2+-binding areas (Ohno et al., 1986; Blanchard et al., 1997; Lin et al., 1997). Meanwhile, CAPN1 and CAPN2 are activated in vitro at micromolar and millimolar calcium concentrations, respectively. However, CAPN3 is a 94-kDa protein whose structure is homologous to CAPN1 (54%) and CAPN2 (51%), and shares the similar properties of Ca2+-dependent activation and maximal activity at neutral pH (Goll et al., 2003). It also has specific characteristics (Sorimachi et al., 1995). i) CAPN3 is mainly expressed in skeletal muscle (Sorimachi et al., 1989), yet, during development, it also occurs in lens, liver, brain and cardiac muscle (Poussard et al., 1996; Fougerousse et al., 1998; Ma et al., 1998; Konig et al., 2003). ii) CAPN3 is likely to function as a homodimer due to its lacking a small subunit (28 kDa) (Blanchard et al., 1996; Blanchard et al., 1997; Kinbara et al., 1998; Ravulapalli et al., 2005; Ravulapalli et al., 2009). At the same time, CAPN3 has some unique domains distinguishing it from the ubiquitous CAPNs, including its NH2-terminal domain I (contains 20 to 30 additional amino acids) and two “insertion sequences” which contain 62 and 77 amino acids at the COOH-terminal regions of domain II and III, called IS1 and IS2, respectively (Goll et al., 2003). iii) It is thought that CAPN3 is activated at the nanomolar calcium concentration (Garcia Diaz et al., 2006), although Ca2+-dependency of CAPN3 is not clear. iv) CAPN3 is very unstable and undergoes fast autoproteolytic degradation (Sorimachi et al., 1993; Kinbara et al., 1998). CAST has a molecular mass of 60 to 70 kDa and is a specific endogenous inhibitor against CAPN1 and CAPN2 but not CAPN3 (Sorimachi et al., 1993; Moudilou et al., 2010). It contains four inhibitory domains, each of which can inhibit CAPN activity. And three regions (A, B, C) are identified within these domains, which are predicted to interact with CAPNs. Region B between A, and C blocks the active site of CAPNs (Goll et al., 2003; Wendt et al., 2004; Croall and Ersfeld, 2007; Kemp et al., 2010). Its structure is different between species (Ishida et al., 1991; Cong et al., 1998; Goll et al., 2003). Moreover, CAPN3 may regulate the activity of ubiquitous CAPNs via degrading CAST (Ono et al., 2004).

Location and function: What’s more, most of CAPNs are intracellular: 70% of CAPN1 is bound to myofibrils, a large portion of CAPN3 is situated in a sarcomere near the N- and M-line, whereas a majority of CAPN2 is located in the cytosol (Ilian et al., 2004c; Xu et al., 2009), and the location of CAST is similar to the CAPNs (Tullio et al., 1999).

Based on the structural features of binding Ca2+, associating membrane/phospholipids and recent studies, CAPNs have been confirmed to be involved in various important cellular processes including cell motility, signal transduction pathways, apoptosis, cell differentiation and regulation of the cytoskeleton through modifying the primary and secondary structural features of target proteins (Croall and Ersfeld, 2007). Unlike other intracellular proteolytic systems (cathepsins and proteasomes), CAPNs act in a limited proteolysis and play a critical role in proteolytic modulating and processing rather than degradation. Therefore, CAPNs are identified as the intracellular “modulator” proteases (Ono et al., 2004; Ono et al., 2010). Even while intensive research on CAPNs is still in development, early results have strongly stimulated increased interest in their role in postmortem meat tenderization. Accumulated evidence indicates that CAPNs contribute to postmortem proteolysis whether in pre- and post-rigor muscle. For this reason, CAPNs are considered to be the major protease responsible for key muscle proteins degradation (Koohmaraie, 1992; Huff-Lonergan et al., 1996; Huff-Lonergan and Lonergan, 1999).

A BRIEF OVERVIEW OF CAPN1, CAPN2, CAPN3 AND CAST IN MEAT TENDERIZATION OF DOMESTIC ANIMAL

It is reported that the CAPN system makes a contribution to postmortem proteolysis and meat tenderization in domestic animals (Table 1) (Koohmaraie, 1992; Huff-Lonergan and Lonergan, 2005). In skeletal muscle, the CAPN system comprises ubiquitous CAPNs (CAPN1 and CAPN2), skeletal-specific CAPN3 (also called p94) and endogenous inhibitor- CAST (Goll et al., 2003).

Table 1.

CAPN1, CAPN3 and CAST genes associated with meat quality

| Meat quality parameters | Model system | Genes | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Warner-Bratzler Shear force | Ovine, beef cattle, pig | CAPN1, CAPN3, CAST | (Ilian et al., 2001; Veiseth et al., 2001; Page et al., 2002; Ilian et al., 2004a; Ilian et al., 2004b; Page et al., 2004; Veiseth et al., 2004; White et al., 2005; Casas et al., 2006; Schenkel et al., 2006; Corva et al., 2007; Barendse et al., 2008; Lindholm-Perry et al., 2009; Cafe et al., 2010; Pinto et al., 2010; Gandolfi et al., 2011) |

| Meat tenderness of the descendants | Beef cattle | CAPN1, CAST | (Casas et al., 2006) |

| Myofibril Fragmentation index (MFI) | Ovine | CAPN3 | (Ilian et al., 2004a) |

| Proteolysis of key myofibril proteins | Ovine, Chicken | CAPN3, CAPN1 | (Ilian et al., 2004a; Ilian et al., 2004b; Lee et al., 2008) |

| Flavor intensity | Beef cattle | CAPN1, CAST | (Casas et al., 2006b) |

| Marbling score | Korean cattle | CAPN1 | (Cheong et al., 2008) |

| pH | Yanbian Yellow cattle, pig |

CAPN1, CAST | (Sieczkowska et al., 2010; Jin et al., 2011) |

| Meat redness | Pig | CAPN1 | (Gandolfi et al., 2011) |

| Color scores, fatty acid contents and amino acids | Yanbian Yellow cattle, pig |

CAPN1, CAST | (Skrlep et al., 2010; Jin et al., 2011) |

| Drip loss | Pig | CAST | (Gandolfi et al., 2011) |

| Muscle mass | Ovine | CAPN3 | (Bickerstaffe et al., 2008) |

| Cooking loss and juiciness | Pig | CAST | (Ciobanu et al., 2004) |

As far as we know, CAPNs can cleave limited myofibrillar proteins such as titin, desmin and vinculin, and contribute to the improvement of tenderness, whereas, high levels of CAST are related to decreased proteolysis and increased meat toughness (Kent et al., 2004; Kemp et al., 2010). Originally, it has been difficult to determine which isoform is primarily involved in post-mortem proteolysis, because both CAPN1 and CAPN2 can cleave the same myofibrillar proteins (Huff-Lonergan et al., 1996). Afterwards, several experimental investigations showed that the activity of CAPN1 changed with the post-mortem proteolysis of key myofibrillar proteins rather than CAPN2 (Riley et al., 2003). Furthermore, the role of CAPN1 in post-mortem proteolysis was confirmed in knockout mice, and a consistent result was observed (Koohmaraie et al., 2006). Therefore, it is clear that CAPN1 plays the most significant role in postmortem muscle proteolysis and meat tenderization (Koohmaraie et al., 2006; Kemp et al., 2010), and it is also confirmed that SNPs of CAPN1 in bovines are closely associated with meat tenderness (Page et al., 2002; Page et al., 2004; White et al., 2005; Cafe et al., 2010). While CAPN2 plays a minor role in meat tenderization, at least in bovine and ovine muscle (Veiseth et al., 2001; Camou et al., 2007). The detectable activity decrease in the native form of CAPN2 was investigated during postmortem storage in pork (Pomponio et al., 2008). In addition, a significant association was identified in the CAPN1 3′UTR (c.2151*479C>T) with marbling score (Cheong et al., 2008). Futhermore, a tight correlation has been found between CAPN1 and other meat quality traits such as pH, color scores, fatty acid contents and amino acids in Yanbian Yellow cattle of China (Jin et al., 2011).

CAST inhibits CAPN1 and CAPN2 via the interaction between regions A, C and CAPNs when calcium binds to CAPNs: 40 μmol/L and 250 to 500 μmol/L, respectively (Hanna et al., 2008). The possible mechanism is likely to be that CAPNs degrade CAST via cleaving the weaker inhibitory domains, creating specific peptide fragments that retain inhibitory activity (Mellgren, 2008). A significant evidence as to its role in meat tenderness is observed, that is, a high level of CAST is associated with the decrease in postmortem proteolysis and leads to a poor meat quality (Kent et al., 2004). In addition, the relationship between polymorphisms of CAST and meat tenderness in domestic animals has been confirmed (Casas et al., 2006; Gandolfi et al., 2011). Furthermore, as a meat tenderness biomarker, CAST has been quantified by various methods including ELISA, a surface plasmon resonance and the fluorescence resonance energy transfer-based immunosensors (Zór et al., 2009). Meanwhile, it has been determined that several promoters associated with the 5’exons regulate CAST gene expression (Meyers and Beever, 2008), but the exact regulation mechanism at the transcriptional and translational level of these promoters in CAST among species and their contribution to various meat tenderness remains to be researched further (Kemp et al., 2010).

However, CAPN3 is an important muscle-specific Ca2+-dependent cysteine protease (Suzuki et al., 1995) in the CAPN family. It attracts strong interest with its characteristic protein structure (two insertion sequences, IS1 and IS2) and location (binds to connectin at the N2 line, where proteolysis associated with meat tenderization occurs) (Sorimachi et al., 1989; Taylor et al., 1995; Herasse et al., 1999). However, its precise role in improving meat tenderness is still elusive. Some researchers found indications of a positive role in improving meat tenderness (Ilian M et al., 2001; Ilian et al., 2004a; Kemp et al., 2010), whereas some other researchers have not found such a role (Geesink et al., 2005).

In pigs, shear force measurements were carried out to verify the hypothesis that CAPN3 might influence postmortem proteolysis and meat tenderness on porcine longissimus dorsi (LD) muscle (Parr et al., 1999), but no direct evidence was found linking various levels of CAPN3 abundance and changes in porcine tenderness after 8 d of conditioning. To go further, expression analysis of CAPN3 showed that higher CAPN3 expression was identified in less tender muscles, revealing the indirect involvement of CAPN3 in meat tenderization during postmortem aging (Gandolfi et al., 2011).

There are few available studies on the role of CAPN3 in the tenderness of chicken meat. Previously, Zhang et al. (2009) showed that CAPN3 might serve as a candidate gene for QTL associated with chicken muscle growth and carcass traits. Muscle growth rate is directly related to three critical factors determining meat tenderness; fiber diameters, the proportion of glycolytic fibers and proteolytic potential. In addition, identification of two SNPs in intron 8 and exon 10 of CAPN3 pave the way for further study of CAPN3 in postmortem tenderization in chicken (Zhang et al., 2009).

So far, the role of CAPN3 in meat tenderization during postmortem aging still remains controversial in domestic animals. The possible causes associated with the divergence of opinion may be as follows:

the most available evidence results from various animal species, breeds, age, domesticated background and selection history. In addition, the sample size is too small to estimate the relationship between CAPN3 and meat tenderization accurately.

the difference of methodology may be another important reason leading to the divergence. Perhaps multiple methods and approaches (in vitro and in vivo) are necessary to evaluate the hypothesis. For example, we can use RNA interference or specific inhibition of CAPN3 in domestic animal myoblasts or satellite cells to detect the target protein degradation rate.

INTERACTION AMONG CAPN3, CAPN1 AND CAST

A hypothesis has been provided that there is likely to be an interaction between CAPN1 and CAST due to their strong biological relationship (two genes produce relevant proteins that physically interact in determining meat tenderness) (Casas et al., 2006). Recent crystallographic observations have identified the nature of the interaction between CAST and CAPN, as to the interaction between their unique aspects (regions A, B and C) as protein inhibitors and proteolytic enzymes (Hanna et al., 2008; Moldoveanu et al., 2008). When CAPNs bind to calcium, they are unable to be active while allowing CAST to interact with the enzyme. In addition, CAPNs can degrade CAST via the cleavage of the weaker inhibitory domains, creating specific peptide fragments that retain inhibitory activity (Doumit and Koohmaraie, 1999; Mellgren, 2008).

Although an interaction between CAPN1 and CAST has been detected affects the Warner-Bratzler shear Force in meat samples from a cattle population, this significant interaction needs further investigation (Casas et al., 2006; Morris et al., 2006).

In addition, CAPNs can play a role in postmortem proteolysis. As we know, CAPN3 binds to connectin (or titin) at the N2 line, where proteolysis associated with meat tenderization occurs (Sorimachi et al., 1989; Taylor et al., 1995), while CAPN1 can degrade the N2 line for meat tenderization (Goll et al., 1991). Degradation of N2 line lead to inability of CAPN3 to anchor to connectin and then too much free CAPN3 is generated, which is toxic to muscle cells (Beckmann and Spencer, 2008).

POSSIBLE MECHANISM OF CAPN3 IN IMPROVING MEAT TENDERNESS

Possible pathways involved which CAPN3 improves meat tenderization

Myofibril type composition: The composition of myofibre type is well-accepted as a vital factor responsible for the variation in meat quality (Karlsson et al., 1999). Three types have been classified via conventional histochemistry in adult skeletal muscle, i.e. types I, IIA and IIB fibres (Brooke and Kaiser, 1970). However, recent studies have demonstrated that a molecular basis of fibre typing based on myosin heavy chains (MyHC) (Larzul et al., 1997; Lefaucheur et al., 2004), would be more reasonable. Four isoforms have been identified, respectively, types I, IIa, IIx and IIb isoforms (Bär and Pette, 1988; Schiaffino et al., 1989). The diameter increases in the rank order I=IIa<IIx<IIb or IIa<I<IIx<IIb (Lefaucheur, 2010), which determined fiber cross-sectional area (CSA). The meat tenderness would be fine, when myofibre was thin and the density was high with higher fat content (Wang and Li, 1994). Therefore, type I and IIa have higher tenderness than IIx and IIb. Moreover, the four types are dynamic structures which exhibit high plasticity and undergo type shift in accordance with an obligatory pathway I→IIa→IIx→IIb (Schiaffino and Reggiani, 1994; Pette and Staron, 2000).

In vitro study has identified that CAPN3 can participate in the muscular regeneration process via decreasing the transcriptional activity of MyOD (Stuelsatz et al., 2010), a protein with a key role in regulating muscle differentiation. Meanwhile, MyOD is expressed in myosin heavy chain type IIx-expressing (MyHC-2x-expressing) muscle but less in non-MyHC-2x-expressing muscle (Muroya et al., 2002). Skeletal muscle is characterized by fast and slow muscle based on the expression pattern of MyHC isoforms in muscle fibres (Schiaffino and Reggiani, 1996). A previous study found that MyOD knockout mice showed a shift of MyHC isoform expression toward a slower phenotype (Hughes, 1997). Thus, changes of the expression ratio of MyHC isofoms may contribute to the transformation of fibre types. Consequently, the tenderness would be improved if the muscle lacks MyOD.

Calcium ion: Calcium ions can improve tenderness when they are introduced into meat by means of injection, infusion and pickling for a short time with the concentration of 0.3 mol/L solutions (CaCl2) (Morgan et al., 1991; Whipple and Koohmaraie, 1991; Koohmaraie, 1992; Boleman et al., 1995; Rees et al., 2002). Infusing calcium can increase tenderness and increased proteolysis or increased post-mortem glycolysis can all be the potential causes. Nevertheless, CAPN3, especially those associated with the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) membrane (Kramerova et al., 2006), has a confirmed role in regulating calcium release in skeletal muscle in the maintenance of a protein complex (AldoA and RyR) (Kramerova et al., 2008). Once calcium release is significantly reduced, the concentration of calcium ions in the sarcoplasm will be decreased. Consequently, the activation of Ca2+-dependent proteolytic systems such as the CAPN system will be influenced and the key proteins involved in tenderization will not be degraded or modified. It was reported that CAPN1 was inactive when the Ca2+ concentration in sarcoplasm was below 10−7 mol after slaughter (Dransfield, 1994). Finally, structural changes of myofibril or collagen will not occur, when the degree of degradation is insufficient (Morgan et al., 1991). Thereby, meat tenderness can not be improved.

Tenderization-related protein: Early researches show that final tenderness is determined by the rate of proteolysis and weakening of myofibril structure (Taylor et al., 1995; Faulkner et al., 2000). The degradation of key proteins, for instance, titin, nebulin, filamin, desmin and troponin-T, are responsible for tenderization during aging (Koohmaraie, 1992; Huff-Lonergan et al., 1996; Wheeler et al., 2000; Lametsch et al., 2002). According to the theory of enzymatic meat tenderization, the CAPN system can play a role in postmortem proteolysis and meat tenderness. Recent studies have indicated that CAPN3 could cleave titin (related to the remodeling of sarcomere), filamin C (the Z-disc of the myofibrillar apparatus by binding directly to the Z-disc proteins FATZ (a filamin-, actinin-, and telethonin-binding protein of the Z-disc of skeletal muscle) and myotilin) and nebulin (the autolysis of myofibrillar CAPN3 and CAPN1), respectively (Faulkner et al., 2000; Van Der Ven et al., 2000; Guyon et al., 2003; Salmikangas et al., 2003; Ilian et al., 2004a; Kramerova et al., 2004). From the above studies, a role of CAPN3 in improving meat tenderness is inferred from modulating the proteolysis of key myofibrillar proteins.

Other factors: ATP is the key element that affects the meat aging. Kramerova et al. (2009) identified that mitochondria were dysfunctional in the CAPN3 knockout (C3KO) mice and this then lead to oxidative stress and ATP deficiency. ATP provides the energy for shortening the myofibril which results in mucle contraction in living cells (Goll et al., 1984). After slaughter, ATP can not be supplied and the shorten process of myofibrils is influnenced. Meat tenderness is affected by the amount of shortening of the myofibrils. It will be tougher, if the myofibril is shorter (Locker and Hagyard, 1963). Howerver, if the muscle stores much more ATP before slaughter, it will take a longer time to deplete the ATP. In that way, the muscle tends to produce less shortened myofibrils. The converse occurs if there is little stored ATP.

In addition, it is reported that CAPN3 can cleave titin in vitro. Titin serves as a template and molecular ruler for thick filament assembling and sarcomere formation and plays a central role in myofibrillogenesis (Kramerova et al., 2004). Specific degradation of titin causes an increase in the myofilament lattice spacing (Cazorla et al., 2001). With the intact proteinaceous connections associated with cell membrane, the increased spacing makes it possible for the myofibril to hold much water, thereby reduce the drip loss (Wang and Ramirez-Mitchell, 1983; Huff-Lonergan and Lonergan, 2005). Ultimately, meat juiceness will be improved.

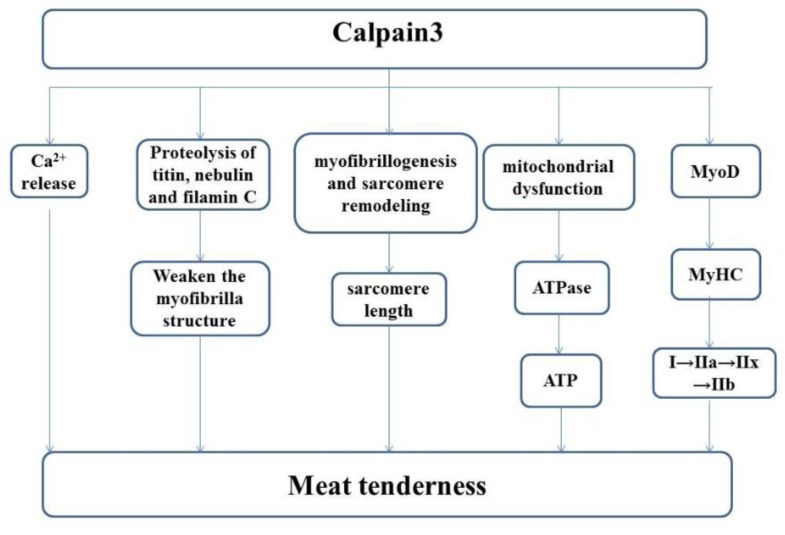

So far, the regulation role of CAPN3 in meat tenderization is still controversial. Causes of the divergence are diverse. In the current review, possible pathways of CAPN3 involved in improving meat tenderness are speculated (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Possible mechanism of CAPN3 in meat tenderization.

CONCLUSION AND PROSPECTIVES

Meat tenderness is a multifactorial economic trait, involving heredity, nutrition and environment factors. In spite of this, several researches have been conducted in domestic animals based on the theory of enzymatic meat tenderization especially the CAPN protease system. So far, it is clear that CAPN1 and CAST genes are responsible for postmortem proteolysis, but the role of CAPN3, a member of CAPN family, in postmortem meat tenderization is unclear. In the present review, the role of CAPN1, CAPN3, CAST in postmortem meat aging is discussed, and four possible pathways of CAPN3 are suggested based on the recent findings, however, the precise regulation role of CAPN3 remains to be investigated and validated further involving multi-methods with sufficiently large sample sizes.

If CAPN3 does contribute to postmortem meat tenderization, and the identified SNP markers linked to meat tenderness developed for the CAPN1, CAPN3 and CAST genes, they can ultimately be applied in identifying animals with the genetic potential to produce better meat, i.e. marker-assisted breeding programmes. In addition, the various protein isoforms from CAST are likely to be responsible for variations in meat tenderness.

REFERENCES

- Bär A, Pette D. Three fast myosin heavy chains in adult rat skeletal muscle. FEBS Lett. 1988;235:153–155. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(88)81253-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbut S, Sosnicki AA, Lonergan SM, Knapp T, Ciobanu DC, Gatcliffe LJ, Huff-Lonergan E, Wilson EW. Progress in reducing the pale, soft and exudative (PSE) problem in pork and poultry meat. Meat Sci. 2008;79:46–63. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2007.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barendse W, Harrison BE, Bunch RJ, Thomas MB. Variation at the calpain 3 gene is associated with meat tenderness in zebu and composite breeds of cattle. BMC Genet. 2008;9:41. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-9-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckmann JS, Spencer M. Calpain 3, the “gatekeeper” of proper sarcomere assembly, turnover and maintenance. Neuromuscul Disord. 2008;18:913–921. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard C, Cassar-Malek I, Cunff ML, Dubroeucq H, Renand G, Hocquette JF. New indicators of beef sensory quality revealed by expression of specific genes. J Agric Food Chem. 2007;55:5229–5237. doi: 10.1021/jf063372l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickerstaffe R, Gately K, Morton JD. The association between polymorphic variations in calpain 3 with the yield and tenderness of retail lamb meat cuts. Proceedings of 54th International Congress of Meat Science and Technology; Helsinki, Finland. 2008. pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard H, Grochulski P, Li Y, Arthur JSC, Davies PL, Elce JS, Cygler M. Structure of a calpain Ca2+-binding domain reveals a novel EF-hand and Ca2+-induced conformational changes. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4:532–538. doi: 10.1038/nsb0797-532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard H, Li Y, Cygler M, Kay CM, Arthur JSC, Davies PL, Elce JS. Ca2+-binding domain VI of rat calpain is a homodimer in solution: Hydrodynamic, crystallization and preliminary X-ray diffraction studies. Protein Sci. 1996;5:535–537. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560050317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boleman SJ, Boleman SL, Bidner TD, McMillin KW, Monlezun CJ. Effects of postmortem time of calcium chloride injection on beef tenderness and drip, cooking, and total loss. Meat Sci. 1995;39:35–41. doi: 10.1016/0309-1740(95)80005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooke MH, Kaiser KK. Muscle fiber types: How many and what kind? Arch Neurol. 1970;23:369–379. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1970.00480280083010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brulé C, Dargelos E, Diallo R, Listrat A, Béchet D, Cottin P, Poussard S. Proteomic study of calpain interacting proteins during skeletal muscle aging. Biochimie. 2010;92:1923–1933. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cafe LM, McIntyre BL, Robinson DL, Geesink GH, Barendse W, Pethick DW, Thompson JM, Greenwood PL. Production and processing studies on calpain-system gene markers for tenderness in brahman cattle:1. Growth, efficiency, temperament, and carcass characteristics. J Anim Sci. 2010;88:3047–3058. doi: 10.2527/jas.2009-2678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camou JP, Marchello JA, Thompson VF, Mares SW, Goll DE. Effect of postmortem storage on activity of μ-and m-calpain in five bovine muscles. J Anim Sci. 2007;85:2670–2681. doi: 10.2527/jas.2007-0164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casas E, White SN, Wheeler TL, Shackelford SD, Koohmaraie M, Riley DG, Chase CC, Jr, Johnson DD, Smith TPL. Effects of calpastatin and μ-calpain markers in beef cattle on tenderness traits. J Anim Sci. 2006;84:520–525. doi: 10.2527/2006.843520x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cazorla O, Wu Y, Irving TC, Granzier H. Titin-based modulation of calciumsensitivity of active tension in mouse skinned cardiac myocytes. Circ Res. 2001;88:1028–1035. doi: 10.1161/hh1001.090876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheong HS, Yoon DH, Park BL, Kim LH, Bae JS, Namgoong S, Lee HW, Han CS, Kim JO, Cheong IC. A single nucleotide polymorphism in CAPN 1 associated with marbling score in Korean cattle. BMC Genet. 2008;9:33. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-9-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciobanu DC, Bastiaansen JWM, Lonergan SM, Thomsen H, Dekkers JCM, Plastow GS, Rothschild MF. New alleles in calpastatin gene are associated with meat quality traits in pigs. J Anim Sci. 2004;82:2829–2839. doi: 10.2527/2004.82102829x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cong M, Thompson VF, Goll DE, Antin PB. The bovine calpastatin gene promoter and a new N-terminal region of the protein are targets for cAMP-dependent protein kinase activity. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:660–666. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.1.660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corva P, Soria L, Schor A, Villarreal E, Cenci MP, Motter M, Mezzadra C, Melucci L, Miquel C, Paván E, Depetris G, Santini F, Naón JG. Association of CAPN1 and CAST gene polymorphisms with meat tenderness in Bos Taurus beef cattle from Argentina. Genet Mol Biol. 2007;30:1064–1069. [Google Scholar]

- Costello S, O’Doherty E, Troy DJ, Ernst CW, Kim KS, Stapleton P, Sweeney T, Mullen AM. Association of polymorphisms in the calpain I, calpain II and growth hormone genes with tenderness in bovine M. Longissimus Dorsi. Meat Sci. 2007;75:551–557. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2006.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croall DE, DeMartino GN. Calcium-activated neutral protease (calpain) system: Structure, function, and regulation. Physiol Rev. 1991;71:813–847. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1991.71.3.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croall DE, Ersfeld K. The calpains: Modular designs and functional diversity. Genome Biol. 2007;8:218. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-6-218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Destefanis G, Brugiapaglia A, Barge MT, Dal Molin E. Relationship between beef consumer tenderness perception and warner-bratzler shear force. Meat Sci. 2008;78:153–156. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2007.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doumit ME, Koohmaraie M. Immunoblot analysis of calpastatin degradation: Evidence for cleavage by calpain in postmortem muscle. J Anim Sci. 1999;77:1467–1473. doi: 10.2527/1999.7761467x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dransfield E. Modelling post-mortem tenderization-V: Inactivation of calpains. Meat Sci. 1994;37:391–409. doi: 10.1016/0309-1740(94)90055-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutaud D, Aubry L, Sentandreu MA, Ouali A. Bovine muscle 20S proteasome: I. Simple purification Procedure and Enzymatic Characterization in Relation with Postmortem Conditions. Meat Sci. 2006;74:327–336. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2006.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg D, Weiss RM, Terwilliger TC, Wilcox W. Hydrophobic moments and protein structure. Faraday Symp Chem Soc. 1982;17:109–120. [Google Scholar]

- Emori Y, Kawasaki H, Imajoh S, Kawashima S, Suzuki K. Isolation and sequence analysis of cDNA clones for the small subunit of rabbit calcium-dependent protease. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:9472–9476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fürst DO, Osborn M, Nave R, Weber K. The organization of titin filaments in the half-sarcomere revealed by monoclonal antibodies in immunoelectron microscopy: A map of ten nonrepetitive epitopes starting at the Z line extends close to the M line. J Cell Biol. 1988;106:1563–1572. doi: 10.1083/jcb.106.5.1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner G, Pallavicini A, Comelli A, Salamon M, Bortoletto G, Ievolella C, Trevisan S, Koji S, Dalla Vecchia F, Laveder P. FATZ, a filamin-, actinin-, and telethonin-binding protein of the Z-disc of skeletal muscle. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:41234–41242. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007493200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fougerousse F, Durand M, Suel L, Pourquié O, Delezoide AL, Romero NB, Abitbol M, Beckmann JS. Expression of genes (CAPN3, SGCA, SGCB, and TTN) involved in progressive muscular dystrophies during early human development. Genomics. 1998;48:145–156. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.5160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandolfi G, Pomponio L, Ertbjerg P, Karlsson AH, Nanni Costa L, Lametsch R, Russo V, Davoli R. Investigation on CAST, CAPN1 and CAPN3 porcine gene polymorphisms and expression in relation to post-mortem calpain activity in muscle and meat quality. Meat Sci. 2011;88:694–700. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2011.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia Diaz BE, Gauthier S, Davies PL. Ca2+ dependency of calpain 3 (p94) activation. Biochemistry. 2006;45:3714–3722. doi: 10.1021/bi051917j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geesink GH, Taylor RG, Koohmaraie M. Calpain 3/p94 is not involved in postmortem proteolysis. J Anim Sci. 2005;83:1646–1652. doi: 10.2527/2005.8371646x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goll DE, Robson RM, Stromer MH. Skeletal muscle, nervous system, temperature regulation, and special senses. In: Swensen MJ, editor. Duke's physiol domestic anim. Ithaca, N.Y: Cornell University Press; 1984. pp. 548–580. [Google Scholar]

- Goll DE, Dayton WR, Singh I, Robson RM. Studies of the alpha-actinin/actin interaction in the Z-Disk by using calpain. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:8501–8510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goll DE, Otsuka Y, Nagainis PA, Shannon JD, Sathe SK, Muguruma M. Role of muscle proteinases in maintenance of muscle integrity and mass. J Food Biochem. 1983;7:137–177. [Google Scholar]

- Goll DE, Thompson VF, Li H, Wei W, Cong J. The calpain system. Physiol Rev. 2003;83:731–801. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00029.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollasch M, Nelson MT. Voltage-dependent Ca2+channels in arterial smooth muscle cells. Kidney Blood Press Res. 1997;20:355–371. doi: 10.1159/000174250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grobbel JP, Dikeman ME, Hunt MC, Milliken GA. Effects of packaging atmospheres on beef instrumental tenderness, fresh color stability, and internal cooked color. J Anim Sci. 2008;86:1191–1199. doi: 10.2527/jas.2007-0479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guroff G. A neutral, calcium-activated proteinase from the soluble fraction of rat brain. J Biol Chem. 1964;239:149–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyon JR, Kudryashova E, Potts A, Dalkilic I, Brosius MA, Thompson TG, Beckmann JS, Kunkel LM, Spencer MJ. Calpain 3 cleaves filamin C and regulates its ability to interact with γ-and δ-sarcoglycans. Muscle Nerve. 2003;28:472–483. doi: 10.1002/mus.10465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna RA, Campbell RL, Davies PL. Calcium-bound structure of calpain and its mechanism of inhibition by calpastatin. Nature. 2008;456:409–412. doi: 10.1038/nature07451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herasse M, Ono Y, Fougerousse F, Kimura E, Stockholm D, Beley C, Montarras D, Sorimachi CH, Suzuki K, Beckmann JS, Richard I. Expression and functional characteristics of calpain 3 isoforms generated through tissue-specific transcriptional and posttranscriptional events. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:4047–4055. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.6.4047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosfield CM, Elce JS, Davies PL, Jia ZC. Crystal structure of calpain reveals the structural basis for Ca2+-dependent protease activity and a novel mode of enzyme activation. EMBO J. 1999;18:6880–6889. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.24.6880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huff-Lonergan E, Lonergan SM. Mechanisms of water-holding capacity of meat: The role of postmortem biochemical and structural changes. Meat Sci. 2005;71:194–204. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2005.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huff-Lonergan E, Mitsuhashi T, Beekman DD, Parrish F, Jr, Olson DG, Robson RM. Proteolysis of specific muscle structural proteins by mu-calpain at low pH and temperature is similar to degradation in postmortem bovine muscle. J Anim Sci. 1996;74:993–1008. doi: 10.2527/1996.745993x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huff-Lonergan E, Lonergan SM. Postmortem mechanisms of meat tenderization: The roles of the structural proteins and the calpain system. In: Xiong YL, Ho C-T, Shahidi F, editors. Quality attributes muscle foods. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 1999. pp. 229–251. [Google Scholar]

- Huff-Lonergan E, Zhang W, Lonergan SM. Biochemistry of postmortem muscle-Lessons on mechanisms of meat tenderization. Meat Sci. 2010;86:184–195. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes SM, Koishi K, Rudnicki M, Maggs AM. MyoD protein differentially accumulated in fast and slow skeletal muscle fibers and required for normal fiber type balance in rodents. Mech Dev. 1997;61:151–163. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(96)00631-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang IH, Devine CE, Hopkins DL. The biochemical and physical effects of electrical stimulation on beef and sheep meat tenderness. Meat Sci. 2003;65:677–691. doi: 10.1016/S0309-1740(02)00271-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilian MA, Bekhit AED, Bickerstaffe R. The relationship between meat tenderization, myofibril fragmentation and autolysis of calpain 3 during post-mortem aging. Meat Sci. 2004a;66:387–397. doi: 10.1016/S0309-1740(03)00125-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilian MA, Bekhit AEDA, Stevenson B, Morton JD, Isherwood P, Bickerstaffe R. Up-and down-regulation of longissimus tenderness parallels changes in the myofibril-bound calpain 3 protein. Meat Sci. 2004b;67:433–445. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2003.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilian MA, Bickerstaffe R, Greaser ML. Postmortem changes in myofibrillar-bound calpain 3 revealed by immunofluorescence microscopy. Meat Sci. 2004c;66:231–240. doi: 10.1016/S0309-1740(03)00096-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilian MA, Morton JD, Bekhit AED, Roberts N, Palmer B, Sorimachi S, Bickerstaffe R. Effect of preslaughter feed withdrawal period on longissimus tenderness and the expression of calpains in the ovine. J Agric Food Chem. 2001;49:1990–1998. doi: 10.1021/jf0010026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilian MA, Morton JD, Kent MP, Le Couteur CE, Hickford J, Cowley R, Bickerstaffe R. Intermuscular variation in tenderness: Association with the ubiquitous and muscle-specific calpains. J Anim Sci. 2001;79:122–132. doi: 10.2527/2001.791122x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imajoh S, Aoki K, Ohno S, Emori Y, Kawasaki H, Sugihara H, Suzuki K. Molecular cloning of the cDNA for the large subunit of the high-calcium-requiring form of human calcium-activated neutral protease. Biochemistry. 1988;27:8122–8128. doi: 10.1021/bi00421a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida S, Emori Y, Suzuki K. Rat calpastatin has diverged primary sequence from other mammalian calpastatins but retains functionality important sequences. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1088:436–438. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(91)90139-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin X, Zhang LC, Li ZH, Liu XH, Jin HG, Yan CG. Association of polymorphisms in the calpain I gene with meat quality traits in Yanbian yellow cattle of China. Asian-Aust J Anim Sci. 2011;24:9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson AH, Klont RE, Fernandez X. Skeletal muscle fibres as factors for pork quality. Livest Prod Sci. 1999;60:255–269. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp CM, Sensky PL, Bardsley RG, Buttery PJ, Parr T. Tenderness-An enzymatic view. Meat Sci. 2010;84:248–256. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent MP, Spencer MJ, Koohmaraie M. Postmortem proteolysis is reduced in transgenic mice overexpressing calpastatin. J Anim Sci. 2004;82:794–801. doi: 10.2527/2004.823794x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinbara K, Ishiura S, Tomioka S, Sorimachi H, Jeong SY, Amano S, Kawasaki H, Kolmerer B, Kimura S, Labeit S, Suzuki K. Purification of native p94, a muscle-specific calpain, and characterization of its autolysis. Biochem J. 1998;335:589–596. doi: 10.1042/bj3350589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- König N, Raynaud F, Feane H, Durand M, Mestre-Francès NN, Rossel M, Ouali A, Benyamin Y. Calpain 3 is expressed in astrocytes of rat and microcebus brain. J Chem Neuroanat. 2003;25:129–136. doi: 10.1016/s0891-0618(02)00102-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koohmaraie M. The role of Ca2+-dependent proteases (calpains) in post mortem proteolysis and meat tenderness. Biochimie. 1992;74:239–245. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(92)90122-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koohmaraie M. Biochemical factors regulating the toughening and tenderization processes of meat. Meat Sci. 1996;43(Supp. 1):193–201. doi: 10.1016/0309-1740(96)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koohmaraie M, Chishti AH, Geesink GH, Kucha S. μ-Calpain is essential for postmortem proteolysis of muscle proteins. J Anim Sci. 2006;84:2834–2840. doi: 10.2527/jas.2006-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koohmaraie M, Doumit ME, Wheeler TL. Meat toughening does not occur when rigor shortening is prevented. J Anim Sci. 1996;74:2935–2942. doi: 10.2527/1996.74122935x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koohmaraie M, Geesink GH. Contribution of postmortem muscle biochemistry to the delivery of consistent meat quality with particular focus on the calpain system. Meat Sci. 2006;74:34–43. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2006.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koohmaraie M, Seideman SC, Schollmeyer JE, Dutson TR, Babiker AS. Factors associated with the tenderness of three bovine muscles. J Food Sci. 1988;53:407–410. [Google Scholar]

- Koohmaraie M, Whipple G, Kretchmar DH, Crouse JD, Mersmann HJ. Postmortem proteolysis in longissimus muscle from beef, lamb and pork carcasses. J Anim Sci. 1991;69:617–624. doi: 10.2527/1991.692617x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramerova I, Kudryashova E, Tidball JG, Spencer MJ. Null mutation of calpain 3 (p94) in mice causes abnormal sarcomere formation in vivo and in vitro. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:1373–1388. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramerova I, Kudryashova E, Wu B, Spencer MJ. Regulation of the M-cadherin-beta-catenin complex by calpain 3 during terminal stages of myogenic differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:8437–8447. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01296-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramerova I, Kudryashova E, Wu B, Ottenheijm C, Granzier H, Spencer MJ. Novel role of calpain-3 in the triad-associated protein complex regulating calcium release in skeletal muscle. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:3271–3280. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramerova I, Kudryashova E, Wu B, Germain S, Vandenborne K, Romain N, Haller RG, Verity MA, Spencer MJ. Mitochondrial abnormalities, energy deficit and oxidative stress are features of calpain 3 deficiency in skeletal muscle. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:3194–3205. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lametsch R, Roepstorff P, Bendixen E. Identification of protein degradation during post-mortem storage of pig meat. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50:5508–5512. doi: 10.1021/jf025555n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larzul C, Lefaucheur L, Ecolan P, Gogue J, Talmant A, Sellier P, Le Roy P, Monin G. Phenotypic and genetic parameters for longissimus muscle fiber characteristics in relation to growth, carcass, and meat quality traits in large white pigs. J Anim Sci. 1997;75:3126–3137. doi: 10.2527/1997.75123126x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HL, Santé-Lhoutellier V, Vigouroux S, Briand Y, Briand M. Role of calpains in postmortem proteolysis in chicken muscle. Poult Sci. 2008;87:2126–2132. doi: 10.3382/ps.2007-00296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefaucheur L. A second look into fibre typing-relation to meat quality. Meat Sci. 2010;84:257–270. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefaucheur L, Milan D, Ecolan P, Le Callennec C. Myosin heavy chain composition of different skeletal muscles in large white and meishan pigs. J Anim Sci. 2004;82:1931–1941. doi: 10.2527/2004.8271931x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin GD, Chattopadhyay D, Maki M, Wang KK, Carson M, Jin L, Yuen PW, Takano E, Hatanaka M, DeLucas LJ, Narayana SV. Crystal structure of calcium bound domain VI of calpain at 1.9 A resolution and its role in enzyme assembly, regulation, and inhibitor binding. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4:539–547. doi: 10.1038/nsb0797-539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindholm-Perry AK, Rohrer GA, Holl JW, Shackelford SD, Wheeler TL, Koohmaraie M, Nonneman D. Relationships among calpastatin single nucleotide polymorphisms, calpastatin expression and tenderness in pork longissimus. Anim Genet. 2009;40:713–721. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2052.2009.01903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locker RH, Hagyard CJ. A cold shortening effect in beef muscles. J Sci Food Agric. 1963;14:787–793. [Google Scholar]

- Ma H, Fukiage C, Azuma M, Shearer TR. Cloning and expression of mRNA for calpain Lp82 from rat lens: Splice variant of p94. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998;39:454–461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayes PA. Harpers biochemistry. 28th edn. New Jersy: Appleton and Lange Publishing Division of Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs; 1993. Metabolism of glycogen; pp. 50–400. [Google Scholar]

- McCormick RJ. Collagen, applied muscle biology and meat science. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 2009. pp. 129–148. [Google Scholar]

- Mellgren RL. Structural biology: Enzyme knocked for a loop. Nature. 2008;456:337–338. doi: 10.1038/456337a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melody JL, Lonergan SM, Rowe LJ, Huiatt TW, Mayes MS, Huff-Lonergan E. Early postmortem biochemical factors influence tenderness and water holding capacity of three porcine muscles. J Anim Sci. 2004;82:1195–1205. doi: 10.2527/2004.8241195x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers SN, Beever JE. Investigating the genetic basis of pork tenderness: Genomic analysis of porcine CAST. Anim Genet. 2008;39:531–543. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2052.2008.01765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeller SJ, Miller RK, Edwards KK, Zerby HN, Logan KE, Aldredge TL, Stahl CA, Boggess M, Box-Steffensmeier JM. Consumer perceptions of pork eating quality as affected by pork quality attributes and end-point cooked temperature. Meat Sci. 2010;84:14–22. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2009.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moldoveanu T, Gehring K, Green DR. Concerted multi-pronged attack by calpastatin to occlude the catalytic cleft of heterodimeric calpains. Nature. 2008;456:404–408. doi: 10.1038/nature07353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan JB, Miller RK, Mendez FM, Hale DS, Savell JW. Using calcium chloride injection to improve tenderness of beef from mature cows. J Anim Sci. 1991;69:4469–4476. doi: 10.2527/1991.69114469x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris CA, Cullen NG, Hickey SM, Dobbie M, Veenvliet BA, Manley TR, Pitchford WS, Kruk ZA, Bottema CDK, Wilson T. Genotypic effects of calpain 1 and calpastatin on the tenderness of cooked M. Longissimus Dorsi steaks from Jersey×Limousin, Angus and Hereford-cross cattle. Anim Genet. 2006;37:411–414. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2052.2006.01483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moudilou EN, Mouterfi N, Exbrayat JM, Brun C. Calpains expression during Xenopus Laevis development. Tissue Cell. 2010;42:275–281. doi: 10.1016/j.tice.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muroya S, Nakajima I, Chikuni K. Related expression of MyoD and Myf5 with myosin heavy chain isoform types in bovine adult skeletal muscles. Zool Sci. 2002;19:755–761. doi: 10.2108/zsj.19.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neath KE, Del Barrio AN, Lapitan RM, Herrera JRV, Cruz LC, Fujihara T, Muroya S, Chikuni K, Hirabayashi M, Kanai Y. Protease activity higher in postmortem water buffalo meat than Brahman beef. Meat Sci. 2007;77:389–396. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2007.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno S, Emori Y, Suzuki E. Nucleotide sequence of a cDNA coding for the small subunit of human calcium-dependent protease. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986;14:5559. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno S, Minoshima S, Kudoh J, Fukuyama R, Shimizu Y, Ohmi-Imajohs S, Shimizu N, Suzuki K. Four genes for the calpain family locate on four distinct human chromosomes. Cytogenet Genome Res. 1990;53:225–229. doi: 10.1159/000132937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono Y, Kakinuma K, Torii F, Irie A, Nakagawa K, Labeit S, Abe K, Suzuki K, Sorimachi H. Possible regulation of the conventional calpain system by skeletal muscle-specific calpain, p94/calpain 3. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:2761–2771. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308789200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono Y, Ojima K, Torii F, Takaya E, Doi N, Nakagawa K, Hata S, Abe K, Sorimachi H. Skeletal muscle-specific calpain is an intracellular Na+-dependent protease. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:22986–22998. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.126946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page BT, Casas E, Heaton MP, Cullen NG, Hyndman DL, Morris CA, Crawford AM, Wheeler TL, Koohmaraie M, Keele JW, Smith TPL. Evaluation of single-nucleotide polymorphisms in CAPN1 for association with meat tenderness in cattle. J Anim Sci. 2002;80:3077–3085. doi: 10.2527/2002.80123077x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page BT, Casas E, Quaas RL, Thallman RM, Wheeler TL, Shackelford SD, Koohmaraie M, White SN, Bennett GL, Keele JW, Dikeman ME, Smith TP. Association of markers in the bovine CAPN1 gene with meat tenderness in large crossbred populations that sample influential industry sires. J Anim Sci. 2004;82:3474–3481. doi: 10.2527/2004.82123474x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parr T, Sensky PL, Scothern GP, Bardsley RG, Buttery PJ, Wood JD, Warkup C. Relationship between skeletal muscle-specific calpain and tenderness of conditioned porcine longissimus muscle. J Anim Sci. 1999;77:661–668. doi: 10.2527/1999.773661x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peaston AE, Whitelaw E. Epigenetics and phenotypic variation in mammals. Mamm Genome. 2006;17:365–374. doi: 10.1007/s00335-005-0180-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pette D, Staron RS. Myosin isoforms, muscle fiber types, and transitions. Microsc Res Techniq. 2000;50:500–509. doi: 10.1002/1097-0029(20000915)50:6<500::AID-JEMT7>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto LFB, Ferraz JBS, Meirelles FV, Eler JP, Rezende FM, Carvalho ME, Almeida HB, Silva RCG. Association of SNPs on CAPN1 and CAST genes with tenderness in Nellore cattle. Genet Mol Res. 2010;9:1431–1442. doi: 10.4238/vol9-3gmr881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomponio L, Lametsch R, Karlsson AH, Costa LN, Grossi A, Ertbjerg P. Evidence for post-mortem m-calpain autolysis in porcine muscle. Meat Sci. 2008;80:761–764. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2008.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poussard S, Duvert M, Balcerzak D, Ramassamy S, Brustis JJ, Cottin P, Ducastaing A. Evidence for implication of muscle-specific calpain (p94) in myofibrillar integrity. Cell Growth Differ. 1996;7:1461–1469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravulapalli R, Campbell R, Gauthier SY, Dhe-Paganon S, Davies PL. Distinguishing between calpain heterodimerization and homodimerization. FEBS J. 2009;276:973–982. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravulapalli R, Garcia Diaz B, Campbell RL, Davies PL. Homodimerization of calpain 3 penta-EF-hand domain. Biochem J. 2005;388:585–591. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees MP, Trout GR, Warner RD. Effect of calcium infusion on tenderness and ageing rate of pork M. Longissimus Thoracis et Lumborum after accelerated boning. Meat Sci. 2002;61:169–179. doi: 10.1016/s0309-1740(01)00181-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley DG, Chase CC, Pringle TD, West RL, Johnson DD, Olson TA, Hammond AC, Coleman SW. Effect of sire on μ-and m-calpain activity and rate of tenderization as indicated by myofibril fragmentation indices of steaks from Brahman cattle. J Anim Sci. 2003;81:2440–2447. doi: 10.2527/2003.81102440x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts N, Palmer B, Hickford JGH, Bickerstaffe R. PCR-SSCP in the ovine calpastatin gene. Anim Genet. 1996;27:211. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2052.1996.tb00955.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmikangas P, Van der Ven PFM, Lalowski M, Taivainen A, Zhao F, Suila H, Schr der R, Lappalainen P, Fürst DO. Myotilin, the limb-girdle muscular dystrophy 1A (LGMD1A) protein, cross-links actin filaments and controls sarcomere assembly. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:189–203. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenkel FS, Miller SP, Jiang Z, Mandell IB, Ye X, Li H, Wilton JW. Association of a single nucleotide polymorphism in the calpastatin gene with carcass and meat quality traits of beef cattle. J Anim Sci. 2006;84:291–299. doi: 10.2527/2006.842291x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiaffino S, Gorza L, Sartore S, Saggin L, Ausoni S, Vianello M, Gundersen K, LØmo T. Three myosin heavy chain isoforms in type 2 skeletal muscle fibres. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 1989;10:197–205. doi: 10.1007/BF01739810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiaffino S, Reggiani C. Myosin isoforms in mammalian skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol. 1994;77:493–501. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1994.77.2.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiaffino S, Reggiani C. Molecular diversity of myofibrillar proteins: Gene regulation and functional significance. Physiol Rev. 1996;76:371–423. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1996.76.2.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seideman SC, Cross HR, Crouse JD. Variations in the sensory properties of beef as affected by sex condition, muscle and postmortem aging. J Food Qual. 1989;12:39–58. [Google Scholar]

- Sentandreu MA, Coulis G, Ouali A. Role of muscle endopeptidases and their inhibitors in meat tenderness. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2002;13:400–421. [Google Scholar]

- Shackelford SD, Wheeler TL, Meade MK, Reagan JO, Byrnes BL, Koohmaraie M. Consumer impressions of tender select beef. J Anim Sci. 2001;79:2605–2614. doi: 10.2527/2001.79102605x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieczkowska H, Zybert A, Krzecio E, Antosik K, Kocwin-Podsiadla M, Pierzchala M, Urbanski P. The expression of genes PKM2 and CAST in the muscle tissue of pigs differentiated by glycolytic potential and drip loss, with reference to the genetic group. Meat Sci. 2010;84:137–142. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2009.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons NJ, Daly CC, Cummings TL, Morgan SK, Johnson NV, Lombard A. Reassessing the principles of electrical stimulation. Meat Sci. 2008;80:110–122. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Škrlep M, Čandek-Potokar M, Kavar T, Žlender B, HortÓs M, Gou P, Arnau J, Evans G, Southwood O, Diestre A, Robert N. Association of PRKAG3 and CAST genetic polymorphisms with traits of interest in dry-cured ham production: Comparative study in France, Slovenia and Spain. Livest Sci. 2010;128:60–66. [Google Scholar]

- Sorimachi H, Imajoh-Ohmi S, Emori Y, Kawasaki H, Ohno S, Minami Y, Suzuki K. Molecular cloning of a novel mammalian calcium-dependent protease distinct from both m-and mu-types. Specific expression of the mRNA in skeletal muscle. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:20106–20111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorimachi H, Kinbara K, Kimura S, Takahashi M, Ishiura S, Sasagawa N, Sorimachi N, Shimada H, Tagawa K, Maruyama K, Suzuki K. Muscle-specific calpain, p94, responsible for limb girdle muscular dystrophy type 2A, associates with connectin through IS2, a p94-specific sequence. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:31158–31162. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.52.31158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorimachi H, Toyama-Sorimachi N, Saido TC, Kawasaki H, Sugita H, Miyasaka M, Arahata K, Ishiura S, Suzuki K. Muscle-specific calpain, p94, is degraded by autolysis immediately after translation, resulting in disappearance from muscle. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:10593–10605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strobl S, Fernandez-Catalan C, Braun M, Huber R, Masumoto H, Nakagawa K, Irie A, Sorimachi H, Bourenkow G, Bartunik H, Suzuki K, Bode W. The crystal structure of calcium-free human m-calpain suggests an electrostatic switch mechanism for activation by calcium. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2000;97:588–592. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuelsatz P, Pouzoulet F, Lamarre Y, Dargelos E, Poussard S, Leibovitch S, Cottin P, Veschambre P. Down-regulation of MyoD by calpain 3 promotes generation of reserve cells in C2C12 myoblasts. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:12670–12683. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.063966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki K, Sorimachi H, Yoshizawa T, Kinbara K, Ishiura S. Calpain: Novel family members, activation, and physiological function. Biol Chem Hoppe-Seyler. 1995;376:523. doi: 10.1515/bchm3.1995.376.9.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RG, Geesink GH, Thompson VF, Koohmaraie M, Goll DE. Is Z-disk degradation responsible for postmortem tenderization? J Anim Sci. 1995;73:1351–1367. doi: 10.2527/1995.7351351x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tompa P, Emori Y, Sorimachi H, Suzuki K, Friedrich P. Domain III of calpain is a Ca2+-regulated phospholipid-binding domain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;280:1333–1339. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tullio RD, Passalacqua M, Averna M, Salamino F, Melloni E, Pontremoli S. Changes in intracellular localization of calpastatin during calpain activation. Biochem J. 1999;343:467–472. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Ven PFM, Wiesner S, Salmikangas P, Auerbach D, Himmel M, Kempa S, Haye K, Pacholsky D, Taivainen A, Schröder R, Carpén O, Fürst DO. Indications for a novel muscular dystrophy pathway. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:235–248. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.2.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veiseth E, Shackelford SD, Wheeler TL, Koohmaraie M. Effect of postmortem storage on mu-calpain and m-calpain in ovine skeletal muscle. J Anim Sci. 2001;79:1502–1508. doi: 10.2527/2001.7961502x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veiseth E, Shackelford SD, Wheeler TL, Koohmaraie M. Factors regulating lamb longissimus tenderness are affected by age at slaughter. Meat Sci. 2004;68:635–640. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2004.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, Ramirez-Mitchell R. A network of transverse and longitudina intermediate filaments is associated with sarcomeres of adult vertebrate skeletal-muscle. J Cell Biol. 1983;96:562–570. doi: 10.1083/jcb.96.2.562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, Wright J. Architecture of the sarcomere matrix of skeletal muscle: immunoelectron microscopic evidence that suggests a set of parallel inextensible nebulin filaments anchored at the Z line. J Cell Biol. 1988;107:2199–2212. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.6.2199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YM, Li LF. The relationship between muscle histology characteristics and meat quality on Yushan pigs of JiangXi. Acta J X Agric Univ. 1994;16:284–287. [Google Scholar]

- Wendt A, Thompson VF, Goll DE. Interaction of calpastatin with calpain: A review. Biol Chem. 2004;385:465–472. doi: 10.1515/BC.2004.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler TL, Koohmaraie M. The extent of proteolysis is independent of sarcomere length in lamb longissimus and psoas major. J Anim Sci. 1999;77:2444–2451. doi: 10.2527/1999.7792444x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler TL, Shackelford SD, Koohmaraie M. Variation in proteolysis, sarcomere length, collagen content, and tenderness among major pork muscles. J Anim Sci. 2000;78:958–965. doi: 10.2527/2000.784958x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whipple G, Koohmaraie M. Degradation of myofibrillar proteins by extractable lysosomal enzymes and m-calpain, and the effects of zinc chloride. J Anim Sci. 1991;69:4449–4460. doi: 10.2527/1991.69114449x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White SN, Casas E, Wheeler TL, Shackelford SD, Koohmaraie M, Riley DG, Chase CC, Johnson DD, Keele JW, Smith TPL. A new single nucleotide polymorphism in CAPN1 extends the current tenderness marker test to include cattle of Bos Indicus, Bos Taurus, and crossbred descent. J Anim Sci. 2005;83:2001–2008. doi: 10.2527/2005.8392001x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu XX, Shui X, Chen ZH, Shan CQ, Hou YN, Cheng YG. Development and application of a real-time PCR method for pharmacokinetic and biodistribution studies of recombinant adenovirus. Mol Biotechnol. 2009;43:130–137. doi: 10.1007/s12033-009-9173-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang ZR, Liu YP, Yao YG, Jiang XS, Du HR, Zhu Q. Identification and association of the single nucleotide polymorphisms in calpain3 (CAPN3) gene with carcass traits in chickens. BMC Genet. 2009;10:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-10-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zór K, Ortiz R, Saatci E, Bardsley R, Parr T, Csöregi E, Nistor M. Label free capacitive immunosensor for detecting calpastatin-A meat tenderness biomarker. Bioelectrochemistry. 2009;76:93–99. doi: 10.1016/j.bioelechem.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]