Background: Toxoplasma gondii is exposed to large Ca2+ gradients during its lytic cycle.

Results: Ca2+ entry in T. gondii is a source of Ca2+ increase and is mediated by a nifedipine-sensitive pathway and not by a canonical store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE) pathway.

Conclusion: Ca2+ entry enhances parasite virulence traits.

Significance: This is the first study linking regulation of Ca2+ entry and virulence traits of T. gondii.

Keywords: Calcium, Cell Invasion, Fluorescence, Parasite, Protozoan, Signaling, Conoid Extrusion, Gliding Motility, Toxoplasma gondii, Nifedipine

Abstract

During invasion and egress from their host cells, Apicomplexan parasites face sharp changes in the surrounding calcium ion (Ca2+) concentration. Our work with Toxoplasma gondii provides evidence for Ca2+ influx from the extracellular milieu leading to cytosolic Ca2+ increase and enhancement of virulence traits, such as gliding motility, conoid extrusion, microneme secretion, and host cell invasion. Assays of Mn2+ and Ba2+ uptake do not support a canonical store-regulated Ca2+ entry mechanism. Ca2+ entry was blocked by the L-type Ca2+ channel inhibitor nifedipine and stimulated by the increase in cytosolic Ca2+ and by the specific L-type Ca2+ channel agonist Bay K-8644. Our results demonstrate that Ca2+ entry is critical for parasite virulence. We propose a regulated Ca2+ entry mechanism activated by cytosolic Ca2+ that has an enhancing effect on invasion-linked traits.

Introduction

Elevation in cytoplasmic Ca2+ mediates a plethora of cellular responses in all cells. Protein function is dependent on shape and charge, and both of these features are affected by Ca2+ binding. Cells contain a sophisticated set of mechanisms to balance the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration, and the signals that increase Ca2+ in the cytosol are compensated by mechanisms that decrease it (1).

Ca2+ entry plays an important role in replenishing intracellular organelles and in activating signaling pathways that respond to elevated cytosolic Ca2+ (2). Five types of plasma membrane Ca2+ channels are present in vertebrate cells such as the store-operated channel (ORAI),5 which is linked to the endoplasmic reticulum sensor protein stromal interaction molecule (STIM), voltage-operated channels, ligand-operated channels, transient receptor potential (TRP) channels, and second messenger-operated channels (3), but little is known about the mechanisms involved in Ca2+ entry in the Apicomplexan parasite Toxoplasma gondii.

During its lytic cycle, T. gondii actively invades host cells, creating a parasitophorous vacuole, where it divides to finally exit in search of a new host cell. Parasite invasion is a highly coordinated and active process involving several discrete steps (4). Gliding motility, conoid extrusion, secretion of specific proteins, attachment to the host cell, and active invasion are all critical steps for invasion. Previous studies have shown that intracellular Ca2+ stores are important for initiation of gliding motility (5), microneme secretion (6), conoid extrusion (7), active parasite invasion (8–10), and egress (8) (reviewed in Ref. 11), but the role of extracellular Ca2+ in these processes was not studied in detail or was considered minor.

Considering the enormous Ca2+ concentration gradient (∼20,000-fold), to which tachyzoites are exposed upon egress (100 nm in the host cytosol, taking into account that the parasitophorous vacuole functions as a molecular sieve (12) versus ∼1.8 mm in the extracellular space), it seems a feasible hypothesis that the extracellular stage represents an opportunity to use extracellular Ca2+ as a mechanism to enhance Ca2+-dependent invasion processes as well as to replenish intracellular Ca2+ stores that are likely used during the process of parasite egress. In this work, we explore the mechanism of Ca2+ entry in extracellular tachyzoites and its role during the lytic cycle of the parasite. We present evidence for a regulated Ca2+ entry process and its enhancing effect on invasion-related traits. This is the first detailed study linking Ca2+ entry and its regulation directly to virulence traits of an eukaryotic microbe.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture and Preparation

T. gondii tachyzoites (RH strain) were maintained in hTERT human fibroblasts using DMEM with 1% fetal bovine serum. Intracellular tachyzoites were isolated under intracellular conditions by scraping off infected fibroblasts and passing them through a 27-gauge needle. In this way, parasites were released from host cells while still at intracellular ionic conditions. Extracellular tachyzoites were collected from cultures with 50–75% of egressed parasites. Parasites (both intracellular and extracellular) were purified as described (13) and washed in either low Ca2+ extracellular buffer (EB) or intracellular buffer (IB) (see below).

Experiments testing Ca2+ entry were conducted using EB (116 mm NaCl, 5.4 mm KCl, 1 mm MgSO4, 5.5 mm glucose, 20 mm Hepes, pH 7.4), IB (10 mm NaCl, 130 mm KCl, 10 mm glucose, 0.8 mm MgCl2, 1 mm EGTA, 0.62 mm CaCl2, 20 mm Hepes, pH 7.4) (final free Ca2+, 117 nm) or buffer A (116 mm NaCl, 5.4 mm KCl, 0.8 mm MgSO4, 5.5 mm d-glucose, and 50 mm Hepes, pH 7.4). For low Ca2+ EB, 1 mm EGTA and 0.62 mm CaCl2 were added to bring the free Ca2+ to 110 nm. The final Ca2+ concentrations were determined by using CaCl2-EGTA combinations and calculated using Maxchelator software.

Cytosolic Ca2+ Measurements

Parasites (intracellular or extracellular) were loaded with Fura-2/AM as described (14). Briefly, after harvesting the cells, they were washed twice at 500 × g for 10 min at room temperature in the buffer indicated in each figure legend. The cells were resuspended to a final density of 1 × l09 cells/ml in loading buffer (similar to the isolation buffer plus 1.5% sucrose and 5 μm Fura-2/AM). The suspensions were incubated for 26 min in a 26 °C water bath with mild agitation. Subsequently, the cells were washed twice to remove extracellular dye. Cells were resuspended to a final density of 1 × 109 cells/ml in the indicated buffer and kept in ice. Parasites were viable for several hours under these conditions. For fluorescence measurements, a 50-μl portion of cell suspension was diluted into 2.5 ml of the indicated buffer (final density, 2 × l07 cells/ml) in a cuvette placed in a Hitachi F-4500 spectrofluorometer. Excitation was at 340 and 380 nm, and emission was at 510 nm. The Fura-2 fluorescence response to intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) was calibrated from the ratio of 340/380-nm fluorescence values after subtraction of the background fluorescence of the cells at 340 and 380 nm as described by Grynkiewicz et al. (15). Ca2+ influx (ΔCa2+/s) was evaluated by measuring the rate of [Ca2+]i change during the first 20 s after its addition (linear rate) when the mechanisms of compensation are not yet at full capacity. Manganese quenching experiments were conducted on Fura-2/AM-loaded parasites, and Fura-2 fluorescence was monitored at the isosbestic wavelength (excitation = 360 nm, emission = 510 nm). MnCl2 was added to a final concentration of 2 mm, and the rate of Fura-2 fluorescence quenching was recorded. ΔFU was calculated by measuring the rate of change in fluorescence during the first 20 s after adding manganese (when the rate is linear). No Fura-2 leakage into the extracellular media was detected (data not shown).

Gliding Assays

Purified parasites were lightly adhered to polylysine-coated coverslips by placing them (2 × 107 cells/ml) on a coverslip on ice for 4 min. Non-adhered cells were washed away, and coverslips were incubated at different conditions at 37 °C for 10 min, and immunofluorescence images were acquired as described previously (5). Images were acquired using an Olympus IX-71 inverted microscope with a Photometrix CoolSnap CCD camera operated by DeltaVision image reconstruction software (Applied Precision, Seattle, WA). Gliding trail length was quantified with ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health) by measuring trails (positively stained with SAG1 antibody) that were directly associated with a parasite. For all treatments, at least 50 parasite trails were measured within each experiment.

Conoid Extrusion

Conoid extrusion was tested following the protocol of Mondragon and Frixione (7). Parasites were kept in IB at 110 nm free Ca2+. Parasites were spun down and resuspended in IB or EB at different conditions (e.g. Ca2+ or in the presence of the calcium ionophore ionomycin). Experiments were initiated by placing the parasites at 37 °C and terminated by the addition of 4% formaldehyde. The percentage of parasites with their conoids extruded, reflecting the initiation of the invasion process, was assessed using an Olympus BX60 microscope. At least 100 parasites were evaluated for treatment within each independent experiment.

Microneme Secretion

Purified intracellular parasites were collected in IB and resuspended in the same buffer with varying amounts of free calcium. Microneme secretion was measured at 37 °C for 15 min following published protocols (6). Rabbit anti-GRA1 at 1:10,000 was used as secretion control.

Host Cell Invasion

Red-Green assay was modified from the assay described previously (16). Intracellular RH tachyzoites were collected in IB, centrifuged, and resuspended in the following concentrations of free calcium: 160 nm, 99.3 μm, 1 mm, and 2 mm at a parasite concentration of 1 × 108 cells/ml. 2.5 × 107 tachyzoites were added to subconfluent hTERT monolayers, allowed to settle for 15 min on ice, and then incubated for 2 min at 37 °C. Subsequently, the medium was aspirated and fixed with 2.5% formaldehyde for 20 min. Subsequent steps were done as published (16). Cell counting data from three independent experiments were collected; each one by triplicate, counting eight randomly selected fields per individual coverslip. The number of invaded parasites was calculated as the difference between the total number of parasites (green) and the number of attached parasites (red). Nifedipine inhibition of invasion was tested in invasion media (DMEM, 10 mm Hepes, pH 7.4, and 3% fetal bovine serum).

RESULTS

Evidence for a Regulated Ca2+ Entry Pathway in T. gondii Tachyzoites

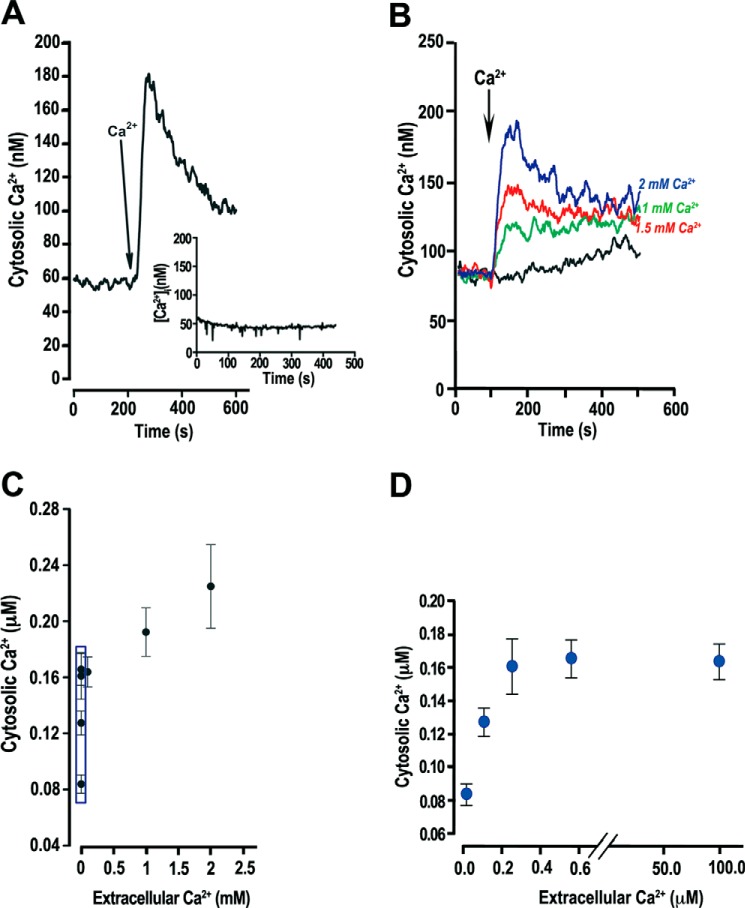

Upon egress from their host cell, T. gondii tachyzoites face a large change in extracellular Ca2+ concentration from nanomolar levels, when in contact with the host cytoplasm through the parasitophorous vacuole, to ∼1.8 mm, in the extracellular milieu. Our hypothesis is that tachyzoites allow for some of this Ca2+ to enter but in a regulated manner. To simulate conditions present upon exit of tachyzoites from the host cells, we suspended parasites obtained under intracellular conditions (see “Experimental Procedures”) and loaded them with Fura-2/AM at a Ca2+ concentration usually present in the cytosol (110 nm; low Ca2+ EB; see “Experimental Procedures”). The addition of extracellular Ca2+ (∼1 mm) elicited an increase in intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) (Fig. 1A) that slowly returns to the basal level. Higher extracellular Ca2+ concentrations (1.5 and 2 mm) led to higher cytosolic Ca2+ (Fig. 1B). We measured [Ca2+]i over a wide range of extracellular Ca2+ concentrations (Fig. 1C), consistently observing an increase in final [Ca2+]i (after return to basal levels) up to 0.6 μm (Fig. 1D). Higher extracellular Ca2+ concentrations (1.5–2 mm) led to minor changes in intracellular levels (Fig. 1C). Although there was significant entry of Ca2+, its final concentration was orders of magnitude lower than the extracellular concentration (Fig. 1C). The curve in Fig. 1C shows a biphasic phenomenon, which could be due to the participation of more than one Ca2+ permeation pathway. Tachyzoites isolated under extracellular conditions (see “Experimental Procedures”) also showed this phenomenon of Ca2+ entry upon addition of Ca2+ (data not shown) (see “Experimental Procedures” for buffer compositions).

FIGURE 1.

Ca2+ entry in extracellular tachyzoites. Measurements were made in low Ca2+ EB (see “Experimental Procedures”). A, addition of Ca2+ (1 mm) to Fura-2/AM-loaded tachyzoites leads to an increase in cytosolic Ca2+. Inset, no addition. B, addition of various extracellular Ca2+ concentrations leads to higher intracellular Ca2+ increase. At 100 s, varying concentrations of Ca2+ were added to the extracellular buffer: 2 mm (blue), 1.5 mm (red), 1 mm (green), and no addition (black). C, increase in extracellular Ca2+ concentration resulted in a large increase in cytosolic Ca2+ followed by a plateau at ∼200 nm. D, amplification of the boxed area shown in C. The error bars in all cases indicate means ± S.E. (n = 3).

This phenomenon of saturable [Ca2+]i increase with increasing extracellular Ca2+, and the maintenance of cytosolic Ca2+ levels orders of magnitude below that of the extracellular Ca2+ concentration, support the conclusion that entry of extracellular Ca2+ is regulated by the parasite and probably occurs through the coordination of specific entry channels (probably more than one) and compensatory mechanisms operated by Ca2+ pumps.

Calcium Entry Is Not Stimulated by Store Depletion but Blocking the SERCA-type Ca2+ ATPase Leads to Higher Cytosolic Ca2+ Levels

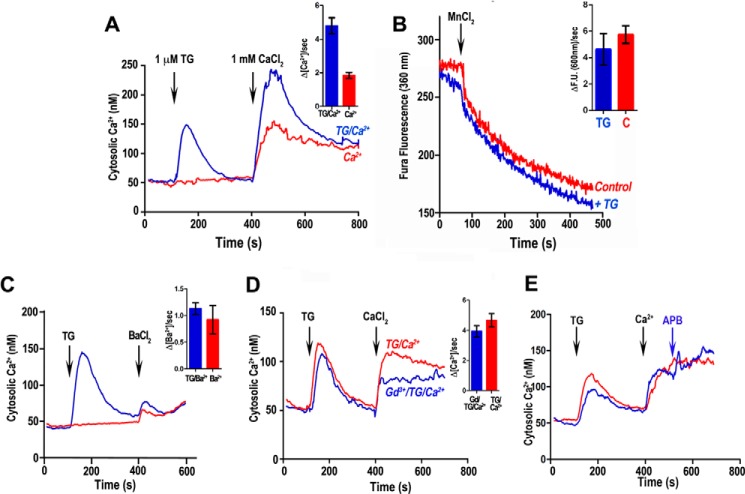

We next investigated whether Ca2+ entry could be further enhanced by depletion of Ca2+ from intracellular stores (store-operated Ca2+ entry, or SOCE), a mechanism proposed to operate in the related Apicomplexan Plasmodium falciparum (17). To test for SOCE, we used thapsigargin (TG), an inhibitor of the SERCA-type Ca2+-ATPase, which results in leakage of Ca2+ from the endoplasmic reticulum as a consequence of inhibiting the uptake pathway. The addition of TG 300 s prior to adding CaCl2 resulted in a reproducible higher influx, which can be observed by an increase in [Ca2+]i as compared with the control in the absence of TG (Fig. 2A).

FIGURE 2.

Ca2+ entry in tachyzoites is enhanced in the presence of thapsigargin but entry is not through a canonical store-regulated channel. Parasites (5 × 107 cells) were loaded with Fura-2/AM and resuspended in 2.5 ml of EB in the presence of 100 μm EGTA. A, cytosolic Ca2+ changes upon addition of 1 μm TG at 100 s and then 1 mm CaCl2 at 400 s (blue line). The red line represents the cytosolic Ca2+ changes after Ca2+ addition alone. The inset shows quantification of the initial rate of Ca2+ entry after adding Ca2+. At least three independent experiments were used for the quantification. B, Ca2+ entry measured by Mn2+ quenching. Fura-2/AM-loaded parasites were monitored at the Fura-2 isosbestic fluorescence point (excitation = 360 nm). The blue tracing is the tracing obtained after adding 1 μm TG. The inset shows quantification of the rate of MnCl2 uptake from three or more independent experiments. 2 mm MnCl2 was added where indicated. C, Ba2+ entry and binding of Fura-2. The blue line shows the increase in Fura-2 fluorescence after store depletion with 1 μm TG. The red line indicates increase in fluorescence without depletion of intracellular stores. There is no significant difference in the initial rate of fluorescence increase after Ba2+ addition (1 mm) under both conditions (inset). The inset shows the quantification of the initial rate of BaCl2 uptake from a minimum of three independent experiments. D, Gd3+ inhibition. The blue line shows preincubation with 5 μm Gd3+ and addition of 1 μm TG and then 1 mm Ca2+. The red line shows increased Fura-2 fluorescence after store depletion with 1 μm TG alone. The inset shows quantification of initial rates of Ca2+ uptake. A minimum of three independent experiments was used for the quantification. E, Ca2+ entry enhanced by TG is not affected by 2-APB. 2-APB (30 μm) was added where indicated. The error bars in all cases indicate means ± S.E. (n = 3).

The results described above (Fig. 2A) seemed to indicate the existence of SOCE in T. gondii. However, the increases in [Ca2+]i evoked by restoring Ca2+ with and without prior TG treatment differed only in that the former had a transient overshoot, but thereafter the “sustained” phases were similar (after the initial peak). These results seem most easily explained by a larger increase in [Ca2+]i because of the inhibition of SERCA, which can no longer contribute to sequester incoming Ca2+. We next tested this possibility by different strategies. The surrogate ion Mn2+ is known to permeate through Ca2+ channels, effectively quenching Fura-2 fluorescence. In addition, Mn2+ is a poor substrate for most Ca2+-dependent enzymes/processes so that any quenching observed in Fura-2/AM-loaded parasites would be due to Mn2+ entry. An abrupt quenching of cytosolic Fura-2 fluorescence was observed at the Ca2+-independent excitation wavelength of 360 nm (Fig. 2B). However, the rate of quenching was not increased by thapsigargin, suggesting that this flux of Mn2+ was not stimulated through store depletion (Fig. 2B, inset). To further investigate this phenomenon, we used Ba2+, which enters cells through Ca2+ channels and binds Fura-2 modifying its fluorescence in a similar way to Ca2+ (18). We measured the initial rate of entry under identical conditions used to measure Ca2+ entry after thapsigargin (Ca2+ “add back”), and rates were similar in the presence and absence of thapsigargin (Fig. 2C, inset). This is in agreement with the Mn2+ quenching experiment and indicates that the phenomenon of Ca2+ entry is likely not store-regulated. We also tested two inhibitors of SOCE channels, gadolinium (Gd3+) at 5 μm (Fig. 2D) and 2-aminomethoxydiphenyl borate (2-APB) at 30 μm (Fig. 2E). We did not observe any effect on Ca2+ entry with any of these inhibitors. Although it appears as if Gd3+ inhibits the amount of Ca2+ entry, initial rates (see “Experimental Procedures” for explanation of calculations) were not significantly different to the initial rate of Ca2+ entry after adding Ca2+ alone (Fig. 2D, inset). It is possible that Gd3+ could partially block a plasma membrane voltage-gated calcium Ca2+ channel (VGCC) as reported previously (19), limiting the amount of Ca2+ entering, but the initial rate is not affected.

In summary, our results do not support the presence of a Ca2+ entry channel regulated by store depletion. The absence of store regulation of Ca2+ entry is supported by the lack of genomic evidence for the presence of SOCE molecular players (STIM and ORAI) in any Apicomplexan parasite (EuPath.DB).

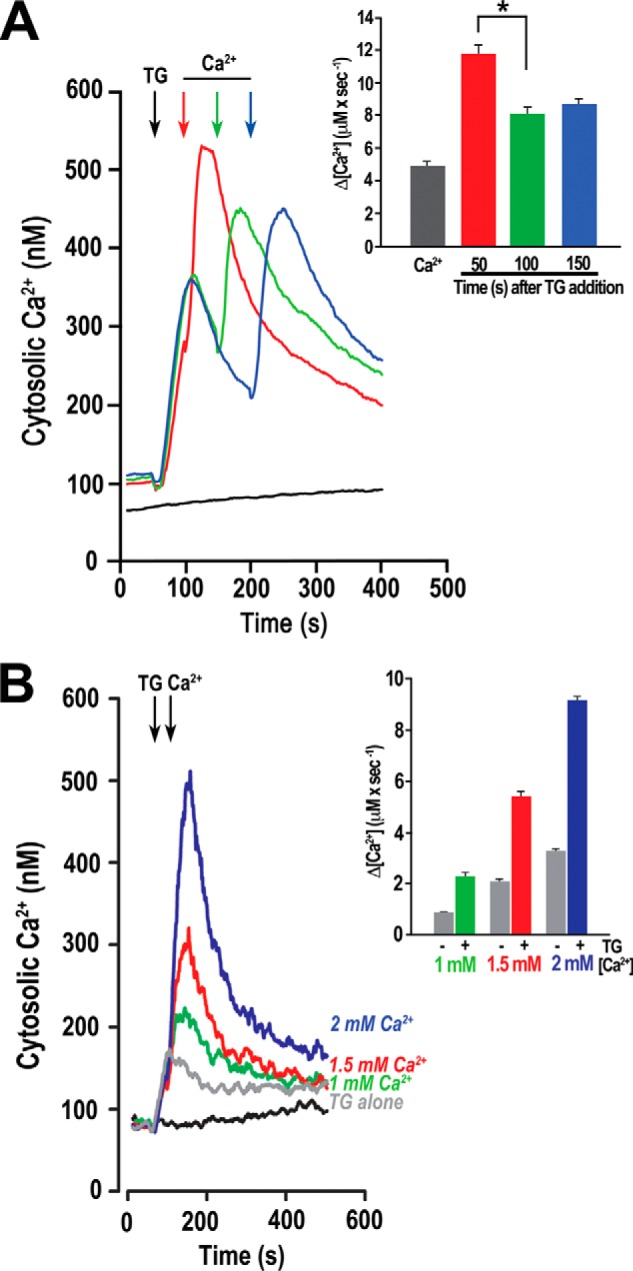

The Influence of Cytosolic Ca2+ on Ca2+ Entry

The increased Ca2+ accumulation after TG addition as a result of SERCA inhibition could result in opening of a plasma membrane Ca2+ channel through a Ca2+ induced Ca2+ uptake mechanism. To study whether this was the case, we investigated whether there was a correlation between the [Ca2+]i levels and the rate of Ca2+ entry. The addition of TG leads to an increase in cytosolic Ca2+ and a decrease after reaching a maximum caused by reuptake or efflux of released Ca2+. We added Ca2+ back at different times after the addition of TG (50, 100, and 150 s) at points when the cell reached different levels of cytosolic Ca2+ (Fig. 3A, inset). If Ca2+ entry was modulated by cytosolic Ca2+, then as [Ca2+]i decays, so too would the rate of influx of extracellular Ca2+. Calcium “add back” at different times after TG showed that there is a significant difference between the rate of Ca2+ entry at 50 s versus 100 and 150 s after TG addition (Fig. 3A, inset). Ca2+ entry rate at 100 and 150 s was ∼30% lower than the rate at 50 s, which is when [Ca2+]i is highest.

FIGURE 3.

Role of [Ca2+]i in Ca2+ entry as detected by varying the time interval between TG and Ca2+ additions. Fura-2/AM loaded parasites were treated with 1 μm TG and Ca2+ added back at different times. A, the red line shows a representative tracing where Ca2+ (1 mm) was added 50 s after TG (at maximum TG response, red arrow). Green line shows the response to addition of Ca2+ 100 s after TG (green arrow). The blue line represents a time interval of 150 s (after TG response, blue arrow). Inset, quantified responses for four independent experiments measuring Ca2+ entry for Ca2+ alone (Ca2+) and Ca2+ addition at different time points (in seconds) after TG addition. Rates of Ca2+ entry were measured in the first 20 s. Rate of Ca2+ entry was significantly higher at 50 s when the cytosolic Ca2+ was highest (ANOVA, p < 0.05). B, Ca2+ entry in T. gondii after the addition of TG. Fura-2/AM loaded parasites in EB were treated with 1 μm TG at 50 s, and then the concentrations of Ca2+ indicated were added at 100 s. For reference, the increase in cytosolic Ca2+ upon addition of TG alone is also shown (gray line). Inset, quantification of the initial Ca2+ entry rates of three or more independent experiments. Gray bars represent increase in cytosolic Ca2+ after adding only extracellular Ca2+, colored bars represent increase when the same amount of Ca2+ addition is preceded by 1 μm TG. Error bars in all cases indicate means ± S.E. (n ≥ 3).

We also observed that the rate of Ca2+ entry after addition of 1, 1.5, and 2.0 mm Ca2+ after TG addition increased significantly when compared with the rates of entry with the same Ca2+ concentrations without TG (Fig. 3B) (compare gray and color bars of Fig. 3B, inset). We added Ca2+ back 50 s after the addition of TG, and we observed that the rate of Ca2+ entry was consistently 2.5 times higher in the presence of TG for all the treatments (Fig. 3B, inset). This enhancing effect of TG was independent of the ionic conditions used for purification of parasites and measurements (data not shown). In summary, Ca2+ release from intracellular stores results in an increase in cytosolic Ca2+, and this elevated Ca2+ could directly modulate a Ca2+ entry channel. This result agrees with the results shown in Fig. 2A where a higher level of Ca2+ entry was observed after blocking the SERCA with TG.

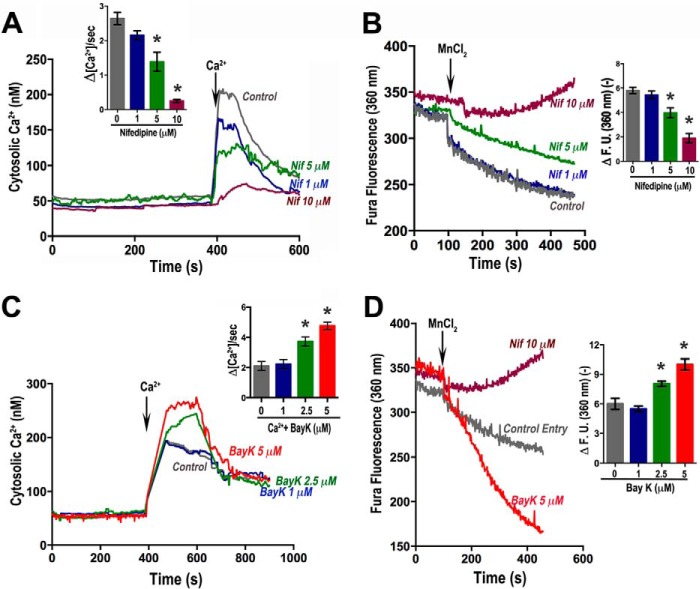

Inhibition of Ca2+ Entry

To investigate the mechanism of Ca2+ entry we tested a range of channel blockers and inhibitors like 2-APB (30 μm) (20), nifedipine (1–10 μm), verapamil (1–100 μm), and diltiazem (10–100 μm) (21). Only nifedipine, an inhibitor of L-type voltage-activated Ca2+ channels, was effective in blocking Ca2+ entry (Fig. 4A). 2-APB at 30 μm had no effect on Ca2+ entry enhanced by thapsigargin, supporting the lack of participation of a SOCE Ca2+ channel (Fig. 2E). Nifedipine also decreased Mn2+ quenching in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4B), suggesting that entry of extracellular Ca2+ is through a channel-mediated process and that nifedipine is an effective blocker of such Ca2+ entry.

FIGURE 4.

Ca2+ entry inhibition and stimulation. Conditions as in Fig. 2. A, Ca2+ entry (1 mm) is inhibited in parasites preincubated for 2 min with nifedipine (Nif) ranging from 1 to 10 μm. Inset, quantification of initial rates measure from at least three independent experiments. B, Mn2+ quenching inhibition by nifedipine. Fura-2/AM-loaded parasites were monitored at the Fura-2 isosbestic fluorescence point (excitation = 360 nm). 2 mm MnCl2 was added where indicated. Inset, rate of Mn2+ quenching was significantly decreased (ANOVA of slope: n = 4, p < 0.05) by nifedipine. C, Bay K-8644 enhances Ca2+ entry. Fura-2/AM-loaded parasites in EB were analyzed in the presence of 100 μm EGTA, and 1 mm Ca2+ was added at the indicated time. Inset, quantification of initial rates ± S.E. after adding Ca2+ of at least three independent experiments. D, Mn2+ entry in tachyzoites in Fura-2/AM-loaded parasites (5 × 107 cells in EB). Quenching by Mn2+ was measured in the presence of Bay K (5 μm) (red line) or 10 μm nifedipine (maroon line). Mn2+ (2 mm) was added where indicated (100 s). The conditions were 2 mm MnCl2 + DMSO (control entry, gray line), 2 mm MnCl2 + 5 μm BayK (red line), and 2 mm MnCl2 + 10 μm nifedipine (maroon line). Inset, rates of change in Fura-2 fluorescence at the isosbestic point ± S.E. (n = 4) during the first 20 s after addition of manganese alone or plus 1, 2.5, and 5 μm Bay K. **, p < 0.01 (one-way ANOVA).

Taking into account the inhibition of Ca2+ entry by nifedipine, we tested Bay K-8644 (Bay K), a Ca2+ channel agonist that acts by opening L-type channels (CaV1 family), increasing the time the channel is open and causing a large increase in the channel macroscopic response (22). Bay K (2.5–5 μm) stimulated Ca2+ entry when tested in Fura-2-loaded cells (Fig. 4C, inset). Using the Mn2+-quenching technique (Fig. 4D), we found that Ca2+ entry in extracellular tachyzoites was significantly enhanced when parasites were treated with 5 μm Bay K (Fig. 4D). The inset in Fig. 4D shows the quantification of rates obtained after adding 1, 2.5, and 5 μm Bay K.

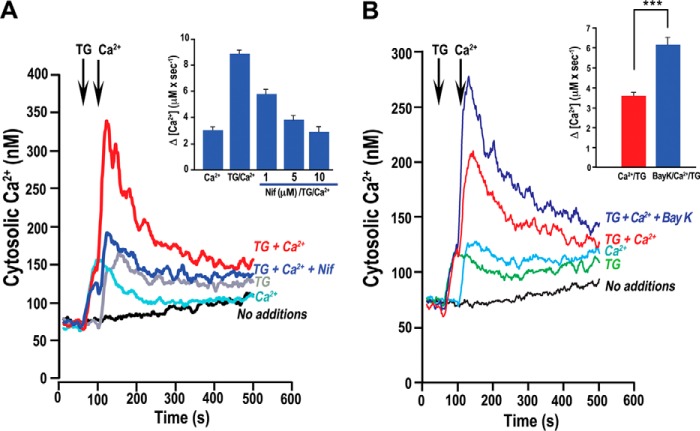

We also tested nifedipine and Bay K after blocking the SERCA with TG to obtain higher cytosolic Ca2+ levels (Fig. 5). We observed a significant inhibition by nifedipine of Ca2+ entry measuring the initial rate (Fig. 5A, inset). The addition of TG followed by the simultaneous addition of CaCl2 and 5 μm Bay K (blue trace) elicited a greater accumulation of Ca2+ over that of TG and Ca2+ alone (Fig. 5B, red trace). The quantification of these relative differences in these measurements demonstrated that Bay K addition resulted in a significant increase (ANOVA comparison of slopes: p < 0.001) in Ca2+ accumulation (Fig. 5B, inset).

FIGURE 5.

Nifedipine inhibits Ca2+ entry enhanced by thapsigargin. A, Ca2+ accumulation enhanced by TG (1 μm), which was added at 50 s followed by 2 mm Ca2+ at 100 s (red line), is inhibited by preincubating parasites with 10 μm nifedipine (blue line). The black line is the baseline cytosolic Ca2+ level, the gray line shows addition of TG, and the light blue line shows the response to Ca2+ addition alone. Inset, quantification of rate of Ca2+ entry after nifedipine inhibition. One-way ANOVA of regression model yielded a significant relationship between inhibition of Ca2+ entry and nifedipine concentration: p < 0.001. B, Bay K enhances Ca2+ entry. TG (1 μm), Ca2+ (2 mm) and Ca2+ + Bay K (5 μm) were added where indicated. Blue line, 2 mm Ca2+ + TG + BayK; red line, Ca2+ + TG; light blue line, baseline Ca2+ addition, green line is the response to TG (1 μm) alone; black line, cytosolic Ca2+ with no additions. Inset shows the quantification of the rate of Ca2+ entry for multiple replicate measurements of TG + Ca2+ (red bar) and TG + Ca2+ + Bay K (blue bar). ***, p < 0.01 (one-way ANOVA). Conditions as in Fig. 3.

The Role of Ca2+ Entry in Virulence-related Traits: Gliding Motility, Conoid Extrusion, Microneme Secretion, and Host Cell Invasion

Previous work (6–10) has shown that [Ca2+]i increase is involved during all these steps of the tachyzoite lytic cycle, but the source of this Ca2+ increase has been proposed to be mostly Ca2+ release from intracellular Ca2+ stores on the basis of experiments using high concentrations of extracellular EGTA to prevent Ca2+ entry. Our hypothesis is that upon egress, the parasite encounters a ∼20,000-fold higher concentration of Ca2+, and this gradient should result in a strong electrochemical driving force favoring Ca2+ influx. We therefore investigated whether this Ca2+ influx plays a role in gliding motility, conoid extrusion, microneme secretion, and host cell invasion. We isolated parasites using both intra- and extracellular ionic concentrations and exposed them to higher, physiologically relevant Ca2+ concentrations to quantify these processes.

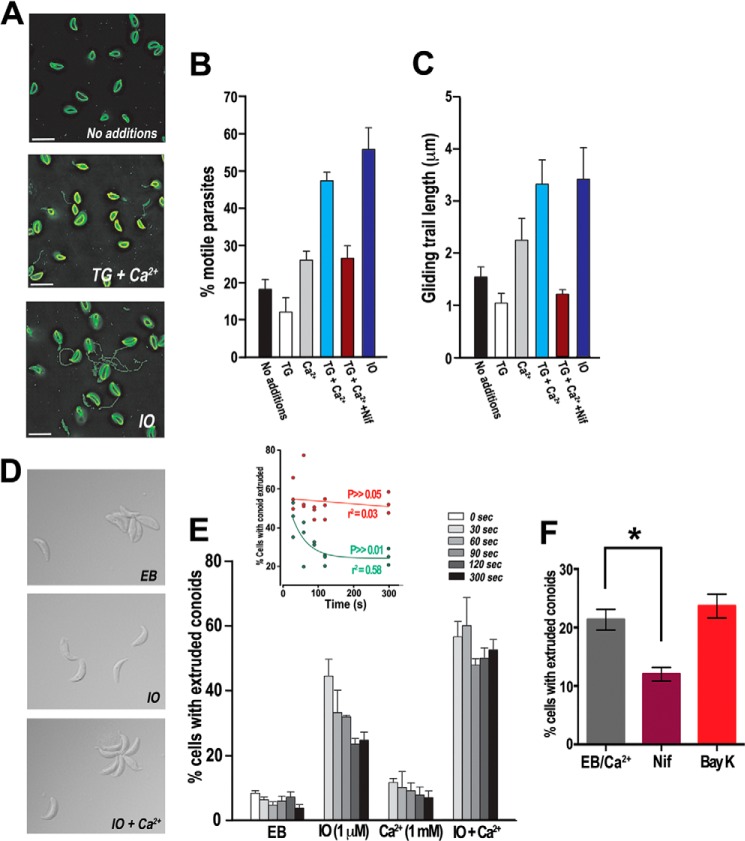

Parasites treated with different reagents to promote high cytosolic Ca2+ concentration were stained to determine whether they possessed a SAG1 positive gliding trail and the length of the trail. Parasites kept in standard buffer conditions showed only minimal movement and relatively small gliding trails (Fig. 6A, no additions). Parasites that were placed in the physiological context of Ca2+ entry by addition of extracellular Ca2+ or that had an increase in Ca2+ accumulation by addition of TG and extracellular Ca2+ (Fig. 6A, TG + Ca2+) or ionomycin (Fig. 6A, IO) showed an increase in both the percentage of gliding parasites and the length that the parasites moved (Fig. 6, B and C). Fig. 6A shows representative images used to obtain the quantification shown in Fig. 6 (B and C), which show the percentage of motile parasites and the trail length, respectively. Ionomycin (IO, 1 μm) was used as a positive control because this reagent releases all Ca2+ stored in neutral compartments and also increases Ca2+ entry evoking a maximal response. Importantly, the addition of nifedipine (10 μm) (in the presence of TG + Ca2+) caused a significant decrease in gliding response (Fig. 6, B and C, maroon bars). Interestingly, motility, as expressed as the percentage of parasites associated with a trail, did not get reduced beyond the levels of Ca2+ alone (Fig. 6B), whereas gliding motility, expressed as average trail length, did (Fig. 6C), suggesting that nifedipine is inhibiting gliding motility rather than other types of motility.

FIGURE 6.

Ca2+ entry enhances gliding motility and conoid extrusion. A, gliding trails visualization by SAG1 immunolocalization. Representative micrographs showing the SAG1 signal after different treatments (see label details below). These micrographs were used for the quantification number of motile parasites in B and the average trail length in C. Scale bar, 5 μm. B, average percentage (n = 5 ± S.E.) of extracellular tachyzoites that were directly associated with a gliding trail. C, the average length (n = 100 ± S.E.) of parasites directly associated with a gliding trail. TG, TG (2 μm); Ca2+ = 1.6 mm free Ca2+; TG + Ca2+, 2 μm TG and 1.6 mm free Ca2+; Nifedipine, same as TG + Ca2+ with a 60-s preincubation with 10 μm nifedipine; IO = 1 μm ionomycin. D, role of extracellular Ca2+ on conoid extrusion. Representative images obtained after the treatments: extracellular parasites were collected and exposed to Ca2+ (2 mm, EB), ionomycin (1 μm IO), or both (IO + Ca2+) for 5 min at 37 °C. E, quantification of conoid extrusion response. Parasites were collected at specified times, fixed, and assessed for the percentage of parasites with an extruded conoid. Inset, kinetic analysis of conoid extrusion in extracellular parasites. Kinetic monitoring of conoid extrusion shows that when ionomycin-treated parasites were also given extracellular Ca2+ (2 mm), they responded with a greater percentage of extruded conoids and for extended amount of time (red symbols) as evidenced by a statistically nonsignificant slope value (p > 0.05). Parasites treated with ionomycin in buffer with cytosolic levels of Ca2+ (110 nm) responded with an initial increase in conoid extrusion that displayed exponential decay kinetics (green symbols). F, effect of nifedipine (10 μm, Nif) and Bay K (2.5 μm) on conoid extrusion. Parasites were treated as described under “Experimental Procedures,” and the percentage of parasites with their conoid extruded was evaluated at 300 s. The average ± S.E. of three experiments of parasites with their conoids extruded under extracellular buffer with Ca2+ (1 mm) was 21.3%. Incubation with nifedipine reduced this number to 12% (p = 0.0062) and in the presence of Bay K; 23.7% of the parasites had their conoids extruded. Measurements were done using parasites suspended in extracellular buffer.

Experiments were also conducted to directly visualize the role of Ca2+ accumulation caused by Ca2+ entry in tachyzoite motility. Using the same conditions as seen in Fig. 1C parasites were treated with Ca2+ alone, thapsigargin alone, or with both. Time lapse microscopy showed that although the addition of Ca2+ or thapsigargin alone had a small effect on motility, the addition of both caused a substantial increase in motility (supplemental Videos S1 and S2).

Before invasion, tachyzoites extend their conoids (conoid extrusion), a highly dynamic organelle situated at the apical end of the parasite, which has been shown to be stimulated by an increase in [Ca2+]i (7). We measured the ability of parasites to extrude their conoid over a relevant period of time (Fig. 6, D–F). Parasites kept in extracellular buffer conditions but at low Ca2+ concentration (Ca2+ ∼ 110 nm) for the 5-min experiment showed no significant increase in conoid extrusion (Fig. 6E, EB). The addition of IO (1 μm), which has been used previously to stimulate conoid extrusion (7), increased conoid extrusion when compared with control parasites. Extracellular Ca2+ (1 mm) produced a minor increase in conoid extrusion. A high percentage of parasites treated with both IO and extracellular Ca2+ extruded their conoids. Importantly, this increase in conoid response was maintained throughout the 5-min experiment, whereas the IO-treated parasites exhibited a higher initial increase in conoid extrusion followed by a significant reduction for the remainder of the experiment (Fig. 6E, inset). The difference obtained between IO treatment alone and in the presence of extracellular Ca2+ shows the importance of extracellular calcium in enhancing conoid extrusion and also that in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ (Fig. 6E, inset), the response is not sustained. In agreement with the enhancing effect of Ca2+ entry, nifedipine inhibited conoid extrusion (Fig. 6F) in the presence of extracellular Ca2+. We did not find a significant difference on the percentage of parasites with their conoids extruded when preincubated in the presence of Bay K. This could be because compensatory mechanisms in the parasite (i.e. plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase) would not allow cytosolic Ca2+ to stay elevated for extended lengths of time. As with other experiments, switching the ionic environment from an extracellular environment to an intracellular environment resulted in similar patterns of conoid extrusion (data not shown).

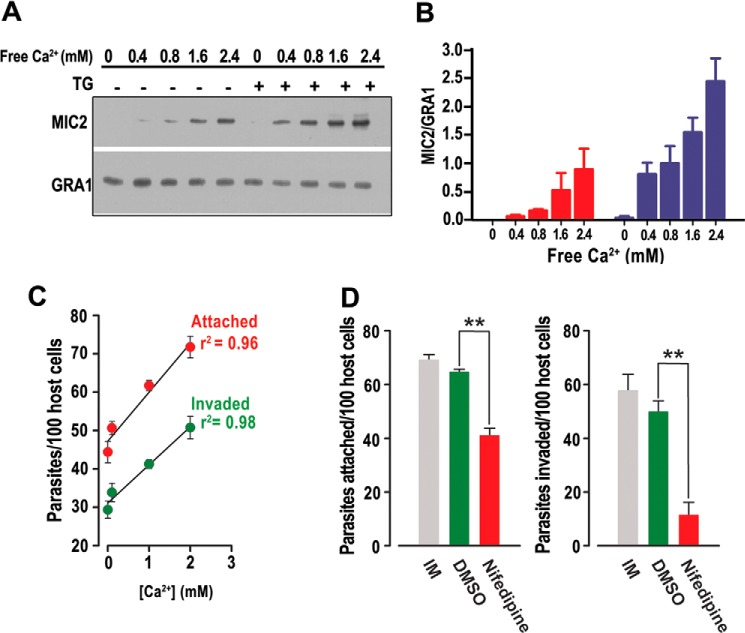

T. gondii tachyzoites contain micronemes, which are secretory organelles involved in host cell invasion. Microneme secretion is stimulated naturally upon host cell attachment. Although microneme proteins are secreted at a low rate in extracellular tachyzoites (23), the process can be accelerated 10–100-fold by elevating the intracellular Ca2+ concentration (6). We studied the secretion of MIC2, a protein used as a marker to study microneme secretion (24). Parasites were exposed to increasing amounts of extracellular calcium (0–2.4 mm) after a short preincubation in a Ca2+-free buffer to measure secretion of MIC2 (Fig. 7A). This treatment resulted in a significant increase in the amount of MIC2 protein secreted from the parasite into the medium, as detected by Western blot analysis (Fig. 7A). The amount of MIC2 secretion in the same cohort of parasites when treated with TG (1 μm) followed by the same Ca2+ concentrations resulted in MIC2 secretion that was significantly higher than after the addition of Ca2+ alone (Fig. 7A, compare ± TG). Fig. 7B is the quantification of three independent experiments and displays the consistency of this phenomenon. Importantly, MIC2 secretion was significantly higher when parasites were exposed to TG (blue bars). These results show the previously documented importance of intracellular stored Ca2+ while demonstrating the significant enhancement that occurs in microneme secretion when Ca2+ accumulates under Ca2+ entry conditions.

FIGURE 7.

Extracellular Ca2+ entry enhances microneme secretion and host cell invasion. A, Western blot analysis of a representative MIC2 secretion experiment (upper panel) under different extracellular Ca2+ concentrations. Lower panel is secretion control with anti-GRA1. Where indicated, 1 μm TG was added. MIC2 signal was below the level of detection at 0 mm Ca2+. B, quantification of gel band intensity of MIC2 secretion (± S.E.) from three independent experiments (one of which is shown in A) with (blue bars) and without (red bars) TG addition. Experiments were standardized to loading controls and quantified using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health). C, relationship of extracellular Ca2+ concentration and number of parasites attached to or invaded into host cells as determined by a red-green invasion assays. Both attachment and invasion showed significant relationships with Ca2+ concentration (p < 0.01 for both attachment and invasion). D, inhibition of invasion and attachment by nifedipine. IM, invasion medium; DMSO, = vehicle control; Nifedipine, 10 μm nifedipine. **, p < 0.01.

The cumulative effect of Ca2+ on invasion-linked traits was assessed by the direct measurement of host cell attachment and invasion of parasites. Red-green assays demonstrated that parasites exhibited higher frequencies of host cell attachment and invasion when incubated in increasing concentrations of extracellular Ca2+ (Fig. 7, C and D). Additionally, when access to extracellular Ca2+ was blocked through the use of nifedipine (10 μm), there was a significant decrease in parasite attachment and invasion in host cells relative to DMSO vehicle controls (Fig. 7D).

DISCUSSION

This study provides evidence for a highly regulated mechanism of Ca2+ entry in T. gondii extracellular tachyzoites. Ca2+ levels were enhanced after depleting intracellular Ca2+ stores with TG, a SERCA-type Ca2+-ATPase inhibitor. Our results do not support the activation of a SOCE channel. We assayed the rate of Mn2+ entry and its response to the degree of store filling (2). The rate of Mn2+ quenching was not stimulated by the preaddition of TG, indicating that store depletion did not activate Ca2+ entry in tachyzoites. We also could not demonstrate store-operated Ba2+ influx. The higher accumulation of cytosolic Ca2+ in the presence of TG, could be the result of the SERCA pump inhibition rather than of direct stimulation of the entry channel by store depletion.

This highly regulated Ca2+ entry was stimulated by [Ca2+]i, inhibited by the L-type Ca2+ channel blocker nifedipine, and stimulated by the L-type Ca2+ channel agonist Bay K. Fura-2 fluorescence quenching by Mn2+ entry was also inhibited by nifedipine and significantly stimulated by Bay K, suggesting a similar mechanism of entry.

Our data support the presence of a Ca2+ channel in tachyzoites probably voltage-gated, modulated by Ca2+ itself. Certain voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (e.g. L-type channels) upon becoming permeable to Ca2+ (i.e. gate opening) will respond to cytosolic Ca2+ by becoming more permeable, a process called Ca2+-dependent facilitation (25). We tested this possibility by exploring the correlation between cytosolic Ca2+ concentration and extent of Ca2+ influx. We manipulated the intracellular Ca2+ concentration using TG to block uptake by the ER and allow other uptake mechanisms to operate for different lengths of times, resulting in different cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations prior to the addition of extracellular Ca2+. Under these conditions, the rate of Ca2+ entry was significantly higher at higher cytosolic Ca2+ concentration, indicating a possible enhancement effect of cytosolic Ca2+ itself on the putative Ca2+ entry channel.

Calcium ions impact nearly every aspect of cellular life. SOCE mechanisms are activated specifically in response to depletion of Ca2+ from intracellular organelles. This Ca2+ is used to replenish those organelles and to activate Ca2+-sensitive signaling pathways. The molecular players (STIM1 and ORAI) involved in SOCE in some eukaryotes were discovered only a few years ago, almost 20 years after the phenomenon was described in mammalian cells (26). Specific searches in the T. gondii genome, as well as in other Apicomplexan genomes, have revealed no evidence for the existence of STIM or ORAI (27, 28), in agreement with our results on the absence of SOCE in T. gondii. It is interesting to note, however, that evidence for the presence of STIM and ORAI orthologs has been reported in other unicellular protists, like the choanoflagellate Monosiga brevicollis, which belongs to the supergroup Ophisotkonta, which also includes animals and fungi (11, 29).

A critical question emerging from our data is the molecular identity of the Ca2+ permeation pathways. The dihydropyridine analog, nifedipine, an L-type calcium channel inhibitor, showed consistent inhibition of Ca2+ entry, whereas the use of an agonist of L-type Ca2+ channels, Bay K, demonstrated the ability to enhance Ca2+ and Mn2+ entry. Other members of the VGCC group (N, P/Q, and R) are insensitive to the effects of these modulators (30). The genome of T. gondii predicts the presence of a putative VGCC (31) (TGME49_205265), the type of channel expected to be nifedipine-sensitive. In addition, a recent evaluation by Prole and Taylor (27) found a second gene with homology to VGCCs (Cav), TgME49_267720, which may encode a subunit of a Ca2+ channel as the sequence predicts for the presence of six transmembrane domains. An attractive hypothesis is that the Ca2+ entry observed in this study involves one or more of these Ca2+ channels. Interestingly, Ca2+ entry in response to various extracellular Ca2+ concentrations showed a biphasic mode in support of the participation of more than one channel or permeation pathway. The use of T. gondii as a model basal eukaryote may provide very useful information for understanding the evolution of Ca2+ regulation and signaling. Further exploration of these genes is warranted given the supporting evidence in ToxoDB.org. Interestingly, Pezzella et al. (32) reported an effect on invasion when using dihydropyridine Ca2+ channel inhibitors similar to nifedipine, the reagent used in this study to inhibit Ca2+ entry and invasion-linked responses.

In this study, we quantitatively correlated Ca2+ entry with invasion-linked behavior. This strategy proved to be very useful in highlighting how extracellular Ca2+ enhances invasion-linked traits. We designed our experiments so that free Ca2+ concentrations were always defined and tightly controlled (∼110 nm range). We looked at motility, conoid extrusion, microneme secretion, and invasion, and Ca2+ entry enhanced all of these traits. The enhancement was more dramatic when cytosolic levels were elevated with ionophores or with the SERCA inhibitor TG. The use of ionophores in the presence of extracellular Ca2+ led to higher intracellular Ca2+ levels, suggesting a potential association. This can be appreciated in further examination of the conoid extrusion data. Release of stored Ca2+ by ionophore treatment results in a large response in conoid extrusion. However, the combined use of ionophore with extracellular Ca2+ results not only in a higher proportion of cells extruding their conoids, but the population also maintains extruded conoids for longer times, an advantageous trait for increasing invasion efficiency. The inhibition of conoid extrusion by nifedipine agrees with the Ca2+ entry enhancement effect on this trait.

Other studies have found some evidence for the role of extracellular Ca2+ in the lytic cycle of T. gondii. Lovett and Sibley (33) demonstrated that release of Ca2+ via ryanodine-sensitive stores was enhanced in the presence of extracellular Ca2+. Importantly, without extracellular Ca2+, ryanodine was incapable of stimulating microneme secretion. Treatment of parasites with caffeine (an agonist of ryanodine receptors) also elicited release of stored Ca2+. Although this release was enhanced in the presence of extracellular Ca2+, it was not necessary for stimulating microneme secretion. These results support the assertion that extracellular Ca2+ enhances virulence-related traits. Such enhancement was also observed in previous experiments on gliding motility (34) and conoid extrusion. Mondragon and Frixione (7) observed enhanced conoid extrusion in parasites that were treated with ionomycin. As observed in this study, ionomycin was able to initiate a significant response in conoid extrusion, but when combined with extracellular Ca2+, the response was more robust. Likewise, previous publications have established that although Ca2+ ionophores were sufficient to induce Ca2+ mobilization, through their probable effect on intracellular stores, the presence of extracellular Ca2+ resulted in greater microneme secretion (6).

The lytic cycle of T. gondii is complex, and the parasite does not simply invade a host cell, replicate until host cell integrity is lost, and then egress and begin the process anew. In fact, studies show that parasites commonly invade and exit with little or no replication (35, 36). Such complex invasion behavior, all of which is dependent on Ca2+, likely requires the replenishing of intracellular stored Ca2+ with extracellular Ca2+. Similarly, the process of egress is dependent on Ca2+ (8). A parsimonious feature for the parasites is to utilize the extracellular Ca2+ available to supplement invasion-dependent processes and to also resupply intracellular stores to use during reinvasion or to initiate egress.

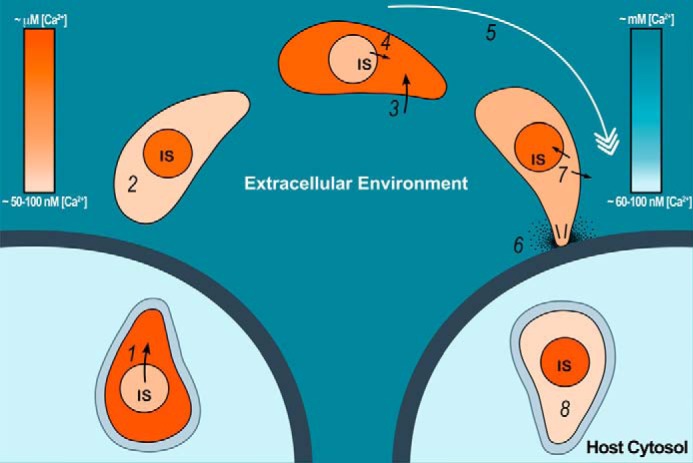

Our model of invasion events, timing of intracellular Ca2+ release, and extracellular Ca2+ entry is shown in Fig. 8. Intracellular stores are depleted upon egress, and the parasites need to replenish them when they come in contact with the high Ca2+ of the extracellular environment. This wave of Ca2+ influx enhances invasion-related traits. Active Ca2+ pumping to intracellular compartments and to the extracellular space will allow control of the cytosolic Ca2+ levels after signaling events.

FIGURE 8.

Model for the role of Ca2+ entry in the lytic cycle of T. gondii. The proposed model shows Ca2+ changes in the cytosol and intracellular stores (IS) of the parasite when exposed to changes in extraparasite Ca2+ concentrations during the lytic cycle of T. gondii. Step 1, cytoplasmic Ca2+ [Ca2+]i increases in the tachyzoite (darker orange) before egress because of Ca2+ release from intracellular stores. Step 2, once outside the parasite, [Ca2+]i returns to nanomolar levels (lighter orange). Step 3, because of large electrochemical gradient, extracellular Ca2+ (represented by darker blue) enters parasite cytosol through the regulated mechanisms observed in this study (darker orange in tachyzoite). Step 4, according to our data, release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores could contribute to this increase by an unknown mechanism. Step 5, an increase in cytosolic Ca2+ would lead to initiation of invasion. Step 6, gliding, conoid extrusion, microneme secretion, and invasion. Step 7, the parasite [Ca2+]i (lighter orange) decreases by the action of Ca2+ pumps at the plasma membrane and the SERCA at the ER. This last event would result in replenishment of the intracellular stores. Step 8, tachyzoite invades its host cell and forms a parasitophorous vacuole where it resides and replicates exposed to host [Ca2+]i (∼50–100 nm). The blue color bar represents relative extraparasite Ca2+ concentration. The orange color bar represents parasite Ca2+ concentration. The arrows show Ca2+ fluxes. The black lines and dots on invading parasites represent conoid extrusion and microneme secretion, respectively. (Christina A. Moore drew the model.)

In conclusion, our data points toward a general mechanism of Ca2+ entry, which may not be sensitive to the filling state of the ER but that could work in parallel to elevate intracellular Ca2+ to activate downstream events essential for initiating biological processes like invasion-linked traits. Our thorough analysis of Ca2+ entry and its role during the lytic cycle of T. gondii will set the precedent for future discoveries of the molecules involved in this crucial process. To our knowledge, this is the first study that links regulation of Ca2+ entry to virulence traits of a unicellular pathogen.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Gary S. Bird and James W. Putney for suggestions and Drs. L. David Sibley, Vern Carruthers, and John Boothroyd for antibodies. We thank Samantha Lie Tjauw and Thayer King for excellent technical help. We also thank Christina Moore for the design of the model for Fig. 8.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants AI096836 (to S. N. J. M.) and AI101167 (to V. J.) and National Institutes of Health T32 Training Grant AI060546 (to D. A. P. and the Center for Tropical and Emerging Global Diseases).

This article contains supplemental Videos S1 and S2.

- ORAI

- store-operated channel

- STIM

- stromal interaction molecule

- EB

- extracellular buffer

- IB

- intracellular buffer

- SOCE

- store-operated Ca2+ entry

- TG

- thapsigargin

- SERCA

- sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase

- 2-APB

- 2-aminomethoxydiphenyl borate

- Bay K

- Bay K-8644

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance

- IO

- ionomycin

- VGCC

- voltage-gated calcium Ca2+ channel.

REFERENCES

- 1. Berridge M. J., Bootman M. D., Roderick H. L. (2003) Calcium signalling: dynamics, homeostasis and remodelling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 4, 517–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Parekh A. B., Putney J. W., Jr. (2005) Store-operated calcium channels. Physiol. Rev. 85, 757–810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cai X. (2008) Unicellular Ca2+ signaling “toolkit” at the origin of metazoa. Mol. Biol. Evol. 25, 1357–1361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Black M. W., Boothroyd J. C. (2000) Lytic cycle of Toxoplasma gondii. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64, 607–623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wetzel D. M., Chen L. A., Ruiz F. A., Moreno S. N., Sibley L. D. (2004) Calcium-mediated protein secretion potentiates motility in Toxoplasma gondii. J. Cell Sci. 117, 5739–5748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Carruthers V. B., Sibley L. D. (1999) Mobilization of intracellular calcium stimulates microneme discharge in Toxoplasma gondii. Mol. Microbiol. 31, 421–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mondragon R., Frixione E. (1996) Ca2+-dependence of conoid extrusion in Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoites. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 43, 120–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Arrizabalaga G., Boothroyd J. C. (2004) Role of calcium during Toxoplasma gondii invasion and egress. Int. J. Parasitol. 34, 361–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lovett J. L., Sibley L. D. (2003) Intracellular calcium stores in Toxoplasma gondii govern invasion of host cells. J. Cell Sci. 116, 3009–3016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vieira M. C., Moreno S. N. (2000) Mobilization of intracellular calcium upon attachment of Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoites to human fibroblasts is required for invasion. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 106, 157–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Docampo R., Moreno S. N., Plattner H. (2014) Intracellular calcium channels in protozoa. Eur. J. Pharmacol. pii:S0014–2999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schwab J. C., Beckers C. J., Joiner K. A. (1994) The parasitophorous vacuole membrane surrounding intracellular Toxoplasma gondii functions as a molecular sieve. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91, 509–513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Miranda K., Pace D. A., Cintron R., Rodrigues J. C., Fang J., Smith A., Rohloff P., Coelho E., de Haas F., de Souza W., Coppens I., Sibley L. D., Moreno S. N. (2010) Characterization of a novel organelle in Toxoplasma gondii with similar composition and function to the plant vacuole. Mol. Microbiol. 76, 1358–1375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Moreno S. N., Zhong L. (1996) Acidocalcisomes in Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoites. Biochem. J. 313, 655–659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Grynkiewicz G., Poenie M., Tsien R. Y. (1985) A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J. Biol. Chem. 260, 3440–3450 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kafsack B. F., Beckers C., Carruthers V. B. (2004) Synchronous invasion of host cells by Toxoplasma gondii. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 136, 309–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Beraldo F. H., Mikoshiba K., Garcia C. R. (2007) Human malarial parasite, Plasmodium falciparum, displays capacitative calcium entry: 2-aminoethyl diphenylborinate blocks the signal transduction pathway of melatonin action on the P. falciparum cell cycle. J. Pineal. Res. 43, 360–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Smyth J. T., Lemonnier L., Vazquez G., Bird G. S., Putney J. W., Jr. (2006) Dissociation of regulated trafficking of TRPC3 channels to the plasma membrane from their activation by phospholipase C. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 11712–11720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lacampagne A., Gannier F., Argibay J., Garnier D., Le Guennec J. Y. (1994) The stretch-activated ion channel blocker gadolinium also blocks L-type calcium channels in isolated ventricular myocytes of the guinea-pig. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1191, 205–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bootman M. D., Collins T. J., Mackenzie L., Roderick H. L., Berridge M. J., Peppiatt C. M. (2002) 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2-APB) is a reliable blocker of store-operated Ca2+ entry but an inconsistent inhibitor of InsP3-induced Ca2+ release. FASEB J. 16, 1145–1150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Capiod T. (2011) Cell proliferation, calcium influx and calcium channels. Biochimie 93, 2075–2079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yamamoto H., Hwang O., Van Breemen C. (1984) Bay K8644 differentiates between potential and receptor operated Ca2+ channels. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 102, 555–557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wan K. L., Carruthers V. B., Sibley L. D., Ajioka J. W. (1997) Molecular characterisation of an expressed sequence tag locus of Toxoplasma gondii encoding the micronemal protein MIC2. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 84, 203–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Carruthers V. B., Giddings O. K., Sibley L. D. (1999) Secretion of micronemal proteins is associated with Toxoplasma invasion of host cells. Cell Microbiol. 1, 225–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Christel C., Lee A. (2012) Ca2+-dependent modulation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1820, 1243–1252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Putney J. W., Jr. (1986) A model for receptor-regulated calcium entry. Cell Calcium 7, 1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Prole D. L., Taylor C. W. (2011) Identification of intracellular and plasma membrane calcium channel homologues in pathogenic parasites. PLoS One 6, e26218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Collins S. R., Meyer T. (2011) Evolutionary origins of STIM1 and STIM2 within ancient Ca2+ signaling systems. Trends Cell Biol. 21, 202–211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. King N., Westbrook M. J., Young S. L., Kuo A., Abedin M., Chapman J., Fairclough S., Hellsten U., Isogai Y., Letunic I., Marr M., Pincus D., Putnam N., Rokas A., Wright K. J., Zuzow R., Dirks W., Good M., Goodstein D., Lemons D., Li W., Lyons J. B., Morris A., Nichols S., Richter D. J., Salamov A., Sequencing J. G., Bork P., Lim W. A., Manning G., Miller W. T., McGinnis W., Shapiro H., Tjian R., Grigoriev I. V., Rokhsar D. (2008) The genome of the choanoflagellate Monosiga brevicollis and the origin of metazoans. Nature 451, 783–788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dunlap K., Luebke J. I., Turner T. J. (1995) Exocytotic Ca2+ channels in mammalian central neurons. Trends Neurosci. 18, 89–98 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nagamune K., Sibley L. D. (2006) Comparative genomic and phylogenetic analyses of calcium ATPases and calcium-regulated proteins in the apicomplexa. Mol. Biol. Evol. 23, 1613–1627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pezzella N., Bouchot A., Bonhomme A., Pingret L., Klein C., Burlet H., Balossier G., Bonhomme P., Pinon J. M. (1997) Involvement of calcium and calmodulin in Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoite invasion. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 74, 92–101 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lovett J. L., Marchesini N., Moreno S. N., Sibley L. D. (2002) Toxoplasma gondii microneme secretion involves intracellular Ca2+ release from inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3)/ryanodine-sensitive stores. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 25870–25876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mondragon R., Meza I., Frixione E. (1994) Divalent cation and ATP dependent motility of Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoites after mild treatment with trypsin. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 41, 330–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tomita T., Yamada T., Weiss L. M., Orlofsky A. (2009) Externally triggered egress is the major fate of Toxoplasma gondii during acute infection. J. Immunol. 183, 6667–6680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Koshy A. A., Dietrich H. K., Christian D. A., Melehani J. H., Shastri A. J., Hunter C. A., Boothroyd J. C. (2012) Toxoplasma co-opts host cells it does not invade. PLoS Pathog. 8, e1002825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.