Abstract

Background: Mechanisms regulating androgen receptor (AR) subcellular localization represent an essential component of AR signaling. Karyopherins are a family of nucleocytoplasmic trafficking factors. In this paper, we used the yeast model to study the effects of karyopherins on the subcellular localization of the AR. Methods: Yeast mutants deficient in different nuclear transport factors were transformed with various AR based, GFP tagged constructs and their localization was monitored using microscopy. Results: We showed that yeast can mediate androgen-induced AR nuclear localization and that in addition to the import factor, Importinα/β, this process required the import karyopherin Sxm1. We also showed that a previously identified nuclear export sequence (NESAR) in the ligand binding domain of AR does not appear to rely on karyopherins for cytoplasmic localization. Conclusions: These results suggest that while AR nuclear import relies on karyopherin activity, AR nuclear export and/or cytoplasmic localization may require other undefined mechanisms.

Keywords: Androgen receptor, karyopherin, nucleocytoplasmic trafficking

Introduction

There are many mechanisms that regulate transcriptional activity. One potential aspect of transcription regulation is the subcellular localization of transcription factors. It is evident that transcription factors need to be in the nucleus in order to access target genes. Mislocalization of transcription factors can have profound consequences and result in the development of disease. The androgen receptor is a transcription factor whose activity is androgen regulated and is a key player in prostate cancer. Previous studies have shown an association of AR localization with progression of the disease [1,2]. To understand the underlying mechanisms that contribute to AR subcellular localization, we looked at a family of nuclear transport factors, the karyopherins, to see if they play a role in AR subcellular localization.

The effects of androgen in prostate cancer are mediated by the androgen receptor (AR). AR is a ligand dependent transcription factor that regulates the expression of androgen response genes. The prevailing theory is that in the absence of androgen, AR is localized to the cytoplasm and is transcriptionally inactive [3-7]. Upon ligand binding, AR is transported to the nucleus where it is transcriptionally active [3,5,6,8-10]. When androgen is withdrawn, the unliganded AR is exported from the nucleus to the cytoplasm where it is again transcriptionally inactive [9].

Previous studies suggest that the subcellular localization of AR is altered in the transition of prostate cancer from an androgen sensitive to an androgen insensitive (which is currently called castration-recurrent or -resistant) state [11]. In androgen-sensitive prostate cancer cells, AR is localized to the cytoplasm in the absence of androgens. However, AR is localized to the nucleus in castration-resistant prostate cancer cells even in androgen depleted conditions in both culture and clinical specimens [1,2]. In addition, nuclear localized AR was transcriptionally active even in the absence of ligand [12,13].

One determinant of subcellular localization is nucleocytoplasmic trafficking. Entry and exit of proteins and RNA from the nucleus occurs through the nuclear pore. Molecules that are 40 kDa or smaller can diffuse through the nuclear pore. Larger molecules, however, require import and export factors for transport across the nuclear membrane (reviewed in [14]). The best-studied class of nuclear transport receptors is the family of importin-β-like proteins called karyopherins which utilize the small Ras family GTPase, Ran. Fourteen karyopherin family members have been identified in yeast based on their similarity to importinβ and members are categorized as either importins or exportins primarily on their observed trafficking of known cargos reviewed in [14,15].

Although it is evident that AR plays a central role in prostate cancer and that its subcellular localization is an important component in the regulation of its activity, there is still incomplete understanding of the underlying mechanisms that govern AR’s subcellular localization. AR subcellular localization is ligand-dependent [3-6,10]. There is a bipartite nuclear localization signal (NLS) similar in amino acid sequence to the SV40 NLS located within the DNA-binding domain/hinge region (DBD/HR) and is recognized by the importinα/β complex [6,10,16]. An NLS2 also was identified in the ligand binding domain (LBD) and believed to play a key role in ligand-mediated transport, however, this signal is not well characterized [17-19]. A similar NLS2 sequence is present in glucocorticoid receptor (GR) and was implicated in ligand-dependent nuclear localization mediated by Sxm1/importin 7 [20,21]. Since steroid hormone receptors share several characteristics, it is reasonable to hypothesize that AR ligand-dependent nuclear localization likely occurs by the same mechanism. This, however, has not been established.

Mechanisms governing AR nuclear export have been more elusive. There are reports that suggest that calreticulin plays a role in steroid receptor export [22,23]. However, there has been some debate regarding its role [24,25]. Work in our lab identified a nuclear export signal (NES) for AR. We demonstrated that a 75 amino acid sequence in the ligand-binding domain (LBD) (residues 743-817) of AR was both necessary and sufficient to result in cytoplasmic localization of AR. This sequence was termed NESAR [17]. Similar sequences were also found in the estrogen receptor (ER) and mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) and were also found to mediate cytoplasmic localization of a GFP marker [17]. Studies also suggest that AR nuclear export is Crm-1 independent. Crm-1 recognizes proteins containing leucine rich NESs and targets them for nuclear export. AR does not contain a leucine rich NES, nor was its nuclear export blocked by exposure to leptomycin B, an inhibitor of Crm-1 [9,17,26].

Yeast has been successfully used to study the function of a number of steroid nuclear receptors including AR, the glucocorticoid receptor (GR), the estrogen receptor (ER), and the mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) [20,27-31]. In previous studies, S. cerevisiae was manipulated to reproduce transcriptional activation of steroid receptors upon addition of ligand [20,29]. These studies demonstrate that yeast have the basic machinery to mediate steroid receptor action. For the purposes of this study, yeast also offers the distinct advantage of having readily available karyopherin genetic mutants.

In this paper, we report that androgen can induce AR nuclear localization in yeast and such ligand-dependent nuclear localization is mediated by Sxm1/importin 7. We also present evidence that NESAR is functional in yeast and independent of Crm-1 and other karyopherins.

Materials and methods

Constructs

All constructs were cloned into p416 GDP (URA) yeast expression vector backbone for constitutive expression of the fusion protein (ATCC, Manassas, VA). To generate the reporter constructs 2GFP-NLSSV40, the nuclear localization signal from SV40 T-antigen (PKKKRKV) was cloned between two EGFP sequences. For 2GFP-NLSSV40-NESPKI, the nuclear export signal from protein kinase inhibitor (PKI) (ELALKLAGLDIN) was cloned at the C-terminus of the second EGFP sequence of 2GFP-NLSSV40 construct. For 2GFP-NLSSV40-NESAR, the nuclear export signal from the androgen receptor (residues 743-817 from AR, [17]) was cloned at the C-terminus of second EGFP sequence of 2GFP-NLSSV40 construct. For GFP-AR, the full length human AR was cloned at the C-terminus of an EGFP sequence. The Sxm1 rescue plasmid was generated by cloning a wild type genomic copy of Sxm1 obtained by PCR into p415 GPD (LEU) vector.

Yeast strains, handling, transformations, and localization studies

For localization studies, BY4741 (wild-type strain) (ATCC) were grown in YPD or SD media (Clontech, Mountain View, CA) supplemented with appropriate amino acids at 30°C unless otherwise noted. Yeast was transformed by the lithium acetate method [32]. Cells were diluted the following day to OD595 0.1 and grown to about OD595 0.4 in SD media. For Hoechst staining of yeast cells, Hoechst 33342 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) was added to a final concentration of 250 nM 45 minutes prior to visualization. For visualization, 2 μl of yeast culture was spotted on a slide, cover-slipped, and protein localization was assessed by fluorescence microscopy with 100X oil immersion lens on the Nikon TE2000 inverted microscope using Metamorph software.

Mutant strains

crm1-1/xpo1-1 [33] (gift from K. Weis, UC Berkeley), msn5Δ [34] (gift from E. O’Shea, UCSF), pdr6Δ [35] (gift from J. Curcio, Wadsworth Center, NY). kap95/importin-β/rsl1-4 [36], sxm1Δ [37], pse1-1 [37]. kap120Δ [38], kap104Δ [39], kap123Δ [37], los1Δ [40,41], cse1-1 [42], mtr10-1 [43], ndm5Δ [44], kap114Δ [45,46] (gifts from P.A. Silver, Dana arber Cancer Institute).

For localization experiments with mutant strains, yeast were grown and visualized as above with the following exceptions. For Sxm1 nuclear import studies, yeast were grown in overnight cultures in the appropriate SD media supplemented with appropriate amino acids at 30°C in the presence of 1 μM DHT or vehicle control. Cells were diluted the following day to OD595 0.1 and grown to about OD595 0.4 in SD media with or without DHT. Yeast were treated with Hoechst and visualized as above.

Heat sensitive mutants crm-1, pse1-1/kap121, kap104, and mtr10-1/kap111 were grown in SD media supplemented with appropriate amino acid at 25°C. Cells were diluted the following day to OD595 0.1 and grown to about OD595 0.4. Yeast were grown at restrictive temperatures for the appropriate time (crm-1/xpo1: 37°C, 5 min; pse1-1/kap121: 36°C, 1 hr; kap104 37°C, 3 hrs; mtr10-1/kap111: 37°C, 2 hrs) and were then treated with Hoechst prior to visualization.

Results

Androgens regulate AR subcellular localization in yeast

Previous studies have shown that AR transcriptional activity can be activated in S. cerevisiae using androgens, suggesting that exogenously expressed AR can be localized to the nucleus [29]. However, it is not known if this transcription is preceded by the ligand-dependent import of AR or if AR was already present in the nucleus and that addition of androgens only activates transcriptional activity. To determine if the addition of androgen induces the import of AR in yeast, we transformed wild-type yeast (BY4741) with GFP-AR (Figure 1A) and added either DHT or ethanol to the culture media. In the absence of androgen, GFP-AR is localized evenly in the nucleus and the cytoplasm (Figure 2, -DHT). However, after the addition of 1 μM DHT, GFP-AR accumulated in the nucleus (Figure 2, +DHT). This suggests that AR nuclear localization can be induced by androgen addition in yeast and that AR responds in a similar manner in yeast as in mammalian cells and therefore the mechanism for AR import is evolutionarily conserved.

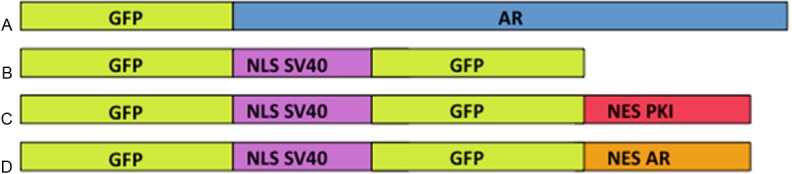

Figure 1.

Constructs used to test the ability of NESAR and AR localization in yeast. All sequences were cloned into yeast p416 GPD expression vector containing a URA3 marker and GPD promoter for constitutive expression. A. Construct of GFP-tagged full length human androgen receptor and will be referred to as GFP-AR. B. Construct containing two GFPs and NLS from SV40 used as a nuclear localization control and will referred to as 2GFP-NLSSV40. C. Construct with two GFPs, NLS from SV40 and nuclear export signal from protein kinase inhibitor (NESPKI) used for cytoplasmic localization control and will be referred to as 2GFP-NLSSV40-NESPKI. D. Construct with two GFPs, NLS from SV40 and nuclear export sequence from AR and will be referred to as 2GFP-NLSSV40-NESAR. Constructs are not drawn to scale. GFP, green fluorescent protein; NLS, nuclear localization signal; NES, nuclear export signal. SV40, Simian vacuolating virus 40.

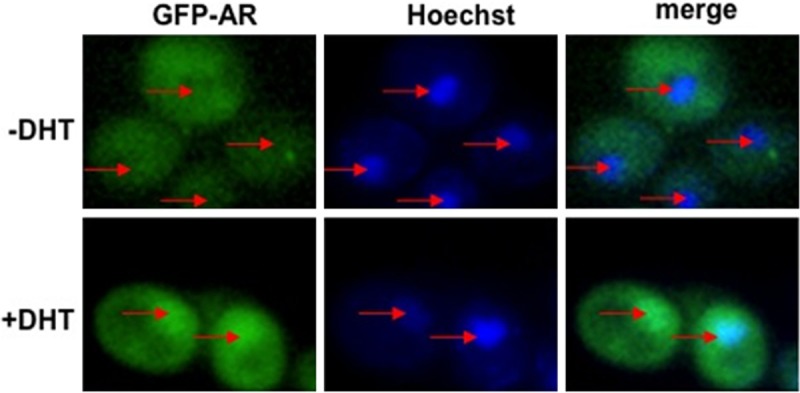

Figure 2.

Yeast can mediate ligand dependent AR nuclear localization. Wild-type yeast strain (BY4741) was transformed with GFP-AR and grown in the absence (-DHT) or the presence (+DHT) of ligand. Nuclei were stained with Hoechst. The localization of GFP-AR and Hoechst staining was determined by fluorescence microscopy. In the absence of ligand, GFP-AR is evenly distributed in wild-type yeast. In the presence of ligand, GFP-AR is localized to the nucleus. Red arrows indicate yeast nuclei. DHT, 5α-dihydrotestosterone.

Sxm1 is required for androgen-induced nuclear localization in yeast

We have demonstrated that the addition of androgen results in the nuclear localization of AR in yeast, but the mechanism by which this occurs is not evident. Experiments on GR provide insight into this question. Freedman and Yamamoto, using a yeast model, demonstrated that the ligand dependent nuclear localization of GR is dependent on the import karyopherin Sxm1 [20]. To determine if AR is imported using the same mechanism, we transformed yeast deficient in Sxm1 (sxm1Δ) with GFP-AR and compared the localization of the fusion protein to that in wild-type yeast. In media lacking androgen, GFP-AR is evenly distributed throughout the yeast cell (Figure 2, -DHT). When DHT was added to the media, GFP-AR was predominantly localized to the nucleus (Figure 2, +DHT). When we treated sxm1Δ yeast strain with DHT, GFP-AR remained evenly distributed among the nuclear and cytoplasmic compartments (Figure 3, sxm1Δ+DHT). When we restored Sxm1 function by transforming in a wild-type copy of Sxm1, we were able to restore nuclear localization of GFP-AR in the presence of ligand (Figure 3, sxm1Δ+ Sxm1+DHT). These experiments demonstrate that Sxm1 is required for AR ligand dependent nuclear localization. These experiments also suggest that steroid receptors use a conserved mechanism for ligand-dependent nuclear localization.

Figure 3.

Sxm1 is required for ligand dependent nuclear localization of AR. sxm1Δ yeast strain was transformed with GFP-AR alone or GFP-AR and a WT copy of Sxm1 (+Sxm1) and grown in the presence ligand (+DHT). Nuclei were stained with Hoechst. The localization of GFP-AR and Hoechst staining was determined by fluorescence microscopy. In the sxm1Δ mutant, the ligand induced nuclear localization that was observed in wild-type yeast was abrogated. When a wild-type copy was reintroduced into the sxm1Δ mutant, ligand dependent nuclear localization of GFP-AR was restored. Red arrows indicate yeast nuclei. Sxm1, Suppressor of mRNA export mutant.

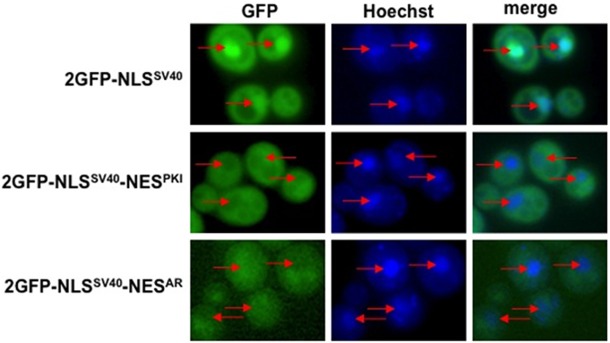

NESAR is functional and dominant over NLSSV40 in yeast

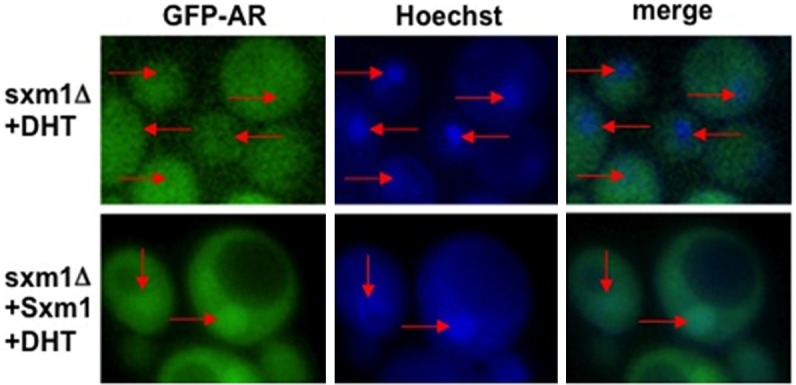

In mammalian cells, NESAR has been demonstrated to localize proteins to the cytoplasm [17]. In order to determine if NESAR cytoplasmic localization was dependent on karyopherins in yeast, we first needed to assess the ability of the NESAR to function in yeast. We generated GFP fusion proteins that contained NLS from SV40 (NLSSV40) and with either the nuclear export signal from protein kinase inhibitor (NESPKI) (Figure 1C) or NESAR (Figure 1D) and transformed them into wild-type yeast cells. We then determined the localization of these GFP fusion proteins using fluorescence microscopy. We found that the fusion protein that contained the NLSSV40 alone localized strongly to the nucleus (Figure 4; 2GFP-NLSSV40). The GFP fusion protein containing both the NLSSV40 and the NESPKI, which is Crm-1 mediated, was strongly cytoplasmic (Figure 4; 2GFP-NLSSV40-NESPKI). In the yeast transformed with the fusion protein containing the NLSSV40 and NESAR, we did not observe a strong nuclear GFP signal as with NLSSV40 alone, however, the cytoplasmic localization was less distinct than that observed with the NLSSV40-NESPKI fusion protein (Figure 4; 2GFP-NLSSV40-NESAR). This suggests that NESAR is functional and that the effect of NESAR is dominant over that of the NLSSV40 in yeast.

Figure 4.

NESAR abrogates NLSSV40 nuclear localization: Wild-type yeast strain BY4741 was transformed with the indicated constructs and nuclei were stained with Hoechst. GFP localization and Hoechst staining were viewed using fluorescence microscopy. Yeast transformed with 2GFP-NLSSV40 displayed nuclear localization. Yeast transformed with 2GFP-NLSSV40-NESPKI displayed cytoplasmic localization. Yeast transformed with 2GFP-NLSSV40-NESAR abrogated NLSSV40 nuclear localization but did not display strong cytoplasmic GFP localization as that seen in 2GFP-NLSSV40-NESPKI. Red arrows indicate yeast nuclei. PKI, protein kinase inhibitor.

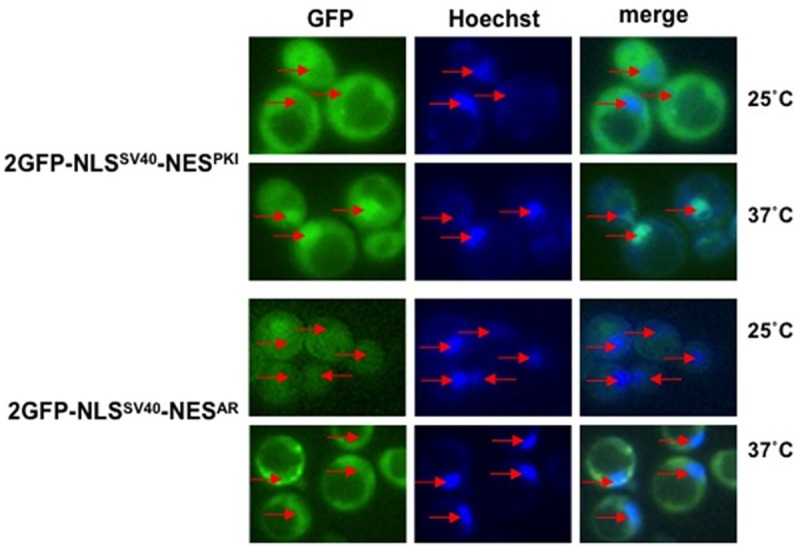

Crm-1 is not required for NESAR-mediated cytoplasmic localization

Previous experiments in mammalian cells have used the inhibitor leptomycin B to determine if Crm-1 plays a role in AR nuclear export. In these studies, the addition of leptomycin B did not inhibit the nuclear export of either the GFP-tagged full length AR, nor a GFP-tagged ligand binding domain (LBD) [9,17]. To understand the mechanism of NESAR-mediated cytoplasmic localization, we examined the behavior of NESAR in a yeast crm-1 mutant. The yeast crm-1 mutant is heat sensitive and is nonfunctional at non-permissive temperatures. We transformed a crm-1 mutant with fusion protein 2GFP-NLSSV40, 2GFP-NLSSV40-NESPKI, or 2GFP-NLSSV40-NESAR and looked for GFP localization. At permissive temperatures (25°C), the 2GFP-NLSSV40-NESPKI and 2GFP-NLSSV40-NESAR fusionproteins were localized to the cytoplasm. When crm-1 mutant strain were shifted to non-permissive temperatures (37°C), 2GFP-NLSSV40-NESPKI was found predominantly localized to the nucleus while localization of 2GFP-NLSSV40-NESAR remained in cytoplasm (Figure 5). 2GFP-NLSSV40 was localized to the nucleus at both 25°C and 37°C (data not shown). These results demonstrate that NESAR-mediated cytoplasmic localization is Crm-1 independent. Furthermore, this result, in part, supports the findings that AR export is not inhibited by leptomycin B and thus not Crm-1 dependent.

Figure 5.

Crm-1 mutant does not affect cytoplasmic localization of 2GFP-NLSSV40-NESAR. Yeast crm1-1 heat sensitive mutant strain was transformed with either 2GFP-NLSSV40-NESPKI or 2GFP-NLSSV40-NESAR. Nuclei were stained with Hoechst. GFP localization and Hoechst staining was viewed using fluorescence microscopy. At permissive temperature, (25°C) 2GFP-NLSSV40-NESPKI and 2GFP-NLSSV40-NESAR are both localized in the cytoplasm. However, at non-permissive temperature (37°C), 2GFP-NLSSV40-NESPKI was found in the nucleus, while 2GFP-NLSSV40-NESAR localization remained unchanged. Red arrows indicate yeast nuclei.

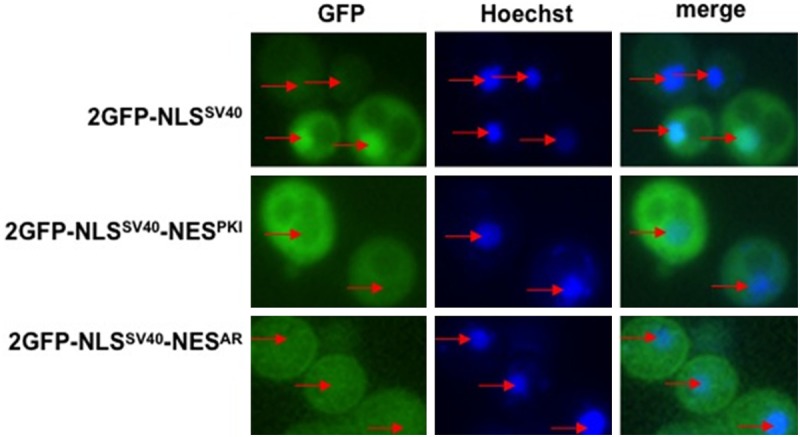

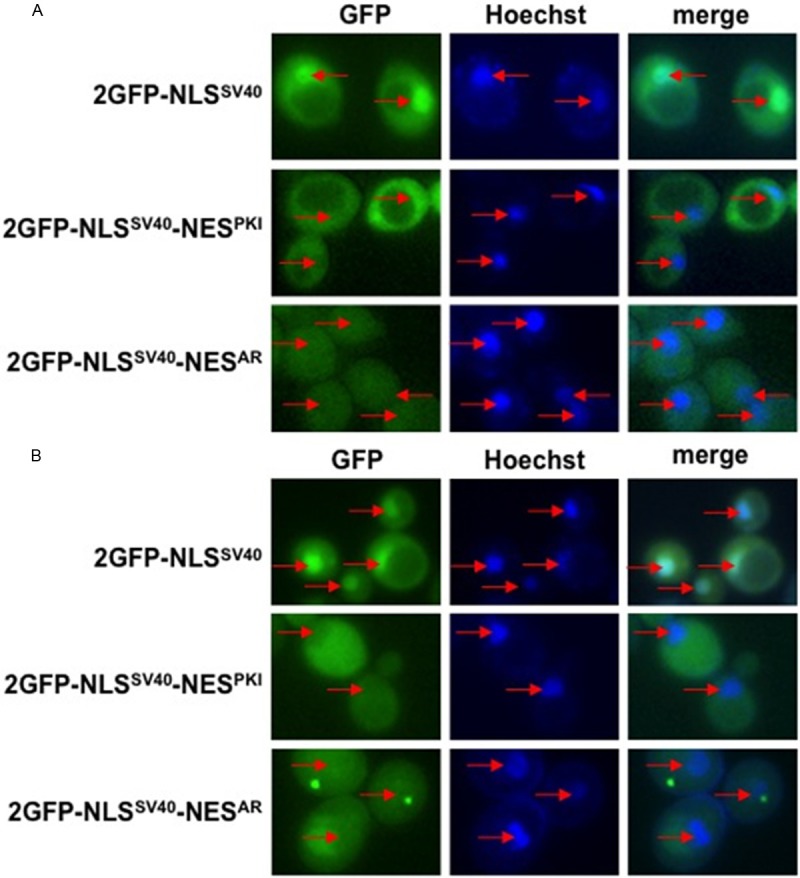

Other export mutants do not affect NESAR-mediated cytoplasmic localization

Export karyopherins other than Crm-1 have been identified in yeast. They include Los1, Msn5, and Cse1. To test if these factors play a role in NESAR-mediated cytoplasmic localization, we again transformed the fusion protein 2GFP-NLSSV40, 2GFP-NLSSV40-NESPKI, or 2GFP-NLSSV40-NESAR into either a los1Δ or msn5Δ deletion mutant and looked for GFP localization. We did not observe a difference in localization of any of the GFP fusion protein in either msn5Δ (Figure 6A) or los1Δ (Figure 6B) mutants as compared to wild-type yeast. These results suggest that neither Los1 nor Msn5 play a role in NESAR-mediated cytoplasmic localization.

Figure 6.

Other export karyopherins do not affect NESAR localization. Yeast msn5Δ and los1Δ deletion mutants were transformed with the indicated constructs. Nuclei were stained with Hoechst. GFP localization and Hoechst staining was viewed using fluorescence microscopy. The localization of the GFP fusion proteins in (A) msn5Δ or (B) los1Δ was indistinguishable from that found in wild-type yeast. Red arrows indicate location of nuclei.

We were unable to test the cse-1 mutant because Cse-1 also plays a critical role in nuclear import. Cse-1 exports Importinα and our test constructs all contain an NLSSV40 which relies on Importinα for nuclear import. Furthermore, AR’s NLS1 is similar to NLSSV40 which has been shown to also depend on Importinα for nuclear import. Thus, Cse-1 almost certainly has an effect on AR subcellular localization. To date, Cse-1 has not been implicated in the export of any other proteins; therefore it is unlikely to contribute to NESAR-mediated cytoplasmic localization.

Import mutants do not affect NESAR-mediated cytoplasmic localization

There are very few well characterized nuclear import and export signals and most of the karyopherins have been categorized as importins or exportins based on their observed functions. It is possible that importins could play a yet undiscovered role in nuclear export. Indeed this was the case with Msn5 which was originally categorized as an exportin and subsequently was found to also have a role in nuclear import [47]. Therefore we decided to test the importins to determine if they would have an effect on NESAR-mediated cytoplasmic localization. We transformed yeast strains containing deletions of the importin genes with the fusion protein 2GFP-NLSSV40, 2GFP-NLSSV40-NESPKI, or 2GFP-NLSSV40-NESAR. Mutant kap123Δ did not display any differences in the subcellular localization of any GFP fusion proteins as compared to wild-type yeast (Figure 7). Similar results were found in kap114Δ, nmd5Δ sxm1Δ, kap122Δ, kap120Δ pse1-1/kap121, kap104, and mtr10/kap111 (data not shown). These results suggest that defined import karyopherins also do not play a role in NESAR-mediated cytoplasmic localization.

Figure 7.

Import karyopherins do not affect NESAR localization. Yeast import karyopherin mutants were transformed with the indicated constructs. Nuclei were stained with Hoechst. GFP localization and Hoechst staining was viewed using fluorescence microscopy. Shown here is yeast kap123Δ deletion mutant strain as representative of other import mutants. The localization of the GFP fusion proteins in these import mutants was indistinguishable from that found in wild-type yeast. Red arrows indicate location of nuclei.

Discussion

In order to elucidate the mechanisms underlying the subcellular localization of AR, we chose to look at the fundamental processes of nuclear import and export. Key to this process is a family of nucleocytoplasmic trafficking factors called the karyopherins. Currently, the only undisputed role for a karyopherin in AR trafficking is that of importinα. AR has a canonical bipartite NLS that is recognized by Importinα [6,10,16]. A recent in vitro study of the structural basis of the nuclear import of AR demonstrated that importinα exclusively binds to the second part of the bipartite NLS located in the hinge region [48]. Furthermore, this association is increased in the presence of ligand indicating that importinα plays a role in ligand dependent and ligand independent nuclear localization of AR [48]. The other karyopherin that has been scrutinized for perhaps having a role in AR localization is Crm-1 [9,17,33]. Crm-1 has been identified as a nuclear export factor for numerous proteins. Many of these proteins contain a hydrophobic leucine-rich NES similar to that of the HIV rev protein [49]. It is generally thought that Crm-1 is not responsible for AR nuclear export. This belief is based on evidence that neither AR nor the LBDAR’s redistribution into the cytoplasm after hormone withdrawal was affected by leptomycin B, an inhibitor of Crm-1 [9,17].

In this paper, we attempt to determine if and which of the other karyopherins plays a role in AR subcellular localization. To answer this question, we chose the yeast model because of the advantages it offered. Yeast is a very genetically tractable system and multiple studies have used yeast to help understand steroid receptor activity. In addition, because many nuclear import and export studies have been performed in yeast, mutant strains are available for the karyopherins which greatly facilitated our studies [15]. In this study we found that when yeast was exposed to DHT, GFP-AR localized to the nucleus. This demonstrated that AR ligand dependent nuclear localization could occur in yeast, suggesting that yeast had the molecular factors necessary for ligand dependent import of AR. This further suggests that this import mechanism is conserved. There were, however, some significant differences between yeast and mammalian cell AR import. AR import in yeast required a much higher concentration (1 μM) as compared to mammalian cells (1 nM). In addition, AR import in yeast occurred over a period of hours while in mammalian cells it took a matter of minutes. These differences are not entirely surprising as yeast do not have steroid receptors and mammalian cells have likely evolved a means to increase the efficiency of this basic import mechanism.

An example of this is a study using yeast to examine the role of karyopherins in the nuclear import of GR. Using a yeast model system, the authors demonstrated that ligand dependent nuclear localization is dependent on a combination of importinα and Sxm1 [20]. Since steroid receptors share many common features and are regulated by the same mechanisms, we wanted to determine if Sxm1 also played a role in AR nuclear import. When GFP-AR was expressed in an Sxm1 deficient mutant, it failed to localize to the nucleus upon ligand addition. The restoration of Sxm1 function rescued the GFP-AR nuclear phenotype suggesting that Sxm1 is required in AR ligand dependent nuclear localization as with GR. These results reflect the similarities in the nuclear steroid receptors and lend credence to the idea that this pathway is evolutionarily conserved. Sxm1 and its mammalian ortholog, importin 7, share roughly 23% identity [50]. These results suggest that at the core, these orthologs can perform similar functions, but their difference may be reflected in the efficiency of import of various cargos.

The role of karyopherins in AR nuclear export has been less clear. A previously described NES that was located in the LBD (NESAR) was shown to direct cytoplasmic localization of GFP-AR fusion protein in a prostate cancer cell line [17]. The mechanism by which this occurred was not known. We found that when a GFP tagged fusion construct containing an NLSSV40 and NESAR was expressed in yeast, there was a loss of predominant GFP nuclear localization as was seen with GFP tagged NLSSV40 alone. This was similar to the phenotype seen in prostate cancer cells where the NESAR was dominant over the NLS1 of AR. This also suggested that yeast possessed the components necessary for NESAR-mediated cytoplasmic localization.

To determine if karyopherins played a role in NESAR-mediated cytoplasmic localization, we transformed karyopherin mutants with the 2GFP-NLSSV40-NESAR fusion protein and looked to see if its localization was affected. Previous experiments looking at Crm-1 as an export factor have concluded that AR nuclear export occurs through a Crm-1 independent pathway [9,17]. In our study, there was no difference in the GFP localization of the crm-1 mutant and wild-type yeast strain, corroborating these earlier findings. In addition we tested two other yeast export karyopherins, Los1 and Msn5. We found that the loss of these proteins also did not affect GFP localization. We were unable to test Cse-1’s role in NESAR export because our assay requires a functional import mechanism to induce nuclear localization of 2GFP-NLSSV40- NESAR. Cse-1 mutation inactivates the import mechanism because it functions to recycle Importinα back into the cytoplasm. Interestingly, the human ortholog of Cse1, CAS (Cellular Apoptosis Susceptibility protein), has a role in regulating select p53 target genes, not through its export activity, rather via an association with chromatin and serve as a barrier protein that prevents spreading of heterochromatin [51]. Overall, our results suggest that NESAR-mediated nuclear export does not rely on yeast export karyopherins.

The categorization of karyopherins has primarily been based on their observed import or export of specific cargos [14,15]. Thus, whether they are exclusively importin or exportins is not conclusive. This is the case with Msn5. Msn5 acts as an export factor for Pho4, but acts an import factor for replication protein complex A [34,47]. We therefore decided to test a number of import karyopherins to determine if they play a part in NESAR-mediated cytoplasmic localization. None of the import karyopherins we tested affected GFP localization. Taken together, these experiments suggest that karyopherins do not play a significant role in NESAR-mediated cytoplasmic localization. There are caveats to this conclusion. One is that multiple karyopherins may mediate NESAR activity and that they may functionally compensate for each other, and therefore the functional loss of a single karyopherin would not result in a phenotypic change. Another possibility that cannot be ruled out is that mammalian karyopherins with no comparable yeast ortholog may play a role. However, that the phenotypes in yeast and mammalian cells are very similar argue that this mechanism is conserved.

In this study, we show that yeast is an excellent model to study the mechanism of AR intracellular trafficking and that AR subcellular localization is, in part, dependent on karyopherins. It was previously shown that importinα is a critical component of AR nuclear import. Here we show that Sxm1 also is required for ligand-induced AR nuclear import. Thus far, there is no clear evidence that karyopherins are directly involved in AR nuclear export. Our observation that NESAR-mediated localization is independent of the yeast exportins and importin supports the idea that karyopherins are not involved. The question that arises is if karyopherins are not involved in AR export, then which factors are? Perhaps the steady state cytoplasmic GFP-NESAR fusion protein expression observed in prostate cancer cells occurs through a mechanism other than karyopherin mediated nuclear export such as cytoplasmic retention. It would be a worthwhile pursuit to determine what other pathways and molecular factors are involved and how they interact with each other to regulate AR subcellular localization.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to K. Weis from UC Berkeley, E. O’Shea from UCSF, J. Curcio from Wadsworth Center, and P.A. Silver from Dana Farber Cancer Institute for providing yeast mutants. We would like to thank the members of the Wang lab, especially Dan Wang, for their critical reading of this manuscript. This work was supported by NIH R01 CA108675, ACS #PF-05-229-01-CSM, NIH R37 DK51193, NIH 1 P50 CA90386, NIH Training Grant T32 CA080621, DOD DAMD17-01-1-0088, CIHR MT-15291 and the Mellam Foundation.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Gregory CW, He B, Johnson RT, Ford OH, Mohler JL, French FS, Wilson EM. A mechanism for androgen receptor-mediated prostate cancer recurrence after androgen deprivation therapy. Cancer Res. 2001;61:4315–4319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gregory CW, Johnson RT Jr, Mohler JL, French FS, Wilson EM. Androgen receptor stabilization in recurrent prostate cancer is associated with hypersensitivity to low androgen. Cancer Res. 2001;61:2892–2898. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Georget V, Lobaccaro JM, Terouanne B, Mangeat P, Nicolas JC, Sultan C. Trafficking of the androgen receptor in living cells with fused green fluorescent protein-androgen receptor. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1997;129:17–26. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(97)04034-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roy AK, Tyagi RK, Song CS, Lavrovsky Y, Ahn SC, Oh TS, Chatterjee B. Androgen receptor: structural domains and functional dynamics after ligand-receptor interaction. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;949:44–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb04001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simental JA, Sar M, Lane MV, French FS, Wilson EM. Transcriptional activation and nuclear targeting signals of the human androgen receptor. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:510–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jenster G, Trapman J, Brinkmann AO. Nuclear import of the human androgen receptor. Biochem J. 1993;293:761–768. doi: 10.1042/bj2930761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pratt WB, Galigniana MD, Morishima Y, Murphy PJ. Role of molecular chaperones in steroid receptor action. Essays Biochem. 2004;40:41–58. doi: 10.1042/bse0400041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Georget V, Terouanne B, Lumbroso S, Nicolas JC, Sultan C. Trafficking of androgen receptor mutants fused to green fluorescent protein: a new investigation of partial androgen insensitivity syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:3597–3603. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.10.5201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tyagi RK, Lavrovsky Y, Ahn SC, Song CS, Chatterjee B, Roy AK. Dynamics of intracellular movement and nucleocytoplasmic recycling of the ligand-activated androgen receptor in living cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2000;14:1162–1174. doi: 10.1210/mend.14.8.0497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou ZX, Sar M, Simental JA, Lane MV, Wilson EM. A ligand-dependent bipartite nuclear targeting signal in the human androgen receptor. Requirement for the DNA-binding domain and modulation by NH2-terminal and carboxyl-terminal sequences. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:13115–13123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feldman BJ, Feldman D. The development of androgen-independent prostate cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2001;1:34–45. doi: 10.1038/35094009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang ZQ, Li J, Wong J. AR possesses an intrinsic hormone-independent transcriptional activity. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16:924–937. doi: 10.1210/mend.16.5.0829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang L, Johnson M, Le KH, Sato M, Ilagan R, Iyer M, Gambhir SS, Wu L, Carey M. Interrogating androgen receptor function in recurrent prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2003;63:4552–4560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sorokin AV, Kim ER, Ovchinnikov LP. Nucleocytoplasmic transport of proteins. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2007;72:1439–1457. doi: 10.1134/s0006297907130032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Damelin M, Silver PA, Corbett AH. Nuclear protein transport. Methods Enzymol. 2002;351:587–607. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)51870-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gorlich D, Kutay U. Transport between the cell nucleus and the cytoplasm. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1999;15:607–660. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.15.1.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saporita AJ, Zhang Q, Navai N, Dincer Z, Hahn J, Cai X, Wang Z. Identification and characterization of a ligand-regulated nuclear export signal in androgen receptor. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:41998–42005. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302460200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jenster G, van der Korput JA, Trapman J, Brinkmann AO. Functional domains of the human androgen receptor. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1992;41:671–675. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(92)90402-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Poukka H, Karvonen U, Yoshikawa N, Tanaka H, Palvimo JJ, Janne OA. The RING finger protein SNURF modulates nuclear trafficking of the androgen receptor. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:2991–3001. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.17.2991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Freedman ND, Yamamoto KR. Importin 7 and importin alpha/importin beta are nuclear import receptors for the glucocorticoid receptor. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:2276–2286. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-11-0839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Savory JG, Hsu B, Laquian IR, Giffin W, Reich T, Hache RJ, Lefebvre YA. Discrimination between NL1- and NL2-mediated nuclear localization of the glucocorticoid receptor. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:1025–1037. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.2.1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Black BE, Holaska JM, Rastinejad F, Paschal BM. DNA binding domains in diverse nuclear receptors function as nuclear export signals. Curr Biol. 2001;11:1749–1758. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00537-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holaska JM, Black BE, Rastinejad F, Paschal BM. Ca2+-dependent nuclear export mediated by calreticulin. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:6286–6297. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.17.6286-6297.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nguyen MM, Dincer Z, Wade JR, Alur M, Michalak M, Defranco DB, Wang Z. Cytoplasmic localization of the androgen receptor is independent of calreticulin. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2009;302:65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2008.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walther RF, Lamprecht C, Ridsdale A, Groulx I, Lee S, Lefebvre YA, Hache RJ. Nuclear export of the glucocorticoid receptor is accelerated by cell fusion-dependent release of calreticulin. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:37858–37864. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306356200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tyagi RK, Amazit L, Lescop P, Milgrom E, Guiochon-Mantel A. Mechanisms of progesterone receptor export from nuclei: role of nuclear localization signal, nuclear export signal, and ran guanosine triphosphate. Mol Endocrinol. 1998;12:1684–1695. doi: 10.1210/mend.12.11.0197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bovee TF, Helsdingen RJ, Hamers AR, van Duursen MB, Nielen MW, Hoogenboom RL. A new highly specific and robust yeast androgen bioassay for the detection of agonists and antagonists. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2007;389:1549–1558. doi: 10.1007/s00216-007-1559-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bureik M, Bruck N, Hubel K, Bernhardt R. The human mineralocorticoid receptor only partially differentiates between different ligands after expression in fission yeast. FEMS Yeast Res. 2005;5:627–633. doi: 10.1016/j.femsyr.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ceraline J, Erdmann E, Erbs P, Deslandres-Cruchant M, Jacqmin D, Duclos B, Klein-Soyer C, Dufour P, Bergerat JP. A yeast-based functional assay for the detection of the mutant androgen receptor in prostate cancer. Eur J Endocrinol. 2003;148:99–110. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1480099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chu WL, Shiizaki K, Kawanishi M, Kondo M, Yagi T. Validation of a new yeast-based reporter assay consisting of human estrogen receptors alpha/beta and coactivator SRC-1: Application for detection of estrogenic activity in environmental samples. Environ Toxicol. 2009;24:513–21. doi: 10.1002/tox.20473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim DH, Kim GS, Yun CH, Lee YC. Functional conservation of the glutamine-rich domains of yeast Gal11 and human SRC-1 in the transactivation of glucocorticoid receptor Tau 1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:913–925. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01140-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gietz RD, Woods RA. Transformation of yeast by lithium acetate/single-stranded carrier DNA/polyethylene glycol method. Methods Enzymol. 2002;350:87–96. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)50957-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stade K, Ford CS, Guthrie C, Weis K. Exportin 1 (Crm1p) is an essential nuclear export factor. Cell. 1997;90:1041–1050. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80370-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaffman A, Rank NM, O’Neill EM, Huang LS, O’Shea EK. The receptor Msn5 exports the phosphorylated transcription factor Pho4 out of the nucleus. Nature. 1998;396:482–486. doi: 10.1038/24898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Titov AA, Blobel G. The karyopherin Kap122p/Pdr6p imports both subunits of the transcription factor IIA into the nucleus. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:235–246. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.2.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Iovine MK, Watkins JL, Wente SR. The GLFG repetitive region of the nucleoporin Nup116p interacts with Kap95p, an essential yeast nuclear import factor. J Cell Biol. 1995;131:1699–1713. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.6.1699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seedorf M, Silver PA. Importin/karyopherin protein family members required for mRNA export from the nucleus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:8590–8595. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stage-Zimmermann T, Schmidt U, Silver PA. Factors affecting nuclear export of the 60S ribosomal subunit in vivo. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:3777–3789. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.11.3777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aitchison JD, Blobel G, Rout MP. Kap104p: a karyopherin involved in the nuclear transport of messenger RNA binding proteins. Science. 1996;274:624–627. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5287.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hopper AK, Schultz LD, Shapiro RA. Processing of intervening sequences: a new yeast mutant which fails to excise intervening sequences from precursor tRNAs. Cell. 1980;19:741–751. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(80)80050-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hurt DJ, Wang SS, Lin YH, Hopper AK. Cloning and characterization of LOS1, a Saccharomyces cerevisiae gene that affects tRNA splicing. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:1208–1216. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.3.1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xiao Z, McGrew JT, Schroeder AJ, Fitzgerald-Hayes M. CSE1 and CSE2, two new genes required for accurate mitotic chromosome segregation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:4691–4702. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.8.4691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kadowaki T, Chen S, Hitomi M, Jacobs E, Kumagai C, Liang S, Schneiter R, Singleton D, Wisniewska J, Tartakoff AM. Isolation and characterization of Saccharomyces cerevisiae mRNA transport-defective (mtr) mutants. J Cell Biol. 1994;126:649–659. doi: 10.1083/jcb.126.3.649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.He F, Jacobson A. Identification of a novel component of the nonsense-mediated mRNA decay pathway by use of an interacting protein screen. Genes Dev. 1995;9:437–454. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.4.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morehouse H, Buratowski RM, Silver PA, Buratowski S. The importin/karyopherin Kap114 mediates the nuclear import of TATA-binding protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:12542–12547. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pemberton LF, Rosenblum JS, Blobel G. Nuclear import of the TATA-binding protein: mediation by the karyopherin Kap114p and a possible mechanism for intranuclear targeting. J Cell Biol. 1999;145:1407–1417. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.7.1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yoshida K, Blobel G. The karyopherin Kap142p/Msn5p mediates nuclear import and nuclear export of different cargo proteins. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:729–740. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.4.729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cutress ML, Whitaker HC, Mills IG, Stewart M, Neal DE. Structural basis for the nuclear import of the human androgen receptor. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:957–968. doi: 10.1242/jcs.022103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kutay U, Guttinger S. Leucine-rich nuclear-export signals: born to be weak. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:121–124. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gorlich D, Dabrowski M, Bischoff FR, Kutay U, Bork P, Hartmann E, Prehn S, Izaurralde E. A novel class of RanGTP binding proteins. J Cell Biol. 1997;138:65–80. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.1.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tanaka T, Ohkubo S, Tatsuno I, Prives C. hCAS/CSE1L associates with chromatin and regulates expression of select p53 target genes. Cell. 2007;130:638–650. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]