Abstract

We examined attitudes and practices regarding tobacco cessation interventions of primary care physicians serving low income, minority patients living in urban areas with a high smoking prevalence. We also explored barriers and facilitators to physicians providing smoking cessation counseling to determine the need for and interest in deploying a tobacco-focused patient navigator at community-based primary care practice sites. A self-administered survey was mailed to providers serving Medicaid populations in New York City’s Upper Manhattan and areas of the Bronx. Provider counseling practices were measured by assessing routine delivery (≥80% of the time) of a brief tobacco cessation intervention (i.e., “5 A’s”). Provider attitudes were assessed by a decisional balance scale comprising 10 positive (Pros) and 10 negative (Cons) perceptions of tobacco cessation counseling. Of 254 eligible providers, 105 responded (41%). Providers estimated 22% of their patients currently use tobacco and nearly half speak Spanish. A majority of providers routinely asked about tobacco use (92%) and advised users to quit (82%), whereas fewer assisted in developing a quit plan (32%) or arranged follow-up (21%). Compared to providers reporting <80% adherence to the “5 A’s”, providers reporting ≥80% adherence tended to have similar mean Pros and Cons scores for Ask, Advise, and Assess but higher Pros and lower Cons for Assist and Arrange. Sixty four percent of providers were interested in providing tobacco-related patient navigation services at their practices. Although most providers believe they can help patients quit smoking, they also recognize the potential benefit of having a patient navigator connect their patients with evidence-based cessation services in their community.

Keywords: Tobacco cessation, Primary care, Healthcare providers, Minority health, Patient navigation

Introduction

Smoking remains the leading modifiable behavioral risk factor and cause of premature death in the United States [1] and may be the largest single contributor of health inequalities in low-income populations [2]. Over the past decade, state and local governments have implemented evidence-based public health and clinical interventions in order to reduce cigarette consumption [3–8]. In 2002, the New York City Department of Mental Health and Hygiene embarked on a comprehensive tobacco control program [3] and, within 7 years, smoking rates in New York City fell to one of the lowest in the Nation (15.8%) [9]. However, rates of smoking show marked variations according to income, education and race/ethnicity and are highest among immigrants, minorities, and persons of a lower socioeconomic status [10–12].

Although safe and efficacious tobacco cessation treatments exist [7], these evidence-based treatments tend to be underutilized, especially among low-income, ethnic/racial minority smokers. In New York State only 28% of patients used evidence-based treatment cessation services (medication and/or counseling) [13]. In addition, despite New York State’s widespread efforts to reduce barriers to access such as cost, language, and geographic distance, Spanish speaking and Medicaid smokers have lower utilization of the State Quitline than expected based on smoking prevalence rates [14–16].

Primary care providers have long been considered essential catalysts for cessation advice and assistance [17, 18]. Approximately 70% of all smokers are seen by a physician each year and even brief physician advice to quit smoking has been shown to be an effective smoking cessation intervention [7, 19]. The Public Health Service and US Preventive Services Task Force recently reaffirmed that clinicians should ask all adults about tobacco use and provide tobacco cessation interventions for those who use tobacco products (Grade A recommendation) [7, 20]. Providers are encouraged to follow the “5 A’s” brief, behavioral counseling framework (i.e., (1) Ask about tobacco use; (2) Advise quitting; (3) Assess willingness to quit; (4) Assist to quit; (5) Arrange follow-up) to promote tobacco cessation. Although national and statewide surveys typically reveal that providers routinely ask their patients about tobacco use and advise smokers to quit, providers are much less likely to complete the latter “5 A’s”, namely assessing willingness to quit, assisting smokers to quit, and arranging follow-up [21, 22]. Compounding this general tendency to forego the more intensive cessation treatment (i.e., less assessing, assisting and arranging follow-up), recent studies reveal marked disparities in primary care patterns with low income, black and Hispanic smokers being less likely to be asked about their smoking, advised to quit, or receive recommendations for use of evidence-based cessation pharmacotherapies [23–25].

Because of these disparities, innovative strategies are needed to help extend the reach and impact of physician-delivered advice and provide a bridge to community-based cessation services. Over the past decade, patient navigators have been used with increasing frequently to help patients access and overcome potential barriers to receiving quality cancer care [26, 27]. More recently, the use of patient navigators has been examined in primary care to extend a provider’s reach in promoting adherence to preventive health recommendations [28, 29]. The patient navigation model represents a promising strategy for meeting the Institute of Medicine’s criteria for quality health care (i.e., being safe, effective, patient centered, timely, efficient, and equitable) [30]. In terms of the “5 A’s”, patient navigators are ideally suited to perform “Assess,” “Assist,” and “Arrange,” interventions that require more time than primary care providers have been able and willing to provide [22]. In doing so, the navigator would concentrate on assisting smokers access evidence-based cessation interventions [31]. By arranging follow-up with the patient, the navigator also would be able to foster a sustained tobacco treatment intervention in the primary care setting [32, 33]. Ultimately, we hypothesize that lay patient navigators (i.e., former smokers from the same communities as the patients) can be trained and equipped with relevant knowledge, skills, and experience to address certain barriers specific to that patient population.

As part of a larger ongoing research project that aims to develop and apply a patient navigation model to reduce disparities in cessation treatment utilization, this study examined primary care physicians’ attitudes and practices with regard to smoking cessation interventions. Specifically, we solicited a sample of primary care providers treating low-income, minority patients in areas known to have high rates of smoking and low cessation treatment utilization rates and assessed the frequency with which they have been counseling and offering interventions to their smokers. In addition, we wanted to understand barriers and facilitators to providing smoking cessation counseling. Finally, to gather preliminary evidence regarding the feasibility of integrating patient navigation into primary care clinics, we collected preliminary data regarding primary care providers’ potential interest and perceived benefit of implementing a tobacco-focused patient navigator at community-based primary care practice sites.

Methods

Sample

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at The City College of New York and Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. Data were collected via a self-administered, anonymous survey mailed to a sample of primary care providers participating in a Medicaid-managed care program. Primary care providers (i.e., internists, family practitioners, and obstetrician/gynecologists) practicing in a zip code located within or in proximity to the targeted areas of either New York City’s East and Central Harlem and Washington Heights and Inwood (i.e., 10128, 10029, 10035, 10025–27, 10030, 10037, 10039, 10031-34, 10040) or three zip codes in the Bronx (10451, 10452, and 10454) that were in close proximity to Upper Manhattan were selected because of the high proportion of current smokers residing in these low income, urban, largely minority neighborhoods [34–37].

Eligible providers were mailed the survey in July 2009 with personalized cover letters, stamped return envelopes, and a $2 cash incentive, methods that have been found to maximize response rates from healthcare professionals [38]. A postcard for indicating contact information also was included for providers interested in participating in a future planned pilot patient navigation project. Follow-up phone calls and face-to-face visits were conducted.

Instruments

The 42-item questionnaire included sections pertaining to practice setting characteristics, tobacco cessation attitudes and practices, patient navigation, and personal background (demographic) information [39]. Provider attitudes were assessed by a validated decisional balance that consisted of 10 positive (Pros, α = 0.83) and 10 negative (Cons, α = 0.86) perceptions of tobacco cessation counseling. Individual items were measured on a 5-point Likert-type response format, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) [40]. The decisional balance scale has been found to be significantly associated with physicians’ readiness to deliver smoking cessation counseling [40] in that greater positive beliefs (Pros) about providing cessation counseling are associated with greater readiness, whereas greater negative beliefs (Cons) are associated with lower likelihood of providing cessation counseling [41]. Provider counseling practices were measured by assessing routine delivery (≥80% of the time) of the “5 A’s”. The items pertaining to patient navigation asked if physicians were familiar with the patient navigation model (yes/no) and assessed physicians’ perceptions of the effectiveness of having a staff person perform specified services for smokers.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS 15.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). Descriptive statistics were calculated for demographic characteristics and enactment of the “5 A’s”. Differences between groups were examined using chi-squared tests. For the decisional balance scales, raw scores for Pros and Cons were converted into T-scores. Bivariate correlations were used to assess the relationship between mean Pros and Cons T-scores and readiness to provide tobacco cessation services and interest in patient navigation. Reported p-values are two-sided and a value of less than .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographics

A total of 254 eligible providers received the survey packet and 105 providers completed surveys, yielding a response rate of 41.3%. The majority of physicians were between 40 and 59 years of age and the mean (SD) number of years since graduating medical school was 19.0 (9.8) (Table 1). Approximately 70% of providers were female and more than 50% self-identified as African American/Black, Asian American/Pacific Islander, or Latino/Hispanic. The most common area of practice was internal medicine (41.9%) followed by obstetrics/gynecology (28.6%). The providers estimated that approximately 22.1% of their patients are current tobacco users and that nearly half of their patients are Spanish speaking. While 23 (21.9%) providers reported being former smokers, only three (2.9%) providers reported currently smoking.

Table 1.

Characteristics of primary care providers

| Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 20–39 | 25 (24.0%) |

| 40–59 | 66 (63.5%) |

| 60 and older | 13 (12.5%) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 74 (70.5%) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| African American/Black | 20 (19.2%) |

| Asian American/Pacific Islander | 17 (16.3%) |

| Latino/Hispanic | 17 (16.3%) |

| White | 45 (43.3%) |

| Other | 6 (4.9%) |

| Area of practice | |

| Internal medicine | 44 (41.9%) |

| Family practice | 16 (15.2%) |

| OB/GYN | 30 (28.6%) |

| Others | 15 (14.3%) |

| Number of years since graduating medical school (n = 102) | |

| Mean (SD) | 19 (9.8) |

| Less than 10 | 21 (20.6%) |

| 11–20 | 41 (40.2%) |

| 21 and above | 40 (39.2%) |

| Smoking status | |

| Never smoker | 79 (75.2%) |

| Former smoker | 23 (21.9%) |

| Current smoker | 3 (2.9%) |

| Academic affiliation | |

| Yes | 75 (72.1%) |

| English speaking patients (%) | |

| Mean (SD) | 55.2 (28.6) |

| Spanish speaking patients (%) | |

| Mean (SD) | 45.1 (29.5) |

| Estimated smoking prevalence (%) | |

| Mean (SD) | 22.1 (16.6) |

Provision of the “5 A’s”

Table 2 illustrates the percentage of time that primary care providers routinely perform each of the “5 A’s” with ≥80% of their patients. Although the vast majority of providers routinely asked patients about tobacco use (92%) and advised tobacco users to quit (82.2%), only slightly more than half of the providers assessed tobacco users’ willingness to quit (57%). Similarly, even fewer assisted tobacco users in developing a quit plan (32%) or arranged follow-up contact (21.4%).

Table 2.

Physicians’ tobacco-related counseling practices (5 A’s)

| Intervention | Frequency and percent of physicians who perform the intervention with: |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥80% of patients 61–80% of patients 41–60% of patients 20–40% of patients <20% of patients | |||||

| Ask about smoking status | 92 (92.0%) | 6 (6.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.0%) | 1 (1.0%) |

| Advise smoking patients to quit | 83 (82.2%) | 12 (11.9%) | 4 (4.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (2.0%) |

| Assess willingness to quit | 57 (57.0%) | 26 (26.0%) | 5 (5.0%) | 6 (6.0%) | 6 (6.0%) |

| Assist smoking patients | 31 (32.0%) | 16 (16.5%) | 14 (14.4%) | 10 (10.3%) | 26 (26.8%) |

| Arrange follow-up for smoking patients | 21 (21.4%) | 11 (11.2%) | 17 (17.3%) | 13 (13.3%) | 36 (36.7%) |

Provider Attitudes toward Tobacco Cessation Counseling (Pros and Cons)

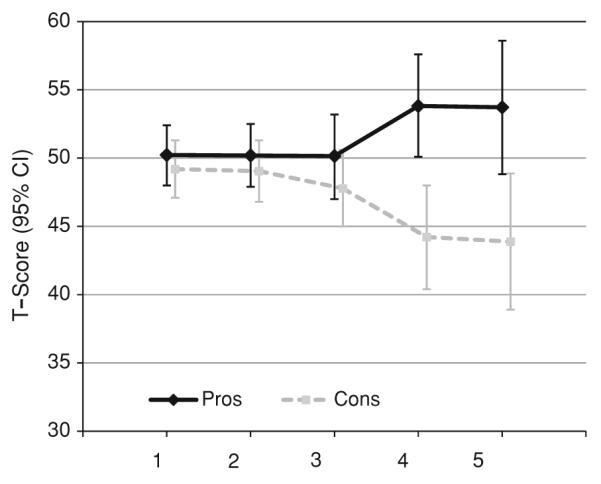

In terms of attitudes to deliver smoking cessation interventions, providers most strongly endorsed Pros related to the belief that doctors can be effective in tobacco cessation, physician counseling is effective, and physician advice is one of the best tobacco cessation interventions. On the other hand, the most highly endorsed Cons were the belief that smokers are non-compliant with tobacco cessation, cessation counseling is frustrating, and that physicians are unaware of the best cessation counseling strategies. Readiness to provide comprehensive cessation services (as measured on a 6-point scale from no expressed interest/concern to services fully integrated into care) was positively correlated with endorsement of Pros (r = 0.29, p = .004) and negatively correlated with endorsement of Cons (r = −0.37, p < .001). Provider attitudes also were related to performance of the “5 A’s” such that higher endorsement of Pros and lower ratings of Cons were associated with offering assistance (p = .01) and arranging (p = .03) for cessation services among providers (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Pros and cons of tobacco cessation counseling for providers who report at least 80% adherence to the 5 A’s for tobacco cessation

Readiness to Provide Tobacco Cessation Services

The three most frequently cited reasons for providers failing to provide smoking cessation advice and counseling to their patients were the perception of patients being unwilling or unmotivated to quit (30.2%), other health issues taking priority (27.9%), and lack of time (27.9%). In terms of awareness of community-based tobacco-cessation resources, 83% of providers were aware of the New York State Quitline while only 37% of providers knew about the New York State Fax-to-Quit Program, which allows providers to directly refer smokers to the Quitline. A minority of providers reported being familiar with formal cessation programs located in close proximity to their practice settings. When providers were asked what might make it easier to add or expand tobacco use cessation counseling within their practice, nearly two thirds (65.7%) cited greater knowledge of community referral sources and more than one third (37.3%) cited having staff with more training.

Awareness of and Interest in Patient Navigation

Although only 30% of providers had heard of patient navigation when provided with a brief explanation, 64% of respondents were interested in having a patient navigator help their patients make greater use of the available tobacco services in their local community. In terms of perceived benefits of patient navigation, 83.4% believed a patient navigator would be helpful for following up with patients they advised to quit, 85.4% believed a patient navigator would help identify barriers to quitting, 88.2% believed a patient navigator would help patients find solutions to problems in quitting, and 89.4% believed a patient navigator would help motivate smokers to quit. Thirty-seven providers (35%) returned postcards expressing interest in a patient navigator to assist in their practice.

Finally, we examined provider demographics, cessation attitudes, and practice setting characteristics that may have been associated with providers’ interest in patient navigation. Interest in patient navigation was positively correlated with endorsement of Pros (r = 0.42, p < .001) and negatively correlated with endorsement of Cons (r = −0.22, p = .04) of providing tobacco cessation services. No other covariates were associated with interest in patient navigation.

Discussion

Our study supports the need to identify strategies to support primary care providers’ delivery of brief cessation counseling. Similar to other investigators [22], we found that providers routinely ask patients about smoking and advise their tobacco-dependent patients to quit; however, assisting and arranging follow-up are more inconsistently performed. Implementing these steps requires having time to counsel smokers, the ability to follow-up with regard to continued counseling, and knowledge of available and accessible statewide and community-based smoking cessation resources.

Provider Practices

Our data confirm prior work that provider attitudes regarding the Pros and Cons of smoking cessation are associated with self-reported counseling practices [40]. However, the impact of these attitudes is more pronounced in the later steps of the “5 A’s” (i.e., assist and arrange). As noted, these steps tend to be more time and resource intensive.

Vogt and colleagues [42] found that a significant minority of primary care providers holds beliefs and attitudes unlikely to facilitate discussions about smoking cessation and the three most prevalent negative beliefs were the time needed to discuss smoking, a perceived lack of effectiveness of such discussions, and a perceived lack of skill in conducting such discussions. Meredith and colleagues [43] examined the impact of attitudes on behaviors and showed that primary care providers with more favorable attitudes toward smoking cessation counseling were more likely to report counseling and referring patients to a smoking-cessation program. However, Litaker and colleagues [44] found that physician attitudes are necessary but are not sufficient to guarantee the delivery of preventive care and that patient- and practice-level barriers must be considered.

Implications for Tobacco-Related Patient Navigation

The majority of providers expressed interest in integrating a patient navigation model into their practices and perceived numerous benefits in terms of assisting their patients to quit smoking. These findings suggest that providers may be receptive to working with patient navigators to promote tobacco cessation in the primary care setting. Despite the evidence that tobacco cessation treatment is efficacious for low income, minority smokers [7], these smokers are significantly less likely to seek any type of cessation treatment or to receive assistance in quitting from their primary care provider [45, 46]. Because most providers do not routinely implement all 5 A’s, we hypothesize that patient navigators might follow-up with assessment of willingness to quit and provision of additional counseling strategies such as problem solving, social support, and motivational strategies [47]. The navigator would be able to address practical, patient-level factors that our provider respondents cited as being barriers of particular relevance to the low income, minority smokers [48].

Interestingly, providers were more likely to cite patient-level barriers (i.e., motivation of patients) and practice-related barriers (i.e., amount of time needed and competing health issues) than lack of training in cessation treatment. This finding may reflect the comprehensive tobacco control plan implemented in New York City beginning in 2002 [3, 49]. Despite reporting relatively high rates of awareness of community-based cessation resources, the majority of providers felt that having fuller knowledge of such resources would enable them to be more effective in treating tobacco dependence within their own practice.

Utilizing patient navigators for behavioral risk factor modification might be helpful in linking patients with available and accessible tobacco cessation resources. Despite the concept of patient navigation having been developed two decades ago for the purposes of eliminating barriers to diagnosis and treatment of cancer in the Harlem community [50], only a minority of providers was familiar with the concept of patient navigation.

Strengths and Limitations

Our study has a number of limitations inherent in this type of research. First, our findings are based upon self-report and previous work indicates that physicians tend to over-report their own delivery of preventive counseling services [51, 52]. However, even if over-reporting is present, few providers claim to be administering all 5 A’s as their standard of routine care (≥80% of the time). Second, given our purposive sampling frame, the generalizability is limited to primary care providers practicing in underserved areas. Third, our response rate was 41% and, while considered reasonable for an anonymous provider survey [38,53], nonresponse bias might have influenced our observed results. If nonresponders had less favorable attitudes of smokers and were less likely to counsel smokers, the level of care provided to smokers would be even lower. Because the provider survey was anonymous, we were unable to determine which providers from our mailing list had responded to our survey and which providers had failed to respond (and why).

Conclusions

Our premise is that patient navigators are in a unique position to address many of the barriers observed in promoting tobacco cessation in routine clinical practice. Our next step is to design and develop a tobacco cessation training curriculum for lay patient navigators. We then will examine the acceptability and utility of a lay patient navigator trained to address barriers to using existing evidence-based cessation services as a means of implementing a novel treatment delivery service for low income, minority smokers. In addition, the misconceptions about effective cessation treatment could be addressed with the intent of promoting greater use of evidence-based smoking cessation treatment in local communities.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute #U54CA13778/U54CA132378 CCNY/MSKCC Partnership and T32CA009461. The authors appreciate the feedback provided by Jack Burkhalter on an earlier draft of this manuscript.

Contributor Information

Erica I. Lubetkin, Department of Community Health and Social Medicine, The Sophie Davis School of Biomedical Education at The City College of New York, 160 Convent Avenue, H400, New York, NY 10031, USA

Wei-Hsin Lu, Department of Community Health and Social Medicine, The Sophie Davis School of Biomedical Education at The City College of New York, 160 Convent Avenue, H400, New York, NY 10031, USA; wlu@ccny.cuny.edu.

Paul Krebs, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, 641 Lexington Avenue, 7th Floor, New York, NY 10022, USA; krebsp@mskcc.org.

Howa Yeung, Department of Community Health and Social Medicine, The Sophie Davis School of Biomedical Education at The City College of New York, 160 Convent Avenue, H400, New York, NY 10031, USA; howa.yeung@gmail.com.

Jamie S. Ostroff, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, 641 Lexington Avenue, 7th Floor, New York, NY 10022, USA; ostroffj@mskcc.org

References

- 1.Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA. 2004;291(10):1238–1245. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.10.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jha P, Peto R, Zatonski W, Boreham J, Jarvis MJ, Lopez AD. Social inequalities in male mortality, and in male mortality from smoking: Indirect estimation from national death rates in England and Wales, Poland, and North America. Lancet. 2006;368(9533):367–370. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68975-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frieden TR, Mostashari F, Kerker BD, Miller N, Hajat A, Frankel M. Adult tobacco use levels after intensive tobacco control measures: New York City, 2002–2003. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95(6):1016–1023. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.058164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biener L, Aseltine RH, Jr, Cohen B, Anderka M. Reactions of adult and teenaged smokers to the Massachusetts tobacco tax. American Journal of Public Health. 1998;88(9):1389–1391. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.9.1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fichtenberg CM, Glantz SA. Association of the California Tobacco Control Program with declines in cigarette consumption and mortality from heart disease. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;343(24):1772–1777. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200012143432406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fichtenberg CM, Glantz SA. Effect of smoke-free workplaces on smoking behaviour: Systematic review. BMJ. 2002;325(7357):188–194. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7357.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Public Health Service . Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. US Department of Health and Human Services; Rockville, MD: 2008. p. 257. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhu SH, Anderson CM, Tedeschi GJ, et al. Evidence of real-world effectiveness of a telephone quitline for smokers. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;347(14):1087–1093. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa020660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene [Accessed 23 Feb 2010];New York City smoking rates fall to lowest rate on record. 2010 Available at: http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/html/pr2009/pr023-09.shtml.

- 10.US Department of Health and Human Services . Healthy People 2010. With understanding and improving health and objectives for improving health 2 vols. 2nd ed US Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kendzor DE, Businelle MS, Mazas CA, et al. Pathways between socioeconomic status and modifiable risk factors among African American smokers. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2009;32(6):545–557. doi: 10.1007/s10865-009-9226-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laveist TA, Thorpe RJ, Jr, Mance GA, Jackson J. Overcoming confounding of race with socio-economic status and segregation to explore race disparities in smoking. Addiction. 2007;102(Suppl 2):65–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01956.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.New York State Dept of Health . Smoking cessation in New York State. New York State Dept of Health; Albany, NY: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 14.New York State Smokers’ Quitline New York State Quitline E-News. 2007 from http://www.nysmokefree.com/newweb/eletters/NYSQL2007Vol1Issue2.pdf.

- 15.U.S. Census Bureau Demographic profile: New York State. 2000 Retrieved from http://www.empire.state.ny.us/nysdc/census2000/DemoProfiles/DP1NewYorkState.pdf.

- 16.Brecher C, Lynam E, Spiezio S. Medicaid in New York: Why is New York’s program the most expensive in the nation and what to do about it. Citizens Budget Commission; Albany, NY: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frank E, Winkelby MA, Altman DG, Rockhill B, Fortmann SP. Predictors of physician’s smoking cessation advice. JAMA. 1991;266(22):3139–3144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manley M, Epps R, Husten C, Glynn T, Shopland D. Clinical interventions in tobacco control: A National Cancer Institute training program for physicians. JAMA. 1991;266(22):3172–3173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lemmens V, Oenema A, Knut IK, Brug J. Effectiveness of smoking cessation interventions among adults: A systematic review of reviews. European Journal of Cancer Prevention. 2009;17(6):535–544. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e3282f75e48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Counseling and interventions to prevent tobacco use and tobacco-caused disease in adults and pregnant women: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force reaffirmation recommendation statement. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2009;150(8):551–555. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-8-200904210-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quinn VP, Stevens VJ, Hollis JF, et al. Tobacco cessation services and patient satisfaction in nine nonprofit HMOs. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2005;29(2):77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chase EC, McMenamin SB, Halpin HA. Medicaid provider delivery of the 5 A’s for smoking cessation counseling. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2007;9(11):1095–1101. doi: 10.1080/14622200701666344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cokkinides VE, Halpern MT, Barbeau EM, Ward E, Thun MJ. Racial and ethnic disparities in smoking-cessation interventions: Analysis of the 2005 National Health Interview Survey. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2008;34(5):404–412. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Irvin Vidrine J, Reitzel LR, Wetter DW. The role of tobacco in cancer health disparities. Curr Oncol Rep. 2009;11(6):475–481. doi: 10.1007/s11912-009-0064-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lopez-Quintero C, Crum RM, Neumark YD. Racial/ethnic disparities in report of physician-provided smoking cessation advice: Analysis of the 2000 National Health Interview Survey. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(12):2235–2239. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.071035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Cancer Institute NCI’s patient navigator research program: Fact sheet. 2008 Retrieved from http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/factsheet/PatientNavigator.

- 27.Dohan D, Schrag D. Using navigators to improve care of underserved patients: Current practices and approaches. Cancer. 2005;104(4):848–855. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andrews JO, Felton G, Ellen Wewers M, Waller J, Tingen M. The effect of a multi-component smoking cessation intervention in African American women residing in public housing. Research in Nursing and Health. 2007;30(1):45–60. doi: 10.1002/nur.20174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martinez-Bristow Z, Sias JJ, Urquidi UJ, Feng C. Tobacco cessation services through community health workers for Spanish-speaking populations. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(2):211–213. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.063388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Institute of Medicine . Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Institute of Medicine . Ending the tobacco problem: A blueprint for the nation. National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cantrell J, Shelley D. Implementing a fax referral program for quitline smoking cessation services in urban health centers: A qualitative study. BMC Family Practice. 2009;10:81. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-10-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Curry SJ, Keller PA, Orleans CT, Fiore MC. The role of health care systems in increased tobacco cessation. Annual Review of Public Health. 2008;29:411–428. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Olson EC, Van Wye G, Kerker B, Thorpe L, Frieden TR. Take Care Central Harlem. no. 42. 2nd ed Vol. 20. NYC Community Health Profiles; 2006. pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Olson EC, Van Wye G, Kerker B, Thorpe L, Frieden TR. Take Care East Harlem. no. 42. 2nd ed Vol. 21. NYC Community Health Profiles; 2006. pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Olson EC, Van Wye G, Kerker B, Thorpe L, Frieden TR. Take Care Highbridge and Morrisania. no. 42. 2nd ed Vol. 6. NYC Community Health Profiles; 2006. pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Olson EC, Van Wye G, Kerker B, Thorpe L, Frieden TR. Take Care Hunts Point and Mott Haven. no. 42. 2nd ed Vol. 7. NYC Community Health Profiles; 2006. pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Asch DA, Jedrziewski MK, Christakis NA. Response rates to mail surveys published in medical journals. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1997;50(10):1129–1136. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00126-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cruz G, Ostroff JS, Kumar JV, Gajendra S. Preventing and detecting oral cancer. Oral health care providers’ readiness to provide health behavior counseling and oral cancer examinations. Journal of the American Dental Association. 2005;136(5):594–601. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2005.0230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Park ER, Eaton CA, Goldstein MG, et al. The development of a decisional balance measure of physician smoking cessation interventions. Preventive Medicine. 2001;33(4):261–267. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Park ER, DePue JD, Goldstein MG, et al. Assessing the transtheoretical model of change constructs for physicians counseling smokers. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2003;25(2):120–126. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2502_08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vogt F, Hall S, Marteau TM. General practitioners’ and family physicians’ negative beliefs and attitudes towards discussing smoking cessation with patients: A systematic review. Addiction. 2005;100(10):1423–1431. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meredith LA, Yano EM, Hickey SC, Sherman SE. Primary care provider attitudes are associated with smoking cessation counseling and referral. Medical Care. 2005;43(9):929–934. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000173566.01877.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Litaker D, Flocke SA, Frolkis JP, Stange KC. Physicians’ attitudes and preventive care delivery: Insights from the DOPC study. Preventive Medicine. 2005;40(5):556–563. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maher JE, Rohde K, Dent CW. Is a statewide tobacco quitline an appropriate service for specific populations? Tob Control. 2007;16(Suppl 1):i65–i70. doi: 10.1136/tc.2006.019786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Levinson AH, Pérez-Stable EJ, Espinoza P, Flores ET, Byers TE. Latinos report less use of pharmaceutical aids when trying to quit smoking. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2004;26(2):105–111. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2003.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sussman S, Sun P, Dent CW. A meta-analysis of teen cigarette smoking cessation. Health Psychology. 2006;25(5):549–557. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.5.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Blumenthal D. Barriers to the provision of smoking cessation services reported by clinicians in underserved communities. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. 2007;20(3):272–279. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2007.03.060115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Larson K, Levy J, Rome TD, Silver LD, Frieden TR. Public health detailing: A strategy to improve the delivery of clinical preventive services in New York City. Public Health Reports. 2006;121:228–234. doi: 10.1177/003335490612100302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Harold P. Freeman Patient Navigation Institute. Retrieved from http://www.hpfreemanpni.org/

- 51.McPhee SJ, Richard RJ, Solkowitz SN. Performance of cancer screening in a university general internal medicine practice: Comparison with the 1980 American Cancer Society Guidelines. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1986;1(5):275–281. doi: 10.1007/BF02596202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Montaño DE, Phillips WR. Cancer screening by primary care physicians. A comparison of rates obtained from physician self-report, patient survey, and chart audit. American Journal of Public Health. 1995;85(6):795–800. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.6.795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shosteck H, Fairweather WR. Physician response rates to mail and personal interview surveys. Public Opinion Q. 1979;43(2):206–217. doi: 10.1086/268512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]