Abstract

One of the biggest challenges in tumour research is the possibility to reprogram cancer cells towards less aggressive phenotypes. In this study, we reprogrammed primary Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM)-derived cells towards a more differentiated and less oncogenic phenotype by activating the Wnt pathway in a hypoxic microenvironment. Hypoxia usually correlates with malignant behaviours in cancer cells, but it has been recently involved, together with Wnt signalling, in the differentiation of embryonic and neural stem cells. Here, we demonstrate that treatment with Wnt ligands, or overexpression of β-catenin, mediate neuronal differentiation and halt proliferation in primary GBM cells. An hypoxic environment cooperates with Wnt-induced differentiation, in line with our finding that hypoxia inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) is instrumental and required to sustain the expression of β-catenin transcriptional partners TCF-1 and LEF-1. In addition, we also found that Wnt-induced GBM cell differentiation inhibits Notch signalling, and thus gain of Wnt and loss of Notch cooperate in the activation of a pro-neuronal differentiation program. Intriguingly, the GBM sub-population enriched of cancer stem cells (CD133+ fraction) is the primary target of the pro-differentiating effects mediated by the crosstalk between HIF-1α, Wnt, and Notch signalling. By using zebrafish transgenics and mutants as model systems to visualize and manipulate in vivo the Wnt pathway, we confirm that Wnt pathway activation is able to promote neuronal differentiation and inhibit Notch signalling of primary human GBM cells also in this in vivo set-up. In conclusion, these findings shed light on an unsuspected crosstalk between hypoxia, Wnt and Notch signalling in GBM, and suggest the potential to manipulate these microenvironmental signals to blunt GBM malignancy.

Keywords: Wnt, Hypoxia, Notch, glioblastoma stem cells

Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) is the most common malignant tumour occurring in the central nervous system, and one of the most devastating human malignancies.1 A fraction of GBM cells express markers typical of neural progenitor cells (i.e., CD133, Sox2, Musashi1, Bmi1, and Nestin). In vitro, this fraction of cells can be maintained as self-renewing population, or induced to differentiate into multiple cell types, depending on appropriate culturing conditions.2, 3, 4 These discoveries have contributed to the notion that brain tumours arise from a specific subset of cells defined as neural cancer stem cells (CSCs).5 CSCs seem to be characterized by low rates of cell division6 and high DNA repair capacity,7, 8, 9 features that may explain their resistance to classical chemo- and radio-therapies. Indeed, tumours relapsing after these treatments recapitulate the heterogeneity of the original tumour mass.

Forcing differentiation of CSCs may represent a potential effective therapeutic strategy. However, our limited understanding of the molecular pathways involved in their identity currently frustrates this route. Wnt signalling has recently been suggested to regulate differentiation of normal neural progenitors, promoting neurogenesis in the murine adult hippocampus,10 a hypoxic brain zone in which adult neural stem cells (NSCs) reside.11 Hypoxia has been reported to promote canonical Wnt signalling activation, enhancing NSC differentiation and neuronal maturation by co-operating with β-catenin activation.12 However, the possibility of an interaction between Wnt and the hypoxic signalling in the context of brain tumours remains unexplored.

This study aimed to investigate the effects of Wnt pathway activation on patient-derived GBM cells and stem-like cells derived from them. In particular, we found that Wnt activation promotes neuronal differentiation of GBM cancer cells under hypoxia, and that these effects are exerted by antagonizing Notch signalling, leading to: (1) upregulation of pro-neuronal genes and (2) inhibition of stemness-related pathways.

Results

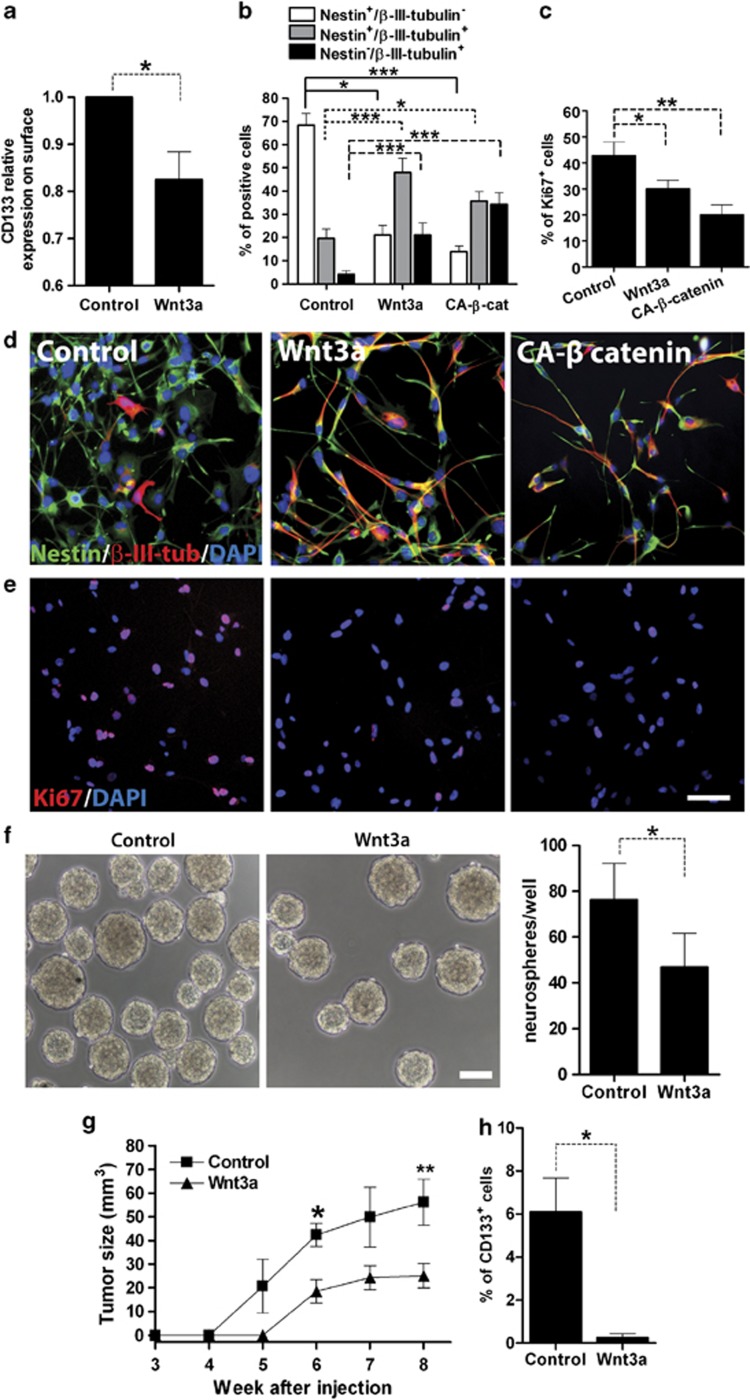

Wnt activation promotes neuronal differentiation of GBM cells

To study the effects mediated by exogenous activation of Wnt pathway in GBM cells, we first analysed cellular phenotype of primary GBM cells derived from the dissociation of 10 tumour biopsies (grade IV gliomas) taken at surgery (Supplementary Table S1), after recombinant Wnt3a treatment (30 ng/ml for 96 h). Wnt3a significantly reduced the percentage of CD133+ GBM CSCs (Figure 1a). Moreover, GBM cells treated with Wnt3a, or transfected with a constitutively active form of β-catenin (CA-β-catenin; Supplementary Figure S1A), underwent a strong neuronal differentiation and proliferation inhibition as shown by the reduction of Nestin+ and Ki67+ cells and increased percentage of neuronal-like β-III-tubulin+ cells (Figures 1b–e). A significant increase in p21cip1 was also measured, indicative of cell-cycle arrest (Supplementary Figure S1B). Induction of neuronal differentiation was confirmed at the transcriptional level by the upregulation of neuronal maturation and differentiation markers NeuroD1, Neurog1, and β-III-tubulin (Supplementary Figure S1C). To investigate whether the observed differentiation mediated by Wnt was an irreversible process, we treated cells with Wnt3a and analysed their phenotype after its withdrawal. GMB cells showed no reversion from the differentiated phenotype within 7 days after Wnt3a withdrawal (Supplementary Figure S1D). We then functionally validated the Wnt-induced differentiation by analysing the sphere forming ability of GBM cells. We measured a significant reduction in the number of neurospheres generated after Wnt3a treatment (Figure 1f). Moreover, Wnt3a in vitro treatment significantly reduced the growth of xenografts in vivo (Figure 1g). Indeed, xenografts derived from Wnt3a-treated cells contained a reduced number of CD133+ GBM CSCs (Figure 1h).

Figure 1.

Wnt3a modulates neuronal differentiation of GBM-derived cells. (a) Analysis of CD133 cell surface marker expression after Wnt3a treatment of GBM cells. Mean of five tumours±S.E.M., n=1 for each tumour. (b and c) Bar graph reporting relative quantification of immunofluorescence analysis on GBM cells treated with Wnt3a or transfected with CA-β-catenin and stained for (b) Nestin/β-III-tubulin or (c) Ki67. Mean of six tumours±S.E.M. n=3 for each tumour. (d and e) Representative images of GBM cells treated as in (b) and (c) and stained for (d) Nestin (green)/β-III-tubulin (red) or (e) Ki67 (red). Bar=100 μm. (f) Representative images showing reduction in neurosphere forming ability driven by Wnt3a treatment and relative graph. Bar=200 μm. (g) Growth kinetics of control or Wnt3a-treated GBM cells and injected subcutaneously (5 × 105 cells) into both dorsolateral flanks in NOD SCID gamma (NSG) mice. Five mice per experimental group were used. (h) Cytofluorimetric measurement of CD133+ cells derived from GBM xenografts at kill (8 weeks post injection). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001

Interestingly, the effects of Wnt were observed in cells maintained at 2% oxygen, a condition that is able to maintain an undifferentiated phenotype per se.13 In normoxia (20% oxygen), the Wnt-mediated effects were much less pronounced: we found only a small decrease in the Nestin+ GBM sub-population with a non-significant increase in β-III-tubulin+ cells (Supplementary Figures S2A–C). Moreover, the number of Ki67 and CD133 expressing cells did not change in Wnt3a-treated cells at 20% oxygen (Supplementary Figures S2D and E). These results suggested a key role of hypoxia as a modulator of Wnt responsiveness in primary GBM cells. We thus hypothesized that a hypoxic environment could enhance Wnt-dependent GBM differentiation.

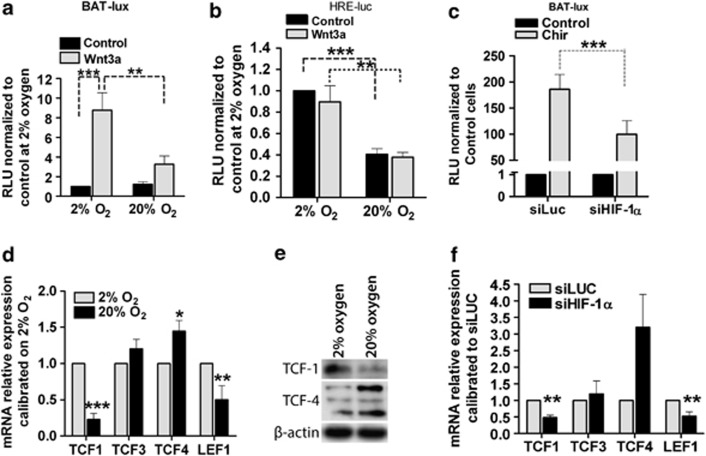

Hypoxia co-operates with Wnt in mediating GBM cells differentiation

In our previous studies, we demonstrated that microenvironmental hypoxia, through the oxygen-regulated hypoxia inducible factor (HIF)-transcription factors,14 controls GBM tumour physiology by modulating signalling pathways involved in stemness maintenance and/or differentiation.15, 16, 17 To investigate the crosstalk between hypoxia and Wnt pathways, we transfected GBM-derived cells with a TCF/β-catenin-activation (BAT-Lux) reporter plasmid, a well-established sensor of Wnt activity.18 Cells were then treated with Wnt3a ligand at different oxygen tensions. We found that hypoxia, but not 20% O2, mediated a strong Wnt3a-induced β-catenin transcriptional activation (Figure 2a). Conversely, Wnt had no effect on HIF transcriptional activity, as assayed by transfection of the HIF sensor (hypoxia response element (HRE)-LUC), in line with the idea of HIF regulating Wnt, but not vice versa (Figure 2b). To unravel the epistatic relationship between HIF-1α and β-catenin, we silenced HIF-1α with lentiviral vectors (about 78% silencing efficacy; not shown) in cells in which Wnt pathway was activated at the intracellular level by inhibiting GSK3 with the widely used inhibitor CHIR99021.19, 20 CHIR99021 treatment upregulated β-catenin transcriptional activity >150 folds in control cells. Conversely, in HIF-1α silenced cells, CHIR99021-mediated reporter induction was significantly weaker (Figure 2c). These results suggest that HIF-1α modulates β-catenin signalling by enhancing its transcriptional activity downstream of GSK3 inhibition.

Figure 2.

Hypoxia modulates Wnt activation by regulating TCFs expression. (a) Bar graph representing luciferase reporter activity of BAT-lux transfected cells treated with Wnt3a and cultured at 2% O2 or 20% O2. Mean of six tumours±S.E.M., n=2 for each tumour. (b) Bar graph representing luciferase reporter activity of HRE-luc transfected cells treated with Wnt3a and cultured at 2% O2 or 20% O2. Mean of six tumours±S.E.M., n=2 for each tumour. (c) Bar graph representing luciferase reporter activity of HIF-1α silenced and control (siLuc) cells, transfected with BAT-lux and treated with CHIR99021. Mean of three tumours±S.E.M., n=2 for each tumour. (d) Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RQ-PCR) analysis of TCF-1, -3, -4 and LEF-1 in GBM cells maintained in hypoxia or exposed to 20% O2 tension. (e) WB representing TCF-1 and TCF-4 protein level in GBM cells at 2% or 20% oxygen tension. Analysis repeated on additional three tumours. (f) RQ-PCR analysis of TCF-1, -3, -4 and LEF-1 in GBM cells silenced for HIF-1α or transduced with a control vector (siLuc). Mean of three tumours±S.E.M., n=3 for each tumour. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001

In embryonic and neural stem cells (NSCs), HIF-1α can promote canonical Wnt signalling activation by overexpressing β-catenin co-factors TCF-1 and LEF-1.12 For this reason, we measured mRNA levels of TCFs in primary GBM cells. Interestingly, we found that high oxygen levels strongly reduced TCF-1/LEF-1 expression and augmented TCF-4 (TCF7L2) transcript (Figure 2d). Western blot (WB) analysis confirmed the oxygen-mediated shift between TCF1 and TCF4 protein levels (Figure 2e). Crucially, we found a significant decrease in TCF-1 and LEF-1 mRNA expression in HIF-1α silenced cells, indicating the specific involvement of HIF-1α in the regulation of TCF-1/LEF-1 levels (Figure 2f). Taken together, these data demonstrate that hypoxia modulates Wnt pathway activation by controlling TCFs expression through HIF-1α.

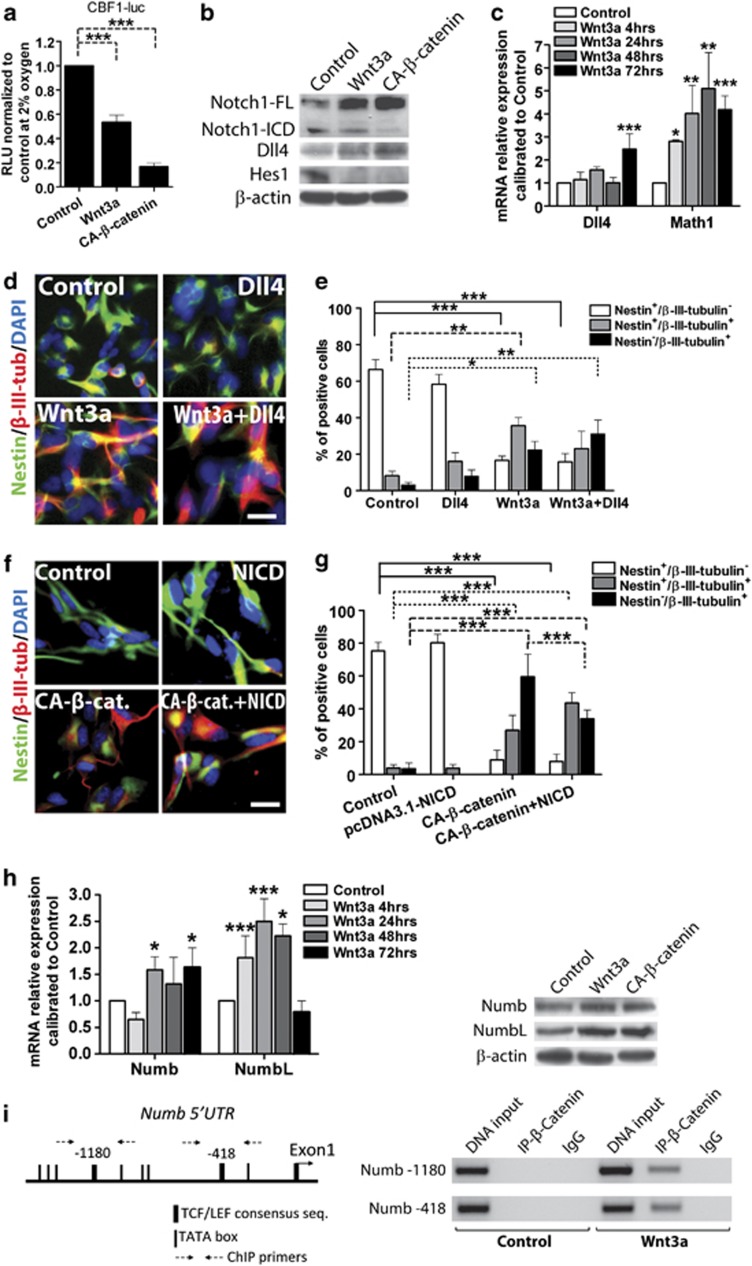

Notch signalling inhibition cooperates in Wnt-induced differentiation

Wnt and oxygen levels are essential elements of the cellular microenvironment, but the cell-to-cell contact, in a tumour mass is another fundamental feature that determines cancer cell fate. Notch signalling attracted our attention because of its dual activity as potent inhibitor of neural differentiation and regulator of GBM stem cell phenotype and aggressive behaviour.21

Blockade of Notch with the γ-secretase inhibitor DAPT induced a strong decrease in Ki67 expression and an increase in β-III-tubulin+ cells (Supplementary Figures S3A–C). Interestingly, growth arrest and neuronal differentiation mediated by DAPT were comparable to that observed in hypoxic Wnt signalling-activated cells (Supplementary Figures S3A–C, compare it to Figures 1b–e). We thus evaluated the possibility that Notch inhibition could occur downstream of Wnt activation. For this reason, we transfected GBM-derived cells with a Notch activity reporter (CBF1-luciferase) plasmid and evaluated Notch transcriptional activation after Wnt3a treatment, or CA-β-catenin transfection. Wnt activation caused a dramatic inhibition of Notch transcriptional activity (Figure 3a), accompanied by lower levels of Hes1 protein (Figure 3b), a primary target of Notch, highly expressed in GBM cells. Moreover, we found that Wnt3a-treated cells displayed increased levels of the pro-neuronal markers Dll4 and Math1 (Figures 3b and c).22

Figure 3.

Wnt pathway activation inhibits Notch signalling in GBM-derived cells. (a) CBF1-luc reporter analysis of Wnt3a-treated or CA-β-catenin-transfected cells at 2% O2. Mean of four tumours±S.E.M., n=2 for each tumour. (b) WB of protein extracts from same cells as in (a) displaying Notch pathway regulation. (c) RQ-PCR analysis reporting relative expression of Dll4 and Math1. Mean of six tumours±S.E.M., n=4 for each tumour. (d and e) Representative immunofluorescence images of GBM cells treated with Dll4, Wnt3a or both for 96 h and stained for Nestin (green)/β-III-tubulin (red) (d) and graph reporting relative quantification (e). Mean of three tumours±S.E.M., n=3 for each tumour. Bar=100 μm. (f and g) Representative immunofluorescence images of GBM cells transfected with NICD, CA-β-catenin or both, cultured for 48 h and stained for Nestin (green)/β-III-tubulin (red) (f) and bar graph reporting relative quantification (g). Mean of three tumours±S.E.M., n=3 for each tumour. Bar=100 μm. (h) RQ-PCR analysis showing mRNA levels of Numb and NumbL of Wnt3a-treated GBM cells at different time points (left). Numb and NumbL protein expression of Wnt3a-treated or CA-β-catenin-transfected GBM cells (right). Mean of six tumours±S.E.M., n=4 for each tumour. (i) ChIP analysis of Numb promoter performed on 293T and GBM cells treated with Wnt3a or not treated. The IP was performed using anti-total β-catenin antibody or an irrelevant antibody as negative control. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001

We then sought to determine if Notch activation could rescue Wnt effects in GBM cells. First, we attempted to rescue the phenotype of Wnt3a-treated cells by co-administrating the Notch ligand Dll4 and comparing their phenotype (as assayed by Nestin and β-III-tubulin expression). Wnt3a-treated cells retained a differentiated phenotype, irrespectively of Dll4 addition (Figures 3d and e). This suggested that Wnt/β-catenin signalling operated downstream of Delta-Notch binding. Interestingly, Wnt3a treatment – or CA-β-catenin expression – reduced notch intracellular domain (NICD) levels, a well-known read-out of Notch activation (Figure 3b). We thus directly tested the effect of NICD overexpression on Wnt activity by co-transfecting GBM cells with expression plasmids encoding NICD and CA-β-catenin (Supplementary Figure S4A). NICD overexpression partially inhibited Wnt-mediated neuronal differentiation, as we found a comparable decrease in the Nestin+ cells but a reduced induction of β-III-tubulin (Figures 3f and g). Thus, we concluded that Wnt opposes Notch signalling by intercepting NICD activity. But how does β-catenin activation regulate Notch? Numb and NumbL are well-known Notch inhibitors and have been recently proposed to contain β-catenin binding sites in their promoters.23 This prompted us to test whether Wnt3a treatment was able to induce Numb and NumbL transcription. As shown in Figure 3h, Wnt3a increased both Numb and NumbL expression at the transcriptional and protein levels. Moreover, chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis showed that, under Wnt3a stimulus, β-catenin directly bound to NUMB promoter, unveiling a direct β-catenin-mediated upregulation of Numb (Figure 3i).

Coherently with the stronger β-catenin activation, also Notch activity inhibition occurred mainly in hypoxic conditions (Supplementary Figure S4B). These results indicate that the Wnt/β-catenin axis has a direct effect on NUMB activation and Notch signalling inhibition, consequently promoting GBM cells differentiation.

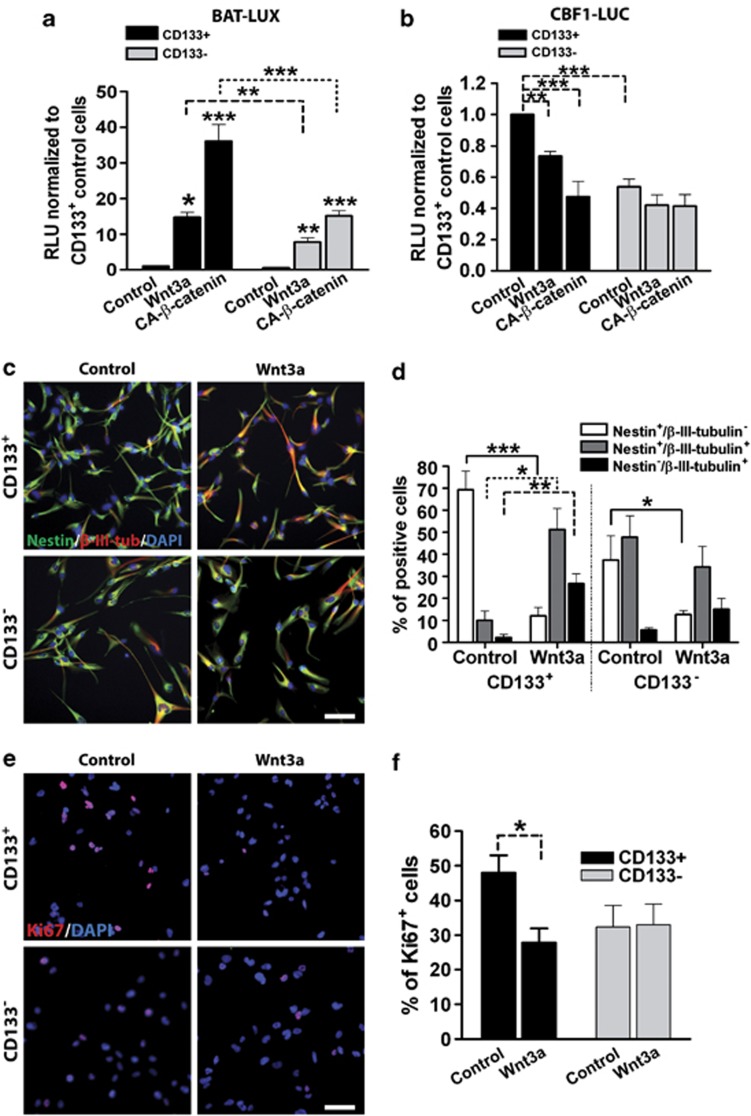

Wnt activation affects the GBM stem-like cell population

Data presented so far refer to the entire cell population derived from GBM tumour mass, raising questions on what cell population is affected by Wnt. To address this question, we sorted primary GBM cells with fluorescent activated cell sorting (FACS) by means of CD133 expression (not shown), which is the better established GBM stem-like cell marker.4 Indeed, CD133+ cells were characterized by a higher expression of markers associated with GBM stem cells such as Sox2, CD4424 and CD9025 (Supplementary Figure S5A, upper panels), comparable levels of glial acidic fibrillary protein (GFAP) and β-III-tubulin expression (Supplementary Figure S5A, lower panels), and a dramatic increase in their neurosphere forming ability, when compared with CD133− cells (Supplementary Figure S5B).

We evaluated if there were differences in the response to Wnt activation between CD133+ and CD133− cells. First, we transfected CD133+ and CD133− sorted cells with the BAT-LUX or CBF1-LUC reporter constructs. Starting from a comparable basal level of β-catenin transcriptional activity, Wnt3a administration and CA-β-catenin overexpression activated BAT-LUX reporter signal much more in the CD133+ cells (Figure 4a). Moreover, Wnt3a and CA-β-catenin inhibited Notch transcriptional activity only in CD133+ cells (Figure 4b). These data suggest that Wnt pathway activation is efficiently translated into β-catenin transcriptional activation only in GBM stem-like cells. Phenotypic analysis showed that Wnt activation promoted neuronal differentiation mainly in CD133+ cells, which showed a strong increase in the β-III-tubulin+ cell fraction (Figures 4c and d). As expected, CD133− untreated cells displayed a more differentiated phenotype relative to CD133+ cells (Figures 4c and d). In agreement with these data, also proliferation was inhibited only in CD133+ cells (Figures 4e and f).

Figure 4.

Wnt activation-mediated differentiation mainly affects CD133+ GBM-derived cells. (a and b) BAT-lux (a) and CBF1-luc (b) reporter analysis of CD133+ or CD133− sorted GBM cells treated with Wnt3a or transfected with CA-β-catenin at 2% O2. Mean of four tumours±S.E.M., n=2 for each tumour. (c and d) Representative immunofluorescence images of CD133± sorted GBM cells treated with Wnt3a for 96 h and stained for Nestin (green)/β-III-tubulin (red) (c) and relative quantification (d). Bar=100 μm. (e and f) Representative immunofluorescence images of same cells as (c) and (d) stained for Ki67 (red) (e) and relative quantification (f). Bar=100 μm. Mean of four tumours±S.E.M., n=3 for each tumour. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001

The most pronounced Wnt3a-mediated differentiation effect (and proliferation inhibition) was observed in CD133+ cells under hypoxia. Conversely, CD133− cells exposed to 20% oxygen were almost insensitive to Wnt3a treatment (Supplementary Figures S6A and B).

Human GBM cells are subjected to Wnt signalling activation when transplanted into zebrafish larvae

We next sought to further validate the role of Wnt as promoter of GBM cell differentiation. Previous reports showed that growth of human tumours could be recapitulated in non-murine models such as the zebrafish.26, 27, 28 Indeed, this system presented several benefits in our context: first, it allows live monitoring of GBM cell fate after injection; second, developing fish brain expresses endogenous Wnt molecules,29 whose activity can be visualized in vivo by using the Wnt reporter zebrafish strain Tg(7xTCF-Xla.Siam:GFP)ia4;30 third, zebrafish embryos/larvae develop physiologically at low oxygen tension;31 fourth, the unlimited amount of recipient animals allows to carry out extended manipulations in vivo before the emergence of cell culture senescence; fifth, the availability of transgenic strains with an inducible expression of the Wnt antagonist DKK allows to monitor the effect of endogenous Wnt modulation on injected GBM cells.32

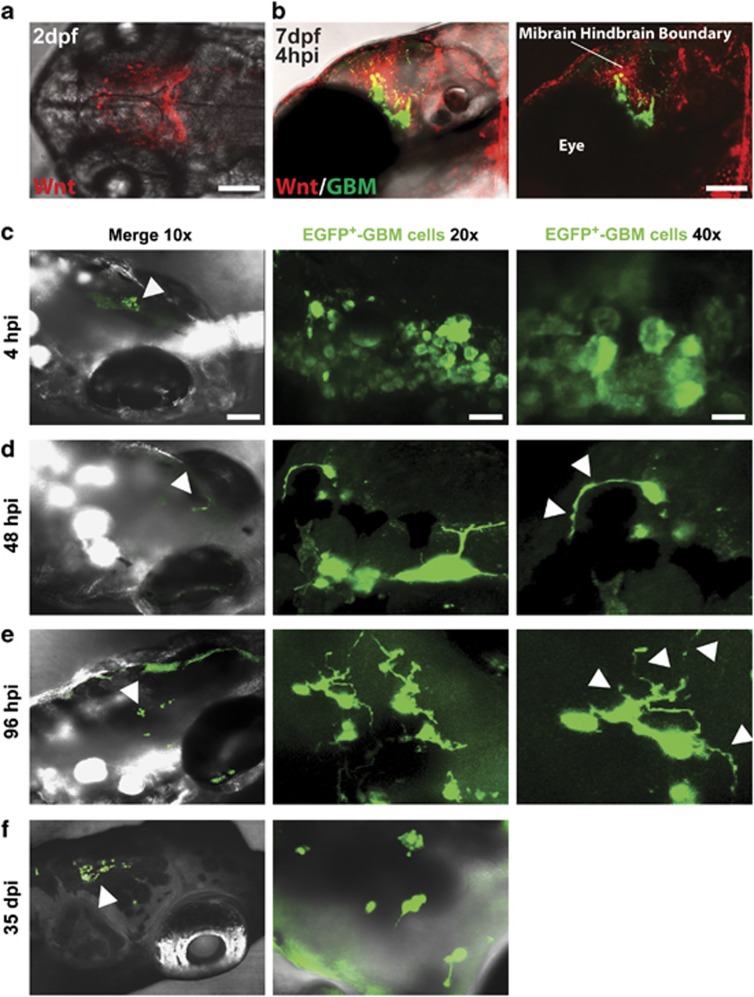

In light of the above considerations, we evaluated whether GBM cell phenotype was affected by the zebrafish brain microenvironment.29 By using the Wnt-reporter Tg(7xTCF-Xla.Siam:nlsmCherry)ia4 strain (Figure 5a), we targeted primary human GBM cell injection into a Wnt-rich brain site located in the midbrain-hindbrain boundary, at 7 dpf (Figure 5b). Human GBM grafted cells were then tracked in vivo until 35 days post injection (dpi). Live confocal imaging performed 4 hours post injection (hpi), showed that GBM cells were still characterized by a small, round morphology, typical of undifferentiated brain tumour cells, and were localized at the site of injection (Figure 5c). Intriguingly, starting from 48 hpi, GBM cells increased in size and exhibited cellular projections first, and then axonal and neurite outgrowth (Figures 5d–f).

Figure 5.

Xeno-transplanted GBM cells acquire a differentiated morphology. (a) Representative images showing mCherry expressing Wnt reporter zebrafish cells (red) in the midbrain-hindbrain boundary at 2 dpf. (b) Xeno-transplanted primary GBM-derived cells (enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) expressing; 4 hpi) in Wnt activated midbrain hindbrain boundary of 7 dpf Wnt reporter Zebrafish larvae. Bar=100 μm. (c–f) Representative images of grafted EGFP expressing GBM cells in live larvae monitored at 4 (c), 48 hpi (d), 96 hpi (e) and 35dpi (f). White arrows indicate the site where transplanted cells reside with × 10 magnification and their cellular projections with × 40 magnification. Magnification × 10, bar=100 μm; magnification × 20 bar=40 μm; magnification × 40, bar=10 μm

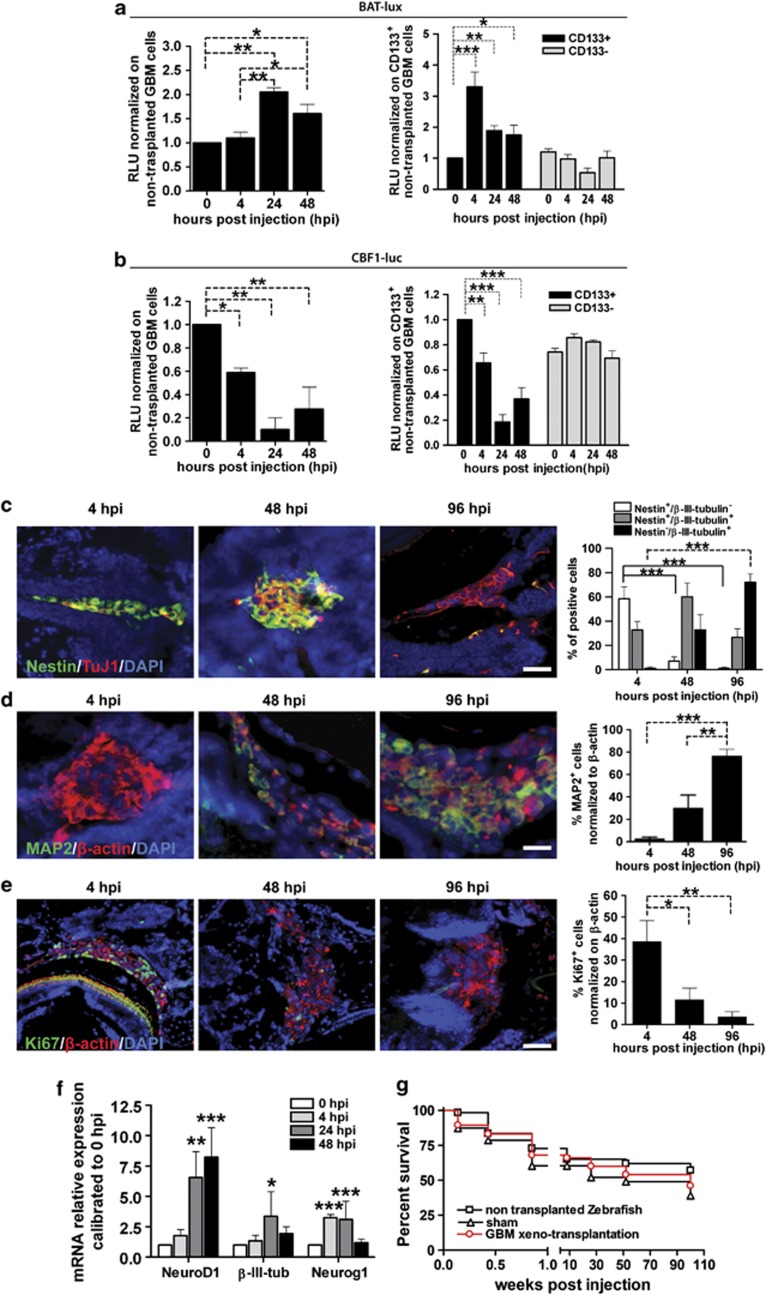

We then assessed the direct involvement of Wnt pathway activation in GBM transplanted cells. First, we found a significant increase in total human β-catenin expression in protein extracts obtained from grafted zebrafish brains, starting from 48 hpi (Supplementary Figures S7A and B). Second, by using the BAT-LUX reporter plasmid, we registered an upregulated β-catenin transcriptional activity in transplanted primary GBM cells at 24 hpi (Figure 6a, left). Intriguingly, this occurred only in CD133+ cells (Figure 6a, right), as previously shown in vitro. Moreover, by transfecting tumour cells with CBF1-luc reporter plasmid, we confirmed that zebrafish-mediated β-catenin activation is accompanied by a concomitant decrease in Notch activity (Figure 6b).

Figure 6.

Xeno-transplanted GBM-derived cells undergo neuronal differentiation and cell-cycle arrest. (a and b) BAT-lux (a) and CBF1-luc (b) reporter assays of human GBM grafted cells (left: injection of entire GBM cell population; right: injection of distinct CD133+ or CD133− sorted GBM cell populations). Values are expressed in RLU calibrated on non-transplanted GBM cells (0 hpi). Three different GBMs were analysed, n=4 for each tumour. (c–e) Representative immunofluorescence images of paraffin-embedded tissue sections of xeno-transplanted zebrafish larvae at 4, 48 and 96 hpi stained for (c) Nestin (green)/β-III-tubulin (red), (d) MAP2 (green)/β-actin (red), (e) Ki67 (green)/β-actin (red) (left panels) and bar graphs reporting relative quantifications (right panels). Bar=40 μm. For all graphs, mean of 10 tumours±S.E.M., n=10 for each tumour. (f) RQ-PCR analyses of NeuroD1, β-III-tubulin and Neurog1 expression normalized to Gusb and then calibrated to control cells (0 hpi) of human GBM cells grafted into zebrafish nervous system, mean±S.E.M., comparing three different GBM, n=4 for each tumour. (g) Survival graph of post-transplanted zebrafish compared with sham and non-injected larvae bred in the same conditions. Mean of 10 tumours injected±S.E.M., n=50 for each experimental group

We characterized the differentiation of injected primary GBM cell in paraffin-embedded zebrafish larvae. Immunofluorescence analysis revealed a progressive loss of Nestin and increase in β-III-tubulin expression, indicating that the zebrafish brain induced a phenotypic shift of transplanted GBM cells towards neuronal fate, as shown for Wnt3a treatment in vitro (Figure 6c). In addition, expression of microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2), a neuron-specific cytoskeletal protein expressed in post-mitotic differentiated neurons,33 progressively increased, confirming the acquisition of a mature neuronal phenotype (Figure 6d). Analysis of proliferation, through Ki67 staining, showed that injected tumour cells progressively underwent mitotic arrest (Figure 6e). We also found that mRNA levels of genes related to neuronal differentiation (NeuroD1, β-III-tubulin, and Neurog1) were upregulated in xeno-transplanted GBM cells, confirming the pro-neuronal phenotypic shift (Figure 6f) as shown in GBM cells after Wnt3a treatment (Supplementary Figure 1C). Differentiation of cancer cells should reflect in less aggressive tumours and to increase survival of animal models. We thus evaluated fish survival for up to 2 years, comparing GBM-injected zebrafish with sham-injected or non-injected wild-type animals. Human GBM cell injection did not affect survival (Figure 6g). These results suggest that Wnt ligand-enriched zebrafish brain is able to phenotypically reprogram transplanted GBM cells in vivo, directing them towards neuronal differentiation and mitotic arrest.

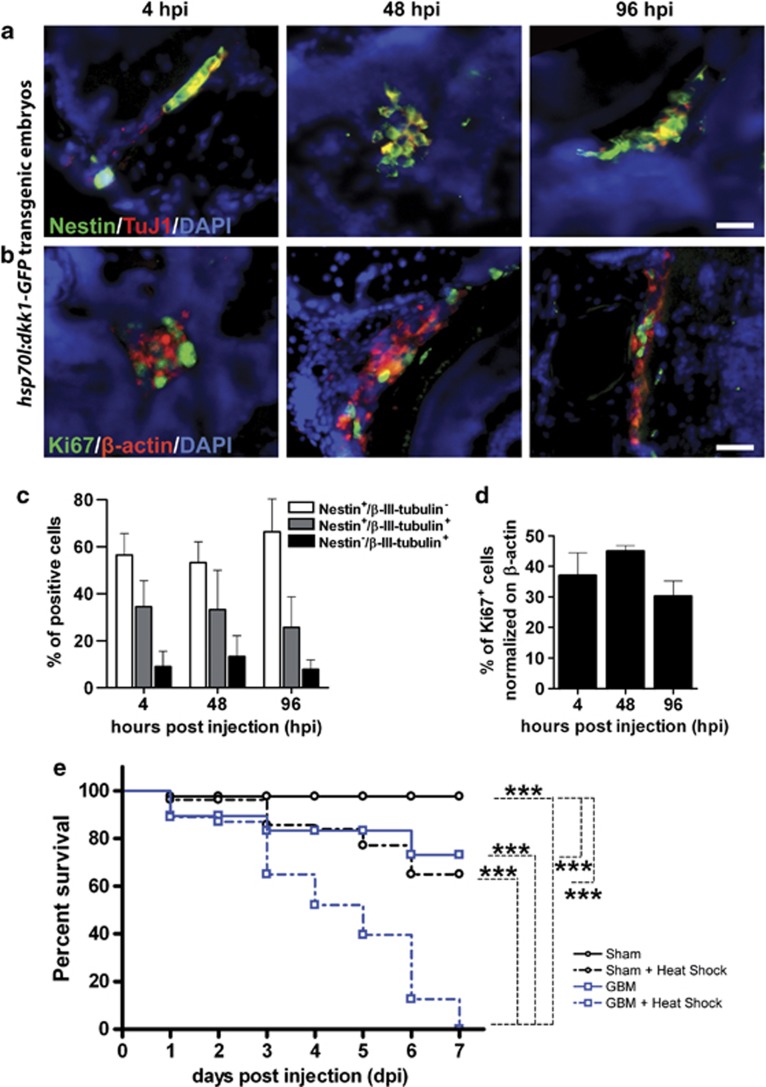

To functionally confirm in vivo the role of Wnt pathway activation in differentiating human primary GBM-derived cells, we transplanted cells into the zebrafish transgenic strain Tg(hsp70l:dkk1-GFP), in which Wnt signalling can be conditionally repressed by the overexpression of DKK1 (Supplementary Figure S8A).32 Strikingly, GBM cells, grafted into Tg(hsp70l:dkk1-GFP) larvae, did not differentiate and maintained their proliferation rate as shown by the expression of Nestin, β-III-tubulin and Ki67 markers (Figures 7a–d; compare it with wild-type embryos in Figures 6c and d). This higher proliferation also correlated with a higher mortality of injected larvae, when compared with sham-injected fishes (Figure 7e). We obtained similar results in xeno-transplanted larvae treated with IWR, a compound known to inhibit Wnt pathway activation in vivo34 and able to downregulate the expression of Wnt-controlled genes, such as neurod (Supplementary Figures S8B and S9A–D).

Figure 7.

Neuronal differentiation of grafted GBM cells is dependent on zebrafish Wnt ligands. (a and b) hsp70l:dkk1-GFP xeno-transplanted larvae at 4, 48 and 96 hpi stained for Nestin (green)/β-III-tubulin (red) (a) and Ki67 (green)/β-actin (red) (b). Bar=40 μm. (c and d) Bar graphs showing relative quantification of images described in (a) and (b). Mean of six tumours injected±S.E.M., n=50 for each experimental group. (e) Survival graph of post-transplanted hsp70l:dkk1-GFP zebrafish compared with sham±heat shock, bred in the same conditions. Mean of six tumours injected±S.E.M., n=50 for each experimental group. ***P<0.001

These results confirm our in vitro observations and indicate that endogenous Wnt signals in the vertebrate brain can restrain GBM aggressiveness by fostering its differentiation.

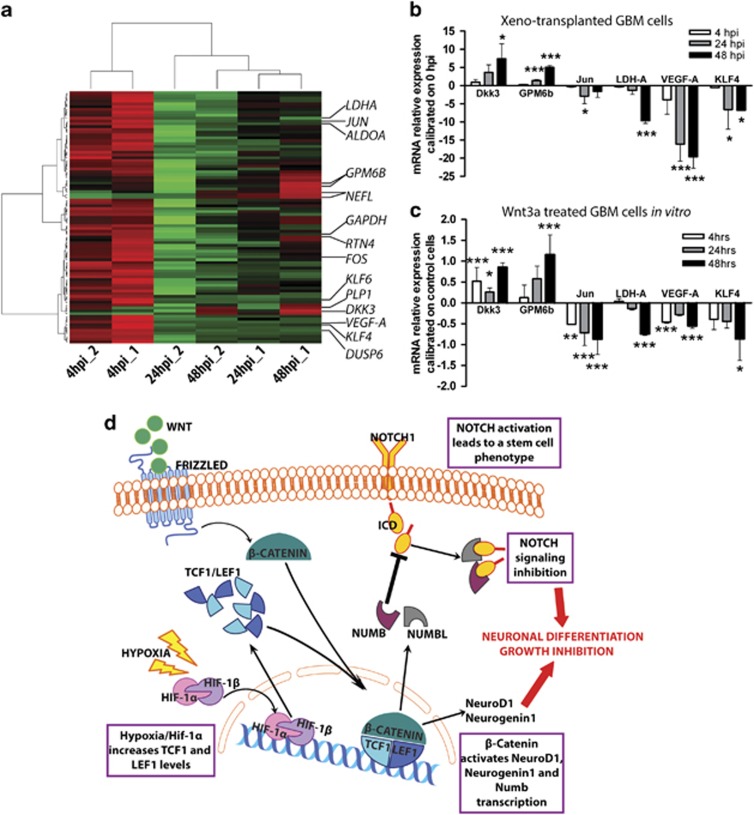

Gene expression profile of injected GBM cells demonstrates induction of a less oncogenic phenotype

To obtain further evidence on the involvement of Wnt-mediated neuronal differentiation of GBM cells and to better characterize the phenotype of transplanted cells, we performed whole genome profiling (GeneChip Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0) on grafted GBM cells. We analysed gene expression profile (GEP) of human GBM cells derived from two different patients, each injected in 300 larvae. After 4, 24, and 48 hpi, we extracted total RNA from larval brain. Eighty-nine probe sets were retrieved from the intersection of the differentially expressed probe sets along the three time points obtained by the two independent experiments (Figure 8a; Supplementary Table S2). Specifically, we found that transcription of KLF6 and KLF4, involved in stemness and pluripotency maintenance,35, 36 was decreased after transplantation (Figures 8a and b; Supplementary Table S2). Moreover, GEP data showed that injected GBM cells underwent a dramatic decrease in c-JUN, VEGF, LDHA, GAPDH, and ALDOA, indicative of a robust decrease in proliferation, angiogenesis, and glycolysis related genes (Figures 8a and b; Supplementary Table S2; Supplementary Figure S10). Conversely, we observed overexpression of the neuronal developmental genes GMP6B, CRYAB, and NEFL (Figures 8a and b), in line with the Wnt-dependent increase in Neurog1 and NeuroD1 observed in vitro and in vivo (Supplementary Figure 1c; Figure 6f). Finally, as a confirm, GEP validation comparison showed that the same set of genes was activated in zebrafish-transplanted and in vitro Wnt3a-treated GBM cells (Figures 8b and c). Indeed, this provides a robust proof-of-principle validation on the use of zebrafish xenografts as in vivo surrogate or Wnt-regulated in vitro differentiation.

Figure 8.

Gene expression profile of xeno-transplanted GBM cells and validation of data. (a) Heatmap resulting from microarray analysis of two independent experiments of human GBM cells grafted into zebrafish nervous system at 4, 24 and 48 hpi. (b and c) RQ-PCR analyses of Dkk3, GPM6b, Jun, LDH-A, VEGF-A and KLF4 expression of xeno-transplanted GBM cells normalized to Gusb, then calibrated to control cells (0 hpi) (c) and Wnt3a in vitro treated GBM cells (c). Mean±S.E.M. comparing two different GBM, n=4 for each tumour. (d) Cartoon describing the HIF-1α, β-catenin and Notch reciprocal regulations proposed in this study. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001

Discussion

In the present study, we describe a Wnt/β-catenin-mediated phenotypic reprogramming of patient-derived GBM cells towards a neuronal-like fate. Moreover, we define the fundamental role of hypoxia in enhancing the Wnt-mediated neuronal differentiation and Notch inhibition. In particular, we demonstrate a Wnt-regulated suppression of Notch activity in the hypoxic microenvironment of GBM tumours and the reduction of their stem-like cell sub-population (CD133+). Several lines of evidence support these conclusions:

GBM cells treated with Wnt3a or transfected with CA-β-catenin undergo a strong increase in β-III-tubulin+ neuronal-like cells expressing high levels of NeuroD1 and Neurog1 (Figures 1b–e; Supplementary Figure 1c);

hypoxia promotes Wnt pathway activation through HIF-1α-mediated TCFs modulation (Figures 2d–f);

Wnt activation increases Numb and NumbL expression whose function is to inhibit NICD activation (Figure 3);

Wnt-mediated differentiation and Notch inhibition occurred mainly in the CD133+ stem-like GBM cell population (Figure 4). Although CD133 has been shown not to be unique in defining GBM or NSCs,37 it might be used in combination with other markers to enrich cancer cell populations for CSCs.38, 39 Moreover, our data support the idea that the CD133+ GBM sub-population is enriched in cells with self-renewing capability and stem-like features (Supplementary Figure S5).

The role of Wnt activation in regulating brain tumour phenotype is controversial. Recent studies showed that the use of GSK3 inhibitors, known to increase β-catenin levels, potently and specifically blocked glioma cell migration,40 reduced tumorigenicity,41 and decreased stem cell markers expression, such as Nestin and Sox2.42 However, many authors reported that overexpression of Wnt in glioma tumours promoted CSC self-renewal and proliferation.43, 44 Indeed, many pro-oncogenes promote GBM growth and stemness by activating Wnt pathway co-factors, in particular TCF-4.45, 46, 47 Consistent with these data, we found that TCF-4 expression is higher in GBM cells maintained at 20% oxygen (Figures 2d and e). That said, our data are in agreement with the function of Wnts having a more prevalent role as pro-differentiation factors, at least under conditions that recapitulate the physiological hypoxic microenvironment of the brain.48 Tissue oxygenation is a fundamental parameter able to modulate the behaviour of GBM cells and the activation of several cellular pathways.49 Mazumdar et al.12 recently reported that HIF-1α enhances the expression of the β-catenin co-factors TCF-1 and LEF-1 in embryonic and NSCs, thus promoting β-catenin-dependent Wnt signalling activation. Our data confirm that HIF-1α mediates TCF-1 and LEF-1 expression in primary GBM-derived cells maintained under hypoxia (2% oxygen) and that this leads to higher β-catenin transcriptional activity after exogenous Wnt activation (Figure 2).

Interestingly, we found that the effects of Notch pathway inhibition on GBM cells are comparable to that observed in Wnt pathway-activated hypoxic cells (Supplementary Figures S3A–C).21 Mechanistically, this is mediated by a direct interaction between β-catenin and the promoter of NUMB in Wnt3a-stimulated cells (Figure 3i), as previously suggested by Katoh and Katoh23 based on bioinformatics. This result is consistent with the Wnt-dependent suppression of NICD activity observed under hypoxic conditions.

To confirm in vivo these results, we first validated and then exploited the use of the small eleost Danio Rerio (zebrafish) as paradigm of a natural brain parenchyma, particularly enriched in Wnt molecules. The use of zebrafish as cancer model system is not new: for example, Hendrix's group previously demonstrated that zebrafish microenvironment at 3 dpf suppressed the tumorigenic phenotype of xeno-transplanted malignant melanoma cells.27, 28 However, the possibility to employ orthotopic injections in transgenic fish brains for studying GBM is unique of the present study. Interestingly, our in vivo data confirm that endogenous Wnt signals operating in the developing zebrafish brain are able to reprogram injected human GBM-derived cells towards a quiescent neuronal phenotype. Injected cells show concerted changes in the expression of stemness, proliferation, and neuronal markers, as confirmed also by GEP analyses. Moreover, these effects are inhibited in the hsp70l:dkk1-GFP transgenic larvae where Wnt pathway is conditionally ablated.

In conclusion, we describe the convergence of HIF, Wnt and Notch pathways in the regulation of primary GBM-derived cell differentiation (Figure 8d). Our data show that hypoxia has a crucial role in preserving Wnt-ligand intracellular effects by controlling the expression of β-catenin co-factors TCF-1 and LEF-1. β-Catenin activation increases levels of Notch inhibitors Numb and NumbL leading to the induction of pro-neuronal gene expression. In addition, Wnt activation promotes a dramatic differentiation of GBM cancer stem-like cells towards a neuronal, less aggressive phenotype.

Materials and Methods

Isolation and oxygen controlled expansion of GBM cells

Written informed consent for the donation of adult tumour brain tissues was obtained from patients under the auspices of the protocol for the acquisition of human brain tissues of the Ethical Committee Board of the University of Padova and Padova Academic Hospital. All tissues were acquired following the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Patients from which we derived GBM primary cultures are listed in Supplementary Table 1. GBM precursors were derived and maintained as previously described15 in fibronectin-coated flasks. Where indicated, GBM-derived cells were supplemented with soluble Wnt3a (30 ng/ml, Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) for 4, 24, 48 or 96 h or transfected by using a protocol for transient transfection of adherent cells using Effectene Reagent (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) with a plasmid bearing a constitutively active form of β-catenin (CA-β-catenin)50 or expressing the NICD.51 For the neurosphere forming assay, GBM cells were plated in non-coated flasks at a density of 1000 cells/P12 well. Neurosphere number was measured after 3 weeks of culture.

Flow cytofluorimetric analyses and CD133 cell sorting

Cells (2 × 106 cells/ml) were incubated with anti-human β-III-tubulin, CD44, CD90 (Fitc; BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), CD133 (clone AC133/2-PE, MiltenyiBiotec, BergischGladbach, Germany), Sox2 (PerCP5.5; BD Biosciences) and GFAP (AlexaFluor647; BD Biosciences) as previously described.15, 16, 52 Viability was assessed by adding 7-amino-actinomycin-D (7-AAD, 50 ng/ml; BD Biosciences) before analysis. Cells were analysed on a BD FacsAria III (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) FACS. Relative percentages of different sub-populations were calculated based on live gated cells (as indicated by physical parameters, side scatter and forward scatter). Unlabelled cells and cells incubated with appropriate isotype control antibodies were first acquired to ensure labelling specificity. In cell sorting experiments, GBM cells were analysed and then sorted on the basis of CD133 expression. A CD133 versus Side Scatter dot plot revealed the populations of interest that were sorted: CD133+ and CD133− cell fractions were selected by setting appropriate sorting gates.

Tumorigenicity assay

NOD SCID gamma (NSG) mice were purchased from Charles River (Wilmington, MA, USA). Procedures involving animals and their care conformed with institutional guidelines that comply with national and international laws and policies (EEC Council Directive 86/609, OJ L 358, 12 December 1987). Eight-week-old male mice were used for experiments. For tumour establishment, GBM cells were in vitro treated with Wnt3a (30 ng/ml for 5 days) and then injected subcutaneously (5 × 105 cells) in a 200-μl total volume into both dorsolateral flanks. Cells were injected in combination with additional 200 μl of Matrigel (Becton Dickinson). The resulting tumours were inspected weekly and measured by calliper; tumour volume was calculated with the following formula: tumour volume (mm3)=Lxl2 × 0.5, where L is the longest diameter, l is the shortest diameter and 0.5 is a constant to calculate the volume of an ellipsoid. After tumour formation, animals were killed, tumour mass was excised and dissociated to single-cell suspension for cytofluorimetric analysis.

ChIP assay

We performed the ChIP assay on 293T and GBM cells treated with 30 ng/ml of soluble Wnt3a for 48 h or maintained in culture medium as control. Collected cells were sonicated 30 s for eight times in a water bath sonicator, and immunoprecipitation was performed using total β-catenin antibody (rabbit, 1:5000; Abcam, Cambridge, UK). Purification of genomic DNA (ChIP samples+input) was performed by phenol/chloroform extraction, and we detected specific NUMB promoter sequences from No Ab (negative control), immunoprecipitated (samples) and input (positive control) DNAs by PCR, using 2 μl of each DNA sample.

Zebrafish handling for xeno-transplantation

Zebrafish handling and treatment were approved by the UniPD Ethical Committee on Animal Experimentation (CEASA – Project #62/2009). GBM-derived cancer cells were injected into the brain of 7 dpf wild-type or transgenic zebrafish larvae. During injection, zebrafish were anaesthetized with Tricaine (0.5 mM 3-aminobenzoic acid ethyl ester; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and then placed in a mini-plate with multiple ramps. Zebrafish larvae were placed on their sides in 3% methyl-cellulose. In some experiments, we transplanted GBM cells in hsp70l:dkk1-GFP transgenic zebrafish larvae (gift from Dr. G. Weidinger). Heat shocks were performed twice daily by transferring fish from 34 to 40 °C for 1 h.32 Wnt pathway activation was evaluated in vivo by using the Tg(7xTCF-Xla.Siam:GFP)ia4 reporter zebrafish line.30

Labelled cells were loaded into a pulled glass micropipette needle attached to an air-driven micro-injector. The tip of the needle was inserted into the zebrafish brain peri-ventricular zone, and intact cells were delivered in a double injection. We optimized the number of cells injected in a range between 100 and 150 cells/shot which we confirmed by dispensing cells onto a microscope slide and visually counting them. The volume of material injected was ∼20–50 nl. At different time points, zebrafish embryos were fixed using 4% formaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 4 °C overnight, washed with PBS and then transferred to 70% ethanol for subsequent paraffin embedding and immunofluorescence analysis, dehydrated gradually into 100% methanol for in situ hybridization or dissolved in TRIZOL Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for RNA extraction.

Luciferase reporter assays on xeno-transplanted GBM cells

GBM cells were transfected with BAT-luciferase reporter construct (BAT-Lux), Notch-luciferase reporter plasmid (CBF1-LUC) and hypoxia-luciferase reporter plasmid (HRE-Luc). Transfection with a Renilla luciferase vector was used to normalize luciferase detection (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Twelve hours after transfection, total medium change was done, and cells were collected for zebrafish injection. To control transfection efficacy, control cells were re-suspended in passive lysis buffer (PLB, Promega) and luciferase activity was analysed. Zebrafish xeno-transplanted larvae and GBM cells were processed for analysis of luciferase activity as recommended (Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System; Promega) using a plate-reading luminometer (Victor; Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA). Values, expressed in relative light units (RLUs), were normalized to the values obtained from non-injected GBM cells.

Gene expression profiling of xeno-transplanted cells

For microarray experiments, in vitro transcription, hybridization and biotin labelling of RNA from zebrafish larvae brains were performed according to Affymetrix 3'IVT Express protocol, before and at several time points after transplantation with GBM cells. GeneChip Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA) was used.

Microarray data (CEL files) were generated using default Affymetrix microarray analysis parameters (Command Console suite software, Affymetrix). CEL files were normalized using the robust multiarray averaging expression measure of Affy-R package (http://www.bioconductor.org). Probe sets with Present or Marginal detection calls in the zebrafish-only array, generated by the Affymetrix Microarray Suite version 5 (MAS5, Affymetrix) algorithm, were filtered out in the analysis of the arrays after transplantation.53 CEL files can be found at the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) repository (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/; Series Accession Number GSE25012), and are accessible without restrictions. Filtering on variance (quantile 0.995) was applied to identify genes that were differently expressed along the three time points (4, 24 and 48 hpi) in two independent experiments.

A heat map was generated using R software (http://www.R-project.org) using Euclidean distance as a distance measure between genes.

Expression data have been deposited into the GEO database under Series Accession Number GSE25012 and are accessible without restrictions.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Gilbert Weidinger, Biotechnology Center, TU, Dresden, for kindly providing hsp70l:dkk1-GFP transgenic zebrafish larvae and Professor Herman Spaink (University of Leiden) for donating albino fish lines. We are grateful to Dr Giovanni Esposito (Istituto Oncologico Veneto – IRRCS, Padova) for histological support and to Dr Giorgia Nardo and Dr Sonia Minuzzo (Istituto Oncologico Veneto – IRRCS, Padova) for help in mice handling. This work was supported by Fondazione Città della Speranza and by funds from: the Italian Association for the Fight against Neuroblastoma (Pensiero Project) to FP; the Young Investigators Grant of the University of Padova to LP; the Italian Association for Cancer Research (AIRC; Inter-regional paediatric project grant) and the Ministry of Education, University and Research (FIRB project #RBAP11TF7Z_004) to GB; the UniPD Project Grant CPDA089044 to NT; the EU grant ZF-HEALTH CT-2010-242048, the AIRC and CARIPARO Project to FA. ER is supported by a fellowship from AIRC.

Glossary

- ChIP

chromatin immunoprecipitation

- CSCs

cancer stem cells

- Dpf

Days post fertilization

- Dpi

Days post injection

- EGFP

enhanced green fluorescent protein

- FACS

fluorescent activated cell sorting

- GBM

glioblastoma multiforme

- GEO

Gene Expression Omnibus

- GEP

gene expression profile

- GFAP

glial acidic fibrillary protein

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- HIF

hypoxia inducible factor

- Hpi

hours post injection

- HRE

hypoxia response element

- MAP2

microtubule-associated protein 2

- NICD

notch intracellular domain

- NSCs

neural stem cells

- NSG

NOD SCID gamma

- PLB

passive lysis buffer

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- RLU

relative light unit

- RQ-PCR

real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- S.E.M.

standard error of the mean

- WB

western blot

- 7-AAD

7-amino-actinomycin-D

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on Cell Death and Disease website (http://www.nature.com/cddis)

Edited by A Verkhratsky

Supplementary Material

References

- Rong Y, Durden DL, Van Meir EG, Brat DJ. ‘Pseudopalisading' necrosis in glioblastoma: a familiar morphologic feature that links vascular pathology, hypoxia, and angiogenesis. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2006;65:529–539. doi: 10.1097/00005072-200606000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmati HD, Nakano I, Lazareff JA, Masterman-Smith M, Geschwind DH, Bronner-Fraser M, et al. Cancerous stem cells can arise from pediatric brain tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:15178–15183. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2036535100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ignatova TN, Kukekov VG, Laywell ED, Suslov ON, Vrionis FD, Steindler DA. Human cortical glial tumors contain neural stem-like cells expressing astroglial and neuronal markers in vitro. Glia. 2002;39:193–206. doi: 10.1002/glia.10094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh SK, Clarke ID, Terasaki M, Bonn VE, Hawkins C, Squire J, et al. Identification of a cancer stem cell in human brain tumors. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5821–5828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visvader JE. Cells of origin in cancer. Nature. 2011;469:314–322. doi: 10.1038/nature09781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Caro M, Sanchez-Garcia I. Killing time for cancer stem cells (CSC): discovery and development of selective CSC inhibitors. Curr Med Chem. 2006;13:1719–1725. doi: 10.2174/092986706777452533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee B, McEllin B, Camacho CV, Tomimatsu N, Sirasanagandala S, Nannepaga S, et al. EGFRvIII and DNA double-strand break repair: a molecular mechanism for radioresistance in glioblastoma. Cancer Res. 2009;69:4252–4259. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichert S, Rodel C, Mirsch J, Harter PN, Tomicic MT, Mittelbronn M, et al. Survivin inhibition and DNA double-strand break repair: a molecular mechanism to overcome radioresistance in glioblastoma. Radiother Oncol. 2011;101:51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2011.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato A, Sunayama J, Matsuda K, Seino S, Suzuki K, Watanabe E, et al. MEK-ERK signaling dictates DNA-repair gene MGMT expression and temozolomide resistance of stem-like glioblastoma cells via the MDM2-p53 axis. Stem Cells. 2011;29:1942–1951. doi: 10.1002/stem.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwabara T, Hsieh J, Muotri A, Yeo G, Warashina M, Lie DC, et al. Wnt-mediated activation of NeuroD1 and retro-elements during adult neurogenesis. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:1097–1105. doi: 10.1038/nn.2360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukekov VG, Laywell ED, Suslov O, Davies K, Scheffler B, Thomas LB, et al. Multipotent stem/progenitor cells with similar properties arise from two neurogenic regions of adult human brain. Exp Neurol. 1999;156:333–344. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazumdar J, O'Brien WT, Johnson RS, LaManna JC, Chavez JC, Klein PS, et al. O2 regulates stem cells through Wnt/beta-catenin signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:1007–1013. doi: 10.1038/ncb2102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pistollato F, Chen HL, Schwartz PH, Basso G, Panchision DM. Oxygen tension controls the expansion of human CNS precursors and the generation of astrocytes and oligodendrocytes. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2007;35:424–435. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang GL, Semenza GL. Purification and characterization of hypoxia-inducible factor 1. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:1230–1237. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.3.1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pistollato F, Abbadi S, Rampazzo E, Persano L, Della Puppa A, Frasson C, et al. Intratumoral hypoxic gradient drives stem cells distribution and MGMT expression in glioblastoma. Stem Cells. 2010;28:851–862. doi: 10.1002/stem.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pistollato F, Chen HL, Rood BR, Zhang HZ, D'Avella D, Denaro L, et al. Hypoxia and HIF1alpha repress the differentiative effects of BMPs in high-grade glioma. Stem Cells. 2009;27:7–17. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pistollato F, Rampazzo E, Abbadi S, Della Puppa A, Scienza R, D'Avella D, et al. Molecular mechanisms of HIF-1alpha modulation induced by oxygen tension and BMP2 in glioblastoma derived cells. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e6206. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maretto S, Cordenonsi M, Dupont S, Braghetta P, Broccoli V, Hassan AB, et al. Mapping Wnt/beta-catenin signaling during mouse development and in colorectal tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:3299–3304. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0434590100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ring DB, Johnson KW, Henriksen EJ, Nuss JM, Goff D, Kinnick TR, et al. Selective glycogen synthase kinase 3 inhibitors potentiate insulin activation of glucose transport and utilization in vitro and in vivo. Diabetes. 2003;52:588–595. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.3.588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wray J, Kalkan T, Gomez-Lopez S, Eckardt D, Cook A, Kemler R, et al. Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3 alleviates Tcf3 repression of the pluripotency network and increases embryonic stem cell resistance to differentiation. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:838–845. doi: 10.1038/ncb2267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan X, Khaki L, Zhu TS, Soules ME, Talsma CE, Gul N, et al. NOTCH pathway blockade depletes CD133-positive glioblastoma cells and inhibits growth of tumor neurospheres and xenografts. Stem Cells. 2010;28:5–16. doi: 10.1002/stem.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu F, Hata R, Ma YJ, Tanaka J, Mitsuda N, Kumon Y, et al. Suppression of Stat3 promotes neurogenesis in cultured neural stem cells. J Neurosci Res. 2005;81:163–171. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh M, Katoh M. NUMB is a break of WNT-Notch signaling cycle. Int J Mol Med. 2006;18:517–521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Nguyen DH, Dong Q, Shitaku P, Chung K, Liu OY, et al. Molecular properties of CD133+ glioblastoma stem cells derived from treatment-refractory recurrent brain tumors. J Neurooncol. 2009;94:1–19. doi: 10.1007/s11060-009-9919-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J, Liu Y, Zhu T, Zhu J, Dimeco F, Vescovi AL, et al. CD90 is identified as a candidate marker for cancer stem cells in primary high-grade gliomas using tissue microarrays. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2012;11:M111.010744. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.010744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haldi M, Ton C, Seng WL, McGrath P. Human melanoma cells transplanted into zebrafish proliferate, migrate, produce melanin, form masses and stimulate angiogenesis in zebrafish. Angiogenesis. 2006;9:139–151. doi: 10.1007/s10456-006-9040-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee LM, Seftor EA, Bonde G, Cornell RA, Hendrix MJ. The fate of human malignant melanoma cells transplanted into zebrafish embryos: assessment of migration and cell division in the absence of tumor formation. Dev Dyn. 2005;233:1560–1570. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topczewska JM, Postovit LM, Margaryan NV, Sam A, Hess AR, Wheaton WW, et al. Embryonic and tumorigenic pathways converge via Nodal signaling: role in melanoma aggressiveness. Nat Med. 2006;12:925–932. doi: 10.1038/nm1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements WK, Ong KG, Traver D. Zebrafish wnt3 is expressed in developing neural tissue. Dev Dyn. 2009;238:1788–1795. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moro E, Ozhan-Kizil G, Mongera A, Beis D, Wierzbicki C, Young RM, et al. In vivo Wnt signaling tracing through a transgenic biosensor fish reveals novel activity domains. Dev Biol. 2012;366:327–340. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranenbarg S. Wageningen University Press: Wageningen, The Netherlands; 2002. Oxygen Diffusion in Fish Embryos. [Google Scholar]

- Stoick-Cooper CL, Weidinger G, Riehle KJ, Hubbert C, Major MB, Fausto N, et al. Distinct Wnt signaling pathways have opposing roles in appendage regeneration. Development. 2007;134:479–489. doi: 10.1242/dev.001123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez C, Diaz-Nido J, Avila J. Phosphorylation of microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2) and its relevance for the regulation of the neuronal cytoskeleton function. Prog Neurobiol. 2000;61:133–168. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(99)00046-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B, Dodge ME, Tang W, Lu J, Ma Z, Fan CW, et al. Small molecule-mediated disruption of Wnt-dependent signaling in tissue regeneration and cancer. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:100–107. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFeo A, Narla G, Martignetti JA. Emerging roles of Kruppel-like factor 6 and Kruppel-like factor 6 splice variant 1 in ovarian cancer progression and treatment. Mt Sinai J Med. 2009;76:557–566. doi: 10.1002/msj.20150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P, Andrianakos R, Yang Y, Liu C, Lu W. Kruppel-like factor 4 (Klf4) prevents embryonic stem (ES) cell differentiation by regulating Nanog gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:9180–9189. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.077958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizrak D, Brittan M, Alison M. CD133: molecule of the moment. J Pathol. 2008;214:3–9. doi: 10.1002/path.2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng JX, Liu BL, Zhang X. How powerful is CD133 as a cancer stem cell marker in brain tumors. Cancer Treat Rev. 2009;35:403–408. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Wu PY. CD133 as a marker for cancer stem cells: progresses and concerns. Stem Cells Dev. 2009;18:1127–1134. doi: 10.1089/scd.2008.0338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowicki MO, Dmitrieva N, Stein AM, Cutter JL, Godlewski J, Saeki Y, et al. Lithium inhibits invasion of glioma cells; possible involvement of glycogen synthase kinase-3. Neuro Oncol. 2008;10:690–699. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2008-041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotliarova S, Pastorino S, Kovell LC, Kotliarov Y, Song H, Zhang W, et al. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 inhibition induces glioma cell death through c-MYC, nuclear factor-kappaB, and glucose regulation. Cancer Res. 2008;68:6643–6651. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korur S, Huber RM, Sivasankaran B, Petrich M, Morin P, Hemmings BA, et al. GSK3beta regulates differentiation and growth arrest in glioblastoma. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e7443. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Wang L, Zhao S, Ji X, Luo Y, Ling F. beta-Catenin overexpression in malignant glioma and its role in proliferation and apoptosis in glioblastma cells. Med Oncol. 2010;28:608–614. doi: 10.1007/s12032-010-9476-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pu P, Zhang Z, Kang C, Jiang R, Jia Z, Wang G, et al. Downregulation of Wnt2 and beta-catenin by siRNA suppresses malignant glioma cell growth. Cancer Gene Ther. 2009;16:351–361. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2008.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W, Xia Y, Ji H, Zheng Y, Liang J, Huang W, et al. Nuclear PKM2 regulates beta-catenin transactivation upon EGFR activation. Nature. 2011;480:118–122. doi: 10.1038/nature10598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N, Wei P, Gong A, Chiu WT, Lee HT, Colman H, et al. FoxM1 promotes beta-catenin nuclear localization and controls Wnt target-gene expression and glioma tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2011;20:427–442. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng H, Ying H, Wiedemeyer R, Yan H, Quayle SN, Ivanova EV, et al. PLAGL2 regulates Wnt signaling to impede differentiation in neural stem cells and gliomas. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:497–509. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans SM, Judy KD, Dunphy I, Jenkins WT, Nelson PT, Collins R, et al. Comparative measurements of hypoxia in human brain tumors using needle electrodes and EF5 binding. Cancer Res. 2004;64:1886–1892. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-2424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar EE. Glioblastoma, cancer stem cells and hypoxia. Brain Pathol. 2011;21:119–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2010.00460.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borello U, Berarducci B, Murphy P, Bajard L, Buffa V, Piccolo S, et al. The Wnt/beta-catenin pathway regulates Gli-mediated Myf5 expression during somitogenesis. Development. 2006;133:3723–3732. doi: 10.1242/dev.02517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng AP, Ferrando AA, Lee W, Morris JPt, Silverman LB, Sanchez-Irizarry C, et al. Activating mutations of NOTCH1 in human T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Science. 2004;306:269–271. doi: 10.1126/science.1102160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persano L, Pistollato F, Rampazzo E, Della Puppa A, Abbadi S, Frasson C, et al. BMP2 sensitizes glioblastoma stem-like cells to Temozolomide by affecting HIF-1alpha stability and MGMT expression. Cell Death Dis. 2012;3:e412. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2012.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClintick JN, Edenberg HJ. Effects of filtering by Present call on analysis of microarray experiments. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:49. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.