Abstract

Clostridium difficile is a Gram-positive, spore-forming obligate anaerobe and a major nosocomial pathogen of world-wide concern. Due to its strict anaerobic requirements, the infectious and transmissible morphotype is the dormant spore. In susceptible patients, C. difficile spores germinate in the colon to form the vegetative cells that initiate Clostridium difficile infections (CDI). During CDI, C. difficile induces a sporulation pathway that produces more spores; these spores are responsible for the persistence of C. difficile in patients and horizontal transmission between hospitalized patients. While important to the C. difficile lifecycle, the C. difficile spore proteome is poorly conserved when compared to members of the Bacillus genus. Further, recent studies have revealed significant differences between C. difficile and B. subtilis at the level of sporulation, germination and spore coat and exosporium morphogenesis. In this review, the regulation of the sporulation and germination pathways and the morphogenesis of the spore coat and exosporium will be discussed.

Keywords: C. difficile spores, sporulation, germination, spore coat, exosporium

Clostridium difficile infections

The Gram-positive, spore-forming strict anaerobe Clostridium difficile has become the leading cause of nosocomial diarrheas world-wide [1, 2]. Nearly 15% of all hospitalized patients treated with antibiotics develop antibiotic-associated diarrheas (AAD) [3], with ~ 20 to 30% of AAD being caused by C. difficile [1, 4]. The incidence of C. difficile infections (CDI) in some community hospitals is now greater than methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections [5]. The symptoms normally associated with CDI range from mild to severe diarrhea, which can lead to complications such as pseudomembranous colitis and toxic megacolon that carry mortality rates of ~ 5% [4]. The clinical symptoms are caused by the secretion of two large toxins, the enterotoxin TcdA and the cytotoxin TcdB, which cause massive damage to the epithelium and induce strong inflammatory responses [1].

The pathogenesis of CDI relies on the dormant spore morphotype. Because of the anaerobic nature of C. difficile, it is unable to survive in aerobic environments in the vegetative form [6]. During the course of CDI, C. difficile initiates a sporulation pathway that culminates in the production of a dormant spore, allowing C. difficile to persist in the host and disseminate through patient-to-patient contact and environmental contamination. Indeed, strains that are unable to form spores during CDI are unable to persist in the colonic tract of the host and be horizontally transmitted [7]. Because spores are metabolically dormant, C. difficile spores are intrinsically resistant to antibiotics [8], attacks from the host's immune system [9], and once shed into the environment, they are also resistant to bleach-free disinfectants commonly used in hospital settings [10].

Despite the critical importance that C. difficile spores play in CDI, our knowledge of C. difficile spore biology lags far behind that of other well-studied organisms such as Bacillus subtilis, the Bacillus anthracis group and Clostridium perfringens. This is due, in part, to the observation that less than 25% of the spore coat proteins of B. subtilis have homologs in C. difficile, making predictions difficult [11]. Moreover, no orthologs of the GerA family of germinant receptors are predicted for C. difficile, and even conserved components of the germination and sporulation pathways appear to be differentially regulated in C. difficile relative to C. perfringens and B. subtilis [12–17]. The C. difficile spore surface is even more divergent. The spore coat is covered by an additional surface layer, the exosporium, where only the Bacillus cereus group collagen-like BclA orthologs are conserved to some degree [18, 19]. In a proteomic study of C. difficile spore proteins, of the 336 detected spore-associated polypeptides [20], 54 polypeptides in the spore coat insoluble fraction have no functional homologs in other spore-forming bacteria [18]. Although little is known about the role of these outermost spore proteins, recent work has begun dissecting the role of some of these spore coat and exosporium proteins [21–25]. Consequently, in this review we discuss recent progress in the field of C. difficile spore biology, specifically on the processes of sporulation and germination, and spore coat and exosporium assembly.

Sporulation of C. difficile

During CDI, C. difficile initiates a sporulation pathway that produces the dormant spores that lead to persistence and dissemination of CDI within hospitalized patients. The signals that trigger C. difficile sporulation, in vivo or in vitro have not been identified, but they could be related to environmental stimuli such as nutrient starvation, quorum sensing and other unidentified stress factors [26]. In many Bacillus and Clostridium species, the decision to enter sporulation is regulated by several orphan histidine kinases that can phosphorylate the master transcriptional regulator Spo0A [26, 27]. The C. difficile strain 630 genome encodes five orphan histidine kinases (CD1352, CD1492, CD1579, CD1949 and CD2492) [28]. Inactivation of CD2492 reduced spore formation by 3.5-fold relative to wild type, while mutation of spo0A completely abolished spore formation [28]. During in vivo infection, these putative orphan histidine kinases were not up-regulated 4 hr post-infection, or later, suggesting that their expression levels is upregulated at an earlier time point or remain constant during infection [24]. Although the mechanism by which Spo0A is phosphorylated during the initiation of C. difficile sporulation is unclear, the absence of B. subtilis proteins involved in the transfer of the phosphoryl group from the histidine kinases to Spo0A (i.e. Spo0F and Spo0B), suggests that the phosphoryl group is transferred directly from the histidine kinases to Spo0A, as observed in Clostridium acetobutylicum [27]. To date, the only C. difficile orphan histidine kinase shown to autophosphorylate and transfer a phosphate directly to Spo0A is CD1579 [28]. The ability of the remaining orphan histidine kinases to phosphorylate Spo0A remains to be determined.

In B. subtilis, stimulation of the sporulation pathway results in a cascade of sporulation-specific RNA polymerase sigma factor activation (i.e., σF, σE, σG and σK) [29]. As these four sigma factors are conserved in Clostridium species, it was initially thought that the sporulation regulatory pathway was conserved and followed the B. subtilis paradigm [29]. However, recent genome-wide analyses have demonstrated that the C. difficile sporulation process lacks the criss-cross, intercompartmental communication between sporulation-specific sigma factors, as observed in B. subtilis (Box 1) [13, 16, 17]. These studies have revealed that in contrast to B. subtilis: (i) σF is required for the post-translational activation of σG; (ii) σE is dispensable for σG activation, (iii) σG is dispensable for σK activation; (iv) and σK does not undergo proteolytic activation in C. difficile [13, 16, 17, 30]. Moreover, the activation of these sigma factors during C. difficile spore formation does not appear to be governed by the same morphological cues as observed in B. subtilis, as σG activation does not require engulfment to be completed in C. difficile [13, 16]. Despite the observed differences in the regulation of the sporulation-specific sigma factor activity during C. difficile sporulation, relative to B. subtilis, Pereira et al. demonstrated that the sporulation sigma factors exhibit compartment-specific activation similar to B. subtilis, with σF and σG activity being restricted to the forespore and σE and σK activity being restricted to the mother cell [16].

Box 1. Basic architecture of the sporulation pathways of B. subtilis and C. difficile.

Sporulation in B. subtilis in tightly regulated through the criss-cross regulation of four sporulation-specific RNA polymerase sigma factors (σ) (Figure I), two of which are specific to the mother cell (σE and σK) and two of which are specific to the developing forespore (σF and σG) [64]. σF is initially held inactive by an anti-σ factor and only undergoes activation after septum formation is complete, thus coupling σF activation to a morphological event [65]. Active σF leads to expression of genes whose products lead to cleavage of an inhibitory pro-peptide anti-σE through trans-septum signaling [66]. Active σE leads to expression of genes whose products form a channel that post-translationally activate σG in the forespore [67]. Next, active σG induces the expression of genes whose products proteolytically activate σK in the mother cell via trans-septum signaling [68]. σE is also required for σK production and activation. In C. difficile σF is required for the post-translational activation of σG [13] and partially required for the proteolytic activation of σE [13, 17]. σE is required for the production and activation of σK [13, 17], although σK importantly does not require proteolytic activation as it does in B. subtilis and C. perfringens [32, 68]. Notably, σE is dispensable for σG activation in the forespore [13, 16].

Over 200 genes were identified by RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) analysis [13] and microarray analyses [17] as being regulated by these four sporulation-specific sigma factors, and genes dependent on a given sigma factor have been assigned [13, 17]. However, the number of genes in each sporulation-specific sigma factor regulon for C. difficile relative to B. subtilis is striking, with σF regulating 25 vs. 47; σG 50 vs. 104; for σE 97 vs. 282, and σK, 56 vs. 147, respectively [13, 17]. While the inability to synchronize sporulation in C. difficile for these analyses likely reduce the detection of genes that are differentially expressed at low levels, these findings suggest that there may be substantial differences in the regulation of C. difficile spore formation relative to B. subtilis, especially since the phenotypes of a sigG mutant strains of C. difficile and B. subtilis differ significantly.

Notably, the regulatory pathway controlling sporulation in C. difficile also exhibits significant differences with the pathways described in other Clostridium spp. For example, in C. acetobutylicum and C. perfringens, σK activation appears to precede activation of σF [31, 32], which in B. subtilis [29] and C. difficile [13, 16, 17] is the earliest sporulation sigma factor to become activated. In addition, in C. acetobutylicum, σK functions at two discrete developmental stages during sporulation, a regulatory pattern not previously observed in any other sporulating organism [31]. Since the sporulation pathways of C. perfringens and C. acetobutylicum have not been fully defined, more differences are likely to emerge, particularly since C. difficile exhibits greater similarity to members of the Peptostreptococacceae family than to the Clostridiaceae family [33]. While the sporulation sigma factor regulons have not been defined for other Clostridium spp., these studies indicate that there is substantial diversity in the regulation and functions of conserved sporulation sigma factors in the Clostridia and the Bacilli.

C. difficile spore ultrastructure

The overall structure and morphology of C. difficile spores is similar to what has been seen in other endospore-forming bacteria (Box 2), but the outermost layers are particularly different. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) of C. difficile spores [19, 21–23, 25, 34, 35] revealed that the spore coat has distinctive laminations (i.e., lamellae), which are similar to those observed in B. subtilis but different from those in members of the B. cereus group (i.e., B. anthracis) (Figure 1A, B) [36, 37]. It is remarkable that despite these structural similarities, only 25% of the genes encoding spore coat proteins have homologs in C. difficile, suggesting that the components that govern spore coat assembly are divergent to those defined for B. subtilis and/or the B. cereus group [11].

Box 2. Spore structural layer.

Bacterial spores have several structural layers (Figure I) that contribute to their unique resistance properties. The innermost spore compartment is the spore core, which contains the spore DNA and RNA and most enzymes. The most important factors that contribute to the spore resistance properties are the low water content (25–60% of wet weight), elevated levels dipicolonic acid (DPA) (25% of core dry weight) chelated with calcium (Ca-DPA) and the saturation of DNA with α/β-type small acid soluble proteins (SASP) [69]. The core is surrounded by a compressed inner membrane protein [70], which has a similar phospholipid composition to growing bacteria but exhibits very low permeability to small molecules including water [70]. This feature protects the core from DNA damaging molecules [71]. The germ cell wall surrounds the spore inner membrane and becomes the cell wall of outgrowing bacterium. Surrounding the germ cell wall is the thick peptidoglycan layer, with three unique modifications as shown in B. subtilis: (i) ~ every second muramic acid residue in cortex peptidoglycan (PG) has been converted to muramic-δ-lactam (MAL), a modification not found in the germ cell wall; (ii) about one quarter of cortex N-acetylmuramic acid (NAM) residues are substituted with short peptides providing the cortex with a lower degree of crosslinking than the germ cell wall; and (iii) one fourth of the NAM residues carry a single L-alanine residue; this modification is absent in the germ cell wall [72, 73]. The MAL residues are specifically recognized by the cortex lytic enzymes that hydrolyze the spore cortex but not the germ cell wall during germination [74]. The peptidoglycan is surrounded by an outer membrane derived from the mother cell that is essential for spore formation but confers no resistance properties. A proteinaceous coat surrounds the outer membrane. In B. subtilis the coat is composed of ≥ 70 proteins unique to spores, and is essential for spore resistance to commonly used decontaminants [71]. The spore coat is the outermost layer in some species, whereas in others, the exosporium is the outermost layer. The exosporium has been best characterized in B. anthracis, where it plays an important role in pathogenesis [11].

Figure 1. Ultrastructure of Clostridium difficile spores.

(A) Micrographs of thin sections of spores from various C. difficile strains. Upper and lower panels show TEM analyses of strains 630 ribotype 027 (RT12), R20291 RT27, M120 RT78, TL176 RT14, TL178 RT02. It is worth noting that some strains such as 630 and R20291 and TL178 have two different ultrastructural phenotypes. In the upper panel selected spores with a typical exosporium-like structure with roughed electro-dense material are shown, while in the lower panels representative micrographs of spores with less electron dense exosporium-like ultrastructures are shown, suggesting a deficient exosporium layer. Abbreviations: Ex, exosporium; Ct, coat; Cx, cortex. (B) For comparison, the ultrastructure of Bacillus anthracis spores is shown ([37], reprinted with permission of Wiley). Abbreviations: Ex-BL, exosporium basal-layer; Ex-N, Exosporium hair-like nap; Ct, coat; Cx, cortex. (C) The ultrastructure of the spore surface of representative spores of strains C. difficile TL176 and TL178 are shown, highlighting the presence of a highly organized surface of unknown exosporium proteins.

In members of the B. cereus group, the outermost layer is the exosporium, defined for these species, as a distinguishable spore layer with hair-like projections formed in the mother cell compartment, and that does not have a direct interactions with the spore coat layers that surround the cortex [38–40]. In C. difficile, the exosporium is the outermost layer. Thought the C. difficile exosporium has hair-like projections, it lacks many of the B. cereus group exosporium orthologues and the frequently-observed gap that separates the spore coat from the exosporium. Nevertheless, the C. difficile exosporium exhibits a conserved genetic signature to the B. cereus group, since the exosporium glycoproteins encoded by bclA1, bclA2 and bclA3 are also expressed in the mother cell (see below). The stability of the exosporium, remains a matter of controversy because several reports suggest that this layer is fragile and easily lost [21, 22], or absent in spores developed during biofilm formation [39], while other reports indicate that it is a reasonably stable layer that is only removed by proteases and/or sonication treatments [19, 23, 25, 34, 35]. The stability of the exosporium could be related to strain type or the use of proteases in purification procedures. Indeed, recent evidence indicates that proteinase K can remove the exosporium layer while leaving the spore coat intact [34]. Interestingly, the morphology of the exosporium seems to be strain-dependent (Figure 1A, B) [34, 35]. C. difficile 630 spores have an electron-dense, compact exosporium layer (Figure 1A), while spores derived from strains R20291, M120, TL176 and TL178 have a hair-like exosporium layer reminiscent of the B. anthracis exosporium (Figure 1A, B). Interestingly, the ultrastructural organization of the exosporium surface of R20291, M120, TL176 is identical to that of TL178 spores (Figure 1C), suggesting that the exosporium layer of C. difficile strain 630 may be an outlier among C. difficile strains.

While the roles of the outermost layers (i.e. spore coat and exosporium) on CDI and pathogenesis are unclear, recent reports have shed light on their potential functions. The C. difficile spore surface was shown to interact with unidentified surface receptor(s) of intestinal epithelium cells [25]. In vitro infection of macrophages with C. difficile spores revealed that spores become cytotoxic to macrophages possibly by disrupting the phagosomal membrane through spore surface-membrane interactions [41]. The exosporium layer was also shown to confer hydrophobicity to the spore surface affecting its adherence to inert surfaces [35]. C. difficile R20291 spores with a defective exosporium layer adhere better to Caco-2 cells than those with an intact exosporium layer suggesting a potential role in adherence to epithelial surfaces and in the transmission of CDI [23]. Removal of the exosporium layer also increases the ability of C. difficile spores to outgrow into colonies in vitro [34], raising the possibility that C. difficile spores lacking an exosporium are not only able to adhere better to colonic surfaces but also germinate more efficiently. The fraction of spores that have a firmly attached exosporium layer and the half-life of this layer in the environment remain to be determined.

Morphogenesis of the C. difficile spore coat and exosporium

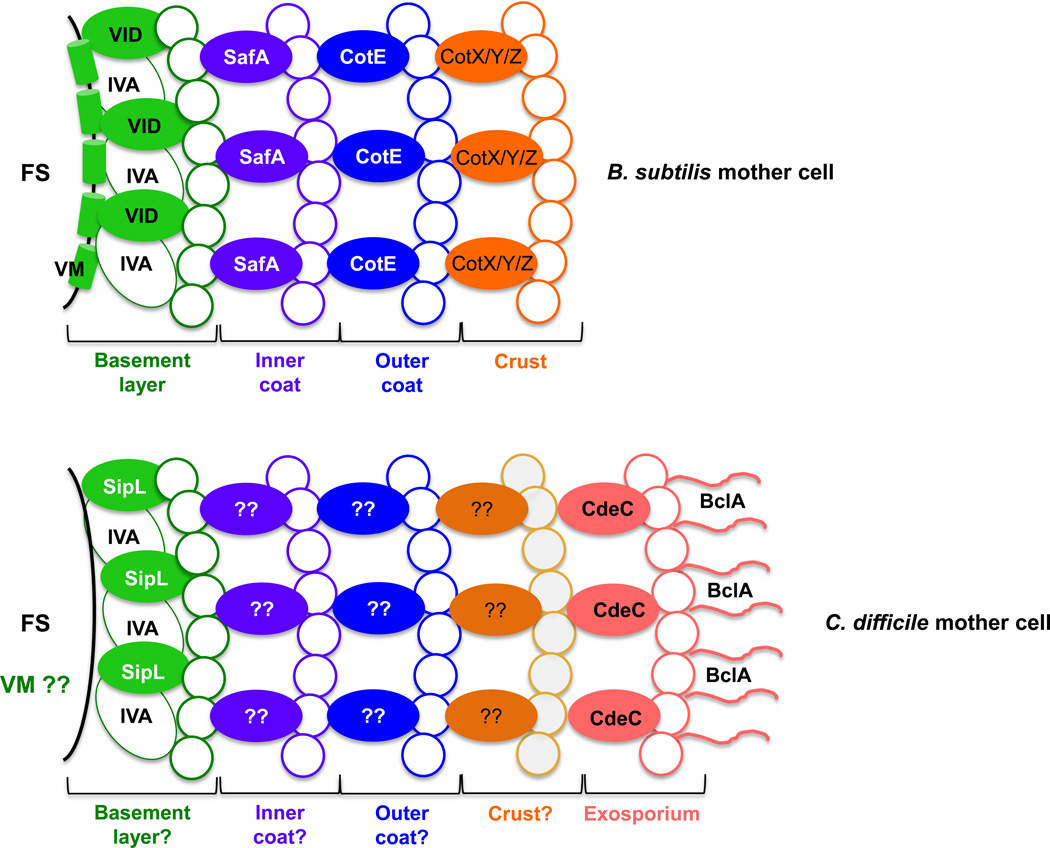

In most endospore-forming bacteria, the first morphological event of sporulation is the formation of a polar septum, which produces a smaller forespore and a larger mother cell [26, 42] (Figure 2). Following forespore engulfment by the mother cell, the mother cell orchestrates the formation of the cortex, coat and exosporium layers [11, 42]. During B. subtilis spore coat assembly, the mother cell encases the forespore with a series of proteinaceous shells, which form the basement layer, inner coat, outer coat and crust layers (Figure 3). In B. subtilis, the formation of the first three coat layers are governed by the morphogenetic factors SpoVM, SpoIVA, SpoVID, SafA and CotE [42]. Homologs for SpoIVA and SpoVM have been identified in C. difficile [43], and C. difficile SpoIVA was recently shown to be essential for coat localization around the forespore similar to B. subtilis [44]. However, in contrast to B. subtilis, C. difficile SpoIVA was dispensable for cortex synthesis [38, 44, 45]. Despite the morphological similarities between the coat layers of C. difficile and B. subtilis spores [11], there are no homologs of B. subtilis SpoVID, SafA and CotE in C. difficile [43], indicating that divergent proteins likely functionally substitute for these morphogenetic proteins during C. difficile spore assembly. Indeed, Putman et al. identified a previously uncharacterized protein, CD3567, as a novel spore morphogenetic protein in Clostridia [44]. The C. difficile cd3567− mutant strain phenocopied the spoIVA− mutant strain in that coat assembly was mislocalized to the mother cell cytosol [44]. The C-terminal LysM domain of CD3567 was shown to directly bind with SpoIVA, suggesting that CD3567 (renamed SipL for “SpoIVA Interacting Protein L”) and SpoIVA form a complex that may drive coat assembly around the forespore [44] (Figure 3). Indeed, SipL may function analogously to B. subtilis SpoVID in helping to transition the spore coat from a mother cell proximal cap to full encasement [46–48]. TEM analyses of sporulating cells of sipL− and spoVID− mutant strains indicate that they exhibit a tethered coat phenotype, with the coat appearing to be loosely attached to the mother cell proximal pole of the forespore [44]. In B. subtilis, SpoIVA is required for the recruitment of the morphogenetic protein SafA, while both SpoIVA and SpoVID are required for recruitment of the morphogenetic protein CotE [42], yet given the absence of homologues of these proteins in C. difficile further research is needed to identify additional morphogenetic spore coat proteins recruited by C. difficile SpoIVA, SipL and/or SpoVM.

Figure 2. Main morphogenetic stages of the process of sporulation.

Upon nutrient limitation, cells cease growth and initiate sporulation. Asymmetric cell division generates a smaller forespore compartment and a larger mother cell. Following completion of DNA segregation, the mother cell proceeds to engulf the forespore. During the initiation of spore metabolic dormancy and compaction of the spore DNA, the mother cell mediates the development of the forespore into the spore through the production of the cortex and the inner and outer coats. Next, the mother cell lyses and releases the mature spore. In the presence of the appropriate environmental stimulus, the dormant spore initiates the process of germination that leads to the re-initiation of vegetative growth. Abbreviations: MC, mother cell compartment; FS, forespore compartment; MS, mature spore.

Figure 3. Schematic of B. subtilis and C. difficile surface layers.

The major proteinaceous layers defined by McKenney et al. [42] are shown. B. subtilis lacks an exosporium layer. Based on localization of SpoIVA and SpoVID in B. subtilis, C. difficile SpoIVA and SipL are shown localizing to a putative basement layer. It is unclear whether C. difficile SpoVM localizes to the forespore membrane similar to B. subtilis SpoVM (indicated by VM??) [42]. Morphogenetic proteins required for the assembly of the indicated layer are labeled; morphogenetic proteins for the putative inner and outer coat layers of C. difficile are unknown (? indicates that it remains unclear whether discrete layers defined by specific morphogenetic proteins as defined in B. subtilis exist in C. difficile spores). It is also unclear whether C. difficile spores have a crust layer. The morphogenetic protein of the exosporium layer, CdeC, and the outer most exosporium protein, BclA1, are shown. The location of BclA2 and BclA3 remain unknown. Abbreviations: FS, forespore compartment; VM, SpoVM; VID, SpoIVD; IVA, SpoIVA; ??, unidentified proteins.

In B. anthracis and C. difficile spores, the exosporium covers the coat layers (Box 2 and Figure 3). As mentioned earlier, the C. difficile spore exosporium has a hair-like nap that looks scruffier and less organized than that of the B. anthracis exosporium (Figure 1). The C. difficile exosporium also lacks the clear gap/inner coat space observed in B. anthracis spores (Figure 1). Although the precise composition of the exosporium remains unclear, two recent studies have made some progress on the proteins required for exosporium formation (Table 1) [19, 23]. Three paralogues of the B. anthracis collagen-like glycoprotein (i.e., BclA) are encoded in the C. difficile 630 genome (i.e., bclA1 [CD0332], bclA2 [CD3230] and bclA3 [CD3349]). These proteins contain three domains: (i) an N-terminal domain of variable size; (ii) a collagen-like domain; (iii) and a C-terminal domain. [19, 49]. Recently, Pizarro-Guajardo et al. demonstrated that all three are expressed in the mother cell compartment and that the N-terminal domain of each BclA paralogue is sufficient to localize a tdTOMATO reporter protein to the surface of C. difficile spores during sporulation [19]. This finding is consistent with these proteins being under the control of σK [13, 17]. This work also demonstrated that BclA1 undergoes post-translational cleavage and localizes uniquely to the exosporium layer of C. difficile 630 spores with its C-terminal domain in an inward orientation (Figure 3) [19]. However, the precise role of the other BclA paralogues remains unclear.

Table 1.

Main proteins of Clostridium difficile sporulation, germination and structural components

| Germination encoded protein (locus tag, strain) | MWa | Spore localizationb | Function | Refs |

| Putative cortex lytic enzyme (CD3563, strain 630) | 19 | ND | CD3563 mutant spores germinate as wild-type spores | [62] |

| CspBA (CD2247, strain 630) | 125 | ND | Essential for processing of pro-SleC into mature SleC and spore germination; spores of a cspBAC mutant have >107 -fold lower viability than wild-type spores | [14] |

| SleC (CD0551, strain 630) | 47 | ND | Essential for spore peptidoglycan cortex degradation and germination; spores of a sleC mutant had ~ 107 -fold lower viability in presence of taurocholate | [14, 62] |

| CspC (CD2246, strain 630) | 61 | ND | Bile acid germinant receptor | [15] |

| Spore structure/morphogenesis encoded protein (locus tag, strain) | MW | Spore localization | Function or observations | Refs |

| SpoIVA (CD2629, strain 630) | 56 | Basement layer? | Essential for coat localization around the forespore and functional spore formation | [44] |

| SipL (CD3567, strain 630) | 59 | Basement layer? | Essential for coat localization around the forespore and functional spore formation; sipL mutation reduces SpoIVA levels in sporulating cells | [44] |

| CotA (CD1613, strain 630) | 34 | Exosporium | cotA mutation produces ~ 50% of spores with an amorphous structure; removed from the spore surface by sonication; essential for coat and exosporium formation; required for lysozyme, ethanol and heat resistance | [22] |

| CotB (CD1511, strain 630) | 35 | Exosporium | cotB mutant spores exhibit wild-type ultrastructure; slight effect on heat resistance | [22] |

| CotCB (CD0598, strain 630) | 21 | Coat and exosorium? | Putative manganese catalase, cotCB mutant spores exhibits wild-type ultrastructure; slight effect on heat resistance | [22] |

| CotD (CD2401, strain 630) | 21 | Exosporium | Putative manganese catalase, cotD mutant spores exhibits wildtype ultrastructure; slight effect on heat resistance; sonication removes CotD | [22] |

| CotE (CD1433, strain 630) | 81 | Exosporium | Putative peroxiredoxin chitinase, cotE mutant spores exhibits wild-type ultrastructure; removed from the spore surface by sonication; slight effect on heat resistance | [22] |

| CotF (CD0597, strain 630) | 11 | Exosporium | cotF mutant spores exhibits wild-type ultrastructure; removed from the spore surface by sonication | [22] |

| CotJB2 (CD2400, strain 630) | 11 | ND | ND | |

| CotG (CD1567, strain 630) | 27 | Exosporium | Putative manganese catalase, no mutant; removed from the spore surface by sonication | [22] |

| SodA, (CD1631, strain 630) | 28 | Coat | Putative superoxide dismutase, no role in heat, Virkon, hydrogen peroxide and ethanol resistance | [22] |

| BclA1 (CD0332, strain 630) | 67.6 | Exosporium | Localizes to the spore exosporium through its N-terminal domain (NTD); SPk-treatment removes BclA1 from the spore surface.; oriented with its NTD and C-terminal domain (CTD) inwards and outwards, respectively; has a central collagen-like domain | [19] |

| BclA2 (CD3230, strain 630) | 48.9 | Exosporium | Localizes to the spore surface through NTD; has a central collagen-like domain | [19] |

| BclA3 (CD3349, strain 630) | 58.1 | Exosporium | Localizes to the spore surface through its NTD; has a central collagen-like domain | [19] |

| CdeC (CD1067, strain 630; CDR0926; strain R20291) | 44.6 | Exosporium | Essential exosporium morphogenetic factor; SPk-treatment removes CdeC from the spore surface; required for the correct assembly of the spore coat cdeC spores have lower resistance, permeable spore inner membrane and a more hydrated spore core | [23] |

MW, molecular weight in kDa.

Abbreviations: ND, not determined; ?, indicates that location has not been clearly established.

Barra-Carrasco et el. used genetic analysis to demonstrate that the cysteine-rich exosporium protein, CdeC (CD1067), which is unique to C. difficile, is accessible to antibodies and essential for the proper assembly of the exosporium of C. difficile spores [23]. A mutation in C. difficile cdeC dramatically reduced the abundance of the exosporium layer leading to defective coat and exosporium assembly. TEM analyses of cdeC mutant spores revealed that while the outer coat layer was thinner than that of wild-type spores, the inner coat layer was thicker than that of wild-type spores [23]. These observations suggest that CdeC could act as an anchoring protein at the interface of the spore coat and exosporium layers (Figure 3 and Table 1). Nevertheless, how CdeC recruits the remaining exosporium proteins is unclear. cdeC mutant spores also have a higher spore core water content and are more sensitive to ethanol and heat treatment than wild-type spores [23], indicating that CdeC might play a pleiotropic role during early spore formation. Further studies to define the pleiotropic role of CdeC during sporulation are warranted.

Several recent studies have also identified spore proteins that localize to the surface of C. difficile strain 630 spores (Table 1) [21, 22]. Surface localization of these proteins was determined by immunofluorescence and/or detection of the protein in the supernatant fraction of sonicated spores [22]. One group of these proteins consisted of proteins predicted to have manganase catalase activity; these include CotCB (CD0598, based on the 630 gene numbering system), CotD (CD2401) and CotG (CD1567) [21, 22]. Catalase activity was observed for the recombinant proteins of CotD and CotG, but was barely detectable for CotCB [22]. Since sonication of C. difficile spores abrogated the detection of CotD and CotG by immunofluorescence, these proteins may be localized to the exosporium or their presence depends on an intact exosporium [21, 22]. The precise location of CotCB could not be precisely determined, since the antibody generated appears to lack specificity [22]. CotD and CotCB are homologs of the B. subtilis outer coat protein CotJC, but no ultrastructural defects in the spore coat were observed in cotD and cotCB spores (Table 1) [22]. The function of C. difficile CotG (CD1567) is unknown [22].

Additional C. difficile spore surface-localized proteins with defined enzymatic activities include SodA (CD1631) (Table 1), a homolog of the B. subtilis superoxide dismutase (SodA), and CotE, a bifunctional peroxiredoxin reductase and chitinase. In B. subtilis, H2O2 plays a role in spore coat assembly by serving as a substrate for the SodA enzyme to crosslink tyrosine-rich spore coat proteins together [50]. However, loss of C. difficile sodA had no effect on spore ultrastructure or spore resistance [22]. The C. difficile CotE (CD1433) protein can be partially removed from the spore surface by sonication [22]. Despite the in vitro peroxidoredoxin reductase and chitinase activity, C. difficile cotE mutant spores have no obvious ultrastructural defects even though C. difficile CotE is predicted to be located in the exosporium (Table 1) [21, 22]. It should be noted that the C. difficile CotE bears no sequence or functional homology to the B. subtilis CotE protein, which is a critical outer coat morphogenetic protein [42] (Figure 3).

A third group of surface-localized proteins, consisting of three hypothetical proteins, has also identified and characterized. These include CotA (CD1613), CotB (CD1511) and CotF (CD0597, homologous to B. subtilis CotJB) (Table 1). Strikingly, C. difficile cotA mutant spores had an unusual phenotype; approximately half of the spores examined by TEM exhibited major morphological defects and lacked the electron dense coat layer [22]. In addition cotA mutant spores were also more sensitive to lysozyme [22]. These observations suggest that CotA plays an essential role in spore coat and exosporium assembly [22]. By contrast, no detectable differences in spore ultrastructure or resistance were observed in C. difficile cotB spores; the role of CotF remains to be investigated [51]. Detection of CotA, CotB and CotF was also removed by sonication, suggesting that they either localize to the exosporium of C. difficile 630 spores or require an intact exosporium.

The genes encoding the spore surface proteins identified to date [19, 21–23] have all been detected as being induced during sporulation in global transcriptional analyses [13, 17]. bclA1, bclA2, bclA3, cdeC, cotA, cotCB, cotD, and cotE genes were determined to be dependent on σK for expression. The cotG and sodA genes were identified as σG-dependent genes. Interestingly, cotB was identified as a σE-dependent gene, with a σE-dependent promoter mapped by Saujet et al. [17]. Since B. subtilis σE regulates genes whose products are involved in inner coat formation [26, 42], it is somewhat surprising that CotB was localized to the spore surface. Since σG activity is compartmentalized in the C. difficile forespore [16], the localization of SodA and CotG on the spore surface suggests the existence of mechanisms for transporting forespore-produced proteins across the membranes to allow for incorporation into the spore surface. While these studies [19, 21–23] have identified proteins required for the correct assembly of the spore coat and exosporium layer, further studies are needed to define the structural components of the outermost layers of C. difficile spores and the interactions between spore surface proteins.

Germination of C. difficile spores

Germination by C. difficile spores is an important step for initiating CDI [52]. Bacterial spore germination is induced when specific germinant receptors (GRs) sense the presence of species-specific small molecules (germinants). In Bacillus spp. and some Clostridium spp., binding of germinant to germinant receptors triggers the release of monovalent cations (H+, Na+, and K+) and spore core stores of dipicolinc acid (DPA) chelated to Ca2+ (Ca-DPA). In B. subtilis, Ca-DPA release leads to the activation of cortex hydrolases that degrade the peptidoglycan cortex layer, which allows for core hydration and resumption of metabolism in the spore core. In C. perfringens, activation of the cortex hydrolase, SleC, depends on its proteolytic cleavage by the Csp family of subtilisin-like serine proteases, CspA, CspB, and/or CspC, although C. perfringens strains exhibit variability in the number of Csp proteases that they encode [12, 53–55].

In contrast with Bacillus and Clostridium spores which sense nucleosides, sugars, amino acids, and ions (Box 3) [12], C. difficile spores germinate in response to the combination of specific bile salts [i.e., cholate and its derivatives (taurocholate, glycocholate, cholate and deoxycholate)] and L-glycine acting as a co-germinant [56–58]. However, some C. difficile strains are able to germinate in rich medium without taurocholate, suggesting that the mechanisms and/or specificity of the GR(s) are complex [59]. Since the genomes of all sequenced C. difficile strains lack homologues of the germinant receptors, a different mechanism likely initiates C. difficile spore germination. Indeed, a recent study by Francis et al. [15] demonstrated that CspC, one of the three Csp serine proteases encoded by C. difficile, acts as a bile salt germinant receptor (Table 1). Interestingly, C. difficile CspC (and CspA) is predicted to be catalytically dead, since two of the three catalytic triad residues (including, the catalytic Ser) are mutated in C. difficile [14]. Notably, a single point mutation in CspC (G457R) altered the germinant specificity of C. difficile spores [15] and allowed spores to germinate in the presence of chenodeoxycholate, which is a potent competitive inhibitor of taurocholate-mediated germination [60]. While the interaction of a germinant with CspC has not been demonstrated biochemically, these results provide compelling evidence that CspC is a bile salt-specific GR [15]. Notably, CspC is required for Ca-DPA release from spores in response to glycine and taurocholate [15], but whether CspC-induced Ca-DPA release is due to direct activation of DPA channels or activation of the cortex hydrolysis machinery is unclear.

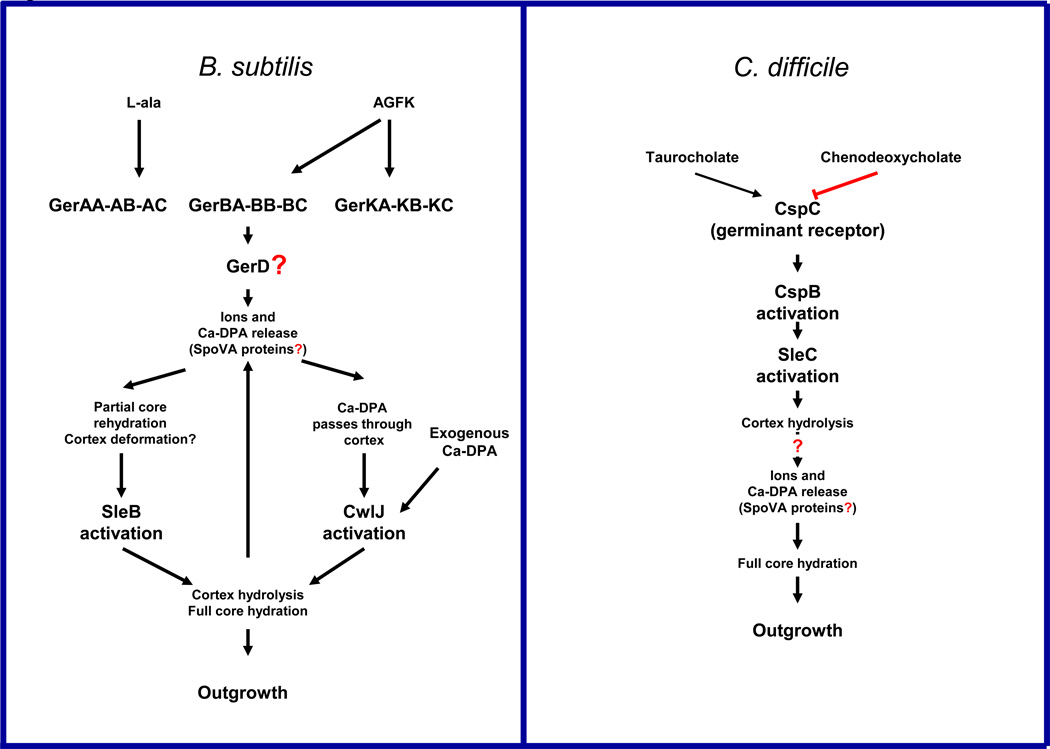

Box 3. Tentative models for information flow during spore germination of B. subtilis and C. difficile.

Bacterial spores may become reactivated within minutes (i.e., ~ 5 min) in the presence of germinants (i.e., amino acids, sugars and salts) to transform back to their vegetative form [12]. Nutrient germinants are sensed by their cognate germinant receptor (GR), which in B. subtilis is localized to the spore's inner membrane [12] Upon germinant binding to their cognate GR, a series of biophysical events occur (Figure I) that includes the release of monovalent cations (i.e., K+ and Na+) and the core’s deposit of dipicolinic acid (DPA) chelated mainly to Ca2+ (Ca-DPA) [12]. Release of Ca-DPA is thought to occur through gated channels located in the spore inner membrane composed in part by the SpoVA proteins [12]. In B. subtilis, Ca-DPA release activates the cortex lytic enzyme CwlJ, while the redundant SleB seems to be activated by a partial deformation of the spore cortex [12]. Degradation of the cortex peptidoglycan (PG) by the cortex lytic enzymes allows full core hydration, resumption of metabolism [12, 75] and loss of all resistance properties normally associated with a spore [12].

Although C. difficile lacks the GerA family of germinant receptors, a protease-like protein (CspC) acts as the taurocholate germinant receptor. Loss of CspC abolishes C. difficile spore germination and DPA release [15]. CspC is thus required for outgrowth of C. difficile spores. Similar to C. perfringens, C. difficile lacks GerD homologs suggesting two possible mechanisms of progression of the germination process. Presumably, CspC directly activates CspB, which in turn processes pro-SleC into active SleC leading to the complete degradation of the spore PG cortex and stimulation of DPA release. Alternatively, it is also tempting to speculate that CspC might be localized to the outer surface of the spore's inner membrane thereby interacting with proteins that are important for DPA release. Absence of CspBA and CspC or SleC completely blocks germination and outgrowth of C. difficile spores [61, 62].

Several studies have attempted to provide a quantitative measure of the interaction of C. difficile spores with bile salt germinants. In these studies, chenodeoxycholate inhibits taurocholate-mediated spore germination and appears to interact more tightly with C. difficile spores than does taurocholate [60]. This observation suggests that inhibitors of spore germination may have therapeutic value in preventing CDI. Indeed, Howerton et al. demonstrated that administering a potent inhibitor of C. difficile spore germination to mice prevents CDI [52].

The machinery involved in the degradation of the C. difficile spore cortex is similar to that found in C. perfringens spores in that the Csps and SleC are all essential for spore germination in C. difficile (Table 1) [14, 15, 53, 54, 61, 62]. However, the signaling pathway leading to SleC activation in response to germinant differs significantly between these two species. In C. difficile, the CspB and CspA serine proteases are encoded as a cspBA gene fusion, where the CspA portion of CspBA lacks an intact catalytic triad [14]. The CspBA fusion protein undergoes interdomain cleavage during spore formation, leading to the release of CspB species that is incorporated to the spore [14]; the level of CspB incorporation into the spore may depend on SleC [14]. Notably, the serine protease activity of C. difficile CspB is required for efficient processing of pro-SleC into mature SleC, since an S461A mutation in CspBA leads to a ~20-fold reduction in spore germination [14].

The precise signaling pathway that activates the C. difficile cortex hydrolyzing machinery starting from the recently identified bile salt germinant receptor CspC [15] remains unclear. Presumably CspC activates CspB upon sensing the bile salt germinant (Box 3). Activated CspB, in turn, likely activates the SleC cortex hydrolase. Interestingly, a recent study demonstrated that SleC in vitro activity does not require proteolytic cleavage [63]. Further studies are needed to define the in vivo role of the cortex hydrolysis machinery as well as other components essential for Ca-DPA release from the spore core. For example, the role of the SpoVA proteins, which regulate Ca-DPA release in B. subtilis and C. perfringens [12], in C. difficile remains to be investigated. In summary, although the main components of the spore germination machinery of C. difficile have been identified [14, 15, 61, 62], further studies are needed to define the signaling pathway that synchronize these components during germination.

Concluding remarks and future perspectives

As C. difficile spores are essential for the persistence and dissemination of C. difficile infections, understanding the mechanisms by which spores are formed, germinate, and interact with host surfaces will be essential for developing strategies for disrupting C. difficile disease transmission and spread. Although some progress has been made in understanding the biology of C. difficile spore formation, many key questions remain unanswered (Box 4). It is expected that further work will allow us to fully understand the mechanisms that regulate the initiation of sporulation by identifying the proteins that can lead to Spo0A phosphorylation and orchestrate the activation of the four sporulation-specific RNA polymerase sigma factors. Further work is also expected to uncover the assembly mechanism of the spore coat and exosporium by defining the role of several spore coat / exosporium morphogenetic factors. Due to the relevance of spore germination for the progression of CDI, it is of interest to define how the novel taurocholate-GR, CspC, and the unidentified glycine GR are synchronized with the remaining germination machinery to regulate DPA release and cortex hydrolysis. Studies to define their in vivo role are essential for the successful development of alternative therapeutic strategies.

Box 4. Outstanding questions.

What environmental signals initiate C. difficile sporulation?

Which histidine kinases are involved in the initiation of C. difficile sporulation?

How are the sporulation sigma factors regulated during sporulation? In particular, how is σG post-translationally activated in a σF-dependent manner? How is σK activity regulated?

Given the unique composition of the outer most layers of C. difficile spores, what is the role of the exosporium in C. difficile spore-host interactions? What proteins are required for formation and function of the exosporium layer? Do the surface-exposed C. difficile BclA proteins play any role in host–spore interactions?

Given the absence of the main B. subtilis spore coat protein homologs, what proteins are involved in the morphogenesis of the C. difficile spore coat?

How does the CspC receptor transduce the germination signal?

How is the C. difficile serine protease, CspB, activated?

How are the co-germinants L-glycine and/or L-histidine recognized?

Figure I Box I.

Sporulation in endospore-forming B. subtilis and C. difficile. Models of the global regulatory process of the four main sporulation specific sigma factors in B. subtilis and C. difficile.

Figure I Box 2.

Structural layers of bacterial spores. The main layers of bacterial spore structure are shown and not drawn to scale. The exosporium and spore coat may have sub-layers which are not shown. The exosporium layer is present in some species. Figure has been modified from [75] with permission from Elsevier.

Figure I Box 3.

Tentative models for information flow during spore germination of B. subtilis and C. difficile. Arrows denote the preference of the germinants for the GRs, and upward arrows indicate that cortex hydrolysis might increase the rate of DPA release. Red line indicates that chenodeoxycholate inhibits CspC activation. Question marks indicate that there is suggestive, but no conclusive experimental evidence; AGFK, is a mixture of L-asparagine, glucose, fructose and KCl.

Highlights.

-

-

The Clostridium difficile sporulation process is substantially different than the Bacillus subtilis paradigm.

-

-

Novel and unidentified proteins are involved in the formation of the C. difficile spore coat layer.

-

-

C. difficile possesses an exosporium layer that may play a role in pathogenesis.

-

-

The catalytically dead serine protease, CspC, acts as a bile salt germination receptor.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from Fondo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología de Chile (FONDECYT Grant 1110569), by a grant from the Research Office of Universidad Andres Bello (DI-275-R/13), and by a grant from Fondo de Fomento al Desarrollo Científico y Tecnológico (FONDEF) CA13I10077 to D.P-S. A.S. is a Pew Scholar in the Biomedical Sciences, supported by The Pew Charitable Trusts, and is supported by Award Number R00GM092934 and start-up funds from Award Number P20RR021905 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. The content is solely the responsibility of the author(s) and does not necessarily reflect the views of either the Pew Charitable Trusts or the National Institute of General Medical Sciences or the National Institute of Health. J.A.S acknowledges support by the American Heart Association National Scientist Development grant (No. 11SDG7160013), and support by Award Number R21AI07640 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases or the National Institutes of Health. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Rupnik M, et al. Clostridium difficile infection: new developments in epidemiology and pathogenesis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7:526–536. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kelly CP, LaMont JT. Clostridium difficile--more difficult than ever. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1932–1940. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0707500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McFarland LV. Epidemiology, risk factors and treatments for antibiotic-associated diarrhea. Dig Dis. 1998;16:292–307. doi: 10.1159/000016879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hernández-Rocha C, et al. Infecciones causadas por Clostridium difficile: una visión actualizada. Revista Chilena de Infectología. 2012;29:434–445. doi: 10.4067/S0716-10182012000400011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller BA, et al. Comparison of the burdens of hospital-onset, healthcare facility-associated Clostridium difficile Infection and of healthcare-associated infection due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in community hospitals. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2011;32:387–390. doi: 10.1086/659156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jump RL, et al. Vegetative Clostridium difficile survives in room air on moist surfaces and in gastric contents with reduced acidity: a potential mechanism to explain the association between proton pump inhibitors and C. difficile-associated diarrhea? Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007;51:2883–2887. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01443-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deakin LJ, et al. Clostridium difficile spo0A gene is a persistence and transmission factor. Infect Immun. 2012;80:2704–2711. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00147-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baines SD, et al. Activity of vancomycin against epidemic Clostridium difficile strains in a human gut model. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;63:520–525. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paredes-Sabja D, Sarker MR. Interactions between Clostridium perfringens spores and Raw 264.7 macrophages. Anaerobe. 2012;18:148–156. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2011.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ali S. Spread and persistence of Clostridium difficile spores during and after cleaning with sporicidal disinfectants. J Hosp Infect. 2011;79:97–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2011.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henriques AO, Moran CP., Jr Structure, assembly, and function of the spore surface layers. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2007;61:555–588. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.61.080706.093224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paredes-Sabja D, et al. Germination of spores of Bacillales and Clostridiales species: mechanisms and proteins involved. Trends Microbiol. 2011;19:85–94. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fimlaid KA, et al. Global analysis of the sporulation pathway of Clostridium difficile. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003660. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adams CM, et al. Structural and functional analysis of the CspB protease required for Clostridium spore germination. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003165. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Francis MB, et al. Bile acid recognition by the Clostridium difficile germinant receptor, CspC, is important for establishing infection. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003356. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pereira FC, et al. The spore differentiation pathway in the enteric pathogen Clostridium difficile. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003782. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saujet L, et al. Genome-wide analysis of cell type-specific gene transcription during spore formation in Clostridium difficile. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003756. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abhyankar W, et al. In pursuit of protein targets: proteomic characterization of bacterial spore outer layers. J Proteome Res. 2013;12:4507–4521. doi: 10.1021/pr4005629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pizarro-Guajardo M, et al. Characterization of the collagen-like exosporium protein, BclA1, of Clostridium difficile spores. Anaerobe. 2014;25:18–30. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lawley TD, et al. Proteomic and genomic characterization of highly infectious Clostridium difficile 630 spores. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:5377–5386. doi: 10.1128/JB.00597-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Permpoonpattana P, et al. Surface layers of Clostridium difficile endospores. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:6461–6470. doi: 10.1128/JB.05182-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Permpoonpattana P, et al. Functional characterization of Clostridium difficile spore coat proteins. J Bacteriol. 2013;195:1492–1503. doi: 10.1128/JB.02104-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barra-Carrasco J, et al. The Clostridium difficile exosporium cystein (CdeC) rich protein is required for exosporium morphogenesis and coat assembly. J Bacteriol. 2013;195:3863–3875. doi: 10.1128/JB.00369-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Janoir C, et al. Insights into the adaptive strategies and pathogenesis of Clostridium difficile from in vivo transcriptomics. Infect Immun. 2013;81:3757–3769. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00515-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paredes-Sabja D, Sarker MR. Adherence of Clostridium difficile spores to Caco-2 cells in culture. J Med Microbiol. 2012;61:1208–1218. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.043687-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Higgins D, Dworkin J. Recent progress in Bacillus subtilis sporulation. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2012;36:131–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2011.00310.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steiner E, et al. Multiple orphan histidine kinases interact directly with Spo0A to control the initiation of endospore formation in Clostridium acetobutylicum. Mol Microbiol. 2011;80:641–654. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07608.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Underwood S, et al. Characterization of the sporulation initiation pathway of Clostridium difficile and its role in toxin production. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:7296–7305. doi: 10.1128/JB.00882-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Hoon MJ, et al. Hierarchical evolution of the bacterial sporulation network. Curr Biol. 2010;20:R735–R745. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.06.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haraldsen JD, Sonenshein AL. Efficient sporulation in Clostridium difficile requires disruption of the sigmaK gene. Mol. Microbiol. 2003;48:811–821. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03471.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Al-Hinai MA, et al. sigmaK of Clostridium acetobutylicum is the first known sporulation-specific sigma factor with two developmentally separated roles, one early and one late in sporulation. J Bacteriol. 2014;196:287–299. doi: 10.1128/JB.01103-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harry KH, et al. Sporulation and enterotoxin (CPE) synthesis are controlled by the sporulation-specific sigma factors SigE and SigK in Clostridium perfringens. J. Bacteriol. 2009;191:2728–2742. doi: 10.1128/JB.01839-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yutin N, Galperin MY. A genomic update on clostridial phylogeny: Gram-negative spore formers and other misplaced clostridia. Environ Microbiol. 2013;15:2631–2641. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Escobar-Cortes K, et al. Proteases and sonication specifically remove the exosporium layer of spores of Clostridium difficile strain 630. J Microbiol Methods. 2013;93:25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2013.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Joshi LT, et al. The contribution of the spore to the ability of Clostridium difficile to adhere to surfaces. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:7671–7679. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01862-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bailey-Smith K, et al. The ExsA protein of Bacillus cereus is required for assembly of coat and exosporium onto the spore surface. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:3800–3806. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.11.3800-3806.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Steichen CT, et al. Non-uniform assembly of the Bacillus anthracis exosporium and a bottle cap model for spore germination and outgrowth. Mol Microbiol. 2007;64:359–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Giorno R, et al. Morphogenesis of the Bacillus anthracis spore. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:691–705. doi: 10.1128/JB.00921-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Semenyuk EG, et al. Spore formation and toxin production in Clostridium difficile biofilms. PLoS One. 2014;9:e87757. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Driks A. Surface appendages of bacterial spores. Mol Microbiol. 2007;63:623–625. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Paredes-Sabja D, et al. Clostridium difficile spore-macrophage interactions: spore survival. PLoS One. 2012;7:e43635. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McKenney PT, et al. The Bacillus subtilis endospore: assembly and functions of the multilayered coat. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2013;11:33–44. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Galperin MY, et al. Genomic determinants of sporulation in Bacilli and Clostridia: towards the minimal set of sporulation-specific genes. Environ Microbiol. 2012;14:2870–2890. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2012.02841.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Putnam EE, et al. SpoIVA and SipL are Clostridium difficile spore morphogenetic proteins. J Bacteriol. 2013;195:1214–1225. doi: 10.1128/JB.02181-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ebmeier SE, et al. Small proteins link coat and cortex assembly during sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 2012;84:682–696. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08052.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McKenney PT, Eichenberger P. Dynamics of spore coat morphogenesis in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 2012;83:245–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07936.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ozin AJ, et al. SpoVID guides SafA to the spore coat in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:3041–3049. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.10.3041-3049.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang KH, et al. The coat morphogenetic protein SpoVID is necessary for spore encasement in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 2009;74:634–649. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06886.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sebaihia M, et al. The multidrug-resistant human pathogen Clostridium difficile has a highly mobile, mosaic genome. Nat. Genet. 2006;38:779–786. doi: 10.1038/ng1830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Henriques AO, et al. Involvement of superoxide dismutase in spore coat assembly in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:2285–2291. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.9.2285-2291.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Permpoonpattana P, et al. Immunization with Bacillus spores expressing toxin A peptide repeats protects against infection with Clostridium difficile strains producing toxins A and B. Infect Immun. 2011;79:2295–2302. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00130-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Howerton A, et al. A new strategy for the prevention of Clostridium difficile infection. J Infect Dis. 2013;207:1498–1504. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Paredes-Sabja D, et al. SleC is essential for cortex peptidoglycan hydrolysis during germination of spores of the pathogenic bacterium Clostridium perfringens. J. Bacteriol. 2009;191:2711–2720. doi: 10.1128/JB.01832-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Paredes-Sabja D, et al. The protease CspB is essential for initiation of cortex hydrolysis and DPA release during spore germination of Clostridium perfringens type A food poisoning isolates. Microbiology. 2009;155:3464–3472. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.030965-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shimamoto S, et al. Partial characterization of an enzyme fraction with protease activity which converts the spore peptidoglycan hydrolase (SleC) precursor to an active enzyme during germination of Clostridium perfringens S40 spores and analysis of a gene cluster involved in the activity. J. Bacteriol. 2001;183:3742–3751. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.12.3742-3751.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sorg JA, Sonenshein AL. Bile salts and glycine as co-germinants for Clostridium difficile spores. J. Bacteriol. 2008;190:2505–2512. doi: 10.1128/JB.01765-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wheeldon LJ, et al. Histidine acts as a co-germinant with glycine and taurocholate for Clostridium difficile spores. J Appl Microbiol. 2011;110:987–994. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2011.04953.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Howerton A, et al. Mapping interactions between germinants and Clostridium difficile spores. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:274–282. doi: 10.1128/JB.00980-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Heeg D, et al. Spores of Clostridium difficile clinical isolates display a diverse germination response to bile salts. PloS one. 2012;7:e32381. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sorg JA, Sonenshein AL. Chenodeoxycholate is an inhibitor of Clostridium difficile spore germination. J. Bacteriol. 2009;191:1115–1117. doi: 10.1128/JB.01260-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cartman ST, Minton NP. A mariner-based transposon system for in vivo random mutagenesis of Clostridium difficile. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010;76:1103–1109. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02525-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Burns DA, et al. SleC is essential for germination of Clostridium difficile spores in nutrient-rich medium supplemented with the bile salt taurocholate. J. Bacteriol. 2010;192:657–664. doi: 10.1128/JB.01209-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gutelius D, et al. Functional analysis of SleC from Clostridium difficile: an essential lytic transglycosylase involved in spore germination. Microbiology. 2014;160:209–216. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.072454-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Losick R, Stragier P. Crisscross regulation of cell-type-specific gene expression during development in B. subtilis. Nature. 1992;355:601–604. doi: 10.1038/355601a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Margolis P, et al. Establishment of cell type by compartmentalized activation of a transcription factor. Science. 1991;254:562–565. doi: 10.1126/science.1948031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hofmeister AE, et al. Extracellular signal protein triggering the proteolytic activation of a developmental transcription factor in B. subtilis. Cell. 1995;83:219–226. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90163-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Camp AH, Losick R. A feeding tube model for activation of a cell-specific transcription factor during sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1014–1024. doi: 10.1101/gad.1781709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cutting S, et al. Forespore-specific transcription of a gene in the signal transduction pathway that governs pro-sigma K processing in Bacillus subtilis. Genes Dev. 1991;5:456–466. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.3.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Setlow P. I will survive: DNA protection in bacterial spores. Trends. Microbiol. 2007;15:172–180. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cowan AE, et al. Lipids in the inner membrane of dormant spores of Bacillus species are largely immobile. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:7733–7738. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306859101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Setlow P. Spores of Bacillus subtilis: their resistance to and killing by radiation, heat and chemicals. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2006;101:514–525. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2005.02736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Warth AD, Strominger JL. Structure of the peptidoglycan of bacterial spores: occurrence of the lactam of muramic acid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1969;64:528–535. doi: 10.1073/pnas.64.2.528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Warth AD, Strominger JL. Structure of the peptidoglycan from spores of Bacillus subtilis. Biochemistry. 1972;11:1389–1396. doi: 10.1021/bi00758a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Paredes-Sabja D, Sarker MR. Germination response of spores of the pathogenic bacterium Clostridium perfringens and Clostridium difficile to cultured human epithelial cells. Anaerobe. 2011;17:78–84. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Setlow P. Spore germination. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2003;6:550–556. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]