Abstract

Objective To investigate the planning of subgroup analyses in protocols of randomised controlled trials and the agreement with corresponding full journal publications.

Design Cohort of protocols of randomised controlled trial and subsequent full journal publications.

Setting Six research ethics committees in Switzerland, Germany, and Canada.

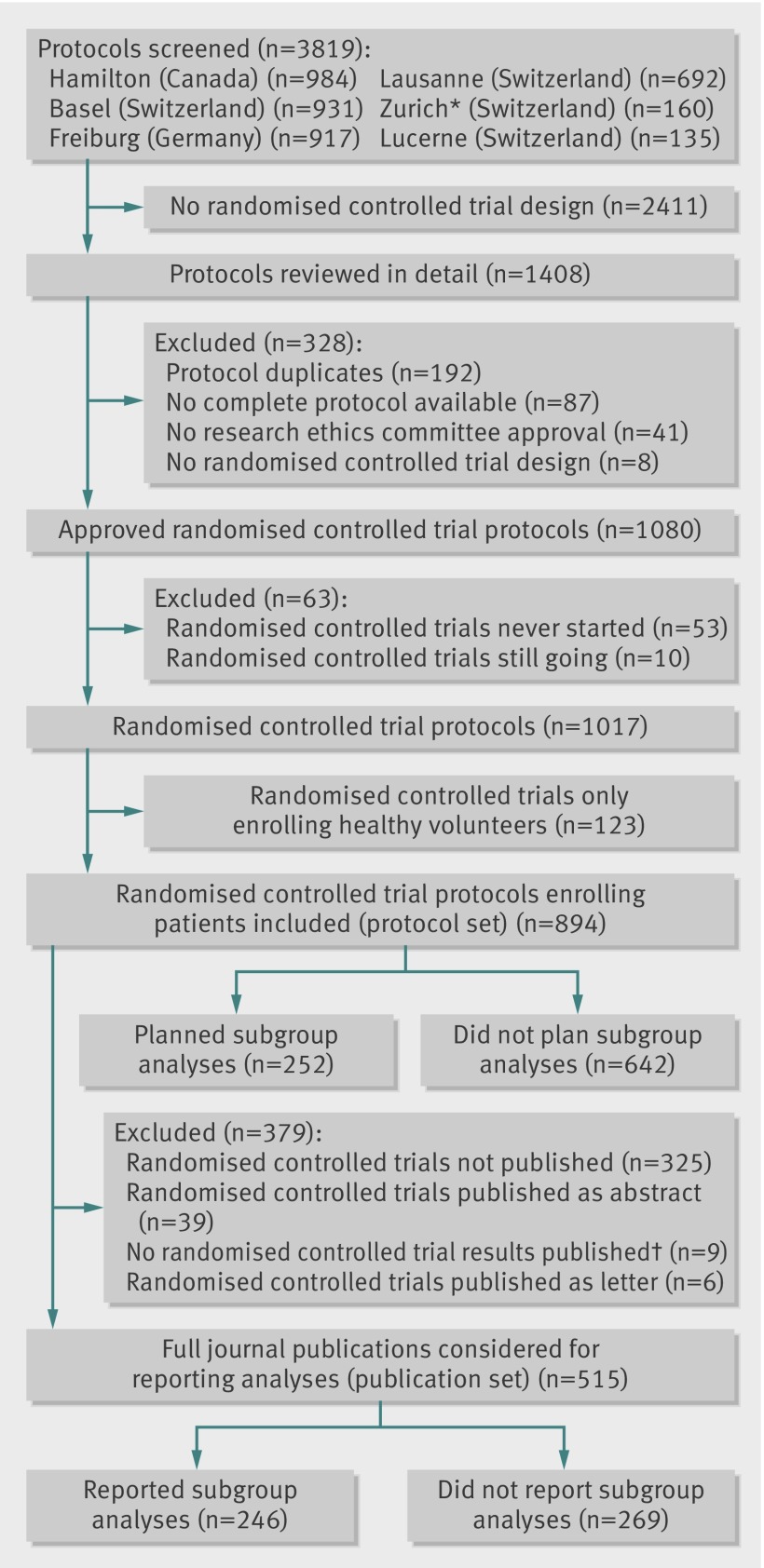

Data sources 894 protocols of randomised controlled trial involving patients approved by participating research ethics committees between 2000 and 2003 and 515 subsequent full journal publications.

Results Of 894 protocols of randomised controlled trials, 252 (28.2%) included one or more planned subgroup analyses. Of those, 17 (6.7%) provided a clear hypothesis for at least one subgroup analysis, 10 (4.0%) anticipated the direction of a subgroup effect, and 87 (34.5%) planned a statistical test for interaction. Industry sponsored trials more often planned subgroup analyses compared with investigator sponsored trials (195/551 (35.4%) v 57/343 (16.6%), P<0.001). Of 515 identified journal publications, 246 (47.8%) reported at least one subgroup analysis. In 81 (32.9%) of the 246 publications reporting subgroup analyses, authors stated that subgroup analyses were prespecified, but this was not supported by 28 (34.6%) corresponding protocols. In 86 publications, authors claimed a subgroup effect, but only 36 (41.9%) corresponding protocols reported a planned subgroup analysis.

Conclusions Subgroup analyses are insufficiently described in the protocols of randomised controlled trials submitted to research ethics committees, and investigators rarely specify the anticipated direction of subgroup effects. More than one third of statements in publications of randomised controlled trials about subgroup prespecification had no documentation in the corresponding protocols. Definitive judgments regarding credibility of claimed subgroup effects are not possible without access to protocols and analysis plans of randomised controlled trials.

Introduction

The primary goal of a randomised controlled trial is to determine the benefits and harms of an intervention. However, trial populations are typically heterogeneous for individual patient characteristics such as age, sex, disease severity, or comorbidity. The question therefore arises as to whether effects of an intervention vary across these patient characteristics. Randomised controlled trials commonly report exploration of such possible subgroup effects1 2 3 4 5 and, if conducted appropriately, such exploration can lead to more targeted clinical recommendations, better informed clinical decision making, and improved patient care.6 7 More often, their results are misleading and can have detrimental consequences.8 9

Because subgroup analyses may be either informative or misleading, healthcare providers and policymakers need criteria to differentiate credible from spurious subgroup effects.8 10

Clinical epidemiologists have suggested criteria8 9 11 12 that allow readers to gauge the likelihood that a subgroup effect is real, on a continuum from highly plausible to extremely unlikely.13 All available criteria include the prespecification of subgroup analyses; some additionally include the anticipated direction of the subgroup effect and the use of a statistical test tackling the likelihood that apparent subgroup effects may be explained by chance.8 9 11 12 13

Judging the credibility of a reported subgroup effect relies on the information provided in published articles, because trial protocols are usually not freely accessible. Little is known about the planning of subgroup analyses in trial protocols and the extent to which they are reported in subsequent publications, and, in particular, which claims of prespecification correspond to these descriptions.14 15 Pioneer work by Chan and colleagues16 suggested large discrepancies between protocols and publications, but their sample was limited to 70 protocols of randomised controlled trials from a single centre.

We investigated subgroup planning and reporting based on protocols of randomised controlled trials from six international centres and the corresponding publications. We focused specifically on the agreement between statements about subgroup prespecification in the publication and corresponding statements in the protocols.

Methods

Study design

We used protocols of randomised controlled trials and corresponding publications included in a retrospective cohort study; the rationale and design have been described elsewhere.17 In short, the study examined protocols approved between 2000 and 2003 by six research ethics committees in Switzerland (Basel, Lucerne, Zurich, and Lausanne), Germany (Freiburg), and Canada (Hamilton). We focused on protocols that had been approved 10 or more years ago to ensure that the number of ongoing randomised controlled trials would be limited.18

Eligibility criteria for protocols and subsequent publications

In the present study, we included protocols regardless of publication status. We excluded those of trials that compared different doses or routes of administering the same drug (early dose finding studies), enrolled only healthy volunteers, were never started, or were still ongoing as of April 2013. We included only full (peer reviewed) journal publications from corresponding protocols of randomised controlled trials; we excluded research letters, letters to the editor, or conference abstracts.

Definitions

We defined a subgroup as a subset of all trial participants with distinct characteristics at randomisation (for example, age, sex, stage of disease). We defined a subgroup analysis as an analysis that explored whether intervention effects (experimental versus control) differed according to these characteristics. For protocols, we considered a subgroup analysis as planned if at least one of the following was reported: any statement in the protocol analogous to the definition above (for example, “intervention effects will be investigated according to patient baseline characteristics”); a stratified analysis (for example, “patients will be stratified according to sex and analysed separately”); a test for interaction (that is, interaction between intervention and patient characteristic); or an investigation of effect modifying factors. For publications, we considered a subgroup analysis as reported if the article included at least one of the following: an effect estimate and an associated confidence interval or a P value for one or more subgroups; a difference between effect estimates of different patient subgroups; investigation of potential effect modifiers, or the results from a test for interaction; or an explicit statement that a subgroup analysis had been undertaken. We assessed protocols for industry sponsorship or investigator sponsorship using the following criteria: the protocol clearly named the sponsor, displayed a company or institution logo prominently, mentioned affiliations of authors of the protocol, included statements about data ownership or publication rights, or included statements about full funding by industry or public funding agencies.18

Data extraction process and search for publications

Twelve investigators trained in clinical research methodology independently extracted data from eligible trial protocols and correspondence between the research ethics committees and the local investigators. Thirty per cent of the extractions were done in duplicate as an initial calibration process to maximise the consistency of data extraction across reviewers. If the files of the ethics committee provided no information about the publication status of a trial, we conducted comprehensive searches of electronic databases to find any associated publications; previous publications present details of the searches and data extraction process.17 18 When randomised controlled trials that mentioned any prespecified subgroup analyses in their publications did not mention any subgroup analyses in corresponding protocols, we searched for additional versions of the protocol published in journals, any available analysis plans (from journals, filed documents at research ethics committees, or websites), and information published in trial registries (clinicaltrials.gov, WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform). Twenty two investigators trained in clinical research methodology extracted data from all corresponding publications, independently and in duplicate; disagreements were resolved by consensus or by third party adjudication. Protocols and corresponding publications were not extracted by the same person.

Information collected about subgroup analyses

We recorded the number of subgroup analyses planned in protocols and reported in publications. We asked the several questions, guided by criteria for the credibility of subgroup analyses.19 For protocols: any subgroup analyses mentioned? If yes: Any clear hypothesis for the planned subgroup analyses mentioned? Any anticipated direction of a subgroup effect mentioned? Any test for interaction mentioned? How many subgroup analyses were planned?

For publications: does the publication report any subgroup analysis? If yes: Does the publication report that subgroup analyses were prespecified? Does the publication report that subgroup analyses were done post hoc? Does the publication provide a rationale for any subgroup analysis? Does the publication report an anticipated direction of any subgroup effect? Does the publication report any separate power calculation for subgroup analyses? Does the publication report any test for interaction? How many subgroup analyses are reported? Does the publication report any claim about a subgroup effect? We considered a subgroup effect as claimed if the investigators explicitly stated in the abstract or discussion/conclusion that the effect of an intervention was different between subgroups or a clear benefit or harm was seen in one or more subgroups.

Statistical analysis

For binary data we summarised results as frequencies and proportions and for continuous data as medians and interquartile ranges. We considered three analysis sets: a dataset based on all protocols (protocol set), a dataset based on corresponding publications (publication set), and a dataset of publications and matched corresponding protocols (publication-protocol set). We prespecified stratification of our descriptive analyses by sponsorship and hypothesised, based on results reported by Sun and colleagues, that industry sponsored trials more often planned subgroup analyses.1 We examined the difference between these proportions using the χ2 test. We used the statistical programmes R version 2.15.3 (www.r-project.org) and STATA version 13.0 (Stata, College Station, TX, USA) for our analyses.

Results

Planning of subgroup analyses—the protocol set

Of 894 eligible protocols of randomised controlled trials involving patients (figure), 252 (28.2%) planned at least one subgroup analysis. Those trials planning subgroup analysis had on average a larger sample size, were more often multicentre trials, and were from the specialty of cardiovascular medicine (table 1). Industry sponsored trials more often planned subgroup analyses than investigator sponsored trials (195/551 (35.4%) v 57/343 (16.6%), P <0.001). Of the 252 protocols planning at least one subgroup analysis, 17 (6.7%) provided a hypothesis and 10 (4.0%) provided an anticipated direction of a potential subgroup effect (table 2).

Study flow of protocols of randomised controlled trials and publications. *Only protocols from two subsidiary research ethics committees responsible for paediatric and surgical randomised controlled trials were screened. †No results from randomised comparison published

Table 1.

Trial characteristics based on protocols. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Characteristics | Subgroup analyses | All trials (n=894) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trials did not plan (n=642) | Trials did plan (n=252) | ||

| Median (interquartile range) target sample size* | 200 (80-460) | 521 (229-1007) | 260 (100-606) |

| Centre status: | |||

| Multicentre | 500 (77.9) | 241 (95.6) | 741 (82.9) |

| Single centre | 139 (21.7) | 10 (4) | 149 (16.7) |

| Unclear | 3 (0.5) | 1 (0.4) | 4 (0.4) |

| Study design: | |||

| Parallel | 592 (92.2) | 244 (96.8) | 836 (93.5) |

| Crossover | 40 (6.2) | 1 (0.4) | 41 (4.6) |

| Factorial | 9 (1.4) | 6 (2.4) | 15 (1.7) |

| Unclear | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.4) | 2 (0.2) |

| Study intention: | |||

| Superiority | 456 (71.0) | 196 (77.8) | 652 (72.9) |

| Non-inferiority | 95 (14.8) | 44 (17.5) | 139 (15.5) |

| Unclear | 91 (14.2) | 12 (4.8) | 103 (11.5) |

| Unit of randomisation: | |||

| Individuals | 629 (98.0) | 250 (99.2) | 879 (98.3) |

| Clusters | 10 (1.6) | 2 (0.8) | 12 (1.3) |

| Body parts | 3 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.3) |

| Sponsorship: | |||

| Investigator | 286 (44.5) | 57 (22.6) | 343 (39.8) |

| Industry | 356 (55.5) | 195 (77.4) | 551 (60.2) |

| Clinical discipline: | |||

| Oncology | 113 (17.6) | 42 (16.7) | 155 (17.3) |

| Cardiovascular | 59 (9.2) | 49 (19.4) | 108 (12.1) |

| Infectious disease | 60 (9.3) | 27 (10.7) | 87 (9.7) |

| Endocrinology | 47 (7.3) | 15 (6.0) | 62 (6.9) |

| Neurology | 37 (5.8) | 24 (9.5) | 61 (6.8) |

| Other | 326 (50.8) | 95 (37.7) | 421 (47.1) |

*Information missing in 12 protocols.

Table 2.

Subgroup credibility criteria based on trial protocols that planned at least one subgroup analysis. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Credibility criteria | Sponsorship | All trials (n=252) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Industry (n=195) | Investigator (n=57) | ||

| Clear hypothesis given?: | |||

| Yes | 7 (3.6) | 10 (17.5) | 17 (6.7) |

| No | 188 (96.4) | 47 (82.5) | 235 (93.3) |

| Direction of anticipated effect given?: | |||

| Yes | 3 (1.5) | 7 (12.3) | 10 (4.0) |

| No | 192 (98.5) | 50 (87.7) | 242 (96.0) |

| Interaction test planned?: | |||

| Yes | 69 (35.4) | 18 (31.6) | 87 (34.5) |

| No | 126 (64.6) | 39 (68.4) | 165 (65.5) |

| No of planned subgroup analyses: | |||

| Median (interquartile range) | 3 (1, 6) | 3 (1, 6) | 3 (1, 4) |

| Not reported (No of studies) | 18 (9.2) | 12 (21.1) | 30 (11.9) |

Reporting of subgroup analyses—the publication set

For 515 protocols we identified corresponding full journal publications (publication set, figure). Of those, 246 (47.8%) publications reported subgroup analyses. These trials were, on average, larger and more often published in high impact journals than published randomised controlled trials without subgroup reporting (see supplementary table 1). Table 3 summarises the reporting of subgroup credibility criteria and characteristics of subgroup analyses in these full journal publications. Similar to the protocol set, subgroup hypotheses or anticipated directions of subgroup effects were rarely provided. Of 86 publications claiming a subgroup effect, 39 (45.3%) reported the use of an interaction test, 9 (10.5%) provided a subgroup hypothesis, and 5 (5.8%) provided an anticipated direction of effect.

Table 3.

Reported subgroup credibility criteria and interpretation of subgroup analyses based on publications that reported at least one subgroup analysis. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Reported credibility criteria and interpretation | Sponsorship | All trials (n=246) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Industry (n=160) | Investigator (n=86) | ||

| Prespecification of subgroup analyses reported in publication?: | |||

| Yes | 58 (36.2) | 23 (26.7) | 81 (32.9) |

| No | 102 (63.7) | 63 (73.3) | 165 (67.1) |

| Post hoc subgroup analyses reported in publication?: | |||

| Yes | 27 (16.9) | 21 (24.4) | 48 (19.5) |

| No | 133 (83.1) | 65 (75.6) | 198 (80.5) |

| Clear hypothesis given?: | |||

| Yes | 11 (6.9) | 10 (11.6) | 21 (8.5) |

| No | 149 (93.1) | 76 (88.4) | 225 (91.5) |

| Direction of anticipated effect given?: | |||

| Yes | 5 (3.1) | 6 (7.0) | 11 (4.5) |

| No | 155 (96.9) | 80 (93.0) | 235 (95.5) |

| Power calculation for subgroup analyses mentioned in publication?: | |||

| Yes | 3 (1.9) | 3 (3.5) | 6 (2.4) |

| No | 157 (98.1) | 83 (96.5) | 240 (97.6) |

| Test for interaction reported?: | |||

| Yes | 60 (37.5) | 36 (41.9) | 96 (39.0) |

| No | 100 (62.5) | 50 (58.1) | 150 (61.0) |

| No of reported subgroup analyses: | |||

| Median (interquartile range) | 4 (1, 8) | 4 (2, 8) | 4 (2, 8) |

| Not reported | 6 (3.8) | 2 (1.3) | 8 (3.3) |

| Any claim of subgroup effect reported?: | |||

| Yes | 57 (35.6) | 29 (33.7) | 86 (35.0) |

| No | 103 (64.4) | 57 (66.3) | 160 (65.0) |

Agreement between subgroup reporting in publications and corresponding protocols—the publication-protocol set

Of 515 publications of randomised controlled trials, 132 (25.6%) reported the conduct of subgroup analyses that were not mentioned in the corresponding protocols; 64 (12.4%) publications did not report subgroup analyses that were planned in the corresponding protocols.

Of those 246 publications that reported subgroup analyses, overall 114 (46.3%) corresponding protocols planned at least one subgroup analysis (for industry sponsored trials 86/160 (53.8%), for investigator sponsored trials 28/86 (32.6%)). In those 114 trials, the reported number of subgroup analyses matched the planned number in the protocol in 11 (9.6%) instances. Table 4 summarises the agreements of subgroup credibility criteria for those 246 trials reporting at least one subgroup analysis. In 81 of 246 (32.9%) publications reporting subgroups, authors stated for at least one of their reported subgroup analyses that it was prespecified, but 28 (34.6%) corresponding protocols had not mentioned any planned subgroup analysis. For 12 of these 28 randomised controlled trials, the authors mentioned a separate analysis plan in the publication or the protocol without mentioning subgroup analyses. However, these analysis plans were not made available to readers. We found registered information for 9 (32.1%) of the 28 randomised controlled trials but without any evidence of planned subgroup analyses. Of the 86 publications claiming a subgroup effect, 36 (41.8%) corresponding protocols reported a planned subgroup analysis.

Table 4.

Agreement of planning and reporting of subgroup credibility criteria based on those 246 publications reporting at least one subgroup analysis. Numbers are protocols/publications reporting or not reporting subgroup credibility criteria (percentages)

| Planned in protocol | Reported in publication | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Industry sponsorship (n=160) | Investigator sponsorship (n=86) | All trials (n=246) | ||||

| Subgroup hypothesis: | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| No | 143 (89.4) | 11 (6.9) | 73 (84.9) | 8 (9.3) | 216 (87.8) | 19 (7.7) |

| Yes | 6 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (3.5) | 2 (2.3) | 9 (3.7) | 2 (0.8) |

| Direction of effect: | ||||||

| No | 153 (95.6) | 5 (3.1) | 78 (90.7) | 4 (4.7) | 231 (94.0) | 9 (3.7) |

| Yes | 2 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.3) | 2 (2.3) | 4 (1.6) | 2 (0.8) |

| Interaction test: | ||||||

| No | 80 (50.0) | 46 (28.8) | 48 (55.8) | 26 (30.2) | 128 (52.0) | 72 (29.3) |

| Yes | 20 (12.5) | 14 (8.8) | 2 (2.3) | 10 (11.6) | 22 (8.9) | 24 (9.8) |

Discussion

Our study provides empirical evidence documenting the planning and reporting of subgroup analyses in a sample of 894 randomised controlled trials involving patients, which were approved by six research ethics committees in three countries. About half of the published trials reported the conduct of subgroup analyses, of which only 46% had mentioned any planned subgroup analyses in the corresponding protocols. Industry sponsored randomised controlled trials planned subgroup analyses more often than investigator sponsored trials, but still only half of industry sponsored trials reporting results for subgroups explicitly stated such planned analyses in the protocol. In trials with subgroup analyses mentioned in both the protocol and the publication, the number of subgroup analyses reported in publications matched the number in protocols in only 10%. Investigators rarely provided a rationale for or indicated the anticipated direction of potential subgroup effects in either protocols or reports of randomised controlled trials. Of the journal publications stating that at least one subgroup analysis was preplanned, a third failed to mention any subgroup analysis in the corresponding protocol.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The data for the present study were collected as part of a large international cohort involving six research ethics committees that allowed full access to trial protocols and filed correspondence.17 18 As outlined previously,20 unrestricted access is absolutely necessary (but not always granted) to maintain scientific rigor: asking trialists and sponsors for permission to access their protocols would very likely introduce bias, because those with substandard reporting practices may be less likely to allow additional scrutiny. As further strengths we involved only trained methodologists in data abstraction and performed all data extractions from identified publications independently and in duplicate. Finally, our sample included randomised controlled trials from various disciplines of clinical medicine, thus enhancing generalisability of our results.

Our study has limitations. Firstly, we did not have access to statistical analysis plans that may have had prespecified subgroup analyses not mentioned in the protocol. However, we exhaustively checked all available evidence (published protocols, trial websites, filed documents at research ethics committees, trial registries) for prespecification of subgroup analyses. Nevertheless, our results fail to take into account changes in the protocol that occurred before examination of the data and that were not recorded in any of the above documents. Secondly, we did not systematically extract information from protocols about separate power calculations for subgroup analysis. However, since only 4% of protocols that planned subgroup analysis provided an anticipated direction of a subgroup effect, appropriate power calculations (additionally including an estimate for the magnitude of the subgroup effect) were likely to be even less common. Only 2.4% of publications that mentioned a subgroup analysis reported a corresponding power calculation. Thirdly, we used a convenience sample of six research ethics committees, which were, to our knowledge, not in any way particular. Still, we cannot say whether they are representative of other research ethics committees in their own or other countries. Fourthly, owing to limited resources we used single data extraction for 70% of protocols, thereby potentially increasing errors in extraction. However, we used pre-piloted extraction forms with detailed written instructions, conducted formal calibration exercises with all data extractors, and checked extractions from a random sample of protocols at several points during the process. Agreement was good, with no more than two discrepancies in 30 extracted key variables.18 Fifthly, instead of a formal protocol for the current substudy, we previously published a protocol only of the overall project, mentioning this study without details.17 Therefore we limited hypothesis testing in this study to one prespecified subgroup analysis and we make our data extraction forms reflecting all collected variables available to readers on request. Sixthly, included protocols were approved 10-13 years ago; the planning of subgroup analyses in protocols may have improved since that time.

Comparison with other studies

In an earlier systematic review of 469 randomised controlled trials19 we found that 44% of full text publications reported subgroup analyses, which is consistent with our present finding of 48%. In the previous study, we found that most claimed subgroup effects in randomised controlled trials had low credibility and prespecification was seldom reported. The present study not only confirms this finding, but reveals that, often, the claim of prespecification of subgroups in publications is not supported by the corresponding protocols.

Many previous empirical studies mentioned that justification of subgroup analysis and the statistical methods used were rarely reported.2 3 4 5 14 16 21 22 Of those, only some smaller studies compared grant applications22 or protocols of randomised controlled trials14 16 with publications for information about subgroup analyses and identified considerable discrepancies: Boonacker and colleagues noted that only 11 of 47 (23%) grant proposals for randomised controlled trials were in agreement with publications22; Chan and colleagues found that 25 of 70 (36%) randomised controlled trials reported subgroup analyses in the protocol or in the publication and that there were discrepancies between the two documents for all 25 randomised controlled trials16; and Al-Marzouki and colleagues documented that only 8 of 19 (42%) protocols of randomised controlled trials not mentioning subgroup analyses and 7 of 18 (39%) protocols planning subgroup analyses were consistent with corresponding publications.14 In our sample, numbers of subgroup analyses in protocols and publications were identical in less than 5% (11/246) of randomised controlled trials reporting subgroups. Only Chan and colleagues examined whether reported prespecification of subgroup analyses in publications (7/20, 35%) was supported by planned subgroup analyses in protocols. Four of 7 (57%) randomised controlled trials with reported prespecifications lacked evidence of prespecification in the corresponding protocols.16

Implications for reporting and interpreting subgroup analyses

Current recommendations aim to help readers when judging the credibility of subgroup analyses based on information provided in the publication.9 13 Empirical evidence from comparisons of protocols of randomised controlled trials and publications has been limited.14 16 Our results challenge a key criterion of all previous recommendations—that is, the a priori specification of the subgroup analysis. Given that in one out of three studies’ protocols do not corroborate reported claims of prespecification of subgroup analyses, gains in credibility from this criterion are limited.

The following steps could help to improve the trustworthiness of reported subgroup analyses. Firstly, planned subgroup analyses should be documented in trial registries. To date, however, possibilities to enter such information in trial registries are insufficiently developed. For example, there is a non-mandatory “Group/Cohort” field in the registry clinicaltrials.gov that could be used for subgroup prespecification, but the corresponding data element description remains unclear.23 The WHO International Clinical Trials Registry platform24 and the registry Controlled Clinical Trials25 currently do not enable entry of information about subgroups. Secondly, clinical investigators should adhere to guidelines for protocols of randomised controlled trials such as the SPIRIT statement.26 27 Research ethics committees and other review boards should promote the use of such guidance documents.

Thirdly, journals should request access to protocols or statistical analysis plans for their review process and make these documents accessible to readers. In addition, journals could enforce adherence to guidelines for the reporting of randomised controlled trials (for example, the CONSORT statement)28 to reduce the prevalent incomplete reporting of subgroup analyses. Unless a reliable source such as a comprehensive trial protocol is available, readers of trial reports should consider statements about subgroup prespecifications with scepticism. When judging the credibility of a subgroup effect, readers may look for similar studies instead and consider whether subgroup findings are consistent.

Conclusion

Large discrepancies exist between the planning and reporting of subgroup analyses in randomised controlled trials. Published statements about subgroup prespecification were not supported by study protocols in about a third of cases. Our results highlight the importance of enhancing the completeness and accuracy of protocols of randomised controlled trials and their accessibility to journal editors, reviewers, and readers.

What is already known on this topic

Claims of subgroup effects in randomised trials have little credibility

Prespecification of subgroup analyses is an important criterion to assess the credibility of subgroup effects in randomised trials

What this study adds

Large discrepancies exist between planning of subgroup analyses in protocols and their reporting in publications of randomised trials

Statements about subgroup prespecification in journal publications are of low credibility if access to trial protocols and analysis plans are not provided

Protocol and registry information of randomised trials should include a statement whether subgroup analyses are planned or not, and if so, should specify them

We thank the presidents and staff of participating research ethics committees from Switzerland (Basel, Lausanne, Zurich, Lucerne), Germany (Freiburg), and Canada (Hamilton) for their continuous support and cooperation.

The following are members of the DISCO study group: Benjamin Kasenda (Basel, Switzerland), Stefan Schandelmaier (Basel, Switzerland), Xin Sun (Hamilton, Canada; Chengdu, China), Erik von Elm (Lausanne, Switzerland), John You (Hamilton, Canada), Anette Blümle (Freiburg, German), Yuki Tomonaga (Zurich, Switzerland), Ramon Saccilotto (Basel, Switzerland), Alain Amstutz (Basel Switzerland), Theresa Bengough (Lausanne, Switzerland), Joerg J Meerpohl (Freiburg, Germany), Mihaela Stegert (Basel, Switzerland), Kelechi K Olu (Basel, Switzerland), Kari A O Tikkinen (Hamilton, Canada; Helsinki, Finland), Ignacio Neumann (Hamilton, Canada; Santiago, Chile), Alonso Carrasco-Labra (Hamilton, Canada; Santiago, Chile), Markus Faulhaber (Hamilton, Canada), Sohail M Mulla (Hamilton, Canada), Dominik Mertz (Hamilton, Canada), Elie A Akl (Hamilton, Canada; Beirut, Lebabon; Buffalo, NY), Dirk Bassler (Zurich, Switzerland), Jason W Busse (Hamilton, Canada), Ignacio Ferreira-González (Barcelona, Spain), Francois Lamontagne (Sherbrooke, Canada), Alain Nordmann (Basel, Switzerland), Viktoria Gloy (Basel and Bern, Switzerland), Heike Raatz (Basel, Switzerland), Lorenzo Moja (Milan, Italy), Rachel Rosenthal (Basel, Switzerland), Shanil Ebrahim (Hamilton, Canada, Stanford, CA), Per O Vandvik (Oppland, Norway), Bradley C Johnston (Hamilton and Toronto, Canada), Martin A Walter (Bern, Switzerland), Bernard Burnand (Lausanne, Switzerland), Matthias Schwenkglenks (Zurich, Switzerland), Lars G Hemkens (Basel, Switzerland), Heiner C Bucher (Basel, Switzerland), Gordon H Guyatt (Hamilton, Canada), Matthias Briel (Basel, Switzerland; Hamilton, Canada)

Contributors: BK, EvE, and MB designed the study, collected data, interpreted the results, and wrote the manuscript. BK and SS managed the database and conducted all analyses, which were checked by MB. SS, JY, AB, YK, RS, AA, TB, JJM, MS, KKO, KAOT, IN, AC, MF, SMM, DM, EAA, DB, JWB, IF, FL, AN, VG, HR, LM, RR, SE, XS, POV, BCJ, MAW, MS, and LGH contributed to the data collection. BB, HCB, and GHG provided methodological and logistical support. All authors critically revised the manuscript and approved the final version before submission. BK, SS, EvE, and MB are guarantors.

Funding: This study was funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant 320030_133540/1) and the German Research Foundation (grant EL 544/1-2). MB, AN, VG, HR, LGH, and HCB were supported by Santésuisse and the Gottfried and Julia Bangerter-Rhyner-Foundation. XS was supported by a young investigators award (2013SCU04A37) from Sichuan University, China. During study preparation, EvE was supported by the Brocher Foundation. JWB was funded by a new investigator award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and Canadian Chiropractic Research Foundation. DM was a recipient of a research early career award from Hamilton Health Sciences Foundation (Jack Hirsh Fellowship). KAOT was funded by unrestricted grants from the Finnish Cultural Foundation, Finnish Medical Foundation, Jane and Aatos Erkko Foundation, and Sigrid Jusélius Foundation. JY was supported by a research early career award from Hamilton Health Sciences.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: study funding by the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant 320030_133540/1) and the German Research Foundation (grant EL 544/1-2), no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years, and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the participating research ethics committees, or if no ethical approval was required this was explicitly stated.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Transparency: The lead author (the manuscript’s guarantor) affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Cite this as: BMJ 2014;349:g4539

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the authors

Table showing characteristics of trials as reported in published journal articles

References

- 1.Sun X, Briel M, Busse JW, You JJ, Akl EA, Mejza F, et al. The influence of study characteristics on reporting of subgroup analyses in randomised controlled trials: systematic review. BMJ 2011;342:d1569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hernandez AV, Boersma E, Murray GD, Habbema JD, Steyerberg EW. Subgroup analyses in therapeutic cardiovascular clinical trials: are most of them misleading? Am Heart J 2006;151:257-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang R, Lagakos SW, Ware JH, Hunter DJ, Drazen JM. Statistics in medicine--reporting of subgroup analyses in clinical trials. N Engl J Med 2007;357:2189-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gabler NB, Duan N, Liao D, Elmore JG, Ganiats TG, Kravitz RL. Dealing with heterogeneity of treatment effects: is the literature up to the challenge? Trials 2009;10:43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Assmann SF, Pocock SJ, Enos LE, Kasten LE. Subgroup analysis and other (mis)uses of baseline data in clinical trials. Lancet 2000;355:1064-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Szczech LA, Berlin JA, Feldman HI. The effect of antilymphocyte induction therapy on renal allograft survival. A meta-analysis of individual patient-level data. Anti-Lymphocyte Antibody Induction Therapy Study Group. Ann Intern Med 1998;128:817-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rothwell PM, Eliasziw M, Gutnikov SA, Fox AJ, Taylor DW, Mayberg MR, et al. Analysis of pooled data from the randomised controlled trials of endarterectomy for symptomatic carotid stenosis. Lancet 2003;361:107-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oxman AD, Guyatt GH. A consumer’s guide to subgroup analyses. Ann Intern Med 1992;116:78-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun X, Ioannidis JP, Agoritsas T, Alba AC, Guyatt G. How to use a subgroup analysis: users’ guide to the medical literature. JAMA 2014;311:405-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pocock SJ, Assmann SE, Enos LE, Kasten LE. Subgroup analysis, covariate adjustment and baseline comparisons in clinical trial reporting: current practice and problems. Stat Med 2002;21:2917-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rothwell PM. Treating individuals 2. Subgroup analysis in randomised controlled trials: importance, indications, and interpretation. Lancet 2005;365:176-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yusuf S, Wittes J, Probstfield J, Tyroler HA. Analysis and interpretation of treatment effects in subgroups of patients in randomized clinical trials. JAMA 1991; 266: 93-8. [PubMed]

- 13.Sun X, Briel M, Walter SD, Guyatt GH. Is a subgroup effect believable? Updating criteria to evaluate the credibility of subgroup analyses. BMJ 2010;340:c117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Al-Marzouki S, Roberts I, Evans S, Marshall T. Selective reporting in clinical trials: analysis of trial protocols accepted by The Lancet. Lancet 2008;372:201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chan AW. Bias, spin, and misreporting: time for full access to trial protocols and results. PLoS Med 2008;5:e230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chan AW, Hrobjartsson A, Jorgensen KJ, Gotzsche PC, Altman DG. Discrepancies in sample size calculations and data analyses reported in randomised trials: comparison of publications with protocols. BMJ 2008;337:a2299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kasenda B, von Elm EB, You J, Blumle A, Tomonaga Y, Saccilotto R, et al. Learning from Failure - Rationale and Design for a Study about Discontinuation of Randomized Trials (DISCO study). BMC Med Res Methodol 2012;12:131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kasenda B, von Elm E, You J, Blumle A, Tomonaga Y, Saccilotto R, et al. Prevalence, characteristics, and publication of discontinued randomized trials. JAMA 2014;311:1045-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun X, Briel M, Busse JW, You JJ, Akl EA, Mejza F, et al. Credibility of claims of subgroup effects in randomised controlled trials: systematic review. BMJ 2012; 344: e1553. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Chan AW, Upshur R, Singh JA, Ghersi D, Chapuis F, Altman DG. Research protocols: waiving confidentiality for the greater good. BMJ 2006;332:1086-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bhandari M, Devereaux PJ, Li P, Mah D, Lim K, Schunemann HJ, et al. Misuse of baseline comparison tests and subgroup analyses in surgical trials. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2006;447:247-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boonacker CW, Hoes AW, van Liere-Visser K, Schilder AG, Rovers MM. A comparison of subgroup analyses in grant applications and publications. Am J Epidemiol 2011;174:219-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.ClinicalTrials.gov. Protocol Data Element Definitions (DRAFT). 2013. http://prsinfo.clinicaltrials.gov/definitions.html (accessed March 2014).

- 24.ICTRP. Search Portal. 2014. http://www.who.int/ictrp/search/en/ (accessed March 2014).

- 25.ISRCTN. Data Set. 2012. http://www.controlled-trials.com/isrctn/isrctn_dataset (accessed March 2014).

- 26.Chan AW, Tetzlaff JM, Altman DG, Laupacis A, Gotzsche PC, Krleza-Jeric K, et al. SPIRIT 2013 statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:200-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chan AW, Tetzlaff JM, Gotzsche PC, Altman DG, Mann H, Berlin JA, et al. SPIRIT 2013 explanation and elaboration: guidance for protocols of clinical trials. BMJ 2013;346:e7586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D, Group C. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 2010;340:c332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table showing characteristics of trials as reported in published journal articles