Abstract

We recently evaluated the relationship between abiotic environmental stresses and lutein biosynthesis in the green microalga Dunaliella salina and suggested a rational design of stress-driven adaptive evolution experiments for carotenoids production in microalgae. Here, we summarize our recent findings regarding the biotechnological production of carotenoids from microalgae and outline emerging technology in this field. Carotenoid metabolic pathways are characterized in several representative algal species as they pave the way for biotechnology development. The adaptive evolution strategy is highlighted in connection with enhanced growth rate and carotenoid metabolism. In addition, available genetic modification tools are described, with emphasis on model species. A brief discussion on the role of lights as limiting factors in carotenoid production in microalgae is also included. Overall, our analysis suggests that light-driven metabolism and the photosynthetic efficiency of microalgae in photobioreactors are the main bottlenecks in enhancing biotechnological potential of carotenoid production from microalgae.

Keywords: microalgae, carotenoid metabolism, environmental stress, Dunaliella salina, adaptive laboratory evolution, LED-based photobioreactors

Global climate change and environmental issues provide an impetus for a transition to a bio-based economy with a low carbon footprint. Microalgae have been considered as promising feedstocks for applications in food and feed production, bioactive pharmaceuticals, and biofuels,1-3 as they possess several unique properties. Microalgae as primary producers are a major part of phytoplankton community, found in almost all marine and fresh water ecosystems. They are photosynthetic eukaryotes capable of fixing CO2 into biomass with a higher efficiency of photosynthesis than vascular plants.4 They are also highly diverse; for example, diatoms are evolutionarily different from green algae.5 Many species of microalgae are easy to cultivate with inexpensive media and they don’t compete directly with agricultural crops for water or land. There are also genetic modification tools6 available that make it possible to engineer microalgae for the efficient production of desired products. In addition, microalgae are a rich source of natural value-added products, such as carotenoids and unsaturated fatty acids. There is a high demand for naturally synthesized carotenoids such as β-carotene and lutein in global markets.7 However, the productivity of carotenoids in microalgae has historically been low, and the economic viability of algal biotechnology is limited by processing costs and photosynthetic efficiency, as well as by productivity in algal cultures.

We recently evaluated the relationship between abiotic environmental stresses and lutein biosynthesis in the green microalga Dunaliella salina.8 That study presented an assessment of how different environmental stressors and their interactions influenced lutein accumulation. A systems analysis of stress conditions revealed that the adaptability of Dunaliella cells varied significantly in response to different environmental changes. Therefore, a guideline was proposed for stress-driven adaptive evolution experiments.8 Rational design of adaptive evolution experiments may be an effective approach for optimizing the production of carotenoids. However, it is also important to understand carotenoid metabolism and characterize the relevant rate-limiting steps prior to the rational design. The characterization of metabolic pathways can also pave the way for further design of algal cell factories through metabolic engineering approaches. The current study summarizes the major pathways of carotenoid metabolism in several representative species of green algae and diatoms, i.e., Chlorella vulgaris, D. salina, Haematococcus pluvialis, and Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Recent efforts in genetic engineering, as well as adaptive evolution for overproduction of carotenoids, are briefly introduced and the biotechnological implications of these studies are discussed.

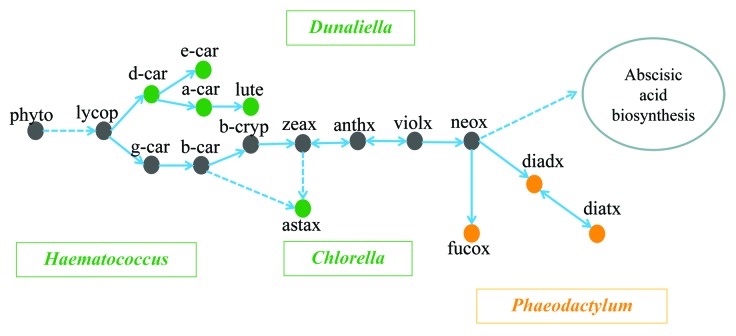

Carotenoids play an essential role in the light harvesting complex of microalgae and higher plants. Carotenoid biosynthesis is complex, as it is coordinated with the biogenesis of chlorophylls, the photosynthetic apparatus and electron transport.9,10 The first step in the carotenoid biosynthetic pathway is the condensation of two molecules of geranylgeranyl diphosphate (GGPP) to produce C40 phytoene, a common precursor of other carotenoids in microalgae.11 The metabolic pathways of carotenoids in green algae and diatoms are shown in Figure 1. Major carotenoids are illustrated in several representative microalgae. All of these microalgae are either model species or industrially important. The green algae Chlorella, Dunaliella, and Haematococcus all belong to the phylum Chlorophyta, while the diatom Phaeodactylum is in the phylum Heterokontophyta.12 Some carotenoids, such as diadinoxanthin, diatoxanthin, and fucoxanthin, are only present in diatoms, while others, such as δ-carotene, ε-carotene, α-carotene, lutein, and astaxanthin, are only produced in green algae (Fig. 1). Some algal species may accumulate large amounts of specialty carotenoids. For instance, D. salina can overproduce β-carotene and lutein under stress conditions and H. pluvialis is a good producer of astaxanthin.13 As microalgae are able to synthesize very diverse carotenoid species, characterization of metabolic pathways is an important step prior to engineering algal strains for industrial applications.

Figure 1. Overview of the carotenoid biosynthetic pathway in green microalgae and diatoms. Arrows indicate directions of the reactions. Dashed lines and solid lines represent multiple and single steps of enzymatic reactions, respectively. Green and orange dots refer to carotenoid species present only in green algae and only in diatoms, respectively, while gray dots show carotenoids which are present in both green algae and diatoms. Names of green microalgae are shown in green boxes, while the diatom Phaeodactylum is shown in an orange box. Abbreviations: phyto, phytoene; lycop, lycopene; d-car, δ-carotene; e-car, ε-carotene; a-car, α-carotene; lute, lutein; g-car, γ-carotene; b-car, β-carotene; b-cryp, β-cryptoxanthin; zeax, zeaxanthin; anthx, antheraxanthin; violx, violaxanthin; neox, neoxanthin; astax, astaxanthin; diadx, diadinoxanthin; diatx, diatoxanthin; fucox, fucoxanthin.

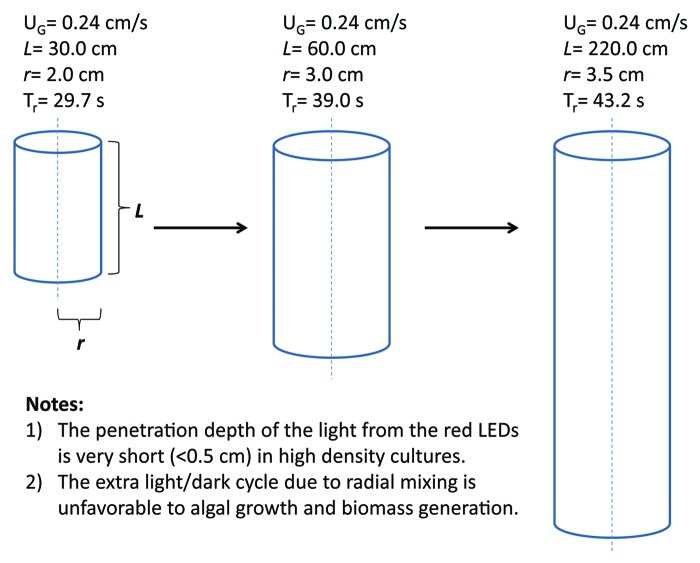

LED-based photobioreactor (PBR) systems19 can be used to cultivate algae intensively at high densities. However, photolimitation due to mutual shading is ubiquitous in all sizes of PBRs during scale-up. The radial mixing time26 calculated for a bubble column PBR19 with a radius of 2.0 cm and a length of 30.0 cm can be as long as 30 s, and increases as PBR size increases (Fig. 2). The additional light-dark cycle caused by radial mixing results in limited exposure of algae to lights and reduced growth rate. In the meantime, oversaturated light intensity provided on the surface of PBRs may lead to photodamage to algal cells which move into these areas. Photolimitation and photoinhibition, which exist simultaneously in tubular PBRs, largely limit the biomass yield as well as photosynthetic efficiency in algal culture, thereby reducing the overall productivity of desired carotenoids. Efforts are needed to optimize the light harvesting system of microalgae, in order to improve the biomass yields as well as photosynthetic efficiencies.

Figure 2. Illustration of the effect of bubble column PBR size on radial mixing times. Tr represents radial mixing time, calculated according to Rubio et al.26 UG refers to the superficial velocity of input gases. L and r are the length and the radius of the PBR, respectively.

It is well known that organisms adapt to environmental changes through the fixation of mutations that enhance reproductive success.14 Long-term adaptation on an unusual and poor carbon source for bacteria would select for mutants with optimal biomass yields.15,16 Adaptive laboratory evolution (ALE) has been widely utilized as a tool for developing new biological and phenotypic functions and exploring strain improvement in synthetic biology for bacteria.17 Adaptation studies on Dunaliella date back to the 1970s;18 however, adaptive evolution is still a novel approach for improving strain performance in algal biotechnology, as evolutionary dynamics is more complex in photosynthetic eukaryotes than in bacteria. With the aid of LED technology, the effects of light quality (e.g., red light with or without blue light) can be addressed under defined LED illumination. Rational design of adaptive evolution experiments can therefore be performed under light stress conditions. In a previous study, an adaptive evolution approach was developed to evolve a strain of the microalga C. vulgaris with an improved growth rate and biomass yield under light stress conditions.19 We also found that light quality was critical for D. salina in response to light stress, and the application of adaptive evolution yielded strains with increased accumulation of carotenoids under combined blue and red lights.20 The photosynthetic efficiencies and biomass productivities for three different algal species, including those discussed above, are summarized in Table 1. It can be seen that improved biomass productivity, biomass yield, and photosynthetic efficiency was achieved for both D. salina and C. vulgaris by using ALE and by adjusting the amount of illumination and/or the wavelengths of incident LED light. The data in Table 2 show that the light quality, i.e., the presence of blue light, helped to enhance the accumulation of major carotenoids in microalgae, specifically, lutein and β-carotene in D. salina after ALE and fucoxanthin in P. tricornutum prior to ALE. It is hypothesized that adaptive evolution will also improve the growth performance of P. tricornutum, as was observed for D. salina and C. vulgaris (this study is ongoing). It has been reported elsewhere that growth performance, as well as lipid productivity, of the green microalga Chlamydomonas reinhardtti was also enhanced by adaptive evolution.21 These findings demonstrate that adaptive evolution can be an effective strategy for selecting economically valuable traits in microalgae. Understanding how laboratory selection drives algal evolution is a key challenge in evolutionary engineering. Further study should be undertaken in order to gain a better understanding of adaptation mechanisms and the interactions between genetic and environmental variables. Genome resequencing and comparative genomics are needed to decipher the genetically inheritable adaptation of algal species to specific environmental settings for rapid selection and evolution.

Table 1. Photosynthetic efficiencies of microalgae in LED-based PBRs.

| Algae species | LED illumination (µE/m2/s) |

Biomass productivity (gDCW/L/day) | Biomass yield (g/E) | Photosynthetic efficiency* (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. tricornutum# | Prior to ALE | 204 (100% red) | 0.32 ± 0.02 | 0.18 ± 0.01 | 2.0 |

| 204 (50% red and 50% blue) | 0.64 ± 0.02 | 0.36 ± 0.01 | 3.3 | ||

| D. salina 20 | After ALE | 170 (100% red) | 0.40 ± 0.01 0.22 ± 0.01 |

0.27 ± 0.01 0.15 ± 0.01 |

3.0 1.7 |

| Prior to ALE | |||||

| After ALE | 170 (75% red and 25% blue) | 0.48 ± 0.02 0.40 ± 0.01 |

0.33 ± 0.01 0.27 ± 0.01 |

3.3 2.7 |

|

| Prior to ALE | |||||

| C. vulgaris 19 | After ALE | 300 (100% red) | 2.11 ± 0.13 | 0.81 ± 0.05 | 9.0 |

| Prior to ALE | 255 (100% red) | 0.71 ± 0.05 | 0.32 ± 0.02 | 3.6 | |

*A biomass combustion energy of 20.15 kJ is assumed; # model species (CCAP 1055/1) in this work.

Table 2. Quantification of major carotenoids in microalgae under different light conditions.

| Algae species | LED illumination (µE/m2/s) |

Carotenoid content in cells (mg/g DCW) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lutein | β-Carotene | Fucoxanthin | ||

| P. tricornutum# | 204 (100% red) | Not applicable | 2.3 ± 0.4 | 8.0 ± 1.6 |

| 204 (50% red and 50% blue) | Not applicable | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 12.2 ± 1.1 | |

| D. salina 20 | 170 (100% red) | 4.0 ± 0.4 | 2.6 ± 0.2 | Not applicable |

| 170 (75% red and 25% blue)* | 7.9 ± 0.7 | 9.5 ± 0.5 | Not applicable | |

# Model species (CCAP 1055/1) in this work, prior to ALE; * the strain after ALE was evaluated under the light conditions.

Metabolic engineering and genetic engineering are also likely to play an important role in developing microalgae for improved productivity of a desired product through the direct manipulation of metabolic pathways. Genetic modification tools have been developed for some algal species. A glass bead transformation system for D. salina has been established and a duplicated carbonic anhydrase 1 promoter has been used for stable nuclear transformation.22 An RNA interference approach has also been applied to inhibit gene expression in D. salina.23 Molecular biology tools for gene manipulation have also been developed in diatoms.24 Microprojectile bombardment and electroporation methods have been applied successfully to introduce foreign DNA into Phaeodactylum cells.24,25 The shuttle vector pPha-NR with inducible nitrate reductase promoter system (GenBank: JN180663) has been constructed for controllable expression of foreign genes. Although the tools for algal transformation are still limited and high efficiency methods would be desirable, it is feasible to engineer certain algal species of interest for valuable carotenoid production in industry. The application of metabolic engineering and genetic engineering has shown promise in producing carotenoids in microalgae,27 as well as in yeast.28 However, due to the complexity of carotenoid metabolic pathways, carotenoid yields in eukaryotic cells with DNA recombination technology have been much lower than the yields achieved by other methods. For example, optimizing cultivation systems and developing an appropriate two-stage culture mode,29,30 as shown in Table 3, achieved higher production yields than the DNA recombination method. In the meantime, it is likely that algal species have been evolved to accumulate certain carotenoids during natural evolution.20 It is recommended that future research focuses on the combination of new metabolic engineering strategies, strain selection, bioreactor design and cultivation optimization to achieve microalgal production of carotenoids at low costs, high yields and in an environmentally friendly manner.

Table 3. Production of carotenoids with and without genetically modified microorganisms.

| Strain species | Cultivation method | Genetic engineering | Carotenoid species | Content in cells (mg/gDCW) | Productivity (mg/L/day) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. zofingiensis 27 | Two-stage culture | Yes | Astaxanthin | 4.6 | ND |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae 28 | Batch culture | Yes | β-Carotene | 5.9 | ND |

| D. bardawil 29 | Two-stage culture | No | β-Carotene | 80 | ND |

| H. pluvialis 30 | Two-stage culture | No | Astaxanthin | 40 | 11.5 |

ND, not determined.

In summary, engineering microalgae for carotenoid production with the ultimate aim of industrial applications should place emphasis not only on enhancing the accumulation of desired carotenoids, but also on optimizing the light harvesting system of microalgae. It should be possible to significantly improve the overall productivity in this way.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Icelandic Technology Development Fund and the Geothermal Research Group (GEORG) Fund.

References

- 1.Lee SH, Kang HJ, Lee HJ, Kang MH, Park YK. Six-week supplementation with Chlorella has favorable impact on antioxidant status in Korean male smokers. Nutrition. 2010;26:175–83. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2009.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pulz O, Gross W. Valuable products from biotechnology of microalgae. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2004;65:635–48. doi: 10.1007/s00253-004-1647-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wijffels RH, Barbosa MJ. An outlook on microalgal biofuels. Science. 2010;329:796–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1189003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dismukes GC, Carrieri D, Bennette N, Ananyev GM, Posewitz MC. Aquatic phototrophs: efficient alternatives to land-based crops for biofuels. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2008;19:235–40. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Armbrust EV. The life of diatoms in the world’s oceans. Nature. 2009;459:185–92. doi: 10.1038/nature08057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Radakovits R, Jinkerson RE, Darzins A, Posewitz MC. Genetic engineering of algae for enhanced biofuel production. Eukaryot Cell. 2010;9:486–501. doi: 10.1128/EC.00364-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cordero BF, Obraztsova I, Couso I, Leon R, Vargas MA, Rodriguez H. Enhancement of lutein production in Chlorella sorokiniana (Chorophyta) by improvement of culture conditions and random mutagenesis. Mar Drugs. 2011;9:1607–24. doi: 10.3390/md9091607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fu W, Paglia G, Magnúsdóttir M, Steinarsdóttir EA, Gudmundsson S, Palsson BO, Andrésson OS, Brynjólfsson S. Effects of abiotic stressors on lutein production in the green microalga Dunaliella salina. Microb Cell Fact. 2014;13:3. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-13-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bohne F, Linden H. Regulation of carotenoid biosynthesis genes in response to light in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1579:26–34. doi: 10.1016/S0167-4781(02)00500-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cardol P, Forti G, Finazzi G. Regulation of electron transport in microalgae. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1807:912–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takaichi S. Carotenoids in algae: distributions, biosyntheses and functions. Mar Drugs. 2011;9:1101–18. doi: 10.3390/md9061101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hildebrand M, Davis AK, Smith SR, Traller JC, Abbriano R. The place of diatoms in the biofuels industry. Biofuels. 2012;3:221–40. doi: 10.4155/bfs.11.157. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katsuda T, Lababpour A, Shimahara K, Katoh S. Astaxanthin production by Haematococcus pluvialis under illumination with LEDs. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2004;35:81–6. doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2004.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Babu MM, Aravind L. Adaptive evolution by optimizing expression levels in different environments. Trends Microbiol. 2006;14:11–4. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ibarra RU, Edwards JS, Palsson BO. Escherichia coli K-12 undergoes adaptive evolution to achieve in silico predicted optimal growth. Nature. 2002;420:186–9. doi: 10.1038/nature01149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Teusink B, Wiersma A, Jacobs L, Notebaart RA, Smid EJ. Understanding the adaptive growth strategy of Lactobacillus plantarum by in silico optimisation. PLoS Comput Biol. 2009;5:e1000410. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Palsson BØ. Adaptive laboratory evolution. Microbe. 2011;6:69–74. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ben-Amotz A. Adaptation of the unicellular alga Dunaliella parva to a saline environment. J Phycol. 1975;11:50–4. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fu W, Gudmundsson O, Feist AM, Herjolfsson G, Brynjolfsson S, Palsson BØ. Maximizing biomass productivity and cell density of Chlorella vulgaris by using light-emitting diode-based photobioreactor. J Biotechnol. 2012;161:242–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fu W, Guðmundsson O, Paglia G, Herjólfsson G, Andrésson OS, Palsson BØ, Brynjólfsson S. Enhancement of carotenoid biosynthesis in the green microalga Dunaliella salina with light-emitting diodes and adaptive laboratory evolution. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;97:2395–403. doi: 10.1007/s00253-012-4502-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu S, Zhao Q, Miao X, Shi J. Enhancement of lipid production in low-starch mutants Chlamydomonas reinhardtii by adaptive laboratory evolution. Bioresour Technol. 2013;147:499–507. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2013.08.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feng S, Xue L, Liu H, Lu P. Improvement of efficiency of genetic transformation for Dunaliella salina by glass beads method. Mol Biol Rep. 2009;36:1433–9. doi: 10.1007/s11033-008-9333-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun G, Zhang X, Sui Z, Mao Y. Inhibition of pds gene expression via the RNA interference approach in Dunaliella salina (Chlorophyta) Mar Biotechnol (NY) 2008;10:219–26. doi: 10.1007/s10126-007-9056-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hempel F, Maier UG. An engineered diatom acting like a plasma cell secreting human IgG antibodies with high efficiency. Microb Cell Fact. 2012;11:126. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-11-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miyahara M, Aoi M, Inoue-Kashino N, Kashino Y, Ifuku K. Highly efficient transformation of the diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum by multi-pulse electroporation. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2013;77:874–6. doi: 10.1271/bbb.120936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rubio FC, Miron AS, Garcia MCC, Camacho FG, Molina-Grima E. Mixing in bubble columns: a new approach for characterizing dispersion coefficients. Chem Eng Sci. 2004;69:4369–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ces.2004.06.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Verwaal R, Wang J, Meijnen JP, Visser H, Sandmann G, van den Berg JA, van Ooyen AJ. High-level production of beta-carotene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by successive transformation with carotenogenic genes from Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:4342–50. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02759-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu J, Sun Z, Gerken H, Huang J, Jiang Y, Chen F. Genetic engineering of the green alga Chlorella zofingiensis: a modified norflurazon-resistant phytoene desaturase gene as a dominant selectable marker. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s00253-014-5593-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ben-Amotz A, Katz A, Avron M. Accumulation of β-carotene in halotolerant algae: Purification and characterization of β-carotene-rich globules from Dunaliella bardawil (Chlorophyceae) J Phycol. 1982;18:529–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8817.1982.tb03219.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aflalo C, Meshulam Y, Zarka A, Boussiba S. On the relative efficiency of two- vs. one-stage production of astaxanthin by the green alga Haematococcus pluvialis. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2007;98:300–5. doi: 10.1002/bit.21391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]